Abstract

Aim:

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) has a wide range of biological functions, including anti-inflammation. In this study, we investigated the inhibitory effects of PPAR-γ on transforming growth factor β1 (TGF-β1)-induced interleukin-8 (IL-8) and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) expression in renal tubular epithelial cells (HK-2).

Methods:

HK-2 cells were pretreated with 15d-PGJ2 or troglitazone (TGL) and then treated with TGF-β1. Expression of MCP-1 and IL-8 was measured using real-time PCR and ELISA.

Results:

Treatment with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for 24 h increased both MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA and protein levels in HK-2 cells. Both 15d-PGJ2 at 2.5 and 5 μmol/L and TGL at 2.5 μmol/L exhibited inhibitory effects on TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 expression. Additionally, 15d-PGJ2 at 2.5 and 5 μmol/L and TGL at 2.5 μmol/L inhibited TGF-β1-induced expression of IL-8.

Conclusion:

PPAR-γ agonists (15d-PGJ2 and TGL) could inhibit the TGF-β1-induced expression of chemokines in HK-2 cells. Our results suggest that PPAR-γ agonists have the potential to be used as a treatment regimen to reduce inflammation in renal tubulointerstitial disease.

Keywords: peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, 15d-PGJ2, troglitazone, transforming growth factor β1, tubular epithelial cell, chemokine, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, interleukin-8

Introduction

Tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis play important roles in the progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD) and are closely associated with the prognosis of kidney diseases1, 2, 3. Transforming growth factor–β1 (TGF-β1) is one of the most important cytokines that participate in tubulointerstitial inflammation and fibrosis. It has been demonstrated that chemokines, including monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) and interleukin-8 (IL-8), are closely related to tubulointerstitial lesions4, 5, 6, 7.

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ), a member of the ligand-activated transcription factor superfamily, is expressed in many organs, including the kidney8, 9. In our previous study, we demonstrated that PPAR-γ could counteract the profibrogenic effects of TGF-β1 in the kidney10, 11. Furthermore, it has been found that activation of PPAR-γ has anti-inflammatory effects in inflammatory bowel disease, arthritis and multiple sclerosis12, 13, 14, 15, 16. However, the anti-inflammatory effects of PPAR-γ in kidney diseases remain unclear. In the current study, we aimed to investigate the anti-inflammatory effects of PPAR-γ in kidney diseases by examining the effects of 15d-PGJ2 (a natural ligand of PPAR-γ) and troglitazone (TGL) on TGF-β1−induced chemokine expression in renal tubular epithelial cells.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

Human proximal tubular cells (HK-2, CRL-2190) were purchased from ATCC and grown in keratinocyte serum-free media (KSFM, Invitrogen) supplemented with bovine pituitary extract (BPE, Invitrogen) and epidermal growth factor (EGF, Invitrogen). The cells were cultured in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2 and passaged at 80% confluence using 0.05% trypsin-0.02% EDTA (Invitrogen).

To investigate the fibrogenic effect of TGF-β1 on the HK-2 cells, the cells were seeded into 6-well culture dishes and incubated with KSFM without BPE and EGF for 24 h to arrest and synchronize cell growth. After the 24 h, cells were treated with TGF-β1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) at different concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 ng/mL) for 24 h or treated with 5 ng/mL TGF-β1 for different time intervals (0, 2, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h). Cells were then harvested for further experimentation.

RT-PCR and real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from HK-2 cells using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. The RNA was eluted with RNase-free water. Reverse transcription was performed using a standard reagent (Promega) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Real-time PCR amplification was performed using the SYBR Green master mix (Toyobo, Japan) and the Opticon 3 Real-time PCR Detection System (Bio-rad). Cycling conditions were 94 °C for 5 min followed by 44 cycles of 94 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min. A final extension at 72 °C for 10 min was performed after the cycles were completed. Primers for amplifying GAPDH, MCP-1 and IL-8 were designed using Primer software and validated for specificity. Primer sequences are summarized in Table 1. Relative amounts of mRNA were normalized to GAPDH levels and calculated using the delta-delta method from the threshold cycle numbers. Levels in the control experiments were set to 1, and all the other values are expressed as multiples thereof.

Table 1. The primers for the real-time PCR.

| Gene | Primer sequence | Product length (bp) | Tm (°C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | Forward | 5′-CAGGGCTGCTTTTAACTCTGGTAA-3′ | 101 | 60 |

| Reverse | 5′-GGGTGGAATCATATTGGAACATGT-3′ | |||

| MCP-1 | Forward | 5′-CAGCCAGATGCAATCAATGC-3′ | 198 | 60 |

| Reverse | 5′-GTGGTCCATGGAATCCTGAA-3′ | |||

| IL-8 | Forward | 5′-GAATTGAATGGGTTTGCTAGA-3′ | 229 | 60 |

| Reverse | 5′-CACTGTGAGGTAAGATGGTGG-3′ |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Commercial ELISA kits (Biosource, USA) were used to detect the level of MCP-1 and IL-8 in the supernatant of HK-2 cells according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as the means±SD. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows 11.0 (SPSS, Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical analyses between two groups were assessed by t-test. Statistical analyses among groups were assessed by ANOVA. P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Dose- and time-dependent effects of TGF-β1 on MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA in HK-2 cells

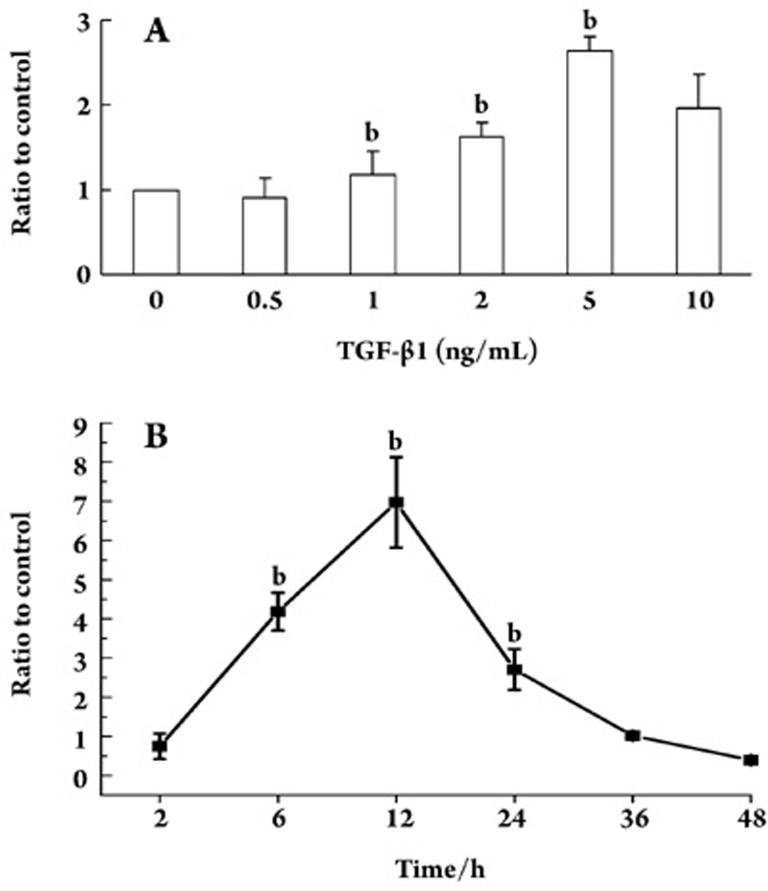

Untreated HK-2 cells expressed a basal level of both MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA. When HK-2 cells were treated with different concentrations of TGF-β1 for 24 h, the level of MCP-1 mRNA increased above basal levels with 2 ng/mL, peaked with 5 ng/mL and decreased with 10 ng/mL of TGF-β1, which corresponded to 1.64-, 2.65-, and 1.95-fold increases in MCP-1 mRNA levels, respectively (Figure 1A). When HK-2 cells were treated with 5 ng/mL of TGF-β1 for different time periods, MCP-1 mRNA expression increased at 6 h, peaked at 12 h and decreased after 24 h. No significant difference in MCP-1 expression was found at 36 h between the TGF-β1-treated and control groups (P>0.05, Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

The effects of TGF-β1 on MCP-1 mRNA expression in HK-2 cells. The effects of different dosages of TGF-β1 (0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 ng/mL) on MCP-1 mRNA expression. (B) The effects of different durations of treatment with TGF-β1 (2, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48 h) on MCP-1 mRNA expression. bP<0.05 vs TGF-β1 control group.

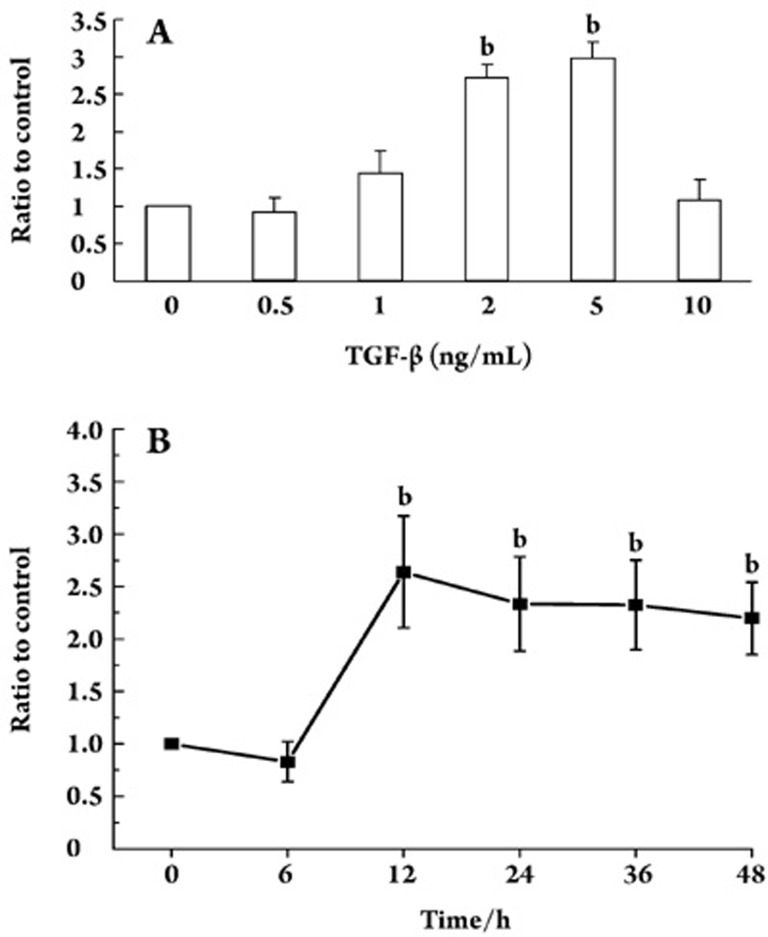

When HK-2 cells were treated with different concentrations of TGF-β1 for 24 h, IL-8 mRNA levels increased with 1 ng/mL, peaked with 5 ng/mL and decreased with 10 ng/mL of TGF-β1 (Figure 2A). Treatment of the HK-2 cells with 5 ng/mL of TGF-β1 increased IL-8 mRNA levels by 2.64 fold at 12 h (P<0.01) and by 2.19 fold at 48 h (P<0.01) (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

The effects of TGF-β1 on IL-8 mRNA expression in HK-2 cells. (A) The effects of different dosages of TGF-β1 (0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 ng/mL) on IL-8 mRNA expression. (B) The effects of different durations of treatment with TGF-β1 (6, 12, 24, 36, 48 h) on IL-8 mRNA expression. bP<0.05 vs TGF-β1 control group.

Effects of TGF-β1 on MCP-1 and IL-8 protein levels in HK-2 supernatants

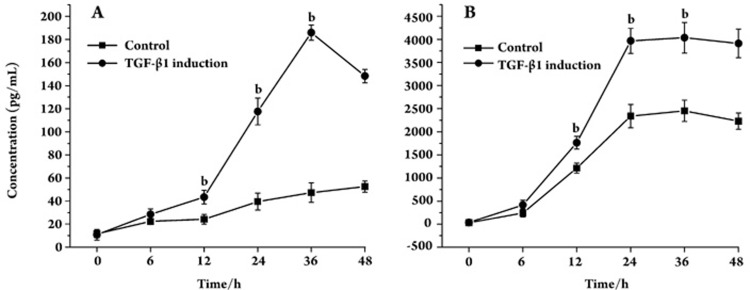

After 12 h of treatment with TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL), the levels of MCP-1 in cell supernatants increased from 10.68 pg/mL to 43.39 pg/mL at 12 h, to 185.91 pg/mL at 36 h, and decreased to 148.31 pg/mL at 48 h (Figure 3A). TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) also upregulated the level of IL-8 protein in supernatants at 12 h (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

The level of MCP-1 and IL-8 after TGF-β1 treatment. (A) The level of MCP-1 in the supernatant after different durations of TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) treatment. (B) The level of IL-8 in the supernatant after different durations of TGF-β1 (5 ng/mL) treatment. bP<0.05 vs TGF-β1 control group.

Inhibitory effects of TGL and 15d-PGJ2 on TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA expression in HK-2 cells

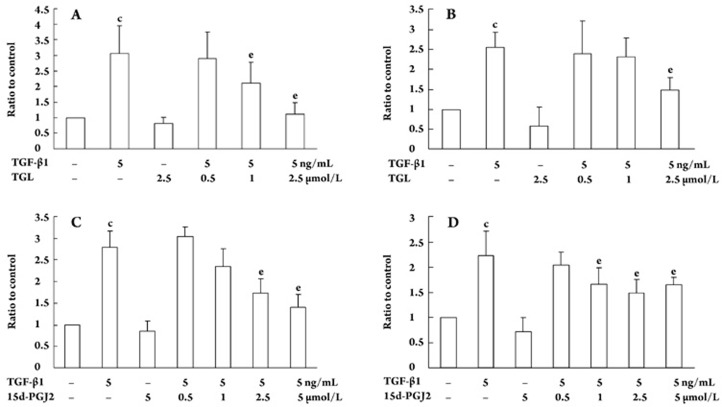

Treatment of HK-2 cells with 5 ng/mL of TGF-β1 for 24 h significantly increased the MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA levels. Treatment of HK-2 cells with 1 μmol/L or 2.5 μmol/L TGL for 24 h significantly decreased the TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 mRNA level (P<0.05, Figure 4A). Treatment of HK-2 cells with 2.5 μmol/L of TGL for 24 h decreased TGF-β1-induced IL-8 mRNA levels from 2.55-fold to 1.49-fold (P<0.05, Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

The effect of TGL and 15d-PGJ2 on TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 and IL-8 mRNA expression in HK-2 cells (24 h). The mRNA level of MCP-1 (A) and IL-8 (B) in HK-2 cells after different concentrations of TGL treatment. The mRNA level of MCP-1(C) and IL-8 (D) in HK-2 cells after different concentrations of 15d-PGJ2 treatment. n=3. Mean±SD. cP<0.01 vs control. eP<0.05 vs TGF-β1 induction group.

Treatment of HK-2 cells with 2.5 μmol/L or 5 μmol/L of 15d-PGJ2 for 24 h decreased the TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 mRNA level (P<0.05, Figure 4C). Treatment of HK-2 cells with 1, 2.5, or 5 μmol/L of 15d-PGJ2 for 48 h decreased the TGF-β1-induced IL-8 mRNA level (P<0.05, Figure 4D).

Inhibitory effects of TGL and 15d-PGJ2 on level of TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 and IL-8 in supernatant

Treatment of HK-2 cells with 2.5 μmol/L of TGL or 2.5 or 5 μmol/L of 15d-PGJ2 for 24 h significantly decreased the levels of TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 in the supernatant (P<0.05). Furthermore, a significant difference in the level of inhibition was observed between the groups of HK-2 cells treated with the 5 and 2.5 μmol/L doses of 15d-PGJ2 (P<0.05). Similarly, treatment of HK-2 cells with 2.5 μmol/L of TGL or with 5 μmol/L of 15d-PGJ2 for 24 h significantly decreased the levels of TGF-β1-induced IL-8 protein in the supernatant (P<0.01) (Table 2 and Table 3).

Table 2. The effects of TGL and 15d-PGJ2 on MCP-1 level induced by TGF-β1. n=3 independent experiments. Mean±SD. cP<0.01 vs control; fP<0.01 vs TGF-β1 induction group.

| Groups | Concentration (pg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Control | 21.36 ± 6.51 |

| TGF-β1 | 56.17±14.31c |

| TGF-β1+15d-PGJ2 (2.5 μmol/L) | 29.30±11.72f |

| TGF-β1+15d-PGJ2 (5 μmol/L) | 14.09±4.50f |

| TGF-β1+TGL (2.5 μmol/L) | 22.82±12.39f |

| 15d-PGJ2 (5 μmol/L) | 15.08±4.38 |

| TGL (2.5 μmol/L) | 12.57±4.60 |

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and each sample was tested by two ELISA wells.

Table 3. The effects of TGL and 15d-PGJ2 on IL-8 level induced by TGF-β1. n=3 independent experiments. Mean±SD. c P<0.01 vs control; fP<0.01 vs TGF-β1 induction group.

| Groups | Concentration (pg/mL) |

|---|---|

| Control | 2423.78±887.71 |

| TGF-β1 | 3544.42±721.05c |

| TGF-β1+15d-PGJ2 (2.5 μmol/L) | 2762.36±817.99 |

| TGF-β1+15d-PGJ2 (5 μmol/L) | 1982.54±595.06f |

| TGF-β1+TGL (2.5 μmol/L) | 2042.97±827.34f |

| 15d-PGJ2 (5 μmol/L) | 1775.16±449.96 |

| TGL (2.5 μmol/L) | 1847.69±604.33 |

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and each sample was tested by two ELISA wells.

Discussion

Tubular epithelial cells play an important role in tubulointerstitial fibrosis by secreting cytokines and extra-cellular matrix. TGF-β1, which has a wide spectrum of biological functions, is one of the most important cytokines in this process. Recent studies suggest that chemokines, such as MCP-1 and IL-8, are closely associated with kidney diseases, and tubular epithelial cells are the predominant secretors of these chemokines17, 18. MCP-1 and IL-8 cause tubulointerstitial lesions by recruiting target cells, which include macrophages/monocytes, T cells, neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils, into the tubulointerstitium, where the target cells secrete cytokines, including TGF-β1 and TNF-α19, 20, 21, 22. However, recent studies on TGF-β1-induced chemokine secretion by tubular epithelial cells had contradictory results. Gerritsma JS and colleagues demonstrated that TGF-β1 increased the level of IL-8, but decreased the level of MCP-123. However, in a study published by Qi et al, IL-8 and MCP-1 expression was upregulated after TGF-β1 treatment24.

In our previous studies, we demonstrated that TGF-β1 increased ECM synthesis in renal interstitial fibroblasts25. However, it is not clear whether TGF-β1 recruits inflammatory cells and leads to their infiltration into the tubulointerstitium by upregulating cytokine secretion. In the current study, we investigated the expression of MCP-1 and IL-8 in HK-2 cells after stimulation with TGF-β1. Our results showed that HK-2 cells expressed basal levels of MCP-1 and IL-8, which agrees with results from previously published studies26, 27. In this study, we demonstrated that TGF-β1 upregulated the expression of MCP-1 and IL-8 in HK-2 cells. Our results from this study are consistent with our previous studies that demonstrated that TGF-β1 had proinflammatory and profibrogenic effects on HK-2 cells. Our results are also consistent with the study, for example, published by Qi and colleagues24. Recent studies suggest that increased expression of MCP-1 is found in several renal diseases20, 21, supporting the concept that TGF-β1 upregulates expression of MCP-1 in tubular epithelia. In the studies published by Gerritsma et al and Qi et al23, 24, the expression of IL-8 in tubular epithelial cells was upregulated after 48 h or 72 h of TGF-β1 stimulation. Their results are similar to our findings, suggesting that secretion of MCP-1 and IL-8 by tubular epithelial cells plays an important role in tubulointerstitial fibrosis and lesion formation24.

PPAR-γ is a member of the ligand-activated transcription factor superfamily, which participates in a wide range of biological activities, including cell differentiation, fat metabolism, glucose metabolism, immune response regulation, inflammation, cell apoptosis and tumorigenesis28, 29. PPAR-γ had some anti-inflammatory effects on inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis30, 31. It ameliorates the inflammatory cell infiltration and downregulates the proinflammatory cytokine expression in animal models of diabetic nephropathy and lupus nephropathy as well as in mesangial cells, fibroblasts and tubular epithelial cells32, 33. Li and colleagues demonstrated that eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) could downregulate LPS-induced MCP-1 expression via the PPAR-γ pathway34. In this study, we demonstrated that treatment with either 15d-PGJ2 or TGL counteracts the TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 and IL-8 expression. These findings suggest that PPAR-γ has an inhibitory effect on MCP-1 expression. Our results are similar to those reported by Zafiriou et al, who demonstrated that pioglitazone downregulates TGF-β1-induced MCP-1 expression in OK cells and that such effects did not depend on NF-κB activity35. However, our results are different from those of the study reported by Fu et al, who found that 15d-PGJ2 upregulated the expression of IL-8 in macrophages31. Our results suggest that different mechanisms of PPAR-γ may occur in different cell types. To date, the molecular details of the antagonizing effects of PPAR-γ on TGF-β1-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression are unclear. In our previous study25, we demonstrated that PPAR-γ could counteract the profibrogenic effects of TGF-β1 by downregulating the phosphorylation of Smad 2 and Smad 3. Therefore, the anti-inflammatory effects of PPAR-γ on TGF-β1-induced inflammation might target Smad signaling. However, further study is needed to fully elucidate the detailed mechanism by which this process occurs.

We demonstrated that TGF-β1 induced the expression of chemokines in tubular epithelial cells and inflammatory cells. Inflammatory cells participate in tubulointerstitial lesions by infiltrating into the tubulointerstitium mediated by the chemokine receptors on their surface. Both 15d-PGJ2 and TGL had inhibitory effects on MCP-1 and IL-8 expression. Our studies suggest that inhibiting TGF-β1−induced chemokine expression might have therapeutic effects on tubulointerstitial lesions and thus could potentially be used as a regimen for treating chronic kidney disease.

Author contribution

Wei-ming WANG and Nan CHEN designed research; Hui-di ZHANG, Yuan-meng JIN, Bing-bing ZHU performed research; Wei-ming WANG and Hui-di ZHANG contributed new analytical tools and reagents; Wei-ming WANG and Hui-di ZHANG analyzed data; Wei-ming WANG wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30270613 and 30771000), the Leading Academic Discipline Project of Shanghai Health Bureau (05III001 and 2003ZD002) and the Shanghai Leading Academic Discipline Project (T0201), China.

References

- Remuzzi G, Bertani T. Pathophysiology of progressive nephropathies. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:1448–56. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199811123392007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohle A, Muller GA, Wehrmann M, Mackensen-Haen S, Xiao JC. Pathogenesis of chronic renal failure in the primary glomerulopathies, renal vasculopathies, and chronic interstitial nephritides. Kidney Int. 1996. pp. S2–9. [PubMed]

- Nath KA. Tubulointerstitial changes as a major determinant in the progression of renal damage. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:1–17. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(12)80312-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Koka V, Lan HY. Transforming growth factor-beta and Smad signalling in kidney diseases. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005;10:48–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. Renal fibrosis: new insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int. 2006;69:213–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf G. Renal injury due to renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system activation of the transforming growth factor-beta pathway. Kidney Int. 2006;70:1914–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5001846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panzer U, Steinmetz OM, Stahl RA, Wolf G. Kidney diseases and chemokines. Curr Drug Targets. 2006;7:65–80. doi: 10.2174/138945006775270213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan Y, Breyer MD. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): novel therapeutic targets in renal disease. Kidney Int. 2001;60:14–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eun CS, Han DS, Lee SH, Paik CH, Chung YW, Lee J, et al. Attenuation of colonic inflammation by PPARgamma in intestinal epithelial cells: effect on Toll-like receptor pathway. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51:693–7. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-3193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WM, Liu F, Chen N. The effects of peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ agonists on TGF-β1-Smads signal pathway in rat renal fibroblasts. Natl Med J China. 2006;86:740–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Wang WM, Chen N. The effects of peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor γ agonists on TGF-β1-induced extracellular matrix expression in renal fibroblasts. J Nephrol Dialy Transplant. 2006;15:30–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan XZ, Varghese Z, Powis SH, Moorhead JF. Nuclear receptors and their coregulators in kidney. Kidney Int. 2005;68:2444–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Moser AH, Shigenaga JK, Feingold KR, Grunfeld C. Type II nuclear hormone receptors, coactivator, and target gene repression in adipose tissue in the acute-phase response. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:2179–90. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500540-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass CK, Ogawa S. Combinatorial roles of nuclear receptors in inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:44–55. doi: 10.1038/nri1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tien ES, Hannon DB, Thompson JT, Vanden Heuvel JP. Examination of ligand-dependent coactivator recruitment by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha (PPARalpha) PPAR Res. 2006;2006:69612–20. doi: 10.1155/PPAR/2006/69612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han SJ, Jung SY, Malovannaya A, Kim T, Lanz RB, Qin J, et al. A scoring system for the follow up study of nuclear receptor coactivator complexes. Nucl Recept Signal. 2006;4:e014. doi: 10.1621/nrs.04014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerer S, Nelson PJ, Schlondorff D. Chemokines, chemokine receptors, and renal disease: from basic science to pathophysiologic and therapeutic studies. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:152–76. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V111152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daha MR, van Kooten C. Is the proximal tubular cell a proinflammatory cell. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2000. pp. 41–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang SN, LaPage J, Hirschberg R. Role of glomerular ultrafiltration of growth factors in progressive interstitial fibrosis in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2000;57:1002–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesch GH, Schwarting A, Kinoshita K, Lan HY, Rollins BJ, Kelley VR. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 promotes macrophage-mediated tubular injury, but not glomerular injury, in nephrotoxic serum nephritis. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:73–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viedt C, Orth SR. Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1) in the kidney: does it more than simply attract monocytes. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:2043–7. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.12.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandaliano G, Gesualdo L, Ranieri E, Monno R, Montinaro V, Marra F, et al. Monocyte chemotactic peptide-1 expression in acute and chronic human nephritides: a pathogenetic role in interstitial monocytes recruitment. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1996;7:906–13. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V76906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsma JS, Hiemstra PS, Gerritsen AF, Prodjosudjadi W, Verweij CL, Van Es LA, et al. Regulation and production of IL-8 by human proximal tubular epithelial cells in vitro. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996;103:289–94. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-617.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi W, Chen X, Polhill TS, Sumual S, Twigg S, Gilbert RE, et al. TGF-beta1 induces IL-8 and MCP-1 through a connective tissue growth factor-independent pathway. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F703–709. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00254.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Liu F, Chen N. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma (PPAR-gamma) agonists attenuate the profibrotic response induced by TGF-beta1 in renal interstitial fibroblasts. Mediators Inflamm. 2007;2007:62641–7. doi: 10.1155/2007/62641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deckers JG, Va Der Woude FJ, Van Der Kooij SW, Daha MR. Synergistic effect of IL-1alpha, IFN-gamma, and TNF-alpha on RANTES production by human renal tubular epithelial cells in vitro. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:194–202. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V92194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SN, Lapage J, Hirschberg R. Glomerular ultrafiltration and apical tubular action of IGF-I, TGF-beta, and HGF in nephrotic syndrome. Kidney Int. 1999;56:1247–51. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehrke M, Lazar MA. The many faces of PPARgamma. Cell. 2005;123:993–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrero A, Laguna JC, Vazquez M. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and the control of inflammation. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2002;1:243–8. doi: 10.2174/1568010023344616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuquoy L, Rousseaux C, Thuru X, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Romano O, Chavatte P, et al. PPARgamma as a new therapeutic target in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gut. 2006;55:1341–9. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.093484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Luo N, Lopes-Virella MF. Upregulation of interleukin-8 expression by prostaglandin D2 metabolite 15-deoxy-delta12, 14 prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) in human THP-1 macrophages. Atherosclerosis. 2002;160:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00541-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung BH, Lim SW, Ahn KO, Sugawara A, Ito S, Choi BS, et al. Protective effect of peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma agonists on diabetic and non-diabetic renal diseases. Nephrology (Carlton) 2005. 10 Suppl:S40–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2005.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong Z, Huang H, Li J, Guan Y, Wang H. Anti-inflammatory effect of PPARgamma in cultured human mesangial cells. Ren Fail. 2004;26:497–505. doi: 10.1081/jdi-200031747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Ruan XZ, Powis SH, Fernando R, Mon WY, Wheeler DC, et al. EPA and DHA reduce LPS-induced inflammation responses in HK-2 cells: evidence for a PPAR-gamma-dependent mechanism. Kidney Int. 2005;67:867–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00151.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zafiriou S, Stanners SR, Polhill TS, Poronnik P, Pollock CA. Pioglitazone increases renal tubular cell albumin uptake but limits proinflammatory and fibrotic responses. Kidney Int. 2004;65:1647–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]