Because appropriate clinical management is guided by the nature of the mass, accurate diagnosis of discrete hepatic masses is very important. Possible treatments range from supportive care for advanced metastatic lesions to partial hepatectomy for primary carcinomas. Despite recent improvement, radiological imaging does not always allow precise characterization of the lesions. Serological markers (such as alpha fetoprotein) can be useful in narrowing the differential diagnosis when they are markedly elevated but a substantial number of patients unfortunately do not have high levels of these markers at the time of presentation. Therefore, a tissue diagnosis is often required to guide subsequent management. Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) under image guidance has gained increasing acceptance as the diagnostic procedure of choice for patients with focal hepatic lesions. It can be performed percutaneously or endoscopically. This review will discuss fine needle aspiration biopsy of liver from a pathologist's perspective. The review will also address the cytology and the pitfalls of some of the more commonly encountered hepatic lesions as well as those that may pose diagnostic challenges.

Currently, there are several diagnostic procedures to obtain preoperative tissue diagnosis to guide subsequent therapy. They include image guided fine needle aspiration biopsy, blind percutaneous needle core biopsy, and transjugular needle core biopsy. Percutaneous needle core biopsy without imaging guidance is excellent for diagnosing diffuse liver diseases such as hepatitis, cirrhosis, and metabolic diseases. Accuracy is superb and the complication rate is low. However, it is not indicated for focal, discrete hepatic lesions. To minimize the risk of hemorrhage, transjugular approach is often reserved for patients with a bleeding diathesis. Fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNA) under image guidance has gained increasing acceptance as the diagnostic procedure of choice for patients with focal hepatic lesions. It can be performed percutaneously or endoscopically. The latter approach is technically difficult for lesions located far away from the tip of the echoenodoscope and lesion near the 2nd or 3rd portion of the duodenum because of poor visualization [1]. FNA may also be performed at laparoscopy or laparotomy under direct vision when imaged guided FNA fails to provide diagnostic tissue [2].

This review is not intended to be exhaustive. Therefore, the discussion is limited to the lesions that are more commonly encountered in day-to-day practice and those that may pose diagnostic challenges.

Operating characteristics of FNA

In experienced hands, FNA is safe, minimally invasive, accurate, and cost effective. The specificity of FNA biopsy of the liver approaches 100% and the sensitivity ranges from 67–100%, averaging about 85% [3-9]. FNA alone is superior to core biopsy alone because the needle is longer, can be guided, and the procedure can be easily repeated [10,11]. However, both methods are complimentary to each other [10,12,13].

Complications of FNA

The occurrence of complications after hepatic FNA is rare with about 0.5% minor complications, 0.05% major complications requiring surgery, and less than 0.01% mortality [14-17]. They are limited largely to hemorrhage. The frequency of complications is often related to the vascularity and the location of the lesions as well as the needle size [18]. Another concern is the subcutaneous seeding of tumor along the needle tract during precutaneous liver FNA. The incidence varies with the diameter of the needle, the number of passes, and the amount of normal parenchyma around the lesion to be traversed by the needle [7]. It is still an extremely rare complication. For example, there are only a few case reports of needle tract seeding when using needle of 23 gauge or less [19-21].

Contraindications of FNA

Absolute contraindications for FNA of liver include uncorrectable bleeding diathesis, a lack of a safe access route e.g. vascular structure in the biopsy path, and uncooperative patients.

Specimen preparation

It is crucial to handle the aspirate quickly and optimally in order to minimize artifacts. Ideally, both direct smears and cell block should be prepared for all FNA of livers. Cell block preparation is especially useful if immunohistochemical study is required for differential diagnosis. Direct smears are made by spreading a small volume of aspirated material on prelabeled slides which can be either air-dried or fixed in 95% ethanol. The air-dried smears are stained with a modified Giemsa stain. The alcohol-fixed smears are stained with the Papanicolaou method. A cell block is then prepared from residual materials rinsed from the needle.

Several studies have shown that the assistance of cytopathologists during the procedure increases overall accuracy [22-24]. The latter is attributed to the ability to assess specimen adequacy at the time of biopsy and to determine if additional tissue is required for diagnosis and/or ancillary studies such as flow cytometry.

Clinical and radiological correlation

Although clinical and/or radiological findings cannot reliably distinguish a primary hepatic malignancy from a metastatic disease, they can help to narrow the differential diagnosis. The age of the patient may suggest certain processes. For example, metastatic disease and primary hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) more frequently affect older patients whereas benign lesions such as liver cell adenoma and fibrolamellar variant of HCC tend to occur in younger patients. Hepatoblastoma occurs primarily in infants [25]. Patients with liver cell adenoma often have a history of long term steroid use.

Another informative clue is the presence or absence of cirrhosis. For patients with cirrhosis, HCC is a more likely finding in the United States [26]. However, 10–20% of nonfibrolamellar HCCs occur in patients without cirrhosis. Fibrolamellar HCC always occurs in noncirrhotic liver.

A markedly elevated serum AFP level, >1,000 ng/ml, is highly suggestive of HCC or in children, hepatoblastoma. A moderate increase in serum AFP, however, is non-specific and can be seen in a wide variety of benign and malignant conditions. Patients with fibrolamellar variant of HCC may not demonstrate an elevated serum AFP level.

The finding of a single, large mass with or without smaller satellite lesions on imaging is more typical of a HCC whereas metastatic lesions often present with multiple lesions of similar size.

Cytology of normal and reactive liver

Aspirates of normal liver consist predominantly of hepatocytes and scattered bile duct epithelial cells. Table 1 summarizes the cytologic features of these two types of cells. Other cell types such as endothelial cells and Kupffer's cells are infrequently noted. Occasionally, mesothelial cells and small bowel mucosa may be inadvertently sampled depending on the approach. They should not be mistaken for tumors.

Table 1.

Cytology of normal hepatocytes and bile duct epithelium.

| Hepatocytes | Bile duct epithelium | |

| Arrangement | Singly, 2-dimensional small to large clusters, trabeculae of 2 to 3 cells layer thick | Picket fences with nuclear palisading, monolayered honeycomb sheets |

| Cells | Polygonal to round | Cuboidal to columnar |

| Cytoplasm | Abundant dense granular* to vacuolated (lipid/glycogen), pigments (lipofusin, bile, or hemosiderin) | Scant, pale |

| Nuclei | ||

| Round, centrally located, intranuclear cytoplasmic inclusions, nuclear clearing binucleation | Uniform, small, round, more condensed chromatin | |

| Nucleoli | Prominent | Inconspicuous |

*: cytoplasm appears red-orange, orange-brown, or blue green with Papanicolaou stain, and dark blue with Diff-Quik stain.

Cirrhosis may be sampled by FNA when a dominant nodule mimics a HCC radiologically. The cytology of cirrhotic liver is similar to that of normal liver. Occasionally, markedly reactive hepatocytes may display significant cytological atypia including variable nuclear size, increase nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, coarse chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and frequent bi- or multinucleation. In some instances, they may represent a dysplastic process. Separating a "dysplastic" nodule and HCC in a cirrhotic liver based on cytology alone can be difficult, if not impossible, since their distinction is often based on architectural criteria [27,28]. For this reason, this constitutes a potential source of false positive error [29].

Focal nodular hyperplasia and liver cell adenoma

Both focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH) and liver cell adenoma usually affect patients in their 3rd and 4th decades with a female predominance [26]. The serum AFP level and liver function test are often within normal ranges. Focal nodular hyperplasia is usually asymptomatic and is sometimes characterized by the presence of a central area of low attenuation radiologically [30,31]. Patients with liver cell adenoma may present with an acute abdomen and may be associated with a history of steroid use [32,33].

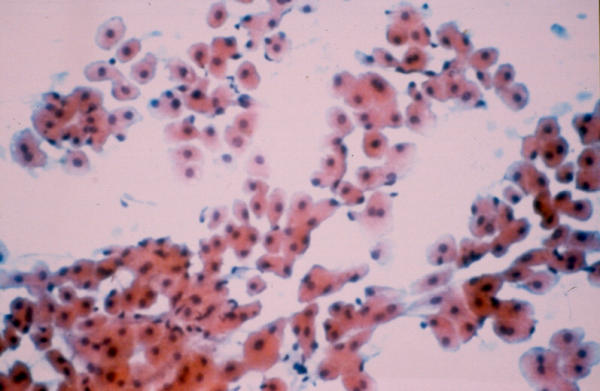

Cytologically, both lesions are composed of bland appearing hepatocytes (Figure 1). For FNH, bile duct epithelium and stromal fragments may be present. Aspirates of liver cell adenoma characteristically contain hepatocytes only; however, evidence of hemorrhage and necrosis may be noted [34,35]. In making a diagnosis of these entities, it is crucial that the needles are within the lesion and only the lesions are sampled.

Figure 1.

Focal nodular hyperplasia. Bland appearing hepatocytes forming loosely cohesive sheets and clusters. Benign ductal epithelium was also noted in the aspirate. (not shown) Patient had an asymptomatic isolated liver mass. The impression was that of a focal nodular hyperplasia (Papanicolaou stain, ×100).

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the most common primary hepatic malignancy [26]. The cytological appearance of HCC varies with the degree of differentiation. The diagnosis of moderately differentiated hepatocellular carcinomas is usually straightforward because they look like normal liver while at the same time demonstrating obvious malignant features. At one end of the spectrum, the tumor is well differentiated – it resembles liver but does not look obviously malignant. On the opposite end of the spectrum, the tumor is poorly differentiated – it is obviously malignant but may be difficult to appreciate its hepatic origin.

Differentiation between well differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma and benign hepatic lesions

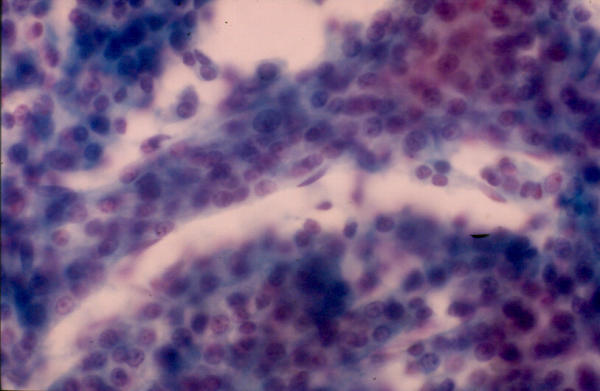

One very helpful diagnostic clue for well differentiated HCC is the presence of one of the two characteristic endothelial patterns. The first one is basketing – endothelial cells wrap around groups or trabeculae of hepatocytes (Figure 2). This pattern is observed in 50% of HCC but is specific for HCC [36-39]. The pattern is seldom seen in benign hepatic lesions or other malignancies. The other endothelial pattern consists of traversing capillaries through groups of hepatocytes (Figure 3). This pattern is noted in over 90% of HCC but is less specific than the "basketing" pattern since it can be seen in other malignancies and rarely, some non-neoplastic liver conditions [38]. Other features that favor a well differentiated HCC over benign hepatic lesions include acinar formation and the presence of prominent "cherry red" nucleoli.

Figure 2.

Hepatocellular carcinoma. Spindle-shaped endothelial cells are noted at the edge of the thickened trabeculae of hepatocytes – basketing endothelial pattern (Papanicolaou stain, ×200).

Figure 3.

Hepatocellular carcinoma. Capillary transverses a group of hepatocytes. (Papanicolaou stain, ×100).

Ancillary studies may be helpful in differentiating benign and neoplastic hepatocytes. Decrease or absent reticulin staining or positive staining pattern outlining trabeculae greater than three cells thickness support the diagnosis of HCC [40,41]. Others have shown that the presence of diffuse immunostaining with CD34 and Factor VIII also favor HCC [41,42]. Positive AFP staining is reported in 40% of HCC, but negative staining does not rule out a diagnosis of HCC [43]. DNA ploidy and staining for proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) have shown some promises, but there is substantial overlap in the patterns of benign and neoplastic processes [44-46].

Differentiation between poorly differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma and metastatic adenocarcinoma

In many instances, a known history of primary tumor is available and the task is to determine whether the morphology of the liver lesion is compatible with that of the known primary tumor. However, when a history is not available, the questions that need to be addressed will be "Is it primary?" or "Is it metastatic?" A markedly elevated serum AFP level and the finding of a single lesion with or without satellite lesions on imaging favor a primary tumor over metastatic disease.

Cytologically, bile production, as evidenced by the presence of bile in the cytoplasm of malignant cells or in canaliculi between malignant cells, is considered diagnostic of HCC. Unfortunately bile is present in only half of the cases [37,39,47]. Although the "basketing" endothelial pattern is pathognomonic for HCC, it is often absent in poorly differentiated tumors. The presence of "traversing" capillaries is less specific and can be seen in some metastatic lesions, particularly, renal cell carcinoma [38]. The key in diagnosing a poorly differentiated HCC is to look for better differentiated cells, with more typical hepatocytic features [48].

Immunocytochemistry is of little help in differentiating poorly differentiated HCC from metastatic lesions because of a lack of highly specific markers. Canalicular staining pattern with antibodies against polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen (pCEA) and diffuse positive staining with endothelial cells markers (such as CD34, Factor VIII) can help distinguish HCC from metastatic adenocarcinoma [38,49-51]. But positive staining with these markers is least often identified in poorly differentiated HCC. Another relatively new marker, HepPar1, has been shown to be quite specific and sensitive as a marker for HCC. About 83% to 100% of HCC stained positive with HepPar1 but only 4% to 15% of metastatic carcinomas were positive [52,53]. Unfortunately, only 56% of poorly differentiated HCC expressed HepPar1 [53].

Fibrolamellar variant of hepatocellular carcinoma

Fibrolamellar variant of HCC is rare, accounting for 1% to 2% of all cases of HCC. However, it is important to recognize this variant because it has a better prognosis [26]. It commonly occurs in patients younger than 35 years and in a non-cirrhotic liver. The serum AFP level is often within normal range. On radiological and gross examination, fibrolamellar variant of HCC is characterized by a lobulated tumor mass with a central stellate scar. The key diagnostic features on FNA are oncocytic neoplastic cells and lamellar fibrosis. The neoplastic cells consist of abundant eosinophilic, granular cytoplasm as a result of numerous swollen mitochondria [54]. Lamellar fibrosis is represented by the presence of dense fibrous tissue with parallel rows of bland fibroblasts.

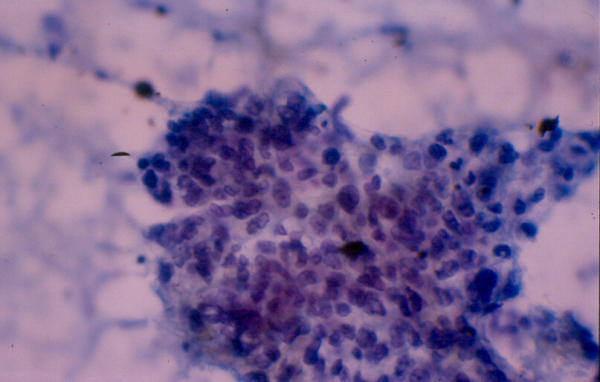

Cholangiocarcinoma

Cholangiocarcinoma accounts for 10% of all primary hepatic malignancy and affects elderly patients [26]. Cytologically, cholangiocarcinoma resembles that of adenocarcinoma arising from pancreato-biliary tract and many other sites [35] (Figure 4). Therefore, its distinction from HCC is usually straightforward, except for poorly differentiated HCC. The presence of mucin staining favors a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma over a HCC. In addition, cholangiocarcinoma is rarely positive for AFP and HepPar 1 [52,55].

Figure 4.

Cholangiocarcinoma. A group of highly pleomorphic glandular cells with nuclear crowding and overlapping (Papanicolaou stain, ×400).

The diagnostic challenge for pathologists is to distinguish cholangiocarcinoma from metastatic adenocarcinoma. Because of much overlap, immunocytochemistry is not helpful in the differential diagnosis. As a result, their distinction relies primarily on clinical history and morphology. A history of known primary and the morphology of hepatic lesions comparable to that of the primary tumor favor a diagnosis of metastatic carcinoma over primary cholangiocarcinoma. There are also certain helpful morphologic clues. For example, the presence of extensive necrosis and columnar neoplastic cells with nuclear palisading would suggest a metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma. Lobular mammary adenocarcinoma is often composed of relatively monotonous neoplastic cells arranged in single file.

Vascular neoplasms

Hemangiomas are the most common benign tumor of the liver. They are often asymptomatic and are detected incidentally in the work up of another disease. Since radiologic imaging is often diagnostic of hemangiomas, they are only occasionally evaluated by FNA. The aspirates are often bloody with few cellular components including spindle-shaped endothelial cells, capillaries, and fragments of fibrovascular connective tissue and smooth muscle [56] (Figure 5). Suspected hemangioma is not considered an absolute contraindication to FNA [57-59]. However, aspirating such lesions carries a low risk of hemorrhage particularly when large needles are used.

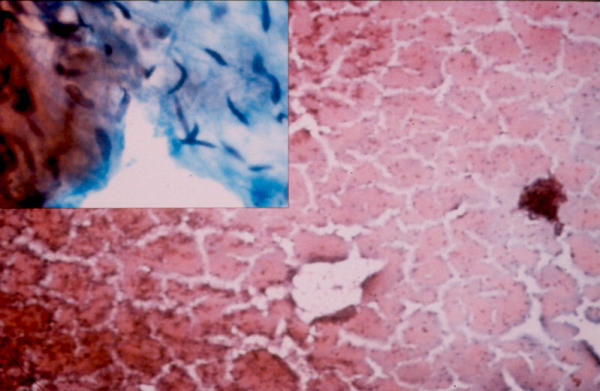

Figure 5.

Hemangioma. The aspirate has a bloody background. High magnification shows rare groups of benign spindle cells. (insert) (Papanicolaou stain, ×40; insert: Papnicolaou stain, ×400).

Angiosarcomas are uncommon. Their clinical presentation is similar to that of HCC. Liver function test is often deranged but the serum AFP level is not elevated. Angiography may be helpful in diagnosis. Cytologically, the tumor consists of single and loosely cohesive groups of pleomorphic spindle shaped and/or epithelioid endothelial cells in a hemorrhagic and necrotic background. Tubular structures, resembling capillaries, may be seen. The differential diagnosis includes other sarcomas, both primary and metastatic.

Cystic lesions

Cystic hepatic lesions seldom undergo FNA. The differential diagnosis includes a wide variety of reactive and neoplastic conditions. Infections may result in cystic hepatic lesions including abscesses and hydatid cysts. Liver abscess can be pyogenic and amoebic. Pyogenic abscesses are often polymicrobial and consist of numerous neutrophils and necrotic tissue on FNA. Amoebic abscesses, on the contrary, contain few or no neutrophils. Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) or iron stains are helpful in identifying trophozoites which are seen in about one third of the cases [60].

Hydatid cysts are caused by the larvae of Echniococcus granulosis. The diagnostic clue on cytology is the finding of scolices or hooklets in the aspirates. Although a clinical suspicion of hydatid cyst is a contraindication for FNA because of the risk of a fatal anaphylactic reaction, no major complications have been reported even when hydatid cysts are inadvertently aspirated [60].

Other non-neoplastic cysts, such as simple hepatic cyst and hepatic foregut cyst, may be aspirated to rule out metastases in patients with a known primary malignancy. The cytology typically consists of macrophages and few bland appearing cuboidal, columnar, and/or squamous epithelial cells in a background of proteinaeous fluid.

Among primary hepatic malignancies, biliary cystadenoma and cystadenocarcinoma are most likely to present as a cystic lesion. They may be an important source of false negative cytological diagnosis because the aspirates are often paucicellular and consists of predominantly macrophages.

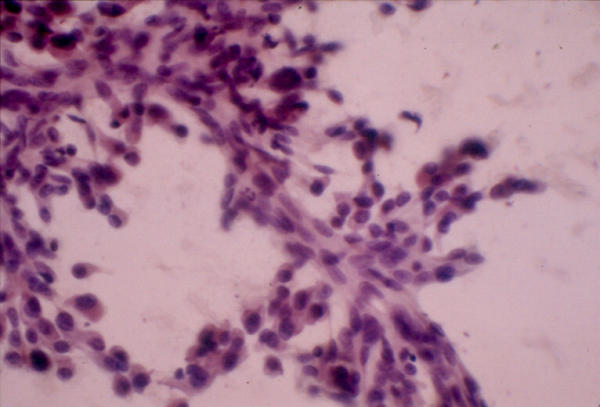

Pediatric hepatic mass

Hepatoblastoma is the most common primary hepatic malignant neoplasm in children. It is also the third most common intra-abdominal malignancy in childhood, following neuroblastoma and Wilm's tumor. Affected children are usually 3 years old or younger and have markedly elevated serum AFP level. The male to female ratio is 2:1. Hepatoblastoma is not associated with cirrhosis. There are 3 histological subtypes – epithelial, anaplastic, and mixed (epithelial and mesenchymal) [35,61]. On cytology, the epithelial component can show a spectrum of differentiation ranging from anaplastic to embryonal to fetal [62]. Anaplastic cells morphologically resemble other "small blue cell tumors" with a uniform population of small cells with scant cytoplasm. Embryonal cells appear as small, oval to spindle shaped cells arranged in cords, rosettes, or papillae (Figure 6). Individual cells have large nuclei, small amount of cytoplasm, and prominent nucleoli. Fetal cells are larger cells with more abundant granular and clear cytoplasm which may contain bile, fat, or glycogen. They often arrange in disorderly trabeculae, acini, and 3-dimensional clusters. The fetal cell type may be associated with extramedullary hematopoesis. The mesenchymal component, when present, appears primitive and undifferentiated.

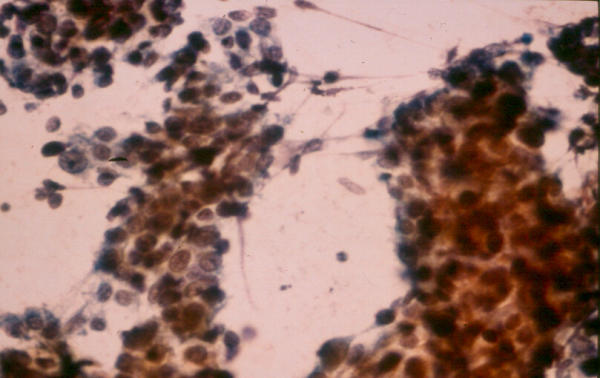

Figure 6.

Hepatoblastom. The aspirate consists of small, oval to spindle-shaped cells with small amount of cytoplasm and prominent nucleoli, characteristic of the embryonal cell type (Papanicolaou stain, ×200).

The differential diagnosis includes HCC which can rarely occur in children. It is important to separate HCC from hepatoblastoma because the latter has a better prognosis [61]. Features that favor a diagnosis of HCC over hepatoblastoma include patient's age greater than 10 years, presence of liver cirrhosis, more definitive hepatic differentiation of neoplastic cells, and the presence of marked pleomorphism and tumor giant cells [60].

Summary

FNA is a useful diagnostic test for evaluating patients with discrete hepatic masses. However, liver FNA poses a number of diagnostic challenges. Correlation with clinical, radiological, and cytological findings is helpful in arriving at the correct diagnosis and therefore increases overall accuracy and cost-effectiveness of the procedure.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- tenBerge J, Hoffman BJ, Hawes RH, Van Enckevort C, Giovannini M, Erickson RA, Catalano MF, Fogel R, Mallery S, Faigel DO, Ferrari AP, Waxman I, Palazzo L, Ben-Menachem T, Jowell PS, McGrath KM, Kowalski TE, Nguyen CC, Wassef WY, Yamao K, Chak A, Greenwald BD, Woodward TA, Vilmann P, Sabbagh L, Wallace MB. EUS-guided fine needle aspiration of the liver: indications, yield, and safety based on an international survey of 167 cases. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 2002;55:859–862. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.124557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babb RR, Jackman RJ. Needle biopsy of the liver. A critique of four currently available methods. West J Med. 1989;150:39–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bret PM, Sente JM, Bretagnolle M, Fond A, Labadie M, Paliard P. Ultrasonically guided fine-needle biopsy in focal intrahepatic lesions: six years' experience. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1986;37:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edoute Y, Tibon-Fisher O, Ben-Haim SA, Malberger E. Imaging-guided and nonimaging-guided fine needle aspiration of liver lesions: experience with 406 patients. J Surg Oncol. 1991;48:246–251. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930480407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Kurtycz DF, Salem R, De Las Casas LE, Caya JG, Hoerl HD. Radiologically guided percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the liver: retrospective study of 119 cases evaluating diagnostic effectiveness and clinical complications. Diag Cytopath. 2002;26:283–289. doi: 10.1002/dc.10097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho CS, McLoughlin MJ, Tao LC, Blendis L, Evans WK. Guided percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy of the liver. Cancer. 1981;47:1781–1785. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810401)47:7<1781::aid-cncr2820470710>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michielsen PP, Duysburgh IK, Francque SM, Van der Planken M, Van Marck EA, Pelckmans PA. Ultrasonically guided fine needle puncture of focal liver lesions. Review and personal experience. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 1998;61:158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilotti S, Rilke F, Claren R, Milella M, Lombardi L. Conclusive diagnosis of hepatic and pancreatic malignancies by fine needle aspiration. Acta Cytologica. 1988;32:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samaratunga H, Wright G. Value of fine needle aspiration biopsy cytology in the diagnosis of discrete hepatic lesions suspicious for malignancy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1992;62:540–544. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb07047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell DA, Carr CP, Szyfelbein WM. Fine needle aspiration cytology of focal liver lesions. Results obtained with examination of both cytologic and histologic preparations. Acta Cytologica. 1986;30:397–402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitlatch S, Nunez C, Pitlik DA. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of the liver. A study of 102 consecutive cases. Acta Cytologica. 1984;28:719–725. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen GK, Gammelgaard J, Fuglo M. Coarse needle biopsy versus fine needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of focal lesions of the liver. Ultrasonically guided needle biopsy in suspected hepatic malignancy. Acta Cytologica. 1983;27:152–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochand-Priollet B, Chagnon S, Ferrand J, Blery M, Hoang C, Galian A. Comparison of cytologic examination of smears and histologic examination of tissue cores obtained by fine needle aspiration biopsy of the liver. Acta Cytologica. 1987;31:476–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscarini L, Fornari F, Bolondi L, Colombo P, Livraghi T, Magnolfi F, Rapaccini GL, Salmi A. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy of focal liver lesions: techniques, diagnostic accuracy and complications. A retrospective study on 2091 biopsies. J Hepatol. 1990;11:344–348. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(90)90219-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawla YK, Ramesh GN, Kaur U, Bambery P, Dilawari JB. Percutaneous liver biopsy: a safe outpatient procedure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1990;5:94–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1990.tb01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornari F, Civardi G, Cavanna L, Di Stasi M, Rossi S, Sbolli G, Buscarini L. Complications of ultrasonically guided fine-needle abdominal biopsy. Results of a multicenter Italian study and review of the literature. The Cooperative Italian Study Group. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24:949–955. doi: 10.3109/00365528909089239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith EH. Complications of percutaneous abdominal fine-needle biopsy. Review. Radiology. 1991;178:253–258. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.1.1984314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman MB. Fine needle aspiration biopsy of the liver. Principal diagnostic challenges. Clin Lab Med. 1998;18:483–506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara V, Garripoli A, Marucci MM, Bonino F, Capussotti L. Colon cancer seeding after percutaneous fine needle aspiration of liver metastasis. J Hepatol. 1993;18:276–278. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(05)80269-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada N, Shinzawa H, Ukai K, Wakabayashi H, Togashi H, Takahashi T, Seo N, Ishiyama S, Tsukamoto M, Fuyama S. Subcutaneous seeding of small hepatocellular carcinoma after fine needle aspiration biopsy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1993;8:195–198. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.1993.tb01513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamazaki K, Matsubara N, Mori M, Gochi A, Mimura H, Orita K, Lygidakis NJ. Needle tract implantation of hepatocellular carcinoma after ultrasonically guided needle liver biopsy: a case report. Hepato-Gastroenterology. 1995;42:601–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austin JH, Cohen MB. Value of having a cytopathologist present during percutaneous fine-needle aspiration biopsy of lung: report of 55 cancer patients and metaanalysis of the literature. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1993;160:175–177. doi: 10.2214/ajr.160.1.8416620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller DA, Carrasco CH, Katz RL, Cramer FM, Wallace S, Charnsangavej C. Fine needle aspiration biopsy: the role of immediate cytologic assessment. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1986;147:155–158. doi: 10.2214/ajr.147.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pak HY, Yokota S, Teplitz RL, Shaw SL, Werner JL. Rapid staining techniques employed in fine needle aspirations of the lung. Acta Cytologica. 1981;25:178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg AG, Finegold MJ. Primary hepatic tumors of childhood. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:512–537. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(83)80005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig JR, Peters RL, Edmonson HA. Tumors of the liver and intrahepatic bile ducts, 2nd series. Washington DC: AFIP; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JM. Pathologic assessment of liver cell dysplasia and benign liver tumors: differentiation from malignant tumors. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1990;7:115–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen C, Berson SD. Liver cell dysplasia in normal, cirrhotic, and hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Cancer. 1986;57:1535–1538. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860415)57:8<1535::aid-cncr2820570816>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottles K, Cohen MB. An approach to fine-needle aspiration biopsy diagnosis of hepatic masses. Diagn Cytopathol. 1991;7:204–210. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840070220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JH, Guzman IJ, Rosai J. Benign tumors of the liver. Pathologic examination of 45 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1978;70:6–17. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/70.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirkhoda A, Farah MC, Bernacki E, Madrazo B, Roberts J. Hepatic focal nodular hyperplasia: CT and sonographic spectrum. Abdom Imaging. 1994;19:34–38. doi: 10.1007/BF02165858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao LC. Oral contraceptive-associated liver cell adenoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytomorphology and mechanism of malignant transformation. Cancer. 1991;68:341–347. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910715)68:2<341::aid-cncr2820680223>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fechner RE. Benign hepatic lesions and orally administered contraceptives. A report of seven cases and a critical analysis of the literature. Hum Pathol. 1977;8:255–268. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(77)80022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nime F, Pickren JW, Vana J, Aronoff BL, Baker HW, Murphy GP. The histology of liver tumors in oral contraceptive users observed during a national survey by the American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer. Cancer. 1979;44:1481–1489. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197910)44:4<1481::aid-cncr2820440443>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suen KC. Diagnosis of primary hepatic neoplasms by fine-needle aspiration cytology. Diagn Cytopathol. 1986;2:99–109. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840020203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MB, Haber MM, Holly EA, Ahn DK, Bottles K, Stoloff AC. Cytologic criteria to distinguish hepatocellular carcinoma from nonneoplastic liver. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;95:125–130. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/95.2.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kung IT, Chan SK, Fung KH. Fine-needle aspiration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Combined cytologic and histologic approach. Cancer. 1991;67:673–680. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910201)67:3<673::aid-cncr2820670324>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitman MB, Szyfelbein WM. Significance of endothelium in the fine-needle aspiration biopsy diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Diagn Cytopathol. 1995;12:208–214. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840120304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao LC, Ho CS, McLoughlin MJ, Evans WK, Donat EE. Cytologic diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma by fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Cancer. 1984;53:547–552. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3<547::aid-cncr2820530329>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman S, Graeme-Cook F, Pitman MB. The usefulness of the reticulin stain in the differential diagnosis of liver nodules on fine-needle aspiration biopsy cell block preparations. Mod Pathol. 1997;10:1258–1264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Boer WB, Segal A, Frost FA, Sterrett GF. Can CD34 discriminate between benign and malignant hepatocytic lesions in fine-needle aspirates and thin core biopsies? Cancer. 2000;90:273–278. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001025)90:5<273::AID-CNCR2>3.3.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottschalk-Sabag S, Ron N, Glick T. Use of CD34 and factor VIII to diagnose hepatocellular carcinoma on fine needle aspirates. Acta Cytologica. 1998;42:691–696. doi: 10.1159/000331828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imoto M, Nishimura D, Fukuda Y, Sugiyama K, Kumada T, Nakano S. Immunohistochemical detection of alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, and ferritin in formalin-paraffin sections from hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 1985;80:902–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adachi E, Hashimoto H, Tsuneyoshi M. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen in hepatocellular carcinoma and small cell liver dysplasia. Cancer. 1993;72:2902–2909. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931115)72:10<2902::aid-cncr2820721008>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng IO, Lai EC, Ho JC, Cheung LK, Ng MM, So MK. Flow cytometric analysis of DNA ploidy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102:80–86. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/102.1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojanguren I, Ariza A, Llatjos M, Castella E, Mate JL, Navas-Palacios JJ. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in normal, regenerative, and neoplastic liver: a fine-needle aspiration cytology and biopsy study. Hum Pathol. 1993;24:905–908. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90141-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottles K, Cohen MB, Holly EA, Chiu SH, Abele JS, Cello JP, Lim RC, Jr, Miller TR. A step-wise logistic regression analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma. An aspiration biopsy study. Cancer. 1988;62:558–563. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19880801)62:3<558::aid-cncr2820620320>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene CA, Suen KC. Some cytologic features of hepatocellular carcinoma as seen in fine needle aspirates. Acta Cytologica. 1984;28:713–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wee A, Nilsson B. pCEA canalicular immunostaining in fine needle aspiration biopsy diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Acta Cytologica. 1997;41:1147–1155. doi: 10.1159/000332837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rishi M, Kovatich A, Ehya H. Utility of polyclonal and monoclonal antibodies against carcinoembryonic antigen in hepatic fine-needle aspirates. Diagn Cytopathol. 1994;11:361–362. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840110409. discussion 361–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrozza MJ, Calafati SA, Edmonds PR. Immunocytochemical localization of polyclonal carcinoembryonic antigen in hepatocellular carcinomas. Acta Cytologica. 1991;35:221–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui MT, Saboorian MH, Gokaslan ST, Ashfaq R. Diagnostic utility of the HepPar1 antibody to differentiate hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in fine-needle aspiration samples. Cancer. 2002;96:49–52. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10311.abs. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman RL, Burke MA, Young NA, Solomides CC, Bibbo M. Diagnostic value of hepatocyte paraffin 1 antibody to discriminate hepatocellular carcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in fine-needle aspiration biopsies of the liver. Cancer. 2001;93:288–291. doi: 10.1002/cncr.9043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farhi DC, Shikes RH, Silverberg SG. Ultrastructure of fibrolamellar oncocytic hepatoma. Cancer. 1982;50:702–709. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19820815)50:4<702::aid-cncr2820500414>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DE, Powers CN, Rupp G, Frable WJ. Immunocytochemical staining of fine-needle aspiration biopsies of the liver as a diagnostic tool for hepatocellular carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 1992;5:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layfield LJ, Mooney EE, Dodd LG. Not by blood alone: diagnosis of hemangiomas by fine-needle aspiration. Diag Cytopathol. 1998;19:250–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0339(199810)19:4<250::AID-DC4>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caturelli E, Rapaccini GL, Sabelli C, De Simone F, Fabiano A, Romagna-Manoja E, Anti M, Fedeli G. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in the diagnosis of hepatic hemangioma. Liver. 1986;6:326–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1986.tb00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaizumi A, Iishi H, Yamamoto R, Kasugai H, Tatsuta M, Okuda S, Kishigami Y, Kitamura T. Diagnosis of hepatic cavernous hemangioma by fine needle aspiration biopsy under ultrasonic guidance. Gastrointest Radiol. 1990;15:39–42. doi: 10.1007/BF01888731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solbiati L, Livraghi T, De Pra L, Ierace T, Masciadri N, Ravetto C. Fine-needle biopsy of hepatic hemangioma with sonographic guidance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1985;144:471–474. doi: 10.2214/ajr.144.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMay R. The art and science of cytopathology. Chicago: ASCP Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ishak KG, Glunz PR. Hepatoblastoma and hepatocarcinoma in infancy and childhood. Report of 47 cases. Cancer. 1967;20:396–422. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1967)20:3<396::aid-cncr2820200308>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas JE, Muczynski KA, Krailo M, Ablin A, Land V, Vietti TJ, Hammond GD. Histopathology and prognosis in childhood hepatoblastoma and hepatocarcinoma. Cancer. 1989;64:1082–1095. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890901)64:5<1082::aid-cncr2820640520>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]