Abstract

Bacillus megaterium can produce poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) as carbon and energy storage materials. We now report that the phaQ gene, which is located upstream of the phasin-encoding phaP gene, codes for a new class of transcriptional regulator that negatively controls expression of both phaQ and phaP. A PhaQ binding site that plays a role in this control has been identified by gel mobility shift assays and DNase I footprinting analysis. We have also provided evidence that PhaQ could sense the presence of PHB in vivo and that artificial PHB granules could inhibit the formation of PhaQ-DNA complex in vitro by binding to PhaQ directly. These suggest that PhaQ is a PHB-responsive repressor.

Poly-β-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) and other polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHAs) are biodegradable polyesters that are produced by a wide variety of bacteria as intracellular carbon and energy storage materials (1, 13, 31). PHB synthases (PhaC) and phasins (PhaP) are proteins that play important roles in PHB production and granule formation. Phasin, an abundant granule-associated protein, forms a boundary layer on the PHB surface to sequester hydrophobic PHB from the cytoplasm. Thus, phasin can inhibit individual granules from coalescing and promotes PHB synthesis by regulating the ratio of surface area to volume of PHB granules (27-29). PhaP may also have a protective function to reduce the passive attachment of cytoplasmic proteins to PHB surface (16, 27). It is generally thought that the synthesis of phasin proteins is highly regulated (8). In Ralstonia eutropha, expression of the phaP gene is negatively controlled by the autoregulated repressor PhaR (21, 30). The accumulation of PhaP in the R. eutropha cells is strictly dependent on PHB production (28). After the onset of PHB biosynthesis, PhaR can sense the presence of PHB and bind to nascent PHB granules, leading to derepression of phaP. In Paracoccus denitrificans the phaR gene, which is located immediately downstream of phaP, encodes a repressor that regulates phaP expression. PhaR can sense the presence of PHA and interact with PHA granules (14, 15).

Although Bacillus megaterium is already known to be able to synthesize PHB and accumulate PHB granules, genes that are involved in PHB synthesis and encode PHB granule-associated proteins were not cloned until recently (17). Among a cluster of five pha genes of B. megaterium, phaP and phaQ are transcribed in one direction, whereas phaR, phaB, and phaC are divergently transcribed as a tricistronic operon. phaP codes for a phasin protein. phaB and phaC encode NADPH-dependent acetoacetyl coenzyme A reductase and a novel PHB synthase, respectively (17). This novel PHB synthase requires both PhaC and PhaR for activity (18). It should be noted that the designation of the B. megaterium phaR gene does not follow the conventional rule. Rather than encoding a transcriptional regulator like the PhaR protein of R. eutropha or P. denitrificans, the B. megaterium phaR gene probably encodes a subunit of a heterodimeric PHB synthase (18, 25). Nevertheless, the protein that can sense the presence of PHB has not been identified, and how the phasin-encoding phaP gene is regulated remains unknown. Here we report that phaQ encodes a new class of transcriptional regulator that can interact directly with PHB and regulate phaP expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and B. megaterium cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium (24). Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter): ampicillin, 100; chloramphenicol, 2 (for selection of B. megaterium integrants of pSG1151 derivatives) or 7 (for selection of B. megaterium transformants of pLC4); tetracycline, 10.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Descriptiona | Reference or sourceb |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ(lac-proAB) F′[traD36 proAB+lacIqlacZΔ M15] | Takara |

| B. megaterium | ||

| ATCC 11561 | Wild-type strain | ATCC |

| BM647 | ATCC 11561 derivative; phaR::pGS1042 | This study |

| BM679 | ATCC 11561 derivative; phaP::pGS1071 | This study |

| BM695 | ATCC 11561 derivative; phaC::pGS1111 | This study |

| Plasmid | ||

| pLC4 | Promoter probe vector with xylE as the reporter gene; Apr Cmr | 22 |

| pQE30 | Expression vector for producing His-tagged proteins; Apr | Qiagen |

| pMAL-c2 | Expression vector for producing fusions of maltose-binding protein; Apr | New England Biolabs |

| pSG1151 | GFP tagging vector; Apr Cmr | 11 |

| pHY300PLK | Shuttle vector; Apr Tcr | Takara |

| pGS253 | pQE30 carrying the bm3P1 gene | This study |

| pGS482 | pQE30 carrying the bscR gene | 10 |

| pGS1041 | pQE30 carrying the wild-type phaQ gene | This study |

| pGS1041F54S | pQE30 carrying the mutated phaQ gene (F54S substitution) | This study |

| pGS1042 | pSG1151 derivative; PhaR-GFP in-frame fusion plasmid; phaR (aa 104 to 199)::gfp | This study |

| pGS1056 | pHY300PLK with an insert containing the Shine-Dalgano sequence plus the phaQ gene | This study |

| pGS1060 | pLC4 carrying the phaQ promoter region | This study |

| pGS1071 | pSG1151 derivative; PhaP-GFP in-frame fusion plasmid; phaP (aa 1 to 100)::gfp | This study |

| pGS1108 | pLC4 carrying the phaQ-phaP intergenic region | This study |

| pGS1111 | pSG1151 derivative; phaC disruptive plasmid; PhaC-GFP in-frame fusion plasmid; phaC (aa 59 to 157)::gfp | This study |

| pGS1120 | pLC4 carrying the phaQ coding region | This study |

| pGS1132 | pLC4 carrying the phaQ coding region and the phaQ-phaP intergenic region | This study |

| pGS1142 | pLC4 carrying the promoter region and the coding region of phaQ | This study |

| pGS1143 | pLC4 carrying the promoter region and the mutated coding region of phaQ | This study |

| pGS1144 | pMAL-c2 carrying the phaQ gene | This study |

| pGS1151 | pLC4 carrying the mutated regulatory region and the wild-type coding region of phaQ | This study |

Apr, ampicillin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenicol resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant. aa, amino acids.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

Construction of plasmids.

Green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagging vector pSG1151 (11) was used for the construction of various integrative plasmids. To construct the integrative plasmid pGS1042, a 288-bp DNA fragment carrying codons 104 through 199 of phaR and flanked by HindIII and EcoRI sites was amplified by PCR and cloned between the HindIII and EcoRI sites of plasmid pSG1151, resulting in the phaR104-199::gfp in-frame fusion. To construct the integrative plasmid pGS1071, a 336-bp DNA fragment carrying the Shine-Dalgano sequence plus codons 1 through 100 of phaP and flanked by HindIII and EcoRI sites was generated by PCR and cloned between the HindIII and EcoRI sites of plasmid pSG1151, resulting in the phaP1-100::gfp in-frame fusion. To construct the integrative plasmid pGS1111, a 297-bp DNA fragment carrying codons 59 through 157 of phaC and flanked by HindIII and EcoRI sites was amplified by PCR and was cloned between the HindIII and EcoRI sites of plasmid pSG1151, resulting in the phaC59-157::gfp in-frame fusion.

Various DNA fragments in plasmids pGS1060, pGS1108, pGS1120, pGS1132, and pGS1142 as shown in Fig. 1A were amplified by PCR and cloned individually between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pLC4 (22). The DNA fragment in plasmid pGS1143, which contains a single-base substitution in the phaQ gene (T to C at nucleotide position +161 relative to the phaQ translational start site), and the DNA fragment in plasmid pGS1151, which carries a two-base substitution within the 19-bp inverted repeat (AC to GT at positions −6 and −5), were generated by a two-step PCR method (6) followed by cloning the resulting DNA fragments individually between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pLC4. The mutated sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

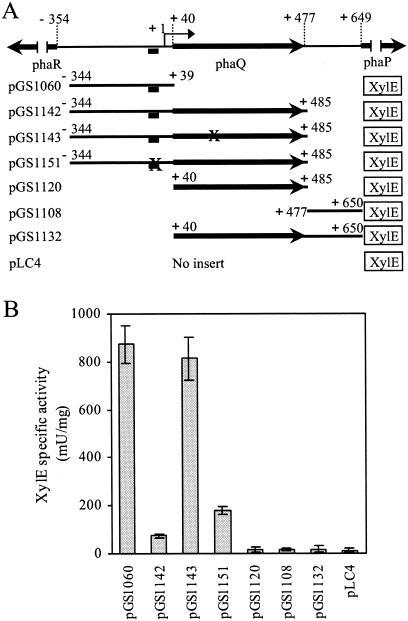

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the plasmid constructs and their XylE-specific activities in B. megaterium. (A) The number above each line denotes base position relative to the transcriptional initiation site of phaQ (17). The solid bar below the phaQ promoter region represents a 19-bp imperfect inverted repeat (positions −18 to +1). A two-base substitution within the 19-bp inverted repeat (AC to GT at positions −6 and −5) or a single-base change in the phaQ coding region (T to C, leading to an F54S replacement in PhaQ) is represented by a cross. Each pLC4-derived plasmid contains an xylE reporter gene. (B) XylE-specific activities of B. megaterium cells carrying the above plasmids and grown in LB medium. Each value represents the mean of at least four determinations. Each error bar indicates the standard error of the mean.

To construct a plasmid that overproduces PhaQ in B. megaterium, a 490-bp DNA fragment carrying the Shine-Dalgano sequence plus the phaQ gene and flanked by EcoRI and HindIII sites was amplified by PCR and cloned between the EcoRI and HindIII sites of pHY300PLK (Takara Shuzo Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) to generate plasmid pGS1056. The promoter of the tetracycline resistance gene present in pHY300PLK can thus drive the expression of phaQ in B. megaterium.

To construct plasmid pGS253, a 380-bp DNA fragment carrying the coding sequence of bm3P1 (12) and flanked by BamHI and HindIII sites was amplified by PCR and was cloned between the BamHI and HindIII sites of pQE30 (Qiagen Inc.). To construct plasmid pGS1041, a 443-bp DNA fragment carrying the coding sequence of phaQ and flanked by BamHI and HindIII sites was amplified by PCR and cloned between the BamHI and HindIII sites of pQE30. The sequence of phaQ was verified by DNA sequencing. Plasmid pGS1041F54S, which contains a single-base mutation (T to C at nucleotide position +161 relative to the phaQ translational start site) in the phaQ gene, was serendipitously obtained during the course of construction of a pQE30-based phaQ-overexpressing plasmid. To construct plasmid pGS1144, the above-mentioned 443-bp DNA fragment carrying the coding sequence of phaQ and flanked by BamHI and HindIII sites was cloned between the BamHI and HindIII sites of pMAL-c2 (New England Biolabs, Inc.) to generate a maltose-binding protein (MalE)-PhaQ fusion protein.

Construction of B. megaterium mutant strains with protein-GFP fusions.

Plasmid pSG1151-based integrative plasmids pGS1042, pGS1071, and pGS1111 were individually introduced into B. megaterium cells. Integration was achieved by a Campbell-like single-crossover recombination. Resistance to chloramphenicol was used to select the mutant strains. The correctness of each integrant was verified by PCR and Southern blot analysis.

Overproduction and purification of His-tagged Bm3P1, BscR, PhaQ, and PhaQ(F54S) proteins.

E. coli JM109 cells bearing plasmid pGS253, pGS482, pGS1041, or pGS1041F54S were grown in LB medium. After the absorbance at 600 nm reached 0.5, IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added at a final concentration of 0.3 mM, and incubation was continued for 2 h. After harvesting cells by centrifugation and disrupting resuspended cells by sonication on ice, the disrupted cells were subjected to centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 10 min. Purification of His-tagged proteins from the supernatants by Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid affinity column was performed according to the instructions of the matrix manufacturer (Qiagen Inc.).

Overproduction and purification of the MalE-PhaQ fusion protein.

Cell growth, induction by IPTG, cell disruption, and centrifugation were performed with the same procedure as that described above. Purification of the MalE-PhaQ fusion protein by amylose column was carried out according to the instructions of the matrix manufacturer (New England Biolabs, Inc.). After elution the MalE-PhaQ fusion protein was concentrated by using the Centricon-10 concentrator (Amicon, Inc.). In order to cleave the MalE from PhaQ, 100 μg of MalE-PhaQ was incubated with 1 μg of factor Xa protease (New England Biolabs, Inc.) at 4°C for 2 days. The progress of cleavage was checked by sodium dodecyl sulfate-13 polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-13% PAGE). The released PhaQ protein was used without further purification.

DNase I footprinting analysis.

About 4 ng of 32P-end-labeled DNA fragment containing the phaQ promoter region was incubated with the PhaQ protein (1.5 to 12 ng). DNase I footprinting assays were performed exactly as described previously (3).

Preparation of artificial PHB granules.

Native PHB granules were isolated from B. megaterium cells as described previously (19). Approximately 2 mg of isolated native PHB granules were then incubated with 50 μg of trypsin at 37°C in 500 μl of a reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4) for 1 h. Trypsin was then inactivated by treatment with 4 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and by heating to 70°C for 10 min. After centrifugation the pellets were exhaustively washed with 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), resuspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl and 1 mM EDTA), and stored at 4°C.

Rebinding of PhaQ to artificial PHB granules in vitro.

Purified His-tagged PhaQ (100 ng) or His-tagged Bm3P1 (120 ng) was incubated with artificial PHB granules (100 μg) in a final volume of 25 μl of reaction mixture containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4). After incubation for 30 min the reaction mixtures were separated into pellets and supernatants by centrifugation. The PHB granules present in pellets were washed twice with 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer and were resuspended in the denaturing sample buffer. Proteins were analyzed in an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel and were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue.

Other methods.

Transformation of B. megaterium cells was achieved by the protoplast method (2). An established method was used for spectrophotometric measurement of XylE (catechol 2,3-dioxygenase) activity (22). The procedure of Laemmli (9) was used for SDS-PAGE. Western blotting was performed as described previously (26). Gel mobility shift assays were carried out according to the method of Fried and Crothers (5). Protein concentrations were determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay method according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Pierce Biotechnology, Inc.) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Analysis of the regulatory role of PhaQ.

The phaQ gene of B. megaterium is located immediately upstream of the phasin-encoding phaP gene (17). PhaQ of B. megaterium does not exhibit significant amino acid similarity to PhaR of R. eutropha or P. denitrificans or to other proteins in the data banks with known function. To determine whether PhaQ plays a regulatory role, a series of plasmid pLC4 (22)-derived constructs were made with promoterless xylE as a reporter gene (Fig. 1A) and were introduced into B. megaterium cells. As shown in Fig. 1B, the presence of phaQ in plasmid pGS1142 led to a much lower XylE-specific activity than deletion of phaQ in plasmid pGS1060, raising the possibility that phaQ might encode a negative regulator.

During the course of construction of a PhaQ-overproducing plasmid in E. coli (see below), a mutant form of phaQ that contains a single-base mutation (T to C at nucleotide position +161 relative to the phaQ translational start site) was serendipitously generated by PCR amplification of the phaQ gene. This led to an F54S replacement in PhaQ. While carrying out gel mobility shift assays (see below) we found that the wild-type PhaQ had specific DNA-binding ability in vitro. However, when PhaQ carried an F54S mutation its DNA-binding ability was abolished. To test if this would occur in vivo, a single-base substitution (T to C at nucleotide position +161 relative to the phaQ translational start site) was introduced into the coding region of phaQ (leading to an F54S replacement) to generate plasmid pGS1143 (Fig. 1A). B. megaterium cells carrying plasmid pGS1143 showed sixfold higher XylE-specific activity than those carrying plasmid pGS1142 (Fig. 1B). These results suggested that phaQ might encode a regulatory protein that negatively autoregulates its own expression.

To further confirm the phaQ autoregulation, a binary-vector system in B. megaterium cells was used to examine the effect of PhaQ produced from the low-copy plasmid pGS1056 on expression of the phaQ promoter region-xylE transcriptional fusion from the high-copy plasmid pGS1060 (Fig. 1A). The XylE-specific activity obtained from B. megaterium cells carrying compatible plasmids pGS1056 and pGS1060 was 88 ± 8 mU/mg of protein, whereas the XylE-specific activity in B. megaterium cells carrying compatible plasmid pGS1060 and the low-copy control vector pHY300PLK was 236 ± 19 mU/mg of protein. This result is in agreement with the notion that phaQ expression is subject to negative autoregulation.

phaQ and phaP constitute a bicistronic operon.

phaQ and phaP are transcribed in an orientation opposite to that of the phaRBC operon (17) (Fig. 1A). Sequence analysis revealed no typical ρ-independent transcription terminator within the 168-bp phaQ-phaP intergenic region. Northern blot analysis was used to examine whether phaQ and phaP genes could be cotranscribed. It was found that both a phaQ-specific probe and a phaP-specific probe could hybridize to a 1.2-kb transcript that is sufficient to span the phaQ and phaP genes (data not shown), suggesting that these two genes can be cotranscribed. Reverse transcriptase PCR also confirmed the operonic organization of these two genes (data not shown). The phaP-specific probe, but not the phaQ-specific probe, also hybridized to a 0.7-kb transcript whose length is sufficient to span the phaP gene. To investigate whether a promoter is present in the phaQ-phaP intergenic region, we constructed plasmid pGS1108 (Fig. 1A). The XylE-specific activity obtained from B. megaterium cells carrying plasmid pGS1108 suggested that no promoter exists within the phaQ-phaP intergenic region (Fig. 1B). To exclude the possibility that a promoter might be present in the phaQ coding region or span the boundary between the phaQ coding region and the phaQ-phaP intergenic region, we also constructed plasmids pGS1120 and pGS1132 (Fig. 1A). It was found that no promoter activity could be detected within these regions (Fig. 1B). Taken together, these results suggest that the 0.7-kb transcript is most likely to be a processing product derived from the 1.2-kb transcript.

It is generally thought that the phaP-encoded phasin is an abundant protein in PHA-producing bacteria, whereas the level of a transcriptional regulator like PhaQ is supposed to be low in bacteria. Should phaQP be derepressed, a posttranscriptional processing event occurring in the phaQP cotranscript could selectively degrade the phaQ transcript and leave the phaP transcript intact, thus allowing differential syntheses of these two proteins. It is tempting to speculate that the long phaQ-phaP intergenic region might provide a signal for the processing event to occur.

Negative regulation of phaP expression by PhaQ.

To test the effect of PhaQ on phaP expression, we constructed the B. megaterium strain BM679 in which the N-terminal 100 amino acids of PhaP were translationally fused to a green fluorescent protein (GFP) encoded by the integrative plasmid pSG1151 (11). Whole-cell extracts prepared from B. megaterium strain BM679 carrying the above-mentioned PhaQ-overproducing plasmid pGS1056 or control vector pHY300PLK were subjected to SDS-13% PAGE (Fig. 2A, lanes 1 and 2) and Western blotting with anti-GFP antibody as the probe (Fig. 2A, lanes 3 and 4). A protein band corresponding to a translational fusion between the truncated PhaP and GFP could be detected by anti-GFP antibody in B. megaterium strain BM679 bearing the control vector pHY300PLK (Fig. 2A, lane 3). However, the band intensity of the same fusion protein from B. megaterium strain BM679 carrying the PhaQ-overproducing plasmid pGS1056 was much weaker (Fig. 2A, lane 4), indicating that PhaQ can negatively regulate phaP expression.

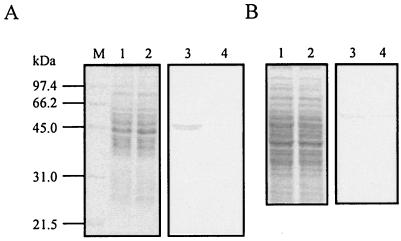

FIG. 2.

Western blot analyses of effects of PhaQ overproduction on expression of phaP and phaR genes. (A) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from B. megaterium strain BM679 (bearing a chromosomal PhaP-GFP fusion) transformed with the PhaQ-overproducing plasmid pGS1056 (lanes 2 and 4) or the control vector pHY300PLK (lanes 1 and 3). Equal amounts of total proteins were separated in SDS-13% polyacrylamide gels. Bands were visualized with Coomassie brilliant blue staining (lanes 1 and 2). Western blotting was performed on a duplicate gel with anti-GFP antibody as the probe (lanes 3 and 4). Lane M, molecular mass markers. (B) Whole-cell extracts were prepared from the B. megaterium strain BM647 (bearing a chromosomal PhaR-GFP fusion) transformed with the PhaQ-overproducing plasmid pGS1056 (lanes 2 and 4) or the control vector pHY300PLK (lanes 1 and 3). Equal amounts of total proteins were separated in SDS-11% polyacrylamide gels. Bands were visualized with Coomassie brilliant blue staining (lanes 1 and 2). Western blotting was performed on a duplicate gel with anti-GFP antibody as the probe (lanes 3 and 4).

To further investigate the possible effect of PhaQ on phaR expression, we constructed the B. megaterium strain BM647 in which PhaR was translationally fused to GFP. Whole-cell extracts prepared from B. megaterium strain BM647 carrying the PhaQ-overproducing plasmid pGS1056 or the control vector pHY300PLK were subjected to SDS-11% PAGE (Fig. 2B, lanes 1 and 2) and Western blotting with anti-GFP antibody as the probe (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4). In contrast to the repressive effect of PhaQ on phaP expression, PhaQ had no apparent effect on phaR expression (Fig. 2B, lanes 3 and 4).

Interaction of PhaQ with the phaQ promoter region in vitro.

Because the above results revealed that PhaQ could autoregulate its own expression in vivo, it was tempting to explore whether PhaQ could bind to the phaQ regulatory region in vitro. To facilitate purification we constructed plasmid pGS1144, which could overproduce a maltose-binding protein (MalE)-PhaQ fusion protein. This MalE-PhaQ fusion protein was purified from the crude extract of E. coli cells carrying pGS1144 by affinity chromatography on an amylose column. The PhaQ protein released from cleavage of purified MalE-PhaQ fusion protein with factor Xa protease was used without further purification.

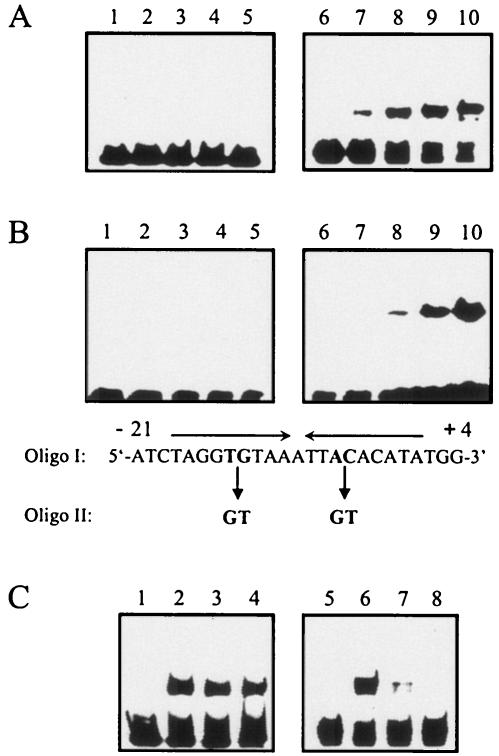

To determine whether PhaQ was able to bind DNA sequence specifically, gel mobility shift assays with two PCR-amplified DNA fragments end-labeled with 32P were performed. One was a 0.15-kb fragment containing the phaQ promoter region (−105 to +39 relative to the transcriptional initiation site of phaQ). The other was a 0.16-kb fragment containing the bscR promoter region (10). The results showed that PhaQ could retard the DNA fragment containing the phaQ promoter region (Fig. 3A, lanes 7 to 10) but not the control DNA fragment at the assay concentrations (Fig. 3A, lanes 2 to 5). No such retardation was detected when purified MalE-β-galactosidase α fusion protein was used at similar concentrations (data not shown). It is noteworthy that, in contrast to the purified wild-type PhaQ protein, purified PhaQ protein containing an F54S replacement did not exhibit DNA-binding ability in gel mobility shifts assays under similar assay conditions (data not shown), suggesting that the native PhaQ protein is indeed a DNA-binding protein.

FIG. 3.

Gel mobility shift assays of the DNA-binding ability of PhaQ and the effects of artificial PHB granules on formation of PhaQ-DNA complex and BscR-DNA complex. (A) A 0.16-kb DNA fragment containing the B. subtilis bscR promoter region (10) (lanes 1 to 5) and a 0.15-kb DNA fragment containing the B. megaterium phaQ promoter region (positions −105 to +39) (lanes 6 to 10) were used as probes. About 2 ng of 32P-labeled DNA probe was used in each reaction mixture (final volume, 20 μl). Lanes 1 and 6, DNA probe alone; lanes 2 to 5 and 7 to 10, DNA probe plus increasing amounts of PhaQ (3, 6, 12, and 24 ng, respectively). Samples were run in an 8% native polyacrylamide gel. (B) Double-stranded oligo I containing an imperfect inverted repeat (positions −18 to +1) in the phaQ promoter region used as the probe in lanes 6 to 10. The sequence of its upper strand is shown at the bottom of the panels. Double-stranded oligo II containing a four-base mutation in the inverted repeat (shown at the bottom of the panels) was used as the probe in lanes 1 to 5. About 0.3 ng of 32P-labeled DNA probe was used in each reaction mixture (final volume, 20 μl). Lanes 1 and 6, DNA probe alone; lanes 2 to 5 and 7 to 10, DNA probe plus increasing amounts of PhaQ (1.5, 3, 6, and 12 ng, respectively). Samples were run in an 8% native polyacrylamide gel. (C) The above-mentioned 0.16-kb DNA fragment containing the bscR promoter region was used as the probe in lanes 1 to 4. The above-mentioned 0.15-kb DNA fragment containing the phaQ promoter region was used as the probe in lanes 5 to 8. Purified His-tagged BscR (12 ng) or PhaQ (8 ng) was incubated with 2 ng of 32P-labeled DNA probe in the absence or presence of artificial PHB granules in a final volume of 20 μl of reaction mixture. Lanes 1 and 5, DNA probe alone; lane 2, DNA probe plus BscR; lanes 3 and 4, DNA probe plus BscR in the presence of 15 and 30 μg of PHB, respectively; lane 6, DNA probe plus PhaQ; lanes 7 and 8, DNA probe plus PhaQ in the presence of 15 and 30 μg of PHB, respectively.

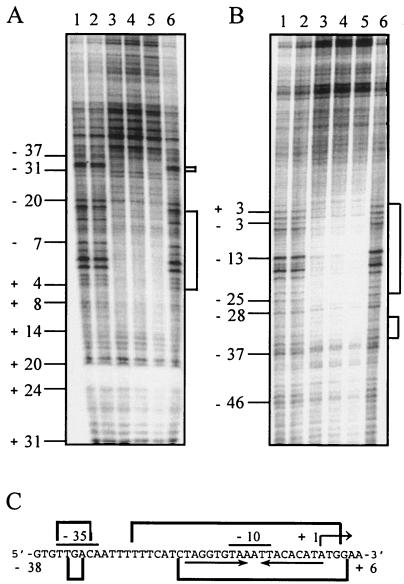

We next carried out DNase I footprinting analysis to define the binding site(s) for PhaQ in the phaQ promoter region. When the lower strand (template strand) of phaQ promoter-containing DNA was end labeled with 32P, the PhaQ protein protected two regions from DNase I cleavage. The longer one corresponds to the sequence −19 to +4 (relative to the transcriptional initiation site of phaQ), which covers a 19-bp imperfect inverted repeat (−18 to +1) (Fig. 4). The shorter one corresponds to the sequence −34 to −32. When the upper strand (non-template strand) of phaQ promoter-containing DNA was end labeled with 32P, the regions were protected by the PhaQ protein span −25 to +3 and −35 to −31 (Fig. 4). These protected regions overlap with the −35 and −10 regions of the σA-like promoter of phaQ, suggesting that PhaQ probably acts by interfering with RNA polymerase binding.

FIG. 4.

DNase I footprinting analysis of PhaQ binding to the phaQ promoter region. (A) A 0.4-kb SmaI-HindIII DNA fragment containing the phaQ promoter region (positions −356 to +39) and labeled with 32P at its HindIII site was incubated in the absence or presence of the PhaQ protein. Lanes 1 and 6, no PhaQ protein; lanes 2 to 5 contained 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 ng of the PhaQ protein, respectively. (B) A 0.36-kb BamHI-EcoRI DNA fragment containing the phaQ promoter region (positions −105 to + 249) and labeled with 32P at its BamHI site was incubated in the absence or presence of the PhaQ protein. Lanes 1 and 6, no PhaQ protein; lanes 2 to 5 contained 1.5, 3, 6, and 12 ng of the PhaQ protein, respectively. The numbers on the left indicate the positions of bases relative to the transcriptional initiation site of phaQ. Solid brackets on the right denote the protected regions.

To further confirm that PhaQ could interact specifically with the 19-bp inverted repeat, a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing the 19-bp inverted repeat (oligo I) and a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing a four-base mutation in the 19-bp inverted repeat (oligo II) (Fig. 3B) were used as probes in gel mobility shift assays. The result showed that PhaQ was capable of binding to oligo I but not to oligo II, suggesting that the wild-type 19-bp inverted repeat is a binding site for PhaQ.

Effect of mutations in the 19-bp inverted repeat on expression of the phaQ-xylE transcriptional fusion in vivo.

To examine the effect of mutations in the 19-bp inverted repeat on expression of the phaQ-xylE transcriptional fusion in vivo, a two-base substitution (AC to GT at positions −6 and −5) was introduced into the 19-bp inverted repeat to generate plasmid pGS1151 (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 1B, B. megaterium cells carrying plasmid pGS1151 exhibited approximately 2.4-fold higher XylE-specific activity than cells bearing plasmid pGS1142, suggesting that the 19-bp inverted repeat contributes, at least in part, to the control of phaQ expression in vivo.

Effect of artificial PHB granules on formation of PhaQ-DNA complex.

We next used purified PhaQ protein and a DNA fragment containing the phaQ promoter region (positions −105 to +39) end labeled with 32P for gel mobility shift assays to determine the effect of artificial PHB granules on formation of PhaQ-DNA complex in vitro. Artificial PHB granules were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. As a control, the effect of artificial PHB granules on the formation of BscR-DNA complex was also examined. The bscR gene has been previously demonstrated to encode a repressor that negatively regulates the transcription of the bscR-CYP102A3 operon of Bacillus subtilis (10). The results showed that the intensity of the shifted band representing PhaQ-DNA complex gradually decreased as the concentrations of artificial PHB granules gradually increased (Fig. 3C, lanes 6 to 8), whereas artificial PHB granules at the same range of concentrations did not interfere with the formation of BscR-DNA complex (Fig. 3C, lanes 2 to 4), suggesting that artificial PHB granules can specifically inhibit the formation of PhaQ-DNA complex.

Rebinding of PhaQ to artificial PHB granules in vitro.

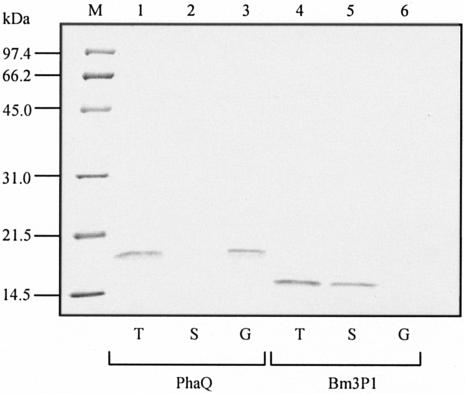

We next examined if PhaQ could bind artificial PHB granules directly. For comparison, we constructed two pQE30-based plasmids (pGS1041 and pGS253) that could overproduce His-tagged PhaQ protein and His-tagged Bm3P1 protein in E. coli, respectively. The Bm3P1 protein of B. megaterium is a soluble protein of 122 amino acids (12). After incubation of artificial PHB granules with either purified His-tagged PhaQ protein or purified His-tagged Bm3P1 protein, the reaction mixtures were separated into pellets and supernatants by centrifugation. Proteins were analyzed in an SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel. The result showed that the His-tagged PhaQ protein exhibited high affinity for artificial PHB granules, whereas the His-tagged Bm3P1 protein displayed no affinity for artificial PHB granules under similar assay conditions (Fig. 5). Results from Fig. 3C and 5 suggest that inhibition of formation of PhaQ-DNA complex by artificial PHB granules is probably through direct interaction between PHB and the PhaQ protein and raised the possibility that PhaQ might sense the presence of nascent PHB in vivo.

FIG. 5.

Rebinding of PhaQ to artificial PHB granules. Purified His-tagged PhaQ (100 ng) (lanes 1 to 3) or His-tagged Bm3P1 (120 ng) (lanes 4 to 6) was incubated with artificial PHB granules (100 μg) for 30 min. The reaction mixtures were then separated into pellets and supernatants by centrifugation. Proteins were analyzed in a SDS-12% polyacrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie brilliant blue. Results are for total input protein before incubation (T), protein in supernatant after centrifugation (S), and granule-associated protein after centrifugation (G). Lane M, molecular size markers.

Effect of PHB synthesis on phaQ expression in B. megaterium.

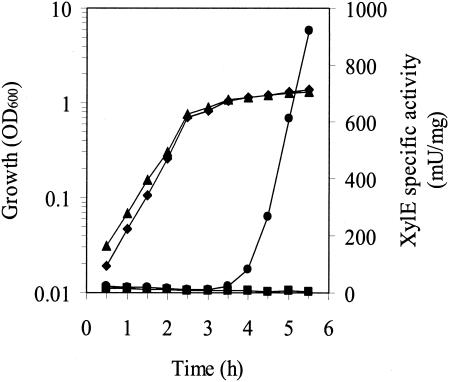

To explore whether phaQ expression would respond to the synthesis of PHB in vivo, we constructed the phaC disruption mutant BM695 as described in Materials and Methods. The correct disruption was verified by PCR and Southern blot analysis. The PHB-negative phenotype of the phaC disruption mutant was verified by Nile Blue A staining (18) (data not shown). Plasmid pGS1142 (Fig. 1A), which contains the xylE reporter gene preceded by both the promoter region and the coding region of phaQ, was introduced into the wild-type B. megaterium and the phaC disruption mutant. As shown in Fig. 6, XylE-specific activities at various time points in the phaC mutant bearing plasmid pGS1142 were very low. For the wild-type B. megaterium carrying plasmid pGS1142, there was a time lag of several hours before dramatic increases in XylE-specific activity were observed. This correlates well with previous observations that there was a lag phase for PHB accumulation in B. megaterium, after which PHB synthesis occurred at an accelerating rate (19). Taken together, these results suggest that PhaQ can sense the onset of PHB synthesis in vivo and is a PHB-responsive repressor.

FIG. 6.

Effect of PHB synthesis on phaQ expression in B. megaterium. Plasmid pGS1142 (Fig. 1A) was introduced into wild-type B. megaterium cells (circles and diamonds) and the phaC disruption mutant BM695 (squares and triangles). Overnight cultures were diluted 100-fold in fresh LB medium, and samples were taken at the indicated times to determine the absorbance at 600 nm (diamonds and triangles) and XylE-specific activity (circles and squares). OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

In this study we have provided evidence that the B. megaterium PhaQ protein plays a role in regulation of phaP expression as well as autoregulation. Our data also indicate that PhaQ is able to bind artificial PHB granules as well as DNA in vitro and sense the presence of PHB in vivo. These findings suggest that PhaQ is a PHB-responsive repressor, and PHB can act as an inducer for phaP expression in a PhaQ-mediated regulatory system.

By using different programs based on the method of Dodd and Egan (4), no typical helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif (20) could be detected in PhaQ. Moreover, PhaQ of B. megaterium does not exhibit significant amino acid sequence similarity to any protein with a known function in the data banks. Although the regulatory protein PhaR of R. eutropha shows similarity to PhaR of P. denitrificans at its N-terminal part, the N-terminal portion of PhaQ of B. megaterium does not show significant similarity to that of PhaR of either R. eutropha or P. denitrificans. The sequence of the cis-acting element for PhaQ is also quite different from the corresponding sequences of cis-acting elements for PhaR of P. denitrificans (15) and PhaR of R. eutropha (21). The size of PhaQ (146 amino acids) is also smaller than that of PhaR of P. denitrificans (195 amino acids) or PhaR of R. eutropha (183 amino acids). Nevertheless, PhaQ of B. megaterium shows high amino acid sequence similarity with the hypothetical PhaQ of Bacillus anthracis (57.5% identity and 63.0% similarity) (23) and with the hypothetical PhaQ of Bacillus cereus (56.2% identity and 61.6% similarity) (7). These results suggest that PhaQ represents a new class of transcriptional regulator. Further investigation of the crystal structure of PhaQ and identification of a novel DNA-binding motif of PhaQ are under way.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant NSC 90-2311-B-010-003 from the National Science Council of the Republic of China.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, A. J., and E. A. Dawes. 1990. Occurrence, metabolism, metabolic role, and industrial uses of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoates. Microbiol. Rev. 54:450-472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang, S., and S. N. Cohen. 1979. High frequency transformation of Bacillus subtilis protoplasts by plasmid DNA. Mol. Gen. Genet. 168:111-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiou, C. Y., H. H. Wang, and G. C. Shaw. 2002. Identification and characterization of the non-PTS fru locus of Bacillus megaterium ATCC 14581. Mol. Genet. Genomics 268:240-248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodd, I. B., and J. B. Egan. 1990. Improved detection of helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motifs in protein sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:5019-5026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fried, M., and D. M. Crothers. 1981. Equilibria and kinetics of lac repressor-operator interactions by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Nucleic Acids Res. 9:6505-6525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higuchi, R., B. Krummel, and R. K. Saiki. 1988. A general method of in vitro preparation and specific mutagenesis of DNA fragments: study of protein and DNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:7351-7367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ivanova, N., A. Sorokin, I. Anderson, et al. 2003. Genome sequence of Bacillus cereus and comparative analysis with Bacillus anthracis. Nature 423:87-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jurasek, L., and R. H. Marchessault. 2002. The role of phasins in the morphogenesis of poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) granules. Biomacromolecules 3:256-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee, T. R., H. P. Hsu, and G. C. Shaw. 2001. Transcriptional regulation of the Bacillus subtilis bscR-CYP102A3 operon by the BscR repressor and differential induction of cytochrome CYP102A3 expression by oleic acid and palmitate. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 130:569-574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis, P. J., and A. L. Marston. 1999. GFP vectors for controlled expression and dual labelling of protein fusions in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 227:101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liang, Q., L. Chen, and A. J. Fulco. 1998. In vivo roles of Bm3R1 repressor in the barbiturate-mediated induction of the cytochrome P450 genes (P450BM-3 and P450BM-1) of Bacillus megaterium. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1380:183-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Madison, L. L., and G. W. Huisman. 1999. Metabolic engineering of poly(3-hydroxyalkanoates): from DNA to plastic. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 63:21-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maehara, A., Y. Doi, T. Nishiyama, Y. Takagi, S. Ueda, H. Nakano, and T. Yamane. 2001. PhaR, a protein of unknown function conserved among short-chain-length polyhydroxyalkanoic acids producing bacteria, is a DNA-binding protein and represses Paracoccus denitrificans phaP expression in vitro. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 200:9-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maehara, A., S. Taguchi, T. Nishiyama, T. Yamane, and Y. Doi. 2002. A repressor protein, PhaR, regulates polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) synthesis via its direct interaction with PHA. J. Bacteriol. 184:3992-4002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maehara, A., S. Ueda, H. Nakano, and T. Yamane. 1999. Analyses of a polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granule-associated 16-kilodalton protein and its putative regulator in the pha locus of Paracoccus denitrificans. J. Bacteriol. 181:2914-2921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCool, G. J., and M. C. Cannon. 1999. Polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusion body-associated proteins and coding region in Bacillus megaterium. J. Bacteriol. 181:585-592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCool, G. J., and M. C. Cannon. 2001. PhaC and PhaR are required for polyhydroxyalkanoic acid synthase activity in Bacillus megaterium. J. Bacteriol. 183:4235-4243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCool, G. J., T. Fernandez, N. Li, and M. C. Cannon. 1996. Polyhydroxyalkanoate inclusion-body growth and proliferation in Bacillus megaterium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 138:41-48. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pabo, C. O., and R. T. Sauer. 1984. Protein-DNA recognition. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53:293-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pötter, M., M. H. Madkour, F. Mayer, and A. Steinbüchel. 2002. Regulation of phasin expression and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) granule formation in Ralstonia eutropha H16. Microbiology 148:2413-2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ray, C., R. E. Hay, H. L. Carter, and C. P. Moran. 1985. Mutations that affect utilization of a promoter in stationary-phase Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 163:610-614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Read, T. D., S. N. Peterson, N. Tourasse, et al. 2003. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature 423:81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 25.Satoh, Y., N. Minamoto, K. Tajima, and M. Munekata. 2002. Polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase form Bacillus sp. INT005 is composed of PhaC and PhaR. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 94:343-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Towbin, H., T. Staehelin, and J. Gordon. 1979. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 76:4350-4354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wieczorek, R., A. Pries, A. Steinbüchel, and F. Mayer. 1995. Analysis of a 24-kilodalton protein associated with the polyhydroxyalkanoic acid granules in Alcaligenes eutrophus. J. Bacteriol. 177:2425-2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.York, G. M., B. H. Junker, J. A. Stubbe, and A. J. Sinskey. 2001. Accumulation of the PhaP phasin of Ralstonia eutropha is dependent on production of polyhydroxybutyrate in cells. J. Bacteriol. 183:4217-4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.York, G. M., J. Stubbe, and A. J. Sinskey. 2001. New insight into the role of the PhaP phasin of Ralstonia eutropha in promoting synthesis of polyhydroxybutyrate. J. Bacteriol. 183:2394-2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.York, G. M., J. Stubbe, and A. J. Sinskey. 2002. The Ralstonia eutropha PhaR protein couples synthesis of the PhaP phasin to the presence of polyhydroxybutyrate in cells and promotes polyhydroxybutyrate production. J. Bacteriol. 184:59-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zinn, M., B. Witholt, and T. Egli. 2001. Occurrence, synthesis and medical application of bacterial polyhydroxyalkanoate. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 53:5-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]