Abstract

The two obligate intracellular alphaproteobacteria Rickettsia prowazekii and Caedibacter caryophilus, a human pathogen and a paramecium endosymbiont, respectively, possess transport systems to facilitate ATP uptake from the host cell cytosol. These transport proteins, which have 65% identity at the amino acid level, were heterologously expressed in Escherichia coli, and their properties were compared. The results presented here demonstrate that the caedibacter transporter had a broader substrate than the more selective rickettsial transporter. ATP analogs with modified sugar moieties, dATP and ddATP, inhibited the transport of ATP by the caedibacter transporter but not by the rickettsial transporter. Both transporters were specific for di- and trinucleotides with an adenine base in that adenosine tetraphosphate, AMP, UTP, CTP, and GTP were not competitive inhibitors. Furthermore, the antiporter nature of both transport systems was shown by the dependence of the efflux of [α-32P]ATP on the influx of substrate (ATP but not dATP for rickettsiae, ATP or dATP for caedibacter).

The ability to exchange ATP and ADP across a biological membrane as a mechanism of energy transport is a hallmark of obligate intracellular bacterial parasites ranging from human pathogens such as rickettsiae and chlamydiae to the endosymbionts of protists such as Caedibacter caryophilus, a member of the Rickettsiales (6). This transport ability is also inherent in eukaryotic organelles whose ancestors were bacteria, such as plastids and mitochondria (13). The ATP/ADP transport systems of obligate intracellular organisms and plastids are analogous to, but evolutionarily distinct from, that of mitochondria (1). In addition, the mitochondria altruistically supply the host with energy by importing host cell ADP in exchange for mitochondrial ATP, whereas the nonmitochondrial transporters are used to scavenge energy from the host cell. Plasma or cell membrane-located ATP/ADP transport systems have not been found in free-living organisms. The lack of these transport systems seems appropriate, since ATP would not be readily available in the environments of these organisms. However, an explanation for the apparent exclusion of such a translocase from facultative intracellular bacteria is not as obvious. Perhaps the chance that a malfunction in the obligate exchange nature of these antiporters could provide a pathway for the loss of ATP when the facultative bacteria are extracellular is too great a risk.

The nonmitochondrial ATP/ADP translocases are at present the sole members of a distinct antiporter transport protein family in the classification scheme of Paulsen et al. (8). The first ATP/ADP translocase to be characterized was that of Rickettsia prowazekii, the etiological agent of epidemic typhus (11). Host cell cytosolic ATP that enters the bacteria is exchanged in a one-for-one manner for rickettsial ADP, so that the net effect is the uptake of a high-energy phosphate (11). This transporter (Tlc1) was subsequently cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli (5).

In this study, we extended our characterization of a novel translocase found in C. caryophilus, an endosymbiont of Paramecium spp. (9), and compared it with the well-characterized ATP/ADP transport system of R. prowazekii. The translocase of C. caryophilus can be examined only by heterologous expression in E. coli because methods to obtain isolated and functional C. caryophilus are not available. To facilitate our comparison of these two translocases, they were both cloned into pET vectors and expressed in the C41 strain of E. coli (a BL21[DE3] derivative) (7). With this approach, the uptake of ATP can be readily measured in a bacterium that is easily cultured in the laboratory and lacks any inherent ability to transport nucleotides. When appropriate, data for transport in native rickettsiae are also presented to confirm observations obtained when rickettsial Tlc1 was expressed and assayed in E. coli. The transport of [α-32P]ATP or [α-32P]dATP was routinely measured by membrane filtration at the Km substrate concentration unless otherwise indicated (10).

The rickettsial and caedibacter ATP/ADP transport systems share 65% identity and 78% similarity at the amino acid level (6). Interestingly, the 65% identity in amino acid sequences calculated for these two translocase homologs is the highest intergeneric identity yet found in the translocase homologs. Both R. prowazekii and C. caryophilus are obligate intracellular alphaproteobacteria with 84% similarity in their 16S rRNA sequences. Although the genome of C. caryophilus has not been sequenced, an examination of the sequence of the tlc gene suggests that C. caryophilus is a low-G+C organism with R. prowazekii-like codon usage (i.e., wobble positions are almost exclusively A or T) (14). Accordingly, the rickettsial and caedibacter translocase nucleotide sequences are 68% identical.

The caedibacter translocase recognizes ATP and dATP as substrates, whereas the rickettsial translocase does not recognize dATP.

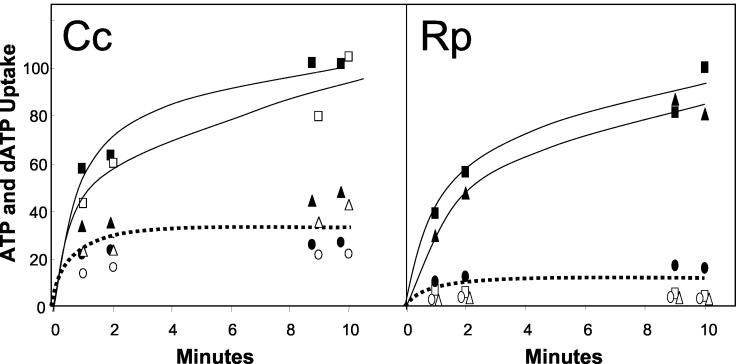

Both transporters are specific for substrates with adenine as the nucleobase and two or three phosphates. Neither transporter recognizes AMP, CXP, GXP, UXP (where X represents mono-, di-, or triphosphates), dCTP, dTTP, dGTP, or adenosine tetraphosphate (A4P) as a substrate (reference 11 and data not shown) (see Fig. 2). However, the transporter of C. caryophilus will transport dATP, whereas the rickettsial transporter is specific for the ribose moiety (Fig. 1). This finding came as a surprise considering the high degree of identity shared between the two translocases. In the case of C. caryophilus Tlc, ATP transport is inhibited by both ATP and dATP and the transport of dATP is inhibited by both ATP and dATP (Fig. 1). The Kms for ATP and dATP transport by the caedibacter system expressed in E. coli are 180 μM and 1 mM, respectively. The Kms for rickettsial ATP transport are 75 μM for the native organism and 100 μM when such transport is heterologously expressed in E. coli (4, 11). Again, the inability to isolate functional C. caryophilus has precluded the measurement of transport activity under native conditions.

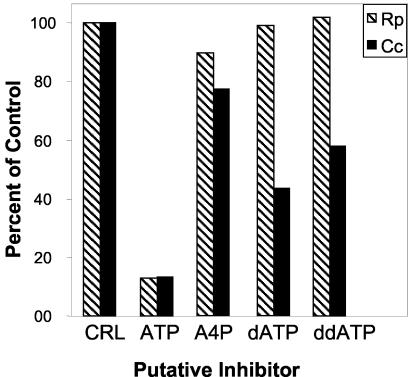

FIG. 2.

The specificity of the caedibacter and rickettsial translocases was analyzed by using ATP, dATP, ddATP, and A4P. Each of the rickettsial (Rp) and caedibacter (Cc) translocase genes cloned into a pET expression vector (pET11a-Rptlc1 and pET16b-Cctlc1) was introduced into the C41 strain of E. coli. These strains were grown, washed, and assayed for ATP uptake at their respective Km concentrations as described in the legend to Fig. 1. The putative competitive inhibitors were used at 1 (Rp) and 1.8 (Cc) mM, 10 times the respective Kms for ATP.

FIG. 1.

The effects of excess ATP and dATP on ATP and dATP transport by rickettsial and caedibacter translocase. Cc, an E. coli C41 strain transformed with pET16b-Cctlc1 (encoding the caedibacter translocase) was grown in Luria-Bertani media containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml) to an optical density at nm of 0.6, and 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) was added to induce protein expression. After 1 h of induction, bacterial cells were collected by centrifugation and washed once in an equal volume of 50 mM potassium phosphate (KPi) buffer (pH 7.5). Cells were assayed for ATP and dATP uptake by measuring the accumulation of [α32P]ATP (filled squares) and [α32P]dATP (open squares) at Km concentrations by a standard filtration method (10). Unlabeled ATP (filled circles for ATP uptake, open circles for dATP uptake) or unlabeled dATP (filled triangles for ATP, open triangles for dATP uptake) was added as a competitive inhibitor at 10 times the Km concentration. All data are expressed as percentages of the control values, which were 1.0 and 1.2 nmol mg of protein−1 for ATP and dATP, respectively. Rp, R. prowazekii cells were purified from yolk sacs (11) and tested for ATP and dATP uptake as described above (10). Purified rickettsiae were assayed for ATP and dATP uptake by measuring the accumulation of [α32P]ATP (filled squares) and [α32P]dATP (open squares) at 100 μM. Other symbols are as described above, and those for the lowest curve have been offset for clarity. All data are expressed as percentages of the control value, which was 7.0 nmol mg of protein−1 for ATP (dATP was not a substrate).

The recognition of dATP by the C. caryophilus translocase prompted us to test ddATP as a putative competitive inhibitor of ATP uptake on both transporters when present at a concentration of 10 times the Km for ATP (1 and 1.8 mM) (Fig. 2). Only the caedibacter transporter displayed an appreciable affinity for compounds with modified ribose moieties. In addition, A4P was used to probe specificity at the phosphate moiety (Fig. 2). Both the rickettsial and caedibacter transporters are restricted to recognizing only the di- and triphosphates and not the mono- or tetraphosphates. In toto, these results indicate that the caedibacter transporter does discriminate based on the number of phosphates present on the molecule but has a more relaxed specificity for recognition of the sugar moiety than the rickettsial transporter.

Both the rickettsial and the caedibacter translocases are obligate exchange antiporters.

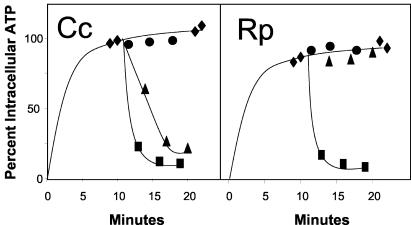

To verify the obligate exchange nature of these translocases, we performed efflux assays in which cells were preincubated for loading with [α-32P]ATP and then diluted 250-fold in buffer with or without substrate. The 1:1 exchange and the identities of the exchanged compounds were not measured but were assumed. Both the rickettsial and the caedibacter transporters showed no efflux of substrate from a large intracellular pool in the absence of exchangeable substrate in the medium (Fig. 3). However, as expected, a marked efflux of labeled ATP or dATP was observed in the caedibacter system upon the addition of an exchangeable substrate, ATP or dATP, to the medium (Fig. 3). On the other hand, ATP, but not dATP, was able to evoke the efflux of ATP in the rickettsial system. Thus, both the caedibacter and the rickettsial translocases are antiporters that provide the cell with energy and do not catalyze the net uptake of adenylates.

FIG. 3.

ATP and dATP efflux assays. Each of the rickettsial (Rp) and caedibacter (Cc) translocase genes cloned into a pET expression vector (pET16b-Cctlc1 and pET11a-Rptlc1) were introduced into the C41 strain of E. coli and grown as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Cells expressing the caedibacter Tlc (left) and cells expressing the rickettsial Tlc (right) were incubated with [α32P]ATP for 10 min at room temperature to preload the cells. An aliquot of preloaded cells was then diluted 250-fold into potassium phosphate (KPi) buffer alone (filled circles), KPi buffer with 1 mM ATP (filled squares), or KPi buffer with 1 mM dATP (filled triangles). The amount of radioactivity remaining inside the cells over time was measured by the filtration assay described above. All data are expressed as percentages of the control value, which was 1.2 nmol mg of protein−1.

Remarks.

Rickettsiae neither synthesize de novo nor transport deoxyribonucleotides, but rather transport ribonucleotides (12), and they use ribonucleotide reductase to form the deoxyribonucleotides (3). Although the nucleotide metabolism of caedibacter has not been characterized, it is questionable whether natural selection for the transport of dATP has played any role in the acquisition of this specificity in C. caryophilus. An influx of dATP in exchange for ATP would provide the caedibacter cell with a deoxynucleotide. However, this is an unlikely function if caedibacters, like rickettsiae, have a functional ribonucleotide reductase. Indeed, the exquisite regulation retained by the ribonucleotide reductase of R. prowazekii (3), an organism that possess several examples of genes that have undergone “evolutionary meltdown” (2), reflects the necessity of having a balanced repertoire of dNTPs for DNA synthesis. If dNTPs were transported into C. caryophilus in exchange for ribonucleotides, the ratio of the four dNTPs in the bacterial cytosol would reflect the properties of the various transport systems as well as the ratio of dNTPs in its niche. However, it seems likely that the uptake of dATP would always be inhibited by the higher concentration of ATP.

The alternative explanation is that in comparison to its rickettsial cousin, the caedibacter ATP/ADP transport protein just evolved to have more relaxed demands for substrate specificity with a protein-substrate fit at the binding site that allows the recognition of compounds with modifications of the ribose moiety. Thus, the transport of dATP is insignificant for the biology of the caedibacter but represents an exciting avenue by which to approach an analysis of the molecular basis of substrate specificity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grant AI-15035 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to H.H.W. Work in the laboratory of H.E.N. was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amiri, H., O. Karlberg, and S. G. Andersson. 2003. Deep origin of plastid/parasite ATP/ADP translocases. J. Mol. Evol. 56:137-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson, S. G. E., A. Zomorodipour, J. O. Andersson, T. Sicheritz-Ponten, U. C. M. Alsmark, R. M. Podowdki, A. K. Naslund, A.-S. Eriksson, H. H. Winkler, and C. G. Kurland. 1998. The genome sequence of Rickettsia prowazekii and the origin of mitochondria. Nature 396:133-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cai, J., R. R. Speed, and H. H. Winkler. 1991. Reduction of ribonucleotides by the obligate intracytoplasmic bacterium Rickettsia prowazekii. J. Bacteriol. 173:1471-1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunbar, S. A., and H. H. Winkler. 1997. Increased and controlled expression of the Rickettsia prowazekii ATP/ADP translocase and analysis of cysteine-less mutant translocase. Microbiology 143:3661-3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krause, D. C., H. H. Winkler, and D. O. Wood. 1985. Cloning and expression of the Rickettsia prowazekii ADP/ATP translocator in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82:3015-3019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Linka, N., H. Hurka, B. F. Lang, G. Burger, H. H. Winkler, C. Stamme, C. Urbany, I. Seil, J. Kusch, and H. E. Neuhaus. 2003. Phylogenetic relationships of non-mitochondrial nucleotide transport proteins in bacteria and eukaryotes. Gene 306:27-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miroux, B., and J. E. Walker. 1996. Over-production of proteins in Escherichia coli: mutant hosts that allow synthesis of some membrane proteins and globular proteins at high levels. J. Mol. Biol. 260:289-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paulsen, I. T., L. Nguyen, M. K. Sliwinski, R. Rabus, and M. H. Saier, Jr. 2000. Microbial genome analyses: comparative transport capabilities in eighteen prokaryotes. J. Mol. Biol. 301:75-100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preer, J. R., and L. B. Preer. 1984. Endosymbionts of protozoa. Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore, Md.

- 10.Winkler, H. H. 1986. Membrane transport in rickettsiae. Methods Enzymol. 125:253-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Winkler, H. H. 1976. Rickettsial permeability: an ADP-ATP transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 251:389-396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Winkler, H. H., R. Daugherty, and F. Hu. 1999. Rickettsia prowazekii transports UMP and GMP, but not CMP, as building blocks for RNA synthesis. J. Bacteriol. 181:3238-3241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Winkler, H. H., and H. E. Neuhaus. 1999. Non-mitochondrial adenylate transport: a plant plastid to obligate intracellular bacterium connection. Trends Biochem. Sci. 277:64-68. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winkler, H. H., and D. O. Wood. 1988. Codon usage in selected AT-rich bacteria. Biochimie 70:977-986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]