Abstract

Purpose of review

With the realization that lipid droplets (LDs) are not merely inert fat storage organelles, but highly dynamic and actively involved in cellular lipid homeostasis, there has been an increased interest in LD biology. Recent studies have begun to unravel the roles that LDs play in cellular physiology and provide insights into the mechanisms by which LDs contribute to cellular homeostasis. This review provides a summary of these recent publications on LD metabolism.

Recent findings

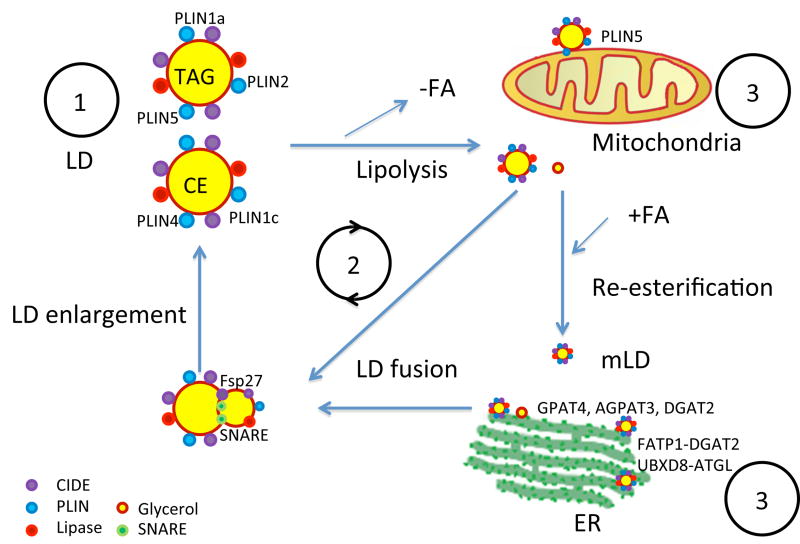

PLINs have different preferences for associating with triacylglycerol (TAG) or cholesteryl esters (CE), different tissue distributions, and each contributes to lipid metabolism in its unique way. CIDE proteins are not only involved in LD expansion, but also in the cellular response to stress and lipid secretion. LDs undergo an active cycle of lipolysis and re-esterification to form microLDs. TAG synthesis for LD formation and expansion occurs in the ER and on LDs, and TAG transfers between LDs during LD fusion. LDs interact with the ER and mitochondria to facilitate lipid transfer, LD expansion and metabolism.

Summary

LDs are dynamically active, responding to changes in cellular physiology, as well as interacting with cytosolic proteins and other organelles to control lipid homeostasis.

Keywords: LD proteins, PLIN, CIDE, lipolysis, TAG synthesis, LD fusion

Introduction

As cytoplasmic organelles, lipid droplets (LDs) are composed of a neutral lipid core containing triacylglycerol (TAG) and/or cholesterol esters (CEs) coated with a phospholipid monolayer. Depending on the cell type, LD sizes range from <1μm in fibroblasts to >50 μm in primary adipocytes. These LDs, originally considered to be inert fat depots in cells, have now been shown to be highly dynamic and to be actively involved in cellular lipid accumulation, storage, and metabolism, directly contributing to cellular physiology. Since the discovery that perilipin (now named PLIN1) coats the surface of LDs, numerous proteins have been shown to associate with LDs and to change under different physiological conditions. These proteins serve as LD gatekeepers as well as messengers interacting with cytosolic proteins and other organelles controlling cellular lipid homeostasis. Here we briefly review some of the most recent findings published within the past year related to LD metabolism.

PLIN and CIDE proteins

There are many proteins reported to be associated with LDs. Two families of LD associated proteins that are of particular interest are the PLIN and CIDE protein families. While PLIN1 was the first protein identified to be associated with LDs, the PLIN family has expanded to include perilipin (PLIN1), ADRP (PLIN2), TIP47 (PLIN3), S3-14 (PLIN4) and OXPAT/LSDP5 (PLIN5). The various PLIN family members display different tissue distributions and have different preferences for association with TAG or CE. PLIN1a, PLIN2 and PLIN5 are more prominently found with cellular TAG loading, whereas PLIN1c and PLIN4 are enhanced by cellular cholesterol loading (1).

PLIN1 is highly expressed in white adipocytes and is actively involved in the regulation of lipolysis through changes of its phosphorylation status and its interaction with lipases (HSL) and lipase activators (CGI-58 for ATGL). Recent observations have shown that PLIN1 also interacts with and activates FSP27 (fat-specific protein of 27 kDa) and promotes the enlargement of LDs, leading to the formation of large LDs (2-3).

PLIN2 is ubiquitously expressed and interacts with LDs via both its N- and C-terminal domains. A recent study employing fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) showed that PLIN2 interacts with LD surface lipids such as phosphatidylcholine, cholesterol, sphingomyelin and stearic acid with a molecular distance approximately 44-57Å (4), indicating the interactions were occurring within the monolayer or at the monolayer surface. Overexpression of PLIN2 increases cellular phospholipid content, in addition to TAG and CE, suggesting PLIN2 might play a role in increasing LD membrane size to accommodate droplet expansion during lipid accumulation. PLIN2 has been reported to interact with ATGL in resting and post contraction muscle, with a 21% decrease in the interaction observed after contraction (5). Meanwhile PLIN2-associated LDs were preferentially depleted during moderate-intensity endurance-type exercise (6). Although the discovery of the presence of a truncated PLIN2 in the original PLIN2-deficient mice complicated the interpretation of the results, recent studies using antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) to silence PLIN2 confirmed that down-regulation of PLIN2 could be beneficial to combat fat accumulation in the liver (7) without cholesterol-induced toxicity to macrophages (8). Subsequent generation of conditional PLIN2 knockout mice showed that the absence of PLIN2 leads to resistance to high fat diet induced obesity through modulating food intake and locomotor activity (9). Similarly, silencing PLIN2 was shown to effectively attenuate the growth of tumor cells (10). In contrast to these potentially beneficial effects of reducing PLIN2 expression, higher PLIN2 levels have been suggested to be protective against lipotoxicity and insulin resistance in skeletal muscle (11). Most recently, a mis-sense polymorphism of PLIN2, Ser251Pro, was described in humans that leads to structural changes in the protein resulting in increased cellular lipid accumulation, increased number of small LDs and decreased lipolysis, along with a decrease in plasma triglyceride concentrations. This is the first example in which a polymorphism in PLIN2 has been shown to be a functional variant that is associated with plasma VLDL and triglyceride levels (12**). The impact of this polymorphism on human metabolic diseases remains to be explored.

PLIN3 is widely expressed in hepatocytes, enterocytes, and macrophages, as well as testes (13), and is increased in response to lipid loading. Structural analysis shows a spatial separation of the N- and C-terminal regions in monomeric human PLIN3 by its α/β domain, indicating the existence of two distinct “functional modules” and may explain the protein's unique dual functions: involvement in mannose 6-phosphate receptor recycling and in lipid biogenesis (14). ASO silencing studies show that PLIN3 affects hepatic lipid and glucose metabolism and may be a target for the treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver and related metabolic disorders (15).

Primarily expressed in oxidative tissues, PLIN5, the newest member of the family, was shown to localize to both LDs and mitochondria in muscle cells (16). PLIN5 has been shown to increase lipid accumulation, to enhance fatty acid (FA) oxidation through PPAR-α dependent pathways in the liver (17), to sequester FA from excessive oxidation and to protect the heart from oxidative stress (18). Previously reported cytosolic pools of PLIN5 are actually bound to structures of high-density LDs (19) and could represent nascent intracellular sites for lipid accumulation, and potential shifts to larger LDs upon lipid loading. These latter findings raise the possible involvement of PLIN5 during lipid trafficking from very small LDs to larger LDs. PLIN5 was also shown to be one of the few genes that were differentially expressed in brown (BAT) as compared to white adipose tissue (WAT). Interestingly, PLIN5 is significantly induced in WAT (gonadal and subcutaneous) following cold challenge as the WAT undergoes a “browning” process (20), again suggesting that PLIN5 might have an important role in BAT metabolism through its involvement in fatty acid oxidation.

CIDE (cell death-inducing DFF45-like effector) protein family (CIDEA, CIDEB and CIDEC, also known as FSP27), has been shown to reside on LDs and on the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), to be involved in LD fusion in adipocytes, VLDL lipidation and maturation in the liver. CIDEA was found to be a downstream target of FoxO1 and involved in the signaling for β-cell apoptosis induced by lipotoxicity (21). CIDEB was observed to be associated with the Golgi apparatus, with decreased mature VLDL found in the Golgi of CIDEB-/- liver, thus linking CIDEB with VLDL formation. Further studies showed that CIDEB and PLIN2 might exert opposing effects on VLDL lipidation in hepatocytes (22). FSP27 and CIDEA were shown to be enriched at LD-LD contact sites and the CIDE proteins promoted lipid transfer from smaller LDs to larger LDs (23). Recently, FSP27 was shown to interact with PLIN1 through its CIDE-N domain, leading to increased lipid transfer activity (2). Meanwhile, we have shown that FSP27 forms a physical interaction with nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 (NFAT5) at the LD surface and this interaction modulates the cellular response to osmotic stress by preventing NFAT5 from translocating to the nucleus and activating its down-stream targets (24**). In addition, Li's group has shown that both CIDEA and CIDEC are detected in the nucleus and that CIDEA can act as a transcriptional co-activator for C/EBPβ for controlling lipid secretion by modulating the expression of xanthine oxidoreductase in mammary epithelial cells (25).

In summary, LD associated proteins are vital constituents and actively involved in control of LD homeostasis.

Lipolysis and LD remodeling

G0/G1 switch gene-2 (G0S2) has recently been implicated in regulating lipolysis through ATGL. G0S2 was shown to inhibit activity while also anchoring ATGL to the LD, in contrast to CGI58 which activates ATGL (26). In poorly controlled type 2 diabetic patients, there is a significant decrease in mRNA of both PLIN1 and G0S2, which may contribute to elevated lipolysis and plasma free fatty acids in diabetes (27). Chronic stimulation of lipolysis induces the appearance of hundreds of micro LDs (<1 um in diameter). Initial studies showed that there were four proteins associated with microLDs, namely PLIN1a, PLIN2, PLIN4 and CGI58. Originally, it was suggested that these microLDs were formed from fragmentation of LDs upon lipolytic stimulation. Recently, several investigators have shown that these microLDs are actually formed from re-esterification of excess FA released during lipolysis and quickly become sites of active lipolysis by recruiting ATGL and HSL to the microLDs (28-30**). When lipolysis is terminated and cells return to lipogenesis and lipid accumulation, these microLDs can fuse and grow to macro-LDs through a mechanism involving microtubules.

LD and organellar interactions

LDs have been seen to interact with other organelles, such as the ER and mitochondria, by merging fluorescent images and by electron microscopy. The formation of LDs is thought to occur at the ER; however, little is known about the specifics of how these LDs form or how they expand. Recent work has looked into proteins that may be involved in these processes. A complex between resident ER protein FATP1 and LD protein DGAT2 was found that facilitated LD expansion, which was absent in catalytically dead mutants of FATP1 or DGAT2 (31**). This interaction may provide a physical and functional link between the ER and LDs. Among other ER proteins, members of the small GTPase family, Rab proteins, have been suggested to function in LD trafficking within the ER and LD formation. A systematic approach found that many Rabs were able to regulate the dynamics of LDs, with Rab32 affecting lipid storage through its effects on autophagy (32).

In addition to the role of the ER as the putative site for LD formation and expansion, ER stress has an effect on LD physiology. ER stress was found to promote hepatic lipogenic transactivators, LD promoting proteins, and enzymes involved in de novo lipogenesis, all of which have potentially important implications for the development of metabolic disease and diabetes (33). In addition to LD promotion, ER stress may result in an increase of lipolysis. In differentiated adipocytes, ER stress led to an activation of cAMP/PKA and ERK1/2, leading to phosphorylation of PLIN1 and phosphorylation and translocation of HSL (34**), resulting in an increased FA efflux and consequences such as lipotoxicity and insulin resistance.

The intimate relationship of the ER and LD formation involves the participation of many proteins and the sharing of many processes. Several proteins and complexes have recently been found to function in regulating neutral lipid storage by mechanisms involving ER-associated degradation (ERAD). A recent study has identified Aup1 in maintaining cholesterol homeostasis by interactions with ERAD and facilitating binding of gp78 and Trc8 to ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme (Ubc7) at the LD surface (35). Aup1, a highly conserved protein, was found to have a single domain that allowed for insertion into the ER as well as into LDs (36). Resident ER protein, UBX-domain containing protein (Ubx2), which selectively transports misfolded proteins for ERAD, was found to be crucial in LD maintenance, with deletion leading to a 50% decrease in intracellular TAG accumulation (37). Similarly, UBXD8 was found to bind to ATGL, thus contributing to LD turnover and maintaining LD size, as well as providing an important mechanism for regulating energy balance (38**).

In addition to the ER, LDs are known to interact with mitochondria for FA metabolism or steroidogenesis. Recent studies show that PLIN5 is highly expressed in muscle tissue, being expressed on both LDs and mitochondria, and involved in directing FA transfer from LDs to mitochondria for FA oxidation (39). Exercise was found to increase transcriptional coactivator PGC-1α, leading to an increase in genes involved in LD assembly and mobilization and mitochondrial remodeling, including PLIN5 (40). Retinyl esters, the stored form of retinal, accumulate within LDs and have been observed to utilize a complex between the ER, LDs, and mitochondria for synthesis and metabolism. Retinol dehydrogenase Rdh10 is localized to mitochondria and the mitochondria associated membrane (MAM) of the ER, but translocates to LDs during retinyl acyl ester biosynthesis, colocalizing with cellular retinol-binding protein (Crbp1) and lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT1), an ER protein (41). Activation of hepatic stellate cells into myofibroblasts leads to a replacement of retinyl esters by polyunsaturated FAs in LDs, suggesting a dynamic and regulated process at the LD (42).

LD synthesis and fusion

LDs are thought to grow by TAG synthesis in the ER or by the fusion of smaller LD proteins. While conventional dogma is that de novo TAG synthesis occurs in the ER, a recent study has challenged this paradigm. Wilfling et al. described the translocation of TAG synthetic enzymes GPAT4, AGPAT3, and DGAT2 to the LD (43**). These proteins were capable of catalyzing the synthesis of TAG at the LD, leading to an increase in LD size. This provides a mechanism, in addition to LD fusion, for the growth of LDs and a mechanism for LD growth in cells that lack components involved in LD fusion, such as FSP27 and PLIN1. It will be interesting to determine in cells that have FSP27 and PLIN1, such as adipocytes, the percentage of LD growth due to TAG synthesis at the LD or to LD fusion. In addition to TAG synthesis, LD growth can be observed by inhibition of lipolysis. PLIN5 was found to negatively regulate lipolysis and FA oxidation, contributing to TAG accumulation (44).

Smaller LDs can fuse to create larger LDs, which is mediated by FSP27 in adipocytes. Recent studies have found that a functional cooperation occurs between FSP27 and PLIN1, which was required for efficient LD growth and unilocular formation in adipocytes (2-3). In addition to FSP27, SNAP23, a member of the SNARE family, is important in the fusion of LDs. A recent study found that γ-synuclein might deliver SNAP23 to LDs and prevent lipolysis by sequestering ATGL (45).

The expansion, growth, and turnover of LDs constitute dynamic processes, requiring various signals that maintain or change the disposition of LDs. Several factors have been shown to influence the rate of LD accumulation and fusion. An increase in squalene levels, a hydrocarbon that is a biochemical precursor to cholesterol, was found not to have deleterious effect on lipid particles and may modulate membrane fluidity (46). Further studies have shown that an increase in squalene levels triggers an aggregation of LDs, which may preclude LD fusion (47). The role of squalene as a promoter of LD expansion deserves further analysis. Macroautophagy, an intracellular degradation system, may also play a role in maintaining LD size. Autophagy-related (Atg) protein was found to be present on autophagic membranes as well as LDs and depletion of Atg2 led to a clustering of enlarged LDs (48).

Conclusion

Many new insights into LD physiology have emerged recently. PLIN and CIDE family members have been found to participate in new ways in lipid homeostasis in addition to their involvement in fat storage. Studies have revealed that TAG synthetic enzymes localize directly on LDs, providing TAG for LD enlargement. LDs interact with ER and mitochondria to facilitate lipid transfer, LD expansion and metabolism. Improved microscopic techniques have allowed observations showing that LDs are in an active cycle of lipolysis and re-esterification to form microLDs, that TAG synthesis occurs in the ER and on LDs, and that TAG transfers between LDs during LD fusion. LDs continue to be shown to be involved in various aspects of cellular physiology and these studies highlight the functional significance of LDs in cellular lipid metabolism.

Figure 1.

Cartoon depicting LD metabolism. 1: LDs are coated by droplet-associated proteins; different PLINs have different preferences for TAG or CE LDs. 2: LDs undergo a cycle of lipolysis and re-esterification; LD size increases via fusion and de novo synthesis. 3: LDs interact with ER and mitochondria for synthesis, enlargement and metabolism.

Key points (as illustrated in Figure 1).

Different PLINs have different preferences for associating with TAG or CE, different tissue distributions, and each contributing to cellular lipid metabolism in its unique way. CIDE family members not only involved in LD expansion, they are also involved in the cellular response to stress and lipid secretion.

LDs are constantly in an active cycle of lipolysis and re-esterification (during which microLDs are formed), with TAG synthesis occurring in the ER and on LDs, and with TAG transferring between LDs during LD fusion and LD enlargement.

LDs interact with ER and mitochondria for lipid synthesis and metabolism. Multiple interacting protein pairs have been identified (FATP1 and DGAT2 for TAG synthesis; UBXD8 and ATGL for TAG turnover; PLIN5 facilitates the interaction of LDs and mitochondria for FA oxidation)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Department of Veterans Affairs (Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service) and by funding from the American Diabetes Association (7-12-BS-100).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Hsieh K, Lee Y, Londos C, Raaka B, Dalen K, Kimmel A. Perilipin family members preferentially sequester to either triacylglycerol-specific or cholesteryl-ester-specific intracellular lipid storage droplets. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:4067–4076. doi: 10.1242/jcs.104943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun Z, Gong J, Wu H, Xu W, Wu L, Xu D, Gao J, Wu J, Yang H, Yang M, Li P. Perilipin1 promotes unilocular lipid droplet formation through the activation of Fsp27 in adipocytes. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1594. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grahn T, Zhang Y, Lee M, Sommer A, Mostoslavsky G, Fried S, Greenberg A, Puri V. FSP27 and PLIN1 interaction promotes the formation of large lipid droplets in human adipocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432:296–301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.01.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4**.McIntosh A, Senthivinayagam S, Moon K, Gupta S, Lwande J, Murphy C, Storey S, Atshaves B. Direct interaction of Plin2 with lipids on the surface of lipid droplets: a live cell FRET analysis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C728–C774. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00448.2011. This study uses FRET analysis to determine the interaction of PLIN2 with LD surface lipids. This observation indicates the involvement of PLIN2 in expanding the LD membrane size to accommodate lipid accumulation. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Macpherson R, Ramos S, Vandenboom R, Roy B, Peters S. Skeletal muscle PLIN proteins, ATGL and CGI-58, interactions at rest and following stimulated contraction. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R644–650. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00418.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shepherd S, Cocks M, Tipton K, Ranasinghe A, Barker T, Burniston J, Wagenmakers A, Shaw C. Preferential utilization of perilipin 2-associated intramuscular triglycerides during 1 h of moderate-intensity endurance-type exercise. Exp Physiol. 2012;97:970–980. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2012.064592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Imai Y, Boyle S, Varela G, Caron E, Yin X, Dhir R, Dhir R, Graham M, Ahima R. Effects of perilipin 2 antisense oligonucleotide treatment on hepatic lipid metabolism and gene expression. Physiol Genomics. 2012;44:1125–1131. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00045.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Son SH, G Y, Chang BH, Paul A. Perilipin 2 (PLIN2)-deficiency does not increase cholesterol-induced toxicity in macrophages. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McManaman J, Bales E, Orlicky D, Jackman M, Maclean P, Cain S, Crunk A, Mansur A, Graham C, Bowman T, Greenberg A. Perilipin-2-null mice are protected against diet-induced obesity, adipose inflammation, and fatty liver disease. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:1346–1359. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M035063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qi W, Fitchev P, Cornwell M, Greenberg J, Cabe M, Weber C, Roy H, Crawford S, Savkovic S. FOXO3 growth inhibition of colonic cells is dependent on intraepithelial lipid droplet density. J Biol Chem. 2013 Apr 18; doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.470617. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosma M, Hesselink M, Sparks L, Timmers S, Ferraz M, Mattijssen F, van Beurden D, Schaart G, de Baets M, Verheyen F, Kersten S, Schrauwen P. Perilipin 2 improves insulin sensitivity in skeletal muscle despite elevated intramuscular lipid levels. Diabetes. 2012;61:2679–2690. doi: 10.2337/db11-1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12**.Magné J, Aminoff A, Sundelin J, Mannila M, Gustafsson P, Hultenby K, Wernerson A, Bauer G, Listenberger L, Neville M, Karpe F, Borén J, Ehrenborg E. The minor allele of the missense polymorphism Ser251Pro in perilipin 2 (PLIN2) disrupts an α-helix, affects lipolysis, and is associated with reduced plasma triglyceride concentration in humans. FASEB J. 2013 Apr 19; doi: 10.1096/fj.13-228759. [Epub ahead of print] This study describes the first polymorphism of PLIN2 to be a functional variant that is associated with plasma VLDL and TG levels, although the impact of this polymorphism on human metabolic diseases remains to be explored. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu M, Qi L, Zeng Y, Yang Y, Bi Y, Shi X, Zhu H, Zhou Z, Sha J. Transient scrotal hyperthermia induces lipid droplet accumulation and reveals a different ADFP expression pattern between the testes and liver in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e45694. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hynson R, Jeffries C, Trewhella J, Cocklin S. Solution structure studies of monomeric human TIP47/perilipin-3 reveal a highly extended conformation. Proteins. 2012;80:2046–2055. doi: 10.1002/prot.24095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carr R, Patel R, Rao V, Dhir R, Graham M, Crooke R, Ahima R. Reduction of TIP47 improves hepatic steatosis and glucose homeostasis in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2012;302:R996–1003. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00177.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Sreenevasan U, Hu H, Saladino A, Polster B, Lund L, Gong D, Stanley W, Sztalryd C. Perilipin 5, a lipid droplet-associated protein, provides physical and metabolic linkage to mitochondria. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:2159–2168. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M017939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Song Y, Zhang L, Gu Y, Li F, Pan S, Jiang L, Liu F, Ye J, Li Q. LSDP5 enhances triglyceride storage in hepatocytes by influencing lipolysis and fatty acid β-oxidation of lipid droplets. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kuramoto K, Okamura T, Yamaguchi T, Nakamura T, Wakabayashi S, Morinaga H, Nomura M, Yanase T, Otsu K, Usuda N, Matsumura S, Inoue K, Fushiki T, Kojima Y, Hashimoto T, Sakai F, Hirose F, Osumi T. Perilipin 5, a lipid droplet-binding protein, protects heart from oxidative burden by sequestering fatty acid from excessive oxidation. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:23852–23863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.328708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartholomew S, Bell E, Summerfield T, Newman L, Miller E, Patterson B, Niday Z, Ackerman Wt, Tansey J. Distinct cellular pools of perilipin 5 point to roles in lipid trafficking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:268–278. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2011.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barneda D, Frontini A, Cinti S, Christian M. Dynamic changes in lipid droplet-associated proteins in the “browning” of white adipose tissues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1831:924–933. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2013.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omae N, Ito M, Hase S, Nagasawa M, Ishiyama J, Ide T, Murakami K. Suppression of FoxO1/cell death-inducing DNA fragmentation factor α-like effector A (Cidea) axis protects mouse β-cells against palmitic acid-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2012;348:297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li X, Ye J, Zhou L, Gu W, Fisher E, Li P. Opposing roles of cell death-inducing DFF45-like effector B and perilipin 2 in controlling hepatic VLDL lipidation. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:1877–1889. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M026591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong J, Sun Z, Wu L, Xu W, Schieber N, Xu D, Shui G, Yang H, Parton R, Li P. Fsp27 promotes lipid droplet growth by lipid exchange and transfer at lipid droplet contact sites. J Cell Biol. 2011;195:953–963. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201104142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24**.Ueno M, Shen W, Patel S, Greenberg A, Azhar S, Kraemer F. Fat-specific protein 27 modulates nuclear factor of activated T cells 5 and the cellular response to stress. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:734–743. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M033365. This study describes the involvement of LD protein FSP27 in mediating cellular response to osmotic stress. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang W, Lv N, Zhang S, Shui G, Qian H, Zhang J, Chen Y, Ye J, Xie Y, Shen Y, Wenk M, Li P. Cidea is an essential transcriptional coactivator regulating mammary gland secretion of milk lipids. Nat Med. 2012;18:235–243. doi: 10.1038/nm.2614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schweiger M, Paar M, Eder C, Brandis J, Moser E, Gorkiewicz G, Grond S, Radner F, Cerk I, Cornaciu I, Oberer M, Kersten S, Zechner R, Zimmermann R, Lass A. G0/G1 switch gene-2 regulates human adipocyte lipolysis by affecting activity and localization of adipose triglyceride lipase. J Lipid Res. 2012;53:2307–2317. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M027409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nielsen T, Kampmann U, Nielsen R, Jessen N, Ørskov L, Pedersen S, Jørgensen J, Lund S, Møller N. Reduced mRNA and protein expression of perilipin A and G0/G1 switch gene 2 (G0S2) in human adipose tissue in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1348–E1352. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ariotti N, Murphy S, Hamilton NA, Wu L, Green K, Schieber NL, Li P, Martin S, Parton RG. Postlipolytic insulin-dependent remodeling of micro lipid droplets in adipocytes. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:1826–1837. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-10-0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29**.Paar M, Jüngst C, Steiner N, Magnes C, Sinner F, Kolb D, Lass A, Zimmermann R, Zumbusch A, Kohlwein S, Wolinski H. Remodeling of lipid droplets during lipolysis and growth in adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2012;287 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316794. This study uses time lapse fluorescence microscopy and coherent anti-Stokes Raman scattering microscopy to show that lipolysis and lipogenesis occur in parallel in the cell. This observation challenges the original theory about LD fragmentation, and shows that micro LDs are synthesized de novo through re-esterification. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hashimoto T, Segawa H, Okuno M, Kano H, Hamaguchi H, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y, Hasui S, Yamaguchi T, Hirose F, Osumi T. Active involvement of micro-lipid droplets and lipid-droplet-associated proteins in hormone-stimulated lipolysis in adipocytes. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:6127–6136. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Xu N, Zhang SO, Cole RA, McKinney SA, Guo F, Haas JT, Bobba S, Farese RV, Jr, Mak HY. The FATP1-DGAT2 complex facilitates lipid droplet expansion at the ER-lipid droplet interface. J Cell Biol. 2012;198:895–911. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201201139. This study describes the interaction between FATP1 and DGAT2. This observation provides a mechanism by which LDs are recruited to the endoplasmic reticulum, an important insight on a fundamental aspect of lipid droplet expansion, an area not well understood. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C, Liu Z, Huang X. Rab32 is important for autophagy and lipid storage in Drosophila. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee JS, Mendez R, Heng HH, Yang ZQ, Zhang K. Pharmacological ER stress promotes hepatic lipogenesis and lipid droplet formation. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4:102–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34**.Deng J, Liu S, Zou L, Xu C, Geng B, Xu G. Lipolysis response to endoplasmic reticulum stress in adipose cells. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:6240–6249. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.299115. This study describes a novel mechanism by which endoplasmic reticulum stress can lead to lipolysis. This observation may have important consequences in the development of lipotoxicity, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jo Y, Hartman IZ, DeBose-Boyd RA. Ancient ubiquitous protein-1 mediates sterol-induced ubiquitination of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA reductase in lipid droplet-associated endoplasmic reticulum membranes. Mol Biol Cell. 2013;24:169–183. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E12-07-0564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stevanovic A, Thiele C. Monotopic topology is required for lipid droplet targeting of ancient ubiquitous protein 1. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:503–513. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M033852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang CW, Lee SC. The ubiquitin-like (UBX)-domain-containing protein Ubx2/Ubxd8 regulates lipid droplet homeostasis. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2930–2939. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38**.Olzmann JA, Richter CM, Kopito RR. Spatial regulation of UBXD8 and p97/VCP controls ATGL-mediated lipid droplet turnover. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1345–1350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213738110. This study describes the translocation of Ubxd8 from the ER to the LD. This observation is crucial for the maintenance of TAG homeostasis, with deletion of Ubxd8 leading to a decrease in TAG levels. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bosma M, Minnaard R, Sparks LM, Schaart G, Losen M, de Baets MH, Duimel H, Kersten S, Bickel PE, Schrauwen P, Hesselink MK. The lipid droplet coat protein perilipin 5 also localizes to muscle mitochondria. Histochem Cell Biol. 2012;137:205–216. doi: 10.1007/s00418-011-0888-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koves TR, Sparks LM, Kovalik JP, Mosedale M, Arumugam R, DeBalsi KL, Everingham K, Thorne L, Phielix E, Meex RC, Kien CL, Hesselink MK, Schrauwen P, Muoio DM. PPARgamma coactivator-1alpha contributes to exercise-induced regulation of intramuscular lipid droplet programming in mice and humans. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:522–534. doi: 10.1194/jlr.P028910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang W, Napoli JL. The retinol dehydrogenase Rdh10 localizes to lipid droplets during acyl ester biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:589–597. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.402883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Testerink N, Ajat M, Houweling M, Brouwers JF, Pully VV, van Manen HJ, Otto C, Helms JB, Vaandrager AB. Replacement of retinyl esters by polyunsaturated triacylglycerol species in lipid droplets of hepatic stellate cells during activation. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43**.Wilfling F, Wang H, Haas JT, Krahmer N, Gould TJ, Uchida A, Cheng JX, Graham M, Christiano R, Frohlich F, Liu X, Buhman KK, Coleman RA, Bewersdorf J, Farese RV, Jr, Walther TC. Triacylglycerol synthesis enzymes mediate lipid droplet growth by relocalizing from the ER to lipid droplets. Dev Cell. 2013;24:384–399. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.01.013. This study describes the translocation of TAG synthetic enzymes to the LD. This observation is important because it provides evidence of TAG synthesis at the LD, which may be an important mechanism for LD expansion. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li H, Song Y, Zhang LJ, Gu Y, Li FF, Pan SY, Jiang LN, Liu F, Ye J, Li Q. LSDP5 enhances triglyceride storage in hepatocytes by influencing lipolysis and fatty acid beta-oxidation of lipid droplets. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36712. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Millership S, Ninkina N, Guschina IA, Norton J, Brambilla R, Oort PJ, Adams SH, Dennis RJ, Voshol PJ, Rochford JJ, Buchman VL. Increased lipolysis and altered lipid homeostasis protect gamma-synuclein-null mutant mice from diet-induced obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:20943–20948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210022110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spanova M, Zweytick D, Lohner K, Klug L, Leitner E, Hermetter A, Daum G. Influence of squalene on lipid particle/droplet and membrane organization in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:647–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2012.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ta MT, Kapterian TS, Fei W, Du X, Brown AJ, Dawes IW, Yang H. Accumulation of squalene is associated with the clustering of lipid droplets. FEBS J. 2012;279:4231–4244. doi: 10.1111/febs.12015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Velikkakath AK, Nishimura T, Oita E, Ishihara N, Mizushima N. Mammalian Atg2 proteins are essential for autophagosome formation and important for regulation of size and distribution of lipid droplets. Mol Biol Cell. 2012;23:896–909. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-09-0785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]