Abstract

Horseshoe crabs (order Xiphosura) are often referred to as an ancient order of marine chelicerates and have been considered as keystone taxa for the understanding of chelicerate evolution. However, the mitochondrial genome of this order is only available from a single species, Limulus polyphemus. In the present study, we analyzed the complete mitochondrial genomes from two Asian horseshoe crabs, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda and Tachypleus tridentatus to offer novel data for the evolutionary relationship within Xiphosura and their position in the chelicerate phylogeny. The mitochondrial genomes of C. rotundicauda (15,033 bp) and T. tridentatus (15,006 bp) encode 13 protein-coding genes, two ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes, and 22 transfer RNA (tRNA) genes. Overall sequences and genome structure of two Asian species were highly similar to that of Limulus polyphemus, though clear differences among three were found in the stem-loop structure of the putative control region. In the phylogenetic analysis with complete mitochondrial genomes of 43 chelicerate species, C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus were recovered as a monophyly, while L. polyphemus solely formed an independent clade. Xiphosuran species were placed at the basal root of the tree, and major other chelicerate taxa were clustered in a single monophyly, clearly confirming that horseshoe crabs composed an ancestral taxon among chelicerates. By contrast, the phylogenetic tree without the information of Asian horseshoe crabs did not support monophyletic clustering of other chelicerates. In conclusion, our analyses may provide more robust and reliable perspective on the study of evolutionary history for chelicerates than earlier analyses with a single Atlantic species.

Keywords: Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, Tachypleus tridentatus, Horseshoe crabs, Xiphosura, Mitochondrial genome, Phylogenetics

Introduction

Horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura, Arthorpoda) are marine chelicerates dwelling shallow waters on sandy or muddy bottoms. The Limulidae, only living family of Xiphosura, contains four horseshoe crab species, Tachypleus tridentatus Leach, Tachypleus gigas Müller, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda Latreille and Limulus polyphemus Linnaeus 1. The Atlantic horseshoe crab, L. polyphemus, occurs along the eastern coast of North America, while the remaining three species are widely distributed across Asia from Southeast to Northeast 1. The horseshoe crabs have been dramatically decreased in population sizes and many populations have extirpated throughout much of their ranges in the world, probably due to the global degradation of coastal areas.

Despite its name, horseshoe crabs are rather more closely related to arachnids (subphylum Chelicerata) than to crabs (subphylum Crustacea) 1-3. They are also referred to as living fossil, since little change has been made in their external morphologies over the last 450 million years 1-3. Phylogenetic relationship among four living horseshoe crabs remains scientifically unresolved yet. Two Tachypleus species have been known to compose a monophyletic assemblage on the basis of morphological evaluation 4. Amino acid sequencing 5 and interspecific crossing experiments 6 showed rather different results suggesting that T. tridentatus should be more closely related to C. rotundicauta than to T. gigas. However, studies based on different mtDNA regions failed to provide a congruent pattern; for example, T. gigas and C. rotundicauda were clustered as a monophyly in the combined analyses using 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) and cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) 7, while T. gigas formed the closest relationship with T. tridentatus in the combined analysis using 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA and COI 8.

Xiphosura has been considered as an ancestral taxon in chelicerates as well as arthropods 9, 10, and the complete mitochondrial genome of L. polyphemus has frequently been used to resolve the phylogenetic relationships among chelicerates 3, 11. However, additional mitochondrial genomic information of horseshoe crab species is critically required to reconstruct the robust evolutionary relationship among chelicerates as well as arthropods, because the phylogenetic relationship between L. polyphemus and the remaining Asian species is still vague. Here, the complete mitochondrial genomes of two Asian horseshoe crabs, C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus were analyzed to provide novel data for the relationship among species within the order and the placement of horseshoe crabs in the phylogenetic tree of chelicerates.

Materials and methods

Sampling

Specimens of Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda was purchased from a pet shop (http://www.hanqua.co.kr, Republic of Korea). The tissue sample of Tachypleus tridentatus for analyses was given from Department of Biology, Daegu University (Daegu, Republic of Korea). The remaining tissue specimens were deposited in the Department of Biology, Teacher's College, Kyungpook National University (voucher numbers, HC-13-01: C. rotundicauda; HC-13-02: T. tridentatus). Total cellular DNA was extracted using the DNeasy Tissue Kit (QIAGEN Co., Germany) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Amplification and sequencing

The mitochondrial genomes were amplified using long-range PCR 12 with primer sets shown in Table 1 and the Expand Long Template PCR Kit (Roche Co., Germany). The PCR setting was as followed: [92℃ for 2 min], [92℃ for 30 sec, 52℃ for 30 sec, 68℃ for 9 min] × 14, [92℃ for 10 sec, 52℃ for 30 sec, 68℃ for 9 min (+ 20 sec per cycle)] × 24, [68℃ for 5 min]. PCR reactants were loaded on a 1.0 % agarose gel and stained with ethidium bromide to visualize the bands on ultraviolet transilluminator. The PCR products were purified using the PCR Purification Kit (QIAGEN Co., Germany) and sequenced using the primer-walking strategy with the ABI PRISM BigDye terminator system and the ABI3700 model automatic sequencer (Genotech Co., Korea).

Table 1.

Primers used in the long-range PCR for the mitochondrial genome analyses of Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda and Tachypleus tridentatus.

| Segment | Primers | Sequence | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda | |||

| cox1 - rrnL | HCO2498 | 5´-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA-3´ | 34 |

| 16SB | 5´-CCG GTY TGA ACT CAR ATC A-3´ | 35 | |

| rrnL - cox1 | LCO1490 | 5´-GGT CAA CAA ATC ATA AAG ATA TTG G-3' | 34 |

| 16SA | 5´-CGC CTG TTT AHC AAA AAC AT-3´ | 35 | |

| b. Tachypleus tridentatus | |||

| cox1 - rrnL | HCO2498 | 5´-TAA ACT TCA GGG TGA CCA AAA AAT CA-3´ | 34 |

| 16SB | 5´-CCG GTY TGA ACT CAR ATC A-3´ | 35 | |

| rrnL - cob | 16SA | 5´-CGC CTG TTT AHC AAA AAC AT-3´ | 35 |

| COB-F1 | 5'-CGA GTA ATT CAT GCA AAC GGA GC-3' | 13 | |

| cob - cox 1 | Tachy-CytbL | 5´-GCA GGA ACA GGA TGA ACA GT-3´ | This study |

| Tachy-CO1H | 5´-GCA GGA ACA GGA TGA ACA GT-3´ | This study | |

Sequence analysis

Thirteen protein-coding genes and two ribosomal RNA genes were identified based on sequence similarity under BLAST searches in the NCBI database. The boundary of each gene was determined by alignments with the sequences of the American horseshoe crab, L. polyphemus 13 in the Clustal X 2.1 14. The position and secondary structure of tRNA genes were determined by using tRNAscan-SE Search Server 15. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) genes were identified based on sequence similarity in BLAST searches. Alignments of protein coding genes were translated into amino acid sequences to confirm whether the amplified domains are functional with no frame-shifting or no premature stop codons. The complete mitochondrial genome sequences were deposited in the NCBI GenBank under the accession number JQ178358 (C. rotundicauda) and JQ739210 (T. tridentatus). The CG-skew values in both coding and non-coding regions (Table 2) were calculated based on CG - skew = (C - G)/(C+G) 11, 16.

Table 2.

The mitochondrial genome profile of two Asian horseshoe crabs, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda and Tachypleus tridentatus

| Gene | Strand | Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda (15,033 bp) | Tachypleus tridentatus I (15,006 bp) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| position | Size | Codon | Intergenic bp* |

position | Size | Codon | Intergenic bp* |

|||||||

| From | to | bp | Start | Stop | From | to | bp | Start | Stop | |||||

| trnI | H | 1 | 67 | 67 | -2 | 1 | 67 | 67 | -2 | |||||

| trnQ | L | 66 | 132 | 67 | -2 | 66 | 132 | 67 | -2 | |||||

| trnM | H | 131 | 199 | 69 | 0 | 131 | 199 | 69 | 0 | |||||

| nad 2 | H | 200 | 1219 | 1020 | ATT | TAA | -2 | 200 | 1219 | 1020 | ATT | TAA | -2 | |

| trnW | H | 1218 | 1286 | 69 | -1 | 1218 | 1286 | 69 | 1 | |||||

| trnC | L | 1286 | 1350 | 65 | 0 | 1288 | 1351 | 64 | 0 | |||||

| trnY | L | 1351 | 1415 | 65 | -5 | 1352 | 1415 | 64 | -5 | |||||

| cox 1 | H | 1411 | 2946 | 1536 | TTA | TAA | 3 | 1411 | 2946 | 1536 | TTA | TAA | 3 | |

| cox 2 | H | 2950 | 3633 | 684 | ATG | T_ _ | 0 | 2950 | 3633 | 684 | ATG | TAA | 1 | |

| trnK | H | 3635 | 3705 | 71 | 0 | 3635 | 3705 | 71 | -1 | |||||

| trnD | H | 3706 | 3769 | 64 | 0 | 3705 | 3767 | 63 | 0 | |||||

| atp 8 | H | 3770 | 3923 | 154 | ATT | T_ _ | -5 | 3768 | 3923 | 156 | ATT | TAA | -7 | |

| atp 6 | H | 3919 | 4593 | 675 | ATG | TAA | -1 | 3917 | 4591 | 675 | ATG | TAA | -1 | |

| cox 3 | H | 4593 | 5376 | 784 | ATG | T_ _ | 0 | 4591 | 5374 | 784 | ATG | T_ _ | 0 | |

| trnG | H | 5377 | 5442 | 66 | 0 | 5375 | 5438 | 64 | 0 | |||||

| nad 3 | H | 5443 | 5787 | 345 | ATA | TAA | 6 | 5439 | 5783 | 345 | ATT | TAA | 6 | |

| trnA | H | 5794 | 5863 | 70 | 0 | 5790 | 5857 | 68 | 0 | |||||

| trnR | H | 5864 | 5925 | 62 | -1 | 5858 | 5919 | 62 | -1 | |||||

| trnN | H | 5925 | 5994 | 70 | -1 | 5919 | 5988 | 70 | -1 | |||||

| trnS2 | H | 5994 | 6059 | 66 | -1 | 5988 | 6054 | 67 | -1 | |||||

| trnE | H | 6059 | 6121 | 63 | 6 | 6054 | 6117 | 64 | 11 | |||||

| trnF | L | 6128 | 6192 | 65 | 0 | 6129 | 6192 | 64 | 0 | |||||

| nad 5 | L | 6193 | 7906 | 1714 | TTG | T_ _ | 0 | 6193 | 7906 | 1714 | TTG | T_ _ | 0 | |

| trnH | L | 7907 | 7970 | 64 | 1 | 7907 | 7970 | 64 | 1 | |||||

| nad 4 | L | 7972 | 9309 | 1338 | ATG | TAG | 4 | 7972 | 9315 | 1344 | ATT | TAA | 1 | |

| nad 4L | L | 9303 | 9602 | 300 | ATG | T_ _ | 2 | 9317 | 9602 | 286 | ATG | T_ _ | 2 | |

| trnT | H | 9605 | 9668 | 64 | 1 | 9605 | 9669 | 65 | 1 | |||||

| trnP | L | 9670 | 9735 | 66 | 3 | 9671 | 9735 | 65 | 3 | |||||

| nad 6 | H | 9739 | 10200 | 462 | ATT | TAA | -1 | 9739 | 10200 | 462 | ATC | TAA | -1 | |

| cob | H | 10200 | 11328 | 1129 | ATG | T_ _ | 0 | 10200 | 11328 | 1129 | ATG | T_ _ | 0 | |

| trnS1 | H | 11329 | 11396 | 68 | 24 | 11329 | 11397 | 69 | 9 | |||||

| nad1 | L | 11421 | 12356 | 936 | TTG | TAA | 0 | 11407 | 12339 | 933 | TTG | TAA | 0 | |

| trnL1 | L | 12354 | 12419 | 66 | 1 | 12340 | 12405 | 66 | 1 | |||||

| trnL2 | L | 12421 | 12487 | 67 | 0 | 12407 | 12473 | 67 | 0 | |||||

| rrnL | L | 12488 | 13787 | 1300 | 0 | 12474 | 13767 | 1294 | 0 | |||||

| trnV | L | 13788 | 13857 | 70 | 0 | 13768 | 13837 | 70 | 0 | |||||

| rrnS | L | 13858 | 14673 | 816 | 0 | 13838 | 14637 | 800 | 0 | |||||

| CR | 14674 | 15033 | 360 | 0 | 14638 | 15006 | 369 | 0 | ||||||

*Intergenic bp indicates gap nucleotides (positive value) or overlapped nucleotides (negative value) between two adjacent genes

Phylogenetic analysis

The mitochondrial genomes of C. rotundicauta and T. tridentatus were analyzed in the phylogenetic tree using a total of 41 other chelicerate mitochondrial genomes retrieved from NCBI GenBank (Supplementary Table 1). The nucleic acid sequences of 12 protein-coding genes were aligned using Bio-Edit sequence alignment editor (Ibis Biosciences, USA). The atp8 gene was excluded from the analyses, because the substitution rate was too high to recover the true phylogeny and too short to provide enough numbers of phylogenetically informative characters. Using the annotated gene boundary information, each protein coding gene was excised from the genomic sequence and put into an individual file. The program EMBOSS Transeq 17 was used to translate the nucleotide sequences into amino acid sequences based on the invertebrate mitochondrial genetic code. CLUSTAL X was finally used to align amino acid sequences of 12 genes. Only well-aligned and conserved alignment sites were extracted from each alignment subset using Gblock ver. 0.91b program 18 with the default setting. The extracted conserved blocks of amino acids were subsequently concatenated into a unified, single large alignment set.

The refined alignment was subjected to two different tree-making algorithms: the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods. The best fitting model of sequence evolution was tested by ProtTest ver. 1.3 19 under Akaike information criterion for the amino acid data. The mtREV 20 + I + Γ was consequently selected as the best fitting model and employed for the phylogenetic reconstruction. The ML analysis was carried out using PHYML v2.4.4 21. The bootstrap proportions (BPML; 1000 replicates) of the ML tree were obtained by the fast-ML method using PHYML. The BI analyses implemented in MrBayes v.3.1 22 with 1,000,000 generations, four MCMC chains (one hot and three cold) and burn-in step of the first 1,000. Node confidence values of the tree were presented with Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP).

Results

Genome composition

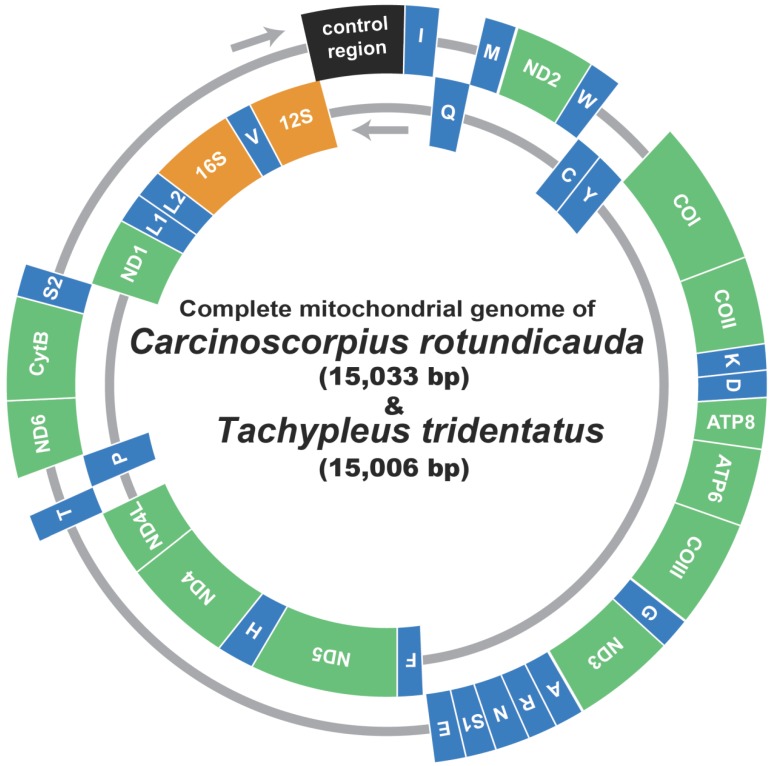

The mitochondrial genomes of C. rotundicauda (15,033 bp) and T. tridentatus (15,006 bp) included 13 protein coding genes (nad1 - 6, nad4L, cox1 - 3, cob, atp6 and atp8), two ribosomal RNA genes (rrnL and rrnS), 22 tRNA genes and one large non-coding region (putative control region, CR) (Fig. 1; Table 2). In both genomes, nine protein coding genes (nad2, cox1, cox2, atp8, atp6, cox3, nad3, nad6, and cob) were encoded on the heavy strand along with 13 tRNAs (trnI, trnM, trnW, trnK, trnD, trnG, trnA, trnR, trnN, trnS2, trnE, trnT, and trnS2), while the remaining four protein coding genes (nad5, nad4, nad4L, nad1) with nine tRNAs (trnQ, trnC, trnY, trnF, trnH, trnP, trnL1, trnL2, and trnV) and two rRNAs (rrnL and rrnS) were encoded on the light strand (Fig. 1; Table 2). Overall gene arrangement of both mitochondrial genomes was completely identical to that of L. polyphemus 13.

Fig 1.

Gene map of the mitochondrial genome of Asian horseshoe crabs, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda and Tachypleus tridentatus. Thirteen protein-coding genes and 2 ribosomal RNA genes are abbreviated as follows: nad1-6 and nad4L, NADH dehydrogenase subunits 1-6 and 4L; cox 1-3, cytochrome C oxidase subunits I-III; cob, cytochrome b apoenzyme; atp 6 and 8, ATPase subunits 6 and 8. The 22 transfer RNA genes are identified by the IUPAC amino acid single-letter codes.

The gene components were rather loosely juxtaposed with 51/23 (C. rotundicauda) and 40/24 (T. tridentatus) of gap/overlapping nucleotides, considering that of L. polyphemus (23/19; Table 2) 13. Although the overall A + T contents of 73.8 % in C. rotundicauda and 74.0 % in T. tridentatus were relatively higher than that of L. polyphemus (67.57 %), those values are within the range (60.2 - 80.4 %) of chelicerates (Supplementary Table 1). The overall pattern of nucleotide skew was highly similar among three mitochondrial genomes including that of L. polyphemus, with only an exception found on the putative control region (Table 3).

Table 3.

AT/CG skews in the mitochondrial protein coding genes (PCG), 2 rRNA genes, CR and the entire mitochondrial genome from three horseshoe crabs, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, Tachypleus tridentatus, and Limulus polyphemus

| Gene | AT-skew | CG-skew | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. rotundicauda | T. tridentatus | L. polyphemus | C. rotundicauda | T. tridentatus | L. polyphemus | |||||

| cox1 | -0.065 | -0.089 | 0.044 | 0.153 | 0.146 | 0.210 | ||||

| cox2 | -0.002 | -0.035 | 0.036 | 0.305 | 0.281 | 0.331 | ||||

| cox3 | -0.130 | -0.141 | -0.073 | 0.230 | 0.183 | 0.333 | ||||

| atp8 | -0.108 | -0.088 | 0.097 | 0.750 | 0.548 | 0.721 | ||||

| atp6 | -0.107 | -0.088 | -0.029 | 0.456 | 0.398 | 0.526 | ||||

| nad1 | -0.243 | -0.200 | -0.388 | -0.438 | -0.414 | -0.511 | ||||

| nad2 | -0.140 | -0.143 | -0.052 | 0.496 | 0.441 | 0.570 | ||||

| nad3 | -0.183 | -0.254 | -0.042 | 0.462 | 0.341 | 0.524 | ||||

| nad4 | -0.257 | -0.251 | -0.374 | -0.432 | -0.393 | -0.485 | ||||

| nad4L | -0.162 | -0.139 | -0.217 | -0.697 | -0.657 | -0.636 | ||||

| nad5 | -0.269 | -0.250 | -0.319 | -0.401 | -0.348 | -0.396 | ||||

| nad6 | -0.119 | -0.070 | -0.006 | 0.609 | 0.612 | 0.629 | ||||

| cob | -0.113 | -0.159 | -0.081 | 0.317 | 0.306 | 0.427 | ||||

| rrnL | 0.044 | 0.030 | 0.148 | 0.456 | 0.429 | 0.447 | ||||

| rrnS | 0.088 | 0.104 | 0.145 | 0.352 | 0.333 | 0.331 | ||||

| CR | -0.026 | -0.023 | -0.046 | -0.111 | -0.115 | 0.077 | ||||

| 13 PCG | -0.162 | -0.163 | -0.160 | 0.046 | 0.042 | 0.088 | ||||

| overall | 0.036 | 0.024 | 0.111 | 0.346 | 0.315 | 0.399 | ||||

Protein coding genes

The inferred start/stop codons for protein coding genes of both C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus are listed in Table 2. All of the protein coding genes in both mitochondrial genomes were initiated by ATN, with the exceptions in cox1, nad1 and nad5 (Table 2). The open reading frame of cox1 in both Asian horseshoe crabs started with TTA, while that of nad1 and nad5 started with TTG. The canonical stop codon (TAA or TAG) occurs in seven protein coding genes (nad1, nad2, cox1, atp6, nad3, nad4 and nad6; Table 2), while the remaining six (nad5, nad4L, cob, cox2, cox3 and atp8) had incomplete T- or TA- stop codons (Table 2). The codon usage pattern of the 13 protein coding genes is provided in Table 4. A + T rich codons, such as Leu (UUA), Ile (AUU) and Phe (UUU), are frequent in both C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus (Table 4).

Table 4.

Codon usage pattern of the 13 mitochondrial protein-coding genes from three horseshoe crab species, Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, Tachypleus tridentatus, and Limulus polyphemus

| Amino acids | Codon | No. | Amino acids | Codon | No. | Amino acids | Codon | No. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | T | L | C | T | L | C | T | L | |||||||||

| Nonpolar | Phe | UUC | 46 | 66 | 85 | Ser | AGA | 75 | 83 | 66 | |||||||

| Ala | GCA | 48 | 45 | 55 | UUU | 333 | 310 | 246 | AGC | 5 | 4 | 8 | |||||

| GCC | 27 | 16 | 39 | Trp | UGA | 101 | 102 | 94 | AGG | 2 | 7 | 12 | |||||

| GCG | 4 | 9 | 6 | UGG | 10 | 6 | 17 | AGU | 24 | 21 | 22 | ||||||

| GCU | 73 | 84 | 76 | UCA | 116 | 114 | 98 | ||||||||||

| Ile | AUC | 43 | 42 | 107 | Polar | UCC | 49 | 31 | 65 | ||||||||

| AUU | 346 | 335 | 241 | Asn | AAU | 126 | 139 | 103 | UCG | 2 | 3 | 6 | |||||

| Leu | CUA | 41 | 42 | 94 | AAC | 35 | 20 | 44 | UCU | 106 | 122 | 110 | |||||

| CUC | 17 | 18 | 55 | Cys | UGC | 7 | 7 | 9 | Acidic | ||||||||

| CUG | 2 | 1 | 4 | UGU | 43 | 47 | 40 | Asp | GAC | 14 | 11 | 24 | |||||

| CUU | 85 | 80 | 106 | Gln | CAA | 59 | 63 | 52 | GAU | 48 | 51 | 36 | |||||

| UUA | 348 | 363 | 226 | CAG | 10 | 3 | 15 | Glu | GAA | 68 | 69 | 64 | |||||

| UUG | 44 | 38 | 84 | Gly | GGA | 110 | 119 | 109 | GAG | 14 | 14 | 23 | |||||

| Met | AUA | 215 | 229 | 171 | GGC | 8 | 11 | 21 | Basic | ||||||||

| AUG | 40 | 23 | 43 | GGG | 32 | 28 | 66 | Arg | CGA | 32 | 35 | 34 | |||||

| Pro | CCA | 60 | 64 | 52 | GGU | 67 | 59 | 41 | CGC | 3 | 3 | 7 | |||||

| CCC | 14 | 8 | 27 | Thr | ACA | 78 | 77 | 84 | CGG | 4 | 2 | 7 | |||||

| CCG | 2 | 2 | 4 | ACC | 29 | 31 | 40 | CGU | 20 | 20 | 14 | ||||||

| CCU | 60 | 68 | 69 | ACG | 1 | 0 | 2 | His | CAC | 19 | 13 | 41 | |||||

| Val | GUA | 76 | 62 | 82 | ACU | 59 | 65 | 53 | CAU | 56 | 64 | 37 | |||||

| GUC | 6 | 5 | 14 | Tyr | UAC | 26 | 20 | 34 | Lys | AAA | 85 | 84 | 66 | ||||

| GUG | 11 | 19 | 36 | UAU | 105 | 108 | 87 | AAG | 16 | 8 | 19 | ||||||

| GUU | 73 | 86 | 90 | ||||||||||||||

Bold numbers indicate strong differences (+/-25%) to Limulus polyphemus.

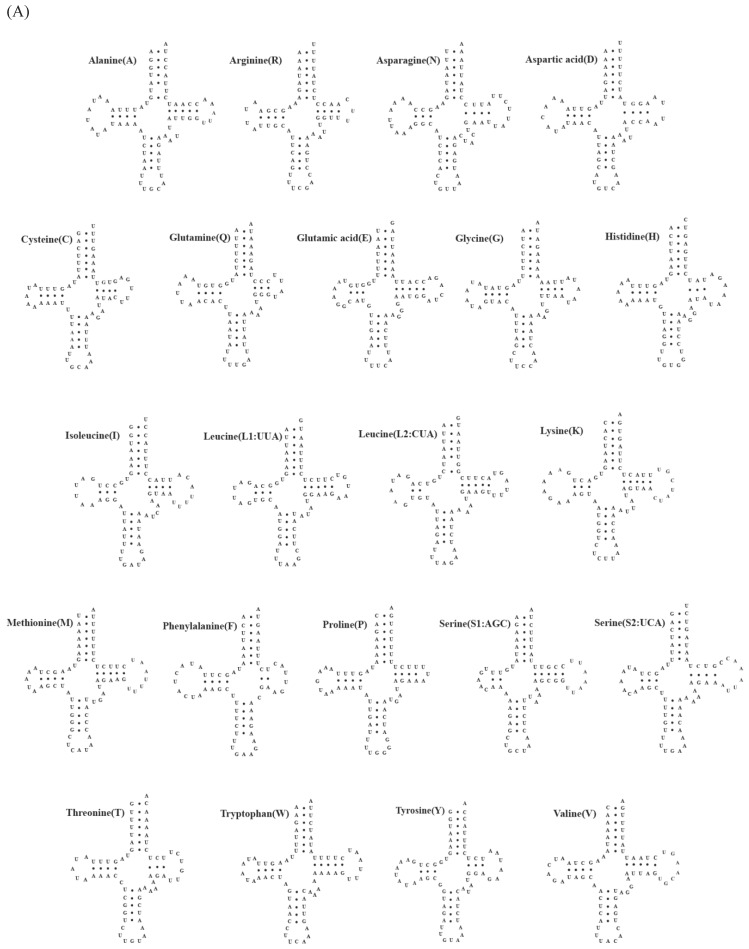

Transfer and ribosomal RNA genes

A total of 22 tRNA genes ranging from 62 to 73 bp in length were identified in mitochondrial genomes of both C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus. The putative secondary structure for each tRNA gene could be predicted based on the sequences (Fig. 2). The sequences, anticodon nucleotides, and secondary structures of tRNA genes from both C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus were very similar to those observed in L. polyphemus 13. All of the tRNA genes were capable of forming typical cloverleaf secondary structures (dihydrouridine, DHU), with an exception of trnS1; trnS1 lacked DHU arm in T. tridentatus (Fig. 2B) and had a shortened stem (2 bp) in C. rotundicauda (Fig. 2A). Two rRNA genes (rrnS and rrnL) were encoded on the light strand and were separated by a trnV in both mitochondrial genomes analyzed. The sizes of rrnS and rrnL were estimated to be 816 bp (rrnS) and 1,301 bp (rrnL) for C. rotundicauda and 800 bp (rrnS) and 1,294 bp for T. tridentatus.

Fig 2.

Putative tRNA secondary structures predicted from the 22 tRNA gene sequences found in the (A) Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda and (B) Tachypleus tridentatus mitochondrial genome.

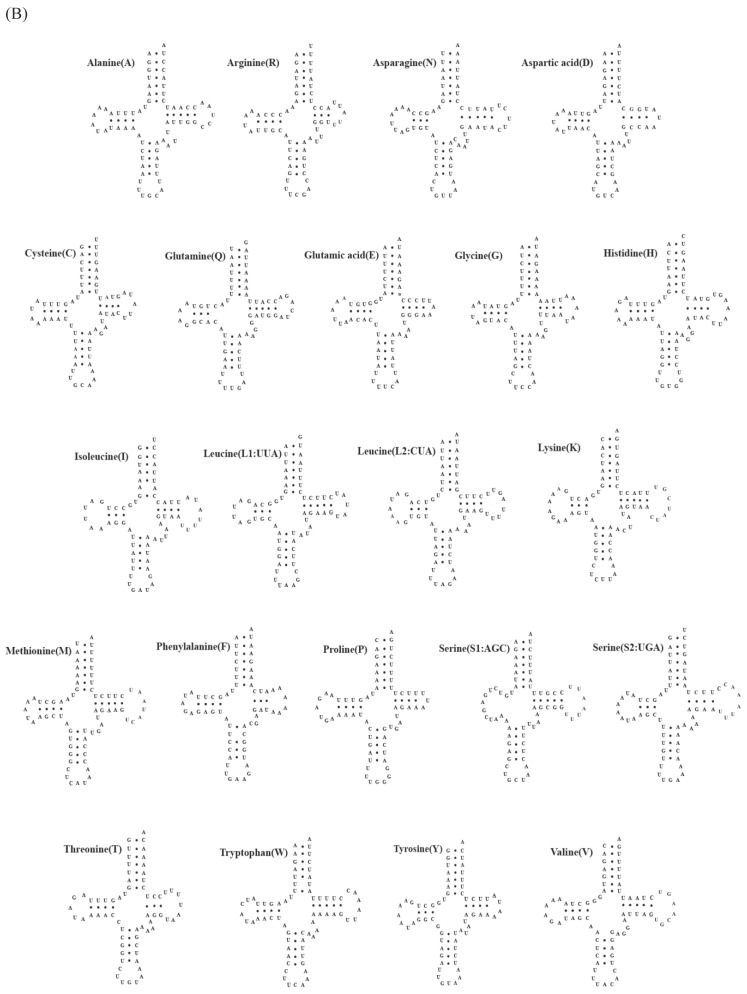

Non-coding regions

The major non-coding regions (putative control region, CR) of 360 bp (C. rotundicauda) and 369 bp (T. tridentatus) were found between rrnS and trnQ (Table 2). The A + T contents in this region were higher, with 85% and 83.47% in C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus, respectively, compared to other regions of the mitochondrial genomes (supplementary Table 1). The sequence of this region is highly conservative among xiphosuran species (Fig. 3A). The stem-loop structure found in C. rotundicauda (Fig. 3B) was composed of the 13 bp stem and 11 bp loop. However, the structure of T. tridentatus was rather complicated with the 10 bp stem and 13 bp loop followed by the alternative 8 bp stem and 12 bp loop (Fig. 3C). The mitochondrial genome of L. polyphemus had such an alternative structure 13, although it does not seem to be stable to build the complete stem-loop structure (Fig. 3D). A small (24 bp) non-coding fragment was found between the trnS (UGA) and nad1 gene in C. rotundicauda (Fig. 3E and Table 2. T. tridentatus and L. polyphemus had just a short (9 bp) and highly conserved non-coding fragment (TTTCTAAA) in this region.

Fig 3.

Comparison in the primary and secondary structures of non-coding regions found in the mitochondrial genomes of Carcinoscorpius rotundicauda, Tachypleus tridentatus and Limulus polyphemus. The CR pair-wise alignment of the three xiphosuran species (A): the dots indicate nts identical to those of the first line in the alignment. Hairpin-like structure (60 bp and 57 bp) from the control region observed in C. rotundicauda (B), T. tridentatus (C), and L. polyphemus (D). An alignment of the gap region between trnS1 (UCN) and nad1 in three xiphosuran species (E): the box indicates a conserved region across three horseshoe crabs. L; L. polyphemus, C; C. rotundicauda, T; T. tridentatus.

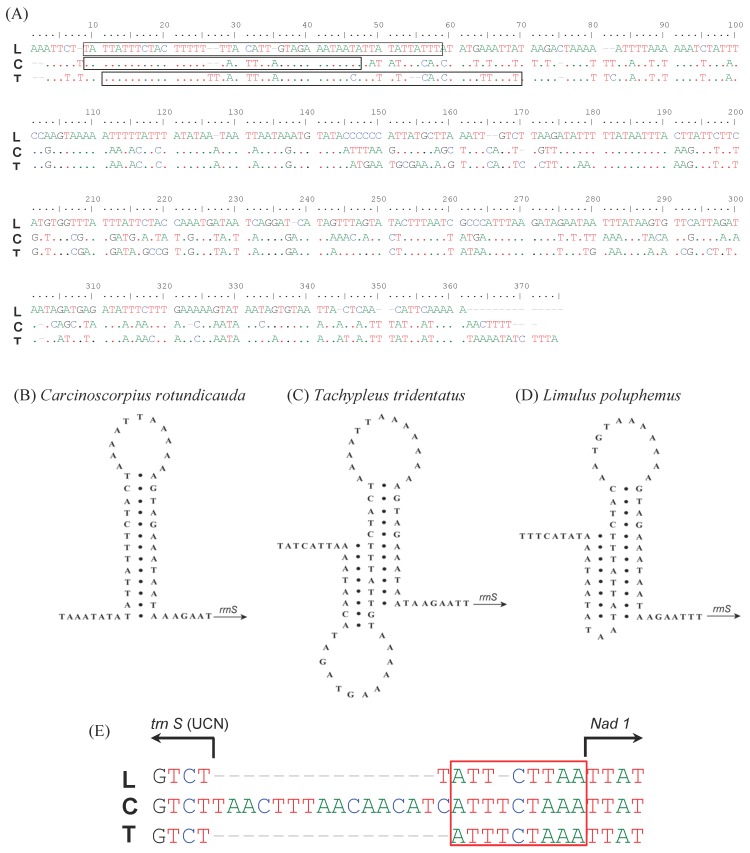

Phylogenetic analyses

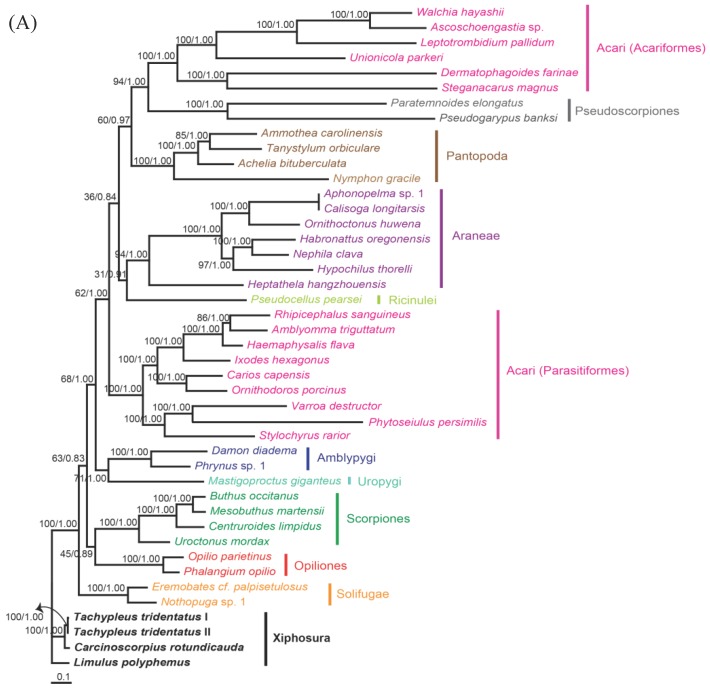

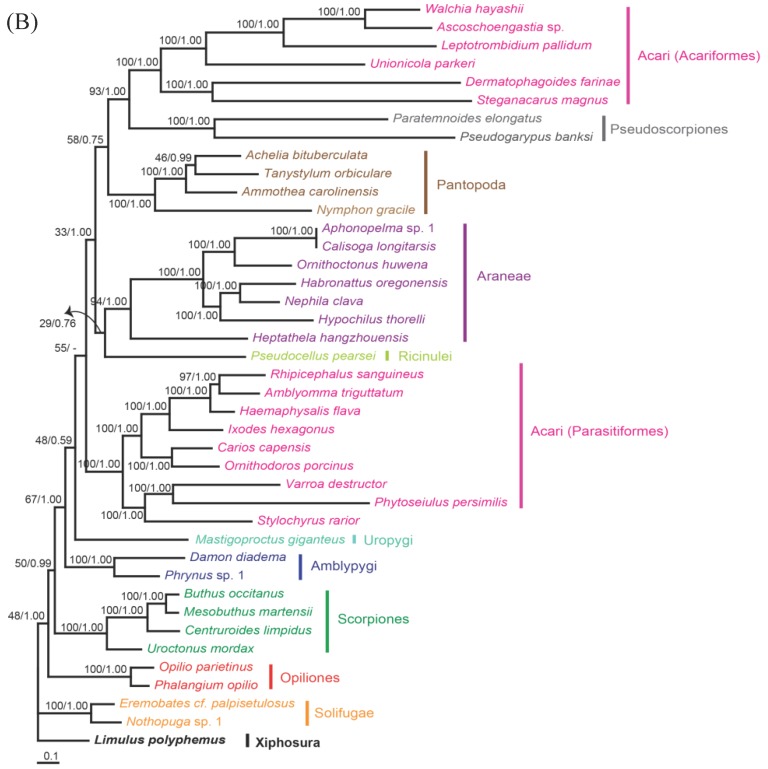

The phylogenetic trees reconstructed from ML and BI algorithms were completely identical in clustering pattern and overall topology (Fig. 4). C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus were recovered as a monophyly (BPML = 100, BPP = 1.00), whereas L. polyphemus solely formed a separate clade from two Asian species (BPML = 100, BPP = 1.00). Horseshoe crabs were placed as a sister relationship to the Arachnids by strong node-supporting values (Fig. 4A). The tree also supported the monophyletic clusterings of 'Opiliones + Scorpions' (BPML = 63, BPP = 0.83), 'Uropigy + Amblypygi' (BPML = 62, BPP = 1.0), Acari (Parasotoformes; BPML = 62, BPP = 1.00), 'Richinulei + Araneae' (BPML = 36, BPP = 0.84), Pantopoda (BPML = 60, BPP = 0.97) and 'Pseudoscorpiones + Acarifomes' (BPML = 94, BPP = 1.00; Fig. 4A). The monophyletic grouping of 'Opiliones + Scorpions' and 'Uropygi + Amblypygi' are compatible with the result from several previous analyses conducted based on morphological characters 23-25. When the Asian horseshoe crabs were not considered in the tree, however, the tree was not resolved to support the monophyly of Arachnida, with Solifugae being independently placed at the basal root (Fig. 4B). In addition, such tree did not support the clustering of 'Opiliones + Scorpions' and 'Uropygi + Amblypygi' (Fig. 4B).

Fig 4.

Maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees of chelicerates based on the amino acid sequences of concatenated 12 mitochondrial protein coding genes. Tree was reconstructed either (A) with three horseshoe species (C. rotundicauda, T. tridentatus and L. polyphemus) or (B) with only L. polyphemus. Numbers at the branch indicate the percentages from ML bootstrapping (left) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (right).

Discussion

The present study was designed to provide critical mitochondrial genome information of C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus necessary for the concrete inference of phylogenetic relationships among species within Xiphosura and their placement within Chelicerata as well as Arthropoda. The overall architecture of both mitochondrial genomes is highly consistent with those previously reported in the Atlantic horseshoe crab, L. polyphemus. Those three mitochondrial genomes share the identical genome content (13 protein coding genes, 2 ribosomal RNA genes, 22 tRNA genes and a single large control region) and overall gene arrangement, as typically shown in many metazoan mitochondrial genomes 13, 26-28. The mitochondrial genomes of C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus are slightly larger than that of L. polyphemus, due to more frequent occurrence of gap nucleotides between genes.

In two Asian horseshoe crabs, ten of the protein coding genes (atp6, atp8, nad2, nad3, nad4. nad6, nad4L, cob, cox2 and cox3) have either Met or Ile as the start codon (ATA, ATG or ATT), while the remaining three (cox1, nad1, and nad5) start with Leu (TTA or TTG). Such start codon pattern was frequently found in a few other chelicerates 25, 26, 29, 30 as well as in several arthropods 31, 32. Six (nad5, nad4L, cob, cox2, cox3 and atp8) protein coding genes have incomplete stop codon. Such truncated stop codons are commonly observed among many arthropod mitochondrial genomes 30-32 and are expected to be converted into a fully functional TAA via post-translational polyadenylation 29.

The sequences, anticodon nucleotides and secondary structures of tRNA genes are highly consistent with those previously reported in the Atlantic horseshoe crab. Most of the tRNA genes form dihydrouridine (DHU) arm. However, such structure is not found in trnS1 of T. tridentatus, and incomplete conformation with shortened stem of 2 bp is observed in C. rotundicauda. Missing of complete DHU arm in trnS1 has been reported among a number of metazoan mitochondrial genomes 29-32.

The A + T rich non-coding regions (putative control regions) were found in both two Asian horseshoe crab mitochondrial genomes. The sequence of this region is highly conservative among xiphosuran species as well as among a variety of arthropods 33. However, the stem-loop structure is highly variable among three xiphosuran species. An interesting feature of stem-loop structure in T. tridentatus is its ability to form an alternative secondary structure that appears to be complete and stable. Although the mitochondrial genome of L. polyphemus has an additional 8 nucleotides complementary to the main stem, it does not appear to be stable. It is also surprising that there is a small non-coding fragment (24 bp) between trnS and nad1 in C. rotundicauda.

In the phylogenetic analysis among 43 chelicerates, C. rotundicauda and T. tridentatus were recovered as a monophyly, whereas L. polyphemus solely forms a separate clade from two Asian species. Such result supports previous findings showing clear genetic differentiation between L. polyphemus and Asian species 7, 8. Major other chelicerate taxa were clustered in a single monophyletic assemblage, three xiphosuran species being placed at the basal root, suggesting that horseshoe crabs should be considered as an ancestral taxon in arthropods as well as in chelicerates. The phylogenetic tree without the information of Asian horseshoe crabs, by contrast, was not resolved to support monophyletic clustering of chelicerates, since solifuges formed a separate cluster. In conclusion, additional information of Xiphosuran mitochondrial genomes provide more robust and reliable perspective on the evolutionary history of chelicerate as well as arthropods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The present work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Science (NRF-2012R1A2A2A01046531 to U. W. H., NRF-2011-0025314 to S. H. R., and NRF-2011-0014704 to H. Y. S.).

References

- 1.Sekiguchi K, Shuster CN. Limits on the global distribution of horseshoe crabs (Limulacea): lessons learned from two lifetimes of observations: Asia and America. In: Tanacredi JT, Botton ML Smith DR, editors. Biology and Conservation of Horseshoe Crabs. Dordrecht: Springer Publishing; 2009. pp. 5–24. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wheeler WC, Hayashi CY. The phylogeny of the extant chelicerate orders. Cladistics. 1998;14:173– 192. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1998.tb00331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masta SE, Longhorn SJ, Boore JL. Arachnid relationships based on mitochondrial genomes: asymmetric nucleotide and amino acid bias affects phylogenetic analyses. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;50:117– 128. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2008.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shuster CN, Anderson LI. A history of skeletal structure: Clues to relationships among species. In: Shuster CN, Barlow RB, Brockmann J, editors. The American Horseshoe Crab. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. pp. 154–188. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shishikura F, Nakamura S, Takahashi K, Sekiguchi K. Horseshoe crab phylogeny based on amino acid sequences of the fibrinopeptide-like peptide. J Exp Zool. 1982;223:89– 91. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sekiguchi K, Sugita H. Systematics and hybridization in the 4 living species of horseshoe crabs. Evolution. 1980;34:712– 718. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1980.tb04010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xia XH. Phylogenetic relationship among horseshoe crab species: effect of substitution models on phylogenetic analyses. Syst Biol. 2000;49:87– 100. doi: 10.1080/10635150050207401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Obst M, Faurby S, Bussarawit S, Funch P. Molecular phylogeny of extant horseshoe crabs (Xiphosura, Limulidae) indicates Paleogene diversification of Asian species. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2012;62:21– 26. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shultz JW. A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological characters. Zool J Linn Soc. 2007;150:221– 265. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staton JL, Daehler LL, Brown WM. Mitochondrial gene arrangement of the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus L.: conservation of major features among arthropod classes. Mol Biol Evol. 1997;14:867– 874. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ovchinnikov S, Masta SE. Pseudoscorpion mitochondria show rearranged genes and genome-wide reductions of RNA gene sizes and inferred structures, yet typical nucleotide composition bias. BMC Evol Biol. 2012;12:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-12-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng S, Chang SY, Gravitt P. Long PCR. Nature. 1994;369:684– 685. doi: 10.1038/369684a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavrov DV, Boore JL, Brown WN. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the horseshoe crab Limulus polyphemus. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:813– 824. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL - X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876– 4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schattner P, Brooks AN, Lowe TM. The tRNAscan-SE: sonscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and sonRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(2):W686– 689. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arabi J, Judson ML, Deharvenq L, Lourenço WR, Cruaud C, Hassanin A. Nucleotide composition of CO1 sequences in Chelicerata (Arthropoda): detecting new mitogenomic rearrangements. J Mol Evol. 2012;74(1-2):81– 95. doi: 10.1007/s00239-012-9490-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McWillian H, Li W, Squizzato S, Park YM, Buso N, Cowley AP, Lopex R. Analysis tool web services from the EMBL-EBI. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:W597– 600. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castresana J. Selection of conserved block from multiple alignments for their use in phylogenetic analysis. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17:540– 552. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abascal F, Zardoya R, Posada D. ProtTest: selection of best-fit models of protein evolution. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(9):2104– 2105. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abascal F, Posada D, Zardoya R. MtArt: a new model of amino acid replacement for Arthropoda. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24(1):1– 5. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guindon S, Gascuel O. A simple, fast, and accurate algorithm to estimate large phylogenies by maximum likelihood. Syst Biol. 2003;52:696– 704. doi: 10.1080/10635150390235520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(12):1572– 1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giribet G, Edgecombe GD, Wheeler WC, Babbitt C. Phylogeny and systematic position of Opiliones: a combined analysis of chelicerate relationships using morphological and molecular data. Cladistics. 2002;18:5– 70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shultz JW. A phylogenetic analysis of the arachnid orders based on morphological characters. Zool J Linn Soc. 2007;150:221– 265. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masta SE, McCall A, Longhorn SJ. Rare genomic changes and mitochondrial sequences provide independent support for congruent relationships among the sea spiders (Arthropoda, Pycnogonida) Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2010;57:59– 70. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masta SE. Mitochondrial rRNA secondary structures and genome arrangements distinguish chelicerates: comparisons with a harvestman (Arachnida: Opiliones: Phalangium opilio) Gene. 2010;449:1– 9. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fahrein K, Talarico G, Braband A, Podsiadlowski L. The complete mitochondrial genome of Pseudocellus pearsei (Chelicerata: Ricinulei) and a comparison of mitochondrial gene rearrangements in Arachnida. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:386. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castellana S, Vicario S, Saccone S. Evolutionary pattern of the mitochondrial genome in metazoa: Exploring the role of mutation and selection in mitochondrial protein-coding genes. Genome Biol. Evol. 2011;3:1067–1079. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evr040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ernsting BR, Edwards DD, Aldred KJ, Fites JS, Neff CR. Mitochondrial genome sequence of Unionicola foili (Acari: Unionicolidae): a unique gene order with implications for phylogenetic inference. Exp Appl Acarol. 2009;49:305– 16. doi: 10.1007/s10493-009-9263-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu GH, Chen F, Chen YZ, Song HQ, Lin RQ, Zhou DH, Zhu XQ. Complete mitochondrial genome sequence data provides genetic evidence that the brown dog tick Rhipicephalus sanguineus (Acar: Ixodidae) represents a species complex. Int J Biol Sci. 2013;9(4):361– 369. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.6081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li H, Gao JY, Liu HY, Liu H, Liang AP, Zhou XG, Cai W. The architecture and complete sequence of mitochondrial genome of an assassin bug Agiosphodrus dohrni (Hemiptera: Reduviidae) Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7(6):792– 804. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang YY, Liu XY, Yang D. The first mitochondrial genome for caddisfly (Insecta: Trichoptera) with phylogenetic implications. Int J Biol Sci. 2014;10(1):53– 63. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.7975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montagna M, Sassera D, Griggio F, Epis S, Bandi C, Gissi C. Tick-box for 3'-end formation of mitochondrial transcripts in Ixodida, basal chelicerates and Drosophila. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(10):e47538. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Folmer O, Black M, Hoeh W, Lutz R, Vrijenhoek R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994;3(5):294– 299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kambhampati S, Smith PT. PCR primers for the amplification of four insect mitochondrial gene fragments. Insect Mol Biol. 1995;4:233– 236. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1995.tb00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.