Abstract

High-frequency, reversible switches in expression of surface antigens, referred to as phase variation (PV), are characteristic of Haemophilus influenzae. PV enables this bacterial species, an obligate commensal and pathogen of the human upper respiratory tract, to adapt to changes in the host environment. Phase-variable hemagglutinating pili are expressed by many H. influenzae isolates. PV involves alterations in the number of 5′ TA repeats located between the −10 and −35 promoter elements of the overlapping, divergently orientated promoters of hifA and hifBCDE, whose products mediate biosynthesis and assembly of pili. Dinucleotide repeat tracts are destabilized by mismatch repair (MMR) mutations in Escherichia coli. The influence of mutations in MMR genes of H. influenzae strain Rd on dinucleotide repeat-mediated PV rates was investigated by using reporter constructs containing 20 5′ AT repeats. Mutations in mutS, mutL, and mutH elevated rates approximately 30-fold, while rates in dam and uvrD mutants were increased 14- and 3-fold, respectively. PV rates of constructs containing 10 to 12 5′ AT repeats were significantly elevated in mutS mutants of H. influenzae strains Rd and Eagan. An intact hif locus was found in 14 and 12% of representative nontypeable H. influenzae isolates associated with either otitis media or carriage, respectively. Nine or more tandem 5′ TA repeats were present in the promoter region. Surprisingly, inactivation of mutS in two serotype b H. influenzae strains did not alter pilin PV rates. Thus, although functionally analogous to the E. coli MMR pathway and active on dinucleotide repeat tracts, defects in H. influenzae MMR do not affect 5′ TA-mediated pilin PV.

Mismatch repair (MMR) constitutes a major defense against the introduction of mutations into DNA-based genomes. The MMR system of the gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli has been extensively studied, and the major pathway of repair by this system is as follows: recognition of a mismatch by MutS; sequential recruitment of MutL and then MutH to the MutS-mismatch complex; tracking of this complex to the nearest 5′ GATC sequence; cleavage by MutH of the unmethylated, and hence newly synthesized, DNA strand in the 5′ GATC site; recruitment of DNA helicase II, encoded by uvrD, and one of four possible exonucleases to the nicked template; DNA unwinding and degradation of one DNA strand from the nick to beyond the mismatch; and then filling and sealing of the gap by DNA polymerase III and DNA ligase (2, 23, 36). Methylation of 5′ GATC sites is performed by an adenine methylase encoded by dam (3). Inactivation of mutSLH increases mutation rates 100- to 1,000-fold, whereas a lesser increase is observed for dam mutants (8, 15). Comparisons of the spectra of spontaneous mutations for wild-type strains and MMR mutants reveal that MMR is active on all types of base substitutions and frameshifts, with the latter occurring most frequently in short tracts of the same base pair (23, 30). Long DNA repeat tracts, termed microsatellites, with unit sizes of 1 or 2 nucleotides are highly unstable in E. coli MMR mutants (24, 31, 33), while the mutation rates of tetranucleotide repeat tracts are unaltered (10).

Haemophilus influenzae is an obligate commensal of the upper respiratory tract of humans that has the potential to cause diseases such as otitis media and meningitis. A characteristic feature of H. influenzae is an ability to switch between genetic variants of alternate phenotypes at high frequencies, which is referred to as phase variation (PV). Only certain “contingency” loci are subject to PV, and most of these loci encode either surface proteins or proteins that modify surface structures (18, 25). The main mechanism of PV for H. influenzae contingency loci involves mutations in long tetranucleotide repeat tracts (4, 17). The H. influenzae strain Rd genome sequence contains homologs (67 to 84% similarity) of all of the known E. coli MMR genes (see The Institute for Genomic Research microbial database at www.tigr.org), indicating that H. influenzae has a fully functional MMR system. Previously, we constructed mutations in five of these genes and observed increases in the generation of nalidixic acid-resistant mutants for mutS, mutL, and mutH mutants but not for dam or uvrD mutants (5). The influence of these mutations on PV rates was also investigated. No increase in PV rate was observed for any of these mutants by using reporter constructs containing tetranucleotide repeats, but an increase was observed with a reporter construct containing 20 5′ AT repeats for a mutS mutant (5). These results provided some limited evidence as to the functional roles of mutS, mutL, and mutH in H. influenzae MMR but were inconclusive with regard to the functionality of dam and uvrD.

Hemagglutination-positive strains of H. influenzae have long, filamentous structures, termed either pili or fimbriae, extending from the bacterial surface (reviewed in reference 14). While these pili are involved in attachment of H. influenzae to epithelial cells, infections in animal models with strains lacking pilus expression have not shown a clear role for these pili in nasopharyngeal colonization or invasive disease. Pilus biosynthesis is encoded by the hif locus, which contains five genes, hifA to -E, whose products are the major structural subunit, a chaperone, a putative assembly platform protein, a minor structural subunit, and a putative adhesin, respectively. Population studies indicate that the hif locus is present in approximately 20% of nontypeable (NT) H. influenzae isolates (12), 49% of encapsulated non-type b H. influenzae isolates (29), and most type b H. influenzae isolates (6). Expression of these hemagglutinating pili is phase variable. PV is due to a 5′ TA repeat tract situated between the −35 and −10 regions of the overlapping and divergent promoters of hifA and the hifBCDE operon (34). This organization was first identified for two serotype b strains, AM20 and AM30. The original isolates of these strains were negative for pilus expression and contained 9 5′ TA repeats in the hif locus promoter, whereas hemagglutination-positive variants expressing pili contained 10 to 12 repeats. Subsequent analyses of this repeat tract in other H. influenzae strains has been limited. Geluk et al. (12) found four and nine TA repeats in one and four NT H. influenzae strains, respectively, while Mhlanga-Mutangadura et al. (22) found four and five 5′ TA repeats in an NT H. influenzae strain and a type f strain, respectively.

In E. coli, MMR is a multigene pathway that guards against the introduction of mutations into the genome and whose inactivation results in significant destabilization of dinucleotide repeat tracts. H. influenzae carries genes with high homology to all components of the E. coli MMR system. We investigated whether these systems were analogous by testing the effects of mutations in five of the major components of the H. influenzae pathway on spontaneous mutation rates and stability of dinucleotide repeat tracts of different lengths. The hif locus is the only proven, or even strong candidate, simple sequence contingency locus in H. influenzae with a repeat unit of less than 4 bp and therefore is likely to be subject to the influence of MMR. We extended the epidemiological observations of the hif locus promoter region to determine whether this locus is always associated with a dinucleotide repeat tract. We also tested the hypothesis that inactivation of MMR in H. influenzae should increase pilin PV rates because they are driven by dinucleotide repeats which are subject to MMR. Our results extend our understanding of the influence exerted by MMR on the generation of genetic diversity in bacterial pathogens and on PV in H. influenzae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

H. influenzae strain RM118, termed Rd here, is a derivative of strain KW20, which was used in the sequencing project (11). Strains with inactivated components of the H. influenzae MMR system, i.e., RdΔmutS, RdΔmutL, RdΔmutH, RdΔdam and RdΔuvrD, were as described previously (5). We also used the type b strains Eagan (1) and R9 (13) and a collection of 42 NT H. influenzae isolates (supplied by J. Eskola and the Finnish Otitis Media Study Group). H. influenzae strains were grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) supplemented either with hemin (10 μg/ml) and NAD (2 μg/ml) for liquid media or with Levinthal supplement for solid media.

Construction of mutS mutants and dinucleotide repeat PV reporter strains.

MMR mutants of strains Eagan and R9 were constructed by transforming competent cells with SalI-linearized DNA of plasmid pUCΔmutS (5) and selecting for transformants on BHI plates containing 4 μg of tetracycline per ml. A mod-5′AT20-lacZ reporter gene was inserted into strains RdΔmutL, RdΔmutH, RdΔdam, RdΔuvrD, Eagan, EaganΔmutS, R9, and R9ΔmutS by transforming these strains with linearized DNA of plasmid pGΔZ-AT20R (5). A mod-5′AT10-lacZ reporter plasmid, pGΔZ-AT10R, was constructed as described previously for the 5′ AT20 reporter construct by using a primer A with only 10 5′ AT repeats (5). This reporter gene was inserted into strains Rd, RdΔmutS, Eagan, and EaganΔmutS by transformation with ScaI-linearized plasmid DNA and selection on BHI plates containing 10 μg of kanamycin per ml.

Assay of spontaneous mutation rate.

H. influenzae strain Rd or mutant strains were grown to mid-log phase in liquid medium. The cell number was estimated by measuring the optical density at 490 nm and assuming that an optical density at 490 nm of 1 is equal to 5 × 107 cells/ml. Inocula of either 500 to 1,000 cells or 5,000 to 12,000 cells were prepared and added to 10 tubes containing 3 ml of BHI. These cultures were incubated overnight and then plated on BHI plates containing 5 μg of rifampin per ml to estimate the number of rifampin-resistant (Rifr) variants in each culture. Dilutions of some cultures were also plated on BHI plates without antibiotic to estimate the total numbers of cells in the overnight cultures. A 10-fold excess of each inoculum was plated on BHI plates containing 5 μg of rifampin per ml. No colonies were detected, indicating that there were no preexisting Rifr variants in any of the inocula. The median frequency (number of Rifr variants divided by total number of cells) for the 10 cultures was used to estimate the mutation rate (9). An identical protocol was used for strains R9 and R9ΔmutS, except that a higher inoculum (6 × 104 to 8 × 104 cells) had to be used to obtain growth in broth culture.

Spontaneous mutation rates for strain Eagan and EaganΔmutS were estimated as described previously (5), except that cultures were plated on BHI plates containing 5 μg of rifampin per ml.

Assays of PV rate.

PV rates and alterations in the repeat tracts for the dinucleotide reporter constructs and pilin were determined as described previously (5). Briefly, PV frequencies of reporter constructs were determined for colonies grown on BHI plates containing Levinthal supplement and 40 μg of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoyl-β-d galactopyranoside) per ml by plating serial dilutions on identical plates and using these serial dilutions to determine the total numbers of cells and phase variants in a colony. PV frequencies for pilin were determined for colonies grown on BHI plates containing Levinthal supplement by plating serial dilutions, transferring these colonies to nitrocellulose filters, and probing the filters with R38, an antipilin polyclonal antiserum, to detect phase variants. The frequency is then the number of variants divided by the number of cells. Multiple colonies (see table footnotes) were analyzed for each construct to generate a median frequency from which a mutation rate was derived as described by Drake (9). Alterations in repeat tracts were determined by PCR amplification of the repeat tracts from parental and variant colonies by using fluorescent primers spanning the relevant region and then sizing these PCR products by electrophoretic analysis with an ABI Prism 377 and the ABI GeneScan 3.1 program (Perkin-Elmer). Statistical analyses of PV frequencies were performed with the program Instat 2.0.

Analysis of the purE-pepN locus and the hif promoter.

PCR analysis was performed on either genomic DNA preparations or boiled lysates of H. influenzae isolates. The purE-pepN region was amplified with primers PURE (5′-TTGGAACCCATTACAACGGC-3′) and PEPN (5′-CTGTGACCGTAAAATCTGGTTG-3′), while the hif promoter region was amplified with primers MH006 (5′-CCTGTGAACGTAATCCGCAAAC-3′), located internal to hifB, and AREP2 (5′-AACAGCAAGATTTGTTTTCC-3′), located on the other side of the promoter (these primers are identical to or variants of primers described elsewhere [12, 34]). Isolates for which no products were generated with PURE and PEPN were then subject to amplification with PURE and MH006, MH006REV (5′-GTTTGCGGATTACGTTCACAGG-3′) and HIFCREV (5′-GTGCATTATCCAAATCAAC-3′) (located at the 3′ end of hifC), and HIFCFOR (5′-GTTGATTTGGATAATGCAC) and PEPN. PCR fragments were sequenced directly by using dye terminator chemistry (ABI Big-Dyes) and run on an ABI Prism 377 sequencer. Sequencing reactions were performed with the PCR primers and, for the hif promoter, an internal primer, NTPILSEQ (5′-CAATGCCTCGTGTTGTAAGG-3′). DNA sequences were analyzed by using the CLUSTAL program (16) and GeneDoc version 2.6.001 (K. B. Nicholas and H. B. J. Nicholas, 1997; distributed by the authors).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers for the sequences presented here are as follows: strain 16, AJ606954; strain 162, AJ608804; strain 176, AJ608797; strain 264, AJ606953; strain 285, AJ608798; strain 375, AJ608800; strain 486, AJ608802; strain 1008, AJ606949; strain 1207, AJ606952; strain 1209, AJ606950; strain 1231, AJ608803; strain 1233, AJ606951; strain 1247, AJ608799; strain 1292, AJ608801; and strain Eagan, AJ606955.

RESULTS

Spontaneous mutation rates of H. influenzae MMR mutants.

The spontaneous mutation rates of H. influenzae MMR mutants were previously assessed by using frequencies of generation of nalidixic acid-resistant variants (5). Significant increases in the mutation rate relative to that of strain Rd, the parental strain, were observed for mutS, mutL, or mutH mutants but not for uvrD or dam mutants, suggesting that the products of the last two genes may not be involved in the H. influenzae MMR pathway. Observed spontaneous mutation rates differ, however, depending on the resistance phenotype that is examined (15). The spontaneous mutation rates of these mutants for rifampin resistance were examined. Approximately 12-fold increases in the mutation rate were observed for H. influenzae mutS and mutH mutants (Table 1), which is in line with previous results for nalidixic acid resistance (5). In contrast, only a 5-fold increase in the mutation rate for rifampin resistance was observed for the mutL mutant (Table 1), whereas for nalidixic acid resistance the increase in rate was similar to those of mutS and mutH mutants. The RdΔuvrD and RdΔdam mutants exhibited, respectively, 2.1- and 2.6-fold increases in the mutation rate for rifampin resistance relative to strain Rd (Table 1). The 95% confidence intervals (CI) do not overlap for comparisons of mutation rates to rifampin resistance for RdΔmutS, RdΔmutL, RdΔmutH, and RdΔdam with strain Rd but do overlap for Rd and RdΔuvrD (Table 1), indicating significance in the former but not the latter cases. However, a Mann-Whitney (nonparametric) rank sum test yielded a P value of 0.0007 for a comparison of the Rd and RdΔuvrD mutation frequencies. We conclude that H. influenzae spontaneous mutation rates are significantly increased by inactivation of mutS, mutL, mutH, dam, or uvrD.

TABLE 1.

Spontaneous mutation rates of H. influenzae MMR mutant strains

| Strain | Rifampin resistance

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation rate (10−9)a | 95% CI (10−9)b | Fold increase over wild-type value | |

| Rd (wild type) | 0.9 | 0.48-1.47 | 1.0 |

| RdΔmutS | 10.49 | 8.07-12.22 | 11.6 |

| RdΔmutL | 4.1 | 3.36-5.07 | 4.5 |

| RdΔmutH | 11.99 | 11.05-13.93 | 13.2 |

| RdΔdam | 2.39 | 1.78-3.96 | 2.6 |

| RdΔuvrD | 1.87 | 1.38-3.52 | 2.1 |

| Eagan (wild type) | 0.62 | 0.42-1.10 | 1.0 |

| EaganΔmutS.1 | 5.98 | 4.79-6.67 | 9.6 |

| EaganΔmutS.2.1 | 5.13 | 4.85-7.45 | 8.3 |

| R9 (wild type) | 0.34 | 0.30-1.37 | 1.0 |

| R9ΔmutS | 4.85 | 2.75-6.93 | 14.3 |

Destabilization of long dinucleotide repeat tracts by inactivation of H. influenzae MMR.

Dinucleotide repeat tracts are destabilized by inactivation of any of the nonredundant major components of the E. coli MMR system (24, 31). Previously, using a chromosomally located mod-AT20R-lacZ reporter gene, we showed that inactivation of H. influenzae mutS destabilized a tract of 20 5′ AT dinucleotide repeats (5). This analysis was extended to other putative components of the H. influenzae MMR system. Inactivation of mutL or mutH destabilized the 5′ AT20 repeat tract to a similar extent as mutS inactivation did (Table 2), suggesting that all MMR of these repeat tracts proceeds through the mutSLH pathway. In an H. influenzae dam mutant, RdΔdam, rates were twofold lower than in H. influenzae mutSLH mutants (Table 2). A Mann-Whitney (nonparametric) rank sum test yielded P values of <0.002 for comparisons of the PV frequencies of these strains, indicating that the twofold difference is highly significant. Finally, the rates for an H. influenzae uvrD mutant, RdΔuvrD, were elevated only threefold over those of reporter constructs in strain Rd and, as indicated by the nonoverlapping 95% CI, were significantly lower than those observed in the H. influenzae mutSLH or dam mutants (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Mutation rates of 5′ AT repeat tracts in H. influenzae MMR mutant strains

| Strain | On-to-off switching

|

Off-to-on switching

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of repeats | Median frequency (10−3) | Mutation rate (10−4)a | No. of repeats | Median frequency (10−3) | Mutation rate (10−4) | |

| Rd (wild type) | 20 | 1.79 | 1.89b (1.08-2.25) [1.0] | 22 | 1.27 | 1.39b (1.06-1.78) [1.0] |

| RdΔmutS | 20 | 65.8 | 51.82b (47.0-52.5) [27.4] | 19 | 30.25 | 24.20b (19.9-29.8) [17.4] |

| RdΔmutL | 20 | 73.85 | 58.12 (52.3-73.0) [30.8] | 19 | 35.7 | 29.04 (24.7-35.2) [20.9] |

| RdΔmutH | 20 | 69.0 | 54.29 (40.3-61.6) [28.7] | 21 | 49.0 | 38.8 (32.5-46.7) [27.9] |

| 19 | 31.7 | 26.08 (16.3-42.5) [18.8] | ||||

| RdΔdam | 20 | 31.62 | 27.14 (19.5-39.3) [14.4] | 21 | 18.9 | 17.75 (15.5-47.6) [12.8] |

| 19 | 11.0 | 10.22 (7.46-34.2) [7.4] | ||||

| RdΔuvrD | 20 | 6.42 | 6.32 (5.31-8.79) [3.3] | 22 | 3.49 | 3.44 (2.29-4.71) [2.5] |

| 19 | 2.13 | 2.25 (1.77-3.26) [1.6] | ||||

| Rd (wild type) | 11 | 0.05 | 0.08 (0.07-0.13) [1.0] | 10 | 0.03 | 0.05 (0.03-0.06) [1.0] |

| RdΔmutS | 11 | 3.94 | 4.00 (3.47-6.73) [48.2] | 12 | 5.14 | 4.59 (3.12-5.3) [97.7] |

| 10 | 1.95 | 2.11 (1.57-4.14) [44.9] | ||||

| Eagan | 20 | 1.52 | 1.69 (0.79-6.11) [1.0] | 10 | 0.06 | 0.1 (0.08-0.14) [1.0] |

| EagΔmutS | 20 | 73.9 | 59.0 (47.1-70.2) [34.9] | 10 | 1.23 | 1.31 (1.16-5.62) [13.1] |

| R9 | 20 | 1.84 | 2.07 (1.17-3.18) [1.0] | |||

| R9ΔmutS | 20 | 67.83 | 54.68 (44.7-79.2) [26.4] | |||

Mutation rates were derived from the median frequency by the method of Drake (9). Median frequencies were determined from the analysis of at least 16 colonies for on-to-off switching and at least 8 colonies for off-to-on switching. Numbers in parentheses are 95% CI calculated as described previously (20). Numbers in brackets are fold increases relative to the parental wild-type rates, which were calculated by using strains with similar repeat numbers and directions of switching.

Values as reported previously (5).

The spectra of mutations in the 5′ AT20 repeat tracts were examined by PCR amplification of repeat tracts from variant colonies and either sequencing or size analysis of the products (5). The results are presented in Fig. 1. It should be noted that for on-to-off switching all one- and two-repeat-unit shifts result in loss of gene expression, while for off-to-on switching only certain reading frames can produce a Mod-LacZ fusion protein (e.g., AT19 switches to AT17 [−2 repeats] or AT20 [+1 repeat]). Constructs in strain Rd were previously shown to generate a large number of two-repeat-unit shifts (64%) in 5′ AT20 repeat tracts, while RdΔmutS mutants produced only one-repeat-unit shifts (5). Figure 1 shows that RdΔmutL, RdΔmutH, and RdΔdam generate few two-repeat-unit shifts (0, 22, and 8%, respectively). In contrast, 36% of mutations in the 5′ AT20 tracts of uvrD mutants are deletions or insertions of two repeat units. A similar trend is seen for off-to-on switching, with <7% of alterations being by two repeat units in RdΔmutS, RdΔmutL, RdΔmutH, or RdΔdam, while for RdΔuvrD and strain Rd the values are 21 to 47% and 60%, respectively. These results provide a further indication that MMR is still partially active in an H. influenzae uvrD mutant, resulting in the correction of many, but fewer than in strain Rd, single-repeat-unit insertions or deletions.

FIG. 1.

Mutational spectra of dinucleotide repeat tracts in mod-lacZ reporter genes of H. influenzae MMR mutants. Changes in repeat number for 5′ AT tracts of phase-variant colonies were classified as either insertions or deletions of particular numbers of repeat units. The numbers of variants in each class were expressed as the percentage of the total number examined. The relevant genotype, repeat tract number of parental colonies (parentheses), and number of variants examined (braces) are recorded below each column. (A) On-to-off switching. (B) Off-to-on switching in which either +1/−2 (bars 1 to 9) or −1/+2 (bars 10 to 12) reading frames produce a Mod-LacZ fusion protein. Data for mod-5′AT-lacZ reporter genes containing 20 and 22 repeats in strain Rd (wild type [wt]) and 20 and 19 repeats in RdΔmutS were published previously (5).

Destabilization of a 5′ AT10 repeat tract by inactivation of H. influenzae mutS.

The hif locus in H. influenzae strains AM20 and AM30 contains nine 5′ TA repeats (34). The mutation rates of dinucleotide repeat tracts of a similar length and sequence were investigated by constructing a mod-lacZ reporter gene carrying 10 5′ AT repeats and inserting this construct into H. influenzae strain Rd and RdΔmutS. ON variants containing 11 5′ AT repeats were isolated from these reporter strains. PV rates were measured for both directions of switching. PV rates in strain Rd were at the limits of detection, with between 1 and 4 variant colonies being detected per 104 colonies (Table 2). Switching rates in the mutS mutants were readily measurable and were 45- to 48-fold higher than those in strain Rd (Table 2), an increase that is higher than the 27-fold difference observed between these two strains for 5′ AT20 reporter constructs.

Figure 1 shows the mutational spectra obtained with the 5′ AT11 and 5′ AT10 reporter genes. For on-to-off switching in strain Rd, a 1.3:1 ratio of one- to two-repeat-unit shifts was obtained for the 5′ AT11 constructs, which is higher than the 1:2.5 ratio observed with the 5′ AT20 reporter constructs (5). Similarly, for off-to-on switching in strain Rd, the ratios with the 5′ AT10 and 5′ AT22 constructs were 3.2:1 and 1:1.5, respectively. The lower incidence of two-repeat-unit shifts in the 5′ AT10 and 5′ AT11 repeat tracts indicates that loops consisting of two repeat units are less readily formed in these repeat tracts than in those consisting of 20 or 22 5′ AT repeats, resulting in a higher proportion of the mutations in the shorter repeat tracts being due to one-repeat-unit shifts. In the mutS mutant, all of the mutations in 5′ AT10, AT11, or AT12 repeat tracts are due to one-repeat-unit shifts (Fig. 1). The greater effect of a mutS mutation on PV rates mediated by 11 5′ AT repeats as opposed to 20 5′ AT repeats may be due to a higher proportional effect of the increase in one-repeat-unit shifts in the shorter repeat tracts.

Sequence similarities and differences in dinucleotide repeat tracts and flanking sequences of the region mediating H. influenzae pilin PV.

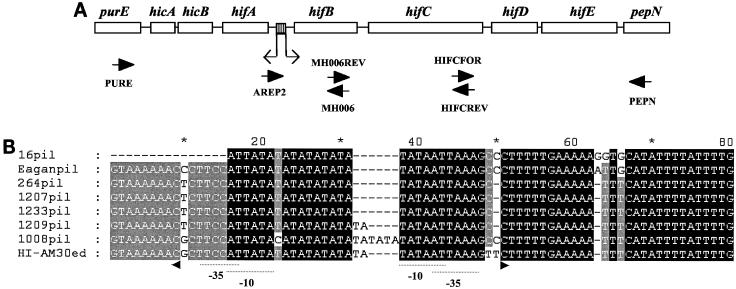

Analysis of repeat number for the hif locus promoter has been limited to a small number of H. influenzae isolates of unknown relatedness. We extended these analyses by investigating the hif locus in 42 NT H. influenzae isolates (25 otitis media isolates and 17 carriage isolates) which were selected to represent the diversity of H. influenzae based upon a dendrogram constructed after ribotyping of >400 H. influenzae strains (7). In strain AM30 the hif locus is composed of a contiguous DNA sequence of 6.8 kbp (35), and in all isolates of H. influenzae analyzed to date this locus is located between purE and pepN (12, 22, 27). The region between purE and pepN was amplified by PCR from genomic DNAs of the 25 otitis media isolates by using primers that bind within the coding sequences of these genes (Fig. 2A). Products indicative of the presence of all five hif genes were obtained with 4 of the 25 otitis media isolates and 2 of the 17 carriage isolates (Table 3). Two of the otitis media isolates (1207 and 1209) were isolated from different ears of the same patient on the same day and are identical by ribotyping and multilocus sequence typing (7). Thus, an intact hif locus was present in 14% (3 of 21 [i.e., not including same-patient, same-day isolates] [7]) of otitis media isolates and in 12% (2 of 17) of carriage isolates.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of the organization and promoter sequences of the hif loci of NT H. influenzae strains. (A) Representation of the hif locus of H. influenzae strain Eagan. Genes are represented by open boxes and are named. The shaded box represents the dinucleotide repeat tract. Thin arrows indicate the transcriptional orientations of the divergent hifA and hifBCDE promoters. Thick arrows indicate the primers used for PCR analysis of the hif locus. The positions of hicA and hicB were reported previously (27). (B) Alignment of the nucleotide sequences of the hif locus promoter regions from different strains. Dashes indicate nucleotides that are not present in a sequence. The transcription initiation codons (+1) and promoter elements (−10 and −35) of hifA and hifBCDE are marked by small arrowheads and dashed lines, respectively (positions are as described previously [34]). Sequence HI-AM30ed (accession number Z33502) is that of H. influenzae strain AM30 (35).

TABLE 3.

Analysis of NT H. influenzae strains for presence of the hif locus between purE and pepN

| Size of insert between purE and pepN (kbp) | Presence of hif promoter or hif genesa | Isolates

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Otitis media | Carriage | ||

| 0.3 | − | 486b | 609 |

| 0.5 | − | 1231b, 1232 | |

| 0.9 | − | 176b, 375b, 432, 477, 723, 981, 1124, 1158, 1159, 1247b | 88, 177, 492, 709, 805, 968 |

| 1.1 | − | 162b, 667, 1180, 1181, 1292b | 17, 443, 525 |

| 1.2 | − | 285b, 1200, 1248 | 24 |

| 2.7 | (+) | 11 | |

| 4.0 | − | 794, 425, 540 | |

| 6.7 | + | 1207, 1209, 1233 | 264 |

| 7.2 | + | 1008 | 16 |

+, PCR products were obtained with AREP2 and MH006 (spanning the hif locus promoter region and hifB) and primers that bind within hifC; (+), products were obtained with AREP2 and MH006 but not hifC primers; −, no products were obtained with AREP2 and MH006.

The PURE-PEPN PCR products from this strain were sequenced in their entirety; these sequences contained either no genes (486 and 1231) or two genes, hicA and hicB (22), of unknown function but no hif genes.

The promoter regions from isolates containing the hif locus were amplified by PCR, sequenced, and compared to the sequences derived from strains Eagan and AM30 (Fig. 2B). Isolates 16, 264, 1207, and 1233 have 9 5′ TA repeats while isolate 1209 has 10, with the latter repeat number being associated in strain AM30 with a high level of pilus expression. Surprisingly, isolate 1008 has an interrupted repeat tract (2 5′ TA repeats, 1 5′ CA repeat, and 9 5′ TA repeats) that is equivalent in length to 12 5′ TA repeats. In conclusion, the hif locus promoter in this representative population of H. influenzae isolates is consistently associated with nine or more 5′ TA repeats.

Pilus PV rates in MMR mutants of H. influenzae strains.

As 5′ TA repeats are invariantly present in the hif promoter and MMR mutations destabilize 5′ AT tracts in H. influenzae strain Rd, we investigated whether H. influenzae pilus PV rates were elevated in MMR mutants. A pilin-specific antiserum that was reactive with strain Eagan but not with the hif locus-positive otitis media isolates described above was obtained (data not shown). The influence of MMR mutations on pilin PV rates was therefore pursued by using strain Eagan. A mutS mutation was inserted into strain Eagan by transforming this strain with pUCΔmutS-tet. These mutants exhibited 8- to 10-fold increases in the generation of rifampin-resistant variants (Table 1) and 35- and 14-fold increases in switching rates for the mod-5′AT20-lacZ and mod-5′AT10-lacZ reporter constructs, respectively (Table 2), indicating that inactivation of MMR in strain Eagan increases both point and dinucleotide repeat mutation rates. PV rates of pili were therefore assessed in these mutants by using the pilus-specific R38 antiserum. Rates for off-to-on switching were determined (Table 4), and although the rates for the mutants were 1.6-fold higher than those for strain Eagan, this difference was not significant as indicated by the overlapping 95% CI and by a Mann-Whitney (nonparametric) rank sum test, which yielded a P value of 0.6 for comparisons between the PV frequencies of these strains. Eight and 12 on variants of EaganΔmutS0.1 and strain Eagan, respectively, were isolated. Nineteen of these variants contained 10 5′ TA repeats in the hif promoter (data not shown), while one variant of strain Eagan contained 11 5′ TA repeats. PV rates were investigated for three ON variant colonies of strain Eagan and of EagΔmutS.1. For both strains the rates were low and difficult to accurately quantify; there was, however, no discernible increase in the number of variants in the MMR mutant strain.

TABLE 4.

H. influenzae pilin PV rates

| Straina | Off-to-on switching

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of 5′ TA repeats | Median frequency (10−4) | Mutation rate (10−5)b | Fold increasec | |

| Eagan | 9 | 1.3 | 1.75 (1.32-4.66) | 1.0 |

| EaganΔmutS.1 | 9 | 2.32 | 2.91 (0.7-6.53) | 1.7 |

| EaganΔmutS.2.1 | 9 | 2.31 | 2.87 (1.58-4.28) | 1.6 |

| R9 | 9 | 1.53 | 1.93 (4.43-1.0) | 1.0 |

| R9ΔmutS | 9 | 2.15 | 2.64 (5.94-1.32) | 1.4 |

EaganΔmutS.1 and EaganΔmutS.2 are two independent transformants isolated following transformation of strain Eagan with pUCΔmutS (5).

Mutation rates were derived from the median frequency by the method of Drake (9). Median frequencies were determined from the analysis of at least 10 colonies. Numbers in parentheses are 95% CI calculated as described previously (20).

Calculated by dividing the mutation rate of each strain by the mutation rate for the relevant parental strain (Eagan or R9).

In order to establish whether the absence of an effect of MMR inactivation on pilus switching was specific to strain Eagan or was a more general phenomenon, we performed similar experiments with strain R9, another serotype b H. influenzae strain (13). A mutS mutation was constructed in this strain, and this mutation increased rates of spontaneous mutation to rifampin resistance (Table 1) and PV rates for the mod-5′AT20-lacZ construct (Table 2). Rates of off-to-on switching for the pilus were then determined by using the R38 antiserum (Table 4). The pilus PV rates for R9ΔmutS were increased 1.4-fold relative to those for strain R9. The overlapping 95% CI and P value of 0.4 (from a Mann-Whitney [nonparametric] rank sum test) indicate that these values are not significantly different. This result provides further evidence that inactivation of MMR in H. influenzae does not significantly elevate pilus PV rates.

DISCUSSION

MMR provides a major defense against the introduction of mutations into the genomes of many prokaryotic and all eukaryotic organisms, and it has been proposed that the increase in mutation rates associated with MMR mutations can contribute to cancer (19) and to a higher rate of adaptation for prokaryotes under stringent selection (e.g., persistence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in some cystic fibrosis patients [26]). Significantly, mono- and dinucleotide repeat tracts, which are responsible for PV of multiple virulence determinants in some bacterial species, are highly unstable in MMR mutants. Destabilization of such tracts may be responsible for the prevalence of MMR mutants among epidemic serotype A strains of Neisseria meningitidis (28). Despite these important dual roles in genome maintenance and generation of genetic diversity, detailed studies of the MMR pathway have not been performed with many bacterial species. We demonstrate that the H. influenzae and E. coli MMR pathways are analogous and that a dinucleotide repeat tract is highly unstable in H. influenzae MMR mutants. We also show that the promoter associated with PV of H. influenzae pili contains a dinucleotide repeat tract of nine or more 5′ TA repeats in strains representative of the diversity of this species. Surprisingly, we observe that the pilus PV rate is not elevated in mutS mutants of two serotype b H. influenzae strains.

Inactivation of the H. influenzae mutS, mutL, or mutH homologs increased rates of spontaneous mutation to nalidixic acid resistance 3- to 4-fold (5) and to rifampin resistance 5- to 13-fold (Table 1), while a 5′ AT dinucleotide repeat tract was destabilized by similar amounts, 27- to 31-fold (Table 2), in each of these mutants. The similar effects of these three mutations in each assay indicate that these proteins function in the same pathway. Notably, a 5′ AT dinucleotide repeat tract was destabilized 14-fold (Table 2) in a H. influenzae dam mutant, an increase which is twofold lower than that observed with a mutS mutant. This differential in dinucleotide mutation rates fits with a loss of strand discrimination resulting in the template and newly synthesized strands being repaired at equal rates during MutSLH-directed repair events. The lower observed effect on spontaneous mutation rates (5) (Table 1) may be due to lethal effects of dam inactivation (21), resulting in a reduced recovery of mutants on selective antibiotic-containing media. Furthermore, we have observed that genomic DNA of an H. influenzae dam mutant is sensitive to restriction by MboI but resistant to restriction by DpnI, whereas strain Rd DNA has the opposite phenotype (data not shown). This result indicates that the H. influenzae Dam protein methylates 5′ GATC sequences such that the H. influenzae and E. coli MMR strand discrimination pathways are mechanistically similar. Finally, inactivation of H. influenzae uvrD increased rates of spontaneous mutation to rifampin resistance twofold (Table 1) and destabilized 5′ AT repeat tracts approximately threefold (Table 2). This small effect relative to inactivation of mutSLH suggests either that DNA helicase II, the putative product of H. influenzae uvrD, is not essential for all MMR events or that there is reduced recovery of mutants due to a detrimental effect of uvrD inactivation. In conclusion, H. influenzae MMR appears to be functionally analogous to E. coli MMR involving MutS, MutL, and MutH in a common pathway that requires Dam for strand discrimination but differs in having only a limited role for DNA helicase II.

Pili, encoded by the hif locus, are the only H. influenzae structures whose PV has been shown to be dependent on a simple sequence repeat of fewer than four nucleotides. We examined the occurrence and repeats of the hif locus in populations of genetically distinct NT H. influenzae isolates associated with either otitis media or carriage. Similar frequencies of occurrence of the hif locus were observed for otitis media and carriage isolates (14 and 12%, respectively), suggesting that the presence of this locus does not influence, either positively or negatively, the ability of H. influenzae to cause otitis media. An intact hif locus was found in six isolates, and the hif locus promoter in each of these isolates contained 5′ TA repeats (Fig. 2B). A number of polymorphisms were apparent in these sequences, but none of these alterations changed the −10 and −35 promoter elements or the transcription initiation site. Intriguingly, alterations in the repeat tract were observed. First, the tracts of isolates 1207 and 1209 contained 9 and 10 5′ TA repeats, respectively. These isolates were obtained from different ears of the same patient on the same day and have identical multilocus sequence types (7), suggesting that they are different isolates of the same strain. As 9 and 10 repeats are, respectively, associated with low and high levels of expression in strain AM30 (34), this result suggests that there was a PV-dependent alteration in pilin expression in this patient, but whether this PV event involved selection (e.g., inflammation in the middle ear) or some other process is unclear. Second, isolate 1008 has an interrupted repeat tract equivalent in length to 12 5′ TA repeats, which is associated with a low level of pilus expression in other strains (34). As interruptions in repeat tracts are known to reduce mutation rates relative to pure tracts of equivalent length (31), the pilus PV rate in isolate 1008 may be similar to those in strains containing 10 5′ TA repeats in the promoter of the hif locus.

H. influenzae MMR mutations destabilize dinucleotide (Table 2) but not tetranucleotide repeat tracts in reporter constructs (5). As the hif locus-encoded pilus is the only H. influenzae determinant whose PV is known to be controlled by repeat units of fewer than four nucleotides, we investigated the influence of an MMR mutation on pilin PV rates. Mutation of mutS in either strain Eagan or strain R9 (Table 4) did not increase these rates. This effect was not due to the short length of the repeat tract in the hif locus, as repeat tracts of similar length (10 to 12 5′ AT repeats) and sequence in the reporter construct were destabilized by mutS mutations in strains Rd and Eagan (Table 2). Furthermore, the mutS mutations in strains Eagan and R9 increased spontaneous mutation rates and destabilized tracts of 20 5′ AT repeats in reporter constructs, indicating that MMR had been inactivated by the mutS mutation in both of these strains. One possibility is that slippage mutations in the hif locus repeat tract are not subject to MMR correction or that MMR repair is reduced in this locus. A second possibility is that hairpins formed in the REP sequences (35), strain Eagan has a complete copy of REPh (data not shown), or other sequences in this region stimulate MMR-initiated DNA synthesis across the hif promoter, resulting in additional mutations being generated in the 5′ TA repeat tract. It should also be noted that slippage mutations generated during MMR-initiated DNA synthesis can be repaired but that this repair is likely to occur in a mutagenic fashion due to the loss of strand discrimination, which is lost because 5′ GATC sites are fully methylated, a process that is completed soon after replicative DNA synthesis (32). In this scenario, loss of MMR would result in both an increase (due to a reduction in correction) and a decrease (due to a reduction in MMR-initiated DNA synthesis) in the number of slippage mutations in the 5′ TA repeat tract such that no apparent elevation of pilus PV rate would be observed. A third possibility is that slippage mutations in the hif locus repeat tract are corrected by a non-MMR pathway. Analysis of the effects of MMR mutations in other strains and genetically altered versions of the hif locus will be required to distinguish between these hypotheses.

In conclusion, the H. influenzae MMR pathway has functional identity with the E. coli MMR pathway, and inactivation of this pathway can destabilize a dinucleotide repeat tract in a reporter construct but not a native locus. This further evidence of the refractoriness of H. influenzae simple sequence repeat-mediated PV to MMR mutations contrasts with the intimate interplay between MMR and phase-variable switching observed for other bacterial species (e.g., N. meningitidis) using this mechanism of adaptation.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Janet Gilsdorf and Kirk McCrea for the provision of an antipilin antiserum and of strain R9. We also thank Juhani Eskola and all members of the Finnish Otitis Media Study Group at the National Public Health Institute in Finland for the provision of NT H. influenzae strains and Ali Cody and others for preparation of DNAs from these strains. We thank Saba Ghori for technical assistance with construction of reporter strains and Derek Hood for critical reading of the manuscript.

C.D.B. and W.A.S. were funded by a Wellcome Trust program grant.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson, P., R. Johnston, and D. Smith. 1972. Human serum activities against Haemophilus influenzae, type b. J. Clin. Investig. 51:31-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Au, K. G., K. Welsh, and P. Modrich. 1992. Initiation of methyl-directed mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem. 267:12142-12148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barras, F., and M. G. Marinus. 1989. The great GATC: DNA methylation in E. coli. Trends Genet. 5:139-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayliss, C. D., D. Field, and E. R. Moxon. 2001. The simple sequence contingency loci of Haemophilus influenzae and Neisseria meningitidis. J. Clin. Investig. 107:657-662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayliss, C. D., T. van de Ven, and E. R. Moxon. 2002. Mutations in polI but not mutSLH destabilize Haemophilus influenzae tetranucleotide repeats. EMBO J. 21:1465-1476. (Erratum, 21:4391.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemens, D. L., C. F. Marrs, M. Patel, M. Duncan, and J. R. Gilsdorf. 1998. Comparative analysis of Haemophilus influenzae hifA (pilin) genes. Infect. Immun. 66:656-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cody, A. J., D. Field, E. J. Feil, S. Stringer, M. E. Deadman, A. G. Tsolaki, B. Gratz, V. Bouchet, R. Goldstein, D. W. Hood, and E. R. Moxon. 2003. High rates of recombination in otitis media isolates of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Gen. Evol. 3:57-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cox, E. C. 1976. Bacterial mutator genes and the control of spontaneous mutation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 10:135-156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Drake, J. W. 1991. A constant rate of spontaneous mutation in DNA-based microbes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88:7160-7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eckert, K. A., and G. Yan. 2000. Mutational analyses of dinucleotide and tetranucleotide microsatellites in Escherichia coli: influence of sequence on expansion mutagenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:2831-2838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleischmann, R. D., M. D. Adams, O. White, R. A. Clayton, E. Kirkness, A. Kerlavage, C. Bult, J. Tomb, B. Dougherty, and J. Merrick. 1995. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science 269:496-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geluk, F., P. P. Eijk, S. M. van Ham, H. M. Jansen, and L. van Alphen. 1998. The fimbria gene cluster of nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 66:40-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilsdorf, J. R., K. W. McCrea, and L. J. Forney. 1990. Conserved and nonconserved epitopes among Haemophilus influenzae type b pili. Infect. Immun. 58:2252-2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilsdorf, J. R., K. W. McCrea, and C. F. Marrs. 1997. Role of pili in Haemophilus influenzae adherence and colonization. Infect. Immun. 65:2997-3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glickman, B. W., and M. Radman. 1980. Escherichia coli mutator mutants deficient in methylation-instructed DNA mismatch correction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77:1063-1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins, D. G., and P. M. Sharp. 1988. CLUSTAL: a package for performing multiple sequence alignment on a microcomputer. Gene 73:237-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hood, D. W., M. E. Deadman, M. P. Jennings, M. Bisercic, R. D. Fleischmann, J. C. Venter, and E. R. Moxon. 1996. DNA repeats identify novel virulence genes in Haemophilus influenzae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11121-11125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hood, D. W., and E. R. Moxon. 1999. Lipopolysaccharide phase variation in Haemophilus and Neisseria, p. 39-54. In H. Brude, S. M. Opal, S. N. Vogel, and D. C. Morrison (ed.), Endotoxin in health and disease. Marcel Dekker Inc., New York, N.Y.

- 19.Karran, P., and M. Bignami. 1994. DNA damage tolerance, mismatch repair and genome instability. Bioessays 16:833-839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kokoska, R. J., L. Stefanovic, H. T. Tran, M. A. Resnick, D. A. Gordenin, and T. D. Petes. 1998. Destabilization of yeast micro- and minisatellite DNA sequences by mutations affecting a nuclease involved in Okazaki fragment processing (rad27) and DNA polymerase delta (pol3-t). Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:2779-2788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marinus, M. G. 2000. Recombination is essential for viability of an Escherichia coli dam (DNA adenine methyltransferase) mutant. J. Bacteriol. 182:463-468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mhlanga-Mutangadura, T., G. Morlin, A. L. Smith, A. Eisenstark, and M. Golomb. 1998. Evolution of the major pilus gene cluster of Haemophilus influenzae. J. Bacteriol. 180:4693-4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Modrich, P. 1987. DNA mismatch correction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56:435-466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morel, P., C. Reverdy, B. Michel, S. D. Ehrlich, and E. Cassuto. 1998. The role of SOS and flap processing in microsatellite instability in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:10003-10008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moxon, E. R., P. B. Rainey, M. A. Nowak, and R. Lenski. 1994. Adaptive evolution of highly mutable loci in pathogenic bacteria. Curr. Biol. 4:24-33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliver, A., R. Canton, P. Campo, F. Baquero, and J. Blazquez. 2000. High frequency of hypermutable Pseudomonas aeruginosa in cystic fibrosis lung infection. Science 288:1251-1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Read, T. D., S. W. Satola, J. A. Opdyke, and M. M. Farley. 1998. Copy number of pilus gene clusters in Haemophilus influenzae and variation in the hifE pilin gene. Infect. Immun. 66:1622-1631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richardson, A. R., Z. Yu, T. Popovic, and I. Stojiljkovic. 2002. Mutator clones of Neisseria meningitidis in epidemic serogroup A disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:6103-6107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rodriguez, C. A., V. Avadhanula, A. Buscher, A. L. Smith, J. W. St. Geme III, and E. E. Adderson. 2003. Prevalence and distribution of adhesins in invasive non-type b encapsulated Haemophilus influenzae. Infect. Immun. 71:1635-1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schaaper, R. M., and R. L. Dunn. 1987. Spectra of spontaneous mutations in Escherichia coli strains defective in mismatch correction: the nature of in vivo DNA replication errors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 84:6220-6224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schumacher, S., R. P. P. Fuchs, and M. Bichara. 1997. Two distinct models account for short and long deletions within sequence repeats in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:6512-6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stancheva, I., T. Koller, and J. M. Sogo. 1999. Asymmetry of Dam remethylation on the leading and lagging arms of plasmid replicative intermediates. EMBO J. 18:6542-6551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss, B. S., D. Sagher, and S. Acharya. 1997. Role of proofreading and mismatch repair in maintaining the stability of nucleotide repeats in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 25:806-813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van Ham, S. M., L. van Alphen, F. R. Mooi, and J. P. van Putten. 1993. Phase variation of H. influenzae fimbriae: transcriptional control of two divergent genes through a variable combined promoter region. Cell 73:1187-1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Ham, S. M., L. van Alphen, F. R. Mooi, and J. P. M. van Putten. 1994. The fimbrial gene cluster of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Mol. Microbiol. 13:673-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viswanathan, M., V. Burdett, C. Baitinger, P. Modrich, and S. T. Lovett. 2001. Redundant exonuclease involvement in Escherichia coli methyl-directed mismatch repair. J. Biol. Chem. 276:31053-31058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]