Abstract

Background

The role for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in patients with thin melanoma (≤1mm) remains controversial. We examined a large cohort of patients with thin melanoma to better define predictors of SLN positivity.

Methods

Between 1995-2011, 781 patients with thin primary melanoma and evaluable clinicopathologic data underwent SLNB at our institution. Predictors of SLN positivity were determined using univariate and multivariate regression analyses, and patients were risk-stratified using a classification and regression tree (CART) analysis.

Results

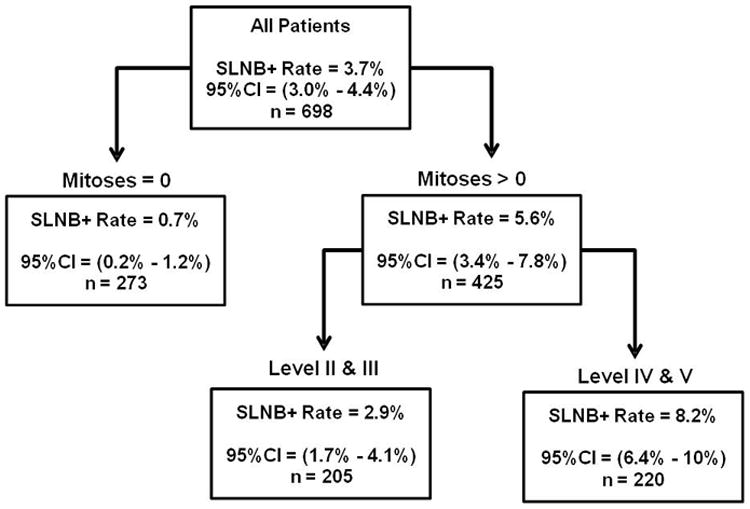

In the study cohort (n=781), 29 patients (3.7%) had nodal metastases. In the univariate analysis, mitotic rate (OR=8.11, p=0.005), Clark level (OR=4.04, p=0.003), and thickness (OR=3.33, p=0.011) were significantly associated with SLN positivity. In the multivariate analysis, MR (OR=7.01) and level IV-V (OR=3.45) remained significant predictors of SLN positivity. CART analysis initially stratified lesions by mitotic rate; non-mitogenic lesions (n=273) had a 0.7% SLN positivity rate versus 5.6% in mitogenic lesions (n=425). Mitogenic lesions were further stratified by Clark level; patients with level II-III had a 2.9% SLN positivity rate (n=205) versus 8.2% with level IV-V (n=220). With median follow up of 6.3 years, 5 SLN negative patients developed nodal recurrence and 4 SLN positive patients died of disease.

Conclusion

SLN positivity is low in patients with thin melanoma (3.7%) and exceedingly so in non-mitogenic lesions (0.7%). Appreciable rates of SLN positivity can be identified in patients with mitogenic lesions, particularly with concurrent level IV-V regardless of thickness. These factors may guide appropriate selection of patients with thin melanoma for SLNB.

Introduction

Patients with thin melanomas (≤1mm Breslow thickness) represent approximately 70% of the 76,000 new cases of melanoma each year in the US.1 While only 4-7% of patients with thin lesions die of melanoma, the deaths of these patients account for a significant proportion of the melanoma-specific mortality given the high incidence of thin melanoma.2, 3 The role for sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) in these patients remains controversial. Although nodal status has been identified as the most prognostic factor in several studies,3-5 the nodal positivity rate in patients with thin melanoma overall has been reported as approximately 5%,4, 6-8 which is less than the complication rate observed with the procedure.9

In order to guide a selective approach to SLNB for thin melanoma patients, multiple prior studies have attempted to define predictors of SLN positivity. The statistical analyses in many series, however, has been limited by the rarity of positive nodes.10-13 As a result, age,4 sex,4 Clark level,4, 14, 15 thickness,6, 14, 16, 17 the presence of vertical growth phase,18 mitotic rate,8, 14, 18, 19 ulceration,18, 19 and lymphovascular invasion6 have all been variably associated with SLN positivity. The inconsistency in reported prognostic factors has made determining which patients with thin melanoma should be considered for SLNB challenging.7, 20, 21

The most recent National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for melanoma identify a thickness of 0.76mm as a cut-off below which SLNB should generally not be recommended.20 The authors comment that the presence of putative “high risk” features such as ulceration and “high” mitotic rate only indicate that SLNB “may be considered on an individual basis”. For patients with 0.76-1mm T1a lesions, SLNB should be “discussed and considered”. For those with 0.76-1mm lesions with ulceration or mitotic rate ≥1/mm2 (T1b over 0.76mm), the procedure should be “discussed and offered”. In this study we investigate whether thickness or other factors better discriminate patients with T1 melanoma for selection for SLNB. While thickness is a known important prognostic factor for both melanoma-specific survival and nodal metastases, we hypothesize that in thin lesions, particularly very thin lesions, other factors such as Clark level may be more important for predicting nodal metastases. Here we present what we believe to be the largest reported single institution experience of patients with thin melanoma undergoing SLNB (including the largest experience of patients with lesions <0.76mm) in an attempt to further define patient and tumor characteristics predictive of SLN metastasis.

Methods

Between 1995-2011, 2258 patients with primary melanoma underwent SLNB at our institution. Review of patient demographics, pathology and operative reports identified all patients with thin (≤1mm) primary cutaneous melanoma and evaluable data (n=781). Maximal thickness was determined upon completion of wide local excision. Thus, patients with a positive deep margin on biopsy appropriately were upstaged after careful pathologic review and excluded if total thickness >1mm was found upon definitive resection. At our institution, SLNB is routinely performed for patients with melanoma >1mm in thickness. SLNB in patients with thin melanoma is performed selectively. This decision is based on individual patients' melanoma risk factors and comorbidities, discussion of the risks and benefits of the procedure, and patient preferences.

Patient variables analyzed were age and sex. Primary tumor characteristics included anatomic site, tumor thickness, Clark level, mitoses, tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TIL), regression, ulceration, lymphovascular invasion evident in H&E sections, and microsatellitosis. Pathologic variables were defined as previously reported.2 The following binary variables were used in the analyses: Clark level (II-III and unknown or IV-V), thickness (≤0.75 or 0.76-1mm), TIL (present/absent), and mitoses (present/absent). For lesions in which an individual characteristic was not reported, the characteristic was recorded as unknown.

The method for calculating mitotic rate varied slightly over the study period. Initially, mitotic rate was calculated based upon number of mitoses observed divided by the tumor area surveyed. This average value led to the possibility of reporting fractional mitoses (mitotic rate between 0-1). Current practice quantifies the number of mitoses in an identified hotspot, which results in any “mitogenic” lesion being reported as having at least one mitosis.22 Tumors with fractional mitoses in this data could therefore be considered T1b lesions (≥1/mm2), making the treatment of mitoses as binary variable (present/absent) congruent with the current AJCC classification of T1a/b status.23

SLNB was performed using the standard technique as previously described.8 All SLN specimens were reviewed by specialized surgical pathologists or dermatopathologists at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Lymph node specimens were stained for S100 and HMB45 as previously described.8 A false negative SLNB was defined as a regional nodal recurrence in a draining lymph node basin after a negative SLNB. These patients were identified by a query of our pathologic database from 1995-2011 for all nodal recurrences.

Predictors of SLN positivity were determined using univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses performed with SAS software (SAS Institute Inc.,Cary, NC). A classification tree analysis was performed using a recursive portioning algorithm (Salford Systems, San Diego, CA) to risk-stratify patients for SLN positivity.24 Only patients with known mitotic rate data were included in the regression analyses (n=698). The Kaplan-Meier method was used to determine melanoma-specific survival. For all analyses, a p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant. This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

Results

Patient and Tumor Characteristics

In all patients with thin melanoma (n=781), the median age was 51 (range 14-88) and the majority were male (55%). The median lesion thickness was 0.74mm, and 433 patients (55%) had T1b lesions. Mitogenic lesions were common (54%), as were those with level IV-V (44%), although only a single lesion was level V. Ulceration (4%), lymphovascular invasion (1%), and microsatellites (1%) were rarely observed.

Predictors of SLN Positivity

Among the 781 patients, 29 had a positive SLNB (3.7%). SLN positivity exceeded 5% in several patient subgroups: age ≤50, lesions that were level IV-V, had thickness ≥0.76, had present mitoses, had lymphovascular invasion, or had microsatellites. Table 1. Although infrequent, ulceration was not associated with any instances of SLN positivity (0/30 patients). Older age (>65 years) was also associated with a particularly low rate of SLN positivity (1.6%).

Table 1. SLN Positivity by Characteristic in 781 Patients with Thin Melanoma.

| Characteristic | SLN- Patients N (%) | SLN+ Patients N (%) | p-value | All Patients N (%) | Positive SLN Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.39 | ||||

| ≤40 | 201 (27) | 8 (28) | 209 (27) | 4.0 | |

| 41-65 | 429 (57) | 19 (66) | 448 (57) | 4.2 | |

| >65 | 122 (16) | 2 (7) | 124 (16) | 1.6 | |

|

| |||||

| Sex | 0.73 | ||||

| Male | 416 (55) | 17 (59) | 433 (55) | 3.9 | |

| Female | 336 (45) | 12 (41) | 348 (45) | 3.4 | |

|

| |||||

| Anatomic Site | 0.85 | ||||

| Axial | 441 (59) | 14 (48) | 455 (58) | 3.1 | |

| Extremity | 311 (41) | 15 (52) | 326 (42) | 4.6 | |

|

| |||||

| Clark Level | 0.006 | ||||

| II-III | 398 (53) | 7 (24) | 405 (52) | 1.7 | |

| IV-V | 322 (43) | 21 (72) | 343 (44) | 6.1 | |

| Unknown | 32 (4) | 1 (3) | 33 (4) | 3.0 | |

|

| |||||

| Thickness | 0.003 | ||||

| 0.01-0.75 | 419 (56) | 8 (28) | 427 (55) | 1.9 | |

| ≥0.76 | 333 (44) | 21 (72) | 354 (45) | 5.9 | |

|

| |||||

| Mitoses | 0.004 | ||||

| Absent | 271 (36) | 2 (7) | 273 (35) | 0.7 | |

| Present | 401 (53) | 24 (83) | 425 (54) | 5.6 | |

| Unknown | 80 (11) | 3 (10) | 83 (11) | 3.6 | |

|

| |||||

| TIL | 0.93 | ||||

| Absent | 185 (25) | 7 (24) | 192 (25) | 3.6 | |

| Present | 473 (63) | 19 (66) | 492 (63) | 3.9 | |

| Unknown | 94 (13) | 3 (10) | 97 (12) | 3.1 | |

|

| |||||

| Regression | 0.6 | ||||

| Absent | 488 (65) | 21 (72) | 509 (65) | 4.1 | |

| Present | 161 (21) | 4 (14) | 165 (21) | 2.4 | |

| Unknown | 103 (14) | 4 (14) | 107 (14) | 3.7 | |

|

| |||||

| Ulceration | 0.36 | ||||

| Absent | 617 (82) | 23 (79) | 640 (82) | 3.6 | |

| Present | 30 (4) | 0 (0) | 30 (4) | 0 | |

| Unknown | 105 (14) | 6 (21) | 111 (14) | 5.4 | |

|

| |||||

| LVI | 0.002 | ||||

| Absent | 577 (77) | 20 (70) | 597 (76) | 3.4 | |

| Present | 5 (1) | 2 (7) | 7 (1) | 29 | |

| Unknown | 170 (23) | 7 (24) | 177 (23) | 4.0 | |

|

| |||||

| Microsatellites | 0.001 | ||||

| Absent | 629 (84) | 25 (86) | 654 (84) | 3.8 | |

| Present | 5 (1) | 2 (7) | 7 (1) | 29 | |

| Unknown | 118 (16) | 2 (7) | 120 (15) | 1.7 | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor (T) Stage | 0.006 | ||||

| T1a | 248 (33) | 2 (7) | 250 (32) | 0.8 | |

| T1b | 409 (54) | 24 (83) | 433 (55) | 5.5 | |

| Unknown | 95 (13) | 3 (10) | 98 (13) | 3.1 | |

TIL (Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes), LVI (Lymphovascular Invasion)

In the univariate analysis, Clark level IV-V (p=0.003), thickness ≥0.76mm (p=0.011), and the presence of mitoses (p=0.005) were significantly associated with SLN positivity. Table 2. The presence of lymphovascular invasion and microsatellites were both associated with a markedly increased SLN positivity rate of 29% (95% CI=4%-71%). However, these factors were only present in 7 patients, and the low number of events precluded inclusion in the statistical model. In the reduced multivariate model, only Clark level (OR=3.45) and the presence of mitoses (OR=7.01) remained significantly associated with SLN positivity. Table 2.

Table 2. Factors Associated with SLN Positivity: Logistic Regression Analysis (n=698a).

| Frequency | SLN Positivity | Univariate | Reduced Multivariate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | N (%) | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 389 | 16 (4.1) | 1.28 | 0.544 | --- | --- |

| Female | 309 | 10 (3.2) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Anatomic Site | ||||||

| Axial | 403 | 13 (3.2) | 0.73 | 0.417 | --- | --- |

| Extremity | 295 | 13 (4.4) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Clark Level | ||||||

| II-III & Unk | 374 | 6 (1.6) | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| IV-V | 324 | 20 (6.2) | 4.04 | 0.003 | 3.45 | 0.009 |

|

| ||||||

| Thickness | ||||||

| 0.01-0.75 mm | 375 | 7 (1.9) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- |

| 0.76-1.00 mm | 323 | 19 (5.9) | 3.33 | 0.011 | --- | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Mitoses | ||||||

| Absent | 273 | 2 (0.7) | 1.00 | --- | 1.00 | --- |

| Present | 425 | 24 (5.6) | 8.11 | 0.005 | 7.01 | 0.009 |

|

| ||||||

| TIL | ||||||

| Absent | 191 | 7 (3.7) | 0.98 | 0.590 | --- | --- |

| Present & Unk | 507 | 19 (3.7) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Regression | ||||||

| Present | 146 | 4 (2.7) | 0.68 | 0.482 | --- | --- |

| Absent & Unk | 552 | 22 (4.0) | 1.00 | --- | --- | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Ulcerationb | ||||||

| Present | 27 | 0 (0) | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Not present or Unk | 671 | 26 (3.9) | --- | --- | --- | --- |

Analysis included only patients where mitotic rate was known.

Ulceration was not present in the tumor of any patients with a positive SLNB and thus could not be included. TIL (Tumor Infiltrating Lymphocytes), Unk (Unknown)

A classification tree analysis identified high and low risk groups for SLN positivity. Figure 1. The presence of mitoses was identified as the primary cut-point for risk stratification. Patients whose lesions had mitoses (n=425) had a 5.6% rate (95% CI=3.4%-7.8%) of SLN positivity compared to a 0.7% rate (95% CI=0.2%-1.2%) in those without mitoses (n=273). Patients with lesional mitoses were further stratified by Clark level. Patients with mitoses but level II-III (n=205) had a SLN positivity rate of 2.9% (95% CI=1.7%-4.1%), whereas patients with both mitoses and level IV-V (n=220) had a SLN positivity rate of 8.2% (95% CI=6.4%-10%).

Figure 1. Sentinel Lymph Node Positivity Rates by Classification and Regression Tree Analysis.

The presence of mitoses defined the optimal primary cut-point for differentiating the rate of SLN positivity. In patients with mitogenic tumors, Clark level further differentiated tumors into high and low risk for a positive SLNB. Analysis included only patients where mitotic rate was known. CI (confidence interval).

Given the prominence of thickness in the NCCN guidelines, the two risk factors identified in the multivariate analysis (present mitoses and Clark level IV-V) were further explored by stratifying on thickness (<0.76 and ≥0.76mm). For all patients, SLN positivity rates progressively increased with increasing numbers of these three factors. With one factor, the SLN positivity rate was 2.1% (n=234), with two it was 4.7% (n=234), and with all three it was 9.3% (n=140). Among patients with none of these factors, the SLN positivity rate was 0% (n=173). Interestingly, in patients with all three factors but over 65 years of age (n=30), the SLN positivity rate was also 0%.

Each combination of factors was then analyzed separately. Table 3. In patients with lesions ≥0.76mm, those with no mitoses and Clark level II-III had a SLN positivity rate of 3%. The rate increased to 3.8% for lesions with Clark level IV-V but no mitoses, and in lesions ≥0.76mm with mitoses (T1b), but level II-III, the SLN positivity rate was 4%. In contrast, in patients with <0.76mm lesions, the absence of elevated Clark level and mitoses was associated with a 0% SLN positivity rate. The presence of either elevated Clark level or mitoses alone was associated with a low rate (1.4% and 1.9% respectively) of SLN positivity. In the patients with very thin lesions with both mitoses and elevated Clark level (n=80), however, the rate increased to 6.3%.

Table 3. The Contribution of Thickness to SLN Positivity.

| Lesions <0.76mm | Lesions ≥0.76mm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Risk Featuresa | All Patients | SLN Positive Patients N (%) | NCCN Guidelines | All Patients | SLN Positive Patients N (%) | NCCN Guidelines |

| None | 173 | 0 (0) | NR | 60 | 2 (3.0) | Consider |

| Clark Level IV-V | 70 | 1 (1.4) | NR | 53 | 2 (3.8) | Consider |

| Present Mitoses | 104 | 2 (1.9) | NR | 101 | 4 (4.0) | Offer |

| Mitoses & Level IV-V | 80 | 5 (6.3) | NR | 140 | 13 (9.3) | Offer |

High risk features were defined by multivariate analysis as: present mitoses and level IV-V. Thickness ≥0.76mm was included given its prominence in the NCCN guidelines.20 Unknown factors were considered low risk. NR (Not Recommended).

Outcomes following SLNB

Patients with a positive SLNB (n=29) were followed for a median of 6.3 years. Four of these patients (14%) died of disease. Table 4. All were male, and the average age at diagnosis was 40. Lesion thickness ranged from 0.9-1mm, and 3 were known to be mitogenic (one unknown mitoses). Only two patients in the entire cohort had more than one positive SLN, and both died of disease. Overall 27 of the 29 patients with positive SLNB underwent completion lymphadenectomy, and two patients were found to have a positive non-SLN (both of these patients were alive 3 years after surgery).

Table 4.

Survival in Patients with Positive and False Negative SLNB.

| Overall, N (% of metastatic nodes) | Died of Disease, N (%) | 5-year Disease-Specific Survival | |

|---|---|---|---|

| False Negative SLNB | 5 (15) | 2 (40) | 60% |

| Positive SLNB | 29 (85) | 4 (14) | 88% |

Five patients were identified as having a regional nodal recurrence after a negative SLNB (false negative rate = 15%). Although too small a sample for statistical analysis, patients with a false negative SLNB tended to have a number of high risk features (thickness ≥0.76mm in 3/5, present mitoses in 4/4, level IV-V in 4/5). Two of these patients died of melanoma (40%). Table 4.

Discussion

The role for SLNB in patients with thin melanoma remains controversial. The present study reports an expectedly low overall rate of SLN positivity (3.7%). The regional nodal metastatic rate was 4.4% overall when false negative SLN patients were included, which is consistent with the nodal positivity rate of 4.3% among our institution's pre-SLN era population of patients with thin melanoma and long term follow-up.25 Of potential importance, this study identifies the presence of mitoses and Clark level IV-V as significantly associated with SLN positivity in the multivariate analysis. Thickness ≥0.76mm was associated with SLN positivity only in the univariate analysis.

Thickness,6, 14, 16, 17 Clark level,4, 14, 15 and mitotic rate8, 14, 18, 19 are the most frequently reported factors associated with SLN positivity in previous studies, and our findings support that these are important factors in defining an individuals' likelihood of SLN positivity. That thickness did not remain significantly associated with SLN positivity in the multivariate analysis may be explained, in part, by the selection bias inherent in studies of SLNB for T1 melanoma. Many centers rarely perform the procedure in patients with very thin lesions, and in studies with predominantly thicker T1 melanomas the predictive importance of Clark level may be less relevant. The median thickness in our study was 0.74mm, which is lower than other studies wherein reported median thickness ranges from 0.85-0.95mm.6, 19

The exact “threshold” rate of SLN positivity for performing SLNB in patients with T1 melanomas can be debated and depends on patient factors (e.g. age, comorbidities, and preferences) and the procedure's implications with respect to staging, prognostication, and therapy. In our study, the presence of mitoses was the most important factor for predicting SLN metastases. Patients without mitoses (regardless of other factors) have a SLN positivity rate of 0.7% (95% CI=0.2-1.2%). Even in the subset of patients with lesions ≥0.76mm, the SLN positivity rate was just 3% in the absence of mitoses. Thus, among non-mitogenic lesions, SLNB would be hard to justify based on risk of nodal positivity. Overall, among mitogenic lesions, the SLN positivity rate was found to be 5.6% (95% CI=3.4-7.8%). The risk for SLN positivity appeared to be heterogeneous among mitogenic lesions depending upon the concomitant presence of other factors, particularly Clark level. In patients with mitogenic lesions but with level II-III, the SLN positivity rate was just 2.9% (95% CI=1.7-4.1%).

Historically, Clark level was shown to be an important prognostic factor in patients with melanoma.26 However, while its prognostic role for melanoma-specific survival may be less relevant when mitotic rate is considered, it appears to play an important role in the risk-stratification of patients with mitogenic T1 melanomas. Given the variability in the dermal thickness among patients, it may be that in the thinnest lesions Clark level provides meaningful prognostic information beyond tumor thickness. The lymphatic density has been reported to be greater within the papillary dermis (level II-III), but associated with smaller diameter vessels than in the reticular dermis (level IV).27, 28 Although the effect of this anatomic difference on nodal metastasis is unknown, it may provide a mechanism to explain the association with Clark level.

Among patients with elevated Clark level and mitoses, the SLN positivity rate was 8.2% (95% CI: 4.9% - 12.6%). Moreover, in the subset of these lesions <0.76mm, the SLN positivity rate was 6.3% (95% CI: 2.1% - 14.0%); in comparison, among lesions ≥0.76mm with mitoses, but level II-III the rate was 4.0% (95% CI: 1.1% - 9.8%). Current NCCN guidelines suggest that SLNB is generally not indicated for the former, but should be “discussed and offered” for the latter.20 Our data are consistent with previous reports demonstrating the strong prognostic significance of mitoses in T1 melanomas.8, 14, 18, 19 The current data support perhaps a less rigid view of the thickness cut-off of 0.76mm and suggest that Clark level may be clinically valuable in risk stratifying and counseling patients with mitogenic T1 melanomas for SLNB. In the overall study cohort, the SLN positivity rate was 6.2% for Clark level IV-V, 5.9% for lesions>0.75, and 5.6% for mitogenic lesions. Routine use of SLNB based upon Clark level or any other single factor, however, incorporates a heterogeneous group of patients whose risk of SLN positivity can be further refined by accounting for multiple high risk factors. Moreover, several factors (such as age) may contribute in a more nuanced way to the risk for SLN positivity although not clearly identified in our multivariate model. For instance, it should be noted that even when lesions were ≥0.76mm, mitogenic, and level IV-V, patients over 65 years old had a 0% rate of SLN positivity in the current study.

The other component of T1b stage is the presence of ulceration. In our patients ulceration was rarely recorded (4%) and not associated with SLN positivity. Our results would not support stronger consideration for SLNB in patients with thicker T1b melanomas that are classified as such by virtue of ulceration alone. That we find no association of ulceration with SLN positivity highlights the proposition that factors associated with survival may not inherently be associated with nodal metastasis.

Like prior investigations, this study is limited by its retrospective nature, particularly in the potential biases introduced through patient selection for SLNB. Indeed, our study population is enriched for males, present mitoses, and elevated thickness and Clark level in comparison to an unselected group of pre-SLN era thin melanoma patients from our institution.25 Both male sex and present mitoses were identified as a risk factor for regional nodal recurrence in that analysis, which, along with results from other published series, likely influenced the selection of our current study population and potentially our results. These patients clearly are not a complete representation of the general population of thin melanoma patients. We believe, despite these limitations, that the results presented may add useful prognostic information for the selection of patients with T1 melanoma for SLNB, given the large sample size and the greater thickness range of T1 melanomas represented in this study compared to many other series of SLNB.

In conclusion, while the SLN positivity rate is low in patients with thin melanoma (3.7%), appreciable rates of positivity can be identified across all thicknesses in patients with mitoses and level IV-V. Clark level may be a better discriminant for predicting SLN metastases than thickness in mitogenic T1 melanomas. Regardless of thickness, in the absence of mitoses the SLN positivity rate is so low (0.7%) as to call into question offering the procedure. Our findings may help guide the selective performance of SLNB in patients with thin melanoma.

Synopsis.

In patients with thin melanoma undergoing SLN biopsy, we identify a low rate (3.7%) of nodal metastases. Mitoses and elevated Clark level were significantly associated with SLN metastases and may help identify patients with an appreciable incidence of SLN positivity.

Footnotes

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

The authors declare no funding or conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R, Altekruse SF, Kosary CL, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Cho H, Mariotto A, Eisner MP, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975-2009 (Vintage 2009 Populations) National Cancer Institute; Bethesda, MD: 2011. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gimotty PA, Guerry D, Ming ME, et al. Thin primary cutaneous malignant melanoma: a prognostic tree for 10-year metastasis is more accurate than American Joint Committee on Cancer staging. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(18):3668–76. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McKinnon JG, Yu XQ, McCarthy WH, Thompson JF. Prognosis for patients with thin cutaneous melanoma: long-term survival data from New South Wales Central Cancer Registry and the Sydney Melanoma Unit. Cancer. 2003;98(6):1223–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright BE, Scheri RP, Ye X, et al. Importance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Arch Surg. 2008;143(9):892–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.9.892. discussion 899-900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karakousis GC, Gimotty PA, Czerniecki BJ, et al. Regional nodal metastatic disease is the strongest predictor of survival in patients with thin vertical growth phase melanomas: a case for SLN Staging biopsy in these patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(5):1596–603. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9319-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murali R, Haydu LE, Quinn MJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin primary cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg. 2012;255(1):128–33. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182306c72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warycha MA, Zakrzewski J, Ni Q, et al. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node positivity in thin melanoma (<or=1 mm) Cancer. 2009;115(4):869–79. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kesmodel SB, Karakousis GC, Botbyl JD, et al. Mitotic rate as a predictor of sentinel lymph node positivity in patients with thin melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12(6):449–58. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2005.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morton DL, Cochran AJ, Thompson JF, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for early-stage melanoma: accuracy and morbidity in MSLT-I, an international multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):302–11. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000181092.50141.fa. discussion 311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hershko DD, Robb BW, Lowy AM, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in thin melanoma patients. J Surg Oncol. 2006;93(4):279–85. doi: 10.1002/jso.20415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong SL, Brady MS, Busam KJ, Coit DG. Results of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(3):302–9. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stitzenberg KB, Groben PA, Stern SL, et al. Indications for lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy in patients with thin melanoma (Breslow thickness < or =1.0 mm) Ann Surg Oncol. 2004;11(10):900–6. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs IA, Chang CK, DasGupta TK, Salti GI. Role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin (<1 mm) primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(5):558–61. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ranieri JM, Wagner JD, Wenck S, et al. The prognostic importance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in thin melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(7):927–32. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lowe JB, Hurst E, Moley JF, Cornelius LA. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(5):617–21. doi: 10.1001/archderm.139.5.617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cecchi R, Buralli L, Innocenti S, De Gaudio C. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanomas. J Dermatol. 2007;34(8):512–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kunte C, Geimer T, Baumert J, et al. Prognostic factors associated with sentinel lymph node positivity and effect of sentinel status on survival: an analysis of 1049 patients with cutaneous melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2010;20(4):330–7. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0b013e32833ba9ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oliveira Filho RS, Ferreira LM, Biasi LJ, et al. Vertical growth phase and positive sentinel node in thin melanoma. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36(3):347–50. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000300009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Han D, Yu D, Zhao X, et al. Sentinel node biopsy is indicated for thin melanomas >/=0.76 mm. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19(11):3335–42. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2469-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, et al. Melanoma, Version 2.2013: Featured Updates to the NCCN Guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2013;11(4):395–407. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong SL, Balch CM, Hurley P, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: American Society of Clinical Oncology and Society of Surgical Oncology joint clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(23):2912–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.3519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scolyer RA, Shaw HM, Thompson JF, et al. Interobserver reproducibility of histopathologic prognostic variables in primary cutaneous melanomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27(12):1571–6. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200312000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199–206. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.4799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steinberg DCP. CART: Tree-Structured Non-Parametric Data Analysis. San Diego: Salford Systems; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karakousis GC, Gimotty PA, Botbyl JD, et al. Predictors of regional nodal disease in patients with thin melanomas. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(4):533–41. doi: 10.1245/ASO.2006.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Soong SJ, et al. Final version of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(16):3635–48. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.16.3635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clark WH, Jr, From L, Bernardino EA, Mihm MC. The histogenesis and biologic behavior of primary human malignant melanomas of the skin. Cancer Res. 1969;29(3):705–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossi A, Sozio F, Sestini P, et al. Lymphatic and blood vessels in scleroderma skin, a morphometric analysis. Hum Pathol. 2010;41(3):366–74. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2009.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]