Background: Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the IRAK genes have been discovered recently. However, the functions of these IRAK SNPs remain largely unknown.

Results: Non-synonymous IRAK2 variant, rs708035, increases NF-κB activity through promoting TRAF6 ubiquitination.

Conclusion: Genetic alteration of IRAK2 affects its regulation on NF-κB activation.

Significance: Our study provides an important insight of IRAK2 SNP in the regulation of NF-κB activation.

Keywords: Cell Biology, Gene Regulation, Inflammation, Signal Transduction, Toll-like Receptors (TLR)

Abstract

The IL-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs) are key regulators of Toll-like receptor (TLR)/IL-1 signaling, which are critical regulators of mammalian inflammation and innate immune response. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the IRAK genes have been discovered recently. However, the functions of these IRAK SNPs remain largely unknown. Here, we found that the non-synonymous IRAK2 variant rs708035 (coding D431E) increases NF-κB activity and leads to more expression of NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory cytokines compared with IRAK2 wild type. Moreover, when IRAK2 knockdown cells reconstituted with siRNA-resistant WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2 were infected with influenza virus, a more obvious induction of IL-6 and a stronger anti-apoptosis effect were observed in D431E-IRAK2 expressing cells. Notably, we also found that the levels of proinflammatory cytokine-IL-6 were indeed higher in people carrying D431E-IRAK2 than those carrying WT-IRAK2. Further study demonstrated that elevated NF-κB activation mediated by the IRAK2 variant was due to increased TRAF6 ubiquitination and faster IκBα degradation. Our study provides important insight of IRAK2 SNP in the regulation of NF-κB activation and indicates that IRAK2 rs708035 might be associated with human diseases caused by hyper-activation of NF-κB.

Introduction

The transcription factor NF-κB is a critical regulator of diverse cytokine-mediated cellular processes and plays a central role in the regulation of inflammation and immune responses (1–5). In quiescent cells, NF-κB proteins are retained in the cytoplasm because they are sequestered by the inhibitor protein IκBα. Upon activation of Toll-like receptors (TLRs),4 which are responsible for the recognition of pathogenic microorganisms, interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor, IκBα proteins are phosphorylated by the IκB kinase (IKK) complex and then degraded by the ubiquitin-protesome system, which allows translocation of NF-κB proteins from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and triggers expression of NF-κB target genes (3, 6, 7). Activation of NF-κB induces expression of various genes involved in immune responses, proliferation, and survival, such as IL-6 and IL-8. Thus, excessive activation of NF-κB usually leads to uncontrolled inflammation, immune responses, or proliferation, which increases the risk of severe infection, autoimmune disease, and even cancer (8–10).

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases (IRAKs) were originally described as transducers for inducing various inflammatory cytokines and later implicated as critical mediators in regulation of TLR/IL-1R signaling (11–15). Until now, four different IRAKs (IRAK1, IRAK2, IRAKM, and IRAK4) have been identified in mammals (13, 14, 16–18). Human IRAK1, IRAK2, and IRAK4 are ubiquitously expressed, whereas IRAKM is only detectable in monocytes and macrophages in an inducible manner (18). All of the IRAK proteins are required for TLR/IL-1-mediated NF-κB activation except IRAKM, which seems to function as a negative regulator through inhibiting IRAK1 dissociation from the receptor complex or through mediating production of inhibitory molecules as a negative feedback for the pathway (15, 19). For IL-1/TLR-induced NF-κB activation, binding of IL-1 or TLR ligands to the responsive receptors results in recruitment of TIR adaptors, such as MyD88, to the plasma membrane. Then, IRAK4 binds to MyD88 through its death domain and phosphorylates both IRAK1 and IRAK2. Phosphorylated IRAK1 and IRAK2 are then disassociated from the receptor complex and interact with TRAF6 in cytoplasm (20). After polyubiquitination mediated by IRAK2, TRAF6 binds to the TAK-1·TAB2 complex and activates TAK-1, leading to the subsequent activation of the IKK complex, degradation of IκBα, and finally translocation of NF-κB dimers from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (21–23).

Like other IRAK family proteins, IRAK2 contains an N-terminal death domain, a central kinase domain, and a C-terminal domain. Although the function of IRAK1 has been extensively studied, the exact contribution of IRAK2 has remained elusive for many years since its discovery. Knockdown of IRAK2 by siRNA in human cells showed that IRAK2 participates in NF-κB activation in response to IL-1 and ligands of multiple TLRs, including TLR3, TLR4, and TLR8 (24–26). Results from IRAK2 knock-out mice showed that IRAK1 and IRAK2 acted redundantly at early time points after TLR stimulation, whereas IRAK2 was critical for sustaining the responses at later time points (27). Recently, Lin et al. (28) reported a crystal structure of the death domain complex of human MyD88, IRAK2, and IRAK4, they found that IRAK2 plays an important role as a scaffold protein. Notably, Keating et al. (24) found that IRAK2 plays a more central role than IRAK1 for activating NF-κB in TLR signaling, because expression of IRAK2, but not IRAK1, led to TRAF6 ubiquitination, which is the key event for NF-κB activation. Moreover, IRAK2 mutants, which could not activate NF-κB, were incapable of promoting TRAF6 ubiquitination (24). Studies from Pauls et al. (29) further confirmed that the IRAK2-TRAF6 interaction is necessary to sustain IKKβ activity during prolonged activation of MyD88 signaling using a knock-in mouse model. Except for its crucial roles in TLR signaling, IRAK2 was also reported to be a critical mediator of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling (30).

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within the IRAK genes have been discovered recently (31). However, the functions of these IRAK SNPs remain largely unknown except for the the facts found by Ishida et al. and Arcaroli et al. (32, 33), respectively. In their studies, they demonstrated that a commonly occurring IRAK1 variant haplotype containing S196F and L532S is associated with increased activation of NF-κB, sepsis-induced acute lung injury, more severe organ dysfunction, and higher mortality. Nevertheless, there is little information about the function of the known IRAK2 genetic variants so far. In this study, we identified a reported non-synonymous IRAK2 variant, rs708035 (coding D431E), and demonstrated that this IRAK2 genetic variant leads to higher NF-κB transcriptional activity and more expression of NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory cytokines compared with IRAK2 wild type. Moreover, when we infected cells with influenza virus after knocking down endogenous IRAK2 and expression of siRNA-resistant IRAK2, more obvious induction of IL-6 and a stronger anti-apoptosis effect were observed in D431E-IRAK2 expressing cells. Moreover, when IRAK2 knockdown cells reconstituted with siRNA-resistant WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2 were infected with influenza virus, a more obvious induction of IL-6 and a stronger anti-apoptosis effect were observed in D431E-IRAK2 expressing cells. Notably, we also found that the levels of proinflammatory cytokine-IL-6 were indeed higher in people with D431E-IRAK2 than those with WT-IRAK2. Additionally, we showed that elevated NF-κB activation mediated by D431E-IRAK2 was due to increased TRAF6 ubiquitination and faster IκBα degradation. These studies indicated that D431E-IRAK2 might be associated with deregulation of inflammation and immune responses caused by hyperactivation of NF-κB in humans.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

HEK-293 cells and A549 cells were maintained in our laboratory. HEK-293 cells stably transfected with TLR3 (TLR3-HEK-293) were provided by the National Centre of Biomedical Analysis. All cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Plasmid Construction

pcDNA3-WT-IRAK2 expressing full-length IRAK2 was kindly provided by Dr. Andrew G. Bowie (School of Biochemistry and Immunology, Dublin, Ireland) (24). To generate a construct that encodes D431E-IRAK2, site-directed mutagenesis was performed by using pcDNA3-WT-IRAK2 as a template. The specific primers for site-directed mutagenesis were as follows: forward, 5′-CTT ACT CCT CAG TGA AAT TCC AAG CAG CAC C-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGT GCT GCT TGG AAT TTC ACT GAG GAG TAA G-3′. The nucleotide substitution corresponding to the change of amino acid at 431 from aspartic acid (Asp) to glutamic acid (Glu) is shown in bold and underlined. The resulting construct was designated pcDNA3-D431E-IRAK2. To generate siRNA-resistant constructs, respectively, encoding WT-IRAK2 and D431E-IRAK2, synonymous mutations were performed in the IRAK2 siRNA target sequence in pcDNA3-WT-IRAK2 and pcDNA3-D431E-IRAK2. The specific primers for synonymous mutations were as follows: forward, 5′-GAG ATC ATC CAC AGC TAC CTC TCG TGC TCT AAT GTC TTG C-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCA AGA CAT TAG AGC ACG AGA GGT AGC TGT GGA TGA TCT C-3′. The resulting constructs were designated as pcDNA3-res-WT-IRAK2 and pcDNA3-res-D431E-IRAK2, respectively. The TRAF6 expression plasmid FLAG-TRAF6 was kindly provided by the National Centre of Biomedical Analysis.

Immunoprecipitation, Immunoblotting, and Antibodies

For immunoprecipitation of ubiquitinated proteins, cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 10 mm EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate) containing a mixture of protease inhibitors and then subjected to rotation at 4 °C for 6 h with M2 beads (Sigma) after preincubating with protein A/G-Sepharose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) to capture the target protein with the FLAG tag. The beads were washed three times with 1 ml of RIPA buffer, and immunoprecipitates were resuspended in 40 μl of 1× loading buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 100 mm DTT, 2% SDS, 0.1% bromphenol blue, 10% glycerol) and resolved by SDS-PAGE. Cells that were transfected with siRNA and expression constructs were washed twice with cold PBS. Then, cells were harvested and subjected to centrifugation, the pellet was lysed in 80 μl of lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mm sodium chloride, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1% Nonidet P-40). After mixing with 80 μl 2× loading buffer, lysate (20 μl) was resolved by SDS-PAGE. Anti-Myc (sc-40), anti-IRAK1 (sc-5288), anti-IκB-α (sc-371), anti-TRAF6 (sc-7221), and anti-β-actin (sc-47778) were purchased from Santa Cruz. FLAG (M2) (F3165) monoclonal antibody was from Sigma. Antibody to IRAK2 (4367S) was purchased from Cell signaling. Human recombinant IL-1β was purchased from Sigma. TLR3 agonist poly(I:C) was purchased from Invitrogen.

Reporter Gene Assays

NF-κB activation, IL-6, and IL-8 promoter induction were measured by a reporter gene assay. HEK-293, TLR3-HEK-293, HCT116, or HeLa cells were co-transfected with 200 ng of luciferase reporter gene constructs and a different dose of expression constructs using Lipofectamine 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen). For all assays, 20 ng of the TK-Renilla construct per transfection was included to normalize transfection efficiency. At 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β or 50 μg/ml of poly(I:C) for 6 h before harvest, and luciferase activity was measured. For detecting of p38 activity, the Gal4-UAS system was used. HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with 100 ng of hMEF-2AG-Gal4 fusion protein expression construct, 100 ng of 5× UAS-luciferase reporter gene construct, and 100 ng of expression constructs, respectively, encoding WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2. The reporter gene assay was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega). All transfections were done in triplicate, and data were expressed as fold-induction (means ± S.D.) relative to control levels for a representative experiment of a minimum of three separate experiments.

RNA Quantification

Total RNA was purified with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions. Real-time quantitative PCR analysis was performed using the LightCycler (Roche Applied Science) and SYBR RT-PCR kits (Takara). The primers used to amplify transcripts of human IL-6, IL-8, IFN-α, and IFN-β were as follows: IL-6, forward, 5′-CAC CTC TTC AGA ACG AAT TGA CAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GCA CCG GGC CCT TCA-3′; IL-8, forward, 5′-GTG CAG TTT TGC CAA GGA GT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CTC TGC ACC CAG TTT TCC TT-3′; IFN-α, forward, 5′-GTG AGG AAA TAC TTC CAA AGA ATC AC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCT CAT GAT TTC TGC TCT GAC AA-3′; IFN-β, forward, 5′-CCG AGC AGA GAT CTT CAG GAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCT GCA ACC ACC ACT CAT TCT-3′; and IκBα, forward, 5′-CCC TGT AAT GGC CGG ACT G-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAG CAT CTG AAG GTT TTC TAG TG-3′. Human GAPDH transcript was used as an internal control. The primers for GAPDH were as follows: 5′-GCG AGA TCC CTC CAA AAT CAA-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTT CAC ACC CAT GAC GAA CAT-3′.

RNA Interference

IRAK2-specific siRNA duplexes were targeted at the following sites: IRAK2-siRNA #1, 5′-CCA GGA TCA ATC GAA AGA TTT-3′; IRAK2-siRNA #2, 5′-GCA ACG TCA AGA GCT CTA ATT-3′; IRAK2-siRNA #3, 5′-GTG GCA AAT TGA GAT CAA TTT-3′. Non-silencing siRNA was used as a control. To confirm the knockdown effect of endogenous IRAK2 expression, HEK-293 cells were transfected with siRNA duplexes at a final concentration of 50 nm using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). Cell lysates and total RNA were prepared and analyzed by immunoblotting and real-time qPCR at 48 h after transfection. For reporter gene assays, HEK-293 or TLR3-HEK-293 cells in 24-well plates were transfected with siRNA duplexes and then co-transfected with reporter constructs 24 h later. For rescue of exogenous IRAK2 into cells treated with IRAK2 siRNA, HEK-293 or TLR3-HEK-293 cells in 12-well plates were transfected with siRNA duplexes and then co-transfected with reporter and siRNA-resistant IRAK2 expression constructs 24 h later. For IAV infection experiments, A549 cells in 12-well plates were infected with IAV at 24 h after transfection with siRNA duplexes and siRNA-resistant IRAK2 expression constructs.

In Vitro Stimulation of PBMCs

PBMCs were isolated from the blood of healthy donors via density gradient centrifugation. 106 freshly isolated PBMCs were subsequently incubated for 24 h with poly(I:C) at 20 μg/ml or left unstimulated. IL-6 production in cell supernatants was assayed by ELISA (ExCell Biology, Inc.). The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples.

Virus and Viral Infection

Human H1N1 IAV strain A/FM/1/47 was kindly provided by Prof. Xia (Institute of Veterinary Sciences). A549 cells were seeded into 12-well plates and then transfected as described above. After 24 h, viral infection was performed. After a 1-h incubation, the supernatants were removed, and the cells were washed three times with PBS and then overlaid with RPMI 1640 with l-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone-trypsin at a final concentration of 1 μg/ml for the indicated time. Then, cells were harvested for reporter gene assay, real-time qPCR, and measurement of cell apoptosis, the supernatants were harvested for detection of IL-6 levels by ELISA (ExCell Biology, Inc.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For apoptosis detection, A549 cells infected with influenza A virus (IAV) for the indicated time were analyzed using an Annexin V-FITC/PI binding assay kit (KeyGEN Biotech). Cells were subjected to flow cytometric analysis on a FACS Calibur, and data were analyzed with CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

RESULTS

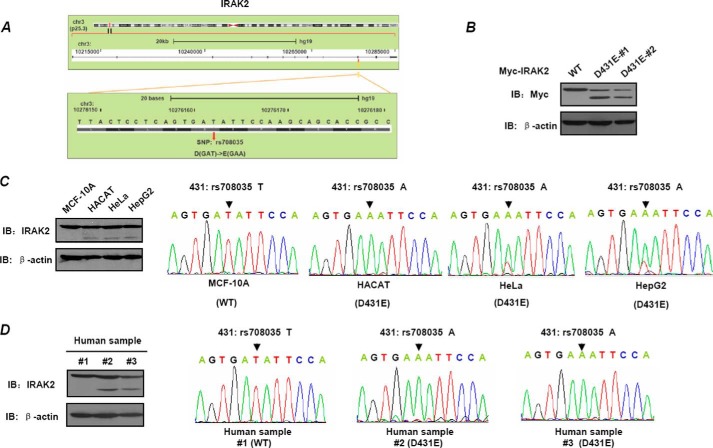

Construction and Expression of the IRAK2 Wild Type and Its D431E Genetic Variant

Based on results of public databases, we found an exonic SNP in the human IRAK2 gene. The genetic variant of IRAK2(rs708035) contains alteration of the DNA base from T to A and amino acid change from Asp to Glu at position 431 (Fig. 1A). According to findings published by the 1000 Genomes Project Consortium (43), the allele frequencies for SNP rs708035 vary in different human populations. The ancestral (A) allele, reported in chimpanzees, is the most frequent in Asian populations (99%), but less frequent in other populations (African population: 77%; American population: 78%; and European population: 65%). In this study, this SNP of IRAK2 mentioned above is named as D431E-IRAK2. Until now, there is little information and indication of this IRAK2 genetic variant being linked to any human disease susceptibility. To further explore whether the IRAK2 genetic variant alters its function, we generated constructs encoding WT- and D431E-IRAK2, respectively, which are designated pcDNA3-WT-IRAK2 and pcDNA3-D431E-IRAK2, the C terminals are fused with Myc6 tag. HEK-293T cells were transiently transfected with the two constructs, and IRAK2 expression was detected by Western blotting using anti-Myc antibody. Interestingly, we found that WT-IRAK2 was detected as a single band, whereas D431E-IRAK2 was detected with an additional band at about 60 kDa, except for the band at about 80 kDa, which is equal to the molecular mass of WT-IRAK2 (Fig. 1B). To examine whether a similar difference also occurred in endogenous IRAK2, we first extracted genomic DNA and protein from four cell lines and three human blood samples. Genotypes of IRAK2 were determined by DNA sequencing and expression of endogenous IRAK2 was detected by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 1C, MCF-10A and HACAT were homozygous for the T (WT-IRAK2) and A alleles (D431E-IRAK2), respectively, whereas HeLa and HepG2 were heterozygous (Fig. 1C, right panels). For the three human blood samples, two were homozygous for D431E-IRAK2, and the other was homozygous for WT-IRAK2 (Fig. 1D, right panels).

FIGURE 1.

Construction and expression of wild type-IRAK2 and its D431E genetic variant. A, one SNP of the IRAK2 gene in its coding sequence leads to the amino acid change at the 431 site from Asp to Glu. B, HEK-293 cells were transfected with Myc-WT-IRAK2 or Myc-D431E-IRAK2. At 24 h after transfection, cell extracts were prepared and immunoblotting (IB) assays were performed to detect exogenous IRAK2 using anti-Myc antibody. C and D, total genomic DNA from four cell lines (C) and three human samples (D) was extracted and used as template to amplify the fragment containing the SNP position described above by PCR. Then, the amplified fragments were sequenced to determine the SNP (right panels). Cell lysis from these samples was prepared, and immunoblotting assays were performed to detect endogenous IRAK2 (left panels).

In accord with their genotypes, endogenous IRAK2 protein from samples carrying homozygous WT-IRAK2 was detected as one band, whereas those from D431E-IRAK2 carriers developed two bands (Fig. 1, C, left panel, and D, left panels). To exclude the possibility that the smaller band was caused by nonspecific recognition of the IRAK2 antibody, we immunoprecipitated D431E-IRAK2 with the Myc antibody and then analyzed the smaller bands of D431E-IRAK2 with mass spectrometry. Mass spectrometry analysis identified that this band was indeed IRAK2. To further explore the detailed mechanism leading to formation of the D431E-IRAK2 lower band, we first analyzed whether phosphatase treatment could cause WT-IRAK2 to run at the same level as D431E. Phosphatase treatment does not cause the WT-IRAK2 to run at the same level as D431E-IRAK2. However, in the same assay, we detected obvious dephosphorylation of CUEDC2 as previously reported (34). These results indicated that the lower band of D431E-IRAK2 was not caused by dephosphorylation. Given the results, it is very likely that the lower band was a cleaved form of IRAK2. Now, we are screening the IRAK2 sequence for cleavage site of the known proteases, and found no substrate characteristics of the known caspase family in the IRAK2 sequence. Whether there was any cleavage site of other the protease is still under investigation.

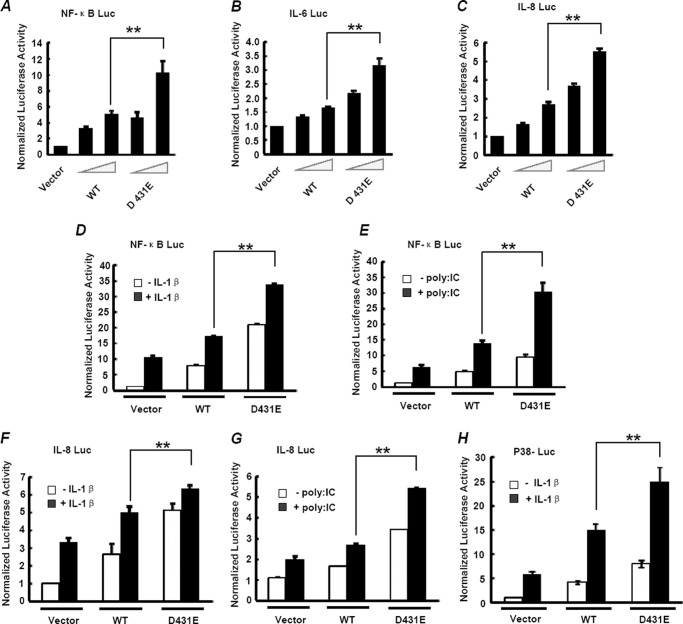

Overexpression of the IRAK2 Variant D431E Leads to Increased NF-κB Activation

Because the 431 site was located within the kinase domain of IRAK2, it is possible that the change of amino acid at this site lead to alteration of the IRAK2 function. Considering the key roles of IRAK2 in NF-κB activation, we first investigated the ability of D431E-IRAK2 to mediate NF-κB activation using a luciferase reporter assay. Transcription of this reporter gene was driven by a IκBα promoter and is solely dependent on NF-κB activity. As shown in Fig. 2A, overexpression of IRAK2, both WT and D431E, could induce a substantial transcription of the reporter gene in a dose-dependent manner. However, compared with wild type-IRAK2, D431E-IRAK2 mediated stronger NF-κB activation with an even less protein expression. Similar results were also obtained in HCT116 and HeLa cells. These results suggest that D431E-IRAK2 leads to increased NF-κB activation. To further confirm the effect of D431E-IRAK2 on NF-κB activation, we detected the induction of IL-6 and IL-8, the two well defined NF-κB-targeted genes, by luciferase reporter assays. Consistent with the above results, D431E-IRAK2 was more potent in triggering IL-6 and IL-8 expression than WT-IRAK2 (Fig. 2, B and C).

FIGURE 2.

Overexpression of D431E-IRAK2 leads to increased NF-κB activation. A, HEK-293 cells were co-transfected with 200 ng of NF-κB luciferase reporter gene constructs (containing the IκB-α promoter), 20 ng of TK-Renilla construct to normalize data for transfection efficiency, and increasing amounts of Myc-WT-IRAK2 (0, 10, and 50 ng) or Myc-D431E-IRAK2 (0, 10, and 50 ng) as indicated. NF-κB activation was measured by a luciferase reporter assay at 24 h after transfection. B and C, HEK-293 cells were transfected the same as in A, IL-6 (B), and IL-8 (C) induction was measured by reporter gene assays. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of at least three experiments. D, HEK-293 cells were transfected with 200 ng of NF-κB luciferase reporter gene constructs, 20 ng of TK-Renilla, and 100 ng of Myc-WT-IRAK2 or Myc-D431E-IRAK2. 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β for 6 h and NF-κB activation was detected. E, TLR3-HEK-293 cells were transfected with the indicated vectors as in D, 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with 50 μg/ml of poly(I:C) for 6 h, and NF-κB activation was measured by reporter gene assay. F and G, HEK-293 and TLR3-HEK-293 cells were transfected as in D and E except that the NF-κB luciferase reporter gene was replaced by a gene containing the IL-8 promoter. 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β (F) or 50 μg/ml of poly(I:C) (G) for 6 h, and IL-8 induction was measured. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of at least three experiments. H, HEK-293 cells were transfected with 100 ng of hMEF-2AG-Gal4 fusion protein expression construct, 100 ng of 5×UAS-luciferase reporter gene construct, and 100 ng of Myc-WT-IRAK2 or Myc-D431E-IRAK2. 24 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β for 6 h and p38 activation was measured by a reporter gene assay. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of at least three experiments. **, p < 0.01.

Previous studies have shown that IRAK2 plays an important role in IL-1/TLR-induced NF-κB activation and was first discovered as a mediator of IL-1 signaling (13). Moreover, knockdown of human IRAK2 expression by siRNA impaired NF-κB activation induced by several TLRs. We next determined the effects of the two forms of IRAK2 on IL-1 and TLR3-induced NF-κB activation. Two luciferase reporter genes based on IκBα and the IL-8 promoter, respectively, were used to examine NF-κB activity in HEK-293 cells with or without IL-1β or poly(I:C) stimulation. As previously found, overexpression of either WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2 could lead to NF-κB-dependent transcription of the reporter gene, and the latter are more efficient. When the transfected HEK-293 cells were treated with IL-1β, transcription of the reporter gene was further induced. D431E-IRAK2 transfection led to a higher IL-1β-induced expression of reporter genes compared with WT-IRAK2 transfection (Fig. 2D). The above results were not due to the expression level of IRAK2 because it was obvious that the expression level of WT-IRAK2 was no less than that of D431E with or without IL-1β stimulation. Then, we performed a reporter assay to examine poly(I:C)-induced NF-κB activation and similar results were obtained (Fig. 2E). The effect of D431E-IRAK2 was further confirmed by the results of reporter gene assays based on the IL-8 promoter (Fig. 2, F and G). Because p38 is also an important downstream signaling molecule of the IRAK2 complex in IL-1/TLR signaling, we next detected p38 activation by the luciferase reporter assay. As shown in Fig. 2H, D431E-IRAK2 not only promotes NF-κB activation, but also leads to increased p38 activation compared with the WT-IRAK2. These results indicate that D431E-IRAK2 is more efficient than WT-IRAK2 to activate IRAK2 downstream signaling.

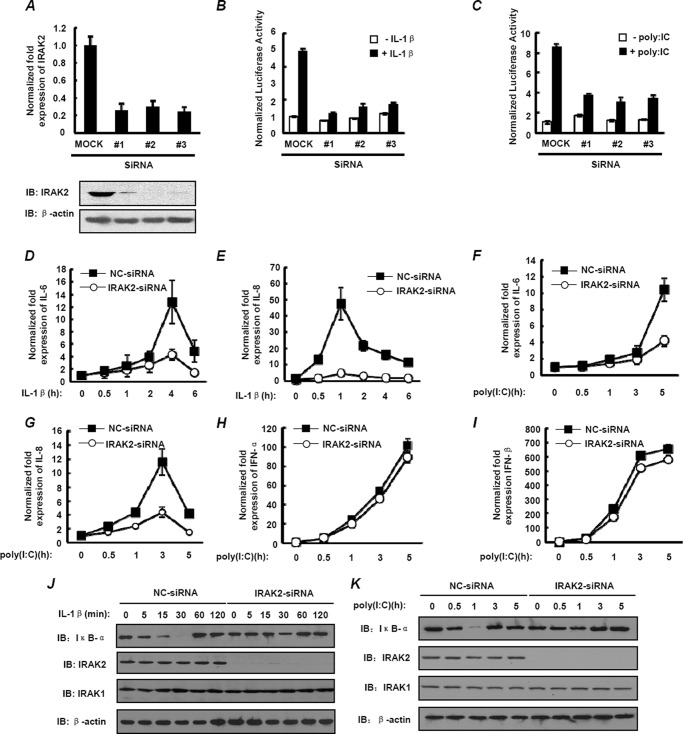

Expression of IRAK2 Genetic Variant at Endogenous Level Induces Stronger NF-κB Activation

To rule out the possibility that the increased NF-κB activation resulting from D431E-IRAK2 was caused by interference of the endogenous IRAK2, siRNAs were used to knockdown endogenous IRAK2 expression, and then NF-κB activation was determined after transfecting siRNA-resistant plasmids expressing WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2 at a physiological level in cells. The knockdown efficiency of the three siRNA oligonucleotides that target IRAK2 in HEK-293 cells was detected by examining the IRAK2 mRNA and protein levels. As shown in Fig. 3A, mRNA and protein levels of endogenous IRAK2 were obviously reduced in the presence of IRAK2 siRNA compared with cells treated with the scramble siRNA. Importantly, knockdown of IRAK2 obviously decreased expression of the NF-κB reporter gene induced by IL-1β and poly(I:C) (Fig. 3, B and C). To further confirm the role of IRAK2 in IL-1β and poly(I:C)-induced NF-κB activation, we examined IL-6 and IL-8 expression using real time quantitative PCR in cells with or without IRAK2 knockdown. Time courses of IL-1β-induced IL-6 and IL-8 transcription in HEK-293 cells showed the kinetic mRNA levels of IL-6 and IL-8. When cells were treated with IRAK2 siRNA, the levels of IL-1β-stimulated IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA decreased significantly (Fig. 3, D and E). Similarly, down-regulation of IRAK2 also led to a significant suppression of poly(I:C)-induced IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA expression (Fig. 3, F and G). However, little change of IFN-α and IFN-β mRNA levels was observed in cells with IRAK2 knockdown (Fig. 3, H and I), in keeping with the findings of Keating et al. (24) that IRAK2 seems unlikely to be involved in TLR-mediated IRF activation.

FIGURE 3.

Knocking down IRAK2 significantly prohibits NF-κB activation. A, HEK-293 cells were transfected with either control non-silencing siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA (#1, 2, and 3). Total RNA were prepared for examining the IRAK2 mRNA level by real-time qPCR (upper panel), and cell lysates were assayed for endogenous IRAK2 expression by immunoblotting with anti-IRAK2 antibody (lower panel). B and C, HEK-293 (B) and TLR3-HEK-293 (C) cells were transfected with either control non-targeting siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA (#1, 2, and 3), then stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β (B) or 50 μg/ml of poly(I:C) (C) for 6 h, respectively. NF-κB activation was measured by a reporter gene assay. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of three experiments. D and E, HEK-293 cells were transfected with either control non-silencing siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA (#2). Then, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β as indicated. Total RNA was prepared using IL-6 (D) and IL-8 (E) mRNA levels at the indicated time points by real-time qPCR. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of three experiments. F–I, TLR3-HEK-293 cells were transfected with either control non-silencing siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA (#2). Then, cells were stimulated with 50 μg/ml of poly(I:C) for 0.5, 1, 3, or 5 h. Total RNA was prepared for IL-6 (F), IL-8 (G), IFN-α (H), and IFN-β (I) for mRNA expression by real-time qPCR. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of three experiments. J and K, HEK-293 (J) and TLR3-HEK-293 (K) cells were transfected as described above, and cells were stimulated, respectively, with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β for the indicated time points or 50 μg/ml of poly(I:C) for 0.5, 1, 3, or 5 h. Cell lysates were assayed for IκBα expression by immunoblotting. β-Actin was detected as loading control. IB, immunoblot.

As known, IκB-α prevents NF-κB dimers p65/p50 from translocating into the nucleus by non-covalent interaction when cells are in resting state. Once the IL-1/TLR signaling is activated, IκBα will undergo phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation. We next determined the kinetics of IκBα degradation in cells transfected with control or IRAK2 siRNA. Treatment of HEK-293 with IL-1β led to degradation of IκB-α within 5 min and IκBα was barely detectable at 30 min after IL-1β stimulation. When cells were pretreated with IRAK2 siRNA, IL-1β-induced degradation of IκBα was significantly prevented compared with cells treated by control siRNA (Fig. 3J). We also found that knockdown of IRAK2 impaired poly(I:C)-induced IκBα degradation, which appears within 0.5 h after treatment in control cells (Fig. 3K). These results suggest that IRAK2 is indeed required for IL-1/TLR3-mediated NF-κB activation.

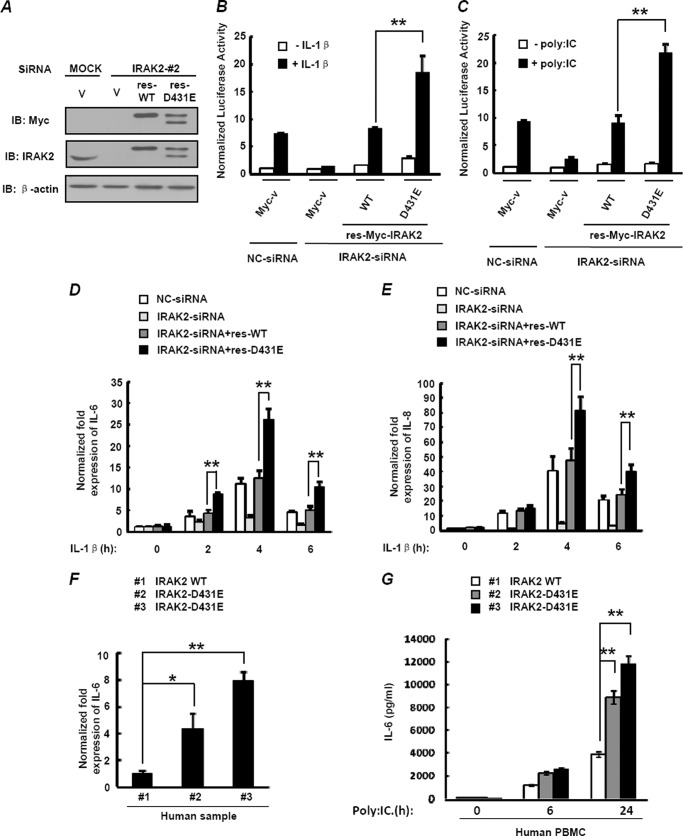

To obtain more direct evidence for the effects of D431E-IRAK2 on IL-1/TLR3-induced NF-κB activation, we generated siRNA-resistant constructs, respectively, encoding WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2 with synonymous mutations in the IRAK2 siRNA target sequence and transfected them into IRAK2 knockdown cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, IRAK2 siRNA, which was effective in knockdown of endogenous IRAK2, had no effect on expressions of res-WT-IRAK2 and res-D431E-IRAK2. Next we examined the IL-1β- and poly(I:C)-induced NF-κB activation in IRAK2 knockdown cells expressing res-WT-IRAK2 and res-D431E-IRAK2 at equivalent levels. The reporter gene assay showed that HEK-293 cells pretreated with IRAK2 siRNA barely responded to IL-1β stimulation. Reintroduction of res-WT-IRAK2 and res-D431E-IRAK2 at the endogenous IRAK2 level restored cell responses to IL-1β stimulation. Moreover, res-D431E-IRAK2 was significantly more potent than res-WT-IRAK2 in mediating IL-1β-stimulated reporter gene expression (Fig. 4B). Similar results were obtained when poly(I:C)-induced NF-κB activation was examined (Fig. 4C). Then, we analyzed the dynamic expression of IL-1β-induced IL-6 and IL-8 in IRAK2 knockdown cells reconstituted with res-IRAK2. The results showed that more IL-6 and IL-8 mRNA were induced after IL-1β stimulation in cells expressing res-D431E-IRAK2 than those expressing res-WT-IRAK2 (Fig. 4, D and E). To further confirm that IRAK2 variant rs708035 could increase NF-κB activity and subsequent IL-6 secretion, we detected IL-6 mRNA levels of white blood cells from the same three human samples as in Fig. 1D. Consistently, the samples carrying D431E-IRAK2 showed a higher level of IL-6 than those carrying WT-IRAK2 (Fig. 4F). Notably, similar results were obtained when we purified the PBMCs from the three samples and detected the IL-6 concentration in the cell culture supernatant after poly(I:C) stimulation (Fig. 4G). Taken together, these results indicate that endogenous D431E-IRAK2 mediates stronger NF-κB activation.

FIGURE 4.

Expression of D431E-IRAK2 at the endogenous level induces stronger NF-κB activation. A, HEK-293 cells were transfected with either control siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA and siRNA-resistant plasmids res-WT-IRAK2 or res D431E-IRAK2. 48 h after transfection, cell lysates were assayed for exogenous or endogenous IRAK2 expression by immunoblotting (IB). B, HEK-293 cells transfected with the NF-κB luciferase reporter gene and other siRNA or expression vectors as in A were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β for 6 h. NF-κB activation was measured by a reporter gene assay. C, TLR3-HEK-293 cells were transfected the same as in B, and cells were stimulated with 50 μg/ml of poly(I:C) for 6 h. NF-κB activation was measured by a reporter gene assay. Data are fold-induction (mean ± S.D. of triplicates) relative to control levels and are representative of a minimum of three independent experiments. D and E, HEK-293 cells were transfected with either control siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA and siRNA-resistant plasmids of res-WT-IRAK2 or res-D431E-IRAK2. 48 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β for 2, 4, or 6 h, IL-6 (D) and IL-8 (E) mRNA levels were measured by real-time qPCR. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples and are representative of three experiments. F, total RNA from three human blood samples in Fig. 1D was extracted, and IL-6 mRNA levels were measured by real-time qPCR. G, human PBMCs were isolated from the same samples in F, one homozygous carrier of the T allele (WT-IRAK2) and two homozygous carriers of the A allele (D431E-IRAK2). Then PBMCs were incubated with poly(I:C) at 20 μg/ml or left unstimulated, and cell supernatants were harvested at the indicated time points for detecting IL-6 production by ELISA. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01.

IRAK2 Variant D431E Causes More IL-6 Secretion and Stronger Anti-apoptosis Effects in Cells Infected with Influenza Virus

As a pattern recognition receptor, TLR3 recognizes double-stranded RNA produced by RNA virus that infects the host cells, and subsequently triggers host cellular resistance to viral infection. Activation of TLR3 induces the production of proinflammatory cytokines and type I IFNs that play pivotal roles in antiviral innate and adaptive immune response through activation of NF-κB and interferon regulatory factor (35–37). Excessive production of proinflammatory cytokines may lead to the development of immunopathological conditions or immune disorders. In a previous study, we used poly(I:C) that can be recognized by TLR3 as an immunostimulant to examine the effects of the SNP on the physiological functions of IRAK2. Here, we wondered whether the same conclusions could also be drawn in the case of viral infection, because influenza virus is a kind of RNA viruses, which causes upper and lower respiratory tract infection through activating the TLR3-mediated NF-κB pathway as poly(I:C) stimulation (37, 38).

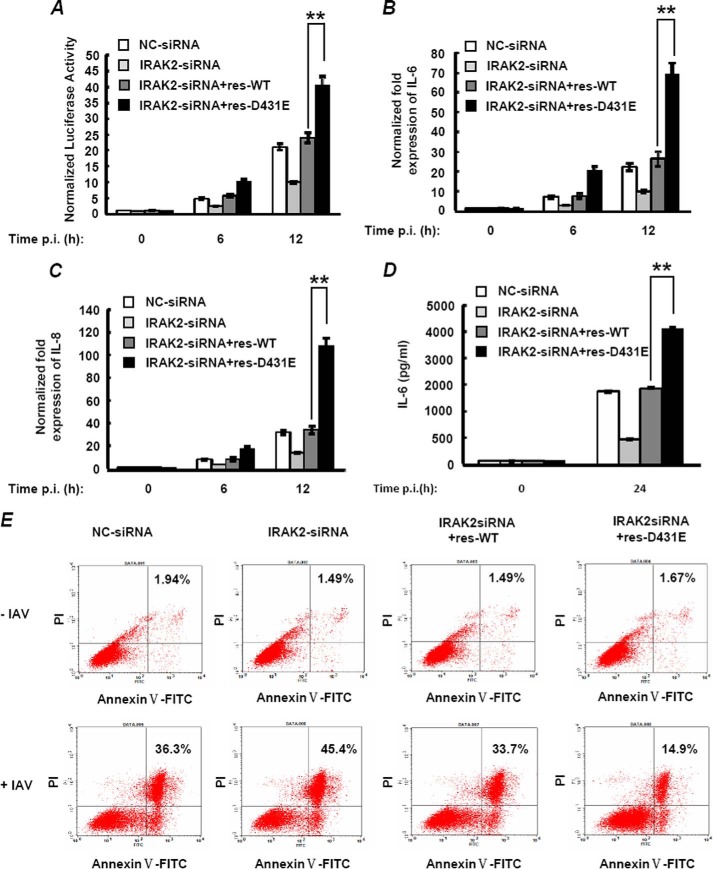

To further identify whether D431E-IRAK2 could also lead to increased NF-κB activation in response to influenza virus infection, we infected A549 cells with IAV, and NF-κB activation was investigated. As shown in Fig. 5, A-C, knockdown of IRAK2 by siRNA in A549 cells led to a substantial decrease on IAV-triggered NF-κB activation and IL-6 and IL-8 expression. Moreover, when res-WT-IRAK2 or res-D431E-IRAK2 were re-introduced into the cells, NF-κB activation and expression of IL-6 and IL-8 was restored. Consistent with the above result, res-D431E-IRAK2 was more efficient in mediating transcription of NF-κB target genes than res-WT-IRAK2. Similar results were also observed when secretion of IL-6 was detected by ELISA (Fig. 5D).

FIGURE 5.

D431E-IRAK2 causes more IL-6 secretion and stronger anti-apoptosis effects in cells infected with influenza virus. A, A549 cells were transfected with either control siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA and 500 ng of siRNA-resistant plasmids of res-WT-IRAK2 or res-D431E-IRAK2. Then, cells were infected with IAV (multiplicity of infection = 2) for another 6 or 12 h. NF-κB activation was measured by a reporter gene assay. B and C, A549 cells were transfected as in A and cells were infected with IAV (multiplicity of infection = 2) for 6 or 12 h. IL-6 (B) and IL-8 (C) mRNA levels were measured by real-time qPCR. D, A549 cells were transfected as above and cells were infected with IAV (multiplicity of infection = 2) for 24 h. IL-6 production in cell supernatants was assayed by ELISA. The data are mean ± S.D. of triplicate samples. E, A549 cells were transfected and treated as in D, cell apoptosis was measured by Annexin V-FITC/PI staining and flow cytometric analysis. **, p < 0.01.

Induction of apoptosis is a hallmark observed upon infection with many viral pathogens, including influenza A virus. As a target gene of the NF-κB transcriptional factor, IL-6 was found to be not only a proinflammatory factor, but also an important anti-apoptosis factor. Additionally, NF-κB activation can also induce expression of other anti-apoptotic proteins such as BCl-2, and IAP (inhibitor of apoptosis) family proteins to inhibit cell death caused by several apoptogenic agents (5, 39). We then investigated the effect of the IRAK2 variant on cell apoptosis triggered by influenza virus infection. To do so, we knocked down endogenous IRAK2 and transfected siRNA-resistant WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2 in A549 cells and detected apoptosis induced by influenza virus using an Annexin V-FITC assay. As shown in Fig. 5E, when A549 cells were pretreated with control siRNA, 36.3% of the cells underwent apoptosis 24 h after IAV infection, the percentage was increased when IRAK2 was knocked down (45.4%). As expected, expression of siRNA-resistant IRAK2 obviously restored the effect induced by IRAK2 knockdown. Moreover, the ability of res-D431E-IRAK2 to reduce the number of apoptotic cells was much stronger than that of res-WT-IRAK2, indicating a more efficient anti-apoptosis effect of the IRAK2 variant, which is consistent with its impact on NF-κB activation and IL-6 expression upon IVA infection.

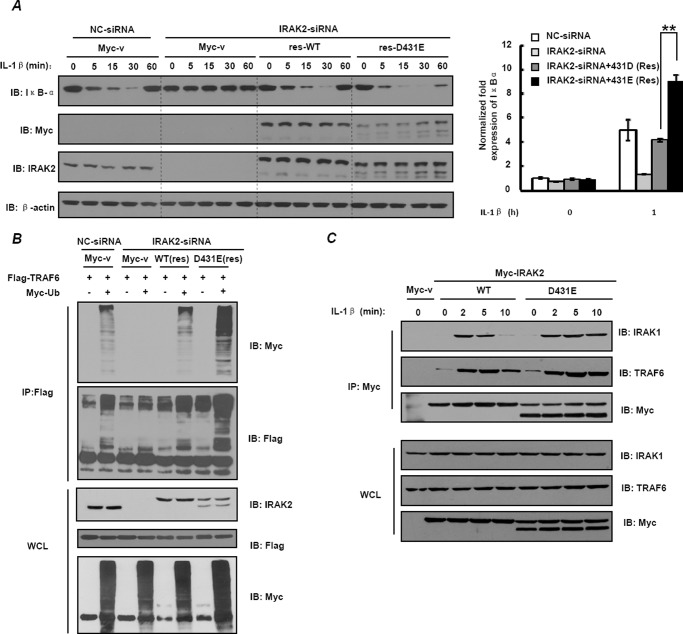

D431E-IRAK2 Promotes TRAF6 Ubiquitination

To examine the detailed mechanism by which D431E-IRAK2 induce higher NF-κB activity, we first detected IκBα degradation changes. As shown in Fig. 6A, knockdown of IRAK2 in HEK-293 cells resulted in a defect of IL-1β-induced IκBα degradation, and when res-WT or res-D431E-IRAK2 were expressed, IL-1β-induced IκBα degradation was restored. Notably, we observed that expression of res-D431E-IRAK2 led to more induction of the IκBα mRNA level (Fig. 6A, right panel) and more rapid degradation of the IκBα protein (Fig. 6A, left panel) than res-WT-IRAK2. These results suggest that D431E-IRAK2 leads to faster and stronger NF-κB activation.

FIGURE 6.

D431E-IRAK2 promotes TRAF6 ubiquitination. A, HEK-293 cells were transfected with either control siRNA (MOCK) or IRAK2-siRNA and 200 ng of siRNA-resistant plasmids of res-WT-IRAK2 or res-D431E-IRAK2. Then, cells were stimulated with 10 ng/ml of IL-1β for 5, 15, 30, or 60 min, and cell lysates were assayed for IκBα expression by immunoblotting (IB) (left panel). The mRNA level of IκBα is shown in the right panel. B, HEK-293 cells were transfected with siRNA or expression constructs as indicated. FLAG-TRAF6 was immunoprecipitated (IP) from cell lysates and levels of ubiquitinated TRAF6 were assessed by immunoblotting with anti-FLAG and anti-Myc antibody. The lower three panels show expression of IRAK2, FLAG-TRAF6, and Myc-ubiquitin in whole cell lysates (WCL). C, HEK-293 cells were transfected with expression constructs of WT-IRAK2 or D431E-IRAK2 (1 μg/well) as indicated. After stimulation with IL-1β, whole cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with anti-Myc monoclonal antibodies and immunoblotted as indicated.

As known, IκBα degradation upon IL-1/TLR stimulation was mediated by phosphorylation of the IKK complex, which was driven by TRAF6-dependent TAK1/TAB2 activation. Polyubiquitination of TRAF6 induced by IRAK-2 is critical for recruitment of the TAK-1·TAB2 complex and activation of TAK-1. To further determine the molecular mechanism of D431E-IRAK2 promoting NF-κB activation, we detected the levels of TRAF6 ubiquitination induced by WT- and D431E-IRAK2, respectively. As shown in Fig. 6B, knockdown of IRAK2 obviously impaired TRAF6 polyubiquitination. Re-introduction of res-WT-IRAK2 restored TRAF6 polyubiquitination. Notably, expression of res-D431E-IRAK2 induced significantly more TRAF6 polyubiquitination than that of res-WT-IRAK2.

As binding to IRAK2 is a prerequisite for TRAF6 to be polyubiquitinated, we next performed an immunoprecipitation assay to detect whether D431E-IRAK2 interacts with TRAF6 stronger than WT-IRAK2 in physiological conditions. As shown in Fig. 6C, WT-IRAK2 binds to TRAF6 at 2 min and disassociated at 10 min in response to IL-1β stimulation. However, when WT-IRAK2 was replaced with D431E-IRAK2, much more TRAF6 interacting with IRAK2 was observed. In addition, we also found that D431E-IRAK2 still associates with IRAK1 at 10 min after IL-1β stimulation, indicating that D432E-IRAK2 could recruit more IRAK1 to induce IRAK2 phosphorylation and thus enhance the IRAK2 and TRAF6 interaction (Fig. 6C). These results suggest that D431E-IRAK2 increases NF-κB activation by promoting TRAF6 ubiquitination by enhancing TRAF6-IRAK2 interaction.

DISCUSSION

It is generally believed that IRAK family proteins are pivotal modulators in IL-1/TLR signaling transduction. As a member of the IRAK family, more focus has been on the critical function of IRAK2 in inflammation and immune responses. Studies from Keating et al. (24) provided important insight into regulation of the IRAK2 on NF-κB activity. They reported that vaccinia virus protein A52, which is very important for virus virulence (40), inhibited TLR-induced NF-κB activation through interacting with IRAK2, but not IRAK1. Moreover, down-regulation of IRAK2 expression by siRNA in a human cell line obviously inhibited TLR3-, TLR4-, and TLR8-induced NF-κB-dependent gene expression (24). In keeping with these results, our data obtained from IRAK2 knockdown cells also showed obvious impairment of NF-κB-targeted gene expression and noticeable inhibition of IκBα degradation. Notably, the recent generation of IRAK2 knock-out mice was shown to be highly resistant to LPS- and CpG-induced septic shock, which was caused by uncontrolled NF-κB activation (27). However, it has been known that the difference in mortality between wild type and IRAK1−/− mice was very subtle (41). All of these studies indicate a predominant role of IRAK2 in TLR-induced NF-κB activation and immune responses, which seems to be distinct from the role of IRAK1, although these two proteins were considered to be functionally redundant previously.

SNPs are the most common type of genetic variation among humans. Some SNPs have been proven to be very important and may be associated with human diseases. SNPs that lead to amino acid alteration in the protein are of particular interest because they are responsible for nearly half of the known genetic variations related to human inherited diseases (42). Researchers have found that some SNPs could change the response of an individual to certain drugs, susceptibility to environmental factors, such as microbial, and risk of developing particular diseases. Thus, genetic heterogeneity involving the immune response to infection could lead to significant clinical consequences. As reported, SNPs within the IRAK genes occur frequently in the human population (27–29), whereas little is known about whether these genetic variants could lead to deregulation of the activity of IRAKs, especially for IRAK2. In the present study, we focused on a known SNP of IRAK2 at its 431 site and generated the IRAK2-D431E mutant using site-directed mutagenesis. Functional analysis showed that D431E-IRAK2 was associated with greater NF-κB activation and increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, upon influenza virus infection. Moreover, we demonstrated that increased NF-κB activation mediated by the IRAK2 variant resulted from faster degradation of IκB-α and increased TRAF6 ubiquitination. Our results indicated that D431E-IRAK2 might be critical for development of human diseases caused by deregulation of inflammation and immune responses that were associated with NF-κB hyperactivation.

Our present study indicated that the genetic alteration of IRAK2 affects its crucial function in IL-1 and TLR-induced NF-κB activation. In fact, this is the first report of the function of the known IRAK2 genetic variants. There are 12 non-synonymous SNPs within the coding sequence of the IRAK2 gene and seven are located in the kinase domain of this protein. We focused on two of these SNPs, which lead to the change of amino acid at the 392 and 431 sites of IRAK2 for further investigation due to their high reported frequency (>80%) in Chinese people. We found that D431E-IRAK2 is more active than WT IRAK2 in stimulating the NF-κB transcriptional activity, whereas C392G-IRAK2 does not have this effect (data not shown). Results from this work supported the hypothesis that enhanced NF-κB activation caused by D431E-IRAK2 might contribute to organ dysfunction in patients with severe infection. It is likely that alteration at the 431 site from Asp to Glu is critical for the ability of the IRAK2 variant to stimulate stronger NF-κB activation and presumably contribute to a greater inflammatory response. However, it is possible that other SNPs of IRAK2 are also important in modulating IRAK2 activity.

Thus, it may be worthwhile to investigate whether there are additional IRAK2 variants possessing different activities in mediating TLR/IL-1R-induced NF-κB activation. Furthermore, the detailed mechanism by which D431E-IRAK2 were detected as two bands and whether the smaller form of IRAK2 induces greater NF-κB activation also needs to be explored further.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Andrew G. Bowie, Dr. XianZhu Xia (Institute of Veterinary Sciences), and Dr. JiaHuai Han for kindly providing materials.

This work was supported by National Hi-tech Research and Development Program of China Grants 2012AA022002 and 2012AA02207, Chinese Key Program for Drug Invention Grant 2012ZX09J12106-03, and National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30800644, 31100940, 31271447, and 61308103.

- TLR

- Toll-like receptor

- IKK

- IκB kinase

- IRAK

- interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase

- SNP

- single nucleotide polymorphism

- qPCR

- quantitative PCR

- IAV

- influenza A virus.

REFERENCES

- 1. Li Q., Verma I. M. (2002) NF-κB regulation in the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2, 725–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ruland J., Mak T. W. (2003) Transducing signals from antigen receptors to nuclear factor κB. Immunol. Rev. 193, 93–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2008) Shared principles in NF-κB signaling. Cell 132, 344–362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bonizzi G., Karin M. (2004) The two NF-κB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 25, 280–288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hayden M. S., West A. P., Ghosh S. (2006) NF-κB and the immune response. Oncogene 25, 6758–6780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Karin M., Ben-Neriah Y. (2000) Phosphorylation meets ubiquitination: the control of NF-[κ]B activity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 18, 621–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hayden M. S., Ghosh S. (2004) Signaling to NF-κB. Genes Dev. 18, 2195–2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Böhrer H., Qiu F., Zimmermann T., Zhang Y., Jllmer T., Männel D., Böttiger B. W., Stern D. M., Waldherr R., Saeger H. D., Ziegler R., Bierhaus A., Martin E., Nawroth P. P. (1997) Role of NFκB in the mortality of sepsis. J. Clin. Investig. 100, 972–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mills K. H., Dunne A. (2009) Immune modulation: IL-1, master mediator or initiator of inflammation. Nat. Med. 15, 1363–1364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Karin M. (2006) Nuclear factor-κB in cancer development and progression. Nature 441, 431–436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Croston G. E., Cao Z., Goeddel D. V. (1995) NF-κ B activation by interleukin-1 (IL-1) requires an IL-1 receptor-associated protein kinase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 16514–16517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thomas J. A., Allen J. L., Tsen M., Dubnicoff T., Danao J., Liao X. C., Cao Z., Wasserman S. A. (1999) Impaired cytokine signaling in mice lacking the IL-1 receptor-associated kinase. J. Immunol. 163, 978–984 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Muzio M., Ni J., Feng P., Dixit V. M. (1997) IRAK (Pelle) family member IRAK-2 and MyD88 as proximal mediators of IL-1 signaling. Science 278, 1612–1615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Suzuki N., Suzuki S., Duncan G. S., Millar D. G., Wada T., Mirtsos C., Takada H., Wakeham A., Itie A., Li S., Penninger J. M., Wesche H., Ohashi P. S., Mak T. W., Yeh W. C. (2002) Severe impairment of interleukin-1 and Toll-like receptor signalling in mice lacking IRAK-4. Nature 416, 750–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kobayashi K., Hernandez L. D., Galán J. E., Janeway C. A., Jr., Medzhitov R., Flavell R. A. (2002) IRAK-M is a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell 110, 191–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Janssens S., Beyaert R. (2003) Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol. Cell 11, 293–302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wesche H., Gao X., Li X., Kirschning C. J., Stark G. R., Cao Z. (1999) IRAK-M is a novel member of the Pelle/interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 19403–19410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cao Z., Henzel W. J., Gao X. (1996) IRAK: a kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Science 271, 1128–1131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhou H., Yu M., Fukuda K., Im J., Yao P., Cui W., Bulek K., Zepp J., Wan Y., Kim T. W., Yin W., Ma V., Thomas J., Gu J., Wang J. A., DiCorleto P. E., Fox P. L., Qin J., Li X. (2013) IRAK-M mediates Toll-like receptor/IL-1R-induced NFκB activation and cytokine production. EMBO J. 32, 583–596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kollewe C., Mackensen A. C., Neumann D., Knop J., Cao P., Li S., Wesche H., Martin M. U. (2004) Sequential autophosphorylation steps in the interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-1 regulate its availability as an adapter in interleukin-1 signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5227–5236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Qian Y., Commane M., Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Matsumoto K., Li X. (2001) IRAK-mediated translocation of TRAF6 and TAB2 in the interleukin-1-induced activation of NFκB. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 41661–41667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takaesu G., Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Kishida S., Li X., Stark G. R., Matsumoto K. (2001) Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor-associated kinase leads to activation of TAK1 by inducing TAB2 translocation in the IL-1 signaling pathway. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2475–2484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Jiang Z., Ninomiya-Tsuji J., Qian Y., Matsumoto K., Li X. (2002) Interleukin-1 (IL-1) receptor-associated kinase-dependent IL-1-induced signaling complexes phosphorylate TAK1 and TAB2 at the plasma membrane and activate TAK1 in the cytosol. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7158–7167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Keating S. E., Maloney G. M., Moran E. M., Bowie A. G. (2007) IRAK-2 participates in multiple Toll-like receptor signaling pathways to NFκB via activation of TRAF6 ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 33435–33443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fitzgerald K. A., Palsson-McDermott E. M., Bowie A. G., Jefferies C. A., Mansell A. S., Brady G., Brint E., Dunne A., Gray P., Harte M. T., McMurray D., Smith D. E., Sims J. E., Bird T. A., O'Neill L. A. (2001) Mal (MyD88-adapter-like) is required for Toll-like receptor-4 signal transduction. Nature 413, 78–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yamamoto M., Sato S., Hemmi H., Sanjo H., Uematsu S., Kaisho T., Hoshino K., Takeuchi O., Kobayashi M., Fujita T., Takeda K., Akira S. (2002) Essential role for TIRAP in activation of the signalling cascade shared by TLR2 and TLR4. Nature 420, 324–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kawagoe T., Sato S., Matsushita K., Kato H., Matsui K., Kumagai Y., Saitoh T., Kawai T., Takeuchi O., Akira S. (2008) Sequential control of Toll-like receptor-dependent responses by IRAK1 and IRAK2. Nat. Immunol. 9, 684–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lin S. C., Lo Y. C., Wu H. (2010) Helical assembly in the MyD88-IRAK4-IRAK2 complex in TLR/IL-1R signalling. Nature 465, 885–890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pauls E., Nanda S. K., Smith H., Toth R., Arthur J. S., Cohen P. (2013) Two phases of inflammatory mediator production defined by the study of IRAK2 and IRAK1 knock-in mice. J. Immunol. 191, 2717–2730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Benosman S., Ravanan P., Correa R. G., Hou Y. C., Yu M., Gulen M. F., Li X., Thomas J., Cuddy M., Matsuzawa Y., Sano R., Diaz P., Matsuzawa S., Reed J. C. (2013) Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase-2 (IRAK2) is a critical mediator of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress signaling. PloS One 8, e64256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Greenman C., Stephens P., Smith R., Dalgliesh G. L., Hunter C., Bignell G., Davies H., Teague J., Butler A., Stevens C., Edkins S., O'Meara S., Vastrik I., Schmidt E. E., Avis T., Barthorpe S., Bhamra G., Buck G., Choudhury B., Clements J., Cole J., Dicks E., Forbes S., Gray K., Halliday K., Harrison R., Hills K., Hinton J., Jenkinson A., Jones D., Menzies A., Mironenko T., Perry J., Raine K., Richardson D., Shepherd R., Small A., Tofts C., Varian J., Webb T., West S., Widaa S., Yates A., Cahill D. P., Louis D. N., Goldstraw P., Nicholson A. G., Brasseur F., Looijenga L., Weber B. L., Chiew Y. E., DeFazio A., Greaves M. F., Green A. R., Campbell P., Birney E., Easton D. F., Chenevix-Trench G., Tan M. H., Khoo S. K., Teh B. T., Yuen S. T., Leung S. Y., Wooster R., Futreal P. A., Stratton M. R. (2007) Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature 446, 153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ishida R., Emi M., Ezura Y., Iwasaki H., Yoshida H., Suzuki T., Hosoi T., Inoue S., Shiraki M., Ito H., Orimo H. (2003) Association of a haplotype (196Phe/532Ser) in the interleukin-1-receptor-associated kinase (IRAK1) gene with low radial bone mineral density in two independent populations. J. Bone Miner. Res. 18, 419–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Arcaroli J., Silva E., Maloney J. P., He Q., Svetkauskaite D., Murphy J. R., Abraham E. (2006) Variant IRAK-1 haplotype is associated with increased nuclear factor-κB activation and worse outcomes in sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 173, 1335–1341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gao Y. F., Li T., Chang Y., Wang Y. B., Zhang W. N., Li W. H., He K., Mu R., Zhen C., Man J. H., Pan X., Li T., Chen L., Yu M., Liang B., Chen Y., Xia Q., Zhou T., Gong W. L., Li A. L., Li H. Y., Zhang X. M. (2011) Cdk1-phosphorylated CUEDC2 promotes spindle checkpoint inactivation and chromosomal instability. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 924–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Edelmann K. H., Richardson-Burns S., Alexopoulou L., Tyler K. L., Flavell R. A., Oldstone M. B. (2004) Does Toll-like receptor 3 play a biological role in virus infections? Virology 322, 231–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guillot L., Le Goffic R., Bloch S., Escriou N., Akira S., Chignard M., Si-Tahar M. (2005) Involvement of toll-like receptor 3 in the immune response of lung epithelial cells to double-stranded RNA and influenza A virus. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 5571–5580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Le Goffic R., Pothlichet J., Vitour D., Fujita T., Meurs E., Chignard M., Si-Tahar M. (2007) Cutting Edge: Influenza A virus activates TLR3-dependent inflammatory and RIG-I-dependent antiviral responses in human lung epithelial cells. J. Immunol. 178, 3368–3372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Izurieta H. S., Thompson W. W., Kramarz P., Shay D. K., Davis R. L., DeStefano F., Black S., Shinefield H., Fukuda K. (2000) Influenza and the rates of hospitalization for respiratory disease among infants and young children. New Engl. J. Med. 342, 232–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Perkins N. D. (2012) The diverse and complex roles of NF-κB subunits in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Harte M. T., Haga I. R., Maloney G., Gray P., Reading P. C., Bartlett N. W., Smith G. L., Bowie A., O'Neill L. A. (2003) The poxvirus protein A52R targets Toll-like receptor signaling complexes to suppress host defense. J. Exp. Med. 197, 343–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Swantek J. L., Tsen M. F., Cobb M. H., Thomas J. A. (2000) IL-1 receptor-associated kinase modulates host responsiveness to endotoxin. J. Immunol. 164, 4301–4306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Krawczak M., Ball E. V., Fenton I., Stenson P. D., Abeysinghe S., Thomas N., Cooper D. N. (2000) Human gene mutation database: a biomedical information and research resource. Hum. Mutat. 15, 45–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. 1000 Genomes Project Consortium (2012) An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 491, 56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]