Abstract

Fibromodulin (FMOD) is an extracellular matrix (ECM) small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) that plays an important role in cell fate determination. Previous studies revealed that not only is FMOD critical in fetal-type scarless wound healing, but it also promotes adult wound closure and reduces scar formation. In addition, FMOD-deficient mice exhibit significantly reduced blood vessel regeneration in granulation tissues during wound healing. In this study, we investigated the effects of FMOD on angiogenesis, which is an important event in wound healing as well as embryonic development and tumorigenesis. We found that FMOD accelerated human umbilical vein endothelial HUVEC-CS cell adhesion, spreading, actin stress fiber formation, and eventually tube-like structure (TLS) network establishment in vitro. On a molecular level, by increasing expression of collagen I and III, angiopoietin (Ang)-2, and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), as well as reducing the ratio of Ang-1/Ang-2, FMOD provided a favorable network to mobilize quiescent endothelial cells to an angiogenic phenotype. Moreover, we also confirmed that FMOD enhanced angiogenesis in vivo by using an in ovo chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay. Therefore, our data demonstrate that FMOD is a pro-angiogenic and suggest a potential therapeutic role of FMOD in the treatment of conditions related to impaired angiogenesis.

Keywords: Fibromodulin, Human endothelial HUVEC-CS cells, Angiogenesis, Tube-like structure formation, In ovo chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay

1. Introduction

The formation of new capillaries, aka ‘angiogenesis’, is an important natural process required for embryonic development, wound healing, and tumor formation [1,2,3]. During angiogenesis, normally quiescent endothelial cells (ECs) are stimulated to switch to an angiogenic phenotype, and undergo a cascade of events regulated by a diverse group of growth factors to complete vessel maturation [2,4,5]. Otherwise, blockage of endothelial interactions with the extracellular matrix (ECM) inhibits neovascularization in vivo as well as the formation of endothelial tube-like structures (TLS) in vitro [4,6,7,8], which suggests ECM molecules are also critical for angiogenesis [9,10,11,12].

Fibromodulin (FMOD) is a broadly distributed ECM protein [13] that plays an extensive role in cell fate determination, as FMOD is an integral component for maintenance of endogenous stem cell niches [14] and can directly reprogram somatic cells to a minimally proliferative, multipotent progenitor state [15]. Meanwhile, FMOD is critical for fetal-type scarless wound repair, exerts anti-scarring effects in adult wound healing, and modulates transforming growth factor (TGF)-β ligand and receptor expression [16,17,18,19]. Since FMOD-deficient mice exhibit significantly reduced blood vessel regeneration in granulation tissues during wound healing [19], FMOD may also be involved in angiogenesis.

To investigate the role of FMOD in angiogenesis, we firstly evaluated the effects of FMOD on human umbilical vein endothelial HUVEC-CS cell TLS formation. Then, we assessed FMOD’s influence on cell adhesion, spreading, proliferation, and gene expression. Chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay was used to confirm FMOD’s effect of angiogenesis in vivo.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Cell culture

HUVEC-CS cells (passages 4-6; CRL-2873; ATCC, Manassas, VA) were cultured in DMEM supplied with 20% inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY).

2.2. TLS formation analysis

3 × 104 cells/cm2 HUVEC-CS cells were seeded into 6-well plates for 24 h before treatment with 3 ml fresh medium supplying 0, 2, 10 or 50 μg/ml recombinant human FMOD [15,19]. Media were changed every 3 days. On day-15, cells were fixed in 4%-paraformaldehyde in phosphate buffered saline (PBS). Five images per well, four wells per treatment were documented using an Olympus fluorescent microscope (Center Valley, PA). Images were assessed by recording dimensional and topological analyses with Image J (NIH, Bethesda, MD) [20]. Segment length of TLS is defined as the individual TLS length from one junction to the next. Calcium deposits were identified by Alizarin Red (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) staining [21].

2.3. Cell adhesion and spreading analysis

4-well Millicell® EZ slides (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) were coated with Attachment Factor (0.1% gelatin; Life Technologies) at 37°C for 30 min. 3 × 104 cells/cm2 HUVEC-CS cells were seeded with 0.5 ml fresh medium containing 0, 2, 10 or 50 μg/ml FMOD. After 3 h (which corresponds to the time when the collagen overlay was applied [22]), non-adhering cells were removed by a gentle wash with ice-cold PBS. After fixation, cells were stained with mouse anti-human monoclonal antibodies against vinculin (Abcam, Cambridge, CA) followed by Alexa Fluor® 594-labeled anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies). Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled phalloidin (Life Technologies) and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma-Aldrich) were used to stain actin filaments and nuclei, respectively. Six images per well, four wells per treatment were recorded and analyzed. Vinculin and actin filaments staining were documented with a confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM; Leica Microsystems Inc., Buffalo Grove, IL).

2.4. Cell proliferation analysis

6 × 103 cells/cm2 HUVEC-CS cells were seeded into a 96-well plate for 24 h before treatment with 200 μl fresh medium with 0, 2, 10 or 50 μg/ml FMOD. Cell proliferation was measured by Vybrant® MTT Cell Proliferation Assay Kit (Life Technologies).

2.5 Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

Cells were collected on day-5, -10, and -15 during TLS formation assay. RNA was extracted using RNeasy® Mini Kit with DNase treatment (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) followed by reverse transcription (RT) using iScript™ Reverse Transcription Supermix for RT-qPCR (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). qRT-PCR of pro-α1 chain of collagen III (Col3α1; prime 1: 5′-TCTTGGTCAGTCCTGTGCGGATA-3′, prime 2: 5′-AACGGATCCTGAGTCACAGACA-3′ [23]) and tyrosine kinase receptors 2 (Tie2; primer 1: 5′-TTGAAGTGGAGAGAAGGTCTG-3′, primer 2: 5′-GTTGACTCATAGCTCGGACCAC-3′ [24]) was performed on a 7300 Real-Time PCR system (Life Technologies) with iTaq™ Universal SYBR® Green Supermix (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Quantitation of other genes was accessed by using TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Life Technologies) and SsoFast™ Probes Supermix with ROX (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Concomitant GAPDH was also performed in separate tubes for each RT reaction as housekeeping standard. For each gene, three separate sets of qRT-PCR analyses were performed using different cDNA templates.

2.6. CAM assay

The in ovo CAM assay was performed as previously described [25]. Fertilized chicken eggs (Charles River Labs, North Franklin, CT) were positioned in a horizontal position and incubated at 37°C under 60% relative humidity in an egg incubator equipped with a turner which automatically turned eggs 6 times/day. On day-3, 5 ml albumin was withdrawn using a syringe with a 21-gauge needle through the pointer end of the egg in order to allow detachment of the developing CAM from the eggshell. A rectangle window was cut in the shell as a portal of access for the CAM, and then the eggs were returned back to the incubator. On day-10, 2.0 mg/ml FMOD mixed with 30 μl 1:3-diluted growth factor reduced Matrigel (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ) was loaded on an autoclaved 5 × 5-mm polyester mesh layer (grid size: 530 μm; Component Supply Company, Fort Meade, FL), and was incubated for 45 min at 37°C for gel formation before transplantation on the CAM. On day-13, CAMs were excised, fixed, and photographed.

2.7. Statistical analysis

Generally, data were presented as mean ± the standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical significance was performed with OriginPro 8 (Origin Lab Corp., Northampton, MA) including one-way ANOVA, two-sample t-test, and Mann-Whitney analyses. A P-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

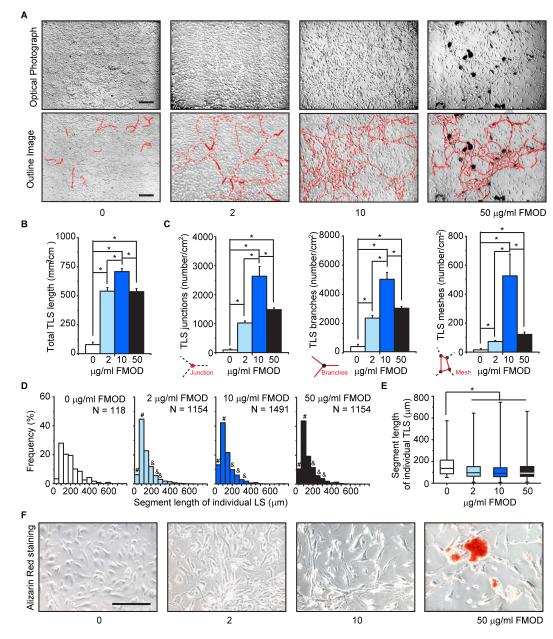

3.1. FMOD promoted HUVEC-CS cell TLS formation

High-density cultured HUVEC-CS cells formed a confluent monolayer with a characteristic polygonal morphology. On day-15, several HUVEC-CS cells spontaneously sprouted and connected with each other to form TLSs on the monolayer, as previously described in adult bovine aorta ECs [26]. Compared to non-FMOD controls, FMOD administration extensively enhanced HUVEC-CS TLS formation, and induced these TLSs to establish polygon structures referred to as complex meshes (Fig. 1A), which indicates rapid cell migration [27]. FMOD significantly increased both dimensional (total length of cellular TLS network per area; Fig. 1B) and topological parameters (number of junctions, branches, and meshes per area; Fig. 1C) of TLSs. As a result, more short (0-100 μm) and less long (150-300 μm) individual TLSs (Fig. 1D, E) were observed in FMOD-treated groups (Fig. 1D, E). Interestingly, FMOD promoted TLS formation in a dose-dependent manner in a range of 0-10 μg/ml, while 50 μg/ml FMOD significantly lowered both dimensional and topological parameters of TLSs compared with that of 10 μg/ml FMOD (Fig. 1B, C). Moreover, 50 μg/ml FMOD also resulted in calcified nodule-like cluster formation (Fig. 1A, F).

Fig. 1.

FMOD promoted HUVEC-CS TLS formation in vitro. (A) On day-15, HUVEC-CS cells spontaneously formed TLSs (outlined in the lower panel). (B) Dimensional and (C) topological parameters of the HUVEC-CS TLS network were quantitated; N = 4. (D) Distribution of TLS segment length in FMOD-treated groups was compared to non-FMOD (0 μg/ml FMOD) control. # and & indicated higher and lower frequency, respectively. (E) The median (center line), 25%-75% percentiles (box) and lowest and highest values (bars) of TLS segment length were also shown and analyzed by Mann-Whiney test. (F) Alizarin Red staining demonstrated calcified cluster formation in 50 μg/ml FMOD group. Bar = 200 μm. *, significant difference compared to non-FMOD control (B, C, and E).

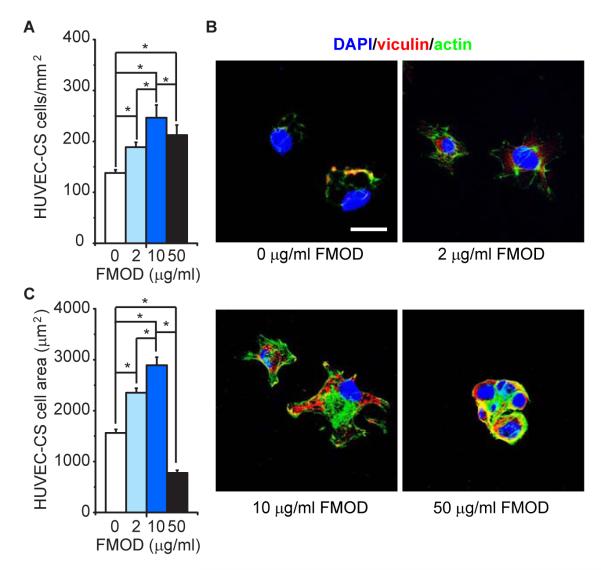

3.2. FMOD accelerated HUVEC-CS cell attachment and spreading, but not cellular proliferation

FMOD significantly improved HUVEC-CS cell adhesion (Fig. 2A). For instance, 10 μg/ml FMOD resulted in approximately 82% (2.46 × 104 cell/cm2) seeded cell attachment in the first 3 h, while only 46% (1.38 × 104 cell/cm2) adhered in the non-FMOD control group during the same period. It is also worth noting that fewer cells adhered in 50 μg/ml FMOD (2.12 × 104 cell/cm2) than in 10 μg/ml FMOD (Fig. 2A). Immune staining revealed only a small amount of vinculin-positive focal adhesion and actin stress fibers in attached non-FMOD-treated cells, while vinculin staining was co-located with actin fibers (Fig. 2B). On the contrary, FMOD significantly induced vinculin expression and actin stress fiber formation (Fig. 2B). Clear vinculin and actin stress fiber staining was observed in 2 μg/ml FMOD-treated cells (Fig 2B). In 10 μg/ml FMOD-treated cells, vinculin was intensively expressed and organized as special network throughout the cell body. Phalloidin staining also evidenced an abundant number of actin stress fibers in the cytoplasm as well as cell edge, suggesting cellular spreading and migration (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, 50 μg/ml FMOD-treated cells aggregated to form cellular clusters surrounded by aggregated vinculin and actin stress fibers (Fig. 2B). Cells were significantly more spread out when treated with 2 and 10 μg/ml FMOD compared to non-FMOD treatment (Fig. 2C). However, 50 μg/ml FMOD-treated cells adopted a “rounder” morphology in cell cluster (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

FMOD promoted HUVEC-CS adhesion and spreading in vitro. (A) Adhered HUVEC-CS cells were calculated after 3 h cultivation. (B) Adhered cells were stained with antibody against vinculin and Alexa Fluor® 488-labeled phalloidin. Nuclei were stained by DAPI. (C) Area of adhered cells was also calculated after 3 h cultivation. *, significant difference; N = 4. Bar = 30 μm.

Meanwhile, in order to exclude the possibility that the inducing effect of FMOD on HUVEC-CS cell TLS formation was the result of stimulating cellular proliferation, cellular viability of HUVEC-CS during culture was quantified. In comparison with non-FMOD controls, there was no significant difference in HUVEC-CS cell viability in 2 and 10 μg/ml FMOD cultivation during the entire experimental period (Supplementary Fig. 1). Significant reduction of HUVEC-CS viability was observed in long-term (day-9) cultivation with 50 μg/ml of FMOD; however, a decrease of HUVEC-CS cell viability was not evidenced at earlier time points (Supplementary Fig. 1).

3.3. FMOD orchestrated HUVEC-CS cell gene expression in favor of angiogenesis

2 μg/ml FMOD did not notably affect type I or type III collagen expression in HUVEC-CS cells. However, by increasing the concentration of FMOD to 10 and 50 μg/ml, type I and type III collagen expression was significantly elevated (Supplementary Fig. 2A, B). FMOD also stimulated HUVEC-CS angiopoietin (Ang)-2 expression in a dose-dependent manner (Supplementary Fig. 2C). On the other hand, expression of Tie2, the predominant receptor of Ang-1 and Ang-2 signals [28], did not respond to FMOD treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2D). Interestingly, high dose (10 and 50 μg/ml) FMOD slightly inhibited Ang-1 expression in long-term (10 and 15 days) cultivation (Supplementary Fig. 3A), while the well-known angiogenesis growth factor vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression in HUVEC-CS cells was considerably upregulated by FMOD administration (Supplementary Fig. 3B).

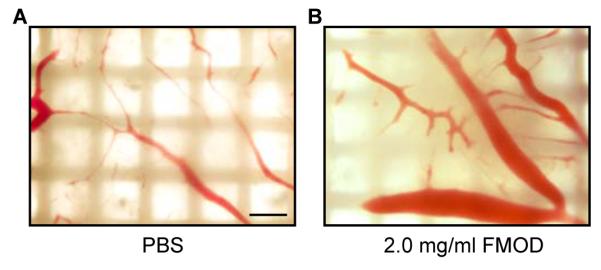

3.4. FMOD enhanced in vivo angiogenesis

Using the in ovo CAM assay, we further examined the in vivo pro-angiogenic potential of FMOD. Macroscopic observation showed that CAMs in the non-FMOD treated group had only a few slim blood vessels on day-13 (Fig. 3A). On the other hand, a significant increase of blood vessels with large diameters was documented in CAMs treated with FMOD (Fig. 3B). Therefore, FMOD also promoted angiogenesis in vivo.

Fig. 3.

FMOD promoted in vivo angiogenesis. Macroscopic photographs of blood vessel generation on CAM treated with (A) non-FMOD PBS control and (B) 2.0 mg/ml FMOD on day-13. Bar = 500 μm.

4. Discussion

Structurally, FMOD is a member of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan (SLRP) family, which also comprises decorin, biglycan, and lumican [13]. SLRPs are distributed in the ECM of all tissues and the thin membranes that envelop all major parenchymal organs such as pericardium, pleura, periosteum, perimysium, and adventitia of blood vessels [12]. The involvement of decorin and lumican in angiogenesis has been intensively studied [12]. For example, lumican inhibits angiogenesis by interfering with integrin α2β1 activity and downregulating proteolytic activity associated with surface membranes of ECs [29]. Meanwhile, decorin seems to be pro-angiogenic in some early experimental settings [12,30], but it inhibits EC migration and TLS formation in vitro [12,22,31]. Additionally, decorin-deficiency markedly increases fibrovascular invasion and enhances the formation of blood vessels in vivo [32]. Additional studies demonstrated that the anti-angiogenic activity of decorin relies on blocking angiogenic signals [12,22,31,33,34], especially during pathological angiogenesis such as that in malignant vascular tumors [35,36]. It is likely that decorin plays a dual moderator role on angiogenesis.

Unlike decorin and lumican, our present results showed that FMOD significantly stimulated EC TLS formation in vitro as well as blood vessel generation in vivo. In addition, FMOD-deficiency reduced blood vessel regeneration in adult rodent cutaneous wounds [19]. In the aspect of cellular behavior, FMOD remarkably enhanced EC cell adhesion, spreading, and actin stress fiber formation. Previous studies already highlighted the importance of mechanical-tension interactions between ECs and their substrate to promote TLS formation in vitro [37]. It is possible that FMOD may be responsible for providing a permissive microenvironment for EC actin stress fiber formation and cell spreading during TLS organization, since FMOD plays important roles in ECM assembly, organization, and degradation [12,38,39]. Meanwhile, not only do SLRPs play structural functions in the ECM of all tissues, but they are also signaling molecules that regulate intracellular signaling cascades and determine cell fate [15,40]. Our previous studies have revealed that FMOD modulates TGF-β expression, distribution, and bioactivity in an isoform-dependent manner [19,41]. Thus, it is also possible that FMOD interferes with the activation of integrins or other cell surface receptors that initiate the formation of actin stress fibers and adhesion contacts, thus promoting cytoskeletal reorganization for spreading and TLS formation in vitro. On a molecular level, in vitro angiogenesis is correlated to ECM protein expression [9,11,26]. For instance, collagen I initiates quiescent ECs morphogenesis leading to the formation of TLSs [11,26], while collagen I and III both contribute to vessel wall stability [9,42]. In the aspect of signal transduction, we also found that FMOD enhanced HUVEC-CS cell collagen I and III expression, which correlates with the increase of TLS network organization. In addition, the Ang/Tie signaling system is essential for vessel remodeling and maturation [28]. Ang-1 is predominantly expressed in perivascular cells, and binds to Tie2 receptors resulting in promotion of EC survival signaling, the maintenance of an endothelial barrier, and a quiescent vasculature [28]. Expressed by ECs, Ang-2 acts mainly as an antagonist for Tie2 receptor signaling by displacing the more active ligand Ang-1 from the receptor [28]. However, Ang-2 also has a direct pro-angiogenic Tie2-independent role [28]. In this study, we also showed that FMOD stimulated Ang-2 expression, slightly reduced Ang-1 level, but did not affect Tie2 transcription in HUVEC-CS cells, which suggests that FMOD mobilized quiescent ECs for angiogenesis, at least partially, via reducing Ang-1/Ang-2 ratios which are critical in balancing Tie2-mediated signaling and regulating vascular homeostasis and responsiveness to other angiogenic cues [28]. Furthermore, FMOD also induced VEGF expression in HUVEC-CS cells, although ECs are not the main source of VEGF. Because Ang-2 promotes angiogenesis in the presence of VEGF [28,43], FMOD thus provides a special network to mobilize quiescent ECs to undergo angiogenesis. Together, these findings strongly suggested that FMOD exhibits pro-angiogenic properties though multiple pathways.

It is also worthy to note that 50 μg/ml FMOD induced HUVEC-CS aggregation, sharply increased expression of collagen I, III and Ang-2, and eventually resulted in calcification in vitro. These phenomena suggest that excessive FMOD levels will result in EC dysfunction. Actually, FMOD was found to regulate tumor stromal structure, which is characterized by distorted blood vessels accompanied by elevated interstitial fluid pressure [39]. Considering the fact that massive FMOD expression was found in different malignancies [39,44,45], there seems to be a direct link between tumor progression and FMOD (and maybe other SLRPs too) [9,46].

In conclusion, we demonstrated that FMOD is capable of promoting angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Our findings indicate FMOD’s pro-angiogenic properties are due to its powerful orchestrating of pro- and anti-angiogenic signaling. Our results provide novel insights into angiogenesis regulation, suggesting a potential therapeutic application of FMOD in wound healing and cancer therapy as well as other conditions related to abnormal blood vessel generation.

Supplementary Material

Research Highlights.

Fibromodulin (FMOD) enhanced HUVEC-CS cell tube-like structure formation in vitro

FMOD accelerated HUVEC-CS cell attachment and spreading

FMOD stimulated pro-angiogenesis gene expression in HUVEC-CS cells

FMOD also improved angiogenesis in vivo

Acknowledgements

We apologize to all colleagues whose important work we could not cite due to space restrictions. This study was supported by the, Plastic Surgery Research Foundation (2013 National Endowment for Plastic Surgery), and NIH-NIAMS (R43 AR064126). CLSM was performed at the Center for NanoScience Institute Advanced Light Microscopy/Spectroscopy Shared Resource Facility at UCLA, which was supported by funding from NIH-NCRR shared resources grant (CJX1-443835-WS-29646) and NSF Major Research Instrumentation grant (CHE-0722519).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures Drs. K. T., C. S., and Z. Z. are inventors on fibromodulin-related patent filed from UCLA. Drs. K. T., C. S., and Z. Z. are founders of Scarless Laboratories Inc., which sublicenses fibromodulin-related patents from the US Regents. Dr. Soo is also an officer of Scarless Laboratories, Inc.

References

- [1].Breier G. Angiogenesis in embryonic development--a review. Placenta. 2000;21(Suppl A):S11–15. doi: 10.1053/plac.1999.0525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Eming SA, Brachvogel B, Odorisio T, Koch M. Regulation of angiogenesis: Wound healing as a model. Progress in Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 2007;42:115–170. doi: 10.1016/j.proghi.2007.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Nussenbaum F, Herman IM. Tumor angiogenesis: insights and innovations. J Oncol. 2010;(2010):132641. doi: 10.1155/2010/132641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Friedlander M, Brooks PC, Shaffer RW, Kincaid CM, Varner JA, Cheresh DA. Definition of 2 Angiogenic Pathways by Distinct Alpha(V) Integrins. Science. 1995;270:1500–1502. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5241.1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Belotti D, Foglieni C, Resovi A, Giavazzi R, Taraboletti G. Targeting angiogenesis with compounds from the extracellular matrix. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2011;43:1674–1685. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Britsch S, Christ B, Jacob HJ. The influence of cell-matrix interactions on the development of quail chorioallantoic vascular system. Anat Embryol (Berl) 1989;180:479–484. doi: 10.1007/BF00305123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Davis GE, Camarillo CW. An alpha 2 beta 1 integrin-dependent pinocytic mechanism involving intracellular vacuole formation and coalescence regulates capillary lumen and tube formation in three-dimensional collagen matrix. Experimental Cell Research. 1996;224:39–51. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Stromblad S, Cheresh DA. Cell adhesion and angiogenesis. Trends in Cell Biology. 1996;6:462–468. doi: 10.1016/0962-8924(96)84942-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sottile J. Regulation of angiogenesis by extracellular matrix. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Reviews on Cancer. 2004;1654:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Krishnan L, Hoying JB, Nguyen H, Song H, Weiss JA. Interaction of angiogenic microvessels with the extracellular matrix. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 2007;293:H3650–H3658. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00772.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Whelan MC, Senger DR. Collagen I initiates endothelial cell morphogenesis by inducing actin polymerization through suppression of cyclic AMP and protein kinase A. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:327–334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207554200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Iozzo RV, Goldoni S, Berendsen AD, Young MF. In: Small Leucine-Rich Proteoglycans: The Extracellular Matrix: an Overview. Mecham RP, editor. Springer; Berlin Heidelberg: 2011. pp. 197–231. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Heinegard D, Antonsson P, Hedbom E, Larsson T, Oldberg A, Sommarin Y, Wendel M. Noncollagenous matrix constituents of cartilage. Pathol Immunopathol Res. 1988;7:27–31. doi: 10.1159/000157088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Bi Y, Ehirchiou D, Kilts TM, Inkson CA, Embree MC, Sonoyama W, Li L, Leet AI, Seo BM, Zhang L, Shi S, Young MF. Identification of tendon stem/progenitor cells and the role of the extracellular matrix in their niche. Nat Med. 2007;13:1219–1227. doi: 10.1038/nm1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zheng Z, Jian J, Zhang XL, Zara JN, Yin W, Chiang M, Liu Y, Wang J, Pang S, Ting K, Soo C. Reprogramming of human fibroblasts into multipotent cells with a single ECM proteoglycan, fibromodulin. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5821–5831. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Soo C, Hu F, Zhang X, Wang Y, Beanes S, Lorenz H, Hedrick M, Mackool R, Plaas A, Kim S, Longaker MT, Freymiller E, Ting K. Differential expression of fibromodulin, a transforming growth factor-β modulator, in fetal skin development and scarless repair. Am J Pathol. 2000;157:423–433. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)64555-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Soo C, Beanes S, Dang C, Zhang X, Ting K. Fibromodulin, a TGF-ß modulator, promotes scarless fetal repair. Surgical Forum. 2001:578–581. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Stoff A, Rivera AA, Mathis JM, Moore ST, Banerjee NS, Everts M, Espinosa-de-los-Monteros A, Novak Z, Vasconez LO, Broker TR, Richter DF, Feldman D, Siegal GP, Stoff-Khalili MA, Curiel DT. Effect of adenoviral mediated overexpression of fibromodulin on human dermal fibroblasts and scar formation in full-thickness incisional wounds. J Mol Med. 2007;85:481–496. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0148-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Zheng Z, Nguyen C, Zhang XL, Khorasani H, Wang JZ, Zara JN, Chu F, Yin W, Pang S, Le A, Ting K, Soo C. Delayed Wound Closure in Fibromodulin-Deficient Mice Is Associated with Increased TGF-beta 3 Signaling. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2011;131:769–778. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Carpentier G. Contribution: Angiogenesis analyzer for ImageJ. ImageJ News. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- [21].Osako MK, Nakagami H, Koibuchi N, Shimizu H, Nakagami F, Koriyama H, Shimamura M, Miyake T, Rakugi H, Morishita R. Estrogen inhibits vascular calcification via vascular RANKL system: common mechanism of osteoporosis and vascular calcification. Circ Res. 2010;107:466–475. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.216846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Davies C.d.L., Melder RJ, Munn LL, Mouta-Carreira C, Jain RK, Boucher Y. Decorin inhibits endothelial migration and tube-like structure formation: role of thrombospondin-1. Microvasc Res. 2001;62:26–42. doi: 10.1006/mvre.2001.2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Dooley TP, Reddy SP, Wilborn TW, Davis RL. Biomarkers of human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma from tissues and cell lines identified by DNA microarrays and qRT-PCR. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2003;306:1026–1036. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)01099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Thijssen VLJL, Brandwijk RJMGE, Dings RPM, Griffioen AW. Angiogenesis gene expression profiling in xenograft models to study cellular interactions. Experimental Cell Research. 2004;299:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].West DC, Thompson WD, Sells PG, Burbridge MF. Angiogenesis Assays Using Chick Chorioallantoic Membrane. In: Murray JC, editor. Methods in Molecular Medicine. 46, Angiogenesis Protocols. Humana Press Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 2011. pp. 107–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Iruela-Arispe ML, Hasselaar P, Sage H. Differential expression of extracellular proteins is correlated with angiogenesis in vitro. Lab Invest. 1991;64:174–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Aranda E, Owen GI. A semi-quantitative assay to screen for angiogenic compounds and compounds with angiogenic potential using the EA.hy926 endothelial cell line. Biol Res. 2009;42:377–389. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Fagiani E, Christofori G. Angiopoietins in angiogenesis. Cancer Letters. 2013;328:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Niewiarowska J, Brezillon S, Sacewicz-Hofman I, Bednarek R, Maquart FX, Malinowski M, Wiktorska M, Wegrowski Y, Cierniewski CS. Lumican inhibits angiogenesis by interfering with alpha2beta1 receptor activity and downregulating MMP-14 expression. Thromb Res. 2011;128:452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Schonherr E, Sunderkotter C, Schaefer L, Thanos S, Grassel S, Oldberg A, Iozzo RV, Young MF, Kresse H. Decorin deficiency leads to impaired angiogenesis in injured mouse cornea. J Vasc Res. 2004;41:499–508. doi: 10.1159/000081806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Neill T, Painter H, Buraschi S, Owens RT, Lisanti MP, Schaefer L, Iozzo RV. Decorin antagonizes the angiogenic network: concurrent inhibition of Met, hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha, vascular endothelial growth factor A, and induction of thrombospondin-1 and TIMP3. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:5492–5506. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.283499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Jarvelainen H, Puolakkainen P, Pakkanen S, Brown EL, Hook M, Iozzo RV, Sage EH, Wight TN. A role for decorin in cutaneous wound healing and angiogenesis. Wound Repair Regen. 2006;14:443–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Sulochana KN, Fan HP, Jois S, Subramanian V, Sun F, Kini RM, Ge RW. Peptides derived from human decorin leucine-rich repeat 5 inhibit angiogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280:27935–27948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414320200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Mimura T, Han KY, Onguchi T, Chang JH, Kim TI, Kojima T, Zhou ZJ, Azar DT. MT1-MMP-Mediated Cleavage of Decorin in Corneal Angiogenesis. J Vasc Res. 2009;46:541–550. doi: 10.1159/000226222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Salomaki HH, Sainio AO, Soderstrom M, Pakkanen S, Laine J, Jarvelainen HT. Differential expression of decorin by human malignant and benign vascular tumors. Journal of Histochemistry & Cytochemistry. 2008;56:639–646. doi: 10.1369/jhc.2008.950287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Theocharis AD, Skandalis SS, Tzanakakis GN, Karamanos NK. Proteoglycans in health and disease: novel roles for proteoglycans in malignancy and their pharmacological targeting. Febs Journal. 2010;277:3904–3923. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ingber DE, Folkman J. Mechanochemical Switching between Growth and Differentiation during Fibroblast Growth Factor-Stimulated Angiogenesis Invitro - Role of Extracellular-Matrix. Journal of Cell Biology. 1989;109:317–330. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Merline R, Schaefer RM, Schaefer L. The matricellular functions of small leucine-rich proteoglycans (SLRPs) J Cell Commun Signal. 2009;3:323–335. doi: 10.1007/s12079-009-0066-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Oldberg A, Kalamajski S, Salnikov AV, Stuhr L, Morgelin M, Reed RK, Heldin NE, Rubin K. Collagen-binding proteoglycan fibromodulin can determine stroma matrix structure and fluid balance in experimental carcinoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:13966–13971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702014104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Iozzo RV, Schaefer L. Proteoglycans in health and disease: novel regulatory signaling mechanisms evoked by the small leucine-rich proteoglycans. Febs Journal. 2010;277:3864–3875. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zheng Z, Nguyen K, Wang JZ, Zhang X, Ting K, Soo C. Differential expression of transforming growth factor (TGF)-betas and TGF-beta receptors during skin wound healing in adult mice with fibromodulin (FMOD) deficiency. Wound Repair and Regeneration. 2008;16:A28–A28. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Folkman J, DAmore PA. Blood vessel formation: What is its molecular basis? Cell. 1996;87:1153–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81810-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Hanahan D. Signaling vascular morphogenesis and maintenance. Science. 1997;277:48–50. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Mayr C, Bund D, Schlee M, Moosmann A, Kofler DM, Hallek M, Wendtner CM. Fibromodulin as a novel tumor-associated antigen (TAA) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which allows expansion of specific CD8(+) autologous T lymphocytes. Blood. 2005;105:1566–1573. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-04-1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mikaelsson E, Danesh-Manesh AH, Luppert A, Jeddi-Tehrani M, Rezvany MR, Sharifian RA, Safaie R, Roohi A, Osterborg A, Shokri F, Mellstedt H, Rabbani H. Fibromodulin, an extracellular matrix protein: characterization of its unique gene and protein expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia and mantle cell lymphoma. Blood. 2005;105:4828–4835. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-10-3941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Iozzo RV, Sanderson RD. Proteoglycans in cancer biology, tumour microenvironment and angiogenesis. J Cell Mol Med. 2011;15:1013–1031. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01236.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.