Abstract

Background:

Fragile fractures are most likely manifestations of fatigue damage that develop under repetitive loading conditions. Numerous microcracks disperse throughout the bone with the tensile and compressive loads. In this study, tensile and compressive load tests are performed on specimens of both the genders within 19 to 83 years of age and the failure strength is estimated.

Materials and Methods:

Fifty five human femur cortical samples are tested. They are divided into various age groups ranging from 19-83 years. Mechanical tests are performed on an Instron 3366 universal testing machine, according to American Society for Testing and Materials International (ASTM) standards.

Results:

The results show that stress induced in the bone tissue depends on age and gender. It is observed that both tensile and compression strengths reduces as age advances. Compressive strength is more than tensile strength in both the genders.

Conclusion:

The compression and tensile strength of human femur cortical bone is estimated for both male and female subjecting in the age group of 19-83 years. The fracture toughness increases till 35 years in male and 30 years in female and reduces there after. Mechanical properties of bone are age and gender dependent.

Keywords: Age, cortical femur bone, young's modulus, tensile strength, compressive strength

INTRODUCTION

Bone is a complex, highly organized and specialized connective tissue. According to Vashishth et al.[1] the skeletal strength and shape can be influenced by a variety of factors such as mechanical loading, genetics, pharmacological agents and nutritional intake. Bone tissues are connective tissues made up of cells including osteoblasts, osteocytes, bone-lining cells and osteoclasts which produce, maintain and organise the cellular matrix.[2] Skeletal fragility among the elderly is the most significant health problem associated with bone.[3] After middle age, the risk of fractures increases with age and fractures can occur in the absence of a traumatic load. Non-traumatic fractures are usually associated with osteoporosis.[4] For instance, fracture risk increases with age even when risk is adjusted for bone mass, indicating that bone tissue competence is compromised with age. Bone mineralisation and carbonate substitution increases with age, however, this does not decide the bone strength.[5] This may contribute to age-related skeletal fragility. The most important parameter deciding tissue quality in terms of its elastic properties is collagen organisation and its structure in the bone.[6]

Studies on the distribution of stresses and strains within the organic and mineral components may highlight the nano structural origin of damage in bone. When bone is subjected to axial tensile stresses, the organic matrix consisting of Type I collagen is subjected to both normal and shear stress that can cause nanoscale damage in the organic matrix of bone. The collagen fibrils transfer the tensile forces from one fibril to the next through shear stresses that are generated along the overlap region of the fibrils.[7,8] Deformation of collagen fibers involves molecular stretching and slippage, fibrillar slippage and ultimately defibrillation. These mechanisms decrease the fibril diameter and increase the toe region during subsequent tensile testing.[9]

Fracture due to compression in cortical bone depends strongly on the bone tissue volume fraction, the architecture and the mechanical properties of the bone tissue. As pointed out by Vikas Tomar[7] the cortical bone failures are sensitive to intra and inter specimen variations in architectural features as well as in material properties. Studies of the nano scale damage mechanism in connective tissues made of Type I collagen, have been conducted by mechanically loading these tissues and introducing damage in their ultrastructure.[10,11]

In this study, the analysis of mechanical behaviour of a human femur cortical bone is carried out. Tensile and compressive stresses are induced in cortical bone by repetitive loading. We test the hypothesis that bone failure strength depends on age and gender. Young's modulus for various age groups is calculated for both male and female. The elastic behaviour of bone tissue subjected to tensile load is demonstrated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Femur bones are thicker and longer than any of the human long bones. Hence, due to their dimension in cortical thickness femur bones are chosen as a source material. Bones are obtained from cadavers of both genders who were non hospitalised and are not immobilised before the death. Fifty five femoral samples are obtained and divided into various age groups ranging from 19 years to 83 years. After removal of the soft tissue, femoral bones are wrapped in gauge soaked in calcium buffered saline solution. During all cutting and machining operations, the bone material is frequently and liberally sprayed with saline solution to keep it cool and wet. Samples are tested with coded labelling to keep the patient information confidential.

The specimens are prepared with dimension 5 mm × 5 mm × 15 mm for tensile experimentation and 5 mm × 5 mm × 5mm cube for compression experiments. Experiments are conducted according to American Society for Testing and Materials International (ASTM) standards. Mechanical tests are performed on an Instron 3366 universal testing machine. The system is fitted with tensile grips and equipped with an extensometer for strain measurements.

Tensile test specimens are designed so that the highest strains will occur in the central portion or gauge region of the specimen. Strain measurements are obtained by attaching a clip on extensometer to the gauge section of the specimen. Stress is calculated as the applied force divided by the bone cross sectional area measured in the specimen midsection. Equal dimensions cubes are obtained for compression testing. The load facing the bone specimen is made to align with respect to the compression loading platen. The parallelism of the load containing surfaces of each specimen can be assessed by measuring the height differences between each of the four sides and a central point of the load contacting surfaces.

RESULTS

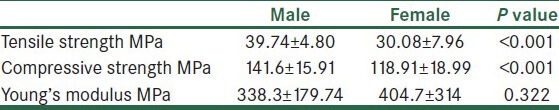

The tensile and compression load tests are performed on a human femur cortical bone and are analyzed to evaluate the resistance to fracture in terms of the stress intensity as a function of age, which is performed for samples of both male and female. Statistical analysis of tensile and compressive strength is summarised in Table 1. The mean tensile strength in males is found higher than females. The similar trend is observed in relation to compressive strength. At the tissue level, the corresponding mechanical properties are significantly reduced by aging with P < 0.001.

Table 1.

Mechanical properties for human cortical femur bone of male and female

The ultimate tensile stress showed no significant difference between the young ages, a considerable change is noticed in middle age groups, and significant changes were observed with the old age groups. Young's modulus is calculated by obtaining the ratio of tensile stress to tensile strain. Young's modulus showed an initial slow increase in young and middle age groups from 20 to 35 years in both male and female, but is significantly larger in the old age group for both the genders with a maximum at 70 to 80 years.

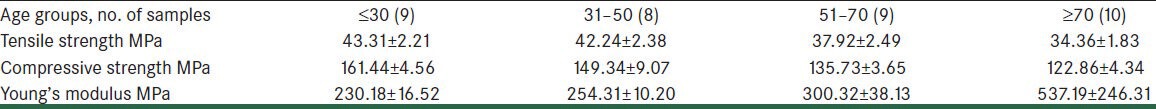

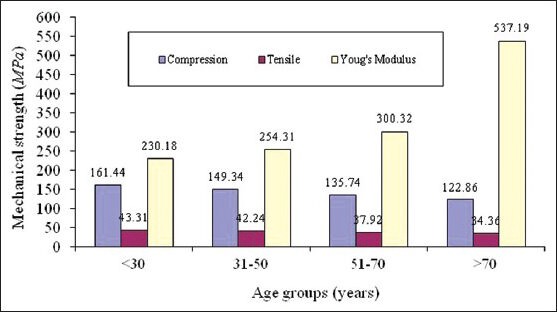

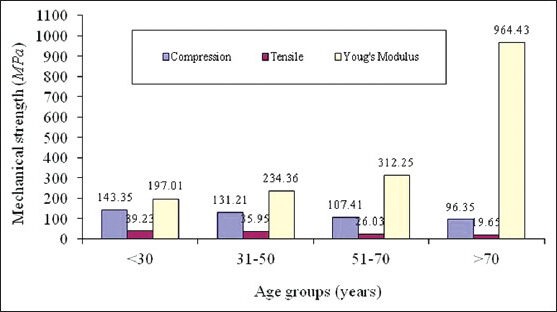

Table 2 summarises statistical analysis of mechanical properties of human cortical femur bone for males. In the age group 30 years and below, 9 samples are tested and the mean tensile strength is found highest among other age groups. The Young's modulus is the least compared to other age groups. This shows that bones are stronger in this age group also and more ductile comparatively. In the age group of 31-50 years 8 samples are examined, in the age group of 51-70 years 9 samples were examined. Significant reduction in tensile and compressive strength is observed in these two age groups. In the age group of above 70 years, there were 10 samples examined. The Young's modulus of this age group indicates as age advances strain induced in tissue level is less hence, bones becomes brittle. Figure 1 show the comparative analysis of compressive strength, tensile strength and Young's modulus for male.

Table 2.

Mechanical properties for male cortical femur bone

Figure 1.

Comparative analysis of compressive, tensile strength and young's modulus for human femur cortical bone of male

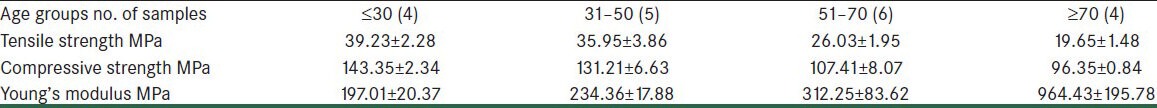

Table 3 summarises statistical analysis of female cortical femur bone of various age groups. In the age group of 30 years and below, 4 samples are examined. In the age group of 31-50 years 5 samples are examined. In the age group of 51-70 years there are 6 samples for examination. In the age group of above 70 years, there are 4 samples examined. By visual inspection during testing, the failure strength is estimated. At the tissue level, the corresponding mechanical properties are significantly reduced by aging with P < 0.001 except Young's modulus. It is clearly noticed that as age advances tensile and compressive strengths reduces where as Young's modulus increases drastically which indicates bone fragility in older age. Figure 2 show the comparative analysis of compressive strength, tensile strength and Young's modulus for female.

Table 3.

Mechanical properties for female cortical femur bone

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of compressive strength, tensile strength and young's modulus for human femur cortical bone of female

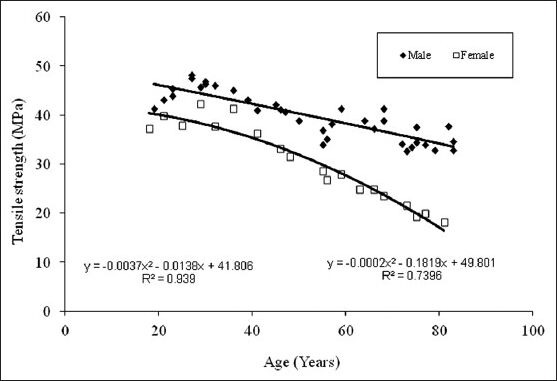

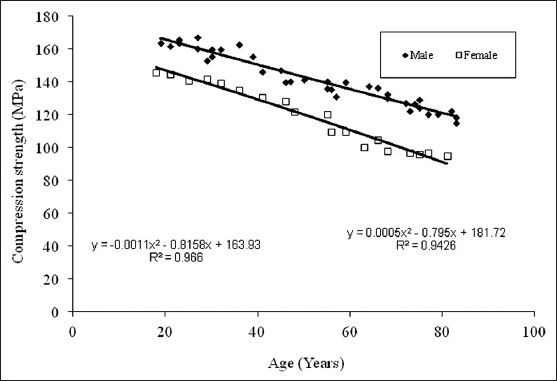

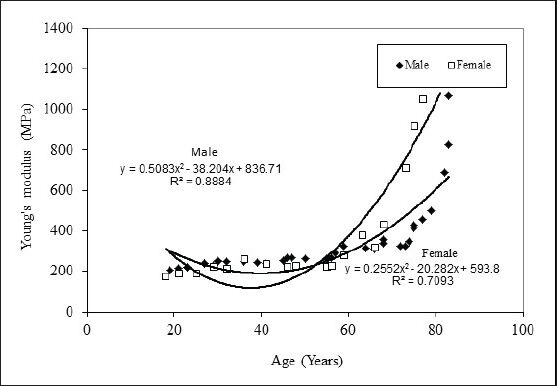

Figure 3 show the tensile load behaviour with respect to age for male and females. It is observed that tensile strength reduces as age advances, male show higher bone strength than female. Curve fit is obtained of second degree polynomial expression y = −0.0037x2 −0.0138x+41.808 and trend line is obtained with R2 value for male trend line being 0.939 and that y = −0.0002x2 −0.1819x+49.801 for female R2 value is 0.739, hence in the given range of age from 19 to 83 years one can find out corresponding tensile strengths. Figure 4 shows the compressive load behaviour with respect to age for male and females. It is observed that compressive strengths reduce as age advances, male show higher bone strength than female in compression testing also. Curve fit is obtained of second degree polynomial expression y = −0.001x2 −0.8158x+163.93 and trend line is obtained with R2 value for male trend line being 0.966 and that for female y = 0.0005x2 −0.795x+181.72 with R2 value as 0. 942, hence in the given range of age from 19 to 83 years one can find out corresponding compressive strengths. Variation in Young's modulus with age for human femur cortical bone of male and female is shown in Figure 5, curve fit is obtained is of second degree polynomial expression y = 0.5083x2 −38.204x+836.71 with R2 value 0.888 for male. It is observed that it is almost constant till the age of 55 years, a small increase is found in the age 55 to 75 years and a significant increase after the age of 75 years and above. This clearly indicates that in males bone is elastic till the age of 55 years which is due to the compactness in the bone tissue organisation and in older ages pores induces into the bone tissue, and decrease in the density and bone turns it to be brittle. In female, till the age of 55 years there is no considerable variation is observed. It is noted that a significant increase after the age of 55 years and above. Curve fit is obtained of second degree polynomial expression y = 0.2552x2 −20.282x+593.8 with R2 value 0.709. This clearly indicates that bone is turning towards brittle after 55 years of age in females.

Figure 3.

Tensile strength vs age for the femur cortical bone

Figure 4.

Compressive strength vs age for the femur cortical bone

Figure 5.

Young's modulus vs age for femur cortical bone

DISCUSSION

The strength and flexibility of the human skeletal system depend on a basic framework of collagen fibres. In the process of aging, changes occur in the collagenous frame work. The major changes are an increase in rigidity of the tissue, the fibres ultimately becoming brittle. Such changes are clearly deleterious to the optimal functioning skeletal system. The changes in collagen cross-linking are major cause for observed change in mechanical properties also the elastic properties with respect to age.[12,13]

The presence of damage in bone tissue has been shown to increase the ultimate strain of the organic matrix of the damaged bone. The organic matrix of bone tissue acts to transmit forces, transfer forces among the bone mineral platelets, and prevent bone tissue from failing prematurely as a brittle material. Under excess load, deformation of collagen fibers involves stretching, slippage of laterally adjoining elements and separation and ultimately defibrillation of the fibrils from the overlap regions under shear force transmission.[13]

The results of our tests are quite different from those of similar works previously reported. For example, Winwood et al. (2006) tested fresh human femoral compact bone specimens in compression and found the failure strength of an average 210 MPa. Nalla et al., (2002) conducted an extensive study on bending strength of human cortical bone under wet condition and the elastic modulus reported is 24.2 GPa. According to the study conducted by Novitskaya et al., (2011) the elastic modulus for cortical femoral bone is 22.6 GPa for Bovine bone under wet condition.[12,14,15]

Several structural features of collagen bestow particular tissues with mechanical properties appropriate to their widely varying functions. The total collagen content of the tissue is obviously an important determinant of mechanical strength. The ability of the tissue to sustain an applied load is also determined by the orientation of the fibres which can vary markedly between tissues. The collagen fibrils possess little strength in compression but exhibit a very high tensile strength. The tensile and compressive strength decreases with age. Little change occurs in the Young's modulus during maturation but considerable in old age. There is an increase in failure stress accompanied by a decrease in failure strain indicating increased cohesion between the micro fibrils, thus preventing slippage.[16] The diameter of the collagen fibres also plays a significant role in determining the mechanical properties of the tissue. The ability to withstand high stress levels is related to the proportion of large diameter fibrils. As the diameter increases the flexibility of the tissue decreases and there is a decrease in the ability to resist crack propagation. In some tissues there is a bimodal distribution of fibre diameter, the voids between the large fibres being filled by small fibres, thus allowing a high collagen content but maintaining a flexibility of the tissue. With maturation, fibril diameters increase and may be either unimodular or bimodally distributed, thus as age advances elastic properties and mechanical strength reduces.[8,17,18]

The age induced decrease in the fracture toughness of bone is quantified in terms of resistance to both crack initiation and crack growth. As the microstructural factors affecting crack initiation and growth in most materials are invariably quite distinct, the challenge is to identify and quantify the specific mechanisms affecting each process in terms of the changes that occur in the micro or ultra structure of bone with age.[19,20]

The degree of bone mass attained is governed by hormonal, nutritional and mechanical factors. At all ages women have a lower bone mass then men and with the increasing age, this gap widens. For cortical bone, a slow loss of bone mass begins at about age of 40 years in females and at 50 years in males. Additionally women generally experience an accelerated period of bone loss around the menopause. This accelerated loss is associated with the reduction of estrogen. The role of estrogen deficiency appears to involve an increase in bone resorption as well as a diminution of bone formation. Thus in males and females, estrogen has both a catabolic and an anabolic effect on bone throughout life. In older men, osteoporosis is more closely related to low estrogen than to low androgen levels.[21,22]

CONCLUSION

Bone strength failure analysis is carried out to evaluate the resistance to fracture in both the genders. Mechanical behaviour of bone is gender and age dependent. The results of this study demonstrate age-related degradation in tissue level mechanical properties of human femoral cortical bone. The results show that male bone specimens show higher failure strength and elasticity than compared to female at all age groups.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vashishth D, Sit S. Florida: Summer Bioengineering Conference; 2003. Age-related changes in bending fatigue of human cortical bone. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng Y, Qin YX, Di-Masi E, Rafailovich M, Pernodet N. Bio mineralization of a self-assembled extracellular matrix for bone tissue engineering. J Tissue Eng. 2009;15:355–65. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2007.0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thurner PJ, Chen CG, Ionova-Martin S, Sun L, Harman A, Porter A, et al. Osteopontin deficiency increases bone fragility but preserves bone mass. J Bone. 2010;46:1564–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Loveridge N, Power J, Reeve J, Boyde A. Bone mineralization density and femoral neck fragility. J Bone. 2004;35:929–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen QZ, Wong CT, Lu WW, Cheung KM, Leong JC, Luk KD. Strengthening mechanisms of bone bonding to crystalline hydroxyapatite in vivo. Biomaterials. 2004;25:4243–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rubin CD. Emerging concepts in osteoporosis and bone strength. J Med Biolog Eng. 2005;21:1049–56. doi: 10.1185/030079905X50525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tomar V. Insights into the effects of tensile and compressive loadings on microstucture dependent fracture of trabecular bone. J Eng Fract Mech. 2009;76:884–97. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey AJ, Paul RG, Knott L. Mechanisms of maturation and ageing of collagen. Mech Ageing Dev. 1998;106:1–56. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(98)00119-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bakar MS, Cheng MH, Tang SM, Yu SC. Tensile properties, tension-tension fatigue and biological response of polyetheretherketone-hydroxyapatite composites for load-bearing orthopaedic implants. J Biomaterials. 2003;24:2245–50. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, Balooch M, Ritchie RO. Role of microstructure in the aging-related deterioration of the toughness of human cortical bone. J Mater Sci Eng. 2006;26:1251–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ritchie RO, Kinney JH, Kruzic JJ, Nalla RK. Cortical bone fracture, in Wiley Encyclopedia of Biomedical Engineering. 2006:32–45. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nalla RK, Kruzic JJ, Kinney JH, Ritchie RO. Effect of aging on the toughness of human cortical bone: Evaluation by R-curves. Bone. 2004;35:1240–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gray RJ, Korbacher G. Compressive fatigue behaviour of bovine compact bone. J Biomech. 1974;7:287–92. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(74)90020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Winwood K, Zioupos P, Currey JD, Cotton JR, Taylor M. The importance of the elastic and plastic components of strain in tensile and compressive fatigue of human cortical bone in relation to orthopaedic biomechanics. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2006;6:134–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Novitskaya E, Chen PY, Hamed E, Li J, Lubarda VA, Jasiuk I, et al. Recent advances on the measurement and calculation of the elastic moduli of cortical and trabecular bone: A review. J Theoret Appl Mech. 2011;38:209–97. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kotha SP, Guzelsu N. Tensile damage and its effects on cortical bone. J Biomech. 2003;36:1683–9. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00169-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rho JY, Zioupos P, Curry JD, Pharr GM. Microstructural elasticity and regional heterogeneity in human femoral bone of various ages examined by nano-indentation. J Biomech. 2002;35:189–98. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(01)00199-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kotha SP, Guzelsu N. Modeling the tensile mechanical behaviour of bone along the longitudinal direction. J Theor Biol. 2002;219:269–79. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2002.3120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gupta HS, Zioupos P. Fracture of bone tissue: The how's and the why's. J Med Eng Phys. 2008;30:1209–26. doi: 10.1016/j.medengphy.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffler CE, Moore KE, Kozloff K, Zysset PK, Goldstein SA. Age, Gender, and Bone Lamellae Elastic Moduli. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:432–7. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo G, Kaufman JJ, Chiabrera A, Bianco B, Kinney JH, Haupt D, et al. Computational methods for ultrasonic bone assessment. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1999;25:823–30. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(99)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.George WT, Vashishth D. Susceptibility of aging human bone to mixed-mode fracture increases bone fragility. Bone. 2006;38:105–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]