Abstract

Aim:

To investigate the mechanism of the bone-forming effects of intermittent parathyroid hormone (PTH) administration and to search for novel molecules of bone anabolism via the PTH signaling pathway.

Methods:

Primary cultures of rat osteoblasts (ROBs) were divided into an intermittent PTH-treated group (Itm) and a control group (Ctr). Imitating the pharmacokinetics of intermittent PTH administration in vivo, the ROBs in the Itm group were exposed to PTH for 6 h in a 24-h incubation cycle, and the ROBs in the Ctr group were exposed to vehicle for the entire incubation cycle. The cells were collected at 6 h and 24 h of the final cycle, and the proteins in the Itm and Ctr groups were analyzed by two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE) coupled with peptide mass fingerprinting and matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) to detect proteins that were differentially expressed. The proteins with the most significant changes in vitro were validated by immunohistochemistry (IHC) in a rat model.

Results:

The proteomics analysis indicated that a total of 26 proteins were up- or down-regulated in the Itm group compared with the Ctr group at 6 h and 24 h; among these, 15 proteins were successfully identified. These proteins mainly belong to the cytoskeleton and molecular chaperone protein families, and most of these have anti-apoptotic effects in various cells. Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor α (RhoGDIα) and vimentin were the most significantly changed proteins. Further studies by IHC showed that the expression of RhoGDIα in ROBs was significantly higher in PTH-treated sham-operated rats than in vehicle-treated sham-operated rats, but the difference was not significant between PTH-treated and vehicle-treated OVX rats. Vimentin expression was not changed in either PTH-treated sham-operated rats or PTH-treated OVX rats.

Conclusion:

Our research suggests that intermittent PTH treatment induces changes in expression of many proteins in ROBs in vitro, and it results in RhoGDIα up-regulation in ROBs both in vitro and in vivo when estrogen is present. This up-regulation of RhoGDIα may be one of the mechanisms underlying the synergistic bone-forming effect of PTH and estrogen.

Keywords: parathyroid hormone, Rho GDP-dissociation inhibitor α, osteoblast, immunohistochemistry, proteomics

Introduction

The treatment of osteoporosis at the present time mainly depends on antiresorptive agents such as bisphosphonates (BPs) and calcitonin, as well as estrogen. However, these drugs only have moderate effects on increasing bone mass. There is no satisfactory drug that considerably increases bone mass for severe osteoporosis. PTH is a major osteotropic factor that plays a critical role in calcium homeostasis and in regulating bone turnover. PTH possesses bi-directional actions, ie, it is bone-catabolic and bone-anabolic. Many experiments have shown that continuous exposure to PTH decreases bone mass by stimulating a net increase in bone resorption, whereas intermittent administration of PTH can increase bone mass1, 2, 3, 4. The mechanism involved in osteogenesis of intermittent PTH administration is not clear. Osteoblasts play a central role in PTH-mediated osteogenesis in vivo, and even the effect of PTH on osteoclasts is mediated by osteoblasts; therefore, research designed to determine the effects of PTH on osteoblasts is an important approach for studying the anabolic mechanisms of PTH and for searching for new therapeutic strategies to the treatment of osteoporosis.

A previous DNA microarray analysis reported changes in the gene expression profile of an osteoblastic cell line (UMR 106-01) when the cells were treated with PTH. A total of 125 known genes and 30 unknown expressed sequence tags (ESTs) were found to have at least a twofold change in expression after PTH treatment for 4, 12, and 24 h5; however, quantitative mRNA data does not necessarily correlate well with protein expression levels6. A two-dimensional electrophoresis (2-DE)-based proteomics approach provides a powerful tool to simultaneously analyze changes in protein levels in tissues and cells7, and it should help us uncover the anabolic mechanisms of PTH. Recently, using comparative proteomics, some researchers identified candidate biomarkers to distinguish osteosarcoma cells from normal osteoblastic cells. In our study, proteomics technologies were applied to identify PTH-regulated proteins in osteoblasts with intermittent PTH treatment (this cell model is anabolic for bone as documented previously in our laboratory8). We found tens of proteins that were increased or decreased in osteoblasts intermittently exposed to PTH; among those that changed, the expression levels of RhoGDIα, GRP78 and vimentin were up-regulated to the greatest extent (around 10-fold). Furthermore, RhoGDIα and vimentin content were also increased in the secreted protein spectrum (also called “secretome”) of the same cell model9. To validate the in vitro results of RhoGDIα and vimentin, recombinant human PTH was intermittently (once daily) injected into rats, and immunohistochemistry was used to observe the in vivo changes of RhoGDIα and vimentin in rat bone osteoblasts.

Materials and methods

Cell model of intermittent PTH treatment

Primary cultures of ROBs were obtained using an enzyme digestion method described previously10. Cells were maintained in DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone, Logan, USA). PTH (1-34) (P3796, Sigma, St Louis, USA ) stock solution (5 μg/mL) was prepared by dissolving PTH in a 20 mL 0.1% HAc solution containing 0.1% BSA. The cultured ROBs were divided into a PTH-treated group (Itm) and a control group (Ctr). Itm groups were cultured in PTH-containing (50 ng/mL) medium for the first 6 h and in the vehicle medium (containing 0.1% HAc) for the subsequent 18 h in a 24-h incubation cycle. The control groups were cultured in vehicle medium all the time. There were three 24-h cycles during the study. In the third cycle, the cells were collected at 6 h and 24 h.

Protein extraction, 2-DE and protein identification

Osteoblasts were lysed in lysis buffer containing 7 mol/L urea, 2 mol/L thiourea, 4% CHAPS, 65 mmol/L DTT, 40 mmol/L Tris and 2% (pH 3-10) IPG (immobilized PH gradient) buffer (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). Samples were then kept on ice and sonicated in 5 cycles each consisting of a 3-s sonication followed by a 30-s break and, finally, held for 1 h at room temperature with occasional vortex mixing. After centrifugation at 40 000×g for 1 h at 4 °C, protein concentrations of the supernatant were measured by the Bradford assay11. Proteins (120 μg) were applied to IPG (immobilized pH gradient) strips (24 cm, PH4-7, NL, Amersham Biosciences) using a passive rehydration method. After 12 h of rehydration, isoelectric focusing (IEF) was performed as follows: 500 V for 1 h, 1000 V for 1 h, and then at 8000 V up to total 80000 V·h. Once IEF was completed, the strips were equilibrated in equilibration buffer (0.375 mol/L Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 6 mol/L urea, 20% glycerol, 2% SDS, and 1% DTT) for 15 min, followed by the same buffer containing 2.5% iodoacetamide instead of DTT for another 15 min. The second dimension was performed using an Ettan-Dalt II system (Amersham Pharmacia, Uppsala, Sweden) with 12.5% SDS-PAGE at 2 W/gel for 1 h, 5 W/gel for 30 min and 15 W/gel for 10 h, until the bromophenol blue front had reached the bottom of the gel. Samples were run for three independent cell culture experiments. Proteins were visualized by silver staining of the gels. The images were scanned with ImageScanner (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden), and image analysis was carried out using ImageMaster 2D Elite (Version 2.0) software (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The differential expression protein spots between the two groups were selected and analyzed by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI/TOF MS). Peptide masses generated from the MALDI/TOF MS analysis were used for protein identification by peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF). The data obtained from PMF were retrieved using the search algorithm MASCOT against the Expasy protein sequence database. The proteins were identified using a number of criteria, including pI, MW, sequence coverage, and score.

Animal models

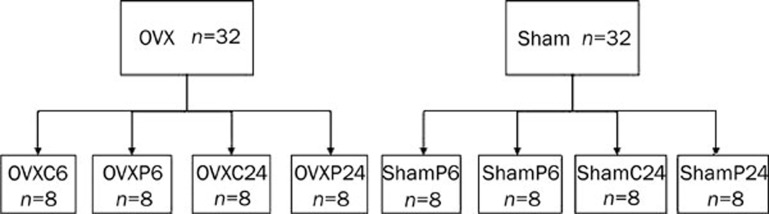

Four-week-old virgin female specific pathogen-free (SPF) Sprague Dawley rats weighing 100±10 g (ShangHai SLAC Laboratory Animal Co Ltd SCXK 2003-0003) were housed at a SPF animal facility at Laboratory Animals of Nanjing Medical University and had ad libitum access to water and commercial standard food. After 1 week of acclimatization to their new environment, the rats were either ovariectomized (OVX) or sham-operated. OVX or sham-operated rats were randomly divided into 4 groups (Figure 1). Three weeks following surgery, animals were injected subcutaneously with rhPTH (1–34) (Lilly, USA) 40 μg·kg−1·d−1 or with vehicle (0.01% HAc) for 7 days. At 6 h and 24 h post-injection of PTH or vehicle on the last day, each group of rats was sacrificed. Tibias cleaned of soft tissue were obtained and fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde. The bones were then decalcified in 10% EDTA at pH 7.2.

Figure 1.

A total of 64 female SD rats were separated into eight groups. On average, each group consisted of 8 rats. OVXC (shamc) represents OVX (sham-operated) injected with vehicle (0.01% HAc) and OVXP (ShamP) means OVX (sham-operated) injected with rhPTH (1–34). ShamC6 (C24) means the sham-operated rats will be sacrificed at 6 h or 24 h post-injection of HAc on the last day. ShamP6 (P24) means the sham-operated rats will be sacrificed at 6 h or 24 h post-injection of PTH on the last day. OVXC6 (C24) and OVXP6 (P24) represent the same meaning and the difference is OVX rats was used to replace sham-operated rats.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemical analysis was performed by the EnVision+TM system (Dako Cytomation, CA, USA) to determine the protein expression of RhoGDIα and vimentin in osteoblasts of rat tibia. The procedure can be described as follows. Consecutive paraffin wax embedded tissue sections (5 μm) were de-waxed and rehydrated through graded alcohol rinses. Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating the slides in 0.1% CaCl2 containing 0.1% trypsin for 50 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating the slides in 6% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min, followed by washing in PBS containing 0.2% Tween 20 (PBST) three times; the sections were incubated at 4°C overnight with the normal goat serum and were rinsed with PBST and incubated at 4 °C overnight with the primary mouse monoclonal antibody against RhoGDIα (diluted 1:50, sc-13120, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA), mouse monoclonal antibody against vimentin (diluted 1:25, sc-32322 , Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA) individually, followed by washing with PBST. For the visualization of RhoGDIα and vimentin, Envision+/HRP was applied to the sections for 2 h at room temperature, and diaminobenzidine hydrochloride (DAB) was used. These sections were counterstained with Meyer's hematoxylin. In order to prove the specificity of the immunoreaction, a negative control was carried out by omitting the primary antibody and using PBS instead. In order to exclude non-specific binding of the antibodies to unrelated antigens, a pre-adsorption control was run for RhoGDIα by using an antibody/peptide mixture containing a twofold excess of blocking peptide (sc-13120p, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA). For RhoGDIα and vimentin, cytoplasmic staining was considered to be positive expression. Six representative sections were chosen in each group containing 8 rats. In each section, the number of positive and negative osteoblasts was counted in five high-power fields (×400) near the growth plate of the tibia using Image-ProPlus 5.0 (Media cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, USA). The proportion of positively stained cells (positive osteoblasts/total osteoblasts) was counted in each field, and then the average proportion of positive osteoblasts was counted in each section. Finally, the average proportion of positive osteoblasts for each group was compared.

Statistical analysis

The average proportion of positive osteoblasts was presented as mean±SD. Comparisons between groups of data were made using an unpaired t-test (GraphPad InStat for Windows Version 3.0; GraphPad Software Inc). P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

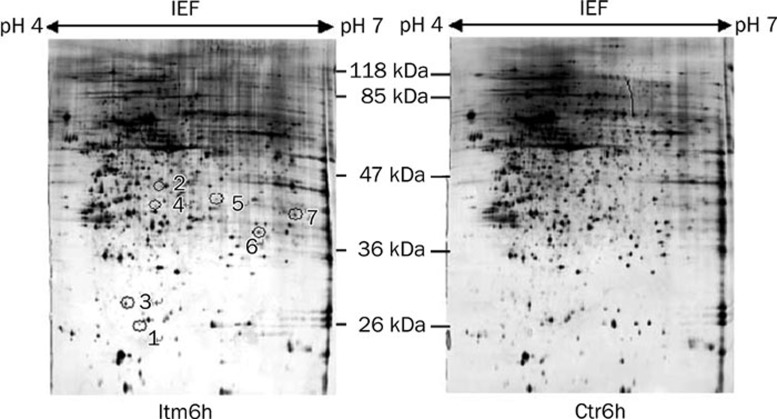

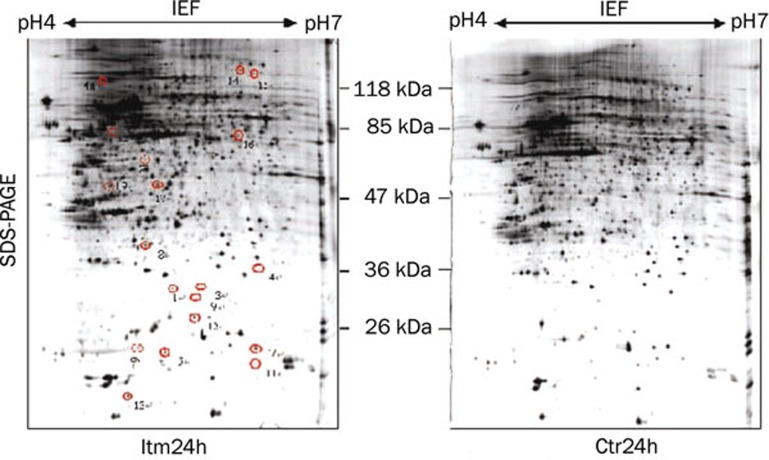

Results of 2-DE

To ensure repeatability, the experiments were repeated three times. Only those spots that changed consistently and significantly (more than twofold) were defined as differentially expressed proteins. Cropped images from 2-D gels demonstrating the differential expression of selected proteins were shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. A total of 26 spots were identified as differentially expressed, and of those, 7 proteins were down-regulated in the Itm group at 6 h (Figure 2) whereas 14 proteins were up-regulated and 5 proteins were down-regulated in the Itm group at 24 h (Figure 3) compared with the control group.

Figure 2.

Silver stained 2-DE maps of proteins that were differentially expressed in Itm6h and Ctr6h groups. Spots of proteins that were differentially expressed are labeled with numbers. Spots 1−7 represent the down-regulated proteins in the Itm6h group. Only down-regulated proteins can be seen at Itm6h.

Figure 3.

Silver stained 2-DE maps of proteins that were differentially expressed in the Itm24h and Ctr24h groups. Spots of proteins that were differentially expressed are labeled with numbers. Spots 1−13 and 19 represent the up-regulated proteins, and spots 14−18 represent the down-regulated proteins in the Itm24h group compared with the Ctr24h group.

Protein identification

Differentially expressed protein spots (spots 1−5 in Itm6h and spots 1−10, 12, 14−15, 19 in Itm24h) were selected and subjected to mass spectrometry analysis. We finally identified 4 down-regulated proteins (Table 1) and 11 up-regulated proteins (Table 2). The properties of 2 proteins (spots 5 and 12) are unknown in the protein database. Two other proteins (Spots 14 and 15), which were down-regulated in Itm24h, were not successfully detected because of the low content of protein.

Table 1. Identification of differentially expressed proteins (6 h).

| Spot No | Accession No | Sequence coverage | Score | Down-Regulated folds | Theoretical PI/molecular weight (kDa) | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Q5XI32 | 27% | 104 | 2.54↓ | 5.69/30.9 | F-actin capping protein beta subunit |

| 2 | Q68FT7 | 7% | 55 | 2.09↓ | 6.63/66.3 | Phenylalanine-tRN Asynthetase-like subunit |

| 3 | Q499R7 | 17% | 57 | 2.20↓ | 6.42/38.2 | Pp protein |

| 4 | Q7TNI4 | 23% | 52 | 2.18↓ | 9.19/27.1 | IL-22R-alpha-2 |

| 5 | Q5I0DI | 25% | 84 | 4.37↓ | 5.11/33.5 | Hypothetical |

Table 2. Identification of differentially expressed proteins (24 h).

| Spot No | Accession No | Sequence coverage | Score | Up-Regulated folds | Theoretical PI/molecular weight (kDa) | Protein name |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | P60711 | 20% | 98 | 2.02↑ | 5.29/42.0 | Beta-actin |

| 2 | P310001 | 71% | 409 | 10.12↑ | 5.06/53.6 | Vimentin |

| 3 | P06761 | 13% | 60 | 11.23↑ | 5.07/72.5 | 78 kDa glucose-regulated protein precursor (GRP 78) |

| 4 | Q4QRA3 | 13% | 59 | 2.77↑ | 8.57/24.5 | GrpE-like 1 |

| 5 | P97576 | 14% | 53 | 2.09↑ | 8.57/24.5 | GrpE protein homolog 1 |

| 6 | P04785 | 8% | 55 | 4.70↑ | 4.82/57.3 | Protein disulfide-isomerase precursor (PDI) |

| 7 | P52555 | 36% | 94 | 3.27↑ | 6.23/28.6 | Endoplasmic reticuhum protein precursor (ERp29) |

| 8 | Q5XI73 | 37% | 93 | 9.89↑ | 5.12/23.5 | Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) alpha |

| 9 | O88767 | 46% | 146 | 2.77↑ | 6.32/20.2 | Protein DJ-1 |

| 10 | Q5RKH | 18% | 89 | 2.34↑ | 5.24/42.8 | Galactokinase 1 |

| 12 | Q5I0DI | 15% | 66 | 2.37↑ | 5.11/33.5 | Hypothetical |

| 19 | PI5473 | 28% | 50 | 2.00↑ | 8.68/32.7 | Insulin-like growth factor binding protein 3 precursor (IGFBP-3) |

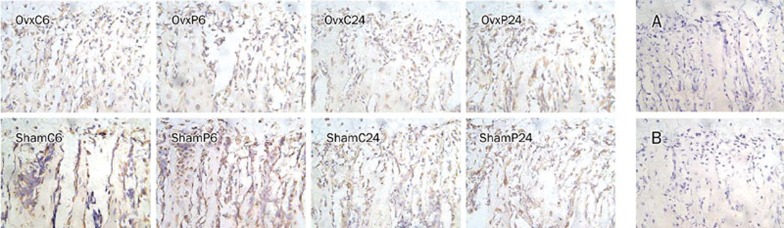

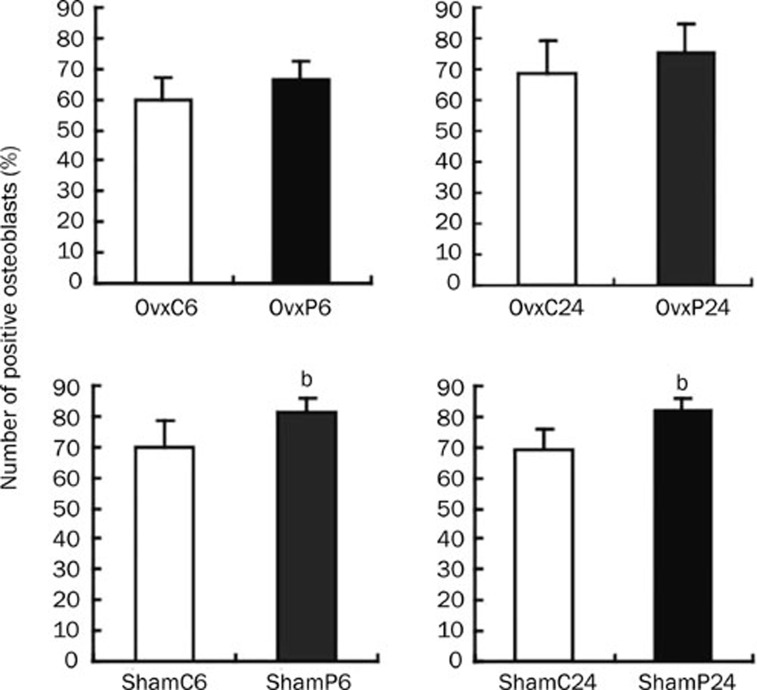

IHC analysis of RhoGDIα

The expression of RhoGDIα and vimentin in ROBs increased almost 10-fold in the Itm24h group compared with the control group in vitro. IHC was performed to confirm the results obtained by proteomics technologies. Representative immunohistological staining of RhoGDIα in rat tibia was shown in Figure 4. The results of comparing each group's average proportion of positive osteoblasts are described in Figure 5. In the sham groups, the expression of RhoGDIα in PTH-treated rats was higher than in controls (ShamP6 vs ShamC6, 81.18%±4.7% vs 69.93%±8.52%, P=0.018; ShamP24 vs ShamC24, 82.09%±3.94% vs 69.44%±6.46%, P=0.002). In the OVX groups, there were no differences between PTH-treated rats and controls (OVXP6 vs OVXC6, 66.55%±6.27% vs 59.46%±7.72%, P=0.111; OVXP24 vs OVXC24, 75.28%±9.27% vs 68.95±10.07%, P=0.284). No positive staining was observed in the negative control group (Figure 4A) and the pre-adsorption control group (Figure 4B). As to vimentin, we did not see any differences between the PTH-treated and vehicle-treated Sham/OVX rats (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Representative immunohistological staining of RhoGDIα under the growth plate of the rat tibia is shown. Positive osteoblasts were observed in OVX or sham-operated rats which were either vehicle-treated or PTH-treated. Image analysis software (Image-ProPlus 5.0) was used to count the proportion of positive osteoblasts in each field. A total of five fields were selected in each slide, and these pictures represented only one field, respectively. (A) A negative control was performed without the addition of the primary antibody, and it represents background staining. (B) A pre-adsorption control performed using an antibody/peptide mixture was also negative for RhoGDIα. Magnification ×400.

Figure 5.

The percentage of positive osteoblasts in each group. n=6 per group. Data were presented as mean±SD. The data for sham groups (ShamP6 vs ShamC6; ShamP24 vs ShamC24) and OVX groups (OvxP6 vs OvxC6; OvxP24 vs OvxC24) were compared. bP<0.05 compared with each control.

Discussion

This study used a proteomics approach to identify PTH-regulated proteins within ROBs intermittently treated with PTH. This model of intermittent PTH stimulation of ROBs imitates the pharmacokinetics of PTH in vivo, and in this model, PTH can directly stimulate the osteogenesis of ROBs as it does in vivo; therefore, this model is more reasonable than previously used cell models of continuous PTH stimulation, which suppressed the osteogenesis of ROBs12, 13. Using 2-DE on cell lysates, we successfully identified 4 down-regulated proteins in the Itm6h group and 11 up-regulated proteins in the Itm24h group compared with controls. Among them, F-actin capping protein, beta-actin, and vimentin belong to the family of cellular structural proteins that play an important role in maintaining cell morphology, in stabilizing the cell membrane, and in regulating cell apoptosis14, 15. ERP29, PDI-precursor, GRP78 precursor, GrpE (GrpE-like 1 and GrpE protein homolog 1), and RhoGDIα were up-regulated in the Itm24h group and belong to the family of molecular chaperone proteins, which plays a key role in the processes of protein biosynthesis, signal transduction, immunoregulation, and apoptosis. IGFBP-3, a member of the IGFBP family, promotes bone metabolism when it binds to IGF-116, but over-expression of IGFBP-3 can inhibit osteogenesis17. As for IL-22R-alpha-2, phenylalanine-tRNA synthetase-like subunit, Pp protein, and Galactokinase 1, we did not find some significant references for these proteins related to bone metabolism. The roles played by these molecules in PTH-induced osteogenesis are still unknown, and their fluctuations within osteoblasts represent novel findings that deserve further investigation. In this study, there is no succession of categories of differentially expressed proteins from 6 h to 24 h. The reason may be as follows: (1) accretion rate of cellular proteins is fast; (2) the processes stimulated by PTH not only occur during incubation with PTH, but also occur for some time after the PTH has been removed, and the delayed effect of PTH after removal of PTH may be more important for the anabolic effect because continuous exposure to PTH inhibits the function of ROBs. This view was also supported by our previous research8. We temporarily called this effect of PTH the “delayed effect of trigger”.

The intermittent treatment of PTH can result in a dramatic increase of RhoGDIα and vimentin in ROBs in vitro, but the overexpression of vimentin was not observed in ROBs in vivo; therefore, the in vitro result was inconsistent with the in vivo result. However, as for RhoGDIα, we obtained consistent results in vitro and in vivo, ie, intermittent stimulation of PTH promoted overexpression of RhoGDIα, not only in ROBs in vitro, but also in sham-operated ROBs in vivo. It is important to note that intermittent PTH had no stimulation effect on the expression of RhoGDIα in ovariectomized ROBs. This result suggests that intermittent PTH stimulates overexpression of RhoGDIα only in the presence of estrogen (enough estrogen existed both in the medium of ROBs with fetal bovine serum and sham-operated rats), and that RhoGDIα may not be involved in the treatment of osteoporosis in OVX rats using PTH.

RhoGDIα, a cytoplasmic protein originally identified as a negative regulator of the Rho family of GTPases, is ubiquitously expressed in cells and tissues18, 19. The Rho family of GTPases, which include Rac1, RhoA, and Cdc42, are well known for their ability to regulate actin cytoskeleton remodeling, thereby promoting changes in cell morphology, adhesion, and motility20. RhoGDIα, by binding to Rho GTPases, inhibits their activation. Transgenic mice lacking RhoGDIα had impaired development of the kidneys and reproductive organs21. Moreover, RhoGDIα also plays a significant role in the development of human cancers22, 23. What is the effect of RhoGDIα on bone metabolism? RhoGDIα can increase estrogen receptor (ER) transactivation by antagonizing Rho function24, while ER is crucial for bone mass maintenance in both human25 and mouse26, 27. The biological effects of estrogen are mediated by ER, and ERα is required for estrogen to stimulate cancellous bone formation in long bones of male and female mice28. Therefore, the elevation of RhoGDIα is helpful for bone synthesis, and our results can at least partly explain why combined therapy with PTH and estrogen in ovariectomized rats29 and in osteoporotic patients30 could be more efficacious at increasing bone mass than PTH or estrogen alone. Moreover, RhoGDIα is an antiapoptotic molecule31, and it may play an important role in inhibiting the apoptosis of osteoblasts. Hence, RhoGDIα may be involved in PTH-induced osteogenesis by increasing ER transactivation and its antiapoptotic action.

In summary, this paper is the first report that intermittent administration of PTH significantly increases the expression level of RhoGDIα in ROBs in vitro and in vivo if estrogen is present. This result supports the combination therapy of PTH and estrogen in the treatment of osteoporosis. In addition to RhoGDIα, other differentially expressed proteins identified in this study also represent novel findings that deserve further analysis. With more in-depth research on these proteins, we will obtain some new targets to treat metabolic bone diseases such as osteoporosis.

Author contribution

Ke-qin ZHANG designed the research; Zu-feng SUN and Hui JIANG performed the research; Zu-feng SUN analyzed the data and wrote the paper. Zheng-qin YE, Bing JIA,and Xiao-le ZHANG helped us complete animal experiment.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by the Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Scholars of the Ministry of Education of China and of the Ministry of Personnel of China. We thank the Central Laboratory of Nanjing Medical University for technical support for the MS/MS analysis.

References

- Misof BM, Roschger P, Cosman F, Kurland ES, Tesch W, Messmer P, et al. Effects of intermittent parathyroid hormone administration on bone mineralization density in iliac crest biopsies from patients with osteoporosis: a paired study before and after treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1150–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabet Y, Kohavi D, Muller R, Chorev M, Bab I. Intermittently administered parathyroid hormone (1–34) reverses bone loss and structural impairment in orchiectomized adult rats. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:1436–43. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-1876-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato M, Westmore M, Ma YL, Schmidt A, Zeng QQ, Glass EV, et al. Teriparatide [PTH(1–34)] strengthens the proximal femur of ovariectomized nonhuman primates despite increasing porosity. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:623–9. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hock JM, Gera I. Effects of continuous and intermittent administration and inhibition of resorption on the anabolic response of bone to parathyroid hormone. J Bone Miner Res. 1992;7:65–72. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650070110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin L, Qiu P, Wang LQ, Li X, Swarthout JH, Soteropoulou P, et al. Gene expression profiles and transcription factors involved in parathyroid hormone signaling in osteoblasts revealed by microarray and bioinformatics. J Biol chem. 2003;278:19723–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212226200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygi SP, Rochon Y, Robert Franza B, Aebersold R. Correlation between protein and mRNA abundance in yeast. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1720–30. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo QC, Shen JN, Jin S, Wang J, Huang G, Zhang LJ, et al. Comparative proteomic analysis of human osteosarcoma and SV40-immortalized normal osteoblastic cell lines. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:850–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang KQ, Chen JW, Wang ML, Wang C, Li G, Zheng Z, et al. The expression of insulin-like growth factor-I mRNA and polypeptide in rat osteoblasts with exposure to parathyroid hormone. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116:1916–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang LL, Jiang H, Liu CP, Zhang KQ. The secretome profile in rat osteoblasts intermittently exposed to parathyroid hormone. Chin J Osteoporosis Bone Miner Res. 2008;1:53–8. [Google Scholar]

- Mcsheehy PM, Chambers TJ. Osteoblastic cells mediate osteoclastic responsiveness to parathyroid hormone. J Endocrinol. 1986;118:824–8. doi: 10.1210/endo-118-2-824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiller PC, D'Ippolito G, Roos BA, Howard GA. Anabolic or catabolic responses of MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells to parathyroid hormone depend on time and duration of treatment. J Bone Miner Res. 1999;14:1504–12. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1999.14.9.1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroll MH. Parathyroid hormone temporal effects on bone formation and resorption. Bull Math Biol. 2000;62:163–88. doi: 10.1006/bulm.1999.0146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay CW, Ayscough KR. The actin cytoskeleton: a key regulator of apoptosis and ageing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:583–9. doi: 10.1038/nrm1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morishima N. Changes in unclear morphology during apoptosis correlate with vimentin cleavage by different caspases located either upstream or downstream of Bcl-2 action. Genes to Cell. 1999;4:401–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1999.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Moriwake T, Matsuoka Y, Nakamura T, Seino Y. Potential role of rhIGF-I/IGFBP-3 in maintaining skeletal mass in space. Bone. 1998;22:145S–147S. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(98)00006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silha JV, Mishra S, Rosen CJ, Beamer WG, Turner RT, Powell DR, et al. Perturbations in bone formation and resorption in insulin-like growth factor binding protein-3 transgenic mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1834–41. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2003.18.10.1834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto Y, Kaibuchi K, Hori Y, Fujioka H, Araki S, Ueda T, et al. Molcular cloning characterization of a novel type of regulatory protein (GDI) for the rho proteins, ras p21-like small GTP-binding proteins. Oncogene. 1990;5:1321–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard D, Hart MJ, Platko JV, Eva A, Henzel W, Evans T, et al. The identification and characterization of a GDP-dissociation inhibitor (GDI) for the CDC42Hs protein. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:22860–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall A. Rho GTPase and the actin cytoskeleton. Science. 1998;279:509–14. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Togawa A, Miyoshi J, Ishizaki H, Tanaka M, Takakura A, Nishioka H, et al. Progressive impairment of kidneys and reproductive organs in mice lacking RhoGDI. Oncogene. 1999;18:5373–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones MB, Krutzsch H, Shu H, Zhao YM, Liotta LA, Kohn EC, et al. Proteomic analysis and identification of new biomarkers and therapeutic targets for invasive ovarian cancer. Proteomics. 2002;2:76–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz G, Just I, Kaina B. Rho GTPases are over-expressed in human tumors. Int J Cancer. 1999;81:682–7. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990531)81:5<682::aid-ijc2>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su LF, Knoblauch R, Garabedian MJ. Rho GTPases as modulators of the estrogen receptor transcriptional response. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:3231–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005547200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EP, Boyd J, Frank GR, Takabashi H, Cohen RM, Speeker B, et al. Estrogen resistance caused by a mutation in the estrogen-receptor gene in a man. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1056–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410203311604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korach KS. Insights from the study of animals lacking functional estrogen receptor. Science. 1994;266:1524–7. doi: 10.1126/science.7985022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KCL, Jessop H, Suswillo R, Zaman G, Lanyon LE. The adaptive response of bone to mechanical loading in female transgenic mice is deficient in the absence of estrogen receptor-α and –β. J Endocrinol. 2004;182:193–201. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1820193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcdougall KE, Perry MJ, Gibson RL, Colley SM, Korach KS, Tobias JH. Estrogen receptor-α dependency of estrogen's stimulatory action on cancellous bone formation in male mice. J Endocrinol. 2003;144:1994–9. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen V, Birchman R, Xu R, Otter M, Wu D, Lindsay R, Dempster DW. Effects of reciprocal treatment with estrogen and estrogen plus parathyroid hormone on bone structure and strength in ovariectomized rats. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2331–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI118289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbeer JN, Arlot ME, Meunier PJ, Reeve J. Treatment of osteoporosis with parathyroid peptide (hPTH 1–34) and oestrogen: increase in volumetric density of iliac cancellous bone may depend on reduced trabecular spacing as well as increased thickness of packets of newly formed bone. J Clin Endocrinol. 1992;37:282–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.1992.tb02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang BL, Zhang YQ, Dagher MC, Shacter E. Rho GDP dissociation inhibitor protects cancer cells against drug-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:6054–62. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]