Abstract

Adult cardiac valve endothelial cells (VEC) undergo endothelial to mesenchymal transformation (EndMT) in response to transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ). EndMT has been proposed as a mechanism to replenish interstitial cells that reside within the leaflets and further, as an adaptive response that increases the size of mitral valve leaflets after myocardial infarction. To better understand valvular EndMT, we investigated TGFβ-induced signaling in mitral VEC, and carotid artery endothelial cells (CAEC) as a control. Expression of EndMT target genes α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), Snai1, Slug, and MMP-2 were used to monitor EndMT. We show that TGFβ-induced EndMT increases phosphorylation of ERK (p-ERK), and this is blocked by Losartan, an FDA-approved antagonist of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1), that is known to indirectly inhibit phosphorylation of ERK (p-ERK). Blocking TGF-β-induced p-ERK directly with the MEK1/2 inhibitor RDEA119 was sufficient to prevent EndMT. In mitral VECs, TGFβ had only modest effects on phosphorylation of the canonical TGF-β signaling mediator mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (SMAD3). These results indicate a predominance of the non-canonical p-ERK pathway in TGFβ-mediated EndMT in mitral VECs. AT1 and angiotensin II type 2 (AT2) were detected in mitral VEC, and high concentrations of angiotensin II (AngII) stimulated EndMT, which was blocked by Losartan. The ability of Losartan or MEK1/2 inhibitors to block EndMT suggests these drugs may be useful in manipulating EndMT to prevent excessive growth and fibrosis that occurs in the leaflets after myocardial infarction.

Keywords: mitral valve, endothelial cells, endothelial to mesenchymal transformation, TGFβ, ERK, Losartan

Introduction

EndMT is an essential step in cardiac valve formation during embryogenesis. A subset of endothelial cells lining the endocardial cushions in arterioventricular canal and outflow tract disengage from their neighbors, increase expression of α-SMA, migrate into the interstitial region between the endocardium and myocardium, and synthesize valve-specific extracellular matrix. TGFβ is one important mediator of this orchestrated process[1]. Of note, EndMT is a relatively new term in the literature that refers specifically to endothelial-to-mesenchymal transformation[2], as opposed to EMT, which encompasses all types of epithelial to mesenchymal transformation.

In post-natal adult valves, endothelial cells that appear to be undergoing EndMT are seen in focal regions [3,4]. In vitro studies of aortic, pulmonary and mitral valve endothelial cells (VEC) demonstrated that ovine and human adult VEC undergo hallmarks of EndMT when treated with TGFβ1, 2 or 3 (ovine VECs) or TGFβ2 (human VECs) [3,4,5]. The potential relevance of post-natal EndMT was revealed in an experimental ovine model designed mimic mechanical forces imposed on the leaflets after myocardial infarction. A mechanical stretch imposed over 2 months on mitral valve leaflets significantly increased EndMT, coincident with increased size of the leaflets in vivo[5]. This lead us to propose that EndMT is part of an adaptive mechanism to increase leaflet size and thereby prevent or minimize mitral regurgitation after myocardial infarction.

TGF-β-stimulated EndMT has been examined in many types of cultured endothelial cells. Ghosh and colleagues showed signaling through the canonical SMAD pathway in murine cardiac endothelial cells with little involvement of the non-canonical ERK pathway [6]. SMAD signaling was also shown to be operative in a murine MS-1 endothelial cell line[7]. Several pathways - SMAD, MEK, PI3K, and p38 – were stimulated by TGFβ2 and shown to be required for EndMT in human skin endothelial cells[8]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells, TGFβ increased microRNA-21 and EndMT through an AKT-dependent mechanism[9]. This array of signaling pathways suggests that perhaps the endothelial cell type and the environmental context influence the signaling pathways used to initiate EndMT.

We focus on EndMT in mitral VEC as part of an on-going effort to understand how the mitral valve endothelium responds over time to the myriad of changes that occur in the heart after myocardial infarction. We were intrigued by the elegant studies by Dietz and colleagues[10,11,12] which showed a critical role for non-canonical TGFβ signaling in aortic aneurym formation in a murine model of Marfan syndrome. Excessive TGFβ signaling in this model could be blocked by Losartan, a selective inhibitor of angiogensin II receptor-1 (AT1). By inhibiting AT1, Losartan shunts AngII signaling to AT2, which in turn provides a robust block on the phosphorylation of ERK. Indeed, Habashi and coauthors showed that AT2-mediated antagonism of ERK activity is required for Losartan to prevent aortic aneurysms in Marfan mice[11]. Thus, Losartan inhibits non-canonical TGFβ signaling by an indirect inhibition of ERK activation.

Materials and methods

Mitral valve endothelial cells (VEC)

Clonal VEC populations from mitral valve leaflets from sheep were prepared as described[13] and expanded on 1% gelatin-coated dishes in endothelial basal medium-2 (EBM-2 (Lonza, cat # 3156), 10 % heat-inactivated FBS (Hyclone), 1X glutamine/penicillin/streptomycin (Life Technologies, Inc) and 2 ng/ml basic FGF (Roche Applied Science). This medium is referred to as EBM-B. Experiments were performed with mitral VEC clone C4 at passages 10 and 11, mitral VEC clone C5 at passages 9–12 and mitral VEC clone E10 at passages 11 and 12.

Non-valvular EC

Ovine carotid artery EC (CAEC), isolated as described [13], and endothelial colony forming cells (EFCF), isolated from ovine peripheral blood as described [14] served as a non-valvular endothelial controls. CAEC and ECFC were cultured under identical conditions as the mitral VECs for all experiments.

Inhibitors

Losartan (Cayman Chemical), dissolved in DMSO at 11.8mM, was tested at 1–50um. RDEA119, an inhibitor of MEK[15] provided by Dr. Craig J. Thomas, NIH Chemical Genomics Center, NHGRI, National Institutes of Health, was dissolved in DMSO at 10mM and tested at 5–100 uM. SB-431542 hydrate (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in DMSO at 26mM. Inhibitors were stored in aliquots at −80C.

EndMT assay

Ovine mitral VEC and CAEC were plated at 10,000 cells/cm2 on 1% gelatin-coated dishes in EBM-B. 24 hours after plating, fresh EBM-B containing 1ng/ml human recombinant TGFβ1 (R&D Systems, Inc) was added. Inhibitors were added 30 minutes before adding TGFβ1. Four days later cells were harvested for Western blots or for isolation of mRNA for reverse transcriptase-quantitative PCR (qPCR).

Western Blots

Cells were lysed, fractionated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to 0.45 PVDF membranes as described [13]. Blots were probed with goat anti-human CD31 (1:300) (M-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), goat anti-human VE-cadherin (1:300) (C-19, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, murine anti-human α-SMA (1:2000) (Sigma, mAb clone 1A4) and anti-tubulin (Sigma). Two different anti-p-ERK antibodies were used. The first was a murine mAb anti-phospho-44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) and the second was a rabbit polyclonal anti-phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204). Total ERK was detected using anti-p44/42 MAPK (ERK) mAb. Anti-phosphorylated-SMAD3 (p-SMAD3) (Ser423/425(clone C25A9) and anti-SMAD2/3 (3102), and all ERK pathway antibodies, were from Cell Signaling Technology. All antibodies were shown to cross-react with their ovine homologs. Band intensities on the western blots were quantified using Image Studio Lite software (LI-COR).

RNA extraction and Qpcr

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), 1µg was treated with DNAse I (Life Technologies). Reverse transcription was performed with Superscript III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Life Technologies). qPCR was performed with Kapa Sybr Fast ABI Prism 2X qPCR Master Mix (Kapa Biosystems) in triplicate using StepOne Plus 96 well Real Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Results were normalized to ribosomal protein S9 amplified in the same experimental run. All PCR products were sequenced using ABI DNA sequencer (Dana Farber/Harvard Cancer Center DNA Resource Core) to verify the sequence corresponded to the gene of interest. Oligonucleotide primer sequences are shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Results

TGFβ1 induces rapid phosphorylation of ERK in mitral VEC

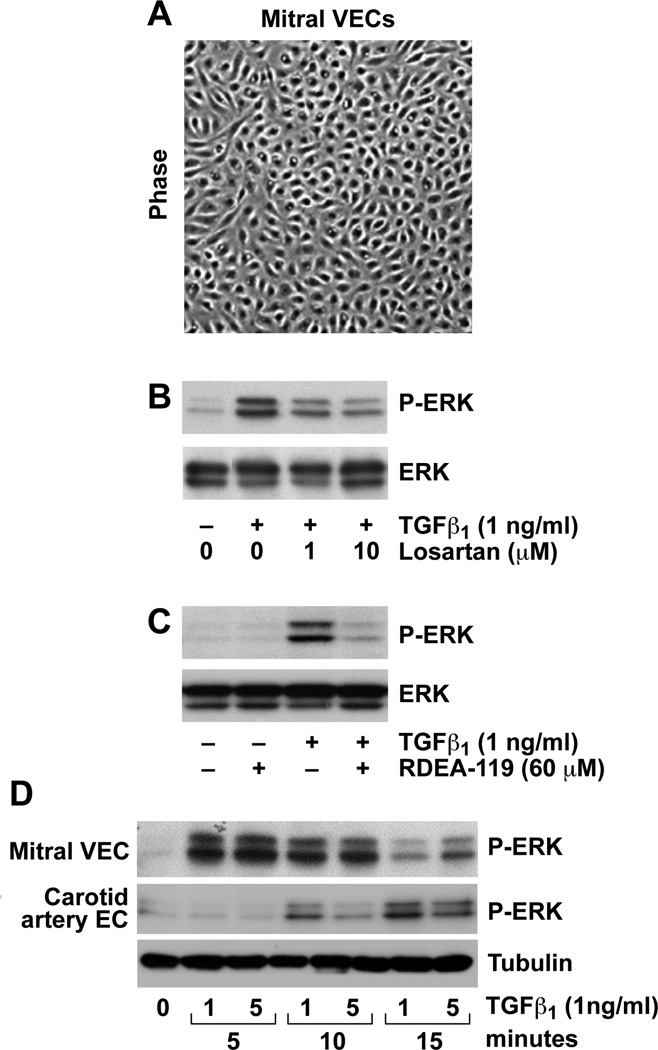

Ovine mitral VEC clones exhibit cobblestone morphology (Figure 1A), and express an endothelial phenotype [13]. Mitral VEC treated with TGFβ1 for 5 minutes showed robust p-ERK, which was inhibited when the cells were pre-incubated with the AT1 receptor antagonist Losartan (Figure 1B). The phosphorylation of ERK by TGFβ1 treatment was, as expected, blocked by the MEK1/2 inhibitor RDEA119 (Figure 1B). TGFβ1-induced p-ERK occurred within 5 minutes and was diminished by 15 minutes, while the onset of TGFβ-induced p-ERK in CAEC required 10 minutes, with increased p-ERK seen at 15 minutes (Figure 1D). Thus, TGFβ-induced activation of the non-canonical ERK pathway occurred rapidly in mitral VEC. Controls in which cells were moved out of the incubator, PBS added instead of TGFβ1, and the cells returned to the incubator for 5, 10 and 15 minutes verified that the rapid phosphorylation of ERK was not due to movement of the cells between the incubator and cell culture hood (data not shown).

FIGURE 1. TGFβ1 induced phosphorylation of ERK in mitral VEC.

A, Phase contrast image of ovine mitral VEC grown in EBM-B. B, Western blot of P-ERK and ERK in mitral VEC pre-treated for 30 minutes with 0, 1 or 10 uM Losartan, as indicated, before addition of 1ng/ml TGFβ1 for 5 minutes. C, Western blot of P-ERK and ERK in mitral VEC pretreated for 30 minutes with 60uM RDEA-119 before addition of TGFβ1 for 5 minutes. D, Time course of phosphorylation of ERK in mitral VEC and carotid artery EC (CAEC) treated with 1 or 5 ng/ml TGFβ1. Tubulin, loading control.

Blocking TGFβ1-induced phosphorylation of ERK inhibits EndMT in mitral VEC

Mitral VECs were shown previously to undergo TGFβ1-mediated EndMT [5,13]. To determine whether EndMT relies on the non-canonical ERK signaling pathway, we tested the effect of Losartan and the MEK1/2 inhibitor RDEA-119 on TGFβ1-induced EndMT. Because a small number of contaminating fibroblasts in a primary culture of endothelial cells could contribute to the apparent increase in α-SMA in TGFβ-treated cultures, we used clonal populations of mitral VECs to insure that EndMT, and not fibroblast to myofibroblast activation, was assessed. Each experiment was conducted, and results confirmed, with three different ovine mitral VEC clones – C4, C5 and E10. A time course experiment showed that α-SMA expression, a marker of EndMT, was first detected in mitral VECs after 3 days of culture in TGFβ1, with maximal expression after 4 days (data not shown). This is the basis for analyzing EndMT after 4 days.

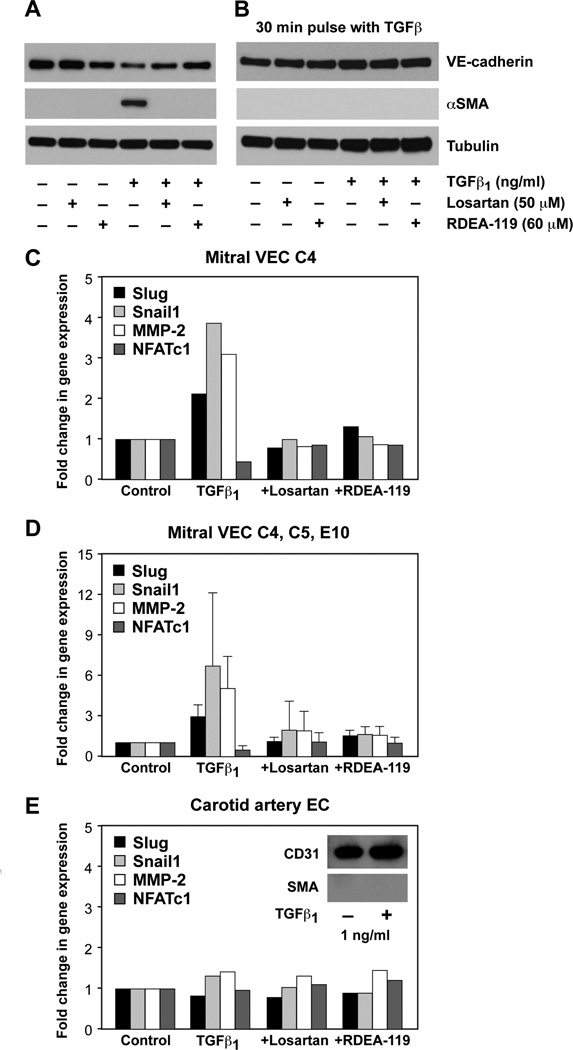

Mitral VECs were treated without or with TGFβ1 for 4 days in the presence or absence of Losartan or RDEA119. TGFβ1 strongly induced expression of α-SMA protein and caused a small decrease in VE-cadherin, both of which were blocked by inclusion of either Losartan or RDEA-119 over the 4 days (Figure 2A). The rapid phosphorylation of ERK in mitral VEC seen in Figure 1 prompted us to ask whether a short burst of TGFβ signaling would be sufficient to induce EndMT. Mitral VEC were pulsed with 1ng/ml TGFβ1 for 30 minutes, TGFβ1 was removed, and cells were cultured for 4 days in EBM-B. αSMA was not induced (Figure 2B), which indicates that a 30 minute pulse of TGFβ1 signaling is not sufficient to induce EndMT.

FIGURE 2. Losartan and the MEK1/2 inhibitor RDEA-119 inhibit TGFβ1-induced EndMT in mitral VEC.

A, Western blot of VE-cadherin, α-SMA and tubulin in mitral VEC treated ± TGFβ1 for 4 days without or with Losartan, without or with RDEA-119 as indicated. B, Mitral VEC as in A, but treated with TGFβ1 for 30 minutes. After 30 minutes, VEC were washed with PBS, and cultured for 4 days in EBM-B. C, Mitral VEC clone 4 (C4) treated as described in A. Untreated cells (Control), cells treated with TGFβ1 for 4 days (TGFβ1), cells treated with TGFβ1 + Losartan (+Losartan) and cells treated with TGFβ1 + RDEA-119 (+RDEA-119) were analyzed by qPCR for EndMT markers Slug (black bars), Snail1 (light grey bars), MMP-2 (white bars) and NFATc1 (dark grey bars). Ribosomal protein S9 was analyzed in parallel as a house keeping gene and used for normalization. D, qPCR data compiled from experiment in A for mitral valve clones C4, C5 and E10. E, CAEC treated as in A, analyzed by qPCR. Inset shows western blot for CD31 (endothelial marker) and αSMA (EndMT marker) in CAEC treated ± TGFβ1 for 4 days.

We assessed additional markers of EndMT – the transcription factors Slug, Snai1 and NFATc1 and the matrix metalloproteinase MMP-2 - by qPCR in mitral VEC clones and CAEC treated for TGFβ1 for 4 days in the presence or absence of inhibitors. qPCR was performed instead of western blot because of a lack of commercially available anti-ovine antibodies for these proteins. Slug, Snai1 and MMP-2 were increased when mitral VEC C4 were treated with TGFβ1 for 4 days but not when cells were also treated with Losartan or RDEA-119 (Figure 2C). NFATc1 is a transcription factor expressed in the endocardial cushions that has been shown to mark endothelial cells that do not undergo EndMT and instead proliferate [16,17]; this indicates that NFATc1 is inversely correlated with EndMT. Indeed, NFATc1 levels were reduced in mitral VEC C4 treated with TGFβ1, but not when the cells were treated with TGFβ1 plus Losartan or plus RDEA-119. The same trends in induction of EndMT markers and suppression of NFATc1 can be appreciated when three experiments on three different mitral VEC clones (E10, C5 and C4) were compiled into one graph (Figure 2D). In contrast, mRNA levels of Slug, Snai1, MMP-2 and NFATc1 were not modulated in non-valvular CAEC treated for 4 days under identical conditions (Figure 2E). The inset verifies that αSMA was not induced in CAEC treated with TGFβ1 for 4 days. These results demonstrate that Losartan, which effectively blocks TGFβ1-mediated p-ERK, blocked EndMT. RDEA-119, a specific inhibitor of MEK1/2, which directly phosphorylates ERK, blocked EndMT as well. Thus, the non-canonical TGFβ signaling pathway plays a critical role in initiating EndMT in mitral VEC.

TGFβ1-induced phosphorylation of ERK and SMAD3 in mitral VEC over four days

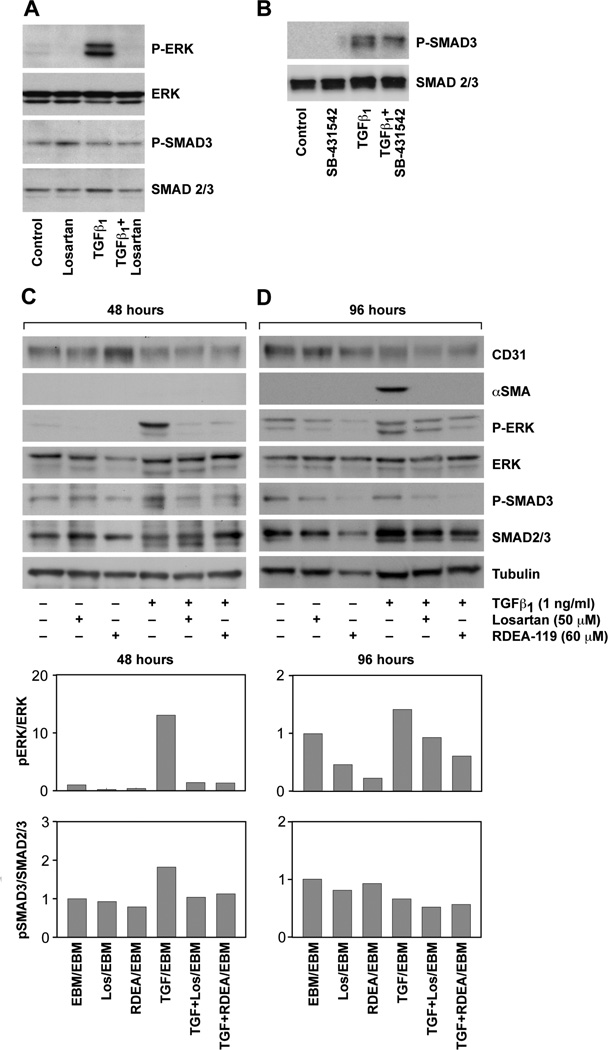

Additional experiments were performed to analyze TGFβ-induced phosphorylation SMAD3 – the canonical pathway – in mitral VEC treated with or without TGFβ1 for 15 minutes, with or without Losartan. Consistent with Figure 1, Losartan blocked the TGFβ1-mediated increase in p-ERK but levels of p-SMAD3 were not modulated by TGFβ1 or by the inhibitors (Figure 3A). CAEC were analyzed in parallel to provide a positive control for the phosphorylation of SMAD3 and the effectiveness of the anti-p-SMAD3 mAb (Figure 3B). The TGFβR signaling inhibitor SB431542 decreased the level of p-SMAD3 in CAEC.

FIGURE 3. P-ERK and P-SMAD3 in mitral VEC.

A, Western blot of P-ERK, ERK, P-SMAD3 and SMAD2/3 in mitral VEC C5 pretreated ± 50 uM Losartan for 30 minutes and treated ± 1ng/ml TGFβ1 for 15 minutes, as indicated. B, Western blot of p-SMAD3 and SMAD2/3 in CAEC pretreated for 30 minutes ± 10uM SB-431542 and treated ± 1ng/ml TGFβ1 for 15 minutes, as indicated. C and D, Western blots of mitral VEC clone E10 treated for 48 hours (C) or 96 hours (D) ± TGFβ1, ± Losartan, ± RDEA-119 as indicated. Tubulin, loading control. Band intensities were quantified using Image Studio Lite software (LI-COR). The P-ERK/ERK and P-SMAD3/SMAD2/3 levels and ratios in untreated (control) mitral VEC were set to 1.0.

We assessed the phosphorylation status of ERK and SMAD3 in mitral VEC treated with TGFβ1 over a 4 day time course, in the presence or absence of Losartan or RDEA119, to determine the extent to which one or both pathways was active during EndMT. Cell lysates were prepared at 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours. The western blots and quantifications were similar for 24 and 48 hour time points, and for the 72 and 96 hour time points. Therefore we show the 48 and 96 hour time points only in Figure 3C and D. p-ERK was strongly increased by TGFβ at 48 hours and modestly increased at 96 hours. Losartan and RDEA119 reduced TGFβ-induced p-ERK at 48 and 96 hours and reduced basal levels of p-ERK at 96 hours. Levels of p-SMAD3 were increased less than two-fold by TGFβ1 at 48 hours and not at all at 96 hours. The fold increase was less than 2-fold at 24 hours and there was no increase at 72 hours (data not shown). In summary, analysis of p-ERK and p-SMAD3 levels over 4 days in response to TGFβ revealed a marked increase in p-ERK at 24 and 48 hours, which was inhibited by Losartan or RDEA119. The drugs continued to reduce levels of p-ERK at 96 hours. Mitral VEC treated with TGFβ1 showed induction of αSMA at 96 hours (Figure 3D), as expected. These results indicate that TGFβ induced signaling through the non-canonical ERK pathway is ongoing and required for EndMT in this in vitro model.

Angiotensin II receptors in mitral VEC

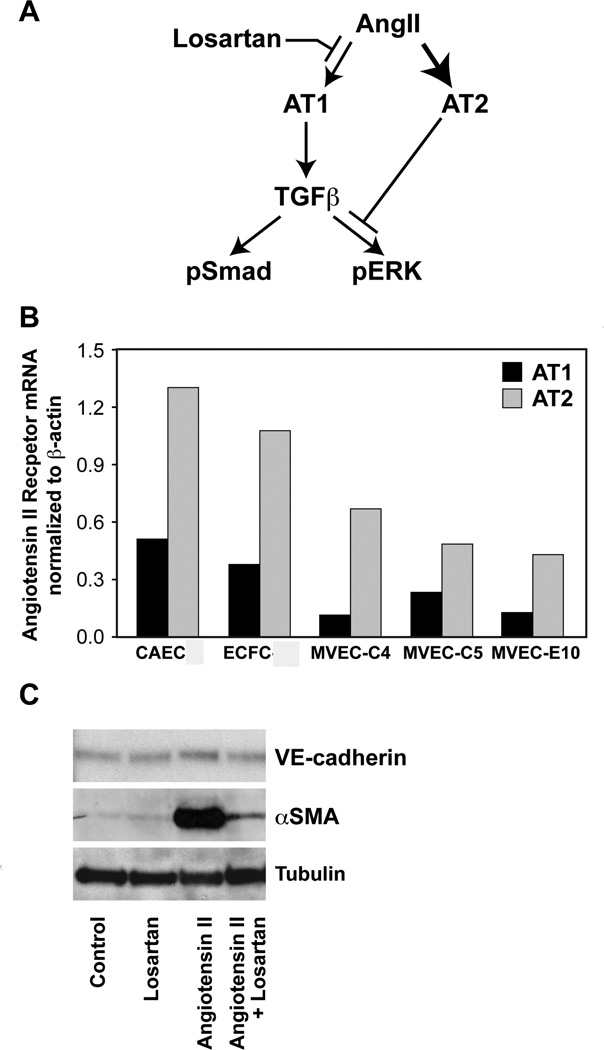

Our finding that Losartan inhibited TGFβ1-mediated EndMT indicated that the ovine mitral VEC should express AT1 and AT2 receptors. Habashi and colleagues showed Losartan inhibition of AT1 in Marfan syndrome mice enhances signaling through AT2. Further, they showed that AT2 receptor-mediated inhibition of p-ERK is required for the beneficial effect of Losartan in preventing aortic aneurysm in these mice[11]. The schematic in Figure 4A depicts the shift from AT1 to AT2 signaling in the presence of Losartan. AT1 and AT2 receptors were detected by qPCR in three mitral VEC clones, CAEC and ovine peripheral blood endothelial colony forming cells (ECFC) (Figure 4B). Since AngII signaling through AT1 is known to stimulate expression of TGFβ ligands and receptors, we tested the ability of angiotensisn II to induce EndMT in mitral VECs over 4 days. Angiotensin II induced strong expression of α-SMA at 50uM (Figure 4C), but had no effect at lower concentrations of 0.01–10 uM (not shown). Angiotensin II induced expression of α-SMA was effectively blocked by Losartan (Figure 4C). These results indicate the AT1 and AT2 receptors are functional in mitral VECs.

FIGURE 4. AT1 and AT2 receptors in mitral VEC.

A, Schematic showing Losartan effects on AT1 and AT2 receptor signaling and pERK. From “Angiotensin II Type 2 Receptor Signaling Attenuates Aortic Aneurysm in Mice Through ERK Antagonism” by Jennifer P. Habashi, Jefferson J. Doyle, Tammy M. Holm, Hamza Aziz, Florian Schoenhoff, Djahida Bedja, YiChun Chen, Alexandra N. Modiri, Daniel P. Judge, Harry C. Dietz, published in Science, 2011, vol. 332, issue 6027. Printed with permission from AAAS. B, Quantitative RT-PCR of AT1 (black bars) and AT2 (gray bars) mRNA in ovine CAEC, ECFC and three clones of mitral VEC, normalized to β-actin. C, Western blot for VE-cadherin, α-SMA and tubulin in mitral VEC clone E10 ± 50uM Losartan and ± angiotensin II (50uM) for 4 days. Tubulin, loading control.

Discussion

We show that EndMT in mitral VEC requires non-canonical TGFβ1 signaling via p-ERK. The canonical pathway, TGFβ-induced phosphorylation of SMAD3, was detected, but at modest levels in comparison to TGFβ-induced p-ERK. Losartan, an FDA-approved “ARB” (angiotensin receptor blocker) that dampens TGFβ signaling by indirect mechanisms (Figure 4A), blocked TGFβ1-induced EndMT in mitral VEC. Direct inhibition of p-ERK with the MEK1/2 inhibitor RDEA119 also blocked EndMT. These results demonstrate a critical role for the non-canonical TGFβ-induced EndMT in mitral VEC.

While SMAD-dependent TGFβ signaling has been studied extensively, roles for p-ERK in TGFβ signaling, specifically in the context of epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) and EndMT, have emerged slowly. A report in 2004 first revealed a role for p-ERK in TGFβ1-induced EMT in normal murine mammary gland epithelial cells[18]. In 2006, phosphorylation of ERK was shown to be required for EndMT in the atrioventricular cushions of developing murine embryos [19]. Several studies on TGFβ-induced EndMT in cultured cells were published in 2012 [6,7,8,9]. SMAD-dependent signaling was implicated in three of these studies, while one study indicated that multiple pathways including SMAD, ERK, PI3K and p38 MAPK were activated in EndMT in human endothelial microvascular endothelial cells[8].

We focus on EndMT in a specific cellular context –the mitral valve endothelium – and when and how VEC re-activate EndMT to adapt to changing hemodynamics and/or cytokines after myocardial infarction. In humans and in sheep, the mitral valve leaflets both lengthen and thicken over time after myocardial infarction due to displacement of the papillary muscles caused by remodeling in the left ventricular myocardium. The increase in leaflet size is initially beneficial as it can minimize mitral regurgitation, but over time fibrosis sets in, disrupting the mitral valve seal. We asked whether EndMT might occur as part of this adaptive response and found that EndMT was significantly increased in mitral valve endothelium in an ovine model in which mechanical stretch was imposed on the mitral valve leaflets for 2 months [5]. This study was the first to show evidence for EndMT in the mitral valve endothelium, associated with increased leaflet size, and suggested that active manipulation of EndMT may provide a therapeutic approach to boost or modulate compensatory mechanisms.

This in vivo finding prompted us to examine the effect of Losartan on EndMT in mitral VEC in vitro, to probe intracellular signaling pathways that might be involved in this process. Losartan is an FDA-approved “ARB” or angiotensin receptor blocker. It is used widely to treat hypertension and is also being tested in clinical trials for ability to prevent aortic aneurysms in patients with heritable disorders that result in too much TGFβ signaling in the aortic wall[20]. Losartan proved to be a potent inhibitor of EndMT in mitral VEC. Whether Losartan could be used strategically in vivo to modulate EndMT in the mitral valve will require in vivo studies.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

TGFβ1 induces rapid phosphorylation of ERK1/2 but not SMAD3 in mitral valve endothelial cells.

Losartan, a drug known to dampen TGFβ signaling, blocks phosphorylation of ERK1/2.

Losartan blocks EndMT in mitral valve endothelial cells.

TGFβ1-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2 is required for mitral valve EndMT.

Losartan may be useful for modulating excessive EndMT in mitral valve diseases.

Acknowledgements

We thank Juan Melero-Martin for providing the ovine CAEC and ECFC and Kristin Johnson for preparing the figures. This work was supported by the Fondation Leducq Transatlantic Network and R01 HL109506 (JB, RL).

The abbreviations used are

- VEC

valve endothelial cells

- EndMT

endothelial to mesenchymal transformation

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor-β

- CAEC

carotid artery endothelial cells

- α-SMA

α-smooth muscle actin

- AT1

angiotensin II type 1 receptor

- AT2

angiotensin II type 2 receptor

- SMAD

signaling mediator mothers against decapentaplegic homolog

- Ang II

angiotensin II

- EBM

endothelial basal medium

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Person AD, Klewer SE, Runyan RB. Cell biology of cardiac cushion development. Int Rev Cytol. 2005;243:287–335. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(05)43005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Meeteren LA, ten Dijke P. Regulation of endothelial cell plasticity by TGF-beta. Cell and Tissue Research. 2012;347:177–186. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paranya G, Vineberg S, Dvorin E, Kaushal S, Roth SJ, Rabkin E, Schoen FJ, Bischoff J. Aortic valve endothelial cells undergo transforming growth factor-beta-mediated and non-transforming growth factor-beta-mediated transdifferentiation in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2001;159:1335–1343. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62520-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paruchuri S, Yang JH, Aikawa E, Melero-Martin JM, Khan ZA, Loukogeorgakis S, Schoen FJ, Bischoff J. Human pulmonary valve progenitor cells exhibit endothelial/mesenchymal plasticity in response to vascular endothelial growth factor-A and transforming growth factor-beta2. Circ Res. 2006;99:861–869. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000245188.41002.2c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dal-Bianco JP, Aikawa E, Bischoff J, Guerrero JL, Handschumacher MD, Sullivan S, Johnson B, Titus JS, Iwamoto Y, Wylie-Sears J, Levine RA, Carpentier A. Active adaptation of the tethered mitral valve: insights into a compensatory mechanism for functional mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2009;120:334–342. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.846782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh AK, Nagpal V, Covington JW, Michaels MA, Vaughan DE. Molecular basis of cardiac endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EndMT): differential expression of microRNAs during EndMT. Cellular Signalling. 2012;24:1031–1036. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mihira H, Suzuki HI, Akatsu Y, Yoshimatsu Y, Igarashi T, Miyazono K, Watabe T. TGF-beta-induced mesenchymal transition of MS-1 endothelial cells requires Smaddependent cooperative activation of Rho signals and MRTF-A. Journal of Biochemistry. 2012;151:145–156. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvr121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Medici D, Potenta S, Kalluri R. Transforming growth factor-beta2 promotes Snail-mediated endothelial-mesenchymal transition through convergence of Smad-dependent and Smad-independent signalling. The Biochemical journal. 2011;437:515–520. doi: 10.1042/BJ20101500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumarswamy R, Volkmann I, Jazbutyte V, Dangwal S, Park DH, Thum T. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition is partly mediated by microRNA-21. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2012;32:361–369. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.234286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habashi JP, Judge DP, Holm TM, Cohn RD, Loeys BL, Cooper TK, Myers L, Klein EC, Liu G, Calvi C, Podowski M, Neptune ER, Halushka MK, Bedja D, Gabrielson K, Rifkin DB, Carta L, Ramirez F, Huso DL, Dietz HC. Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science. 2006;312:117–121. doi: 10.1126/science.1124287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habashi JP, Doyle JJ, Holm TM, Aziz H, Schoenhoff F, Bedja D, Chen Y, Modiri AN, Judge DP, Dietz HC. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm in mice through ERK antagonism. Science. 2011;332:361–365. doi: 10.1126/science.1192152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holm TM, Habashi JP, Doyle JJ, Bedja D, Chen Y, van Erp C, Lindsay ME, Kim D, Schoenhoff F, Cohn RD, Loeys BL, Thomas CJ, Patnaik S, Marugan JJ, Judge DP, Dietz HC. Noncanonical TGFbeta signaling contributes to aortic aneurysm progression in Marfan syndrome mice. Science. 2011;332:358–361. doi: 10.1126/science.1192149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wylie-Sears J, Aikawa E, Levine RA, Yang JH, Bischoff J. Mitral valve endothelial cells with osteogenic differentiation potential. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2011;31:598–607. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.216184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaushal S, Amiel GE, Guleserian KJ, Shapira OM, Perry T, Sutherland FW, Rabkin E, Moran AM, Schoen FJ, Atala A, Soker S, Bischoff J, Mayer JE., Jr Functional small-diameter neovessels created using endothelial progenitor cells expanded ex vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:1035–1040. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iverson C, Larson G, Lai C, Yeh LT, Dadson C, Weingarten P, Appleby T, Vo T, Maderna A, Vernier JM, Hamatake R, Miner JN, Quart B. RDEA119/BAY 869766: a potent, selective, allosteric inhibitor of MEK1/2 for the treatment of cancer. Cancer Research. 2009;69:6839–6847. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu B, Wang Y, Lui W, Langworthy M, Tompkins KL, Hatzopoulos AK, Baldwin HS, Zhou B. Nfatc1 coordinates valve endocardial cell lineage development required for heart valve formation. Circulation Research. 2011;109:183–192. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.245035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu B, Baldwin HS, Zhou B. Nfatc1 directs the endocardial progenitor cells to make heart valve primordium. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine. 2013;23:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie L, Law BK, Chytil AM, Brown KA, Aakre ME, Moses HL. Activation of the Erk pathway is required for TGF-beta1-induced EMT in vitro. Neoplasia. 2004;6:603–610. doi: 10.1593/neo.04241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivera-Feliciano J, Lee KH, Kong SW, Rajagopal S, Ma Q, Springer Z, Izumo S, Tabin CJ, Pu WT. Development of heart valves requires Gata4 expression in endothelial-derived cells. Development. 2006;133:3607–3618. doi: 10.1242/dev.02519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lindsay ME, Dietz HC. Lessons on the pathogenesis of aneurysm from heritable conditions. Nature. 2011;473:308–316. doi: 10.1038/nature10145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.