Abstract

Macrophages regulate innate immunity to maintain intestinal homeostasis and play pathological roles in intestinal inflammation. Activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) promotes cellular proliferation, differentiation, survival and wound closure in several cell types. However, the impact of EGFR in macrophages remains unclear. This study was to investigate whether EGFR activation in macrophages regulates cytokine production and intestinal inflammation. We found that EGFR was activated in colonic macrophages in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis and in patients with ulcerative colitis. DSS-induced acute colitis was ameliorated and recovery from colitis was promoted in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice with myeloid cell-specific deletion of EGFR, compared with LysM-Cre mice. DSS treatment increased IL-10 and TNF levels during the acute phase of colitis, and increased IL-10 but reduced TNF levels during the recovery phase in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice. An anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody abolished these effects of macrophage-specific EGFR deletion on DSS-induced colitis in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice. LPS stimulated EGFR activation and inhibition of EGFR kinase activity enhanced LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Furthermore, induction of IL-10 production by EGFR kinase-blocked RAW 264.7 cells, in response to LPS plus IFN-γ, correlated with decreased TNF production. Thus, although selective deletion of EGFR in macrophages leads to increases in both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines in response to inflammatory stimuli, the increase in the IL-10 level plays a role in suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production, resulting in protection of mice from intestinal inflammation. These results reveal an integrated response of macrophages regulated by EGFR in intestinal inflammatory disorders.

Keywords: colitis, cytokine, epidermal growth factor receptor, IL-10, LPS, macrophage, NF-κB, TNF

Introduction

The macrophage, as one of the effector cells of the innate immune system, recognizes pathogen-associated molecular patterns from both pathogens and commensal microorganisms through TLRs. Intestinal macrophages, which are continuously exposed to commensal bacteria in the intestinal tract, express low levels of TLRs and other activating receptors, but exhibit high phagocytic efficacy (1). Thus, under physiological conditions, macrophages in the intestinal tract, as compared with macrophages in most other organs, are hyporesponsive to TLR activation, resulting in rapid microbial uptake and killing in the absence of strong inflammatory responses.

Macrophages display protective and detrimental functions in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, and in animal models of colitis (2). IBD may be caused by dysregulation of the mucosal immune system, which might be due to excessive immune responses to normal microflora. Such immune responses might be initiated in genetically susceptible hosts by alterations in the composition of intestinal microflora and/or deranged epithelial barrier function (3–5). Innate immunity plays an important role in the onset and severity of IBD (6). Macrophages in the inflamed intestinal mucosa are considered part of the destructive force behind IBD, as a result of their involvement in regulating inflammation by production of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as TNF, IL-6, and IL-8 (7, 8).

Protective effects of macrophages in intestinal inflammation include release of cytoprotective prostaglandins in the peri-cryptal stem cell niche to promote epithelial cell wound healing (9). Another mechanism by which macrophages can play a protective role in inflammation is through production of IL-10. IL-10 is expressed by a variety of cells of the innate and adaptive immune systems, including neutrophils, dendritic cells, and macrophages. It is a suppressive cytokine that inhibits the production of proinflammatory cytokines (10). Macrophages serve not only as an important source of IL-10 but also as a target cell for IL-10. IL-10 can inhibit the production of proinflammatory mediators by macrophages, such as release of IL-6, IL-8, and TNF by these cells in response to endotoxin- and IFN-γ stimulation (11, 12). IL-10 also enhances the production of anti-inflammatory mediators such as soluble TNF receptors (13) and inhibits the capacity of monocytes and macrophages to present antigens to T cells (14). Therefore, production of IL-10 in macrophages may represent an autocrine feedback mechanism to constrain activation of macrophages, thereby influencing the development of adaptive immune responses.

Epidermal growth factor (EGF) is the prototypical ligand for EGF receptor (EGFR). EGF is produced by submandibular and Brunner’s glands under physiological conditions (15). However, EGF can be synthesized by other cell types under pathological conditions, such as by intestinal epithelial cells in response to injury (16). Unlike exocrine EGF, other EGFR ligands, including transforming growth factor-α, heparin-binding EGF, and amphiregulin, are expressed by intestinal epithelial cells and myofibroblasts, suggesting that these ligands act in an autocrine or paracrine manner. EGFR is a type 1 tyrosine kinase receptor with an extracellular ligand-binding domain and an intracellular portion that contains a tyrosine kinase domain (17, 18). EGFR can be activated by direct ligand binding and can be transactivated by a wide variety of pharmacological and physiological stimuli, including TNF (19) and bacterial products (20) such as ligands of TLR4 activation (21) in intestinal epithelial cells, which stimulate EGFR ligand release. Biological functions of EGFR include promotion of cellular proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival (17, 18). Although EGFR is considered a tumor promoter, EGF has shown therapeutic potential in human ulcerative colitis (22) and EGFR activation plays a role in ameliorating chronic inflammation, thus limiting colitis-associated tumorigenesis (23).

Several studies have reported that the EGFR and its ligands are present on human macrophages associated with melanoma (24). EGFR has also been found on rabbit peripheral blood monocytes and macrophages and EGF promotes migration and proliferation of these cells (25). However, very little is known regarding the impact of EGFR activation on regulating immune responses in general and in macrophages, specifically.

The purpose of this work was to determine potential roles and mechanisms of EGFR activation in macrophages for regulating cytokine production and experimental colitis. Here we report that EGFR is activated in colonic macrophages in mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis and in patients with ulcerative colitis. Selective deletion of EGFR in macrophages leads to an increase in IL-10 levels, which plays a role in suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production and protects mice from colitis.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice

All animal experiments were performed according to a protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee, USA. Mice harboring a floxed allele of EGFR (Egfrfl/fl) on a C57BL/6 background were crossed with homozygous LysM-Cre mice on a mixed C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N background (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) to generate Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice. LysM-Cre mice express Cre recombinase under the control of the endogenous LysM locus in myeloid cells, including monocytes, mature macrophages, and granulocytes. In Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, Cre-mediated recombination results in deletion of the Egfr gene in the myeloid cell lineage. Correct excision of the floxed Egfr cassette was confirmed in offspring by PCR-based genotyping. Sequences of PCR primers used for genotyping are available upon request. The EGFR expression level in macrophages was tested using Western blot analysis.

Mice and treatment

8- to 10-week old wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME), LysM-Cre, and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice were used for this study. All experimental groups contained balanced numbers of age-matched male and female mice.

Mice were treated with 3% DSS (molecular weight 36–50 kDa, MP Biomedical, Solon, OH) in drinking water (w/v) for 2, 3, or 4 days. 4-day DSS treatment was followed by a 3-day or 7-day recovery period. LysM-Cre and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice treated with 4-day DSS followed by 3-day recovery also received treatment with a neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody or IgG1 κ isotype control antibody (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) via intra-peritoneal cavity injection at 50 μg/day for 4 days (day 2 and 4 after DSS treatment and day 1 and day 2 of recovery).

Mice were also treated with 100 μl of 70 mM 2,6,4-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS) in 50% ethanol intrarectally. Control mice received 100 μl of 50% ethanol intrarectally. Mice were sacrificed 4 days after TNBS treatment (20).

Analysis of colitis

Paraffin-embedded tissue sections of Swiss-rolled whole colon were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for light microscopic examination to assess colon injury and inflammation. Samples from the entire colon were examined by a pathologist blinded to treatment conditions. For assessing DSS-induced colitis, a modified combined scoring system, as previously described (21), including degree of epithelial regeneration (scale of 0–3), distortion/branching (scale of 0–3), inflammation (scale of 0–3) and crypt damage (0–4), percentage of area involved by inflammation (0–4) and crypt damage (0–4), and depth of inflammation (0–3) was applied The total score is 0 (normal) to 24 (severe colitis).

The scoring system used to assess TNBS-induced colitis was modified from a previous scoring system (26, 27); lamina propria mononuclear cell and polymorphonuclear cell infiltration, enterocyte loss, crypt inflammation, and epithelial hyperplasia were scored from 0 to 3, yielding an additive score between 0 (no colitis) and 15 (maximal colitis).

Colonic cell isolation for immunophenotyping

The colon was weighed, cut into small pieces, and digested in DMEM containing 1 mg/ml dispase, 0.25 mg/ml collagenase A, and 25 U/ml DNase at 37° for 20 minutes with shaking. The suspension was passed through a 70-μm cell strainer. Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed with DMEM. Viable cells were counted with trypan blue. Cells were labeled with fluorescent-tagged antibody mixtures containing anti-F4/80-APC (dilution 1: 200) and anti-CD11b-FITC (dilution 1: 100) for 30 min at room temperature. The cells were then fixed in 0.1% paraformaldyhyde/PBS at 4° overnight and analyzed by multi-color flow cytometry to determine the percentage of positive cells using a BD LSRII system (BD Biosciences). The results were calculated as: % of cells x total immune cells/colon weight (gram) = number of cells/gram of colon weight.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) assay

Colon tissues were weighed and homogenized in tissue suspension buffer containing 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0) and 5 mg/ml hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) at a ratio of 50 mg tissue to 1 ml of buffer. MPO level was detected using the reaction buffer containing 17% o-dianisidine (Sigma-Aldrich), 5 mM potassium-phosphate, and 0.0005% H2O2, as described before.(28) Pure MPO (Calbiochem/EMD Biosciences, Darmstadt, Germany) was used to prepare a concentration curve. Tissue suspension buffer was used as negative control. The results were calculated as: U/g colon tissue.

Colonic macrophage isolation

The colon was cut and digested with 1 mg/ml dispase (Sigma-Aldrich), 0.25 mg/ml collagenase A (Sigma-Aldrich), and 25 U/mL DNase (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) for 20 min at 37 °C. Cells were harvested by passing the suspension through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA), followed by centrifugation. Colonic macrophages were isolated from colonic cells using a biotin-conjugated anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA) and streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), as described before (29).

Isolation of spleen lymphocytes, PBMC, and PMN

The spleen was mashed, suspended in DMEM, and passed through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA). The suspended cells were centrifuged at 1500 rpm for 3 min. Lymphocytes were isolated using Lympholyte®-M (Cedar Lane Laboratory, Burlington, NC) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PBMC and PMN were isolated from whole mouse blood using ficoll gradient centrifugation (Sigma-Aldrich). RBC were removed from PMN fraction by lysis of RBC in water.

Colonic epithelial cell isolation

Colonic epithelial cells were isolated using a modified protocol (28). The colon tissues were incubated with 0.5 mM dithiothreitol and 3 mM EDTA at room temperature for 1.5 hours without shaking. Crypts were released from the colon by vigorous shaking. Epithelial cells were sorted using a biotin-labeled E-cadherin antibody (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and streptavidin magnetic beads (Invitrogen).

Real-Time PCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated from homogenized colon tissue and colonic macrophages using an RNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) and was treated with RNase-free DNase. Reverse transcription was performed using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription kit and the 7300 Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The data were analyzed using Sequence Detection System V1.4.0 software. All primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems, TNF (Mm00443259), IL-10 (Mm00439614), IL-6 (Mm00446190), KC (Mm00433859) and COX-2 (Mm00478374). The relative abundance of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA was used to normalize levels of the mRNAs of interest. All cDNA samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Macrophage culture and treatment

The mouse RAW 264.7 monocyte/macrophage cell line (ATCC) and primary mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDMs) isolated from NF-κB reporter mice (HIV-long terminal repeat/luciferase) and immortalized as described before (30) were cultured in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS, 1% Glutamine, 100,000 IU/L penicillin, and 100 mg/L streptomycin at 37 °C with 5 % CO2.

ELISA

RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, catalog # L5293) plus mouse IFN-γ (2.5 ng/ml, Pepro Tech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ) in the presence or absence of mouse IL-10 at 2, 120, or 200 U/ml (Pepro Tech, Inc., Rocky Hill, NJ), neutralizing anti-IL-10 antibody (10 μg/ml) or IgG1 κ isotype control antibody (10 μg/ml), or AG1478 (300 nM, Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) for 8, 18, 24 or 48 hours. Cell culture media were collected to determine the levels of TNF using Mouse TNF ELISA Ready-set-go Kits (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) and IL-10 using Mouse IL-10 Platinum ELISA Kits (eBioscience), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Luciferase activity

To measure NF-κB transcriptional activity, BMDMs isolated from NF-κB reporter mice were treated with LPS (200 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of AG1478 (300 nM) for 6 hours. Cellular lysates were collected for detecting luciferase activity using a standard assay (Promega, Madison, WI), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luciferase activity was expressed as fold change compared to the control group.

Cellular lysate preparation and Western blot analysis

Total cellular lysates were prepared by solubilizing cells using cell lysis buffer containing 1% Triton X-100, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 150 mM NaCl, and protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Rockford, IL). The lysates were mixed with Laemmli sample buffer for SDS-PAGE.

Nuclear fractions were prepared as described before (31), cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and scraped into Buffer A (10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1% NP40, and protease inhibitors), passed through a 21-gauge needle, and centrifuged. The pellet (nuclear fraction) was resuspended in Buffer B (20mM HEPES (pH 7.5), 10 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 500 mM NaCl and 25% glycerol), homogenized, and kept on ice for 30 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was mixed with Laemmli sample buffer for SDS-PAGE.

Western blot analysis was performed using anti-EGFR (Millipore, Billerica, MA), anti-phospho-EGFR (Tyr1068), anti-IκBα, anti-phospho-p38, anti-total-p38, anti-phospho-stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun aminoterminal kinase (SAPK/JNK), anti-total-JNK, anti-total extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)1/2 (Cell Signaling Technology), anti-phospho-ERK1/2 (Promega, Madison, WI), anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-Ki67 antibodies.

Immunohistochemistry

Colon sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated. To detect macrophages, antigen was unmasked using EDTA solution. Mouse sections were stained with a rat anti-mouse F4/80 antibody (Invitrogen), and human sections were stained with a mouse anti-human CD68 antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, CA). Both sections were co-stained with rabbit anti-phospho-EGFR-Tyr1068 antibody (Cell Signaling Technology). For F4/80 and EGFR-Tyr1068 co-staining, the sections were incubated sequentially with FITC-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (Invitrogen) followed by TRITC-labeled anti-rat IgG antibodies (Sigma-Aldrich). For CD68 and EGFR-Tyr1068 co-staining, the sections were incubated sequentially with FITC-labeled anti-rabbit IgG followed by Cy3-labeled anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. West Grove, PA) antibodies. Sections were then mounted using mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA) for nuclear staining. Slides were observed using fluorescence microscopy. FITC, TRITC, and DAPI and FITC, Cy3, and DAPI images were taken from the same field.

For Ki67 staining, antigen retrieval was carried out by using antigen unmasking solution (Vector laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA). The sections were then incubated with a rabbit anti-Ki67 monoclonal antibody (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) at 4° C overnight, followed by 1 hour incubation with a goat anti-rabbit polymer-HRP secondary antibody (Biocare Medical, Concord, CA) for 1 hour at room temperature. The sections were developed using the ImmPACT™ DAB substrate (Vector laboratories, Inc. Burlingame, CA). Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin and observed using light microscopy.

Human samples

Archived paraffin-embedded colonic tissue sections of biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) and healthy controls were accessed from the Human Tissue Acquisition and Pathology Shared Resources at Vanderbilt University. Colon biopsy specimens were obtained from the endoscopically affected colon segment in UC patients and from the distal colon in healthy controls. Samples from patients with moderate to severe UC were obtained at diagnosis, prior to therapy. Only demographic information pertinent to the study design (age at the diagnosis and sex) was collected from patient records (Table 1). The study was approved by the Vanderbilt University Institutional Review Board.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients with UC and controls

| Demographics | UC (n=10) | Control (n=10) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 25.0 (14.0–78.0) | 37.5 (19.0–76.0) | 0.31 |

| Female | 50% (5) | 60% (6) | 0.20 |

Continuous data (age) are summarized with median and categorical data (sex) with percentages. P values are computed with Wilcoxon rank sum test (continuous) and Fisher’s exact test (categorical).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls analysis using Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc. San Diego, CA) for multiple comparisons and t-test for paired samples. A p value < 0.05 was defined as statistically significant. Data are presented as mean±S.E.M.

Results

Induction of EGFR activation in colonic macrophages in mice with experimental colitis and in patients with ulcerative colitis

EGFR regulates multiple aspects of cell homeostasis, including proliferation, differentiation, migration, and survival in many cell types. However, the impact of EGFR activation on regulating immune responses in general remains unclear. As reported before that EGFR is expressed in macrophages (24, 25), our data showed that mouse peritoneal and colonic macrophages expressed EGFR (Figure 1A–B). However, EGFR expression was not detected in blood PMNs, PBMCs or splenic lymphocytes (Figure 1A). Thus, we determined the EGFR activation status in colonic and peritoneal macrophages during intestinal inflammation.

Figure 1. EGFR is activated in colonic and peritoneal macrophages in mice with experimental colitis.

Peritoneal macrophages, blood PMN leukocytes, PBMC and spleen lymphocytes were isolated from WT mice (A). Peritoneal and colonic macrophages were isolated from WT mice with or without 3% DSS treatment for 4 days (B). Cellular lysates were prepared for Western blot analysis to detect EGFR expression and activation using anti-EGFR and anti-EGFR-phospho (P) Y1068 antibodies, respectively. Anti-β-actin antibody was used as a loading control. Each lane represents the combination of the same number of cells pooled from 5 mice (A and B). The relative density was calculated by comparing the density of the EGFR-P-Y1068 or EGFR band to the β-actin band of the same sample and is shown underneath the blot (B). Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were prepared for immunohistochemistry to detect macrophages using a F4/80 antibody and TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody (red) and EGFR activation using anti-EGFR-P-Y1068 antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were stained using DAPI (blue) (C). The merged image is shown. Yellow arrows indicate macrophages with positive staining of EGFR-P-Y1068. Original magnification, X40. Images in this figure are representative of at least 5 mice.

DSS induces colitis in mice by disrupting intestinal epithelial barrier function and activating nonlymphoid cells such as macrophages and PMNs. Increased production of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF and IL-6, by macrophages and PMN phagocytes directly or indirectly suppresses intestinal mucosal barrier repair (32, 33). We therefore selected the DSS colitis model to investigate the role of EGFR in macrophages in controlling intestinal inflammation. EGFR activation, as evidenced by increased tyrosine phosphorylation, was demonstrated by Western blot analysis of colonic and peritoneal macrophages (Figure 1B) and by immunostaining of colon tissues (Figure 1C) prepared from mice treated with DSS for 4 days to induce acute colitis. Analysis of the fold change of relative density showed that EGFR expression levels in peritoneal and colonic macrophages from control mice were similar, but the phosphorylated EGFR levels in colonic macrophages were higher than in peritoneal macrophages from DSS-treated mice (Figure 1B), suggesting that EGFR is more activated in colonic macrophages than peritoneal macrophages during intestinal inflammation.

Macrophages have been shown to contribute to the pathology of IBD. Therefore, we assessed the EGFR activation status in macrophages in colonic tissues from patients with ulcerative colitis (Figure 2A). Immunostaining was performed to detect EGFR phosphorylation in macrophages expressing CD68 (Figure 2B). The number of macrophages with activated EGFR in ulcerative colitis patients was significantly higher than those observed in healthy controls (Figure 2C). These data suggested that EGFR is activated in colonic macrophages from patients with intestinal inflammatory disorders.

Figure 2. EGFR is activated in colonic macrophages in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC).

Endoscopic biopsy sections from patients with UC (n=10) at diagnosis and normal subjects (n=10) were prepared for H & E staining (A) and immunohistochemistry (B) to detect macrophages using an anti-CD68 antibody and Cy3-conjugated secondary antibody (red) and EGFR activation using anti-EGFR-phospho (P)-Y1068 antibody and FITC-conjugated secondary antibody (green). Nuclei were stained using DAPI (blue). Red and green arrows indicate macrophages and EGFR-P-Y1068 positive staining cells, respectively. In the merged image, yellow arrows indicate macrophages with positive staining of EGFR-P-Y1068. Original magnification, x10 for H & E staining, and x40 (insert, x100) for immunohistochemistry. The percentage of macrophages with EGFR activation in UC and control samples were determined by counting the number of EGFR-P-Tyr1068-positive cells among at least 500 CD68-expressing cells (C).

Deletion of EGFR in macrophages ameliorates colitis and enhances recovery in mice treated with DSS

To determine the role of EGFR expression by macrophages in immune responses in vivo, we employed Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice. Although the LysM locus is expressed in myeloid cells (34), including monocytes, mature macrophages, and granulocytes, we did not detect EGFR expression in blood PMN and PBMC (Figure 1A). Thus, the contributing factor to the immune phenotype of Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice might be from mature macrophages. In Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, the EGFR expression level in colonic and peritoneal macrophages was significantly decreased, compared to that in LysM-Cre mice (Figure 3A). EGFR expression in colonic epithelial cells was similar between Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre and LysM-Cre mice (Figure 3A). Thus, Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice exhibit a selective deletion of EGFR in macrophages.

Figure 3. Deletion of EGFR in macrophages ameliorates acute colitis and promotes recovery from colitis in DSS-treated mice.

To confirm the deletion of EGFR in macrophages (Mac), colonic and peritoneal macrophages and colon epithelial (Epi) cells were isolated from LysM-Cre and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice. Total cellular lysates were prepared from cells for Western blot analysis to detect EGFR expression. Anti-β-actin antibody was used as a loading control (A). The colonic macrophage lane represents the combination of the same number of cells pooled from 5 mice. Peritoneal macrophage and epithelial cell lanes represent images from 5 mice. LysM-Cre and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice were treated with 3% DSS in drinking water for 4 days to induce colitis, then mice were provided with water alone for 3 days or 7 days for recovery before sacrifice (DSS4D3DR or DSS4D7DR). Control mice received water alone. Paraffin-embedded colon sections were stained with H&E for light microscopic assessment of epithelial damage (B). Colon injury/inflammation scores are shown (C). MPO activity in the colonic tissue was detected (D). The length of the colon was measured when mice were euthanized (E). * p < 0.05 compared to the water group of LysM-Cre mice, # p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding treatment group in LysM-Cre mice.

To study the effect of EGFR activation in macrophages from mice with DSS-induced colitis, we evaluated colon inflammation and injury in mice treated with DSS for 4 days to induce acute colitis and in mice treated for 4 days with DSS followed by 3 days or 7 days of recovery. DSS-treated LysM-Cre control mice exhibited injury and acute colitis with massive colon ulceration, crypt damage, and severe inflammation during both the acute and recovery phases. These abnormalities were reduced in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice (Figure 3B). In LysM-Cre mice, the inflammation and injury score in the 4-day DSS treatment group was 9.41±3.79, and scores in the 3-day and 7-day recovery groups were 15.19±2.11 and 11.05±3.24, respectively. In Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, the injury and inflammation scores were significantly decreased in the 4-day DSS treatment group (6.00±1.41, p<0.05), the 3-day recovery group (12.11±1.89, p<0.05), and the 7-day recovery group (7.23±3.83, p<0.05) (Figure 3C).

DSS induces neutrophil infiltration in the colon, leading to increased colonic MPO activity, which is therefore an inflammatory marker for colitis. MPO activity in the colon was significantly reduced in DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice following 3 days (66.76%±20.84%, p<0.01) and 7 days (30.08%±5.73%, p<0.01) of recovery, as compared with LysM-Cre mice (Figure 3D). In addition, the colon length was longer in DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice following 3 days (112.84%±10.06%, p<0.001) and 7 days (110.01%±7.39%, p<0.05) of recovery, as compared with LysM-Cre mice (Figure 3E). Neither MPO activity nor colon length in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice treated with DSS for 4 days showed a significant difference as compared with LysM-Cre mice (Figure 3D and 3E). Infiltration of macrophages into the colon, as detected by double staining of F4/80 and CD11b by flow cytometric analysis, was increased in both LysM-Cre and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice treated with DSS for 4 days following 3 days of recovery, but there was no difference in macrophage numbers between these two groups (Supplementary Figure 1). There were no significant body weight changes found in mice treated with DSS for 4 days and following 3 days and 7 days of recovery.

We also sought to determine the role of EGFR in the TNBS-induced colitis model. Mice were administered TNBS intrarectally and euthanized after 4 days of TNBS treatment. TNBS-induced colitis in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice was attenuated as compared with LysM-Cre mice (Supplementary Figure 2).

These results suggested that deletion of EGFR in macrophages ameliorates colitis induced by DSS and TNBS and enhances recovery in mice treated with DSS.

Deletion of EGFR in macrophages differentially regulates IL-10 and TNF production during DSS-induced colitis

Increased proinflammatory cytokine production by macrophages is a hallmark pathological factor in IBD (7, 8) and experimental colitis (32, 35). Activated macrophages in colitis also produce the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 to limit colitis development (10). Therefore, we tested the effects of EGFR deletion in macrophages on pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production during DSS-induced colitis. We employed real-time PCR analysis to detect mRNA levels in the colon tissue and colonic macrophages. Our results showed that IL-10 levels in the colonic tissue of DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice were significantly increased as compared with untreated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre and LysM-Cre mice during both the acute (at 2, 3 and 4 days after DSS treatment) and recovery phases (at 3 and 7 days of recovery) of colitis. However, such changes in IL-10 production were not observed in LysM-Cre mice (Figure 4A). TNF levels in colon tissue of DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice compared with LysM-Cre mice were increased during acute colitis (at 2 and 3 days after DSS treatment), but decreased at 4 days after DSS treatment and during the recovery phase (Figure 4A). Levels of IL-6 and KC, which are macrophage-derived proinflammatory mediators, were persistently higher in the colonic tissues of LysM-Cre mice, compared with Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice (Figure 4A). There was no difference in the production of these cytokines in the water treatment group of Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, compared to LysM-Cre mice (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. EGFR in macrophages regulates cytokine production in DSS-induced acute colitis and recovery from colitis in mice.

LysM-Cre and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice were treated with 3% DSS in drinking water for 2, 3, or 4 days, or treated with DSS for 4 days followed by a 3-day or 7-day recovery period with water. Control mice received water alone. Colonic macrophages were isolated from colon tissues from mice treated with DSS for 4 days followed by a 3-day recovery period. mRNA was isolated from colon tissues (A) and colonic macrophages (B) for real-time PCR analysis of the indicated cytokine mRNAs. The average cytokine mRNA expression level in the water group of LysM-Cre mice was set as 1, and mRNA expression levels in other groups were compared to obtain the fold change. In A, * p < 0.05 compared to the water group of LysM-Cre mice, # p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding treatment group in LysM-Cre mice. n = 5–7 mice in each group.

We also tested the cytokine levels produced by colonic macrophages isolated from mice following 4 days of DSS treatment and following a 3-day recovery phase. Consistent with the cytokine profile in colonic tissues, macrophages from Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice had increased IL-10 levels, but reduced TNF, IL-6 and KC levels, as compared with macrophages from LysM-Cre mice (Figure 4B). Thus, decreased colitis in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice was associated with increased IL-10 and decreased proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine levels in these animals.

IL-10 plays a critical role in suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines and colitis in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice

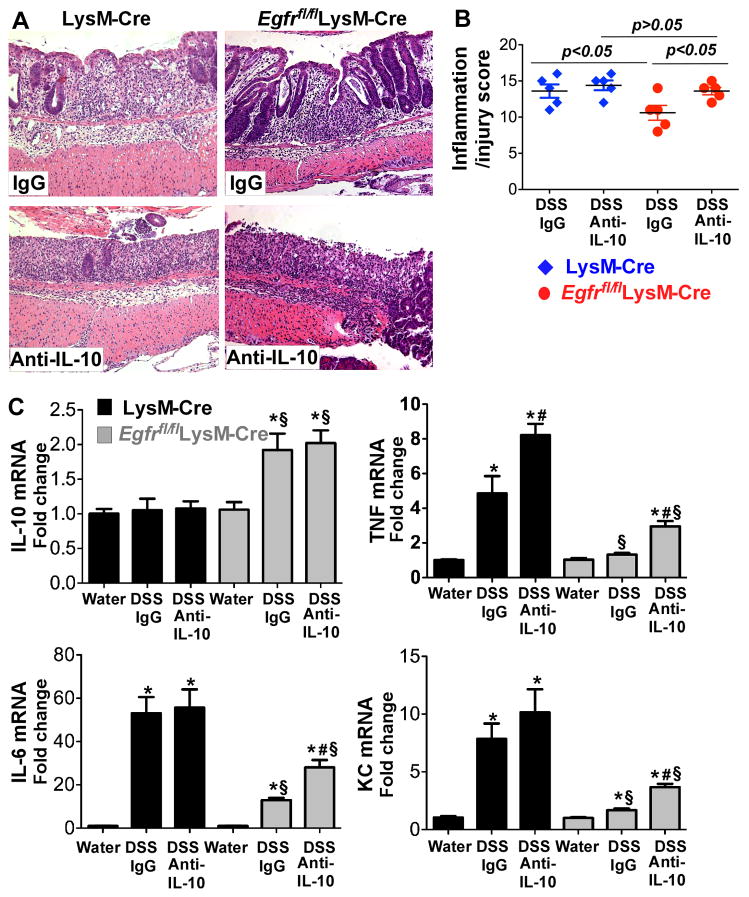

In DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, we observed a persistent increase in IL-10 production throughout the disease process, and increased TNF production in the early stage of acute colitis, but decreased TNF production during the late stage of acute colitis and the recovery phase (Figure 4). Since IL-10 has been shown to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production in macrophages (11, 12), we examined whether the persistent increase in IL-10 production played a role in the development of and recovery from colitis in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice. An IL-10 neutralization was used to test the effects of inhibition of IL-10 on recovery of DSS-induced colitis in LysM-Cre and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice. In Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, as compared with control IgG, treatment with anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody abolished the effects of macrophage-specific EGFR-deficiency on enhanced recovery from colitis, with an inflammation and injury score of 10.60±2.30 in IgG-treated mice and 13.6±1.14 in anti-IL-10-treated mice, respectively (p<0.05, Figure 5A and 5B). As shown in our previous study (20) and in Figure 4 that there was no increase in the IL-10 level in DSS-treated wt mice, the treatment with anti-IL-10 neutralizing antibody did not affect colitis in LysM-Cre mice (13.60±1.85 in IgG-treated mice and 14.4±1.36 in anti-IL-10-treated mice, Figure 5A and 5B). Importantly, the inflammation/injury scores in DSS- and anti-IL-10 antibody-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice were similar (p> 0.05) to those observed in LysM-Cre mice treated with DSS and anti-IL-10 antibody or control IgG (Figure 5A and 5B). These results indicate that increased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 by EGFR-deficient macrophages plays an important role in amelioration of DSS-induced colitis.

Figure 5. IL-10 mediates amelioration of DSS-induced colitis in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice.

LysM-Cre and Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice were treated with 3% DSS in drinking water for 4 days to induce colitis, then mice were provided with water for 3 days for recovery before sacrifice. Control mice received water alone. Mice were also treated with anti-IL-10 antibody or IgG1 isotype control antibody via intraperitoneal injection at 50 mg/day for 4 days (day 2 and 4 after DSS treatment and day 1 and day 2 of recovery). Paraffin-embedded colon sections were stained with H&E for light microscopic assessment of epithelial damage (A). Colon injury/inflammation scores are shown (B). mRNA was isolated from colon tissues for real-time PCR analysis of the indicated cytokine mRNAs (C). The cytokine mRNA expression level in the water group of LysM-Cre mice was set as 100%, and mRNA expression levels in treated mice were compared to the water group. In C, * p < 0.05 compared to the water group of LysM-Cre mice, # p < 0.05 compared to the control IgG treatment group of the corresponding mouse genotypes, § p < 0.05 compared to the corresponding treatment group in LysM-Cre mice. n= 5 mice for each treatment group.

Furthermore, in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, IL-10 mRNA levels in mice treated with anti-IL-10 antibody were similar to those of mice treated with isotype control, whereas TNF, IL-6 and KC mRNA levels were significantly increased in mice treated with the anti-IL-10 antibody (Figure 5C). These data suggest that increased production of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 by EGFR-deficient macrophages plays an important role in downregulating proinflammatory cytokine production, and thus amelioration of DSS-induced colitis.

Increased regenerative responses in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice

It has been reported that macrophages, but not neutrophils or lymphocytes, are necessary for the regenerative response of colonic epithelial progenitors during DSS-induced colitis. Furthermore, macrophages in the peri-cryptal stem cell niche express genes such as COX-2 that are associated with promotion of epithelial cell proliferation (9). Thus, we tested whether EGFR activation in macrophages affects COX-2 expression and we determined the role of COX-2 in colon epithelial cell proliferation in mice during recovery from DSS-induced colitis. We detected colon epithelial cell proliferation by Ki67 staining in colon tissues isolated from DSS-treated mice following a recovery period of 3 or 7 days. In both groups of animals, colon epithelial cell proliferation rates were higher in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice compared with LysM-Cre mice (Figure 6A and B).

Figure 6. COX-2 expression in colonic macrophages is increased in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, which correlates with increased colonic epithelial cell proliferation.

Mice were treated with 3% DSS for 4 days and followed by a 3- or 7-day recovery period, as described in the legend to Figure 3. Paraffin-embedded tissue sections were prepared to detect cell proliferation using Ki67 staining (A). Proliferative nuclei labeled with peroxidase (brown) were visualized using light microcopy. The number of proliferative nuclei per 100 crypts is shown (B). * p < 0.05 compared to the water group of LysM-Cre mice. mRNA was isolated from the colonic macrophages (C) and colon tissues (D) for real-time PCR analysis of COX-2 mRNA expression levels. The cytokine mRNA expression level in control LysM-Cre mice (water only) was set as 100%, mRNA expression levels in other groups were compared to obtain the fold change. n= at least 5 mice in each treatment group.

We examined COX-2 mRNA levels in colonic macrophages isolated from mice after 4 days of DSS treatment followed by a 3-day recovery period. There was no difference between levels of COX-2 expression in colonic macrophages from untreated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice compared with LysM-Cre mice. We were unable to detect significant changes in COX-2 mRNA levels in colonic macrophages isolated from LysM-Cre mice upon DSS treatment. However, the COX-2 mRNA level was significantly increased in colonic macrophages isolated from DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, as compared with the water-treated group (Figure 6C).

In colonic tissues isolated from LysM-Cre mice, COX-2 mRNA expression levels were increased in the 3-day recovery group, but no significant changes were observed in the 7-day recovery group, compared to the water-treated group. In Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, COX-2 mRNA levels were significantly increased in both the 3-day and 7-day recovery group, compared to water-treated groups, and were significantly higher than those in LysM-Cre mice (Figure 6D).

These data suggested that deletion of EGFR in macrophages enhances COX-2 expression, which correlates with increased colon epithelial cell proliferation. These findings may contribute to the accelerated recovery from colitis in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice.

Inhibition of EGFR kinase activity in macrophages regulates LPS- and IFN-γ-stimulated cytokine production in vitro

It is well known that macrophages are classically activated by exposure to two signals (36). IFN-γ primes macrophages for activation, but does not in itself substantially activate macrophages. The second signal is TNF or an inducer of TNF. Under physiological conditions, endogenous TNF is produced by TLR ligation on macrophages. Thus, classically activated macrophages develop in response to IFN-γ and exposure to a microbe or microbial product such as LPS. Inflammatory mediators induced by LPS plus IFN-γ in monocytes/macrophages play important roles in sepsis (37) and inflammatory conditions such as colitis (7, 8). Thus, we determined the role of EGFR in regulating cytokine production in response to LPS plus IFN-γ stimulation in the mouse macrophage cell line RAW 264.7. We used AG1478, an EGFR kinase inhibitor, to inactivate EGFR in macrophages. IL-10 production was upregulated in macrophages under both conditions, with or without EGFR kinase inhibition, upon LPS/IFN-γ treatment for 8 to 48 hours, with a peak at 24 hours of treatment. However, in macrophages with EGFR inhibition, the levels of IL-10 production induced by LPS/IFN-γ treatment for 8 to 24 hours were higher than those in macrophages with EGFR activity. However, there was no difference in IL-10 production at the 48-hour time point of LPS/IFN-γ treatment in macrophages with intact EGFR kinase activity, compared with macrophages undergoing EGFR inhibition (Figure 7).

Figure 7. EGFR kinase activity mediates cytokine production in LPS plus IFN-γ-stimulated macrophages.

RAW 264.7 macrophages were plated in 96-well plates (104 cells/well with 200 μl of medium) and were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) plus IFN-γ (2.5 ng/ml) for 8, 18, 24, or 48 hours in the presence or absence of an EGFR kinase inhibitor, AG1478 (300 nM). Levels of IL-10 and TNF in cell culture supernatants were determined using ELISA. The cytokine level was expressed as pg/ml medium. * p < 0.05 compared to the control of the same treatment time, # p < 0.05 compared to the LPS plus IFN-γ treated group of the same treatment time. Data in this figure are quantified from 4 independent experiments.

LPS/IFN-γ stimulated TNF production at 8, 18 and 24 hours of treatment, but had no effect on TNF production at 48 hours of treatment in RAW 264.7 macrophages in the presence or absence of EGFR kinase inhibition. Furthermore, compared to the TNF level in RAW 264.7 macrophages with intact EGFR kinase activity, inhibition of EGFR kinase activity decreased TNF production in macrophages at 8 and 18 hours, but increased TNF production at 24 hours of LPS/IFN-γ treatment (Figure 7).

These kinetic data suggest that inactivation of EGFR in macrophages enhances IL-10 production at the early stage (8 to 24 hours) but not at the later stage (48 hours) of LPS/IFN-γ treatment. IL-10 plays a role in inhibiting the production of proinflammatory cytokines in response to endotoxin- or IFN-γ stimulation (11, 12), suggesting that this transient increase in IL-10 production may lead to suppression of TNF production by inactivation of EGFR at the early stage of LPS/IFN-γ treatment (8 to 18 hours). These data are consistent with our in vivo result that the TNF levels decrease as IL-10 production increases in DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice (Figure 4).

Inhibition of EGFR kinase activity in macrophages enhances LPS-stimulated

NF-κB activation Cytokine gene expression is regulated by a balance between positive and negative signal transduction pathways. LPS engages TLR4 in macrophages and triggers downstream signaling through myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88)-dependent and -independent pathways, involving the activation of NF-κB and the p38, JNK, and ERK1/2 members of the MAPK family. However, mechanisms and signaling pathways that limit the magnitude of induction of these genes are poorly understood. We found that LPS stimulation induced EGFR activation in RAW 264.7 cells (Figure 8A).

Figure 8. The effects of blocking EGFR on LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation in macrophages.

RAW 264.7 macrophages were treated with LPS (1 μg/ml) for the indicated time periods in the presence or absence of an EGFR kinase inhibitor, AG1478 (300 nM). Total cellular lysates were collected for Western blot analysis of IκBα degradation. Anti-β-actin antibody was used as a protein loading control (A). The relative density was calculated by comparing the density of the IκBα band to the β-actin band of the same sample. The relative density of the control group was set as 1, and the relative density in other groups was compared to obtain the fold change (B). Nuclear proteins were collected from RAW 264.7 macrophages treated with LPS for 1 hour in the presence or absence of AG1478 for Western blot analysis of NF-κB p65 subunit. Ki67 antibody was used as a protein loading control. The relative density was calculated by comparing the density of the p65 band to the Ki67 band of the same sample The relative density of the LPS group was set as 1, and the relative density in other groups was compared to obtain the fold change, which is shown underneath the p65 blot (C). BMDMs isolated from NF-κB reporter mice were treated with LPS (200 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of AG1478 (300 nM) for 6 hours. Cellular lysates were collected for detecting luciferase activity using a standard assay. Luciferase activity was expressed as fold change compared to the control group (D). In B and D, * p < 0.05 compared to the control group, # p < 0.05 compared to the LPS group with the same time treatment. In C * p < 0.05 compared to the LPS group. Data in A and C are representative of 4 independent experiments. Data in B and D are quantified from 4 independent experiments.

Next, we tested the role of EGFR activation in regulating LPS-induced signaling pathways in macrophages. We detected the effects of EGFR inhibition on IκBα degradation, which leads to NF-κB activation, in RAW 264.7 macrophages treated with LPS for up to 6 hours. IκBα degradation occurred at 15 min of LPS treatment and IκBα levels returned to the untreated levels at 60 min in RAW 264.7 macrophages with EGFR activity. Under conditions of EGFR inhibition, IκBα degradation also occurred at 15 min of LPS treatment, but IκBα levels returned to untreated levels at 180 min. Thus, these data suggest that inhibition of EGFR stimulates extended but not persistent NF-κB activation (Figure 8A and B).

To further confirm the effect of EGFR inhibition on increasing LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation, nuclear proteins from RAW264.7 macrophages were collected for Western blot analysis of NF-κB p65 subunit nuclear translocation. EGFR inhibition promoted LPS-stimulated NF-κB p65 nuclear translocation (Figure 8C). In addition, Luciferase activity assays were performed to measure NF-κB transcriptional activity using BMDMs isolated from NF-κB reporter mice. LPS-stimulated NF-κB transcriptional activity was upregulated by EGFR inhibition (Figure 8D).

Statistical analysis of the fold change of the relative density suggested that EGFR inhibition does not affect LPS activation of p38, ERK1/2, and JNK in RAW 264.7 macrophages (Supplemental Figure 3).

This transient increase of LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation by inhibition of EGFR correlates with the finding that inhibition of EGFR increases IL-10 production at early stage of LPS/IFN-γ treatment, leading to decreased TNF production in RAW 264.5 cells (Figure 7). Thus, these data suggest that transactivation of EGFR decreases LPS activation of NF-κB, influencing cytokine production upon LPS treatment of macrophages.

Discussion

Studies have revealed diverse functions of macrophages in intestinal inflammation, with tissue damage caused by production of proinflammatory cytokines (7, 8), and protective effects mediated by factors that are immunosuppressive and/or aid in tissue repair (9, 38). In the present study, we demonstrate that EGFR in macrophages is activated by LPS treatment, in ulcerative colitis patients and during DSS-induced colitis in mice. Therefore, EGFR signaling may be involved in regulating macrophage functions. It has been reported that LPS transactivation of EGFR may involve release of EGFR ligands by intestinal epithelial cells (39) and bronchial epithelial cells (40). It has also been shown that macrophages express EGFR ligands such as EGF, induced in response to colony stimulating factor-1 (41). Thus, LPS transactivation of EGFR in macrophages may involve release of EGFR ligands by macrophages. Other cell types may contribute to EGFR ligand production during LPS stimulation in vivo as well.

Transactivation of EGFR in intestinal epithelial cells has shown cytoprotective effects (19). Indeed, EGFR in epithelial cells is protective in murine colitis models (23). However, our data suggest that deletion of EGFR in macrophages ameliorates colitis development and promotes recovery, which is associated with decreased levels of TNF and other proinflammatory cytokines during the late stage of colitis and during the recovery phase, due to upregulation of IL-10 production. Thus, the biological function of EGFR in colitis appears to be cell-specific.

LPS-activated TLR4 stimulates cytokine production via recruitment of MyD88 and other adapter proteins, leading to activation of the NF-κB pathway and members of the MAPK signaling pathway, including p38, JNK and ERB1/2 (42). We found that inhibition of EGFR increases the activation level and duration of LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation, which indicates that EGFR activation may suppress LPS-stimulated NF-κB signaling. Furthermore, the PI3K pathway has been reported to limit LPS activation of signaling pathways, including the NF-κB and MAPK pathways, and expression of inflammatory cytokines in human monocytic cells (43). Since PI3K is one of the EGFR targets, further studies are underway in our laboratory to elucidate the role of EGFR-regulated PI3K in the inhibition of LPS-stimulated NF-κB signaling pathways in macrophages. However, it is possible that there are other mechanisms underlying the effects of EGFR activation on TLR signaling. For example, regulation of dsRNA-activated TLR3 by EGFR involves binding of EGFR and Src sequentially to TLR3 and subsequent phosphorylation of the two tyrosine residues in the cytoplasmic domain of TLR3 induces recruitment of adaptor proteins and initiation of antiviral responses (44).

Our results further suggest that transactivation of EGFR decreases LPS activation of NF-κB, thus EGFR activation has an inhibitory role in the induction of pro- (TNF) and anti-inflammatory (IL-10) cytokines by LPS plus IFN-γ in macrophages. Based on data from Western blot analyses of IκBα degradation and Luciferase activity assays to evaluate NF-κB transcriptional activity, IFN-γ does not affect NF-κB activity in the presence or absence of EGFR kinase activity in RAW 264.7 macrophages (data not shown). However, EGFR inactivation increases LPS-stimulated NF-κB activation (Figure 8). Thus, enhancing LPS and IFN-γ-stimulated cytokine production by inhibition of EGFR kinase activity may occur by potentiating the effects of LPS on NF-κB activation. However, further investigations are needed to determine whether EGFR inactivation mediates priming of macrophages by IFN-γ via other signaling pathways.

It should be noted that, although EGFR inhibition in macrophages increases early TNF production in DSS-treated mice, sustained increases in IL-10 production as a result of EGFR inhibition in Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice exert a negative feedback to decrease production of TNF and other proinflammatory cytokines. Because IL-10 inhibits production of proinflammatory cytokines and promotes production of anti-inflammatory mediators in other immune cells, inhibition of IL-10 production by macrophages through EGFR activation may affect immune responses mediated by other cell types, which further regulate colitis.

TLR signaling in intestinal macrophages has been shown to promote epithelial cell regeneration. COX-2 is one of the genes involved in epithelial cell regeneration that are upregulated in LPS-stimulated macrophages and in intestinal macrophages from DSS-treated mice (9). Colonic macrophages isolated from Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice treated with DSS for 4 days followed by a 3-day recovery period showed increased levels of COX-2 mRNA expression, which correlated with increased intestinal epithelial cell proliferation rates in these animals. While apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells is a pathological factor for colitis, we were unable to observe alterations in intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis in DSS-treated Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice, compared with LysM-Cre mice (data not shown). Therefore, EGFR activation in macrophages may negatively regulate production of factors that regulate the regenerative response in intestinal epithelial cells during colitis.

In this study, we used an anti-mouse F4/80 antibody to purify colonic macrophages. To address the important issue regarding the purity of cells enriched using this anti-F4/80 antibody, we performed phenotypic characterization of these enriched cells using FITC-conjugated anti-CD11b and PE-conjugated anti-Siglec-F (a eosinophil cell marker) antibodies. Our data showed that under normal conditions, the percentage of this enriched cell population expressing Siglec-F is very low (Siglec-F+:1.31±0.37%, CD11b+Siglec-F+: 0.68±0.57%). These data are consistent with published results that resting mouse small intestinal eosinophils express CD11b, but not F4/80 (45). In DSS-induced colitis, the percentage of the enriched cell population expressing Siglec-F is significantly higher than that in the control group (Siglec-F+: 11.091±4.43%, CD11b+Siglec-F+: 5.79±2.31%). These data suggest that proinflammatory eosinophils express F4/80, as reported before that eosinophils express F4/80 in mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni (46). In addition, this evidence of increased colonic eosinophils in the DSS-treated mice has been observed in published paper (47). Although we found Siglec-F+ cells in the cells enriched from DSS-treated mice, macrophages are the major cell type in this cell population. Thus, the results from enriched cells (cytokine production profiles in Figures 4B and 6C) should predominantly represent functional changes in macrophages. Importantly, we have shown that PMN do not express EGFR (Figure 1A). Thus, the main contributing factor to the changes of cytokine expression levels in cells enriched from the colon of Egfrfl/flLysM-Cre mice should be from knockdown of EGFR in macrophages.

In summary, although EGFR has been well-studied for its role in promoting cell growth, few studies have investigated its immune regulatory functions. This study provides evidence that microbial products such as LPS activate EGFR in macrophages, which negatively regulates both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine production. During colitis, inhibition of IL-10 production by EGFR activation in macrophages may be involved in accelerating colitis and impairing disease recovery. Thus, these results provide important new information for understanding the mechanisms that regulate macrophage functions under physiological and pathological conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported by NIH grants R01DK081134 (F.Y.), R01DK056008 (D.B.P.), R01DK054993 (D.B.P.), P01CA116087 (F.Y., K.T.W., D.B.P.) National Key Scientific Research Project of China CB9333004 (X.R.), and core services performed through Vanderbilt University Medical Center’s Digestive Disease Research Center supported by NIH grant P30DK058404.

We thank Dr. Timothy S. Blackwell and Dr. Wei Han from Vanderbilt University Medical Center for providing BMDMs isolated from NF-κB reporter mice and for technical support with the Luciferase Assays.

Abbreviations

- DSS

Dextran sulfate sodium

- IBD

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

EGF receptor

- TNBS

2,6,4-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Platt AM, Mowat AM. Mucosal macrophages and the regulation of immune responses in the intestine. Immunol Lett. 2008;119:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDonald TT, Monteleone I, Fantini MC, Monteleone G. Regulation of homeostasis and inflammation in the intestine. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1768–1775. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cho JH, Brant SR. Recent insights into the genetics of inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1704–1712. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chassaing B, Darfeuille-Michaud A. The commensal microbiota and enteropathogens in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1720–1728. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abraham C, Medzhitov R. Interactions between the host innate immune system and microbes in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1729–1737. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marks DJ, Segal AW. Innate immunity in inflammatory bowel disease: a disease hypothesis. The Journal of pathology. 2008;214:260–266. doi: 10.1002/path.2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rugtveit J, Nilsen EM, Bakka A, Carlsen H, Brandtzaeg P, Scott H. Cytokine profiles differ in newly recruited and resident subsets of mucosal macrophages from inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1493–1505. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70030-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenk M, Bouchon A, Seibold F, Mueller C. TREM-1--expressing intestinal macrophages crucially amplify chronic inflammation in experimental colitis and inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3097–3106. doi: 10.1172/JCI30602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pull SL, Doherty JM, Mills JC, Gordon JI, Stappenbeck TS. Activated macrophages are an adaptive element of the colonic epithelial progenitor niche necessary for regenerative responses to injury. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2005;102:99–104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405979102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore KW, de Waal Malefyt R, Coffman RL, O’Garra A. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu Rev Immunol. 2001;19:683–765. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Waal Malefyt R, Abrams J, Bennett B, Figdor CG, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10(IL-10) inhibits cytokine synthesis by human monocytes: an autoregulatory role of IL-10 produced by monocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1991;174:1209–1220. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O’Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joyce DA, Gibbons DP, Green P, Steer JH, Feldmann M, Brennan FM. Two inhibitors of pro-inflammatory cytokine release, interleukin-10 and interleukin-4, have contrasting effects on release of soluble p75 tumor necrosis factor receptor by cultured monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:2699–2705. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Waal Malefyt R, Haanen J, Spits H, Roncarolo MG, te Velde A, Figdor C, Johnson K, Kastelein R, Yssel H, de Vries JE. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) and viral IL-10 strongly reduce antigen-specific human T cell proliferation by diminishing the antigen-presenting capacity of monocytes via downregulation of class II major histocompatibility complex expression. The Journal of experimental medicine. 1991;174:915–924. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cohen S, Carpenter G. Human epidermal growth factor: isolation and chemical and biological properties. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 1975;72:1317–1321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.4.1317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wright NA, Pike C, Elia G. Induction of a novel epidermal growth factor-secreting cell lineage by mucosal ulceration in human gastrointestinal stem cells. Nature (London) 1990;343:82–85. doi: 10.1038/343082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yarden Y. The EGFR family and its ligands in human cancer. signalling mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:S3–8. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yarden Y, Sliwkowski MX. Untangling the ErbB signalling network. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001;2:127–137. doi: 10.1038/35052073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yamaoka T, Yan F, Cao H, Hobbs SS, Dise RS, Tong W, Polk DB. Transactivation of EGF receptor and ErbB2 protects intestinal epithelial cells from TNF-induced apoptosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:11772–11777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801463105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yan F, Cao H, Cover TL, Washington MK, Shi Y, Liu L, Chaturvedi R, Peek RM, Jr, Wilson KT, Polk DB. Colon-specific delivery of a probiotic-derived soluble protein ameliorates intestinal inflammation in mice through an EGFR-dependent mechanism. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:2242–2253. doi: 10.1172/JCI44031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fukata M, Chen A, Vamadevan AS, Cohen J, Breglio K, Krishnareddy S, Hsu D, Xu R, Harpaz N, Dannenberg AJ, Subbaramaiah K, Cooper HS, Itzkowitz SH, Abreu MT. Toll-like receptor-4 promotes the development of colitis-associated colorectal tumors. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1869–1881. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha A, Nightingale J, West KP, Berlanga-Acosta J, Playford RJ. Epidermal growth factor enemas with oral mesalamine for mild-to-moderate left-sided ulcerative colitis or proctitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:350–357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dube PE, Yan F, Punit S, Girish N, McElroy SJ, Washington MK, Polk DB. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibits colitis-associated cancer in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2780–2792. doi: 10.1172/JCI62888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scholes AG, Hagan S, Hiscott P, Damato BE, Grierson I. Overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor restricted to macrophages in uveal melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:373–377. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lamb DJ, Modjtahedi H, Plant NJ, Ferns GA. EGF mediates monocyte chemotaxis and macrophage proliferation and EGF receptor is expressed in atherosclerotic plaques. Atherosclerosis. 2004;176:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuss IJ, Marth T, Neurath MF, Pearlstein GR, Jain A, Strober W. Anti-interleukin 12 treatment regulates apoptosis of Th1 T cells in experimental colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1078–1088. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70392-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neurath MF, Weigmann B, Finotto S, Glickman J, Nieuwenhuis E, Iijima H, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Mudter J, Galle PR, Bhan A, Autschbach F, Sullivan BM, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Blumberg RS. The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn’s disease. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2002;195:1129–1143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan F, Wang L, Shi Y, Cao H, Liu L, Washington MK, Chaturvedi R, Israel DA, Wang B, Peek RM, Jr, Wilson KT, Polk DB. Berberine promotes recovery of colitis and inhibits inflammatory responses in colonic macrophages and epithelial cells in DSS-treated mice. American journal of physiology. 2012;302:G504–514. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00312.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chaturvedi R, Asim M, Lewis ND, Algood HM, Cover TL, Kim PY, Wilson KT. L-arginine availability regulates inducible nitric oxide synthase-dependent host defense against Helicobacter pylori. Infection and immunity. 2007;75:4305–4315. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00578-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han W, Li H, Cai J, Gleaves LA, Polosukhin VV, Segal BH, Yull FE, Blackwell TS. NADPH oxidase limits lipopolysaccharide-induced lung inflammation and injury in mice through reduction-oxidation regulation of NF-kappaB activity. J Immunol. 2013;190:4786–4794. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liao HJ, Carpenter G. Cetuximab/C225-induced intracellular trafficking of epidermal growth factor receptor. Cancer research. 2009;69:6179–6183. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Egger B, Bajaj-Elliott M, MacDonald TT, Inglin R, Eysselein VE, Buchler MW. Characterisation of acute murine dextran sodium sulphate colitis: cytokine profile and dose dependency. Digestion. 2000;62:240–248. doi: 10.1159/000007822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kitajima S, Takuma S, Morimoto M. Changes in colonic mucosal permeability in mouse colitis induced with dextran sulfate sodium. Exp Anim. 1999;48:137–143. doi: 10.1538/expanim.48.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clausen BE, Burkhardt C, Reith W, Renkawitz R, Forster I. Conditional gene targeting in macrophages and granulocytes using LysMcre mice. Transgenic Res. 1999;8:265–277. doi: 10.1023/a:1008942828960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garside P. Cytokines in experimental colitis. Clinical and experimental immunology. 1999;118:337–339. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mosser DM. The many faces of macrophage activation. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2003;73:209–212. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0602325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rittirsch D, Flierl MA, Ward PA. Harmful molecular mechanisms in sepsis. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:776–787. doi: 10.1038/nri2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qualls JE, Kaplan AM, van Rooijen N, Cohen DA. Suppression of experimental colitis by intestinal mononuclear phagocytes. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2006;80:802–815. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu D, Fukata M, Hernandez YG, Sotolongo JP, Goo T, Maki J, Hayes LA, Ungaro RC, Chen A, Breglio KJ, Xu R, Abreu MT. Toll-like receptor 4 differentially regulates epidermal growth factor-related growth factors in response to intestinal mucosal injury. Lab Invest. 2010;90:1295–1305. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.2010.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koff JL, Shao MX, Ueki IF, Nadel JA. Multiple TLRs activate EGFR via a signaling cascade to produce innate immune responses in airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294:L1068–1075. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00025.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goswami S, Sahai E, Wyckoff JB, Cammer M, Cox D, Pixley FJ, Stanley ER, Segall JE, Condeelis JS. Macrophages promote the invasion of breast carcinoma cells via a colony-stimulating factor-1/epidermal growth factor paracrine loop. Cancer Res. 2005;65:5278–5283. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kawai T, Akira S. The role of pattern-recognition receptors in innate immunity: update on Toll-like receptors. Nature immunology. 2010;11:373–384. doi: 10.1038/ni.1863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guha M, Mackman N. The phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt pathway limits lipopolysaccharide activation of signaling pathways and expression of inflammatory mediators in human monocytic cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:32124–32132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203298200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yamashita M, Chattopadhyay S, Fensterl V, Saikia P, Wetzel JL, Sen GC. Epidermal growth factor receptor is essential for Toll-like receptor 3 signaling. Sci Signal. 2012;5:ra50. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carlens J, Wahl B, Ballmaier M, Bulfone-Paus S, Forster R, Pabst O. Common γ-chain-dependent signals confer selective survival of eosinophils in the murine small intestine. J Immunol. 2009;183:5600–5607. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0801581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGarry MP, Stewart CC. Murine eosinophil granulocytes bind the murine macrophage-monocyte specific monoclonal antibody F4/80. J Leuk Bioly. 1991;50:471–478. doi: 10.1002/jlb.50.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Waddell A, Ahrens R, Steinbrecher K, Donovan B, Rothenberg ME, Munitz A, Hogan SP. Colonic eosinophilic inflammation in experimental colitis is mediated by Ly6Chigh CCR2+ inflammatory monocyte/macrophage-derived CCL11. J Immunol. 2011;186:5993–6003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.