Abstract

Background:

Organically produced foods are less likely than conventionally produced foods to contain pesticide residues.

Methods:

We examined the hypothesis that eating organic food may reduce the risk of soft tissue sarcoma, breast cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and other common cancers in a large prospective study of 623 080 middle-aged UK women. Women reported their consumption of organic food and were followed for cancer incidence over the next 9.3 years. Cox regression models were used to estimate adjusted relative risks for cancer incidence by the reported frequency of consumption of organic foods.

Results:

At baseline, 30%, 63% and 7% of women reported never, sometimes, or usually/always eating organic food, respectively. Consumption of organic food was not associated with a reduction in the incidence of all cancer (n=53 769 cases in total) (RR for usually/always vs never=1.03, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.99–1.07), soft tissue sarcoma (RR=1.37, 95% CI: 0.82–2.27), or breast cancer (RR=1.09, 95% CI: 1.02–1.15), but was associated for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (RR=0.79, 95% CI: 0.65–0.96).

Conclusions:

In this large prospective study there was little or no decrease in the incidence of cancer associated with consumption of organic food, except possibly for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Keywords: organic food, cancer, cohort, women

Organic food production involves avoiding artificial fertilisers and pesticides and using crop rotation and other forms of husbandry to maintain soil fertility, control weeds and diseases. All food sold as organic in the United Kingdom must be certified as organic by approved organic Control Bodies (Defra, 2013). The market for organic foods in the United Kingdom has grown rapidly during the last 20 years: sales of organic food products totalled £100 million in 1993/4 and over £2 billion at the peak of the market growth in 2008 (Soil Association, 2004, 2009). Since 2008, sales of organic food in the United Kingdom have declined slightly, but still account for a significant share of the market (Defra 2012; Soil Association, 2012). Dairy and ‘chilled convenience' products and fresh fruit and vegetables are the most commonly purchased organic products (Soil Association, 2013). The main reason for consumers to buy organic food is because they believe it to be healthier (Soil Association, 2013).

A systematic review on organic food (Smith-Spangler et al, 2012) compared pesticide residues between organic and conventional crops, and found that organic foods were less likely to be contaminated with any detectable pesticide residue. This review (Smith-Spangler et al, 2012) and another (Dangour et al, 2009) also compared the nutrient composition of organically and conventionally produced crops and found little difference for most nutrients, except a higher content of phosphorus in organic foods.

Occupational pesticide exposure has been linked, albeit not conclusively, with a higher risk of certain cancers, particularly non-Hodgkin lymphoma, soft tissue sarcoma, and breast cancer (Dich et al, 1997; Mostafalou and Abdollahi, 2013). Smith-Spangler et al (2012) noted a dearth of studies examining organic food consumption in relation to health outcomes, and to our knowledge, no study has investigated organic food consumption in relation to cancer risk.

In this study we investigated the relationship between the reported frequency of consumption of organic food and subsequent cancer incidence, overall and for 17 individual cancer sites or types in a large prospective study of middle-aged women in the United Kingdom.

Materials and Methods

Participants and data

In 1996–2001, 1.3 million middle-aged women who had been invited for breast cancer screening at screening centres throughout England and Scotland joined The Million Women Study by completing a study questionnaire and by giving written consent. Women have been re-surveyed about 3, 8, and 12 years after recruitment. Full details of the study design and methods are described elsewhere (The Million Women Study Collaborative Group, 1999), and study questionnaires can be viewed at www.millionwomenstudy.org.

All study participants are flagged on the National Health Service Central Registers, so that cancer registrations and deaths are routinely notified to the study investigators by the Office for National Statistics, England and the Information Services Division, Scotland. This information includes the date of each such event and codes the site and morphology of the cancer according to the International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-10 and ICD-0.

The study was approved by the Oxford and Anglia Multi-Centre Research Ethics Committee.

Baseline data on the consumption of organic food

At the 3-year survey, completed in 2002 on average, women were asked ‘Do you eat organic food?' with four possible categorical responses: ‘never, sometimes, usually, and always.' Women were also asked if they had changed their diet because of illness in the previous 5 years.

The same questions were asked at the 8-year survey.

Statistical analysis

The baseline for follow-up for this analysis was the 3-year survey when organic food consumption was first reported. The end of follow-up for cancer incidence was 31 December 2011. Eligible women contributed person-years from baseline until the date of registration with the cancer of interest, date of death, date of emigration, or end of follow-up, whichever was soonest. In addition, women diagnosed with any cancer other than the cancer of interest (except non-melanoma skin cancer) during the follow-up period were censored at the date of diagnosis of that cancer.

We examined cancer incidence in relation to frequency of consumption of organic food for all cancers combined (except non-melanoma skin cancer) and for 16 of the most common cancer sites or types of cancer: oral cavity and pharynx (C00–C14), oesophagus (C15), stomach (C16), colorectum (C18–C20), pancreas (C25), lung (C34), malignant melanoma (C43), breast (C50), endometrium (C54), ovary (C56), kidney (renal cell carcinoma) (C64), bladder (C67), brain (C71, C75.1–C75.3, C72, D32, D33, D35.2–D35.4, D42, D43, and D44.3–D44.5), non-Hodgkin lymphoma (C82–C85), multiple myeloma (C90), and leukaemia (C91–C95). We also examined the incidence of soft tissue sarcoma (C49) in relation to the frequency of consumption of organic food; this is a rare cancer but we analysed it because there was a prior hypothesis.

At the 3-year survey, 751 975 women reported their consumption of organic food. We excluded women diagnosed with any cancer other than non-melanoma skin cancer (C44) before baseline or who reported having changed their diet because of illness within the 5 years before baseline (128 895 excluded). For analyses of endometrial cancer, women who had a hysterectomy were excluded (157 755 excluded). For analyses of ovarian cancer, women who had a bilateral oophorectomy were excluded (72 059 excluded).

Cox regression models using attained age as the underlying time variable were used to estimate relative risks for incident cancer by the reported frequency of consumption of organic foods at baseline. All analyses were stratified by age, geographical region (10 regions corresponding to the areas covered by the cancer registries), and socioeconomic status (in fifths, based on the Townsend deprivation index (Townsend et al, 1988)). Analyses were adjusted for body mass index (BMI; <25 kg m-2, 25–29 kg m-2, and ⩾30 kg m-2); height (<1.60 m, 1.60–1.64 m, and ⩾1.65 m); smoking status (never, past, current <10 cigarettes per day, current 10–14 cigarettes per day, current 15–19 cigarettes per day, and current ⩾20 cigarettes per day); alcohol intake (none, 1–5, 6–10, and ⩾11 drinks per week); strenuous physical activity (never/rarely, less than once per week, and once or more per week); parity (0, 1, 2, and ⩾3 full-term pregnancies); age at first birth, (<25, 25–29, and ⩾30 years); fibre intake (grams per day, in fifths:<9.6, 9.6–12.2, 12.3–14.6, 14.7–17.5, and ⩾17.6); and type of meat eaten (none, poultry only, and red or processed meat). We assigned women with missing data for these adjustment variables to a separate category. Missing data accounted for <3% for any variable, except for BMI (7.3%) and alcohol consumption (11.3%). Information on socioeconomic status, height, parity, strenuous physical activity, and age at menarche was collected from the recruitment survey. Information on BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, fibre intake, and meat intake was collected from the 3-year survey. To investigate reverse causality, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding the first 3 years of follow-up. Analyses for breast cancer were additionally adjusted for hormone replacement therapy use (never, past, current, and not known) at baseline. For all cancers, we also restricted the analysis to women who reported never consuming organic food at baseline and at the 8-year survey, compared with women who reported usually or always consuming organic food at both study time points.

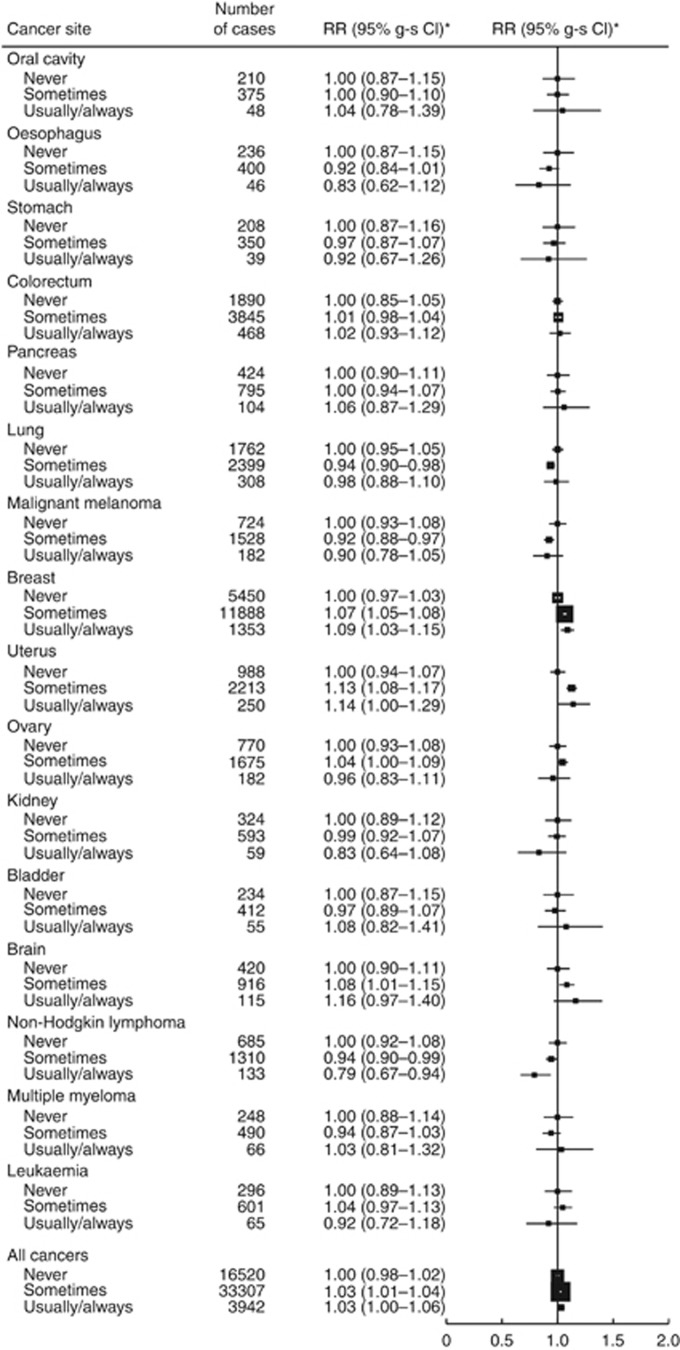

For individual cancer sites, relative risks are presented in the form of a plot, comparing women who usually/always ate organic food and women who sometimes ate organic food with women who never ate organic food. The position of the square indicates the value of the relative risk, and its area is inversely proportional to the variance of the logarithm of the risk in that group, indicating the amount of statistical information for that group alone. In Figure 2, because more than two groups were compared, variances were estimated by treating the relative risks as floating absolute risks, yielding group-specific confidence intervals (g-s CI) (Easton et al, 1991). The method does not alter the relative risks but enables valid comparisons between any two exposure groups, even when neither group is the reference group. When only two categories are compared (as in the text), conventional confidence intervals are used.

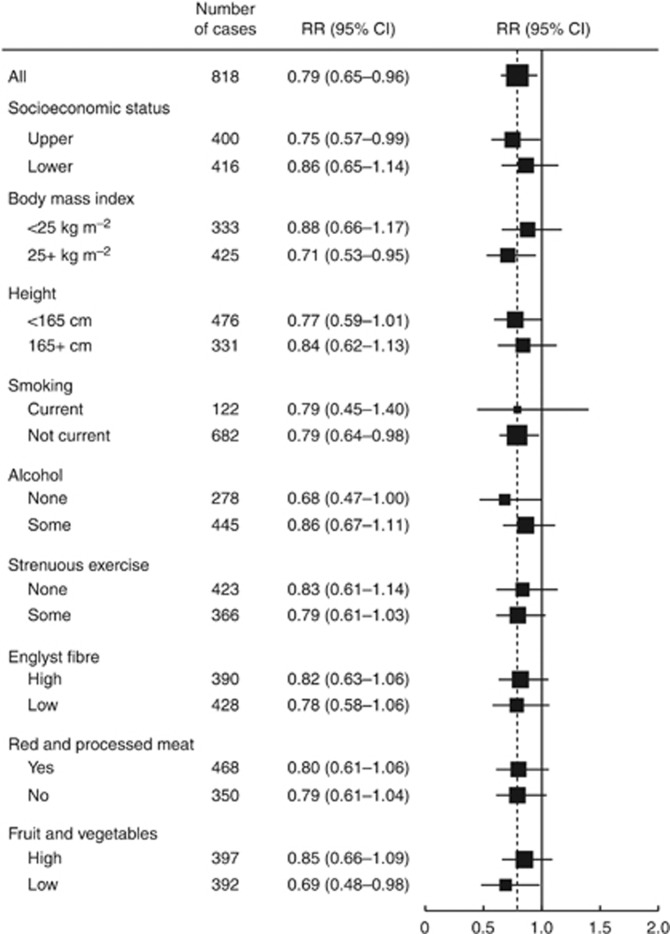

We also examined the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma by the reported frequency of organic food consumption at baseline (usually/always vs never) according to sub-groups of socioeconomic status, BMI, smoking status and other factors.

Results

In total, 623 080 women reported their frequency of consumption of organic food at baseline, had not been diagnosed with any cancer (other than non-melanoma skin cancer) before baseline, and had not changed their diet because of illness in the last 5 years. At baseline, 30% (n=187 451) of women reported never eating organic food, 63% (n=390 040) reported sometimes eating organic food, and 7% (n=45 589) reported usually or always eating organic food. Table 1 shows characteristics of these women and information about follow-up. After a mean follow-up time of 9.3 (s.d. 2.2) years, 53 769 incident cancers occurred.

Table 1. Characteristics of 623 080 The Million Women Study participants who provided details on the frequency of consumption of organic food and who did not change their diet in the last 5 years because of illness.

|

Frequency of consumption of organic food |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Never (n=187 451) | Sometimes (n=390 040) | Usually/always (n=45 589) | |

| Age, mean (s.d.), years | 59.3 (4.9) | 59.1 (4.9) | 59.7 (5.0) |

| Socioeconomic status, % (n) in upper third | 31 (58 014) | 37 (142 261) | 33 (15 235) |

| BMI, mean (s.d.), kg m−2 | 26.3 (4.5) | 25.8 (4.3) | 25.4 (4.3) |

| Height, mean (s.d.), cm | 161.9 (6.7) | 162.6 (6.6) | 162.8 (6.8) |

| Current smoker, % (n) | 16 (29 624) | 11 (40 311) | 11 (4703) |

| Alcohol consumption, mean (s.d.), gram per week | 42.0 (57.2) | 49.6 (59.6) | 49.8 (60.5) |

| Strenuous physical activity, % (n) > once weekly | 35 (64 051) | 46 (176 585) | 55 (24 288) |

| Parity, mean (s.d.) number of full-term pregnancies | 2.2 (1.2) | 2.0 (1.2) | 2.0 (1.2) |

| Fibre consumption, mean (s.d.), gram per day | 12.8 (4.7) | 14.4 (4.8) | 15.0 (5.4) |

| Consumers of red and processed meat, % (n) | 58 (108 182) | 52 (203 283) | 43 (19 570) |

|

Follow-up for cancer incidence | |||

| Number of incident cancers (total =53 769) | 16 520 | 33 307 | 3942 |

| Woman-years of follow-up (in 1000s) | 1743 | 3618 | 420 |

Abbreviation: BMI=body mass index.

Missing values not included in denominator for percentages. Values for socioeconomic status, height, parity, and strenuous physical activity are those reported in the recruitment survey. Values for age, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, fibre consumption, and red and processed meat consumption are those reported in the 3-year survey.

Women who reported usually or always consuming organic food were more likely to report that they participated in strenuous physical activity, and were less likely to smoke or eat red and processed meat than women who reported never consuming organic food. There were smaller differences in socioeconomic status and other characteristics by reported frequency of organic food consumption.

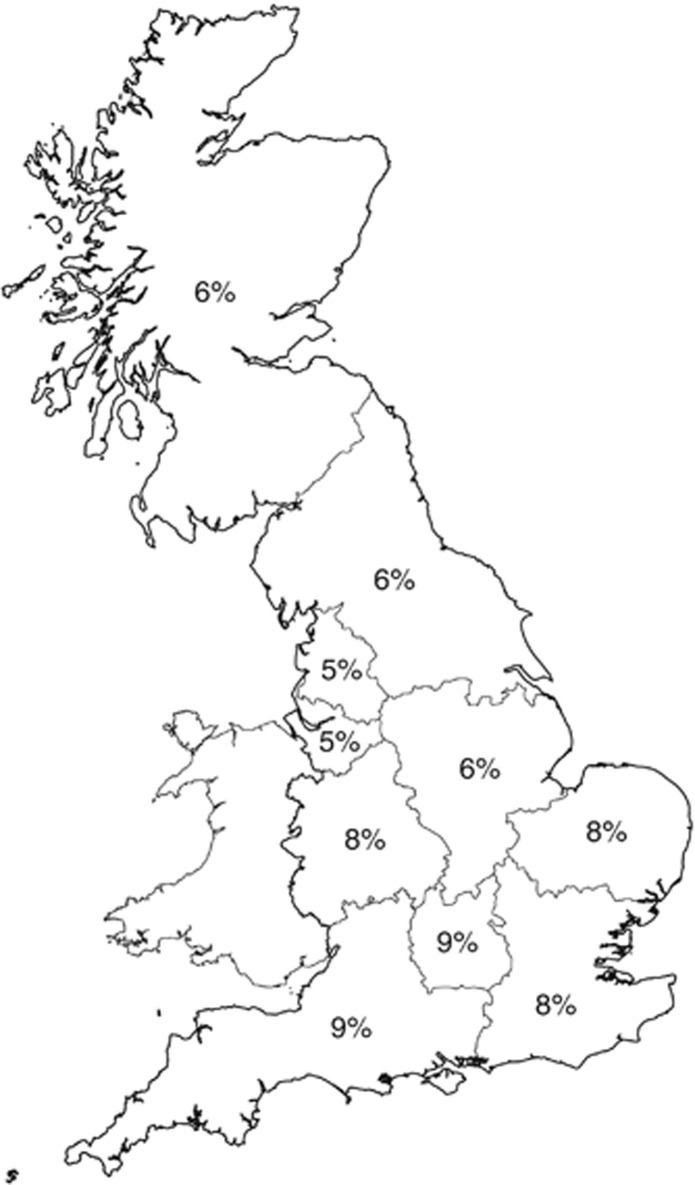

Figure 1 shows the percentage of women who reported usually or always consuming organic food at baseline by geographical region of breast screening centres. The percentage of women who reported usually or always consuming organic food was higher in the South and South West than in Scotland and the North of England, although these differences were moderate.

Figure 1.

Percentage of women who reported usually/always eating organic food, by region of recruitment (boundaries are approximate). Screening centres in Wales were not involved in this study. Base map OpenStreetMap.org contributors. Contains Ordnance Survey data Crown Copyright and database right 2014.

An average of 5 years after baseline, 64% of women again reported their consumption of organic food. Among women who reported usually or always consuming organic food at baseline only 3% reported never eating organic food 5 years later. Among those who reported never eating organic food at baseline, only 1% reported usually or always eating organic food 5 years later. Therefore, those reporting never or usually/always at baseline are distinct groups with little overlap between them 5 years later. We have focussed on the comparison between these groups.

Figure 2 shows the associations between reported consumption of organic food and risk of 16 individual cancers, listed in ICD order, stratified by age, region and socioeconomic status, and adjusted for smoking, BMI, physical activity, alcohol intake, height, parity, age at first birth, fibre intake, and type of meat intake. Compared with women who reported never eating organic food, there was a small increase in risk of breast cancer among women who reported usually or always eating organic food (RR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.02–1.15), but a decrease in risk for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (RR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.65–0.96). There were 213 cases of soft tissue sarcoma in total; compared with women who reported never eating organic food (n=65 cases), the RR of soft tissue sarcoma for women who reported usually or always eating organic food (n=21 cases) was 1.37 (95% CI: 0.82–2.27, P=0.2).

Figure 2.

Relative risk of cancer incidence for 16 individual cancer sites and total cancer by reported organic food consumption. Stratified by age, region, and deprivation, and adjusted for smoking, BMI, physical activity, alcohol intake, height, parity and age at first birth, fibre intake, and type of meat eaten. *g-s CI: group-specific confidence intervals.

When we further adjusted the breast cancer analysis for hormone replacement therapy use at baseline (never, past, current, and not known) the RRs and 95% g-s CIs were essentially unchanged: 1.00 (0.97–1.03), 1.06 (1.04–1.08), and 1.09 (1.03–1.15) for women who reported never, sometimes, or usually/always eating organic food, respectively.

In a sensitivity analysis excluding cancers diagnosed in the first 3 years of follow-up, there was still a significantly increased risk of breast cancer among women who reported usually or always eating organic food compared with women who reported never eating organic food (RR: 1.09, 95% CI: 1.01–1.17). For non-Hodgkin lymphoma in those who reported usually or always eating organic food, the reduced risk was still statistically significant (RR: 0.79, 95% CI: 0.64–0.99).

We also examined the risk of all cancer in women who reported usually or always consuming organic food at baseline and at the 8-year survey (n=53 479) compared with women who reported never consuming organic food at both surveys (n=17 624). Among these women, during an average of 5.2 years of follow-up after the 8-year survey, 3846 incident cases of cancers occurred. The RR for all cancer for women who reported usually/always consuming organic food at both surveys was 1.00 (95% CI: 0.92–1.09) compared with women who reported never consuming organic food at both surveys.

Figure 3 shows the relative risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in women who reported usually or always consuming organic food compared with never consuming organic food within various sub-groups of women, for example, upper socioeconomic status and lower socioeconomic status, and smokers and non-smokers. The associations were similar across all sub-groups examined.

Figure 3.

Relative risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma for usually or always vs never consumers of organic food by sub-groups of characteristics. Stratified by age, region, deprivation, and adjusted for smoking, BMI, physical activity, alcohol intake, height, parity and age at first birth, fibre intake (except for analysis stratified by fruit and vegetable consumption), and type of meat eaten.

Discussion

In this large prospective study of middle-aged women in the United Kingdom followed for 9.3 years with just over 50 000 incident cancers, we found little evidence for a decrease in the incidence of all cancers associated with usually or always consuming organic food, except perhaps for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

A systematic review comparing organic foods to conventional produce found that organic produce had a 30% lower risk for contamination with any detectable pesticide residue (Smith-Spangler et al, 2012). In terms of health-related outcomes, the systematic review found that small cross-sectional (n=49) (Curl et al, 2003) and cross-over (n=23) (Lu et al, 2006) studies in children have shown significantly lower levels of organophosphate pesticide metabolites among children on organic diets compared with conventional diets. However, the review found no studies that have compared pesticide exposure among consumers of conventional compared with organic foods in adults.

Exposure to pesticides in the general population, excluding occupational and accidental exposure, is mainly via residues on food. Regular testing of the food supply in the United Kingdom is undertaken to monitor levels of chemical residues in foods. The concentration of pesticide residues found in foods is generally low. The latest available report from the Pesticide Residues Committee, for the quarter ending December 2012, shows that pesticide residues were detected in 30% of food samples tested, but were above the maximum permitted level in only 1% of the food samples (The Expert Committee on Pesticide Residues in Food, 2012). The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified some of the detected pesticides, such as DDT (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1991) and chlorothalonil (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1999), as possibly carcinogenic to humans. Owing to a lack of data, some of the other pesticides that were detected are not classifiable as to their carcinogenicity to humans (International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1991).

Some, but not all, epidemiological studies have shown a higher incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma with occupational exposure to certain pesticides (Baris and Zahm 2000; Bassig et al, 2012). These studies have been limited by small sample size and errors in obtaining accurate measurements of cumulative pesticide exposure. We found a 21% lower risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in women who reported usually or always eating organic food compared with women who reported never eating organic food. This lowered risk remained after excluding the first 3 years of follow-up. The analyses were adjusted for a range of personal characteristics of women, including dietary fibre and meat intake. In addition, the associations for non-Hodgkin lymphoma were similar within sub-groups of socioeconomic status, BMI, height, smoking, alcohol, exercise, fibre intake, red and processed meat intake, and fruit and vegetable intake. However, we performed multiple tests and therefore we cannot rule out chance as an explanation for this finding.

Epidemiological studies have reported higher risks of soft tissue sarcoma among farmers and forestry workers, and with exposure to herbicides and organochlorine compounds (Dich et al, 1997). Our results showed no significant association between organic food consumption and risk of soft tissue sarcoma. However, only 213 cases of soft tissue sarcoma accrued during follow-up and we had limited power to detect an association with organic food consumption.

Small studies conducted in the early 1990s suggested a link between pesticide exposure and increased risk of breast cancer (Falck et al, 1992; Wolff et al, 1993), although later studies have not confirmed this association (Ingber et al, 2013). Our findings do not support the hypothesis that breast cancer risk might be reduced with lower pesticide exposure as we observed a slightly higher risk of breast cancer in women who usually or always ate organic food compared with women who never ate organic food. Women who reported consuming organic food were of a higher socioeconomic status, consumed more alcohol, and on average had slightly lower parity than women who never ate organic food, and these factors are associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. Although we adjusted for nine potential confounding factors including alcohol and socioeconomic status, the relative risk of 1.09 could well be because of residual confounding. It is also possible that women who reported frequently consuming organic food are more likely to attend breast cancer screening and therefore are more likely to be diagnosed with screen-detected breast cancer, which could account for the slightly higher risk of breast cancer in those that reported usually or always consuming organic food.

Reporting of consumption of organic food at baseline remained reasonably stable 5 years later. Never and usually/always were distinct groups at baseline with little overlap between them 5 years later. However, we do not have any information on how long women in our study had been consuming organic food before baseline. Consumption of organic food was related to various factors including geographical region, with a slightly higher proportion of women in the South and South West of England reporting usually or always eating organic food compared with women in the North of England and Scotland. Consumption of organic food was also related to certain individual characteristics including smoking, exercise, and red and processed meat consumption. However, all analyses were adjusted for these potential confounders.

This is a very large study with virtually complete follow-up and with detailed information on potentially important confounders including smoking, deprivation, reproductive and hormonal factors, body size, dietary factors, and other health indicators. Approximately two-thirds of women in The Million Women Study responded to the 3-year survey and answered the question on organic food. The main differences between responders and non-responders to the 3-year survey were the proportion of current smokers at recruitment (16% vs 28%) and the proportion of women in the upper third of socioeconomic status at recruitment (36% vs 29%). This would, however, not affect the comparisons here, especially as we adjust for smoking and socioeconomic status. A limitation of this study is that the frequency of organic food consumption was self-reported. However, there is likely to be a true difference in organic food consumption in the extreme frequency categories, that is, between those that reported never consuming organic food, and those that reported usually or always consuming organic food, and it is the comparison between these two groups that we have focussed on. In addition, we do not have information on the types of organic food eaten, such as fruits and vegetables, dairy products, or meat. UK sales data indicate that dairy and chilled convenience products account for 31% of the organic food market, and fruit and vegetables account for 23% of the organic market (Soil Association, 2013). A systematic review on organic food found that organic fruit and vegetables are less likely to contain detectable pesticide residues (Smith-Spangler et al, 2012); however, we did not test blood or tissue samples from our participants to confirm that women who reported usually or always consuming organic food had lower exposure to pesticides than those who reported never consuming organic food.

As far as we are aware, this is the first cohort study to examine the association between the consumption of organic food and the risk of cancer, and is particularly relevant given that health concerns have been identified as the primary motivation for consumers' purchase of organic food (Hughner et al, 2007). In summary, we did not find a reduced risk of cancer overall, or for 16 specific cancer sites or types among women who usually or always consume organic food. However, we did find a reduced risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Replication of this result is needed but future prospective studies would need to be extremely large and to follow participants for long periods (e.g., a cohort of 500 000 people followed for a decade) to have sufficient power to examine the association between organic food consumption and non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood markers of pesticide exposure could also be examined in relation to reported organic food consumption and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Acknowledgments

We thank the women who participated in The Million Women Study. We would like to thank Andrew Chadwick for generating Figure 1. The Million Women Study is supported by Cancer Research UK and the UK Medical Research Council. The funders did not influence the conduct of the study, the preparation of this report, or the decision to publish. The authors had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

This work is published under the standard license to publish agreement. After 12 months the work will become freely available and the license terms will switch to a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported License.

Contributor Information

The Million Women Study Collaborators:

Emily Banks, Valerie Beral, Ruth English, Jane Green, Julietta Patnick, Richard Peto, Gillian Reeves, Martin Vessey, Matthew Wallis, Hayley Abbiss, Simon Abbott, Miranda Armstrong, Angela Balkwill, Emily Banks, Vicky Benson, Valerie Beral, Judith Black, Kathryn Bradbury, Anna Brown, Benjamin Cairns, Karen Canfell, Dexter Canoy, Barbara Crossley, Francesca Crowe, Dave Ewart, Sarah Ewart, Lee Fletcher, Sarah Floud, Toral Gathani, Laura Gerrard, Adrian Goodill, Jane Green, Lynden Guiver, Isobel Lingard, Sau Wan Kan, Oksana Kirichek, Mary Kroll, Nicky Langston, Bette Liu, Maria-Jose Luque, Kath Moser, Lynn Pank, Kirstin Pirie, Gillian Reeves, Keith Shaw, Emma Sherman, Evie Sherry-Starmer, Helena Strange, Sian Sweetland, Alison Timadjer, Sarah Tipper, Ruth Travis, Lucy Wright, Owen Yang, and Heather Young

References

- Baris D, Zahm SH (2000) Epidemiology of lymphomas. Curr Opin Oncol 12: 383–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassig B, Lan Q, Rothman N, Zhang Y, Zheng T (2012) Current understanding of lifestyle and environmental factors and risk of non-hodgkin lymphoma: an epidemiological update. J Can Epidemiol 2012: 97830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Million Women Study Collaborative Group (1999) The Million Women Study: Design and characteristics of the study population. Breast Cancer Res 1: 73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curl C, Fenske R, Elgethun K (2003) Organophosphorus pesticide exposure of urban and suburban preschool children with organic and conventional diets. Environ Health Perspect 111: 377–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dangour AD, Dodhia SK, Hayter A, Allen E, Lock K, Uauy R (2009) Nutritional quality of organic foods: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 680–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defra (2013) Organic systems and standards in farming. Available from https://www.gov.uk/organic-systems-and-standards-in-farming (accessed 10 February 2014).

- Defra (2012) Organic Statistics 2011 United Kingdom. Available from https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-environment-food-rural-affairs/series/organic-farming (accessed 19 August 2013).

- Dich J, Zahm SH, Hanberg A, Adami HO (1997) Pesticides and cancer. Cancer Cause Control 8: 420–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easton DF, Peto J, Babiker AG (1991) Floating absolute risk: an alternative to relative risk in survival and case-control analysis avoiding an arbitrary reference group. Stat Med 10: 1025–1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falck Jr F, Ricci Jr A, Wolff MS, Godbold J, Deckers P (1992) Pesticides and polychlorinated biphenyl residues in human breast lipids and their relation to breast cancer. Arch Environ Health 47: 143–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughner R, McDonagh P, Prothero A, Shultz II C, Stanton J (2007) Who are organic food consumers? A complilation and review of why people purchase organic food. J Consum Behav 6: 94–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ingber SZ, Buser MC, Pohl HR, Abadin HG, Edward Murray H, Scinicariello F (2013) DDT/DDE and breast cancer: A meta-analysis. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 67: 421–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (1991) Occupational exposures in insecticide application and some pesticides. IARC Monograph on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans, Vol 53: pp 5–586. IARC Monograph: Lyon, France. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (1999) Some Chemicals that Cause Tumours of the Kidney or Urinary Bladder in Rodents and Some Other Substances,. Vol 73: pp 9–641. IARC Monographs: Lyon, France. [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Toepel K, Irish R, Fenske R, Barr D, Bravo R (2006) Organic diets significantly lower children's dietary exposure to organophosphorus pesticides. Environ Health Perspect 114: 260–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafalou S, Abdollahi M (2013) Pesticides and human chronic diseases: evidences, mechanisms, and perspectives. Toxicol Appl Pharm 268: 157–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Spangler C, Brandeau M, Hunter G, Bavinger J, Pearson M, Eschbach P, Sundaram V, Liu H, Schirmer P, Stave C, Olkin I, Bravata DM (2012) Are organic foods safer or healthier than conventional alternatives?: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med 157: 1539–3704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soil Association (2004) Organic market report 2004. Available from http://www.soilassociation.org/marketreport (accessed 24 September 2012).

- Soil Association (2009) Organic market report 2009. Available from http://www.soilassociation.org/marketreport (accessed 24 September 2012).

- Soil Association (2012) Organic market report 2012. Available from http://www.soilassociation.org/marketreport (accessed 19 August 2013).

- Soil Association (2013) Organic market report 2013. Available from http://www.soilassociation.org/marketreport (accessed 7 February 2014).

- The Expert Committee on Pesticide Residues in Food (2012) Report on the Pesticide Residues Monitoring Programme for Quarter 4 2011. Available from http://www.pesticides.gov.uk/Resources/CRD/PRiF/Documents/Results%20and%20Reports/2012/Q4%202012%20Final.pdf (accessed 19 August 2013).

- Townsend P, Phillimore P, Beattie A (1988) Health and Deprivation: Inequality and the North. Croom Helm: London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff MS, Toniolo PG, Lee EW, Rivera M, Dubin N (1993) Blood levels of organochlorine residues and risk of breast cancer. JNCI 85: 648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]