Abstract

Background

Echocardiography (echo) quantified LV stroke volume (SV) is widely used to assess systolic performance after acute myocardial infarction (AMI). This study compared two common echo approaches – predicated on flow (Doppler) and linear chamber dimensions (Teichholz) – to volumetric SV and global infarct parameters quantified by cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR).

Methods

Multimodality imaging was performed as part of a post-AMI registry. For echo, SV was measured by Doppler and Teichholz methods. Cine-CMR was used for volumetric SV and LVEF quantification, and delayed-enhancement CMR for infarct size.

Results

142 patients underwent same-day echo and CMR. On echo, mean SV by Teichholz (78±17ml) was slightly higher than Doppler (75±16ml; Δ=3±13ml, p=0.02). Compared to SV on CMR (78±18ml), mean difference by Teichholz (Δ=−0.2±14; p=0.89) was slightly smaller than Doppler (Δ−3±14; p=0.02) but limits of agreement were similar between CMR and echo methods (Teichholz: −28, 27 ml, Doppler: −31, 24ml). For Teichholz, differences with CMR SV were greatest among patients with anteroseptal or lateral wall hypokinesis (p<0.05). For Doppler, differences were associated with aortic valve abnormalities or root dilation (p=0.01). SV by both echo methods decreased stepwise in relation to global LV injury as assessed by CMR-quantified LVEF and infarct size (p<0.01).

Conclusions

Teichholz and Doppler calculated SV yield similar magnitude of agreement with CMR. Teichholz differences with CMR increase with septal or lateral wall contractile dysfunction, whereas Doppler yields increased offsets in patients with aortic remodeling.

Keywords: echocardiography, stroke volume, cardiac magnetic resonance

Introduction

LV stroke volume is an important index of cardiac performance that has been used to gauge therapeutic response and predict adverse clinical event risk.1–3 Echocardiography (echo) is widely utilized for LV functional assessment and can measure stroke volume by a variety of methods. One common approach uses Doppler imaging to directly measure LV stroke volume based on flow.4 While this approach is theoretically attractive, clinical application can be compromised by technical factors such as angular acuity of aortic blood flow, and/or off-axis aortic annular dimensions. As an alternative, 2D echo enables stroke volume to be calculated by formulae (i.e. Teichholz) predicated on dynamic changes in linear chamber dimensions.5 Although straightforward, Teichholz pitfalls include off-axis LV measurements as well as discordance between regional and global LV systolic function, as can occur in patients with coronary artery disease.6–8 While different structural factors hold the potential to impact different echo formulae, these concepts have not been tested in clinical practice. As echo-evidenced stroke volume is widely used to gauge LV performance, better understanding of structural indices that impact stroke volume quantification is of substantial importance.

Cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR), which provides excellent LV cavity definition and has been used as a reference standard for LV chamber size,9–11 enables volumetric stroke volume quantification without geometric assumptions. CMR can also quantify LV infarct size in a manner that closely correlates with pathology-evidenced myocyte necrosis,12, 13 enabling integrated study of relationships between LV functional and infarct parameters. In prior studies, echo methods have been shown to yield substantial differences with volumetric stroke volume as quantified by CMR.14–16 However, different echo methods have not been compared, and the influence of LV remodeling on echo calculated stroke volume has not been studied.

This study examined Doppler and Teichholz calculated stroke volume among a broad cohort of patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI). In all patients, echo was performed on the same day as CMR using a uniform protocol tailored for stroke volume assessment - including dedicated Doppler imaging, as well as contrast-enhanced echo (for optimized LV chamber definition). The purposes were three-fold - (1) to independently compare Doppler and linear echo methods to CMR-quantified stroke volume; (2) to identify structural factors that impact different echo approaches for stroke volume quantification; and (3) to assess echo-quantified stroke volume as an index of global LV injury following AMI.

Methods

Population

The population was comprised of patients with acute ST elevation AMI enrolled in a prospective imaging registry (clinical trials # NCT00539045) at Weill Cornell Medical College. Patients with substantial (> mild echo-evidenced) mitral regurgitation, or ≥1 day interval between imaging tests (echo, CMR) were excluded so as to minimize confounding between geometric and flow-based stroke volume methods.

Comprehensive clinical data were collected following AMI, including cardiac risk factors, treatment strategy, and medication regimen. Coronary angiograms were reviewed for infarct-related culprit vessel and graded for angiographic (APPROACH) jeopardy score.17 The study was conducted in accordance with the Weill Cornell Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Image Acquisition

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echo was performed by experienced sonographers using commercially available equipment (General Electric Vivid-7, Philips ie33) with phased array transducers. Images were acquired in apical and parasternal orientations in accordance with American Society of Echocardiography guidelines.18 LV flow (velocity time integral [VTI]) was assessed using pulsed-wave Doppler sampled in the LV outflow tract (LVOT), with parameters tailored to avoid signal artifact (i.e. aliasing) and optimize signal profile. 2D images were acquired in apical and parasternal orientations, with the latter also used for M-mode imaging. Valvular regurgitation was assessed and graded in accordance with consensus criteria based on Doppler and M-mode imaging.19, 20 In accordance with the established registry protocol, sonographic contrast (Definity; Lantheus Medical Imaging, North Billerica MA) was administered intravenously to all patients during 2D imaging so as to optimize assessment of LV chamber dimensions and regional function.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

CMR was performed using 1.5 Tesla scanners (General Electric, Waukesha WI). Exams consisted of two components - (1) cine-CMR for LV geometry/function and (2) delayed enhancement (DE-) CMR for infarct quantification. Cine-CMR was performed using an ECG-gated steady-state free precession pulse sequence. DE-CMR was performed following intravenous gadolinium infusion, using a segmented inversion recovery pulse sequence (typical in plane resolution 1.4×1.4mm, slice thickness 5mm) with inversion times tailored to null viable and enhance infarcted myocardium. Cine-CMR and DE-CMR images were obtained in matching short- and long-axis planes. Contiguous short axis images were acquired throughout the LV from the level of the mitral valve annulus through the apex.

Image Interpretation

Echocardiography

LV stroke volume on echo was independently calculated using two established methods:4–6

Teichholz: SV = [7/(2.4+LVDd)]*[LVDd]3 − [7/(2.4+LVSd)]*[LVSd]3, with LVDd and LVSd respectively corresponding to LV internal dimensions at end-diastole and end-systole.

Doppler: SV = LVOTAREA * VTILVOT, with LVOTAREA calculated based on LVOT diameter on 2D echo (π*[diameter/2]2) and VTILVOT calculated using pulsed-wave Doppler.

For Teichholz, LV internal dimensions were measured in parasternal long axis at the level of the LV minor axis, approximately at the level of the mitral valve leaflet tips.18 For Doppler, VTILVOT was acquired in apical 3- or 5-chamber orientation sampled immediately proximal to the aortic valve.4 Doppler flow was quantified based on planimetry of the maximum flow aortic profile acquired during multiple cardiac cycles. Intra- and inter-observer reproducibility for each stroke volume method was tested in a sub-group comprising 10.6% (n=15) of the overall study population.

To assess factors that could potentially impact stroke volume quantification by each method, echoes were analyzed for multiple geometric and functional indices. LV chamber dilation was assessed based on end-diastolic diameter, as measured in mid-parasternal orientation. LV function wall motion was scored using a 17-segment model. Segmental function was graded as follows - 0=normal contraction; 1=mild hypokinesia; 2=moderate hypokinesia; 3=severe hypokinesia; 4=akinesia; 5=dyskinesia.

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

Cine-CMR was used to quantify chamber volumes, which were calculated based on summation of contiguous short axis slices from LV base – apex. Basal and apical image positions were defined in accordance with previously reported criteria,21, 22 with the basal LV defined by the basal most image encompassing at least 50% of circumferential myocardium. End-diastole and end-systole were defined on the basis of the respective image frames demonstrating the largest and smallest cavity size, with chamber volumes quantified based on manual planimetry of endocardial borders. Papillary muscles and trabeculae were included within myocardial contours (i.e. excluded from chamber volumes), in accordance with established CMR methods previously shown to provide high intra- and inter-observer reproducibility.22, 23 LV stroke volume was calculated on cine-CMR based on end-diastolic (EFV) and end-systolic (ESV) chamber volumes. In addition to stroke volume, EDV and ESV were used to calculate LV ejection fraction (EF = [(EDV-ESV)/EDV] × 100%).

DE-CMR was used to quantify LV infarct size and distribution. Regional infarction, based on transmural extent of hyperenhancement, was graded for each LV segment (17-segment model) as follows: 0=no hyperenhancement; 1=1–25%; 2=26–50%; 3=51–75%; 4=76–100%. Global infarct size (% LV myocardium) was calculated by summing all segmental scores (each weighted by the midpoint of range of hyperenhancement) and dividing by total number of regions.24

Each imaging test (echo, CMR) was independently interpreted by an experienced reader (RBD, JWW) blinded to clinical data and the results of the other modality.

Statistical Methods

Comparisons of continuous variables (expressed as mean ± standard deviation) were made using Student’s t test for two group comparisons, and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for multiple group comparisons. Differences between methods was assessed using the method of Bland and Altman,25 which yielded mean difference as well as limits of agreement between methods (mean ± 1.96 SD). Pearson correlation coefficients and linear regression analysis were used to evaluate univariate and multivariate associations between imaging parameters. Two-sided p<0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Calculations were performed using SPSS 14.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Results

The population was comprised of 142 post-AMI patients who underwent same day echo and CMR, comprising 95% of eligible registry patients imaged during the study interval (9/2006 – 1/2012). In 5% of otherwise eligible patients (n=7), Doppler or Teichholz calculations could not be performed due to sub-optimal Doppler profiles (n=5) and/or poor endocardial definition (n=2).

In all patients, echo and CMR were completed within 6 hours, without interval administration of pharmacologic agents or administration of intravenous fluids. Imaging was performed within 6 weeks (27±7 days) following AMI. Heart rate was minimally higher during CMR (65±13 beats/min) than echo (64±10 beats/min; p=0.049). 99% (140/142) patients were in sinus rhythm at the time of echo imaging (atrial fibrillation; n=2). Table 1 reports clinical and imaging characteristics of the study population.

Table 1.

Clinical and Conventional Imaging Characteristics

| Age (year) | 56 ± 12 |

| Gender (% male) | 83% (118) |

| Atherosclerosis Risk Factors | |

| Hypertension | 43% (61) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 47% (66) |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 23% (32) |

| Tobacco use | 34% (48) |

| Family history | 30% (42) |

| Prior Coronary Artery Disease | |

| Prior coronary revascularization | 8% (11) |

| Prior myocardial infarction | 6% (9) |

| Infarct Related Parameters | |

| Chest pain duration (hours) | 11 ± 9 |

| Treatment Strategy | |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 75% (106) |

| Thrombolysis | 25% (36) |

| Infarct Related Artery | |

| Left Anterior Descending | 56% (80) |

| Left Circumflex | 10% (14) |

| Right Coronary Artery | 34% (48) |

| Angiographic Jeopardy Score | 26 ± 11 |

| Infarct Size (% myocardium)* | 16 ± 9 |

quantified using delayed enhancement CMR

Stroke Volume Quantification

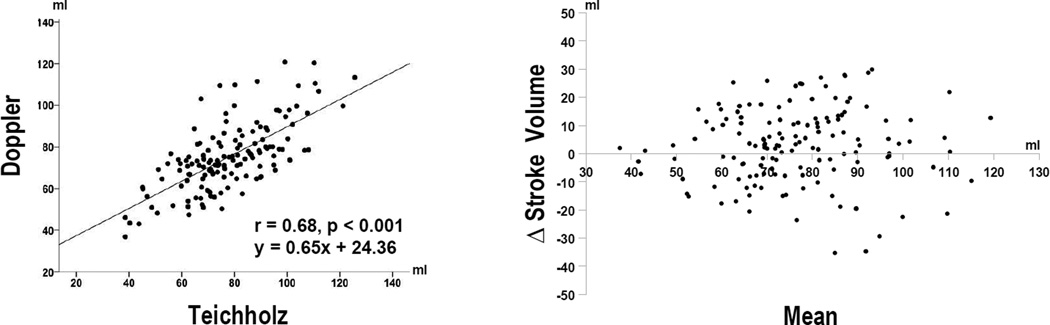

Echo quantified stroke volume was, on average, slightly lower by Doppler (75±16ml) than by Teichholz (78±17ml [Δ=3±13], p=0.02). Reproducibility was high for both Doppler (intra-observer Δ = −3±7ml [95% CI −7, 0.8ml], p=0.11 | inter-observer Δ = −2±7ml [95% CI −6, 2ml], p=0.26) and Teichholz (intra-observer Δ = 2±7ml [95% CI −2, 5ml], p=0.37 | inter-observer Δ= 0.5±8ml [95% CI −4, 5ml], p=0.83) stroke volume measurements. Whereas the two methods correlated well (r=0.68, p<0.001), magnitude of difference varied substantially across the overall study population (limits of agreement −29, 24ml) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Comparison of Teichholz and Doppler Methods.

Scatter (left) and Bland-Altman (right) plots comparing echo methods. For Bland-Altman plot, solid line = mean, dashed lines = 2 ± standard deviations.

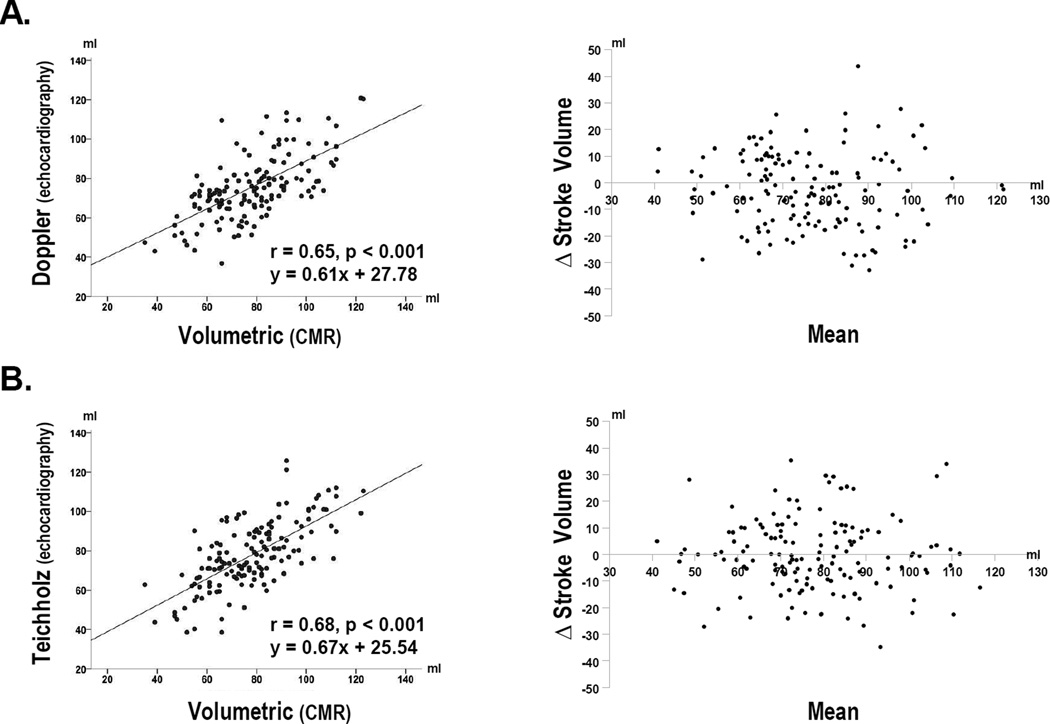

Table 2 compares each echo method to CMR. Doppler results were, on average, slightly lower than volumetric stroke volume by CMR (p=0.02), whereas Teichholz and CMR did not differ significantly (p=0.89). Whereas mean differences yielded by both echo methods were small, this was largely attributable to a near even balance between higher and lower calculated stroke volume in relation to CMR (Figure 2). Consistent with this, limits of agreement yielded by Teichholz (−28, 27 ml) and Doppler (−31, 25ml) were of similar magnitude.

Table 2.

LV Chamber Volumes and Functional Parameters

| Echocardiography | CMR | Δ | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doppler | ||||

| Stroke volume | 75 ± 16 | 78 ± 17 | −3± 14 | .02 |

| Teichholz | ||||

| Stroke volume | 78 ± 17 | 78 ± 17 | −0.2 ± 14 | .89 |

| Ejection fraction | 50 ± 10 | 54 ± 11 | −4 ± 7 | <0.001 |

| End diastolic volume | 158 ± 30 | 148 ± 39 | 11 ± 27 | <0.001 |

| End systolic volume | 80 ± 26 | 70 ± 32 | 11 ± 19 | <0.001 |

Bold-face type p values refer to p<0.05

Figure 2. Comparison of Echo Methods with CMR.

Scatter (left) and Bland-Altman (right) plots comparing Doppler (2A) and Teichholz (2B) calculated stroke volume to CMR. Note that both methods yielded similar correlations and limits of agreement with the reference of CMR.

Table 2 also compares Teichholz calculated volumes and ejection fraction to corresponding CMR measurements. Results demonstrate that small mean differences in stroke volume were attributable to evenly matched overestimation by Teichholz as applied at end-systole and end-diastole. Teicholz overestimation yielded a greater proportionate impact at end-systole, resulting in a small, albeit significant, underestimation of ejection fraction (−4±7 points, p<0.001) in comparison to CMR.

Predictors of Methodological Discordance

Table 3 reports differences between each echo method and the reference of CMR, with results stratified based on LV and aortic imaging variables. For Teichholz, results (3A) demonstrate that magnitude of difference with CMR was greatest among patients with segmental wall motion abnormalities involving the anteroseptum or lateral wall (both p<0.05). For Doppler, differences with CMR (3B) were greatest among patients with aortic valve abnormalities or root dilation (p=0.01), but were independent of regional LV contractile dysfunction (p=NS).

Table 3.

Methodological Differences in Relation to Cardiac Structure and Function

| 3A. Teichholz | |||

| Δ Stroke Volume vs. CMR | |||

| Present | Absent | P | |

| LV Chamber Remodeling* | |||

| LV Dilation | 2 ± 17 ml | −0.4 ± 13 ml | 0.54 |

| LV Segmental (≥ Moderate) Hypokinesis | |||

| Anterior | −3 ± 15 ml | 1 ± 13 ml | 0.12 |

| Anteroseptal | −3 ± 12 ml | 2 ± 15 ml | 0.01 |

| Inferoseptal | −3 ± 14 ml | 1 ± 13 ml | 0.08 |

| Inferior | −0.1 ± 15 ml | −0.2 ± 13 ml | 0.99 |

| Inferolateral | −5 ± 15 ml | 0.9 ± 13 ml | 0.049 |

| Anterolateral | −9 ± 11 ml | 0.7 ± 14 ml | 0.015 |

| Aortic Abnormalities‡ | |||

| 3 ± 15 ml | −1 ± 14 ml | 0.30 | |

| 3B. Doppler | |||

| Δ Stroke Volume vs. CMR (ml) | |||

| Present | Absent | P | |

| LV Chamber Remodeling* | |||

| LV Dilation | −1 ± 17 ml | −3 ± 14 ml | 0.61 |

| LV Segmental (≥ Moderate) Hypokinesis | |||

| Anterior | −2 ± 14 ml | −3 ± 14 ml | 0.57 |

| Anteroseptal | −3 ± 14 ml | −3 ± 15 ml | 0.91 |

| Inferoseptal | −3 ± 14 ml | −3 ± 15 ml | 0.84 |

| Inferior | −3 ± 14 ml | −3 ± 14 ml | 0.95 |

| Inferolateral | −3 ± 15 ml | −3 ± 14 ml | 0.98 |

| Anterolateral | −3 ± 17 ml | −3 ± 14 ml | 0.98 |

| Aortic Abnormalities‡ | |||

| 4 ± 16 ml | −4 ± 14 ml | 0.02 | |

Threshold based on 1 standard deviation above mean (LVEDD ≥ 6.4cm)

Aortic root dilation (>4cm), or bicuspid/stenotic/sclerotic aortic valve

Regarding remodeling, results shown in Table 3 demonstrate that LV chamber dilation – as measured based on echo-evidenced end-diastolic diameter – was not associated with greater offsets between Teichholz (p=0.54) or Doppler (p=0.61) calculated stroke volume and the reference of CMR.

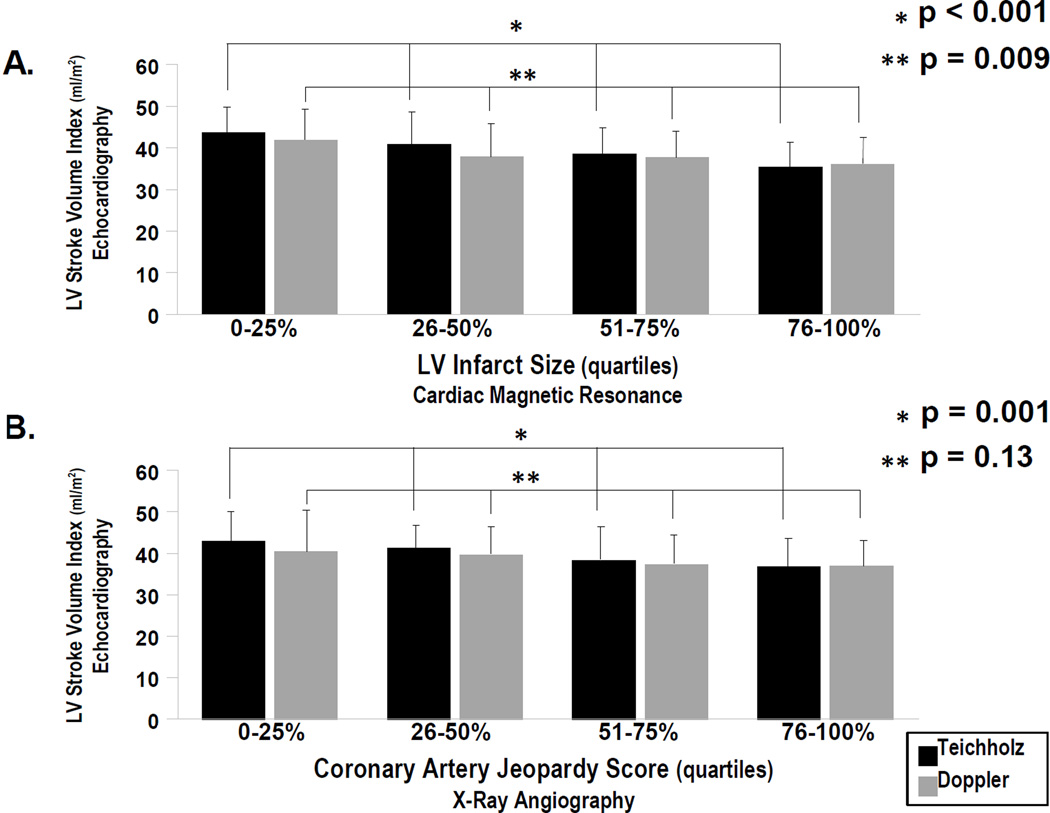

Echo Stroke Volume in Relation to Global LV Injury

Teichholz calculated stroke volume index (i.e. normalized for body surface area) correlated with global LV injury indices as measured based on DE-CMR quantified infarct size (r = −0.42, p<0.001) or angiography-calculated jeopardy score (r = −.31, p<0.001). Doppler results demonstrated a weaker correlation with DE-CMR infarct size (r = −.24, p=0.004), and only a trend towards correlation (r = 0.16, p=0.057) with angiographic jeopardy score.

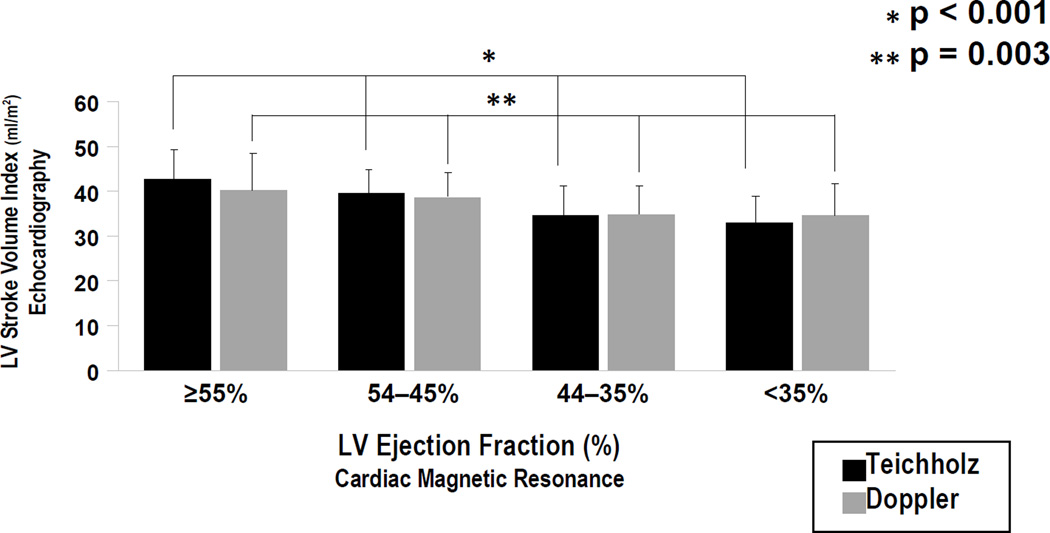

Figure 3 stratifies echo-calculated stroke volume index in relation to quartiles of both CMR infarct size and angiographic jeopardy score as stratified across the study population. For Teichholz, there was a stepwise decrease in mean stroke volume in relation to increasing infarct size and jeopardy score (both p≤.001) For Doppler, a similar relationship was demonstrated for CMR infarct size (p=0.009), with non-significant differences when mean stroke volume was compared between groups stratified by jeopardy score (p=0.13). Figure 4 compares both echo methods among groups stratified by CMR-quantified ejection fraction, demonstrating that both Teichholz (p<0.001) and Doppler (p=0.003) stroke volume decreased stepwise in relation to severity of global LV systolic dysfunction as quantified on CMR.

Figure 3. Echo Stroke Volume in Relation to Global LV Infarct Burden.

Echo calculated stroke volume index (mean ± standard deviation) among groups stratified based on DE-CMR quantified infarct size (3A) and angiography-calculated jeopardy score (3B). Stroke volume index stratified by quartile-based cutoffs as applied to each infarct variable (i.e. right-most bars correspond to largest, left-most bars to smallest infarct size/jeopardy score).

Figure 4. Echo Stroke Volume in Relation to Global LV Systolic Dysfunction.

Echo calculated stroke volume index (mean ± standard deviation) among groups stratified based on cine-CMR quantified ejection fraction. For both Teichholz (black bars) and Doppler (grey), stroke volume index decreased stepwise in relation to magnitude of systolic dysfunction by CMR (p<0.001)

Discussion

This is the first study to compare two common echo approaches for LV stroke volume – predicated on linear chamber dimensions (Teichholz) and flow (Doppler) – to volumetric assessment by CMR. Findings demonstrate new insights regarding performance of each echo formula in relation to CMR, as well as structural indices that impact formulaic calculations. Whereas both methods yielded small mean differences with CMR, substantial variability existed across the population, as evidenced by similar limits of agreement for Teichholz (Δ − 0.2±14ml; [limits of agreement −28, +28ml]) and Doppler (Δ −3.0±14ml; [−31, +25ml). For Teichholz, anteroseptal or lateral wall systolic dysfunction was associated with stroke volume underestimation, consistent with orientation of linear chamber dimensions used in this formula. For Doppler, altered aortic geometry (root dilation, bicuspid valve, or aortic stenosis/sclerosis) was associated with stroke volume over-estimation, possibly attributable to impact of valve and/or aortic annular deformation on Doppler signal profile and calculated aortic size.

Our results extend upon prior studies that have examined echo stroke volume methods in relation to CMR, but have not compared different echo approaches or examined reasons for discordance between modalities. Whereas several studies have compared echo and cine-CMR for LV chamber volumes or ejection fraction, we are aware of only three that have examined stroke volume - two analyzed echo via biplane planimetry,14, 15 and one via Teichholz.16 While these studies yielded larger mean differences (range 8–34ml) than did ours, the smallest of the three was generated using Teichholz (Δ=8±20ml).16 Our results demonstrate that Teichholz stroke volume correlated well with Doppler (r=0.68, p<0.001), and that magnitude of difference between echo methods (limits of agreement −29ml, 24ml) was similar to that between echo-CMR comparisons. Taken together with our findings concerning determinants of methodological performance, these data support use of Teichholz in patients in whom Doppler is suboptimal due to aortic dilation, valve abnormalities, or otherwise limited quality flow assessment.

As for reasons for smaller stroke volume differences in our study compared to prior work, we speculate that this may be partially explained by differences in echo protocols. Whereas our study examined a broad series of post-AMI subjects (n=142) undergoing same day echo and CMR, prior studies have encompassed smaller cohorts (n=20–47),14, 15 or compared tests performed up to 1 month apart.16 Additionally, all echoes in our study were acquired using a standardized protocol that included contrast administration. Echo contrast is known to improve endocardial definition and reduce differences between echo and CMR for LV volumes and ejection fraction.10, 26–28 It is possible that echo contrast reduced Teichholz differences with CMR stroke volume. Linear echo measurements may have also been affected by contrast, with improved cavity definition resulting yielding calculated chamber volumes than might be obtained with non-contrast echo. However, whereas our study utilized contrast echo, findings concerning impact of regional contractile dysfunction on echo-calculated stroke volume are broadly relevant to patients with known septal or lateral wall dysfunction following MI, and are also applicable to non-contrast echo when image quality is sufficient to reliably assess regional wall motion.

While CMR provides a valuable means of volumetric stroke volume assessment, it is also possible that differences between modalities may be partially attributable to CMR-specific factors. For example, LV papillary muscles and trabeculae can be difficult to account for via manual planimetry,21, 29 as is conventionally used for CMR analysis. Prior work has demonstrated that papillary muscles/trabeculae contribute significantly to LV mass, and that failure to exclude these structures from the blood pool significantly alters volumetric calculations.22, 30, 31 Consistent with this, among prior stroke volume studies, marked inter-modality differences have been observed when papillary muscles were included in CMR quantified LV chamber volumes, which have disproportionately affected end-diastolic as compared to end-systolic volume, and resulted in higher CMR stroke volume compared to echo.14, 15 Additionally, heart rate variability between breath-holds can produce temporal differences between individual CMR images, potentially altering cumulative volumes summed from LV short axis images acquired during different time points. Taken together, these factors may contribute to offsets between CMR measurements and physiologic chamber volumes.

Beyond methodological comparisons, our study also examined echo-quantified stroke volume in relation to global indices of LV injury. Stroke volume calculated by both methods decreased stepwise in relation to increases in DE-CMR quantified infarct size (p<0.01). Teichholz calculated stroke volume also decreased inversely in relation to coronary jeopardy score (p=0.001). Consistent with these findings, both echo formulae tested in this study were developed or validated based on invasive hemodynamic indices of LV performance.4, 32 While stroke volume decrements have been linked to post-AMI enzyme release,33 enzymatic markers provide an indirect assessment of infarct size that can be affected by factors such as variability in sampling time and enzymatic clearance. DE-CMR enables non-invasive infarct quantification in a manner that closely mirrors pathology evidenced myocyte necrosis as quantified at variable times following AMI.12, 13 Our results demonstrate that both Teichholz and Doppler calculated stroke volume provide physiologic indices of global LV injury as assessed based on DE-CMR quantified LV infarct size.

Several limitations should be noted. First, stroke volume methods were compared in a cohort comprised exclusively of patients undergoing contrast echo. Echo contrast rates remain low in clinical practice,34 despite consensus recommendations that contrast be used in cases where non-contrast imaging yields suboptimal image quality.18, 35 Current findings may not be applicable to non-contrast echoes with poor endocardial cavity definition or uncertainty regarding regional wall motion. Additionally, while this study tested Doppler and Teichholz, other well-validated approaches such as biplane planimetry were not tested. This issue warrants future investigation. Last, while results demonstrated variability in stroke volume calculated using different imaging modalities performed on the same day, stroke volume itself can vary slightly on a near instantaneous basis.36 Physiologic variability in LV stroke volume may partially explain differences in echo SV formulae, each of which were calculated using indices measured during different cardiac cycles. Geometric assumptions intrinsic to each echo formula may have also contributed to variability between methods, which demonstrated small albeit significant mean differences (Δ=3±13, p=0.02), but substantial limits of agreement (−29, 24ml) across the population. Variability in stroke volume between echo formulae highlights the limitations of comparing mean values between individual echo methods and CMR.

In summary, this study demonstrates that Doppler and Teichholz calculated stroke volume yield similar difference with CMR and reflect global LV injury after AMI. Doppler calculations yield greatest offset with CMR in the context of aortic remodeling, whereas Teichholz offsets are associated with septal or lateral wall contractile dysfunction. Future studies are necessary to test these concepts in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, and compare prognostic utility of LV performance indices as quantified by different geometric methods.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: K23 HL102249-01, Lantheus Medical Imaging, Doris Duke Clinical Scientist Development Award (JWW)

Citations

- 1.De Marco M, de Simone G, Roman MJ, Chinali M, Lee ET, Russell M, Howard BV, Devereux RB. Cardiovascular and metabolic predictors of progression of prehypertension into hypertension: the Strong Heart Study. Hypertension. 2009;54(5):974–980. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.129031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lonnebakken MT, Gerdts E, Boman K, Wachtell K, Dahlof B, Devereux RB. In-treatment stroke volume predicts cardiovascular risk in hypertension. J Hypertens. 2011;29(8):1508–1514. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32834921fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lind L, Andren B, Sundstrom J. The stroke volume/pulse pressure ratio predicts coronary heart disease mortality in a population of elderly men. J Hypertens. 2004;22(5):899–905. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis JF, Kuo LC, Nelson JG, Limacher MC, Quinones MA. Pulsed Doppler echocardiographic determination of stroke volume and cardiac output: clinical validation of two new methods using the apical window. Circulation. 1984;70(3):425–431. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.3.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teichholz LE, Kreulen TH, Herman MV. Problem in echocardiographic volume determinations; echo-angiographic correlations. Circulation. 1972;46(Supplement 2) doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teichholz LE, Cohen MV, Sonnenblick EH, Gorlin R. Study of left ventricular geometry and function by B-scan ultrasonography in patients with and without asynergy. N Engl J Med. 1974;291(23):1220–1226. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197412052912304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teichholz LE, Kreulen T, Herman MV, Gorlin R. Problems in echocardiographic volume determinations: echocardiographic-angiographic correlations in the presence of absence of asynergy. Am J Cardiol. 1976;37(1):7–11. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sweet RL, Moraski RE, Russell RO, Jr, Rackley CE. Relationship between echocardiography, cardiac output, and abnormally contracting segments in patients with ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 1975;52(4):634–641. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.52.4.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thiele H, Nagel E, Paetsch I, Schnackenburg B, Bornstedt A, Kouwenhoven M, Wahl A, Schuler G, Fleck E. Functional cardiac MR imaging with steady-state free precession (SSFP) significantly improves endocardial border delineation without contrast agents. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2001;14(4):362–367. doi: 10.1002/jmri.1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffmann R, von Bardeleben S, ten Cate F, Borges AC, Kasprzak J, Firschke C, Lafitte S, Al-Saadi N, Kuntz-Hehner S, Engelhardt M, Becher H, Vanoverschelde JL. Assessment of systolic left ventricular function: a multi-centre comparison of cineventriculography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, unenhanced and contrast-enhanced echocardiography. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(6):607–616. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehi083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dewey M, Muller M, Eddicks S, Schnapauff D, Teige F, Rutsch W, Borges AC, Hamm B. Evaluation of global and regional left ventricular function with 16-slice computed tomography, biplane cineventriculography, and two-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography: comparison with magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48(10):2034–2044. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.04.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim RJ, Fieno DS, Parrish TB, Harris K, Chen EL, Simonetti O, Bundy J, Finn JP, Klocke FJ, Judd RM. Relationship of MRI delayed contrast enhancement to irreversible injury, infarct age, and contractile function. Circulation. 1999;100(19):1992–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.19.1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fieno DS, Kim RJ, Chen EL, Lomasney JW, Klocke FJ, Judd RM. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of myocardium at risk: distinction between reversible and irreversible injury throughout infarct healing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(6):1985–1991. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00958-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hazirolan T, Tasbas B, Dagoglu MG, Canyigit M, Abali G, Aytemir K, Oto A, Balkanci F. Comparison of short and long axis methods in cardiac MR imaging and echocardiography for left ventricular function. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2007;13(1):33–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardner BI, Bingham SE, Allen MR, Blatter DD, Anderson JL. Cardiac magnetic resonance versus transthoracic echocardiography for the assessment of cardiac volumes and regional function after myocardial infarction: an intrasubject comparison using simultaneous intrasubject recordings. Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2009;7:38. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-7-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giakoumis A, Berdoukas V, Gotsis E, Aessopos A. Comparison of echocardiographic (US) volumetry with cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging in transfusion dependent thalassemia major (TM) Cardiovasc Ultrasound. 2007;5:24. doi: 10.1186/1476-7120-5-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Graham MM, Faris PD, Ghali WA, Galbraith PD, Norris CM, Badry JT, Mitchell LB, Curtis MJ, Knudtson ML. Validation of three myocardial jeopardy scores in a population-based cardiac catheterization cohort. Am Heart J. 2001;142(2):254–261. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.116481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang RM, Bierig M, Devereux RB, Flachskampf FA, Foster E, Pellikka PA, Picard MH, Roman MJ, Seward J, Shanewise JS, Solomon SD, Spencer KT, Sutton MS, Stewart WJ. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones EC, Devereux RB, Roman MJ, Liu JE, Fishman D, Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz RR, Howard BV. Prevalence and correlates of mitral regurgitation in a population-based sample (the Strong Heart Study) Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(3):298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(00)01362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zoghbi WA, Enriquez-Sarano M, Foster E, Grayburn PA, Kraft CD, Levine RA, Nihoyannopoulos P, Otto CM, Quinones MA, Rakowski H, Stewart WJ, Waggoner A, Weissman NJ. Recommendations for evaluation of the severity of native valvular regurgitation with two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2003;16(7):777–802. doi: 10.1016/S0894-7317(03)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Papavassiliu T, Kuhl HP, Schroder M, Suselbeck T, Bondarenko O, Bohm CK, Beek A, Hofman MM, van Rossum AC. Effect of endocardial trabeculae on left ventricular measurements and measurement reproducibility at cardiovascular MR imaging. Radiology. 2005;236(1):57–64. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2353040601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janik M, Cham MD, Ross MI, Wang Y, Codella N, Min JK, Prince MR, Manoushagian S, Okin PM, Devereux RB, Weinsaft JW. Effects of papillary muscles and trabeculae on left ventricular quantification: increased impact of methodological variability in patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. J Hypertens. 2008;26(8):1677–1685. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328302ca14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Codella NC, Cham MD, Wong R, Chu C, Min JK, Prince MR, Wang Y, Weinsaft JW. Rapid and accurate left ventricular chamber quantification using a novel CMR segmentation algorithm: a clinical validation study. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;31(4):845–853. doi: 10.1002/jmri.22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sievers B, Elliott MD, Hurwitz LM, Albert TS, Klem I, Rehwald WG, Parker MA, Judd RM, Kim RJ. Rapid detection of myocardial infarction by subsecond, free-breathing delayed contrast-enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Circulation. 2007;115(2):236–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.635409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hundley WG, Kizilbash AM, Afridi I, Franco F, Peshock RM, Grayburn PA. Administration of an intravenous perfluorocarbon contrast agent improves echocardiographic determination of left ventricular volumes and ejection fraction: comparison with cine magnetic resonance imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(5):1426–1432. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00409-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reilly JP, Tunick PA, Timmermans RJ, Stein B, Rosenzweig BP, Kronzon I. Contrast echocardiography clarifies uninterpretable wall motion in intensive care unit patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35(2):485–490. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00558-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurt M, Shaikh KA, Peterson L, Kurrelmeyer KM, Shah G, Nagueh SF, Fromm R, Quinones MA, Zoghbi WA. Impact of contrast echocardiography on evaluation of ventricular function and clinical management in a large prospective cohort. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(9):802–810. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sievers B, Kirchberg S, Bakan A, Franken U, Trappe HJ. Impact of papillary muscles in ventricular volume and ejection fraction assessment by cardiovascular magnetic resonance. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2004;6(1):9–16. doi: 10.1081/jcmr-120027800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Francois CJ, Fieno DS, Shors SM, Finn JP. Left ventricular mass: manual and automatic segmentation of true FISP and FLASH cine MR images in dogs and pigs. Radiology. 2004;230(2):389–395. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2302020761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weinsaft JW, Cham MD, Janik M, Min JK, Henschke CI, Yankelevitz DF, Devereux RB. Left ventricular papillary muscles and trabeculae are significant determinants of cardiac MRI volumetric measurements: effects on clinical standards in patients with advanced systolic dysfunction. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126(3):359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.04.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kronik G, Slany J, Mosslacher H. Comparative value of eight M-mode echocardiographic formulas for determining left ventricular stroke volume. A correlative study with thermodilution and left ventricular single-plane cineangiography. Circulation. 1979;60(6):1308–1316. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.6.1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Grande P, Pedersen A. Myocardial infarct size and cardiac performance at exercise soon after myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1982;47(1):44–50. doi: 10.1136/hrt.47.1.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Main ML, Ryan AC, Davis TE, Albano MP, Kusnetzky LL, Hibberd M. Acute mortality in hospitalized patients undergoing echocardiography with and without an ultrasound contrast agent (multicenter registry results in 4,300,966 consecutive patients) Am J Cardiol. 2008;102(12):1742–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Quinones MA, Douglas PS, Foster E, Gorcsan J, 3rd, Lewis JF, Pearlman AS, Rychik J, Salcedo EE, Seward JB, Stevenson JG, Thys DM, Weitz HH, Zoghbi WA, Creager MA, Winters WL, Jr, Elnicki M, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, Lorell BH, Rodgers GP, Tracy CM. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association clinical competence statement on echocardiography: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/American College of Physicians--American Society of Internal Medicine Task Force on Clinical Competence. Circulation. 2003;107(7):1068–1089. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000061708.42540.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Lieshout JJ, Toska K, van Lieshout EJ, Eriksen M, Walloe L, Wesseling KH. Beat-to-beat noninvasive stroke volume from arterial pressure and Doppler ultrasound. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;90(1–2):131–137. doi: 10.1007/s00421-003-0901-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]