Abstract

Anorexia nervosa and obesity are conditions at the extreme ends of the nutritional spectrum, associated with marked reductions versus increases respectively in body fat content. Both conditions are also associated with an increased risk for fractures. In anorexia nervosa, body composition and hormones secreted or regulated by body fat content are important determinants of low bone density, impaired bone structure and reduced bone strength. In addition, anorexia nervosa is characterized by increases in marrow adiposity and decreases in cold activated brown adipose tissue, both of which are related to low bone density. In obese individuals, greater visceral adiposity is associated with greater marrow fat, lower bone density and impaired bone structure. In this review, we discuss bone metabolism in anorexia nervosa and obesity in relation to adipose tissue distribution and hormones secreted or regulated by body fat content.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, obesity, overweight, adolescents, bone density, bone microarchitecture, bone structure, finite element analysis

INTRODUCTION

Anorexia nervosa (AN) and obesity are disorders at the extreme ends of the nutritional spectrum, and are characterized by marked changes in body composition and various hormonal axes. These changes in body composition and hormones in turn impact the skeletal system with an increased risk for fractures reported in both AN and obesity (1–5). AN is associated with marked reductions in fat mass (a reflection of energy stores), whereas obesity is associated with marked increases in fat mass.. Adipose tissue is a source of hormones such as leptin and adiponectin that have effects on bone metabolism. It also secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines that have deleterious effects on bone, and may regulate secretion of other hormones that impact bone.

Adipocytes and osteoblasts differentiate from a common progenitor mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) in bone marrow, and specific transcription factors direct MSC differentiation along the adipocyte vs. osteoblast lineage such that increased differentiation along one lineage may affect differentiation along the other (6, 7). Of note, marrow fat (known to be inversely associated with bone density) is increased in AN compared to a normal-weight control population (8), and is also higher in obese women who have greater visceral fat (9). This review will discuss the impact of body composition and fat distribution on hormones and bone metabolism in AN and obesity, conditions of extreme energy deficiency and excess, respectively.

ANOREXIA NERVOSA

The deleterious effects of anorexia nervosa (AN) on bone have been recognized for many years, and this section will discuss bone metabolism in adolescents and adults with AN, and the impact of decreases in adipose tissue on bone.

Bone Mineral Density, Bone Microarchitecture and Strength, and Fractures

Bone Mineral Density

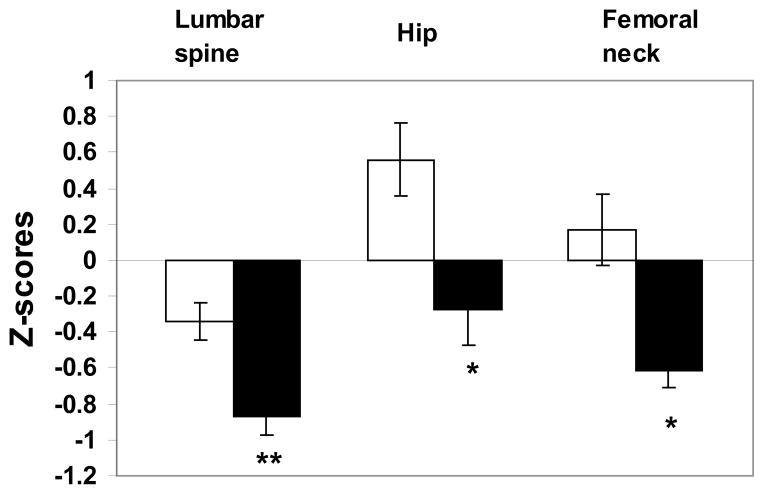

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a condition of severe undernutrition associated with altered body image that commonly onsets in the adolescent and young adult years, and is reported in 0.2–1% of young women (10). Functional hypothalamic oligo-amenorrhea is a common feature of both adolescents and adults with this condition, as is low bone mineral density (BMD) (Figure 1). In one study of adolescent girls with AN, over 50% of the girls had areal BMD Z-scores of <−1 at one or more sites (11). Among adult women with AN, low bone density is even more prevalent with 92% and 38% of the women having areal BMD T-scores of < −1 and < −2.5 respectively at one or more sites, with the spine being preferentially affected (12). Although AN is preferentially seen in females, males with AN are also at risk for low bone density (13). We have reported that 65% and 50% of boys with AN had BMD Z-scores of <−1 at the femoral neck and the spine respectively compared with 18 and 24% of controls (14). In addition to areal BMD, height adjusted measures of BMD such as spine bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) are lower in adolescent boys and girls with AN than in controls (14, 15).

Figure 1.

Z scores for lumbar spine, hip, and femoral neck bone mineral density (BMD) in girls with anorexia nervosa (AN) (black bars) and healthy control subjects (white bars). Girls with AN had significantly lower Z-scores at each site than healthy adolescents. *P< .01; **P ≤ .001. From Misra et al. Pediatrics 2004;114:1574–1583 Copyright © 2004 by the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Low bone density in adolescents with AN is associated with decreased bone turnover, and levels of surrogate markers of bone formation and resorption are lower in AN than in normal-weight controls (14, 16, 17). This is in contrast to the state of increased bone turnover that is characteristic of normal puberty. Conversely, adult women with AN have an uncoupling of bone turnover with a decrease in markers of bone formation and an increase in markers of bone resorption (18).

In contrast to loss of established bone mass in adults with AN, a major concern in adolescents with AN is a decreased rate of bone accrual over time (15, 19). The onset of AN often coincides with peak bone mass accrual which is typically achieved by the middle of the third decade, and is an important determinant of future fracture risk. In addition to reported effects of AN on bone density, a higher prevalence of fractures has been reported in women with AN compared with normal-weight women (1).

Bone microarchitecture, strength estimates and fractures

Availability of peripheral quantitative computed tomography (pQCT) has allowed assessment of bone geometry and volumetric BMD in AN. Furthermore, availability of high resolution pQCT (HRpQCT) has allowed determination of cortical and trabecular microarchitecture, as well as application of micro-finite element analysis (μFEA) techniques to estimate bone strength. Adolescent girls with AN have decreased cortical area and increased trabecular area than normal-weight controls, and cortical porosity is increased (20). Additionally, trabecular thickness, and trabecular and total volumetric BMD are decreased. We have shown that estimates of strength such as stiffness and failure load are lower in girls with AN compared with controls (20). Importantly, in a study using flat panel ultra high resolution volumetric CT, we reported that bone microarchitecture may show abnormalities in AN even before changes are evident in areal BMD as assessed by DXA (21). In this study, girls with AN had lower bone trabecular volume and trabecular thickness, and greater trabecular separation than controls, despite similar areal BMD. Therefore even adolescents with AN who have apparently normal BMD as assessed by DXA scans may already show the deleterious effects of the disease on more sensitive skeletal parameters.

Bone microarchitecture is even more severely affected in adult women with AN (22, 23). Consistent with data from studies of bone microarchitecture and strength, adult women with AN have a higher risk for fractures than the normal population (1). Our studies also indicate higher fracture risk in adolescents with AN compared with normal weight adolescents (31% vs. 19%) both before and after the diagnosis of AN, although the risk increases after AN diagnosis (24).

Although there are no data available of bone microarchitecture using pQCT techniques in boys with AN, we have reported data from hip structural analysis (HSA) using DXA (25) in boys with this disorder (26). This is a validated technique to assess hip geometry in both adults and adolescents (27–31). Adolescent boys with AN have lower cross-sectional area, cross-sectional moment of inertia and section modulus of the narrow neck, trochanteric region and femoral shaft than controls after controlling for age and height (26). Boys with AN also have lower cortical thickness at the narrow neck and trochanteric region, and greater buckling ratio at the trochanteric region. These differences suggest lower bone strength at the hip in boys with AN than in controls.

Impact of Body Composition on Bone (Including Effects of Weight Recovery)

Lean and Fat Mass

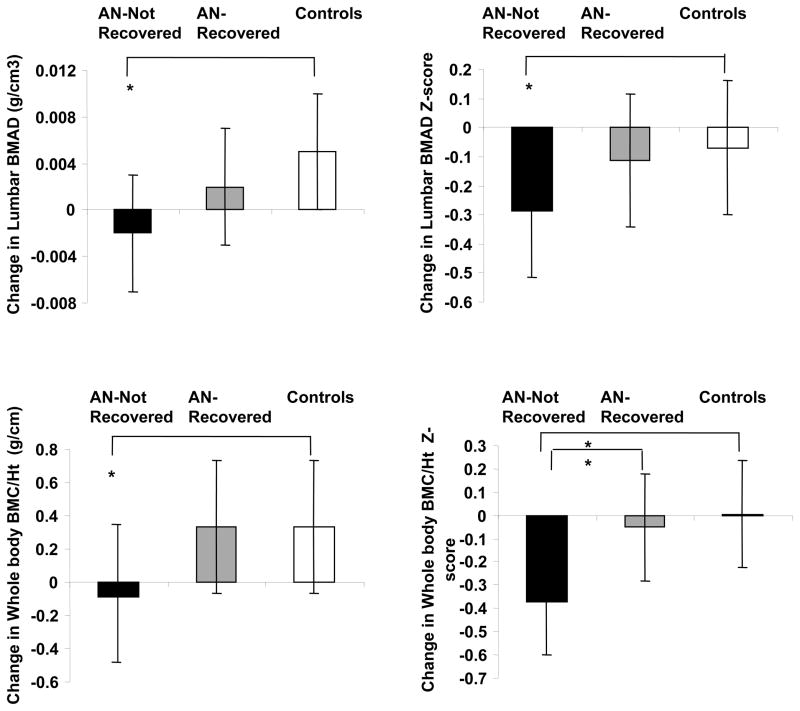

BMI and lean mass are independent predictors of bone density in males and females with AN, particularly at cortical sites (11, 14, 19). In adolescent girls with AN, increases in lean body mass during weight recovery predict increases in bone density (19). Although lower fat mass is associated with lower bone density, lean mass is a stronger determinant of bone density measures than fat mass, consistent with mechanical loading having a protective effect on bone. In adult women with AN, weight gain is associated with a preferential increase in bone density at the total hip (a mostly cortical site), whereas menstrual recovery is associated with an increase in bone density at the spine (a mostly trabecular site) (32). These data are consistent with the known effects of estrogen deprivation on trabecular bone mass. In adolescents with AN, recovery of weight and menses is associated with an improvement in bone accrual rates, although residual deficits persist, concerning for suboptimal peak bone mass acquisition despite recovery (15) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Change in lumbar bone mineral apparent density (BMAD) and whole body bone mineral content/height (WB BMC/Ht) measures in anorexia nervosa (AN)-not recovered (black bars), AN-recovered (gray bars), and healthy adolescents (white bars) over 1-year. AN-not recovered continued to lose bone mass over the 1-year follow-up period, and change in bone density measures was significantly lower in this group compared with controls (Tukey-Kramer test for multiple comparisons). AN-recovered did not differ from controls for change in bone density parameters and differed significantly from AN-not recovered for change in whole body bone density Z-scores. *, P <0.05. From Misra et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008;93: 1231–1237. Copyright © 2008 by The Endocrine Society.

Marrow Adipose Tissue

In healthy children and adults, a reciprocal relationship has been reported between marrow adiposity and bone parameters at the axial and appendicular skeleton (33–36). Using magnetic resonance spectroscopy techniques, we have shown that adults with AN have increased marrow fat compared with normal-weight controls, and marrow fat is inversely associated with areal bone density measures (8). Additionally, preadipocyte factor-1 (Pref-1), a member of the epidermal growth factor-like family of proteins that reduces differentiation along the osteoblast lineage, is higher in women with AN than controls, and higher Pref-1 levels are associated with higher marrow fat and lower areal BMD (37). Both marrow fat and Pref-1 levels decrease with recovery from AN (38).

Brown Adipose Tissue

Inducible brown adipose tissue (or beige fat) has been demonstrated to have anabolic effects on the skeleton in animal models (39), and positive associations have been reported of cold activated brown adipose tissue (BAT) with bone density measures in healthy adults and with cross-sectional dimensions on bone in healthy children (40, 41). Women with AN have lower cold-induced BAT than controls (42), likely an adaptive response to reduce cold induced thermogenesis and energy expenditure, and lower BAT content is associated with lower bone density. In addition, IGF binding protein-2 is an inverse predictor of cold induced BAT and BMD, possibly subsequent to increased binding to IGF-1, a crucial regulator of brown fat adipogenesis (43).

Effects of adipocytokines and hormones regulated by fat mass (an indicator of energy status) on bone metabolism

Adipocytokines

AN is associated with alterations in inflammatory cytokines and hormones such as leptin and adiponectin secreted by fat that can also impact bone. Leptin has opposing central and peripheral effects on bone, with central effects being mediated via the sympathetic system and being deleterious to axial bone (44), whereas peripheral leptin is bone anabolic at the appendicular skeleton (45). Adolescents and adults with AN have lower leptin levels than controls attributable to marked decreases in subcutaneous fat (46, 47), associated with lower bone density and impaired bone microarchitecture (23, 48). Administration of recombinant human (rh) leptin to women with functional hypothalamic amenorrhea causes an increase in levels in bone formation markers and in bone mineral content, but at the cost of reductions in appetite, weight and body fat mass (49, 50), consistent with the anorexigenic nature of this hormone and severely limiting its therapeutic potential. High adiponectin levels have been associated with lower bone density measures in healthy men and women (51, 52), and may be mediated by inhibition of osteoblasts and stimulation of RANKL mediated osteoclastic activity (53, 54). Adiponectin is a mediator of insulin sensitivity with effects on bone, and adiponectin levels have been variably reported to be higher, no different or lower in AN than in normal-weight controls (48, 55–58), which may be related to measurement of specific multimeric forms of adiponectin in the various studies. Our studies have demonstrated inverse associations of adiponectin with spine BMD and BMAD in adolescents with AN (48). Finally, inflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α and IL-6) stimulate osteoclastic bone resorption, and have been reported to be elevated in adolescents and adults with AN (59, 60).

Hormones Regulated by Energy Status (reflected as fat stores)

Lower fat mass in AN, a reflection of reduced energy stores, is associated with alterations in the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (H-P-G) axis, H-P-adrenal (H-P-A) axis, growth hormone (GH)-insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) axis, and hormones implicated in energy regulation such as insulin, amylin and the appetite regulating hormones [ghrelin, peptide YY (PYY)]. All these hormonal changes affect bone metabolism in AN.

Hypogonadism

An important consequence of AN is functional hypothalamic amenorrhea. Patterns of LH pulsatility revert to a prepubertal pattern of low amplitude LH pulses or an early pubertal pattern of nighttime entrainment in LH pulses (61). Both estradiol and testosterone levels are lower in females and males with AN compared with a control population (14, 19). These are primarily anti-resorptive hormones. Estrogen inhibits osteoclastic bone resorption by inhibiting RANKL and stimulating osteoprotegerin (OPG) secretion by osteoblasts (62, 63). Estrogen may also increase bone formation by inhibiting secretion of sclerostin, a transcription factor expressed by osteocytes that otherwise inhibits wnt signaling and therefore osteoblastic activity (64). Testosterone impacts bone through its aromatization to estradiol, but may have direct bone anabolic effects (63). In females with AN, lower levels of estradiol and testosterone, and a longer duration of amenorrhea predict lower measures of bone density (11, 19). Additionally, a later menarchal age is an important determinant of lower bone density and impaired bone microarchitecture. Similarly, in males with AN, lower testosterone and estradiol levels are associated with lower bone density (14).

Despite the strong association of gonadal steroid levels with bone density measures, administration of estrogen as an oral estrogen-progesterone combination pill does not increase bone density in adolescent girls and adult women with AN (65, 66), although in one study, a post-hoc analysis suggested that it may help in those with the lowest bone density (65). This has been attributed to the IGF-1 suppressive effects of oral estrogen from its hepatic first-pass effects, although a reduction in testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) may also contribute. In contrast, we have shown that administration of oral estrogen in physiologic doses to girls with immature bone age and as the transdermal estrogen patch (with cyclic progesterone) in those with mature bone age, is effective in increasing bone density in adolescent girls with AN to approximate bone accrual rates in normal-weight controls (17). However, bone accrual needs to exceed that in controls for girls with AN to ‘catch-up’ to controls, and this does not occur with only physiologic estrogen replacement, likely because other hormonal alterations persist. Therefore, additional therapeutics options will need to be explored to normalize bone mass in adolescents with AN.

In order to determine whether estrogen effects on bone are mediated by reductions in sclerostin, we examined changes in sclerostin following physiologic estrogen administration, and found no differences in changes in sclerostin in girls with AN randomized to estrogen versus placebo (67). In contrast, we found significant reductions in levels of Pref-1 following estrogen administration, suggesting a novel mechanism underlying the beneficial effects of estrogen on bone (68).

Lower testosterone levels are another important determinant of low bone density in AN, and testosterone administration in replacement doses (as the transdermal testosterone patch) causes an increase in markers of bone formation (69). However, long-term (12 months) testosterone administration was not effective in increasing bone density in adult women with AN despite an increase in lean body mass (70). One study reported lower DHEAS levels in adolescent and young adult women with AN in relation to a normative range (71). However, other studies have indicated that DHEAS levels do not differ in adolescents or adults with AN compared with controls (19). A combination of oral estrogen-progesterone pills with oral DHEA was shown to maintain bone density Z-scores over time in adolescent and young adult women with AN (72), although a previous study did not find a beneficial effect of DHEA administration on bone (73). No data are available thus far regarding effects of testosterone replacement on bone density measures in males with AN.

Nutritionally Acquired Growth Hormone Resistance and Low IGF-1 Levels

Low levels of GH binding protein in AN suggest decreased expression of the GH receptor and a state of GH resistance (74). This is corroborated by lower levels of IGF-1in AN despite higher concentrations of GH than in controls (75). Higher GH concentrations are consequent to an increase in secretory burst amplitude and frequency, and higher basal GH secretion (75). The increase in GH is likely an adaptive response to maintain euglycemia in a state of starvation by increasing availability of gluconeogenic substrates through increased lipolysis. GH concentrations are associated inversely with BMI and fat mass in AN, and are likely driven by lower levels of IGF-1 and higher levels of ghrelin, a GH secretagogue (75, 76).

Whereas normal-weight girls with higher GH concentrations have higher levels of bone turnover markers, consistent with the known effects of GH on osteoblasts and osteoclasts, this association is not observed in girls with AN, suggestive of skeletal GH resistance (75). This is further corroborated by lack of a significant increase in levels of IGF-1 and bone turnover markers following administration of supraphysiologic doses of rhGH to adult women with AN over a three month period, indicative of hepatic and bone resistance to GH (77). Of interest, administration of these supraphysiologic doses of rhGH led to a significant reduction of fat mass, consistent with preservation of direct (but not IGF-1 mediated) effects of GH in AN.

Lower IGF1 levels are associated with lower levels of bone formation markers, lower bone density, and impaired bone microarchitecture (19, 23). Administration of rhIGF-1 in replacement doses (30 mcg/kg/dose twice a day) causes an increase in markers of bone formation in adolescent girls and adults with AN (78, 79), and with oral estrogen causes a significant increase in bone density in adult women with AN (79). Studies of transdermal estrogen and rhIGF-1 are ongoing in adolescents with AN.

Relative Hypercortisolemia

AN is a state of relative hypercortisolemia, based on overnight frequent sampling for serum cortisol (higher cortisol AUC), higher nighttime salivary cortisols and 24-h urinary free cortisol, and higher levels of morning cortisol following a low dose overnight dexamethasone suppression test (80, 81). Increased cortisol in AN is likely an adaptive mechanism (similar to increases in GH) to maintain euglycemia in this state of low energy availability by increasing availability of gluconeogenic precursors. Higher cortisol concentrations are associated with lower BMI and fat mass, and are related to an increased frequency of cortisol secretory bursts and a longer cortisol half-life (81). Weight gain leads to a significant decrease in cortisol burst frequency. Higher cortisol concentrations in AN are associated with lower levels of markers of bone formation and lower bone density measures (81), consistent with the known deleterious effects of high cortisol levels on bone.

Lower Levels of Insulin and Amylin

Insulin levels are low in AN associated with low glucose levels (48). This is the expected physiological response to a state of low energy availability and allows increased glycogenolysis, gluconeogenesis and lipolysis to maintain euglycemia despite reduced energy stores. Insulin has anabolic effects on bone, and low insulin levels predict lower bone density in AN (48). Amylin is secreted by the pancreatic beta cells in an equimolar concentration as insulin, and lower amylin levels have also been associated with lower bone density in AN (82).

Alterations in Ghrelin and PYY

Ghrelin is an orexigenic hormone secreted by the oxyntic cells of the stomach (83), and levels of ghrelin are highest immediately before a meal and decrease following food intake. Ghrelin is present in acylated and desacylated forms, and its acylated form is believed to be the active component (84), particularly for its appetite stimulating effects. In addition, ghrelin is a GH and ACTH secretagogue (85), and both acylated and desacylated forms inhibit gonadotropin secretion (86, 87). Ghrelin receptors are present on osteoblasts, suggesting an effect of ghrelin on osteoblastic activity (88). In addition, ghrelin has been linked to net energy availability, and its levels are associated inversely with resting energy expenditure and fat mass (76). Adolescents and adults with AN have higher ghrelin levels than normal-weight controls in association with lower fat mass, and increased ghrelin secretion is consequent to increased secretory burst mass and total pulsatile secretion (76). Increased ghrelin secretion in AN is likely a physiological and adaptive response to increase food intake, and may also drive increases in GH and ACTH and decreases in pulsatile gonadotropin secretion. Our studies indicate that ghrelin levels are associated positively with bone density in normal-weight controls but not in girls with AN, suggestive of ghrelin resistance in bone (76).

PYY is an anorexigenic hormone that is secreted by the L-cells of the gut. Its levels peak following food intake and induce post-prandial satiety, and like ghrelin, an inverse association has been reported between PYY levels and fat mass across the nutritional spectrum (89, 90). In addition, PYY may impact gonadotropin secretion (91), and high PYY levels have a deleterious effect on bone in rodent models (92). Animal studies have also shown that the Y2 receptor knockout mouse has increased trabecular bone mass (93). Girls with AN have higher PYY levels than normal-weight controls associated with lower fat mass, and levels decrease following weight gain (89). We have also shown that higher PYY levels are associated with lower levels of surrogate markers of bone turnover in adolescents with AN (89), and with lower bone density at the spine and hip in adults with AN (94). In contrast to most hormonal changes in AN that are adaptive to the state of low energy availability, the anorexigenic effect of high PYY levels argue against an adaptive role for this hormone.

Low Levels of Oxytocin

Oxytocin has anabolic effects on bone, as demonstrated in animal models (95). Women with AN have lower peripheral serum levels of pooled overnight oxytocin than normal-weight controls, associated with lower fat mass and with lower measures of bone density (96).

Impact of nutrient intake on bone

Low weight in AN is consequent to marked reductions in caloric intake (97, 98). Percent calories consumed as fats is significantly lower in girls with AN than in normal-weight controls, while percent calories consumed as carbohydrates and proteins is higher. Decreased fat intake is associated with lower fat mass, lower levels of insulin, IGF-1 and leptin, and higher levels of ghrelin, whereas higher carbohydrate intake is associated with increased adiponectin levels (98). Each of these hormones has been implicated as a contributor to low bone density in AN. Fiber intake in higher in AN than controls, and may impair absorption of micronutrients. Additionally, girls with the higher fiber intake have lower body fat mass (98). Of note, although dietary intake of minerals and vitamins does not differ from controls, girls with AN tend to consume a large amount of supplements. As a consequence, the total intake (from diet and supplements) of minerals including calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc and potassium, and of vitamins including A,D, K and most B vitamins is often higher in girls and women with AN than in a normal-weight control population (19, 97, 98). Although both calcium and vitamin D are important determinants of bone mineral content in healthy children, intake of these micronutrients does not correlate with measures of bone density in AN, likely because the deleterious effects of associated body composition and hormonal changes in AN ‘trump’ the beneficial effects of calcium and vitamin D supplements. Bioavailability of oral vitamin D does not differ in girls and young women with AN compared with controls (99), and vitamin D levels are often higher in AN than controls (17, 99).

Monitoring and Management of Low Bone Density in Anorexia Nervosa

Serial bone density assessment is necessary to determine trends in bone density over time, and is particularly important in adolescents and adults with AN with persistent low weight, a prolonged duration of amenorrhea and delayed menarche. We recommend bone density testing using DXA annually in girls and women with AN, particularly in the absence of weight gain and resumption of menses over time.

Calcium and vitamin D status should be optimized, but with the recognition that mere supplementation with calcium and vitamin D will not improve bone density measures in AN (19, 65). As indicated above, girls and women with AN typically consume more calcium and vitamin D than controls (97, 98), primarily through increased use of supplements, and vitamin D levels are higher in girls with AN than in normal-weight controls (17). Nevertheless, it is important to maintain 25-hyrdoxy vitamin D levels above 30 ng/ml (75 nmol/L). The best strategy to improve bone status in AN is weight gain and resumption of menses. However, this can be difficult to attain and sustain, and relapses are common. There may thus be a role for physiologic estrogen replacement using transdermal estradiol (17), particularly in adolescent girls with AN who are amenorrheic with decreases in bone density over time. Adolescents are particularly worrisome given that the teenage years are a very narrow window in time during which to optimize bone accrual, and deficits incurred during these years may be permanent. Our group has reported a significant increase in bone density at the spine and hip using the 100 mcg transdermal estradiol patch twice weekly with cyclic progesterone given for 10 days of every month (17).

Preliminary data suggest that a bone anabolic agent given with estrogen (such as rhIGF-1) may be beneficial for bone accrual (78, 79), however, more studies are necessary to confirm these effects. Studies are also ongoing with teriparatide in older adult women with AN as low levels of bone formation markers in this group suggest that an anabolic agent might be efficacious.

Bisphosphonates do not increase spine bone density in adolescents with AN (100), likely because these agents suppress bone turnover, and adolescents with AN are already in a state of reduced bone turnover compared with controls (16, 17). Further suppressing resorption may thus not be an optimal strategy in an adolescent population, which should typically demonstrate increased bone turnover. In contrast to adolescents, one randomized controlled trial has demonstrated an increase in spine and hip bone density measures in adults with AN using risedronate (35 mg) once a week for a year, associated with a decrease in bone turnover markers (70). Adults with AN have increased bone resorption unlike adolescents, which may explain why bisphosphonates are more effective in this older age group. Given the very long half-life of bisphosphonates and their potential teratogenicity, it is essential to carefully evaluate the need for this therapy, and to counsel women on such medications regarding contraceptive measures for the duration of therapy and beyond.

We recommend considering pharmacological therapy in adolescent girls and women with AN who have low bone density (Z-scores of ≤ −2) with a clinically significant fracture history and a lack of response to concentrated efforts at weight and menses restoration. A lack of response includes a further deterioration of bone density measures during follow-up, or occurrence of new fractures. One may also consider pharmacological therapy in adolescent girls with low bone density without a clinically significant fracture history who demonstrate a lack of response to non-pharmacological measures. This is because losing the window of the adolescent years for peak bone mass accrual may result in deficits that persist throughout life and may be difficult to recover subsequently. While options for pharmacological therapy in adolescents with AN are limited, positive results from the study of physiologic estrogen replacement suggest this may be a viable option. In girls whose bone age is at least 15 years and meet criteria for pharmacological intervention, we recommend using the 100 mcg transdermal 17-beta estradiol patch applied continuously with cyclic oral progesterone (5–10 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate, or 200 mg of micronized progesterone) given for 12 days of every month. Of note, this combination of estrogen-progesterone does not have proven contraceptive efficacy, and thus contraceptive needs of patients need to be considered. It is important to screen for contraindications to estrogen use, and to consult with a hematologist in those with a personal or family history of thrombophilic disorders. At this time, we do not recommend use of testosterone, rhIGF-1, bisphosphonates, denosumab or teriparatide in adolescents with AN.

Although bisphosphonates may be effective in increasing bone density in adult women with AN, we do not recommend these medications in women of child-bearing age given their very long half life and teratogenic potential, except (i) in research trials under careful monitoring, and (ii) when these women meet criteria for pharmacological therapy, but do not respond to estrogen-progesterone replacement, or have contraindications to hormone replacement. Even in such situations, it is essential to counsel these women at length regarding the teratogenic potential of these medications. RhIGF-1, denosumab and teriparatide are still in the experimental realm.

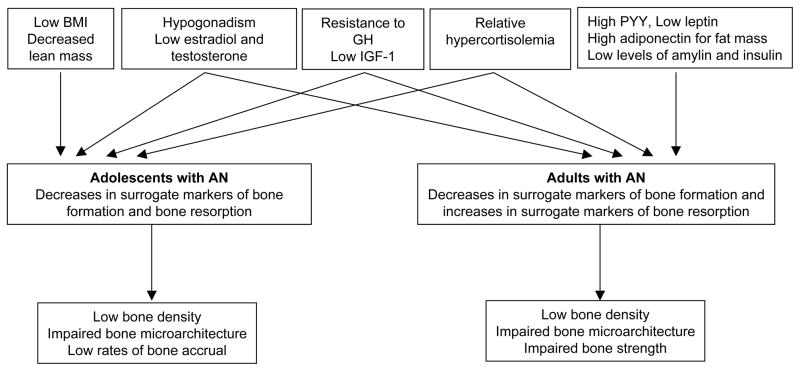

Summary

AN is a condition characterized by marked reductions in areal and volumetric bone mineral density and impaired bone microarchitecture, as well as increased fractures. Changes in bone metabolism in AN are related to alterations in various endocrine axes subsequent to reductions in energy availability and fat mass. These endocrine changes include hypogonadism, a state of acquired GH resistance with low IGF-1 levels, relative hypercortisolemia, low levels of leptin, insulin, amylin and oxytocin, and increased levels of ghrelin, PYY and adiponectin (Figure 3). It is essential to optimize weight gain and consequent menses resumption in this population. Weight gain is associated with increases in fat and lean mass, and an improvement in many endocrine axes. However, the disease may be chronic and in weight recovered patients, relapses may occur. Therefore, strategies to maximize bone accrual in adolescents and improving bone mass in adolescents and adults are critical. Therapeutic strategies include use of transdermal estradiol in selected patients, particularly in adolescents with low bone density demonstrating a decrease in bone density Z-scores over time, as well as in other high risk individuals. Experimental therapies under study include rhIGF-1 in combination with anti-resorptive agents, and teriparatide in adults.

Figure 3.

Pathophysiology contributing to impaired bone metabolism in adolescents and adults with anorexia nervosa (AN); GH: growth hormone, IGF-1: insulin like growth factor-1, PYY: peptide YY. From Misra and Klibanski. Current Opinion in Endocrinology, Diabetes & Obesity 2011, 18:376–382. Copyright © 2011 Wolters Kluwer Health | Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 1752-296X

OBESITY

Although data for bone metabolism in obesity are very limited compared to those available for AN, recent studies have demonstrated that obesity may also have deleterious effects on bone with an increased risk for fracture. This section will discuss determinants of bone metabolism in obese individuals, and the impact of adipose tissue on bone in obesity.

Bone Density and Fractures

Although increased body weight is typically associated with increased bone density, it is a high risk condition for fractures in both children and adults (2–5). Possible mechanisms underlying this increased fracture risk include lower lean mass relative to fat mass, greater kinetic energy of impact subsequent to increased weight in case of a fall (101), and effects of fat distribution on bone structure.

Impact of Body Composition on Bone

Compartment Specific Fat Distribution

Visceral adiposity has been associated with lower bone density measures within obese individuals. In one study, we observed lower bone density in obese adolescent girls whose ratio of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) to subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) was above the median compared to those whose ratio of VAT/SAT was below the median, even when bone density measures did not differ from a normal-weight control population (102). Additionally, VAT was a negative predictor of spine and whole body bone density measures after controlling for subcutaneous fat. Similar data have been reported in healthy young women 15–25 years old, with SAT being noted to be beneficial to bone structure and strength, and VAT being deleterious to bone (103). In addition, greater VAT correlates inversely with bone density in obese premenopausal women independent of age and BMI, whereas muscle mass is a positive determinant of bone density (104). Interestingly, this study found strong inverse associations of IGF-1 with VAT, and positive associations with bone density, suggesting that low IGF-1 may be a mediator of the deleterious effects of VAT on bone. Similarly, obese adult men with increased VAT have impaired bone mechanical properties compared to men who have decreased VAT, even when BMI does not differ (105).

Marrow Adipose Tissue and Brown Adipose Tissue

In adult premenopausal women with obesity, greater vertebral marrow fat has been associated with greater VAT and with lower trabecular bone density (9). In addition, inverse associations have been reported of IGF-1 with marrow adipose tissue (independent of VAT) (9). Similarly, in obese men, bone marrow fat is inversely associated with cortical bone parameters (105). Data are limited at this time regarding brown fat in obese individuals. Scientists have speculated that induction of brown adipogenesis, either through cold or sympathetic activation, may increase energy consumption and serve as a potential therapeutic strategy for obesity.

Effects of adipocytokines and hormones regulated by fat mass on bone metabolism

Nutrient Intake

Although vitamin D levels are typically low in obesity from increased sequestration in adipose tissue depots, data do not indicate associations of low vitamin D levels with lower bone density or impaired structure in obese women (104). Interestingly, recent rodent studies have demonstrated that a high fat diet and hyperlipidemia are associated with decreased osteogenesis and increased bone resorption, both of which blunt the positive effects of weight on bone (106–108). These mice have with decreased bone trabecular volume, number and connectivity, and increased trabecular separation (106–108). Increased osteoclastogenesis in these mice may be mediated by increased T-lymphocyte expression of inflammatory and osteoclastogenic cytokines such as RANKL, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-γ (108).

Adipocytokines

Obesity is typically associated with high leptin and low adiponectin levels, both of which should have a positive impact on bone. However, this is also a state of low grade inflammation with increased levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines secreted from adipose tissue, such as IL-6, TNF-α, E-selectin and sICAM (109). Cytokines such as IL-6 and TNF-α can activate osteoclastic bone resorption, and our studies have demonstrated that obese adolescent girls with higher levels of E-selectin and sICAM have lower measures of bone density (109). These associations hold even after controlling for VAT, suggesting that this pro-inflammatory state is deleterious to bone.

Hormones Regulated by Energy Status

At least one study found no associations of gonadal hormones (estradiol, testosterone and free testosterone) with bone density and structure in obese premenopausal women (104). Obese individuals secrete lower concentrations of GH than normal-weight individuals, and this has been reported in both adolescents (110) and in adults (111) using GH stimulation testing. In adults, those with greater trunk fat have higher 24-hour mean GH concentrations, GH pulse amplitude and basal GH secretion than those with lower trunk fat (112), and truncal fat predicts GH levels independent of total fat and BMI. However, IGF-1 levels are variably reported to be unchanged, high or low in obesity. Lower IGF-1 levels in obese women are associated inversely with VAT and marrow fat, and positively with bone density measures and surrogate markers of bone formation (104).

Additionally, cortisol levels have been reported to be both low or high in obesity, insulin levels are high, and ghrelin and PYY levels are lower than in controls (90, 110, 113, 114). High cortisol and low ghrelin levels would be expected to be deleterious to bone, whereas high insulin and low PYY levels should have a positive impact on bone metabolism. Further studies are necessary to determine the impact of these hormonal alterations on bone in adults and adolescents with obesity.

Effects of Significant Weight Loss (Bariatric Surgery)

Studies thus far have reported decreases in bone density with bariatric surgery in children (115) and adults (116, 117), which may at least partly be an artifact of decreased body size following weight loss (118, 119). Weight loss surgery primarily affects sites of mostly cortical bone (whole body, total hip and femoral neck) (120), while data regarding trabecular sites remain conflicting (117, 121, 122). Bone turnover increases post-surgery, and is likely consequent to expected changes in gut peptides and the hypercatabolic state. GLP-1 and GIP are bone anabolic incretins, and increases in postprandial GLP-1 and GIP following bariatric surgery may increase bone formation. In fact, an increase in bone formation markers has been reported following weight loss surgery in adults (123, 124). However, bone resorption markers also increase (123, 124), which may reflect (i) a coupling of bone turnover, (ii) an increase in osteoclastic bone resorption subsequent to increased inflammatory cytokines (63) from the acute catabolic state following surgery, or (iii) increased PTH from vitamin D malabsorption. The impact of bariatric surgery on bone in the longer term remains to be examined. It is not known yet whether an improvement in regional fat distribution following surgery has a long-term beneficial effect on bone

Summary

More studies are necessary to clarify the impact of compartment specific fat mass on bone density, structure and strength in obese individuals, and the impact of changes in marrow and brown adipose tissue on bone in this population. In the absence of further data, recommendations are difficult regarding who should be assessed for bone status and possible therapeutic options in those with fractures. At this time, we recommend that management of fractures in obesity be individualized.

CONCLUSION

Anorexia nervosa and obesity are disorders that span the nutritional spectrum, and are characterized respectively by marked reductions versus increases in body fat content. These conditions are also associated with classic compartment specific alterations in adiposity, which then impact bone. The effect of adipose tissue on bone is likely mediated by adipocytokines and other hormones that may be regulated by body fat content. More research is necessary to comprehensively assess the impact of these hormones and cytokines independent of each other and of body composition.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: NIH Grant Numbers 1 R01 HD060827, 5 UL1 RR025758 and 2 RO1 DK062249.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report

Bibliography

- 1.Lucas AR, Melton LJ, 3rd, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM. Long-term fracture risk among women with anorexia nervosa: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:972–7. doi: 10.4065/74.10.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goulding A, Jones IE, Taylor RW, Williams SM, Manning PJ. Bone mineral density and body composition in boys with distal forearm fractures: a dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry study. J Pediatr. 2001;139:509–15. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2001.116297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pollock NK, Laing EM, Hamrick MW, Baile CA, Hall DB, Lewis RD. Bone and fat relationships in postadolescent black females: a pQCT study. Osteoporos Int. 2010;22:655–65. doi: 10.1007/s00198-010-1266-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von Muhlen D, Safii S, Jassal SK, Svartberg J, Barrett-Connor E. Associations between the metabolic syndrome and bone health in older men and women: the Rancho Bernardo Study. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:1337–44. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0385-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beck TJ, Petit MA, Wu G, LeBoff MS, Cauley JA, Chen Z. Does obesity really make the femur stronger? BMD, geometry, and fracture incidence in the women’s health initiative-observational study. J Bone Miner Res. 2009;24:1369–79. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.090307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdallah BM, Ding M, Jensen CH, Ditzel N, Flyvbjerg A, Jensen TG, Dagnaes-Hansen F, Gasser JA, Kassem M. Dlk1/FA1 is a novel endocrine regulator of bone and fat mass and its serum level is modulated by growth hormone. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3111–21. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosen CJ, Bouxsein ML. Mechanisms of disease: is osteoporosis the obesity of bone? Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2006;2:35–43. doi: 10.1038/ncprheum0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, Misra M, Torriani M, Thomas BJ, Ghomi RH, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A. Increased Bone Marrow Fat in Anorexia Nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bredella MA, Torriani M, Ghomi RH, Thomas BJ, Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Vertebral bone marrow fat is positively associated with visceral fat and inversely associated with IGF-1 in obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:49–53. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lucas AR, Beard CM, O’Fallon WM, Kurland LT. 50-year trends in the incidence of anorexia nervosa in Rochester, Minn: a population-based study. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:917–22. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.7.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Misra M, Aggarwal A, Miller KK, Almazan C, Worley M, Soyka LA, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Effects of anorexia nervosa on clinical, hematologic, biochemical, and bone density parameters in community-dwelling adolescent girls. Pediatrics. 2004;114:1574–83. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinspoon S, Thomas E, Pitts S, Gross E, Mickley D, Miller K, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Prevalence and predictive factors for regional osteopenia in women with anorexia nervosa. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:790–4. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-10-200011210-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castro J, Toro J, Lazaro L, Pons F, Halperin I. Bone mineral density in male adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:613–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200205000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misra M, Katzman DK, Cord J, Manning SJ, Mendes N, Herzog DB, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Bone metabolism in adolescent boys with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3029–36. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misra M, Prabhakaran R, Miller KK, Goldstein MA, Mickley D, Clauss L, Lockhart P, Cord J, Herzog DB, Katzman DK, Klibanski A. Weight gain and restoration of menses as predictors of bone mineral density change in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa-1. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:1231–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Misra M, Soyka LA, Miller KK, Herzog DB, Grinspoon S, De Chen D, Neubauer G, Klibanski A. Serum osteoprotegerin in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3816–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Misra M, Katzman D, Miller KK, Mendes N, Snelgrove D, Russell M, Goldstein MA, Ebrahimi S, Clauss L, Weigel T, Mickley D, Schoenfeld DA, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Physiologic estrogen replacement increases bone density in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2430–8. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grinspoon S, Baum H, Lee K, Anderson E, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Effects of short-term recombinant human insulin-like growth factor I administration on bone turnover in osteopenic women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3864–70. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Soyka LA, Misra M, Frenchman A, Miller KK, Grinspoon S, Schoenfeld DA, Klibanski A. Abnormal bone mineral accrual in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4177–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-011889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Faje AT, Karim L, Taylor A, Lee H, Miller KK, Mendes N, Meenaghan E, Goldstein MA, Bouxsein ML, Misra M, Klibanski A. Adolescent Girls With Anorexia Nervosa Have Impaired Cortical and Trabecular Microarchitecture and Lower Estimated Bone Strength at the Distal Radius. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013 doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-4153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bredella MA, Misra M, Miller KK, Madisch I, Sarwar A, Cheung A, Klibanski A, Gupta R. Distal radius in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa: trabecular structure analysis with high-resolution flat-panel volume CT. Radiology. 2008;249:938–46. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2492080173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Milos G, Spindler A, Ruegsegger P, Seifert B, Muhlebach S, Uebelhart D, Hauselmann HJ. Cortical and trabecular bone density and structure in anorexia nervosa. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:783–90. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1759-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawson EA, Miller KK, Bredella MA, Phan C, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosenblum L, Donoho D, Gupta R, Klibanski A. Hormone predictors of abnormal bone microarchitecture in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2010;46:458–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Faje A, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, Katzman DK, Ebrahimi S, Lee H, Mendes N, Snelgrove D, Meenaghan E, Misra M, Klibanski A. Fracture Risk and Areal Bone Mineral Density in Adolescent Girls with Anorexia Nervosa. Endocrine Society Meeting 2013. 2013 doi: 10.1002/eat.22248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hind K, Gannon L, Whatley E, Cooke C. Sexual dimorphism of femoral neck cross-sectional bone geometry in athletes and non-athletes: a hip structural analysis study. J Bone Miner Metab. 2012;30:454–60. doi: 10.1007/s00774-011-0339-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Misra M, Katzman DK, Clarke H, Snelgrove D, Brigham K, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Hip Structural Analysis in Adolescent Boys with Anorexia Nervosa and Controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013 doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Faulkner KG, Wacker WK, Barden HS, Simonelli C, Burke PK, Ragi S, Del Rio L. Femur strength index predicts hip fracture independent of bone density and hip axis length. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17:593–9. doi: 10.1007/s00198-005-0019-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leslie WD, Pahlavan PS, Tsang JF, Lix LM. Prediction of hip and other osteoporotic fractures from hip geometry in a large clinical cohort. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:1767–74. doi: 10.1007/s00198-009-0874-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaptoge S, Beck TJ, Reeve J, Stone KL, Hillier TA, Cauley JA, Cummings SR. Prediction of incident hip fracture risk by femur geometry variables measured by hip structural analysis in the study of osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23:1892–904. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alwis G, Karlsson C, Stenevi-Lundgren S, Rosengren BE, Karlsson MK. Femoral neck bone strength estimated by hip structural analysis (HSA) in Swedish Caucasians aged 6–90 years. Calcif Tissue Int. 2012;90:174–85. doi: 10.1007/s00223-011-9566-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackowski SA, Kontulainen SA, Cooper DM, Lanovaz JL, Baxter-Jones AD. The timing of BMD and geometric adaptation at the proximal femur from childhood to early adulthood in males and females: a longitudinal study. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:2753–61. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller KK, Lee EE, Lawson EA, Misra M, Minihan J, Grinspoon SK, Gleysteen S, Mickley D, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Determinants of skeletal loss and recovery in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:2931–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wren TA, Chung SA, Dorey FJ, Bluml S, Adams GB, Gilsanz V. Bone marrow fat is inversely related to cortical bone in young and old subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:782–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-1922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Di Iorgi N, Mo AO, Grimm K, Wren TA, Dorey F, Gilsanz V. Bone acquisition in healthy young females is reciprocally related to marrow adiposity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2977–82. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Di Iorgi N, Rosol M, Mittelman SD, Gilsanz V. Reciprocal relation between marrow adiposity and the amount of bone in the axial and appendicular skeleton of young adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2281–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shen W, Chen J, Gantz M, Punyanitya M, Heymsfield SB, Gallagher D, Albu J, Engelson E, Kotler D, Pi-Sunyer X, Gilsanz V. MRI-measured pelvic bone marrow adipose tissue is inversely related to DXA-measured bone mineral in younger and older adults. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2012;66:983–8. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2012.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosen CJ, Clemmons DR, Breggia A, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Preadipocyte factor-1 is associated with marrow adiposity and bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:407–13. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Freedman L, Thomas BJ, Breggia A, Meenaghan E, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A. Marrow fat and preadipocyte factor-1 levels decrease with recovery in women with anorexia nervosa. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:1864–71. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.1640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rahman S, Lu Y, Czernik PJ, Rosen CJ, Enerback S, Lecka-Czernik B. Inducible Brown Adipose Tissue, or Beige Fat, Is Anabolic for the Skeleton. Endocrinology. 2013 doi: 10.1210/en.2012-2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ponrartana S, Aggabao PC, Hu HH, Aldrovandi GM, Wren TA, Gilsanz V. Brown adipose tissue and its relationship to bone structure in pediatric patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:2693–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee P, Brychta RJ, Collins MT, Linderman J, Smith S, Herscovitch P, Millo C, Chen KY, Celi FS. Cold-activated brown adipose tissue is an independent predictor of higher bone mineral density in women. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:1513–8. doi: 10.1007/s00198-012-2110-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Freedman LM, Calder G, Lee H, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A. Young women with cold-activated brown adipose tissue have higher bone mineral density and lower Pref-1 than women without brown adipose tissue: a study in women with anorexia nervosa, women recovered from anorexia nervosa, and normal-weight women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E584–90. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Lecka-Czernik B, Rosen CJ, Klibanski A. IGFBP-2 is a negative predictor of cold-induced brown fat and bone mineral density in young non-obese women. Bone. 2013;53:336–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, Liu X, Zhao L, Parker KL, Armstrong D, Ducy P, Karsenty G. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111:305–17. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01049-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hamrick MW, Ferrari SL. Leptin and the sympathetic connection of fat to bone. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:905–12. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0487-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grinspoon S, Gulick T, Askari H, Landt M, Lee K, Anderson E, Ma Z, Vignati L, Bowsher R, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Serum leptin levels in women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:3861–3. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.11.8923829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Misra M, Miller KK, Kuo K, Griffin K, Stewart V, Hunter E, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Secretory dynamics of leptin in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and healthy adolescents. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E373–81. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00041.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Misra M, Miller KK, Cord J, Prabhakaran R, Herzog DB, Goldstein M, Katzman DK, Klibanski A. Relationships between serum adipokines, insulin levels, and bone density in girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2046–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sienkiewicz E, Magkos F, Aronis KN, Brinkoetter M, Chamberland JP, Chou S, Arampatzi KM, Gao C, Koniaris A, Mantzoros CS. Long-term metreleptin treatment increases bone mineral density and content at the lumbar spine of lean hypoleptinemic women. Metabolism. 2011;60:1211–21. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Welt CK, Chan JL, Bullen J, Murphy R, Smith P, DePaoli AM, Karalis A, Mantzoros CS. Recombinant Human Leptin in Women with Hypothalamic Amenorrhea. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:987–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jurimae J, Rembel K, Jurimae T, Rehand M. Adiponectin is associated with bone mineral density in perimenopausal women. Horm Metab Res. 2005;37:297–302. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lenchik L, Register TC, Hsu FC, Lohman K, Nicklas BJ, Freedman BI, Langefeld CD, Carr JJ, Bowden DW. Adiponectin as a novel determinant of bone mineral density and visceral fat. Bone. 2003;33:646–51. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(03)00237-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo XH, Guo LJ, Xie H, Yuan LQ, Wu XP, Zhou HD, Liao EY. Adiponectin stimulates RANKL and inhibits OPG expression in human osteoblasts through the MAPK signaling pathway. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:1648–56. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.060707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shinoda Y, Yamaguchi M, Ogata N, Akune T, Kubota N, Yamauchi T, Terauchi Y, Kadowaki T, Takeuchi Y, Fukumoto S, Ikeda T, Hoshi K, Chung UI, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H. Regulation of bone formation by adiponectin through autocrine/paracrine and endocrine pathways. J Cell Biochem. 2006;99:196–208. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Housova J, Anderlova K, Krizova J, Haluzikova D, Kremen J, Kumstyrova T, Papezova H, Haluzik M. Serum adiponectin and resistin concentrations in patients with restrictive and binge/purge form of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1366–70. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iwahashi H, Funahashi T, Kurokawa N, Sayama K, Fukuda E, Okita K, Imagawa A, Yamagata K, Shimomura I, Miyagawa JI, Matsuzawa Y. Plasma adiponectin levels in women with anorexia nervosa. Horm Metab Res. 2003;35:537–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-42655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pannacciulli N, Vettor R, Milan G, Granzotto M, Catucci A, Federspil G, De Giacomo P, Giorgino R, De Pergola G. Anorexia nervosa is characterized by increased adiponectin plasma levels and reduced nonoxidative glucose metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1748–52. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dostalova I, Smitka K, Papezova H, Kvasnickova H, Nedvidkova J. The role of adiponectin in increased insulin sensitivity of patients with anorexia nervosa. Vnitr Lek. 2006;52:887–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Misra M, Miller KK, Tsai P, Stewart V, End A, Freed N, Herzog DB, Goldstein M, Riggs S, Klibanski A. Uncoupling of cardiovascular risk markers in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr. 2006;149:763–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakai Y, Hamagaki S, Takagi R, Taniguchi A, Kurimoto F. Plasma concentrations of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and soluble TNF receptors in patients with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1226–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.4.5589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boyar RM, Katz J, Finkelstein JW, Kapen S, Weiner H, Weitzman ED, Hellman L. Anorexia nervosa. Immaturity of the 24-hour luteinizing hormone secretory pattern. N Engl J Med. 1974;291:861–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197410242911701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Riggs B. The mechanisms of estrogen regulation of bone resorption. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1203–4. doi: 10.1172/JCI11468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Riggs BL, Khosla S, Melton LJ., III Sex Steroids and the Construction and Conservation of the Adult Skeleton. Endocr Rev. 2002;23:279–302. doi: 10.1210/edrv.23.3.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mirza FS, Padhi ID, Raisz LG, Lorenzo JA. Serum sclerostin levels negatively correlate with parathyroid hormone levels and free estrogen index in postmenopausal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1991–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Klibanski A, Biller B, Schoenfeld D, Herzog D, Saxe V. The effects of estrogen administration on trabecular bone loss in young women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:898–904. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.3.7883849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Strokosch GR, Friedman AJ, Wu SC, Kamin M. Effects of an oral contraceptive (norgestimate/ethinyl estradiol) on bone mineral density in adolescent females with anorexia nervosa: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Adolesc Health. 2006;39:819–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Katzman DK, Miller KK, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, Mendes N, Klibanski A, Misra M. Sclerostin levels and bone turnover markers in adolescents with anorexia nervosa and healthy adolescent girls. Bone. 2012;51:474–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Faje AT, Fazeli PK, Katzman D, Miller KK, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, Mendes N, Misra M, Klibanski A. Inhibition of Pref-1 (Preadipocyte Factor 1) by Estradiol in Adolescent Girls with Anorexia Nervosa is Associated with Improvement in Lumbar Bone Mineral Density. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013 doi: 10.1111/cen.12144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miller KK, Grieco KA, Klibanski A. Testosterone administration in women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1428–33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller KK, Meenaghan E, Lawson EA, Misra M, Gleysteen S, Schoenfeld D, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Effects of risedronate and low-dose transdermal testosterone on bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2081–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gordon CM, Goodman E, Emans SJ, Grace E, Becker KA, Rosen CJ, Gundberg CM, Leboff MS. Physiologic regulators of bone turnover in young women with anorexia nervosa. J Pediatr. 2002;141:64–70. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.125003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Divasta AD, Feldman HA, Giancaterino C, Rosen CJ, Leboff MS, Gordon CM. The effect of gonadal and adrenal steroid therapy on skeletal health in adolescents and young women with anorexia nervosa. Metabolism. 2012;61:1010–20. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2011.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gordon CM, Grace E, Emans SJ, Feldman HA, Goodman E, Becker KA, Rosen CJ, Gundberg CM, LeBoff MS. Effects of Oral Dehydroepiandrosterone on Bone Density in Young Women with Anorexia Nervosa: A Randomized Trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4935–41. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-020545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Counts D, Gwirtsman H, Carlsson L, Lesem M, Cutler G. The effect of anorexia nervosa and refeeding on growth hormone-binding protein, the insulin-like growth factors (IGFs), and the IGF-binding proteins. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;75:762–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.75.3.1381372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Misra M, Miller K, Bjornson J, Hackman A, Aggarwal A, Chung J, Ott M, Herzog D, Johnson M, Klibanski A. Alterations in growth hormone secretory dynamics in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and effects on bone metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5615–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Misra M, Miller K, Kuo K, Griffin K, Stewart V, Hunter E, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Secretory Dynamics of Ghrelin in Adolescent Girls with Anorexia Nervosa and Healthy Adolescents. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;289:E347–56. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00615.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fazeli PK, Lawson EA, Prabhakaran R, Miller KK, Donoho DA, Clemmons DR, Herzog DB, Misra M, Klibanski A. Effects of recombinant human growth hormone in anorexia nervosa: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4889–97. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Misra M, McGrane J, Miller KK, Goldstein MA, Ebrahimi S, Weigel T, Klibanski A. Effects of rhIGF-1 administration on surrogate markers of bone turnover in adolescents with anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2009;45:493–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Grinspoon S, Thomas L, Miller K, Herzog D, Klibanski A. Effects of recombinant human IGF-I and oral contraceptive administration on bone density in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:2883–91. doi: 10.1210/jcem.87.6.8574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lawson EA, Misra M, Meenaghan E, Rosenblum L, Donoho DA, Herzog D, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Adrenal glucocorticoid and androgen precursor dissociation in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:1367–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Misra M, Miller KK, Almazan C, Ramaswamy K, Lapcharoensap W, Worley M, Neubauer G, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Alterations in cortisol secretory dynamics in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and effects on bone metabolism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:4972–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wojcik MH, Meenaghan E, Lawson EA, Misra M, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Reduced amylin levels are associated with low bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2010;46:796–800. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nakazato M, Murakami N, Date Y, Kojima M, Matsuo H, Kangawa K, Matsukura S. A role for ghrelin in the central regulation of feeding. Nature. 2001;409:194–8. doi: 10.1038/35051587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Broglio F, Benso A, Gottero C, Prodam F, Gauna C, Filtri L, Arvat E, van der Lely A, Deghenghi R, Ghigo E. Non-acylated ghrelin does not possess the pituitaric and pancreatic endocrine activity of acylated ghrelin in humans. J Endocrinol Invest. 2003;26:192–6. doi: 10.1007/BF03345156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alvarez-Castro P, Isidro M, Garcia-Buela J, Leal-Cerro A, Broglio F, Tassone F, Ghigo E, Dieguez C, Casanueva F, Cordido F. Marked GH secretion after ghrelin alone or combined with GH-releasing hormone (GHRH) in obese patients. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2004;61:250–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2004.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kluge M. Ghrelin suppresses secretion of gonadotropins in women. Reprod Sci. 2012;19:NP3. doi: 10.1177/1933719112459242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vulliemoz NR, Xiao E, Xia-Zhang L, Germond M, Rivier J, Ferin M. Decrease in Luteinizing Hormone Pulse Frequency during a Five-Hour Peripheral Ghrelin Infusion in the Ovariectomized Rhesus Monkey. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:5718–23. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fukushima N, Hanada R, Teranishi H, Fukue Y, Tachibana T, Ishikawa H, Takeda S, Takeuchi Y, Fukumoto S, Kangawa K, Nagata K, Kojima M. Ghrelin directly regulates bone formation. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:790–8. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.041237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Misra M, Miller KK, Tsai P, Gallagher K, Lin A, Lee N, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Elevated peptide YY levels in adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:1027–33. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Misra M, Tsai PM, Mendes N, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Increased carbohydrate induced ghrelin secretion in obese vs. normal-weight adolescent girls. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:1689–95. doi: 10.1038/oby.2009.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fernandez-Fernandez R, Aguilar E, Tena-Sempere M, Pinilla L. Effects of polypeptide YY(3–36) upon luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone and gonadotropin secretion in prepubertal rats: in vivo and in vitro studies. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1403–10. doi: 10.1210/en.2004-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wong IP, Driessler F, Khor EC, Shi YC, Hormer B, Nguyen AD, Enriquez RF, Eisman JA, Sainsbury A, Herzog H, Baldock PA. Peptide YY regulates bone remodeling in mice: a link between gut and skeletal biology. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40038. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Baldock PA, Sainsbury A, Couzens M, Enriquez RF, Thomas GP, Gardiner EM, Herzog H. Hypothalamic Y2 receptors regulate bone formation. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:915–21. doi: 10.1172/JCI14588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Utz AL, Lawson EA, Misra M, Mickley D, Gleysteen S, Herzog DB, Klibanski A, Miller KK. Peptide YY (PYY) levels and bone mineral density (BMD) in women with anorexia nervosa. Bone. 2008;43:135–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tamma R, Colaianni G, Zhu LL, DiBenedetto A, Greco G, Montemurro G, Patano N, Strippoli M, Vergari R, Mancini L, Colucci S, Grano M, Faccio R, Liu X, Li J, Usmani S, Bachar M, Bab I, Nishimori K, Young LJ, Buettner C, Iqbal J, Sun L, Zaidi M, Zallone A. Oxytocin is an anabolic bone hormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7149–54. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901890106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lawson EA, Donoho DA, Blum JI, Meenaghan EM, Misra M, Herzog DB, Sluss PM, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Decreased nocturnal oxytocin levels in anorexia nervosa are associated with low bone mineral density and fat mass. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1546–51. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hadigan CM, Anderson EJ, Miller KK, Hubbard JL, Herzog DB, Klibanski A, Grinspoon SK. Assessment of macronutrient and micronutrient intake in women with anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28:284–92. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<284::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Misra M, Tsai P, Anderson EJ, Hubbard JL, Gallagher K, Soyka LA, Miller KK, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Nutrient intake in community-dwelling adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa and in healthy adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:698–706. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.4.698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Divasta AD, Feldman HA, Brown JN, Giancaterino C, Holick MF, Gordon CM. Bioavailability of vitamin D in malnourished adolescents with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:2575–80. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Golden NH, Iglesias EA, Jacobson MS, Carey D, Meyer W, Schebendach J, Hertz S, Shenker IR. Alendronate for the treatment of osteopenia in anorexia nervosa: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:3179–85. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ehehalt S, Binder G, Schurr N, Pfaff C, Ranke MB, Schweizer R. The functional muscle-bone unit in obese children - altered bone structure leads to normal strength strain index. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2011;119:321–6. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1277139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Russell M, Mendes N, Miller KK, Rosen CJ, Lee H, Klibanski A, Misra M. Visceral fat is a negative predictor of bone density measures in obese adolescent girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1247–55. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gilsanz V, Chalfant J, Mo AO, Lee DC, Dorey FJ, Mittelman SD. Reciprocal relations of subcutaneous and visceral fat to bone structure and strength. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:3387–93. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bredella MA, Torriani M, Ghomi RH, Thomas BJ, Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Harrington LM, Breggia A, Rosen CJ, Miller KK. Determinants of bone mineral density in obese premenopausal women. Bone. 2011;48:748–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Bredella MA, Lin E, Gerweck AV, Landa MG, Thomas BJ, Torriani M, Bouxsein ML, Miller KK. Determinants of bone microarchitecture and mechanical properties in obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4115–22. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cao JJ, Sun L, Gao H. Diet-induced obesity alters bone remodeling leading to decreased femoral trabecular bone mass in mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1192:292–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Pirih F, Lu J, Ye F, Bezouglaia O, Atti E, Ascenzi MG, Tetradis S, Demer L, Aghaloo T, Tintut Y. Adverse effects of hyperlipidemia on bone regeneration and strength. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:309–18. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Graham LS, Tintut Y, Parhami F, Kitchen CM, Ivanov Y, Tetradis S, Effros RB. Bone density and hyperlipidemia: the T-lymphocyte connection. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2460–9. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Russell M, Bredella M, Tsai P, Mendes N, Miller KK, Klibanski A, Misra M. Relative growth hormone deficiency and cortisol excess are associated with increased cardiovascular risk markers in obese adolescent girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2864–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Misra M, Bredella MA, Tsai P, Mendes N, Miller KK, Klibanski A. Lower growth hormone and higher cortisol are associated with greater visceral adiposity, intramyocellular lipids, and insulin resistance in overweight girls. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E385–92. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00052.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Makimura H, Stanley T, Mun D, You SM, Grinspoon S. The effects of central adiposity on growth hormone (GH) response to GH-releasing hormone-arginine stimulation testing in men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:4254–60. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Miller KK, Biller BM, Lipman JG, Bradwin G, Rifai N, Klibanski A. Truncal adiposity, relative growth hormone deficiency, and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:768–74. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Duclos M, Marquez Pereira P, Barat P, Gatta B, Roger P. Increased cortisol bioavailability, abdominal obesity, and the metabolic syndrome in obese women. Obes Res. 2005;13:1157–66. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Gueugnon C, Mougin F, Nguyen NU, Bouhaddi M, Nicolet-Guenat M, Dumoulin G. Ghrelin and PYY levels in adolescents with severe obesity: effects of weight loss induced by long-term exercise training and modified food habits. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112:1797–805. doi: 10.1007/s00421-011-2154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kaulfers AM, Bean JA, Inge TH, Dolan LM, Kalkwarf HJ. Bone loss in adolescents after bariatric surgery. Pediatrics. 2011;127:e956–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Fleischer J, Stein EM, Bessler M, Della Badia M, Restuccia N, Olivero-Rivera L, McMahon DJ, Silverberg SJ. The decline in hip bone density after gastric bypass surgery is associated with extent of weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:3735–40. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Pugnale N, Giusti V, Suter M, Zysset E, Heraief E, Gaillard RC, Burckhardt P. Bone metabolism and risk of secondary hyperparathyroidism 12 months after gastric banding in obese pre-menopausal women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27:110–6. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Bolotin HH. DXA in vivo BMD methodology: an erroneous and misleading research and clinical gauge of bone mineral status, bone fragility, and bone remodelling. Bone. 2007;41:138–54. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Yu EW, Thomas BJ, Brown JK, Finkelstein JS. Simulated increases in body fat and errors in bone mineral density measurements by DXA and QCT. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27:119–24. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Stein EM, Carrelli A, Young P, Bucovsky M, Zhang C, Schrope B, Bessler M, Zhou B, Wang J, Guo XE, McMahon DJ, Silverberg SJ. Bariatric surgery results in cortical bone loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:541–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-2394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Vilarrasa N, Gomez JM, Elio I, Gomez-Vaquero C, Masdevall C, Pujol J, Virgili N, Burgos R, Sanchez-Santos R, de Gordejuela AG, Soler J. Evaluation of bone disease in morbidly obese women after gastric bypass and risk factors implicated in bone loss. Obes Surg. 2009;19:860–6. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9843-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Valderas JP, Velasco S, Solari S, Liberona Y, Viviani P, Maiz A, Escalona A, Gonzalez G. Increase of bone resorption and the parathyroid hormone in postmenopausal women in the long-term after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1132–8. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9890-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Sinha N, Shieh A, Stein EM, Strain G, Schulman A, Pomp A, Gagner M, Dakin G, Christos P, Bockman RS. Increased PTH and 1. 25(OH)(2)D levels associated with increased markers of bone turnover following bariatric surgery. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19:2388–93. doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Bruno C, Fulford AD, Potts JR, McClintock R, Jones R, Cacucci BM, Gupta CE, Peacock M, Considine RV. Serum markers of bone turnover are increased at six and 18 months after Roux-en-Y bariatric surgery: correlation with the reduction in leptin. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:159–66. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]