Abstract

The clp genes encoding the Clp proteolytic complex are widespread among living organisms. Five clpP genes are present in Streptomyces. Among them, the clpP1 clpP2 operon has been shown to be involved in the Streptomyces growth cycle, as a mutation blocked differentiation at the substrate mycelium step. Four Clp ATPases have been identified in Streptomyces coelicolor (ClpX and three ClpC proteins) which are potential partners of ClpP1 ClpP2. The clpC1 gene appears to be essential, since no mutant has yet been obtained. clpP1 clpP2 and clpC1 are important for Streptomyces growth, and a study of their regulation is reported here. The clpP3 clpP4 operon, which has been studied in Streptomyces lividans, is induced in a clpP1 mutant strain, and regulation of its expression is mediated via PopR, a transcriptional regulator. We report here studies of clgR, a paralogue of popR, in S. lividans. Gel mobility shift assays and DNase I footprinting indicate that ClgR binds not only to the clpP1 and clpC1 promoters, but also to the promoter of the Lon ATP-dependent protease gene and the clgR promoter itself. ClgR recognizes the motif GTTCGC-5N-GCG. In vivo, ClgR acts as an activator of clpC1 gene and clpP1 operon expression. Similarly to PopR, ClgR degradation might be ClpP dependent and could be mediated via recognition of the two carboxy-terminal alanine residues.

The temporally coordinated presence of various bacterial regulators has been shown to be essential for coordination of life cycle events (10), and this temporal control is often achieved via specific degradation (19) involving several proteins, including ATP-dependent proteases. Different families of ATP-dependent proteases have been characterized in bacteria: Clp (ClpAP and ClpXP), HslUV (ClpYQ), FtsH, and the Lon family (Lon). These proteases are large multisubunit complexes. The ATPase domains, which confer substrate specificity, denature and translocate substrates into the proteolytic chamber for degradation. The polypeptide chain Lon contains these two different activities on the same polypeptide chain. In contrast, Clp proteases contain two different subunits: the ATPase subunit (ClpX, ClpA, or ClpC) and the proteolytic subunit (ClpP), which contains a consensus serine protease active site (14).

clpP genes are generally present as single copies in eubacteria, but some organisms possess a multigenic clpP family. For example, two clpP genes are present in Bacillus thuringiensis (11) and in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, four genes are present in the cyanobacterium Synechococystis (32), and five genes are present in Streptomyces coelicolor. In S. coelicolor, the clpP genes are organized as two bicistronic operons and one monocistronic gene, all located at different sites on the chromosome. In S. coelicolor, there are three monocistronic clpC genes and one clpX gene, which follows the clpP1 operon. Streptomyces is the first genus with a multigenic clpC family that has been reported.

Streptomyces, a gram-positive soil bacterium with high G+C content, is a model of bacterial differentiation, since it undergoes a complex growth cycle. The spores germinate to produce a substrate mycelium, which then gives rise to differentiated aerial hyphae which septate to release spores. Mutants affected in different steps of the life cycle have been isolated and studied. Bald (bld) mutants are arrested at the substrate mycelium stage, and white (whi) mutants cannot produce grey-pigmented spores.

ATP-dependent proteases have been shown to be essential for cell cycle control in some bacteria: a clpXP mutant in Caulobacter crescentus is arrested in the cell cycle before the initiation of chromosome replication (18), ClpP plays an essential role in sporulation in Bacillus subtilis (25), and a lonD mutant in Myxococcus xanthus does not form spores (34). The role of the Lon and Clp proteases in the Streptomyces lividans differentiation cycle was investigated. The Lon protease does not seem to play a major role in Streptomyces differentiation (33), whereas the first clpP operon (clpP1 clpP2) has been shown to be required for a normal cell cycle, since a clpP1 mutant presents a bald phenotype (8).

lon and clp genes are subjected to multiple modes of regulation in eubacteria. In Escherichia coli, the clpP clpX operon is controlled by the vegetative sigma factor σ70 and the general heat shock sigma factor σ32 (21), while clpA is controlled only by σ70 and is not induced by heat shock (20). In gram-positive bacteria, different modes of regulation have been demonstrated, and most of them are stress dependent. In B. subtilis, the clp genes are all heat induced. The clpC operon and the clpP gene are controlled by the vegetative sigma factor σA and the CtsR repressor, which binds a heptanucleotide repeat that overlaps the −10 or −35 box (9), whereas the clpX gene is under the control of only the σA factor. In Streptococcus salivarius, clpP is negatively controlled by both CtsR and the HrcA repressor (6), which recognizes the CIRCE inverted-repeat operator sequence. However, in S. lividans, none of the clp genes is heat induced. Only the regulation of the second clpP operon (clpP3 clpP4) has been characterized. Expression of the clpP3 clpP4 operon is activated by PopR when the first operon (clpP1 clpP2) is nonfunctional (36). PopR is degraded by ClpP1 ClpP2, and the two carboxy-terminal alanine residues play an essential part in the degradation signal (35). In effect, the involvement of carboxy-terminal amino acid sequences in targeting proteins for degradation has been shown in the SsrA system, where the two C-terminal alanine residues are crucial for degradation by Clp proteases (16). lon gene regulation has not been as widely studied. In the model organisms E. coli and B. subtilis, lon is heat induced (7, 29). In S. lividans, lon is also heat induced, since it is repressed under non-heat shock conditions via the regulator HspR, which binds to the HspR-associated inverted repeat (HAIR) operator sequence (33).

We investigated clp gene regulation in S. lividans and found in the close relative S. coelicolor, whose genome sequence is available, a gene paralogous to popR which likely encodes a clp gene regulator. This gene, clgR, encodes a positive transcriptional regulator that binds to the clpP1 clpP2 operon and clpC1 gene promoters. We have determined the recognition sequence for the ClgR regulator and identified potential members of this regulon, including lon and clgR itself. Moreover, ClgR could be involved in Streptomyces differentiation, since the overexpression of clgR induces a differentiation delay in S. lividans. We report here the first regulon described in gram-positive bacteria that includes lon and clp genes, encoding two major cytoplasmic proteases.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and media.

S. lividans strain 1326 was obtained from the John Innes Culture Collection, and S. lividans 1326 clpP1::Amr was constructed in our laboratory (8). YEME medium (17) was used for liquid growth. NE (27) and R5 (17) media were used for Streptomyces growth on plates. The antibiotics apramycin and hygromycin were added at final concentrations of 25 and 100 μg ml−1 to solid medium and at 20 and 50 μg ml−1 to liquid medium, respectively.

E. coli TG1 (13) was used as the general cloning host, and E. coli BL21λDE3, containing the pREP4 plasmid (1), was used for protein production and purification. E. coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani medium. The antibiotics ampicillin and hygromycin were added at final concentrations of 100 μg ml−1.

DNA manipulation and transformation procedures.

Plasmid DNA was extracted from E. coli using a Qiagen kit. DNA fragments were purified from agarose gels with Ultrafree-DA filters (Amicon-Millipore). Restriction enzymes were used as recommended by the manufacturers. DNA fragments were amplified by the PCR technique (26, 30). DNA sequences were determined by the dideoxy chain termination method (31) using a modified T7 DNA polymerase (Pharmacia). Standard electroporation procedures were used for E. coli transformation.

Streptomyces DNA and protoplasts were prepared and transformed as described by Hopwood et al. (17).

Plasmids and plasmid constructions.

The E. coli vectors used were pUC19 (37) for cloning and pET28/16 (5), derived from pET28a (Novagen), for overproduction and purification of proteins. The Streptomyces-E. coli shuttle vector used was pHM11a, which allows strong expression from the constitutive ermp promoter and contains an integration element directing its insertion into the Streptomyces genome at the minicircle attachment site (24).

The transcription start site of clpC1 was localized by a sequencing reaction with the oligonucleotide used in primer extension, using plasmid pAB42. pAB42 consists of a 410-bp fragment including the S. lividans 1326 promoter region and the first 90 bp of the clpC1 gene obtained by PCR amplification with primers AB56 and AB57 (Table 1), treated with polynucleotide kinase, and inserted into the SmaI site of pUC19. The transcription start site of clgR was localized using plasmid pAB57, which consists of a 680-bp PCR product obtained by amplification with primers AB71 and AB72 inserted between the BamHI and HindIII sites of pUC19. The transcription start site of clpP1 was determined using pVDC702 (8). To overproduce ClgR, pET28/16clgR was constructed by inserting between the NdeI and HindIII sites of pET28/16 a 690-bp fragment including the S. lividans 1326 clgR coding sequence obtained by PCR amplification with primers AB76 and AB72. This allowed the creation of a translational fusion, adding six C-terminal His residues and placing expression of the gene under the control of a T7 promoter. To overexpress clgR in Streptomyces, pAB54 and pAB55 were constructed by inserting the 690-bp fragment including the coding sequence of the clgR gene obtained by PCR amplification with primers AB76 and AB72, or AB76 and AB73, respectively, between the NdeI and HindIII sites of pHM11a. The PCR fragment contained in pAB55 modified the clgR gene in order to encode two carboxy-terminal aspartic acid residues instead of two alanines.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Ju 26 | 5′ GTCGACCGGCTGGCCGAGG 3′ |

| Ju 70 | 5′ GGAGGATCCCCCGGCGACCGAGGCGATCAC 3′ |

| extlon | 5′ GTCGATGCGCGGGACGAGGAG 3′ |

| lon01 | 5′ GAGGAGCTCTACGGCGGTGCTGTCCCGAGA 3′ |

| AB16 | 5′ CGTGCGCTCGGTGAACTCCGGCAGGACATG 3′ |

| AB18 | 5′ GGTGGTGGCCACGTCGCAGGCGACGTA 3′ |

| AB56 | 5′ TGTGCTCGGTGCCGATGTAGTTGTGGTTGA 3′ |

| AB57 | 5′ TCTTCTAGAGGAGGCGCAAGGTTGTTCGCC 3′ |

| AB71 | 5′ GGAGGATCCGGCCCTTCAGGGCCGAGCAGG 3′ |

| AB72 | 5′ AAGAAGCTTGGGCGCTCAGGCGGCGACGAC 3′ |

| AB73 | 5′ AAGAAGCTTTCAGTCGTCGACGACGTCCAC 3′ |

| AB76 | 5′ CATCATATGATTCTGCTCCGTCGCCTGCTG 3′ |

| AB77 | 5′ CATCATATGACCCGGCCGTCAGCCCGC 3′ |

| AB78 | 5′ AGTACGGCCCTGGCGTTGGCGCTG 3′ |

| AB84 | 5′ CAGGACAGCCCGCCCAGGGGCGCGGGGAAC 3′ |

| AB86 | 5′ CAGGACAGCCCGCCCAGGGGCGCGGGGAAC 3′ |

| AB87 | 5′ ACCATGCCAAGTGCAACAGTCGAAAGAGCG 3′ |

| AB88 | 5′ ACTTCCCCTCCCTGTCCTTCCGCAGCTTAG 3′ |

| AB89 | 5′ TACGGCGGTGCTGTCCCGAGAGGC 3′ |

| AB94 | 5′ GTGTACAGAGCGTACTCGCACTTC 3′ |

| AB100 | 5′ CGCGGTCGGTGAACCTCTCGAACA 3′ |

| AB101 | 5′ CGTATCCACCTGCTCGTCTTACGA 3′ |

RNA extraction.

Ten to 15 ml of an S. lividans 1326 culture with or without the pHM11a (control), pAB54, or pAB55 plasmid was pelleted. The cells were resuspended in 0.5 ml of cold deionized water and added to 0.5 g of glass beads (106-μm diameter; Sigma), 0.4 ml of 4% Bentone (Rheox), and 0.5 ml of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol, pH 8.0 (Amresco). The cells were disrupted in a Fastprep disintegrator (Bio 101, Inc.) for 30 s at 4°C. After centrifugation for 2 min at 4°C and 20,800 × g, the supernatants were collected and treated with phenol-chloroform (1:1 [vol/vol]) and then with chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1 [vol/vol]). RNA was precipitated at −20°C with 850 μl of isopropanol in the presence of 0.2 M NaCl and resuspended in 20 μl of cold deionized water. The RNA concentrations were determined by measuring absorbance at 260 nm.

Primer extension experiments.

To determine clpC1 and clgR transcription start sites, primer extensions were performed as previously described (36) with the purified oligodeoxynucleotides AB56 and AB78 (Table 1) on 40 μg of clpC1 and clgR mRNAs, respectively. To analyze the transcription expression of clpP1 and clpC1, the Super Script II RNase H Reverse Transcriptase kit (Invitrogen) was used following the manufacturer's protocol. The purified oligodeoxynucleotides AB101 and AB100 (Table 1) were used on 20 μg of clpP1 and clpC1 mRNAs, respectively. The reactions were stopped by adding 5 μl of a loading solution containing 97.5% deionized formamide, 10 mM EDTA, 0.3% xylene cyanol, and 3.3% bromophenol blue. Samples were loaded on 6% acrylamide- urea sequencing gels.

Overproduction and purification of ClgR.

pET28/16clgR containing the translational fusion clgR-His6 under the control of the T7 promoter was introduced into E. coli strain BL21λDE3 carrying the plasmid pRep4 (1), which carries the groESL operon. This operon encodes chaperone proteins, which help to prevent aggregate formation in the cell. The resulting strain was grown at 30°C in Luria-Bertani medium containing 25 μg of kanamycin ml−1 until the culture reached an optical density at 600 nm of 0.9; isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside was then added to a final concentration of 1 mM. Incubation was pursued for 6 h at room temperature. The cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 10,800 × g, and the pellet was resuspended in 1/50 of the culture volume of buffer 1 (50 mM NaPO4, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole). The cells were disrupted by sonication, and the cell debris was pelleted by centrifugation for 20 min at 17,200 × g. The crude E. coli extract was loaded on a 100-μl Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose (Qiagen) column previously equilibrated with buffer 1. The column was abundantly washed with buffer 2 (50 mM NaPO4, pH 6, 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole), and the ClgR protein was eluted with an imidazole gradient (30 to 500 mM) and analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in a 12.5% acrylamide gel. The eluted product was dialyzed overnight at 4°C in 50% glycerol- 50 mM NaPO4 (pH 6.5)-300 mM NaCl. Total or purified protein extracts were resolved by SDS- 15% PAGE (22). The protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method (4).

Gel mobility shift DNA binding assays.

A 390-bp DNA fragment corresponding to the clpP1 promoter region was amplified by PCR, using Pfu polymerase (Stratagene) with primers AB84 and Ju26 (Table 1). The promoter regions of clpC1 (440 bp with AB56 and AB57), lon (330 bp with extlon and lon01), clgR (270 bp with AB78 and AB94), and clpP5 (360 bp with Ju70 and AB16) were also amplified. Twenty picomoles of each primer was used, and one of the primers was purified and previously labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase (New England Biolabs) and [γ-32P]dATP. Radiolabeled fragments (10,000 cpm) and various quantities of ClgR from 0 to 200 ng were incubated for 20 min at room temperature in a 10-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μg of calf thymus (nonspecific competitor) DNA and the reaction buffer (25 mM NaPO4, pH 7, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol). Samples were then loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide gel (50 mM Tris, 400 mM glycine, 1.73 mM EDTA), and electrophoresis was performed at 14 V cm−1 for 1 h.

DNase I footprint.

DNA fragments prepared by PCR and used for gel mobility shift DNA binding assays were used for DNase I footprinting reactions. In a final volume of 50 μl, ClgR (0 to 1 μg) and end-labeled fragments (50,000 cpm) were incubated for 20 min at room temperature in the presence of 5 μg of poly(dI-dC), 1 μg of bovine serum albumin, and 1× reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM dithiothreitol, 4% glycerol). Five microliters of 10 mM MgCl2 and 5 mM CaCl2 were then added, followed by 5 ng of DNase I (Worthington Biochemical). After incubation for 1 min at room temperature, the reaction was stopped with 140 μl of stop buffer (0.4 M sodium acetate, pH 6.7, 2.5 mM EDTA, 50 μg of calf thymus DNA ml−1). The DNA was precipitated with ethanol, resuspended in the loading solution, and subjected to electrophoresis as described above for primer extensions. A+G Maxam-and-Gilbert reactions (23) were carried out on the appropriate 32P-labeled DNA fragments and loaded alongside the DNase I footprinting reactions. The gels were dried and analyzed by autoradiography.

Protein extraction and Western blotting experiments.

Cultures of S. lividans 1326 carrying pHM11a (control), pAB54, or pAB55 were grown on cellophane disks laid down on the surfaces of solid NE plates. Proteins were prepared from mycelia of the different strains at regular intervals during growth (24, 48, and 72 h). Mycelia were resuspended in the sonication buffer (20 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) and lysed by sonication. The resulting suspension was centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C and 20,800 × g, and the supernatant was treated with 0.3% SDS for 5 min at 85°C. The sample was centrifuged for 15 min at 4°C, and the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined by the method of Bradford (4). Ten micrograms of protein extract was subjected to SDS-PAGE (22). The proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Hybond C), which was then probed with rabbit polyclonal anti-Streptomyces ClpP1 (1:10,000), anti-recombinant Synechococcus ClpC (1:1,000) (Agrisera), or anti-Streptomyces Lon (1:5,000). Signals were detected with the ECL Western Blotting Detection kit (Amersham Biosciences).

RESULTS

A popR paralogue in S. lividans.

Analysis of the recently completed S. coelicolor genome sequence (3) showed a gene paralogous to popR, which could be responsible for regulation of other clp genes. The encoded protein, which is 126 amino acids long, has 24% identity with PopR, with 62% identity in the central key region of 60 amino acids. Recently, S. Schaffer (Institute of Biotechnology, Julich, Germany) (personal communication) has shown the regulation in Corynebacterium glutamicum of clpP and clpC by a gene orthologous to this popR paralogue. He coined the designation clgR (for clp gene regulator) for the gene. Since we show here that this regulator controls the clp and lon genes, we decided to keep the name ClgR, for clp and lon gene regulator.

We attempted to construct a strain with a clgR mutation, using a cosmid which contains the clgR gene interrupted by a viomycin cassette. However, despite the large regions flanking the gene and several attempts, only single recombinants have been obtained, suggesting that ClgR or one of the genes that it controls may be essential.

Interestingly, ClgR, like PopR, has two alanine residues at its C terminus. It was previously shown that these residues are critical for PopR degradation by ClpP (35). A similar phenomenon may be involved for ClgR. A construction, used in the subsequent experiments, was made to replace the two alanines with two aspartates. Genes encoding this modified ClgR, named clgR-DD, and the native ClgR, clgR-AA, were cloned into the integrative vector pHM11a under the control of the strong ermp promoter, giving pAB55 and pAB54, respectively.

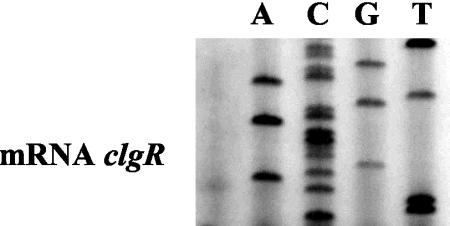

To determine whether clgR is expressed in the wild-type strain, primer extension analysis was performed (Fig. 1). A transcription start point was detected, using mRNAs extracted from the S. lividans wild-type strain, 39 bp upstream from the clgR translation initiation codon. The −10 TACGGT box perfectly matched the −10 consensus motif, TA(G/C)(G/C/A)(G/T)T, recognized by the major sigma factor HrdB, but no consensus sequences could be identified in the −35 region.

FIG. 1.

Primer extension analysis of clgR transcription. Total RNA (40 μg) isolated from the wild-type S. lividans strain was used as a template for reverse transcriptase. The corresponding DNA sequencing reaction is shown on the right.

Purified ClgR of S. lividans binds specifically to regions upstream of the clpP1 operon and the clpC1 gene.

In order to determine whether ClgR binds to promoter regions of clp genes, an in vitro approach was used.

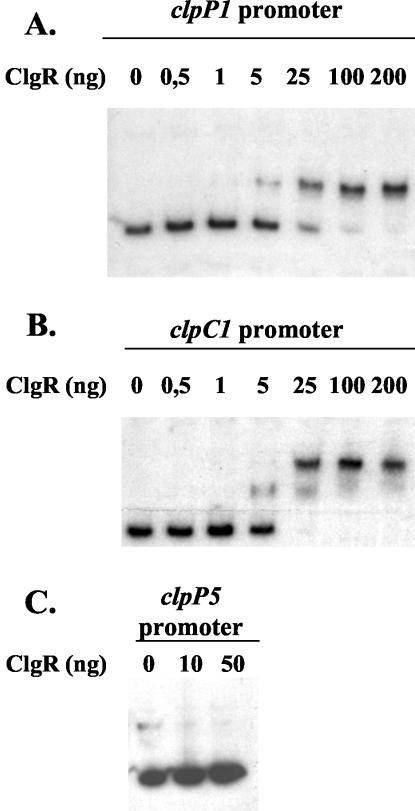

The S. lividans ClgR protein was overproduced and purified using the plasmid pET28/16. ClgR was used in gel mobility shift DNA binding assays with radiolabeled DNA fragments corresponding to the promoter regions of the clpP1 clpP2 operon and the clpC1 and clpP5 genes in the presence of an excess of nonspecific competitor DNA. These DNA fragments were generated by PCR with oligonucleotides AB86/Ju26, AB87/AB88, and Ju70/AB16, respectively. ClgR binds specifically to the clpP1 and clpC1 promoters, forming a single complex with the clpP1 promoter region (Fig. 2A) and two protein-DNA complexes with the clpC1 DNA fragment (Fig. 2B). No difference in migration was observed when the upstream region of clpP5 was incubated with the same quantity of protein (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Specific binding of ClgR to the clpP1 and clpC1 promoter regions. Gel mobility shift experiments were performed by incubating 0 to 200 ng of purified ClgR with radiolabeled DNA fragments (10,000 cpm) corresponding to the promoter regions of the clpP1 operon (A), the clpC1 gene (B), and the clpP5 gene (C).

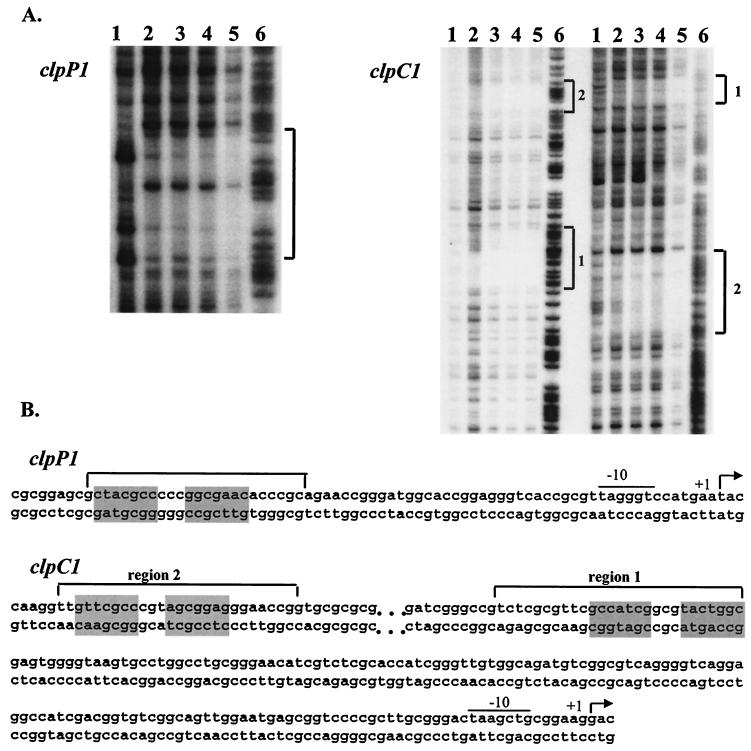

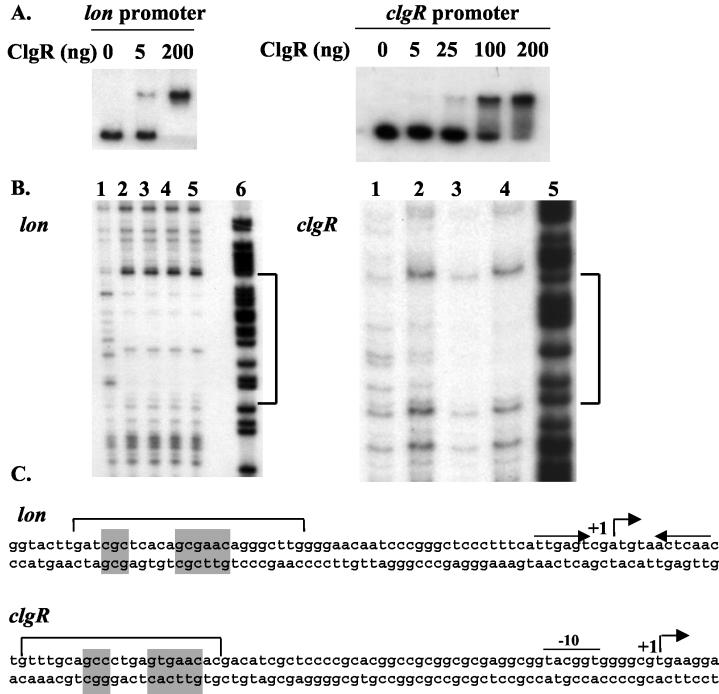

DNase I footprint assays were then performed in order to precisely determine the locations and sequences of the ClgR binding sites. As shown in Fig. 3A, when the nontemplate strand was end labeled, ClgR protected a region from positions −46 to −69 for clpP1 (FIG. 3A). For the clpC1 promoter region, ClgR protected regions from −145 to −171 (region 1) and from −248 to −273 (region 2) on the template and nontemplate strands (Fig. 3A). The positions are given with respect to the major transcription start site (the clpC1 transcription start site has been determined by primer extension [Fig. 4 ]). In the clpP1 promoter and region 1 of clpC1, the regions protected by ClgR both contain the partially inverted repeat GTTCGCC-3N-GGCGTA(C/G). Region 2 of clpC1 contains a similar motif, with two mismatches (underlined): GTTCGCC-3N-AGCGGAG.

FIG. 3.

DNase I footprinting analysis of ClgR binding to the clpP1 operon and clpC1 promoter regions. (A) Radiolabeled DNA fragment (50,000 cpm) corresponding to the nontemplate strand of the clpP1 promoter, the template strand (left) and the nontemplate strand (right) of the clpC1 promoter were incubated with increasing amounts of purified ClgR as follows: for clpP1, lanes 1 to 5, 0, 0.1, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg of ClgR, respectively; for clpC1, lanes 1 to 5, 0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, and 1 μg of ClgR, respectively; lanes 6, G+A Maxam-and-Gilbert reactions of the corresponding DNA fragments. Regions protected by ClgR are indicated by brackets. (B) Nucleotide sequences of the clpP1 and clpC1 promoter regions. Consensus −10 sequences are indicated by lines; transcriptional start points are indicated by +1; regions protected in DNase I footprinting experiments by ClgR are indicated by brackets; ClgR consensus motifs are shaded.

FIG. 4.

Primer extension analysis of clpC1 transcription. Total RNA (40 μg) isolated from the wild-type (WT) S. lividans strain was used as a template for reverse transcriptase. The corresponding DNA sequencing reaction is shown on the left.

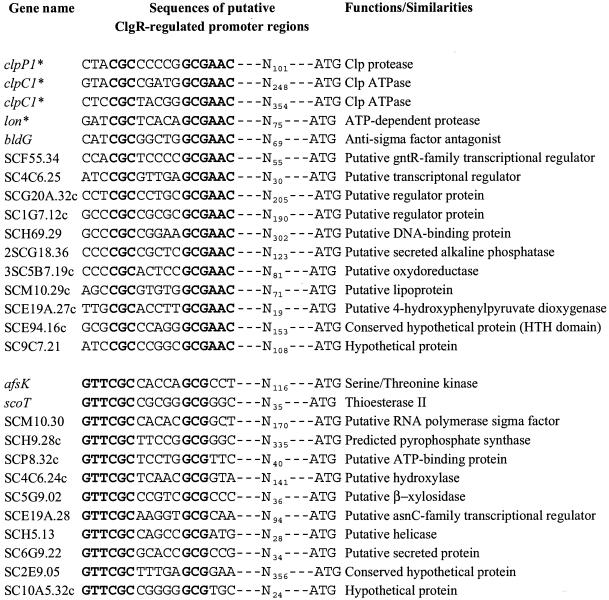

Using a restricted consensus from these three motifs, GTTCGC-5N-GCG, an extensive DNA motif analysis of the complete S. coelicolor genome was performed to identify likely target genes belonging to the ClgR regulon. For this purpose, we used the “pattern search” function on the S. coelicolor web server (http://jiio16.jic.bbsrc.ac.uk/S.coelicolor/). Twenty-seven genes (including clpP1 and clpC1) were found to have this specific sequence on either strand in the intergenic regions within the 400-bp region upstream from the translation initiation codon while excluding those located between convergent genes (Fig. 5). Many of these genes have only putative functions, and four of them encode regulator proteins. One of these genes is lon, encoding the Lon ATP-dependent protease, which has been studied in the laboratory. We therefore investigated the possible regulation of lon by ClgR.

FIG. 5.

Alignment of nucleotide sequences of putative ClgR-regulated promoter regions. Genes for which direct binding by ClgR was shown are indicated by asterisks.

Purified ClgR of S. lividans binds specifically to upstream regions of the lon and clgR genes.

In order to confirm binding of ClgR in the lon promoter region, gel mobility shift DNA binding assays were performed on a 330-bp DNA fragment carrying the lon promoter region generated by PCR with oligonucleotides AB89 and extlon. The purified ClgR protein binds specifically, forming one major protein-DNA complex with the lon DNA fragment (Fig. 5A). To precisely determine the location and sequence of the ClgR binding site, DNase I footprinting assays were performed. As shown in Fig. 6B, ClgR protects a region of the nontemplate strand extending from positions −33 to −58 relative to the transcription initiation start site, which had been determined previously (33). As expected, this region contains the motif GTTCGC-5N-GCG (Fig. 6C).

FIG. 6.

ClgR binds specifically to the lon and clgR promoter regions. (A) Gel mobility shift experiments were performed by incubating 0 to 200 ng of purified ClgR with radiolabeled DNA fragments (10,000 cpm) corresponding to the promoter regions of lon and clgR. (B) Radiolabeled DNA fragments (50,000 cpm) corresponding to the nontemplate strand of the lon promoter and the template strand of the clgR promoter were incubated with increasing amounts of purified ClgR as follows: for lon, lanes 1 to 5, 0, 25, 50, 100, and 500 ng of ClgR, respectively; for clgR, lanes 1 to 4, 0, 0.05, 0.1, and 1 μg of ClgR, respectively; lane 6 for lon and lane 5 for clgR, G+A Maxam-and-Gilbert reactions of the corresponding DNA fragments. The regions protected by ClgR are indicated by brackets. (C) Nucleotide sequences of the lon and clgR promoter regions. Consensus −10 sequences are indicated by lines; transcriptional start points are indicated by +1; regions protected in DNase I footprinting experiments by ClgR are indicated by brackets; ClgR consensus motifs are shaded. The HspR double-inverted repeat recognition target is indicated by inverted arrows in the lon sequence.

To test possible autoregulation of clgR, similar experiments were carried out. Migration at a higher-molecular-weight complex was observed when the 270-bp fragment containing the clgR promoter, generated by PCR with oligonucleotides AB94 and AB78, was incubated with 200 ng of purified ClgR protein (Fig. 5A). DNase I footprinting assays allowed determination of the ClgR binding site. The protected region on the template strand extends from positions −47 to −69 (Fig. 5B). This region contains a degenerate ClgR binding motif, GTTCAC-5N-GC (Fig. 6C).

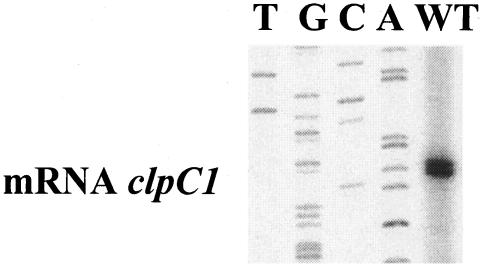

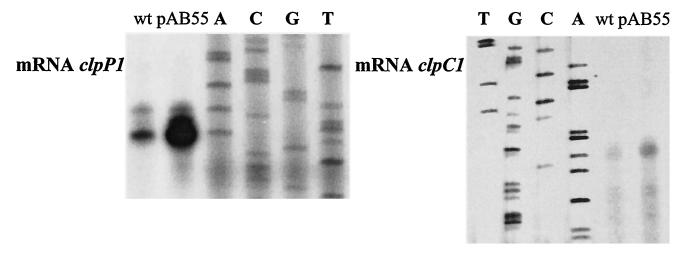

ClgR activates expression of the clpP1 operon and the clpC1 gene.

To examine whether ClgR is an activator, clpP1 clpP2 operon and clpC1 gene expression was assessed by primer extension analysis in S. lividans strains overexpressing clgR. mRNAs extracted from cultures of the strains harboring pHM11a (control) and pAB55, which express the modified form of ClgR (ClgR-DD) in order to increase the potential effect of ClgR, were used. A strong signal was detected for clpP1 clpP2 and clpC1 expression with mRNAs extracted from the pAB55 strain (Fig. 7). The signal was weaker with mRNAs extracted from the wild-type strain. This indicates that ClgR acts as an activator.

FIG. 7.

Primer extension analysis of clpP1 and clpC1 transcription. Total RNA (20 μg) isolated from the wild-type (wt) S. lividans strain carrying pHM11a (control) or pAB55 was used as a template for reverse transcriptase. The corresponding DNA sequencing reactions are shown.

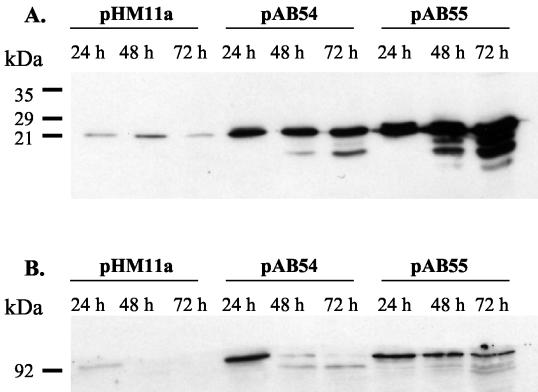

Evidence of regulation by ClgR at the protein level.

Strains harboring pHM11a, pAB54, and pAB55 were analyzed by Western blot experiments with polyclonal anti-S. lividans ClpP1 antibodies and anti-Synechococcus ClpC antibodies. The protein extracts were prepared from plate cultures at 24, 48, and 72 h of development.

In the wild-type strain, a signal was detected at ∼23 kDa with anti-ClpP1 antibodies. This signal corresponds to the processed form of ClpP1 (35); a higher-molecular-weight signal corresponding to the unprocessed form of ClpP1 can be detected with longer exposure. This signal is of the same intensity at each time point (Fig. 8A). In strains overexpressing clgR-AA, the signal is much stronger than in the wild type. New signals of smaller sizes appear; these bands probably correspond to degradation products of ClpP1, which accumulate during this time. In strains overexpressing clgR-DD, the differences in ClpP1 levels compared to the wild-type strain are even greater.

FIG. 8.

Detection of ClpP1 and ClpC1 by Western blotting. Crude extracts (10 μg) from cultures on plates with 24-, 48-, and 72-h cultures of the wild-type S. lividans strain carrying pHM11a (control), pAB54, and pAB55 were analyzed by Western blotting with anti-ClpP1 antibodies (A) and anti-ClpC (Synechococcus ClpC) antibodies (B).

ClpC levels were determined with antibodies raised against a 13-amino-acid epitope of Synechococcus ClpC present in ClpC1 but not in the other Streptomyces Clp proteins. The detected signal is ∼90 kDa and likely corresponds to the ClpC1 protein (Fig. 8B). Unlike ClpP1, the ClpC1 signal is not the same during growth. The signal is visible at 24 h but disappears at 48 and 72 h. In the strains harboring pAB54 (clgR-AA), the detected signals are much stronger than in the wild type. ClpC1 levels are high at 24 h and are still present at 48 h but almost completely disappear by 72 h. In strains harboring pAB55 (clgR-DD), the signal for ClpC1 is detected from 24 to 72 h with about the same intensity.

Effects of overproduction of the ClgR regulator on Streptomyces differentiation.

Since the clpP1 clp2 operon plays a role in Streptomyces differentiation, we tested the effect of ClgR by constructing strains overexpressing clgR.

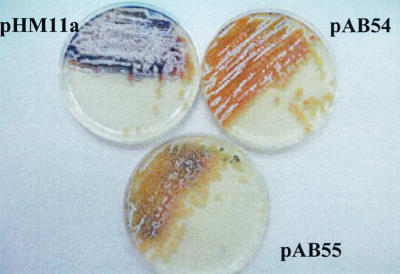

Phenotypes of the wild-type strain harboring pHM11a (control vector), pAB54 (clgR-AA), or pAB55 (clgR-DD) were examined on R5 rich medium. As shown in Fig. 8, the wild-type strain completely sporulated after 10 days, whereas the strain harboring pAB54 (clgR-AA) was only starting to form aerial mycelia. This differentiation delay is even stronger in the strain harboring pAB55 (clgR-DD) (Fig. 9), suggesting that increased levels of ClgR delay differentiation.

FIG. 9.

Phenotypes of wild-type S. lividans carrying plasmid pHM11a (control), pAB54 (clgR-AA), or pAB55 (clgR-DD) on R5 plates after 10 days of growth.

DISCUSSION

We report here the identification of a new regulator for ATP-dependent protease clp and lon gene expression in Streptomyces. We have determined a conserved sequence for the binding region of ClgR on the promoters, and we have also shown some in vivo experiments that provide evidence that this regulatory system is functional in Streptomyces. The activator, ClgR, is encoded by a monocistronic gene.

The ClgR protein directly binds an imperfect palindromic motif. Considering the clpP1, clpC1, and lon regions protected in DNase I footprinting experiments, the deduced consensus sequence is 5′-GTTCGCY-3N-RGCG G/T/AA/TG/C-3′. According to in vitro experiments, ClgR could be autoregulated. The defined motif for the clgR promoter is a little bit divergent from this consensus. The Streptomyces avermitilis genome sequence (http://avermitilis.ls.kitasato-u.ac.jp/) also reveals a clgR gene, as well as the recognition sequence upstream from the clpC1 (both motifs) and lon genes. However, this motif could not be found in the clpP1 upstream region. This regulatory system seems to be widespread among actinomycetes, since ClgR is present in Mycobacterium and the motif is present upstream from the clpP1 and clpC genes. The M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium leprae genomes do not contain lon genes, but Mycobacterium smegmatis does, and its genome presents the ClgR motif upstream from lon. In Corynebacterium glutamicum, ClgR regulates several genes in the genome, such as clpP1 and clpC, but not the lon gene (S. Schaffer, personal communication).

According to the DNase I footprinting assays, it appears that the ClgR binding sites can be located in various positions: overlapping the −35 element (lon), around the −50 region (clpP1 and clgR), or far upstream from the transcription start site (clpC1, which has two motifs, one in the −150 region and one in the −250 region). Because of these different site localizations, we can hypothesize that ClgR activates expression either by making direct contacts with RNA polymerase or by altering the promoter conformation (28). Moreover, binding of ClgR may induce bending of the DNA, since several enhanced DNase I cleavage sites appear within the protected regions of the promoters of the clpP1 gene (Fig. 3A) and the lon gene (Fig. 6B). However, we cannot exclude the possibility that there is a second transcription start site for the clpC1 promoter upstream from the first, close to the identified ClgR motifs but undetected under our conditions. However, in transcription analysis by primer extension, the mapped transcription start sites for clpP1 and clpC1 are those induced in strains overexpressing clgR-DD (Fig. 6).

ClgR regulates not only clp gene expression but also that of lon, the gene encoding the other major cytoplasmic ATP-dependent protease. This indicates that lon has double regulation in S. lividans. In effect, while it had been shown that lon expression is repressed at normal growth temperatures by the binding of HspR on the HAIR motif, which contains the transcription initiation start site (33), it is shown here to be activated by ClgR, which binds a region 50 bp upstream from the transcription initiation site. We have not determined if the two regulators can bind simultaneously, as has been shown for the simultaneous binding of both CtsR and HrcA to the Staphylococcus aureus dnaK and groESL promoter regions (5). We could hypothesize that binding of HspR may exclude ClgR binding, which would explain why no effects of clgR overexpression on lon expression could be detected under the conditions we tested. As with the groESL operon in C. crescentus, which is under the control of the heat shock sigma factor and the cell cycle-dependent HrcA regulator (2), lon expression could be both induced by heat shock and temporally controlled during the cell cycle by ClgR. Even if Lon has not been shown to be essential for the cell cycle, ClgR could induce Lon synthesis at a specific time for global degradation.

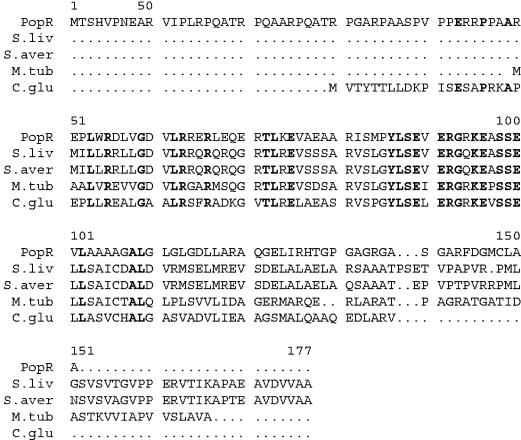

There are very strong similarities between ClgR and PopR, with 62% identity in the central key region containing the helix-turn-helix XRE family motif, even though PopR has a specific 50-amino-acid N-terminal extension (Fig. 10). S. coelicolor ClgR and S. avermitilis ClgR show 93% sequence identity, and both end with two alanine residues like PopR. Degradation of PopR by ClpP1 ClpP2 or ClpP3 ClpP4 requires the C-terminal Ala-Ala residues (35), as has also been shown for many Clp substrates in E. coli (16). As shown in Fig. 10, M. tuberculosis ClgR ends with one valine and one alanine, which may also be a recognition signal for the Clp protease, as the transcriptional regulator Fnr ends with Val and Ala and is degraded by ClpXP in E. coli (12). We assumed that ClgR might also be degraded by ClpP and that the two C-terminal alanines would be involved. Expression of the clpP1 operon and the clpC1 gene was increased in the presence of ClgR-DD compared to native ClgR. However, further investigation of ClgR degradation is required. It is interesting that C. glutamicum ClgR ends with one arginine and one valine (Fig. 10), which is not described as a C-terminal recognition signal for Clp protease. This suggests that if ClgR is also degraded in C. glutamicum, signaling for its degradation does not involve the same recognition signals among actinomycetes.

FIG. 10.

Alignment of PopR and ClgR amino acid sequences of S. lividans (S. liv) with those of S. avermitilis (S. aver), M. tuberculosis (M. tub), and C. glutamicum (C. glu). Conserved amino acids are shown in boldface.

ClgR-AA and ClgR-DD effects are obvious on ClpP1 immunoblots (Fig. 8), where ClpP1 production, which is constant through the differentiation cycle, is drastically increased in the pAB54 strain and even more in the pAB55 strain. For the ClpC1 protein, it is not as clear. In the wild type, ClpC1 is detectable only at the beginning of the life cycle, so clpC1 has a temporal regulation that differs from that of clpP1. In the pAB54 strain, ClpC1 is overproduced, but the signal decreases over time. Since clgR is expressed from the ermp constitutive promoter, clpC1 should be activated throughout growth. To explain ClpC1 disappearance, it probably undergoes a specific degradation that starts at 48 h of culture on plates. In the pAB55 strain, the detected signal is of the same intensity from 24 to 72 h, suggesting that the activation of clpC1 expression by ClgR-DD is probably counterbalanced by the specific degradation of ClpC1, which leads to a constant level. It could be possible that ClpC1 is itself a substrate of Clp-dependent degradation, as is the case for ClpA in E. coli (15). Another hypothesis could be that ClgR is degraded after 24 h and that ClpP1 is more stable than ClpC1. Therefore, clpP1 and clpC1 would be specifically activated at the beginning of the growth cycle. This would explain why the ClpP1 level is constant through the differentiation cycle but the protein does not accumulate and why ClpC1 is detectable only at 24 h.

Overexpression of clgR also causes a differentiation delay. It is interesting that concomitantly overexpressing clpP1 clpP2, clpC1, and lon genes provokes a delay in differentiation, whereas overexpressing only the clpP1 operon accelerates aerial-mycelium formation (8). This suggests that an imbalance between proteolytic and ATPase subunits has a different effect on the cell than a global increase of the ClpCP protease subunits.

Because of the crucial role of ClpP1 in differentiation, it would be interesting to elucidate the physiological role of ClgR. The hypothesis that ClgR autoactivates its own synthesis implies the existence of an additional control mechanism for this positive-feedback loop. This could suggest that once ClgR synthesis is arrested, PopR would be stabilized, since clpP1 clpP2 expression drops and this would consequently end clpP3 clpP4 operon expression. We have not yet determined under which conditions or at which step of the life cycle ClgR regulation is induced. Unlike what is reported for most other bacterial species, clp genes are not heat induced in Streptomyces. However, clp genes might be induced in response to a still-uncharacterized signal. A clgR mutant has not been obtained despite several attempts, whereas the clpP1 and lon mutants are viable. However, since clpC1 is thought to be essential (unpublished data), we will attempt to construct a clgR mutant in a background constitutively expressing clpC1 under the control of an unregulated promoter.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to J. Viala, A. Chastanet, and T. Msadek for their advice and help and for fruitful discussions.

This work was supported by research funds from the Institut Pasteur and Centre National de Recherche Scientifique. A.B. was the recipient of a fellowship from the Ministère de l'Education Nationale, de la Recherche et de la Technologie.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amrein, K. E., B. Takacs, M. Stieger, J. Molnos, N. A. Flint, and P. Burn. 1995. Purification and characterization of recombinant human p50csk protein-tyrosine kinase from an Escherichia coli expression system overproducing the bacterial chaperones GroES and GroEL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92:1048-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baldini, R. L., M. Avedissian, and S. L. Gomes. 1998. The CIRCE element and its putative repressor control cell cycle expression of the Caulobacter crescentus groESL operon. J. Bacteriol. 180:1632-1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bentley, S. D., K. F. Chater, A. M. Cerdeno-Tarraga, G. L. Challis, N. R. Thomson, K. D. James, D. E. Harris, M. A. Quail, H. Kieser, D. Harper, A. Bateman, S. Brown, G. Chandra, C. W. Chen, M. Collins, A. Cronin, A. Fraser, A. Goble, J. Hidalgo, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, C. H. Huang, T. Kieser, L. Larke, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, E. Rabbinowitsch, M. A. Rajandream, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, D. Saunders, S. Sharp, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Taylor, T. Warren, A. Wietzorrek, J. Woodward, B. G. Barrell, J. Parkhill, and D. A. Hopwood. 2002. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature 417:141-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford, M. 1976. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72:248-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chastanet, A., J. Fert, and T. Msadek. 2003. Comparative genomics reveal novel heat shock regulatory mechanisms in Staphylococcus aureus and other Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 47:1061-1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chastanet, A., and T. Msadek. 2003. ClpP of Streptococcus salivarius is a novel member of the dually regulated class of stress response genes in gram-positive bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 185:683-687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chin, D. T., S. A. Goff, T. Webster, T. Smith, and A. L. Goldberg. 1988. Sequence of the lon gene in Escherichia coli. A heat-shock gene which encodes the ATP-dependent protease LA. J. Biol. Chem. 263:11718-11728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.De Crecy-Lagard, V., P. Servant-Moisson, J. Viala, C. Grandvalet, and P. Mazodier. 1999. Alteration of the synthesis of the Clp ATP-dependent protease affects morphological and physiological differentiation in Streptomyces. Mol. Microbiol. 32:505-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derré, I., G. Rapoport, and T. Msadek. 1999. CtsR, a novel regulator of stress and heat shock response, controls clp and molecular chaperone gene expression in Gram-positive bacteria. Mol. Microbiol. 31:117-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Domian, I. J., A. Reisenauer, and L. Shapiro. 1999. Feedback control of a master bacterial cell-cycle regulator. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:6648-6653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fedhila, S., T. Msadek, P. Nel, and D. Lereclus. 2002. Distinct clpP genes control specific adaptive responses in Bacillus thuringiensis. J. Bacteriol. 184:5554-5562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flynn, J. M., S. B. Neher, Y. I. Kim, R. T. Sauer, and T. A. Baker. 2003. Proteomic discovery of cellular substrates of the ClpXP protease reveals five classes of ClpX-recognition signals. Mol. Cell 11:671-683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gibson, T. J. 1984. Studies on the Epstein-Barr virus genome. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge University, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

- 14.Gottesman, S. 1996. Proteases and their targets in Escherichia coli. Annu. Rev. Genet. 30:465-506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gottesman, S., W. P. Clark, and M. R. Maurizi. 1990. The ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. Sequence of clpA and identification of a Clp-specific substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 265:7886-7893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gottesman, S., E. Roche, Y. Zhou, and R. T. Sauer. 1998. The ClpXP and ClpAP proteases degrade proteins with carboxy-terminal peptide tails added by the SsrA-tagging system. Genes Dev. 12:1338-1347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hopwood, D. A., M. J. Bibb, K. F. Chater, T. Kieser, C. J. Bruton, H. M. Kieser, D. J. Lydiate, C. P. Smith, J. M. Ward, and H. Schrempf. 1985. Genetic manipulation of Streptomyces. A laboratory manual. The John Innes Foundation, Norwich, United Kingdom.

- 18.Jenal, U., and T. Fuchs. 1998. An essential protease involved in bacterial cell-cycle control. EMBO J. 17:5658-5669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jenal, U., and L. Shapiro. 1996. Cell cycle-controlled proteolysis of a flagellar motor protein that is asymmetrically distributed in the Caulobacter predivisional cell. EMBO J. 15:2393-2406. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katayama, Y., S. Gottesman, J. Pumphrey, S. Rudikoff, W. P. Clark, and M. R. Maurizi. 1988. The two-component, ATP-dependent Clp protease of Escherichia coli. Purification, cloning, and mutational analysis of the ATP-binding component. J. Biol. Chem. 263:15226-15236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kroh, H. E., and L. D. Simon. 1990. The ClpP component of Clp protease is the sigma 32-dependent heat shock protein F21.5. J. Bacteriol. 172:6026-6034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli, U. K. 1970. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 227:680-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maxam, A. M., and W. Gilbert. 1980. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 65:499-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Motamedi, H., A. Shafiee, and S.-J. Cai. 1995. Integrative vectors for heterologous gene expression in Streptomyces spp. Gene 160:25-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Msadek, T., V. Dartois, F. Kunst, M. L. Herbaud, F. Denizot, and G. Rapoport. 1998. ClpP of Bacillus subtilis is required for competence development, motility, degradative enzyme synthesis, growth at high temperature and sporulation. Mol. Microbiol. 27:899-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mullis, K. B., and F. A. Faloona. 1987. Specific synthesis of DNA in vitro via a polymerase-catalyzed chain reaction. Methods Enzymol. 155:335-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murakami, T., T. G. Holt, and C. J. Thompson. 1989. Thiostrepton-induced gene expression in Streptomyces lividans. J. Bacteriol. 171:1459-1466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhodius, V. A., and S. J. Busby. 1998. Positive activation of gene expression. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 1:152-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riethdorf, S., U. Volker, U. Gerth, A. Winkler, S. Engelmann, and M. Hecker. 1994. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression of the Bacillus subtilis lon gene. J. Bacteriol. 176:6518-6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Saiki, R. K., D. H. Gelfand, S. Stoffel, S. J. Scharf, R. Higuchi, G. T. Horn, K. B. Mullis, and H. A. Erlich. 1988. Primer-directed enzymatic amplification of DNA with a thermostable DNA polymerase. Science 239:487-491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sanger, F., S. Nicklen, and A. R. Coulson. 1977. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 74:5463-5467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schelin, J., F. Lindmark, and A. K. Clarke. 2002. The clpP multigene family for the ATP-dependent Clp protease in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus. Microbiology 148:2255-2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobczyk, A., A. Bellier, J. Viala, and P. Mazodier. 2002. The lon gene, encoding an ATP-dependent protease, is a novel member of the HAIR/HspR stress-response regulon in actinomycetes. Microbiology 148:1931-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tojo, N., S. Inouye, and T. Komano. 1993. The lonD gene is homologous to the lon gene encoding an ATP-dependent protease and is essential for the development of Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 175:4545-4549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Viala, J., and P. Mazodier. 2002. ClpP-dependent degradation of PopR allows tightly regulated expression of the clpP3 clpP4 operon in Streptomyces lividans. Mol. Microbiol. 44:633-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Viala, J., G. Rapoport, and P. Mazodier. 2000. The clpP multigenic family in Streptomyces lividans: conditional expression of the clpP3 clpP4 operon is controlled by PopR, a novel transcriptional activator. Mol. Microbiol. 38:602-612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanisch-Perron, C., J. Vieira, and J. Messing. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene 33:103-119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]