Abstract

Hairless mice carrying homozygous mutations in hairless gene manifest rudimentary hair follicles (HFs), epidermal cysts, hairless phenotype, and enhanced susceptibility to squamous cell carcinomas. However, their susceptibility to basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), a neoplasm considered originated from HF-localized stem cells, is unknown. To demonstrate the role of HFs in BCC development, we bred Ptch+/−/C57BL6 with SKH-1 hairless mice, followed by brother-sister cross to get F2 homozygous mutant (hairless) or wild-type (haired) mice. UVB-induced inflammation was less pronounced in shaved haired than in hairless mice. In hairless mice, inflammatory infiltrate was found around the rudimentary HFs and epidermal cysts. Expression of epidermal IL1f6, S100a8, vitamin D receptor, repetin, and major histocompatibility complex II, biomarkers depicting susceptibility to cutaneous inflammation, was also higher. In these animals, HF disruption altered susceptibility to UVB-induced BCCs. Tumor onset in hairless mice was 10 weeks earlier than in haired littermates. The incidence of BCCs was significantly higher in hairless than in haired animals; however, the magnitude of sonic hedgehog signaling did not differ significantly. Overall, 100% of hairless mice developed >12 tumors per mouse after 32 weeks of UVB therapy, whereas haired mice developed fewer than three tumors per mouse after 44 weeks of long-term UVB irradiation. Tumors in hairless mice were more aggressive than in haired littermates and manifested decreased E-cadherin and enhanced mesenchymal proteins. These data provide novel evidence that disruption of HFs in Ptch+/− mice enhances cutaneous susceptibility to inflammation and BCCs.

Homozygous mutations in hairless gene (hr) cause a permanent hair loss, referred to as alopecia in both humans and mice.1 The hairless animals are used historically as a convenient murine model to study skin carcinogenesis.2 In early studies, it was found that hairless animals are more susceptible to both chemically and UVB-induced skin squamous cell carcinogenesis compared with their haired littermates.3,4 However, the mechanism for this enhanced susceptibility to the development of squamous lesions remains undefined. It is also not known whether loss of hairless gene causes enhanced susceptibility for other epithelial cancers, such as basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

BCC is the most common human malignancy affecting about a million Americans each year. Hedgehog signaling pathway activation, particularly by mutations in PATCHED (PTCH) and smoothened, is the driving oncogenic signaling pathway underlying the pathogenesis of this neoplasm.5 Recently, using mouse genetics to identify cells responsible for the origin of BCC showed that these tumors arise from long-term resident progenitor cells of the interfollicular epidermis and the upper infundibulum.6 Later, Wang et al,7 by using cell fate tracking of X-ray–induced BCCs in Ptch1+/− mice, found that these BCCs essentially exclusively originate from the keratin 15–expressing stem cells of the follicular bulge, suggesting that hair follicle (HF) disruption may alter the pathogenesis of these tumors.

HFs are complex miniorgans in the skin that are formed during embryonic development.8 Post-natally, HFs undergo cyclic phases of active growth (anagen stage), regression (catagen stage), and inactivity (telogen stage).8,9 Hr is one of the key genes regulating these responses. Hr, a putative zinc finger protein, is highly expressed in the skin.10 It is considered as a candidate gene that regulates basic HF functions. Functionally, Hr is a transcriptional corepressor that is known to interact with various nuclear receptors, such as thyroid hormone receptor, retinoic acid orphan receptor α, and vitamin D receptor (VDR).11 These interactions are important for hair morphogenesis. In the carboxyl terminus of hr gene, a JmjC domain is located, which is one of the multiple conserved motifs identified in Jumonji proteins.12 It is known that JmjC domains in various proteins act as histone demethylases. Transcriptional repression often results from the association of corepressors with histone deacetylases (HDACs).13 It has been demonstrated that HR interacts with various HDACs, including HDACs 1, 3, and 5.14 Interestingly, corepressor activity of Hr is modified in the presence of an HDAC inhibitor.11,14 Although direct evidence demonstrating a role of HR in modifying epidermal carcinogenesis response is lacking, the HDACs are important modulators of cancer pathogenesis.15 The interaction of HR with VDR, an important regulator of cutaneous susceptibility to inflammation,16 also provides a basis for regulating susceptibility of the skin to both epithelial carcinogenesis and inflammatory tumor microenvironment.

Recently, we showed that loss of hr confers susceptibility to UVB-induced squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) by augmenting the NF-κB signaling pathway.17 These results raise the question of whether loss of hr-mediated NF-κB activation alters inflammatory response in these animals, because NF-κB is a well-established regulator of inflammatory response signaling in both experimental animal models and humans.18–20

Herein, we investigated whether mice with the loss of hr gene develop enhanced inflammatory response to UVB. We also tested whether the observed augmented inflammation in hairless littermates is associated with the enhanced pathogenesis to both SCCs and BCCs. These cancers are grouped as nonmelanoma cancers and are the most common type of cancers in the United States, with a combined incidence of more than 2 million new cases annually (Skin Cancer Foundation; http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/skin-cancer-facts, last accessed October 12, 2013).21

By using genetically engineered animals in this study, we showed that hairless mice developed significantly more BCCs and SCCs compared with their haired littermates. In addition, an inflammatory response in hairless mice was significantly higher than in their haired (shaved) littermates. Significantly more SCCs developed in hairless mice; these are poorly differentiated carcinomas showing enhanced expression of mesenchymal markers and reduced expression of epithelial markers than those that develop in haired (shaved) animals. These data provide the first evidence that hairless enhances susceptibility to both cutaneous inflammation and BCCs, in addition to SCCs. We also show that the enhanced inflammatory response also regulates aggressive tumor phenotype via regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT).

Materials and Methods

Animal Model

Ptch+/−/C57BL/6 haired male mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were crossed with SKH-1 hairless female mice (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). The litter was genotyped for Ptch+/− heterozygosity using an Extract-N-Amp Tissue PCR Kit (catalog number XNAT2-1KT) from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). The genotyping primers of PTCH were as follows: wild type, 5′-CTGCGGCAAGTTTTTGGTTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGGGCTTCTCGTTGGCTACAAG-3′ (reverse); and mutant type, 5′-GCCCTGAATGAACTGCAGGACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CACGGGTAGCCAACGCTATGTC-3′ (reverse). The F1 Ptch+/−/C57BL/6/SKH-1/hr+/− male mice were crossed with the F1 Ptch+/−/C57BL/6/SKH-1/hr+/− female mice, and only Ptch+/− mice (both haired and hairless), aged 6 to 8 weeks, were selected for this study.

Tumor Study

We used a UV irradiation unit (Daavlin Co, Bryan, OH) equipped with an electronic controller to regulate dosage, as described earlier.22 Twenty-six hairless mice (15 females and 11 males) were irradiated with 180 mJ/cm2 UVB, twice per week for 32 weeks, and 23 haired mice (13 females and 10 males) were exposed to 240 mJ/cm2 UVB irradiation, three times per week for 44 weeks. We titrated the doses of UVB in SKH-1, C57BL/6, and mixed C57BL/6/129 mice for cutaneous carcinogenic and inflammatory responses (unpublished data). The UVB doses tested were 180, 240, and 360 mJ/cm2. Chronic irradiation of C57BL/6 and mixed C57BL/6/129 mice with 180 mJ/cm2, twice weekly for approximately 50 weeks, did not produce significant inflammatory and tumor induction responses, whereas 360 mJ/cm2 produced multiple large spindle-cell carcinomas requiring early euthanasia. Therefore, the most suitable dose in this setting was 240 mJ/cm2.

The dorsal hair of haired mice was removed weekly by electric clipper after an initial depilatory cream (NAIR Lotion, Princeton, NJ) application. Tumors on the dorsal area of both groups were measured by digital calipers, and tumor volumes were calculated using the following formula:

| (1) |

plotted as a function of weeks taking the test.

SSZ Treatment

Twenty Ptch+/−/hr−/− mice, aged 6 to 8 weeks, were divided into two groups (10 mice per group) and irradiated with 180 mJ/cm2 UVB twice a week for 26 weeks. Group 1 served as control, whereas group 2 animals were orally administered with 300 ppm of sulfasalazine (SSZ) in drinking water, which was solubilized by adding a few drops of sodium hydroxide (1N). Mice were sacrificed at week 26. Their dorsal skin was removed, and tumors were harvested and collected for subsequent studies.

Antibodies and Reagents

Primary antibodies include Bcl2, caspase 3, IL1f6, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), S100a8 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), CD11b, CD3, CD4, CD49b, GR-1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), fibronectin, major histocompatibility complex (MHC) II, repetin, slug, snail, twist, vimentin, VDR (Abcam, Cambridge, MA), cyclin D1 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), and cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 (Cayman, Ann Arbor, MI). Horseradish peroxidase secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) and Alexa Fluor 488 or 596 conjugated secondary antibodies (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) were used. The SSZ was purchased from Sigma.

Immunoblotting

Tissues were homogenized and lysed in 100 μL of radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer. Total protein (50 μg) was separated on a 6% to 12% SDS-PAGE gel and blotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. A Western blot assay was performed as described previously.22

IHC and Immunofluorescence Analysis in Tissue

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) and immunofluorescence of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue specimens were performed as described previously.22 The densitometeric analysis was done by ImageJ software version 1.43u, which was downloaded from the NIH (Bethesda, MD; http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/index.html, last accessed October 17, 2013).

TUNEL Data

TUNEL staining was performed using a kit (catalog number 1684795) from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN), exactly according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

RT-PCR Data

Total RNA was isolated from skin according to manufacturer’s protocol using a TRIzol reagent extraction kit (catalog number 15596-026; Invitrogen, Grand Island, NY). A total of 1 μg of RNA was used for reverse transcription using an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Primers used were as follows: GLI1, 5′-GTCGGAAGTCCTATTCACGC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGTCTGCTCTCTTCCCTGC-3′ (reverse); GLI2, 5′-GAGCAGAAGCCCTTCAAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GACAGTCTTCACATGCTT-3′ (reverse); GLI3, 5′-CAAGCCTGATGAAGACCTCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-GCTTTGAACGGTTTCTGCTC-3′ (reverse); PTCH1, 5′-AACAAAAATTCAACCAAACCTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGTCTTCATTCCAGTTGATGTG-3′ (reverse); PTCH2, 5′-TGCCTCTCTGGAGGGCTTCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-CAGTTCCTCCTGCCAGTGCA-3′ (reverse); and Cyclin D1, 5′-AGGAGCAGAAGTGCGAAGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CTGGCATTTTGGAGAGGAAG-3′ (reverse). The gel image was semiquantified by ImageJ software version 1.43u.

PCR Array

PCR array was done using an SA Biosciences PCR Array System (Valencia, CA). First-strand cDNA synthesis was done using an RT2 First Strand kit. Real-time PCR was done with mouse inflammatory cytokines and receptor PCR arrays (PAMM-011C) on the iQ5 (Bio-Rad) using RT2 qPCR Master Mix. The program was as follows: 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. For each group, three skin samples were used for PCR array analysis. Relative fold changes of gene expression were calculated according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and the manufacturer’s software was available online.

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay Data

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was performed using a prostaglandin E (PGE) 2 express electroimmunoassay kit (item number 500141; Cayman).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). The significance between the two test groups was determined using a two-tailed Student’s t-test, and P ≤ 0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

Hairless animals are known to be more susceptible to the induction of SCCs than their haired (shaved) littermates.17 To elucidate the mechanism by which the hairless phenotype affects UVB carcinogenesis, we developed haired and hairless littermates by crossing SKH-1 hairless (red-eyed) and Ptch1+/−/C57BL6 (black-eyed) mice, as shown in Supplemental Figure S1. These littermates consist of haired and hairless mice segregated for black and red eyes. Our experimental animals in both haired and hairless categories represented almost equal numbers in phenotypes of black/red eye color and white/black/agouti brown hair color.

To induce tumors in these animals, hairless mice were exposed to a much lower dose of UVB (180 mJ/cm2, twice a week) compared with haired animals that received a higher dose of UVB (240 mJ/cm2, three times per week). The UVB dose selection was based on our earlier experiments, in which we used haired and hairless animals for inducing cutaneous tumors.23,24 As shown in Table 1, the cumulative dose of UVB needed to induce tumorigenesis in haired animals was approximately three times higher than that required for hairless animals (23.04 J versus 7.92 J). The latency period of tumor induction was 32 weeks in haired mice and 22 weeks in hairless mice (Figure 1A). By using these UVB exposure protocols, only approximately 40% of animals in the haired group developed tumors by week 44 compared with 100% of animals in the hairless group that developed tumors by week 32. The tumor multiplicity of the dorsal area in the two groups was also significantly different. In hairless mice, the number of tumors per mouse was 12.5 ± 1.5 compared with 2.5 ± 0.8 in haired mice (Figure 1B). The tumor burden in haired (shaved) mice was much lower compared with that in hairless mice. Of 23 haired mice, only 8 had tumors (range, 1 to 9 tumors per mouse), whereas of 26 hairless mice, 21 had tumors (range, 3 to 18 tumors per mouse). The pattern of tumor growth in terms of both tumor numbers and tumor volume was significantly different at almost all time points recorded. However, at 32 weeks, the significance level reached high (P < 0.001). The tumor spectrum in the two groups was also different. Haired mice developed benign papillomas, highly differentiated SCCs, BCCs, and a few spindle-cell carcinomas, whereas hairless mice developed benign papilloma, SCCs (both highly invasive and differentiated), BCCs, trichoblastomas, and rhabdomyosarcomas (Supplemental Figure S2). The distribution of overall tumor multiplicity in males versus females was 4.5:1 in haired animals, whereas it was not significantly different in hairless animals (1.43:1). These data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of UVB-Induced Skin Carcinogenesis in Ptch+/− Haired and Hairless Littermates

| Parameters | Haired | Hairless |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor latency (weeks) | 32 | 22 |

| Cumulative UVB dose required to develop first tumor (J) | 23.04 | 7.92 |

| Tumor incidence (%) | 40 (at week 44) | 100 (at week 32) |

| Average no. of tumors per mouse | 2.5 | 12.5 |

| Tumor spectrum | Papilloma, SCC, BCC, and spindle-cell tumors | Papilloma, SCC, BCC, trichoblastoma, and rhabdomyosarcomas |

| Male/female distribution of tumors | 4.5:1 | 1.43:1 |

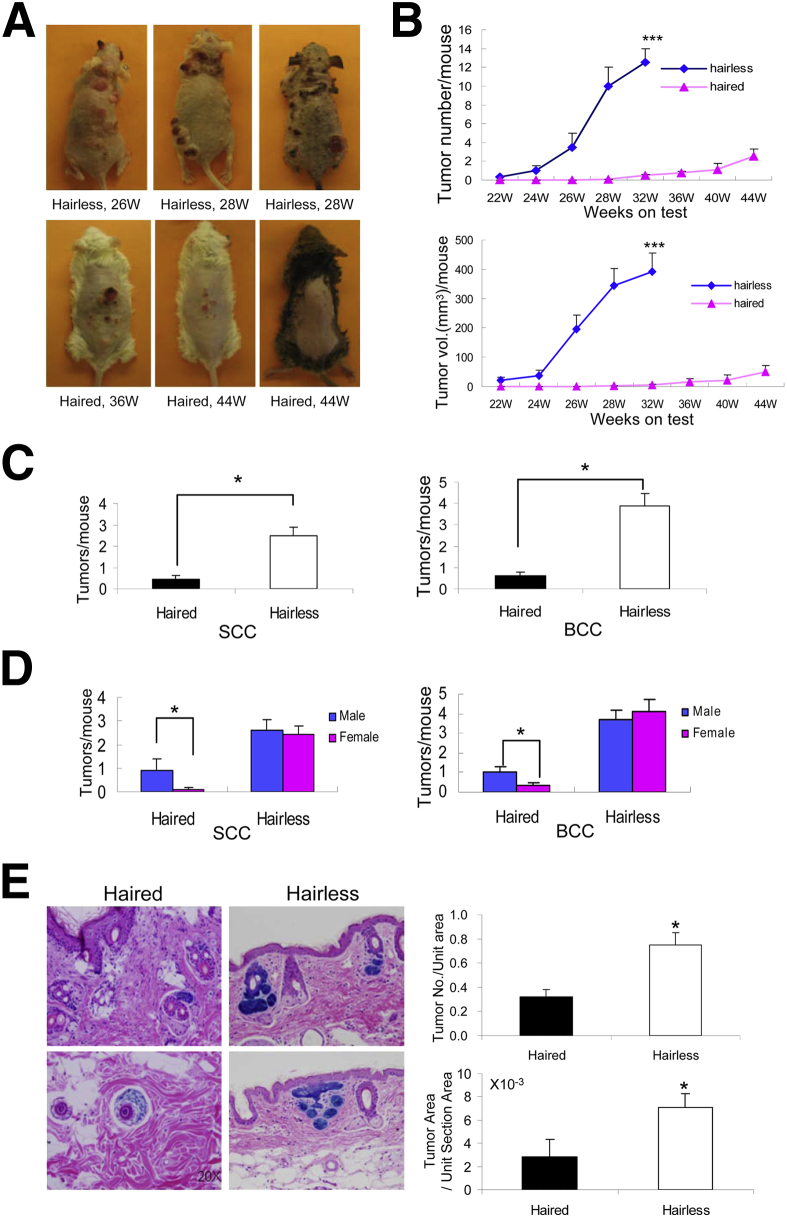

Figure 1.

UVB-induced SCCs and BCCs in Ptch+/− haired and hairless mice. A: Representative images of tumor-bearing hairless and haired mice. B: Tumor growth graph showing the progressive increase in tumor number and tumor size in hairless and haired animals when plotted against week on test. C: Multiplicity of UVB-induced SCCs and BCCs in hairless and haired littermates. D: Bar diagram showing tumor numbers by sex categorization. E: β-Gal staining and bar diagram showing both number and size of microscopic BCCs in hairless and haired animals. Significance between the two groups was calculated using a Student’s t-test. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001. W, weeks.

HF Disruption Enhances Growth of Both SCCs and BCCs after Chronic UVB Irradiation

To investigate whether HF disruption in Ptch+/− mice affects SCC and BCC growth, we analyzed both haired (shaved) and hairless chronically UVB-irradiated Ptch+/− mice. Hairless mice developed more SCCs and BCCs compared with their haired littermates (2.51 ± 0.41 versus 0.43 ± 0.20 and 3.90 ± 0.57 versus 0.58 ± 0.18 tumors per mouse) (Figure 1C). Haired mice show a male predilection in both SCCs and BCCs, whereas hairless mice do not have remarkable sex differences in the two tumor types (Figure 1D). Microscopic BCCs in hairless mice are significantly larger in both number and size than in haired (shaved) mice (Figure 1E).

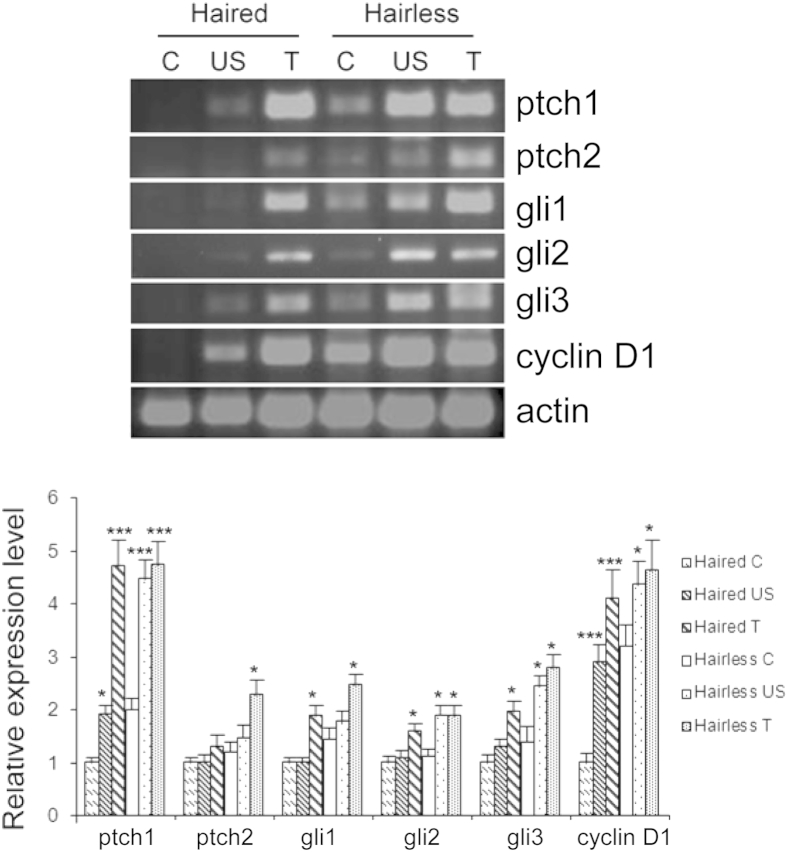

Hairless Phenotype Does Not Alter Transcript Levels of Shh Signaling–Related Genes

To understand whether the increase in BCCs in hairless mice is related to altered expression of sonic hedgehog (Shh) signaling–related genes that drive the pathogenesis of this neoplasm, we analyzed mRNA levels of these genes in tumors and in tumor-adjacent perilesional skin. Compared with their respective age-matched nonirradiated skin, the mRNA level of ptch1/2, gli1/2/3, and cyclin D1 increased to approximately the same level in BCCs induced in both haired and hairless mice, suggesting that these tumors are not significantly different in their molecular pathogenesis (Figure 2). However, we observed significant differences in the baseline expression of ptch1, gli1, and cyclin D1 transcripts (Supplemental Figure S3). When compared with baseline expression levels of age-matched control skins to tumor-adjacent perilesional skin of the haired and hairless mice, we found an increase in the expression of all of these genes in hairless mice, although only significant changes were observed in the levels of gli2 (Supplemental Figure S3).

Figure 2.

Transcript levels of Shh signaling–related genes in the skin and BCCs of hairless and haired mice. Semiquantitative/RT-PCR data were represented as means ± SEM of at least three samples (n = 3), with expression levels normalized to actin. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗∗P < 0.001, relative to corresponding control (C). T, tumor; US, UVB-irradiated skin.

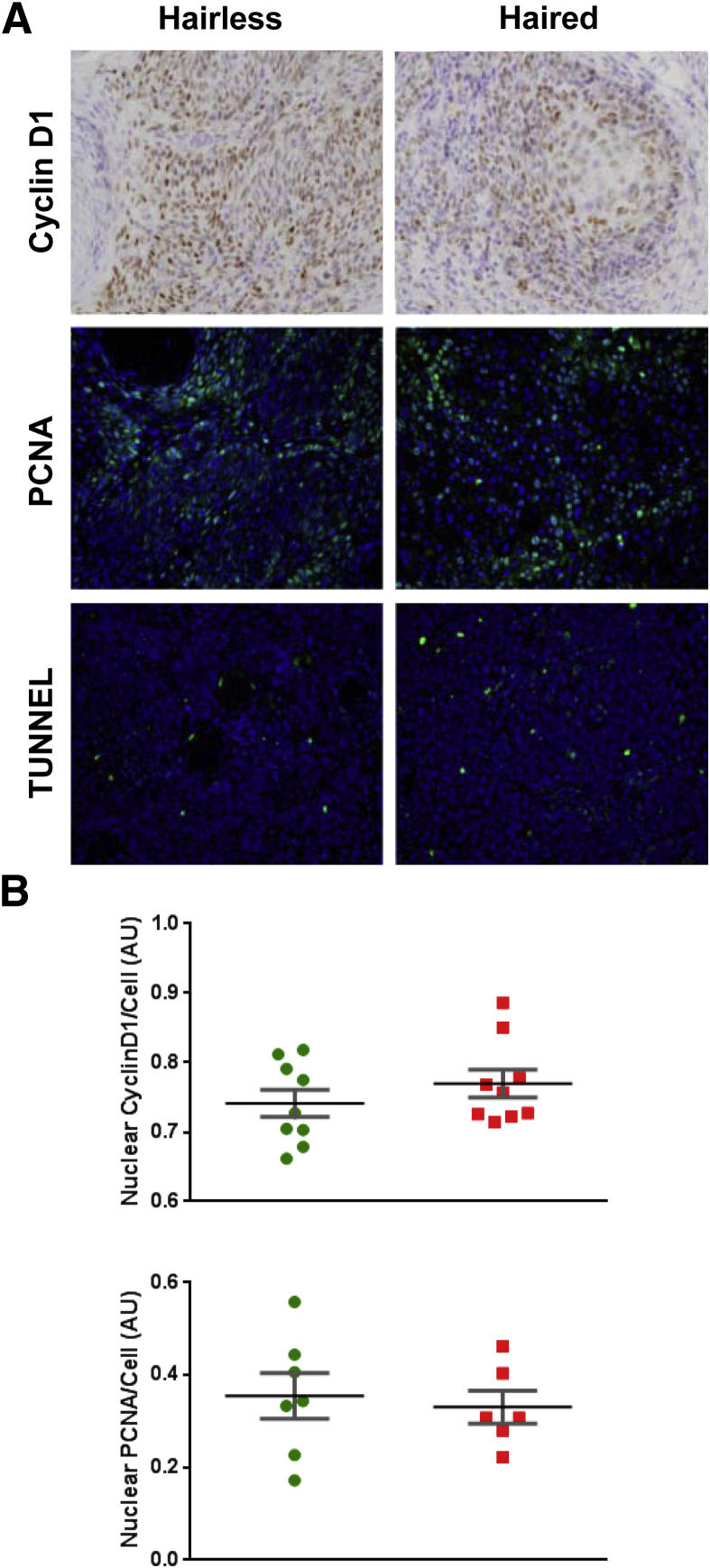

Proliferation- and Apoptosis-Related Signaling Proteins Are Not Significantly Altered in Tumors Induced in Haired or Hairless Mice

We analyzed cyclin D1 and PCNA expression as markers of proliferation and TUNEL staining to assess apoptosis in haired versus hairless skin and tumors (Figure 3). No significant differences were found in these biomarkers in tumors induced in haired versus hairless littermates. Similarly, we also did not observe significant differences in the expression of these biomarker proteins in either age-matched control skin or tumor-adjacent perilesional skin (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Expression of biomarkers related to proliferation and apoptosis in tumors induced in hairless and haired Ptch+/− littermates. A: IHC staining of cyclin D1, immunofluorescence staining of PCNA, and TUNEL staining. B: Nuclear cyclin D1 and PCNA staining, as quantified in BCCs excised from hairless and haired mice. Data are represented as means ± SEM of at least three samples. AU, arbitrary unit.

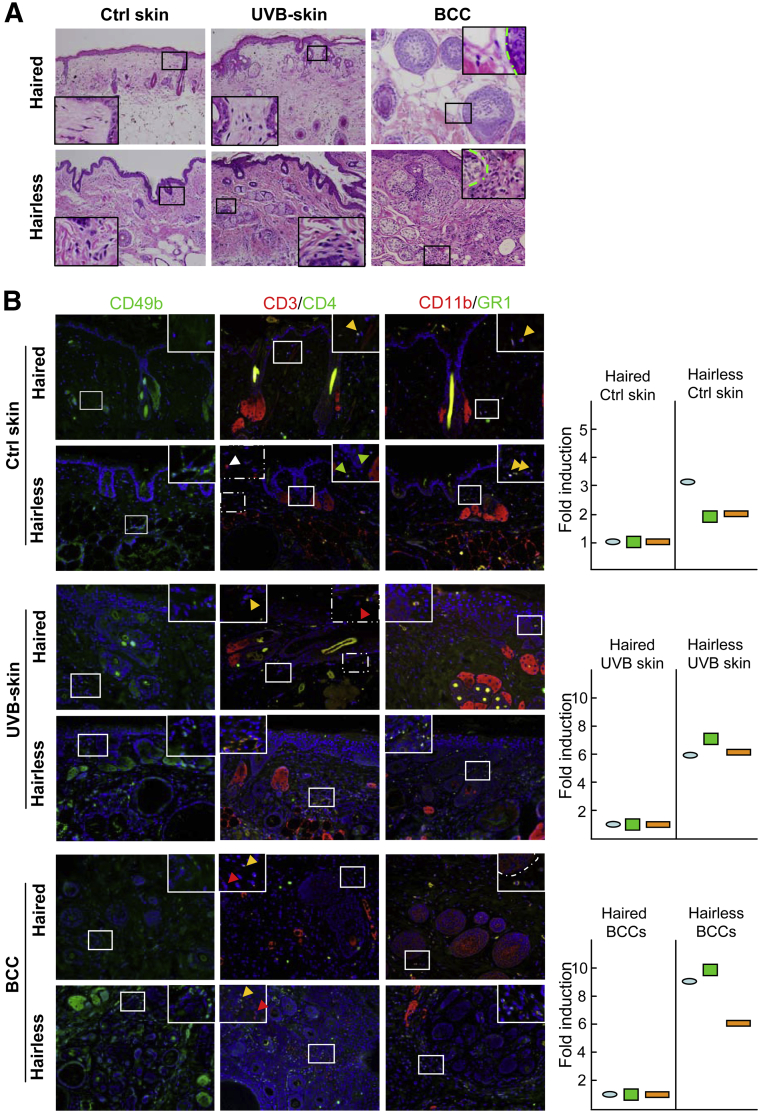

Intensive Inflammation Is Found Associated with Tumors Developed in Hairless Mice

To unravel the mechanism associated with the ability of hairless phenotype to develop enhanced epidermal tumors, we first analyzed inflammatory cell infiltration in the dermis of chronically UVB-irradiated animals. Analysis of H&E sections of nonirradiated age-matched control, UVB-irradiated tumor-adjacent perilesional skin, and tumors revealed the presence of more inflammatory cells associated with hairless phenotype (Figure 4A). Then, we typed these inflammatory cells using their specific surface markers, CD49b, CD3, CD4, CD11b, and GR1 (Figure 4B). We confirmed the presence of more T cells, neutrophils, and macrophage cells in the dermis of hairless animals. Baseline numbers of these cells were approximately twofold to threefold higher, whereas UVB-irradiated skin and BCCs showed a fivefold to sevenfold increase in their number compared with haired mice.

Figure 4.

Hairless mice manifest enhanced cutaneous inflammation compared with haired mice. A: H&E staining shows inflammatory cell infiltration in control skin, UVB-irradiated skin, and BCCs of hairless and haired mice. B: Immunofluorescence staining of inflammatory cell surface markers CD49b, CD3, CD4, CD11b, and GR-1 in the control (Ctrl) skin, UVB-exposed skin, and BCCs of hairless (green circles) and haired (red circles) mice. White, green, and red arrowheads indicate individual staining; yellow arrowheads, co-staining; blue ovals, CD49b cells; green rectangles, CD3/CD4 cells; orange rectangles, CD11b/Gr1 cells. Boxes show enlarged areas of images.

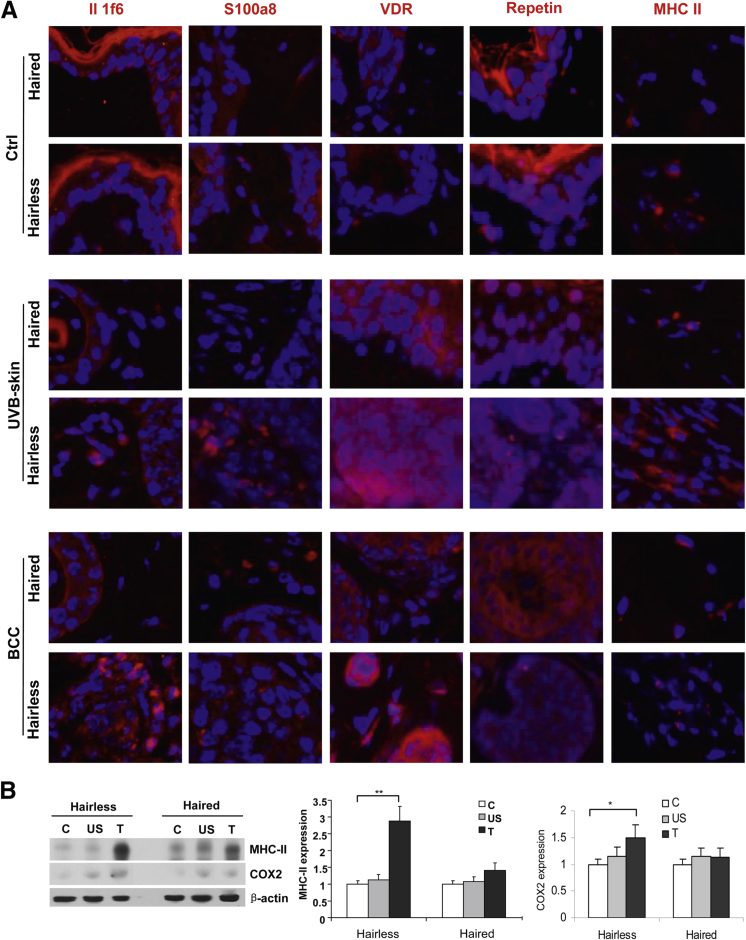

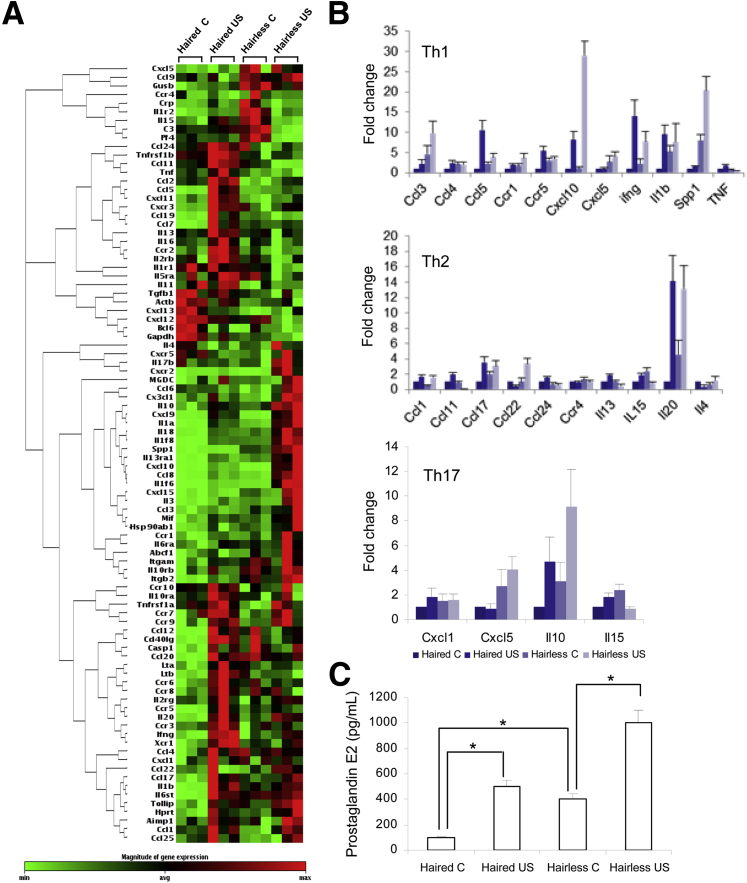

Then, we investigated the expression of various biomarker proteins depicting cutaneous susceptibility to inflammation in addition to expression of various cytokines regulating inflammatory responses. In this regard, the expression of IL1f6, S100a8, VDR, repetin, and MHCII, which are considered important in the regulation of cutaneous susceptibility to inflammatory response,25 was determined. Interestingly, enhanced expression of most of these inflammatory markers both at baseline and in tumor-adjacent perilesional skin and tumors in hairless compared with haired mice was found (Figure 5 and Supplemental Figure S4). Similarly, we also found a distinct pattern of cytokine signature expression profile in PCR array analysis associated with hairless and haired phenotypes (Figure 6A). Significantly high expression of chemokine ligand (CCL) 3, CCL4, CCL5, CCR5, CXCL5, interferon γ, IL-1b, secreted phosphoprotein 1, CCL17, IL-15, IL-20, IL-10, and IL-15, and decreased expression of CCL1 and CCL24, were recorded in hairless littermates (Figure 6B and Supplemental Table S1). In addition, PGE2 levels were also significantly higher in baseline control and in tumor-adjacent UVB-irradiated skin in hairless compared with haired mice (Figure 6C). Because PGE2 production is catalyzed by COX-2, we observed an analogous enhancement in the expression of this protein in hairless compared with haired mice (Figure 5B). Xia et al26 showed that the PGE2 levels affect DNA methylation during the pathogenesis of colon cancer. We, therefore, tested whether hairless phenotype is associated with the altered expression of DNA (cytosine-5)–methyltransferase 1. We did not find significant changes in the expression of this enzyme in hairless versus haired mouse skin (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Expression of proteins representing cutaneous susceptibility signature to inflammation and tumors in hairless and haired mice. A: Immunofluorescence staining of IL1f6, S100a8, VDR, repetin, and MHCII. B: Western blot and densitometry analyses of expression of MHCII and COX-2 in UVB-induced lesions, which developed in hairless and haired mice. Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent samples. ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. Original magnification, ×40 (A). Ctrl (A) or C (B), control; T, tumor; US, UVB-irradiated skin.

Figure 6.

PCR array analysis showing a comparison of the inflammatory and immune response gene profile in hairless and haired mice. A: Clustering analysis of the expression of 84 genes related to inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and their receptors in the skin of hairless and haired animals. A clustering pattern is indicated at the left side of the diagram. Genes with higher correlation coefficients across different samples are clustered together by rows. Thus, genes within the same cluster represent closer expression patterns than genes in different clusters. Each row represents a single gene labeled with the gene name, whereas each column represents an independent skin sample. The color in each cell reflects the gene expression level of the corresponding sample. The color scale at the bottom indicates the magnitude of gene expression. Expression levels greater than the mean are shaded in red, and those lower than the mean are shaded in green. B: Graphs showing relative gene expression levels of types 1 (Th1), 2 (Th2), and 17 (Th17) helper T-cell–associated inflammatory cytokines/chemokines and their receptors in the skin of haired and hairless mice. C: PGE2 levels in control (age-matched) and UVB-irradiated skin of haired and hairless mice. Data represent means ± SEM of at least three independent samples. ∗P < 0.05. C, control; US, UVB-irradiated skin.

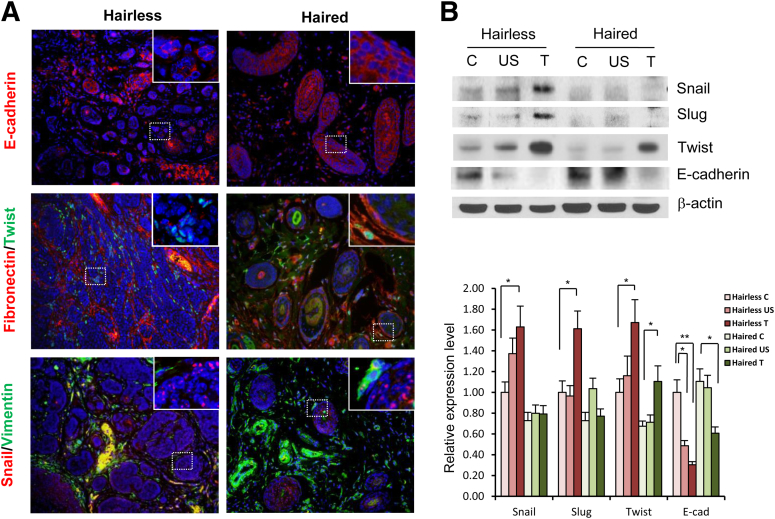

Hairless Phenotype Is Associated with an Enhanced Expression of Mesenchyme-Related Proteins

Because inflammation is known to regulate the progression of EMT,27–30 herein, we determined whether enhanced inflammatory response associated with hairless phenotype also alters expression of genes associated with EMT. The expression of E-cadherin, an epithelial marker in BCCs, induced in hairless mice was much less compared with its expression in BCCs developed in haired mice (Figure 7). Consistently, the expression of mesenchymal markers vimentin, fibronectin, snail, and twist in BCCs in hairless mice was much higher than that observed in BCCs in haired mice. This was evidenced in both immunofluorescent staining (Figure 7A) and Western blot analysis (Figure 7B). Although it is known that more SCCs with a poorly differentiated histological type are induced in hairless mice,31 the molecular basis for this difference remains unclear. To assess whether differential regulation of EMT in haired and hairless phenotypes is the underlying cause of enhanced SCC invasiveness in hairless mice, we typed these lesions for epithelial and mesenchymal marker proteins. We selected from the two groups similar histological tumor types for this study. SCCs in haired mice show higher expression of E-cadherin compared with that in hairless mice (Supplemental Figure S5). The expression of N-cadherin and snail was higher in hairless SCCs, whereas the expression of vimentin, fibronectin, and Twist was not significantly different in the two groups. Similarly, the highly invasive SCCs, which were invading dermis in hairless phenotype, had significantly higher expression of mesenchymal marker proteins, particularly at the tumor margin (data not shown).

Figure 7.

Expression of EMT regulatory proteins in BCCs induced in hairless and haired mice. A: Immunofluorescence staining showing expression of E-cadherin, fibronectin, twist, snail, and vimentin in UVB-induced BCCs in hairless and haired mice. B: Western blot and densitometry analyses showing expression of snail, slug, twist, and E-cadherin in control skin, UVB-irradiated skin, and UVB-induced BCCs in hairless and haired mice (n = 3). ∗P < 0.05, ∗∗P < 0.01. C, control; T, tumor; US, UVB-irradiated skin.

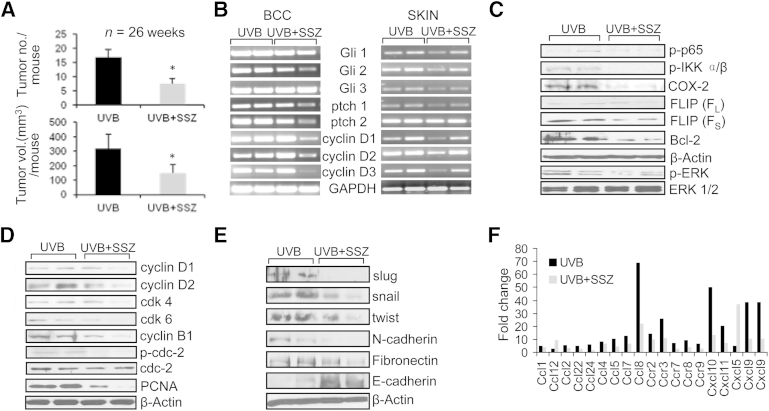

Inhibiting NF-κB by Chronic Treatment with SSZ Reduces UVB-Induced SCCs and BCCs, Tumor-Associated Inflammatory Response, and Expression of Mesenchyme-Related Proteins

To show that NF-κB is important in the regulation of inflammatory response and tumorigenesis, we investigated the effects of SSZ treatment on the onset of UVB-induced photocarcinogenesis in two different hairless murine models. The SSZ is an NF-κB inhibitor that is one of the agents used for the treatment of psoriatic rheumatoid arthritis.32 We found that SSZ significantly decreased skin tumors (both SCCs and BCCs) in these murine models (Figure 8 and Supplemental Figure S6). This decrease in tumorigenesis was associated with a decrease in NF-κB pathway and its proinflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and proliferation regulatory effects, as well as tumor-associated inflammation, as shown in Figure 8C. Thus, we found that expression of NF-κB–associated protein, IκBα, was elevated, whereas phosphorylated p65 and I κ kinase α/β were decreased. We also found a significant decrease in the NF-κB signal in electrophoretic mobility shift assay in skin and SCCs excised from SSZ-treated animals (data not shown). A decrease in NF-κB activity and signaling was associated with the diminished expression of its downstream targets, COX-2 and Bcl2 (Figure 8C). Consistently, we found an increase in apoptosis and a decrease in proliferation response (Figure 8D). Similarly, the cell cycle profile depicted by the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins, cyclin B1, D1/2/3, and CDK4/6, was also toned down significantly in these tumors. In BCCs, similar effects are noted. We also found that UVB-induced, inflammation-related genes were attenuated in the tumor-adjacent perilesional skin in the SSZ-treated Ptch+/−/hr−/− mice group (Figure 8F). A signifficant decrease in expression of phosphorylated extracellular signal–regulated kinase (ERK) in these tumors and a significant reduction in the expression of proteins depicting mesenchymal phenotype, such as snail, slug, and twist, with a concomitant increase in epithelial polarity depicting protein E-cadherin, were noted in the SSZ-treated group (Figure 8E).

Figure 8.

NF-κB inhibition reduces UVB-induced cutaneous inflammation and tumorigenesis in Ptch+/− hairless mice. A: Effects of chronic treatment of mice with 300 ppm of SSZ in drinking water on UVB-induced carcinogenesis. ∗P < 0.05. B: Semiquantitative RT-PCR analysis of Shh signaling genes in UVB-induced BCCs and tumor-adjacent perilesional skin. C: Western blot analysis showing expression of NF-κB–related signaling proteins in skin/tumors of SSZ-treated and UVB-alone–treated mice. D: Effects of SSZ on the expression of cell cycle regulatory proteins, proliferation marker, PCNA, and apoptosis-related protein, BclII. E: Effects of SSZ on the expression of EMT regulatory proteins. F: PCR array analysis of inflammatory cytokines in the skin of SSZ-treated and UVB-alone–irradiated animals. FLIP, FLICE-inhibitory protein; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; IKK, IκB kinase.

Discussion

The HF disruption leads to permanent hair loss, referred to as alopecia.1 Epidemiological data are not available to address conclusively whether alopecia enhances skin cancer risk. However, the male predominance of SCCs of the scalp has been well documented. In elderly men with significant androgenic alopecia and actinic damage, aggressive SCCs of the scalp are often reported.33,34 Multiple studies in murine skin demonstrated that hairless mice are highly susceptible to chemical- and UVB-induced skin squamous cell carcinogenesis.3,35 However, the underlying mechanism for this enhanced susceptibility to squamous cell tumor development remains undefined. Recently, we have shown that hr mutations in SKH-1 mice confer susceptibility to UVB-induced tumorigenesis in an NF-κB–dependent manner.17 Herein, we provide evidence that disrupted HFs augment squamous cell carcinogenesis and promote basal cell tumors. We show that by disrupting HFs, the tumor microenvironment is altered. We demonstrated that disruption of HFs alters the homing of dermal resident hemopoietic cells, including T cells, neutrophils, and macrophages. The baseline number of inflammation-related hemopoietic cells in the dermis of age-matched control skin was twofold to threefold higher in hairless compared with haired littermates. The basal-level changes in inflammatory response are also associated with the changes in the basal cytokines/chemokines and prostaglandin levels. In certain types of alopecia in humans, such as cicatricial alopecia, inflammation is considered an important component of the disease pathogenesis.36,37 It is likely that alterations in cutaneous inflammatory cells hosting response as a result of HF disruption may be responsible for the observed enhancement in the susceptibility to epithelial carcinogenesis affecting the pathogenesis of both SCCs and BCCs. At this stage, the factors that control the homing of hemopoietic or other nonkeratinocyte cell types of immune and inflammation regulatory cells are not defined.38 However, understanding of these factors may reveal a novel tumor susceptibility mechanism in addition to unraveling susceptibility to other cutaneous inflammatory disorders.

Our studies also show that UVB exposure to haired and hairless mice constitutes a distinct cutaneous inflammatory milieu that provides a resistant or conducive microenvironment for tumor development. The susceptible or resistant tumor microenvironment in the skin may be determined by the alterations in the expression of some of the known quantitative trait loci related to HF and inflammation.39 In this regard, we observed significant changes in the UVB-induced epidermal and tumor expression of Ilf6, S100a8, VDR, repetin, and MHCII genes. Among these, hairless is known to regulate VDR.40,41 Interestingly, VDR is known to be associated with inflammation, microbial defense, stem cell growth, and tumor susceptibility.42 IL1f6 and IL1f5 are ligands for IL-1 receptor and are known to regulate inflammation in skin after exposure to mitogens.43 The observed alterations only in IL-1f6, but not in IL-1f5, in this study (data not shown) suggest an involvement of IL-1f6 in UVB-induced inflammatory response. S100a8, which forms a complex with S100a9 and provides a proinflammatory signal for cutaneous inflammation,44 was also up-regulated in the hairless phenotype. Similarly, the barrier function regulating genes such as repetin45 is deferentially regulated in haired skin and tumor. These data suggest that HF disruption alters susceptibility to skin carcinogenesis by altering basal and UVB-induced inflammatory expression of some of the known quantitative trait loci in the hairless phenotype. Further studies are needed to understand the mechanisms underlying pathogenesis of inflammatory response by HF disruption and role of hr in determining cutaneous susceptibility to inflammation.

The observed alterations in NF-κB in this study are consistent with our earlier studies showing that hr regulates NF-κB.17 NF-κB is an important regulator of both inflammation and tumorigenesis.46 In this study, modulating NF-κB–dependent inflammatory response pharmacologically by administering SSZ inhibited tumorigenesis in hairless mice, confirming the role of inflammation in augmenting tumorigenesis after HF disruption.

Cutaneous inflammation is characterized by high expression of COX-2, IL1b, and cytokines, chemokines, and their receptors. Proinflammatory responses are associated with an invasive and EMT-promoting tumor microenvironment.47 For example, overexpression of IL1b led to development of high-grade invasive carcinoma.48 IL1b-deficient mice showed reduced chemically induced cutaneous tumorigenesis.49 IL1b down-regulates E-cadherin and induces matrix metalloproteinases associated with increased tumor aggressiveness and invasion.50 Similarly, COX-2 overexpression–mediated increased production of PGE2 has been shown to be associated with snail overexpression and increased vascularity.51 Therefore, the low expression of E-cadherin and high expression of Snail and other mesenchymal markers associated with hairless phenotype in this study may be due to enhanced levels of IL1b and COX-2/PGE2 observed in hairless mice.

In summary, these data provide first evidence that HF disruption augments pathogenesis of BCCs without significantly altering the pattern of Shh signaling induction. In addition, the hairless phenotype is also associated with the enhanced hosting of resident inflammatory cells in the dermis of the skin. An additional novel finding described herein is the demonstration that HF disruption leads to enhanced susceptibility to skin inflammatory response. The tumor microenvironments in hairless and haired phenotypes are distinct, and the hairless phenotype is more conducive to invasive and aggressive tumor growth.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants R01-ES015323 and R01-CA130998-01A2 (M.A.).

Disclosures: None declared.

A guest editor acted as the editor in chief for this manuscript. No person at the University of Alabama at Birmingham was involved in the peer review process or final disposition for this article.

Supplemental Data

Breeding strategy for Ptch+/− haired and hairless mice. Mice in both the haired and hairless categories represented each of the following phenotypes and were incorporated in UVB-induced tumorigenesis experiments: eye color, black/red; hair color, white/black/agouti brown.

Tumor histological characteristics and tumor spectrum in Ptch+/− haired and hairless mice. RMS, rhabdomyosarcoma.

Expression of ptch1, ptch2, gli1, gli2, gli3, and cyclin D1 in nonirradiated control (Ctrl) and UVB-irradiated skin of Ptch+/− haired and hairless mice. ∗P < 0.05.

Hairless mice manifest enhanced cutaneous inflammation compared with haired mice. A: Immunofluorescence staining of inflammation-related markers IL1f6, S100a8, VDR, repetin, and MHCII. B: The expression levels of the markers in A. Original magnifications: ×10 (A); ×40 (inset, A). Ctrl, control.

Histological and immunofluorescence staining of EMT-related biomarkers in UVB-induced SCCs developed in hairless and haired mice. Boxes show enlarged areas of images.

SSZ treatment abrogates tumor growth and tumor-associated inflammation in SKH-1 mice. A: Effects of SSZ treatment on tumor number and volume in UVB-irradiated SKH-1 mice. B: Expression of NF-κB inhibitory proteins. C: Expression of cell cycle regulating proteins. Cyclin D1 mRNA levels (D) and ERK and phosphorylated ERK signaling proteins in control, UVB-irradiated, and UVB + SSZ-treated groups (E). NIK, NF-κB inducing kinase.

References

- 1.Panteleyev A.A., Botchkareva N.V., Sundberg J.P., Christiano A.M., Paus R. The role of the hairless (hr) gene in the regulation of hair follicle catagen transformation. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:159–171. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65110-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benavides F., Oberyszyn T.M., VanBuskirk A.M., Reeve V.E., Kusewitt D.F. The hairless mouse in skin research. J Dermatol Sci. 2009;53:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forbes P.D., Blum H.F., Davies R.E. Photocarcinogenesis in hairless mice: dose-response and the influence of dose-delivery. Photochem Photobiol. 1981;34:361–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iversen U., Iversen O.H. The sensitivity of the skin of hairless mice to chemical carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1976;36:1238–1241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Athar M., Tang X., Lee J.L., Kopelovich L., Kim A.L. Hedgehog signalling in skin development and cancer. Exp Dermatol. 2006;15:667–677. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2006.00473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Youssef K.K., Van Keymeulen A., Lapouge G., Beck B., Michaux C., Achouri Y., Sotiropoulou P.A., Blanpain C. Identification of the cell lineage at the origin of basal cell carcinoma. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:299–305. doi: 10.1038/ncb2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang G.Y., Wang J., Mancianti M.L., Epstein E.H., Jr. Basal cell carcinomas arise from hair follicle stem cells in Ptch1(+/-) mice. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:114–124. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Törnqvist G., Sandberg A., Hägglund A.C., Carlsson L. Cyclic expression of lhx2 regulates hair formation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panteleyev A.A., Jahoda C.A., Christiano A.M. Hair follicle predetermination. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:3419–3431. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.19.3419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Djabali K., Christiano A.M. Hairless contains a novel nuclear matrix targeting signal and associates with histone deacetylase 3 in nuclear speckles. Differentiation. 2004;72:410–418. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2004.07208007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson C.C. Hairless is a nuclear receptor corepressor essential for skin function. Nucl Recept Signal. 2009;7:e010. doi: 10.1621/nrs.07010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clissold P.M., Ponting C.P. JmjC: cupin metalloenzyme-like domains in jumonji, hairless and phospholipase A2beta. Trends Biochem Sci. 2001;26:7–9. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)01700-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pazin M.J., Kadonaga J.T. What's up and down with histone deacetylation and transcription? Cell. 1997;89:325–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Potter G.B., Zarach J.M., Sisk J.M., Thompson C.C. The thyroid hormone-regulated corepressor hairless associates with histone deacetylases in neonatal rat brain. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16:2547–2560. doi: 10.1210/me.2002-0115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bruserud O., Stapnes C., Ersvaer E., Gjertsen B.T., Ryningen A. Histone deacetylase inhibitors in cancer treatment: a review of the clinical toxicity and the modulation of gene expression in cancer cell. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2007;8:388–400. doi: 10.2174/138920107783018417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schauber J., Gallo R.L. The vitamin D pathway: a new target for control of the skin’s immune response? Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2008.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim H., Casta A., Tang X., Luke C.T., Kim A.L., Bickers D.R., Athar M., Christiano A.M. Loss of hairless confers susceptibility to UVB-induced tumorigenesis via disruption of NF-kappaB signaling. PLoS One. 2012;7:e39691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rahman M.M., Mohamed M.R., Kim M., Smallwood S., McFadden G. Co-regulation of NF-kappaB and inflammasome-mediated inflammatory responses by myxoma virus pyrin domain-containing protein M013. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000635. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bauer J., Namineni S., Reisinger F., Zoller J., Yuan D., Heikenwalder M. Lymphotoxin, NF-kB, and cancer: the dark side of cytokines. Dig Dis. 2012;30:453–468. doi: 10.1159/000341690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moretti M., Bennett J., Tornatore L., Thotakura A.K., Franzoso G. Cancer: NF-kappaB regulates energy metabolism. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2012;44:2238–2243. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers H.W., Weinstock M.A., Harris A.R., Hinckley M.R., Feldman S.R., Fleischer A.B., Coldiron B.M. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States. Arch Dermatol. 2006;146:283–287. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang X., Zhu Y., Han L., Kim A.L., Kopelovich L., Bickers D.R., Athar M. CP-31398 restores mutant p53 tumor suppressor function and inhibits UVB-induced skin carcinogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3753–3764. doi: 10.1172/JCI32481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Athar M., Li C., Tang X., Chi S., Zhang X., Kim A.L., Tyring S.K., Kopelovich L., Hebert J., Epstein E.H., Jr., Bickers D.R., Xie J. Inhibition of smoothened signaling prevents ultraviolet B-induced basal cell carcinomas through regulation of Fas expression and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:7545–7552. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang X., Kim A.L., Kopelovich L., Bickers D.R., Athar M. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor nimesulide blocks ultraviolet B-induced photocarcinogenesis in SKH-1 hairless mice. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:522–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00303.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Quigley D.A., To M.D., Perez-Losada J., Pelorosso F.G., Mao J.H., Nagase H., Ginzinger D.G., Balmain A. Genetic architecture of mouse skin inflammation and tumour susceptibility. Nature. 2009;458:505–508. doi: 10.1038/nature07683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xia D., Wang D., Kim S.H., Katoh H., DuBois R.N. Prostaglandin E2 promotes intestinal tumor growth via DNA methylation. Nat Med. 2012;18:224–226. doi: 10.1038/nm.2608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong C.E., Yu J.S., Quigley D.A., To M.D., Jen K.Y., Huang P.Y., Del Rosario R., Balmain A. Inflammation and Hras signaling control epithelial-mesenchymal transition during skin tumor progression. Genes Dev. 2013;27:670–682. doi: 10.1101/gad.210427.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuxe J., Karlsson M.C. TGF-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition: a link between cancer and inflammation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22:455–461. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez-Novoa J.M., Nieto M.A. Inflammation and EMT: an alliance towards organ fibrosis and cancer progression. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:303–314. doi: 10.1002/emmm.200900043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Z., Li Y., Sarkar F.H. Signaling mechanism(s) of reactive oxygen species in epithelial-mesenchymal transition reminiscent of cancer stem cells in tumor progression. Curr Stem Cell Res Ther. 2010;5:74–80. doi: 10.2174/157488810790442813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fu J., Bassi D.E., Zhang J., Li T., Cai K.Q., Testa C.L., Nicolas E., Klein-Szanto A.J. Enhanced UV-induced skin carcinogenesis in transgenic mice overexpressing proprotein convertases. Neoplasia. 2013;15:169–179. doi: 10.1593/neo.121846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wahl C., Liptay S., Adler G., Schmid R.M. Sulfasalazine: a potent and specific inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1163–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lang P.G., Jr., Braun M.A., Kwatra R. Aggressive squamous carcinomas of the scalp. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:1163–1170. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2006.32258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Franceschi S., Levi F., Randimbison L., La Vecchia C. Site distribution of different types of skin cancer: new aetiological clues. Int J Cancer. 1996;67:24–28. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19960703)67:1<24::AID-IJC6>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Steinel H.H., Baker R.S. Sensitivity of HRA/Skh hairless mice to initiation/promotion of skin tumors by chemical treatment. Cancer Lett. 1988;41:63–68. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(88)90055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harries M.J., Paus R. The pathogenesis of primary cicatricial alopecias. Am J Pathol. 2010;177:2152–2162. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.100454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karnik P., Stenn K. Cicatricial Alopecia Symposium 2011: lipids, inflammation and stem cells. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1529–1531. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kang S.K., Shin I.S., Ko M.S., Jo J.Y., Ra J.C. Journey of mesenchymal stem cells for homing: strategies to enhance efficacy and safety of stem cell therapy. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:342968. doi: 10.1155/2012/342968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Quigley D.A., To M.D., Kim I.J., Lin K.K., Albertson D.G., Sjolund J., Perez-Losada J., Balmain A. Network analysis of skin tumor progression identifies a rewired genetic architecture affecting inflammation and tumor susceptibility. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R5. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-1-r5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mi Y., Zhang Y., Shen Y.F. Mechanism of JmjC-containing protein Hairless in the regulation of vitamin D receptor function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1675–1680. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Engelhard A., Bauer R.C., Casta A., Djabali K., Christiano A.M. Ligand-independent regulation of the hairless promoter by vitamin D receptor. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:515–521. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu S., Sun J. Vitamin D, vitamin D receptor, and macroautophagy in inflammation and infection. Discov Med. 2011;11:325–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johnston A., Xing X., Guzman A.M., Riblett M., Loyd C.M., Ward N.L., Wohn C., Prens E.P., Wang F., Maier L.E., Kang S., Voorhees J.J., Elder J.T., Gudjonsson J.E. IL-1F5, -F6, -F8, and -F9: a novel IL-1 family signaling system that is active in psoriasis and promotes keratinocyte antimicrobial peptide expression. J Immunol. 2011;186:2613–2622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lim S.Y., Raftery M.J., Geczy C.L. Oxidative modifications of DAMPs suppress inflammation: the case for S100A8 and S100A9. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;15:2235–2248. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Toulza E., Mattiuzzo N.R., Galliano M.F., Jonca N., Dossat C., Jacob D., de Daruvar A., Wincker P., Serre G., Guerrin M. Large-scale identification of human genes implicated in epidermal barrier function. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R107. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-6-r107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Greten F.R., Karin M. The IKK/NF-kappaB activation pathway: a target for prevention and treatment of cancer. Cancer Lett. 2004;206:193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2003.08.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee J.M., Yanagawa J., Peebles K.A., Sharma S., Mao J.T., Dubinett S.M. Inflammation in lung carcinogenesis: new targets for lung cancer chemoprevention and treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2008;66:208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maker A.V., Katabi N., Qin L.X., Klimstra D.S., Schattner M., Brennan M.F., Jarnagin W.R., Allen P.J. Cyst fluid interleukin-1beta (IL1beta) levels predict the risk of carcinoma in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:1502–1508. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oka M., Edamatsu H., Kunisada M., Hu L., Takenaka N., Dien S., Sakaguchi M., Kitazawa R., Norose K., Kataoka T., Nishigori C. Enhancement of ultraviolet B-induced skin tumor development in phospholipase Cepsilon-knockout mice is associated with decreased cell death. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:1897–1902. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsu M.Y., Meier F., Herlyn M. Melanoma development and progression: a conspiracy between tumor and host. Differentiation. 2002;70:522–536. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heinrich E.L., Walser T.C., Krysan K., Liclican E.L., Grant J.L., Rodriguez N.L., Dubinett S.M. The inflammatory tumor microenvironment, epithelial mesenchymal transition and lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Microenviron. 2012;5:5–18. doi: 10.1007/s12307-011-0089-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Breeding strategy for Ptch+/− haired and hairless mice. Mice in both the haired and hairless categories represented each of the following phenotypes and were incorporated in UVB-induced tumorigenesis experiments: eye color, black/red; hair color, white/black/agouti brown.

Tumor histological characteristics and tumor spectrum in Ptch+/− haired and hairless mice. RMS, rhabdomyosarcoma.

Expression of ptch1, ptch2, gli1, gli2, gli3, and cyclin D1 in nonirradiated control (Ctrl) and UVB-irradiated skin of Ptch+/− haired and hairless mice. ∗P < 0.05.

Hairless mice manifest enhanced cutaneous inflammation compared with haired mice. A: Immunofluorescence staining of inflammation-related markers IL1f6, S100a8, VDR, repetin, and MHCII. B: The expression levels of the markers in A. Original magnifications: ×10 (A); ×40 (inset, A). Ctrl, control.

Histological and immunofluorescence staining of EMT-related biomarkers in UVB-induced SCCs developed in hairless and haired mice. Boxes show enlarged areas of images.

SSZ treatment abrogates tumor growth and tumor-associated inflammation in SKH-1 mice. A: Effects of SSZ treatment on tumor number and volume in UVB-irradiated SKH-1 mice. B: Expression of NF-κB inhibitory proteins. C: Expression of cell cycle regulating proteins. Cyclin D1 mRNA levels (D) and ERK and phosphorylated ERK signaling proteins in control, UVB-irradiated, and UVB + SSZ-treated groups (E). NIK, NF-κB inducing kinase.