Abstract

Previous studies indicate a role for the glossopharyngeal nerve (GL) in the detection of dietary fats. The present experiments examined the effects of bilateral glossopharyngeal nerve transections (GLx) on the intake of low (4.8%), moderate (16%), and full-fat (100%) corn oil in non-deprived, food-deprived, and water-deprived rats. The rats had access to oils, 0.3 M sucrose, and water in a gustometer that measured number of licks and latency to the first lick during brief access trials. The behavioral measures were used as indices of the amount consumed and the motivation to ingest, respectively. After baseline intakes had stabilized, the rats received GLx or sham transections (Sham), and were then re-tested. Pre and post-surgery responses were compared to determine the impact of GLx on intake and the motivation to ingest. In non-deprived rats, GLx reduced the intake of 4.8% and 16% oils and decreased the motivation to ingest these oils. In food-deprived rats, GLx prevented increases in the ingestion of 4.8% and 16% oils and in the motivation to ingest these oils. In water-deprived rats, GLx reduced the intake of 100% oil and produced a general decrease in the motivation to consume low, moderate, and full-fat emulsions. These results indicate that GL is partially involved in corn oil intake and suggest an interactive effect of oil concentration with homeostatic state.

Keywords: Glossopharyngeal, corn oil, Satiated, Hunger, Thirst, State-dependent

Humans and rodents prefer fat containing foods [1–4]. When intake is tested using sequential 1-bottle tests or a 2-bottle simultaneous test, rodents consume more oil than an oil-free control solution [5–7]. Fat preference in rats occurs early during development: Pre-weaning pups show a preference for corn oil over water by post-natal day 14 [8, 9]. By post-natal day 21, pups display a concentration-dependent oil intake that is maintained into adulthood [3, 4, 8, 9]. This response function is evident when rats are tested for short-duration intake (5 – 30 min) or sham-fed via a gastric or an esophageal fistula [8–12]. Since these procedures minimize the amount of oil consumed and absorbed, fat preference is likely associated with orosensory stimulation rather than post-ingestive feedback. Studies examining olfactory involvement in fat intake have yielded mixed results. Most investigations, however, show that intakes of low and full fats are merely reduced, and not eliminated, in anosmic rodents [7, 13–15].

When dietary fats are introduced into the oral cavity, they are converted rapidly into free fatty acids (FFAs) [16]. The conversion of dietary fat to FFAs is thought to be mediated by lingual lipase secreted by the von Ebner’s glands [16–18]. Although this enzyme is present in various species including rodents, humans, and non-human primates, the amounts present differ across species [19]. Compared with humans, rats show much higher levels of lingual lipase activity [19]. Recent evidence indicates that CD36, a fatty-acid binding membrane protein, may act as a lipid sensor [20–22]. In rodents, CD36 is expressed in the posterior lingual papillae, primarily in taste buds within the circumvallate (CV) and to a much lesser extent those in the foliate [22]. Taste buds in the posterior tongue are innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve (GL), whereas those in the anterior tongue are innervated by the chorda tympani nerve (CT) [23–25]. Application of FFAs to the posterior tongue elicits responses from GL, whereas application of FFAs to the anterior tongue does not elicit responses from CT [26, 27]. Furthermore, CD36-null mice show neither a preference for FFAs nor GL responses to FFAs [26, 27]. These findings indicate that GL may function to transmit the afferent signals for FFA and perhaps for dietary fats.

The present study aims to examine the role of GL in maintaining corn oil intake. Rats were trained to lick water, corn oil emulsions (4.8%, 16%, and 100%), and 0.3 M sucrose from a gustometer before and after bilateral GL (GLx) or sham (Sham) transections. In order to minimize post-ingestive effects, a brief access (10 s per trial) test was used. The number of licks and the latency to the first lick were measured and used as indices of the amount consumed and the motivation to feed, respectively. To determine the impact of GLx on oil intake under different homeostatic states, the rats were tested under non-deprived, water-deprived, and food-deprived conditions in Experiments 1–3, respectively.

General Methods

Subjects

Subjects were 60 naïve male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River, Wilmington, MA). The rats were kept in a vivarium maintained at 23°C and on a 12:12 light:dark schedule with lights on at 7:00 AM. They were housed individually in hanging wire mesh cages and given ad libitum access to food (#2018 Harlan-Teklad) and water except where noted. All procedures used were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Pennsylvania State University (Hershey).

Apparatus

Training and testing were conducted in a custom-made, automated gustometer housed within a sound attenuating booth (Model 252, IAC Acoustics, Bronx, NY). The gustometer was similar in design and function to a ‘Davis Rig’ [28]. It consisted of a Plexiglas box (12.5’ or 31.75 cm on each side) with a stainless steel mesh floor. The back wall of the box had a small opening (0.75’ × 1.25’, w × h; 1.90 × 3.17 cm) located at midline and 2.5’ (6.35 cm) above the floor. A shutter door behind the opening allowed access to 1 of 16 drinking bottles (B1 – B16) with metal sipper tubes. The bottles were held in a rack mounted onto a motorized linear slide. The bottle position and door opening determined the stimulus type and duration, respectively, and were controlled using in-line controllers, a Power1401 interface, and Spike2 software (CED, UK). A contact circuit was incorporated into the gustometer to function as a lickometer [29].

Stimuli

Sucrose (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in distilled water to a concentration of 0.3 M. Corn oil was emulsified with Tween 80 (1.5 in 100 ml) and distilled water or with the surfactant alone. Three oil concentrations (vol/vol) were used: 4.8%, 16%, and 100%. The lowest oil concentration was chosen because it is isocaloric with 0.3 M sucrose and the higher concentrations were selected because they are highly preferred by rats [11].

Data acquisition

Licking data was acquired using a contact lickometer circuit (< 0.5 µA). When the rat licked from a metal sipper tube, an electrical circuit between the tube, the stainless steel floor, and an ADC input channel of the Power1401 was completed. This contact was registered as a voltage change. The lickometer voltage signal was digitized, sampled at 5000 kHz, and acquired onto a host computer using Spike2 (CED, UK). Licking generated a voltage change that ranged between 50 – 300 mV, which equates to a current of 0.05 – 0.3 µA. The order of the drinking bottle and position of the door were also recorded. The number of licks and latency to the first lick were recorded.

Pre-surgical training and testing

Rats were trained to lick from the gustometer before the start of testing. The day prior to the start of spout training, the rats were water-deprived and given access to water for 1.5 hr in the afternoon. All rats were water-deprived on the day prior to the start of spout training and on each spout training day. On training days, each rat was placed in the gustometer and given 32 water trials. Each stimulus trial lasted 10.0 s, and consisted of the duration between the opening and closing of the shutter door. The inter-stimulus interval (ISI) was 5.0 s, and consisted of the interval between the closing of the shutter door of a trial and opening of the shutter door of the next trial. After 3 training days, the rats were tested on the following days for brief access intake of water, oils, and sucrose. During each test, the rats had 32 water (W) trials and 8 trials each of 4.8%, 16% and 100% oil, and 0.3 M sucrose (S). Presentation of the oils and sucrose were counter-balanced across days using a Latin square design. This procedure generated 4 different sequences which started as follows: Test 1 (B1 – B16): W, S, W, 4.8%, W, 16%, W, 100%; W, S, W, 4.8%, W, 16%, W, 100%; Test 2 (B1 – B16): W, 4.8%, W, 100%, W, S, W, 16%, W, 4.8%, W, 100%, W, S, W, 16%; Test 3 (B1 – B16): W, 16%, W, S, W, 100%, W, 4.8%, W, 16%, W, S, W, 100%, W, 4.8%, and Test 4 (B1 – B16): W, 100%, W, 16%, W, 4.8%, W, S, W, 100%, W, 16%, W, 4.8%, W, S. Within each test session, the starting sequence was repeated 4X to yield a total of 64 trials. Testing occurred until intakes stabilized, which took 5 days. The rats were tested under non-deprived, food-deprived, and water-deprived conditions in Experiments 1 – 3, respectively. Food-deprived rats were given 1.5 h access to food at least 2 h after testing, and water-deprived rats were given 1.5 h access to water at least 2 h after testing.

Surgery

At the end of pre-surgery testing, the rats were allocated into 2 groups matched on weight and intakes of 100% oil and sucrose. One group received bilateral GLx and the other group received sham transections. All rats were anesthetized with ketamine hydrochloride (125.0 mg/kg, ip) and xylazine hydrochloride (5.0 mg/kg, ip). The rat was placed supine and a midline incision was made in the neck. The salivary glands and musculature were retracted to expose the GL. The nerve was freed from the surrounding connective tissue sheath and approximately 3.0 mm of the nerve trunk was excised. The procedure was then repeated on the contralateral side. The wound was closed with nylon sutures. Sham rats were treated similarly except that the GLs were not transected. All animals were allowed 9 days to recover and were given ad libitum access to food and water during that period.

Post-surgical training and testing

After recovery, the rats were water-deprived and re-trained to lick water from the gustometer on 2 training days. They were then tested for brief access intake of water, oil, and sucrose across 8 consecutive test days. The training and testing procedures used were the same as those employed pre-surgery.

Histology

At the conclusion of each experiment, the rats were euthanized with euthasol (120.0 mg/kg, ip) and perfused transcardially with physiological saline and 10.0 % buffered formalin. The tongue was removed and stored in formalin. The posterior tongue containing the CV was dissected and embedded in paraffin. The embedded tissue was cut into 10.0 µm sections, mounted onto slides, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Taste buds in the CV were counted under a light microscope. A taste bud was considered morphologically intact when a taste pore or a group of cells converging near the surface of the epithelium was present [24].

Data analyses

For each trial, the number of licks and latency to the first lick were calculated. Lick latency was calculated as the interval between opening of the shutter door and the first lick. In the absence of a lick, the maximum duration of 10.0 s was assigned. Intakes and latencies across trials were averaged for each of the 5 stimuli tested (4.8% oil, 16% oil, 100% oil, 0.3 M sucrose, and water). Pre-surgery intakes were monitored daily to determine when 100% oil and 0.3 M sucrose intakes stabilized across 2 consecutive days. Intakes on Days 4 and 5 were used as pre-surgery intakes and compared with the intakes on post-surgery days (Days 1 – 8). The mean number of licks and lick latencies were analyzed using 2 × (5) × (2) mixed factor (Group × Stimuli × Surgery) ANOVAs with significance set at p < 0.05. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) tests.

Results

Experiment 1: Non-deprived rats

At the start of the experiment, Sham (n = 10) and GLx (n = 12) rats weighed on average 383.6 ± 6.3 g and 398.2 ± 6.8 g, respectively. They had ad libitum access to food and water in their home cages on test days. The 2 groups of rats consumed statistically similar amounts of food (Sham = 33.1 g/day, GLx = 33.0 g/day, t (20) = 0.21, p = 0.83) and water (Sham = 32.0 ml/day, GLx = 32.0 ml/day, t (20) = −0.25, p = 0.81) across test days. The analysis of sucrose and 100% oil on pre-surgery tests 4 and 5 confirmed that intakes had stabilized. Repeated measures ANOVA revealed no significant effects for pre-surgery Test 4 versus Test 5 (F1,36 = 0.2, p = 0.64) or Test Day × Stimuli (F 2,36 = 0.70, p = 0.50). Post-hoc SNKs showed that Sham rats ingested statistically similar amounts of sucrose (p = 0.91) or 100% oil (p = 0.53) across pre-surgery tests 4 and 5. There were also no significant effects for presurgery Test 4 versus Test 5 (F 1,44 = 0.45, p = 0.51) or Test Day × Stimuli (F 2,44 = 1.20, p = 0.31) for GLx rats. Post-hoc tests confirmed that GLx rats consumed statistically similar amounts of sucrose (p = 0.88) and 100% oil (p = 0.28) across pre-surgery tests 4 and 5. Histological analysis of the circumvallate confirmed that GLx led to atrophy of taste buds: Sham rats had an average of 346.0 ± 41.4 whereas GLx rats had an average of 3.0 ± 1.9 taste buds.

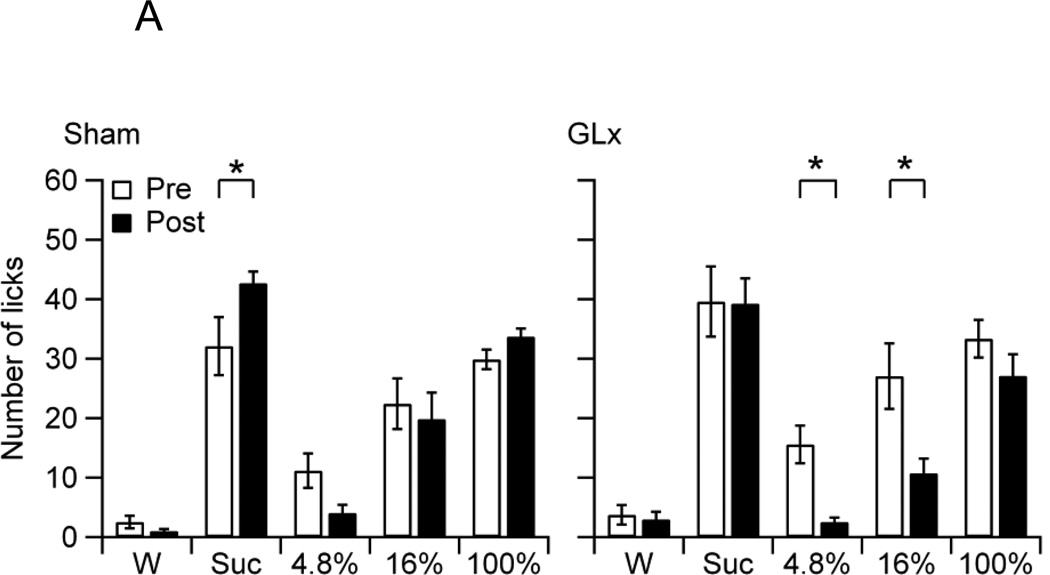

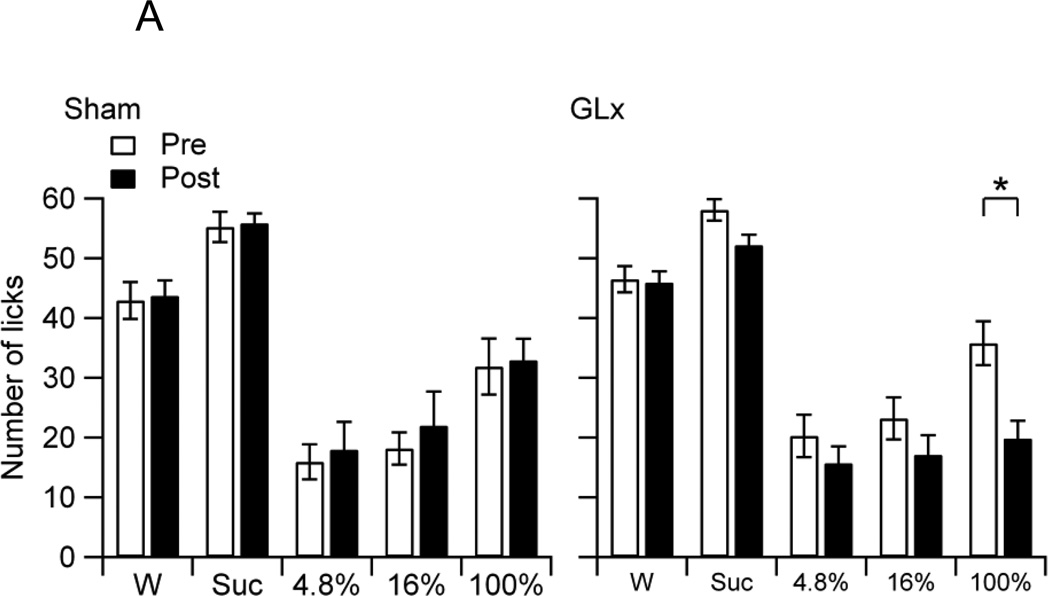

Pre and post-surgery intakes

When averaged across Stimuli and Surgery, Sham and GLx rats had statistically similar overall pre and post-surgery intakes, because the Group effect was not significant (F4, 100 = 0.02, p = 0.89). The main effect for Stimuli, however, was significant, confirming stimulus-dependent intake (F4, 100 = 54.18, p < 0.001). Post-hoc tests revealed that the rats consumed more 4.8%, 16%, or 100% oil than water, that they ingested oil in a concentration-dependent manner, and that they consumed less 100% oil than sucrose (MWater = 2.64 ± 0.61, M4.8% = 8.41 ± 1.36, M16% = 19.93 ± 2.25, M100% = 30.94 ± 1.40, MSuc = 38.50 ± 2.27). The Surgery main effect was also significant, confirming an overall decrease in intake from pre to post-surgery (F1,100 = 12.10, p < 0.001, MPre = 21.95 ± 1.64, MPost = 18.22 ± 1.68). The Stimulus × Surgery and Group × Surgery interactions effects were also significant (F4,100 = 8.75, p < 0.001; F1,100 = 17.14, p < 0.001, respectively). Figure 1A shows the mean number of licks per trial on water, sucrose, and oils of Sham and GLx rats during pre (Pre) and post-surgery (Post) trials. Within group post-hoc comparisons revealed that Sham rats increased sucrose consumption whereas GLx rats decreased consumption of 4.8% and 16% oils following surgery (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1.

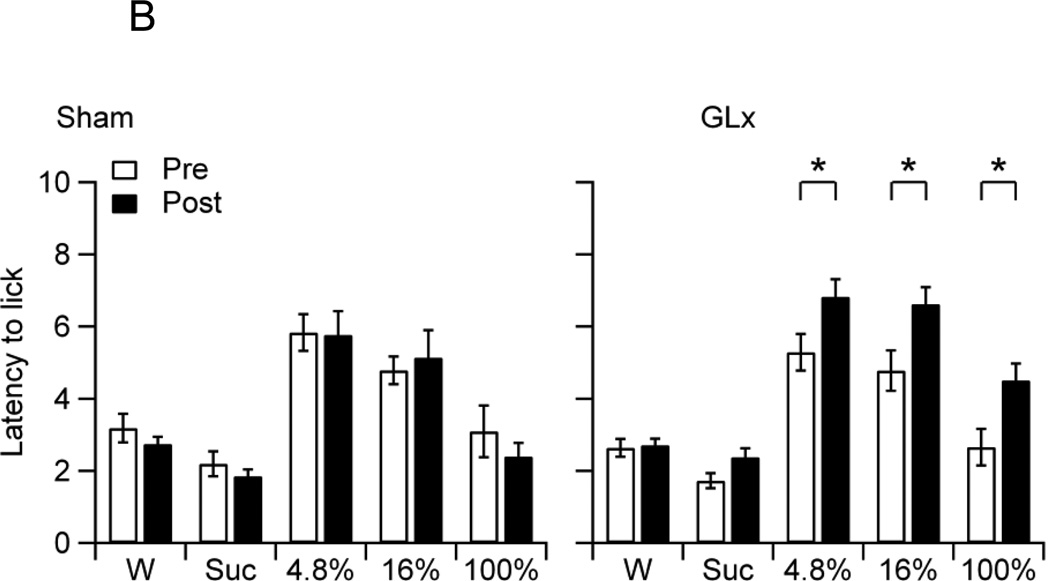

A. The mean number of licks per trial (10.0 s) of water (W), 0.3 M sucrose (Suc), and 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils of non-deprived Sham and GLx rats at pre (Pre) and post-surgery (Post). Sham rats increased intake of Suc from Pre to Post and GLx rats decreased intakes of 4.8% and 16% oils from Pre to Post (* ps < 0.05).

B. The mean latency to the first lick of non-deprived Sham and GLx rats at pre (Pre) and post-surgery (Post) to water (W), 0.3 M sucrose (Suc), and 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils. Sham rats showed a decrease in lick latency for Suc from Pre to Post and GLx rats showed an increase in latencies to lick 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils from Pre to Post (* ps < 0.05).

Pre and post-surgery latencies

The main effect for Group on latency to the first lick was not significant, confirming no differences in overall latencies between GLx and Sham rats (F4,100 = 0.09, p = 0.77). The main effect for Stimuli was significant (F4, 100 = 50.1, p < 0.001). Follow-up tests revealed that the rats displayed the longest latency to lick water, a concentration-dependent decrease in latencies to lick oils, and statistically similar latencies to lick 100% oil and sucrose (MWater = 8.49 ± 0.15, M4.8% = 7.67 ± 0.24, M16% = 6.17 ± 0.28, M100% = 4.38 ± 0.22, MSuc = 4.33 ± 0.28). The main effect of Surgery was significant, confirming an overall increase in lick latencies from pre to post-surgery (F1,100 = 41.48, p < 0.001, MPre = 5.78 ± 0.20, MPost = 6.63 ± 0.23). The Stimulus × Surgery, Group × Surgery, and Group × Stimulus × Surgery interactions were significant (F4, 100 = 15.07, p < 0.001; F1,100 = 28.33, p < 0.001; F4, 100 = 2.53, p = 0.04, respectively). Figure 1B shows the mean latencies to the first lick to water, 0.3 M sucrose, and 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils of Sham and GLx rats on pre and post-surgery trials. Pairwise comparisons confirmed that Sham rats showed a decrease in latencies to lick sucrose (Fig. 1B) and that GLx rats showed an increase in latencies to lick 4.8%, 16% and 100% oils (Fig. 1B).

Experiment 2: Food-deprived rats

At the start of the experiment, Sham rats (n = 8) weighed an average of 363.1 ± 6.8 g and GLx rats (n = 9) weighed an average of 365.1 ± 6.1 g. The rats consumed statistically similar amounts of food (Sham = 13.7 g/day, GLx = 13.7 g/day, t (15) = −0.03, p = 0.98) and water (Sham = 24.4 ml/day, GLx = 23.2 ml/day, t (15) = 0.40, p = 0.70) across test days. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed no significant effects for pre-surgery Test 4 versus Test 5 (F 1,28 = 0.05, p = 0.83) or Test Day × Stimuli (F 2,28 = 0.14, p = 0.88). Post-hoc tests confirmed that Sham rats ingested statistically similar amounts of sucrose (p = 0.85) and 100% oil (p = 0.96) across pre-surgery tests 4 and 5. There were also no significant effects for pre-surgery Test 4 versus Test 5 (F 1,32 = 2.47, p = 0.13) or Test Day × Stimuli (F 2,32 = 2.20, p = 0.13) for GLx rats. Post-hoc tests confirmed that GLx rats consumed statistically similar amounts of sucrose (p = 0.65) and 100% oil (p = 0.09) across pre-surgery tests 4 and 5. Histological analysis of the circumvallate tissue showed that Sham rats had an average of 323.0 ± 56.2 and GLx rats had an average of 15.0 ± 5.6 taste buds.

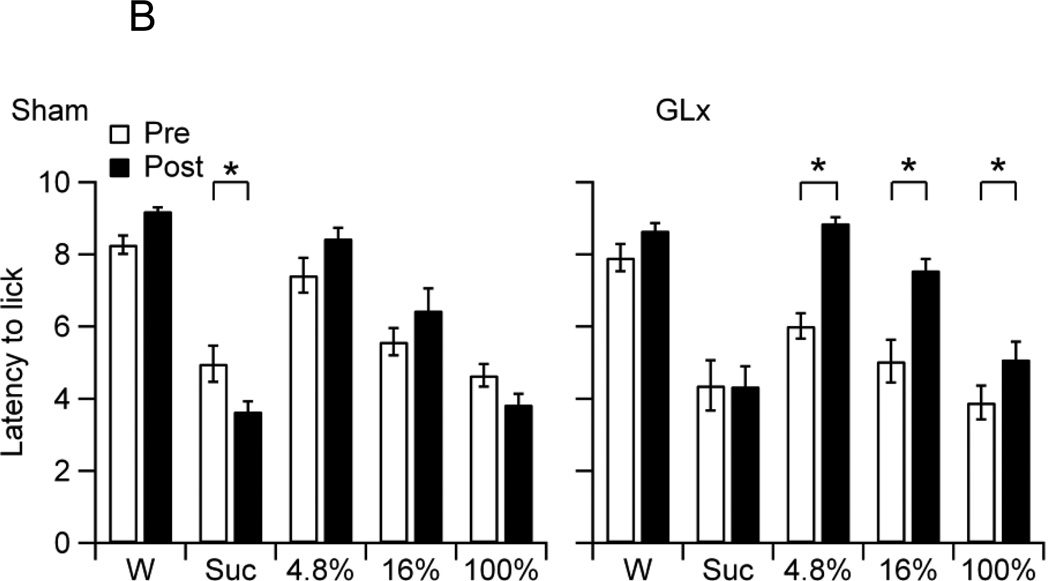

Pre and post-surgery intakes

Both groups of rats had statistically similar overall intakes of test stimuli (F1, 75 = 0.81, p = 0.37). There was a significant main effect for Stimuli (F4, 75 = 51.61, p < 0.001). The rats consumed more 4.8%, 16%, or 100% oil than water, ingested oils in a concentration- dependent manner, and consumed statistically similar amounts of 100% oil and sucrose (MWater = 0.49 ± 0.05, M4.8% = 18.37 ± 2.93, M16% = 38.76 ± 3.47, M100% = 52.44 ± 1.11, MSuc = 54.01 ± 2.56). There was a significant Surgery effect, confirming an overall increase in intakes from pre to postsurgery trials (F1, 75 = 5.51, p = 0.02, MPre = 31.87 ± 2.69, MPost = 33.76 ± 2.70). The Group × Surgery and Group × Stimulus × Surgery interaction effects were significant (F1, 75 = 21.28, p < 0.001, F4, 75 = 5.64, p < 0.001). Figure 2A shows the mean number of licks per trial of Sham and GLx rats to water, 0.3 M sucrose, and oils on pre and post-surgery trials. Pairwise comparisons revealed that Sham rats increased consumption of 4.8% and 16% oils from pre to post-surgery trials (Fig 2A).

Figure 2.

A. The mean number of licks per trial (10.0 s) of water (W), 0.3 M sucrose (Suc0, and 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils of food-deprived Sham and GLx rats at pre (Pre) and post-surgery (Post). Sham rats increased intake of 4.8% and 16% oils from Pre to Post (* ps < 0.05).

B. The mean latency to the first lick of food-deprived Sham and GLx rats at pre (Pre) and post-surgery (Post) to water (W), 0.3 M sucrose (Suc), and 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils. Sham rats showed a decrease in lick latency for 4.8% oil from Pre to Post (* p < 0.05).

Pre and post-surgery latencies

Sham and GLx rats did not differ in overall latencies to the first lick (F1,75 = 0.81, p = 0.37). A significant main effect for Stimuli indicates stimulus dependent differences in lick latencies (F4, 75 = 47.74, p < 0.001). Rats displayed the shortest latencies to lick sucrose and 16% and 100% oils, longer latencies to lick 4.8% oil, and the longest latencies to lick water (MWater = 9.83 ± 0.03, M4.8% = 6.98 ± 0.46, M16% = 3.44 ± 0.50, M100% = 1.62 ± 0.21, MSuc = 2.29 ± 0.41). The main effect for Surgery was significant, indicating a decrease in overall latencies from pre to post-surgery trials (F1, 75 = 6.20, p = 0.02, MPre = 4.98 ± 0.43, MPost = 4.69 ± 0.38). The Stimulus × Surgery and Group × Stimulus × Surgery interaction effects were also significant (F4, 75 = 3.81, p < 0.001; F4, 75 = 2.80, p = 0.03, respectively). Figure 2B shows the mean latencies to the first lick to water, 0.3 M sucrose, and 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils of Sham and GLx rats on pre and post-surgery trials. Post-hoc analysis confirms that Sham rats showed a decrease in the latencies to lick 4.8% oil from pre to post-surgery (Fig. 2B). GLx rats showed no significant differences in pre-post lick latencies.

Experiment 3: Water-deprived rats

At the start of the experiment, Sham (n = 11) and GLx (n = 10) rats weighed on average 416.5 ± 14.1 g and 415.7 ± 11.4 g, respectively. They consumed statistically similar amounts of food (Sham = 26.7 g/day, GLx = 26.5 g/day, t (19) = 0.20, p = 0.85) and water (Sham = 8.4 ml/day, GLx = 9.6 ml/day, t (19) = −1.61, p = 0.12) across test days. A repeated measures ANOVA revealed no significant effects for pre-surgery Test 4 versus Test 5 (F 1,40 = 0.00, p = 0.95). There was, however, a significant Test Day × Stimuli effect (F 2,40 = 17.59, p = 0.00). Post-hoc tests revealed that Sham rats ingested statistically similar amounts of sucrose (p = 0.89) and 100% oil (p = 0.95) across pre-surgery tests 4 and 5. There were, however, significant differences in the amounts of sucrose and 100% oil consumed on each of these test days: Sham rats ingested significantly more sucrose than 100% oil 5 (ps = 0.00). There were no significant effects for pre-surgery Test 4 versus Test 5 (F 1,36 = 2.46, p = 0.13) for GLx rats. In contrast, the Test Day × Stimuli was significant (F 2,36 = 23.62, p = 0.00). Post-hoc tests confirmed that GLx rats consumed statistically similar amounts of sucrose (p = 0.47) and 100% oil (p = 0.14) across pre-surgery test days 4 and 5. Like Sham rats, GLx rats also consumed significantly more sucrose than 100% oil on each of pre-surgery test 4 and test 5 (ps = 0.00). Histology of the circumvallate tissue showed that Sham rats had an average of 398.0 ± 35.7 and GLx rats had an average of 1.0 ± 0.6 taste buds.

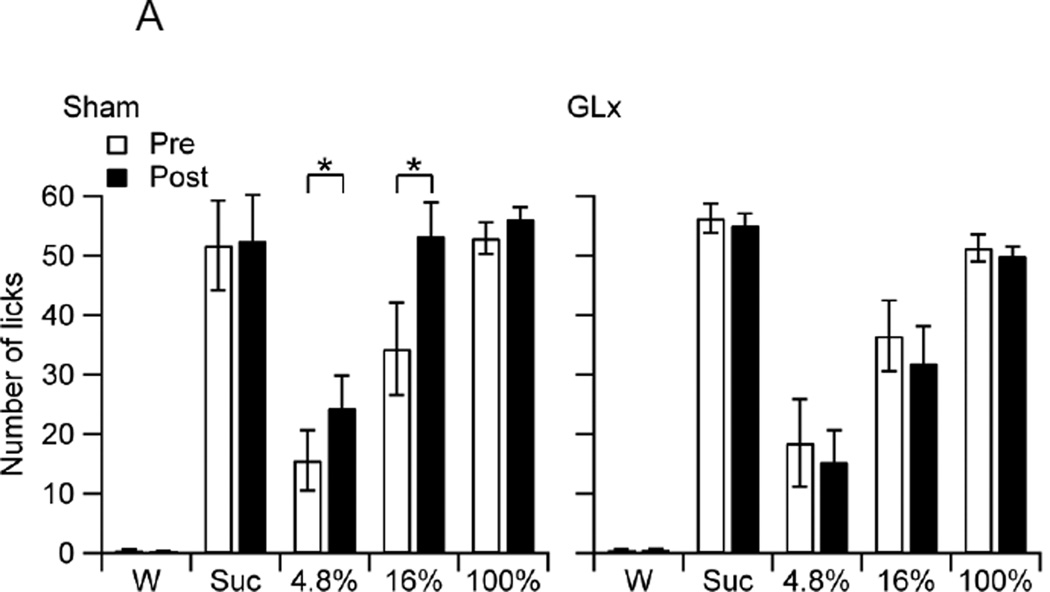

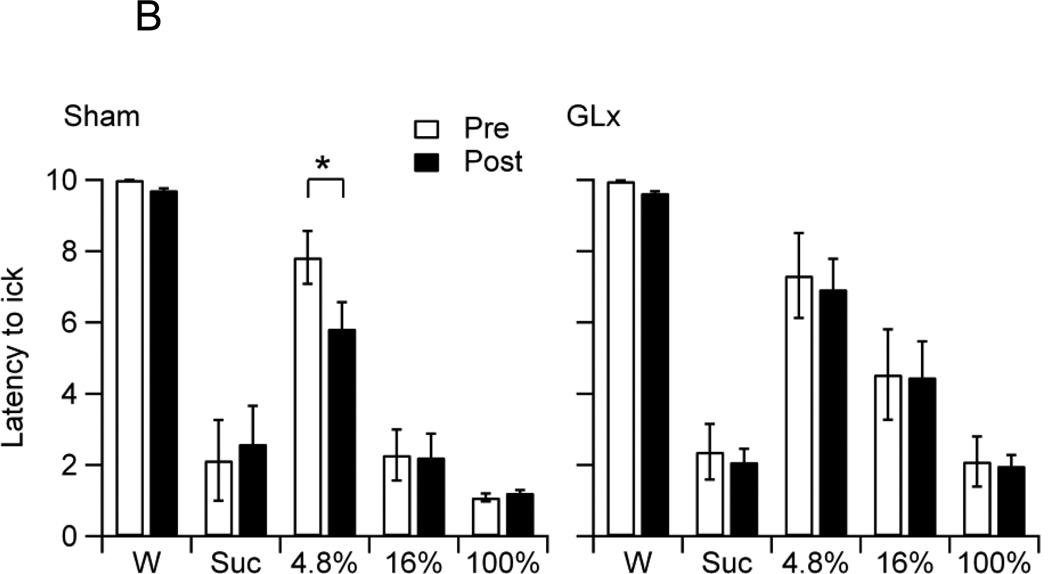

Pre and post-surgery intakes

Sham and GLx rats had overall intakes that were not statistically different (F1,95 = 0.01, p = 0.92). There was a significant main effect for Stimuli (F4, 95 = 57.73, p < 0.001). Rats consumed 4.8% and 16% oils the least, followed by increasing amounts of 100% oil, water, and sucrose (MWater = 44.70 ± 1.23, M4.8% = 17.44 ± 1.76, M16% = 20.12 ± 1.98, M100% = 30.21 ± 2.06, MSuc = 55.23 ± 1.00). The main effect for Surgery was significant, with rats showing a decrease in overall consumption from pre to post-surgery trials (F1, 95 = 8.78, p < 0.001, MPre = 34.71 ± 1.73, MPost = 32.43 ± 1.79). The Stimulus × Surgery and Group × Surgery interactions effects were significant (F4, 95 = 2.48, p = 0.049; F1, 95 = 24.49, p < 0.001, respectively). Figure 3A shows the mean number of licks per trial to water, sucrose and oils of Sham and GLx rats on pre and post-surgery trials. Post-hoc tests revealed that GLx rats decreased consumption of 100% oil from pre to post-surgery (Fig 3A).

Figure 3.

A. The mean number of licks per trial (10.0 s) of water (W), 0.3 M sucrose (Suc), 4.8%, 16% and 100% oils of water-deprived Sham and GLx rats at pre (Pre) and post-surgery (Post). GLx rats decreased intakes of 100% oil from Pre to Post (* p < 0.05).

B. The mean latency to the first lick of water-deprived Sham and GLx rats at pre (Pre) and post-surgery (Post) to water (W), 0.3 M sucrose (Suc), and 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils. GLx rats showed an increase in latencies to lick 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils from Pre to Post (* ps < 0.05).

Pre and post-surgery latencies

There were no differences between Sham and GLx rats in overall latencies (F1,95 = 1.45, p = 0.23). The main effect for Stimuli was significant (F4,95 = 33.41, p < 0.001). The rats displayed the shortest latencies to lick water, 100% oil and sucrose, and longer latencies to lick 4.8% and 16% oils (MWater = 2.82 ± 0.14, M4.8% = 5.92 ± 0.28, M16% = 5.31 ± 0.30, M100% = 3.14 ± 0.29, MSuc = 2.06 ± 0.13). The main effect for Surgery was also significant, with rats displaying an increase in overall lick latencies from pre to post-surgery (F1,95 = 13.60, p < 0.001, MPre = 3.63 ± 0.19, MPost = 4.07 ± 0.22). The Stimulus × Surgery and Group × Surgery interactions were significant (F4, 95 = 3.01, p = 0.02; F1,95 = 30.59, p < 0.001, respectively). Figure 3B shows the mean latencies to the first lick to water, sucrose, and oils of Sham and GLx rats on pre and post-surgery trials. Post-hoc tests indicate that GLx rats showed an increase in the latencies to lick 4.8%, 16%, and 100% oils from pre to post-surgery (Fig. 3B).

General Discussion

In order to determine the impact of GL denervation on maintaining sucrose, oil, and water intakes, we compared post-surgery intakes with those established prior to sham surgery or GLx. After surgery, non-deprived Sham rats displayed an increase in sucrose consumption, but no increases in oil intakes (Fig. 1A). In contrast, non-deprived GLx rats showed no increase in sucrose intake, but decreases in the consumption of 4.8% and 16% oils (Fig. 1A). An examination of the mean latencies to the first lick suggests that the differences in consumption may be due to motivational factors: Sham rats displayed decreases in pre-post lick latencies for sucrose, and GLx rats showed increases in pre-post lick latencies for 4.8% and 16% oils (Fig. 1B). These results are consistent with evidence of smaller bout sizes and decreased ingestion of 16% corn oil in ad libitum fed and watered GLx rats given 23 h access to oil [32]. Notably, our findings demonstrate that bilateral GL denervation decreased but did not fully eliminate consumption of low and moderate fat emulsions and had no effect on the ingestion of 100% oil. Thus, while innervation of the posterior tongue, including the circumvallate taste buds, plays a partial role in maintaining intake of low and moderate fat emulsions, t does not appear to be required for sustaining ingestion of full fat corn oil.

In food-deprived Sham rats, pre-post comparisons indicate increased ingestion of 4.8% and 16% oils (Fig. 2A). The increased consumption of 4.8% oil was accompanied by an increased motivation to ingest this emulsion, as indexed by a pre-post decrease in lick latencies (Fig. 2B). Unlike food-deprived sham-operated controls, food-deprived GLx rats failed to show increases in the consumption of low and moderate fat emulsions (Fig. 2A). Thus, GLx eliminated increases in the ingestion of low to moderate fat emulsions that would otherwise occur. In both Sham and GLx rats, pre-post intakes of 100% oil were not statistically different. These findings, combined with those reported above for satiated rats, provide evidence that posterior lingual sensory input is minimally involved in the intakes of low and moderate fat corn oil emulsions and not involved in the intake of 100% corn oil.

There was no evidence that water-deprived Sham rats changed their sucrose or oil intake following sham transections. Similarly, water-deprived GLx rats showed statistically similar pre-post intakes of sucrose and low-moderate fat emulsions. These rats, however, decreased consumption of 100% corn oil following GL denervation. Water-deprived GLx rats also showed pre-post increases in lick latencies for all oil concentrations, indicating a general decrease in the motivation to ingest oil.

Our results demonstrate that the effects of GLx on fat intake depend on the oil concentration and possibly the deprivation state of the animal. We found that GLx attenuated or prevented increases in the consumption of low-moderate fat emulsions in satiated or hungry rats and of 100% oil in thirsty rats. In each instance, the effect was partial, indicating that posterior taste buds are not essential for dietary fat ingestion. Indeed, the reduced fat intake may not be due solely to the atrophy of posterior lingual taste buds because GL also innervates von Ebner’s glands. These glands are located beneath the circumvallate and foliate papillae and secrete viscous saliva into their papillae clefts via connecting ducts [33–35]. While it remains to be determined if gustatory responses to oils are affected by secretions from von Ebner’s glands, the secretions affect gustatory responses to taste stimuli [16, 36, 37]. A further factor that requires consideration is that the oil emulsions used differ not only in fat content but also in water content. It is possible that the reduced intake of 100% oil by waterdeprived GLx rats resulted from an interactive effect of reduced salivation and dehydration. Thirst appears to reduce the intake of 100% oil: Baseline pre-surgery intakes show that water-deprived rats consumed less 100% oil than sucrose, whereas non-deprived and food-deprived rats consumed the same amounts of sucrose and 100% oil. Perhaps, satiated and hungry rats did not show any attenuation of 100% oil intake because they were fully hydrated. Consequently, future studies might examine this possibility by varying the level of water-deprivation or by using solid foods that differ in oil content with little difference in water content. In addition, the GL nerve includes the posterior lingual somatosensory axons [23]. Thus, it is also possible that GL denervation produced deficits in the ability to detect different oil viscosities. If viscosity or lubricity influences the differential intake of oil emulsions, this factor alone might account for the behavioral changes observed in response to corn oil after glossopharyngeal nerve transaction.

While it was not the primary focus of this study, we can speculate on how deprivation might alter intakes of sucrose and oils. Non-deprived rats displayed a concentration-dependent increase in the motivation to ingest oil and a corresponding increase in intake. Furthermore, they consumed less 100% corn oil than 0.3 M sucrose, indicating that oil was less preferred. Consistent with previous reports that hunger or thirst increases sucrose consumption [30, 31], our results suggest that hungry or thirsty rats are likely to consume almost twice as much sucrose as satiated rats. Fooddeprived rats show a twofold greater intake of oils compared with satiated rats. The food-deprived rats, however, did not show a preference for sucrose over 100% oil. On the other hand, water-deprived rats showed a preference for sucrose over 100% oil, but did not display a concentration-dependent oil intake. The lack of a concentration-response function among thirsty rats was due to their relatively high intake of 4.8% oil. Thus, hunger is likely to produce a vertical shift in the oil intake function and an increase in the preference for 100% oil, whereas thirst is likely to produce an increase in the preference for a low-fat emulsion with high water content. These speculations arise by comparing data from different experiments. Future studies might use a within-subject design to directly test the impact of food and water-deprivation on sucrose and oil intake.

Our test consisted of a fixed 10 s duration starting from the time the stimulus was presented. While this procedure differs from the more common brief access protocol (10 s from first lick), it is congruent with the fixed duration access used to determine intake preferences (e.g. 1-bottle sequential test or 2-bottle simultaneous test). A fixed duration is very likely to limit the opportunity to sample the taste stimulus. While this may be critical on the first test, the rats in this study were pre-trained with ample opportunities to sample all stimuli prior to surgery. Moreover, only the data from pre-surgery tests 4 and 5 were used as ‘baseline’ when intakes of sucrose and 100% oil had stabilized across 2 consecutive tests. In our setup, which did not incorporate a mechanism to minimize olfactory cues, it was possible for rats to react to the taste stimulus without sampling. During testing, we observed that rats often sniffed the stimulus before sampling. The only way to totally eliminate the role of olfaction is to test anosmic rats.

One limitation of the fixed access procedure used here is that the two behavioral measures are not fully independent. The number of licks a rat can make is limited by when he initiated licking. Nevertheless, the two responses did not always yield the same results. Differences in lick latencies were not always matched by differences in intakes (100% oil in non-deprived rats, and 4.8% and 16% oil in water-deprived GLx rats). Differences in intakes were better matched by differences in lick latencies: they were consistent in all instances except one (4.8% oil in food-deprived Sham rats). Further studies might explore whether these two components of feeding are also related in the standard brief access test.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates that the glossopharyngeal nerve has a moderate role in fat intake during satiation, hunger, and thirst. The state-dependent effects detected emphasize the importance of investigating taste responses across different homeostatic states.

Highlights.

GLx reduced the intakes of low and moderate fats in satiated rats

GLx prevented increases in the intakes of low and moderate fats in hungry rats

GLx reduced the intake of full fat in thirsty rats

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH Grants DK079182 and DC005435. We thank Drs. R. Alberto Travagli and Laura Geran for advice on surgery and histology and Nelli Horvath and Erin Handly for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Drewnowski A. Why do we like fat? J Am Diet Assoc. 1997;97(7 Suppl):S58–S62. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(97)00732-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drewnowski A, Almiron-Roig E. Human Perceptions and Preferences for Fat-Rich Foods. 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamilton CL. Rat's Preference for High Fat Diets. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1964;58:459–460. doi: 10.1037/h0047142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rockwood GA, Bhathena SJ. High-fat diet preference in developing and adult rats. Physiol Behav. 1990;48(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90264-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ackroff K, Vigorito M, Sclafani A. Fat appetite in rats: the response of infant and adult rats to nutritive and non-nutritive oil emulsions. Appetite. 1990;15(3):171–188. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(90)90018-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeda M, Imaizumi M, Fushiki T. Preference for vegetable oils in the two-bottle choice test in mice. Life Sci. 2000;67(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00614-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takeda M, Sawano S, Imaizumi M, Fushiki T. Preference for corn oil in olfactory-blocked mice in the conditioned place preference test and the two-bottle choice test. Life Sci. 2001;69(7):847–854. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(01)01180-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ackerman SH, Albert M, Shindledecker RD, Gayle C, Smith GP. Intake of different concentrations of sucrose and corn oil in preweanling rats. Am J Physiol. 1992;262(4 Pt 2):R624–R627. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.4.R624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith GP, Greenberg D. Orosensory stimulation of feeding by oils in preweanling and adult rats. Brain Res Bull. 1991;27(3–4):379–382. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(91)90128-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hiraoka T, Fukuwatari T, Imaizumi M, Fushiki T. Effects of oral stimulation with fats on the cephalic phase of pancreatic enzyme secretion in esophagostomized rats. Physiol Behav. 2003;79(4–5):713–717. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mindell S, Smith GP, Greenberg D. Corn oil and mineral oil stimulate sham feeding in rats. Physiol Behav. 1990;48(2):283–287. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(90)90314-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Swartz TD, Hajnal A, Covasa M. Altered orosensory sensitivity to oils in CCK-1 receptor deficient rats. Physiol Behav. 2010;99(1):109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kinney NE, Antill RW. Role of olfaction in the formation of preference for high-fat foods in mice. Physiol Behav. 1996;59(3):475–478. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(95)02086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramirez I. Role of olfaction in starch and oil preference. Am J Physiol. 1993;265(6 Pt 2):R1404–R1409. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.265.6.R1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saitou K, Yoneda T, Mizushige T, Asano H, Okamura M, Matsumura S, Eguchi A, Manabe Y, Tsuzuki S, Inoue K, Fushiki T. Contribution of gustation to the palatability of linoleic acid. Physiol Behav. 2009;96(1):142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kawai T, Fushiki T. Importance of lipolysis in oral cavity for orosensory detection of fat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2003;285(2):R447–R454. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00729.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hamosh M, Scow RO. Lingual lipase and its role in the digestion of dietary lipid. J Clin Invest. 1973;52(1):88–95. doi: 10.1172/JCI107177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamosh M, Scow RO. Lingual lipase. Symp Oral Sens Percept. 1973;(4):311–322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeNigris SJ, Hamosh M, Kasbekar DK, Lee TC, Hamosh P. Lingual and gastric lipases: species differences in the origin of prepancreatic digestive lipases and in the localization of gastric lipase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;959(1):38–45. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90147-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baillie AG, Coburn CT, Abumrad NA. Reversible binding of long-chain fatty acids to purified FAT, the adipose CD36 homolog. J Membr Biol. 1996;153(1):75–81. doi: 10.1007/s002329900111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukuwatari T, Kawada T, Tsuruta M, Hiraoka T, Iwanaga T, Sugimoto E, Fushiki T. Expression of the putative membrane fatty acid transporter (FAT) in taste buds of the circumvallate papillae in rats. FEBS Lett. 1997;414(2):461–464. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laugerette F, Passilly-Degrace P, Patris B, Niot I, Febbraio M, Montmayeur JP, Besnard P. CD36 involvement in orosensory detection of dietary lipids, spontaneous fat preference, and digestive secretions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115(11):3177–3184. doi: 10.1172/JCI25299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bradley RM, Mistretta CM, Nagai T. Demonstration of sensory innervation of rat tongue with anterogradely transported horseradish peroxidase. Brain Res. 1986;367(1–2):364–367. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(86)91620-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guth L. The effects of glossopharyngeal nerve transection on the circumvallate papilla of the rat. Anat Rec. 1957;128(4):715–731. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091280406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whiteside B. Nerve overlap in the gustatory apparatus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1927;44:363–377. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fushiki T, Kawai T. Chemical reception of fats in the oral cavity and the mechanism of addiction to dietary fat. Chem Senses. 2005;30(Suppl 1):i184–i185. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjh175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mizushige T, Inoue K, Fushiki T. Why is fat so tasty? Chemical reception of fatty acid on the tongue. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 2007;53(1):1–4. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.53.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith JC. The history of the "Davis Rig". Appetite. 2001;36(1):93–98. doi: 10.1006/appe.2000.0372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hayar A, Bryant JL, Boughter JD, Heck DH. A low-cost solution to measure mouse licking in an electrophysiological setup with a standard analog-to-digital converter. J Neurosci Methods. 2006;153(2):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2005.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beck RC, Self JL, Carter DJ. Sucrose Preference Thresholds for Satiated and Water-Deprived Rats. Psychol Rep. 1965;16:901–905. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1965.16.3.901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Campbell BA. Absolute and relative sucrose preference thresholds for hungry and satiated rats. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1958;51(6):795–800. doi: 10.1037/h0039001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Treesukosol Y, Blonde GD, Jiang E, Gonzalez D, Smith JC, Spector AC. Necessity of the glossopharyngeal nerve in the maintenance of normal intake and ingestive bout size of corn oil by rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2010;299(4):R1050–R1058. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00763.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ellis RA. Circulatory patterns in the papillae of mammalian tongue. Anat Rec. 1959;133(3):579–591. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091330310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hand AR. The fine structure of von Ebner's gland in the rat. J Cell Biol. 1970;44:340–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.44.2.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baumgartner EA. The development of the serous glands (von Ebner's) of the vallate papillae in man. Am J Anat. 1917;22:365–383. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gurkan S, Bradley RM. Secretions of von Ebner's glands influence responses from taste buds in rat circumvallate papilla. Chem Senses. 1988;13(4):655–661. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spielman AI. Interaction of saliva and taste. J Dent Res. 1990;69(3):838–843. doi: 10.1177/00220345900690030101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]