Abstract

The predictors for seeking alternative therapies for HIV-infection in sub-Saharan Africa are unknown. Among a prospective cohort of 442 HIV-infected patients in Moshi, Tanzania, 249 (56%) sought cure from a newly popularized religious healer in Loliondo (450 kilometers away), and their adherence to antiretrovirals (ARVs) dropped precipitously (OR=0.20, 95% CI, 0.09–0.44, p<0.001) following the visit. Compared to those not attending Loliondo, attendees were more likely to have been diagnosed with HIV more remotely (3.8 vs. 3.0 years prior, p<0.001), have taken ARVs longer (3.4 vs. 2.5 years, p<0.001), have higher median CD4+ lymphocyte counts (429 vs. 354 cells/mm3, p<0.001), be wealthier (wealth index 10.9 vs. 8.8, p = 0.034), and receive care at the private versus the public hospital (p=0.012). In multivariable logistic regression, only years since the start of ARVs remained significant (OR, 1.49, 95% CI, 1.23–1.80). Treatment fatigue may play a role in the lure of alternative healers.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, antiretroviral therapy, adherence, faith healing, traditional healing, Global Health, Africa

Introduction

In 2010 more than 5 million persons living with HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa were receiving antiretroviral therapy, and this number is estimated to increase substantially (1). While antiretroviral adherence in resource-poor settings is as good as, if not better than, that in North America (2–5), adherence may decline over time (3; 6–8).

Well-documented reasons for incomplete antiretroviral adherence in low-resource settings include limited financial resources, transportation barriers, and user fees (9–16); younger age (4; 13); complexity of antiretroviral dosing and side effects (4; 14); stigma and lack of disclosure (11; 13; 17–19); depression (6; 18; 20–22), and active substance abuse (18; 21–23). The influence of traditional or spiritual healers, however, is unclear. Extant reports involve relatively small numbers of individuals reporting sporadic contact with various healers (24–27). None describes a mass phenomenon where a population quickly and suddenly believes in the healing powers of an individual and acts on that belief.

In August 2010 in the remote village of Sumunge, in Loliondo, Tanzania a retired Lutheran minister began offering a one-dose herbal cure for HIV and other chronic illnesses (28). The remedy, for which he charged 500 Tanzanian shillings (approximately 0.31 US dollars), was prepared by saying a prayer, boiling the root of the Mugariga tree (Carissa spinarum), cooling the brew, and dispensing it in cups to participants. As media reports spread across Tanzania and East Africa, tens of thousands of individuals sought healing, and by March 2011 traffic to the village was backed up for 15 kilometers (29). As part of the Coping with HIV/AIDS in Tanzania (CHAT) study (30), a longitudinal cohort study initiated in 2008 to explore associations between psychosocial characteristics, HIV medication adherence, and health outcomes among HIV-infected individuals in Moshi, Tanzania we observed a high proportion of study participants traveling to Loliondo to receive the cure. We describe Loliondo attenders and non-attenders and corresponding antiretroviral adherence rates.

Methods

HIV-infected individuals, ages 18–64, were enrolled from Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre (KCMC, a private zonal referral hospital, N=228) and Mawenzi Regional Hospital (a public facility, N=271) between November 2008 and October 2009. Participants were followed longitudinally using in-person surveys and clinical exams semi-annually and HIV RNA levels annually. Survey instruments included sociodemographic data as well as information on religion and spirituality, beliefs about and interactions with non-traditional healers, self-reported health status (SF-8), HIV testing history, and household assets. The survey instruments were translated from English into Kiswahili and back-translated into English to confirm translation validity. Trained interviewers recorded participant responses using Entryware version 6.4 (Techneous, Vancouver, British Columbia).

This analysis is restricted to participants taking antiretroviral therapy at their last study visit prior to the widespread popularity of the Loliondo healer (N=441). Participants reporting no missed doses in the previous 3 months were considered adherent.

Trends for the general popularity of the Loliondo healer were estimated using Google Insights for Search (www.google.com/insights/search/), which computes the number of searches for a given term relative to the total number of searches over time. For data presented, the term “Loliondo” was used. Loliondo attendance among CHAT participants was captured initially through a follow-up question for clients reporting interactions with traditional healers. Starting in June 2011 patients were asked explicitly if they had personally sought healing at Loliondo from Babu Mwasapile. Loliondo attenders were asked about transportation costs, if they believed that ‘drinking from the cup’ improved or healed their HIV, and if they were advised to stop taking their medications.

During the third wave of surveys (completed by August 2010), participants were asked about involvement in both organizational and non-organizational religious activity: “How often do you attend church or other religious meetings?” and “How often do you spend time in private religious activities, such as prayer, meditation or study of holy scriptures?” (31). Additionally, participants were asked how important for healing is each of the following: faith healing by religious leaders, medical doctors, personal prayer and spirituality, traditional healers, witchdoctors, and herbalists.

Participants were asked to rate their health over the past 4 weeks during semi-annual surveys. At annual clinical assessments, HIV RNA levels were obtained per study protocol and CD4+ lymphocyte counts were abstracted from clinical records. A wealth index consisting of 8 assets and 3 characteristics of the living environment was constructed by applying to each component variable its estimated contribution to the 2010 Tanzania Demographic and Health Survey wealth index (R2 0.9452, Kilimanjaro Region).

Student’s t-tests and logistic regression were used to assess the significance of differences in sociodemographic characteristics, spirituality, health status, HIV medication history and treatment outcomes between Loliondo attendees and non-attendees. The association between Loliondo attendance and adherence was analyzed using a random-effects logistic regression model, where individual-level adherence was modeled as a function of the number of quarters since respondents' Loliondo visit, as well as a linear function of time, the effect of which was allowed to differ between Loliondo attendees and non-attendees.

Results

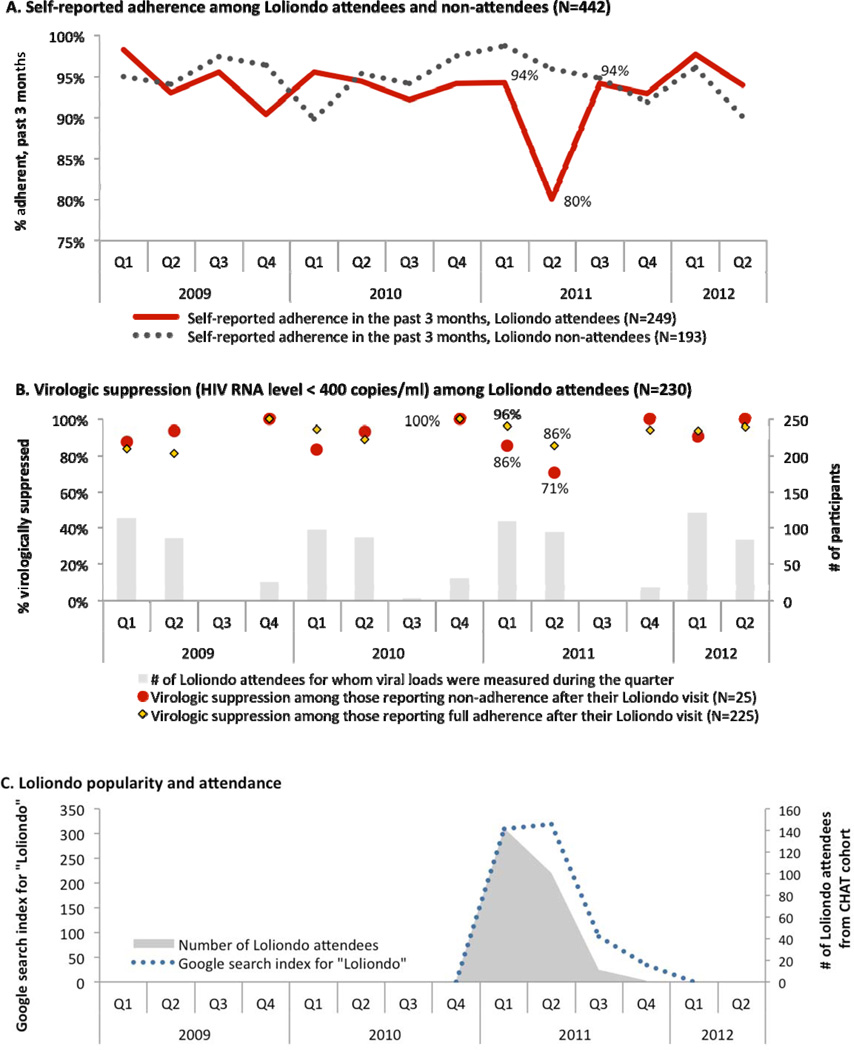

Among 442 CHAT participants on antiretroviral therapy, 249 (56%) reported visiting Loliondo and 240 indicated specifically that they “drank from the grandfather’s cup.” Shown in Panel A of the figure is the proportion of participants, by Loliondo attendance status, reporting complete adherence to antiretroviral therapy during the previous three months. Temporal trends in the number of participants who traveled to Loliondo parallel those of Google searches for “Loliondo” (Panel C). During the second quarter of 2011, following the height of the healer’s popular appeal, adherence rates dropped sharply among Loliondo attenders versus non-attenders, but at subsequent observations, adherence patterns were comparable. The effect of Loliondo attendance on adherence was significant for the first quarter after participants' Loliondo visit (OR = 0.20, 95% confidence interval, 0.09 to 0.44, p<0.001, compared to pre-Loliondo values). We examined rates of virologic failure (increase in HIV RNA level to > 400 copies/ml) among 376 participants who had viral load measurements both before and after the rise in popularity of the Loliondo healer during late 2010. There was no difference in the rate of virologic failure between Loliondo attendees (10/214, 4.7%) vs. non-attendees (9/131, 6.9%, p=0.467). As shown in Panel B of the figure, the rate of virologic suppression below 400 HIV RNA copies/ml was lowest (71%) among Loliondo attendees reporting incomplete adherence during the second quarter of 2011.

In bivariate analysis (see table), Loliondo attenders were more likely than non-attenders to be older (43.2 vs. 40.8 years, p = 0.003), widowed (34.1% vs. 23.3%, p=0.013), and Lutheran (30.6% vs. 21.2%, p=0.027). No differences were found with respect to spiritual practices or beliefs regarding healing. While Loliondo attenders vs. non-attenders perceived no significant differences with respect to their health and had similar nadir CD4+ lymphocyte counts, Loliondo attenders were more likely to have been diagnosed with HIV more remotely (3.8 vs. 3.0 years prior, p<0.001), to have been on antiretroviral therapy longer (3.4 vs. 2.5 years, p<0.001), and to have higher median CD4+ lymphocyte counts (429 vs. 354 cells/mm3, p<0.0001). Loliondo attenders were wealthier than non-attenders (10.9 vs. 8.8, p = 0.034, using predicted wealth index), and attendance was more common among patients of the private referral hospital (p=0.012). In multivariable logistic regression, only years since start of antiretroviral therapy was significant (OR, 1.49, 95% CI, 1.23–1.81).

Table.

Predictors for visiting the Loliondo healer among 442 HIV-infected persons taking antiretroviral therapy in the Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania.

| Bivariate comparisons | Multivariate model (N=355) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attended Loliondo | Did not attend Loliondo |

Odds Ratio | |||||||

| N | Mean (SD) or % | Mean (SD) or % | p-value | [95% CI] | |||||

| Socio-demographics | Female | 442 | 70.3 | 65.8 | 0.317 | 1.162 | [0.657 – 2.055] | ||

| Age | 442 | 43.2 | (8.6) | 40.8 | (7.9) | 0.003 | 1.023 | [0.992 – 1.055] | |

| Secondary education | 441 | 21.0 | 19.7 | 0.742 | 1.352 | [0.679 – 2.691] | |||

| Urban residence | 441 | 39.5 | 46.6 | 0.134 | 0.823 | [0.494 – 1.370] | |||

| Marital status | Married | 442 | 35.3 | 40.9 | 0.230 | ref | |||

| Widowed | 442 | 34.1 | 23.3 | 0.013 | 1.417 | [0.750 – 2.679] | |||

| Divorced | 442 | 16.9 | 21.2 | 0.244 | 1.367 | [0.682 – 2.737] | |||

| Single | 442 | 13.7 | 14.5 | 0.798 | 1.674 | [0.770 – 3.636] | |||

| Religion | Catholic | 441 | 42.7 | 43.0 | 0.956 | ref | |||

| Lutheran | 441 | 30.6 | 21.2 | 0.027 | 1.767 | [0.962 – 3.247] | |||

| Muslim | 441 | 19.0 | 25.9 | 0.081 | 0.804 | [0.421 – 1.538] | |||

| Other | 441 | 7.7 | 9.8 | 0.419 | 0.605 | [0.260 – 1.410] | |||

| Spirituality | Frequency of church/religious service attendance | 410 | 0.9 | (0.3) | 0.9 | (0.3) | 0.988 | 0.819 | [0.411 – 1.633] |

| Frequency of time spent in private religious activities | 410 | 0.4 | (0.5) | 0.4 | (0.5) | 0.342 | 1.010 | [0.536 – 1.904] | |

| Importance for healing of: | Faith healing | 408 | 2.4 | (1.3) | 2.3 | (1.2) | 0.549 | 1.216 | [0.963 – 1.535] |

| Medical doctors | 410 | 4.1 | (0.6) | 4.0 | (0.6) | 0.414 | 0.866 | [0.574 – 1.307] | |

| Personal prayer | 410 | 3.1 | (1.2) | 3.2 | (1.0) | 0.591 | 0.878 | [0.685 – 1.126] | |

| Traditional healers | 410 | 1.1 | (0.4) | 1.0 | (0.2) | 0.481 | 0.916 | [0.408 – 2.055] | |

| Health | SF-8TM Score | 442 | 1.5 | (0.4) | 1.6 | (0.6) | 0.066 | 1.024 | [0.587 – 1.787] |

| Nadir CD4+ lymphocyte count (cells/mm3) | 439 | 158.7 | (158.2) | 144.1 | (112.5) | 0.279 | omitted | ||

| Most recent CD4+ lymphocyte count (cells/mm3) | 439 | 429.2 | (223.3) | 354.1 | (195.1) | <0.001 | 1.000 | [0.998 – 1.001] | |

| Years since diagnosis | 441 | 3.8 | (1.9) | 3.0 | (1.7) | <0.001 | omitted | ||

| Years since start of ART | 407 | 3.4 | (1.7) | 2.5 | (1.4) | <0.001 | 1.489* | [1.229 – 1.805] | |

| WHO stage 3 or 4 | 436 | 66.8 | 70.9 | 0.362 | 0.615 | [0.352 – 1.074] | |||

| Cohort | KCMC | 442 | 53.0 | 40.9 | 0.012 | ref | |||

| Mawenzi | 442 | 47.0 | 59.1 | 0.012 | 0.929 | [0.459 – 1.881] | |||

| Predicted wealth index | 408 | 10.9 | (9.4) | 8.8 | (9.3) | 0.034 | 1.022 | [0.993 – 1.052] | |

SF-8™, Short Form 8 (a self-reported measure of health); WHO, World Health Organization; KCMC, Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Centre. Nadir CD4+ lymphocyte count and years since diagnosis were omitted from multivariate logistic regression because of collinearity;

indicates significance at p<0.001.

The median transportation cost to attend Loliondo was 80,000 Tanzanian shillings (IQR 60,000 –100,000, 51 US dollars, N=241). One quarter of Loliondo attenders (57/234) believed that the treatment improved or healed their HIV infection. Twelve of 226 (5%) reported being advised to stop taking their HIV medications. Of 12 who reported discontinuing medications, 6 resumed medications within two weeks.

Discussion

The majority of participants taking antiretrovirals in this cohort from Northern Tanzania sought an herbal cure for HIV from a spiritual leader. Visiting the healer was associated with a significant, but impermanent, decline in antiretroviral adherence. Treatment fatigue appeared to play a significant role in the lure of the healer, as duration of antiretroviral use was independently associated with attendance. Other factors, including those not measured, likely played a role. Being older, widowed, and Lutheran (the denomination of the healer), having been diagnosed with HIV longer ago and engaged in HIV care for longer, attending a particular clinic, and having higher predicted wealth were each associated with Loliondo attendance in bivariate analysis. Prior measures of spirituality and beliefs about divine healing did not predict attendance. The possibility of cure, even from a healer outside of one’s religious tradition, was so attractive that many patients were willing to incur significant costs, travel for hours, and disrupt years of sustained ART adherence. Insignificant decreases in virologic suppression among Loliondo attenders, including the subgroup reporting incomplete adherence, were noted. That these changes were insignificant is likely a function of both resumed adherence and the temporal disconnect, at the individual patient level, between Loliondo attendance, adherence assessments and viral load measurements.

The interaction between religiosity and adherence to antiretroviral adherence in sub-Saharan Africa is complex. For example, Zou et al. found that 81% of 438 urban and rural Tanzanian church-goers believed that HIV could be cured by prayer; however, a large majority of respondents (94%) indicated they would start antiretrovirals if diagnosed with HIV infection (32). Kisenyi, in a cross-sectional study of 220 Ugandan patients on antiretroviral therapy, found higher adherence levels correlated with greater behavioral religiosity (33). On the other hand, rare instances of HIV-infected patients discontinuing antiretrovirals as a result of belief of healing through spiritual means have been clearly documented (24). Less is known about the appeal of herbal remedies. In Uganda, one third of 401 patients on antiretroviral therapy reported using herbal medicines, primarily to treat symptoms such as fever or cough; lower antiretroviral adherence was associated with use of herbal medicine, but it did not appear that patients were taking herbal medications explicitly as a substitute for HIV therapy (34).

The combination of faith healing and traditional herbal medicine offered by the widely-publicized Loliondo healer presented an attractive opportunity for people facing a lifetime of medication to maintain health. The significant decline in adherence associated with Loliondo attendance highlights the marketability of hope for a true HIV cure, especially among those who have taken antiretroviral therapy for longer, and underscores the importance of ongoing patient education regarding alternative therapies.

We note several limitations of this report. As an observational study, we identify associations but cannot invoke causality. Multiple key measures, including adherence to antiretroviral therapy and Loliondo attendance were self-reported, raising the possibility of social desirability bias. Identical adherence questions, however, were asked repeatedly, and it is unlikely that respondents would provide socially desirable answers during one survey over another. In addition, adherence was measured solely using self-reports. It also possible that some who reported not attending Loliondo did actually attend. However, given the popularity of the healer (29), the absence of stigma attached with attendance, and an emphasis on confidentiality during the survey process, it seems doubtful that participants would mischaracterize participation to surveyors. Finally, the data were collected using structured survey instruments, and qualitative interviews were not performed.

The findings from this study have implications for researchers, policy makers, and care providers. Further research is needed to understand the trade-offs patients make in seeking the uncertainty of a one-time cure in exchange for adherence to proven life-saving medications. Would the lure have been the same if a physical element (namely, drinking from the cup) had not been present? Was the perceived cure thought to be effected more by the herbal drink or by divine healing? What social dynamics led to the rapid rise and then the rapid decline in popularity of the healer? Why did adherence rates improve with continued observation? Robust, mixed-methods techniques and interdisciplinary research will be required to answer these and other questions. Policy makers should consider ways to engage spiritual and religious leaders in respectful dialogue that seeks bidirectional understanding of the theological, social, and medical issues at stake for HIV-infected individuals who seek alternate therapies. Finally, findings from this this study have implications for HIV providers and others caring for patients with chronic diseases. Medical providers are rarely trained to engage patients about religious beliefs and spiritual practices, much less probe patients’ interactions with various healers. In the US, physicians are divided regarding how best to broach the topic (35). Healthcare providers may hold stereotypes about the “kind of patient” who holds particular beliefs and therefore refrain from conversations about the beliefs and practices. The provision of care to patients who are drawn to non-medical cures requires awareness, sensitivity, and compassion to negotiate effective and acceptable treatment strategies within that patient’s worldview.

Conclusion

More than half of the HIV-infected patients in this cohort participated in a highly publicized religious healing activity, and participation was temporally associated with decreased antiretroviral adherence. Only the duration of time since starting antiretroviral therapy was independently associated with participation. Recognizing and addressing the lure of alternative cures for HIV infection and their impact on adherence is critical to the continued success of HIV care and treatment programs in resource-poor settings.

Figure.

Self-reported 3 month antiretroviral adherence rates among a cohort of HIV-infected patients in Kilimanjaro Region, Tanzania (panel A); virologic suppression among Loliondo attendees, by self-reports of adherence (panel B); temporal trends in internet Google searches for “Loliondo” and in visits to the Loliondo healer among the cohort (panel C).

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH078756. The project also received support from the Duke Center for AIDS Research, 5P30-AI064518-08. KL2 RR024127-04 provided salary support for Dr. Reddy. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Data presented in part at the 19th International AIDS Conference, Washington, DC, Abstract no. MOPE436, July 22–27, 2012.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions:

Study concept: NT, JO, KW, BP, ER

Data acquisition: RW, DI, VM

Analysis: JO, NT, KW, BP, ER

Drafting Manuscript: NT, ER, JO

Approval of final manuscript: All

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global HIV/AIDS response epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access : progress report 2011. Global HIV/AIDS response epidemic update and health sector progress towards Universal Access : progress report 2011. 2011

- 2.Mills EJ, Nachega JB, Buchan I, Orbinski J, Attaran A, Singh S, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa and North America: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006 Aug 8;296(6):679–690. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.6.679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nachega JB, Hislop M, Nguyen H, Dowdy DW, Chaisson RE, Regensberg L, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence, virologic and immunologic outcomes in adolescents compared with adults in southern Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 May 5;51(1):65–71. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318199072e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Orrell C, Bangsberg DR, Badri M, Wood R. Adherence is not a barrier to successful antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS. 2003 Jun 6;17(9):1369–1375. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200306130-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Unge C, Södergård B, Ekström AM, Carter J, Waweru M, Ilako F, et al. Challenges for scaling up ART in a resource-limited setting: a retrospective study in Kibera, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009 Apr 4;50(4):397–402. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318194618e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byakika-Tusiime J, Crane J, Oyugi JH, Ragland K, Kawuma A, Musoke P, Bangsberg DR. Longitudinal antiretroviral adherence in HIV+ Ugandan parents and their children initiating HAART in the MTCT-Plus family treatment model: role of depression in declining adherence over time. AIDS Behav. 2009 Jun;13(Suppl):182–191. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9546-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox MP, Rosen S. Patient retention in antiretroviral therapy programs up to three years on treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, 2007–2009: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2010 Jun;15(Suppl):11–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02508.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mannheimer SB, Matts J, Telzak E, Chesney M, Child C, Wu AW, et al. Quality of life in HIV-infected individuals receiving antiretroviral therapy is related to adherence. AIDS Care. 2005 Jan;17(1):10–22. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331305098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lanièce I, Ciss M, Desclaux A, Diop K, Mbodj F, Ndiaye B, et al. Adherence to HAART and its principal determinants in a cohort of Senegalese adults. AIDS. 2003 Jul;17(Suppl):3S103–3S108. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200317003-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Byakika-Tusiime J, Oyugi JH, Tumwikirize WA, Katabira ET, Mugyenyi PN, Bangsberg DR. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy in HIV+ Ugandan patients purchasing therapy. Int J STD AIDS. 2005 Jan;16(1):38–41. doi: 10.1258/0956462052932548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramadhani HO, Thielman NM, Landman KZ, Ndosi EM, Gao F, Kirchherr JL, et al. Predictors of incomplete adherence, virologic failure, and antiviral drug resistance among HIV-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2007 Dec 12;45(11):1492–1498. doi: 10.1086/522991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, Biraro IA, Wyatt MA, Agbaji O, et al. Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med. 2009 Jan 1;6(1):e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Charurat M, Oyegunle M, Benjamin R, Habib A, Eze E, Ele P, et al. Patient retention and adherence to antiretrovirals in a large antiretroviral therapy program in Nigeria: a longitudinal analysis for risk factors. PLoS One. 2010;5(5):e10584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hardon AP, Akurut D, Comoro C, Ekezie C, Irunde HF, Gerrits T, et al. Hunger, waiting time and transport costs: time to confront challenges to ART adherence in Africa. AIDS Care. 2007 May;19(5):658–665. doi: 10.1080/09540120701244943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tuller DM, Bangsberg DR, Senkungu J, Ware NC, Emenyonu N, Weiser SD. Transportation costs impede sustained adherence and access to HAART in a clinic population in southwestern Uganda: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2010 Aug;14(4):778–784. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9533-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rachlis BS, Mills EJ, Cole DC. Livelihood security and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in low and middle income settings: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e18948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birbeck GL, Chomba E, Kvalsund M, Bradbury R, Mang'ombe C, Malama K, et al. Antiretroviral adherence in rural Zambia: the first year of treatment availability. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009 Apr;80(4):669–674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Do NT, Phiri K, Bussmann H, Gaolathe T, Marlink RG, Wester CW. Psychosocial factors affecting medication adherence among HIV-1 infected adults receiving combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) in Botswana. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2010 Jun;26(6):685–691. doi: 10.1089/aid.2009.0222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bajunirwe F, Arts EJ, Tisch DJ, King CH, Debanne SM, Sethi AK. Adherence and treatment response among HIV-1-infected adults receiving antiretroviral therapy in a rural government hospital in Southwestern Uganda. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2009;8(2):139–147. doi: 10.1177/1545109709332470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Amberbir A, Woldemichael K, Getachew S, Girma B, Deribe K. Predictors of adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected persons: a prospective study in Southwest Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2008:8265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakimuli-Mpungu E, Bass JK, Alexandre P, Mills EJ, Musisi S, Ram M, et al. Depression, Alcohol Use and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2011 Nov 11; doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Etienne M, Hossain M, Redfield R, Stafford K, Amoroso A. Indicators of adherence to antiretroviral therapy treatment among HIV/AIDS patients in 5 African countries. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2010;9(2):98–103. doi: 10.1177/1545109710361383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dahab M, Charalambous S, Karstaedt AS, Fielding KL, Hamilton R, La Grange L, et al. Contrasting predictors of poor antiretroviral therapy outcomes in two South African HIV programmes: a cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2010:10430. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wanyama J, Castelnuovo B, Wandera B, Mwebaze P, Kambugu A, Bangsberg DR, Kamya MR. Belief in divine healing can be a barrier to antiretroviral therapy adherence in Uganda. AIDS. 2007 Jul 7;21(11):1486–1487. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32823ecf7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eholié S-P, Tanon A, Polneau S, Ouiminga M, Djadji A, Kangah-Koffi C, et al. Field adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected adults in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007 Jul 7;45(3):355–358. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31805d8ad0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roura M, Busza J, Wringe A, Mbata D, Urassa M, Zaba B. Barriers to sustaining antiretroviral treatment in Kisesa, Tanzania: a follow-up study to understand attrition from the antiretroviral program. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009 Mar;23(3):203–210. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Musheke M, Bond V, Merten S. Individual and contextual factors influencing patient attrition from antiretroviral therapy care in an urban community of Lusaka, Zambia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15(Suppl):11–19. doi: 10.7448/IAS.15.3.17366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malebo HM, Mbwambo ZH. Technical Report on Miracle Cure Prescribed by Rev. Ambilikile Mwasupile In Samunge Village, Loliondo, Arusha. Technical Report on Miracle Cure Prescribed by Rev. Ambilikile Mwasupile In Samunge Village, Loliondo, Arusha. 2011. [cited 2011, Oct 10]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ashforth A. AIDS, religious enthusiasm and spiritual insecurity in Africa. Glob Public Health. 2011;6(Suppl):2S132–2S147. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.602702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pence, Shirey BWA, Whetten KA, Agala KA, Itemba BA, Adams DA, et al. Prevalence of Psychological Trauma and Association with Current Health and Functioning in a Sample of HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected Tanzanian Adults. PLoS ONE. 2012 May;7(5):e36304. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koenig HG, Büssing A. The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A Five-Item Measure for Use in Epidemological Studies. Religions. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou J, Yamanaka Y, John M, Watt M, Ostermann J, Thielman N. Religion and HIV in Tanzania: influence of religious beliefs on HIV stigma, disclosure, and treatment attitudes. BMC Public Health. 2009:975. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kisenyi R, Muliira J, Ayebare E. Religiosity and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy Among Patients Attending a Public Hospital-Based HIV/AIDS Clinic in Uganda. Journal of Religion and Health. 2011:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s10943-011-9473-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Namuddu B, Kalyango JN, Karamagi C, Mudiope P, Sumba S, Kalende H, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with traditional herbal medicine use among patients on highly active antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2011:11855. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curlin FA, Chin MH, Sellergren SA, Roach CJ, Lantos JD. The association of physicians' religious characteristics with their attitudes and self-reported behaviors regarding religion and spirituality in the clinical encounter. Med Care. 2006 May;44(5):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000207434.12450.ef. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]