Abstract

Background

Diarrhea is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in under-five children in developing countries including Ethiopia. Therefore, up-to-date data on etiologic agent and susceptibility pattern are important for the management of bacterial diarrhea in under-five children, which was the main objective of this study.

Method

A cross-sectional study was conducted at Hawassa Adare Hospital and Millennium Health Center from June 6 to October 28, 2011. A total of 158 under-five children with diarrhea were selected using convenient sampling technique. Demographic and clinical data were collected using questionnaire. Fecal samples were collected and processed for bacterial isolation, and antimicrobial susceptibility testing following standard bacteriological techniques.

Result

A total of 158 fecal samples were collected from 81(51.3%) males and 77(48.7%) females of under-five children with diarrhea. Of the 158 fecal samples, 35(22.2%) bacterial pathogens were isolated. The isolated bacteria were Campylobacter species, 20 (12.7%), Shigella species, 11 (7.0%), and Salmonella species, 4 (2.5%). The majority of the isolates were sensitive to Chloramphenicol, Ciprofloxacin, Nalidixic acid and Cotrimoxazol and high rate of drug resistance was observed against Erythromycin and Amoxicillin.

Conclusions

The finding of this study indicates that Campylobacter species were the predominant etiologies and the presence of bacterial isolates resistant to the commonly prescribed drugs for treating diarrhea in children. Therefore, periodic monitoring of etiologic agent with their drug resistant pattern is essential in the management of diarrhea in children.

Keywords: Diarrhea, Bacterial pathogen, Antimicrobial drugs, Under-five children, Hawassa, Ethiopia

Introduction

Diarrhea is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality of under-five children in developing countries. Here, the average number of episodes of diarrhea per child per year within this age group is 3.2 (1, 2). Bacterial diarrhea in under-five children is commonly caused by Salmonella, Shigella Campylobacter species and diarrheogenic E. coli (3, 4, 5). Of the pathogens causing diarrhea, Shigella continues to play a major role in etiology of inflammatory diarrhea and dysentery. Thus, it presents a serious challenge to public health authorities worldwide (1). The prevalence of Salmonella infection varies depending on the water supply, waste disposal, food preparation practices and climate. The commonest illness among children caused by Salmonella is gastroenteritis (6). Campylobacter is one of the most frequently isolated bacteria from stools of infants with diarrhea in developing countries as result of contaminated food and water (7).

There were different prevalence rates of causative agents in different regions. A study conducted in Gondar on children with diarrhea isolated Campylobacter, Salmonella and Shigella species with prevalence of 10.5%, 5.2% and 5.2%respectively (8). Another related study conducted in Jimma also reported an isolation rate of 11.6%, 4.9% and 5.8% for Campylobacter, Salmonella and Shigella species respectively (9). Shigella species was also isolated from 34.6% of the patients who attended health facilities in Hawassa Town (10).

Development of antimicrobial resistance by enteric pathogens like Shigella, Campylobacter and Salmonella species against easily accessible and commonly prescribed drugs has become a major concern throughout the world, particularly in developing countries like Ethiopia (11).

According to Asrat (2008), the most strains of Shigella species in Ethiopia was resistant to Erythromycin (100.0%), Tetracycline (97.3%), Cephalothin (86.7%), Ampicillin (78.7%), Chloramphenicol (74.7%) and Sulfonamide (54.7%) (12). Moreover, Yismaw in Gondar also revealed that there was high resistance of Shigella species against Ampicillin (79.9%), Tetracycline (86 %) and Cotrimoxazole (73.4%) (13). In addition, a similar study done in Harar on drug susceptibility of Shigella species showed high resistance against Amoxicillin (100), Ampicillin (100%) and Tetracycline (70.6%) (14), whereas resistance for Salmonella species against Ampicillin (81.2%), Cephalothin (86.4%), Chloramphenicol (83.7%), Erythromycin (100.0%), Gentamicin (75.6%), Sulfonamide (81.1%), Tetracycline (94.5%) and Trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (75.7%) was reported by Asrat (2008) done in Ethiopia (12). Likewise, the resistance to Amoxicillin (100%), Ampicillin (100%), Tetracycline (71.4%) and Chloramphenicol (62.3%) of Salmonellas species was reported by Reda et al in Harar (14). Moreover, a study on antimicrobial susceptibility of Shigella species in Hawassa, indicated the presence of high resistance against Gentamicin (96%), Nalidixic acid (90%), Ampicillin (93%), Erythromycin (90%) and Tetracycline (90%) (10). Multiple drug resistant Shigella isolates which showed resistance to six antibiotics (Ampicillin, Erythromycin, Cephalothin, Chloramphenicol, Tetracycline and Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) have also been observed (10). Another study conducted in Jimma on drug susceptibility profile of Campylobacter species reported that the isolates showed 50% and 60% resistance rate to Ampicillin and Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole respectively (9).

According to Ethiopia's Demographic and Health Survey of 2005, children who lived in the Southern Nation Nationalities and People (SNNP) Region were more susceptible to episodes of diarrhea (25.1 %) than those who lived in other regions (15). To our knowledge, there are no published studies on etiologies of diarrhea in under-five children in SNNPR.

Therefore, the purpose of this study was to identify bacterial etiologies of diarrhea and determine their antimicrobial susceptibility in under-five children against commonly prescribed drugs in Hawassa, South Ethiopia.

Materials and Methods

A prospective cross-sectional study was conducted in Adare Hospital and Millennium Health Center in Hawassa, Ethiopia, from June 6 to October 28, 2011 to isolate common bacterial etiologies of diarrhea in under-five children, and assess their susceptibility patterns.

A total of 158 under-five children affected by diarrhea were included in the study. But, children who had taken antibiotic within seven days before data collection, those who were above 5 years old, and children whose parents/guardians were not voluntary were excluded from the study. Medical history was taken from each child and informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians before sample collection was attempted. All the relevant demographic, clinical and laboratory data were recorded and transferred to the questionnaire prepared for this study.

Specimen Collection and Pathogen Identification: Freshly passed stool and rectal swab were collected, placed immediately in Cary Blair transport medium (Oxoid Ltd, Basingstoke, UK) and transported to the laboratory within six hours of collection. For identification of Shigella and Salmonella species, specimens were placed in Selenite F enrichment broth (Oxoid) and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours, then subcultured onto deoxycholate agar (DCA) and xylose lysine deoxycholate agar (XLD) (Oxoid) agar and then incubated at 37°C for 18–24 hours.

The growth of Salmonella and Shigella species was detected by their characteristic appearance on XLD agar (Shigella: red colonies, Salmonella red with a black centre) and DCA (Shigella: pale colonies, Salmonella black centre pale colonies). The suspected colonies were further tested through a series of biochemical tests to identify Shigella and Salmonella species. Salmonella species were further confirmed by agglutination test with polyvalent anti-sera and Shigella isolates were sero-grouped by the slide agglutination test using commercially available antisera (Denka Seikn Co. Ltd, Japan) (16, 17).

For isolation and identification of Campylobacter species, the samples were inoculated on Charcoal Cefoperazone Deoxycholate (CCD) agar and incubated at 42°C for 48 hours. Campylobacter species were identified by growth on CCD medium with small gray colonies, at microaerophilic condition, growth at 42°C, positive oxidase and catalase test and Gram-staining reaction and morphology (16, 17).

Susceptibility testing: Antimicrobial drug susceptibility testing was carried out by using disk diffusion method, according to guidelines of Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) (18). The antibiotic discs used and their concentration were: Ampicillin (AMP, 10-µg), Chloramphenicol (C, 30-µg), Gentamicin (CN, 10-µg), Nalidixic acid (NA, 30-µg), Amoxicillin (AMX, 30-µg), Tetracycline (TE, 30-µg), Ceftriaxone (CRO, 30-µg), Cotrimoxazole (SXT, 30-µg), Erythromycin (E, 15-µg), Cephalothin (CF, 30-µg) and Ciprofloxacin (CIP,5-µg). All antibiotics were obtained from Oxoid Limited, Basingstoke Hampshire, UK. A standard inoculum adjusted to 0.5 McFarland was swabbed on to Muller-Hinton agar (Oxoid Ltd. Bashingstore Hampaire, UK); antibiotic discs were dispensed after drying the plate for 3–5 minutes and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The reference strains used as control were Pseudomonas aeruginosa ATCC 27853, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922, Shigella flexneri ATCC 12021, Salmonella typhimurium ATCC 13311 and Campylobacter jejuni ATCC 33560.

Ethical clearance was secured from the Ethical Clearance Committee of the College of Public Health and Medical Sciences, Jimma University. Permission was also obtained from Hawassa Regional Health Bureau, Hawassa Adare Hospital, and Hawassa Millennium Health Center.

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 16.0 computer software. Comparisons were made using Chi-square test. P-value of <0.05 was considered indicative of a statistically significant difference.

Results

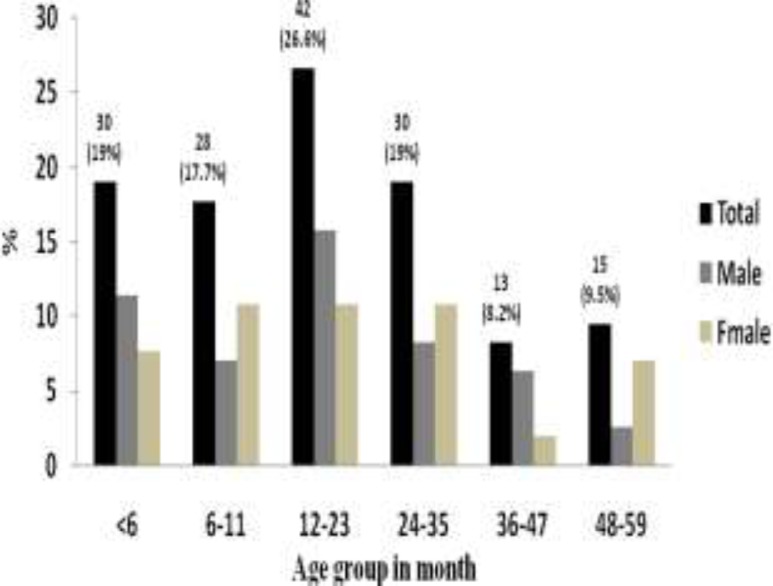

A total of 158 under-five children with diarrhea participated in the study. Seventy-one (44.9%) of the children were from Millennium Health Center and 87 (55.1%) of them were from Adare Hospital. Out of the 158 study participants, 81 (51.3%) were males and 77 (48.7%) were females resulting in an overall male to female ratio of 1.1:1. The age of the participants ranged from 1–58 months with a mean of 19.59 months (±SD14.89): thirty (19%) of them were younger than 6 months, 42 (26.6%) were between 12 and 23 months, and 30(19%) were between 24 and 35 months old (Figure 1).

Fig 1.

Distribution of participants by age and sex

The bacterial pathogens were identified from 35 (22.2%) study participants of which Campylobacter species was the leading isolate that accounted for 20 (12.7%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Frequency of bacterial pathogens isolated from fecal sample of children with diarrhea at Adare Hospital and Millennium Health Center from June to October 2011, Hawassa, South Ethiopia

| Bacterial pathogens | Frequency | |

| Positive No (%) |

Negative No (%) |

|

| Campylobacter Spp. | 20 (12.7) | 138(87.3) |

| Shigella species | 11 (7.0) | 147(93.0) |

| Salmonella species | 4 (2.5) | 154 (97.5) |

In this study, Shigella species was the second dominant bacterial etiology in under-five children with diarrhea and sero-grouping data indicating that all Shigella isolates were found to be S. flexneri. S. flexneri was frequently isolated from children with dysentery, above 24 months of age and with three days' duration of diarrhea. Isolation rate of S. flexneri showed statistically significant association with dysenteric stool [P=<0.001] and children aged 36–47 months [P=0.025] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical findings in association with culture result for Salmonella, Shigella and Campylobacter species among under-five children at Adare Hospital and Millennium Health Center, June to October 2011, Hawassa, South Ethiopia (*Blood and Mucoid, ** p = value statistical significance association)

| Demographic & Clinical data |

Salmonella spp (n=4) | Shigella spp (n=11) | Campylobacter spp (n=20) | |||

| Positive No (%) |

Negative No (%) |

Positive No (%) |

Negative No (%) |

Positive No (%) |

Negative No (%) |

|

| Age group | ||||||

| <6 | 1 (3.3) | 29 (96.7) | 1 (3.3) | 29 (96.7) | 5 (16.7) | 25 (83.3) |

| 6–11 | 0 (0) | 28 (100) | 1 (3.6) | 27 (96.4) | 3 (10.7) | 25 (89.3) |

| 12–23 | 1 (2.4) | 41 (97.6) | 2 (4.8) | 40 (95.2) | 8 (19) | 34 (81) |

| 24–35 | 1 (3.3) | 29 (96.7) | 2 (6.7) | 28 (93.3) | 1 (3.3) | 29 (96.7) |

| 36–47 | 0 (0) | 13 (100) | 4 (30.8) | 9 (69.2) | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) |

| 48–59 | 1 (6.7) | 14 (93.3) | 1 (6.7) | 14 (93.3) | 0 (0) | 15 (100) |

| p=0.025** | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1(1.2%) | 80(98.8) | 4(4.9%) | 77(95.1%) | 11(13.6%) | 70 (86.4%) |

| Female | 3(3.9%) | 74 (96.1%) | 7(9.1%) | 70 (90.9%) | 9(11.7%) | 68 (88.3%) |

| Clinical symptom | ||||||

| Vomiting | 0 (0) | 52 (100) | 4 (7.7) | 48 (92.3) | 5 (9.6) | 47 (90.4) |

| Fever | 2 (3.9) | 50 (96.2) | 4 (7.7) | 48 (92.3) | 9(17.3) | 43 (82.7) |

| Abdominal pain | 2 (5.6) | 34 (94.4) | 1 (2.8) | 35 (97.2) | 5 (13.9) | 31 (86.1) |

| Dehydration | 0 (0) | 16 (100) | 2 (12.5) | 14 (87.5) | 0 (0) | 16 (100) |

| Consistency | ||||||

| Watery | 1 (1) | 99 (99) | 5 (5) | 95 (95) | 14 (14.0) | 86 (86.0) |

| Mucoid | 3 (6.8) | 41 (93.2) | 3 (6.8) | 41(93.2) | 5(11.4) | 39 (88.6) |

| Bloody | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 1(100) | 0(0) | 1(100) |

| Mixed* | 0 (0) | 8 (100) | 5 (62.5) | 3(37.5) | 1(12.5) | 7(87.5) |

| p< .001** | ||||||

| Duration of diarrhea | ||||||

| 1–5 days | 3 (2.4) | 122 (97.6 | 11 (8.8) | 114 (91.2) | 17 (13.6) | 108 (86.4) |

| 6–10 days | 1 (4.4 | 22 (95.6) | 0 (0) | 23 (100) | 2 (8.7) | 21 (91.3) |

| 11–15 days | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 1 (20) | 4 (80) |

| ≥16 days | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) | 0 (0) | 5 (100) |

| Total | 4 (2.5) | 154 (97.5) | 11 (7) | 147 (93) | 20 (12.7) | 138 (87.3%) |

Salmonella species were identified as serogroup B (3, 1.9%) and serogroup A (1, 0.6%). Although the isolation rates of Salmonella species were low, threefourth of the isolates were taken from children above 12 months of age. Similarly, most of the Campylobacter species was detected from children of less than 24 months old. A total of thirty-five bacterial pathogens [4 Salmonella species, 11 Shigella species and 20 Campylobacter species] were subjected to antimicrobial susceptibility tests using disk diffusion method (Table 3). Accordingly, Shigella flexneri showed high resistance against Amoxicillin (100%), Erythromycin (90.9%) and Ampicillin (63.6%). However, low resistance rate was observed against Gentamicin (27.3%) and Chloramphenicol (9.1%) and there was no resistance rate observed against Ciprofloxacin, Nalidixic acid, and Cotrimoxazole (Table 3).

Table 3.

Drug resistance pattern of bacterial species from under-five children at Adare Hospital and Millennium Health Center, June to October 2011, Hawassa, South Ethiopia

| Bacterial Isolates |

No (% ) of isolates resistance to | |||||||||||

| n | AP | T | C | CIP | E | NA | ST | CRO | AMC | CF | GM | |

| Shigella flex. | 11 | 7(63.6) | 6(54.5) | 1(9.1) | 0(0) | 10(90.9) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 6(54.5) | 11(100) | 0(0) | 3(27.3) |

| Salmonella spp. | ||||||||||||

| Serogroups B | 3 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 3(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 3(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) |

| Serogroups A | 1 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(100) | 1(100) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 1(100) | 0(0) |

| Total | 4 | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 4(100) | 1(25) | 0(0) | 3(75) | 0(0) | 1(25) | 0(0) |

|

Campylobacter spp |

20 | 6(30) | 3(15) | 0(0) | 2(10) | 11(55) | 4(20) | 4(20) | 0(0) | 16(80) | 14(70) | 14(70) |

| Total | 35 | 13(3.1) | 9(25.7) | 1(2.9) | 2(5.7) | 25(71.4) | 5(14.3) | 4(11.4) | 9(25.7) | 27(77.1) | 15(42.8) | 15(42.8) |

AP = Ampicillin, CRO = Ceftriaxone, NA = Nalidixic acid, AMC = Amoxicillin, C = Chloramphenicol, GM = Gentamicin, ST = Cotrimoxazol, T = Tetracycline, CIP = Ciprofloxacin, E = Erythromycin, CF = Cephalothin

All Shigella flexneri showed multiple drug resistance (MDR) (resistance to two or more drugs), and of these, 3 (27.3%), 3(27.3%) and 1(9.1%) were resistant to four, five and six drugs respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Antibiogram of bacterial pathogens isolated from under-five children with diarrhea at Adare Hospital and Millennium Health Center June to October 2011, Hawassa, South Ethiopia

| Organisms | Antibiogram | ||||||

| R1 | R2 | R3 | R4 | R5 | R6 | ||

| No of | No | No | No | No | No | No | |

| Isolation | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | (%) | |

| Shigella flexneri | 11 | - | 1(9.1) | 3(27.3) | 3(27.3) | 3(27.3) | 1(9.1) |

| Salmonella spp. | |||||||

| Serogroups B | 3 | - | - | 3(75) | - | - | - |

| Serogroups A | 1 | - | - | - | 1(25) | - | - |

| Total | 4 | - | - | 3(75) | 1(25) | - | - |

| Campylobacter spp. | 20 | 1(5) | 5(25) | 9(45) | 4(20) | 1(5) | - |

| Total | 35 | 1(2.9) | 6 (17.1) | 15(42.9) | 8(22.9) | 4(11.4) | 1(2.9) |

R1= Resistance for one drug, R2= Resistance for two drugs, R3= Resistance for three drugs, R4= Resistance for four drugs, R5= Resistance for five drugs, R6= Resistance for six drugs , - =No resistance

The overall rate of resistance of Salmonella species was high for Erythromycin (100%) and Ceftriaxone (75%). But, lower resistance rate was observed against Nalidixic acid (25%). Among Salmonella serogroups, Serogroup B showed high resistance against Erythromycin (100%), and Ceftriaxone (100%). Similarly Serogroup A showed 100% resistance against both Erythromycin, and Nalidixic acid (Table 3).

Of the twenty Campylobacter species tested, high rate of resistance was observed against Amoxicillin (80%) and Erythromycin (55%). But, relatively low rate of resistance was seen against Ampicillin (30%), Nalidixic acid (20%), and Cotrimoxazole (20%), and there was no resistance detected against Chloramphenicol, and Ceftriaxone (Table 3).

Multiple drug resistance was detected in 19 (95%) of the Campylobacter isolates of which 9 (45%), 4(20%) and 1(5%) showed resistance to three, four and five drugs respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

Diarrhea is among the leading causes of mortality and morbidity in under-five children and continues to be a health problem worldwide, especially in developing countries (19, 20) where enteric bacteria are among the major causes of diarrhea among under-five children (7). The overall prevalence of enteric bacteria isolated in this study (22.2%) is comparable with previous studies conducted in Jimma (22.3%) (9) and Dembia District in Gondar (20.9%) (8). However, the prevalence of bacterial pathogen is lower compared with previous studies conducted in other developing countries such as Tanzania (42.7%) (19) and Mozambique (27.2%) (2).The possible reason for such difference could be the inclusion of diarrheogenic E. coli in these studies.

According to results of related studies, among enteropathogenic bacteria, Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter species and diarrheogenic E. coli were the most frequently isolated bacteria in underfive children with diarrhea (5,17). In line with this, Campylobacter, Shigella and Salmonella species were isolated at the rates of 12.7%, 7% and 2.5% respectively. Comparable bacterial rates of isolates were reported from studies conducted in Jimma (Campylobacter species 11.6%, Shigella species 4.9% and Salmonella species 5.8%) (9), Gondar (Campylobacter species 10.5%, Shigella species 5.2% and Salmonella species 5.2%) (8) and Tikur Anbessa, Ethio-Swedish Children's Hospital (Campylobacter species 13.7%, Shigella species 11.7% and Salmonella species 3.8%) (21).

The rate of Campylobacter infections globally has been increasing with the number of cases often exceeding those of Salmonellosis and Shigellosis (22). High rates of Campylobacter species was reported from children in Jimma (11.6%) (9), Addis Ababa (13.7%) (21), North West Ethiopia (13.8%) (23) and Gondar (10.5%) (8). Generally, Campylobacter isolation rates in developing countries range from 5 to 20% (22), and the isolation rate of Campylobacter species (12.7%) in this study lies within the indicated range and is comparable with locally conducted studies such as the ones in Jimma (9), Addis Ababa (21), and North West Ethiopia (23). In this study, the majority (80%) of the Campylobacter species were isolated from children of less than 24 month of age, which agrees with the report of the World Gastroenterology Organization 2011(7).

The prevalence rate of Shigella species in this study was 7% which is closer to the studies conducted in Jimma by Beyene et al (9), in Gondar by Mitikie et al (8) , in North west Ethiopia by Andualem et al (24) and in Harar, by Reda et al (14), in which the prevalence rates were 5%, 5.2%, 8.7% and 6.7% respectively. But, it is lower than the rate reported in studies carried out at Tikur Anbessa, Ethio-Swedish Children's Hospital by Asrat et al (21), in Jimma by Mache (25), in Hawassa by Roma et al (10), in Indonesia by Herwana et al (26), and in Iran by Mashouf et al (27) where the prevalence rates were 11.7%, 20.1%, 34.5%, 9.3% and 9.8% respectively. The lower isolation rate could be due to difference in study participants and study time.

In this study, Serogroup B (S. flexneri) was the only species (100%) isolated from the study subjects. Its dominance was also reported in the studies by Roma et al (10) in Hawassa, with the isolation rate of 99% and by Asrat D (12) in Addis Ababa where Serogroup B (S. flexneri) was a dominant isolate (54.0%). This feature of S. flexneri was also reported in studies conducted in Indonesia (26), Iran (27) and South India (28). However, contrary to the current study, lower isolation of S. flexneri species (27%) was revealed by a study conducted in Botswana (29).

The overall prevalence of Salmonella species in this study was 2.5%. It is lower than the findings of other similar studies conducted by Mitikie et al in Gondar (5.2%), Beyene et al in Jimma (5.2%), and Asrat et al in Addis Ababa (3.8%) (8, 9, 21). But it is comparable with studies carried out in other developing countries such as Mozambique 2.5 % (1), Tanzania 1.4% (19), Botswana 3% (29) and Palestine 2% (30). Among the four Salmonella isolates, there were 3(1.9%) Serogroup B and 1(0.6%) Serogroup A isolates, which is comparable with the finding of a study reported from Botswana where Serogroup B and Serogroup A were isolated with frequency of 2% and 1% respectively from under five children with diarrhea (29).

Antimicrobial resistance by enteric pathogens is of major concern because of indiscriminate use of drugs (11). In this study, Shigella isolates revealed reasonably high rate of resistance to a number of commonly used antibiotics in Ethiopia such as Amoxicillin (100%), Erythromycin (90.9%), Ampicillin (63.6%), Ceftriaxone (54.5%) and Tetracycline (54.5%).

The development of high resistance of Shigella species against commonly used antibiotics was witnessed by other investigators in different times. In Hawassa, a high rate of resistance of Shigella species to Ampicillin (93%), Erythromycin (90%), Tetracycline (90%) and Cotrimoxazole (56%) was reported by Roma et al 2000 (10). In Gondar, high antibiotic resistance was documented against Ampicillin (79.9%), Tetracycline (86 %), and Cotrimoxazole (73.4%) by Yismaw et al 2006 (13). Asrat reported isolation of Shigella species with a high resistance to Erythromycin (100%), Tetracycline (97.3%), and Ampicillin (78.7%) in Addis Ababa (12). High resistance against Amoxicillin (100%), Ampicillin (100%) and Tetracycline (70.6%) was also reported by Reda et al in Harar (14).

In the current study, all Shigella isolates showed susceptibility to Ciprofloxacin, Nalidixic acid, and Cotrimoxazole. According to the Standard Treatment Guideline for General Health Facilities Treatment of Common Diseases in Ethiopia, Ciprofloxacin is the choice of drug as first line for bacillary dysentery caused by Shigella species and other pathogens. Cotrimoxazole and Ceftriaxone are among the other alternatives (31). Unlike the findings of previous studies, no resistance was observed against Cotrimoxazole, which could be associated with frequent use of this drug in previously reported study areas. Resistance to Cotrimoxazole, Tetracycline, Nalidixic acid and Ampicillin was also reported from South India (28). In this study, the rate of resistance of Shigella species against Gentamicin was 27.3%, which is relatively high compared with resistance rates reported in Hawassa (10), Jimma (25), (12) and Harar (14), all from Ethiopia, where the reported resistance rates were 2%, 1.3%, 0%, and 0% respectively. The possible reason could be the wide utilization of Gentamicin in the study area and frequent exposure of Shigella species to this drug.

Among the four Salmonella isolates, the overall rate of resistance was high for Erythromycin (100%), Ceftriaxone (75%) and Nalidixic acid (25%) which is comparable with the result of Asrat's study, where 100% and 37.8% of the isolates were resistant to Erythromycin and Nalidixic acid respectively (12). Contrary to our findings, high resistance rates of Salmonella species to Ampicillin (81.2%), Tetracycline (75.5%), Gentamicin (75.6%), Chloramphenicol (83.7%) and Amoxicillin (100%) were reported in other parts of Ethiopia (12, 14). This variability could be because of differences in prescription of drug pattern.

Most of the time, in immunocompetent individuals, Campylobacter enteritis is a self-limiting disease and need not to be treated with antimicrobial agents. However, in some patients, Campylobacter may cause severe complications and increase the risk of death, and, therefore, requires treatment (22, 32). In this study, eleven antibiotics were tested against 20 isolates of Campylobacter species. Compared with findings of similar studies conducted in other regions of Ethiopia, this study showed increased resistance against Amoxicillin (80%) and Erythromycin (55%),which are used for treatment of diarrhea due to Campylobacter species (8,9,23). However, the majority of the isolates were sensitive to Tetracycline and Ciprofloxacillin which are considered to be an alternative treatment.

To sum up, in the present study, Campylobacter, Shigella and Salmonella species were isolated at different rates and played a dominant role in causing diarrhea in children of the study area. The overall antibiotic resistance levels against some commonly prescribed drugs were higher than those reported from other regions in Ethiopia, possibly due to the higher levels of exposure and usage of those antimicrobials in the study area.

Therefore, up-to-date information on etiologies and periodic monitoring of the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern is very important for the management of diarrhea in under-five children.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jimma University for its assistance with finance necessary to accomplish this research. We are also grateful to South Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region Health Bureau for their unreserved support.

References

- 1.Mandomando IM, Macete EV, Ruiz J, et al. Etiology of Diarrhea in Children Younger than 5 years of age Admitted in a Rural Hospital of Southern Mozambique. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:522–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vandepitte J, Verhaegen J, Engbaek K, Rohner P, Piot P, Heuck CC. Basic laboratory procedures in clinical bacteriology. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. pp. 1–167. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gascon J, Vargas M, Schellenberg D. Diarrhea in Children under 5 Years of Age from Ifakara, Tanzania: a Case-Control Study. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4459–4462. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.12.4459-4462.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization, author. “A WHO network building capacity to detect, control and prevent food borne and other enteric infections from farm to table”. Laboratory Protocol: WHO; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNICEF/WHO, author. Diarrhea: Why children are still dying and what can be done. The United Nations Children's Fund /World Health Organization report; 2009. pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleary TG. Salmonella. In: Feigin RD, Cherry JD, Demmler GJ, Kaplan SL, editors. Textbook of pediatric infectious diseases. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004. pp. 1473–1487. [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Gastroenterology Organization practice guideline: Acute diarrhea. World Gastroenterology Organization; 2008. [February 2011]. available at www.ngc.org. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mitikie G, Kassu A, Genetu A, Nigussie D. Campylobacter enteritis among children in Dembia district, northwest Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2000;77:654–657. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beyene G, Haile-Amlak A. Antimicrobial sensitivity Pattern of Campylobacter species among children in Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2004;18:185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roma B, worku S, T/Mariam S, Langeland N. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Shigella isolates in Hawassa. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2000;14:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Temu MM, Kaatano GM, Miyaye ND, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Shigella flexneri and S. dysenteriae isolated from stool specimens of patients with bloody diarrhoea in Mwanza, Tanzania. Tanzania Heal Research Bull. 2007;9:186–189. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Asrat D. Shigella and Salmonella serogroups and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns in Ethiopia. East Mediterr Health J. 2008;14:760–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yismaw G, Negeri C, Kassu A. A Five-Year Antimicrobial Resistance Pattern Observed In Shigella Species Isolated From Stool Samples In Gondar University Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2006;20(3):194–198. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reda A, Seyoum B, Yimam J, et al. Antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Salmonella and Shigella isolates in Harar, Eastern Ethiopia. J Infect Dis Immun. 2011;3:134–139. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ethiopia Demographic and health Survey (EDHS), author Central Statistical Agency Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Calverton, Maryland, USA: ORC Macro; 2006. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheesbrough M. Medical laboratory manual for tropical countries. 2nd ed. Vol. 2. UK: Cambridge press; 2006. pp. 38–39. 138. [Google Scholar]

- 17.WHO, author. Basic laboratory procedure in clinical bacteriology. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. pp. 56–69. [Google Scholar]

- 18.CLSI, author. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Twentieth Informational Supplement. 2010;29:1–160. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vargas M, Gascon J, Casals C, et al. Etiology of Diarrhea in Children less than five years of age in Ifakara, Tanzania. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2004;70:536–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mota MI, Gadea MP, Gonzalez S, et al. Bacterial Pathogens Associated with Bloody Diarrhea in Uruguayan Children. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2010;42:114–117. doi: 10.1590/S0325-75412010000200009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asrat D, Hathaway A, Ekwall E. Studies on enteric campylobacteriosis in Tikur Anbessa and Ethio-Swedish children's hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 1999;37:71–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Coker AO, Isokpehi RD, Thomas BN, Amisu KO, Obi CL. Human Campylobacteriosis in Developing Countries. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:237–243. doi: 10.3201/eid0803.010233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gedlu E, Aseffa Campylobacter enteritis among children in north-west Ethiopia: a 1-year prospective study. Ann Trop paediatr. 1996;16:207–212. doi: 10.1080/02724936.1996.11747828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andualem B, Kassu A, Diro E, Moges F, Gedefaw M. The prevalence and Antimicrobial responses of Shigella Isolates in HIV-1 infected and uninfected Adult Diarrhea Patients in North West Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2006;20:99–105. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mache A. Antimicrobial resistance and serogroup of Shigella among pediatric out patient in south west Ethiopia. East Afr Med J. 2001;78:296–299. doi: 10.4314/eamj.v78i6.9022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herwana E, Surjawidjaja JE, Salim oc, et al. Shigella-Associated Diarrhea In Children In South Jakarta, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41:418–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mashouf RY, Moshtaghi AA, Hashemi SH. Epidemiology Of Shigella Species Isolated From Diarrheal Children And Drawing Their Antibiotic Resistance Pattern. Iran J Clinical Infect Disease. 2006;1:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mamatha B, Pusapati BR, Rituparna C. Changing Patterns Of Antimicrobial Susceptibility Of Shigella Serotypes Isolated From Children With Acute Diarrhea In Manipal, South India, A 5 Year Study. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2007;38:863–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Urio EM, Collison EK, Gashe BA, Sebunya T K, Mpuchane S. Shigella and Salmonella strains isolated from children under 5 years in Gaborone, Botswana, and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns. Trop Med Int Health. 2001;6:55–59. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2001.00668.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elamreen FA, Abed AA, Sharif FA. Detection and Identification of Bacterial Enteropathogens by Polymerase chain reaction and Conventional Techniques in Childhood Acute Gastroenteritis in Gaza, Palestine. Int J Infect Dis. 2007;11:501–507. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drug Administration and Control Authority of Ethiopia Contents Standard Treatment Guideline For General Hospitals. DACA; 2010. pp. 46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Engberg J, Neimann J, Moller E, Aarestrup F, Fussing V. Nielsen Quinolone-resistant Campylobacter Infections in Denmark: Risk Factors and Clinical Consequences. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1056–1063. doi: 10.3201/eid1006.030669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]