Summary

Background

Metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a rare but life-threatening condition. Prior estimates of overall survival (OS) from time of diagnosis of distant metastasis to death are approximately 8–14 months. However, these estimates are based on analyses of case reports published prior to 1984.

Objectives

To assess an updated OS in patients with metastatic BCC at a single academic institution.

Methods

Using patients seen from 1997 to 2011, a retrospective chart review was performed on biopsy-confirmed cases of distant metastatic BCC at Stanford University School of Medicine. Kaplan–Meier analysis was used to determine OS and progression-free survival (PFS).

Results

Ten consecutive cases of distant metastatic BCC were identified. Median OS was 7·3 years [95% confidence interval (CI) 1·6–∞]; median PFS was 3·4 years (95% CI 1·1–5·2).

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that OS in patients with distant metastatic BCC may be more favourable than previously reported.

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is the most common human cancer worldwide.1 In the U.S.A. more than 2·8 million cases of BCC are reported annually.2 While the majority of BCCs are cured following diagnosis and treatment, a very small percentage metastasize, with distant metastatic BCC rates estimated to range from 0·0028% to 0·55%.3 Due to the rarity of metastatic BCC, its associated clinical course is not well characterized. To date, there have been fewer than 300 case reports of metastatic BCC since the first case published in 1894 by Beadles.3,4

Historically, metastatic BCC has been reported to have an extremely poor prognosis, based largely on retrospectively collected case reports.5,6 Median overall survival (OS) for meta-static BCC was last reported in 1984 as 8–14 months. In addition, those calculations included metastatic basosquamous carcinoma.5,6 Currently, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines categorize basosquamous carcinoma under squamous cell carcinoma due to its more aggressive clinical course.7

The purpose of this study is to provide updated OS and progression-free survival (PFS) times for patients diagnosed with distant metastatic BCC, excluding metastatic basosquamous carcinomas.

Materials and methods

Following Stanford University Institutional Board approval, a retrospective review was performed of all BCCs in the Stanford Cancer Center Research Database (SCCRD), which includes comprehensive clinic and hospital records from 1997 to 2011. In order to ensure that all relevant cases were included, a combination of search terms was used to interrogate the SCCRD: ‘metastatic basal cell carcinoma’, as well as ‘metastatic’ and ‘basal cell carcinoma’ together. Presumptive cases were reviewed and were excluded if there was no documentation of both cutaneous and distant metastatic BCC in the patient. Patients were included only if there was pathology showing BCC at a distant noncutaneous site confirmed by a board-certified dermatopathologist. If the histology relating to the metastasis was reported as ‘basosquamous’, the patient was excluded from the study.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to determine OS and PFS rates. For OS, all-cause date of death was based on either documentation that the patient was deceased in the medical record or by using the Social Security Death Index (SSDI), a national database updated weekly. The SSDI is a validated source of death outcome in patients where death was not noted in the medical record.8 All patients who were alive at the data cut-off date of 1 December 2011 were confirmed to be alive either by their attendance at clinic visits or by documented telephone calls in their medical records after the data cut-off date.

For PFS, disease progression following documented diagnosis of distant metastasis was defined as the date of first reported metastatic tumour enlargement, additional metastatic lesions, recurrence of metastatic lesion(s) or death. This was determined using the treating physician’s assessments as recorded in the medical record, as well as data from radiological reports. If the patient did not have disease progression, time from diagnosis of metastasis to date of last dermatology record before the data cut-off date of 1 December 2011 was used.

All statistical analyses were carried out using Microsoft Excel 2007 or SAS version 9.2 (SAS Inc., Cary, NC, U.S.A.).

Results

We confirmed and included 10 patients with distant meta-static BCC. Table 1 shows the demographic, clinical and tumour characteristics of these patients. Nine of the 10 patients were male. The mean age at diagnosis of distant met-astatic BCC was 66·0 years (SD 13.0). Fifty percent of the patients had a primary cutaneous BCC on the head, 30% were on the chest and 20% on the back. Seven patients had a BCC metastasis to the lungs, two patients had metastasis to the bone and one patient had metastasis to the lungs, bone and lymph node. Five patients had a metastatic lesion with an infiltrative BCC histological subtype. One patient had Gorlin syndrome.

Table 1.

Demographic, clinical and tumour characteristics of 10 patients with biopsy-confirmed distant metastatic basal cell carcinoma

| Case | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of distant metastasis (years)a | 65 | 78 | 62 | 77 | 42 | 55 | 89 | 66 | 70 | 56 |

| Sex | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | F | M |

| Location of primary tumour | Jaw | Chest | Back | Back | Scalp | Chest | Preauricular | Chest | Nasal ala | Head |

| Site of distant metastasis | ||||||||||

| Lung | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| Bone | X | X | X | |||||||

| Distant lymph node | X | |||||||||

| Treatment types | ||||||||||

| Surgery | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Radiation | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| Surgery with adjuvant radiation | X | X | X | |||||||

| Chemotherapyb | X | X | X | |||||||

| Smoothened inhibitorc | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||||

| Histological subtype of distant metastatic lesion | Morphoeaform | Infiltrative | Poorly differentiated basaloid | Infiltrative | Poorly differentiated basaloid | Infiltrative | Infiltrative | Nodular | Infiltrative | Nodular |

| Years to death (if alive, years from distant metastasis diagnosis)d | Alive (4·5) | Alive (1·6) | Alive (5·8) | 5 | 7 | Alive (7·8) | 2 | Alive (3·0) | Alive (0·6) | Alive (1·8) |

| Years to progression (if no progression, years to last record)d | (2·3) | 1·1 | 2 | 3·4 | 2 | 5·2 | (0·5) | (3·5) | (0·7) | (1·74) |

M, male; F, female.

Mean age (SD); 66 (13) years.

Types of chemotherapy included carboplatin, cisplatin, doxorubicin, docetaxel and methotrexate. All patients receiving chemotherapy had more than one type of chemotherapy.

The smoothened inhibitor used was oral vismodegib.

Date of data cut-off for all patients was 1 December 2011.

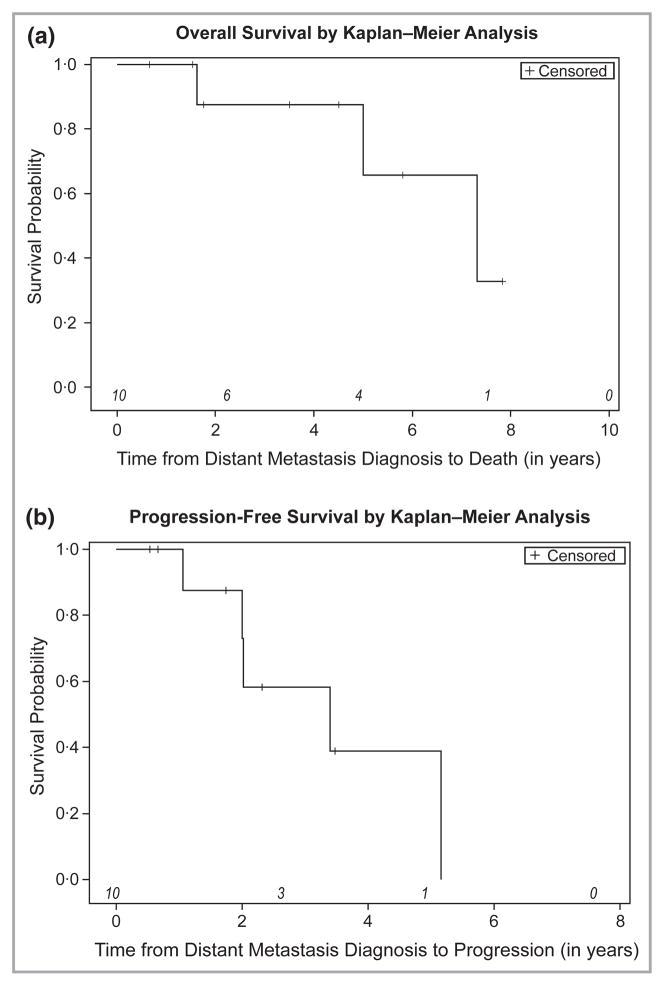

Seven of the 10 patients were alive at our data cut-off date of 1 December 2011 (Fig. 1a). Median OS from the date of diagnosis of distant metastatic BCC to death was 7·32 years [95% confidence interval (CI) 1·62–∞] (Fig. 1a). Median PFS from the date of diagnosis of distant metastatic BCC to progressive disease was 3·40 years (95% CI 1·06–5·16) (Fig. 1b). We attempted to examine the effect of treatment type on OS and PFS; however, the small sample size precluded meaningful analyses.

Fig 1.

Overall survival and progression-free survival of 10 consecutive patients from time of diagnosis of distant, biopsy-confirmed metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BCC). At-risk patients are indicated in italics. (a) Kaplan–Meier analysis for overall survival from date of diagnosis of distant metastatic BCC to death (N = 10). (b) Kaplan–Meier analysis for progression-free survival from date of diagnosis of distant metastatic BCC to disease progression (N = 10).

Five patients had medical records that indicated the initial treatments for the presumed primary, and if the treatment was considered adequate or curative. Of these five patients, two had surgery and three had surgery with adjuvant radiation. All three patients who were treated with surgery and adjuvant radiation for the primary skin lesion had subsequently progressed to more advanced disease.

Discussion

Previous estimates of OS for metastatic BCC are not only outdated, but also included metastatic basosquamous carcinomas.5,6 As current NCCN guidelines categorize basosquamous carcinomas with squamous cell carcinomas, it is important to determine the OS for metastatic BCC of only pure BCC histology. Our study reports markedly prolonged OS for patients with metastatic BCC, excluding metastatic basosquamous carcinoma.

Besides the exclusion of metastatic basosquamous carcinoma, the OS may be increased compared with prior reports for additional reasons. Firstly, it is possible that previous studies may have been biased in favour of more aggressive meta-static BCC cases, as cases reported in the literature were used to determine OS rather than using consecutive cases at a single institution or a tumour registry.5,6,9 Secondly, it is possible that this current study may have been biased in favour of healthier patients, as patients who can withstand travel to a tertiary care institution are more likely to be referred for care.10 Other reasons for improved OS may include advances in surgical techniques, radiotherapy, chemotherapy or treatments for comorbid medical conditions compared with 1975–85, when the last analyses were performed.5,6 For instance, in reviewing prior reports, patients with metastatic BCC were treated with chemotherapies such as cyclophosphamide and 5-fluorouracil, as well as injection of radioactive phosphorus into lymph nodes.6 None of the patients in our study received these treatments but instead were treated with newer treatments such as a smoothened inhibitor. Several case reports from the last 5 years describe patients with complete response to treatment, lending support to the idea that newer treatments such as smoothened inhibitors and combinations of chemotherapy and radiation may be more effective for meta-static BCC.3,11,12

Although limited by a small sample size, our study suggests markedly prolonged OS among patients with distant metastatic BCC compared with previous reports. Seven of 10 patients were still alive at the time of our data cut-off point, and so our OS may even be an underestimate of the actual OS.

Future studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up times will be critical to determine the clinical factors or treatment modalities that impact OS and PFS in distant meta-static BCC.

What’s already known about this topic?

The estimate of overall survival (OS) from date of diagnosis of distant metastatic basal cell carcinoma (BCC) to death is 8–14 months.

This estimate was published in 1984 and needs to be updated.

What does this study add?

We explored OS in a series of patients from 1997 to 2011 at Stanford Hospital and Clinics.

Our findings suggest that OS in patients with metastatic BCC may be more favourable than previously reported.

Acknowledgments

Funding sources

C.D. was supported by the Stanford Medical Scholars Research Program. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

The authors acknowledge the assistance of Youn Kim, MD and Susan Swetter, MD for comments, review and critical reading of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

A.L.S.C., A.E.O. and A.C. have been investigators of studies sponsored by Genentech, Infinity and Novartis. This study was presented as oral and poster presentations at the Society for Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting in Raleigh, NC, U.S.A., 9–12 May 2012.

References

- 1.Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283–7. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2010.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skin Cancer Foundation. [last accessed 17 April 2013];Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC) Available at: http://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/basal-cell-carcinoma.

- 3.Alonso V, Revert A, Monteagudo C, et al. Basal cell carcinoma with distant multiple metastases to the vertebral column. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:748–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beadles CF. Rodent ulcer. Trans Pathol Soc London. 1894;45:175–81. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Domarus H, Stevens PJ. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: report of five cases and review of 170 cases in the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;10:1043–60. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(84)80334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farmer ER, Helwig EB. Metastatic basal cell carcinoma: a clinico-pathological study of seventeen cases. Cancer. 1980;46:748–57. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800815)46:4<748::aid-cncr2820460419>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers Version 2.2012. Fort Washington, PA: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quinn J, Kramer N, McDermott D. Validation of the social security death index (SSDI): an important readily-available outcomes database for researchers. West J Emerg Med. 2008;9:6–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Affleck AG, Gore A, Millard LG, et al. Giant primary basal cell carcinoma with fatal hepatic metastases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:262–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01834.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jong KE, Smith DP, Yu XQ, et al. Remoteness of residence and survival from cancer in New South Wales. Med J Aust. 2004;180:618–22. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2004.tb06123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Amin SH, Tibes R, Kim JE, Hybarger CP. Hedgehog antagonist GDC-0449 is effective in the treatment of advanced basal cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2456–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.21145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2171–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]