Abstract

Defining the global migration of clinical research is central to allocating resources in coordinated efforts to address global health needs. We used 15 World Health Organization-approved clinical trial registries to measure patterns of clinical research by geographic region and development over a 14-year period. With data from 205,455 trials, we show that clinical research is shifting from high-income countries to low- and middle-income Asian countries, which has clinical, public health, regulatory, ethical, and economic implications.

Keywords: Clinical trials, trial registry, World Health Organization, International Clinical Trial Registry Platform, globalization, developing countries

Human clinical trials have evolved from an observational study of meat consumption in the Old Testament1 to over 3,000 Clinical Research Organizations (CROs), private for-profit agencies, with global market revenues exceeding $21 billion2–4. Moving human clinical trials, estimated to be 40% of drug development costs5, to a resource-limited setting may reduce trial expenditures by 60%6. Clinical researchers, including CROs, have increasingly used global networks to reduce costs and accelerate recruitment2,3,7,8. Because the migration of clinical trials has numerous public health, economic, social, and ethical implications, we explored a large repository of open-access trial registry data to understand the global distribution of clinical trials.

We examined data of 205,455 clinical trials from 15 global primary trial registries and conducted in 163 countries from 1999 through 2012 (Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). The first 6 years (1999–2004) represented just 8% of all registered trials, and numbers increased sharply in 2005 after registration requirements by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME). The 30,964 clinical trials registered globally during 2012 represented a 66% increase from trials registered during 2005.

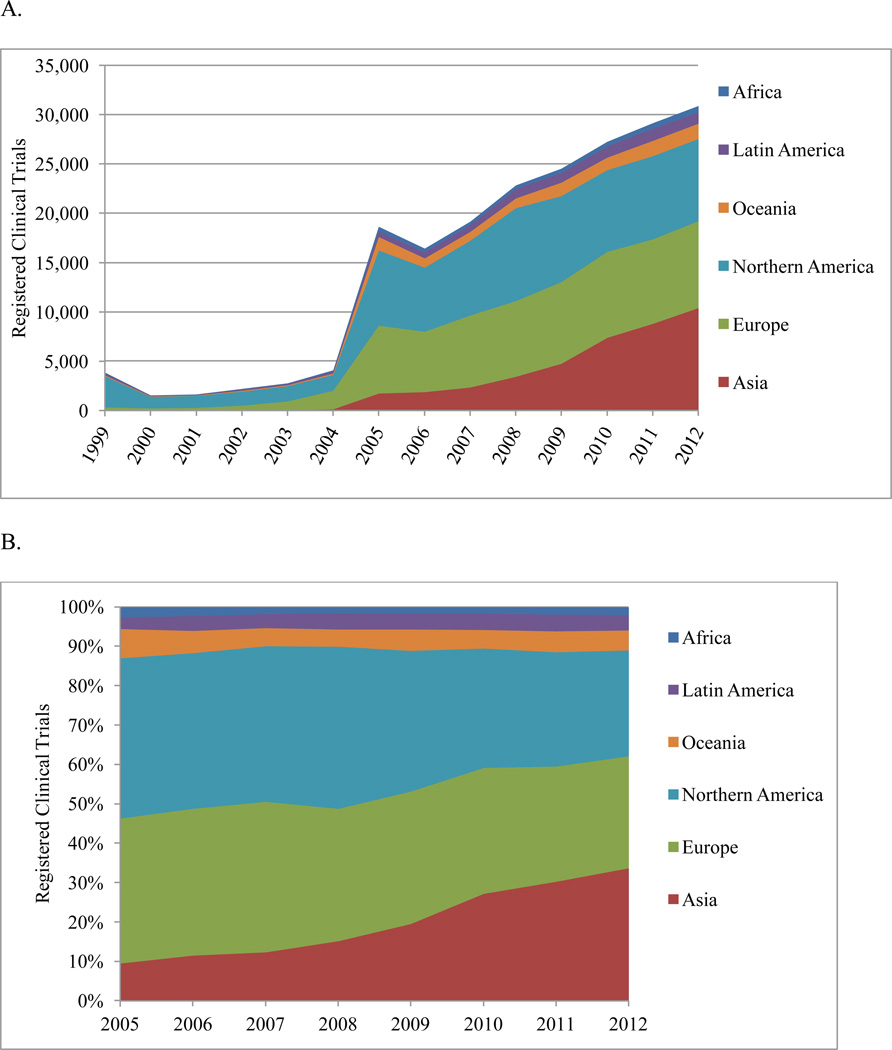

Clinical trials were oriented by geographical region (Figure 1A). From 2005 onward, 67% of registered trials were conducted in 2 North American and 41 European countries. The United States was the single largest country conducting clinical trials (Supplementary Table 3). The absolute increase was greatest for Asian (489% increase) and Latin America/Caribbean (112%) regions; the smallest increase occurred in the North American region (9%) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Total annual number (A) and percentage distribution (B) of registered clinical trials by United Nations geographic region, 1999–2012.

Total number of trials = 205,455, including Africa: 3,983; Latin America: 8,117; Oceania: 10,418; Northern America: 75,128; Europe: 66,396; Asia: 41,413.

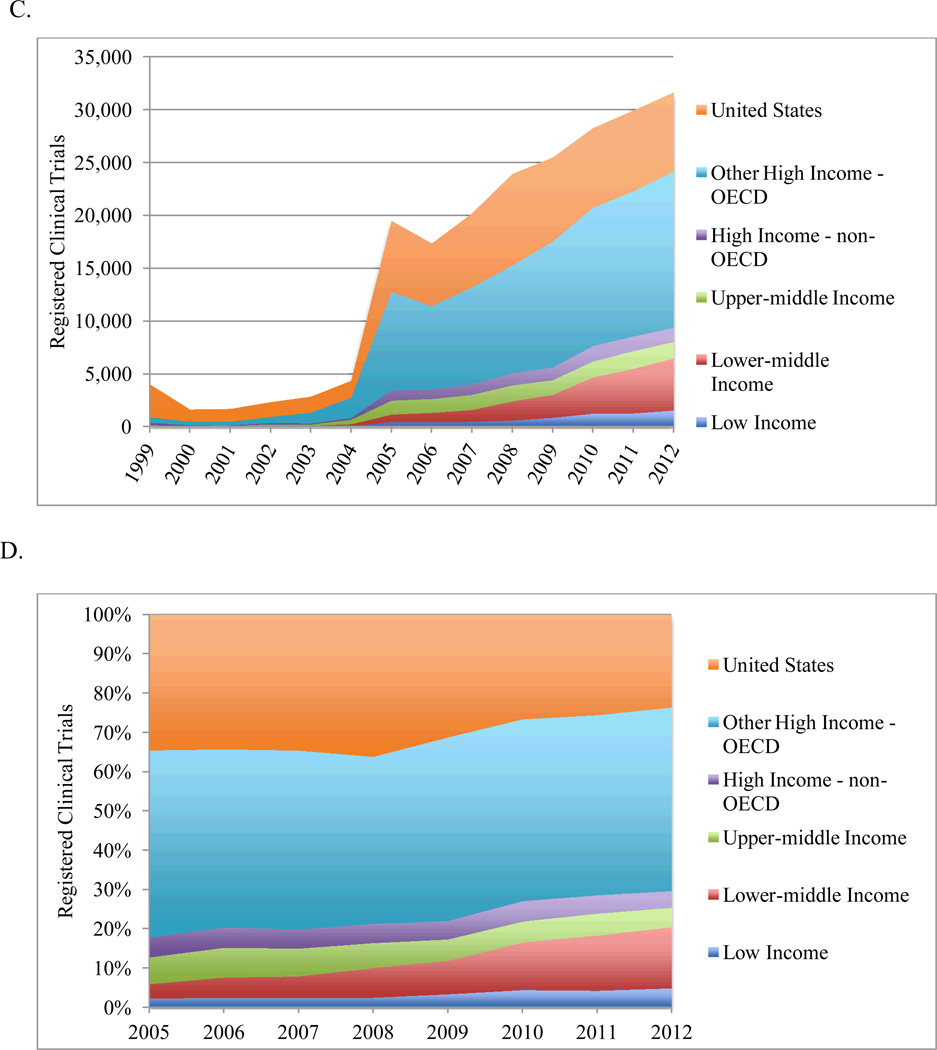

Total annual number (C) and percentage distribution (D) of registered clinical trials by World Bank economic development category. Data for US and other high-income OECD countries are displayed separately.

Total number of trials = 213,331, including United States: 69,007; Other high-income OECD: 94,844; High-income non-OECD: 10,201; Upper-middle income: 12,621; Lower-middle income: 19,648; Low income: 7,010.

By economic development, 76% of trials were conducted among 24 high-income OECD countries (Figure 1C). From 2005, absolute growth was highest among lower-middle income (594% increase) and low-income (247%) countries (Figure 1D). Meanwhile, high-income non-OECD and high-income OECD countries excluding the United States had increases of 36% and 59%, respectively. The United States had an 11% increase in absolute number of trials, but their global proportion of trials decreased from 35% to 24%. The global proportion of registered trials increased in low-income (2% to 5%) and lower-middle income (4% to 16%) countries (p<0.0001).

The highest average clinical trial densities since 2005 occurred in Oceania, North American, and European regions, as well as high-income OECD and non-OECD countries. The 48 low-income countries averaged 0.3 trials/106 people–one clinical trial for every 3 million people. Denmark had the highest average trial density (106.9 trials/106 people), and other high-density countries included Estonia, Netherlands, Israel, and Finland (Supplementary Table 4).

The largest average annual growth from 2005–2012 occurred in Asian (30%), and Latin American/Caribbean (12%) regions; other geographic regions had growth rates less than the world average (8%). The largest average annual growth occurred in lower-middle income (33%) and low-income (21%) regions. Emerging economies from low-middle income countries (Iran, China, Egypt) had the largest country-specific growth; other countries included South Korea, Japan, India, Brazil, and Turkey (Supplementary Table 5). The United States had an average annual growth rate of 2%.

When examining the 14-year pattern, a higher gross national income (GNI) and major geographic region were strongly correlated with a higher clinical trial density (p<0.0001) (Supplementary Figure). In a multivariate model, GNI remained strongly correlated with clinical trial density (p<0.0001), but not major geographic region (p=0.11).

We show that clinical trials have increased in all geographic regions and development categories, but growth has been greatest in Asia and Latin America/Caribbean regions, and among low and lower-middle income countries with emerging economies. The global migration of clinical research from high-income countries to mostly low- and middle-income Asian countries has numerous implications. Since 70% of total global biomedical research funding is supplied by either the U.S. government or U.S.-headquartered corporations9, these data suggest an outsourcing of clinical research to countries with emerging economies. Since 2006, 13 of the top 20 global pharmaceutical companies have established research and development centers in China, which may reduce research costs and entice consumers in growing markets2,8.

Global health leaders created a roadmap to transform biomedical education to strengthen health systems, but there was little mention of improving clinical research capacity10. Clinical trials are needed in low- and middle-income countries to address prevalent conditions11,12 and improve clinical research training. As research funding expands13,14 and more trials are conducted in resource-limited settings, good clinical practices and ethical assurances must be secure. Human participation in clinical research is essential to advancing medicine and public health, and expanding clinical trials require oversight to ensure research quality and participant protection.

Supplement

Data Collection and Analyses

We obtained individual and country-level clinical trial registry data from the WHO’s open-access International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) database15. As of September 2013, ICTRP contained 15 primary clinical trial registries that met ICMJE requirements and WHO Registry Network reporting criteria for content, quality and validity, accessibility, unambiguous identification, technical capacity, and administration and governance (Supplementary Table 1)15. All primary registries were required to (1) have a national or regional remit or the support of government, (2) be managed by a not-for-profit agency, and (3) be open to all prospective registrants. We excluded clinical trial registries still working towards becoming ICTRP primary registries. Data in ICTRP primary registries are updated at least monthly. We extracted data on the number of phase 0–4 clinical trials registered as being conducted within each United Nations-member country listed on the ICTRP website during the calendar years of 1999 through 2012. At the time of data extraction (July 2013), all registries had complete data through the end of 2012. Most trials were unregistered until 200516,17, when the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICJME) mandated trial registration in order to publish in leading peer-reviewed journals17,18. Today, the WHO maintains the ICTRP as the sole global repository of open-access human clinical trial information, where the vast majority of published clinical trials are now registered19.

We ascertained each country’s geographic region from the United Nations Statistics Division. We recorded each country’s economic development category as “High-Income and a Member of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)”, “High-Income and Non-Member of the OECD (non-OECD)”, “Upper-Middle Income (UMC)”, “Lower-Middle Income (LMC)”, or “Low-Income (LIC)” from the World Bank in 2006, the mid-point of our study period (Supplementary Table 6)20. We used country-specific population data for the most recent year from the United Nations Populations Division, and country-level Gross National Income (GNI) at purchasing power parity for the most recent year from the World Bank20. We excluded small overseas regions of France (Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Reunion). Laos and the Solomon Islands were excluded, since data were unavailable.

We summarized country-level trial registry data by geographic region and economic development status. We generated proportional ratios of trials conducted in individual countries, stratified by economic development and geographic region. We calculated annual trial density as the number of registered trials each year per million people, and calculated average relative annual growth rate of trial members for individual countries having a minimum of 100 registered trials in 2012. We ranked the top 20 countries for total number of registered clinical trials, average trial density (2005–2012), and average annual growth rate (2005–2012). Analyses of trends focused on the 2005–2012 period, since there was considerable underreporting before 2005. We analyzed differences in percentage of all clinical trials by development category and geographic region using Fisher’s Exact test. We conducted univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses to assess the relationship between trial density, GNI, and major geographic region, using a robust variance to account for unmeasured ecologic and population differences.

Our findings are consistent with, but expand upon, several small, geographically limited studies that have suggested human clinical trials have shifted within global markets3,21,22. Thiers et al. used data from ClinicalTrials.gov to show most U.S.-registered clinical trials from 2004–2007 were conducted in North America, Western Europe, and Oceania, while growth was occurring in regions with emerging economies3. We expand on previous analyses by including data from 15 global trial registries, having a 3-fold longer follow-up period after mandatory registration was enacted (2005), and by evaluating the impact of economic development.

This study is limited by reliance on voluntary, self-reported data, which is subject to reporting biases. Some clinical trials remain unregistered23, and reporting of clinical trials has improved dramatically since 200724. Variability of clinical trial registration might have selective reporting bias in certain countries, which could impact our distribution and migration results. In addition, changing definitions and requirements of clinical trial registration occurred during this period. The ICMJE began to implement the WHO definition of clinical trials, which states “any research study that prospectively assigns human participants or groups of humans to one or more health-related interventions to evaluate the effects on health outcomes”, for all trials that began enrolment on or after July 1, 200817. Some clinical trials may have appeared in more than one primary trial registry. We minimized duplication of multi-country trials in aggregate analyses by obtaining individual clinical trial data within each strata of geographic region or development status. The primary strengths of this study were using global, open-access data from 15 primary registries approved by both the ICJME and WHO, and the tracking of registration trends over a 14-year period.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Harvard Global Health Institute, the Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholars and Fellows Program at Vanderbilt University (R24 TW007988), The Program in AIDS Clinical Research Training Grant (T32 AI007433) (PKD); the National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH090326 (IVB); and the Claflin Distinguished Scholar Award (IVB).

Footnotes

Author Contributions

P.K.D., M.R., and I.V.B. designed the study. P.K.D. and M.R. collected and analyzed the data. P.K.D. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to data interpretation and manuscript revision.

The authors declare no competing financial interests. Readers are welcome to comment on the online version of the paper.

References

- 1.Old Testament, Book of Daniel; chapter 1, verses 12 – 15; describes a planned experiment with both baseline and follow-up observations of two groups who either ate, or did not eat, “the King's meat” over a trial period of ten days.

- 2.Rowland C. Clinical trials seen shifting overseas. Int J Health Serv. 2004;34:555–556. doi: 10.2190/N8AU-6AG6-30M9-FN6T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thiers FA, Sinskey AJ, Berndt ER. Trends in the globalization of clinical trials. Nature Rev Drug Discovery. 2008;7:13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brooks K Contract Pharma. [Accessed on July 29, 2013];CRO Outlook & Opportunities: e-clinical solutions fuel advances. Available at http://www.contractpharma.com/issues/2012-06/view_features/cro-outlook-opportunities/. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banerjee A. In full run: Clinical trials to hit Rs 1,100cr in 3 years. New Delhi: The Economic Times; 2005. Nov 17, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinha G. Outsourcing drug work. Pharmaceuticals ship R&D and clinical trials to India. Sci Am. 2004;291:24–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munos B. Lessons from 60 years of pharmaceutical innovation. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2009;8:959–968. doi: 10.1038/nrd2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glickman SW, McHutchison JG, Peterson ED, et al. Ethical and scientific implications of the globalization of clinical research. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:816–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb0803929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schweitzer SO. Pharmaceutical economics and policy. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frenk J, Chen L, Bhutta ZA, et al. Health professionals for a new century: transforming education to strengthen health systems in an interdependent world. Lancet. 2010;376:1923–1958. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kapiriri L, Lavery JV, Singer PA, Mshinda H, Babiuk L, Daar AS. The case for conducting first-in-human (phase 0 and phase 1) clinical trials in low and middle income countries. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:811. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas C. Roadblocks in HIV research: five questions. Nat Med. 2009;15:855–859. doi: 10.1038/nm0809-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Getz KA. Sizing up the clinical research market. Applied Clin Trials. 2010 Mar 1; Accessed at: http://www.appliedclinicaltrialsonline.com/ on June 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorsey ER, de Roulet J, Thompson JP, et al. Funding of US biomedical research: 2003–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:137–143. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. International Clinical Trials Registry Platform. Accessed at: http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx on July 18 2013.

- 16.Zarin DA, Tse T, Ide NC. Trial Registration at ClinicalTrials.gov between May and October 2005. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2779–2787. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laine C, Horton R, DeAngelis CD, et al. Clinical trial registration: looking back and moving ahead. Lancet. 2007;369:1909–1911. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60894-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Angelis C, Drazen JM, Frizelle FA, et al. Clinical trial registration: a statement from the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1250–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe048225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ross JS, Tse T, Zarin DA, Xu H, Zhou L, Krumholz HM. Publication of NIH funded trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov: cross sectional analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:d7292. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d7292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank. World Development Report, 2006. Washington DC: World Bank; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prabhakaran P, Ajay VS, Prabhakaran D, et al. Global cardiovascular disease research survey. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:2322–2328. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Devasenapathy N, Singh K, Prabhakaran D. Conduct of clinical trials in developing countries: a perspective. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2009;24:295–300. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32832af21b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heger M. Clinical trial website struggles to serve as research data hub. Nat Med. 2012;18:837. doi: 10.1038/nm0612-837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Califf RM, Zarin DA, Kramer JM, Sherman RE, Aberle LH, Tasneem A. Characteristics of clinical trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov, 2007–2010. JAMA. 2012;307:1838–1847. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.