Abstract

In light of increasing cross-communication and possible coalescence of conceptual models of stigma and prejudice, we reviewed 18 key models in order to explore commonalities and possible distinctions between prejudice and stigma. We arrive at two conclusions. First, the two sets of models have much in common (representing “one animal”); most differences are a matter of focus and emphasis. Second, one important distinction is in the type of human characteristics that are the primary focus of models of prejudice (race) and stigma (deviant behavior and identities, and disease and disabilities). This led us to develop a typology of three functions of stigma and prejudice: exploitation and domination (keeping people down); norm enforcement (keeping people in); and disease avoidance (keeping people away). We argue that attention to these functions will enhance our understanding of stigma and prejudice and our ability to reduce them.

Keywords: stigma, prejudice, conceptual models, race, disease, disability

“Ethnic prejudice is an antipathy based upon a faulty and inflexible generalization. It may be felt or expressed. It may be directed toward a group as a whole, or toward an individual because he is a member of that group” (Allport 1954: 9).

“Stigma … is the situation of the individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance” (Goffman 1963: preface). The stigmatized individual is “reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (Goffman 1963: 3).

So are the terms “prejudice” and “stigma” defined by the authors who gave life to each – Allport publishing The Nature of Prejudice in 1954 and Goffman Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity in 1963. Since then, largely separate literatures have developed around the two concepts. However, there is evidence that these literatures have begun to coalesce. Increased attention by prejudice researchers to the targets of prejudice in the 1990s (Crocker and Garcia 2006) brought greater overlap to work on stigma and prejudice. The concepts of stigma, prejudice, and discrimination increasingly are used by the same authors in the same texts (e.g., Heatherton et al. 2000; Levin and Van Laar 2006). In 2006, the National Institute of Mental Health brought together prejudice and stigma researchers to address the problem of mental-illness stigma. This special issue, and the conference that led to it, also aim to bring together concepts and research identified with stigma, prejudice and discrimination. However, to our knowledge, no one has systematically compared conceptual models of prejudice and stigma. Some of the works we review are theories, while others are not. We use the term “conceptual model” as an inclusive term that accurately describes all the contributions. Such a comparison seems worthwhile and timely.

Sometimes entirely separate literatures develop around essentially identical constructs Merton (1973). If this is the case for stigma and prejudice, scholars may borrow freely across the literatures, vastly expanding the theoretical, methodological and empirical resources relevant to both areas. If there are some essential differences between models of prejudice and stigma, a comparison of the two may sharpen our understanding of the sets of models, and it may reveal something about a broader conceptual space in which they both reside. In this case, borrowing would not be precluded but may be more targeted.

Are the parallel lives of stigma and prejudice a consequence of the application of different terms by luminaries in different fields to describe basically the same processes, or are there more fundamental differences in the processes that have been labeled “stigma” and “prejudice?”

METHODS

To address this question, we reviewed 18 key conceptual models in the domains of stigma and prejudice, summarized in Appendix 1. Because prejudice often deals with race, and because prejudice and racism are recognized as closely related concepts (Dovidio 2001; Jones 1997), we included racism models in the prejudice category. We included models we judged to be particularly widely known or influential or to make unique contributions to conceptualizing stigma or prejudice; four of these were added at the suggestion of peer reviewers. Clearly, this set of 18 models is not exhaustive. Other models that we did not include because of space limitations are those of Adorno et al. (1950), Brewer (1979), Greenwald and Banaji (1995), Jost and Banaji (1994), Macrae et al. (1994), Neuberg et al. (2000), Sidanius and Pratto (1999), Sears (1988), Smith (1984), and contributions to the edited collection by Levin and van Laar (2006).

We analyzed the conceptual models in three ways. First, we coded each along the following dimensions: (1) What are the model’s key constructs? (2) Where does the model focus its attention (e.g., on stigmatizing or prejudiced individuals, referred to hereafter as “perpetrators”); on individuals who are the object of stigma or prejudice (referred to hereafter as “targets”); on interactions between perpetrators and targets; and/or in social structures? If the focus is on individuals, what processes does the model focus on (e.g., cognitive, emotional, behavioral)? (3) To what human characteristics does the model claim to apply? (4) Are stigma/prejudice processes viewed as normal or pathological? As processes that are common across individuals or that vary between individuals?

Second, we compared each pair of models searching for contradictions or incompatibilities – cases in which the models make different predictions. Third, we asked whether human characteristics were interchangeable in the model (i.e., could characteristics other than the ones explicitly addressed be “plugged in” to the model?)

This analysis could potentially support several different conclusions: Models of stigma and prejudice are parallel (i.e. describe the same phenomena in different terms) or complementary (i.e., describe different parts of one overarching process) – both “one-animal” conclusions; or they may be contradictory (i.e. make conflicting predictions) or disconnected (i.e., describe distinct and unrelated processes) – both “two-animal” conclusions.

RESULTS

Focus of analysis: Mapping the terrain of stigma and prejudice

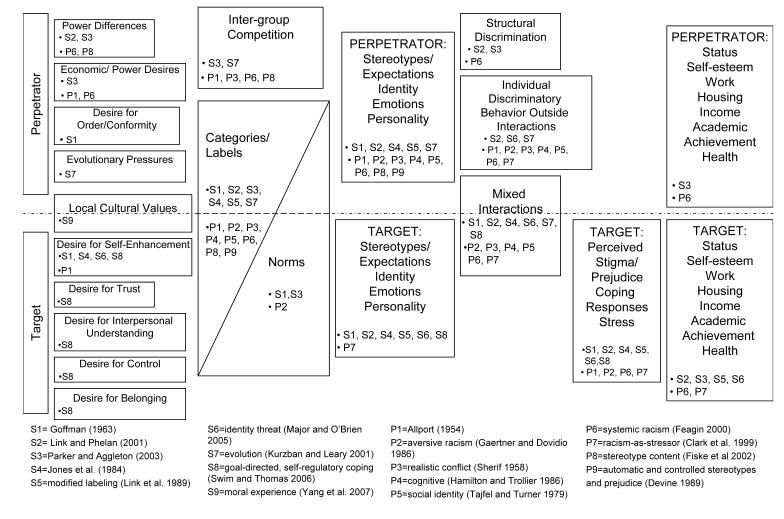

First, we compared the phenomena addressed by the models of prejudice and stigma. We began by enumerating the constructs central to each separate model and fitting each into the conceptual map shown in Figure 1. As in open coding of text, we believed this bottom-up approach would allow the identification of overlapping and non-overlapping areas of focus in models of stigma and prejudice. Figure 1 thus contains but is more extensive than the distinct models from which it was built.

FIGURE 1.

Factors Involved In Stigma And Prejudice

Each box names a construct and lists the models that include the construct. We did not indicate specific causal relationships between constructs; therefore Figure 1 is not a causal model. However, we do intend the figure to represent a rough progression of causal effects from left to right. Above the dotted line are processes pertaining to perpetrators of stigma and prejudice. Below are processes pertaining to targets. On the dotted line are processes engaged in by both groups.

In Column 1 are basic sources or functions of stigma and prejudice and of responses to stigma and prejudice. Above the line are power differences, which Link and Phelan (2001) consider necessary for one group to effectively stigmatize another; desire for power and economic gain (e.g., the profit motives undergirding U.S. slavery, Feagin 2000); social groups’ desire for order and conformity, implicated by Goffman’s identification of norms as the cause of stigma; and evolutionary pressures, which Kurzban and Leary (2001) cite as the source of all stigmatization. Below the line are core social goals (Fiske 2004) that stigma and prejudice threaten and that influence targets’ coping strategies (Swim and Thomas 2006). Broad or local cultural values influence what characteristics are most likely to be targeted for stigma and prejudice and which social values are most threatened for targets (Yang et al. 2007).

In Column 2 are intergroup competition, which we view as following from economic and power desires; categories and labels, emphasized as the cognitive bedrock for prejudice and stigma in most of our models; and norms (Goffman 1963).

In Column 3 are a range of cognitive and emotional processes generated by the forces in Columns 1 and 2. These processes are most often included as they refer to perpetrators, but some models also attend to these processes in targets.

In Column 4 are three ways in which processes in previous columns get translated into behavior and other concrete outcomes that affect targets. Structural discrimination refers to structured practices that can operate independently of prejudiced attitudes, for example, built environments that impede the functioning of people with physical disabilities. Discriminatory behavior can occur outside interactions, for example when an employer discards a job application disclosing a history of psychiatric hospitalization. Finally, the forces in previous columns, working through both perpetrators and targets, shape the processes that unfold in “mixed interactions” (Goffman 1963) between perpetrators and targets.

In Column 5 are targets’ responses to discrimination and problematic interactions with perpetrators, including perceptions of stigma or prejudice, stress and coping. These in turn affect targets’ life outcomes, such as status, self-esteem, work, housing, academic achievement, and health, as described in Column 6. Column 6 also includes such outcomes for perpetrators, because as suggested by models emphasizing conflict and domination (Feagin 2000; Parker and Aggleton 2003), when targets lose in terms of outcomes such as work, housing, and income, perpetrators gain.

Figure 1 reveals considerable variation between models in terms of the processes they focus on. Stigma models place somewhat more emphasis on targets, particularly in terms of stereotypes/expectations, identity and emotions (Column 3). Prejudice models pay more attention to these processes in perpetrators, as well as to individual discriminatory behavior outside interactions. These differences reflect the contrasting foci in the two seminal works on prejudice and stigma: Allport (1954) clearly focused on the perpetrator, while Goffman (1963) focused more on the target. However, Figure 1 reveals no clear fault line between stigma and prejudice models and in fact shows considerable overlap in focus.

Finally, the concept of prejudice refers specifically to perpetrators’ attitudes, and thus might appear narrower in scope than the concept of stigma. However, Figure 1 shows that, when we consider explanatory models of prejudice that include not only the construct itself but also its causes and consequences, the scope of prejudice and stigma models is similar.

Contradictory predictions

Next we compared pairs of models in search of contradictory predictions. We identified two points of contention. The first concerns the impact of stigma or prejudice on psychological well-being of targets. Based on the situational nature of stigma and the importance of coping, the identity threat models of Crocker et al. 1998 and Major & O’Brien 2005 argue that targets of stigma and prejudice are not necessarily as psychologically harmed as most models suggest. The second concerns evolutionary vs. social/psychological processes. Kurzban and Leary’s (2001) evolutionary model does not deny that social processes may play a part, but argues that evolutionary processes actually explain most stigmatization. Social and psychological models of prejudice and stigma generally do not mention evolutionary factors. Neither of these disagreements represents a schism between prejudice and stigma models. Both identity-threat and evolutionary models identify themselves with stigma, and the models from which they differ include both stigma and prejudice models. Overall, our review of the separate models leads us to conclude that differences of focus indicate complementarity rather than contradiction.

Normality/common processes vs. psychopathology/individual variation

Next we considered whether models view stigma or prejudice as being rooted in normal processes that work similarly across individuals or whether they focus on individual differences or psychopathology. In general, stigma models emphasize that stigma is rooted in normal processes common across individuals. Goffman expresses this most eloquently: “stigma management is a general feature of society … the stigmatized and the normal have the same mental make-up, and that necessarily is the standard one in our society; he who can play one of these roles … has exactly the required equipment for playing out the other” (Goffman 1963: 130-31).

Most of the prejudice models also emphasize normal processes that are common across individuals. Tajfel attributed out-group discrimination to “a generic norm of out-group behavior” that is “extraordinarily easy to trigger off” (Tajfel 1970: 102). Feagin (2000) emphasizes that racism is rooted in the system rather than in individuals. Although Allport attends to prejudice as a normal process (Chapter 2 is titled “The normality of prejudgement”), his stands out among the models we reviewed in also emphasizing individual variation and psychopathology (i.e., prejudiced vs. tolerant personalities). Notably, we find nothing in models emphasizing common processes that deny a role for individual variations. For example, while emphasizing the roots of prejudice in common processes, Sherif notes “there is good reason to believe that some people growing up in unfortunate life-circumstances may become more intense in their prejudices and hostilities” (Sherif 1958: 350). Likewise, Allport (1954) clearly does not deny the role of the more universal processes. Thus, we do not see this as a dividing line between stigma and prejudice.

Interchangeability of characteristics that are the object of stigma and prejudice

To this point, our analysis suggests variations in conceptual models that do not align with a stigma/prejudice distinction. However, our last device for detecting differences between models uncovered a distinction we think is significant. We asked whether a given model could be applied to characteristics other than those the model explicitly addresses. In other words, are characteristics that are the object of stigma or prejudice interchangeable?

All but one of the stigma models are comprehensive in terms of the characteristics they address (The exception is Link et alia’s modified labeling theory, which applies specifically to mental illness; however the model should be applicable to any stigmatized characteristic about which cultural attitudes are learned before the stigmatized label is acquired). For example, Goffman’s tribal stigmas, blemishes of individual character, and abominations of the body appear to cover every imaginable form of stigma or prejudice. Similarly, several of the prejudice models are not tied to particular in- and out-groups, and social identity theory is based in research showing that arbitrarily identified characteristics can serve as the basis of discrimination (Tajfel 1970). However, other prejudice models are more restrictive. Allport focuses on nationality, race, religion and ethnicity, and the racism models focus specifically on race. For some of these more restricted models, it is easy to imagine substituting other human characteristics for race. For example, Clark et alia’s (1999) analysis of the stressful consequences of discrimination should apply to any characteristic that is the target of stigma or prejudice. However, in other cases, this substitution does not make sense. This is most clear for Allport (1954) and for Feagin’s (2000) systemic racism model. Although much of Allport’s analysis could apply to characteristics such as mental illness or sexual deviance, a key statement is this: “In every society on earth the child is regarded as a member of his parents’ groups. He belongs to the same race, stock, family tradition, religion, caste, and occupational status” (Allport 1954: 31). The same cannot be said for most illnesses and disabilities and deviations such as non-normative sexualities that may be targeted for stigma or prejudice. These may be more common in some families than others, but they are not shared by families in the same way that race, religion and caste are. We believe this distinction between what we call “group” characteristics (those shared by family members) and “individual” characteristics (those that occur more sporadically within families) is a significant distinction uncovered by our examination of models of prejudice and stigma.

This distinction is reinforced by an examination of the human characteristics which have been analyzed in terms of “stigma” and “prejudice” in published literature. We searched the titles of journal articles indexed in Psycinfo every five years from 1955 (the year after The Nature of Prejudice was published) to 2005, and we searched the articles to identify the human characteristics they analyzed. These years were chosen as a sample of the 52 years between the publication of The Nature of Prejudice and the present. We located 162 articles with “stigma” in the title and 139 with “prejudice.” The number of relevant articles increased steadily over time; consequently, forty-six percent of the articles were published in 2005, and 75% of the articles were published in 1995 or later. Results are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Types of human characteristic with which “prejudice” and “stigma” are associated in journal articlesa

| “Prejudice” (N=139) |

“Stigma” (N=162) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Race or ethnicity | 62% | 4% |

| Gender | 7% | 2% |

| Behavioral/identity deviance | ||

| Sexual orientation | 3% | 4% |

| Other deviance | 4% | 8% |

| Illness/disability | ||

| Mental illness | 0% | 38% |

| Substance use | 0% | 4% |

| HIV/AIDS | 1% | 16% |

| Other illness/disability | 6% | 22% |

| Other characteristic | 6% | 0% |

| Unspecified characteristic | 11% | 2% |

Based on a search of PsycInfo for 1955, 1960, 1965, 1970, 1975, 1980, 1985, 1990, 1995, 2000 and 2005.

In most cases (62%), “prejudice” is connected with race or ethnicity, followed by 11% for articles that deal with prejudice as a general phenomenon. In these cases, race or ethnicity would implicitly be considered a core characteristic of concern. In contrast, an overwhelming proportion of articles with “stigma” in the title – 92% – dealt with illness, disability or behavioral or identity deviance. We use “deviance” here not as a pejorative term but in the classical sociological sense of deviation from the norms of a particular social group. We include both deviant behavior and identity. For example, sexual deviation may be defined in terms of behavior or identity; both are objects of stigma and prejudice. Only 6% of stigma articles dealt with race, ethnicity or gender.

Why some characteristics become the target of stigma and prejudice and others do not

This distinction in the types of characteristics studied in the name of prejudice vs. stigma led us to another question: Why do particular characteristics become the object of stigma and prejudice, and are there different reasons for different characteristics? Many of the models we examined emphasize that the things we target with stigma and prejudice are socially constructed and vary dramatically across time and place. This is certainly an important aspect of stigma and prejudice. At the same time, the choice of particular human characteristics as targets of stigma and prejudice is not a random process. We believe the reasons that particular characteristics get selected may represent an important variation that was revealed by our comparison of stigma and prejudice models.

Above we discussed the association of prejudice with “group” and stigma with “individual” characteristics. We now make a further distinction between what we see as the two major types of characteristics addressed in the stigma literature – disease/disability and deviant behavior/identity. Based on these distinctions, we develop at a typology of functions of stigma and prejudice. We do not imply that a desirable end is served by stigma and prejudice by using the term “function”; we use the term rather to indicate the sources, reasons or motives for stigma and prejudice.

We propose that there are three functions of stigma and prejudice: (1) exploitation/domination, (2) enforcement of social norms and (3) avoidance of disease. We also refer to these as keeping people down; keeping people in; and keeping people away.

Exploitation and domination

Some groups must have less power and fewer resources for dominant groups to have more. Some groups provide labor that is exploited by others or perform unpleasant or dangerous tasks that others prefer to avoid. Ideologies develop to legitimate and help perpetuate these inequalities (Jost and Banaji 1994; Marx and Engels 1976). We argue that exploitation and domination, along with their corresponding ideologies, are one basic function of stigma and prejudice. Race is a clear example. Feagin describes how racism was “integral to the foundation of the United States” (Feagin 2000: 2). “At the heart of the Constitution was protection of the property and wealth of the affluent bourgeoisie in the new nation”(Feagin 2000: 10). Slavery was seen as an essential tool for maintaining this wealth, and discrimination was considered necessary. Ideologies that viewed African-Americans as inferior, less worthy, and dangerous (i.e. stereotypes) developed to legitimate the discrimination (Morone 1997).

By this reasoning, we also consider stigma and prejudice against women, people of low socioeconomic status and ethnic minority groups to be rooted in exploitation and domination. Enforcement of social norms. Societies also find it necessary to extract conformity with social norms. We propose that failure to comply with these norms, usually cast in terms of morality or character (Goffman 1963; Morone 1997), is a second ground for stigmatization and prejudice. Here, the function of stigma and prejudice may be to make the deviant conform and rejoin the in-group, as in reintegrative shaming (Braithwaite 1989), or it may be to clarify for other group members the boundaries of acceptable behavior and identity and the consequences for non-conformity (Erikson 1966). In either case, the goal is to increase conformity with norms. This type of stigma and prejudice should only apply to behavior or identity perceived as voluntary. For example, although people with mental retardation may behave in deviant ways, we would not include mental retardation here, because the application of stigma and prejudice cannot be expected to change the behavior. Examples of this form of stigma and prejudice are numerous: non-normative sexual behavior or identities, such as homosexuality, polygamy or (in some contexts) extra-marital sex; political deviations; various forms of criminal behavior, such as theft, rape or murder; substance abuse; smoking; perhaps obesity and some mental illnesses such as depression. Although there is disagreement about whether sexual orientations and identities are voluntary, we believe that stigma or prejudice against people with non-normative sexual orientations and identities are based on public perception that they are voluntary, and we therefore include them under norm- based stigma and prejudice. This function of stigma and prejudice is aligned with exploitation/domination in that the dominant group is influential in defining the unacceptable. However, it differs importantly in that the dominant group does not, in a significant way, profit from the labor of the deviants.

Avoidance of disease

A large set of characteristics remains to be explained in terms of stigma and prejudice function. In the review of journal articles (Table 1), we grouped these as illness and disability, and they constituted the largest set of articles with stigma in the title. Included here are mental illnesses, including mental retardation, physical illnesses such as cancer, skin disorders and AIDS, physical disabilities and imperfections such as missing limbs, paralysis, blindness and deafness. Again, the dominant group does not profit from the labor of people with these characteristics – in fact, they have trouble getting jobs. Neither are we trying to control their behavior or set an example for others by subjecting them to stigma and prejudice. We find this form of stigma and prejudice difficult to explain in purely social or psychological terms, and we turn to evolutionary psychology. Kurzban and Leary (2001) (also see Neuberg et al. 2000) argue that there are evolutionary pressures to avoid members of one’s species who are infected by parasites. Parasites can lead to “deviations from the organism’s normal (healthy) phenotype” (Kurzban and Leary 2001: 197) such as asymmetry, marks, lesions and discoloration; coughing, sneezing and excretion of fluids; and behavioral anomalies due to damage to muscle-control systems. They argue that the advantage of avoiding disease “might have led to the evolution of systems that regard deviations from the local species-typical phenotype to be … unattractive;” that systems might develop wherein people would “desire to avoid … close proximity to potentially parasitized individuals;” and that “because of the possible cost of misses, the system should be biased toward false positives, and this bias might take the form of reacting to relatively scant evidence that someone is infested” (Kurzban and Leary 2001: 198).

Aesthetics, one of Jones et al.’s (1984) six dimensions of stigmatized “marks,” are particularly relevant here. An evolutionary explanation for disease avoidance is consistent with humans’ aesthetic preference for facial symmetry (Grammar and Thornhill 1994) which develops early in life and across cultures (Johnson et al. 1991) and with Jones et al.’s observation that physical anomalies seem to “automatically elicit ‘primitive’ affective responses in the beholder” “not mediated by labels or causal attributions” (Jones et al. 1984: 226). Consistent with Kurzban and Leary’s (2001) argument that disgust should be the primary emotion associated with parasite-avoidance stigma is the plethora of words and phrases to describe affective reactions to physical deviance, including disgusting, nauseating, offensive, sickening, repelling, revolting, gross, makes you shudder, loathsome, and turns your stomach (Jones et al. 1984).

The evolutionary explanation applies most clearly to visible illnesses, deformities and deviations in physical movements. If “species-atypical phenotype” can be extended to illnesses that are not necessarily visible, such as cancer, and to psychological functioning that appears “diseased,” such as psychosis, then the evolutionary model may apply broadly to our “illness and disability” category. However, this broad application depends critically on the strength of bias toward false positives, which is unknown. Because evidence to connect many stigmatized illnesses to parasite avoidance is lacking, the evolutionary explanation must be considered provisional.

According to this argument, the function of disease-avoidance stigma and prejudice is rooted in our evolutionary past rather than in current social pressures. People may indeed consciously avoid others because they appear to be infected. However, the strong emotional reactions involved in this type of stigma and prejudice, as well as its application to individuals who are not actually infected (“false positives”), are attributed to the disproportionate survival and procreation of individuals who exhibited extreme vigilance, resulting in exaggerated reactions in present-day humans. Thus, when we refer to the disease-avoidance function of stigma or prejudice, we are referring to its past, not current, function.

Relation to other functional explanations of stigma and prejudice

Some previous work has attempted to understand the functions of stigma or prejudice for individuals or groups. Proposed functions include coping with guilt and anxiety (Allport 1954), self-esteem enhancement through downward comparisons (Wills 1981), management of terror associated with awareness of one’s mortality (Solomon et al. 1991), simplification of information processing (Allport 1954; Hamilton and Trollier 1986), competitive group advantage (Allport 1954; Feagin 2000; Tajfel and Turner 1979) and system justification (Corrigan et al. 2003; Jost and Banaji 1994). These explanations do not specify why particular groups are targeted for stigma or prejudice (Stangor and Crandall 2000). Two functional explanations (Kurzban and Leary 2001; Stangor and Crandall 2000) are, like ours, both comprehensive (i.e., include all types of targets of stigma or prejudice) and specify why some characteristics are stigmatized and others not. A similar evolutionary model was proposed by Neuberg et al. (2000). Here we briefly delineate how our functional typology differs from these.

Stangor and Crandall (2000) argue that all stigmatization is rooted in perceived threat to the individual or culture, including intergroup conflict, health threats, physical features that denote threat, belief in a just world, and moral threats. Each of our three types of stigma and prejudice can be construed as threats (domination/exploitation defends against the threat of loss of power and economic advantage; norm enforcement defends against the threat of social disorder and harm to group members; and disease avoidance defends against the threat of infection). However, particularly for exploitation/domination, models that emphasize the role of power and status differences in stigma and prejudice (Feagin 2000; Fiske et al. 2002; Link and Phelan 2001; Parker and Aggleton 2003) provide a more accurate representation, we believe, of what is at stake for the perpetrators of this type of stigma and prejudice. Accordingly, the function of stigma and prejudice based on exploitation and domination is the desire to maintain advantage rather than the threat of losing advantage. Webster’s dictionary includes words like “punishment,” “injury,” “trouble,” “menace,” and “danger” in defining “threat,” words that aptly describe the situation of a subordinate group but would not be called into play to define the loss of a power advantage. Omitting the concept of exploitation/domination and subsuming it under the concept of threat, we believe, robs a functional schema of the very thing that marks group-based stigma and prejudice such as racism as distinct, and its inclusion provides an important niche for this type of prejudice and stigma in an inclusive model of stigma and prejudice.

Kurzban and Leary’s (2001) functional schema strongly overlaps ours. They argue that stigma derives from three evolutionary pressures. Dyadic-cooperation adaptations result in avoidance of poor social exchange partners (people who are unpredictable, are resource-poor, or cheat). Coalition-exploitation adaptations lead to exclusion and exploitation of social out-groups. Parasite-avoidance adaptations were described above. These correspond fairly closely to our functions of norm enforcement, exploitation/domination and disease avoidance, respectively. Both schemas also correspond closely to Goffman’s (1963) three types of stigma – tribal-based stigmas, blemishes of individual character, and abominations of the body. Goffman, however, did not analyze these in terms of their functions. The major difference between Kurzban and Leary’s (2001) and our explanations is that they argue for an evolutionary basis of all stigmatization, whereas we reserve the evolutionary explanation for disease avoidance. To the extent that behaviors adaptive in the past are currently adaptive, stigma and prejudice may be co-determined by biological vestiges of past adaptation pressures and by current social and psychological pressures (Neuberg et al. 2000). For example, social groups benefit now as in the distant past from dominating and exploiting other groups. Similarly, control of at least some types of deviant behavior serves group well-being now as in the past. In these cases, whatever evolutionary functions may have been served, they are strongly bolstered by current social functions. We believe these social functions are a more fruitful focus for understanding and, particularly, reducing stigma and prejudice. By contrast, as discussed above, we find disease-avoidance stigma and prejudice difficult to explain in terms of current functions. While it is functional to avoid someone with a serious infectious disease, it is difficult to discern the function of avoiding someone with a non-infectious disease or physical imperfection. It is the illogic of this avoidance as well as the strong and seemingly automatic emotional reactions to such individuals that lead us to call on evolutionary processes. It is currently impossible to determine to what extent stigma and prejudice may be attributable to evolutionary pressures and to what extent they may be due to current social/psychological pressures: All or none of these types of stigma may have evolutionary roots. More generally, data are not available to determine which of the three functional explanations we have compared – Stangor and Crandall’s (2000), Kurzban and Leary’s (2001), or our own – has more validity. However, each is plausible and distinct enough from the others to warrant consideration and empirical testing.

Distinctions and commonalities in stigma/prejudice processes across the three functions

Our functional typology raises the question of whether the stigma/prejudice process varies depending on function. For example, the reasoning behind exploitation/domination-based stigma and prejudice suggest that inter-group competition, derogatory stereotyping, and discrimination in allocation of resources may be particularly prominent here (Feagin 2000), and emotions of pity (Fiske et al. 2002) or fear and hate (Kurzban and Leary 2001) may also be important. Attribution theory (Weiner et al. 1988) and Kurzban and Leary’s (2001) evolutionary model suggest that anger and punishment may be prominent in stigma and prejudice based on norm enforcement. Kurzban and Leary (2001) and evidence about aesthetics in stigma (e.g., Jones et al. 1984) suggest that fear, disgust and avoidance may be prominent in stigma and prejudice based on disease avoidance. Targets’ experiences and coping strategies may also vary according to function.

Nevertheless, we suggest that the social processes involved in enacting and maintaining stigma and prejudice are more alike than different once a human characteristic gets selected as a basis for stigma and prejudice. All involve categorization, labeling, stereotyping, negative emotions, interactional discomfort, social rejection and other forms of discrimination, status loss and other harmful effects on life chances of targets, as well as stigma management and coping. The experiences of different targeted groups may become “homogenized” by a confluence of these pressures. Morone (1997) describes how racial, ethnic and immigrant out-groups become stereotyped as posing moral and health threats to the majority. Here, stigma and prejudice rooted in exploitation/domination call into service the other two bases of stigma and prejudice: norm enforcement and disease avoidance. Similarly, although exploitation may not have been the original function of stigma and prejudice against people with depression or AIDS, those people are more vulnerable to exploitation as a result of the degraded social status attending all forms of stigma and prejudice. Finally, stigma and prejudice against some characteristics serve more than one function. For example, stigma and prejudice associated with HIV/AIDS is likely based on both norm enforcement and disease avoidance.

One area where distinctions based on function may be particularly important is the question of how to prevent or reduce stigma and prejudice. Some aspects of stigma and prejudice can be reduced without attention to function. Anti-discrimination laws have decreased discrimination and do not depend on a consideration of function. We argue, however, that stigma and prejudice reduction will be enhanced by attention to function. Subtle but significant anti-Black prejudice persists despite real changes effected by law (Gaertner and Dovidio 1986). The continuing exploitation of African-Americans may help explain why racial prejudice has been so difficult to eradicate: Continued exploitation requires continued justification. Modern legitimations are more subtle but remain powerful. Stigma and prejudice based on exploitation/domination may not be completely eliminated without changes to the power hierarchy (Parker and Aggleton 2003). Similarly, stigma and prejudice based on norm enforcement may be difficult to eradicate without changes in social norms.

An evolutionary basis for stigma and prejudice based on disease avoidance may seem to argue against any possibility of reducing stigma or prejudice. But that is not necessarily so. Sex roles may also have some evolutionary base but can be altered. Disease-based stigma and prejudice may operate largely through automatic emotional reactions, and familiarity might reduce these reactions, just as desensitization through exposure can reduce evolutionarily based phobias. Accordingly, research suggests that personal contact is one of the most promising approaches to reducing stigma and prejudice associated with mental illness (Kolodziej and Johnson 1996). Whether or not our particular schema of the functions of stigma and prejudice proves useful, we believe efforts to reduce stigma and prejudice will be enhanced by considering why the characteristic is the target of stigma and prejudice.

CONCLUSIONS: ONE ANIMAL OR TWO?

Our analysis suggests some differences in emphasis and focus, but we conclude that models of prejudice and stigma describe a single animal. However, distinctions in the functions of stigma and prejudice led us to delineate three sub-types of this animal. We believe a useful distinction can be made between stigma and prejudice based on exploitation and domination (keeping people down), norm enforcement (keeping people in) and disease avoidance (keeping people away). This typology both distinguishes between and unites work in the stigma and prejudice traditions. Although these distinctions are diminishing, work in the prejudice tradition grew from concerns with social processes driven by exploitation and domination, such as racism, while work in the stigma tradition has been more concerned with processes driven by norm enforcement and disease avoidance. Our analysis suggests, however, that these processes are quite similar and are all part of the same animal.

What should we call this animal? Throughout this paper, we agnostically paired the terms “stigma” and “prejudice” as we investigated the relation between the corresponding sets of conceptual models. Going forward, we follow Dovidio et al. (2000) and others in using the term “stigma” when referring to a broader process including many components shown in Figure 1 and “prejudice” to refer to attitudinal components of this process.

We believe our comparison of conceptual models of stigma and prejudice has proven fruitful in several ways. First, the strong congeniality and large degree of overlap we found between models of stigma and prejudice should encourage scholars to reach across stigma/prejudice lines when searching for theory, methods and empirical findings to guide their new endeavors. The conceptual map we generated (Figure 1) may help scholars identify new constructs that are relevant to their current thinking and research. Finally, we hope that the distinction between stigma and prejudice based on exploitation/domination, norm enforcement and disease avoidance will be useful in understanding stigma and prejudice more fully and in reducing both.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a Career Development (K02) Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (Dr. Phelan) and a research (R01) award from the National Human Genome Research Institute (Dr. Phelan) as well as research and technical assistance from Naomi Feldman and Claire Espey.

APPENDIX 1. Brief synopses of conceptual schemes of prejudice and stigma

PREJUDICE MODELS (arranged chronologically)

The Nature of Prejudice (Allport 1954)

“Ethnic prejudice is an antipathy based upon a faulty and inflexible generalization. It may be felt or expressed. It may be directed toward a group as a whole, or toward an individual because he is a member of that group” (p. 9). “Prejudice is ultimately a problem of personality formation and development” (p. 41). A broad array of influences affect the development of prejudice, including cognitive, social structural, cultural and psychodynamic factors.

Realistic group conflict model (Sherif 1958)

Individuals brought together with common goals form “in-group” structures with hierarchical statuses and roles. If two in-groups are brought together under conditions of competition and group frustration, hostile attitudes and actions and social distance develop between groups.

Social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner 1979)

Individuals have multiple social identities corresponding to different group memberships. The salience of different identities varies according to context. When identity with a particular group is salient, self-esteem associated with membership in that group as well as in-group favoritism result. Prejudice results from the need for a positive social identity with an ingroup.

Aversive prejudice/racism (Gaertner and Dovidio 1986)

“Aversive racism represents a particular type of ambivalence in which the conflict is between feelings and beliefs associated with a sincerely egalitarian value system and unacknowledged negative feelings and beliefs about blacks… . The negative affect that aversive racists have for blacks is not hostility … [but] discomfort, uneasiness, disgust and sometimes fear (Gaertner and Dovidio 1986; pp. 62-3).

Cognitive perspective (Hamilton and Trolier 1986)

Human information-processes systems inevitably result in the categorization of individuals into groups, which in turn inevitably results in stereotypes and in-group biases in attitudes and behavior.

Automatic and controlled components of stereotypes and prejudice (Devine 1989)

Knowledge of stereotypes is distinct from their endorsement (prejudice). Stereotypes are learned early in life and activated automatically. Prejudiced or non-prejudiced personal beliefs are acquired later, are under conscious control and can override responses based on stereotypes.

Racism as stressor (Clark et al. 1999)

“The perception of an environmental stimulus as racist results in exaggerated psychological and physiological stress responses that are influenced by constitutional … sociodemographic … psychological and behavioral factors, and coping responses. Over time, these stress responses … influence health outcomes” (p. 806).

Systemic racism (Feagin 2000; Feagin and McKinney 2003)

Racism has been a core aspect of American culture and society since the country’s founding. It is rooted in the dependence of the wealth of the new country’s elite on slavery and maintained by a racist ideology of white superiority and systematic life advantages for whites.

Stereotype content model (Fiske et al. 2002)

“(a) 2 primary dimensions [of stereotype content] are competence and warmth, (b) frequent mixed clusters combine high warmth with low competence (paternalistic) or high competence with low warmth (envious), and c) distinct emotions (pity, envy, admiration, contempt) differentiate the 4 competence-warmth combinations” (p. 878)

STIGMA MODELS (arranged chronologically)

Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (Goffman 1963)

Stigma is “the situation of the individual who is disqualified from full social acceptance” (preface). The stigmatized individual is “reduced in our minds from a whole and usual person to a tainted, discounted one” (p. 3). Goffman emphasizes stigma as enacted in “mixed interactions” between stigmatized and non-stigmatized individuals and how stigmatized individuals manage those interactions.

Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships (Jones et al. 1984)

“The stigmatizing process involves engulfing categorizations accompanied by negative affect that is typically alloyed into ambivalence or rationalized through some version of a just-world hypothesis” (p. 296). Jones et al. identify six dimensions of stigmatizing “marks”: Concealability, course, disruptiveness, aesthetic qualities, origin and peril.

Modified labeling theory of mental disorders (Link et al. 1989)

Socialization leads to beliefs about how most people treat mental patients. When individuals enter psychiatric treatment, these beliefs become personally relevant. The more patients believe they will be devalued and discriminated against, the more they feel threatened by interacting with others. They may employ coping strategies that can have negative consequences for social support networks, jobs and self-esteem.

Identity threat models (Crocker et al. 1998; Major and O’Brien 2005; Steele and Aronson 1995)

Possessing a stigmatized identity increases exposure to potentially stressful, identity-threatening situations. Collective representations (e.g., beliefs about prejudice), situational cues, and personal characteristics affect appraisals of the significance of those situations for well-being. Responses to identity threat can be involuntary (e.g., emotional) or voluntary (i.e., coping efforts). These responses can affect outcomes such as self-esteem, academic achievement and health.

“Conceptualizing stigma” (Link and Phelan 2001)

Stigma occurs when elements of labeling, stereotyping, cognitive separation into categories of “us” and “them,” status loss, and discrimination co-occur in a power situation that allows these components to unfold.

Evolutionary model (Kurzban and Leary 2001)

“Phenomena … under the rubric of stigma involve a set of distinct psychological systems designed by natural selection to solve specific problems associated with sociality… . Human beings possess cognitive adaptations designed to cause them to avoid poor social exchange partners, join cooperative groups (for purposes of between-group competition and exploitation) and avoid contact with those differentially likely to carry communicable pathogens” (p. 187).

“HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action” (Parker and Aggleton 2003)

“Stigma plays a key role in producing and reproducing relations of power and control. It causes some groups to be devalued and others to feel … they are superior. Ultimately … stigma is linked to the workings of social inequality” (p. 16).

Goal-directed, self-regulatory coping (Swim and Thomas 2006)

Discrimination threatens core social goals of self-enhancement, trust, understanding, control and belonging. The weighting of these goals, as well as appraisal of one’s ability to engage in responses and the ability of a response to address goals, influence choice of coping responses by targets of discrimination.

Moral experience and stigma (Yang et al. 2007)

“Moral experience, or what is most at stake for actors in a local social world” shapes the stigma process for stigmatizers and stigmatized. “Stigma exerts its core effects by threatening the loss of what really matters and what is threatened.” (p. 1524).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adorno TW, Frenkel-Brunswik E, Levison DJ, Sanford RN. The Authoritarian Personality. Harper; New York: 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. The Nature of Prejudice. Doubleday; Garden City, NY: 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite J. Crime, Shame and Reintegration. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB. Ingroup bias in the minimal intergroup situation: A cognitive-motivational analysis. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:307–24. [Google Scholar]

- Clark R, Anderson NB, Clark VR, Williams DR. Racism as a stressor for African American. American Psychologist. 1999;54:805–16. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.10.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AC, Ottati V. From whence comes mental illness stigma? International Journal of Social Psychiatry. 2003;49:142–57. doi: 10.1177/0020764003049002007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Garcia JA. Stigma and the social basis of the self: A synthesis. In: Levin S, Van Laar C, editors. Stigma and Group Inequality. Erlbaum; Mahwah, N.J.: 2006. pp. 287–308. [Google Scholar]

- Crocker J, Major B, Steele C. Social stigma. In: Gilbert D, Fiske S, Lindzey G, editors. Handbook of Social Psychology. 4th edition Volume 2. McGraw-Hill; Boston: 1998. pp. 504–53. [Google Scholar]

- Devine PG. Stereotypes and prejudice: Their automatic and controlled components. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:5–18. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF. On the nature of contemporary prejudice: The third wave. Journal of Social Issues. 2001;57:829–49. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Major B, Crocker J. Stigma: Introduction and overview. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The Social Psychology of Stigma. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR. Racist America: Roots, Current Realities, and Future Reparations. Routledge; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Feagin JR, McKinney KD. The Many Costs of Racism. Rowman; Lanham, MD: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST. Social Beings: A Core Social Motives Approach to Social Psychology. Wiley and Sons; Hoboken, NJ: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske ST, Cuddy AJC, Glick P, Xu J. A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaertner SL, Dovidio JF. The aversive form of racism. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, Discrimination, and Racism. Academic; Orlando. FL: 1986. pp. 61–89. [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Simon & Schuster; New York: 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Grammar K, Thornhill R. Human (Homo sapiens) facial attractiveness and sexual selection: The role of symmetry and averageness. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 1994;108:223–42. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.108.3.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognitions: Attitudes, self-esteem and stereotypes. Psychological Review. 1995;102:4–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton DL, Trollier TK. Stereotypes and stereotyping: An overview of the cognitive approach. In: Dovidio JF, Gaertner SL, editors. Prejudice, Discrimination and Racism. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1986. pp. 127–63. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The Social Psychology of Stigma. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MH, Dziurawiec S, Ellis H, Morton J. Newborns’ preferential tracking of face-like stimuli and its subsequent decline. Cognition. 1991;40:1–19. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(91)90045-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones E, Farina A, Hastorf A, Markus H, Miller DT, Scott R. Social Stigma: The Psychology of Marked Relationships. Freeman; New York: 1984. A. [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM. Prejudice and Racism. 2nd ed McGraw-Hill; New York: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Jost JT, Banaji MR. The role of stereotyping in system-justification and the production of false consciousness. British Journal of Social Psychology. 1994;33:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Kolodziej ME, Johnson BT. Interpersonal contact and acceptance of persons with psychiatric disorders: A research synthesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:1387–96. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.6.1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzban R, Leary MR. Evolutionary origins of stigmatization: The functions of social exclusion. Psychological Bulletin. 2001;127:187–208. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin S, Van Laar C, editors. Stigma and Group Inequality. Erlbaum; Mahwah, N.J.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Cullen FT, Struening E, Shrout P, Dohnrenwend BP. A modified labeling theory approach in the area of mental disorders: An empirical assessment. American Sociological Review. 1989;54:400–23. [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- Macrae CN, Milne AB, Bodenhause GV. Stereotypes as energy-saving devices: A peek inside the cognitive toolbox. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1994;66:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Major B, O’Brien LT. The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx K, Engels F. The German Ideology. 3rd rev. ed Progress Publishers; Moscow: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK. Theoretical and Empirical Investigations. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1973. The Sociology of Science. [Google Scholar]

- Morone JA. Enemies of the people: The moral dimension to public health. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law. 1997;22:993–1020. doi: 10.1215/03616878-22-4-993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuberg SL, Smith DM, Asher T. Why people stigmatize: Toward a biocultural framework. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The Social Psychology of Stigma. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 31–61. [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherif M. Superordinate goals in the reduction of intergroup conflict. American Journal of Sociology. 1958;63:349–56. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon S, Greenberg J, Pyszczynski T. A terror management theory of social behavior: The psychological functions of self-esteem and cultural worldviews. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol 24. Academic Press; San Diego: 1991. pp. 93–159. [Google Scholar]

- Stangor C, Crandall CS. Threat and social construction of stigma. In: Heatherton TF, Kleck RE, Hebl MR, Hull JG, editors. The Social Psychology of Stigma. Guilford Press; New York: 2000. pp. 62–87. [Google Scholar]

- Steele C, Aronson E. Stereotype vulnerability and the intellectual test performance of African-Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:797–811. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER. Model of social inference processes. Psychological Review. 1984;91:392–413. [Google Scholar]

- Swim JK, Thomas MA. Responding to everyday discrimination: A synthesis of research on goal-directed, self-regulatory coping behaviors. In: Levin S, Van Laar C, editors. Stigma and Group Inequality. Erlbaum; Mahwah, N.J.: 2006. pp. 105–28. [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H. Experiments in intergroup discrimination. Scientific American. 1970;223:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, Turner JC. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In: Austin WG, Worchel S, editors. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. Brooks/Cole; Monterey, CA: 1979. pp. 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Weiner B, Perry RP, Magnusson J. An attributional analysis of reactions to stigmas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;55:738–48. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.55.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Downward social comparison principles in social psychology. Psychological Bulletin. 1981;90:245–71. [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Kleinman A, Link BG, Phelan JC, Lee S, Good B. Culture and stigma: Adding moral experience to stigma theory. Social Science and Medicine. 2007;64:1524–35. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]