Abstract

CS1 is one of a limited number of serologically distinct pili found in enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains associated with disease in people. The genes for the CS1 pilus are on a large plasmid, pCoo. We show that pCoo is not self-transmissible, although our sequence determination for part of pCoo shows regions almost identical to those in the conjugative drug resistance plasmid R64. When we introduced R64 into a strain containing pCoo, we found that pCoo was transferred to a recipient strain in mating. Most of the transconjugant pCoo plasmids result from recombination with R64, leading to acquisition of functional copies of all of the R64 transfer genes. Temporary coresidence of the drug resistance plasmid R64 with pCoo leads to a permanent change in pCoo so that it is now self-transmissible. We conclude that when R64-like plasmids are transmitted to an ETEC strain containing pCoo, their recombination may allow for spread of the pCoo plasmid to other enteric bacteria.

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC) strains are a major cause of diarrheal disease in humans (2, 3, 30). Infection occurs by ingestion of food or water contaminated with ETEC bacteria. Since human or animal waste is the ultimate source of ETEC contamination, ETEC infections are associated with poor hygiene and sanitation and are therefore a serious problem in developing countries. In adults, ETEC diarrhea is usually self-limiting, but in infants and small children it can cause significant mortality. After the ETEC bacteria are ingested, colonization of the small intestine is necessary for disease. Once the bacteria have colonized the small intestine, they produce the heat-labile and/or the heat-stable enterotoxin, which leads to copious fluid secretion from the intestine.

Colonization of the host is an important first step in pathogenesis and requires attachment of the bacteria to specific receptors on host cells. In gram-negative bacteria, pili often mediate these specific interactions. At least 21 serologically distinct pili have been identified among different ETEC strains associated with human disease (12, 37). The sequences of the structural and assembly proteins of several of these pili are closely related. This family of related pili includes CS1, CS2, CS4, CS14, CS17, CS19, and colonization factor antigen I (12). Production of functional CS1 pili in E. coli K-12 requires the products of only four genes, cooB, -A, -C, and -D (10, 36, 44). This is in sharp contrast to other types of pili such as Pap, type 1, and type IV, associated with other human pathogens, in which 9 genes, 7 genes, or at least 12 genes, respectively, are required (17, 18, 41).

Like the genes encoding many other virulence traits in pathogenic bacteria, the coo genes for CS1 pili are flanked by DNA that is homologous to pieces of insertion sequence (IS) elements (10, 43). In addition, the coo genes have a G+C content that differs from that of most of the genes in the organism in which they reside. This suggests that they were introduced recently into E. coli by insertion of a small DNA segment (pathogenicity islet). In addition, instead of being chromosomally located, the coo genes are on a large plasmid, pCoo (36). This provides additional potential for their current or past horizontal transfer.

In addition to the four coo genes, a gene encoding a positive regulator, rns, is necessary for production of CS1 pili (5). Rns, which is a member of the AraC family of regulatory elements, activates transcription of the coo genes as well as its own transcription (5, 9). Rns is encoded on a plasmid distinct from pCoo, which is mobilizable by coresident IncFII conjugative plasmids (4, 5). In some CS1-producing strains, this plasmid also encodes the colonization factor CS3 and one or both toxins (33).

To determine whether other virulence genes are also localized to pCoo, we sequenced 36 kb of the DNA surrounding the coo genes. In this region, we identified extensive homology to some genes of the drug resistance IncI1 plasmid R64 that are required for conjugative transfer. R64, which is found in enteric bacteria, has at least 23 genes that are essential for conjugation in liquids and on surfaces (27). In addition, there are 12 more genes that are necessary for production of the R64 type IV thin pilus, which is required for matings in liquid (22, 51). These type IV pili consist of the major pilin subunit, PilS, and a minor pilin, PilV (50). PilV is the adhesin that is thought to be located at the tip of the thin pilus (50). The PilV protein consists of a 361-amino-acid N-terminal constant region and a C-terminal variable region, which ranges from 69 to 113 amino acids in length. The seven potential C termini for pilV are part of a multiple DNA inversion system, the shufflon (25, 26). The R64 shufflon consists of four DNA segments which encode seven different PilV C termini, one of which is part of the PilV being produced. These DNA segments, each of which encodes one or two C termini, are flanked and separated by 19-bp repeats. The Rci recombinase, encoded directly downstream of the shufflon, mediates site-specific recombination at any two of these 19-bp repeats that are in opposite orientations (25). When the recombination includes the 19-bp repeat within the expressed pilV gene, a different C terminus is fused in frame to the constant region of pilV. The specificity of recipient strains, to which R64 can be transferred in liquid mating, is determined by the PilV variant produced (23, 24). The variants have differing receptor specificities, and each variant can mediate conjugation to only a subset of the possible recipients (19, 20). The known recipients for R64 conjugation are enteric bacteria, including E. coli, Salmonella, and Shigella.

Although pCoo contains homology to the region encoding the R64 thin pilus, we found that the plasmid is not self-transmissible. However, when pCoo and R64 reside in the same cell, pCoo markers are transferred in mating. Transconjugants often acquire a pCoo plasmid that becomes self-transmissible after recombination with R64. We believe that the possibility for recombination of pCoo with a coresident IncI1 plasmid has important implications for the evolution and distribution of the pCoo plasmid and for the spread of virulence traits among enteric bacteria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains used are listed in Table 1. Bacteria were grown in Luria-Bertani medium at 37°C with aeration. The plasmids pHSG576 (Cmr) (47), pTH18cr (Cmr) (16), and pUC18 (Apr) (32) were used to provide markers for selection in matings. R64colK is a conjugative IncI1 Tcr plasmid (49) and will be referred to as R64 in the rest of this paper. Antibiotics used were ampicillin (100 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (40 μg/ml), kanamycin (50 μg/ml), nalidixic acid (100 μg/ml), and tetracycline, 10 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain | Relevant traitsa | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| 60R75 | ETEC CS1+ | Bernard Rowe via Eileen Barry |

| C921b-1 | ETEC O6:K15:H16, biotype A, CS1+ CS3+ | 45 |

| C600 | K-12 | 1 |

| C600str | K-12 C600 Strr | Spontaneous mutant of C600 |

| JEF100 | Derivative of C921b-1, CooB::ΩKm | 4 |

| N99 | K-12 Strr | 14 |

| SJ1 | K-12 C600 Strr Nalr | Spontaneous mutant of C600str |

| EU2573 | JEF100/pHSG576 (Kmr Cmr) | This study |

| EU2574 | JEF100/pHSG576/R64 (Kmr Cmr Tcr) | This study |

Strr, streptomycin resistant; Nalr, naladixic acid resistant; Kmr, kanamycin resistant; Cmr, chloramphenical resistant; Tcr, tetracycline resistant.

DNA sequencing of pCoo.

The cosmid clone pEU405 (36) derived from pCoo was digested with HindIII and self-ligated to produce pEU4005.1, which was used for sequencing. Ambiguous regions were resequenced both on the cosmid clone and on the pCoo plasmid isolated from the ETEC-derived strain LMC10 (5).

Introduction of the kanamycin resistance marker into pCoo in ETEC strains.

A 4.1-kb PstI/XbaI DNA fragment containing the omega kanamycin element (35) inserted into the XmnI site of cooB was isolated from pEU806 (44). The kanamycin resistance cassette is flanked by about 900 bp of coo DNA in this fragment. The linear DNA fragment was purified by agarose gel electrophoresis, extracted by using a Qiagen Minelute gel extraction kit, and introduced into the ETEC strains by electroporation. Recombinants were selected for kanamycin resistance, and the presence of the omega element in cooB was confirmed by PCR using primers within the cooB gene that flanked the site at which the omega kanamycin element was inserted.

Conjugative transfer.

The recipient was grown in selective medium and then pelleted and resuspended to its original volume in nonselective medium. Donor cells were grown to log phase in nonselective medium and then mixed with one-fourth volume of the recipient. For matings in liquid, the mixture was incubated without shaking for 90 min at 37°C and plated onto selective media. For matings on solid surfaces, the mating mixture was collected onto a nitrocellulose filter that was placed on a plate containing nonselective medium and incubated for 90 min at 37°C. After resuspension of the cells from the membrane, the mating mixture was plated onto selective media. The transfer frequency was expressed as the number of transconjugants with the selected marker per donor cell present after mating.

Plasmid stability.

The strains containing the plasmids to be tested for stability were grown overnight at 37°C with aeration in medium selective for all plasmids present. To measure the retention of plasmids at the start of the experiment, the overnight culture was plated on both selective and nonselective media. The culture was then diluted to a concentration of about 1,000 cells/ml in nonselective medium and grown at 37°C with aeration until the cells reached a concentration of 2 × 108 to 6 × 108/ml. The fraction of bacteria containing the plasmids was determined by plating on both selective and nonselective media. In cases where most of the bacteria contained the plasmids, replica plating was used to assess plasmid loss.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence of 36 kb of the pCoo plasmid has been deposited in GenBank under accession no. AY536429.

RESULTS

Regions of pCoo homologous to IS elements.

The structural genes required for production of the CS1 pilus, cooB, -A, -C, and -D, are located on a large plasmid, pCoo (either 66 or 47 kb) (4). The coo genes are surrounded (Fig. 1, regions B and C) by DNA with homologies to IS elements (10, 43). Both upstream (211 to 357 bases from the start of CooB [Fig. 1, region B]) and downstream (213 to 426 bases from the end of CooD [Fig. 1, region C]) of the coo genes are small regions of homology to IS629 (31). Upstream of the coo genes a region of homology to IS629 includes the 5′ end of the IS element, and downstream of the coo genes is a region with homology to the 3′ end of IS629. Following this is a region that is 99% identical to 877 bases of one end of IS2 (13). The homology to IS2 continues to the end of the pCoo DNA for which sequence is available, so there may be an intact IS2 element in pCoo. Upstream of the start of the cooB open reading frame (ORF) (bases 519 to 1229 [Fig. 1, region B]) there is an ORF with 42% amino acid similarity to the transposase of IS150, an IS3-like element (42).

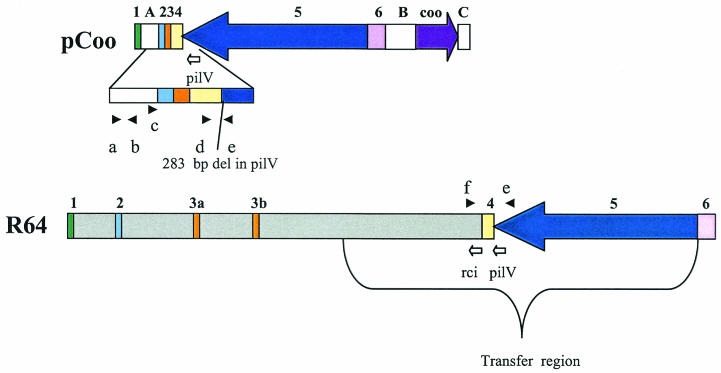

FIG. 1.

Comparison of the sequenced region of pCoo with a portion of R64. Only 84,220 bases of R64 are shown. The gray regions are unique to R64, and the white regions labeled A (bases 1092 to 4526, most homologous to plasmid stability genes), B (bases 22744 to 28178, homologous to IS elements), and C (bases 34750 to 35628, homologous to IS elements) are unique to pCoo. The purple arrow delineates the extent and direction of transcription of cooB, -A, -C, and -D (bases 29008 to 34078). The regions of homology between pCoo and R64 are, respectively, labeled 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 above the maps and are colored green (bases 44041 to 45131 in R64 and bases 1 to 1091 in pCoo), light blue (bases 50060 to 50806 in R64 and bases 4527 to 5273), orange (bases 54151 to 54459 and 61100 to 61412 in R64 and bases 5276 to 5587 in pCoo), yellow (bases 103208 to 105144 in R64 [encodes the shufflon] and bases 5586 to 7347 in pCoo), dark blue (bases 105145 to 120826 in R64 and bases 7348 to 22747 in pCoo), and pink (bases 1 to 2250 in R64 [encodes the origin of replication] and bases 22748 to 24997 in pCoo). The dark blue arrow (region 5) delineates the extent and direction of transcription of all of the genes required for thin pilus production. A bracket under the R64 map delineates the extent of the R64 transfer region, which contains all of the genes needed for conjugation. The black arrowheads above the map for R64 and below the map for the expanded region of pCoo show the locations of primers used. The white arrows under the maps labeled rci and pilV show the directions of transcription and extents of these genes. The R64 coordinates are from GenBank accession no. AP005147.

To learn more about the plasmid encoding the CS1 pili, we have determined further sequence upstream of the previously sequenced regions (the DNA between 1,001 bases upstream and 1,549 bases downstream of the coo region was previously sequenced [10, 36, 44]). This revealed an additional IS element directly upstream of the others and unrelated to them. Between bases 27663 and 26664 of pCoo (1,345 to 2,346 bases upstream of the start of cooB) there is an ORF whose translated product has 92% amino acid similarity to the transposase of IS1328 (40). Although the similarity at the DNA level between this ORF and that of IS1328 is low, the transposon DNA flanking the ORF is 83% identical to the pCoo DNA at the same positions relative to the transposase. The IS1328 element in pCoo is complete except that it lacks one of the inverted repeats, making it unlikely to be able to transpose.

pCoo has homology with the R64 origin of replication and is incompatible with R64.

The 36-kb region of pCoo whose sequence we have just determined has several regions of homology to the conjugative IncI1 drug resistance plasmid R64. One of these pCoo regions (Fig. 1, region 6) shows 95% homology to the part of R64 that includes its vegetative origin of replication (15). This suggested the possibility that pCoo and R64 might be in the same incompatibility group.

To test this, strains C600/R64, EU2573/pCooKm, and EU2574/pCooKm/R64 were grown overnight with selection for all plasmids and diluted 106-fold into medium without antibiotics. The presence of each plasmid was assessed by plating on medium containing tetracycline for R64, kanamycin for pCooKm, and both antibiotics for both plasmids together (Table 1). After 17 generations without selection, 100% of the colonies from C600/R64 retained the R64 tetracycline marker and 100% of the colonies from EU2573/pCooKm still contained the kanamycin marker. After the same number of generations, all of the colonies from strain EU2574 still contained R64. However, pCooKm was present in only 30% of the EU2574 colonies. Thus, the presence of R64 destabilizes the inheritance of pCoo, demonstrating that pCoo is, like R64, in the IncI1 incompatibility group.

Plasmid stability regions of pCoo.

Another region (Fig. 1, region 1) of R64 homology (98% identical at the level of DNA) in the sequenced portion of pCoo is separated from the other regions of homology (Fig. 1, regions 2 to 6) by 3,425 bp (Fig. 1, region A) that is unique to pCoo. It encodes a resolvase, ResA, that is 91% identical to the Rsv protein (protein D) that is required for stable maintenance of the F plasmid (8).

The region unique to pCoo (Fig. 1, region A) that is located between R64-homologous regions 1 and 2 carries three ORFs that have homology to genes thought to be involved in stable plasmid maintenance. The first translated ORF (bases 1772 to 2401) has homology to a family of enzymes that are important for plasmid partitioning (ParA). The product of this ORF is 77% identical to Orf79 of Yersinia (accession no. AY15043) and 61% identical to a member of the ParA family from Xanthomonas citri (accession no. AAO72130) (29). The second translated ORF (bases 3017 to 3969) is 66% identical to a plasmid stability gene product, StbA, in the enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) plasmid pB171 (48). The product encoded by the final ORF in this region (bases 3995 to 4385), is 46% identical to the plasmid stability gene product StbB of pB171 (48). Although the StbA and -B proteins of pCoo are most homologous to those from the EPEC plasmid pB171, they also show similarity to genes in R64 (38% identical to the R64 StbA protein and 27% identical to R64 StbB protein). It seems likely, therefore, that stbA and -B of pCoo, as well as the rsv gene homologue, resA, help maintain stable inheritance of the plasmid.

In addition, the stability region of pCoo (Fig. 1, regions 1 and A) and that of R64 have a similar organization. In R64 there is 1,032 bp between the end of resA and the start of the stbA homologue, and in pCoo there is 1,859 bp between the two genes. For both R64 and pCoo the stbB homologue is directly downstream of stbA. The stability regions of the two differ in that the pCoo stability region contains a parA homologue, which is between resA and stbA in pCoo, and R64 does not.

Homology of pCoo with the R64 thin pilus genes.

The largest region of homology between pCoo and R64 (Fig. 1, regions 4 and 5) shows 99% identity at the DNA level. It encodes intact copies of all of the genes necessary for production of the R64 thin pilus except pilV. The R64 thin pilus genes, along with several additional genes, are indispensable for conjugation of this plasmid in liquid matings (27, 51). The pCoo homologue of the pilV gene, which encodes a minor pilin thought to be located at the tip of the thin pilus (50), has a 283-bp deletion relative to pilV of R64 (base 7386 of pCoo; bases 105468 to 105186 of R64). Thus, pCoo should produce a truncated PilV protein and it should therefore not be conjugative. This deletion is within the constant region of PilV, which extends from base 106213 to 105130 on R64.

The sequence of the C terminus of PilV in R64 can be varied by recombination of the shufflon segments (Fig. 1, region 4), which are directly downstream of pilV (25). The C-terminal sequence of PilV determines the specificity of the recipient with which R64 can conjugate in liquid (24).

In pCoo, three of the four R64 shufflon segments are intact. The pCoo homology to this region of R64 ends within the fourth shufflon segment, so the region of R64 encoding the Rci recombinase is missing. Since it was possible that the rci recombinase gene might be separated from the shufflon on the pCoo DNA, we performed a PCR using primers within the rci gene. The expected product was obtained from the R64 template, but it was absent when pCoo was used as a template (data not shown). This demonstrates that if an rci gene is present in pCoo, it is different enough from the R64 rci genes that the primers do not hybridize.

Directly downstream of the pCoo shufflon are two regions of homology to R64 that are contiguous in pCoo but not in R64 (Fig. 1, regions 2 and 3). Region 2 is 96% identical between the two plasmids at the level of DNA. In R64, there are two almost-identical copies of region 3 (3a and 3b) (Fig. 1), but only one is present in pCoo. The DNA of pCoo region 3 is 95% identical to that of 3a and 97% identical to that of 3b. These two short regions of homology (773 and 311 bp for regions 2 and 3, respectively) do not carry any genes of known function.

The pCoo plasmid is not self-transmissible.

In addition to the 12 genes required for the expression of the thin pilus, which is needed for conjugation in liquid, R64 carries 23 genes in the approximately 54-kb transfer region that are required for conjugal transfer both in liquid and on solid surfaces (27). Because the genetic makeup of pCoo suggests that it might be able to synthesize the thin pili, although the PilV tip protein would be truncated, we investigated whether pCoo is self-transmissible. To do this, we preformed matings both in liquid culture and on solid surfaces. In control experiments, R64 transferred at a high frequency under both of these conditions (Table 2, matings I and IV). To test conjugation of pCoo, we used a derivative of an ETEC strain (JEF100) in which pCoo had been marked by inserting an omega kanamycin element into cooB (44). As expected, since pilV is truncated, pCooKm is not self-transmissible in liquid (Table 2, mating II).

TABLE 2.

The pCoo plasmid is not self-transmissible but can be mobilized by R64

| Matinga | Plasmid(s) in donor | Transfer frequencyb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R64 | pCooKm | pCooKm + R64 | ||

| Liquid | ||||

| I | R64 | 6 × 10−4 | ||

| II | pCooKm | <1 × 10−8 | ||

| III | pCooKm, R64 | 1 × 10−3 | 2.8 × 10−6 | 4 × 10−7 |

| Plate | ||||

| IV | R64 | 2 × 10−2 | ||

| V | pCooKm | <1 × 10−8 | ||

In matings I and V, C600/R64 was the donor and EU2573 was the recipient. In matings II and IV, EU2573 was the donor and C600str/pUC18 was the recipient. In mating III, EU2574 was the donor and C600str/pUC18 was the recipient.

The transfer frequency is the number of transconjugants per donor cell present after mating.

Because we do not know the complete sequence of pCoo, it seemed possible that homologues to the 23 transfer genes that are not involved in production of the thin pilus might be present and therefore that pCoo might be self-transmissible when the mating is performed on a plate. However, we found that pCooKm was not self-transmissible in this experiment either (Table 2, mating V), indicating that some of the essential conjugation genes are either absent or nonfunctional. To eliminate the possibility that pCooKm was not conjugative due to the insertion of the kanamycin marker in cooB, we performed matings with a donor strain which, in addition to pCooKm, contained a compatible plasmid (pEU494) (10) that expresses all four coo genes. We found no transfer of pCooKm in this experiment either (data not shown).

pCoo can be transferred when R64 is also present in the donor.

To determine whether pCooKm could be mobilized for conjugation, we preformed matings in liquid in which the donor strain contained both pCooKm and R64. In the presence of R64, pCooKm was transferred to an E. coli K-12 recipient (Table 2, mating III). Previous studies have shown when plasmids are mobilized by R64, at least 25% of the R64 transconjugants also contain the mobilized plasmid (28, 46, 49). However, pCooKm was found in transconjugants about 103-fold less frequently than R64, and most of the transconjugants contained only pCooKm, as determined by resistance to kanamycin and sensitivity to tetracycline. Therefore, it is unlikely that R64 mobilized the pCooKm. In agreement with this, the region of pCoo that we found to be homologous to R64 does not include the R64 region containing the origin of transfer (27).

Since it is unlikely the pCooKm is being mobilized by R64, the transferred pCooKm must have recombined with the R64 in the donor. If the pCoo-R64 recombinant was the result of a single crossover, then the transconjugant would be resistant to both tetracycline and kanamycin. Although such transconjugants were found, those that contained only pCooKm as determined by resistance to kanamycin and sensitivity to tetracycline were sevenfold more frequent. These kanamycin-resistant, tetracycline-sensitive transconjugants should be the result of a double crossover between pCoo and R64. To determine whether they had all of the genes necessary for conjugation, five independent kanamycin-resistant, tetracycline-sensitive transconjugants (Table 2, mating III) were used as donors in liquid matings (Table 3). Four of the five pCooKm derivatives transferred at a high frequency, similar to the frequency of transfer of R64 (Table 2, mating I). Since they can transfer in liquid, these pCooKm plasmids must now contain a complete pilV gene as well as all other genes necessary for conjugal transfer.

TABLE 3.

pCoo transconjugant plasmids are self-transmissible

| Matinga | Plasmid in donor | Transfer frequencyb |

|---|---|---|

| I | pCooKm-21 | 2 × 10−2 |

| II | pCooKm-1 | 1.3 × 10−3 |

| III | pCooKm-11 | 7 × 10−2 |

| IV | pCooKm-14 | >3 × 10−2 |

| V | pCooKm-40 | <1.6 × 10−8 |

The donors were Kmr Tcs transconjugants from mating III (Table 2). The recipient for mating I was SJ1, and that for matings II to V was N99/pTH18cr.

The transfer frequency is the number of transconjugants per donor cell present after mating. The ratio is determined as Kmr Nalr/Kmr Apr for mating I and as Kmr Cmr/Kmr Apr for matings II to V.

Analysis of the progeny pCooKm plasmids.

To determine how the transmissible pCooKm derivatives differed from the original pCooKm, PCR analysis was performed on plasmids from 27 kanamycin-resistant, tetracycline-sensitive transconjugants from seven independent matings. All of these plasmids contained all four of the coo genes (not shown). In addition, using primers internal to rci, we demonstrated that unlike the original pCooKm, all of the transconjugant plasmids had the gene for the Rci recombinase. Using several primer pairs, we identified three classes of plasmids in the transconjugants (Fig. 1 and Table 4). Class 2 pCooKm plasmids (2 of 27 plasmids tested) are nonconjugative in liquid matings. Class 1 pCooKm plasmids (24 of 27 plasmids tested) and class 3 pCooKm plasmids (1 of 27 plasmids tested) are conjugative. Classes 1 and 3 differ in the ability of the shufflon to recombine and produce PilV variants. Using one primer in the shufflon and another in the pilV constant region (Fig. 1, primers d and e, respectively), we demonstrated that class 1 pCooKm plasmids produce PilV variants, as does R64 (Table 4, multiple bands with primers d and e; Fig. 1), and that the class 3 pCooKm plasmid does not (Table 4, a single 2.0-kb band with primers d and e; Fig. 1). Although class 3 pCooKm does not produce PilV variants, it must have functional PilV since this plasmid is conjugative. With these same primers (d and e), which span the pilV deletion in pCoo, the class 2 plasmids give the same 1.3-kb product as the wild-type pCoo plasmid, suggesting that the deletion is still present in pilV. Thus, it is not surprising that class 2 pCooKm plasmids are not conjugative in liquid matings. Transfer of class 2 plasmids might have resulted from complementation for PilV production.

TABLE 4.

PCR analyses of the pCoo plasmids from transconjugants

| pCoo class | Conjugative | PCR result witha:

|

coo genes | rci | No. of clones | No. of exptb | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/a and b | A and 5/c and e | rci and 5/f and e | 4 and 5/d and e | ||||||

| 1 | + | − | − | + | Multc | + | + | 24 | 7 |

| 2 | − | − | − | + | 1.3 kb | + | + | 2 | 2 |

| 3 | + | + | + | − | 2.0 kb | + | + | 1 | 1 |

| Wild type | − | + | + | − | 1.3 kb | + | − | ||

| R64 | + | − | − | + | Mult | − | + | ||

Regions of pCoo and R64 amplified/primers used for amplification (Fig. 1).

Number of independent matings.

Mult, multiple bands were found.

In the class 1 (conjugative) and 2 (nonconjugative) pCooKm plasmids, the complete R64 transfer region is apparently contiguous (as it is in R64 and not in the parental pCoo [Fig. 1]). This was demonstrated by using primer pairs in pilV and pCoo region A (Fig. 1, primers c and e) and in pilV and rci (Fig. 1, primers e and f) to distinguish the pCooKm from the R64 gene orders in the region downstream from pilV. Unlike wild-type pCooKm, these class 1 and 2 plasmids produced no PCR product with primers c and e, but they produced the same-size product as R64 when primers f and e were used. These PCR results are consistent with class 1 and 2 pCooKm plasmids resulting from a double crossover between pCooKm and R64. Since both classes lack pCoo region A (Table 4 and Fig. 1, primers a and b), one crossover probably occurred at homology region 1 (Fig. 1) or at some homology in the unsequenced region to the left of region 1. The second crossover that generated class 1 plasmids probably occurred to the right of the pilV deletion in homology region 5 or 6 (Fig. 1). Recombination between pCoo and R64 in these regions would result in a pCoo derivative containing the complete R64 transfer region with a wild-type pilV. The second crossover that generated the class 2 pCooKm plasmids must have occurred to the left of the deletion in pilV in region 4 or 5 (Fig. 1). This double crossover would result in a pCooKm containing the complete R64 transfer region with a deleted pilV.

The single class 3 pCooKm plasmid must have been the result of some more complex exchange of DNA between R64 and pCoo. Use of primer pairs a-b and c-e (Fig. 1) demonstrated that the class 3 pCooKm contains pCoo region A at the same position as does the parental pCoo (Fig. 1). Unlike R64 and the class 1 and 2 plasmids, the rest of the transfer genes are not directly adjacent to pilV in the class 3 plasmid. However, since this plasmid is conjugative, these transfer genes must be present at some other location in this plasmid.

The pCoo plasmid from ETEC strain 60R75 is not self-transmissible, but it can be transferred when R64 is present in the donor.

The pCoo plasmid from C921b-1 is nonconjugative but is able to transfer when R64 is coresident. To determine whether this is also the case for another pCoo plasmid, we inserted a marker into the cooB gene of the pCoo plasmid from an independent clinical ETEC isolate, 60R75. The results obtained with this strain were similar to those with the C921b-1 derivative JEF100 (Tables 2 and 3). The pCooKm from 60R75 alone was not self-transmissible (transfer frequency of <10−8). However, when R64 was coresident with the pCooKm, the latter was transferred alone at a frequency of 4.7 × 10−7. The progeny pCooKm plasmids isolated from transconjugants in two independent matings were found to be conjugative (not shown). Thus, in both CS1-expressing ETEC strains tested, C921b-1 and 60R75, temporary coresidence of pCoo and R64 leads to a permanent change in the pCoo plasmid so that it can be transferred to other bacteria.

DISCUSSION

pCoo is an IncI1 plasmid related to R64.

The CS1 pilus is required for colonization of the human small intestine, which is an early step in diarrheal disease caused by ETEC strains. In the ETEC strains examined, the genes encoding this pilus are on a large plasmid. We have determined that a pCoo plasmid isolated from an ETEC strain associated with human disease is closely related to the drug resistance plasmid R64. The regions of homology between pCoo and R64 include the R64 vegetative origin of replication. As suggested by this relationship, we found that these plasmids are not stably coinherited. Therefore, pCoo, like R64, is a member of the IncI1 incompatibility group. We found that R64 and pCoo recombine at a high frequency to generate plasmids that encode production of CS1 pili and also possess genes originally present on R64.

Recombinant pCoo should be able to transfer to many different recipients.

The close relationship of pCoo to the self-transmissible plasmid R64 suggested the possibility that pCoo plasmids from ETEC strains might be conjugative. In this work, we found that neither of the pCoo plasmids from either independent clinical isolate studied (C921b-1 and 60R75) is conjugative. However, temporary coresidence of either of these pCoo plasmids with R64 resulted in homologous recombination leading to the formation of at least two kinds of self-transmissible pCoo derivatives. These pCoo derivatives are conjugative in liquid matings and therefore contain a complete pilV gene, which encodes a minor subunit of the thin pilus.

The C-terminal sequence of PilV limits the strains that can serve as recipients in conjugation, presumably because this protein contacts the recipient cell to facilitate plasmid DNA transfer in mating in liquid. For example, R64 with shufflon C in the pilV coding frame will be able to mate with E. coli K-12 but not with Shigella flexneri. When the shufflon changes to D′, R64 may now mate with S. flexneri but not with E. coli K-12. Shufflon recombination is frequent enough that all seven possible PilV variants should be present in the population in a single culture (23, 24). Thus, R64 can be transferred from a single donor strain to many different enteric bacteria, including strains of E. coli, Salmonella, and Shigella (23, 24). Among the recombinant pCoo transconjugant plasmids that have become self-transmissible, we found that most can vary the C terminus encoded by the pilV gene. Therefore, these conjugative pCoo derivatives can now be transferred to a variety of different strains and species of enteric bacteria.

Since both pCoo and R64 are found in enteric bacteria, it is possible that R64 could be transferred to a pCoo-containing ETEC strain. R64 was originally isolated from a strain of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, and plasmid ColIb-P9, which is very closely related to R64, was isolated from a strain of Shigella sonnei (11, 21). Once R64 or ColIb-P9 enters a bacterium containing pCoo, recombination should occur and enable the pCoo plasmid to transfer to any bacteria in the gut that have receptors for the thin pili.

Will the coo genes be expressed when pCoo enters a new host?

The presence of a recombinant pCoo plasmid would lead to production of the thin pili, but the CS1 pili would be expressed only if the appropriate activator, rns, was also carried in the cell. Rns is a member of the AraC family of transcription regulators (5). There is a group of homologous genes that are very closely related to rns that are also present in many enteric bacteria (6, 7, 12, 34, 38). Most similar (about 95% at the DNA level) are rns homologues found in many ETEC strains that do not produce CS1 pili. If one of these strains acquires a pCoo plasmid, it is extremely likely that CS1 pili would be produced. Very similar rns homologues are also present in non-ETEC E. coli strains associated with diarrhea, including some strains classified as enterohemorrhagic E. coli, EPEC, and enteroinvasive E. coli. If a pCoo plasmid entered one of these strains, CS1 pili should be produced as well.

Other members of the rns family are present in non-E. coli enteric pathogens, including Shigella, Yersinia, and Vibrio cholerae. These genes are often so closely related to rns that they are functionally interchangeable (7, 34, 38). Thus, if a recombinant pCoo plasmid entered a bacterium with one of these rns-related genes, these should also produce CS1 pili.

In addition, Rns is encoded on a plasmid that is compatible with pCoo. Although the plasmid containing rns is not self-transmissible, it is mobilizable by IncFII plasmids (3). IncFII plasmids are sometimes present in enteric bacteria, so the opportunity exists for the rns plasmid to enter a new enteric host containing pCoo (39).

Evolution of pathogens.

A major mechanism of bacterial evolution is horizontal gene transfer. Such gene transfers can change the pathogenic character of a bacterial species. It seems likely that the CS1-expressing strain C921b-1 has obtained virulence factors through at least two separate horizontal gene transfer events.

The coo operon has a G+C content of 37%, which is considerably lower than the average for E. coli (50%) This implies that these genes were transferred to E. coli recently. DNA homologous to IS elements flanks the coo operon, suggesting that the coo operon could have been introduced into E. coli by transposition of this pathogenicity islet.

The positive regulator of the coo operon, rns, also has a very low G+C content (28%), suggesting that it many have been introduced into E. coli even more recently than the coo operon. Although it is not known whether there is DNA homologous to IS elements downstream of rns, there is DNA homologous to IS elements upstream of rns. Therefore, rns could also have been introduced into E. coli by transposition of a pathogenicity islet.

Since most of the IS elements surrounding coo and rns have mutations that would render them nonfunctional, the coo operon and rns can no longer be transferred to new strains by transposition of these pathogenicity islets. The coo and rns pathogenicity islet were inserted into separate plasmids, both of which are nonconjugative. The rns-containing plasmid is mobilizable, but the plasmid containing the coo operon, pCoo, is not.

Formation of conjugative pCoo by recombination with coresident R64 would allow transfer of the coo operon into new bacteria, where its presence could change the properties of the recipient strain. Even if the conjugative pCoo plasmid is not transferred to a strain that can express coo, it is possible that the strain could obtain the positive regulator needed by additional horizontal DNA transfer events, e.g., mobilization of the rns plasmid. Over time, the recipient of the conjugative pCoo could obtain, by horizontal DNA transfer, all of the genes necessary to cause disease. Once the strain has an activator of the coo operon, expression of the CS1 pili would allow the bacteria to bind to the human small intestine. If horizontal DNA transfer resulted in this CS1-expressing strain also receiving any other virulence genes necessary for disease, such as those encoding toxins, a new pathogen would be produced.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by grant AI24870 from the National Institutes of Health.

We thank Eileen Barry for ETEC strain 60R75 and Lilja Stefansson for technical help.

REFERENCES

- 1.Appleyard, R. K. 1954. Segregation of new lysogenic types during growth of a doubly lysogenic strain derived from Escherichia coli K12. Genetics 39:440-452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black, R. E. 1993. Epidemiology of diarrhoeal disease: implications for control by vaccines. Vaccine 11:100-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black, R. E. 1990. Epidemiology of travelers' diarrhea and relative importance of various pathogens. Rev. Infect. Dis. 12(Suppl. 1):873-879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boylan, M., and C. J. Smyth. 1985. Mobilization of CS fimbriae-associated plasmids of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of serotype O6:K15:H16 or H− into various wild-type hosts. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 29:83-89. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caron, J., L. M. Coffield, and J. R. Scott. 1989. A plasmid-encoded regulatory gene, rns, required for expression of the CS1 and CS2 adhesins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:963-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caron, J., D. R. Maneval, J. B. Kaper, and J. R. Scott. 1990. Association of Rrns homologs with colonization factor antigens in clinical Escherichia coli isolates. Infect. Immun. 58:3442-3444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caron, J., and J. R. Scott. 1990. A rns-like regulatory gene for colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) that controls expression of CFA/I pilin. Infect. Immun. 58:874-878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Disque-Kochem, C., and R. Eichenlaub. 1993. Purification and DNA binding of the D protein, a putative resolvase of the F-factor of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 237:206-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Froehlich, B., L. Husmann, J. Caron, and J. R. Scott. 1994. Regulation of rns, a positive regulatory factor for pili of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 176:5385-5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Froehlich, B. J., A. Karakashian, L. R. Melsen, J. C. Wakefield, and J. R. Scott. 1994. CooC and CooD are required for assembly of CS1 pili. Mol. Microbiol. 12:387-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furuichi, T., T. Komano, and T. Nisioka. 1984. Physical and genetic analyses of the Inc-Iα plasmid R64. J. Bacteriol. 158:997-1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaastra, W., and A. M. Svennerholm. 1996. Colonization factors of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli (ETEC). Trends Microbiol. 4:444-452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghosal, D., H. Sommer, and H. Saedler. 1979. Nucleotide sequence of the transposable DNA-element IS2. Nucleic Acids Res. 6:1111-1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gottesman, M. E., and M. Yarmolinsky. 1968. Integration-negative mutants of bacteriophage lambda. J. Mol. Biol. 31:487-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hama, C., T. Takizawa, H. Moriwaki, Y. Urasaki, and K. Mizobuchi. 1990. Organization of the replication control region of plasmid ColIb-P9. J. Bacteriol. 172:1983-1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto-Gotoh, T., M. Yamaguchi, K. Yasojima, A. Tsujimura, Y. Wakabayashi, and Y. Watanabe. 2000. A set of temperature sensitive-replication/-segregation and temperature resistant plasmid vectors with different copy numbers and in an isogenic background (chloramphenicol, kanamycin, lacZ, repA, par, polA). Gene 241:185-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hull, R. A., R. E. Gill, P. Hsu, B. H. Minshew, and S. Falkow. 1981. Construction and expression of recombinant plasmids encoding type 1 or d-mannose-resistant pili from a urinary tract infection Escherichia coli isolate. Infect. Immun. 33:933-938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hultgren, S. J., S. Normark, and S. N. Abraham. 1991. Chaperone-assisted assembly and molecular architecture of adhesive pili. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 45:383-415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ishiwa, A., and T. Komano. 2000. The lipopolysaccharide of recipient cells is a specific receptor for PilV proteins, selected by shufflon DNA rearrangement, in liquid matings with donors bearing the R64 plasmid. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263:159-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ishiwa, A., and T. Komano. 2003. Thin pilus PilV adhesins of plasmid R64 recognize specific structures of the lipopolysaccharide molecules of recipient cells. J. Bacteriol. 185:5192-5199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacob, A. E., J. A. Shapiro, L. Yamamoto, D. I. Smith, S. N. Cohen, and D. Berg. 1977. Plasmids studied in Escherichia coli and other enteric bacteria, p. 607. In A. I. Bukhari, J. A. Shapiro, and S. L. Adhya (ed.), DNA insertion elements, plasmids and episomes. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 22.Kim, S. R., and T. Komano. 1997. The plasmid R64 thin pilus identified as a type IV pilus. J. Bacteriol. 179:3594-3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Komano, T., S.-R. Kim, and T. Yoshida. 1995. Mating variation by DNA inversions of shufflon in plasmid R64. Adv. Biophys. 31:181-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Komano, T., S.-R. Kim, T. Yoshida, and T. Nisioka. 1994. DNA rearrangement of the shufflon determines recipient specificity in liquid mating of IncI1 plasmid R64. J. Mol. Biol. 243:6-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Komano, T., A. Kubo, T. Kayanuma, T. Furuichi, and T. Nisioka. 1986. Highly mobile DNA segment of IncIα plasmid R64: a clustered inversion region. J. Bacteriol. 165:94-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komano, T., A. Kubo, and T. Nisioka. 1987. Shufflon: multi-inversion of four contiguous DNA segments of plasmid R64 creates seven different open reading frames. Nucleic Acids Res. 15:1165-1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Komano, T., T. Yoshida, K. Narahara, and N. Furuya. 2000. The transfer region of IncI1 plasmid R64: similarities between R64 tra and Legionella icm/dot genes. Mol. Microbiol. 35:1348-1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambert, C. M., H. Hyde, and P. Strike. 1987. Conjugal mobility of the multicopy plasmids NTP1 and NTP16. Plasmid 18:99-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Le Dantec, C., N. Winter, B. Gicquel, V. Vincent, and M. Picardeau. 2001. Genomic sequence and transcriptional analysis of a 23-kilobase mycobacterial linear plasmid: evidence for horizontal transfer and identification of plasmid maintenance systems. J. Bacteriol. 183:2157-2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Levine, M. M. 1987. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J. Infect. Dis. 155:377-389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsutani, S., and E. Ohtsubo. 1990. Complete sequence of IS629. Nucleic Acids Res. 18:1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Messing, J., and J. Vieira. 1982. A new pair of M13 vectors for selecting either DNA strand of double-digest restriction fragments. Gene 19:269-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mullany, P., A. M. Field, M. M. McConnell, S. M. Scotland, H. R. Smith, and B. Rowe. 1983. Expression of plasmids coding for colonization factor antigen II (CFA II) and enterotoxin production in E. coli. J. Gen. Microbiol. 129:3591-3601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munson, G. P., L. G. Holcomb, and J. R. Scott. 2001. Novel group of virulence activators within the AraC family that are not restricted to upstream binding sites. Infect. Immun. 69:186-193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perez-Casal, J., M. G. Caparon, and J. R. Scott. 1991. Mry, a trans-acting positive regulator of the M protein gene of Streptococcus pyogenes with similarity to the receptor proteins of two-component regulatory systems. J. Bacteriol. 173:2617-2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Perez-Casal, J., J. S. Swartley, and J. R. Scott. 1990. Gene encoding the major subunit of CS1 pili of human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 58:3594-3600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pichel, M., N. Binsztein, and G. Viboud. 2000. CS22, a novel human enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli adhesin, is related to CS15. Infect. Immun. 68:3280-3285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Porter, M. E., S. G. Smith, and C. J. Dorman. 1998. Two highly related regulatory proteins, Shigella flexneri VirF and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli Rns, have common and distinct regulatory properties. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 162:303-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Radnedge, L., M. A. Davis, B. Youngren, and S. J. Austin. 1997. Plasmid maintenance functions of the large virulence plasmid of Shigella flexneri. J. Bacteriol. 179:3670-3675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rakin, A., and J. Heesemann. 1995. Virulence-associated fyuA/irp2 gene cluster of Yersinia enterocolitica biotype 1B carries a novel insertion sequence IS1328. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 129:287-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramer, S. W., G. K. Schoolnik, C. Y. Wu, J. Hwang, S. A. Schmidt, and D. Bieber. 2002. The type IV pilus assembly complex: biogenic interactions among the bundle-forming pilus proteins of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 184:3457-3465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schwartz, E., M. Kroger, and B. Rak. 1988. IS150: distribution, nucleotide sequence and phylogenetic relationships of a new E. coli insertion element. Nucleic Acids Res. 16:6789-6800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scott, J. R., and B. J. Froehlich. 1994. CS1 pili of enterotoxigenic E. coli, p. 17-30. In C. I. Kado and J. H. Crosa (ed.), Molecular mechanisms of bacterial virulence. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht, The Netherlands.

- 44.Scott, J. R., J. C. Wakefield, P. W. Russell, P. E. Orndorff, and B. J. Froehlich. 1992. CooB is required for assembly but not transport of CS1 pilin. Mol. Microbiol. 6:293-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smyth, C. J. 1982. Two mannose-resistant haemagglutinins on enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli of serotype O6:K16:H6 or H− isolate from travellers' and infantile diarrhea. J. Gen. Microbiol. 128:2081-2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Szpirer, C. Y., M. Faelen, and M. Couturier. 2000. Interaction between the RP4 coupling protein TraG and the pBHR1 mobilization protein Mob. Mol. Microbiol. 37:1283-1292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeshita, S., M. Sato, M. Toba, W. Masahashi, and T. Hashimoto-Gotoh. 1987. High-copy-number and low-copy-number plasmid vectors for lacZ alpha-complementation and chloramphenicol- or kanamycin-resistance selection. Gene 61:63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tobe, T., T. Hayashi, C. G. Han, G. K. Schoolnik, E. Ohtsubo, and C. Sasakawa. 1999. Complete DNA sequence and structural analysis of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adherence factor plasmid. Infect. Immun. 67:5455-5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Warren, G., and D. Sherratt. 1977. Complementation of transfer deficient ColE1 mutants. Mol. Gen. Genet. 151:197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yoshida, T., N. Furuya, M. Ishikura, T. Isobe, K. Haino-Fukushima, T. Ogawa, and T. Komano. 1998. Purification and characterization of thin pili of IncI1 plasmids ColIb-P9 and R64: formation of PilV-specific cell aggregates by type IV pili. J. Bacteriol. 180:2842-2848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yoshida, T., S. R. Kim, and T. Komano. 1999. Twelve pil genes are required for biogenesis of the R64 thin pilus. J. Bacteriol. 181:2038-2043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]