Abstract

Objective

To characterize influenza seasonality and identify the best time of the year for vaccination against influenza in tropical and subtropical countries of southern and south-eastern Asia that lie north of the equator.

Methods

Weekly influenza surveillance data for 2006 to 2011 were obtained from Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam. Weekly rates of influenza activity were based on the percentage of all nasopharyngeal samples collected during the year that tested positive for influenza virus or viral nucleic acid on any given week. Monthly positivity rates were then calculated to define annual peaks of influenza activity in each country and across countries.

Findings

Influenza activity peaked between June/July and October in seven countries, three of which showed a second peak in December to February. Countries closer to the equator had year-round circulation without discrete peaks. Viral types and subtypes varied from year to year but not across countries in a given year. The cumulative proportion of specimens that tested positive from June to November was > 60% in Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, the Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam. Thus, these tropical and subtropical countries exhibited earlier influenza activity peaks than temperate climate countries north of the equator.

Conclusion

Most southern and south-eastern Asian countries lying north of the equator should consider vaccinating against influenza from April to June; countries near the equator without a distinct peak in influenza activity can base vaccination timing on local factors.

Résumé

Objectif

Caractériser la saisonnalité de la grippe et identifier le meilleur moment de l'année pour la vaccination contre la grippe dans les pays tropicaux et subtropicaux de l'Asie du Sud et de l'Asie du Sud-Est, qui sont situés au nord de l'équateur.

Méthodes

Les données hebdomadaires de la surveillance de la grippe pour la période allant de 2006 à 2001 ont été obtenues auprès du Bangladesh, du Cambodge, de l'Inde, de la République démocratique populaire lao, de la Malaisie, des Philippines, de Singapour, de la Thaïlande et du Viet Nam. Les taux hebdomadaires de l'activité grippale étaient basés sur le pourcentage de tous les échantillons nasopharyngés collectés au cours de l'année et dont les tests étaient positifs au virus de la grippe ou à l'acide nucléique viral au cours d'une semaine donnée. Les pourcentages de cas positifs mensuels ont été ensuite calculés pour définir les pics annuels de l'activité grippale au sein de chaque pays et entre les pays.

Résultats

L'activité grippale atteint son pic entre les mois de juin/juillet et octobre dans sept pays, parmi lesquels trois pays ont présenté un second pic entre les mois de décembre et février. Les pays proches de l'équateur présentent une circulation continue sans pic distinct. Les types et sous-types viraux varient d'une année à l'autre, mais pas entre les pays au cours d'une année donnée. Le pourcentage cumulatif des prélèvements dont les tests étaient positifs de juin à novembre, était supérieur à 60% au Bangladesh, au Cambodge, en Inde, en République démocratique populaire lao, aux Philippines, en Thaïlande et au Viet Nam. Par conséquent, ces pays tropicaux et subtropicaux ont enregistré plus tôt des pics d'activité grippale que dans les pays à climat tempéré situés au nord de l'équateur.

Conclusion

La plupart des pays de l'Asie du Sud et de l'Asie du Sud-Est, situés au nord de l'équateur, devraient envisager la vaccination contre la grippe pendant la période allant d'avril à juin. Les pays proches de l'équateur sans pic distinct d'activité grippale peuvent baser leur calendrier de vaccination sur leurs facteurs locaux.

Resumen

Objetivo

Describir la estacionalidad de la gripe e identificar el mejor momento del año para llevar a cabo la vacunación contra la gripe en países tropicales y subtropicales del sur y sureste de Asia situados al norte del ecuador.

Métodos

Se obtuvieron los datos semanales de vigilancia de la gripe de los años 2006 a 2011 de Bangladesh, Camboya, India, Indonesia, la República Democrática Popular Lao, Malasia, Filipinas, Singapur, Tailandia y Viet Nam. Las tasas semanales de la actividad de la gripe se basaron en el porcentaje de todas las muestras nasofaríngeas recogidas durante el año que dieron positivo en la prueba del virus de la gripe o del ácido nucleido viral en cualquier semana. Los índices de resultados positivos mensuales se calcularon luego a fin de determinar los picos anuales de la actividad de la gripe en cada uno de los países y entre países.

Resultados

La actividad de la gripe experimentó un aumento entre junio y julio, y octubre en siete países, tres de los cuales mostraron un segundo pico de actividad de diciembre a febrero. Los países más cercanos al ecuador presentaron una circulación durante todo el año sin picos discontinuos. Los tipos y subtipos virales variaron de año en año, pero no entre los países en un año determinado. La proporción acumulada de individuos que dieron positivo de junio a noviembre fue > 60 % en Bangladesh, Camboya, India, la República Democrática Popular Lao, Filipinas, Tailandia y Viet Nam. Así, en estos países tropicales y subtropicales, los picos de actividad de la gripe se produjeron antes que en los países de clima templado al norte de la línea ecuatorial.

Conclusión

La mayoría de los países del sur y sureste asiático situados al norte del ecuador deberían considerar llevar a cabo la vacunación contra la gripe de abril a junio; mientras que los países cercanos al ecuador sin picos marcados en la actividad de la gripe pueden basar la fecha de vacunación en factores locales.

ملخص

الغرض

تحديد خصائص موسمية الأنفلونزا والتعرف على أفضل أوقات السنة للتطعيم ضد الأنفلونزا في البلدان المدارية ودون المدارية في جنوب وجنوب شرق آسيا الواقعة شمال خط الاستواء.

الطريقة

تم الحصول على بيانات الترصد الأسبوعية للأنفلونزا للفترة من 2006 إلى 2011 من بنغلاديش وكمبوديا والهند وإندونيسيا وجمهورية لاو الديمقراطية الشعبية وماليزيا والفلبين وسنغافورة وتايلند وفييت نام. واستندت المعدلات الأسبوعية لنشاط الأنفلونزا على النسبة المئوية لجميع عينات البلعوم الأنفي التي تم جمعها أثناء العام والتي كانت نتائج اختباراتها إيجابية لفيروس الأنفلونزا أو الحمض النووي الفيروسي في أسبوع معين. وتم حساب معدلات الإيجابية الشهرية لتحديد فترات ذروة نشاط الأنفلونزا السنوية في كل بلد وعبر البلدان.

النتائج

بلغ نشاط الأنفلونزا ذروته في الفترة بين حزيران/يونيو / تموز/يوليو وتشرين الأول/أكتوبر في سبعة بلدان، حيث أظهرت ثلاثة منها ذروة ثانية في الفترة من كانون الأول/ديسمبر إلى شباط/فبراير. وشهدت البلدان الأقرب إلى خط الاستواء دوراناً طوال العام دون فترات ذروة منفصلة. واختلفت الأنماط والأنماط الفرعية للفيروس من سنة إلى أخرى، ولكن لم تختلف عبر البلدان في سنة معينة. وكانت النسبة التراكمية للعينات التي كانت نتائج اختباراتها إيجابية من حزيران/يونيو إلى تشرين الثاني/نوفمبر أكبر من 60 % في بنغلاديش وكمبوديا والهند وجمهورية لاو الديمقراطية الشعبية والفلبين وتايلند وفييت نام. ومن ثم، أظهرت هذه البلدان المدارية ودون المدارية فترات ذروة مبكرة لنشاط الأنفلونزا عن البلدان معتدلة المناخ الواقعة شمال خط الاستواء.

الاستنتاج

ينبغي أن تنظر معظم بلدان جنوب وجنوب شرق آسيا الواقعة شمال خط الاستواء في التطعيم ضد الأنفلونزا في الفترة من نيسان/إبريل إلى حزيران/يونيو؛ في حين تستطيع البلدان القريبة من خط الاستواء التي لا تشهد ذروة منفصلة في نشاط الأنفلونزا تحديد توقيت التطعيم على أساس العوامل المحلية.

摘要

目的

表征赤道以北的南亚和东南亚热带和亚热带国家流感季节性特点并确定流感疫苗接种最佳时间。

方法

从孟加拉国、柬埔寨、印度、印度尼西亚、老挝、马来西亚、菲律宾、新加坡、泰国和越南收集2006年至2011年的每周流感监测数据。每周流感活动率基于的是任何给定周测试流感病毒或病毒核酸阳性的一年中收集的鼻咽样本的百分比。然后,计算每月阳性率来定义每个国家和各国之间年流感活动的峰值。

结果

七个国家中,6月/7月和10月之间出现流感活动峰值,其中三个国家在12月至2月出现第二次峰值。靠近赤道的国家长年流感传播,没有不连续的峰值。病毒类型和子类型因年份而异,但在给定年份的各个国家之间没有变化。孟加拉国、柬埔寨、印度、老挝人民民主共和国、菲律宾、泰国和越南6月至11月测试阳性的样本的累积比例> 60%。因此,较之赤道以北温带气候国家,这些热带和亚热带国家出现流感活动峰值更早。

结论

赤道以北的大多数亚洲南部和东南部国家应考虑从4月到6月接种流感疫苗,赤道附近没有出现明显的流感活动峰值的国家可以根据当地因素确定疫苗接种时间。

Резюме

Цель

Охарактеризовать сезонность гриппа и определить лучшее время года для проведения вакцинации против гриппа в тропических и субтропических странах Южной и Юго-Восточной Азии, расположенных к северу от экватора.

Методы

Еженедельные данные эпиднадзора по гриппу с 2006 по 2011 гг. были получены из Бангладеш, Камбоджи, Индии, Индонезии, Лаосской Народно-Демократической Республики, Малайзии, Филиппин, Сингапура, Таиланда и Вьетнама. Недельные показатели активности гриппа вычислялись на основе процента от общего количества всех мазков из носоглотки, собранных в течение года, показавших положительный результат на вирус гриппа или вирусную нуклеиновую кислоту в течение любой данной недели. Затем были рассчитаны месячные показатели позитивности с целью определить ежегодные пики активности гриппа в каждой из стран и во всех странах региона.

Результаты

Активность гриппа достигала своего пика между июнем/июлем и октябрем в семи странах, в трех из которых отмечен второй пик с декабря по февраль. Страны ближе к экватору имели круглогодичную циркуляцию заболевания без отдельных пиков. Вирусные типы и подтипы менялись из года в год, но не во всех странах в отдельно взятом году. Совокупная доля положительных образцов с июня по ноябрь составила > 60% в Бангладеш, Камбодже, Индии, Лаосской Народно-Демократической Республики, Филиппинах, Таиланде и Вьетнаме. Таким образом, эти тропические и субтропические страны показали более ранние пики активности гриппа по сравнению со странами с умеренным климатом к северу от экватора.

Вывод

Большинству стран Южной и Юго-Восточной Азии, расположенных к северу от экватора, следует рассмотреть проведение вакцинации против гриппа в сроки с апреля по июнь; страны вблизи экватора без четко выраженного пика активности гриппа могут определять сроки вакцинации исходя из местных факторов.

Introduction

Influenza is a vaccine-preventable disease; safe and effective vaccines have been used for more than 60 years to mitigate the impact of seasonal epidemics.1 Annual human influenza epidemics occur during the respective winter seasons in the temperate zones of the northern and southern hemispheres – i.e. between November and March in the northern hemisphere and between April and September in the southern hemipshere.1–3 Data on influenza strains circulating globally are used to predict which strains have the highest probability of circulating in the subsequent season and this information is used to generate recommendations for seasonal influenza vaccine composition.4

The effectiveness of influenza vaccines depends not only on the right match between vaccine strains and circulating viral strains, but also on the vaccine-induced immune response in the target population.5,6 Several types of influenza vaccine are regularly available on the market. The most commonly used one – non-adjuvanted, influenza-virus-containing vaccine (the “inactivated influenza vaccine”) – induces neutralizing antibody responses that wane during the year.5 Therefore, appropriate timing of vaccination is a very important consideration in efforts to improve vaccine effectiveness. Better understanding of influenza seasonality and viral circulation is essential to selecting the best time for vaccination campaigns, which should precede the onset of the influenza season by several weeks.

Despite substantial influenza-associated morbidity and mortality and increasing local vaccine manufacturing capacity, many tropical Asian countries have yet to improve population-wide routine influenza vaccination.7–10 Although influenza surveillance data have been very useful in developing vaccination strategies in temperate regions, fewer data are available from countries in tropical and subtropical areas.4,11–13 Current progress in influenza surveillance and the widespread use of highly sensitive molecular assays for influenza diagnosis and viral typing have shown more complicated patterns of influenza activity in the tropics and subtropics than in other areas, with year-round circulation in some regions and bi-annual peaks of circulation in others.13,14 Such undefined patterns of influenza activity further complicate vaccination recommendations and, in particular, the selection of an appropriate time for vaccination.2,15 We undertook the analysis of influenza surveillance data from 10 countries in tropical and subtropical parts of southern and south-eastern Asia to characterize common trends in influenza circulation and therefore identify the most appropriate time for vaccination.

Methods

Data collection

Nasopharyngeal swabs from patients presenting with influenza-like-illness were collected at various clinics within each country as part of an influenza surveillance network across the Asian region. The number of specimens tested and the number of samples positive for influenza virus or viral nucleic acid were collected directly from weekly surveillance data or extracted from FluNet for 10 selected countries in Asia: Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Viet Nam.14 FluNet data are regularly collected by surveillance systems in geographically disparate sentinel sites that register cases of influenza-like illness or severe acute respiratory infection.13,16–27 Data on specimen positivity and on viral subtypes were based upon specimens from these surveillance systems; all samples were tested using reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction assays,28 with the exception of samples from India collected before 2009, which were tested with viral isolation methods.19

Since influenza surveillance in the different countries was started in different years, data for India, Malaysia, the Philippines and Viet Nam were available for 2006 to 2011; data for Cambodia, Indonesia, Singapore and Thailand, for 2007 to 2011; and data for Bangladesh and the Lao People's Democratic Republic, for 2008 to 2011.

Data analysis

Data on laboratory-confirmed influenza for each country were analysed individually in MS Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, United States of America) and PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA). Monthly influenza activity was calculated by adding the weekly number of specimens that tested positive during a given month. The monthly data were then plotted as the percentage of all positive specimens during the calendar year that corresponded to that month. Means and standard errors were calculated from the cumulative data for each country over the period evaluated. Data from 2009 were processed separately owing to the emergence of influenza virus A(H1N1)pdm09, which did not follow the usual seasonal pattern of influenza viruses.

Results

Circulating influenza viruses

Of a total of 253 611 specimens tested in the 10 participating countries, 45 282 (17.9%) were positive for viral nucleic acid (or for influenza viruses from specimens from India obtained before 2009) (Table 1).

Table 1. Rates of sample positivity to tests for the detection of influenza viruses or viral nucleic acid in 10 tropical and subtropical countries of southern and south-eastern Asia, by year, 2006–2011.

| Country/samples | Year |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | Total | |

| Bangladesh | |||||||

| Samples (n) | – | – | 2 654 | 3 263 | 3 471 | 3 195 | 12 583 |

| Positive, no. (%) | – | – | 270 (10.2) | 454 (13.9) | 558 (16.1) | 465 (14.6) | 1 747 (13.9) |

| Cambodia | |||||||

| Samples (n) | – | 1 247 | 1 347 | 2 345 | 2 583 | 2 583 | 10 105 |

| Positive, no. (%) | – | 95 (7.6) | 212 (15.7) | 405 (17.3) | 377 (14.6) | 485 (18.8) | 1 574 (15.6) |

| India | |||||||

| Samples (n) | 3 320a | 3 630a | 4 702a | 3 623 | 5 542 | 7 207 | 28 024 |

| Positive, no. (%) | 117 (3.5) | 166 (4.6) | 204 (4.3) | 564 (15.6) | 662 (11.9) | 1 090 (15.1) | 2 803 (10.0) |

| Indonesia | |||||||

| Samples (n) | – | 2 098 | 2 394 | 3 307 | 3 527 | 3 824 | 15 150 |

| Positive, no. (%) | – | 185 (8.8) | 580 (24.2) | 437 (13.2) | 716 (20.3) | 593 (15.5) | 2 511 (16.6) |

| Lao People's Democratic Republicb | |||||||

| Samples (n) | – | – | 483 | 2 094 | 1 519 | 1 853 | 5 949 |

| Positive, no. (%) | – | – | 85 (17.6) | 625 (29.8) | 355 (23.4) | 237 (12.8) | 1 302 (21.9) |

| Malaysia | |||||||

| Samples (n) | 1 657 | 1 841 | 2 196 | 1 682 | 862 | 2 085c | 10 323 |

| Positive, no. (%) | 130 (7.8) | 218 (11.8) | 209 (9.5) | 225 (13.4) | 48 (5.6) | 64 (3.1) | 894 (8.7) |

| Philippines | |||||||

| Samples (n) | 5 959 | 6 291 | 12 058 | 23 903 | 11 212 | 9 685c | 69 108 |

| Positive, no. (%) | 529 (8.9) | 536 (8.5) | 835 (6.9) | 7 914 (33.1) | 1899 (16.9) | 894 (9.2) | 12 607 (18.2) |

| Singapore | |||||||

| Samples (n) | – | 13 285 | 15 393 | 17 037 | 6 936 | 2 798c | 55 449 |

| Positive, no. (%) | – | 326 (2.5) | 1 525 (9.9) | 6 322 (37.1) | 3499 (50.4) | 1 129 (40.4) | 12 801 (23.1) |

| Thailand | |||||||

| Samples (n) | – | 4 315 | 3 736 | 3 067 | 3 171 | 3 132 | 17 421 |

| Positive, no. (%) | – | 794 (18.4) | 907 (24.3) | 645 (21.0) | 810 (25.5) | 646 (20.6) | 3 802 (21.8) |

| Viet Nam | |||||||

| Samples (n) | 4 146 | 6 215 | 6 904c | 4 372 | 1 886 | 5 976c | 29 499 |

| Positive, no. (%) | 812 (19.6) | 1 073 (17.3) | 1 477 (21.4) | 760 (17.4) | 193 (10.2) | 926 (15.5) | 5 241 (17.8) |

| Total samples | 15 082 | 38 922 | 51 867 | 64 693 | 40 709 | 42 338 | 253 611 |

| Total positive, no. (%) | 1 588 (10.5) | 3 393 (8.7) | 6 304 (12.2) | 18 351 (28.4) | 9 117 (22.4) | 6 529 (15.4) | 45 282 (17.9) |

a Testing by viral isolation.

b Surveillance included both outbreak sentinel surveillance.

c Data from FluNet.

Note: All tested samples (nasopharangeal swabs) came from people of all ages who presented to sentinel outpatient clinics with influenza-like illness: i.e. fever (reported or documented temperature > 38 °C) and cough or sore throat.

Bangladesh

Of the 12 583 specimens tested between 2008 and 2011, 1747 (13.9 %) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed that influenza activity was highest from June to September during most years (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), with peak activity in July and August (Fig. 2). Subtype A H1 and type B influenza viruses were the ones most frequently reported during 2008 (Fig. 3): they were found in 39.3% and 46.7%, respectively, of all specimens that tested positive. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 emerged in mid-2009 (42.7%) and its circulation persisted in 2010 (39.2%); it co-circulated mainly with subtype A H3 viruses (51.1%) in 2009 and with type B viruses (43.6%) in 2010 (Fig. 3). A H3 viruses were the ones most frequently reported in 2011 – 50.4% of all positive specimens – followed by type B viral strains (47.1%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 1.

Monthly distribution of samples testing positive for influenza virus or viral nucleic acid by year and country of southern or south-eastern Asia, 2006–2011

a This represents the samples testing positive on any given month, as a percentage of all the samples that tested positive during the year.

Note: Figures were obtained from weekly surveillance data.

Fig. 2.

Monthly patterns of influenza trends in samples testing positive to influenza virus or viral nucleic acid in 10 countries of southern and south-eastern Asia, 2006–2011

a This represents the mean value for the samples testing positive on any given month from 2006 to 2011 as a percentage of all the samples that tested positive during each year.

Note: Data from 2009 were excluded because of the presence of pandemic A(H1N1)pdm09, which did not follow the usual seasonality pattern. The latitude of each country’s capital city is shown at the top of each panel.

Fig. 3.

Influenza virus types and subtypes identified, by year and country of southern or south-eastern Asia, 2006–2011

a This represents the percentage of samples that tested positive for a specific viral type or subtype during a given year, as a total of all samples testing positive for influenza virus or viral nucleic acid the same year.

Note: Inconsistencies arise in some values due to rounding.

Cambodia

Of the 10 105 specimens tested from 2007 to 2011, 1574 (15.6%) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed influenza activity primarily from July to December for most years (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), with discrete peaks in September to October (Fig. 2). In 2007, influenza activity peaked in March and in August to September, while a peak of activity was identified between September and November for 2008 and between August and November for 2010 and 2011 (Fig. 1). Subtype A H3 (29.5% and 53.7%) and type B (56.8% and 34.1%) viral strains were the ones most frequently reported in 2007 and 2008. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus (22.9%) emerged in mid-2009 and its circulation persisted in 2010 (32.8%) and 2011 (25.2%), with co-circulation of subtype A H3 viruses (53.1%, 40.2%, and 9.2% in 2009, 2010 and 2011, respectively) and type B viral strains (22.9%, 27.0% and 65.6% in 2009, 2010 and 2011, respectively) (Fig. 3).

India

Of the 28 024 specimens tested from 2006 to 2011, 2803 (10.0%) were positive (Table 1). Between 2006 and 2008 all samples were studied by virus isolation methods. Analysis of monthly data showed increased influenza activity after June for most years (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), with discrete peaks between June and August (Fig. 1). In 2008, influenza activity remained above background activity throughout the year (Fig. 1). India had highly divergent monthly patterns between the northern and the southern states (data not shown). Subtype A H1 and type B viruses were the most frequently reported in 2006 and 2007 (35.0% and 38.0% for subtype A H1, and 38.5% and 47.0% for type B strains, respectively, Fig. 3). Subtype A H3 (39.7%) and type B (50.0%) viruses co-circulated in 2008. Subtype A H3 viruses circulated in the first half of 2009, followed by A(H1N1pdm09) virus (42.0%), which emerged mid-2009 and persisted in 2010 (40.2%) and 2011 (12.1%, Fig. 3). Type B (8.3%, 52.1%, 32.3%) and subtype A H3 influenza viruses (44.1%, 7.6%, 55.6%) co-circulated with A(H1N1pdm09) during all three years.

Indonesia

Of the 15 150 specimens tested from 2007 to 2011, 2511 (16.6%) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed year-round influenza activity for most years and different months of peak influenza activity in some years (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Circulating influenza types and subtypes were available only for 2010 and 2011. Influenza subtype A H3 and type B viruses were the most frequently reported (37.1% and 45.5%, for subtype A H3 virus and 49.9% and 24.8% for type B viruses, respectively). Identification of A(H1N1)pdm09 in the country varied from 11.8% of positive specimens in 2010 to 29.0% in 2011 (Fig. 3; no virus identification data were available for 2009).

Lao People's Democratic Republic

Of the 5949 specimens tested from 2008 to 2011, 1302 (21.9%) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed influenza circulation primarily from August to December for most years (Fig. 1), with discrete peaks in August, September and October (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). The Lao People's Democratic Republic reported circulation of subtype A H1 and type B viruses in 2008 (43.5% and 56.5%, respectively). Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus emerged in mid-2009 (47.5%) and persisted in 2010 (56.1%). Type B viruses were also identified in the country in 2010 (31.0%) and 2011 (31.3%). In 2011, A H3 was the most frequently reported viral subtype (63.5% of positive specimens) (Fig. 3).

Malaysia

Of the 10 323 specimens tested from 2006 to 2011, 894 (8.7 %) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed year-round influenza activity for most years and different months of peak influenza activity in different years (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Influenza A H1, A H3 and type B viruses circulated at varying levels in 2006 to 2008 (14.0–65.2%), while A(H1N1)pdm09 virus (24.5%) emerged in mid-2009 and persisted in 2010 (56.3%); it co-circulated with subtype A H3 (52.3%) and type B viruses (21.8%) in 2009 and mainly with type B viruses (39.6%) in 2010 (Fig. 3).

The Philippines

Of the 69 108 specimens tested from 2006 to 2011, 12 607 (18.2%) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed influenza activity primarily from June to October (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), with discrete peaks in July, August and September (Fig. 2). Subtype A H1 (46.1%) and type B strains (44.0%) were the predominant viruses in 2006; A H1 and A H3 viral subtypes were the ones most frequently reported in 2007 (34.1% and 59.7%, respectively), as were type B strains in 2008 (75.7%). Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus (92.8%) emerged in mid-2009 and persisted in 2010 (33.4%), when it co-circulated with type B (50.1%) and subtype A H3 viruses (16.4%). Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 was the virus most frequently (53.2%) reported in 2011, followed by type B influenza viruses (31.8%) (Fig. 3).

Singapore

Of the 55 449 specimens tested from 2007 to 2011, 12 801 (23.1%) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed year-round influenza activity and different months of peak influenza activity in different years (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2). Type B viruses were the most frequently reported influenza viruses in 2007 (79.1%) and 2008 (45.7%). Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 (79.2%) emerged in mid-2009 and persisted in 2010 (55.8%) and 2011 (44.2%); it co-circulated with subtype A H3 (22.5% and 33.8%, respectively) and type B viruses (21.7% and 22.0% respectively; Fig. 3).

Thailand

Of the 17 421 specimens tested from 2007 to 2011, 3802 (21.8%) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed that increased influenza activity occurred from January to March and from June to November or December on some years (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), with discrete peaks in August to September (Fig. 2). Subtype A H3 (43.3% and 27.2%) and type B viruses (40.1% and 42.9%) were the most frequently reported in 2007 and 2008, respectively. Pandemic A(H1N1)pdm09 emerged (60.6%) in mid-2009 and persisted in 2010 (53.3%); it co-circulated with type B (12.9%) viruses and with subtype A H1 virus (14.0%) and A H3 viruses (12.6%). A H3 (58.5%) was the viral subtype reported most frequently in 2011, followed by type B viral strains (33.7%, Fig. 3).

Viet Nam

Of the 29 499 specimens tested from 2006 to 2011, 5241 (17.8%) were positive (Table 1). Analysis of monthly data showed year-round circulation (Fig. 1 and Fig. 2), and some peak activity in July to August (Fig. 2). Subtype A H1 and type B viruses were the most frequently reported in 2006 and 2008, at 43.5 to 53.7% and 40.8 to 41.3%, respectively, whereas A H3 subtype (73.9%) and type B viruses (25.1%) were the ones most frequently reported in 2007. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 emerged (46.6%) in mid-2009 and persisted in 2010 (28.0%), when it co-circulated with subtype A H3 (71.5%) viruses. In 2011, A(H1N1)pdm09 was the influenza virus most frequently reported (74.1%), followed by type B viruses (22.1%, Fig. 3).

Circulating influenza types and subtypes

Different types and subtypes of influenza viruses circulated across southern and south-eastern Asia during the years studied: type A (subtypes H1 and H3) and type B strains (Fig. 3). Influenza A H1, A H3 and type B viruses were reported across the countries in 2006, 2007 and 2008. As in the rest of the world, pandemic A(H1N1pdm09) appeared in southern and south-eastern Asia in 2009; it was detected at different times in the various countries and it co-circulated with other influenza viruses (Fig. 1 and Fig. 3). In 2009, A(H1N1)pdm09 and subtype A H3 (plus some subtype A H1 and type B viruses) co-circulated in Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Thailand and Viet Nam, whereas A(H1N1)pdm09 was the predominant subtype reported from the Philippines and Singapore in 2009. In 2010, A(H1N1)pdm09 co-circulated mainly with type B viruses in some countries (Bangladesh, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand), and with subtype A H3 viruses in others (Cambodia and Viet Nam). In 2011, some countries (Bangladesh, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic and Thailand) showed almost no circulation of A(H1N1)pdm09 and varying degrees of co-circulation of subtype A H3 and type B viruses, while others (Cambodia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Singapore and Viet Nam) continued to have co-circulation of A(H1N1)pdm09 and influenza B (Fig. 3).

Influenza circulation and vaccination timing

Two major patterns of influenza circulation emerged from this study (Fig. 2). Some countries (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, the Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam) presented influenza peak activity between June and October, and three of them (India, Thailand and Viet Nam) showed additional minor peak activity during the northern hemisphere winter. Other countries (Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore) had year-round influenza activity and variable peak activity in some years (Fig. 4).

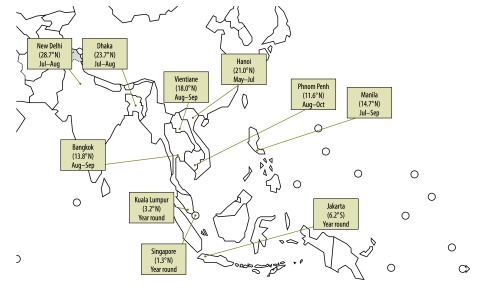

Fig. 4.

Months of peak influenza activity in 10 countries of southern and south-eastern Asia, 2006–2011

Note: The map illustrates the months in which influenza activity peaks in each country, as well as the latitudes for the capital cities.

Cumulative analysis of monthly influenza activity between 2006 and 2011 in the 10 countries revealed that > 60% of influenza cases were reported in June to November for Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, the Philippines, Thailand and Viet Nam (Table 2), whereas countries closer to the equator (Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore) had similar circulation of influenza viruses in both semesters (Table 2). The best vaccination times for each country, as proposed, are indicated by an arrow in Fig. 2.

Table 2. Existing and proposed schedules for influenza vaccination, by country, in accordance with influenza activity patterns .

| Countries | Positivity rate (%)a |

Vaccination scheduleb |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dec–May | Jun–Nov | Current | Proposed | ||

| With distinct influenza activity peaks | |||||

| Bangladesh | 14 | 86 | Before Hajjc | April–June and before Hajjc | |

| Cambodia | 14 | 86 | No policy | April–June | |

| India | 30 | 70 | October–November | April–Juned | |

| Lao People's Democratic Republic | 26 | 74 | April–Maye | April–June | |

| Philippines | 20 | 80 | May–December | April–June | |

| Thailand | 34 | 66 | June–August | April–June | |

| Viet Nam | 38 | 61 | No policy | April–June | |

| Without distinct influenza activity peaksf | |||||

| Indonesia | 57 | 43 | Before Hajjc | Based on national considerations, but before Hajjc | |

| Malaysia | 59 | 41 | Year round | Based on national considerations | |

| Singapore | 63f | 37 | Year round | Based on national considerations | |

Dec, December; Jun, June; Nov, November.

a Proportion of specimens that tested positive for influenza virus or viral nucleic acid. Data for 2009 are excluded.

b Data from local clinics, private or public, not necessarily adherent to the country’s Ministry of Health guidelines.29

c Hajj is the largest annual human gathering in the world and vaccination is important to protect from widespread influenza transmission. Hajj dates vary from year to year (July–December) since they depend on the moon.

d The northern most states of Jammu and Kashmir in India have peaks of influenza circulation in December to March and should consider vaccination in October to November (Mandeep Chadha, personal communication).

e In 2012, with donated northern hemisphere influenza vaccine formulation.

f Vaccine delivery may be dictated by opportunity, such as annual health screening events or health-care encounters.

g Singapore had a high positivity rate in January 2011. This skewed the proportions towards higher values in December to May.

Discussion

Weekly influenza surveillance data collected between 2006–2008 and 2011 were analysed for 10 countries in tropical and subtropical southern and south-eastern Asia. Despite differences in surveillance methods, demographic characteristics and environmental factors,2,3,12,30,31 it was possible to show peaks of influenza circulation in some countries, while in others influenza activity was detected throughout the year. These findings are consistent with the reports from the countries.13,16–27 Host-related and environmental factors (e.g. lower temperatures and decreased humidity) may influence both viral transmission and host susceptibility.3,32,33 Several countries, such as Bangladesh, Brazil, India and Viet Nam, have reported high influenza activity that coincides with rainy seasons,15,16,19,25 while other countries, such as the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand, have reported semi-annual peaks that are not necessarily associated with rainfall.13,24 Thus, the seasonality of influenza in the tropics and subtropics appears to be country-specific.

Throughout the surveillance period, influenza virus types A and B co-circulated across all countries included in this study.13 In 2009, influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus appeared in the area and persisted, with limited circulation, in 2010 and 2011. Some other countries also continued to report A(H1N1)pdm09 in 2011, and again during the winter of 2012.34,35 In 2011, A H3 virus was the subtype most frequently reported in several countries (Bangladesh, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic and Thailand). This resurgence of subtype A H3, explained as an antigenic drift of the virus,36–38 has led to the selection of A H3 Victoria for the vaccine formulation for the northern hemisphere in 2012–2013.35

During the study period, we observed that most countries in tropical and subtropical southern and south-eastern Asia (Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, the Philippines and Thailand) experienced peak influenza activity between June/July and October, ahead of most counties in the northern hemisphere, where influenza vaccine formulations are usually available around October (Fig. 4). Since country-specific data on influenza seasonality for most tropical and subtropical countries are sparse, vaccine licensing and use, and the timing of vaccination campaigns, have been historically regulated in accordance with their hemispheric location. Nevertheless, as influenza vaccination should precede peak activity periods in order to confer maximum protection, tropical and subtropical countries should consider starting vaccination campaigns earlier than other countries in the same hemisphere; i.e. during April to June each year for countries of southern and south-eastern Asia (Fig. 2).This is consistent with reports from Brazil stressing that the designation of influenza seasons by hemisphere may not apply to tropical and subtropical countries.15

There is no ideal vaccine timing for equatorial countries with year-round influenza activity and without defined peaks of disease activity, such as Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. For these countries, the best recommendation would be to use the most recent vaccine formulation recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) in that year. In Singapore, the Ministry of Health issues advisories once or twice a year when new vaccines with a change in formulation are released; since vaccines are purchased at an institutional level, residents usually receive the most recent influenza vaccine in their regular medical visits (Raymond Lin, personal communication). For countries that cover large areas with different average temperatures, an advisable option would be to use subnational data to guide sequential vaccine purchases and to select the time for vaccination campaigns. As an example, surveillance data in Indonesia show seasonal peaks of influenza in December and January for most of the islands, while other islands have peaks of infection from May to July.21 Similarly, countries with a large latitudinal span, like India, may also benefit from using subnational surveillance data to identify locally appropriate vaccination times. A summary of current and proposed influenza vaccination timing is shown in Table 2.

Although decades of public health research and global experience have shown that vaccination against influenza confers the best protection against influenza-associated deaths and complications,5 influenza vaccines are not available as part of routine public health programmes in most low- and middle-income countries in Asia.29,39 Nevertheless, the recent pandemic alarm in 2009, plus ongoing outbreaks of emerging influenza strains in other countries, such as A(H5N1) and, most recently, A(H7N9), as well as the number of deaths and complications in some regular influenza seasons, have increased the interest in influenza control in the area. To address the growing need for more affordable and accessible influenza vaccines during a pandemic, WHO has assisted countries in Asia (India, Indonesia, Thailand and Viet Nam) in developing their domestic vaccine production capacity.40 As a result, many countries have already established influenza vaccine manufacturing capabilities and some used locally produced vaccines during the 2009 pandemic.41,42 Furthermore, a recent pilot programme of influenza vaccination in the Lao People's Democratic Republic demonstrated that public–private partnerships can improve vaccination programmes in developing countries.43

The data reported here have limitations. The surveillance data collected in the countries during the six-year period only allow analyses of trends based on the percentages of nasopharyngeal specimens that tested positive, but not the calculation of incidence rates. In addition, comparison between the countries is difficult because of differences between countries in surveillance procedures and/or data collection methods (i.e. different sampling strategies, case definitions, age group selection, outpatient versus inpatient selection and biological tests), as well as in the criteria for submitting data to FluNet. Furthermore, the reporting systems might have changed over time, especially after 2009; different countries started surveillance at different times and some expanded or changed their surveillance sites over the study period. Nevertheless, these data provide a good overview of influenza seasonality and peaks of influenza circulation over the years; therefore, we were able to discern yearly trends for influenza circulation in each country, which revealed consistent patterns applicable to several tropical and subtropical countries in Asia.

In summary, we identified some patterns of circulation of influenza viruses in 10 tropical and subtropical Asian countries that are different from the patterns commonly seen in temperate countries. An early peak of influenza activity was detected between June and October, followed in some countries by a second, winter peak in December to February. Countries located close to the equator exhibited year-round circulation of the virus. Consequently, vaccination campaigns should adapt to the natural history of the virus in each country – i.e. vaccination campaigns should start before vaccination in countries of the temperate northern hemisphere showing early peaks of infection. On the other hand, for countries without epidemic peaks, year round vaccination with updated licensed vaccines might be required. These data can help decision-makers to better target vaccination programmes and inform regulatory authorities regarding the licensing of vaccines best timed to prevent seasonal epidemics in their country.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Eduardo Azziz-Baumgartner, Nancy Cox, Josh Mott and Tim Uyeki for their valuable comments.

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Hampson AW. Vaccines for pandemic influenza: the history of our current vaccines, their limitations and the requirements to deal with a pandemic threat. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2008;37:510–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tamerius J, Nelson MI, Zhou SZ, Viboud C, Miller MA, Alonso WJ. Global influenza seasonality: reconciling patterns across temperate and tropical regions. Environ Health Perspect. 2011;119:439–45. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Azziz Baumgartner E, Dao CN, Nasreen S, Bhuiyan MU, Mah-E-Muneer S, Al Mamun A, et al. Seasonality, timing, and climate drivers of influenza activity worldwide. J Infect Dis. 2012;206:838–46. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization Vaccines against influenza WHO position paper – November 2012. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:461–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathews JD, Chesson JM, McCaw JM, McVernon J. Understanding influenza transmission, immunity and pandemic threats. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2009;3:143–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00089.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simonsen L. The global impact of influenza on morbidity and mortality. Vaccine. 1999;17(Suppl 1):S3–10. doi: 10.1016/S0264-410X(99)00099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Estimates of deaths associated with seasonal influenza — United States, 1976–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59:1057–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang L, Ma S, Chen PY, He JF, Chan KP, Chow A, et al. Influenza associated mortality in the subtropics and tropics: results from three Asian cities. Vaccine. 2011;29:8909–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Viboud C, Alonso WJ, Simonsen L. Influenza in tropical regions. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e89. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park AW, Glass K. Dynamic patterns of avian and human influenza in east and southeast Asia. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:543–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70186-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moura FE. Influenza in the tropics. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:415–20. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e32833cc955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Western Pacific Region Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System Epidemiological and virological characteristics of influenza in the Western Pacific Region of the World Health Organization, 2006–2010. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization [Internet]. Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS). Geneva: WHO; 2013. Available from: http://www.who.int/influenza/gisrs_laboratory/en [accessed 20 February 2013].

- 15.de Mello WA, de Paiva TM, Ishida MA, Benega MA, Dos Santos MC, Viboud C, et al. The dilemma of influenza vaccine recommendations when applied to the tropics: the Brazilian case examined under alternative scenarios. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5095. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zaman RU, Alamgir AS, Rahman M, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Gurley ES, Sharker MA, et al. Influenza in outpatient ILI case-patients in national hospital-based surveillance, Bangladesh, 2007–2008. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blair PJ, Wierzba TF, Touch S, Vonthanak S, Xu X, Garten RJ, et al. Influenza epidemiology and characterization of influenza viruses in patients seeking treatment for acute fever in Cambodia. Epidemiol Infect. 2010;138:199–209. doi: 10.1017/S095026880999063X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mardy S, Ly S, Heng S, Vong S, Huch C, Nora C, et al. Influenza activity in Cambodia during 2006–2008. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:168. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chadha MS, Broor S, Gunasekaran P, Potdar VA, Krishnan A, Chawla-Sarkar M, et al. Multisite virological influenza surveillance in India: 2004–2008. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:196–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00293.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broor S, Krishnan A, Roy DS, Dhakad S, Kaushik S, Mir MA, et al. Dynamic patterns of circulating seasonal and pandemic A(H1N1)pdm09 influenza viruses from 2007–2010 in and around Delhi, India. PLoS One. 2012;7:e29129. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kosasih H, Roselinda, Nurhayati, Klimov A, Xiyan X, Lindstrom S, et al. Surveillance of influenza in Indonesia, 2003–2007. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:312-20.;7:312–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00403.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khamphaphongphane B, Ketmayoon P, Lewis HC, Phonekeo D, Sisouk T, Xayadeth S, et al. Epidemiological and virological characteristics of seasonal and pandemic influenza in Lao PDR, 2008–2010. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7:304-11.;7:304–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2012.00394.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simmerman JM, Chittaganpitch M, Levy J, Chantra S, Maloney S, Uyeki T, et al. Incidence, seasonality and mortality associated with influenza pneumonia in Thailand: 2005–2008. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chittaganpitch M, Supawat K, Olsen SJ, Waicharoen S, Patthamadilok S, Yingyong T, et al. Influenza viruses in Thailand: 7 years of sentinel surveillance data, 2004–2010. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2012;6:276–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2011.00302.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horby P, Mai Q, Fox A, Thai PQ, Thi Thu Yen N, Thanh T, et al. The epidemiology of interpandemic and pandemic influenza in Vietnam, 2007–2010: the Ha Nam household cohort study I. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:1062–74. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leo YS, Lye DC, Barkham T, Krishnan P, Seow E, Chow A. Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 surveillance and prevalence of seasonal influenza, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:103–5. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.091164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang JW, Lee CK, Lee HK, Loh TP, Chiu L, Tambyah PA, et al. Tracking the emergence of pandemic Influenza A/H1N1/2009 and its interaction with seasonal influenza viruses in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39:291–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC protocol of realtime RTPCR for swine influenza A(H1N1) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009. Available from: http://www.who.int/csr/resources/publications/swineflu/CDCrealtimeRTPCRprotocol_20090428.pdf [accessed 15 February 2013].

- 29.Gupta V, Dawood FS, Muangchana C, Lan PT, Xeuatvongsa A, Sovann L, et al. Influenza vaccination guidelines and vaccine sales in southeast Asia: 2008–2011. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52842. doi: 10.1126/science.1154137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shu YL, Fang LQ, de Vlas SJ, Gao Y, Richardus JH, Cao WC. Dual seasonal patterns for influenza, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:725–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1604.091578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moorthy M, Castronovo D, Abraham A, Bhattacharyya S, Gradus S, Gorski J, et al. Deviations in influenza seasonality: odd coincidence or obscure consequence? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:955–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03959.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaman J, Kohn M. Absolute humidity modulates influenza survival, transmission, and seasonality. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:3243–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806852106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tang JW, Lai FY, Nymadawa P, Deng YM, Ratnamohan M, Petric M, et al. Comparison of the incidence of influenza in relation to climate factors during 2000–2007 in five countries. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1958–65. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wagar LE, Rosella L, Crowcroft N, Lowcock B, Drohomyrecky PC, Foisy J, et al. Humoral and cell-mediated immunity to pandemic H1N1 influenza in a Canadian cohort one year post-pandemic: implications for vaccination. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization Recommended composition of influenza virus vaccines for use in the 2012–2013 northern hemisphere influenza season. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2012;87:83–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pariani E, Amendola A, Ebranati E, Ranghiero A, Lai A, Anselmi G, et al. Genetic drift influenza A(H3N2) virus hemagglutinin (HA) variants originated during the last pandemic turn out to be predominant in the 2011–2012 season in Northern Italy. Infect Genet Evol. 2013;13:252–60. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bedford T, Cobey S, Beerli P, Pascual M. Global migration dynamics underlie evolution and persistence of human influenza A (H3N2). PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000918. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell CA, Jones TC, Barr IG, Cox NJ, Garten RJ, Gregory V, et al. The global circulation of seasonal influenza A (H3N2) viruses. Science. 2008;320:340–6. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schlipköter U, Flahault A. Communicable diseases: achievements and challenges for public health. Public Health Rev. 2010;32:90–119. doi: 10.1007/BF03391594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friede M, Palkonyay L, Alfonso C, Pervikov Y, Torelli G, Wood D, et al. WHO initiative to increase global and equitable access to influenza vaccine in the event of a pandemic: supporting developing country production capacity through technology transfer. Vaccine. 2011;29(Suppl 1):A2–7. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dhere R, Yeolekar L, Kulkarni P, Menon R, Vaidya V, Ganguly M, et al. A pandemic influenza vaccine in India: from strain to sale within 12 months. Vaccine. 2011;29(Suppl 1):A16–21. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suhardono M, Ugiyadi D, Nurnaeni I, Emelia I. Establishment of pandemic influenza vaccine production capacity at Bio Farma, Indonesia. Vaccine. 2011;29(Suppl 1):A22–5. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.04.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Lao People’s Democratic Republic launches seasonal flu vaccination program. Atlanta; 2012. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/vaccination-program-launch-lao.htm [accessed 15 February 2013].