Abstract

Involvement of the growth hormone (GH)/insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-I) axis in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy (DN) is strongly suggested by studies investigating the impact of GH excess and deficiency on renal structure and function. GH excess in both the human (acromegaly) and in transgenic animal models is characterized by significant structural and functional changes in the kidney. In the human a direct relationship has been noted between the activity of the GH/IGF-1 axis and renal hypertrophy, microalbuminuria, and glomerulosclerosis. Conversely, states of GH deficiency or deficiency or inhibition of GH receptor (GHR) activity confer a protective effect against DM nephropathy. The glomerular podocyte plays a central and critical role in the structural and functional integrity of the glomerular filtration barrier and maintenance of normal renal function. Recent studies have revealed that the glomerular podocyte is a target of GH action and that GH’s actions on the podocyte could be detrimental to the structure and function of the podocyte. These results provide a novel mechanism for GH’s role in the pathogenesis of DN and offer the possibility of targeting the GH/IGF-1 axis for the prevention and treatment of DN.

Keywords: growth hormone, podocyte, diabetic nephropathy, review

Introduction

Growth hormone (GH) is a 191 amino acid polypeptide secreted from the anterior pituitary gland under the control of hypothalamic factors GHRH and somatostatin. Pituitary GH is essential for postnatal growth in mammals. In addition to growth, GH affects the metabolism of fat, protein, and carbohydrate [1]. At the tissue level, these pleiotropic actions of GH result from the interaction of GH with a specific cell surface receptor, the GH receptor (GHR). In most species, including the human, the extracellular portion of the GHR is cleaved and circulates as GH binding protein (GHBP). The precise biological role of GHBP is unclear. The association of GH with GHBP prolongs the half-life of GH and the GHBP-GH complex could serve as a reservoir for GH. On the contrary GHBP can also associate with GHR to form non-functional heterodimers and thus compete with GH for binding to GHR [2]. The binding of GH induces conformational change in the GHR resulting in activation of several key post-receptor signaling cascades including Janus kinase 2 (JAK2), signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) proteins, and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-K). Whereas the GHR is ubiquitously expressed, the role and effects of GH have been most intensely investigated in organs and tissues such as liver, bone, muscle and adipocytes in which GHR expression is significant and are thus considered canonical targets of GH action. However, recent reports have highlighted biological effects and physiological relevance of GH action in non-canonical targets such as the macrophage [3], blastocyst [4], colonic epithelial cells [5], cardiomyocytes [6] and neurons [7] and the glomerular podocyte [8]. GH exerts its actions both by its direct effect on target organs and by stimulating the production of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). The classic endocrine effect of pituitary GH is the induction of IGF-1 synthesis in several organs through activation of GHR. In turn, circulating levels of IGF-1 exert negative feed-back loop control on pituitary GH secretion. Levels of free IGFs in a system are determined by rates of IGF production, IGF clearance, and degree of affinity to the IGF binding proteins (IGFBPs) [9]. IGF-1 circulates as a ternary complex with IGFBP-3 and the acid labile subunit (ALS) protein. In addition to prolonging the half-life of IGF-1 in circulation, IGFBPs also alter IGF-1 bioavailability at cellular level where in a contextual manner IGFBPs can either stimulate or inhibit IGF-1 action.

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is the most common microvascular chronic complication of diabetes mellitus (DM) and develops in 20–40% of Type 1 and Type 2 DM patients [10]. Worldwide, DN accounts for approximately one-third of all new cases of end stage renal disease (ESRD). In the US, DN is the most common cause of ESRD accounting for approximately 54% of new cases of ESRD [10]. DN is characterized by specific renal morphological and functional alterations [11]. Prominent early renal changes in DM include glomerular hyperfiltration, renal hypertrophy, and microalbuminuria. With advancement of the renal involvement in DM there is significant decrement in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and increasing loss of protein into the urine characterized as macroalbuminuria often progressing to ESRD.

Growth Hormone and Renal Function

Several components of the GH/IGF-1 axis, including GHR, IGF-1, IGF-1 receptor and IGFBPs are expressed in the kidney with precise spatial distribution across various anatomical and functional segments of the nephron [12]. Thus GHR is expressed abundantly in the proximal tubule, glomerular podocyte and less in the medullary thick ascending limb [8, 13]. In contrast IGF-1 expression is localized to medullary thick ascending limb, the distal nephron and collecting duct, and in the glomerulus, with the lowest levels in the proximal tubules [14]. Both GH and IGF-1 have significant effects on renal growth, glomerular hemodynamics and tubular reabsorption of water, sodium and phosphate [12, 15]. The GH/IGF-1 axis promotes renal growth by regulating cellular hyperplasia and hypertrophy, and accelerates renal blood flow and GFR. The GH/IGF-1 axis regulates intra-renal hemodynamics via increase in cyclooxygenase activity and the generation of nitrous oxide which induces glomerular arteriolar vasodilatation and increases the glomerular ultrafiltration coefficient.

GH/IGF-1 Axis in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus

Elevated mean 24-hour concentrations of circulating GH and an exaggerated GH response to several physiological and pharmacological provocative stimuli are characteristic features of patients with poorly controlled Type 1 DM [16–23]. Paradoxically, despite the increase in the concentrations of circulating GH in patients with poor glycemic control, the concentrations of circulating IGF-1 are decreased, suggesting a state of GH resistance/insensitivity in Type 1 DM [24–26], Thus GH hypersecretion in Type 1 DM is the result of negative feedback on the hypothalamus and pituitary from reduced levels of circulating IGF-1 and decreased action of IGF-1 at the cellular level. The decrease in circulating levels of IGF-1 reflects a state of GH resistance secondary to decreased hepatic GHR mRNA and protein expression and abnormalities in GHR signaling pathways in the liver in uncontrolled diabetes. Thus in rodent models of Type 1 DM steady state levels of hepatic GHR and GHBP mRNA are markedly decreased [27, 28]. In humans circulating levels of GHBP, a surrogate marker of hepatic GHR abundance, is decreased in children and adults with Type 1 DM [29–31]. Additionally chronic hypoinsulinemia in Type 1 DM results in increased hepatic production and elevated serum concentrations of IGFBP-1 [32]. Increase in serum IGFBPs, especially IGFBP-1 leads to inhibition of IGF-1 action at the cellular level and thus stimulates GH hypersecretion by the pituitary gland.

Experimental evidence supporting a role of GH in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy

The pathogenesis of DN is complex and a panoply of factors and processes are implicated in the causation and progression of DN. Additionally the roles of these various factors and processes are also dependent on the stage of the disease. Thus the GH/IGF-1 axis appears to play a role in the pathogenesis of early renal changes of DN. A role for GH in the pathogenesis of DN is suggested by the observation that transgenic mice over-expressing hGH develop progressive glomerulosclerosis [33–35]. In contrast transgenic mice expressing hIGF-1 did not develop renal damage although their glomeruli were enlarged [34]. These findings argue for an IGF-1 independent role for GH in DN. Conversely, a decrease in GH action either due to decrease in circulating levels of GH or the absence or blockade of the GHR is associated with relative protection against the development of many of the changes that are the hallmarks of DN in animal models [36–38]. For example, diabetic dwarf rats with diminished GH secretion exhibited less renal and glomerular hypertrophy compared with diabetic control animals with intact pituitary function [39, 40]. Moreover, administration of the long-acting somatostatin analogue Sandostatin (octreotide) effectively prevented the obligatory increase in kidney IGF-1 content and kidney growth in streptozotocin (STZ) induced diabetic rats [41, 42]. Similarly, lanreotide a long-acting somatostatin analogue has been shown to inhibit renal glomerular growth in diabetic rats [43]. It is noteworthy that long-acting somatostatin analogues prevent kidney hypertrophy without altering the metabolic state in these diabetic animals. STZ-diabetic rats treated with the somatostatin analogue SMS 201-995 displayed a significant decrease in urinary albumin excretion (UAE) (151 ± 76 vs 98 ± 46 mg/day/kg; pre- vs post-treatment) and albumin clearance (5.85 ± 3.34 vs 3.63 ± 1.73 mL/day/kg; pre- vs post-treatment) [44]. SMS 201-995 treatment of the diabetic cohort was also associated with a significantly lower kidney weight (2.68 ± 0.26 vs 3.35 ± 0.39 gm; treated vs untreated). Furthermore, in the rodent model, whereas treatment with octreotide from the day of onset of diabetes completely inhibited renal hypertrophy and increase in kidney IGF-1, postponement of the octreotide treatment resulted in only a partial inhibition of renal hypertrophy [42]. Similarly, GH antagonism by somatostatin analogue PTR-3173 had a blunting effect on renal hypertrophy, albuminuria, and GFR in diabetic NOD mice [45]. Mice with deletion of the GHR gene (total body GHR null mice) exhibited protection against STZ diabetes-induced nephropathy compared to wild type and GHR heterozygous mice which showed pathological changes such as increase in glomerular volume, increase in the ratio of mesangial area to total glomerular area, and glomerulosclerosis [36]. Similarly, administration of GHR antagonist G120K-polyethylene glycol protected against renal changes in rodent models of Type 1 DM. Thus treatment of STZ-diabetic mice with the GHR antagonist for a month resulted in normalization of kidney weight, glomerular volume, and renal IGF-1 content with attenuation of albuminuria [46].

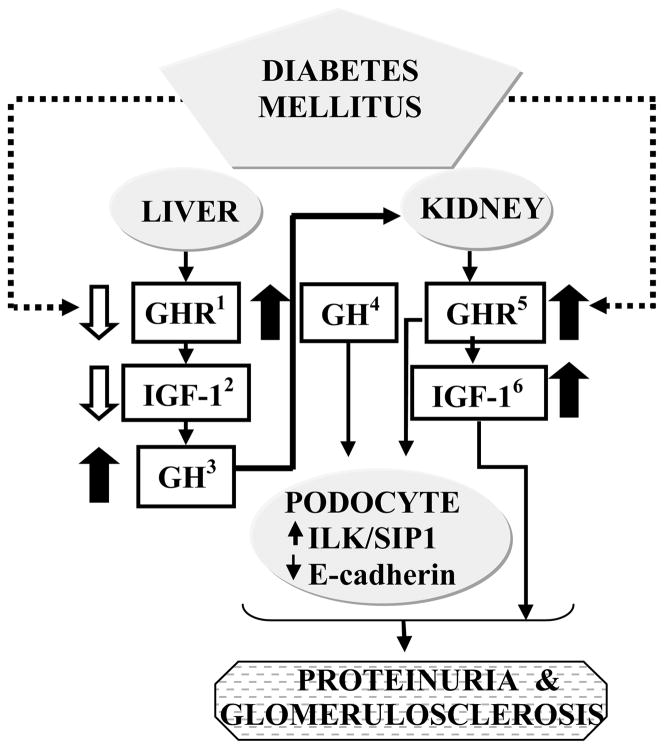

As noted above, GH resistance/insensitivity in poorly controlled Type 1 DM is secondary to decreased hepatic expression of GHR and abnormalities in GHR signaling pathways in the liver. In contrast to these hepatic changes, kidney GHR expression is maintained in rodent models of Type 1 DM [27, 47]. These results indicate that whereas decreased expression of hepatic GHR results in GH insensitivity and a compensatory increase in circulating concentrations of GH, the kidneys are likely to be sensitive to increased levels of GH (Fig 1). This hypothesis of “selective” responsiveness of tissues to GH in DM is also supported by studies that demonstrate that the GHR signaling pathways are more active in the kidneys of DM animals compared to control animals [38].

Fig 1. Role of the GH/IGF-1 axis in the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy.

Poorly controlled Type 1 diabetes mellitus is characterized by decreased GHR expression and activity in the liver(1) and consequent decrease in hepatic IGF-1 production(2). Low circulating levels IGF-1 levels stimulate increased pituitary GH secretion(3) via negative feed back loop mechanisms. In contrast to the liver, in the kidney GHR(5) expression is maintained (or increased) and hence the kidney is exposed to the effects of the elevated levels of GH(4) in the circulation. One of the cell types that is a direct target for GH action in the kidney is the glomerular podocyte. GH’s actions on the podocytes include modulation of levels of proteins such as SIP1 and E-cadherin that in concert with actions of IGF-1 could play a role in the pathogenesis of proteinuria and other changes characteristic of diabetic nephropathy.

Clinical evidence for a correlation between activity of the GH/IGF-1 axis and diabetic nephropathy

In the human a direct relationship has been noted between the activity of the GH/IGF-1 axis and GFR, renal hypertrophy, microalbuminuria, and glomerulosclerosis in DM [48–50]. Daily injection of GH to normal subjects for a week resulted in significant increase in GFR [48]. Administration of somatostatin analogue SMS 201-995 to patients with Type 1 DM resulted in a decrease in GFR [51]. In another study of patients with Type 1 DM with glomerular hyperfitration, subcutaneous infusion of octreotide for 12 weeks significantly lowered the elevated GFR (136 vs 157 mL/min; treatment vs placebo) and kidney size [52]. The administration of a long-acting somatostatin analogue (Samatuline) for 3 months to patients with Type 1 DM and renal hyperfiltration lowered GFR and renal plasma flow rate compared with placebo [53]. However, on continuing the administration of Samatuline the differences between treated and placebo group failed to maintain statistical significance. In patients with acromegaly, surgical ablation of pituitary adenoma resulted in decreased GH levels and GFR followed by decrease in kidney size to normal values [26].

In contrast to Type 1 DM, the relationship between GH/GHR axis and chronic complications in Type 2 DM is less clear. The preponderance of evidence indicates that in Type 2 DM circulating levels of GH levels are not elevated and a direct link between the GH/GHR axis and pathogenesis of DM nephropathy in Type 2 DM is unsubstantiated.

The glomerular podocyte in diabetes: a target for GH action

Podocytes are highly branched, terminally differentiated visceral epithelial cells of the renal glomerulus that are critical for the formation of the glomerular filtration barrier which prevents loss of macromolecules such as proteins into the glomerular filtrate. Podocyte damage and loss is an early and fundamental aspect of diabetic nephropathy in humans [54] and in a number of animal models [55]. Severe injury leads to loss of podocytes which can ultimately result in deterioration of renal function [56]. Reduction in podocyte number has been shown to predict the progressive decline in renal function in diabetic nephropathy [57].

As noted above, a direct relationship has been observed between the activity of the GH/IGF-1 axis and renal hypertrophy, microalbuminuria, and glomerulosclerosis [48–50]. However it is not clear whether this causal role of the GH/IGF-I axis in the pathogenesis of podocyte injury in DN is due to direct actions of GH on the kidney or indirect effects on systemic vascular tone and/or blood pressure. Our laboratory has recently demonstrated expression of GHR mRNA and protein in podocytes both in cell culture and in the renal glomerulus [8]. We further established that the canonical GHR signaling pathways are intact in the podocyte and that exposure of podocytes to GH results in intracellular redistribution of the JAK-2 adapter protein Src homology 2-Bβ (SH2-Bβ), stimulation of focal adhesion kinase (FAK), increase in reactive oxygen species (ROS), and GH-dependent changes in the podocyte actin cytoskeleton [8]. The podocyte cytoskeleton is critical for maintenance of the structure of the podocyte foot process and attachment of the podocyte to the glomerular basement membrane [58]. Actin filaments are an important component of the podocyte cytoskeleton and previous studies have demonstrated a role for SH2-Bβ in regulation of actin cross-linking [59]. Hence our findings of GH-dependent changes in (SH2-Bβ) sub-cellular localization could provide a mechanistic basis for GH’s effects on podocyte function and suggest that the glomerular podocyte could be a target for the elevated concentrations of GH in poorly controlled Type 1 DM [60].

DM is associated with decreased podocyte number and/or foot process effacement [54]. Podocytes from proteinuric GH-transgenic mice demonstrate induction of integrin-linked kinase (ILK) compared with wild-type littermates [61]. A variety of renal diseases including DN, all characterized by significant alterations to the filtration barrier, are characterized by ILK induction [61–65]. ILK, a serine threonine kinase plays a key role in integrin-mediated cell adhesion and signaling. It is hypothesized that induction of ILK alters podocyte function via ILK-dependent inhibition of E-cadherin expression and activation of the β-catenin/LEF transcriptional complex with consecutive increase in matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) [66, 67]. MMP-9 is a gelatinase that degrades type IV collagen (the major component of the GBM) and is thus crucial to maintaining the integrity of the GBM. Ongoing studies in our laboratory have indicated that in the podocyte GH increases levels of SIP1/ZEB2 a member of the δEF-1 family of two-handed zinc finger nuclear factors [68]. It is well established that SIP1 inhibits E-cadherin expression [69, 70] and our studies demonstrate a temporal association between GH-dependent induction of SIP1 and decrease in levels of E-cadherin in the podocyte [68]. Our results reveal that the GH-dependent increase in SIP1 in podocytes is associated with increased permeability and enhanced protein leakage across a podocyte monolayer [71]. In addition we have also observed that GH induces apoptosis of the podocyte in a hyperglycemia-dependent manner [72]. These findings suggest novel mechanisms for GH’s action on the podocyte in DM.

Summary and conclusion

Data accumulated over the past decade from both experimental studies in animals and observations and clinical trials in humans have suggested an essential role for the GH/IGF-1 axis in the pathogenesis of DN in Type 1 DM (Table 1). Overall these data indicate that the state of GH hypersecretion in poorly controlled Type 1 DM plays a causal role in the pathogenesis of early changes of DN. One of the targets for the GH action identified in kidney that is directly relevant to the pathogenesis of DN is the glomerular podocyte. Hence, strategies and therapeutic regimens that abrogate GH action on the glomerular podocyte could provide protection against the early changes of DN. Thus, GH antagonists (e.g. pegvisomant) and drugs that target GHR signaling cascades are potential agents in the therapeutic armamentarium for preventing and treating DN [73]. The therapeutic effectiveness and clinical role(s) of these types of interventions will be elucidated by carefully planned clinical trials carried out with appropriate cohorts of patients.

Table 1.

| Abnormalities in the GH/IGF-1 Axis in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

| Abnormalities in the GH/IGF-1 Axis in the kidney in Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus |

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (DK49845 [RKM], and P60DK-20572 [Michigan Diabetes Research and Training Center]).

Abbreviations

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- DN

Diabetic nephropathy

- ESRD

End stage renal disease

- GFR

Glomerular filtration rate

- GH

Growth hormone

- GHR

GH receptor

- GHBP

GH binding protein

- IGF

Insulin-like growth factor

- IGFBP

IGF binding protein

- ILK

Integrin-linked kinase

- JAK2

Janus kinase 2

References

- 1.Moller N, Jorgensen JO. Effects of growth hormone on glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism in human subjects. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:152–77. doi: 10.1210/er.2008-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baumann G. Growth hormone binding protein 2001. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2001;14:355–75. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2001.14.4.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JR, Benghuzzi H, Tucci M, et al. The effects of growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor on the proliferation rate and morphology of RAW 264. 7 macrophages. Biomed Sci Instrum. 2000;36:111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pantaleon M, Whiteside EJ, Harvey MB, et al. Functional growth hormone (GH) receptors and GH are expressed by preimplantation mouse embryos: a role for GH in early embryogenesis? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5125–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han X, Ren X, Jurickova I, et al. Regulation of intestinal barrier function by signal transducer and activator of transcription 5b. Gut. 2009;58:49–58. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.145094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu C, Schwartzbauer G, Sperling MA, et al. Demonstration of direct effects of growth hormone on neonatal cardiomyocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22892–900. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011647200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baudet ML, Rattray D, Martin BT, Harvey S. Growth hormone promotes axon growth in the developing nervous system. Endocrinology. 2009;150:2758–66. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reddy GR, Pushpanathan MJ, Ransom RF, et al. Identification of the glomerular podocyte as a target for growth hormone action. Endocrinology. 2007;148:2045–55. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferry RJ, Jr, Cerri RW, Cohen P. Insulin-like growth factor binding proteins: new proteins, new functions. Horm Res. 1999;51:53–67. doi: 10.1159/000023315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Renal Data System. USRDS 2009 Annual Data Report: Atlas of ESRD. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; Bethesda, MD: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ruggenenti P, Remuzzi G. Nephropathy of type-2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:2157–69. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V9112157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feld S, Hirschberg R. Growth hormone, the insulin-like growth factor system, and the kidney. Endocr Rev. 1996;17:423–80. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-5-423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin E, Zhou J, Bondy CA. Renal growth hormone receptor gene expression: relationship to renal insulin-like growth factor system. Endocrinology. 1992;131:3061–6. doi: 10.1210/endo.131.6.1446640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin E, Zhou J, Bondy C. Anatomical relationships in the patterns of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-1, and IGF-I receptor gene expression in the rat kidney. Endocrinology. 1992;130:3237–45. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.6.1375897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johannsson G, Sverrisdottir YB, Ellegard L, et al. GH increases extracellular volume by stimulating sodium reabsorption in the distal nephron and preventing pressure natriuresis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:1743–1749. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.4.8394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen AP. Abnormal serum growth hormone response to exercise in juvenile diabetics. J Clin Invest. 1970;49:1467–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI106364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sperling MA, Wollesen F, DeLamater PV. Daily production and metabolic clearance of growth hormone in juvenile diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 1973;9:380–3. doi: 10.1007/BF01239431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayford JT, Danney MM, Hendrix JA, Thompson RG. Integrated concentration of growth hormone in juvenile-onset diabetes. Diabetes. 1980;29:391–8. doi: 10.2337/diab.29.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorenzi M, Karam JH, McIlroy MB, Forsham PH. Increased growth hormone response to dopamine infusion in insulin-dependent diabetic subjects: indication of possible blood-brain barrier abnormality. J Clin Invest. 1980;65:146–53. doi: 10.1172/JCI109644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krassowski J, Felber JP, Rogala H, et al. Exaggerated growth hormone response to growth hormone-releasing hormone in type I diabetes mellitus. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1988;117:225–9. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.1170225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Asplin CM, Faria AC, Carlsen EC, et al. Alterations in the pulsatile mode of growth hormone release in men and women with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;69:239–45. doi: 10.1210/jcem-69-2-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edge JA, Dunger DB, Matthews DR, et al. Increased overnight growth hormone concentrations in diabetic compared with normal adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1990;71:1356–62. doi: 10.1210/jcem-71-5-1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almqvist EG, Groop LC, Manhem PJ. Growth hormone response to the insulin tolerance and clonidine tests in type 1 diabetes. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1999;59:375–82. doi: 10.1080/00365519950185571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bereket A, Lang CH, Wilson TA. Alterations in the growth hormone-insulin-like growth factor axis in insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Horm Metab Res. 1999;31:172–81. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-978716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamborlane WV, Hintz RL, Bergman M, et al. Insulin-infusion-pump treatment of diabetes: influence of improved metabolic control on plasma somatomedin levels. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:303–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198108063050602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonksen PH, Russell-Jones D, Jones RH. Growth hormone and diabetes mellitus. A review of sixty-three years of medical research and a glimpse into the future? Horm Res. 1993;40:68–79. doi: 10.1159/000183770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Menon RK, Stephan DA, Rao RH, et al. Tissue-specific regulation of the growth hormone receptor gene in streptozocin-induced diabetes in the rat. J Endocrinol. 1994;142:453–62. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1420453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Menon RK, Shaufl A, Yu JH, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel transcript of the murine growth hormone receptor gene exhibiting development- and tissue-specific expression. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2001;172:135–46. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(00)00375-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Menon RK, Arslanian S, May B, et al. Diminished growth hormone-binding protein in children with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:934–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.74.4.1548360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mercado M, Molitch ME, Baumann G. Low plasma growth hormone binding protein in IDDM. Diabetes. 1992;41:605–9. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.5.605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arslanian SA, Menon RK, Gierl AP, et al. Insulin therapy increases low plasma growth hormone binding protein in children with new-onset type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 1993;10:833–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1993.tb00175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilding A, Brismar K, Degerblad M, et al. Altered relation between circulating levels of insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 and insulin in growth hormone-deficient patients and insulin-dependent diabetic patients compared to that in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2646–52. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.9.7545695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doi T, Striker LJ, Quaife C, et al. Progressive glomerulosclerosis develops in transgenic mice chronically expressing growth hormone and growth hormone releasing factor but not in those expressing insulinlike growth factor-1. Am J Pathol. 1988;131:398–403. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doi T, Striker LJ, Gibson CC, et al. Glomerular lesions in mice transgenic for growth hormone and insulinlike growth factor-I. I. Relationship between increased glomerular size and mesangial sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:541–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang CW, Striker LJ, Kopchick JJ, et al. Glomerulosclerosis in mice transgenic for native or mutated bovine growth hormone gene. Kidney Int Suppl. 1993;39:S90–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bellush LL, Doublier S, Holland AN, et al. Protection against diabetes-induced nephropathy in growth hormone receptor/binding protein gene-disrupted mice. Endocrinology. 2000;141:163–8. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.1.7284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flyvbjerg A, Bennett WF, Rasch R, et al. Inhibitory effect of a growth hormone receptor antagonist (G120K-PEG) on renal enlargement, glomerular hypertrophy, and urinary albumin excretion in experimental diabetes in mice. Diabetes. 1999;48:377–82. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thirone AC, Scarlett JA, Gasparetti AL, et al. Modulation of growth hormone signal transduction in kidneys of streptozotocin-induced diabetic animals: effect of a growth hormone receptor antagonist. Diabetes. 2002;51:2270–81. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flyvbjerg A, Frystyk J, Osterby R, Orskov H. Kidney IGF-I and renal hypertrophy in GH-deficient diabetic dwarf rats. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:E956–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1992.262.6.E956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gronbaek H, Volmers P, Bjorn SF, et al. Effect of GH/IGF-I deficiency on long-term renal changes and urinary albumin excretion in diabetic dwarf rats. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E918–24. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.5.E918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Flyvbjerg A, Frystyk J, Thorlacius-Ussing O, Orskov H. Somatostatin analogue administration prevents increase in kidney somatomedin C and initial renal growth in diabetic and uninephrectomized rats. Diabetologia. 1989;32:261–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00285295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flyvbjerg A, Marshall SM, Frystyk J, et al. Octreotide administration in diabetic rats: effects on renal hypertrophy and urinary albumin excretion. Kidney Int. 1992;41:805–12. doi: 10.1038/ki.1992.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gronbaek H, Nielsen B, Frystyk J, et al. Effect of lanreotide on local kidney IGF-I and renal growth in experimental diabetes in the rat. Exp Nephrol. 1996;4:295–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Igarashi K, Nakazawa A, Tani N, et al. Effect of a somatostatin analogue (SMS 201-995) on renal function and urinary protein excretion in diabetic rats. J Diabet Complications. 1991;5:181–3. doi: 10.1016/0891-6632(91)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Landau D, Segev Y, Afargan M, et al. A novel somatostatin analogue prevents early renal complications in the nonobese diabetic mouse. Kidney Int. 2001;60:505–512. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060002505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Segev Y, Landau D, Rasch R, et al. Growth hormone receptor antagonism prevents early renal in nonobese diabetic mice. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:2374–2381. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10112374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gowri PM, Yu JH, Shaufl A, et al. Recruitment of a repressosome complex at the growth hormone receptor promoter and its potential role in diabetic nephropathy. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:815–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.3.815-825.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Christiansen JS, Gammelgaard J, Orskov H, et al. Kidney function and size in normal subjects before and during growth hormone administration for one week. Eur J Clin Invest. 1981;11:487–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1981.tb02018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cummings EA, Sochett EB, Dekker MG, et al. Contribution of growth hormone and IGF-I to early diabetic nephropathy in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 1998;47:1341–6. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.8.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Blankestijn PJ, Derkx FH, Birkenhager JC, et al. Glomerular hyperfiltration in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus is correlated with enhanced growth hormone secretion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;77:498–502. doi: 10.1210/jcem.77.2.8345058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Krempf M, Ranganathan S, Remy JP, et al. Effect of long-acting somatostatin analog (SMS 201-995) on high glomerular filtration rate in insulin dependent diabetic patients. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther Toxicol. 1990;28:309–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Serri O, Beauregard H, Brazeau P, et al. Somatostatin analogue, octreotide, reduces increased glomerular filtration rate and kidney size in insulin-dependent diabetes. JAMA. 1991;265:888–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jacobs ML, Derkx FH, Stijnen T, et al. Effect of long-acting somatostatin analog (Somatulin) on renal hyperfiltration in patients with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:632–6. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pagtalunan ME, Miller PL, Jumping-Eagle S, et al. Podocyte loss and progressive glomerular injury in type II diabetes. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:342–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI119163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brosius FC, 3rd, Alpers CE, Bottinger EP, et al. Mouse models of diabetic nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2503–12. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009070721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wharram BL, Goyal M, Wiggins JE, et al. Podocyte depletion causes glomerulosclerosis: diphtheria toxin-induced podocyte depletion in rats expressing human diphtheria toxin receptor transgene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2941–52. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005010055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyer T, Bennett P, Nelson R. Podocyte number predicts long-term urinary albumin excretion in Pima Indians with Type II diabetes and microalbuminuria. Diabetologia. 1999;42:1341–4. doi: 10.1007/s001250051447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Drenckhahn D, Franke RP. Ultrastructural organization of contractile and cytoskeletal proteins in glomerular podocytes of chicken, rat, and man. Lab Invest. 1988;59:673–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rider L, Tao J, Snyder S, et al. Adapter protein SH2B1beta cross-links actin filaments and regulates actin cytoskeleton. Mol Endocrinol. 2009;23:1065–76. doi: 10.1210/me.2008-0428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reddy GR, Kotlyarevska K, Ransom RF, Menon RK. The podocyte and diabetes mellitus: is the podocyte the key to the origins of diabetic nephropathy? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2008;17:32–6. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282f2904d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kretzler M, Teixeira VP, Unschuld PG, et al. Integrin-linked kinase as a candidate downstream effector in proteinuria. FASEB J. 2001;15:1843–5. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0832fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guo L, Sanders PW, Woods A, Wu C. The distribution and regulation of integrin-linked kinase in normal and diabetic kidneys. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1735–42. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63020-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li Y, Yang J, Dai C, et al. Role for integrin-linked kinase in mediating tubular epithelial to mesenchymal transition and renal interstitial fibrogenesis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003;112:503–516. doi: 10.1172/JCI17913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.de Paulo Castro Teixeira V, Blattner SM, Li M, et al. Functional consequences of integrin-linked kinase activation in podocyte damage. Kidney Int. 2005;67:514–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu Y. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition in renal fibrogenesis: pathologic significance, molecular mechanism, and therapeutic intervention. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1–12. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000106015.29070.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Teixeira VP, Blattner SM, Li M, et al. Functional consequences of integrin-linked kinase activation in podocyte damage. Kidney Int. 2005;67:514–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.67108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.von Luttichau I, Djafarzadeh R, Henger A, et al. Identification of a signal transduction pathway that regulates MMP-9 mRNA expression in glomerular injury. Biol Chem. 2002;383:1271–5. doi: 10.1515/BC.2002.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kotlyarevska K, Dejkhamron P, Gaddameedi R, et al. GH-dependent regulation of ZEB-2/SIP1 expression in glomerular podocytes: a novel crosstalk between GH and TGF-β pathways and its implication for the development of diabetic nephropathy. 89th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society; June 15–18; San Francisco, CA. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Comijn J, Berx G, Vermassen P, et al. The two-handed E box binding zinc finger protein SIP1 downregulates E-cadherin and induces invasion. Mol Cell. 2001;7:1267–78. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van Grunsven LA, Michiels C, Van de Putte T, et al. Interaction between Smad-interacting protein-1 and the corepressor C-terminal binding protein is dispensable for transcriptional repression of E-cadherin. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:26135–45. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300597200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kumar P, Kotlyarevska K, Dejkhamron P, et al. Regulation of SIP1 expression in podocytes by growrth hormone. 2010. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Pasupulati A, Sun J, Inoki K, Menon R. Regulation of Akt/mTOR signaling in podocytes by growth hormone: implications for the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. 91st Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society; June 10–13, 2009; Washington DC. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Muller AF, Kopchick JJ, Flyvbjerg A, van der Lely AJ. Growth Hormone Receptor Antagonists. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:1503–1511. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-022049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Amin R, Williams RM, Frystyk J, et al. Increasing urine albumin excretion is associated with growth hormone hypersecretion and reduced clearance of insulin in adolescents and young adults with type 1 diabetes: the Oxford Regional Prospective Study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2005;62:137–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Landau D, Segev Y, Eshet R, et al. Changes in the growth hormone-IGF-I axis in non-obese diabetic mice. Int J Exp Diabetes Res. 2000;1:9–18. doi: 10.1155/EDR.2000.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Johansen PB, Segev Y, Landau D, et al. Growth hormone (GH) hypersecretion and GH receptor resistance in streptozotocin diabetic mice in response to a GH secretagogue. Exp Diabesity Res. 2003;4:73–81. doi: 10.1155/EDR.2003.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Amin R, Schultz C, Ong K, et al. Low IGF-I and elevated testosterone during puberty in subjects with type 1 diabetes developing microalbuminuria in comparison to normoalbuminuric control subjects: the Oxford Regional Prospective Study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1456–61. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.5.1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Taylor AM, Dunger DB, Grant DB, Preece MA. Somatomedin-C/IGF-I measured by radioimmunoassay and somatomedin bioactivity in adolescents with insulin dependent diabetes compared with puberty matched controls. Diabetes Res. 1988;9:177–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Munoz MT, Barrios V, Pozo J, Argente J. Insulin-like growth factor I, its binding proteins 1 and 3, and growth hormone-binding protein in children and adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: clinical implications. Pediatr Res. 1996;39:992–8. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199606000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Landau D, Domene H, Flyvbjerg A, et al. Differential expression of renal growth hormone receptor and its binding protein in experimental diabetes mellitus. Growth Horm IGF Res. 1998;8:39–45. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(98)80320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Segev Y, Landau D, Marbach M, et al. Renal hypertrophy in hyperglycemic non-obese diabetic mice is associated with persistent renal accumulation of insulin-like growth factor I. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1997;8:436–44. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V83436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flyvbjerg A. Role of growth hormone, insulin-like growth factors (IGFs) and IGF-binding proteins in the renal complications of diabetes. Kidney Int Suppl. 1997;60:S12–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Landau D, Chin E, Bondy C, et al. Expression of insulin-like growth factor binding proteins in the rat kidney: effects of long-term diabetes. Endocrinology. 1995;136:1835–42. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.5.7536658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kaufman CR, Catanese VM. Pre-and post-translational regulation of renal insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 in insulin-deficient diabetes. Journal of Investigative Medicine. 1995;43:178–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]