Abstract

Research has demonstrated that exposure to violence can result in many negative consequences for youth, but the degree to which neighborhood conditions may foster resiliency among victims is not well understood. This study tests the hypothesis that neighborhood collective efficacy attenuates the relationship between adolescent exposure to violence, substance use, and violence. Data were collected from 1,661–1,718 adolescents participating in the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN), who were diverse in terms of sex (51% male, 49% female), race/ethnicity (48% Hispanic, 34% African American, 14% Caucasian, and 4% other race/ethnicity), and age (mean age 12 years; range: 8–16). Information on neighborhood collective efficacy was obtained from adult residents, and data from the 1990 U.S. Census were used to control for neighborhood disadvantage. Based on hierarchical modeling techniques to adjust for the clustered data, Bernoulli models indicated that more exposure to violence was associated with a greater likelihood of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use and perpetration of violence. Poisson models suggested that victimization was also related to a greater variety of substance use and violent behaviors. A moderating effect of collective efficacy was found in models assessing the variety of substance use; the relationship between victimization and substance use was weaker for youth in neighborhoods with higher versus lower levels of collective efficacy. These findings are consistent with literature indicating that social support can ameliorate the negative impact of victimization. This investigation extends this research to show that neighborhood social support can also help to promote resiliency among adolescents.

Keywords: Exposure to Violence, Victimization, Substance Use, Violence, Neighborhoods, Collective Efficacy

INTRODUCTION

Accumulating evidence indicates that exposure to violence has negative effects on children’s development, with those who witness or experience violence in their communities having an increased likelihood of mental health problems, substance use, aggression, and violence (Buka, Stichick, Birdthistle, & Earls, 2001; Turner, Finkelhor, & Ormrod, 2006; Wilson, Smith Stover, & Berkowitz, 2009). While such research has helped to establish the basic relationship between victimization and negative outcomes for youth, relatively few studies have assessed factors that may moderate the impact of exposure to violence (for exceptions, see: Aceves & Cookston, 2007; Hardaway, McLoyd, & Wood, 2012; Kort-Butler, 2010; Luthar & Goldstein, 2004). In particular, there is a dearth of research examining the degree to which neighborhood conditions may ameliorate the negative consequences of victimization, even though a growing body of research has indicated that neighborhood collective efficacy can reduce problem behaviors and promote well-being of youth (Browning & Erickson, 2009; Elliott et al., 1996; Molnar, Cerda, Roberts, & Buka, 2008; Sampson, 2011), even among those living in high-risk, high-poverty communities, which tend to have elevated rates of violence (Buka et al., 2001; Lauritsen, 2003; Sampson & Lauritsen, 1994).

Our study builds upon research examining resiliency among those exposed to violence (Aisenberg & Herrenkohl, 2008; Lynch, 2003; Margolin & Gordis, 2004) by examining the processes that encourage positive adaptation and/or reduce the likelihood of severe impairment among those exposed to adversity such as victimization (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000; Masten, 2001). Specifically, we investigate the degree to which neighborhood collective efficacy moderates the relationship between exposure to violence, substance use, and violence. In this article, “exposure to violence” and “victimization” will be used interchangeably to refer to episodes in which youth witness and/or directly experience violent victimization. We focus on experiences that occur outside the home, as exposure to community violence has received comparatively less empirical attention than victimization within the home, such as witnessing violence between parents or being physically abused by a caregiver (Buka et al., 2001). Further, national surveys indicate that, during adolescence, rates of exposure to community violence are very prevalent and likely surpass rates of child maltreatment (Finkelhor, Ormrod, & Turner, 2009; Finkelhor, Turner, Ormrod, & Hamby, 2009).

We focus on the outcomes of substance use and violence because both behaviors are particularly likely to occur during adolescence and, when initiated early in the life-course, can result in drug abuse and addiction (Hingson, Heeren, & Winter, 2006; Windle et al., 2009) and frequent, violent offending (Farrington, 2003; Moffitt, 1993; Sampson & Laub, 1993) lasting into adulthood. Furthermore, although prior research has demonstrated that exposure to violence can increase substance use (Begle et al., 2011; Kilpatrick et al., 2000; Sullivan, Kung, & Farrell, 2004; Vermeiren, Schwab-Stone, Deboutte, Leckman, & Ruchkin, 2003) and the perpetration of violence among adolescents (Brookmeyer, Henrich, & Schwab-Stone, 2005; Farrell & Bruce, 1997; Gorman-Smith, Henry, & Tolan, 2004; Hagan & Foster, 2001), most research has assessed effects on only one of the two outcomes (for exceptions, see: Farrell & Sullivan, 2004; Hay & Evans, 2006; Kaufman, 2009), which makes it difficult to draw firm conclusions regarding the impact(s) of victimization (Saunders, 2003). Our study seeks to provide more comprehensive and potentially more valid information regarding the effects of exposure to violence by assessing its association with both substance use and violence (modeled as separate outcomes) using information from a diverse sample of youth.

Individual and Neighborhood-Level Explanations of Adolescent Development

This study draws upon General Strain Theory (Agnew, 1992, 2006) and collective efficacy theory (Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997) to investigate the individual and contextual factors that affect the relationship between victimization and the development of problem behaviors. General Strain Theory (Agnew, 1992, 2006) posits that victimization is a stressful event particularly likely to result in adolescent deviance. Both witnessing and experiencing violence can be harmful because most adolescents are exposed to one or more of these types of events during their lifetimes (Finkelhor, Turner, et al., 2009), and most lack well-developed skills to positively cope with these experiences. In the absence of such resources, teenagers may respond to victimization with negative coping mechanisms, including both substance use and violence. Substance use can provide at least a temporary escape from the emotional and physical pain caused by exposure to violence (Agnew & White, 1992; Kaufman, 2009; Taylor & Kliewer, 2006), while aggressive, retaliatory actions can help alleviate the anger, frustration, and anxiety that may be generated by seeing an acquaintance, close friend, or family member victimized, or by being directly harmed by someone else (Agnew, 2002).

Collective efficacy theory (Sampson et al., 1997) focuses on the neighborhood processes that may affect positive and negative youth development, specifically the presence of shared trust and cohesion between residents and informal attempts of residents to regulate youth behavior. Communities with high levels of collective efficacy are those in which adults and youth are more likely to know one another and residents are more likely to take actions on behalf of the community to reduce delinquency and crime (Sampson et al., 1997; Simons, Gordon Simons, Burt, Brody, & Cutrona, 2005). This is particularly true when it comes to child-rearing and socialization, which is more likely to be a communal activity than the sole responsibility of parents in neighborhoods with high levels of collective efficacy (Browning, Leventhal, & Brooks-Gunn, 2005; Fagan & Wright, 2012). That is, adult residents in such areas will be more likely to share in monitoring youth (and youth group/gang) activities and intervene when they see disorderly behavior occurring (Sampson et al., 1997). Residents will also be more likely to lobby for resources, services, and social organizations that can benefit both children and adults in the neighborhood (Coleman, 1988).

Children living in communities with high levels of collective efficacy should thus feel an added layer of supervision and will be less likely to engage in delinquency because they know that such actions will be noticed and result in negative sanctions (Sampson et al., 1997). They should also perceive greater levels of protection and support, knowing that, in addition to their parents and family members, there are others in the neighborhood who are looking out for them and who can be trusted to act on their behalf (Aisenberg & Herrenkohl, 2008). Youth who feel closely connected to and supported by adults in their neighborhoods should refrain from deviance to avoid disappointing those who care about them (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Hirschi, 1969). In fact, research supports these hypotheses and indicates that higher levels of collective efficacy are related to lower community rates of youth and/or adult offending (Browning, Feinberg, & Dietz, 2004; Elliott et al., 1996; Morenoff, Sampson, & Raudenbush, 2001; Sampson, 2012; Sampson et al., 1997). These relationships exist even when taking neighborhood poverty into account, which can itself increase crime and/or reduce collective efficacy in a neighborhood (Sampson et al., 1997). Some studies utilizing multi-level statistical analysis have also shown that neighborhood cohesion and/or social control reduces the likelihood of delinquency among adolescents in the neighborhood (Elliott et al., 1996; Jain, Buka, Subramanian, & Molnar, 2010; Molnar, Miller, Azrael, & Buka, 2004; Simons et al., 2005).

Despite evidence linking collective efficacy to a range of positive outcomes, very few studies have assessed its impact on substance use as a discrete behavior (though see Maimon & Browning, 2012; Musick, Seltzer, & Schwartz, 2008). In addition, many studies have failed to demonstrate a direct impact of neighborhood social cohesion and/or informal social control on individuals’ likelihood of offending (Karriker-Jaffe, Foshee, Ennett, & Suchindran, 2009; Maimon & Browning, 2010; Rankin & Quane, 2002; Sampson, Morenoff, & Raudenbush, 2005). According to Sampson (2012), it may be difficult to find a direct effect on neighborhood processes on individual behavior because youth are likely to spend much time outside of their neighborhood of origin (e.g., when attending school or participating in afterschool activities) and may commit deviant acts in other areas. Others have posited that the direct impact of neighborhood characteristics are weaker compared to more proximal influences of delinquency (e.g., peer or parental characteristics) (Elliott et al., 1996), but also that neighborhood context can affect individual behaviors in complex ways (Foster & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). We investigate this possibility by assessing the degree to which collective efficacy moderates the relationship between exposure to violence, substance use, and violence.

Social Support as a Protective Factor That Can Buffer the Impact of Victimization

According to General Strain Theory, not all victims will respond to stress with deviant coping (Agnew, 1992). In fact, there is evidence that some youth are resilient and do not engage in problem behaviors and/or can meet developmental goals even if they have witnessed or experienced violence (Agnew, 2006; Aisenberg & Herrenkohl, 2008; Lynch, 2003). One of the primary protective factors posited by strain theory to reduce the harmful impact of victimization is the presence of social support— having strong, emotional attachments to pro-social individuals or groups (Agnew, 2006; Hay & Evans, 2006; Luthar & Goldstein, 2004). Strong social support can buffer the negative impact of exposure to violence among adolescents who, given their lack of emotional maturity, may be ill equipped to deal with the stress of victimization on their own (Agnew, 1992). Support from peers, family members, and other adults can provide youth with resources they can draw upon to help make sense of, more appropriately respond to, and alleviate the physical and emotional damage that may follow from victimization (Aceves & Cookston, 2007; Agnew, 2006; O'Donnell, Schwab-Stone, & Muyeed, 2002; Sullivan et al., 2004).

Studies investigating the degree to which social support buffers the impact of exposure to violence in the community have primarily focused on children’s attachments to family members. This literature has often shown a reduced impact of victimization on delinquency among children with closer relationships with their parents compared to those with weaker family attachments (Brookmeyer et al., 2005; Gorman-Smith et al., 2004; Kliewer et al., 2006; O'Donnell et al., 2002). However, studies have also shown no evidence of moderation (Hay & Evans, 2006), and moderating effects have been inconsistent across and sometimes within studies, depending on the family constructs and/or outcomes assessed (Proctor, 2006). Similarly, research has shown mixed results for the ability of social support received from peers or other adults to condition the relationship between victimization and delinquency (Jain & Cohen, 2013; O'Donnell et al., 2002; Rosario, Salzinger, Feldman, & Ng-Mak, 2003).

While parents are typically identified as the primary source of social support for children, attachments to and support from other adults in the community become increasingly important for older youth (Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Sampson & Laub, 1993). By extension, neighborhood levels of social support, operationalized as collective efficacy in this study, should be important for victims. In such areas, adults will be more likely to know children and to act on their behalf, and, as Sampson (2012) notes, these advantages can be drawn upon in times of need. Victims should be able to access these sources of support, protection, and resources when coping with stress. In the absence of such support, victimized youth may feel more alone, afraid, overwhelmed, and unable to cope.

We hypothesize that collective efficacy will ameliorate the negative effects of exposure to violence, such that the relationships between victimization, substance use, and violence will be attenuated in neighborhoods with higher versus lower levels of collective efficacy. This hypothesis is made with caution, however, given the lack of prior research investigating the potential for neighborhood collective efficacy to condition the impact of exposure to violence on adolescent problem behaviors (Aisenberg & Herrenkohl, 2008; Foster & Brooks-Gunn, 2009). In fact, our review of the literature indicated no prior work investigating this claim. The most similar research to the current study (i.e., utilizing the same dataset and primary measures) examined the moderating effects of collective efficacy on the relationship between exposure to violence and youth resiliency, measured as the percentage of youth reporting lower than average levels of internalizing (Jain, Buka, Subramanian, & Molnar, 2012) and externalizing (Jain & Cohen, 2013) problems at one point in time and changes over time in these outcomes. These studies found no evidence that independent constructs representing neighborhood cohesion and informal social control or a combined measure of collective efficacy moderated the impact of victimization on these outcomes.

However, Jain et al. (2012; Jain & Cohen, 2013) did not assess whether or not collective efficacy conditioned the relationship between exposure to violence and substance use or violence, and it is possible that the moderating effects of collective efficacy could affect these behaviors but not others. Indeed, protective effects of collective efficacy have been found in studies examining other dependent variables. For example, the relationships between unstructured youth socializing (i.e., “routine activities”) and violence (Maimon & Browning, 2010), and between retail alcohol outlets and youth drinking (Maimon & Browning, 2012) have been demonstrated as weaker in neighborhoods with higher versus lower levels of collective efficacy. Similarly, Molnar et al. (2008) found that collective efficacy increased the positive effects of support from parents and other adults on adolescent aggression, but this moderating effect was not found when examining delinquency as an outcome. In contrast, Simons et al. (2005) reported that the impact of positive parenting on youth delinquency was enhanced in neighborhoods with greater collective efficacy. These mixed findings, as well as those reported in studies examining the direct effects of collective efficacy, demonstrate that neighborhood context may impact youth development in complex ways and that its impact could vary across particular outcomes and/or populations.

THE CURRENT STUDY

Our study builds off of and extends both victimization and neighborhood research by testing, likely for the first time, the hypothesis that neighborhood collective efficacy will buffer the effects of exposure to violence on adolescent substance use and violence. Analyses rely on data from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN) (Earls, Brooks-Gunn, Raudenbush, & Sampson, 2002), arguably one of the most methodologically advanced studies of neighborhoods. The structure of the data allow for multi-level modeling, which is preferred when investigating the impact of neighborhood features on individual outcomes (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). Data were collected on a wide range of processes that may affect adolescent development, allowing us to control for a range of individual-level confounders which may be related to substance use and violence. Many victimization studies have failed to include multiple control variables in their analyses and, consequently, may have over-estimated the impact of exposure to violence on behaviors (Saunders, 2003). We also control for community economic disadvantage, which is important given it potential to affect substance use, violence, and collective efficacy (e.g., Galea, Rudenstine, & Vlahov, 2005; Sampson et al., 1997).

METHOD

Sample

To gather information regarding the ways in which neighborhood context influences children’s development, the PHDCN design divided all of Chicago’s 847 census tracts into 343 geographically contiguous neighborhood clusters. The neighborhood clusters were then stratified by seven categories of racial/ethnic diversity and three levels of socio-economic status, and 80 neighborhood clusters were selected via stratified probability sampling. Households within these areas that had at least one child in one of seven age cohorts (newborns and children ages 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18) were eligible to participate in the Longitudinal Cohort Study, and 6,228 individuals (75% of the eligible population) agreed to participate. Children and their caregivers in these households were interviewed approximately every 2.5 years, with wave one conducted in 1994–1997, wave two in 1997–2000, and wave three in 2000–2002.

Data regarding residents’ perceptions of neighborhood collective efficacy were taken from the Community Survey portion of the PHDCN, conducted in all 343 neighborhood clusters. Using a three-stage sampling design, city blocks were sampled within each of these clusters, dwelling units were sampled within blocks, and one adult resident was sampled within each dwelling unit and interviewed during 1994–1995. The current study relies on Community Survey information collected from only the 80 neighborhood clusters in which the longitudinal study participants resided.

Analyses were restricted to youth from three age cohorts (Cohorts 9, 12, and 15) of the Longitudinal Cohort Study and data collected at waves one and two. Respondents resided in 79 of the 80 neighborhood clusters; one did not have any respondents from Cohorts 9–15. At wave one, 2,344 youth in Cohorts 9–15 participated in the study, and 1,987 (85% of the original sample) participated at wave two. Due to listwise deletion, 326 and 269 youth were dropped from the analyses assessing wave two substance use and violence, respectively, such that the analysis samples included 1,661 youth for substance use outcomes and 1,718 youth for violence outcomes. A comparison of the sample of all youth in Cohorts 9–15 participating at wave one (N=2,344) and the analyses samples yielded no significant differences on the primary independent or dependent variables. However, compared to the initial sample, both samples had significantly (p ≤ .05) more Hispanic youth and higher family income.

Measures

Measures of exposure to violence, substance use and violence were all drawn from wave two of the study. Although all three variables were assessed at each wave, several considerations informed our decision to analyze the wave two concurrent measures rather than rely on the prospective data. First, strain theory posits that victimization is likely to have an immediate impact on behavior (Agnew, 2006),and so measuring the independent and dependent variables close in time is consistent with the theory. Secondly, at wave one, exposure to violence was assessed using a more limited number of items (capturing only indirect experiences of witnessing or hearing about others’ victimization), while wave two measures captured greater diversity (i.e., indirect and direct forms of violence) in victimization experiences. Thirdly, we wished to avoid using outcomes from wave three as these measures were further removed from the assessment of collective efficacy and because sample mobility accumulated over time. More information about the primary variables included in the analyses is given below, and the descriptive properties of these and the control variables are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive Information for the Dependent and Independent Variables

| Mean | SD | Min-Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variables | ||||

| Any past month TAM | Youth reports of any use of tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana in the past month (wave 2) | .18 | .38 | 0–1 |

| Any past year violence | Youth reports of perpetration of any of 7 violent behaviors in the past year (wave 2) | .30 | .46 | 0–1 |

| Variety of past month TAM | Number of substances (tobacco, alcohol or marijuana) used in the past month (wave 2) | .30 | .72 | 0–3 |

| Variety of past year violence | Number of 7 violent behaviors perpetrated in the past year (wave 2) | .50 | .95 | 0–6 |

| Neighborhood Variables | ||||

| Collective efficacy | Three-level item response model based on 10 indicators of social cohesion and informal social control reported by adult residents in the Community Survey (1995–1996) | −.00 | .22 | −.46–.64 |

| Concentrated disadvantage | Principal components factor analysis using three items (alpha=.81) from the 1990 Census: the percentage of residents below poverty, households receiving public assistance, and residents unemployed | −.00 | 1.01 | −1.51–2.35 |

| Individual-Level Variables | ||||

| Exposure to violence | Number of 14 violent acts witnessed or experienced by youth in the past year (wave 2) | 2.04 | 2.13 | 0–11 |

| Age | Youth's age in years (wave 1) | 11.91 | 2.41 | 7.77–16.38 |

| Male | Dichotomous variable indicating youth is male (wave 1) | .51 | .50 | 0–1 |

| Caucasian | Dichotomous variable indicating youth is Caucasian (wave 1) | .14 | .35 | 0–1 |

| Hispanic | Dichotomous variable indicating youth is Hispanic (wave 1) | .48 | .50 | 0–1 |

| African American | Dichotomous variable indicating youth is African American (wave 1) | .34 | .47 | 0–1 |

| Other race/ethnicity | Dichotomous variable indicating youth is of another race/ethnicity (wave 1) | .04 | .19 | 0–1 |

| Socioeconomic status | Princip al components factor analysis of 3 items (alpha=.42) reported by caregivers at waves 1 or 2: household income, education of both parents, caregivers' employment status. | .16 | .99 | −1.67–2.11 |

| Low self-control | Standardized summed scale of 17 items (alpha=.75) reported by caregivers related to youth's inhibitory control, decision-making, sensation seeking, and persistence (Buss & Plomin, 1975; Gibson, Sullivan, Jones, & Piquero, 2010) at wave one. | −.02 | .99 | −2.52–3.40 |

| Routine activities | Standardized summed scale of 4 items (alpha=.58) rating youth reports of their engaging in unstructured, unsupervised activities (e.g., hanging out with peers and going to parties). (Osgood, Wilson, O'Malley, Bachman, & Johnston, 1996) at wave two. | .01 | 1.00 | −2.50–2.34 |

| Curfew | Sum of caregivers' reports that children had to sleep at home on school nights, had a curfew on school nights, and had a curfew on weekend nights (3 items; alpha=.60; wave two). | 2.86 | .46 | 0–3 |

| Family social support | Standardized summed scale of 6 items (alpha=.67) rating youth agreement with items like “my family….will always be there for me” (Turner, Frankel, & Levin, 1983) at wave one. | .03 | .95 | −5.42–.81 |

| Peer social support | Standardized, summed scale of 9 items (alpha=.70) rating youth agreement with items such as “I have at least one friend I could tell anything to” (Turner et al., 1983) at wave one. | .03 | .99 | −3.97–1.34 |

| Peer drug use | Standardized summed scale reflecting the number of friends reported by youth who used marijuana, alcohol, and tobacco in the past year (4 items; alpha=0.85; wave two). | −.03 | .99 | −.73–4.79 |

| Perceptions of drug harmfulness | Standardized summed scale of 7 items (alpha=.76) in which youth reported “how much people would hurt themselves” if they regularly used tobacco, alcohol and marijuana | .01 | .99 | −4.47–1.52 |

| Any prior TAM use | (National Household Survey on Drug Abuse, 1991) at wave two. Dichotomous variable; youth reports of any past year tobacco, alcohol, marijuana use (wave one) | .18 | .39 | 0–1 |

| Peer delinquency | Standardized summed scale based on youth reports of the number of their friends who engaged in 11 delinquent acts (alpha=.085) in the past year (wave two). | −.04 | .95 | −1.11–4.82 |

| Any prior violence | Dichotomous variable; youth reports of any of 7 violent acts in the past year (wave one). | .33 | .47 | 0–1 |

Note: The descriptives are based on 1,718 individuals from 79 neighborhoods clusters.

Substance Use

Youth substance use was operationalized as a combined measure of past month tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use assessed at wave two. Based on questions derived from the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (1991), respondents reported the number of days in the past month they used tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana, respectively, on a seven-point frequency scale ranging from 0 to 21 or more days. Because each substance was reported at fairly low rates (approximately 12 percent reported using tobacco, 12 percent reported drinking, and 7 percent reported smoking marijuana) and frequencies were highly skewed, each item was dichotomized to differentiate non-users and users. These three items were then summed and two dependent variables created. The first was a dichotomous measure representing any past month tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana (TAM) use, which differentiated those reporting no use of any of the three substances with those who reported use of one or more substance at least once in the past month. A count variable was also created to capture the variety of past month tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana (TAM) use, which could range from 0–3 depending on whether youth reported using zero, one, two, or all three substances at least once in the month prior to the wave two interview. We chose to model the dependent variables in these two different ways given research suggesting that the predictors of any participation in delinquency/crime may differ from those influencing the perpetration of multiple offenses (e.g., variety in offending) (Blumstein, Cohen, & Farrington, 1988). This specificity is particularly important when examining relatively novel research questions such as those posed in the current study.

Violence

Youth violence was also modeled both as a dichotomous variable and as a count variable assessing the variety of violent offending. At wave two, youth were asked to report the number of times in the past year they had committed seven violent acts using items adapted from the Self-Report Delinquency Questionnaire (Huizinga, Esbensen, & Weiher, 1991). Behaviors included: throwing objects at someone, hitting someone, hitting someone you live with, carrying a weapon, attacking with a weapon, being involved in a gang fight, and committing robbery. Each item was dichotomized and summed, then re-coded as a dichotomous variable differentiating those who reported no acts of violence in the past year and those who reported any past year violence. A measure reflecting the total number or variety of past year violence reported was also utilized.

Collective Efficacy

Following Sampson et al. (1997), neighborhood collective efficacy was based on 10 items from adults participating in the Community Survey and reflected the degree of social cohesion and informal social control between neighbors. To measure social cohesion (i.e., trust and support), residents were asked five items regarding how strongly they agreed (on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”) that: people around here are willing to help their neighbors; this is a close-knit neighborhood; people in this neighborhood can be trusted; people in this neighborhood generally don’t get along with each other (reverse coded); and people in this neighborhood do not share the same values (reverse coded). To assess informal social control, residents were asked five items regarding the likelihood (assessed on a five-point Likert scale from “very unlikely” to “very likely”) that their neighbors would intervene if: children were skipping school and hanging out on a street corner; children were spray painting graffiti on a local building; children were showing disrespect to an adult; a fight broke out in front of their house; and the fire station closest to their home was threatened with budget cuts. Following Sampson et al. (1997) and others (Browning et al., 2004; Morenoff et al., 2001), the social cohesion and informal social control scales were combined into a single measure of collective efficacy using a three-level item response model. The level-one model adjusted the within-person collective efficacy scores by item difficulty, missing data, and measurement error. The level-two model estimated neighborhood cluster collective efficacy scores adjusting for the social composition of each neighborhood. In particular, potential biases in perceptions of each construct resulting from characteristics related to gender, marital status, homeownership, ethnicity and race, residential mobility, years in the neighborhood, age, and socioeconomic status were controlled at level-two. Thus, across residents within neighborhood clusters and controlling for potential respondent bias, the true scores of the latent construct of collective efficacy vary randomly around the neighborhood mean. Finally, the level-three model allowed each neighborhood cluster’s mean collective efficacy score to vary randomly around a grand mean. The empirical Bayes residual from the level-three model constitutes the neighborhood level of collective efficacy after controlling for item difficulty and neighborhood social composition and was therefore used as the ‘true’ neighborhood score on collective efficacy. The internal consistency of this scale at the neighborhood level was 0.85.

Neighborhood concentrated disadvantage

Neighborhood disadvantage was based on a principal components factor analysis using information from the 1990 U.S. Census, with census tract data linked to corresponding neighborhood clusters. Similar to prior research (Molnar et al., 2008; Molnar et al., 2004), this measure draws from three poverty-related variables (alpha=0.81): the percentage of residents in a neighborhood cluster who were below the poverty line, receiving public assistance, and unemployed. Higher values reflect greater economic disadvantage.

Exposure to violence

Exposure to violence was assessed by youths’ responses to 12 items from the My Exposure to Violence survey (Selner-O'Hagan, Kindlon, Buka, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1998) at wave two. Based on dichotomous items, youth reported whether or not in the past year they had ever been (6 items), or had ever seen anyone else (6 items): chased, hit, attacked with a weapon, shot, shot at, or threatened at least once in the past year. For each item, respondents were also asked to report where the violence occurred, including “in school,” “in your neighborhood,” “outside your neighborhood,” and “inside your home.” Given that almost no respondents reported only experiencing violence in their home, the measure is best conceptualized as assessing victimization in the school/community setting. Following other PHDCN research (Gibson, Morris, & Beaver, 2009; Zimmerman & Pogarsky, 2011), the 12 dichotomous items were summed to measure the total number (count) of victimization episodes reported.

Control variables

Models control for an array of individual-level factors shown in prior research to be associated with both substance use and violence (e.g., Catalano & Hawkins, 1996; Durlak, 1998; Farrington, 2003), including demographic characteristics (e.g., sex, age, and family socioeconomic status), youth self-control, involvement in unstructured/routine activities, parent supervision (setting curfews), and presence of social support from family members and peers. In models analyzing substance use, we also control for youth exposure to substance-using peers, individual perceptions that drug use is harmful, and wave one substance use. In models analyzing violence, we control for exposure to delinquent peers and wave one violence (see Table 1).

Analysis Plan

Hierarchical modeling techniques (Hierarchical Linear Modeling [HLM]) (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002) using the statistical software HLM 7.0 (Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, Congdon, & du Toit, 2004) were utilized to adjust for the correlated error that exists with the clustered data (e.g., youth clustered within neighborhoods). Using these techniques, analyses are based on appropriate sample sizes and existing variance is partitioned at different levels of analyses (the individual and neighborhood levels). Bernoulli models, analogous to logistic regression models, were used to analyze the dichotomous outcomes, with separate models representing any substance use and any violence. Poisson models were utilized when assessing the variety of substance use and the variety of violence; these models corrected for over-dispersion of the outcomes. In these models, the covariates were fixed and grand-mean centered across neighborhood clusters, but the intercepts and the effect of exposure to violence were allowed to vary across neighborhoods.

The analyses proceeded in four stages, which were first conducted using the dichotomous dependent variables and then repeated using the variety measures. First, unconditional models were used to examine the distribution of outcomes across neighborhood clusters. These tests indicated significant (p<.05) variation in both substance use and violence across neighborhood clusters, which supported further testing for neighborhood influences on these behaviors. Second, intercepts-as-outcome models were analyzed to examine the relationship between exposure to violence, substance use, and violence, accounting for other individual-level covariates. Third, the neighborhood-level variables were added to the models to assess their main effects on the rates of substance use and violence. When conducting the individual-level analyses, the reliability of the intercept was reduced. To adjust for this situation, the Empirical Bayes estimates of the individual-level intercepts and slopes were modeled at level-two (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002; Raudenbush, Bryk, Cheong, & Congdon, 2004). In the last step, slopes-as-outcomes models were analyzed; these models assessed whether the relationships between exposure to violence, substance use, and violence were moderated by neighborhood collective efficacy. The neighborhood-level effects on the slopes were estimated, controlling for the individual-level predictors as well as the main effects of both collective efficacy and concentrated disadvantage. Tolerance values were all above 0.40, suggesting that multicollinearity was not a problem in the final models (Allison, 1999).

RESULTS

As shown in Table 1, the analysis sample was a mean age of 12 years at wave one, 51% male, and predominately of minority race/ethnicity, with 48% reporting their race/ethnicity as Hispanic, 34% African American, 14% Caucasian, and 4% of another race/ethnicity. Exposure to violence was relatively common, with youth in this sample reporting a mean of just over two acts of violence either witnessed or perpetrated against them in the year prior to the wave two survey (see Table 1). At wave two, approximately 18% of respondents reported any use of tobacco, alcohol, or marijuana in the past month, with a mean of 0.30 substances (range: 0–3). About 30% of respondents reported committing any of the seven assessed violent behaviors in the past year, with a mean of 0.50 acts (range: 0–6).

The results of models assessing the relationship between exposure to violence and the likelihood of any past month substance use and any past year violence are shown in the top half of Table 2. Controlling for youth demographic characteristics and a range of individual-level risk and protective factors, youth who witnessed or experienced a greater variety of violent acts had a significantly greater likelihood of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use in the past month (b=.26, p <.01), and violence in the past year (b=.46, p <.01). Some control variables were also related to the likelihood of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use. Specifically, older respondents reported a greater likelihood of substance use than younger children and African Americans had a lower likelihood of use than Caucasians. Youth who engaged in more unstructured, unsupervised routine activities and those who reported prior substance use were more likely to report any past month substance use, while those who perceived substance use as more harmful were less likely to report any use compared to youth with more lax views of substance use harm. The likelihood of engaging in any violence was greater for African American youth compared to Caucasians, youth with lower levels of self-control, those with more unsupervised routine activities, and those who reported prior violence.

Table 2.

The Association Between Exposure to Violence, Neighborhood Characteristics, and Any Past Month Tobacco, Alcohol, and Marijuana (TAM) Use and Any Past Year Violence, and Cross-Level Interactions

| Any Past Month TAM Use (N=1661) |

Any Past Year Violence (N=1718) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | ||

| Intercept | −2.55** | .11 | −1.15** | .07 | |

| Exposure to violence | .26** | .04 | .46** | .03 | |

| Age | .40** | .05 | .02 | .03 | |

| Male | −.07 | .19 | .20 | .13 | |

| Hispanica | −.49 | .30 | −.16 | .21 | |

| African Americana | −.91** | .28 | .51* | .23 | |

| Other race/ethnicitya | −.90 | .50 | −.43 | .34 | |

| Socioeconomic status | .04 | .09 | .01 | .08 | |

| Low self-control | −.01 | .08 | .20* | .08 | |

| Routine activities | .47** | .10 | .28** | .08 | |

| Curfew | −.12 | .13 | −.09 | .13 | |

| Family social support | −.05 | .09 | −.01 | .06 | |

| Peer social support | .18 | .09 | −.06 | .07 | |

| Peer drug use | .15 | .09 | -- | -- | |

| Perceptions of drug harmfulness | −.52** | .08 | -- | -- | |

| Any prior TAM use | 1.01** | .22 | -- | -- | |

| Peer delinquency | -- | -- | .07 | .06 | |

| Any prior violence | -- | -- | .92** | .14 | |

| χ2 | 66.25 | 78.09 | |||

| Direct Neighborhood Effects | |||||

| Level-1 intercept | −2.55** | .001 | −1.15** | .01 | |

| Collective efficacy | .01 | .01 | .08 | .04 | |

| Concentrated disadvantage | .001 | .001 | .004 | .01 | |

| R2 | .03 | .05 | |||

| Cross-Level Interactions | |||||

| Exposure to violence | .27** | .001 | .46** | .001 | |

| x Collective efficacy | −.01 | .01 | .001 | .003 | |

| R2 | .02 | .002 | |||

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .05

Notes: Individual-level results are based on Bernoulli models; italicized coefficients indicate that the effect of exposure to violence was allowed to vary randomly across the79 neighborhood clusters; all other variables were fixed across neighborhoods. The level-two and cross-level interaction results are based on Bernoulli models using Empirical Bayes (EB) estimates. Cross-level interactions control for the direct effects of the neighborhood characteristics and all individual-level variables.

Caucasian is the reference group

The results in the lower half of Table 2 pertain to the direct effects of neighborhood collective efficacy and concentrated disadvantage on any substance use or violence, controlling for exposure to violence and the other individual-level variables. None of the direct effects were statistically significant. Neither collective efficacy nor concentrated disadvantage predicted the likelihood of tobacco, alcohol or marijuana use, or violence. The bottom of Table 2 displays the results of the cross-level interaction analyses exploring the moderating effects of collective efficacy on the relationship between exposure to violence and substance use and violence, while controlling for the other level-one variables and direct effects of the neighborhood context. As shown, there was little support that collective efficacy moderated the relationship between exposure to violence and problem behaviors. The cross-level interaction term was not statistically significant in the models examining any past month substance use or any past year violence.

Results of the models assessing the relationships between exposure to violence and the variety of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use, as well as the variety of violent behaviors, are shown in the top half of Table 3. Controlling for individual-level factors, youth who witnessed or experienced a greater number of violent victimizations in their communities reported significantly greater variety of past month tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use (b=.15, p <.01), and a greater variety of violent behaviors in the past year (b=.26, p <.01). In terms of the control variables, older respondents reported more past month substance use than younger children and African Americans reported less use than Caucasians. Youth who reported more routine activities, and those who reported prior substance use reported significantly more variety in their substance use. Finally, individuals who perceived substance use as more harmful reported using fewer substances than youth who expressed more lax views of the harmfulness of substance use. Some control variables were also associated with violence. African American youth reported engaging in a greater variety of violent behaviors than did Caucasians. More violence was reported by those engaging in more unsupervised routine activities and those who had committed violence at wave one. Youth who reported greater familial social support reported less variety of violence than adolescents with lower levels of familial support.

Table 3.

The Association Between Exposure to Violence, Neighborhood Characteristics, and the Variety of Past Month Tobacco, Alcohol, and Marijuana (TAM) Use and the Variety of Past Year Violence, and Cross-Level Interactions

| Variety of Past Month TAM (N=1661) |

Variety of Past Year (N=1718) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | b | SE | |

| Intercept | −2.18** | .08 | −1.17** | .05 |

| Exposure to violence | .15** | .02 | .26** | .02 |

| Age | .28** | .03 | −.01 | .02 |

| Male | −.04 | .12 | .15 | .08 |

| Hispanica | −.14 | .15 | −.06 | .16 |

| African Americana | −.40** | .13 | .35* | .15 |

| Other race/ethnicitya | −.28 | .25 | −.37 | .26 |

| Socioeconomic status | .02 | .06 | −.07 | .04 |

| Low self-control | −.07 | .05 | .08 | .05 |

| Routine activities | .33** | .06 | .21** | .04 |

| Curfew | −.08 | .06 | −.08 | .07 |

| Family social support | −.04 | .04 | −.08* | .04 |

| Peer social support | .12 | .07 | .01 | .04 |

| Peer drug use | .05 | .05 | -- | -- |

| Perceptions of drug harmfulness | −.28** | .04 | -- | -- |

| Any prior TAM use | .74** | .14 | -- | -- |

| Peer delinquency | -- | -- | .04 | .04 |

| Any prior violence | -- | -- | .57** | .10 |

| χ2 | 108.13 | 113.52 | ||

| Direct Neighborhood Effects | ||||

| Level-1 intercept | −2.18** | .01 | −1.17** | .01 |

| Collective efficacy | .13** | .05 | .10 | .07 |

| Concentrated disadvantage | −.01 | .01 | .01 | .02 |

| R2 | .18 | .03 | ||

| Cross-Level Interactions | ||||

| Exposure to violence | .15** | .01 | .26** | .001 |

| x Collective efficacy | −.07** | .03 | .001 | .01 |

| R2 | .09 | .00 | ||

p ≤ .01

p ≤ .05

Notes: Individual-level results are based on overdispersed Poisson models; italicized coefficients indicate that the effect of exposure to violence was allowed to vary randomly across the79 neighborhood clusters; all other variables were fixed across neighborhoods. The level-two and cross-level interaction results are based on overdispersed Poisson models using Empirical Bayes estimates; Cross-level interactions control for the direct effects of the neighborhood characteristics and all individual-level variables.

Caucasian is the reference group

The lower half of Table 3 shows the direct effects of neighborhood collective efficacy and concentrated disadvantage, controlling for exposure to violence and all other individual-level variables. In these models, one direct effect was significant: neighborhoods with higher levels of collective efficacy were associated with greater variety of substance use (b=.13, p <.01) than neighborhoods with lower levels of collective efficacy. Collective efficacy was not significantly related to youth violence, and concentrated disadvantage did not have a significant direct effect on either outcome.

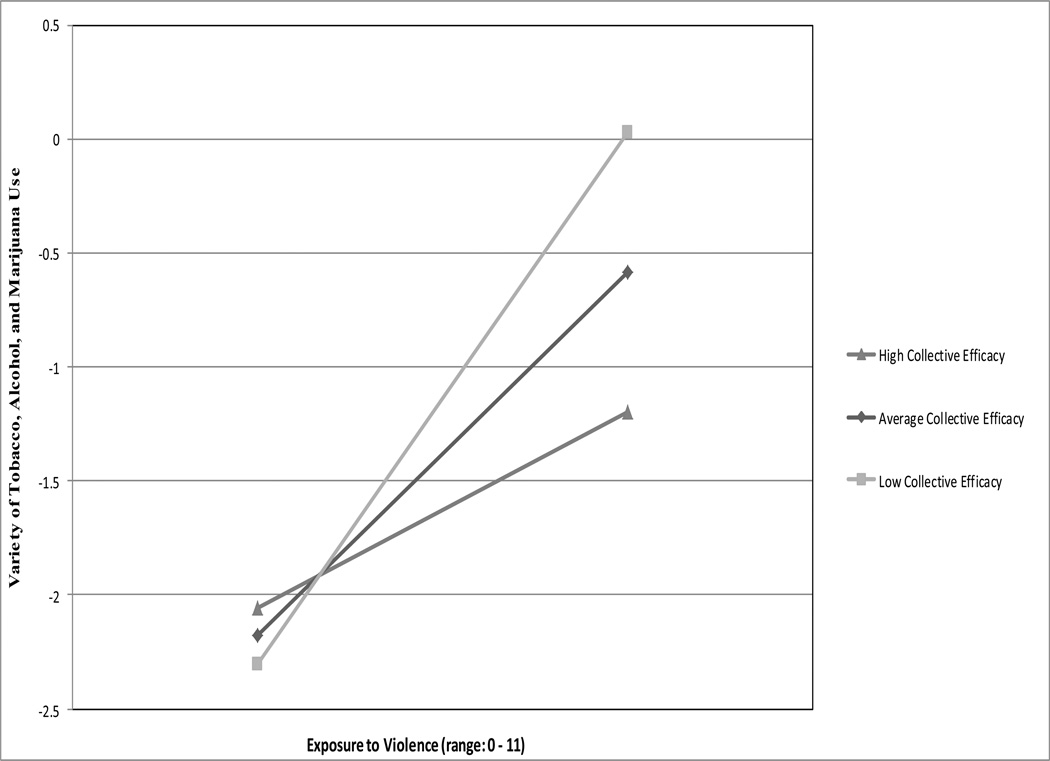

The bottom of Table 3 displays the results of the cross-level interaction exploring the moderating effect of collective efficacy on the relationship between exposure to violence, past month tobacco, alcohol, marijuana use, and past year violence, controlling for the individual-level predictors and direct effects of the neighborhood context. According to these analyses, collective efficacy moderated the relationship between exposure to violence and the variety of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use (b= −.07, p <.01). The negative coefficient indicates that the relationship between exposure to violence and substance use was weaker in neighborhoods with higher levels of collective efficacy compared to neighborhoods with lower levels. The cross-level interaction term was not significant in the model examining past year violence, indicating that collective efficacy did not moderate the relationship between exposure to violence and the variety of youth violence.

Figure 1 graphically depicts the significant cross-level interaction to better illustrate the influence of collective efficacy on the relationship between exposure to violence and substance use. To make the findings more interpretable, collective efficacy was trichotomized to differentiate neighborhood clusters at the highest (one standard deviation above the mean), lowest (one standard deviation below the mean) and average (mean) levels of collective efficacy. As shown in Figure 1, at each of the three levels of collective efficacy, as the number of violent victimizations witnessed or experienced increased, the variety of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use increased. The relationship was strongest for youth in neighborhoods with the lowest levels of collective efficacy (i.e., the slope is steepest for this group), and weakest for those in neighborhoods with the highest levels of collective efficacy, as indicated by the flattening of the slope at higher levels of collective efficacy.

Figure 1.

The Relationship Between Exposure to Violence and the Variety of Past Month Tobacco, Alcohol and Marijuana Use, by Neighborhood Collective Efficacy1

1This model also controlled for the effect of neighborhood disadvantage and all individual-level predictors

DISCUSSION

This study provided what may be the first examination of the potential for neighborhood collective efficacy to buffer the impact of exposure to violence on adolescent substance use and violence. While collective efficacy has been shown to reduce youth offending (Jain et al., 2010; Molnar et al., 2004; Sampson, 2011; Simons et al., 2005), its ability to do so for youth who witness or experience violence in their communities has been subject to very little research. Investigating factors that may help improve youth resiliency in the face of adversity, such as victimization, is important in helping to reduce the negative consequences of such trauma.

The first aim of our study was to test the hypothesis that exposure to violence would be associated with increased substance use and violence. While the negative effects of victimization on each behavior have been shown previously (Begle et al., 2011; Farrell & Bruce, 1997; Gorman-Smith et al., 2004; Sullivan et al., 2004), relatively few studies have examined the consequences of exposure to violence for both outcomes using information from the same respondents. Doing so is important for drawing conclusions regarding the adverse effects of victimization, as it avoids having to compare findings across studies with diverse research designs and sample characteristics (Saunders, 2003). In this study, regardless of their exposure to a variety of other risk and protective factors, youth who experienced a greater number of violent victimizations had an increased likelihood of reporting any substance use and any violence and a greater variety of substance use and violence. These findings suggest the importance of implementing preventive interventions that seek to either reduce the likelihood of youth exposure to violence or to minimize the harmful consequences of these experiences; for example, interventions that can help youth to recognize and more successfully cope with the stress and negative emotions that may follow from seeing significant others harmed or being the victims of violence themselves.

This study also examined the direct effects of neighborhood collective efficacy on substance use and violence. Controlling for exposure to violence, individual-level control variables, and neighborhood concentrated disadvantage, collective efficacy had a significant direct effect in only one of four relationships assessed. Although other research has found collective efficacy to be related to less offending, some of these studies have relied on official crime records (e.g., Kirk & Papachristos, 2011; Sampson et al., 1997), or more serious self-reported offenses (e.g., carrying concealed firearms; Molnar et al., 2004). Collective efficacy may have a weaker direct effect on the somewhat less serious outcomes investigated in the current study. In addition, Sampson (2012) cautions that because youth may commit deviant acts outside their home neighborhood (e.g., when visiting friends), it may be difficult to find a direct effect on neighborhood processes on individual behaviors. In fact, much prior research has failed to find a direct effect of neighborhood collective efficacy (Karriker-Jaffe et al., 2009; Maimon & Browning, 2010; Rankin & Quane, 2002; Sampson et al., 2005) or concentrated disadvantage (Brenner, Bauermeister, & Zimmerman, 2011; Elliott et al., 1996; Tobler, Komro, & Maldonado-Molina, 2009) on substance use or violence, particularly when (potentially more influential) individual-level variables are taken into account, as in the current study.

The one significant direct effect we found indicated that collective efficacy was related to a greater variety of substance use. While not predicted by collective efficacy theory (Sampson, 2012; Sampson et al., 1997), this finding has some prior support. For example, Browning (2012) reported that adolescent alcohol use was elevated in Toronto communities with greater levels of collective efficacy and lower levels of concentrated disadvantage, and Musick et al. (2008) found that collective efficacy was related to greater frequency of youth tobacco use. It could be that if adults and other role models in a community are engaging in substance use themselves, or if they fail to strictly condemn substance use, substance use by youth would likely be elevated, especially if they feel closely connected to these individuals. In fact, neighborhood affluence has been linked to increased drinking (Maimon & Browning, 2012; Snedker, Herting, & Walton, 2009), and wealthier communities are likely to have greater levels of collective efficacy (Sampson et al., 1997). It could also be that parents will supervise their children less closely when they believe other adults are providing oversight (which should occur in high collective efficacy neighborhoods), and this lack of monitoring could increase children’s opportunities to use illegal drugs (Fagan & Wright, 2012). These hypotheses are speculative and require further explanation, particularly as only a few studies have investigated the link between collective efficacy and substance use.

Despite being related to an increased variety of substance use for the full sample, collective efficacy had a protective effect for victims in this study indicating that the relationship between victimization and substance use was reduced for youth living in neighborhoods with higher versus lower levels of collective efficacy. These results are consistent with General Strain Theory (Agnew, 1992, 2006), which posits that the impact of stressful experiences like victimization can be attenuated for those who have positive relationships and strong support from others (Proctor, 2006). While parents can provide such support (Kliewer et al., 2006; O'Donnell et al., 2002), community members can as well (Aisenberg & Herrenkohl, 2008). Our findings suggest that in more cohesive communities in which adults care about and can be counted on to support children’s well-being, victims may feel more supported and be less likely to take refuge in illegal substance use.

While it seems contradictory that collective efficacy could act as a risk factor in one set of analyses and a protective factor in another, similar findings were reported by Maimon and Browning (2010). Based on data from the PHDCN, they reported that collective efficacy significantly increased adolescent involvement in unstructured, routine activities, but the impact of routine activities in increasing violence was reduced in neighborhoods with higher levels of collective efficacy. Other research has demonstrated individuals may react to criminogenic influences in different ways (Blumstein et al., 1988). For example, Marshall and Chassin (2000) found that parent support and monitoring was related to less alcohol use among their full sample of adolescents, but for male participants, the negative impact of having drug-using peers was amplified when parent support was high. The authors speculated that because boys were more likely than girls to seek autonomy and engage in deviance, they might also be more likely to defy parents’ restrictions by following the lead of their deviant peers. In the current study, it could be that, while the majority of the sample responded to higher levels of supervision and controls by adult neighbors by engaging in more substance use, victims were more likely to feel supported than oppressed by collective efficacy, which lowered their levels of substance use. Again, these suppositions are preliminary, and further research is needed to better specify the conditions under which and types of individuals for whom collective efficacy is protective.

Although we posited that neighborhood social support in the form of collective efficacy would reduce the likelihood that victims would engage in violence, this was not evidenced. It is possible, however, that different processes affect substance use and violence. For example, social learning theories posit a different mechanism than does strain theory to explain why youth may react to victimization with violence (Akers, 1985; Bandura & Walters, 1959). According to this perspective, youth who are exposed to violence will learn to emulate such behavior, particularly if the violence is experienced regularly, rarely followed by negative consequences, and comes to be perceived as an acceptable means of solving disputes (Farrell & Bruce, 1997; Margolin & Gordis, 2000). If these mostly cognitive processes are the mechanisms driving the relationship between victimization and violence, neighborhood collective efficacy may be less important in providing a buffering effect. Our study was not designed to investigate such mechanisms, however, and additional research is recommended to investigate this possibility.

Other limitations of the current study could be addressed by future research. In particular, more information is needed to investigate the degree to which other neighborhood structural and/or social factors may condition the impact of exposure to community violence and other forms of victimization on adolescent problem behaviors. Because our study relies on data from just one city—Chicago—it has limited generalizability. Although the sample included youth of diverse racial/ethnic backgrounds, future research should consider how neighborhood factors may influence the impact of victimization on children from suburban and rural communities and in other urban areas. Similarly, it would be interesting to test for differences in neighborhood moderation across youth of different developmental stages/ages. Additional studies that rely on prospective data are needed to better establish the short- and long-term impacts of exposure to violence on problem behaviors and how neighborhood factors can condition these relationships. In this study, reports of victimization and outcomes were all taken from the same data collection point. Although youth reported on victimization occurring during the year prior to the wave two survey and their use of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana in the month prior to the survey, which helps preserve some temporal ordering, such measures were not available to assess youth violence. Finally, our outcome variables do not capture the frequency of substance use or violence, and additional research is need to investigate how exposure to violence may affect repeated involvement in problem behaviors, and the degree to which collective efficacy may moderate these relationships.

CONCLUSION

This study offers new insights into the impact of victimization and neighborhood context on adolescent development. Analyses provided a very stringent test of the basic relationship between multiple forms of victimization (i.e., capturing both indirect and direct exposure to violence) and two public health problems likely to be elevated among adolescents: substance use and violence. Our results indicated that exposure to violence is problematic for youth and that attempts to reduce or prevent substance use and violence should include efforts to reduce the prevalence and consequences of victimization. The contextual implications of this project are more complex, and further study of the role of collective efficacy in shaping youth behaviors is warranted. Similar to other research, this study showed that the direct effects of collective efficacy are modest compared to other, more proximal (individual-level) factors, and that while victims may benefit from living in neighborhoods with higher levels of cohesion and informal controls, such areas may not convey advantages in all situations or for all individuals (Fagan & Wright, 2012; Jain & Cohen, 2013; Musick et al., 2008). In particular, it is important to ensure that all adult residents work together to model and reinforce healthy behaviors of residents (Sampson, 2012).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Grant R01DA30387-01 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse. Points of view or opinions stated in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agency. The data used in this study were made available by the Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research. Neither the collectors of the original data nor the Consortium bear any responsibility for the analyses or conclusions presented here.

Biographies

Abigail A. Fagan is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law at the University of Florida. She received her doctorate in sociology from the University of Colorado. Her research focuses on the causes and prevention of juvenile delinquency and substance use.

Emily M. Wright is an Assistant Professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Nebraska at Omaha. She received her doctorate in criminology from the University of Cincinnati. Her research examines exposure to violence and victimization in neighborhood context as well as the effective correctional responses to female offenders.

Gillian M. Pinchevsky is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. She received her doctorate in Criminology and Criminal Justice from the University of South Carolina. Her research interests include the criminal justice response to domestic violence, as well as adolescent exposure to violence and victimization.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Each of the authors has made substantial contributions to the manuscript. Specifically, AF and EW jointly conceived of the study’s research questions and the design of the study; AF took the lead role in drafting the paper; EW created the dataset to be analyzed in the study and managed the statistical analyses; GP took the lead role in conducting the statistical analyses; and EW and GP helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Abigail A. Fagan,

Emily M. Wright, School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Nebraska at Omaha, 6001 Dodge Street, 218 CPACS, Omaha, NE 68182-0149

Gillian M. Pinchevsky,

References

- Aceves MJ, Cookston JT. Violent victimization, aggression, and parent-adolescent relations: Quality parenting as a buffer for violently victimized youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36:635–647. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology. 1992;30:47–88. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Experienced, vicarious, and anticipated strain: An exploratory study on physical victimization and delinquency. Justice Quarterly. 2002;19(4):603–632. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R. Pressured into crime: An overview of general strain theory. Cary, NC: Roxbury Publishing Company; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Agnew R, White HR. An empirical test of General Strain Theory. Criminology. 1992;30:475–499. [Google Scholar]

- Aisenberg E, Herrenkohl TI. Community violence in context: Risk and resilience in children and families. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23:296–315. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akers RL. Deviant behavior: A social learning approach. 3rd ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Multiple regression: A primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Walters RH. Adolescent aggression. New York, NY: The Ronald Press Company; 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Begle AM, Hanson RF, Danielson CK, McCart MR, Ruggiero KJ, Amstadter AB, Resnick HS, Saunders B, Kilpatrick D. Longitudinal pathways of victimization, substance use, and delinquency: Findings from the National Survey of Adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36:682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumstein A, Cohen J, Farrington DF. Criminal career research: Its value for criminology. Criminology. 1988;26(1):1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner AB, Bauermeister JA, Zimmerman MA. Neighborhood variation in adolescent alcohol use: Examination of socioecological and social disorganization theories. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72:651–659. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brookmeyer KA, Henrich CC, Schwab-Stone M. Adolescents who witness community violence: Can parent support and prosocial cognitions protect them from committing violence? Child Development. 2005;76(4):917–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Feinberg SL, Dietz RD. The paradox of social organization: networks, collective efficacy and violent crime in urban neighborhoods. Social Forces. 2004;83(2):503–534. [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Sexual initiation in early adolescence. American Sociological Review. 2005;70(5):758–778. [Google Scholar]

- Browning S. Neighborhood, school, and family effects on the frequency of alcohol use among Toronto youth. Substance Use and Misuse. 2012;47:31–43. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2011.625070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning S, Erickson P. Neighborhood disadvantage, alcohol use, and violent victimization. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2009;7:331–349. [Google Scholar]

- Buka SL, Stichick TL, Birdthistle I, Earls F. Youth exposure to violence: Prevalence, risk and consequences. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2001;71(3):298–310. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.71.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buss A, Plomin R. A temperament theory of personality development. New York, NY: Wiley; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The Social Development Model: A theory of antisocial behavior. In: Hawkins JD, editor. Delinquency and crime: Current theories. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1996. pp. 149–197. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. The American Journal of Sociology. 1988;94:S95–S120. [Google Scholar]

- Durlak JA. Common risk and protective factors in successful prevention programs. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:512–520. doi: 10.1037/h0080360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earls FJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Raudenbush SW, Sampson RJ. Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods (PHDCN): Wave 1, 1994–1997 from Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, Grant 93-IJ-CX-K005. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D, Sampson RJ, Elliott A, Rankin B. The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;33(4):389–426. [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Wright EM. The effects of neighborhood context on youth violence and delinquency: Does gender matter? Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2012;10(1):64–82. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Bruce SE. Impact of exposure to community violence on violent behavior and emotional distress among urban adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1997;26(1):2–14. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2601_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrell AD, Sullivan TN. Impact of witnessing violence on growth curves for problem behaviors among early adolescents in urban and rural settings. Journal of Community Psychology. 2004;32(5):505–525. [Google Scholar]

- Farrington DP. Developmental and life-course criminology: Key theoretical and empirical issues-the 2002 Sutherland Award address. Criminology. 2003;41(2):221–255. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Ormrod RK, Turner HA. The developmental epidemiology of childhood victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24(5):711–731. doi: 10.1177/0886260508317185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Ormrod RK, Hamby S. Violence, abuse, and crime exposure in a national sample of children and youth. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1411–1423. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster H, Brooks-Gunn J. Toward a stress process model of children's exposure to physical family and community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2009;12:71–94. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0049-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Rudenstine S, Vlahov D. Drug use, misuse, and the urban environment. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2005;24:127–136. doi: 10.1080/09595230500102509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL, Morris SZ, Beaver KM. Secondary exposure to violence during childhood and adolescence: Does neighborhood context matter? Justice Quarterly. 2009;26(1):30–57. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson CL, Sullivan CJ, Jones S, Piquero AR. “Does it take a village?” Assessing neighborhood influences on children's self control. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 2010;47(1):31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Gorman-Smith D, Henry DB, Tolan PH. Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: The protective effects of family functioning. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):439–449. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan J, Foster H. Youth violence and the end of adolescence. American Sociological Review. 2001;66(6):874–899. [Google Scholar]

- Hardaway CR, McLoyd VC, Wood D. Exposure to violence and socioemotional adjustment in low-income youth: An examination of protective factors. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2012;49:112–126. doi: 10.1007/s10464-011-9440-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay C, Evans MM. Violent victimization and involvement in delinquency: Examining predictions from general strain theory. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2006;34:261–274. [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Heeren T, Winter MR. Age at drinking onset and alcohol dependence: Age at onset, duration, and severity. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicing. 2006;160:739–746. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.7.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschi T. Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Huizinga D, Esbensen F-A, Weiher AW. Are there multiple paths to delinquency? The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology. 1991;82(1):83–118. [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Buka SL, Subramanian SV, Molnar BE. Neighborhood predictors of dating violence victimization and perpetration in young adulthood: A multilevel study. American Journal of Public Health. 2010;100:1737–1744. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.169730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Buka SL, Subramanian SV, Molnar BE. Protective factors for youth exposed to violence: Role of developmental assets in building emotional resilience. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice. 2012;10(1):107–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jain S, Cohen AK. Behavioral adaptation among youth exposed to community violence: A longitudinal multidisciplinary study of family, peer and neighborhood-level protective factors. Prevention Science. 2013;14(6):606–617. doi: 10.1007/s11121-012-0344-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Foshee VA, Ennett ST, Suchindran C. Sex differences in the effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and social organization on rural adolescents' aggression trajectories. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;43:189–203. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JM. Gendered responses to serious strain: The argument for a General Strain Theory of deviance. Justice Quarterly. 2009;26(3):410–444. doi: 10.1080/07418820802427866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R, Saunders BE, Resnick HS, Best CL, Schnurr PP. Risk factors for adolescent substance abuse and dependence: Data from a national sample. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(1):19–30. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk DS, Papachristos AV. Cultural mechanisms and the persistence of neighborhood violence. American Journal of Sociology. 2011;116(4):1190–1233. doi: 10.1086/655754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kliewer W, Murrelle L, Prom E, Ramirez M, Obando P, Sandi L, Karenkeris MdC. Violence exposure and drug use in Central American youth: Family cohesion and parental monitoring as protective factors. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2006;16(3):455–478. [Google Scholar]

- Kort-Butler LA. Experienced and vicarious victimization: Do social support and self-esteem prevent delinquent responses? Journal of Criminal Justice. 2010;38:496–505. [Google Scholar]

- Lauritsen JL. How families and communities influence youth victimization. Washington, D.C.: Office of Justice Programs: Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126(2):309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71(3):543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Goldstein A. Children's exposure to community violence: Implications for understanding risk and resilience. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33(3):499–505. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M. Consequences of children's exposure to community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003;6(4):265–274. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000006293.77143.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maimon D, Browning CR. Unstructured socializing, collective efficacy, and violent behavior among urban youth. Criminology. 2010;48(2):443–474. [Google Scholar]

- Maimon D, Browning CR. Underage drinking, alcohol sales and collective efficacy: Informal control and opportunity in the study of alcohol use. Social Science Research. 2012;41:977–990. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology. 2000;51:445–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin G, Gordis EB. Children's exposure to violence in the family and community. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2004;13(4):152–155. [Google Scholar]

- Marshal MP, Chassin L. Peer influence on adolescent alcohol use: The moderating role of parental support and discipline. Applied Developmental Science. 2000;4(2):80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. 2001;56(3):227–238. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course persistent anti-social behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychological Review. 1993;100(4):674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Cerda M, Roberts AL, Buka SL. Effects of neighborhood resources on aggressive and delinquent behaviors among urban youths. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(6):1086–1093. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar BE, Miller MJ, Azrael D, Buka SL. Neighborhood predictors of concealed firearm carrying among children and adolescents: Results from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods. Archives of Pediatric Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158:657–664. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.7.657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morenoff JD, Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW. Neighborhood inequality, collective efficacy, and the spatial dynamics of urban violence. Criminology. 2001;39(3):517–560. [Google Scholar]

- Musick K, Seltzer JA, Schwartz CR. Neighborhood norms and substance use among teens. Social Science Research. 2008;37:138–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Population estimates. Rockville, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- O'Donnell DA, Schwab-Stone M, Muyeed AZ. Multidimensional resilience in urban children exposed to community violence. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1265–1282. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osgood DW, Wilson JK, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Johnston LD. Routine activities and individual deviant behavior. American Sociological Review. 1996;61(4):635–655. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor LJ. Children growing up in a violent community: The role of the family. Aggression and Violent behavior. 2006;11:558–576. [Google Scholar]

- Rankin B, Quane JM. Social contexts and urban adolescent outcomes: The interrelated effects of neighborhoods, families, and peers on African-American youth. Social Problems. 2002;49(1):79–100. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS. Hierarchical linear model: Applications and data analysis methods. 2nd ed. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush SW, Bryk AS, Cheong YF, Congdon R, du Toit M. HLM 6: Hierarchical Linear and Nonlinear Modeling. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rosario M, Salzinger S, Feldman RS, Ng-Mak DS. Community violence exposure and delinquent behaviors among youth: The moderating role of coping. Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(5):489–512. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ. The community. In: Wilson JQ, Petersilia J, editors. Crime and public policy. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2011. pp. 210–236. [Google Scholar]