Abstract

Background

Facing frequent stigma and discrimination, many people with mental illness have to choose between secrecy and disclosure in different settings. Coming Out Proud (COP), a 3-week peer-led group intervention, offers support in this domain in order to reduce stigma’s negative impact.

Aims

To examine COP’s efficacy to reduce negative stigma-related outcomes and to promote adaptive coping styles (Current Controlled Trials number: ISRCTN43516734).

Method

In a pilot randomised controlled trial, 100 participants with mental illness were assigned to COP or a treatment-as-usual control condition. Outcomes included self-stigma, empowerment, stigma stress, secrecy and perceived benefits of disclosure.

Results

Intention-to-treat analyses found no effect of COP on self-stigma or empowerment, but positive effects on stigma stress, disclosure-related distress, secrecy and perceived benefits of disclosure. Some effects diminished during the 3-week follow-up period.

Conclusions

Coming Out Proud has immediate positive effects on disclosure- and stigma stress-related variables and may thus alleviate stigma’s negative impact.

People with mental illness face stigma and discrimination,1,2 and public stigma has not decreased during recent decades.3 Many people with mental illness internalise public negative attitudes, resulting in self-stigma. Self-stigma and its consequences have been conceptualised as the opposite of empowerment;4,5 self-stigma is associated with a number of negative outcomes such as giving up life goals,6 social withdrawal, keeping one’s mental illness secret7 and perception of stigma as a threat and stressor that exceeds one’s coping resources.8,9 Initial evidence suggests that psychoeducational, cognitive-behavioural or narrative interventions can reduce self-stigma.10-16 Since these approaches often only have small to medium effects10 and since disclosure has been proposed as an alternative approach to reduce stigma’s negative impact, Coming Out Proud (COP) was developed as a manualised peer-led group intervention that takes a new approach to reduce stigma’s negative impact on individuals with mental illness. Based on findings among individuals from sexual minorities and among people with mental illness that secrecy can be a harmful coping strategy and that disclosure or ‘coming out’ can reduce self-stigma,7,17-20 Corrigan and colleagues developed COP as a three-session intervention that focuses on three topics, one per session: (a) risks and benefits of secrecy and disclosure in different settings; (b) levels of disclosure, between the extremes of social withdrawal/secrecy and broadcasting one’s experience with mental illness; and (c) on helpful ways to tell one’s story with mental illness, again in different settings. Coming Out Proud aims to empower individuals to make a personal choice, whether or not they decide to disclose.21,22 So far, empirical data on COP’s feasibility and efficacy are lacking. We therefore conducted a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) with the aim of investigating (a) the feasibility of recruiting and retaining people with mental illness to a COP trial, and (b) COP’s efficacy to reduce self-stigma, stigma stress, disclosure-related distress and secrecy as well as to increase empowerment, perceived benefits of being out and disclosure-related self-efficacy.

Method

Study design and participants

Our intention-to-treat parallel randomised pilot trial compared the COP intervention, combined with treatment as usual (TAU), with a control group that received only TAU. The type of TAU was not prespecified. All individuals were informed that study participation would neither require current mental health service use nor interfere with any treatment. The majority of participants received psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy during the time of the study.

We recruited participants in the region of Zürich, Switzerland, between October 2012 and March 2013. Inclusion criteria were: at least one self-reported current Axis I or Axis II disorder according to DSM-IV;23 age 18 or above; sufficient German language skills; at least a moderate level of self-reported disclosure-related distress (score 4 or higher on the screening item ‘In general, how distressed or worried are you with respect to secrecy or disclosure of your mental illness to others?’, rated from 1, not at all, to 7, very much). Exclusion criteria were current in-patient status; organic disorder, dementia or intellectual disability; or self-reported diagnosis of only a substance- or alcohol-related disorder, without non-substance-related current psychiatric comorbidity, since disclosure of substance use disorders is not a focus of COP. The regional Zürich Ethics Committee approved the trial and all participants provided written consent after being fully informed about study procedures. The trial is registered with Current Controlled Trials: ISRCTN43516734.

The study was advertised using leaflets and posters in psychiatric in- and out-patient departments as well as in mutual-help group offices, supported employment services, sheltered employment and housing sites for people with mental illness in the Zürich region. Interested individuals could contact study staff by telephone or email. In an initial telephone screening, inclusion and exclusion criteria were checked and any questions answered. Interested and eligible individuals were then invited to attend a baseline assessment. Assessments and COP groups took place in the offices of an out-patient clinic of Psychiatric University Hospital Zürich, in the city centre and separate from the main hospital building.

Sample size

Since previous reviews of anti-stigma interventions found small- to medium-effect sizes10,24 and in the absence of any prior data on COP’s efficacy, we expected a medium-effect size (equalling d = 0.5 or partial η2 = 0.1, with α = 0.05 and β = 0.80). On this basis and aiming for a feasible sample size, we planned with 60 per group regarding the pre-post change of our primary outcome, self-stigma. During the course of the study, we encountered two difficulties with reaching the planned number of participants. First, several peers were trained to facilitate COP groups, but dropped out before or after administering their first group because they were too busy or unwell, resulting in two peers alone (S.V. and J.C.) facilitating all but one group. Second, recruitment was slower than expected. We therefore decided to end recruitment at n = 100.

Randomisation

Immediately after completing the baseline assessment (T0), participants were randomly assigned to the intervention (COP) or control group. We used a random-number table and, before the study began, one number after the other was put in one opaque envelope each. Envelopes were sequentially numbered from 1 to 120. Once a participant had completed the baseline assessment, a research assistant (E.H., D.H. or I.K.) opened the next consecutively numbered envelope. Research assistants had no knowledge which number was in each envelope. Equal numbers indicated the COP intervention and unequal numbers the control group. Once the envelope was opened, the research assistant informed the participant whether she or he was assigned to the control or COP group.

Intervention

Coming out Proud is a manualised group intervention that consists of three lessons, each delivered in one 2 h session per week over a 3-week period. It is COP’s aim to support people with mental illness in their decision regarding disclosure and secrecy in different settings. It is not the aim to make them disclose their condition, but to assist them in finding the solution that is right for them. The manual and workbook for COP were developed by Corrigan and colleagues based on a previous book21 and are available online (www.stigmaandempowerment.org/resources). The Zürich-based team of the current study translated both texts into German (N.R., E.A., E.H., D.H., I.K., B.K.; and A.I., see acknowledgement). All participants in the COP group received a copy of the workbook. Groups consisted of six to ten participants; all groups but one were facilitated by two peers (S.V. and J.C.). Peers had previous experience either as peer counsellors in psychiatric settings or with facilitating mutual-help groups. Before the start of the study, each pair of facilitating peers were trained with the workbook and ran a practice group to achieve a fidelity score of at least 80% (see below for fidelity measurement). After the practice groups had been run we finalised the translation and layout of the workbook together with the peers (S.V. and J.C.), including the German title of the programme (‘In Würde zu sich stehen’).

Details of the COP intervention can be found in the workbook (see above). In brief, COP’s first lesson is about the pros and cons of disclosing. Participants discuss their idea of identity and mental illness so that they can decide how to frame their identity. They discuss how secrets are a part of everyone’s lives so that they can decide whether their experiences with mental illness should or should not be disclosed. They also weigh costs and benefits of coming out in different settings to facilitate a decision on whether to disclose. The second lesson is about different ways to disclose. In this part, participants discuss levels of (non)disclosure, ranging from social avoidance and complete secrecy to indiscriminant disclosure and broadcasting one’s experience; this includes weighing costs and benefits of each choice in different settings. Participants learn how to assess whether others are beneficial to disclose to and how to respond to the reactions of others. Finally, participants discuss how others might respond to their disclosure and how that will affect them. In the third lesson, participants learn how to tell their story in a personally meaningful way, how to identify peers who might help them with the coming out process, to review how telling their story felt and finally to put together all they learnt. All lessons are accompanied by stories and worksheets in the workbook. Note that in our pilot trial, and different from COP as written for the USA, group facilitators were free whether or not to discuss consumer-operated or peer-led mental health service programmes in lesson three, because these programmes are less known in Switzerland.

Fidelity

We designed a fidelity measure for the COP programme that consisted of 18 items for lesson one, and 10 items each for lesson two and lesson three. Each item corresponded to a section of the workbook, including the explanation of the overall goal of COP and the introduction of group facilitators and participants in the first lesson. Research assistants were present during each COP lesson and checked the number of items/topics covered in each lesson. In all groups, fidelity was high with scores between 17 and 18 items (94 and 100%) for lesson one, and between 9 and 10 (90 and 100%) for lessons two and three.

Outcome measures

All outcomes were assessed at three time points: at baseline (T0); 3 weeks later or after the last COP lesson for participants in the COP group (T1); and at 3-week follow-up, i.e. 6 weeks after baseline (T2). The internal consistency of all self-report scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha values based on the current study, with values >0.90 considered excellent, >0.80 good and >0.70 acceptable. Self-stigma was assessed by the 29-item Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Inventory, with higher mean scores between 1 and 4 indicating more self-stigma.25 Because internal consistency of the five-item stigma resistance subscale was poor (Cronbach’s alphas 0.60, 0.52 and 0.58 for T0, T1 and T2 respectively), we excluded these five items from the total score (alpha of 0.92 for T0, T1 and T2). We also assessed several secondary outcomes. First, we measured empowerment as the conceptual opposite to self-stigma and its consequences,4 using the 28-item Empowerment Scale,26 with a mean score between 1 and 4 and higher scores indicating stronger empowerment (alphas 0.81, 0.83 and 0.82 for T0, T1 and T2). Because COP is about choosing between secrecy and disclosure, we assessed the tendency to keep one’s mental illness a secret in order to avoid discrimination, using Link’s 5-item secrecy scale,7 with higher mean scores between 1 and 6 equalling more secrecy (alphas: 0.74, 0.73 and 0.72). Perceived benefits of disclosure or ‘being out’ are an important motivation to disclose. Among those participants who had decided to disclose to friends and family, we therefore measured perceived benefits of being out by seven items of the Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale (alphas: 0.76, 0.78 and 0.77), with higher means between 1 and 7 reflecting more perceived benefits of disclosure.19

Because stigma in general can be a stressor for people with mental illness with harmful consequences9,27 and both disclosure and secrecy can be understood as behaviours to cope with this stressor,22,28 we measured the cognitive appraisal of stigma as a stressor using a previously validated eight-item measure8,9,29 that is based on Lazarus & Folkman’s30 conceptualisation of stress appraisal processes. Four items assessed the primary appraisal of mental illness stigma as harmful (alphas: 0.90, 0.91 and 0.90) and four items the secondary appraisal of perceived resources to cope with stigma (alphas: 0.77, 0.85 and 0.81). As in previous studies,8,9,29-31 a single stress appraisal score was computed by subtracting perceived resources to cope from perceived harmfulness. This score indicates the cognitive appraisal of stigma as stressful and as exceeding personal coping resources, higher scores equalling more stigma stress. In addition to stigma-related stress in general, we examined disclosure-related distress in particular using the above-mentioned screening item at baseline (T0), post (T1) and follow-up (T2). One item assessed disclosure-related self-efficacy, rated from 1 to 7 with higher scores indicating higher self-efficacy (‘Regarding the secrecy or disclosure of my mental illness, I am confident to handle all questions and issues and to make the right choices’, rated from 1, not at all, to 7, very much). Finally, not as an outcome measure but as a possible confounding variable, depressive symptoms were assessed using the 15-item German version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale32 at baseline (alpha: 0.92), with higher mean scores between 1 and 4 indicating more depressive symptoms.

Statistical methods

Baseline characteristics of the COP and control groups were compared using t-tests for independent samples and chi-squared tests. We examined the effects of COP as compared with the control condition by 2×3 ANOVAs including group (COP v. TAU) as between- and time (T0, T1, T2) as within-subject factor. In case of significant or trend-level (P<0.10) group×time interactions, we ran 2×2 post-hoc ANOVAs for this outcome (two groups, two measurements: T0 and T1; T1 and T2) to determine whether there were significant group×time interactions during the intervention period (T0/T1) and/or during follow-up (T1/T2). Effect size estimates are provided as partial η2 values with η2 = 0.10 indicating a medium-effect size.33 All analyses were run in SPSS, version 20 for Windows. No adjustment was made for multiple tests, and results were considered significant at two-tailed P<0.05.

Results

Feasibility of recruitment, assessment and baseline characteristics

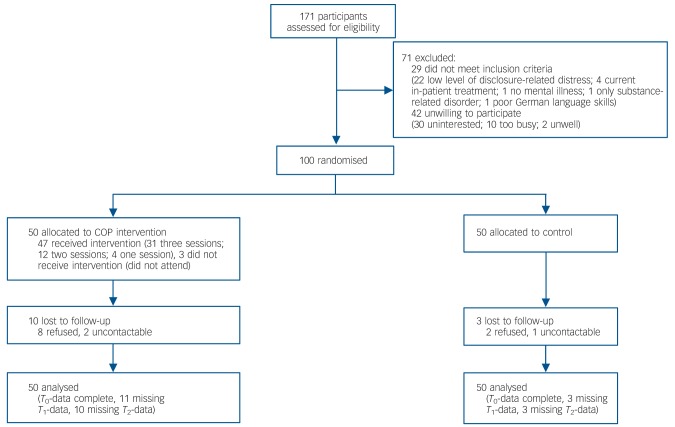

Six part-time research workers recruited 100 participants during half a year. We were contacted by 171 individuals of whom 100 were included and randomised (Fig. 1). We obtained data from all participants at baseline (T0), post (T1) data for 86 (86%) participants and at 3-week follow-up (T2) data for 87 (87%) of all participants; 13 (13%) participants were lost to follow-up. Sociodemographic and clinical variables are reported in Table 1 and did not differ significantly between the COP and the control group. A large majority in both groups received psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological treatment. There were no significant group differences in outcome variables at baseline (means provided in Table 2; results of t-tests for independent samples not shown: all P>0.14). No adverse events occurred during the time of the study.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of participants.

COP, Coming Out Proud; T0, baseline; T1, 3 weeks after baseline; T2, 3-week follow-up, 6 weeks after baseline.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants

| Coming Out Proud group (n = 50) |

Control group (n = 50) |

t-test | χ2 | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic variables | |||||

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 42.9 (12.7) | 41.0 (9.8) | 0.82 | 0.41 | |

| Female, n (%) | 31 (62) | 28 (56) | 0.37 | 0.69 | |

| Ethnicity, White: n (%) | 49 (98) | 49 (98) | 0 | 1 | |

| Education, years: mean (s.d.) | 14.3 (2.7) | 15.1 (3.6) | –1.17 | 0.25 | |

| Living alone, n (%) | 32 (64) | 26 (52) | 1.48 | 0.31 | |

| Married or stable relationship, n (%) | 19 (38) | 17 (34) | 0.17 | 0.84 | |

| Born in Switzerland, n (%) | 42 (84) | 39 (78) | 0.59 | 0.61 | |

| Current disability benefits, n (%) | 26 (52) | 22 (44) | 0.64 | 0.55 | |

| Current competitive employment, n (%) | 11 (22) | 8 (16) | 0.59 | 0.61 | |

| Clinical and diagnostic variables | |||||

| Depressive symptoms, mean (s.d.)a | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.7) | 0.21 | 0.84 | |

| Years since first diagnosis, mean (s.d.) | 14.1 (11.1) | 10.6 (10.6) | 1.62 | 0.11 | |

| Number of previous psychiatric in-patient treatments, mean (s.d.) | 3.4 (3.5) | 2.8 (3.1) | 0.98 | 0.33 | |

| Depressive disorder, n (%) | 28 (56) | 32 (64) | 0.67 | 0.54 | |

| Bipolar disorder, n (%) | 9 (18) | 11 (22) | 0.25 | 0.80 | |

| Schizophrenia spectrum disorder, n (%) | 16 (32) | 11 (22) | 1.27 | 0.37 | |

| Current psychiatric medication, n (%) | 46 (92) | 40 (80) | 2.99 | 0.15 | |

| Current counselling/psychotherapy, n (%) | 42 (84) | 44 (88) | 0.33 | 0.77 | |

| Disclosure | |||||

| Disclosed mental illness to friends and family, yes: n (%)b | 39 (78) | 38 (76) | 0.06 | 0.81 | |

| Disclose mental illness to people at work/school/training:c mean (s.d.) | 2.8 (2.0) | 2.7 (1.5) | –0.29 | 0.77 |

Measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, German version.32

Measured using the Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale.19

Measured with one item: ‘At work, school, university or training, I tell . . . ’, rated from 1 (‘ . . . nobody about my mental illness and keep it as secret as I can’) to 7 (‘ . . . everybody about my mental illness and do not try to keep it a secret at all’); based on 81 participants, because 19 responded ‘not applicable’.

Table 2.

Change of outcome scores for Coming Out Proud (COP) programme and control groups over time, analyses of variance

| Group×time interaction |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) |

T0×T1×T2 (2×3) |

T0×T1 (2×2) |

T1×T2 (2×2) |

|||||||||

| Outcome | Baseline (T0) | Post (T1) | Follow-up (T2) | F(2) | partial η2 | P | F(1) | partial η2 | P | F(1) | partial η2 | P |

| Self-stigmaa | 0.07 | 0.002 | 0.94 | - | - | |||||||

| COP group | 2.14 (0.57) | 2.12 (0.53) | 2.08 (0.57) | |||||||||

| Control group | 2.23 (0.55) | 2.18 (0.53) | 2.16 (0.50) | |||||||||

| Empowermentb | 0.74 | 0.02 | 0.48 | - | - | |||||||

| COP group | 2.84 (0.31) | 2.91 (0.30) | 2.90 (0.32) | |||||||||

| Control group | 2.79 (0.35) | 2.83 (0.35) | 2.87 (0.33) | |||||||||

| Stigma stressc | 7.06 | 0.15 | 0.001 | 9.44 | 0.10 | 0.003 | 10.76 | 0.12 | 0.002 | |||

| COP group | –0.44 (2.28) | –1.34 (2.28) | –0.91 (2.37) | |||||||||

| Control group | –0.76 (2.03) | –0.23 (1.85) | –0.98 (2.09) | |||||||||

| Disclosure-related distressd | 2.44 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 4.84 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.51 | 0.01 | 0.48 | |||

| COP group | 5.10 (1.64) | 4.47 (1.61) | 4.31 (1.73) | |||||||||

| Control group | 4.85 (1.63) | 4.98 (1.69) | 4.57 (1.68) | |||||||||

| Disclosure-related self-efficacye | 0.11 | 0.001 | 0.89 | - | - | |||||||

| COP group | 4.68 (1.53) | 4.61 (1.41) | 4.66 (1.48) | |||||||||

| Control group | 4.06 (1.67) | 4.15 (1.72) | 4.21 (1.71) | |||||||||

| Secrecyf | 2.51 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 4.78 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.002 | 0.68 | |||

| COP group | 4.62 (1.01) | 4.41 (0.88) | 4.32 (0.84) | |||||||||

| Control group | 4.44 (0.90) | 4.53 (0.99) | 4.37 (0.98) | |||||||||

| Perceived benefits of disclosureg | 4.70 | 0.15 | 0.01 | 2.91 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 1.25 | 0.02 | 0.27 | |||

| COP group | 4.15 (1.29) | 4.71 (1.04) | 4.94 (0.95) | |||||||||

| Control group | 4.42 (1.16) | 4.53 (1.19) | 4.36 (1.28) | |||||||||

T0, baseline; T1, 3 weeks after baseline; T2, 3-week follow-up, 6 weeks after baseline.

Measured using the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness Inventory.25

Measured using the Empowerment Scale.26

Measured with one item: ‘In general, how distressed or worried are you with respect to secrecy or disclosure of your mental illness to others?’, rated from 1, not at all, to 7, very much.

Measured with one item: ‘Regarding the secrecy or disclosure of my mental illness, I am confident to handle all questions and issues and to make the right choices’, rated from 1, not at all, to 7, very much.

Measured using the Stigma Coping Orientation Scale.7

Measured using the Coming Out with Mental Illness Scale.19

Effect of COP on primary and secondary outcomes

Using analysis of variance to test for group×time interactions, we did not detect an intervention effect on self-stigma as our primary outcome (Table 2). In terms of secondary outcomes, there was no significant effect of COP on empowerment or on disclosure-related self-efficacy. However, COP led to a significant pre-post (T0/T1) decrease of stigma stress and secrecy as compared with the control group, with a medium-effect size for stigma stress reduction. This effect was only partly sustained during the 3-week follow-up period. Disclosure-related distress decreased significantly in the COP group between baseline and post-measurement and decreased further during the follow-up period. The intervention increased the perceived benefits of being out, an effect that remained stable over the follow-up period.

Comparison of those who completed with those who dropped out of the COP group

Ten participants were lost to follow-up in the COP group (Fig. 1). We compared these 10 with the 40 participants in that group who completed the programme regarding baseline variables, both in terms of sociodemographic and clinical variables (as listed in Table 1) and of baseline scores of outcome variables (as detailed in Table 2). We found no significant subgroup differences except that the 10 participants who discontinued the study were younger (mean 34.2 years, s.d. = 11.9) and reported lower disclosure-related self-efficacy at baseline (mean 2.8 years, s.d. = 1.4) than the 40 who completed the programme (age: mean 45.1 years, s.d. = 12.1, t = –2.55, P = 0.01; self-efficacy: mean 4.6 years, s.d. = 1.6, t = –3.26, P = 0.002).

Participants’ views on COP

Although we did not systematically collect qualitative data, peers (S.V. and J.C.) and research assistants (E.H., D.H. and I.K.) received ample feedback from participants on the COP programme, which we summarise here. Participants saw a number of strengths and weaknesses. They particularly liked the group setting and thus the opportunity to exchange thoughts about secrecy and disclosure with other individuals with similar experiences; this exchange helped many participants realise that they were not alone in their struggle with stigma and disclosure. Participants thought it was crucial that groups were facilitated by peers (rather than by mental health professionals) because peers have first-hand experience with coming out. Participants felt that COP’s content was clear and relevant for their daily lives and disclosure-related decisions. Many participants thought the most helpful part was weighing the pros and cons of disclosure v. secrecy in different settings, because it helped to move beyond global statements (for example seeing disclosure as ‘good’ or ‘bad’) towards differentiating and finding one’s personal view on whether or not to disclose in a particular situation at a particular time. In general, many felt that COP gave them the opportunity to thoroughly think about and discuss topics that mattered to them but that they had found little time to reflect about before, especially because unlike in clinical settings COP’s focus was not on symptoms or deficits but rather on how to handle disclosure and secrecy in everyday settings. Finally, many participants told us that they were able to apply COP’s lessons to situations in their daily lives during the intervention.

People also noted a number of weaknesses and difficulties. First of all, some participants in the intervention group felt the demand on their time because of the group sessions and assessments was too high. Others felt that the workbook of 65 pages, which was handed out to them at the start in one piece, was too long (it may help in the future to hand out a third of the workbook at the start of each lesson). Some participants thought the three lessons included too much material for the limited time available and would have preferred a slightly longer intervention or a briefer workbook. Some found the initial discussion of mental illness identity difficult, and wondered whether self-labelling as having a particular mental illness was necessary and how it could be reconciled with current approaches to recovery. The cognitive approach to correcting self-stigma during the first lesson (when participants are asked to reconsider negative self-statements in order to reduce self-stigma) was sometimes felt to be too brief. Few participants mentioned that they had actually done homework assignments listed in the workbook (for example practising disclosure between sessions). Finally, some participants felt that the preparation, during the third session, for speaking out in public about one’s mental illness was a step too soon, at least by European standards compared with the USA.

Discussion

Feasibility

Our study suggests it is feasible to recruit and retain adults with mental illness to an RCT of the COP programme. We recruited 83% (100 of 120) of our target sample and retained nearly 90% (87 of 100) throughout the trial. More participants dropped out in the COP group, possibly because with evening sessions plus assessments it made higher demands on the time of participants compared with the control group. Retaining a sufficient number of trained peers as group facilitators was a challenge.

COP’s efficacy

The intervention did not have a significant effect on our primary outcome, with self-stigma slightly decreasing over time in both groups. We found a corresponding pattern for empowerment, a secondary outcome and the conceptual opposite of self-stigma and its consequences, which slightly increased in both groups between baseline and follow-up. On the other hand, between baseline and post-intervention 3 weeks later COP had significant positive effects on the cognitive appraisal of stigma as a stressor, on disclosure-related distress, perceived benefits of disclosure and on secrecy.

To make sense of this pattern of preliminary findings, we can distinguish three types of outcomes: self-stigma/empowerment; stress-related variables; and secrecy/disclosure as process variables. First, self-stigma and empowerment are broad and likely more stable outcomes. As a three-session intervention, COP may have a too small therapeutic dose to achieve fast changes in these domains. Indirect support for this assertion can be drawn from the fact that interventions with some empirical support to reduce self-stigma consist of a larger number of sessions.11,13,15

Second and with respect to stress-related variables, COP had significant positive effects on the cognitive appraisal of stigma as a stressor; after 3 weeks, participants in the intervention group were more likely to feel they had the necessary coping resources to handle stigma-related threats. This is a preliminary but encouraging finding, because stigma stress is a key reaction of stigmatised individuals facing the threat of discrimination and is associated with a wide range of negative long-term outcomes.9,27 Decreased stigma stress, if sustained over time, along with reduced disclosure-related distress is therefore likely to translate to reduced self-stigma9,31 and other positive outcomes. Future research should investigate whether booster sessions or a slightly longer COP intervention may lead to more sustained reductions of stigma stress. It is consistent with this finding that more specific disclosure-related distress decreased in the COP group during the intervention period and decreased further during the follow-up period.

Third, the process of either keeping one’s mental illness a secret v. disclosure or coming out was a focus of the COP intervention. Relative to the control group, among COP participants the tendency to keep their condition secret decreased, paralleled by increased perceived benefits of disclosure with both trends continuing in the follow-up period. Although COP does not aim to make people disclose, these findings point to beneficial effects of COP because secrecy is a sometimes protective, but often harmful, long-term coping mechanism.7,18 This is consistent with results of a recent RCT that evaluated a brief decision aid on disclosure in workplace settings and found positive effects on decisional conflict.34

It should be investigated in future studies whether COP is more effective when delivered to individuals with a long-standing v. a recent-onset mental illness. Undertaking the programme in the early stages of one’s mental illness may have the advantage of fostering adaptive coping styles early on and reducing later vicious circles of anticipated discrimination, secrecy and social withdrawal. On the other hand, individuals following a first episode may not consider themselves ‘mentally ill’ and might understandably think that coming out with a mental illness is not a reasonable option for them. For people with a long history of mental illness the COP programme may work well because participants are likely to have many experiences with (self-) labelling, stigma, disclosure and secrecy that they can exchange in the group sessions. Their identification with the group of people with mental illness is likely to be stronger and therefore coming out as someone with a mental illness may be more intuitive. On the other hand, stigma’s negative impact and potential consequences such as ‘why try’6 and demoralisation may be more entrenched and thus harder to change.

Future studies of COP should examine diagnosis as a potential moderator of intervention effects. Possibly people with less stigmatised disorders such as anxiety or depression are less distressed by secrecy and disclosure and respond more promptly than individuals with psychosis or bipolar disorder. Future trials should also investigate which factors increase the risk of drop-out during the intervention. If our very preliminary findings are replicated, we should make efforts to retain especially those participants with lower disclosure-related self-efficacy. Finally, given our recruitment strategy we cannot rule out the possibility that preferentially those individuals decided to participate who were already motivated to discuss their decisions regarding secrecy and disclosure. The high number of participants who had disclosed to friends and family at baseline supports this view; on the other hand, in employment settings the reluctance to disclose was much greater.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has a number of limitations that need to be considered. First, with 100 participants our study was slightly underpowered to detect medium effects; this means that our negative findings regarding COP’s effects on self-stigma and empowerment are not robust. Second, although the vast majority in both groups received psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological treatment, there was some heterogeneity in the TAU that participants received. Third, our findings are based on a largely White, middle-aged, urban Swiss sample and cannot be generalised to other settings. Fourth, and evident from data in Table 1, approximately three out of four participants in our study had decided to disclose their mental illness to friends and family at baseline. Although the rate was lower for disclosure in employment settings, future trials will show whether COP has greater efficacy in samples with lower baseline disclosure rates. Fifth, our follow-up period was brief and therefore COP’s long-term effects remain unclear. It could be speculated, for example, that some of COP’s potential benefits need a number of positive experiences with coming out and thus more time to materialise.

Our trial also had a number of strengths. As there were few exclusion criteria, we recruited a sample of people with mental illness with high external validity. The rates of participants retained in the trial were high and both groups were comparable across a wide range of sociodemographic and clinical variables. Although our trial was not masked, this did not affect findings because all measures were based on self-report. Fidelity scores were very high throughout the study. Finally, this is the first RCT of COP, providing initial evidence that will be complemented by findings of trials that are currently under way in the USA.

Clinical implications

Many individuals with mental illness experience self-stigma, stigma-related stress and the dilemma of choosing between disclosure and secrecy. Previously there were not any specific interventions to address this concern. Our study provides initial evidence that COP can support individuals with mental illness in this domain. If corroborated by future findings, COP as a brief intervention could be used in clinical as well as mutual support settings by and for people with mental illness.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants in this study and also Alexandra Isaksson for her help with translating the manual into German.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

P.W.C. developed the Coming Out Proud programme.

Funding

This study was supported by Sanatorium Kilchberg, the Psychiatric University Hospital Zürich, the Zürich Impulse Program for the Sustainable Development of Mental Health Services (zinep.ch) as well as the National Institute of Mental Health, USA.

References

- 1. Lasalvia A, Zoppei S, van Bortel T, Bonetto C, Cristofalo D, Wahlbeck K, et al. Global pattern of experienced and anticipated discrimination reported by people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional survey. Lancet 2013; 381: 55–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Henderson C, Thornicroft G. Evaluation of the Time to Change programme in England 2008-2011. Br J Psychiatry 2013; 202 (suppl 55): s45–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schomerus G, Schwahn C, Holzinger A, Corrigan PW, Grabe HJ, Carta MG, et al. Evolution of public attitudes about mental illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2012; 125: 440–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brohan E, Elgie R, Sartorius N, Thornicroft G. Self-stigma, empowerment and perceived discrimination among people with schizophrenia in 14 European countries: the GAMIAN-Europe study. Schizophr Res 2010; 122: 232–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rüsch N, Lieb K, Bohus M, Corrigan PW. Self-stigma, empowerment, and perceived legitimacy of discrimination among women with mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2006; 57: 399–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Rüsch N. Self-stigma and the “why try” effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. World Psychiatry 2009; 8: 75–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Link BG, Mirotznik J, Cullen FT. The effectiveness of stigma coping orientations: can negative consequences of mental illness labeling be avoided? J Health Soc Behav 1991; 32: 302–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Wassel A, Michaels P, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, et al. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: I. Predictors of cognitive stress appraisal. Schizophr Res 2009; 110: 59–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Powell K, Rajah A, Olschewski M, Wilkniss S, et al. A stress-coping model of mental illness stigma: II. Emotional stress responses, coping behavior and outcome. Schizophr Res 2009; 110: 65–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mittal D, Sullivan G, Chekuri L, Allee E, Corrigan PW. Empirical studies of self-stigma reduction strategies: a critical review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv 2012; 63: 974–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yanos PT, Roe D, Lysaker PH. Narrative enhancement and cognitive therapy: a new group-based treatment for internalized stigma among persons with severe mental illness. Int J Group Psychother 2011; 61: 576–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Knight MTD, Wykes T, Hayward P. Group treatment of perceived stigma and self-esteem in schizophrenia: a waiting list trial of efficacy. Behav Cogn Psychother 2006; 34: 305–18 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lucksted A, Drapalski A, Calmes C, Forbes C, DeForge B, Boyd J. Ending self-stigma: pilot evaluation of a new intervention to reduce internalized stigma among people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Rehab J 2011; 35: 51–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Fletcher L. Slow and steady wins the race: a randomized clinical trial of acceptance and commitment therapy targeting shame in substance use disorders. J Consult Clin Psychol 2012; 80: 43–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sibitz I, Provaznikova K, Lipp M, Lakeman R, Amering M. The impact of recovery-oriented day clinic treatment on internalized stigma: preliminary report. Psychiatry Res 2013; 209: 326–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Morrison AP, Birchwood M, Pyle M, Flach C, Stewart SLK, Byrne R, et al. Impact of cognitive therapy on internalised stigma in people with at-risk mental states. Br J Psychiatry 2013; 203: 140–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chaudoir SR, Fisher JD. The disclosure processes model: understanding disclosure decision making and postdisclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychol Bull 2010; 136: 236–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pachankis JE. The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: a cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychol Bull 2007; 133: 328–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Corrigan PW, Morris S, Larson JE, Rafacz J, Wassel A, Michaels P, et al. Self-stigma and coming out about one’s mental illness. J Commun Psychol 2010; 38: 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Quinn DM, Earnshaw VA. Concealable stigmatized identities and psychological well-being. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2013; 7: 40–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Corrigan PW, Lundin R. Don’t Call Me Nuts! Coping with the Stigma of Mental Illness. Recovery Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Corrigan PW, Kosyluk KA, Rüsch N. Reducing self-stigma by coming out proud. Am J Public Health 2013; 103: 794–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th edn) (DSM-IV). APA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Corrigan PW, Morris SB, Michaels PJ, Rafacz JE, Rüsch N. Challenging the public stigma of mental illness: a meta-analysis of outcome studies. Psychiatr Serv 2012; 63: 963–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatr Res 2003; 121: 31–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, Crean T. A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv 1997; 48: 1042–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annu Rev Psychol 2005; 56: 393–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hult JR, Wrubel J, Branstrom R, Acree M, Moskowitz JT. Disclosure and nondisclosure among people newly diagnosed with HIV: an analysis from a stress and coping perspective. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012; 26: 181–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kaiser CR, Major B, McCoy SK. Expectations about the future and the emotional consequences of perceiving prejudice. Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2004; 30: 173–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rüsch N, Müller M, Lay B, Corrigan PW, Zahn R, Schönenberger T, et al. Emotional reactions to involuntary psychiatric hospitalization and stigma as a stressor among people with mental illness. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014; doi: 10.1007/s00406-013-0412-5 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32. Hautzinger M, Bailer M. Allgemeine Depressionsskala [Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale, German version]. Beltz, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vacha-Haase T, Thompson B. How to estimate and interpret various effect sizes. J Couns Psychol 2004; 51: 473–81 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Henderson C, Brohan E, Clement S, Williams P, Lassman F, Schauman O, et al. Decision aid on disclosure of mental health status to an employer: feasibility and outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 2013; 203: 350–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]