Abstract

The contributions by blood cells to pathological venous thrombosis were only recently appreciated. Both platelets and neutrophils are now recognized as crucial for thrombus initiation and progression. Here we review the most recent findings regarding the role of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in thrombosis. We describe the biological process of NET formation (NETosis) and how the extracellular release of DNA and protein components of NETs, such as histones and serine proteases, contributes to coagulation and platelet aggregation. Animal models have unveiled conditions in which NETs form and their relation to thrombogenesis. Genetically engineered mice enable further elucidation of the pathways contributing to NETosis at the molecular level. Peptidylarginine deiminase 4, an enzyme that mediates chromatin decondensation, was identified to regulate both NETosis and pathological thrombosis. A growing body of evidence reveals that NETs also form in human thrombosis and that NET biomarkers in plasma reflect disease activity. The cell biology of NETosis is still being actively characterized and may provide novel insights for the design of specific inhibitory therapeutics. After a review of the relevant literature, we propose new ways to approach thrombolysis and suggest potential prophylactic and therapeutic agents for thrombosis.

Introduction

Neutrophils are an often underappreciated cell with crucial functions in immunity and injury repair. Because neutrophils are packed with microbicidal proteins and, when activated, generate high concentrations of reactive oxygen species, their ability to kill pathogens comes at a high cost to surrounding tissue. Indeed, when it comes to neutrophils, you certainly can have too much of a good thing. This became even more evident upon the discovery of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) by Brinkmann et al.1 NETs have been investigated in the context of host defense and also the pathogenesis of several noninfectious diseases. Here we will focus on the role of NETs in thrombosis.

Introduction to NETs

Pathogens can induce neutrophils to release chromatin lined with granular components (such as myeloperoxidase [MPO], neutrophil elastase, and cathepsin G),1,2 creating fibrous nets with antimicrobial properties, capable of killing both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.1 NETs also have the ability to trap and kill fungi,3 are released in viral infections,4 and can sequester viruses.5 Interestingly, this ability of the host to release extracellular traps to protect itself from pathogens is evolutionarily conserved in plants, with root border cells secreting extracellular DNA as part of a defense mechanism against bacterial and fungal infection.6

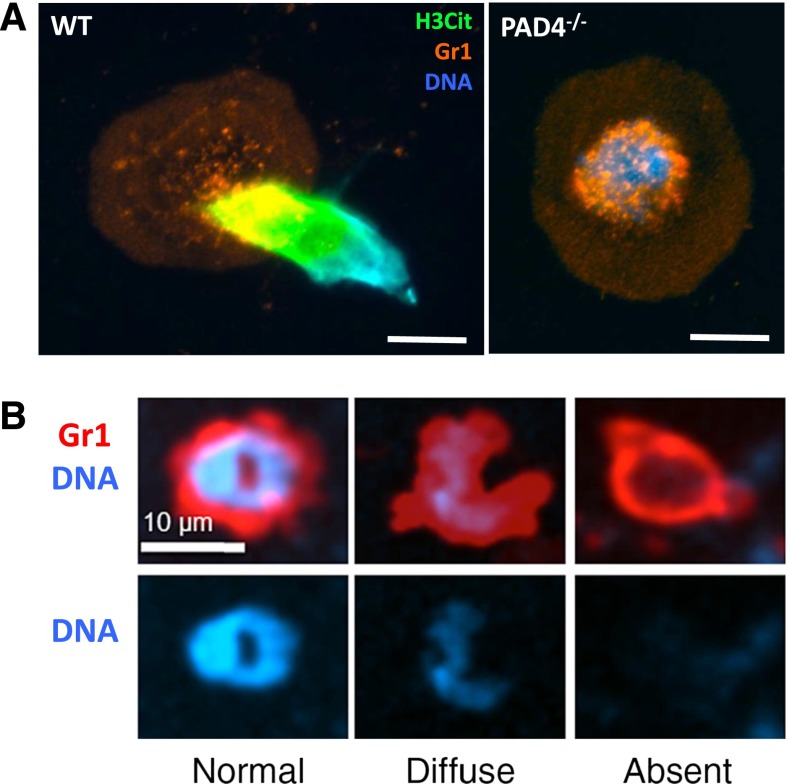

The cell biological mechanisms that allow for NET release are still being characterized. NETosis has been distinguished from apoptosis and necrosis as a new cell death process.7 In the study of Fuchs et al, the importance of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via reduced NAD phosphate (NADPH) oxidase was revealed.7 Because ROS are rapidly cell permeable, addition of exogenous sources of ROS can rescue deficiencies in NADPH oxidase.7 In the presence of some neutrophil stimuli, ROS may not be needed to form NETs.8-10 Crucial steps in NETosis were evaluated morphologically in early in vitro studies.7,11 First, the nucleus loses its characteristic lobular shape and swells. It is now known that the nuclear swelling is due to chromatin decondensation driven by peptidylarginine deiminase 4 (PAD4).12 PAD4 is a protein citrullinating enzyme that enters the nucleus to modify histones.12,13 During the hypercitrullination of specific arginine residues on histones H3 and H4, there is a loss of positive charge from the transformed arginine residues, and the linker histone H1 and heterochromatin protein 1β dissociate from the nucleosome structure.13,14 Overexpression of PAD4 results in chromatin decondensation and the release of NET-like structures in cells in vitro that do not normally undergo this form of cell death.14 Thus, activation of PAD4 is likely the primary driving force in NETosis. Neutrophils from PAD4−/− mice generated by the Wang group15 are completely unable to form NETs (Figure 1A). Therefore, PAD4−/− mice provide an excellent framework in which to study the role of NETs in vivo.15,16

Figure 1.

NETosis is a regulated process. (A) Representative image of a WT or PAD4−/− neutrophil stimulated with calcium ionophore. WT neutrophils undergo histone hypercitrullination (H3Cit, green) and throw NETs, whereas PAD4−/− neutrophils fail to citrullinate histones, decondense chromatin, or release NETs. Reproduced from Martinod et al.16 Scale bars, 10 μm. (B) In response to S aureus skin infection, neutrophils can secrete their nuclear contents (right) while retaining the ability to crawl and phagocytose, thus multitasking. Reproduced from Yipp et al with permission.19

It was proposed that some neutrophil granular enzymes such as neutrophil elastase translocate to the nucleus and help in chromatin decondensation by cleavage of histones.17 Genetic evidence determining to what extent individual granular proteins contribute to NETosis remains to be established. The serine protease inhibitor Serpin B1 may also regulate NET formation, and it also translocates into the nucleus.18 The timing of PAD4 activation, relative to the above mentioned enzymes’ nuclear translocation, and its own potential nuclear import still need to be characterized. Finally, the chromatin network is released into the extracellular milieu.1,7,11 What happens to the plasma membrane, cytoskeleton, and other organelles during NETosis is not known.

There is likely >1 mechanism of NET release. The process described above takes a fair amount of time (2-4 hours) before NETs are released.7 Recently, a second mechanism was observed first in vitro and then in vivo using intravital microscopy. Here, the neutrophils rapidly expel NETs (within minutes) in response to live Staphylococcus aureus.19,20 The neutrophil ejects either a portion or all of its decondensed nuclear contents (Figure 1B) without releasing the cytoplasmic contents or lysing the plasma membrane.19 The denucleated neutrophil still retains the ability to crawl and phagocytose bacteria trapped by its own NETs in a highly efficient process called vital NETosis.19,21 Large biologically active anuclear fragments of neutrophils were already observed in the 1980s.22 The mechanism by which nuclear contents are secreted in either process is yet unknown, as are the triggers that induce one form of NETosis over another.

While the beneficial effects of NETs in fighting pathogens were being reported,1,3,23 the pathological nature of NETs rapidly began to emerge. NET formation was observed in diseases without an obvious microbial trigger such as preeclampsia,24 small vessel vasculitis,25 and systemic lupus erythematosus and its associated nephritis.26 Defective serum DNases help to drive lupus pathogenesis, resulting in antibody production against self-DNA.26 Antibodies formed against NET components may promote the pathology of certain autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis.27 In addition, presence of antibodies to neutrophils may induce the formation of NETs such as in transfusion-related acute lung injury.28

There could be a benefit of intravascular NET formation in septic conditions where containing an overwhelming bacteremia is likely protective for the host.23,29 The large quantities of antimicrobial toxic products released with NETs, in particular histones, the main protein component of NETs,2 can contribute to lethality in sepsis.30 It appears that there is only a fine line between the beneficial and harmful effects of NETs for the infected host.

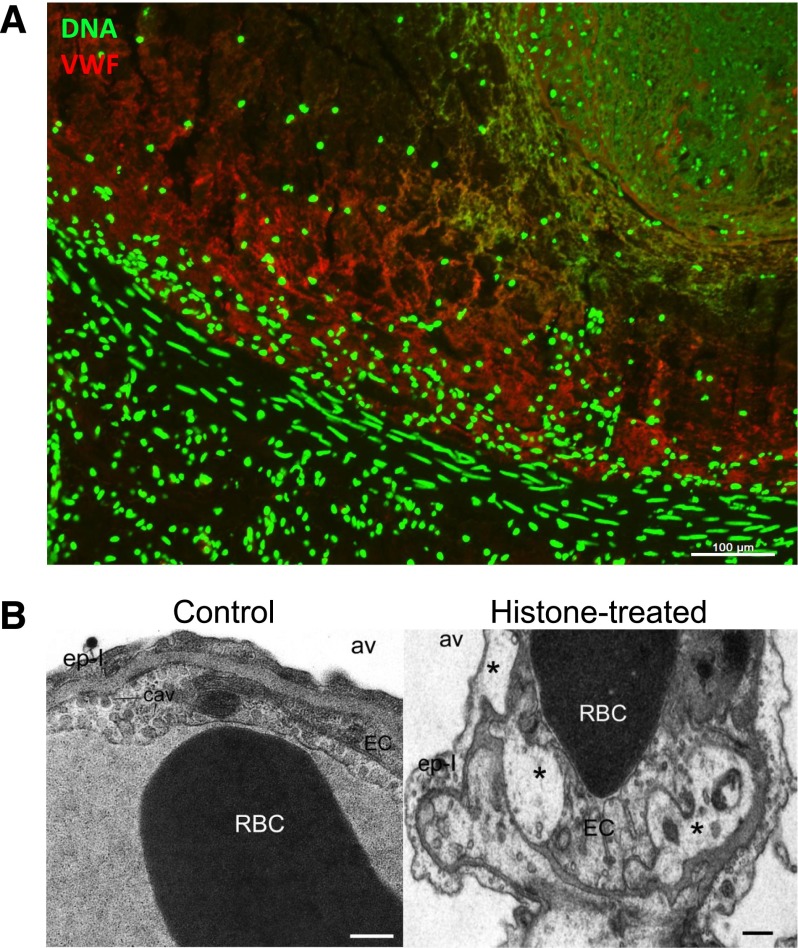

NETs not only entrap pathogens, they can also bind platelets and red blood cells (RBCs).31 Because RBC-rich red thrombi are formed in deep veins, it proved fruitful to first look for NETs in deep vein thrombosis (DVT).31 Indeed, the thrombus experimentally formed in a healthy baboon was full of extracellular DNA (Figure 2A). Infection is a risk factor for DVT,32 perhaps through the generation of NETs. The link between NETosis and coagulation was made because of the presence of neutrophil elastase (NE) on NETs. NE inactivates tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) through cleavage, thus resulting in increased procoagulant activity.33 Procoagulant activity leads to platelet activation and activated platelets can enhance NET formation,23,33,34 but platelet depletion does not necessarily prevent NETosis.28

Figure 2.

NETs are part of deep vein thrombi and histones produce toxicity in vivo. (A) A deep vein thrombus was formed in an otherwise healthy baboon by balloon catheterization. The thrombus was excised and analyzed for the presence of extracellular DNA (green) and von Willebrand factor (red), which were found to codistribute. Scale bar, 100 μm. Reproduced from Fuchs et al.31 (B) Intravenous histone infusion was detrimental to both endothelium and epithelium, as shown by vacuolization (stars) of these cells in and around the lung capillaries (right). Av, alveolae. Cav, caveolae. Ep-I, type I epithelial cell. EC, endothelial cell. Scale bars, 500 nm. Reproduced from Xu et al with permission.30

Nucleic acids, histones, and NET enzymes: effects on coagulation

Before the link to NETs was established, nucleic acids and nuclear components were studied individually for their ability to induce coagulation. Nucleic acids activate coagulation,35,36 with RNA binding both factor XII and XI in the intrinsic pathway. RNA is present in fibrin-rich arterial thrombi,35 but its origin is not known and whether RNA is released with NETs is still an open question. Also, histones increase thrombin generation37 in a platelet-dependent manner.38 Histones activate platelets,31 and platelet activation, in turn, promotes coagulation.39 Histone infusion leads to formation of platelet-rich microthrombi in a sepsis-like model30 while also contributing to thrombocytopenia.40 As noted earlier, infused histones are toxic and lead to endothelial and epithelial cell vacuolization (Figure 2B)30 and cell death,41 and this toxicity is mediated by Toll-like receptors 2 and 4.42 In vivo, histones likely circulate as part of nucleosomes.30,43 Intact nucleosomes/NETs promote coagulation and increase fibrin deposition.31,33 In vitro, the addition of DNA and histones in combination results in greater fibrin clot stability than the individual components.44

NETs deposition in a flow chamber perfused with blood promotes fibrin deposition and NETs bind plasma proteins important for platelet adhesion and thrombus propagation such as fibronectin and von Willebrand factor (VWF).31 In this flow model, RBCs bind to NETs but not collagen.31 Within thrombi formed in vivo, NETs colocalize with VWF.31 At times it appears as if VWF connects NETs to the vessel wall (Figure 2A). Interaction of NETs with fibrin was also observed after intraperitoneal administration of alum adjuvant resulting in the formation of nodules containing both extracellular DNA and fibrin,10 perhaps trying to encapsulate the foreign substance. Fibrin and NETs likely work together toward immune defense in a process now defined as immunothrombosis.45

NET fibers contain various other factors that can render them procoagulant. As mentioned earlier, serine proteases inhibit TFPI,46 and in addition, tissue factor has been shown to be deposited on NETs.34,47,48 The source of tissue factor could be from blood34 or from the vessel wall.49 Factor XII is present and active on NETs.33,34 The negatively charged DNA in NETs may provide a scaffold for Factor XII activation which is aided by platelets, but the exact mechanism has not been determined.34

NETs in thrombosis: animal models

Insights from animal models about the presence and role of NETs in thrombosis are extensive.50-52 The first analysis of baboons with thrombi from balloon catheter–induced DVT revealed the presence of NETs not only within the thrombus (Figure 2A) but also their biomarkers in the plasma,31 with their appearance paralleling that of the fibrin degradation product d-dimer.53 The mouse models of DVT have allowed for more detailed investigation of the time course of NET formation and the testing of potential therapies.34,54 Mouse models have also shown a possible role of NETs in arterial thrombosis.33

Arterial thrombosis

NETs have been studied in arterial vessel injury induced by ferric chloride application. In this model, the lack of serine proteases in neutrophil elastase/cathepsin G–deficient mice lessens coagulation via reduced TFPI cleavage.33 Infusion of the anti–H2A-H2B-DNA antibody55 that neutralizes histones leads to prolonged time to occlusion and lower thrombus stability in the carotid arteries of wild-type (WT) mice, whereas no effect of antibody infusion is observed in the neutrophil elastase/cathepsin G–deficient mice.33 Thus, externalized nucleosomes contribute to thrombogenesis by exposing serine proteases to TFPI. NETs are also present in the carotid lumen in ApoE-deficient mice on high-fat diet, proximal to atherosclerotic lesions,56 supporting the clinical observation that NETs are implicated in coronary atherosclerosis.57

DVT

Platelets and neutrophils are indispensible in the mouse inferior vena cava (IVC) stenosis model of DVT, as well as VWF that might help recruit both of these cell types.34,58 The release of VWF from Weibel-Palade bodies from endothelial cells is likely driven by hypoxia.59 Ischemic stroke also elevates plasma nucleosome levels, and systemic hypoxia produced by placing animals in a hypoxic chamber results in release of histone-DNA complexes into circulation.60 After a day in the hypoxic chamber, mice become highly susceptible to IVC thrombus formation.61 Interestingly, hypoxia induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), which is implicated in NETosis.62 Through their histones, NETs may further enhance endothelial activation as histone infusion in combination with IVC stenosis greatly accelerated thrombus formation.54 Histone infusion leads to VWF release54 and signs of microthrombosis in mice.30 Weibel-Palade body secretion also up-regulates endothelial P-selectin, an adhesion receptor for leukocytes.39 Neutrophils are among the first leukocytes to be recruited to the activated endothelium at the onset of thrombosis and comprise a great majority of the thrombus leukocytes during the early stages of thrombosis.34,63

Both the baboon and mouse models show NETs in close association with VWF within thrombi.31,54 In vitro binding of VWF to NETs is also observed.31 The interaction of the A1 domain of VWF with histones was originally described64 long before NETs were discovered, and these recent studies help to provide relevance to a phenomenon that was at the time found to have “no conceivable physiological role.”64 Similarly, fibronectin, a molecule important in thrombosis,65,66 contains 4 DNA-binding domains that also interact with heparin,67 and indeed fibronectin binds to NETs.31

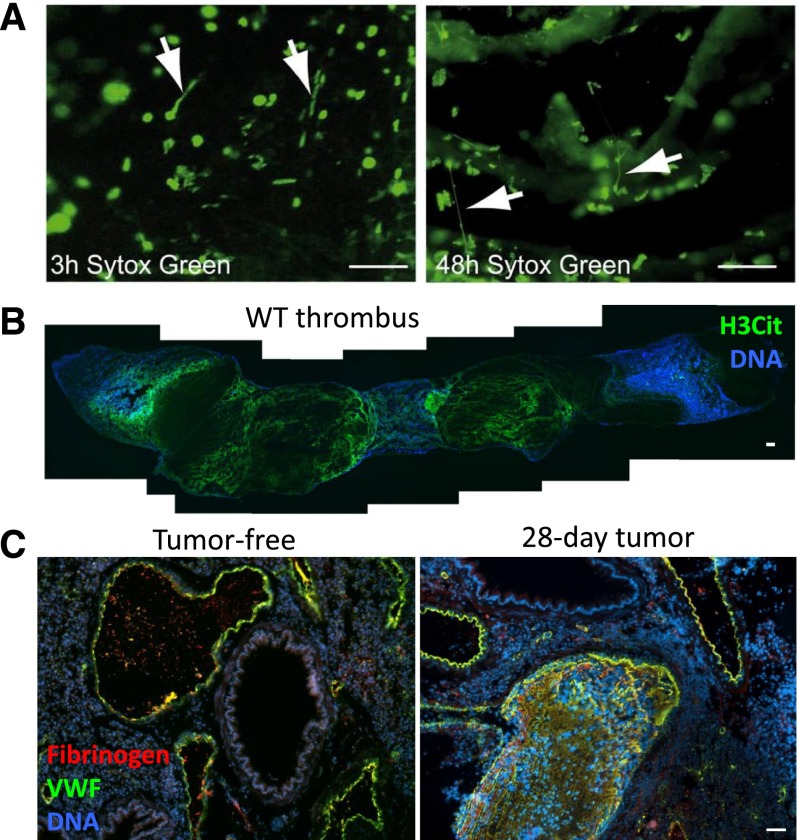

Although the presence of NETs within DVTs is undeniable, their importance in DVT pathophysiology is still being actively investigated. Treatment with DNase 1, known to degrade NETs,1 diminishes the frequency of thrombus formation,34,54 indicating that the presence of NETs in DVT is functionally important and that DNase could be therapeutically useful. At earlier time points after IVC stenosis, only a few NETs are present within the forming mouse thrombus as seen by intravital microscopy, whereas at later time points, NETs are widespread (Figure 3A).34 This was confirmed using citrullinated histone H3 as a marker for NETs,16 revealing an extensive meshwork of NETs throughout the 48-hour-old thrombus (Figure 3B). The use of PAD4−/− mice, which cannot undergo the histone modification required for chromatin decondensation in NETosis, demonstrated that NETs are indeed a crucial component of the thrombus scaffold, as the lack of NETs results in fewer thrombi early after IVC stenosis (6 hours), with almost no thrombi present after 48 hours.16 In PAD4−/− mice, platelets and leukocytes do accumulate along activated endothelium, and neutrophils are present within the rare thrombi that form,16 showing that NETosis is the critical function of neutrophils in thrombosis. CXCL7 released from platelets in thrombi may generate the chemotactic gradient that directs leukocytes within thrombi,68 and platelets also promote NETosis34 through a mechanism that is not completely elucidated.23,33,34

Figure 3.

NETs form in mouse models of thrombosis and cancer. (A) Intravital microscopy of developing thrombi shows the release of NETs early (3 hours) and more prominently in occlusive thrombi (48 hours). Arrows indicate NETs. Sytox Green, DNA. Scale bars, 50 μm. Reproduced from von Bruhl et al.34 (B) Composite image of a thrombus formed in a WT mouse 48 hours after IVC stenosis. Mosaic generated using MosaicJ plug-in for ImageJ software.126 Citrullinated histone H3 (H3Cit) staining (green) shows evidence of a NET meshwork throughout the red portion of the thrombus. Scale bar, 100 μm. (C) Mice bearing a mammary carcinoma develop spontaneous thrombi in the lung (right) after 28 days, a time point when NETs are spontaneously generated in these mice. This does not occur in tumor-free mice (left). VWF, green. Fibrinogen, red. DNA, blue. Scale bar, 50 μm. Reproduced from Demers et al.71

Venous injury

There may be a difference between arterial and venous responses to injury with respect to NETs. In contrast to the arterial injury model,33 in venous ferric chloride injury, there is no delay in time to occlusive thrombus formation in PAD4−/− mice where NETosis is inhibited.16 Alternatively, the importance of NETs may depend on vessel size. Arterial injury was examined in the carotid artery,33 which takes longer to occlude than injury of small veins16 and thus NETs have the time to be produced. In large arteries, NETs may be necessary in addition to fibrin to stabilize the thrombus against arterial shear. Importantly, the PAD4−/− mice retain normal tail bleeding time. Therefore, NETs may not play a critical role in platelet plug formation in response to a small injury. They could, however, provide long-term stability of thrombi in large wounds but this is yet to be investigated. Targeting PAD4 may be beneficial in pathological venous thrombosis because it will not cause spontaneous hemorrhaging or have drastic consequences on physiological hemostasis.

Cancer-associated thrombosis

A high percentage of cancer patients both with and without chemotherapy experience lethal thrombotic complications.69 Cell-free DNA increases transiently during the course of chemotherapy in patients and in a mouse model.70 Adding cell-free DNA isolated from in vitro chemotherapy-treated blood to recalcified plasma increases thrombin generation due to contact pathway activation.70 Mice bearing solid tumors develop an accompanied neutrophilia during tumor progression. In mammary carcinoma and Lewis lung carcinoma, this is associated with increasing plasma DNA levels.71 Of note, when cancer patients develop neutrophilia, this is usually a sign of poor prognosis.72 Isolated neutrophils from tumor-bearing mice are primed to undergo NETosis.71 It is thought that tumors secrete cytokines, such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor, that systemically prime the neutrophils.71,73 The elevated DNA and propensity of neutrophils to throw NETs provides a new explanation for cancer-associated thrombosis, as mice with high levels of NET biomarkers, such as plasma H3Cit, show spontaneous thrombosis (Figure 3C).71

NETs in human thrombosis

Although NETs were initially described as occurring within tissues,1,24,74 subsequent work has shown they can form within vasculature.23,31,33 This may increase the ability to measure certain biomarkers of NETs in plasma. Indeed, DNA75 and nucleosomes76 are elevated in septic patients, and cell-free DNA levels were a better predictor of progression to sepsis after traumatic injury than interleukin-6 or C-reactive protein, markers of inflammation.77 MPO-DNA complexes are elevated specifically during active disease in patients with small-vessel vasculitis,25 when their thrombotic risk is the highest.78 Also, a case study in a patient with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-positive microscopic polyangiitis showed NETs within a venous thrombus.79 Thrombotic risk is elevated in other chronic diseases in which NETs form, including cancer, colitis, and rheumatoid arthritis.

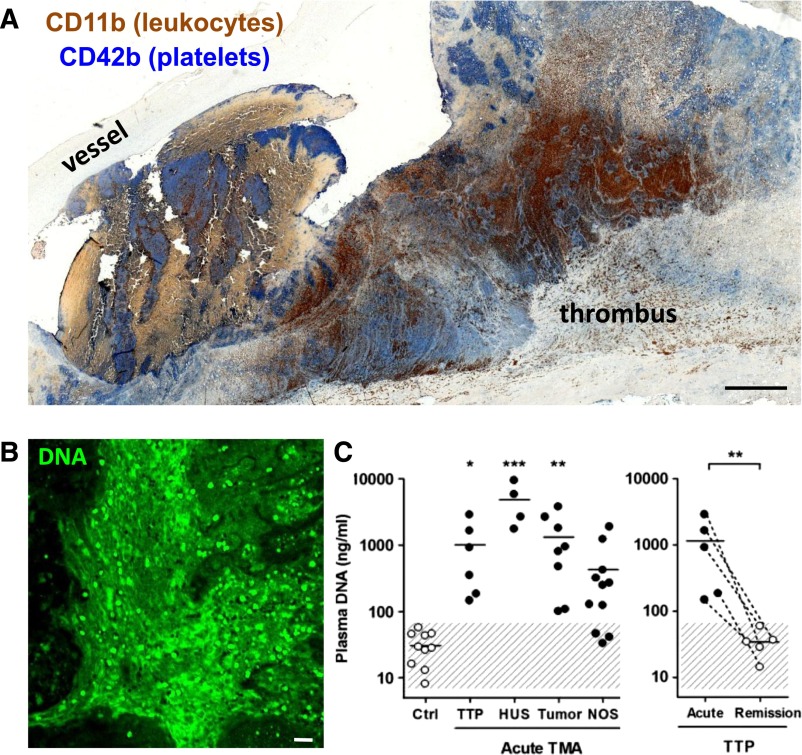

The interplay of inflammation and thrombosis is well established. In coronary artery disease, MPO-DNA complexes are elevated in the more severe cases, positively associated with elevated thrombin levels, and robustly predict adverse cardiac events.57 DNA, nucleosome, and MPO levels correlate with disease state in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies (TMAs), including thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome, and malignant tumor-induced TMA.80 In TTP characterized by low ADAMTS13 (a disintegrin-like and metalloproteinase with thrombospondin type-1 motifs 13), NET biomarkers are elevated during acute TTP compared with the same patients in remission (Figure 4C),80 making it a possibility that the disease could be precipitated by an infection or other stimulus that induces NETosis. Circulating NET levels can be used to predict which patients will develop TMAs after bone marrow transplant.81 Blood products may also contain NETs if not leukodepleted prior to transfusion.82 These infused NETs could be toxic after transfusion and may possibly contribute to thrombotic events in hospitalized patients.

Figure 4.

Evidence of NETs in human pathological thrombosis. (A) Composite image of a human pulmonary embolism specimen obtained surgically and stained by immunohistochemistry for platelets (blue) and leukocytes (brown) showing that areas of the thrombus are rich in both cell types. Scale bar, 100 μm. Mosaic generated using MosaicJ plug-in for ImageJ.126 Immunohistochemical analysis by Alexander Savchenko. (B) Representative image of diffuse extracellular DNA staining (green) present in a surgically harvested pulmonary embolism patient specimen. Green, DNA. Scale bar, 20 μm. Anonymous specimens in A and B kindly provided by Richard Mitchell. Most recently, specimens from 11 additional patients were evaluated and biomarkers of NETs were predominantly found in the organizing stage of human venous thromboembolism.127 (C) Cell-free DNA, a plasma biomarker of NETs, is elevated in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies (left): thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), malignancies (tumor), and nonspecified cases (NOS). Patients suffering from acute TTP present significantly elevated plasma DNA compared with when in remission (right). This research was originally published in Blood. Fuchs TA et al. Circulating DNA and myeloperoxidase indicate disease activity in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies. Blood. 2012;120:1157-1164. © American Society of Hematology. Human thrombus samples were obtained by the Wagner Laboratory from Dr Richard N. Mitchell (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA) as anonymous tissue specimens. Dr Mitchell's work was approved by Brigham and Women's Hospital Institutional Review Board 2013P000231.

Risk factors for DVT include trauma, surgery, infection, immobilization, and hypoxia,32,83,84 several of which are associated with NET formation. DVTs and pulmonary emboli have regions of platelet and leukocyte accumulation (Figure 4A), and unpublished observations from our laboratory show that these are also rich in extracellular DNA (Figure 4B). Establishing suitable biomarkers for DVT diagnosis is of interest, because for now ultrasound remains the best diagnostic method but is not always reliable.85 Circulating nucleosomes and markers of neutrophil activation (elastase-α1-antitrypsin and MPO) are significantly increased in persons with DVT, compared with patients with symptoms but lack of confirmed DVT diagnosis.86,87 Plasma DNA positively correlates with VWF and negatively correlates with levels of ADAMTS13,87 supporting a relationship between NETs and VWF in DVT. In fact, the ratio of ADAMTS13 to VWF is the lowest in DVT patients.87

Extracellular histone/DNA complexes have also been identified in arterial thrombi following thromboectomy44,88 obtained from abdominal aortic aneurism patients.88 The codistribution of fibrin and NETs is apparent in arterial thrombi.44 Combination therapies digesting fibrin and DNA may be needed for efficient thrombolysis31 (Figure 5), as will be discussed below.

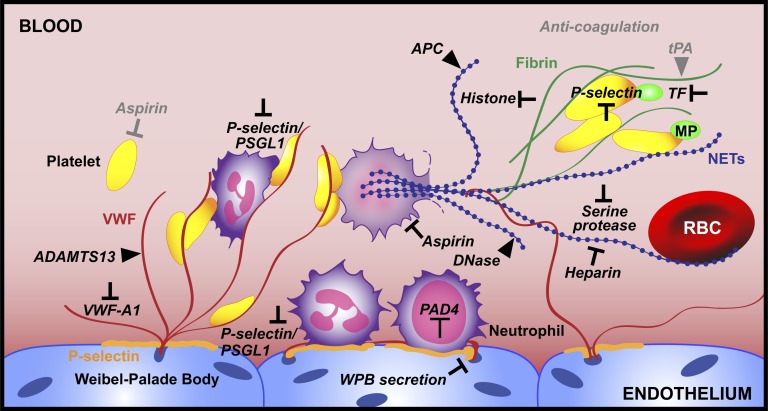

Figure 5.

Emerging targets for thrombus prevention and thrombolysis. Here we summarize advances in the field of thrombosis with respect to neutrophil recruitment and NETosis and pinpoint targets that should be investigated as potential therapeutics (black). Existing treatments are in gray. We propose PAD4 inhibition as a way to prevent NET release. For thrombi that have already formed, neutralizing the toxic components of NETs is key. Thrombolytic strategies should involve the targeting of both DNA (blue) and the protein elements (red and green) of the thrombus scaffold.

New possibilities to prevent thrombosis and improve thrombolysis

Thrombus development involves an ongoing process of maturation.89 Animal models of DVT have established a time course of initial neutrophil and platelet recruitment followed by monocyte infiltration and eventual thrombus resolution.34,58,90,91 There are several potential new targets for either the prevention of thrombosis or enhancement of thrombolysis (Figure 5). Platelets and platelet adhesion to VWF are essential to thrombus generation,34,58 and 2 recent clinical trials showed that aspirin, long regarded as an antiplatelet therapy, prevents venous thromboembolism recurrence.92,93 Interestingly, aspirin can also inhibit NETosis in vitro.94 Preventing Weibel-Palade body release, for example with agents that increase nitric oxide generation95 or otherwise interfere with endothelial VWF/P-selectin secretion,96 or targeting platelet-VWF interactions would both prevent platelets and neutrophils from tethering onto the vessel wall and their possible recruitment of other platelets and neutrophils on activation. The A1 domain of VWF binds to glycoprotein Iβ on platelets, promoting their adhesion. In vivo, inhibition of this interaction targeting the VWF A1 domain by antibodies or aptamers 97,98 greatly reduces thrombus formation in arteries and veins.58,98 Inhibiting VWF would prevent P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 (PSGL-1)-mediated leukocyte rolling and also firm adhesion via β2 integrins such as Mac1.99 ADAMTS13, a protease that specifically cleaves VWF,100 can be administered in vivo to reduce thrombosis101 and to aid in thrombolysis of thrombi in venules.102 Recombinant ADAMTS13 (rADAMTS13) can prevent microthrombosis such as in ischemia reperfusion injury occurring in myocardial infarction or stroke.103,104 rADAMTS13 could also be used in DVT prophylaxis by reducing initial platelet accumulation and neutrophil recruitment, as well as in aiding thrombolysis in combination with fibrinolytic or NET-degrading therapies. Some improvement after combining ADAMTS13 and DNase 1 was observed in a murine myocardial ischemia/reperfusion model.105 It is of interest to note that polymorphisms in both ADAMTS13 and DNase 1 linked to reduced activity are associated with myocardial infarction in humans.106,107

Targeting P-selectin, the other important component of Weibel-Palade bodies and α-granules, is triply beneficial, as it reduces neutrophil recruitment, the activating interaction between neutrophils and platelets, and the generation of TF-containing microparticles.39 P-selectin inhibition is protective in DVT animal models,34,53,63,108 significantly reducing neutrophil recruitment to the vessel wall,34,63 NET generation,34 and reducing the procoagulant activity of P-selectin.108,109 The ideal antithrombotic agent will prevent pathological thrombosis with minimal impact on hemostasis. In this respect, neutrophils are such a target. Neutrophil depletion was reported to reduce thrombus size in mouse DVT,34 and this is likely due to their ability to make NETs through the action of PAD4.16 PAD4 inhibitors would prevent NETs from being formed, while DNases could be used to degrade NETs that are already present (Figure 5). A variety of nucleases could be tested for thrombolysis, perhaps even ones of bacterial origin as streptokinase effectively digests fibrin.

Central to the feasibility of NETs degradation is their structure: they are strands of highly decondensed chromatin exposed to the extracellular environment and thus accessible to DNases.1,2 Certain pathogens produce nucleases that allow them to evade capture and killing by NETs.74,110,111 Such nucleases may be good candidates to improve thrombolysis. Administration of DNase I has a protective effect in vivo in murine models of ischemic stroke,60 myocardial infarction,105 and DVT.34,54 Combination therapies including DNase with ADAMTS13 and/or tissue plasminogen activator could allow for more complete penetration of thrombolytic agents within large thrombi. Current therapies are centered on anticoagulation and fibrinolysis112 that, with the exception of heparin (see below), are unlikely to dismantle or degrade the NET component of the venous thrombus scaffold. Indeed, clots produced with NETosing neutrophils could only be degraded with a combination of tissue plasminogen activator and DNase I.31 Similarly, addition of histones and DNA to fibrin clots in vitro makes them more resistant to fibrinolysis.44

Interestingly, the widely used anticoagulant heparin dismantles NETs31 and prevents histone-platelet interactions,40 thus likely decreasing NET-driven thrombosis. DNase I activity on chromatin is enhanced in vitro by the presence of serine proteases, and this can be mimicked by heparin as it dislodges histones from chromatin and allows for greater accessibility for the enzyme.113 Combining DNase 1 with heparin could further reduce the risk of future thrombotic events.

Neutralizing the toxic components of NETs provides another possible strategy to prevent endothelial injury and thrombosis. Activated protein C degrades histones and prevents histone-associated lethality.30 In mice, infusion of histones precipitates DVT54 and exacerbates ischemic stroke.60 Inhibiting the serine proteases on NETs could allow for TFPI activity and decreased TF-promoted coagulation.33 TF is found on NETs,34 and it is likely that TF-containing microparticles are recruited to NETs or NET-associated platelets. Reducing these procoagulant factors would mitigate the damaging effects of NETs until their eventual clearance.

It is likely that macrophages infiltrating the thrombus can act as an endogenous clearance mechanism of NETs during thrombus resolution. Macrophages are able to phagocytose NETs and degrade them with their high lysosomal DNase II contents.114 In vitro, DNase I preliminary digestion aids the clearance of NETs by macrophages.114 Addition of exogenous DNase 1 could enhance the accessibility of macrophages to NETs and the removal of fragmented NETs. Monocytes/macrophages also provide plasminogen activator,115 thus helping fibrinolysis. Any potential antithrombotic should not negatively impact macrophage function as this could impede thrombus resolution and result in pathologies from excess NET products.

Questions for the future

From the observations described above, it is clear that inhibiting NETosis would be beneficial to prevent toxic side effects of NETs in inflammation and reduce occurrence of pathological thrombosis. However, the importance of NETs in preventing infection cannot be neglected and needs more thorough evaluation. NETs alone29 or together with fibrin33 may wall off local infections and prevent dissemination,45 which could be promoted by DNase/fibrinolysis. Because PAD4-deficient neutrophils are competent in phagocytosis,15 ROS generation and recruitment to inflammatory sites (K.M. and D.D.W., unpublished data, 2013), it is possible that only an overwhelming infection would be problematic when NETosis is inhibited. Although PAD4−/− mice were more susceptible to a mutant group A streptococcal infection (unable to secrete a nuclease), PAD4−/− mice did not fare worse in necrotizing fasciitis induced by the DNase-secreting group A Streptococcus.15 Also, PAD4−/− mice were similar to WT in influenza infection.116 We thus do not anticipate major problems in treating an uninfected host. Antibiotics could be administered together with the NETosis inhibitors when needed.

Assuming NET inhibition is safe, it will be important to examine at which step NETosis is best arrested. The original stimulus and the signaling mechanisms leading to chromatin release during thrombosis need to be uncovered. Hypoxia and its activation of the transcription factor HIF-1α were implicated in NETosis62 and ROS generation could also be important. Whether DVT is modified in mice deficient in HIF1α and mutants that overproduce or underproduce ROS should be evaluated. Interaction of platelets with neutrophils promotes NETosis, and there may be an enhancing effect by the forming clot itself. Fibronectin, present in clots, was shown to have such an effect.9 We noted that NETs were mostly present in the RBC-rich (red) portion of the clot.54 RBCs may not only be recruited by NETs, but may also enhance their production. Whether inhibition of any of these interactions would reduce NETosis remains to be seen.

Little is known about the signaling inside the cell that leads to chromatin release. Raf/MEK/ERK (Raf mitogen-activated protein kinase [MAPK]/extracellular signal-related kinase [ERK] kinase),117 Rac2 (Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 2),118 and NADPH oxidase7 can participate. Which of these are implicated in pathological thrombosis such as DVT should be determined and tested with available inhibitors. What are the signals that direct neutrophils to either release only nuclear components or the entire cell contents? Which of these NETosis mechanisms is more common in thrombosis? Are the neutrophils within thrombi that have formed NETs dead or do they retain function? Does partial chromatin release19 occur during thrombosis, serving to enhance neutrophil adhesion to other cells within thrombi? Most importantly, learning more about PAD4, a key therapeutic target candidate, its intracellular substrates other than histones, and how it is activated or translocated to the nucleus may help to design inhibitors with high specificity.

It will be instructive to determine the implications of NET formation on thrombotic disease progression and as a biomarker of disease activity. What is the exact role of NETs in thrombosis? Do they contribute to thrombus stability like fibrin?65 Are they implicated in post-thrombotic syndrome? NETs may play a role in vessel wall injury and recruitment of new cell types into the thrombus, including endothelial cells for thrombus vascularization. During thrombosis, NETs fragments appear in circulation.31,54 These may be useful biomarkers of active thrombotic disease31,86,87 and should be studied carefully as they may reveal more about the process of NETs generation and degradation. Furthermore, it will be critical to know how long these NETs fragments retain procoagulant activity and how this depends on their size or composition. We know that NET generation in diseases such as cancer has a systemic effect on the host,71 and the procoagulant activity generated by NETs could promote cancer growth as is the case with thrombin.119

It will be important to learn how NETs and their fragments are naturally cleared. Animal studies indicate that it would be therapeutically beneficial to clear NETs from the circulation and away from vessel walls. Is VWF implicated in anchoring NETs to the vessel wall, and would ADAMTS13 free the NETs? VWF and DNA plasma levels seem to correlate in human thrombosis.87 Except for macrophages, with their intracellular DNase II,114 and dendritic cells,120-122 no other cell type has been implicated in NET clearance. The role of platelets and RBCs that bind NETs should be evaluated. DNase I is elevated after ischemia123 and also early in sepsis124: is this to reduce the risk of thrombosis? DNase I−/− mice should be studied to further examine the enzyme’s role in NET clearance114 and as a natural thrombolytic.

In conclusion, we have learned a lot about NETs activity in thrombotic disease since the first observation in 2010 of their presence in a DVT. There is certainly plenty more to investigate. Now is the time to test the effect of NET inhibition in DVT prophylaxis and of combination therapies in thrombolysis, therapies that not only cleave the proteinaceous components of thrombi, but also attack the nucleic acid backbone.

We just saw it from a different point of view

Tangled up in blue125

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Melanie Demers and Siu Ling Wong for helpful discussions, Richard N. Mitchell for providing human pulmonary embolism specimens, and Alexander S. Savchenko for immunohistochemical analysis of human samples. The authors also thank Lesley Cowan for assistance in manuscript preparation and Kristin Johnson for graphic design of Figure 5.

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants R01HL095091, R01HL041002, and R01HL102101 (to D.D.W.).

Authorship

Contribution: K.M. and D.D.W. wrote the review.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Denisa D. Wagner, Boston Children’s Hospital, 3 Blackfan Circle, Third Floor, Boston, MA 02115; denisa.wagner@childrens.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Urban CF, Ermert D, Schmid M, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps contain calprotectin, a cytosolic protein complex involved in host defense against Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5(10):e1000639. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Urban CF, Reichard U, Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps capture and kill Candida albicans yeast and hyphal forms. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8(4):668–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00659.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Narasaraju T, Yang E, Samy RP, et al. Excessive neutrophils and neutrophil extracellular traps contribute to acute lung injury of influenza pneumonitis. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(1):199–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saitoh T, Komano J, Saitoh Y, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate a host defense response to human immunodeficiency virus-1. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(1):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hawes MC, Curlango-Rivera G, Wen F, White GJ, Vanetten HD, Xiong Z. Extracellular DNA: the tip of root defenses? Plant Sci. 2011;180(6):741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2011.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs TA, Abed U, Goosmann C, et al. Novel cell death program leads to neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2007;176(2):231–241. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen K, Nishi H, Travers R, et al. Endocytosis of soluble immune complexes leads to their clearance by FcγRIIIB but induces neutrophil extracellular traps via FcγRIIA in vivo. Blood. 2012;120(22):4421–4431. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-401133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Byrd AS, O’Brien XM, Johnson CM, Lavigne LM, Reichner JS. An extracellular matrix-based mechanism of rapid neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Candida albicans. J Immunol. 2013;190(8):4136–4148. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Munks MW, McKee AS, Macleod MK, et al. Aluminum adjuvants elicit fibrin-dependent extracellular traps in vivo. Blood. 2010;116(24):5191–5199. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-275529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Beneficial suicide: why neutrophils die to make NETs. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5(8):577–582. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang Y, Li M, Stadler S, et al. Histone hypercitrullination mediates chromatin decondensation and neutrophil extracellular trap formation. J Cell Biol. 2009;184(2):205–213. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200806072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang Y, Wysocka J, Sayegh J, et al. Human PAD4 regulates histone arginine methylation levels via demethylimination. Science. 2004;306(5694):279–283. doi: 10.1126/science.1101400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leshner M, Wang S, Lewis C, Zheng H, Chen XA, Santy L, Wang Y. PAD4 mediated histone hypercitrullination induces heterochromatin decondensation and chromatin unfolding to form neutrophil extracellular trap-like structures. Front Immunol. 2012;3:307. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2010;207(9):1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martinod K, Demers M, Fuchs TA, et al. Neutrophil histone modification by peptidylarginine deiminase 4 is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(21):8674–8679. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1301059110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Papayannopoulos V, Metzler KD, Hakkim A, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil elastase and myeloperoxidase regulate the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Cell Biol. 2010;191(3):677–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201006052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farley K, Stolley JM, Zhao P, Cooley J, Remold-O’Donnell E. A serpinB1 regulatory mechanism is essential for restricting neutrophil extracellular trap generation. J Immunol. 2012;189(9):4574–4581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yipp BG, Petri B, Salina D, et al. Infection-induced NETosis is a dynamic process involving neutrophil multitasking in vivo. Nat Med. 2012;18(9):1386–1393. doi: 10.1038/nm.2847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pilsczek FH, Salina D, Poon KK, et al. A novel mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J Immunol. 2010;185(12):7413–7425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yipp BG, Kubes P. NETosis: how vital is it? Blood. 2013;122(16):2784–2794. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-457671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Malawista SE, De Boisfleury Chevance A. The cytokineplast: purified, stable, and functional motile machinery from human blood polymorphonuclear leukocytes. J Cell Biol. 1982;95(3):960–973. doi: 10.1083/jcb.95.3.960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clark SR, Ma AC, Tavener SA, et al. Platelet TLR4 activates neutrophil extracellular traps to ensnare bacteria in septic blood. Nat Med. 2007;13(4):463–469. doi: 10.1038/nm1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta AK, Hasler P, Holzgreve W, Gebhardt S, Hahn S. Induction of neutrophil extracellular DNA lattices by placental microparticles and IL-8 and their presence in preeclampsia. Hum Immunol. 2005;66(11):1146–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2005.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessenbrock K, Krumbholz M, Schönermarck U, et al. Netting neutrophils in autoimmune small-vessel vasculitis. Nat Med. 2009;15(6):623–625. doi: 10.1038/nm.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hakkim A, Fürnrohr BG, Amann K, et al. Impairment of neutrophil extracellular trap degradation is associated with lupus nephritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(21):9813–9818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909927107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dwivedi N, Upadhyay J, Neeli I, et al. Felty’s syndrome autoantibodies bind to deiminated histones and neutrophil extracellular chromatin traps. Arthritis Rheum. 2012;64(4):982–992. doi: 10.1002/art.33432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thomas GM, Carbo C, Curtis BR, et al. Extracellular DNA traps are associated with the pathogenesis of TRALI in humans and mice. Blood. 2012;119(26):6335–6343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald B, Urrutia R, Yipp BG, Jenne CN, Kubes P. Intravascular neutrophil extracellular traps capture bacteria from the bloodstream during sepsis. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12(3):324–333. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu J, Zhang X, Pelayo R, et al. Extracellular histones are major mediators of death in sepsis. Nat Med. 2009;15(11):1318–1321. doi: 10.1038/nm.2053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Duerschmied D, et al. Extracellular DNA traps promote thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107(36):15880–15885. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005743107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smeeth L, Cook C, Thomas S, Hall AJ, Hubbard R, Vallance P. Risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after acute infection in a community setting. Lancet. 2006;367(9516):1075–1079. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68474-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Massberg S, Grahl L, von Bruehl ML, et al. Reciprocal coupling of coagulation and innate immunity via neutrophil serine proteases. Nat Med. 2010;16(8):887–896. doi: 10.1038/nm.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.von Brühl ML, Stark K, Steinhart A, et al. Monocytes, neutrophils, and platelets cooperate to initiate and propagate venous thrombosis in mice in vivo. J Exp Med. 2012;209(4):819–835. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kannemeier C, Shibamiya A, Nakazawa F, et al. Extracellular RNA constitutes a natural procoagulant cofactor in blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(15):6388–6393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608647104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Altincicek B, Stötzel S, Wygrecka M, Preissner KT, Vilcinskas A. Host-derived extracellular nucleic acids enhance innate immune responses, induce coagulation, and prolong survival upon infection in insects. J Immunol. 2008;181(4):2705–2712. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.4.2705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ammollo CT, Semeraro F, Xu J, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones increase plasma thrombin generation by impairing thrombomodulin-dependent protein C activation. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(9):1795–1803. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Semeraro F, Ammollo CT, Morrissey JH, Dale GL, Friese P, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones promote thrombin generation through platelet-dependent mechanisms: involvement of platelet TLR2 and TLR4. Blood. 2011;118(7):1952–1961. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-343061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner DD, Frenette PS. The vessel wall and its interactions. Blood. 2008;111(11):5271–5281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-078204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fuchs TA, Bhandari AA, Wagner DD. Histones induce rapid and profound thrombocytopenia in mice. Blood. 2011;118(13):3708–3714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-332676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saffarzadeh M, Juenemann C, Queisser MA, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps directly induce epithelial and endothelial cell death: a predominant role of histones. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e32366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu J, Zhang X, Monestier M, Esmon NL, Esmon CT. Extracellular histones are mediators of death through TLR2 and TLR4 in mouse fatal liver injury. J Immunol. 2011;187(5):2626–2631. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esmon CT. Molecular circuits in thrombosis and inflammation. Thromb Haemost. 2013;109(3):416–420. doi: 10.1160/TH12-08-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Longstaff C, Varjú I, Sótonyi P, et al. Mechanical stability and fibrinolytic resistance of clots containing fibrin, DNA, and histones. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(10):6946–6956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.404301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Engelmann B, Massberg S. Thrombosis as an intravascular effector of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(1):34–45. doi: 10.1038/nri3345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen LC, Bjørn SE, Nordfang O. Effect of leukocyte proteinases on tissue factor pathway inhibitor. Thromb Haemost. 1992;67(5):537–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kambas K, Chrysanthopoulou A, Vassilopoulos D, et al. Tissue factor expression in neutrophil extracellular traps and neutrophil derived microparticles in antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody associated vasculitis may promote thromboinflammation and the thrombophilic state associated with the disease [published online ahead of print July 19, 2013]. Ann Rheum Dis. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kambas K, Mitroulis I, Apostolidou E, et al. Autophagy mediates the delivery of thrombogenic tissue factor to neutrophil extracellular traps in human sepsis. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(9):e45427. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0045427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hampton AL, Diaz JA, Hawley AE, et al. Myeloid cell tissue factor does not contribute to venous thrombogenesis in an electrolytic injury model. Thromb Res. 2012;130(4):640–645. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fuchs TA, Brill A, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) impact on deep vein thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(8):1777–1783. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.242859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gardiner EE, Andrews RK. Neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) and infection-related vascular dysfunction. Blood Rev. 2012;26(6):255–259. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lester PA, Diaz JA, Shuster KA, Henke PK, Wakefield TW, Myers DD. Inflammation and thrombosis: new insights. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2012;4:620–638. doi: 10.2741/s289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Meier TR, Myers DD, Jr, Wrobleski SK, et al. Prophylactic P-selectin inhibition with PSI-421 promotes resolution of venous thrombosis without anticoagulation. Thromb Haemost. 2008;99(2):343–351. doi: 10.1160/TH07-10-0608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2012;10(1):136–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Losman MJ, Fasy TM, Novick KE, Monestier M. Monoclonal autoantibodies to subnucleosomes from a MRL/Mp(-)+/+ mouse. Oligoclonality of the antibody response and recognition of a determinant composed of histones H2A, H2B, and DNA. J Immunol. 1992;148(5):1561–1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Megens RT, Vijayan S, Lievens D, et al. Presence of luminal neutrophil extracellular traps in atherosclerosis. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107(3):597–598. doi: 10.1160/TH11-09-0650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Borissoff JI, Joosen IA, Versteylen MO, et al. Elevated levels of circulating DNA and chromatin are independently associated with severe coronary atherosclerosis and a prothrombotic state. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(8):2032–2040. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brill A, Fuchs TA, Chauhan AK, et al. von Willebrand factor-mediated platelet adhesion is critical for deep vein thrombosis in mouse models. Blood. 2011;117(4):1400–1407. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-287623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pinsky DJ, Naka Y, Liao H, et al. Hypoxia-induced exocytosis of endothelial cell Weibel-Palade bodies. A mechanism for rapid neutrophil recruitment after cardiac preservation. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(2):493–500. doi: 10.1172/JCI118440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Meyer SF, Suidan GL, Fuchs TA, Monestier M, Wagner DD. Extracellular chromatin is an important mediator of ischemic stroke in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32(8):1884–1891. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.250993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brill A, Suidan GL, Wagner DD. Hypoxia, such as encountered at high altitude, promotes deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(9):1773–1775. doi: 10.1111/jth.12310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McInturff AM, Cody MJ, Elliott EA, Glenn JW, Rowley JW, Rondina MT, Yost CC. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates neutrophil extracellular trap formation via induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1 α. Blood. 2012;120(15):3118–3125. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-01-405993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Downing LJ, Strieter RM, Kadell AM, et al. Neutrophils are the initial cell type identified in deep venous thrombosis induced vein wall inflammation. ASAIO J. 1996;42(5):M677–M682. doi: 10.1097/00002480-199609000-00073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ward CM, Tetaz TJ, Andrews RK, Berndt MC. Binding of the von Willebrand factor A1 domain to histone. Thromb Res. 1997;86(6):469–477. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00096-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ni H, Yuen PS, Papalia JM, et al. Plasma fibronectin promotes thrombus growth and stability in injured arterioles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(5):2415–2419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2628067100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matuskova J, Chauhan AK, Cambien B, et al. Decreased plasma fibronectin leads to delayed thrombus growth in injured arterioles. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26(6):1391–1396. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000216282.58291.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Siri A, Balza E, Carnemolla B, Castellani P, Borsi L, Zardi L. DNA-binding domains of human plasma fibronectin. pH and calcium ion modulation of fibronectin binding to DNA and heparin. Eur J Biochem. 1986;154(3):533–538. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ghasemzadeh M, Kaplan ZS, Alwis I, et al. The CXCR1/2 ligand NAP-2 promotes directed intravascular leukocyte migration through platelet thrombi. Blood. 2013;121(22):4555–4566. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-459636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Connolly GC, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Culakova E, Francis CW, Lyman GH. Leukocytosis, thrombosis and early mortality in cancer patients initiating chemotherapy. Thromb Res. 2010;126(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Swystun LL, Mukherjee S, Liaw PC. Breast cancer chemotherapy induces the release of cell-free DNA, a novel procoagulant stimulus. J Thromb Haemost. 2011;9(11):2313–2321. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2011.04465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Demers M, Krause DS, Schatzberg D, et al. Cancers predispose neutrophils to release extracellular DNA traps that contribute to cancer-associated thrombosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(32):13076–13081. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200419109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Donskov F. Immunomonitoring and prognostic relevance of neutrophils in clinical trials. Semin Cancer Biol. 2013;23(3):200–207. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Demers M, Wagner DD. Neutrophil extracellular traps: A new link to cancer-associated thrombosis and potential implications for tumor progression. OncoImmunology. 2013;2(2):e22946. doi: 10.4161/onci.22946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sumby P, Barbian KD, Gardner DJ, et al. Extracellular deoxyribonuclease made by group A Streptococcus assists pathogenesis by enhancing evasion of the innate immune response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(5):1679–1684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Martins GA, Kawamura MT, Carvalho MG. Detection of DNA in the plasma of septic patients. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;906:134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06603.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zeerleder S, Zwart B, Wuillemin WA, et al. Elevated nucleosome levels in systemic inflammation and sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(7):1947–1951. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000074719.40109.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Margraf S, Lögters T, Reipen J, Altrichter J, Scholz M, Windolf J. Neutrophil-derived circulating free DNA (cf-DNA/NETs): a potential prognostic marker for posttraumatic development of inflammatory second hit and sepsis. Shock. 2008;30(4):352–358. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31816a6bb1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stassen PM, Derks RP, Kallenberg CG, Stegeman CA. Venous thromboembolism in ANCA-associated vasculitis—incidence and risk factors. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008;47(4):530–534. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nakazawa D, Tomaru U, Yamamoto C, Jodo S, Ishizu A. Abundant neutrophil extracellular traps in thrombus of patient with microscopic polyangiitis. Front Immunol. 2012;3:333. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fuchs TA, Kremer Hovinga JA, Schatzberg D, Wagner DD, Lämmle B. Circulating DNA and myeloperoxidase indicate disease activity in patients with thrombotic microangiopathies. Blood. 2012;120(6):1157–1164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-412197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Arai Y, Yamashita K, Mizugishi K, et al. Serum neutrophil extracellular trap levels predict thrombotic microangiopathy after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2013;19(12):1683–1689. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fuchs TA, Alvarez JJ, Martinod K, Bhandari AA, Kaufman RM, Wagner DD. Neutrophils release extracellular DNA traps during storage of red blood cell units. Transfusion. 2013;53(12):3210–3216. doi: 10.1111/trf.12203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bovill EG, van der Vliet A. Venous valvular stasis-associated hypoxia and thrombosis: what is the link? Annu Rev Physiol. 2011;73:527–545. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Heit JA. Venous thromboembolism: disease burden, outcomes and risk factors. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3(8):1611–1617. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Coleman DM, Wakefield TW. Biomarkers for the diagnosis of deep vein thrombosis. Expert Opin Med Diagn. 2012;6(4):253–257. doi: 10.1517/17530059.2012.692674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.van Montfoort ML, Stephan F, Lauw MN, et al. Circulating nucleosomes and neutrophil activation as risk factors for deep vein thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013;33(1):147–151. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Diaz JA, Fuchs TA, Jackson TO, et al. Plasma DNA is elevated in patients with deep vein thrombosis. J Vasc Surg Venous Lymphat Disord. 2013;1(4):341-348.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Oklu R, Albadawi H, Watkins MT, Monestier M, Sillesen M, Wicky S. Detection of extracellular genomic DNA scaffold in human thrombus: implications for the use of deoxyribonuclease enzymes in thrombolysis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2012;23(5):712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Seidman MAMR. Surgical pathology of small- and medium-sized vessels. Surg Pathol Clinics. 2012;5(2):435–451. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2012.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wakefield TW, Henke PK. The role of inflammation in early and late venous thrombosis: Are there clinical implications? Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(3):118–129. doi: 10.1053/j.semvascsurg.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Diaz JA, Hawley AE, Alvarado CM, et al. Thrombogenesis with continuous blood flow in the inferior vena cava. A novel mouse model. Thromb Haemost. 2010;104(2):366–375. doi: 10.1160/TH09-09-0672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Becattini C, Agnelli G, Schenone A, et al. WARFASA Investigators. Aspirin for preventing the recurrence of venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1959–1967. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Brighton TA, Eikelboom JW, Mann K, et al. ASPIRE Investigators. Low-dose aspirin for preventing recurrent venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):1979–1987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1210384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lapponi MJ, Carestia A, Landoni VI, et al. Regulation of neutrophil extracellular trap formation by anti-inflammatory drugs. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;345(3):430–437. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.202879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Matsushita K, Morrell CN, Cambien B, et al. Nitric oxide regulates exocytosis by S-nitrosylation of N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor. Cell. 2003;115(2):139–150. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00803-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Torisu T, Torisu K, Lee IH, et al. Autophagy regulates endothelial cell processing, maturation and secretion of von Willebrand factor. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1281–1287. doi: 10.1038/nm.3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.De Meyer SF, Stoll G, Wagner DD, Kleinschnitz C. von Willebrand factor: an emerging target in stroke therapy. Stroke. 2012;43(2):599–606. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.628867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bonnefoy A, Vermylen J, Hoylaerts MF. Inhibition of von Willebrand factor-GPIb/IX/V interactions as a strategy to prevent arterial thrombosis. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2003;1(2):257–269. doi: 10.1586/14779072.1.2.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Pendu R, Terraube V, Christophe OD, Gahmberg CG, de Groot PG, Lenting PJ, Denis CV. P-selectin glycoprotein ligand 1 and beta2-integrins cooperate in the adhesion of leukocytes to von Willebrand factor. Blood. 2006;108(12):3746–3752. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-010322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Furlan M, Robles R, Lämmle B. Partial purification and characterization of a protease from human plasma cleaving von Willebrand factor to fragments produced by in vivo proteolysis. Blood. 1996;87(10):4223–4234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chauhan AK, Motto DG, Lamb CB, et al. Systemic antithrombotic effects of ADAMTS13. J Exp Med. 2006;203(3):767–776. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Crescente M, Thomas GM, Demers M, Voorhees JR, Wong SL, Ho-Tin-Noé B, Wagner DD. ADAMTS13 exerts a thrombolytic effect in microcirculation. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108(3):527–532. doi: 10.1160/TH12-01-0046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.De Meyer SF, Savchenko AS, Haas MS, et al. Protective anti-inflammatory effect of ADAMTS13 on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Blood. 2012;120(26):5217–5223. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-439935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zhao BQ, Chauhan AK, Canault M, et al. von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease ADAMTS13 reduces ischemic brain injury in experimental stroke. Blood. 2009;114(15):3329–3334. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-03-213264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Savchenko AS, Borissoff JI, Martinod K, et al. VWF-mediated leukocyte recruitment with chromatin decondensation by PAD4 increases myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Blood. 2014;123(1):141–148. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-07-514992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Schettert IT, Pereira AC, Lopes NH, Hueb WA, Krieger JE. Association between ADAMTS13 polymorphisms and risk of cardiovascular events in chronic coronary disease. Thromb Res. 2010;125(1):61–66. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Fujihara J, Takatsuka H, Kataoka K, Xue Y, Takeshita H. Two deoxyribonuclease I gene polymorphisms and correlation between genotype and its activity in Japanese population. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2007;9(5):233–236. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Myers DD, Jr, Rectenwald JE, Bedard PW, et al. Decreased venous thrombosis with an oral inhibitor of P selectin. J Vasc Surg. 2005;42(2):329–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.04.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.André P, Hartwell D, Hrachovinová I, Saffaripour S, Wagner DD. Pro-coagulant state resulting from high levels of soluble P-selectin in blood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(25):13835–13840. doi: 10.1073/pnas.250475997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Buchanan JT, Simpson AJ, Aziz RK, et al. DNase expression allows the pathogen group A Streptococcus to escape killing in neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol. 2006;16(4):396–400. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Beiter K, Wartha F, Albiger B, Normark S, Zychlinsky A, Henriques-Normark B. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr Biol. 2006;16(4):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Comerota AJ. Thrombolysis for deep venous thrombosis. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(2):607–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Napirei M, Ludwig S, Mezrhab J, Klöckl T, Mannherz HG. Murine serum nucleases—contrasting effects of plasmin and heparin on the activities of DNase1 and DNase1-like 3 (DNase1l3). FEBS J. 2009;276(4):1059–1073. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06849.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Farrera C, Fadeel B. Macrophage clearance of neutrophil extracellular traps is a silent process. J Immunol. 2013;191(5):2647–2656. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Soo KS, Northeast AD, Happerfield LC, Burnand KG, Bobrow LG. Tissue plasminogen activator production by monocytes in venous thrombolysis. J Pathol. 1996;178(2):190–194. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199602)178:2<190::AID-PATH454>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hemmers S, Teijaro JR, Arandjelovic S, Mowen KA. PAD4-mediated neutrophil extracellular trap formation is not required for immunity against influenza infection. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e22043. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Hakkim A, Fuchs TA, Martinez NE, Hess S, Prinz H, Zychlinsky A, Waldmann H. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(2):75–77. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Lim MB, Kuiper JW, Katchky A, Goldberg H, Glogauer M. Rac2 is required for the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;90(4):771–776. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1010549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Green D, Karpatkin S. Role of thrombin as a tumor growth factor. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(4):656–661. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.4.10729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lande R, Ganguly D, Facchinetti V, et al. Neutrophils activate plasmacytoid dendritic cells by releasing self-DNA-peptide complexes in systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(73):73ra19. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Garcia-Romo GS, Caielli S, Vega B, et al. Netting neutrophils are major inducers of type I IFN production in pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(73):73ra20. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sangaletti S, Tripodo C, Chiodoni C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps mediate transfer of cytoplasmic neutrophil antigens to myeloid dendritic cells toward ANCA induction and associated autoimmunity. Blood. 2012;120(15):3007–3018. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Yasuda T, Iida R, Kawai Y, Nakajima T, Kominato Y, Fujihara J, Takeshita H. Serum deoxyribonuclease I can be used as a useful marker for diagnosis of death due to ischemic heart disease. Leg Med (Tokyo) 2009;11(Suppl 1):S213–S215. doi: 10.1016/j.legalmed.2009.01.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Meng W, Paunel-Gorgulu A, Flohe S, et al. Deoxyribonuclease is a potential counter regulator of aberrant neutrophil extracellular traps formation after major trauma. Mediators Inflamm. 2012;2012:149560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 125.Dylan B. Blood on the Tracks. New York: Columbia; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 126.Thévenaz P, Unser M. User-friendly semiautomated assembly of accurate image mosaics in microscopy. Microsc Res Tech. 2007;70(2):135–146. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Savchenko AS, Martinod K, Seidman MA, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps form predominantly during the organizing stage of human venous thromboembolism development. J Thromb Haemost. doi: 10.1111/jth.12571. 2014 Mar 27. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]