Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the effect of vouchers for maternity care in public health-care facilities on the utilization of maternal health-care services in Cambodia.

Methods

The study involved data from the 2010 Cambodian Demographic and Health Survey, which covered births between 2005 and 2010. The effect of voucher schemes, first implemented in 2007, on the utilization of maternal health-care services was quantified using a difference-in-differences method that compared changes in utilization in districts with voucher schemes with changes in districts without them.

Findings

Overall, voucher schemes were associated with an increase of 10.1 percentage points (pp) in the probability of delivery in a public health-care facility; among women from the poorest 40% of households, the increase was 15.6 pp. Vouchers were responsible for about one fifth of the increase observed in institutional deliveries in districts with schemes. Universal voucher schemes had a larger effect on the probability of delivery in a public facility than schemes targeting the poorest women. Both types of schemes increased the probability of receiving postnatal care, but the increase was significant only for non-poor women. Universal, but not targeted, voucher schemes significantly increased the probability of receiving antenatal care.

Conclusion

Voucher schemes increased deliveries in health centres and, to a lesser extent, improved antenatal and postnatal care. However, schemes that targeted poorer women did not appear to be efficient since these women were more likely than less poor women to be encouraged to give birth in a public health-care facility, even with universal voucher schemes.

Résumé

Objectif

Évaluer l'effet des bons pour les soins de maternité dans les établissements publics de santé sur l'utilisation des services de santé maternelle au Cambodge.

Méthodes

L'étude a utilisé des données tirées de l'Enquête démographique et sanitaire du Cambodge de 2010, qui couvre les naissances ayant eu lieu entre 2005 et 2010. L'effet des programmes de bons, mis en œuvre au départ en 2007, sur l'utilisation des services de santé maternelle a été quantifié en utilisant la méthode des doubles différences, qui a comparé les variations d'utilisation dans les districts bénéficiant de programmes de bons avec les variations d'utilisation dans les districts sans programme de bons.

Résultats

En général, les programmes de bons étaient associés à une augmentation de 10,1 points de pourcentage (pp) de la probabilité d'accouchement dans un établissement public de soins de santé. Chez les femmes issues des 40% des ménages les plus pauvres, l'augmentation était de 15,6 pp. Les bons étaient responsables d'environ un cinquième de l'augmentation observée pour les accouchements dans les établissements des districts bénéficiant de programmes de bons. Les programmes de bons universels ont eu un effet plus important sur la probabilité d'accouchement dans un établissement public que les programmes ciblant les femmes les plus pauvres. Les deux types de programmes ont augmenté la probabilité de bénéficier de soins postnatals, mais cette augmentation était uniquement significative chez les femmes non pauvres. Le programme de bons universels et non ciblés a considérablement augmenté la probabilité de bénéficier de soins anténatals.

Conclusion

Les programmes de bons ont augmenté le nombre d'accouchements dans les centres de santé et, dans une moindre mesure, amélioré les soins anténatals et postnatals. Cependant, les programmes ciblant les femmes les plus pauvres n'ont pas paru efficaces, car ces femmes étaient plus susceptibles que les femmes moins pauvres d'être incitées à accoucher dans un établissement public de soins de santé, même avec des programmes de bons universels.

Resumen

Objetivo

Evaluar el efecto de los bonos para atención sanitaria materna en centros de salud públicos sobre la utilización de los servicios de atención sanitaria materna en Camboya.

Métodos

El estudio incluyó datos de la Encuesta demográfica y sanitaria de Camboya del año 2010, que recolecta los nacimientos que tuvieron lugar entre 2005 y 2010. Se cuantificó el efecto de los sistemas de bonos, puestos en práctica por primera vez en el año 2007, sobre la utilización de los servicios de atención sanitaria materna por medio de un método de diferencia de diferencias que comparó los cambios en la utilización de dichos servicios en los distritos con sistemas de bonos respecto a los de los distritos sin sistemas de bonos.

Resultados

En general, los sistemas de bonos están asociados con a un aumento de 10,1 puntos porcentuales (pp) en la probabilidad de parto en un centro público de atención sanitaria; entre las mujeres del 40% de los hogares más pobres, el aumento fue de 15,6 pp. Los bonos fueron responsables de alrededor de una quinta parte del incremento observado en los partos institucionales en los distritos con programas. Los sistemas de bonos universales tuvieron un efecto mayor sobre la probabilidad de dar a luz en un centro público que los sistemas destinados a las mujeres más pobres. Ambos tipos de sistemas aumentaron la posibilidad de recibir atención postnatal, pero dicho incremento fue significativo solo para las mujeres que no eran pobres. Los sistemas de bonos universales no dirigidos a un grupo en concreto aumentaron notablemente la probabilidad de recibir atención prenatal.

Conclusión

Los sistemas de bonos aumentaron el número de partos en los centros de salud y, en menor medida, mejoraron la atención prenatal y postnatal. Sin embargo, los sistemas dirigidos a las mujeres más pobres no parecen ser eficientes, ya que estas mujeres ya tenían más probabilidades que las mujeres menos pobres de que se les animara a dar a luz en un centro público de atención sanitaria , incluso con los sistemas de bonos universales.

ملخص

الغرض

تقييم تأثير قسائم رعاية الأمومة في مرافق الرعاية الصحية العمومية على الانتفاع بخدمات الرعاية الصحية للأمهات في كمبوديا.

الطريقة

تضمنت الدراسة بيانات من المسح الديمغرافي والصحي في كمبوديا لعام 2010، والذي شمل المواليد في الفترة من 2005 إلى 2010. وتم تحديد مقدار تأثير مخططات القسائم، التي تم تنفيذها لأول مرة في عام 2007، على الانتفاع بخدمات الرعاية الصحية للأمهات باستخدام طريقة الفرق في الاختلافات التي قارنت التغييرات في الانتفاع في المناطق التي توجد بها مخططات القسائم مع التغييرات في المناطق التي لا توجد بها هذه المخططات.

النتائج

بشكل عام، ارتبطت مخططات القسائم بزيادة قدرها 10.1 نقطة مئوية (pp) في احتمالية الولادة في مرفق الرعاية الصحية العمومية؛ وكانت الزيادة بين النساء اللواتي ينتمين إلى 40 % من الأسر المعيشية الأفقر 15.6 نقطة مئوية. وكانت القسائم مسؤولة عن حوالي خمس الزيادة التي لوحظت في الولادات المؤسسية في المناطق التي يوجد بها قسائم. وكان لمخططات القسائم الشاملة تأثير أكبر على احتمالية الولادة في مرفق عمومي من المخططات التي تستهدف أفقر النساء. وزاد كلا نوعا المخططات من احتمالية تلقي رعاية ما بعد الولادة، غير أن الزيادة كانت كبيرة بالنسبة للنساء غير الفقيرات فقط. وأدت مخططات القسائم الشاملة، ولكن غير المستهدفة، على نحو كبير من إلى زيادة احتمالية تلقي رعاية ما قبل الولادة.

الاستنتاج

أدت مخططات القسائم إلى زيادة الولادات في المراكز الصحية وتحسين رعاية ما قبل الولادة وما بعد الولادة إلى حد أقل. ومع ذلك، لم تكن المخططات التي استهدفت النساء الأفقر فعالة على ما يبدو نظراً لأرجحية تشجيع هؤلاء النساء على الولادة في مرفق الرعاية الصحية العمومية عن النساء الأقل فقراً، حتى مع مخططات القسائم الشاملة.

摘要

目的

评价柬埔寨公共医疗设施孕产妇保健凭单对孕产妇保健服务利用的影响。

方法

研究涉及来自2010年柬埔寨人口和卫生调查的数据,该调查涵括2005和2010年之间的生育情况。使用双重差分方法对最先在2007年实施的凭单制对孕产妇保健服务利用的影响进行量化,该方法将使用凭单制区域的服务利用变化和未使用凭单制地区的变化进行比较。

结果

整体而言,凭单制与公共医疗设施中分娩可能性10.1个百分点(pp)的提高相关;在来自最贫穷的40%家庭的女性中,这种可能性的提高是15.6百分点。在实施计划的区域中,因为凭单而产生的设施内分娩增加量是观察到增加量的五分之一左右。较之针对最贫穷妇女的计划,普及性的凭单制对公共设施分娩可能性有更大的影响。两种凭单制都提高了接受产后护理的可能性,但是仅非贫穷妇女的提高比较显著。普及性而非针对性的凭单制显著提高接受产后护理的可能性。

结论

凭单制增加了在健康中心的分娩,并在更小的程度上改善了产前和产后的护理。然而,针对较为贫穷女性的凭单制似乎没有效果,因为这些妇女即使有普及性凭单制也不会像不那么贫穷的妇女那样更可能被促使在公共卫生设施中分娩。

Резюме

Цель

Оценить влияние ваучеров, предоставляемых в учреждениях государственного здравоохранения Камбоджи, на использование медицинских услуг в области охраны материнства.

Методы

Исследование было основано на данных Обзора демографии и здравоохранения в Камбодже (2010 г.), который охватывал роды в 2005-2010 гг. Влияние ваучерных программ, впервые реализованных в 2007 году, на использование медицинских услуг матерями определялось на основе метода «разности разностей», в котором сравнивались изменения в использовании медицинских услуг в районах, использующих ваучеры, с изменениями в районах, где подобные программы не реализовывались.

Результаты

В целом, использование ваучеров было связано с увеличением на 10,1 процентных пункта (п.п.) вероятности принятия родов в учреждении общественного здравоохранения; среди женщин из беднейших 40% домохозяйств рост составил 15,6 п.п. На ваучеры приходилось около 20% от общего увеличения числа родов в медицинских учреждениях в районах, реализовывавших данные программы. По сравнению с программами, ориентированными на женщин из беднейших слоев населения, универсальные ваучерные программы имели больший эффект на вероятность принятия родов в учреждении общественного здравоохранения. Оба типа программ увеличили вероятность получения послеродового ухода, но увеличение было значительным только для женщин, не принадлежавших к бедным слоям населения. Универсальные, а не ориентированные на определенные слои населения, ваучерные программы значительно увеличили вероятность получения дородовой помощи.

Вывод

Ваучерные программы привели к увеличению числа родов в медицинских центрах и, в меньшей степени, к улучшению дородовой и послеродовой помощи. Однако, программы, ориентированные на менее обеспеченных женщин, по-видимому оказались неэффективными, поскольку эти женщины вероятно нуждались в большем поощрении к родам в государственных медицинских учреждениях, даже при реализации универсальных ваучерных программ, чем женщины из менее бедных слоев населения.

Introduction

Vouchers are increasingly being used to encourage the utilization of maternity services with the objective of bringing neonatal and maternal mortality rates closer to the targets set by Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5. Vouchers have been introduced in Bangladesh,1–3 China, India,4 Indonesia, Kenya,5,6 Pakistan7 and Uganda and have been associated with increased utilization of maternal health care.8,9 However, since other interventions have been implemented at the same time, one cannot be sure that the increase is attributable to vouchers alone. Given the presence of alternative interventions that can influence the demand for, and supply of, maternal health care,10 it is important to have evidence that voucher schemes of varying designs can be effective in different geographical and cultural contexts. The aim of this study was to examine the influence of vouchers on the utilization of maternal health care in Cambodia.

During the last decade, there has been a remarkable increase in the utilization of maternal health services in Cambodia. Coverage by skilled birth attendants has increased from 32% in 2000 to 71% in 2010, while the proportion of deliveries taking place in health-care facilities rose from 10% to 54%.11 Maternal health-care vouchers, which were introduced in 2007 and are now available in about one third of the country, may have contributed to these improvements. These vouchers can be used to pay for antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care at public health-care facilities whose costs are reimbursed by donor-financed agencies.

Unlike the voucher schemes operating in most other countries,9,12 those in Cambodia do not cover a range of providers but are, instead, restricted to subsidizing maternity care at public facilities, mainly health centres. As such, the vouchers function as fee waivers. In addition, the schemes have two other important features: health-care facilities are reimbursed for the care provided and women are given information encouraging them to use maternal health care in these facilities.

Between 2007 and 2010, voucher schemes were implemented in 22 of 77 operational health districts in Cambodia. In 14 districts, the voucher scheme was universal, whereas in 8 it targeted the poorest women (detailed information on the roll out of the voucher schemes is available from the authors on request). In both types of scheme, pregnant women were identified mainly by local health volunteers, who distributed the vouchers and provided advice on safe motherhood at village meetings with the aim of making women aware of the benefits of using maternal health care at public facilities.

At the end of each month, health centres were paid for each voucher coupon collected in accordance with the posted user fees. In principle, the universal voucher scheme provided reimbursement only when all components of a package of antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care had been completed. But, in practice, a health centre may have been paid for a delivery even though it did not provide proof that the woman had completed all the required antenatal and postnatal care visits and women may not have been reimbursed for fees they paid for antenatal care after completion of the care package. Table 1 provides details of the two types of voucher schemes.13

Table 1. Characteristics of voucher schemes for maternal health-care services, Cambodia, 2007–2013.

| Characteristic | Targeted scheme | Universal scheme |

|---|---|---|

| Population eligible for vouchers | The poorest women during pregnancy and after delivery | All women during pregnancy and after delivery |

| Implementation period | 2007–2010 | 2008 to present |

| Number of operational districts | 8 (including 4 that changed to a universal scheme) | 18 (including 4 that changed from a targeted scheme) |

| Benefit package | i) Three antenatal care visits, delivery and one postnatal care visit at a contracted health-care facility; ii) reimbursement of transportation costs for up to five trips between home and the nearest health-care facility, or arranged transportation; iii) fees for hospital referral covered by a health equity fund. |

i) Four antenatal care visits, delivery and one postnatal care visit within 24 hours at a contracted health-care facility; ii) transportation costs covered in three operational districts; iii) fees for hospital referral covered only if a health equity fund was operating. |

| Health-care facility compensation | i) The facility was paid according to posted user fees (i.e. US$ 7.50 for each delivery and US$ 0.25 for each antenatal or postnatal care visit); ii) in a few operational districts only, the facility was paid even if a referral was made to a hospital for delivery. |

i) The facility was paid US$ 10 per package of four antenatal care visits, delivery and one postnatal care visit; ii) the facility was paid even if a referral was made to a hospital for delivery. |

US$, United States dollar.

To isolate the effect of vouchers on the utilization of maternal health care, it is important to control for other interventions that could have an influence. Since 1999, various forms of performance-based financing have linked the funding of public health-care facilities in some operational districts to predefined targets, most of which involved the provision of maternal and child health services.14 Health equity funds and a government fee waiver scheme compensate facilities, mostly hospitals, for exempting poor patients from the need to pay fees.15,16 In addition, at the end of 2007, the government introduced the nationwide Midwife Incentive Scheme, which pays midwives 10 United States dollars (US$) for each live birth they attended in a referral hospital and US$ 15 for each delivery they attended in a health centre, on top of the fee charged to the patient.13,17

Methods

We used data from the 2010 Cambodian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), a nationally representative sample of 18 754 women of reproductive age. The women were asked about their use of maternal health care for pregnancies in the previous 5 years. We concentrated on services covered by the voucher schemes: antenatal care, birth (i.e. delivery) in a public health-care facility and postnatal care from a skilled provider. Table 2 describes how, and for which births, outcome variables were assessed and reports the mean value of each outcome variable observed in the 2010 Cambodian DHS sample.

Table 2. Maternal health care outcomes and observations from the 2010 Cambodian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) .

| Outcome variable | Definition of outcome variable | 2010 Cambodian DHS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description of sample | No. of observations in sample | Mean value of outcome variable for sample | |||

| Antenatal care | The variable was set to 1 if the child’s mother had at least three antenatal care visits at a public health-care facility, 0 otherwise | Most recent births | 4916 | 0.79 | |

| Delivery | The variable was set to 1 if the child was born in a public health-care facility, 0 otherwise | Births in the 5 years preceding the survey | 7270 | 0.42 | |

| Place of delivery | |||||

| Home | The variable was set to 1 if the child was born at home, 0 otherwise | Births in the 5 years preceding the survey | 3485 | 0.48 | |

| Public hospital | The variable was set to 1 if the child was born in a public hospital, 0 otherwise | Births in the 5 years preceding the survey | 1289 | 0.18 | |

| Health centre | The variable was set to 1 if the child was born in a health centre, a health post or another public facility,a 0 otherwise | Births in the 5 years preceding the survey | 1776 | 0.25 | |

| Private facility | The variable was set to 1 if the child was born in a private facility, 0 otherwise | Births in the 5 years preceding the survey | 664 | 0.09 | |

| Postnatal careb | The variable was set to 1 if the child’s mother had at least one postnatal care visit with a skilled provider, 0 otherwise | Most recent births | 5685 | 0.59 | |

NA, not applicable.

a Fewer than 3% of deliveries took place in a health post or another public facility.

b The Cambodian DHS did not include information on the place where the postnatal care visit took place.

In estimating the effect of vouchers on the utilization of maternity services, we controlled for characteristics of the child, mother, household and operational district (Table 3). Covariates for the child included the child’s sex, the mother’s age at childbirth and indicators of a short birth interval and of birth order. Maternal characteristics were the mother’s age at first marriage, experience with modern contraception and educational level. Household socioeconomic status was estimated using quintiles of a wealth index that was devised by principal component analysis of a set of household assets and dwelling characteristics.18 Other household covariates included the age and sex of the head of the household. Time-invariant differences across districts were taken into account by including an indicator for each operational district. In addition, we included indicators of whether or not a health equity fund, a government fee-waiver scheme or performance-based financing was in place in the operational district at the time of each child’s birth and an indicator of whether the village location was urban or rural. We confirmed that the results of the study were not substantially affected by using a single indicator for any type of performance-based financing instead of separate indicators for the different types of performance-based financing that may have been in place during the study period. Data from the Cambodia Health Coverage Plan indicated that there were no systematic or substantial differences in the supply of health care at baseline between operational districts that implemented a voucher scheme and those that did not (details are available from the authors on request).

Table 3. Baseline covariate values and the difference between intervention and control districts in the trend between 2001 and 2009, Cambodia.

| Covariate | Mean valuea of covariate in 2005 |

Pc (for association between change in covariate over time and introduction of voucher scheme) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention districtsb (n = 22) | Control districts (n = 55) | ||

| Child | |||

| Child is male | 0.482 | 0.503 | 0.728 |

| Mother's age at childbirth ≤ 20 years | 0.092 | 0.101 | 0.646 |

| Mother's age at childbirth 21–34 years | 0.730 | 0.731 | 0.889 |

| Short interval from previous childbirth | 0.134 | 0.120 | 0.177 |

| First born | 0.300 | 0.282 | 0.389 |

| Birth order > 4 | 0.214 | 0.211 | 0.302 |

| Mother | |||

| Mother's age at first marriage, years | 19 | 19 | 0.665 |

| Mother has used modern contraception | 0.244 | 0.279 | 0.253 |

| Mother completed primary education | 0.599 | 0.529 | 0.909 |

| Mother completed secondary education | 0.164 | 0.165 | 0.722 |

| Household | |||

| In poorest quintile by wealth indexd | 0.294 | 0.340 | 0.645 |

| In second poorest quintile by wealth indexd | 0.229 | 0.224 | 0.326 |

| In third poorest quintile by wealth indexd | 0.184 | 0.148 | 0.842 |

| In second richest quintile by wealth indexd | 0.156 | 0.144 | 0.398 |

| Age of household head, years | 39 | 40 | 0.708 |

| Male household head | 0.837 | 0.853 | 0.766 |

| District | |||

| Urban | 0.189 | 0.189 | 0.776 |

| Has health equity fund | 0.091 | 0.517 | 0.260 |

| Has government fee waiver scheme | 0 | 0 | 0.197 |

| Has any performance-based financing | 0.108 | 0.406 | 0.556 |

| No. of observations | 651 | 1950 | NA |

NA, not applicable.

a All covariates were dummy variables set to 1 if the respective description was satisfied and 0 otherwise, except for the mother's age at first marriage and the age of the household head.

b Intervention districts were those that had implemented a voucher scheme by 2010. No district had a voucher scheme in place in 2005.

c P-value for the null hypothesis that the change in the mean of each covariate between 2001 and 2009 was not associated with the introduction of a voucher scheme were derived using t tests. This involved regressing each covariate on a set of birth period and district fixed effects, as well as on an indicator for the operation of a voucher scheme within the period and district, and testing whether the coefficient for the voucher scheme indicator was zero.

d The wealth index was devised by principal component analysis of a set of household assets and dwelling characteristics.

Note: Data were obtained from the 2005 and 2010 Cambodian Demographic and Health Surveys.

The Global Positioning System codes of the sample clusters in the 2010 Cambodian DHS were used to identify the operational district within which each commune was located. However, for reasons of confidentiality, the Global Positioning System codes were made slightly inaccurate and we were unable to identify the operational districts of 82 communes out of a total of 611. Since 27 of these 82 unmatched communes were located close to Phnom Penh, the mothers resident in them (i.e. 13% of the total) were somewhat better-off than average and more likely to live in an urban area. No other important difference in covariates was found between the matched and unmatched communes.

Statistical analysis

We assessed the effect of a voucher scheme by comparing changes in the utilization of maternal health care in operational districts in which the scheme was introduced in the period from 2005 to 2010 (i.e. intervention districts) with changes in districts that did not introduce vouchers during the same period (i.e. control districts). We assumed that, after taking covariates into account, the use of maternal health care in intervention districts would have evolved in the same way in the absence of vouchers as it did in the control districts – the common trends assumption. Under this assumption, the plausibility of which is assessed in the results section, the difference-in-differences strategy isolates the part of the before-and-after change that is attributable to the effect of vouchers.19 We implemented this strategy by estimating a logit model for each maternal health care utilization measure (i.e. antenatal care, delivery and postnatal care). The model included: an indicator of whether a voucher scheme was operating in the district at the time of pregnancy or delivery; indicators of the month and year of each child’s birth, which captured any time variation in utilization that was assumed to be common to intervention and control districts; a full set of district (fixed) effects that captured time-invariant differences between districts; and time-varying child, mother and district covariates that allowed for any differences in trends in these observable determinants between intervention and control districts and also increased precision. In examining the choice of place of delivery, we estimated a multinomial logit model with a birth year indicator instead of birth month and year indicators, as this model had difficulty converging with the larger number of time variables.

For each maternal health-care utilization measure, we present the estimated effect of the voucher scheme as the resulting change in the predicted probability of utilization averaged over all births taking place in intervention districts when the voucher scheme was operational. This corresponds to the estimated average effect of the voucher scheme among pregnant women and women giving birth in the intervention districts.20

We evaluated whether the effect of the voucher scheme on the behaviour of poor and non-poor women differed using, for each maternal health-care measure, an extended logit model that included the interaction between the voucher scheme indicator and an indicator of whether or not the household was in the bottom two wealth quintiles. Although the second indicator was intended to identify the poorest women, it did not use the same definition of poverty as targeted voucher schemes, which would probably, in any case, have made inclusion and exclusion errors in identifying the poor. The effect of the voucher scheme indicator was calculated for the poorest 40% of women and for the remaining 60%, to whom we refer as the “poor” and “non-poor”, respectively.

We assessed the differential effect of the two types of voucher scheme by replacing the single indicator for any voucher scheme by two indicators for the universal and targeted voucher schemes, respectively. In addition, we examined whether the effects of the two voucher schemes differed by poverty status. In four operational districts, there was a transition from a targeted scheme to a universal scheme during the study period. We decided which of the two voucher scheme indicators to use by comparing the child’s date of birth with the date on which the transition occurred.

Standard errors were adjusted for clustering at the operational district level to allow for any shocks to the outcome at that level which may be correlated over time, such as the outbreak of an infectious disease or fluctuations in the local economy. Such shocks could have resulted in an overstatement of the precision of the estimates.21,22 The significance of the effects was evaluated using Z-tests. All statistical calculations were performed using Stata version 12 (StataCorp. LP, College Station, United States of America).

Results

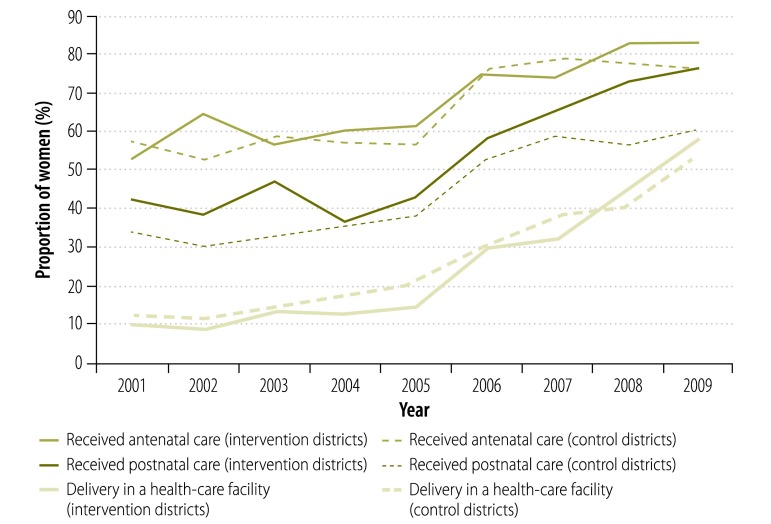

Overall, the use of maternal health care increased substantially between 2001 and 2009. Fig. 1 shows the trends in the use of antenatal care, delivery in a public health-care facility and postnatal care in both intervention and control districts.

Fig. 1.

Trends in maternal health-care service utilization, by voucher scheme,a Cambodia, 2001–2009

a Voucher schemes were implemented gradually in intervention districts from 2007 onwards.

To examine the plausibility of our assumption that there was a common trend in the way the use of maternal health care would have changed in intervention and control districts in the absence of vouchers, we used data from both 2005 and 2010 Cambodian DHSs, which enabled us to examine data on births from as early as 2000. Fig. 1 shows that the trends in each outcome were reasonably parallel before the start of the voucher schemes in 2007. Thereafter, they began to diverge, especially the trend for postnatal care. In addition, the data presented in Table 3 also give credibility to the common trend assumption: the means of the household and mother covariates at baseline in 2005 were similar in the future intervention and control districts and the null hypothesis that there was no association between the introduction of a voucher scheme and the change in the mean of each covariate was never rejected (i.e. the P-values from t tests all exceeded 0.1).

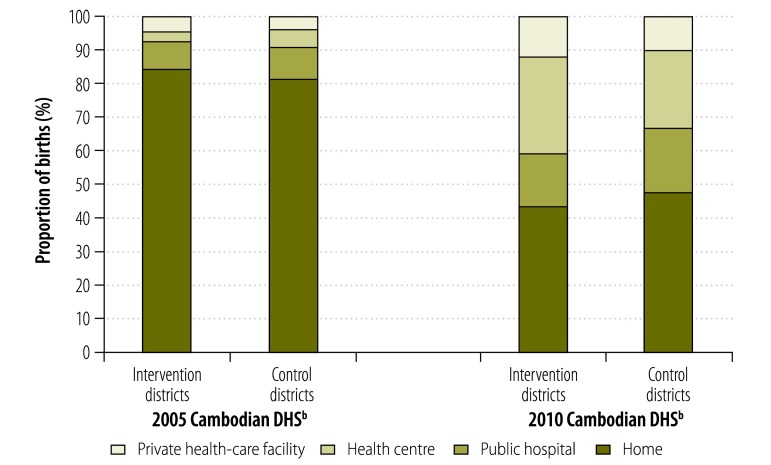

Fig. 2 shows the sharp decrease in home births and the increase in births in public health-care facilities that occurred in both intervention and control districts between the 2005 and 2010 Cambodian DHSs. The proportion of home births fell more in districts in which a voucher scheme had been implemented by 2010 than in those with no voucher scheme.

Fig. 2.

Place of delivery, by voucher scheme,a Cambodia, 2000–2010

DHS, Demographic and Health Survey.

a.Voucher schemes were implemented gradually in intervention districts from 2007 onwards.

b Percentages are based on births in the 5 years preceding each survey.

Table 4 shows the estimated average effect of voucher schemes on the utilization of antenatal care, delivery at a public health-care facility and postnatal care. The probability that delivery would take place in a public health-care facility was significantly and substantially increased, by 10.1 percentage points (pp), following the implementation of a voucher scheme. In addition, the probability of receiving postnatal care was increased by 5.3 pp. Voucher schemes had no significant effect on the probability that a woman would receive at least three antenatal care visits, although the estimate is positive. Voucher schemes increased the probability of delivery at a public health-care facility more for women in the poorest 40% of households than for non-poor women: the probability increase in the two groups was 15.6 pp and 5.3 pp, respectively. In addition, Table 4 also shows the specific effects of the universal and targeted voucher schemes. The universal scheme increased the probability that a woman would receive antenatal care by 5.4 pp; among the poor, the increase was 10.1 pp. The effect on the probability of delivery at a public health-care facility was also positive for both types of scheme, although it was larger and more significant for the universal scheme. For both types of scheme, the effect was larger among the poor: the probability of delivery at a public health-care facility for poor women was increased by 11.3 pp and 17.8 pp with the targeted and universal schemes, respectively. Moreover, the effect on the probability of receiving postnatal care was significant for both types of scheme only among the non-poor: the probability increase was 5.6 pp and 6.0 pp with the targeted and universal schemes, respectively.

Table 4. Maternal health-care voucher schemes and the use of maternity care, Cambodia, 2005–2010.

| Women offered vouchers | Estimated percentage point change in probabilitya of outcome attributable to the voucher scheme |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three or more antenatal care visits |

Delivery in a public health-care facility |

Postnatal care |

||||||

| Mean | SEb | Mean | SEb | Mean | SEb | |||

| All voucher schemes | ||||||||

| All | 3.2 | 2.3 | 10.1** | 4.4 | 5.3** | 2.4 | ||

| Poorc | 4.8 | 3.6 | 15.6** | 4.6 | 4.6 | 4.5 | ||

| Non-poor | 2.1 | 2.7 | 5.3 | 4.7 | 6.8** | 1.8 | ||

| Targeted voucher schemesd | ||||||||

| All | −1.6 | 2.8 | 7.5 | 5.2 | 6.4* | 3.9 | ||

| Poorc | −3.4 | 4.0 | 11.3** | 5.4 | 7.4 | 6.2 | ||

| Non-poor | 1.6 | 5.2 | 2.3 | 5.8 | 5.6*** | 2.1 | ||

| Universal voucher schemes | ||||||||

| All | 5.4** | 2.4 | 11.8** | 5.8 | 4.7 | 2.9 | ||

| Poorc | 10.1** | 3.9 | 17.8*** | 5.0 | 2.4 | 5.5 | ||

| Non-poor | 2.9 | 2.5 | 7.0 | 5.6 | 6.0*** | 1.8 | ||

| No. of observations | 4869 | NA | 7221 | NA | 5656 | NA | ||

NA, not applicable; SE, standard error; *, P < 0.10; **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.01 (Z test of no effect).

a The table shows the partial effect of the voucher schemes on the probability of each outcome, in percentage points, estimated using logit models that included the covariates listed in Table 3 plus the birth period (i.e. month and year) and district fixed effects. The effect of a voucher scheme was averaged over all births in intervention districts when the voucher scheme was in operation.

b SEs were adjusted for clustering at the operational district level.

c Women in the poorest 40% of households, as determined using a wealth index, were regarded as poor. Non-poor women were from the other 60% of households.

d Schemes targeted poor women.

Note: Data were obtained from the 2010 Cambodian Demographic and Health Survey.

Table 5 shows the estimated effect of voucher schemes on the probability of giving birth at one of three types of health-care facilities – public hospitals, public health centres and private facilities – as derived using the multinomial model. Voucher schemes increased the probability of delivery at a health centre by 7.4 pp; among the poor, the increase was 10.5 pp. In contrast, there was no significant effect on delivery at a public hospital or private facility. The main shift was, therefore, from delivery at home to delivery at a health centre. The estimated effect of vouchers on the location of delivery was similar for universal and targeted schemes.

Table 5. Maternal health-care voucher schemes and delivery at health-care facilities, Cambodia, 2005–2010.

| Women offered vouchers | Estimated percentage point change in probabilitya of delivery at facility attributable to the voucher scheme |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Public hospital |

Public health centre |

Private facility |

||||||

| Mean | SE | Mean | SE | Mean | SE | |||

| All voucher schemes | ||||||||

| All | 2.2 | 2.0 | 7.4* | 3.8 | −1.8 | 2.1 | ||

| Poorb | 0.9 | 2.0 | 10.5** | 4.5 | −1.4 | 0.9 | ||

| Non-poor | 3.4 | 2.3 | 4.8 | 3.2 | −1.6 | 3.5 | ||

| Targeted voucher schemesc | ||||||||

| All | −0.3 | 2.0 | 3.7 | 4.5 | 2.7 | 4.0 | ||

| Poorb | −0.9 | 2.1 | 9.6* | 5.5 | −0.7 | 1.0 | ||

| Non-poor | −0.1 | 3.3 | −3.2 | 3.8 | 8.1 | 7.1 | ||

| Universal voucher schemes | ||||||||

| All | 3.0 | 2.8 | 9.5** | 4.7 | −2.9 | 2.1 | ||

| Poorb | 2.0 | 3.0 | 11.3** | 5.4 | −1.6* | 0.9 | ||

| Non-poor | 3.7 | 3.0 | 7.3* | 3.8 | −3.5 | 3.4 | ||

SE, standard error; *, P < 0.10; **, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.01 (Z test of no effect).

a The table shows the average partial effect of the voucher schemes on the probability of delivery at each facility, in percentage points, derived from multinomial logit models (using 7180 observations) with the covariates listed in Table 3 plus district fixed effects and birth year effects.

b Women in the poorest 40% of households, as determined using a wealth index, were regarded as poor. Non-poor women were from the other 60% of households.

c Schemes targeted poor women.

Note: Data were obtained from the 2010 Cambodian Demographic and Health Survey.

Discussion

Vouchers for maternal health care at public facilities contributed to the substantial increase in the number of deliveries taking place in these facilities in Cambodia. The operation of voucher schemes raised the probability that a woman would give birth in a public facility by around 10 pp. This corresponds to about one fifth of the average increase during the study period in the proportion of births taking place in these facilities in districts with voucher schemes; the proportion increased from 17% in 2005 to 68% in 2010. Other interventions, such as incentive payments to midwives, were relatively more important at the national level.

Our study, like most similar studies, was not able to detect meaningful changes in maternal or neonatal mortality associated with the introduction of vouchers. The size of the sample would have enabled us to detect a minimum change in neonatal mortality of about 2 pp, which is two thirds of the average mortality rate in the sample. However, by using a central estimate from the literature that institutional delivery lowers the probability of neonatal death by 0.29 in low- and middle-income countries,23 we estimate that the introduction of vouchers would produce a 3% relative reduction in neonatal mortality.

In our study, voucher schemes were associated mainly with a shift from delivery at home to delivery in public health centres. There was no significant effect on the probability of delivery in public hospitals. Nor was there a significant effect on the caesarean section rate (data not reported). Although no data were available on the direct effect of vouchers on referrals, the fact that vouchers did not influence the probability of delivery in a public hospital or the caesarean section rate suggests that voucher schemes were not encouraging health centres either to refrain from referring problematic cases to hospitals so they could retain the reimbursement or to prefer normal deliveries and leave complicated deliveries unsupervised at home.24 Moreover, any unintended incentive to refrain from referring problematic deliveries to hospital is minimized with universal voucher schemes, which ensure that health centres are paid even when a referral is made. Furthermore, when we analysed deliveries at home according to whether the birth was supervised by a skilled attendant or an untrained attendant, usually a traditional birth attendant, we found no significant effects of vouchers on the former category (data not reported), which suggests that vouchers encouraged women who would otherwise have given birth at home without a skilled attendant to give birth in a health centre.

The effect of voucher schemes on the probability of delivery in a public health-care facility was significant for poor women but not for non-poor women. This observation was true even for universal schemes, which suggests that mainly the poorest women were encouraged by vouchers to give birth in a public facility, perhaps because of a perception that the quality of care is lower and staff attitudes are worse than in private facilities.13 Targeting may, therefore, increase the administrative costs of a voucher scheme without having an effect on how different population groups benefit from the vouchers.

Only universal voucher schemes had a significant impact on the probability of receiving antenatal care. This may have been because universal voucher schemes funded more antenatal care visits than targeted schemes (Table 1) and because they were designed to reimburse the package of care as a whole. However, both schemes did increase the probability of receiving postnatal care from a skilled provider, but the effect was significant only among non-poor women, perhaps because more women were classified as non-poor than poor. Moreover, we had no information on where postnatal care was received and it is possible that the existence of voucher schemes increased awareness among non-poor women and encouraged them to visit private facilities.

The only other study of a maternal health-care voucher scheme that was capable of quantifying its effects was carried out in Bangladesh. It found a slightly larger increase in the probability of institutional delivery than our study – 14 pp – and a much larger increase in the probability of receiving three antenatal care visits – 24 pp.1 However, the Bangladesh scheme was more generous and included a US$ 30 conditional cash transfer.

The nonrandomized implementation of voucher schemes in Cambodia prevents us from ruling out the possibility that our findings may have been biased by the existence of another programme, or some other confounder, that was present at the same time as the voucher schemes and may have influenced the utilization of maternity care. However, we reduced the risk of this occurring by controlling for the presence of various performance-based financing and fee waiver schemes. In addition, we also reduced the risk of bias by controlling for child, mother and household characteristics, which helped to ensure that the composition of the intervention and control groups was comparable over time. Our assumption that there was a common trend in the way the use of maternal health care would have changed in intervention and control districts in the absence of vouchers was supported by data showing that the trends in maternity care use and covariates were similar in intervention and control districts before the introduction of voucher schemes and by the observation that there was no difference between intervention and control districts in the trends in covariates after their introduction.

Since we estimated the effect of a voucher scheme on all pregnant women living in the district in which it was operating, the effect should be interpreted as an intention-to-treat effect. Consequently, if coverage of the target population was incomplete, the actual effect of the voucher scheme would have been greater.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our results suggest that voucher schemes for maternity care in public health-care facilities can increase deliveries in health centres and, to a lesser extent, improve antenatal and postnatal care. Unfortunately we were not able to assess the cost-effectiveness of voucher schemes in Cambodia because we had no data on costs. Cost information is important for comparing voucher schemes for public health care with conditional cash transfer schemes or schemes in which vouchers can be traded for care provided by the private sector with the aim of stimulating competition between providers and improving quality.

Acknowledgements

We thank Timothy Johnston and Emre Ozcan, previously at the Phnom Penh office of the World Bank, Joan Bastide and individuals who commented on our work at HEFPA workshops in Hanoi and Yogjakarta, the Second Global Symposium on Health Systems Research in Beijing, the PBF workshop in Bergen and at the 9th iHEA World Congress in Sydney.

Funding:

The study was funded through EU-FP7 research grant HEALTH-F2-2009-223166-HEFPA on Health Equity and Financial Protection in Asia. Ellen Van de Poel was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (Veni project 451-11-031).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

- 1.Nguyen HTH, Hatt L, Islam M, Sloan NL, Chowdhury J, Schmidt J-O, et al. Encouraging maternal health service utilization: an evaluation of the Bangladesh voucher program. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:989–96. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmed S, Khan MM. A maternal health voucher scheme: what have we learned from the demand-side financing scheme in Bangladesh? Health Policy Plan. 2011;26:25–32. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czq015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schmidt JO, Ensor T, Hossain A, Khan S. Vouchers as demand side financing instruments for health care: a review of the Bangladesh maternal voucher scheme. Health Policy. 2010;96:98–107. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh A, Mavalankar DV, Bhat R, Desai A, Patel SR, Singh PV, et al. Providing skilled birth attendants and emergency obstetric care to the poor through partnership with private sector obstetricians in Gujarat, India. Bull World Health Organ. 2009;87:960–4. doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abuya T, Njuki R, Warren CE, Okal J, Obare F, Kanya L, et al. A policy analysis of the implementation of a reproductive health vouchers program in Kenya. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:540. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janisch CP, Albrecht M, Wolfschuetz A, Kundu F, Klein S. Vouchers for health: a demand side output-based aid approach to reproductive health services in Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2010;5:578–94. doi: 10.1080/17441690903436573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agha S. Impact of a maternal health voucher scheme on institutional delivery among low income women in Pakistan. Reprod Health. 2011;8:10. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-8-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bellows NM, Bellows BW, Warren C. Systematic review: the use of vouchers for reproductive health services in developing countries: systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:84–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brody CM, Bellows N, Campbell M, Potts M. The impact of vouchers on the use and quality of health care in developing countries: a systematic review. Glob Public Health. 2013;8:363–88. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2012.759254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370:1358–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Measure DHS StatCompiler [Internet]. Fairfax (VA): ICF International; 2012. Available from: http://www.statcompiler.com/ [cited 2013 Nov 29].

- 12.Bathia MR, Gorter C. Improving access to reproductive and child health services in developing countries: are competitive voucher schemes an option? J Int Dev. 2007;19:975–81. doi: 10.1002/jid.1361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ir P, Horemans D, Souk N, Van Damme W. Using targeted vouchers and health equity funds to improve access to skilled birth attendants for poor women: a case study in three rural health districts in Cambodia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khim K, Annear PL. Strengthening district health service management and delivery through internal contracting: lessons from pilot projects in Cambodia. Soc Sci Med. 2013;96:241–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardeman W, Van Damme W, Van Pelt M, Por I, Kimvan H, Meessen B. Access to health care for all? User fees plus a Health Equity Fund in Sotnikum, Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:22–32. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Noirhomme M, Meessen B, Griffiths F, Ir P, Jacobs B, Thor R, et al. Improving access to hospital care for the poor: comparative analysis of four health equity funds in Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2007;22:246–62. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czm015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liljestrand J, Sambath MR. Socio-economic improvements and health system strengthening of maternity care are contributing to maternal mortality reduction in Cambodia. Reprod Health Matters. 2012;20:62–72. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(12)39620-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data–or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38:115–32. doi: 10.1353/dem.2001.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM. Recent developments in the econometrics of program evaluation. J Econ Lit. 2009;47:5–86. doi: 10.1257/jel.47.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puhani P. The treatment effect, the cross difference, and the interaction term in nonlinear “difference-in-differences” models. Econ Lett. 2012;115:85–7. doi: 10.1016/j.econlet.2011.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertrand M, Duflo E, Mullainathan S. How much should we trust differences-in-differences estimates? Q J Econ. 2004;119:249–75. doi: 10.1162/003355304772839588. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Angrist JD, Pischke JS. Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist's companion Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tura G, Fantahun M, Worku A.The effect of health facility delivery on neonatal mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 20131318. 10.1186/1471-2393-13-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jain A. Janani Suraksha Yojana and the maternal mortality rate. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010;XLV:15–6. [Google Scholar]