Abstract

Haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is the most widely used cellular therapy. It is the only known cure for some hematologic malignancies and has recently been used for additional indications, such as allograft tolerance induction and treatment of autoimmune diseases. Recent advances have enabled HCT in a wider range of patients with improved outcomes. This Review summarizes the latest developments in this therapy, focusing on issues that will impact future advancement.

Introduction

Haematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) involves the treatment of recipients with irradiation and/or chemotherapy followed by infusion of cells containing haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with or without immune cells, including T cells, B cells and NK cells. These haematopoietic cells can be obtained from bone marrow, cytokine-mobilized peripheral blood or umbilical cord blood. HCT was originally used as a rescue for patients receiving high doses of irradiation and/or chemotherapy to treat malignancies. Such treatments cause failure of hematopoiesis, so the engrafted donor haematopoietic stem cells reconstitute the haematopoietic system. The inclusion of mature immune cells in the donor graft has a major impact on the outcome of HCT. Clinical and laboratory studies have clearly shown that allogeneic HCT can mediate graft-versus-tumor (GVT) effects due to immune attack on host tumors. However, this beneficial effect is largely T cell-mediated and is offset by the associated complication of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) due to the attack of host normal tissues by donor T cells. In addition, high dose irradiation and/or chemotherapy used for conditioning the recipients induces severe toxicity, limiting the use of HCT to younger patients. GVHD is potentiated by conditioning-induced inflammation. In the past 20 years, HCT has been increasingly performed using reduced intensity or non-myeloablative conditioning regimens. Use of the term “non-myeloablative” in this article denotes conditioning that leaves sufficient recipient hematopoiesis in place to avoid lethal marrow failure in the absence of a replacement hematopoietic graft.

HCT can be categorized into autologous and allogeneic based on the source of haematopoietic cells. Advances in HCT have permitted its extension to more diverse donor sources for treatment of a broader range of diseases. In this review, we will summarize advances in HCT research, focusing on the issues that are likely to have the greatest future impact. GVHD is not the focus in our review, as it will be covered in detail by Abedi et al in this issue.

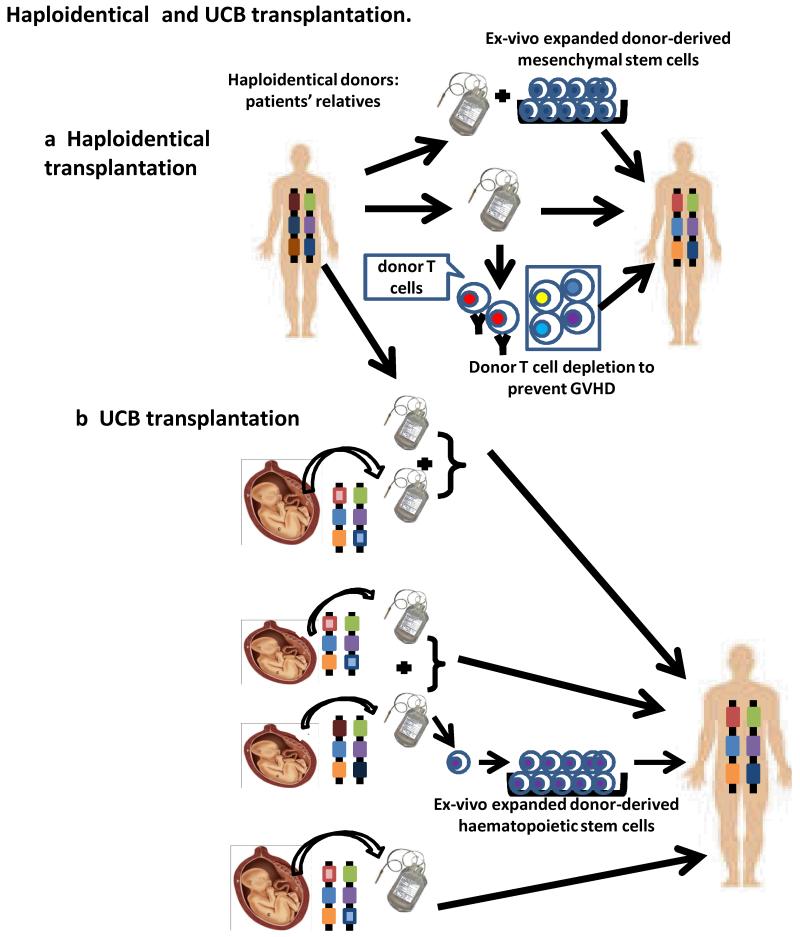

Alternative donors

HLA-matched siblings, when available, are usually the first choice donors for HCT. When such a donor is not available, a matched unrelated donor may be sought. Despite the rapid expansion of donor registries over the past twenty years, availability of unrelated donors is limited, especially for patients with uncommon human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotypes. If an appropriate unrelated donor cannot be found, alternative donors, including HLA-mismatched unrelated donors, umbilical cord blood (UCB) and related haploidentical donors may be considered (Figure 1). Due to the immaturity of the neonatal immune system, a greater degree of HLA mismatching can be allowed for UCB transplantation without excessive GVHD risk. However, the limited number of stem cells present in a UCB unit is a major drawback which is associated with decreased engraftment and delayed immune reconstitution, especially in adult patients, thus limiting the success of umbilical cord blood transplantation (UCBT). This problem may be solved by using UCB from two different donors1, which can preserve GVT effects and enhance immune reconstitution2,3. Other approaches to overcoming the limitation of low stem cell content have been investigated. One is to expand the stem cells ex vivo for transplant. A recent study showed that infusion of ex vivo expanded stem cells from one unit of cord blood together with another unit of unexpanded cord blood resulted in better engraftment and faster haematopoietic recovery4. The use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in the expansion system may enhance the efficacy of expansion of UCB-derived haematopoietic stem cells5. Despite evidence of beneficial effects in vitro, co-transplantation of MCSc did not enhance engraftment of UCB6,7. Frassoni et al directly injected the UCB grafts into bone and reported high rates of engraftment and enhanced haematopoietic recovery with low rates of GVHD8,9. It is as yet unknown how this approach may affect immune reconstitution and GVT effects post-UCB transplantation. In addition, recent studies have shown that grafts consisting of one unit of UCB and haploidentical hematopoietic cells can lead to enhancement of engraftment and haematopoietic reconstitution10-12 (Figure 1b).

Figure 1. Haploidentical and UCB transplantation.

a| Haploidentical grafts can be derived from the patient’s parents, siblings or children (or other relatives). T celldepletion may be performed to prevent GVHD, or donor-derived ex-vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells may be added to the grafts to enhance engraftment or prevent GVHD. b| Although a single unit of UCB graft can be used for HCT, the limited number of haematopoietic stem cells is often associated with delayed engraftment and immune reconstitution. Addition of a second unit of UCB, or ex-vivo expanded haematopoietic stem cells from another unit of UCB, or a haploidentical adult hematopoietic donor graft can enhance engraftment.

For most patients, a haploidentical parent, sibling, child, aunt or uncle, etc, can be identified. However, HLA disparities are associated with increased GVHD, graft rejection and poor immune reconstitution. Extensive T cell-depletion of the donor graft and the recipient, combined with high numbers of donor CD34+ cells, can achieve engraftment without GVHD following intense myeloablative conditioning. However, robust T cell-depletion and immunosuppression for GVHD prevention may affect GVT effects and limit immune reconstitution. NK cells have been shown to play an important role in GVT effects in patients receiving myeloablative conditioning and haploidentical CD34+ cells. Haploidentical transplantation from donors with HLA Class I, killer-cell immunoglobulin-like receptor (KIR) ligand(s) to acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients who lack the KIR lignd(s) was associated with markedly decreased relapse and improved survival rates13,14. In mice, host-reactive (due to missing inhibitory class I MHCligands) donor-derived NK cells inhibited GVHD by killing the host antigen-presenting cells (APCs) required to initiate GVHD, but mediated GVT effects by directly killing the tumor cells13. For patients receiving T cell-replete haploidentical grafts, potent immunosuppressants must be administered to prevent GVHD, which may impair immune reconstitution and GVT effects. Recent studies demonstrated that post-transplant administration of cyclophosphamide can help to prevent both GVHD and graft rejection (discussed below). For both UCB and haploidentical transplants, clinical outcomes can be further optimized by selecting donors who encounter non-inherited maternal (for the donor) HLA antigens in the recipients15,16. Mesenchymal stem cells may also have utility in haploidentical transplantation. When co-transplanted with T cell-depleted haploidentical grafts to pediatric patients17, ex vivo expanded donor-derived MSCs hastened lymphoid recovery. MSCs can suppress alloresponses in vitro18 and may have the ability to suppress refractory GVHD19-21, regardless of their origin19. Thus, MSCs have several potential advantages that warrant further investigation in haploidentical HCT (Figure 1a). Another promising approach involves the titration of donor-derived regulatory T cells (Tregs) with limited numbers of conventional T cells in heavily conditioned haploidentical CD34 cell transplant recipients22.

Reduced intensity conditioning

Originally, myeloablative conditioning was used to maximize killing of malignant cells prior to HCT, which was used as a rescue therapy for the haematopoietic destruction caused by the therapy. However, the toxicity of myeloablative conditioning itself causes morbidity and mortality, and this treatment is considered to be too toxic for use in older patients. Increased intensity of conditioning may also be associated with increased GVHD risk23. Following the realization that HCT also conferred immunotherapeutic benefits in addition to providing hematopoietic rescue, reduced intensity conditioning regimens began to be explored, making HCT available for older patients. GVHD has not been markedly reduced by this approach, perhaps due in part to the increased susceptibility of older patients to this complication. Tumor control may be achieved by GVT effects of donor T cells contained in the initial grafts or by T cells administered in donor leukocyte infusions (DLI). Most reduced intensity conditioning regimens include chemotherapeutic drugs, such as fludarabine, busulfan or cyclophosphamide, and/or low dose of total body irradiation (TBI), and some include antibodies for T cell depletion, such as antithymocyte globulin (ATG). Reduced intensity conditioning protocols have been evaluated in haploidentical24-26 and UCB transplantation27.

The Stanford group has developed a fractionated total lymphoid irradiation (TLI) and ATG protocol based on studies in mice showing enrichment of host NKT cells that induced IL-4-dependent expansion of donor Tregs28. Suppression of GVHD is associated with Th2 polarization of donor T cells29. Clinical trials in patients with hematological malignancies were associated with a very low incidence of GVHD in HLA-identical allogeneic HCT with apparently preserved GVT effects30,31. Enrichment of NKT cells and increased numbers of donor IL-4-producing T cells were detected30,31, suggesting similar mechanisms of GVHD suppression in humans and mice. It remains to be determined whether this approach can reduce GVHD in the HLA-mismatched HCT setting.

Non-myeloablative regimens developed at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) utilized cyclophosphamide, thymic irradiation and ATG32 or anti-CD2 antibody26,33 for T cell depletion in efforts to achieve initial mixed chimerism from HLA-identical32 or haploidentical donors26,33, respectively. The intention of these protocols has been to use delayed DLI to achieve maximal GVT effects while minimizing GVHD, as suggested by studies in mice (see below). The desired outcomes have been variably achieved in these trials, but additional maneuvers are likely to be needed to better control the risk of GVHD from DLI32.

Cyclophosphamide induces the death of activated T cells, and a regimen that includes both pretransplant and post-transplant cyclophosphamide has been evaluated in clinical trials at Johns Hopkins and Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center34,35. Because both recipient T cells and donor T cells in the graft can be activated by alloantigens post-transplant, these are exposed to cyclophosphamide and depleted, diminishing the risks of graft rejection and GVHD. These studies have achieved encouraging engraftment rates with acceptable rates of acute and chronic GVHD, but the GVT effect needs further study.

Enhancing immune reconstitution

HCT may be associated with prolonged immunodeficiency post-transplant, especially after extensive treatment for underlying malignancies and the use of T cell-depleted grafts. Considerable time is needed for T and B cell regeneration, especially when the thymus has lost most of its function due to age and prior therapies. GVHD and the immunosuppressive drugs used for its prevention can also severely delay immune reconstitution. Patients are subject to opportunistic infections which in many cases are fatal. Thus, effective approaches to hastening immune reconstitution following transplantation are needed. Several strategies to achieve this have been under active investigation (Figure 2).

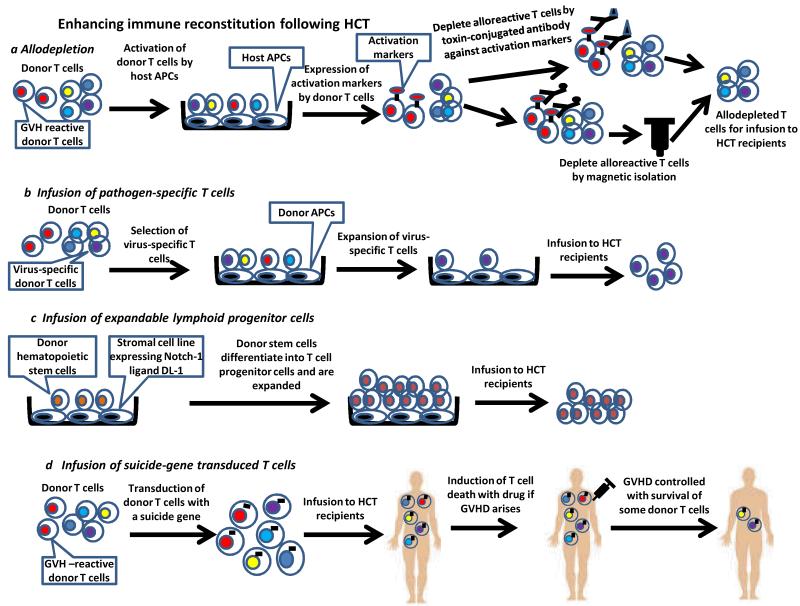

Figure 2. Enhancing immune reconstitution with cellular therapy following HCT.

a|To generate allodepleted donor T cells for transfer, donor T cells are activated by host APCs followed by treatment with toxin-conjugated antibodies against activation markers or by antibody with magnetic separation. b|Pathogen-specific T cells must first be isolated and are then expanded ex vivo before infusion to HCT recipients. c|T progenitor cells can be generated in vitro by coculture of the donor haematopoietic stem cells with the stromal cell line expressing Delta-like-1 (DL-1), which is a ligand of Notch-1. Stem cells will differentiate into T progenitor cells and are expanded in number. The T progenitor cells are then infused to HCT recipients. d|To allow for control of GVHD induced by donor T cells given to enhance immune reconstitution of HCT recipients, donor T cells are first transduced with a suicide gene that enables the cells to be killed by exogenous agents interacting with the transduced gene product. The suicide gene-transduced donor T cells are infused to HCT recipients. When GVHD arises, the transduced donor T cells are induced to die so that GVHD can be controlled. A small number of transduced donor T cells will survive.

Infusion of allodepleted donor T cells

Allodepletion refers to the specific removal of anti-recipient alloreactive T cells. Transfer of allodepleted donor T cells could enhance immune reconstitution by restoring the broad T cell repertoire and thus anti-infectious immunity without inducing GVHD. One strategy for allodepletion removes alloactived T cells based on their expression of activation-associated cell surface markers such as CD25, CD69, CD71 or CD134. Allodepletion is achieved with antibodies conjugated to toxin or micromagnetic beads (Figure 2a). Other strategies remove alloactived T cells with chemotherapeutic drugs36, photodynamic purging37 or based on proliferation38. Despite extensive in vitro studies, only a few clinical trials have been conducted with this approach. Their results, while encouraging with respect to improved immmunocompetence, clearly demonstrate that complete specific allodepletion has not been achieved, as GVHD is still a major problem39-41. There are several potential limitations to these allodepletion strategies, including unsynchronized expression of activation markers, stimulation of only immunodominant clones, leaving less dominant alloreactive T cells intact, and failure of a single activation marker to identify all alloreactive T cells. The use of two activation markers may improve the efficacy of allodepletion42 and more potent stimulators may trigger higher expression of activation markers43, resulting in better allodepletion38.

Infusion of pathogen-specific T cells (Figure 2b)

Transfer of in-vitro expanded pathogen-specific T cell clones can restore immunity against Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus infections following HCT. These virus-specific T cells can be selected using antigen-specific tetramers and expanded in vitro. Infusion of these T cells can lead to successful disease control44,45. The cumbersome isolation and expansion processes, requiring special expertise, and the ability to only restore immunity to selected infectious agents, currently limit the general applicability of the approach. However, it may be possible to broaden its utility, since effector populations have been successfully generated against multiple viruses for post-transplant immunotherapy46. Third-party allogeneic EBV-specific T cells have demonstrated efficacy in controlling EBV-associated malignancy47,48,suggesting that this therapy could be used when HCT donor-derived T cells are not available, as in UCBT.

Transplantation of expanded lymphoid progenitor cells (Figure 2c)

The number of lymphoid progenitor cells accessing the thymus can limit T cell reconstitution49,50, and the addition of T lymphoid progenitors to the donor graft has been shown to enhance immune reconstitution following experimental allogeneic HCT. Zakrzewski et al51 and Dallas et al52 showed that transfer of T cell precursors generated in vitro by manipulating the Notch signaling pathway can enhance immune reconstitution. In addition to boosting immune recovery, transplanting these T cell precursors enhanced GVT effects without inducing GVHD51,53. A recent study shows that co-transplantation of human in vitro generated T cell precursors with CD34+ cells results in rapid production of T cells in immunodeficient mice, suggesting that this approach has considerable promise54.

Transfer of suicide gene-transduced donor T cells (Figure 2d)

Several groups have investigated the use of suicide gene-transduced donor T cells to enhance immune reconstitution while controlling GVHD. The transgene enables the rapid killing of donor T cells when GVHD arises. In a non-randomised phase I-II clinical trial, Ciceri et al infused herpes-simplex thymidine kinase suicide gene-transduced donor T cells to recipients of haploidentical HCT following myeloablative conditioning55. Administration of these tranduced donor T cells led to better immune reconstitution and fewer infections. In patients who developed GVHD, administration of ganciclovir, which kills transgene-positive T cells, effectively controlled GVHD, although a short course of other immunosuppressants was also needed in some patients. Despite control of GVHD by ganciclovir administration, some transduced donor T cells survived and contributed to immune reconstitution. One interesting finding in this study was that administration of gene-transduced donor T cells enhanced the reconstitution of non-transduced donor-derived T cells, suggesting that the transduced T cells facilitated the expansion or the de novo generation of donor T cells.

Di Stasi et al56 tested this strategy using a different gene construct for transduction of donor T cells. The construct fuses human caspase 9 to a modified human FK-binding protein, whose dimerization in the presence of a synthetic dimerizing drug leads to the activation of caspase 9 and thus rapid death of cells expressing the construct. Donor T cells underwent allodepletion by CD25-conjugated immunotoxin and were then transduced with this construct. Selected transduced donor T cells were given to 5 patients receiving haploidentical CD34+ cells after myeloablative conditioning. Four of these patients developed GVHD, which was promptly and effectively controlled by administration of the dimerizing drug AP1903 without the use of other immunosuppressants. AP1903 depleted >90% of transduced donor T cells within 24 hours of injection. As in Ciceri’s study, AP1903 did not deplete all transduced donor T cells and virus-specific donor T cells were at least to some degree preserved, perhaps explaining the absence of viral infections in all 5 patients despite receipt of T cell-depleted grafts. Compared to the thymidine kinase suicide gene-based approach, this caspase 9-based approach induces even faster death of the tranduced T cells while sparing ganciclovir for anti-viral therapy. This construct is also less immunogenic. Collectively, infusion of suicide gene-tranduced donor T cells is a promising approach to enhancing immune reconstitution following HCT. However, more clinical studies are required to further determine its efficacy.

Use of biological agents

Several categories of exogenous factors have been shown to enhance immune reconstitution in animal models. Clinical trials did not demonstrate efficacy of keratinocyte growth factor57, despite hopes that it could improve thymic recovery. Encouraging results have been obtained from a small scale clinical trial for the use of sex hormone blockade to enhance thymopoiesis58. Animal studies suggest that keratinocyte growth factor and sex hormone blockade may have synergistic effects59, which needs to be further tested in clinical trials. Clinical trials to determine the effects of growth hormone, IL-2 and IL-7 on immune reconstitution in HCT patients are currently in progress60.

HCT as tumor immunotherapy

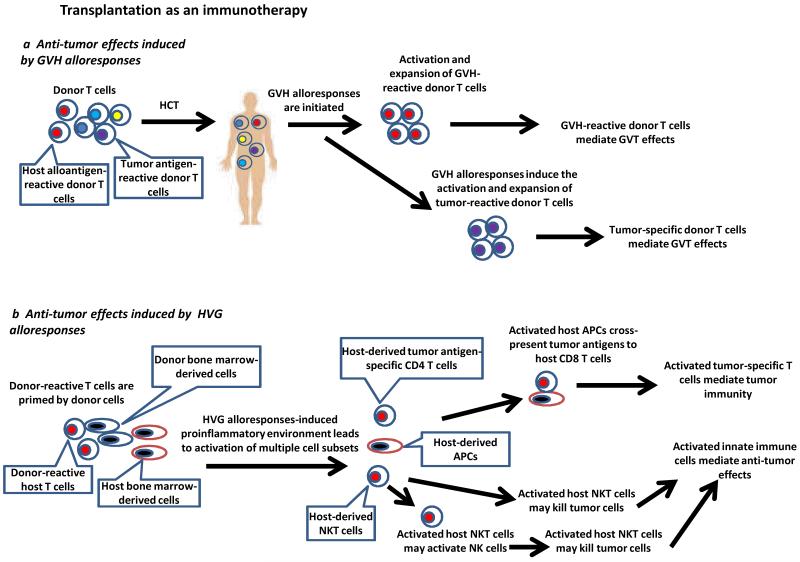

A major mechanism by which HCT mediates GVT effects is via potent alloresponses mounted by host-reactive donor T cells recognizing alloantigens expressed on host cells, including the malignant cells (Figure 3a). The activated donor T cells attack host cells expressing the alloantigens, eliminating both normal and malignant cells. However, recent studies have demonstrated that HCT can potentiate anti-tumor effects via other mechanisms as well.

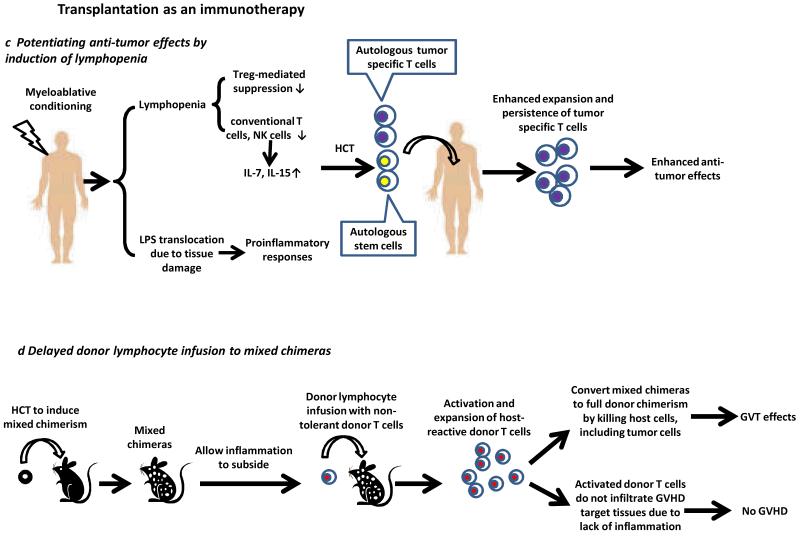

Figure 3. Transplantation as an immunotherapy.

a|GVH-reactive T cells and tumor-specific donor T cells activated during GVH alloresponses may contribute to GVT effects. b| Immune activation due to HVG alloresponses leads to activation of multiple cell types. Activated NKT cells may facilitate the activation of host APCs, such as dendritic cells, and their interactions with tumor-specific CD4 T cells. This leads to enhanced cross-presentation of tumor antigens and activation of tumor antigen-specific host CD8 T cells that kill tumor cells. The activated NKT cells may exert tumorocidal activities or activate NK cells to mediate anti-tumor effects. c|In patients receiving myeloablative conditioning to induce lymphopenia, reduced Treg-mediated suppression, increased availability of cytokines and translocation of LPS collectively lead to enhanced anti-tumor effects mediated by tumor-specific T cells. Autologous HCT is required for rescue of hematologic failure. d|GVHD and GVT effects can be separated by delayed administration of DLI to established mixed chimeras. Host-reactive T cells are activated and eliminate all host hematopoietic cells, including tumor cells, thus mediating GVT effects. The lack of tissue inflammation in established mixed chimeras receiving these DLI prevents GVH-reactive donor T cells from infiltrating the GVHD target tissues.

Induction of tumor-specific immunity by alloresponses

Both GVH and host-versus-graft (HVG) alloresponses must be considered in HCT. These alloresponses are characterized by high frequencies of alloreactive T cells, which may produce an inflammatory environment that promotes concurrent immune responses against tumor-associated antigens. Surprisingly, some clinical studies have demonstrated an association of rejection of donor bone marrow with regression of advanced recipient hematologic malignancies61-64. These observations suggested that HVG alloresponses might trigger tumor antigen-specific responses mediated by host immune cells. An animal model65-67 has demonstrated this phenomenon experimentally. Since GVHD does not occur in patients or animals that lose chimerism61-64, the intentional rejection of engrafted donor bone marrow might provide an interesting strategy for separating GVHD and GVT effects. Our studies in the animal model showed that HVG alloresponses leading to the rejection of engrafted donor bone marrow induce anti-tumor responses65, which are associated with development of tumor-specific cell-mediated cytotoxicity68. Anti-tumor effects are dependent on IFN-γ produced largely by CD8+ T cells65,69 and on host invariant NKT cells, which are not required as a source of IFN-γ, but which induce NK cell and dendritic cell activation67. These data collectively suggest that the HVG alloresponse mediating donor marrow rejection generates a proinflammatory environment that in turn induces both adaptive immune responses against tumor antigens and innate immune responses mediated by NKT cells, whose role is not yet defined, but may include APC activation to promote tumor-specific CTL activation and/or direct tumor cytotoxicity. Notably, the timing of NKT cell activation indicates that it is induced by the alloresponse, in contradistinction to the usual paradigm of innate immunity promoting adaptive immunity. In this instance, an “innate” NKT cell response is induced by an adaptive immune response, namely the alloresponse. A clinical trial is underway to test this strategy in patients. (Figure 3b)

Experimental and clinical data indicate that GVH alloresponses may also potentiate GVT effects by facilitating the generation of tumor antigen-specific T cell responses. Using a parent-to-F1 HCT model, GVHD was associated with the generation of anti-tumor immunity against donor-derived tumors, indicating that GVH alloresponses induced rather than mediated the anti-tumor effects70. Tumor-specific and non-alloreactive T cell clones recognizing a tumor-derived antigen have been isolated from patients who responded to allogeneic HCT for the treatment of renal cell carcinoma, suggesting that tumor-specific T cells can mediate anti-tumor effects induced by allogeneic HCT71. Similar observations have been made in other studies72,73. Further understanding of how alloresponses can facilitate the generation of tumor-specific T cell immunity could help to enhance the GVT effects of HCT (Figure 3a), but the ability to separate this outcome from GVHD remains a challenge.

Potentiation of anti-tumor effects by induction of lymphopenia

Autologous HCT has a role in strategies used to amplify the anti-tumor effects induced by tumor vaccination74 or adoptive immunotherapy75,76 in the absence of either GVH or HVG alloresponses. Multiple factors that potentiate tumor-specific T cell responses have been implicated. Conditioning by irradiation depletes Treg cells that suppress anti-tumor T cell responses75. Lymphopenia induced by conditioning also increases the availability of homeostatic cytokines, such as IL-7 and IL-15, which enhance the responses of tumor-specific T cells75. Translocation of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), which is a potent toll-like receptor 4 agonist and can trigger the production of multiple proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-12 and Type 1 IFNs, results from damage of the gastrointestinal tract by conditioning therapies. Microbial translocation enhances anti-tumor effects mediated by adoptive transfer of tumor-specific T cells and increases their expansion76. Clinical studies demonstrate that increasing the intensity of conditioning increases the potency of adoptive cell therapy against metastatic melanoma77,78 (Figure 3c). Autologous HCT is given in these cases for haematopoietic rescue.

Delayed donor leukocyte infusion to mixed chimeras

We have shown in animal models that potent GVT effects can be induced without GVHD by delayed administration of DLI to established mixed chimeras79,80. The delay prior to DLI administration allows achievement of mixed chimerism, and hence donor-specific tolerance needed to prevent rejection of the DLI, and provides time for the inflammation associated with the original HCT conditioning to subside. GVH-reactive donor T cells in the DLI are activated by recipient professional APCs present in mixed (but not fully allogeneic) chimeras79,81 and mediate potent GVH alloresponses confined to the lymphohaematopoietic system. The lack of inflammation in the host environment markedly reduces the ability of activated, expanded GVH-reactive T cells to infiltrate the epithelial GVHD target tissues81. The GVH alloresponses convert mixed chimerism into full donor chimerism by eliminating all host hematopoietic cells, including the tumor cells, thus mediating GVT effects. Clinical studies translating this finding have demonstrated that GVT effects can be induced with a relatively low incidence and severity of GVHD, even in the HLA-mismatched setting32,82(Figure 3d). However, the clinical studies cited are aimed at avoiding T cell administration in the initial HCT inoculum, a component of the strategy that is likely to be important in avoiding an inflammatory state (due to pre-existing GVHRs in freshly conditioned hosts) prior to DLI.

Studies in the above animal model have revealed the importance of conditioning-induced inflammation in the pathogenesis of GVHD. Delayed DLI was capable of causing systemic or tissue GVHD when it was co-administered with a systemic or local TLR agonist, respectively81. These studies demonstrate the critical role played by inflammation in attracting alloactivated donor T cells to infiltrate the GVHD target tissues, providing an explanation for the well-known ability of bacterial LPS translocation to promote GVHD. Inflammation is associated with upregulation of chemokines and adhesion molecules that may be important in T cell adhesion and transmigration into epithelial tissues. Consistent with this notion, irradiation alone upregulates the expression of multiple chemokines in these tissues, and their expression is further amplified by the GVH alloresponses83. Although delayed administration of a large number of donor T cells to quiescent mixed chimeras induces GVT effects without GVHD, the magnitude of the GVT effect was reduced compared to that in freshly conditioned hosts, showing that the inflammatory host environment helps to enhance GVT effects, but at the expense of markedly increased GVHD. Furthermore, activation of host-reactive donor CD8 T cells was CD4 helper cell-dependent in delayed DLI recipients, but helper-independent in freshly conditioned hosts and the effector functions of donor CD8 T cells were impaired on a per cell basis in delayed DLI recipients. Effector function was restored by co-administration of a TLR agonist84. Moreover, exhaustion of host-reactive donor T cells occurs after mixed chimeras receiving DLI convert to full donor chimerism, due to persistent stimulation by the host alloantigens expressed on the non-haematopoietic tissues85, and this is associated with loss of anti-tumor effects over time80.

HCT for immune tolerance induction

To date, HCT has been mainly used for the treatment of haematologic malignancies and genetic disorders of the hematopoietic system such as immunodeficiency diseases and hemoglobinopathies. Recent research has extended the use of HCT to additional disease categories.

Allogeneic solid organ transplantation

Early murine studies demonstrated that induction of mixed haematopoietic chimerism using lethal irradiation as conditioning could achieve long-term tolerance to allogeneic donor tissues. However, the toxicity of such conditioning and the risk of GVHD associated with the approach are not acceptable for clinical organ transplantation. As non-myeolablative conditioning regimens evolved, studies in large animals confirmed that bone marrow transplantation could promote long-term tolerance to kidney grafts from the same donor, even when mixed chimerism was only transient. Recently, two groups have reported successful combined bone marrow and kidney transplantation using two different conditioning regimens developed at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and Stanford University86-88. These patients were conditioned by reduced intensity conditioning regimens followed by transplantation of HLA-mismatched (MGH)86 or HLA-matched (MGH89 and Stanford87,88) bone marrow cells and kidney grafts simultaneously from the same donor. Immunosuppression was discontinued around 9-12 months post-transplant. Some of these patients are currently off immunosuppression for 2-13 years without evidence of rejection86,89. Persistent mixed chimerism was induced in the HLA-identical studies while only transient mixed chimerism was seen in the HLA-mismatched transplant study at MGH.

The mechanisms underlying the induction of tolerance to donor kidney grafts despite the transient nature of mixed chimerism are under active investigation. In mice, mixed chimerism induces deletion of donor-reactive T cells developing in the thymus after conditioning depletes the pre-existing donor-reactive T cells in the recipients90. However, in the large animal model and HLA-mismatched clinical trial, the initial T cell depletion of the host is less complete than in the mouse and chimerism is only transient. Thus, it is likely that HCT with a kidney transplant induces tolerance of pre-existing donor-reactive mature T cells and that long-term tolerance is not due to lifelong intrathymic deletion. Mechanistic studies suggest a role for host regulatory T cells spared by the conditioning regimen and an active role for the allograft itself91. For the Stanford studies, NKT cells have been implicated in suppressing the rejection of donor graft92.

Recently, 5 of 8 patients receiving combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation from extensively HLA-mismatched, related or unrelated donors after conditioning with the Johns Hopkins regimen involving pre- and post-transplant cyclophosphamide treatment (plus fludarabine and low-dose TBI), were reported to develop full chimerism without GVHD and accept donor kidneys for up to 1 year off of all immunosuppression93. The patients received donor T cells in the PBSC grafts that they were given, and the absence of GVHD was attributed by the authors to the co-infusion of “facilitating cells”, a cell type previously described by this group in murine models94. The lineage origin of these cells is somewhat unclear and they have only been studied by the group conducting this study, who unfortunately did not describe the details of cell preparation in the report due to the proprietary nature of the process, for which the authors declare a financial conflict of interest. Since other investigators, without a financial interest in the outcomes, are unable to independently assess this approach, the broader potential of this approach to safely induce allograft tolerance is unclear. One patient in the small study suffered a near-lethal infectious complication and there is reason to be concerned about immunocompetence in full allogeneic chimeras with peripheral APCs that are extensively HLA-mismatched from the recipient’s thymus if T cell reconstitution occurs. T cell counts remained low for the duration of follow-up and it is possible that these were all donor marrow-derived.

Xenogeneic transplantation

Xenotransplantation is a potential solution for the shortage of organs in clinical transplantation, but B cell-mediated humoral responses and T cell-mediated responses both present major barriers. It has been shown using alpha1,3-galactosyltransferase knockout (GalT KO) mice that induction of mixed chimerism tolerizes T cells and natural antibody-producing B cells and xenogeneic rat heart grafts survive long-term without immunosuppression95. Moreover, NK cell responses to xenogeneic cells are also tolerized by induction of mixed chimerism96.

Treatment of autoimmune diseases

Clinical data obtained over the past 15 years show that autologous HCT can be effective against severe and therapy-refractory autoimmune diseases, including Crohn’s disease, systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and multiple sclerosis97. While autologous HCT can generally induce regression of these autoimmune diseases, relapse frequently occurs at later time points, indicating that tolerance to autoantigens has not been totally restored. Another major issue is that treatment of autoimmune diseases with HCT can later give rise to secondary autoimmune diseases98. Identification of the patient groups most likely to benefit from HCT is an important challenge in each disease. The mechanisms by which autologous HCT corrects autoimmune diseases are unclear. Both clinical99 and experimental100 studies have implicated regulatory T cells. Increased percentages of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ natural regulatory T cells after HCT were associated with disease regression. Zhang et al described a CD8+Foxp3+ regulatory T cell subset in patients receiving HCT that probably acted via TGF-β101. Purging or cytoreducing pre-existing autoreactive lymphocytes by conditioning therapy may be an important mechanism of disease regression, especially when purified CD34+ cells are given back. HCT can then be associated with the generation of a new T cell pool that may be tolerant to self antigens102.

Aside from autologous HCT, allogeneic HCT has been found to mediate a graft-verus-autoimmunity effect, which, like GVT effects, is associated with GVHD. Although performed much less frequently than autologous HCT for the treatment of autoimmune diseases, allogeneic HCT has been associated with regression of multiple refractory autoimmune diseases103. Although graft-versus-host responses that eliminate all host haematopoietic cells, including autoreactive T and B cells, are thought to be main mechanism for this therapeutic effect, intentional induction of mixed haematopoietic allogeneic chimerism has also been shown to reverse or attenuate autoimmune diseases in multiple animal models, including Type 1 diabetes, system lupus erythematosus and arthritis104-109. Induction of mixed chimerism through allogeneic HCT leads to tolerance of autoreactive T cells and B cells104-109. In line with these experimental data, there are case reports of successful treatment of patients with various autoimmune diseases by non-myeloablative allogeneic HCT110-113. However, clinical trials testing this approach are lacking currently. Multiple mechanisms may be involved in restoring tolerance to autoantigens by mixed chimerism induction. While deletion of autoreactive T cells in the thymus post-HCT has been shown in an animal model in which peripheral T cells were removed with T cell-depleting antibody during conditioning for HCT107, other mechanisms must be invoked to explain the tolerization of peripheral autoreactive T cells that persist following some non-myeloablative conditioning protocols, such as one used in the NOD mouse model of Type 1 diabetes106.

Future Perspectives

HCT is a fast-evolving cellular therapy. Substantial progress has been made in the field, including new applications and improved outcomes. Increased safety of this therapy and the use of alternative donors will enable its wider clinical use beyond for the treatment of malignant diseases. Although preventing GVHD while preserving GVT effects and improving immune reconstitution post-transplant are still the most challenging issues, recent advances have led to improved understanding of GVHD, suggesting novel strategies to overcome these hurdles.

Glossary of terms

- Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD)

A pathological process mediated by host alloantigen-activated donor T cells attacking the normal tissues (mainly skin, gut and liver) of the host.

- Myeloablative conditioning

Refers to intensive measures used to prepare hosts for allogeneic HCT. It can include high doses of total body irradiation and/or chemotherapy to destroy pre-existing malignant cells and host immune cells. These highly intensive measures ablate normal haematopoietic cells of the host, which require the infusion of haematopoietic cells to prevent haematopoietic failure.

- Non-myeloablative or reduced intensity conditioning

Less intensive conditioning measures allowing the engraftment of donor cells without ablating the host’s haematopoietic system. Hemaopoietic recovery occurs without engraftment of infused hematopoietic cells.

- Allogeneic transplantation

Mismatched MHC or minor histocompatibility antigens exist between the donor and the host (i.e., transplant from another individual of the same species with the exception of an identical twin).

- Autologous transplantation

Infused hematopoietic cells are from the patients themselves.

- Haploidentical transplantation

The donor and recipient share one HLA haplotype. The donor can be the patient’s parents, siblings, children or other relatives.

Reference List

- 1.Barker JN, et al. Transplantation of 2 partially HLA-matched umbilical cord blood units to enhance engraftment in adults with hematologic malignancy. Blood. 2005;105:1343–1347. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-07-2717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jacobson CA, et al. Immune Reconstitution after Double Umbilical Cord Blood Stem Cell Transplantation: Comparison with Unrelated Peripheral Blood Stem Cell Transplantation. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2012;18:565–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verneris MR, et al. Relapse risk after umbilical cord blood transplantation: enhanced graft-versus-leukemia effect in recipients of 2 units. Blood. 2009;114:4293–4299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-220525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delaney C, et al. Notch-mediated expansion of human cord blood progenitor cells capable of rapid myeloid reconstitution. Nat Med. 2010;16:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nm.2080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson SN, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells in ex vivo cord blood expansion. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology. 2011;24:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernardo ME, et al. Co-infusion of ex vivo-expanded, parental MSCs prevents life-threatening acute GVHD, but does not reduce the risk of graft failure in pediatric patients undergoing allogeneic umbilical cord blood transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46:200–207. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2010.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacMillan ML, Blazar BR, DeFor TE, Wagner JE. Transplantation of ex-vivo culture-expanded parental haploidentical mesenchymal stem cells to promote engraftment in pediatric recipients of unrelated donor umbilical cord blood: results of a phase I-II clinical trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;43:447–454. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frassoni F, et al. Direct intrabone transplant of unrelated cord-blood cells in acute leukaemia: a phase I/II study. The Lancet Oncology. 2008;9:831–839. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70180-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frassoni F, et al. The intra-bone marrow injection of cord blood cells extends the possibility of transplantation to the majority of patients with malignant hematopoietic diseases. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology. 2010;23:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bautista G, et al. Cord blood transplants supported by co-infusion of mobilized hematopoietic stem cells from a third-party donor. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;43:365–373. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu H, et al. Reduced-intensity conditioning with combined haploidentical and cord blood transplantation results in rapid engraftment, low GVHD, and durable remissions. Blood. 2011;118:6438–6445. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-372508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sebrango A, et al. Haematopoietic transplants combining a single unrelated cord blood unit and mobilized haematopoietic stem cells from an adult HLA-mismatched third party donor.: Comparable results to transplants from HLA-identical related donors in adults with acute leukaemia and myelodysplastic syndromes. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology. 2010;23:259–274. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruggeri L, et al. Effectiveness of Donor Natural Killer Cell Alloreactivity in Mismatched Hematopoietic Transplants. Science. 2002;295:2097–2100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruggeri L, et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood. 2007;110:433–440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-038687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Rood JJ, et al. Effect of tolerance to noninherited maternal antigens on the occurrence of graft-versus-host disease after bone marrow transplantation from a parent or an HLA-haploidentical sibling. Blood. 2002;99:1572–1577. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.5.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Rood JJ, et al. Reexposure of cord blood to noninherited maternal HLA antigens improves transplant outcome in hematological malignancies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:19952–19957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910310106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ball LM, et al. Cotransplantation of ex vivo expanded mesenchymal stem cells accelerates lymphocyte recovery and may reduce the risk of graft failure in haploidentical hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Blood. 2007;110:2764–2767. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-087056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nasef A, et al. Immunosuppressive Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cells: Involvement of HLA-G. Transplantation. 2007;84 doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000267918.07906.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Le Blanc K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of steroid-resistant, severe, acute graft-versus-host disease: a phase II study. The Lancet. 2010;371:1579–1586. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60690-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucchini G, et al. Platelet-lysate-Expanded Mesenchymal Stromal Cells as a Salvage Therapy for Severe Resistant Graft-versus-Host Disease in a Pediatric Population. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16:1293–1301. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ringden O, Le Blanc K. Mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease, tissue toxicity and hemorrhages. Best Practice & Research Clinical Haematology. 2011;24:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.beha.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Ianni M, et al. Tregs prevent GVHD and promote immune reconstitution in HLA-haploidentical transplantation. Blood. 2011;117:3921–3928. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-311894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hill GR, et al. Total Body Irradiation and Acute Graft-Versus-Host Disease: The Role of Gastrointestinal Damage and Inflammatory Cytokines. Blood. 1997;90:3204–3213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kasamon YL, et al. Nonmyeloablative HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high-dose posttransplantation cyclophosphamide: effect of HLA disparity on outcome. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2010;16:482–489. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ogawa H, et al. Unmanipulated HLA 2-3 Antigen-Mismatched (Haploidentical) Stem Cell Transplantation Using Nonmyeloablative Conditioning. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:1073–1084. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spitzer TR, et al. Nonmyeloablative haploidentical stem-cell transplantation using anti-CD2 monoclonal antibody (MEDI-507)-based conditioning for refractory hematologic malignancies. Transplantation. 2003;75 doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000064211.23536.AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brunstein CG, et al. Alternative donor transplantation after reduced intensity conditioning: results of parallel phase 2 trials using partially HLA-mismatched related bone marrow or unrelated double umbilical cord blood grafts. Blood. 2011;118:282–288. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-344853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pillai AB, George TI, Dutt S, Strober S. Host natural killer T cells induce an interleukin-4ΓÇôdependent expansion of donor CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T regulatory cells that protects against graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:4458–4467. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-165506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lan F, Zeng D, Higuchi M, Higgins JP, Strober S. Host conditioning with total lymphoid irradiation and antithymocyte globulin prevents graft-versus-host disease: the role of CD1-reactive natural killer T cells. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2003;9:355–363. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(03)00108-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohrt HE, et al. TLI and ATG conditioning with low risk of graft-versus-host disease retains antitumor reactions after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation from related and unrelated donors. Blood. 2009;114:1099–1109. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-211441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lowsky R, et al. Protective Conditioning for Acute Graft-versus-Host Disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1321–1331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050642. HLA-identical transplantation with this non-myeloablative conditioning regimen is associated with very low acute GVHD rates (refs 30 and 31).

- 32.Spitzer TR, et al. Intentional induction of mixed chimerism and achievement of antitumor responses after nonmyeloablative conditioning therapy and HLA-matched donor bone marrow transplantation for refractory hematologic malignancies. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2000;6:309–320. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(00)70056-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaffer J, et al. Regulatory T-cell recovery in recipients of haploidentical nonmyeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation with a humanized anti-CD2 mAb, MEDI-507, with or without fludarabine. Experimental Hematology. 2007;35:1140–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2007.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luznik L, et al. HLA-Haploidentical Bone Marrow Transplantation for Hematologic Malignancies Using Nonmyeloablative Conditioning and High-Dose, Posttransplantation Cyclophosphamide. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14:641–650. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Munchel A, et al. Nonmyeloablative, HLA-haploidentical bone marrow transplantation with high dose, post-transplantation cyclophosphamide. Pediatric Reports; Vol 3, No 2s (2011): News in Onco-Hematology: Learning from Children“, Perugia, 12-14 November 2010. 2011 doi: 10.4081/pr.2011.s2.e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sathe A, Ortega SB, Mundy DI, Collins RH, Karandikar NJ. In Vitro Methotrexate as a Practical Approach to Selective Allodepletion. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2007;13:644–654. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson D. Tolerance induction by removal of alloreactive T cells: in-vivo and pruning strategies. Current opinion in organ transplantation. 2009;14:357–363. doi: 10.1097/mot.0b013e32832ceef4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Godfrey WR, Krampf MR, Taylor PA, Blazar BR. Ex vivo depletion of alloreactive cells based on CFSE dye dilution, activation antigen selection, and dendritic cell stimulation. Blood. 2004;103:1158–1165. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amrolia PJ, et al. Adoptive immunotherapy with allodepleted donor T-cells improves immune reconstitution after haploidentical stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2006;108:1797–1808. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-001909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McIver ZA, et al. Immune Reconstitution in Recipients of Photodepleted HLA-Identical Sibling Donor Stem Cell Transplantations: T Cell Subset Frequencies Predict Outcome. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2011;17:1846–1854. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Solomon SR, et al. Selective depletion of alloreactive donor lymphocytes: a novel method to reduce the severity of graft-versus-host disease in older patients undergoing matched sibling donor stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2005;106:1123–1129. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Samarasinghe S, et al. Functional characterization of alloreactive T cells identifies CD25 and CD71 as optimal targets for a clinically applicable allodepletion strategy. Blood. 2010;115:396–407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-235895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amrolia PJ, et al. Selective depletion of donor alloreactive T cells without loss of antiviral or antileukemic responses. Blood. 2003;102:2292–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cohen JI, et al. Characterization and treatment of chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease: a 28-year experience in the United States. Blood. 2011;117:5835–5849. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-316745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schmitt A, et al. Adoptive transfer and selective reconstitution of streptamer-selected cytomegalovirus-specific CD8+ T cells leads to virus clearance in patients after allogeneic peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Transfusion. 2011;51:591–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.02940.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khanna N, et al. Generation of a multipathogen-specific T-cell product for adoptive immunotherapy based on activation-dependent expression of CD154. Blood. 2011;118:1121–1131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-322610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barker JN, et al. Successful treatment of EBV-associated posttransplantation lymphoma after cord blood transplantation using third-party EBV-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood. 2010;116:5045–5049. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-281873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Haque T, et al. Allogeneic cytotoxic T-cell therapy for EBV-positive posttransplantation lymphoproliferative disease: results of a phase 2 multicenter clinical trial. Blood. 2007;110:1123–1131. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-063008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dunon D, Allioli N, Vainio O, Ody C, Imhof BA. Quantification of T-Cell Progenitors During Ontogeny: Thymus Colonization Depends on Blood Delivery of Progenitors. Blood. 1999;93:2234–2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zlotoff DA, et al. Delivery of progenitors to the thymus limits T-lineage reconstitution after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2011;118:1962–1970. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-324954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zakrzewski JL, et al. Adoptive transfer of T-cell precursors enhances T-cell reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat Med. 2006;12:1039–1047. doi: 10.1038/nm1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dallas MH, Varnum-Finney B, Martin PJ, Bernstein ID. Enhanced T-cell reconstitution by hematopoietic progenitors expanded ex vivo using the Notch ligand Delta1. Blood. 2007;109:3579–3587. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-039842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zakrzewski JL, et al. Tumor immunotherapy across MHC barriers using allogeneic T-cell precursors. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:453–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt1395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eyrich M, et al. Pre-differentiated human committed T-lymphoid progenitors promote peripheral T-cell re-constitution after stem cell transplantation in immunodeficient mice. Eur. J. Immunol. 2011;41:3596–3603. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ciceri F, et al. Infusion of suicide-gene-engineered donor lymphocytes after family haploidentical haemopoietic stem-cell transplantation for leukaemia (the TK007 trial): a non-randomised phase IΓÇôII study. The Lancet Oncology. 2009;10:489–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70074-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Di Stasi A, et al. Inducible Apoptosis as a Safety Switch for Adoptive Cell Therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1673–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106152. These two clinical trials (refs 55 and 56) demonstrate that the transfer of suicide-gene transduced donor T cells to enhance immune reconstitution is safe because GVHD can be effectively controlled.

- 57.Levine JE, Blazar BR, DeFor T, Ferrara JLM, Weisdorf DJ. Long-Term follow-up of a Phase I/II Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Palifermin to Prevent Graft-versus-Host Disease (GVHD) after Related Donor Allogeneic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation (HCT) Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2008;14:1017–1021. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sutherland JS, et al. Enhanced Immune System Regeneration in Humans Following Allogeneic or Autologous Hemopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation by Temporary Sex Steroid Blockade. Clinical Cancer Research. 2008;14:1138–1149. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kelly RM, et al. Keratinocyte growth factor and androgen blockade work in concert to protect against conditioning regimen-induced thymic epithelial damage and enhance T-cell reconstitution after murine bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2008;111:5734–5744. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-136531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seggewiss R, Einsele H. Immune reconstitution after allogeneic transplantation and expanding options for immunomodulation: an update. Blood. 2010;115:3861–3868. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-234096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Colvin GA, et al. Nonengraftment Haploidentical Cellular Immunotherapy for Refractory Malignancies: Tumor-áResponses without Chimerism. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2009;15:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2008.12.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dey BR, et al. Anti-tumour response despite loss of donor chimaerism in patients treated with non-myeloablative conditioning and allogeneic stem cell transplantation. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;128:351–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Guo M, et al. Infusion of HLA-mismatched peripheral blood stem cells improves the outcome of chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia in elderly patients. Blood. 2011;117:936–941. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Spitzer TR, et al. Long-Term Follow-Up of Recipients of Combined Human Leukocyte Antigen-Matched Bone Marrow and Kidney Transplantation for Multiple Myeloma With End-Stage Renal Disease. Transplantation. 2011;91 doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31820a3068. References 61-65 collectively show that rejection of allogeneic hematopoietic cells can be associated with tumor responses without GVHD.

- 65.Rubio MT, et al. Antitumor effect of donor marrow graft rejection induced by recipient leukocyte infusions in mixed chimeras prepared with nonmyeloablative conditioning: critical role for recipient-derived IFN-+|. Blood. 2003;102:2300–2307. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saito TI, Rubio MT, Sykes M. Clinical relevance of recipient leukocyte infusion as antitumor therapy following nonmyeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. Experimental Hematology. 2006;34:1270–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Saito TI, Li HW, Sykes M. Invariant NKT Cells Are Required for Antitumor Responses Induced by Host-Versus-Graft Responses. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;185:2099–2105. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rubio MT, Zhao G, Buchli J, Chittenden M, Sykes M. Role of indirect allo- and autoreactivity in anti-tumor responses induced by recipient leukocyte infusions (RLI) in mixed chimeras prepared with nonmyeloablative conditioning. Clinical Immunology. 2006;120:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rubio MT, et al. Mechanisms of the Antitumor Responses and Host-versus-Graft Reactions Induced by Recipient Leukocyte Infusions in Mixed Chimeras Prepared with Nonmyeloablative Conditioning: A Critical Role for Recipient CD4+ T Cells and Recipient Leukocyte Infusion-Derived IFN-+|-Producing CD8+ T Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2005;175:665–676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.2.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stelljes M, et al. Graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation induces a CD8+ T cell-mediated graft-versus-tumor effect that is independent of the recognition of alloantigenic tumor targets. Blood. 2004;104:1210–1216. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Takahashi Y, et al. Regression of human kidney cancer following allogeneic stem cell transplantation is associated with recognition of an HERV-E antigen by T cells. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1099–1109. doi: 10.1172/JCI34409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Carnevale-Schianca F, et al. Allogeneic nonmyeloablative hematopoietic cell transplantation in metastatic colon cancer: tumor-specific T cells directed to a tumor-associated antigen are generated in vivo during GVHD. Blood. 2006;107:3795–3803. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-3945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Orsini E, et al. Expansion of Tumor-specific CD8+ T Cell Clones in Patients with Relapsed Myeloma after Donor Lymphocyte Infusion. Cancer Research. 2003;63:2561–2568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Filatenkov A, et al. Ineffective Vaccination against Solid Tumors Can Be Enhanced by Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;183:7196–7203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gattinoni L, et al. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;202:907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Paulos CM, et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8+ T cells via TLR4 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2197–2204. doi: 10.1172/JCI32205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rosenberg SA, et al. Durable Complete Responses in Heavily Pretreated Patients with Metastatic Melanoma Using T-Cell Transfer Immunotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2011;17:4550–4557. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wrzesinski C, et al. Increased Intensity Lymphodepletion Enhances Tumor Treatment Efficacy of Adoptively Transferred Tumor-specific T Cells. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2010;33 doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181b88ffc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mapara MY, et al. Donor lymphocyte infusions mediate superior graft-versus-leukemia effects in mixed compared to fully allogeneic chimeras: a critical role for host antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2002;100:1903–1909. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mapara MY, Kim YM, Marx J, Sykes M. Donor lymphocyte infusion-mediated graft-versus-leukemia effects in mixed chimeras established with a nonmyeloablative conditioning regimen: extinction of graft-versus-leukemia effects after conversion to full donor chimerism. Transplantation. 2003;76 doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000072014.83469.2D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chakraverty R, et al. An inflammatory checkpoint regulates recruitment of graft-versus-host reactive T cells to peripheral tissues. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2006;203:2021–2031. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sykes M, et al. Mixed lymphohaemopoietic chimerism and graft-ver suslymphoma effects after non-myeloablative therapy and HLA-mismatched bone-marrow transplantation. The Lancet. 1999;353:1755–1759. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)11135-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mapara MY, et al. Expression of Chemokines in GVHD Target Organs Is Influenced by Conditioning and Genetic Factors and Amplified by GVHR. Biology of Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2006;12:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chakraverty R, et al. The Host Environment Regulates the Function of CD8+ Graft-versus-Host-Reactive Effector Cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;181:6820–6828. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.6820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Flutter B, et al. Nonhematopoietic antigen blocks memory programming of alloreactive CD8+ T cells and drives their eventual exhaustion in mouse models of bone marrow transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:3855–3868. doi: 10.1172/JCI41446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kawai T, et al. HLA-Mismatched Renal Transplantation without Maintenance Immunosuppression. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:353–361. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Scandling JD, et al. Tolerance and Withdrawal of Immunosuppressive Drugs in Patients Given Kidney and Hematopoietic Cell Transplants. American Journal of Transplantation no. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.03992.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Scandling JD, et al. Tolerance and Chimerism after Renal and Hematopoietic-Cell Transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:362–368. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa074191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fudaba Y, et al. Myeloma Responses and Tolerance Following Combined Kidney and Nonmyeloablative Marrow Transplantation: In Vivo and In Vitro Analyses. Am. J. Transplant. 2006;6:2121–2133. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01434.x. These four clinical studies (refs 86-89) collectively demonstrate that combined kidney and bone marrow transplantation can induce immune tolerance to HLA-mismatched and HLA-identical kidney allografts.

- 90.Tomita Y, Khan A, Sykes M. Role of intrathymic clonal deletion and peripheral anergy in transplantation tolerance induced by bone marrow transplantation in mice conditioned with a nonmyeloablative regimen. The Journal of Immunology. 1994;153:1087–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Andreola G, et al. Mechanisms of Donor-Specific Tolerance in Recipients of Haploidentical Combined Bone Marrow/Kidney Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 2011;11:1236–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03566.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Liu YP, Li Z, Nador RG, Strober S. Simultaneous Protection Against Allograft Rejection and Graft-Versus-Host Disease After Total Lymphoid Irradiation: Role of Natural Killer T Cells. Transplantation. 2008;85 doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816361ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Leventhal J, et al. Chimerism and Tolerance Without GVHD or Engraftment Syndrome in HLA-Mismatched Combined Kidney and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Science Translational Medicine. 2012;4:124ra28. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Colson YL, Shinde Patil VR, Ildstad ST. Facilitating cells: Novel promoters of stem cell alloengraftment and donor-specific transplantation tolerance in the absence of GVHD. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2007;61:26–43. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sykes M, Shimizu I, Kawahara T. Mixed Hematopoietic Chimerism for the Simultaneous Induction of T and B Cell Tolerance. Transplantation. 2005;79 doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000153296.80385.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kawahara T, Rodriguez-Barbosa JI, Zhao Y, Zhao G, Sykes M. Global Unresponsiveness as a Mechanism of Natural Killer Cell Tolerance in Mixed Xenogeneic Chimeras. American Journal of Transplantation. 2007;7:2090–2097. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hugle T, Daikeler T. Stem cell transplantation for autoimmune diseases. Haematologica. 2010;95:185–188. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.017038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Daikeler T, et al. Secondary autoimmune diseases occurring after HSCT for an autoimmune disease: a retrospective study of the EBMT Autoimmune Disease Working Party. Blood. 2011;118:1693–1698. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-336156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.de Kleer I, et al. Autologous stem cell transplantation for autoimmunity induces immunologic self-tolerance by reprogramming autoreactive T cells and restoring the CD4+CD25+ immune regulatory network. Blood. 2006;107:1696–1702. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Roord STA, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation in autoimmune arthritis restores immune homeostasis through CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Blood. 2008;111:5233–5241. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-128488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zhang L, Bertucci AM, Ramsey-Goldman R, Burt RK, Datta SK. Regulatory T Cell (Treg) Subsets Return in Patients with Refractory Lupus following Stem Cell Transplantation, and TGF-beta-Producing CD8+ Treg Cells Are Associated with Immunological Remission of Lupus. The Journal of Immunology. 2009;183:6346–6358. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Muraro PA, et al. Thymic output generates a new and diverse TCR repertoire after autologous stem cell transplantation in multiple sclerosis patients. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2005;201:805–816. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Daikeler T, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic SCT for patients with autoimmune diseases. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44:27–33. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Beilhack GF, Landa RR, Masek MA, Shizuru JA. Prevention of Type 1 Diabetes with Major Histocompatibility Complex-Compatible and Nonmarrow Ablative Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplants. Diabetes. 2005;54:1770–1779. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cho SG, et al. Immunoregulatory effects of allogeneic mixed chimerism induced by nonmyeloablative bone marrow transplantation on chronic inflammatory arthritis and autoimmunity in interleukin-1 receptor antagonist-deficient mice. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2006;54:1878–1887. doi: 10.1002/art.21888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nikolic B, et al. Mixed Hematopoietic Chimerism Allows Cure of Autoimmune Diabetes Through Allogeneic Tolerance and Reversal of Autoimmunity. Diabetes. 2004;53:376–383. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.2.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Racine J, et al. Induction of Mixed Chimerism With MHC-Mismatched but Not Matched Bone Marrow Transplants Results in Thymic Deletion of Host-Type Autoreactive T-Cells in NOD Mice. Diabetes. 2011;60:555–564. doi: 10.2337/db10-0827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Smith-Berdan S, Gille D, Weissman IL, Christensen JL. Reversal of autoimmune disease in lupus-prone New Zealand black/New Zealand white mice by nonmyeloablative transplantation of purified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2007;110:1370–1378. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-081497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Takeuchi E, Shinohara N, Takeuchi Y. Cognate interaction plays a key role in the surveillance of autoreactive B cells in induced mixed bone marrow chimerism in BXSB lupus mice. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:363–372. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2010.541172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Bornhañuser M, Aringer M, Thiede C. Mixed Lymphohematopoietic Chimerism and Response in Wegener’s Granulomatosis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2431–2432. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Burt RK, et al. Induction of remission of severe and refractory rheumatoid arthritis by allogeneic mixed chimerism. Arthritis & Rheumatism. 2004;50:2466–2470. doi: 10.1002/art.20451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Jones O, Cahill R. Nonmyeloablative allogeneic bone marrow transplantation of a child with systemic autoimmune disease and lung vasculitis. Immunologic Research. 2008;41:26–33. doi: 10.1007/s12026-007-0015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Loh Y, et al. Non-myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for severe systemic sclerosis: graft-versus-autoimmunity without graft-versus-host disease? Bone Marrow Transplant. 2007;39:435–437. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]