Abstract

Background and Aims

The objective of this report was to determine the prevalence of underlying nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Methods

Demographics, comorbidities, clinicopathologic characteristics, surgical treatments, and outcomes from patients who underwent resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma at one of eight hepatobiliary centers between 1991 and 2011 were reviewed.

Results

Of 181 patients who underwent resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, 31 (17.1 %) had underlying nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis were more likely obese (median body mass index, 30.0 vs. 26.0 kg/m2, p<0.001) and had higher rates of diabetes mellitus (38.7 vs. 22.0 %, p=0.05) and the metabolic syndrome (22.6 vs. 10.0 %, p=0.05) compared with those without nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Presence and severity of hepatic steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning were more common among nonalcoholic steatohepatitis patients (all p<0.001). Macrovascular (35.5 vs. 11.3 %, p=0.01) and any vascular (48.4 vs. 26.7 %, p=0.02) tumor invasion were more common among patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. There were no differences in recurrence-free (median, 17.0 versus 19.4 months, p=0.42) or overall (median, 31.5 versus 36.3 months, p=0.97) survival after surgical resection between patients with and without nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

Conclusions

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis affects up to 20 % of patients with resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma.

Keywords: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score

Introduction

Concomitant increases in the incidence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) may imply an association between these two diseases. NAFLD, which can encompass isolated steatosis, steatohepatitis, and/or progressive cirrhosis, is the most common chronic liver disease in developed societies (paralleling the obesity and metabolic syndrome epidemics) and is likely the leading cause of “cryptogenic cirrhosis”.1–6 Up to 50 % of patients with NAFLD will develop nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), cirrhosis, and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).1–3,7–11 The yearly incidences of HCC and ICC have consistently increased over the past 40 years. These cancers now have the second highest annual percent rise in incidence since 2000.12,13 The development of HCC, risk factors for hepatocyte carcinogenesis, and long-term outcomes after curative therapy of HCC in the setting of NASH have been well described.5,7,11,14–22 Far less is known regarding the association of ICC and NASH. Results of preliminary studies exploring relationships between NASH and ICC are difficult to interpret due to (1) absence of histopathologic confirmation of NASH in the underlying liver, (2) inclusion of all patients with ICC regardless of resectability or stage, (3) and lack of tumor characteristics or long-term outcome evaluation.5–23 Recently, our group used an international multi-institutional database of patients who underwent resection of ICC to identify prognostic factors of long-term survival after surgical resection.24 The objective of the current report was to utilize this database to determine the prevalence of underlying NASH in patients with resectable ICC and assess the influence of NASH on long-term outcomes after surgical extirpation.

Patients and Methods

One hundred eighty-one patients who underwent surgical resection of histologically confirmed ICC with corresponding histopathologic examination of the underlying liver between January 1991 and June 2011 were identified from a previously described international multi-institutional database.24 Patients underwent hepatic resection at one of the following institutions: Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA; University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany; Dan Setlacec Center of General Surgery Diseases and Liver Transplantation, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania; Curry Cabral Hospital, Lisbon, Portugal; Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan, Italy; Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium; and Hopitaux Universitaires de Geneve, Geneva, Switzerland. Patients who underwent R2 resection (positive gross margin after partial hepatectomy) or those with extrahepatic metastatic disease at the time of hepatic resection were not included in this study. Patients who did not have pathological slides available for re-review were also excluded. The institutional review board from each institution approved this study. Only patients who received initial treatment for ICC at the respective hepatobiliary center were included.

Data Collection

Patient demographics, comorbidities, clinicopathologic tumor characteristics, surgical treatments, underlying liver histopathology, and long-term outcomes were recorded. Criteria for the metabolic syndrome were extrapolated from international guidelines25,26 and included any three of the following: body mass index (BMI) greater than 28.8 kg/m2 (validated as a replacement for elevated waist circumference in men and women)27 and documentation of or medical treatment for dyslipidemia, hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, and/or diabetes mellitus. While precise alcohol consumption was not able to be accurately measured in this multicenter study, no patient exceeded the consumption threshold for consideration of alcoholic steatohepatitis as noted by consensus guidelines.28 The most recent preoperative laboratory values were reported. Surgical resection was classified using Brisbane terminology as less than hemihepatectomy, hemihepatectomy, and greater than hemihepatectomy.29

Resection margins; nodal status; tumor size and number; vascular, perineural, and biliary invasion; and underlying liver disease were all determined from final pathologic assessment. The American Joint Committee on Cancer 6th edition staging system was used to describe T stages.30 The underlying liver pathology reported in this study was based on a dedicated re-review of the pathological slides of each resection specimen by an experienced hepatobiliary pathologist at each respective center. Steatosis grade, lobular inflammation, hepatocyte ballooning, extent of fibrosis, and portal inflammation were described according to Kleiner et al.31 and Brunt et al.32 Instead of the precise number of foci per high power field, lobular inflammation was reported as “none,” “rare/spotty,” “mild,” or “moderate/heavy.” Each of these terms were then coded in increasing severity from 0 to 3 to calculate the NAFLD activity score (NAS).31 Pathologist diagnosis of NASH was used to categorize patients and was reported independently of NAS.33,34 Grades of steatohepatitis as defined by consensus guidelines28 were not differentiated in this study. Patients with borderline and definite steatohepatitis28,35 were categorized in the same NASH group. Patients with NASH and concomitant other chronic liver diseases were categorized in the NASH group.

Statistical Analyses

Summary statistics were presented as percentages for nominal and ordinal values and as median (25th–75th percentiles) for continuous values, respectively. Comparisons of discrete and continuous variables were performed with the χ2 and Mann–Whitney U tests, respectively. Overall survival time was calculated from date of surgery to date of last follow-up or death. Cumulative event rates were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.36 Significance levels were set at p≤0.05; all tests were two-sided. All analyses were performed using SAS software package (Version 9.3, SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Of the 181 patients in this cohort, 31 (17.1 %) had definite or borderline NASH in the underlying liver. Sixteen (8.8 %) patients had a pathologic diagnosis of definitive NASH and 15 (8.3 %) had borderline NASH. Of the 31 patients with definitive or borderline NASH, one and two had concomitant hepatitis B and C viral infections, respectively. Of the 150 patients without NASH, six patients had hepatitis B viral infection, seven had hepatitis C viral infection, three had primary sclerosing cholangitis, and one each had hepatitis A infection, hereditary hemochromatosis, and unilobar Caroli’s disease. Seven patients in the non-NASH group had bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis without clear etiology. Only two of these patients had diabetes mellitus, none had a BMI greater than 28.8 kg/m2, and one had the metabolic syndrome. There was no difference in the prevalence of NASH among European compared with US centers (16.9 vs. 17.2 %, p=0.96).

Demographics, Comorbidities, and Surgical Treatments

Compared with patients without NASH, patients with NASH were less likely to be Caucasian and were more likely to be obese, have diabetes mellitus, and the metabolic syndrome (Table 1). In US hospitals, nine (81.8 %) patients with NASH were Caucasian compared to 50 (92.6 %) patients without NASH. In non-US hospitals, 18 (90.0 %) patients with NASH were Caucasian compared to 95 (99.0 %) patients without NASH. None of these comparison differences reached statistical significance. There were no significant differences in barometers of synthetic liver function (preoperative albumin and bilirubin levels), preoperative CA 19–9 levels, bilateral tumor distribution, or extent of hepatic resection required to achieve complete surgical extirpation.

Table 1.

Patient demographics, comorbidities, preoperative laboratory values, and surgical treatments for all patients and stratified by the presence or absence of underlying NASH

| All patients | NASH | Non-NASH | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n=181) | (n=31) | (n=150) | ||

| Age (years) | 64 (56–71) | 63 (56–71) | 64 (56–71) | 0.58 |

| Female gender | 97 (53.6 %) | 16 (51.6 %) | 81 (54.0 %) | 0.80 |

| Caucasian ethnicitya | 172 (95.0 %) | 27 (87.1 %) | 145 (96.7 %) | 0.03 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 45 (24.9 %) | 12 (38.7 %) | 33 (22.0 %) | 0.05 |

| Hypertension | 77 (42.5 %) | 12 (38.7 %) | 65 (43.3 %) | 0.64 |

| Dyslipidemia | 44 (24.3 %) | 10 (32.3 %) | 34 (22.7 %) | 0.26 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 26.3 (23.5–28.4) | 30.0 (28.2–31.8) | 26.0 (23.3–27.7) | <0.001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 22 (12.2 %) | 7 (22.6 %) | 15 (10.0 %) | 0.05 |

| Albumin (mg/dL) | 4.2 (3.8–4.5) | 4.2 (3.7–4.6) | 4.2 (3.8–4.5) | 0.81 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 0.6 (0.6–1.1) | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 0.31 |

| CA 19–9 (U/mL) | 74.0 (18.5–222.5) | 26.5 (8.5–198.0) | 77.5 (22.4–231.5) | 0.58 |

| Bilobar liver tumor involvement | 50 (27.6 %) | 10 (32.3 %) | 40 (26.7 %) | 0.53 |

| Extent of surgical resection | ||||

| Less than hemihepatectomy | 59 (32.6 %) | 12 (38.7 %) | 47 (31.3 %) | 0.50 |

| Hemihepatectomy | 72 (39.8 %) | 13 (41.9 %) | 59 (39.3 %) | |

| Extended hepatectomy | 50 (27.6 %) | 6 (19.4 %) | 44 (29.3 %) |

Discrete variable are reported with associated percentages, continuous variables are reported as median (25–75th percentile)

Non-Caucasian ethnicity includes black, Hispanic, and Asian-Pacific Islander

Tumor and Underlying Liver Histopathology

On final pathologic examination, there were no significant differences in primary tumor multiplicity, size, differentiation, or AJCC 6th edition T stage30 (Table 2). While there were no significant differences in perineural or biliary invasion, any vascular and macrovascular tumor invasion were more common among NASH patients versus patients without NASH. Macrovascular (35.5 vs. 11.3 %, p=0.01) and any vascular (48.4 vs. 26.7 %, p=0.02) tumor invasion were more common among patients with NASH. Hepatic steatosis, lobular inflammation, and hepatocyte ballooning were all more extensive in NASH specimens compared to specimens without NASH. Correspondingly, the median NAS31 was greater in NASH specimens. While there were no significant differences in severe fibrosis, perisinusoidal with or without periportal fibrosis was more common among NASH specimens. Portal inflammation was also more common among NASH specimens.

Table 2.

Tumor and underlying liver histopathology for all patients and stratified by the presence or absence of underlying NASH

| All patients (n=181) | NASH (n=31) | Non-NASH (n=150) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor pathology | ||||

| Primary tumor multiplicity | 96 (53.0 %) | 16 (51.6 %) | 80 (53.3 %) | 0.86 |

| Median size of largest tumor (cm) | 6.8 (4.0–9.5) | 7.0 (4.3–10.0) | 6.4 (4.0–9.5) | 0.67 |

| Vascular invasion | ||||

| Macrovascular | 28 (15.5 %) | 11 (35.5 %) | 17 (11.3 %) | 0.01 |

| Microvascular | 27 (14.9 %) | 4 (12.9 %) | 27 (15.3 %) | |

| AJCC 6th edition T stage30 | ||||

| 1 | 85 (47.0 %) | 15 (48.4 %) | 70 (46.7 %) | 0.15 |

| 2 | 45 (24.9 %) | 4 (12.9 %) | 41 (27.3 %) | |

| 3 | 46 (25.4 %) | 12 (38.7 %) | 34 (22.7 %) | |

| 4 | 5 (2.8 %) | 0 | 5 (3.3 %) | |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Well | 18 (9.9 %) | 4 (12.9 %) | 14 (9.3 %) | 0.76 |

| Moderate | 115 (63.5 %) | 20 (64.5 %) | 95 (63.3 %) | |

| Poor | 48 (26.5 %) | 7 (22.6 %) | 41 (27.3 %) | |

| Invasion | ||||

| Vascular | 55 (30.4 %) | 15 (48.4 %) | 40 (26.7 %) | 0.02 |

| Perineural | 20 (11.1 %) | 2 (6.5 %) | 18 (12.0 %) | 0.37 |

| Biliary | 26 (14.4 %) | 7 (22.6 %) | 19 (12.7 %) | 0.15 |

| Resection margin | ||||

| R 0 | 147 (81.2 %) | 25 (80.7 %) | 122 (81.3 %) | 0.93 |

| R 1 | 34 (18.8 %) | 6 (19.4 %) | 28 (18.7 %) | |

| Positive nodal disease | 23 (12.7 %) | 6 (19.4 %) | 17 (11.3 %) | 0.47 |

| Number of lymph nodes examined | 1 (0–3) | 1 (0–4) | 0.5 (0–3) | 0.24 |

| Underlying liver pathology | ||||

| Steatosis | ||||

| Less than 5 % | 79 (43.7 %) | 0 | 79 (52.7 %) | <0.001 |

| 5–33 % | 76 (42.0 %) | 14 (45.2 %) | 62 (41.3 %) | |

| 34–66 % | 14 (7.7 %) | 7 (22.6 %) | 7 (4.7 %) | |

| Greater than 66 % | 12 (6.6 %) | 10 (32.3 %) | 2 (1.3 %) | |

| Lobular inflammation | ||||

| None | 114 (63.0 %) | 8 (25.8 %) | 106 (70.7 %) | <0.001 |

| Spotty (<2 foci/200× field) | 54 (29.8 %) | 15 (48.4 %) | 39 (26.0 %) | |

| Mild (2–4 foci/200× field) | 12 (6.6 %) | 8 (25.8 %) | 4 (2.7 %) | |

| Mod/heavy (>4 foci/200× field) | 1 (0.6 %) | 0 | 1 (0.7 %) | |

| Hepatocyte ballooning | ||||

| None | 156 (86.2 %) | 11 (35.5 %) | 145 (96.7 %) | <0.001 |

| Few | 19 (10.5 %) | 16 (51.6 %) | 3 (2.0 %) | |

| Many | 6 (3.3 %) | 4 (12.9 %) | 2 (1.3 %) | |

| NAFLD activity score [31] | 1 (0–2) | 4 (3–5) | 1 (0–1) | <0.001 |

| NAFLD activity score [31]≥5 | 12 (6.6 %) | 11 (35.5 %) | 1 (0.7 %) | <0.001 |

| Hepatic fibrosis | ||||

| None | 99 (54.7 %) | 6 (19.4 %) | 93 (62.0 %) | <0.001 |

| Perisinusoidal or periportal | 53 (29.3 %) | 13 (41.9 %) | 40 (26.7 %) | |

| Perisinusoidal and periportal | 13 (7.2 %) | 8 (25.8 %) | 5 (3.3 %) | |

| Bridging | 13 (7.2 %) | 3 (9.7 %) | 10 (6.7 %) | |

| Cirrhosis | 3 (1.2 %) | 1 (3.2 %) | 2 (1.3 %) | |

| Portal inflammation | ||||

| None | 87 (48.1 %) | 8 (25.8 %) | 79 (52.7 %) | 0.02 |

| Mild | 73 (40.3 %) | 19 (61.3 %) | 54 (36.0 %) | |

| More than mild | 21 (11.6 %) | 4 (12.9 %) | 17 (11.3 %) | |

| Hepatitis B viral infection | 7 (3.9 %) | 1 (3.2 %) | 6 (4.0 %) | 0.84 |

| Hepatitis C viral infection | 9 (5.0 %) | 2 (6.5 %) | 7 (4.7 %) | 0.67 |

Discrete variable are reported with associated percentages, continuous variables are reported as median (25th–75th percentile)

Long-Term Outcomes

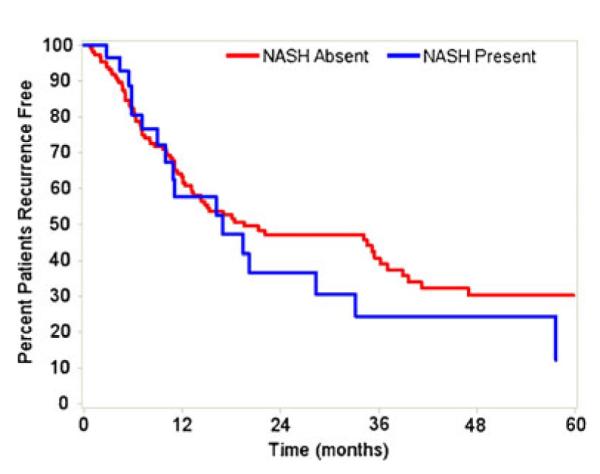

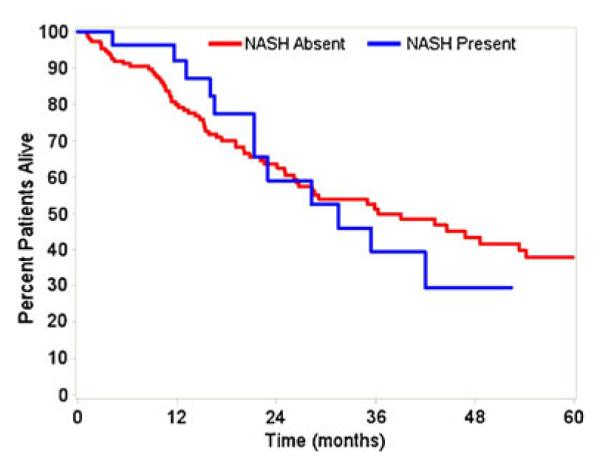

Median follow-up for living patients was 19.1 (10.3–35.5) months. There were no differences in recurrence-free or overall survival after hepatic resection of ICC between patients with and without underlying NASH. The median recurrence-free survival after resection was 17.0 (95 % CI 9.0–33.2) months among NASH patients versus 19.4 (95 % CI 13.3–38.9)months among patients without NASH (p=0.42; Fig. 1). The median overall survival after resection was 31.5 (95 % CI 21.3–60.8)months among NASH patients versus 36.3 (95 % CI 26.1–54.2)months among patients without NASH (p= 0.97; Fig. 2). Patients with definitive NASH did not have lower recurrence-free (median, 17.0 vs. 19.6 months, p=0.51) or overall (median, 21.4 vs. 36.3 months, p=0.24) survival compared to the rest of the study cohort.

Fig. 1.

Recurrence-free survival after hepatic resection stratified by presence of NASH. No difference in recurrence-free survival (p=0.42)

Fig. 2.

Overall survival after hepatic resection stratified by presence of NASH. No difference in overall survival (p=0.97)

Discussion

While the incidence of ICC is increasing in the USA12,13, the reason for this rise remains unclear. Surgical resection is the only potential curative therapeutic option for ICC and long-term survival is possible in appropriately selected patients.24 Previous studies have identified prognostic factors associated with overall survival, but few—if any—have focused on the potential effects of NASH on long-term outcomes. Data on the prevalence of NASH among patients with ICC and its potential effects on long-term outcomes are relevant to clinical management because obesity and NASH are dramatically increasing throughout the USA. The current study defines the prevalence of NASH among patients with resectable ICC derived from a large, multinational, multi-institutional cohort. We found that up to 20 % of patients with resectable ICC had evidence of NASH. While primary tumor vascular invasion was more common among patients with underlying NASH, the presence of NASH had no impact on recurrence-free or overall survival after resection of ICC.

The prevalence of NASH in our study was considerably higher than other series that examined patients with ICC regardless of stage and resectability.5 For example, analysis of the linked Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results–Medicare database demonstrated that “chronic non-alcoholic liver disease” was present in only 5 of 535 (0.9 %) of patients with ICC.37 While considerably lower than the prevalence reported in our study, the authors did note that the prevalence was higher among ICC patients compared with cancer-free controls (0.3 %, p=0.03).37 A study of the Danish cancer registry identified 849 patients with histologically confirmed ICC over a 14-year time span. In comparison to age- and sex-matched controls, ICC patients were more likely to have “unspecified cirrhosis”23—which may have included cases of “burnt out” steatohepatitis.35,38 In a separate study, Welzel et al. reported that patients with ICC were more likely to have each component of and the overall diagnosis of the metabolic syndrome compared with matched controls—causing the authors to suggest that NAFLD may be a cause of “idiopathic” ICC.39 In contrast to previous registry-based, nationwide series, the current study is the first to examine specifically the prevalence of NASH among patients with resectable ICC. One notable strength of the current study was that all pathological determinations of NASH were made by experienced hepatobiliary pathologists at high volume centers. This may explain, to a large degree, the higher prevalence of NASH in the current study compared with previous population-based data, which are known to be less accurate in characterizing more subtle histological features.33,35 In addition, the significant differences in patient comorbidities, presence and severity of each underlying liver histopathology (including characteristic perisinusoidal fibrosis patterns31), and aggregate NAS31 between patients with and without NASH (Table 1) strongly corroborate the accuracy of the pathological diagnosis of NASH in our study. As such, the current study provides a more accurate assessment of the prevalence of NASH among patients with resectable ICC compared with previous reports.

The influence of NASH on intrahepatic bile duct carcinogenesis and long-term outcomes after surgical resection of ICC is unclear. Due to the rising prevalence of NAFLD in the population at large, hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis is more commonly found in resection specimens for benign and malignant conditions.40 Previous studies note that NASH specifically promotes HCC carcinogenesis, both through the progression of NASH to cirrhosis and through mechanisms independent of severe fibrosis.14,22,41 The impact of NASH on ICC carcinogenesis has not nearly been as well studied or defined. As such, it remains unclear as to whether the association between NASH and ICC is causal or simply coincidental due to the rising prevalence of NAFLD. While the current study was not designed to elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of NASH relative to ICC, we did note some interesting associations. Specifically, patients with NASH were much more likely to have tumors associated with vascular invasion, but there were no differences in T stage or nodal disease between NASH and non-NASH groups (Table 2). More importantly, the presence of NASH did not affect recurrence-free or overall survival after hepatic resection of ICC (Figs. 1 and 2).

Several limitations to this study should be considered. Imperfect inter-rater agreement on the presence and magnitude of certain histologic features mean that the assignment of a NASH diagnosis is not absolute.31 All participating institutions in this report are tertiary hepatobiliary centers with well-experienced specialized surgeons and pathologists. Thus, the degree of interrater variability in the diagnosis of NASH was likely not substantial. Sampling variability and adjacent tumor effects may have influenced histologic interpretations. Absence of definitive pathologic criteria for ICC in the early periods of this study, limited number of patients at each participating institution, and inclusion of both borderline and definitive steatohepatitis in the NASH group hinder the accurate determination of the prevalence of underlying NASH in patients with resectable ICC. In addition, the results of our study may not be applicable to patients with more advanced underlying hepatic fibrosis or disease stages, since many of these patients were excluded from surgical consideration and therefore were not part of the current cohort. Similarly, we cannot determine the incidence of NASH among all patients with ICC or if the preoperative suspicion of background NASH-altered decisions to perform partial hepatectomy since patients with unresectable ICC or who underwent an R2 resection were not included in this study cohort. Postoperative outcomes (such as length of hospital stay, postoperative morbidity, and postoperative mortality) were also not available in this multi-institutional database. Thus, we cannot determine if background NASH affected postoperative outcomes after resection of ICC. Though our series comprises one of the largest cohorts of patients with resectable ICC, the relatively small number of patients in each group may have masked further differences in presentation, clinicopathologic tumor characteristics, and long-term outcomes. Although present at a higher rate than in non-NASH patients, vascular tumor invasion was present in 16 patients with NASH, less than half of the NASH cohort. This small number of patients likely explains why patients with NASH had similar long-term survival outcomes after tumor resection compared to patients without NASH, despite the well-recognized deleterious effects of vascular invasion in ICC.26 Information regarding neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment was not included in our database. However, we suspect that only a small portion of the study cohort received neoadjuvant chemotherapy as this treatment is not routinely administered for ICC. Nonetheless, we are not able to exclude the possible contribution of neoadjuvant chemotherapy to background steatohepatitis. We also cannot accurately account for the presence of other background liver diseases (such as hepatitis C viral infection, genotype 3), which may cause hepatic steatosis independent of NASH.

In summary, NASH is more prevalent among patients with resectable ICC than previously reported in population-based studies. In fact, up to 20 % of patients undergoing resection of ICC have underlying NASH. In addition, while many of the clinicopathological features were similar among patients with and without NASH, primary tumor vascular invasion is more common in the setting of NASH. However, recurrence-free and overall survival after hepatic resection of ICC is comparable in NASH versus non-NASH patients.

Abbreviations

- NASH

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

- ICC

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- BMI

Body mass index

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- NAFLD

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- NAS

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease activity score

Contributor Information

Srinevas K. Reddy, Department of Surgery, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD, USA

Omar Hyder, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Blalock 688 600 N. Wolfe Street Baltimore, MD 21287 Baltimore, USA.

J. Wallis Marsh, Department of Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA.

Georgios C. Sotiropoulos, Department of Surgery, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany

Andreas Paul, Department of Surgery, University Hospital Essen, Essen, Germany.

Sorin Alexandrescu, Dan Setlacec Center of General Surgery and Liver Transplantation, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania.

Hugo Marques, Department of Surgery, Curry Cabral Hospital, Lisbon, Portugal.

Carlo Pulitano, Department of Surgery, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan, Italy.

Eduardo Barroso, Department of Surgery, Curry Cabral Hospital, Lisbon, Portugal.

Luca Aldrighetti, Department of Surgery, Ospedale San Raffaele, Milan, Italy.

David A. Geller, Department of Surgery, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

Christine Sempoux, Department of Pathology, Cliniques Universitaires Saint-Luc, Brussels, Belgium.

Vlad Herlea, Dan Setlacec Center of General Surgery and Liver Transplantation, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania.

Irinel Popescu, Dan Setlacec Center of General Surgery and Liver Transplantation, Fundeni Clinical Institute, Bucharest, Romania.

Robert Anders, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Blalock 688 600 N. Wolfe Street Baltimore, MD 21287 Baltimore, USA.

Laura Rubbia-Brandt, Department of Pathology, Hopitaux Universitaires de Geneve, Geneva, Switzerland.

Jean-Francois Gigot, Department of Pathology, Hopitaux Universitaires de Geneve, Geneva, Switzerland.

Giles Mentha, Department of Pathology, Hopitaux Universitaires de Geneve, Geneva, Switzerland.

Timothy M. Pawlik, Department of Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Blalock 688 600 N. Wolfe Street Baltimore, MD 21287 Baltimore, USA

References

- 1.Hashimoto E, Tokushige K. Prevalence, gender, ethnic variations, and prognosis of NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2011;46(Suppl):63–9. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0311-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pascale A, Pais R, Ratziu V. An overview of nonalcoholic steato-hepatitis: past, present, and future directions. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2010;19:415–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Younossi AM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, et al. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1998 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:524–30. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michitaka K, Nishiguchi S, Aoyagi Y, Hiasa Y, Tokumoto Y, Onji M, Japan Etiology of Liver Cirrhosis Study Group Etiology of liver cirrhosis in Japan: a nationwide survey. J Gastoenterol. 2010;45:86–94. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0128-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhala N, Angulo P, van der Poorten D, Lee E, Hui JM, Saracco G, et al. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis: an international collaborative study. Hepatology. 2011;54:1208–16. doi: 10.1002/hep.24491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Starley BQ, Calcagno CJ, Harrison SA. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma: a weighty connection. Hepatology. 2010;51:1820–32. doi: 10.1002/hep.23594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page JM, Harrison SA. NASH and HCC. Clin Liver Dis. 2009;13:631–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen JC, Horton JD, Hobbs HH. Human fatty liver disease: old questions and new insights. Science. 2011;332:1519–23. doi: 10.1126/science.1204265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aly EZ, Kleiner DE. Update on fatty liver disease and steatohepatitis. Adv Anat Pathol. 2011;18:294–300. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e318220f59b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Argo CK, Northup PG, Al-Osaimi AMS, Caldwell SH. Systemic review of risk factors for fibrosis progression in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2009;51:371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reddy SK, Steel JL, Chen HW, DeMateo DJ, Cardinal J, Behari J, et al. Outcomes of curative treatment for hepatocellular caner in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis versus hepatitis C and alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2012;55:1809–19. doi: 10.1002/hep.25536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2000 SEER incidence and US mortality rates and trends for the top 15 cancer sites by race/ethnicity. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops09/results_merged/topic_topfifteen.pdf.

- 13.SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2000 CSR sections—liver and bile duct. http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2009_pops2009/results_merged/sect_14_liver_bile.pdf.

- 14.Hashimoto E, Yatsuji S, Tobari M, Taniai M, Torii N, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(Suppl XIX):89–95. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2262-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stickel F, Hellerbrand C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a risk factor for hepatocellular carcinoma: mechanisms and implications. Gut. 2010;29:1303–7. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.199661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ascha M, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1972–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokushige K, Hasimoto E, Yatsuji S, Tobari M, Taniai M, Torii N, Shiratori K. Prospective study of hepatocellular carcinoma in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in comparison with hepatocellular carcinoma caused by chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol. 2010;45:960–7. doi: 10.1007/s00535-010-0237-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kawada N, Imanaka K, Kawaguchi T, Tamai C, Ishihara R, Matsunaga T, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma arising from noncirrhotic alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1190–4. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ratziu V, Bonyhay L, Di Martino V, Charlotte F, Cavallaro L, Sayegh-Tainturier MH, et al. Survival, liver failure, and hepatocellular carcinoma in obesity-related cryptogenic cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2002;35:1485–93. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bugianesi E, Leone N, Vanni E, Marchesini G, Brunello F, Carucci P, et al. Expanding the natural history of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: from cryptogenic cirrhosis to hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:134–40. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.34168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yasui K, Hashimoto E, Komorizono Y, Koike K, Arii S, Imai Y, et al. Characteristics of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis who develop hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:428–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoshioka Y, Hashimoto E, Yatsuji S, Kaneda H, Taniai M, Tokushige K, Shiratori K. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and burnt-out NASH. J Gastroenterol. 2004;39:1215–8. doi: 10.1007/s00535-004-1475-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Welzel TM, Mellemkjaer L, Gloria G, Sakoda LC, Hsing AW, El Ghormli L, et al. Risk factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in a low-risk population: A nationwide case–control study. Int J Cancer. 2006;120:638–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Jong MC, Nathan H, Sotiropoulos GC, Paul A, Alexandrescu S, Marques H, et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis of prognostic factors and lymph node assessment. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3140–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.6519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eckel RH, Alberti KGMM, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ. The metabolic syndrome. Lancet. 2010;375:181–3. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61794-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberti KGMM, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato KA, Fruchart JC, et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ascha MS, Hanounch IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2010;51:1972–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.23527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Kowdley KV, Chalsani N, Lavine JE, et al. Endpoints and clinical trial design for nonalcoholic steatohepatits. Hepatology. 2011;54:344–53. doi: 10.1002/hep.24376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Strasberg SM. Nomenclature of hepatic anatomy and resections: a review of the Brisbane 2000 system. J Hepatobiliary and Pancreat Surg. 2005;12:351–5. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-0999-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, Fritz A. American Joint Committee on Cancer: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 6th ed Springer; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM, Van Natta M, Behling C, Contos MJ, Cummings OW, et al. Design and validation of a histological scoring system for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2005;41:1313–21. doi: 10.1002/hep.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Belt P, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, NASH Clinical Research Network (CRN) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) activity score and the histopathologic diagnosis in NAFLD: distinct clinicopathologic meanings. Hepatology. 2011;53:810–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.24127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Wilson LA, Unalp A, Behling CE, Lavine JE, et al. Portal chronic inflammation in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): a histologic marker of advanced NAFLD—clinicopatho-logic correlations from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatology. 2009;49:809–20. doi: 10.1002/hep.22724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, Diehl AM, Brunt EM, Cusi K, et al. The diagnosis and management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, American College of Gastroenterology, and the American Gastroenterological Association. Hepatology. 2012;55:2005–23. doi: 10.1002/hep.25762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kleiner DE, Brunt EM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: pathologic patterns and biopsy evaluation in clinical research. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:3–13. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:457–81. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Welzel TM, Graubard BI, El-Serag HB, Shaib YH, Hsing AW, Davila JA, McGlynn KA. Risk factors for intra- and extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a population based case–control study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1221–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lefkowitch JH, Morawski JL. Late nonalcoholic fatty liver disease with cirrhosis: a pathologic case of lost or mistaken identity. Semin Liver Dis. 2012;32:92–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1306429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welzel TM, Graubard BI, Zeuzem S, El-Serag HB, Davila JA, McGlynn KA. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of primary liver cancer in the United States: a study in the SEER-Medicare Database. Hepatology. 2011;54:463–71. doi: 10.1002/hep.24397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Reddy SK, Marsh JW, Varley PR, Mock BK, Chopra KB, et al. Underlying steatohepatitis, but not simple hepatic steatosis, increases morbidity after liver resection: a case–control study. Hepatology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/hep.25935. doi:10/1002/hep.25935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paradis V, Zalinski S, Chelbi E, Guedj N, Degos F, Vilgrain V, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with metabolic syndrome often develop without significant liver fibrosis: a pathological analysis. Hepatology. 2009;49:851–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.22734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]