Abstract

The post-translational modification (PTM) of proteins and their allosteric regulation by metabolites represent conserved regulatory mechanisms in biology. At the confluence of these two processes, we report that the primary glycolytic intermediate 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate reacts with select lysine residues in proteins to form 3-phosphoglyceryl-lysine (pgK). This reaction, which does not require enzyme catalysis, but rather exploits the electrophilicity of 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate, was found by proteomic profiling to be enriched on diverse classes of proteins and prominently in or around the active sites of glycolytic enzymes. pgK modifications inhibit glycolytic enzyme activities, and, in cells exposed to high glucose, accumulate on these enzymes to create a potential feedback mechanism that contributes to the buildup and redirection of glycolytic intermediates to alternate biosynthetic pathways.

Regulation of protein structure and function by reversible small-molecule binding (1, 2) and covalent post-translational modification (PTM) (3) are core tenets in biochemistry. Many intermediates in primary metabolic pathways reversibly bind to proteins as a form of feedback or feedforward regulation (2). Covalent PTMs are, on the other hand, typically introduced onto proteins by enzyme-catalyzed processes, but can also result from enzyme-independent interactions between reactive metabolites and nucleophilic residues in proteins (4–7). The scope and broad functional significance of non-enzymatic modifications of proteins, however, remain poorly understood. In this context, we wondered whether intrinsically reactive intermediates in primary metabolic pathways might covalently modify proteins.

A survey of primary metabolites with the potential to modify proteins focused our attention on the central glycolytic intermediate 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate (1,3-BPG), a product of catalysis by glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) that has a highly electrophilic acylphosphate group (Fig. 1A). Acylphosphate reactivity is central to several enzyme-catalyzed metabolic processes (8, 9) and has proven useful in the design electrophilic nucleotide probes that react with conserved lysines within kinase active sites (10). We thus examined whether 1,3-BPG might modify lysine residues on proteins to form 3-phosphoglyceryl-lysine (pgK, Fig. 1A).

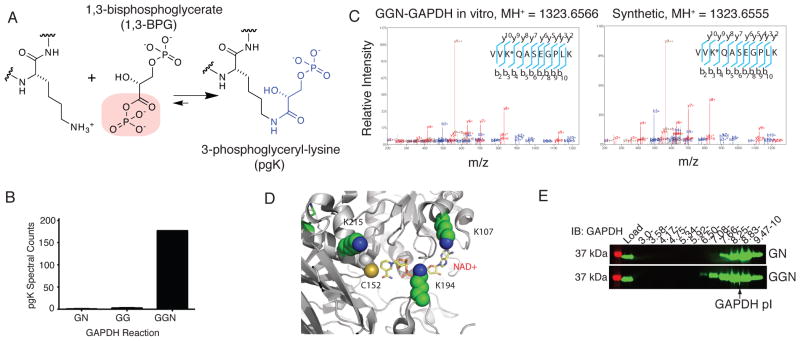

Fig. 1.

1,3-BPG forms a stable, covalent modification on lysines of GAPDH in vitro. (A) 3-phosphoglyceryl-lysine (pgK) formed by reaction of a lysine ε-amine with the acylphosphate functionality in 1,3-BPG. (B) Spectral counts of pgK-modified tryptic peptides detected by LC-MS/MS analyses of GN, GG, and GGN GAPDH enzymatic reactions (average of two independent experiments). (C) MS/MS spectra of the doubly charged synthetic (right) and in vitro GGN-GAPDH-derived (left) tryptic peptide VV(pg)KQASEGPLK. Observed b-, y-, and relevant parent ions, as well as products of dehydration (°) or ammonia loss (*) are labeled. “*” within peptide sequences denotes the pgK-modified lysine. (D) The most frequently detected pgK-modification sites (K107, K194 and K215) surround the active site of GAPDH (PDB Accession 1ZNQ). (E) α-GAPDH western blot of GG- and GGN-GAPDH reactions after IEF analysis. Data are from a representative experiment of three independent experiments.

Because of its propensity for rearrangement to the more stable isomer 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate (2,3-BPG), 1,3-BPG is not commercially available. Therefore, to initially determine whether 1,3-BPG reacted with proteins to form pgK modifications, we produced this metabolite in situ by incubating purified human GAPDH with substrate and cofactor (Fig. S1). GAPDH was then trypsinized and analyzed by LC-MS/MS on an Orbitrap Velos mass spectrometer for peptides with a differential modification mass of 167.98238 Da on lysines, the expected mass shift caused by pgK formation. Several pgK-modified GAPDH peptides were identified in reactions with substrate and cofactor (GGN conditions; Fig. 1B and Table S1). These pgK-modified peptides were much less abundant, but still detectable in control reactions lacking substrate (GN) or cofactor (GG), suggesting that commercial GAPDH, which is purified from erythrocytes, may be constitutively pgK-modified. Structural assignments for two distinct pgK-modified GAPDH peptides were verified by comparison to synthetic peptide standards (Fig. S2, see Materials and Methods), which showed equivalent LC retention times and MS/MS spectra (Fig. 1C; Fig. S3, S4). Analysis of a GAPDH crystal structure revealed that all of the pgK-modified lysines are solvent-exposed (Fig. S5) and that the most frequently identified sites of modification (K107, K194 and K215; Table S1) cluster around the GAPDH active site (Fig. 1D). Isoelectric focusing (IEF) revealed a shift in the pI distribution of GAPDH from ~8.6 in GN control reactions to 6.5–7.66 in GGN reactions (Fig. 1E; Fig. S6). This shift is consistent with GAPDH having acquired a net negative change in charge through capping of lysines by phosphoglycerate, a conclusion also supported by LC-MS/MS analysis, which revealed substantial enrichment of pgK-modified peptides in the acidic pI fractions (Fig. S6).

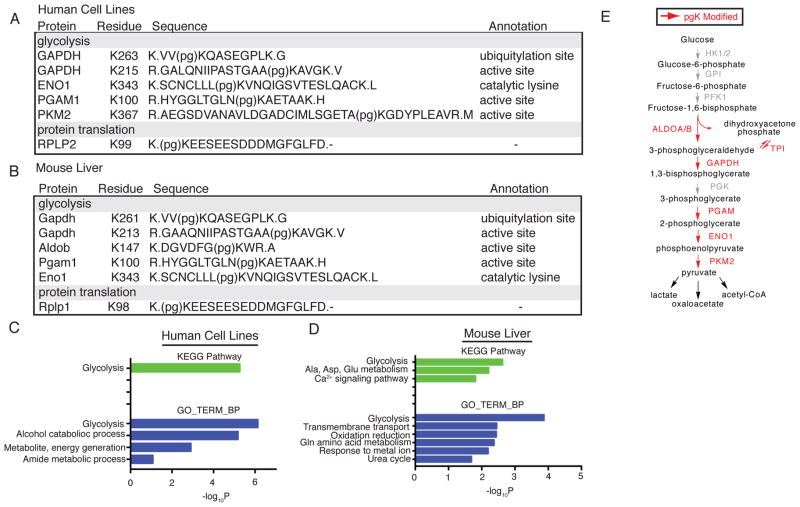

We next assessed the existence and global distribution of pgK modifications in cell proteomes. We reasoned that pgK-peptides might share enough physicochemical properties with phosphorylated peptides to permit enrichment by a standard phosphoproteomic workflow using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC; Fig. S7) (11). pgK-modified lysines were identified in several protein classes in four human cell lines examined (Table S2). Two of the aforementioned pgK-sites observed for GAPDH in vitro were detected in human cells and generated MS/MS spectra that matched the spectra of both the synthetic (Fig. S8) and in vitro-derived (Fig. S3, S4) pgK-modified GAPDH peptides. Meta-analysis of published phosphoproteomic datasets (12, 13) confirmed that pgK-modified proteins are also present in normal mouse tissues and that several pgK sites are conserved in human and mouse enzyme orthologs (Fig. 2A, B; Table S3). Bioinformatic clustering with DAVID software (14) and KEGG pathway analysis revealed enrichment of pgK-modified proteins in glycolysis in both human cells (Fig. 2C; Table S4) and mouse liver (Fig. 2D; Table S4).

Fig. 2.

Functional distribution of pgK modification sites in human cells and mouse tissues. (A, B) Modification site, peptide sequence, and associated annotation for representative endogenous pgK-modified proteins from human cell lines (A) and mouse liver (B). “(pg)K” denotes the pgK-modified lysine. (C, D) Gene ontology biological process categories (GOTERM_BP) and KEGG pathways enriched among pgK-modified proteins in human cell lines (C) and mouse liver (D) by DAVID bioinformatic analysis. (E) Schematic of observed pgK-modified enzymes in glycolysis. Glycolytic enzymes containing at least one pgK-site are shown in red, others are shown in grey.

Examination of the observed modification sites revealed that they often occurred on catalytic or regulatory lysine residues in the active sites of glycolytic enzymes that use three-carbon substrates (Fig. 2A, B, and E; Fig. S9). Notable exceptions were phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK1) and bisphosphoglycerate mutase (BPGM), both of which accept 1,3-BPG as a substrate, but possess active sites predominantly made up of histidine and arginine residues (Fig. S10). These findings indicate that both PGK1 and BPGM may have evolved to possess active sites that are resistant to stable modification by 1,3-BPG. Analysis of the local sequence context surrounding pgK sites revealed no discernible motif (Fig. S11), which is consistent with an enzyme-independent labeling mechanism.

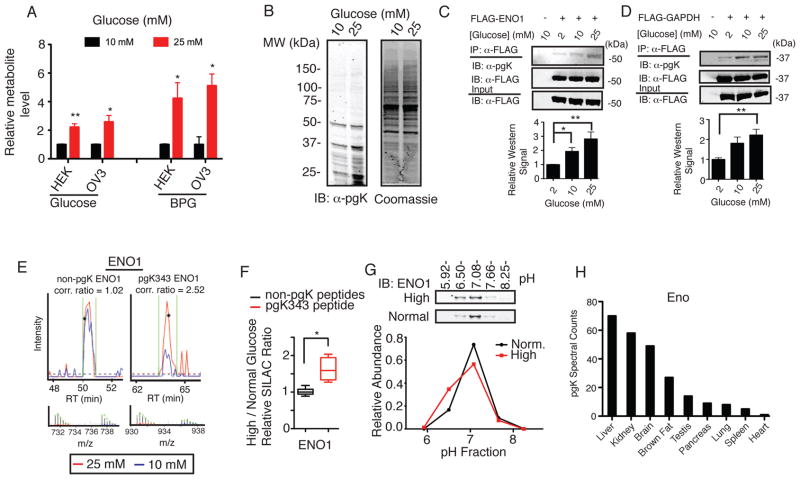

Metabolic labeling with heavy glucose (D-glucose-13C6, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 6-d7) revealed that pgK modifications were derived from glucose metabolism (Fig. S12). We next tested whether changes in glycolytic flux, through altering 1,3-BPG, might dynamically regulate the extent of pgK modifications in cells. We exposed cells to normal (10 mM) or high (25 mM) concentrations of glucose and found that the latter cells, which possessed 4-5-fold elevations in bis-(1,3 and/or 2,3-)phosphoglycerate (Fig. 3A), exhibited greater pgK signals for several proteins (Fig. 3B) as judged by immunoblotting with anti-pgK antibodies (Fig. S13 and Materials and Methods). Similar experiments performed on HEK293T cells expressing FLAG-tagged ENO1 or GAPDH revealed that both proteins showed significant glucose concentration-dependent increases in their pgK modification state (Fig. 3C, D). We also employed the quantitative proteomic method SILAC [stable isotope labeling of amino acids in cell culture (15)] and found that cells grown in 25 mM glucose exhibited increased pgK modification of several proteins, including the active-site lysine of ENO1, K343, without changes in the abundance of non-pgK peptides in these proteins (Fig. 3E, F; table S5; Fig. S14). IEF further established a shift in ENO1 protein to more acidic pH fractions in cells grown in 25 mM glucose (Fig. 3G). Finally, analysis of mouse phosphoproteomic datasets (12), revealed that the extent and distribution of pgK modifications for glycolytic enzymes, as measured by pgK-peptide spectral counts, were highest in liver, brain, and kidney, which are major sites of glucose uptake and glycolytic/gluconeogenic activity in vivo (Fig. 3H; Fig. S15; Table S3) (16).

Fig. 3.

Dynamic coupling of pgK modification to glucose metabolism. (A) Intracellular glucose and bisphosphoglycerate (BPG, aggregate of both 1,3- and 2,3-isomers) levels from cells grown at indicated glucose concentrations for 24 hours. (B) α-pgK immunoblot (IB) and Coomassie-stained gel of proteomes from HEK293T cells grown at indicated glucose concentrations. (C–D) α-pgK IB of α-FLAG-enriched ENO1 (C) and GAPDH (D) expressed in HEK293T cells grown at indicated glucose concentrations. Shown below each blot is a graph of the average relative α-pgK band intensities (n = 4 per group). (E) Representative SILAC chromatograms, MS1 isotope envelopes, and area ratios for non-pgK (left) and pgK-modified (right) peptides from ENO1. Integration area is shown within green bars; asterisk (*) in the chromatogram signifies the triggered MS2 scan. (F) Average SILAC ratios for pgK343-containing and non-pgK ENO1 peptides from cells grown at indicated glucose concentrations. Horizontal line and whiskers represent the mean and 10–90% confidence interval, respectively. (G) IB of IEF-focused ENO1 from MCF7 cells treated grown at indicated glucose concentrations. Plot shows the IEF-focused ENO1 pI distributions quantified by densitometry. (H) Spectral count values for pgK-modified Eno peptides across nine mouse tissues (Table S3). Data represent mean ± s.e.m; statistical significance was determined by two-way t-tests with a Bonferroni correction for C & D and Welch’s correction for F: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005.

We detected pgK-modification of multiple nuclear proteins (Table S2, S3; Fig. S14C, S16A). GAPDH can localize to the nucleus (17) and this distribution is promoted by exposing cells to high concentrations of glucose (18, 19) (Fig. S16B, C), thus providing a potential mechanistic explanation for the glucose-stimulated increase in pgK signals for the nuclear protein NUCKS1 (nuclear ubiquitous casein and cyclin-dependent kinases substrate 1) (Fig. S14C, S16D). We further tested this premise by comparing nuclear pgK profiles in HEK293T cells transfected with wild-type (GAPDH-WT) or nuclear-localized GAPDH (GAPDH-NLS, containing a C-terminal SV40 nuclear localization sequence; Fig. S16E–G). GAPDH-NLS cells exhibited increased pgK signals in a subset of nuclear proteins (Fig. S16H), including NUCKS1 (Fig. S16I).

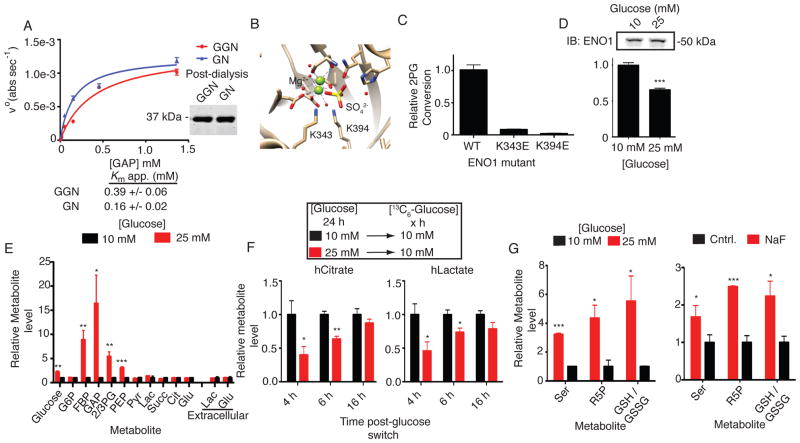

We next assessed the impact of pgK modification on glycolytic enzyme activity. We first compared in vitro pgK-modified (GGN) versus control (GN) GAPDH reactions following dialysis to remove unreacted 1,3-BPG and other metabolites. GAPDH from GGN reactions exhibited an approximately two-fold increase in apparent Km value (Fig. 4A), indicating that the pgK modifications may perturb interactions with GAP substrate. We attempted to mimic 1,3-BPG modification of the catalytic K343 of ENO1 (20), as well as another active site lysine (K394) (Fig. 4B), by generating K-to-E mutations, which displayed substantially reduced activity (Fig. 4C; Fig. S17A). We also found that FLAG-tagged ENO1 enzyme expressed in HEK293T cells showed ~30% lower activity following exposure to 25 mM versus 10 mM glucose for 24 hours (Fig. 4D), which is consistent with our quantitative proteomic findings indicating enhanced pgK modification of K343 in cells exposed to high glucose concentrations (Fig. 3C, E–H).

Fig. 4.

pgK modification impairs glycolytic enzymes and correlates with altered glycolytic output in human cells. (A) Michaelis-Menten kinetic analysis comparing GAPDH from GGN (1,3-BPG-producing) versus GN (control) reactions. (B) Structure of ENO1 active site (PDB Accession: 3B97) showing residues important for catalysis, including pgK sites K343 and K394. (C) Relative activities of wild-type and mutant FLAG-tagged ENO1 expressed and affinity-isolated from HEK293T cells (Fig. S17A for expression data of ENO1 variants). (D) Relative activities of FLAG-isolated ENO1 expressed in HEK293T cells cultured in 10 versus 25 mM glucose for 24 hours. (E) Relative metabolite levels in HEK293T cells grown in 10 versus 25 mM glucose for 24 hours. (F) Relative heavy lactate and citrate levels in HEK293T cells pretreated with the indicated glucose concentrations for 24 hours and then grown in 10 mM heavy-glucose for the indicated length of time. (G) Relative metabolite measurements in cells grown in 10 versus 25 mM glucose (left) or treated with NaF (right). Data shown represent mean ± s.e.m. from triplicate experiments. Statistical significance was determined by two-way t-tests: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.005; n.s., not significant. G6P, glucose-6-phosphate; FBP, fructose-1,6-bisphosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetonephosphate; Pyr, pyruvate; Lac, lactate; Succ, succinate; Glu, glutamate; Ser, serine; R5P, ribulose-5-phosphate; GSH/GSSG, reduced/oxidized glutathione.

We used targeted metabolomics (Table S6) to measure glycolytic and citric acid cycle (CAC) intermediates in human cells exposed to 10 versus 25 mM glucose for 24 hours and, as expected, found higher concentrations of metabolites in the latter condition. However, these increases were not uniform, but mostly restricted to central glycolytic metabolites, including fructose-1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (GAP), phosphoglycerate (both 2- and 3- isomers, 2PG and 3PG) and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) (Fig. 4E; Fig. S17B–D). A similar metabolomic profile was observed in cells cultured in normal glucose and treated with the ENO1 and PKM2 inhibitor NaF (3 mM, 24 hours; Fig. S17E–G). We used pulse-chase experiments with 10 mM 13C-labeled glucose to measure glycolytic flux in cells grown in 10 versus 25 mM glucose for 24 hours. Cells grown in 25 mM glucose showed reduced glycolytic flux and heightened pgK modification at early time points post-chase with 13C-glucose (≤ 6 hours) and these decreases were alleviated by 16 hours (Fig. 4F), which correlated with changes in pgK-signals over the time course (Fig. S17H, I). Finally, the build up of glycolytic metabolites in cells exposed to either high glucose or NaF was accompanied by increased concentrations of metabolites that are biosynthesized from central glycolytic intermediates, including serine, ribulose-5-phosphate, and reduced glutathione (Fig. 4G; Fig. S17J).

We found that a synthetic, pgK-containing tetrapeptide Ac-AA(pg)KA (Fig. S18A) was deacylated (Ac-AAKA) and dephosphorylated [Ac-AA(g)KA; glyceryl-lysine, (g)K] when exposed to native, but not heat-denatured cell lysates or buffer alone (fig. S18B, C), indicating that pgK modifications can be enzymatically metabolized. Broad-spectrum phosphatase inhibitors blocked formation of dephosphorylated and, to a lesser extent, deacylated peptide products (Fig. S18D), suggesting that deacylation may occur directly from pgK-peptides or through a dephosphorylated gK intermediate (Fig. S18E). Kinetic analysis in cell lysates further revealed that deacylation and dephosphorylation reactions occur on similar time scales in cell lysates (Fig. S18F). These data indicate that pgK is a dynamic and reversible PTM.

In summary, we have identified herein a PTM found on numerous mammalian proteins (Table S2, S3) that originates from the reaction of lysines with a primary glycolytic metabolite, 1,3-BPG. This reaction increases the size and inverts the charge potential of the modified residue from positive to negative and therefore has the potential to impact the structure and function of proteins from diverse families and pathways (Fig. S19). 1,3-BPG modification of lysines also likely occurs in lower organisms, given the conservation of glycolysis throughout evolution (21, 22). The enrichment of pgK modification sites on glycolytic enzymes indicates that these enzymes may form a physical complex in cells (23), as has been observed for other metabolic pathways (24). The localization of GAPDH to additional subcellular structures or protein complexes could provide a general mechanism to regulate the pgK-modification state of proteins. An aggregate effect of partial enzyme impairments by pgK-modification in the glycolytic pathway appears to be reduced carbon flow into Lac and CAC intermediates, leading to increased levels of central metabolites, which can be shunted to alternate biosynthetic pathways (Fig. S20) (25, 26). Erythrocytes isolated from patients with a rare deficiency in BPGM, which should increase 1,3-BPG concentrations, show a similar profile to that of cells grown in high concentrations of glucose, with build-up of the central metabolites FBP, GAP, 2PG, 3PG and PEP (27). Thus, pgK modifications could constitute an intrinsic feedback mechanism by which a reactive central metabolite (1,3-BPG) regulates product distribution across the glycolytic pathway in response to changes in glucose uptake and metabolism.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Dix and S. Niessen for assistance with mass spectrometry, C. Wang for support and advice on the use of CIMAGE software and G. Simon for helpful discussions. Supported by the National Institutes of Health (CA087660), the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (R.E.M. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Postdoctoral Fellow) and the Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology.

Footnotes

Materials and Methods

References (29 – 40)

References

- 1.Swint-Kruse L, Matthews KS. Allostery in the LacI/GalR family: variations on a theme. Current opinion in microbiology. 2009 Apr;12:129. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sola-Penna M, Da Silva D, Coelho WS, Marinho-Carvalho MM, Zancan P. Regulation of mammalian muscle type 6-phosphofructo-1-kinase and its implication for the control of the metabolism. IUBMB life. 2010 Nov;62:791. doi: 10.1002/iub.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walsh C. Posttranslational modification of proteins : expanding nature’s inventory. Roberts and Co. Publishers; Englewood, Colo: 2006. p. xxi.p. 490. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang T, Kartika R, Spiegel DA. Exploring post-translational arginine modification using chemically synthesized methylglyoxal hydroimidazolones. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2012 May 30;134:8958. doi: 10.1021/ja301994d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Codreanu SG, Zhang B, Sobecki SM, Billheimer DD, Liebler DC. Global analysis of protein damage by the lipid electrophile 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2009 Apr;8:670. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800070-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paulsen CE, et al. Peroxide-dependent sulfenylation of the EGFR catalytic site enhances kinase activity. Nature chemical biology. 2012 Jan;8:57. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saiardi A, Bhandari R, Resnick AC, Snowman AM, Snyder SH. Phosphorylation of proteins by inositol pyrophosphates. Science. 2004 Dec 17;306:2101. doi: 10.1126/science.1103344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demoss JA, Genuth SM, Novelli GD. The Enzymatic Activation of Amino Acids Via Their Acyl-Adenylate Derivatives. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1956 Jun;42:325. doi: 10.1073/pnas.42.6.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liaw SH, Kuo I, Eisenberg D. Discovery of the ammonium substrate site on glutamine synthetase, a third cation binding site. Protein science : a publication of the Protein Society. 1995 Nov;4:2358. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560041114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patricelli MP, et al. Functional interrogation of the kinome using nucleotide acyl phosphates. Biochemistry. 2007 Jan 16;46:350. doi: 10.1021/bi062142x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Larsen MR, Thingholm TE, Jensen ON, Roepstorff P, Jorgensen TJ. Highly selective enrichment of phosphorylated peptides from peptide mixtures using titanium dioxide microcolumns. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2005 Jul;4:873. doi: 10.1074/mcp.T500007-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huttlin EL, et al. A tissue-specific atlas of mouse protein phosphorylation and expression. Cell. 2010 Dec 23;143:1174. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Primary data (.RAW files) from mouse liver phosphoproteome (SCX-IMAC-enriched) as reported in Huttlin et al., 2010 was downloaded from the Proteome Commons public database. MS2 files were generated with RAW Xtractor and searched for pgK modified peptides using a mouse EBI-IPI forward/reverse proteomic database as discussed in Materials & Methods. False-positive rates were between 0.0 and 0.5%.

- 14.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature protocols. 2009;4:44. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mann M. Functional and quantitative proteomics using SILAC. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2006 Dec;7:952. doi: 10.1038/nrm2067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fueger BJ, et al. Impact of animal handling on the results of 18F-FDG PET studies in mice. Journal of nuclear medicine : official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine. 2006 Jun;47:999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng L, Roeder RG, Luo Y. S phase activation of the histone H2B promoter by OCA-S, a coactivator complex that contains GAPDH as a key component. Cell. 2003 Jul 25;114:255. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00552-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanwar M, Kowluru RA. Role of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase in the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes. 2009 Jan;58:227. doi: 10.2337/db08-1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yego EC, Mohr S. siah-1 Protein is necessary for high glucose-induced glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase nuclear accumulation and cell death in Muller cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010 Jan 29;285:3181. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.083907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sims PA, Larsen TM, Poyner RR, Cleland WW, Reed GH. Reverse protonation is the key to general acid-base catalysis in enolase. Biochemistry. 2003 Jul 15;42:8298. doi: 10.1021/bi0346345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.A review of literature on glycolytic enzyme modification revealed evidence for phosphate-modified forms of GAPDH and ENO1 in bacteria, which were interpreted to potentially correspond to ADP-ribosylation and substrate (2-phosphoglycerate) modified enzymes, respectively (22). Our data offer an additional interpretation of these findings as evidence that 1,3-BPG may also modify glycolytic enzymes in bacteria.

- 22.Boel G, et al. Is 2-phosphoglycerate-dependent automodification of bacterial enolases implicated in their export? Journal of molecular biology. 2004 Mar 19;337:485. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.12.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srere PA. Complexes of sequential metabolic enzymes. Annual review of biochemistry. 1987;56:89. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.000513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.An S, Kumar R, Sheets ED, Benkovic SJ. Reversible compartmentalization of de novo purine biosynthetic complexes in living cells. Science. 2008 Apr 4;320:103. doi: 10.1126/science.1152241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vander Heiden MG, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009 May 22;324:1029. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yi W, et al. Phosphofructokinase 1 glycosylation regulates cell growth and metabolism. Science. 2012 Aug 24;337:975. doi: 10.1126/science.1222278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosa R, Prehu MO, Beuzard Y, Rosa J. The first case of a complete deficiency of diphosphoglycerate mutase in human erythrocytes. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1978 Nov;62:907. doi: 10.1172/JCI109218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.