Abstract

Background

The single most important risk factor for postpartum maternal infection is cesarean section. Routine prophylaxis with antibiotics may reduce this risk and should be assessed in terms of benefits and harms.

Objectives

To assess the effects of prophylactic antibiotics compared with no prophylactic antibiotics on infectious complications in women undergoing cesarean section.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (May 2009).

Selection criteria

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-RCTs comparing the effects of prophylactic antibiotics versus no treatment in women undergoing cesarean section.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors independently assessed the studies for inclusion, assessed risk of bias and carried out data extraction.

Main results

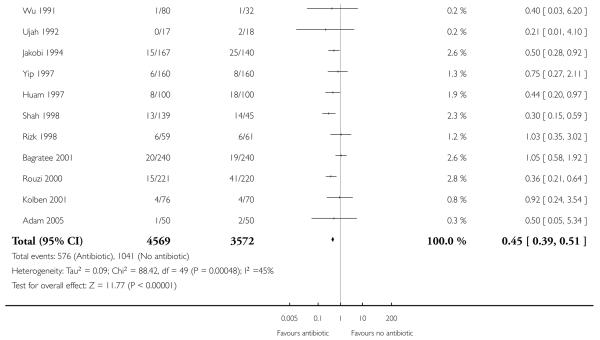

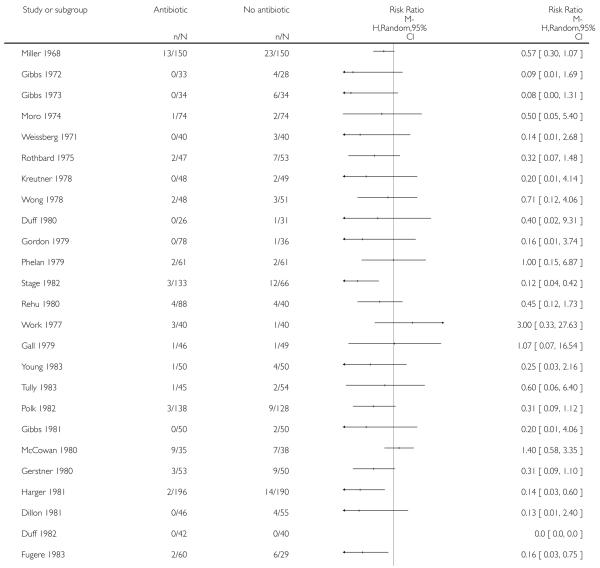

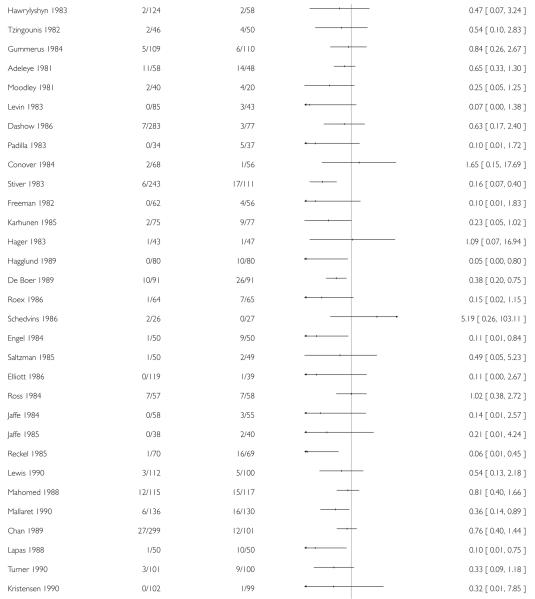

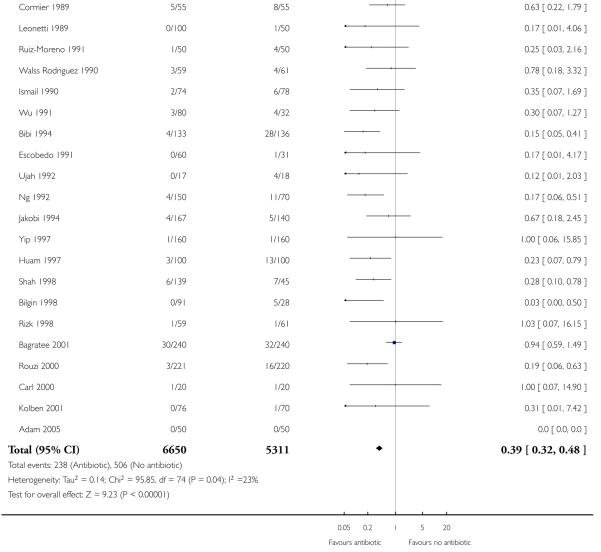

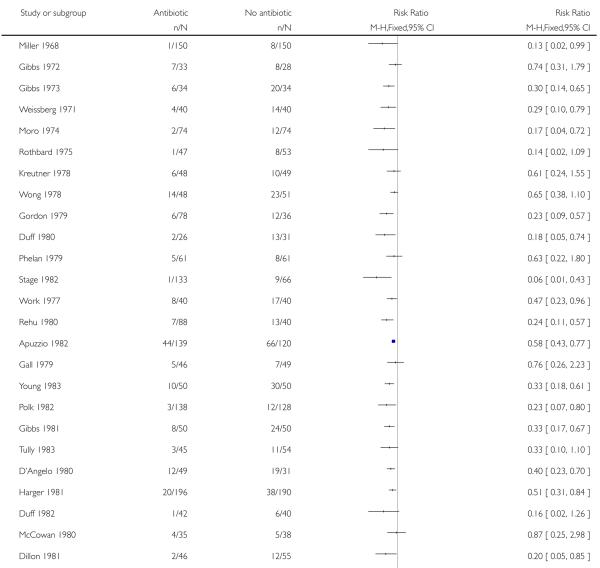

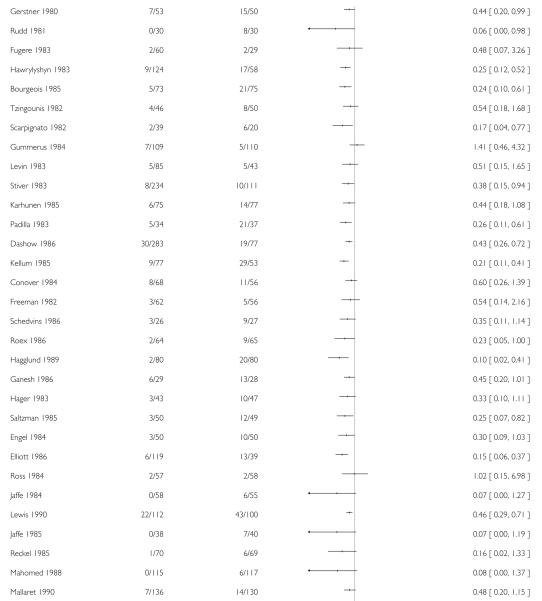

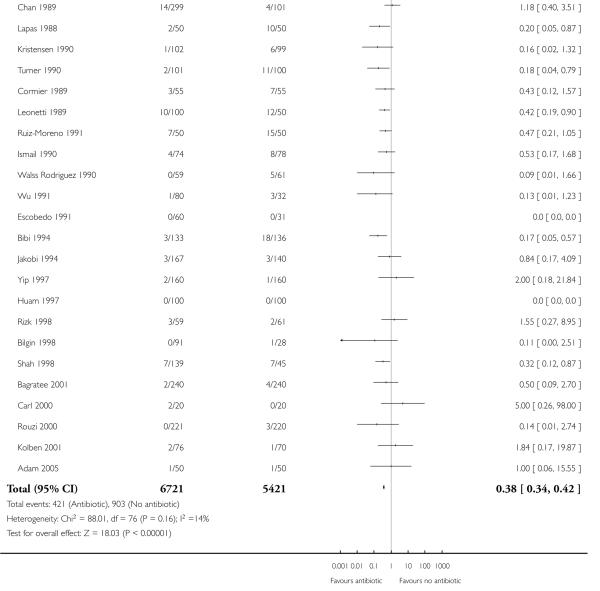

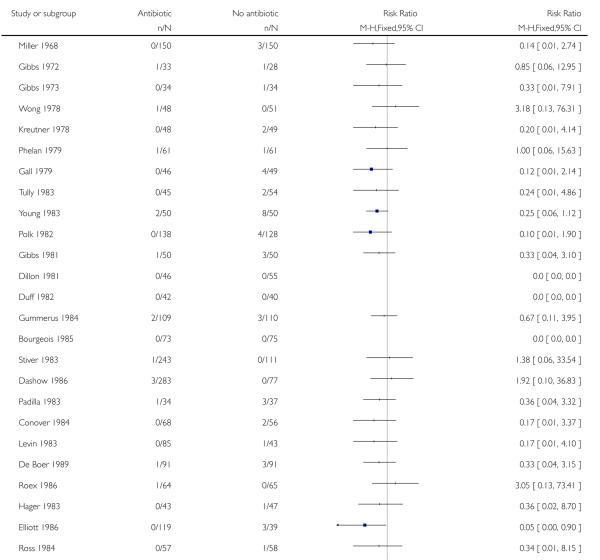

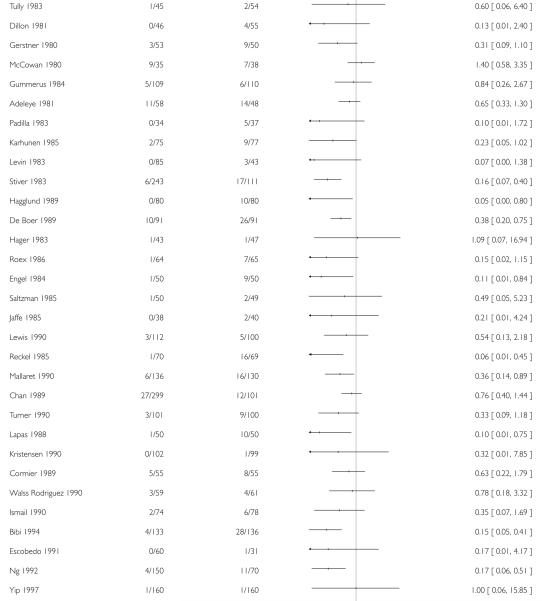

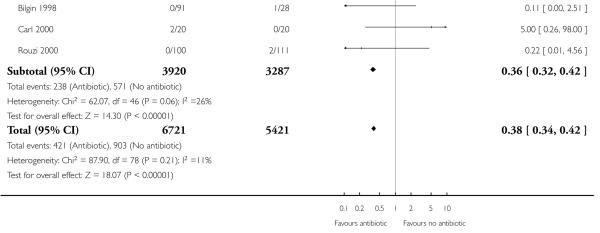

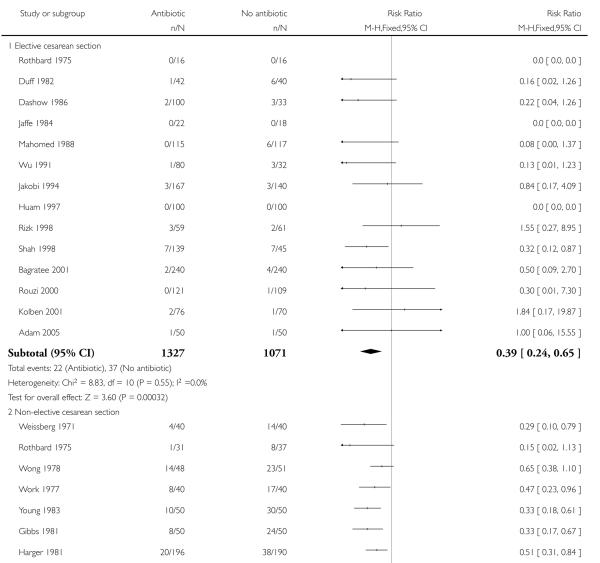

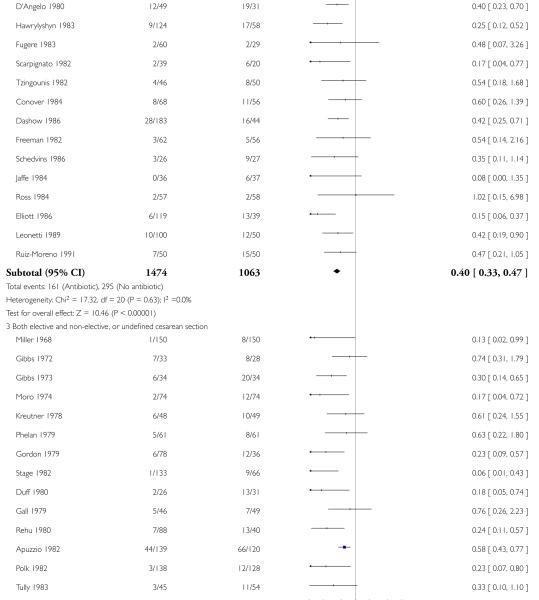

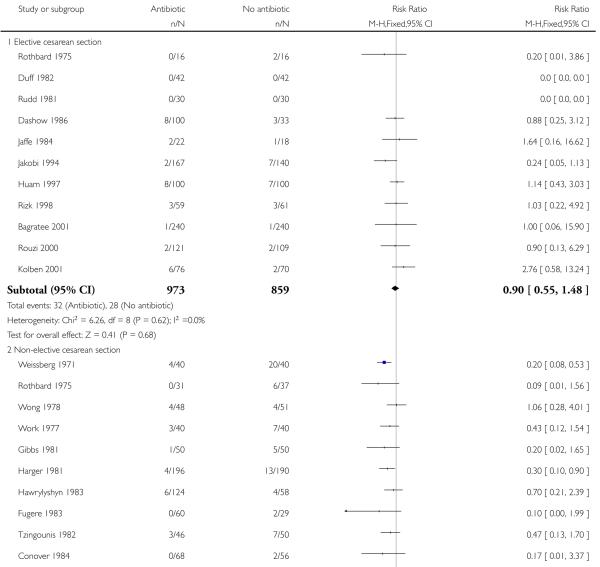

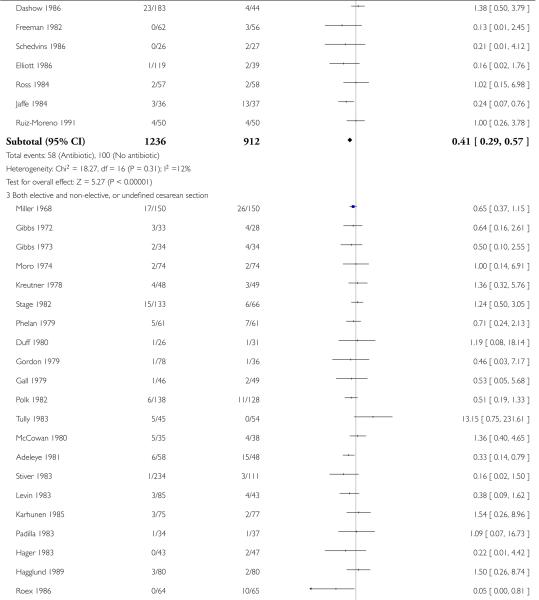

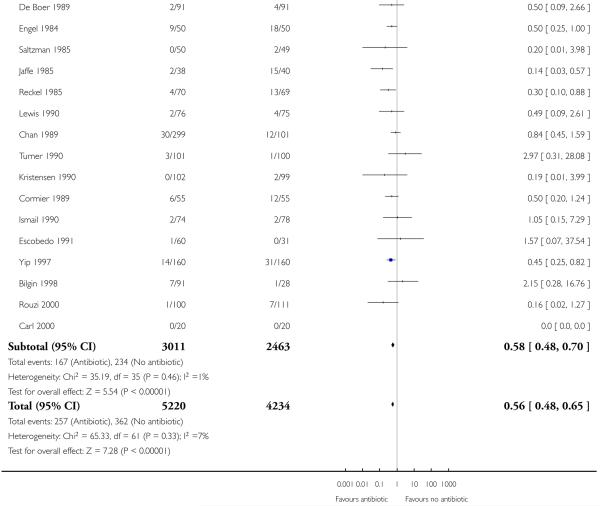

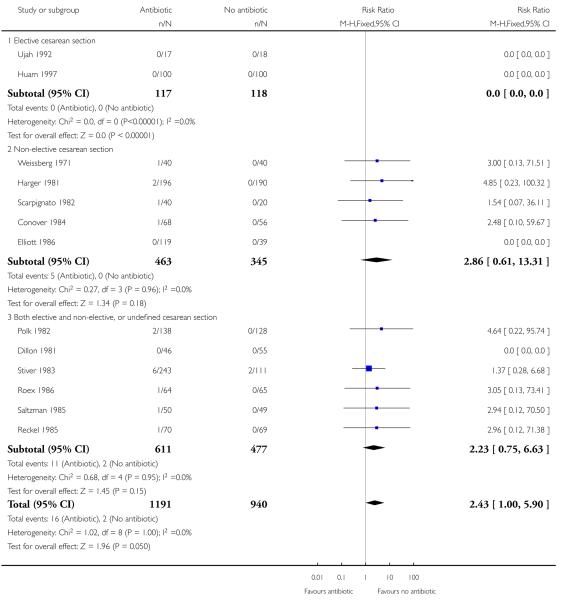

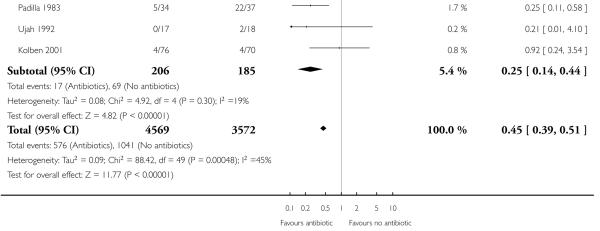

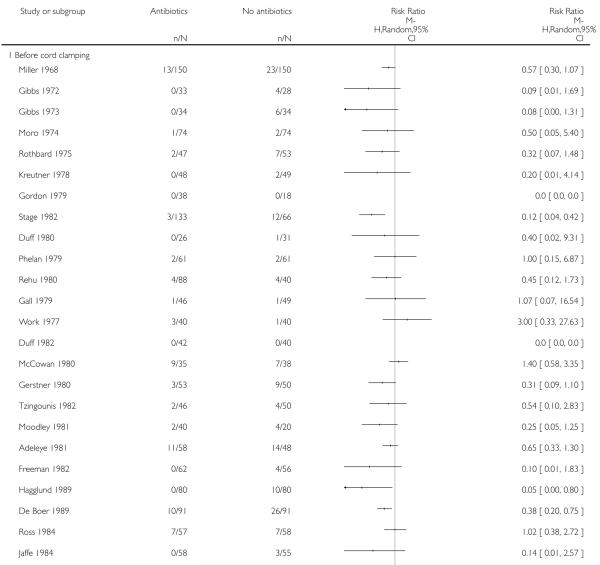

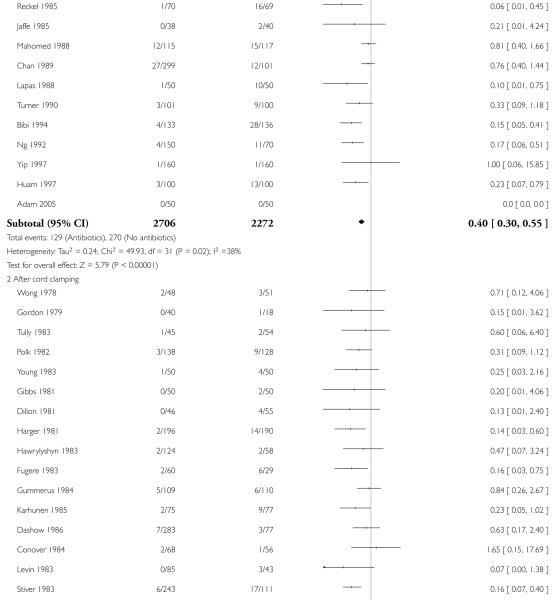

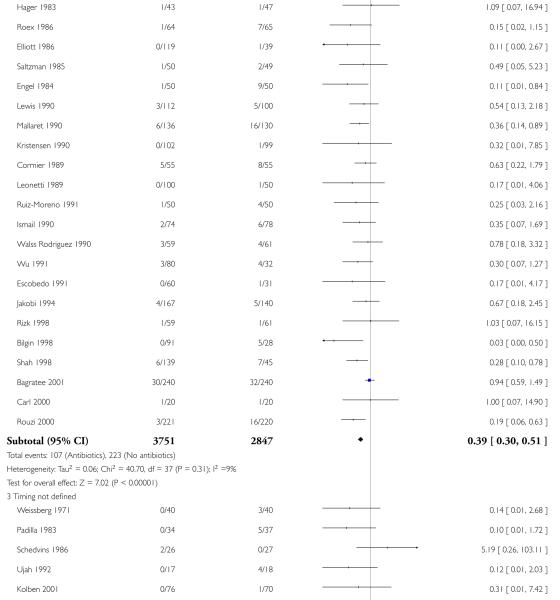

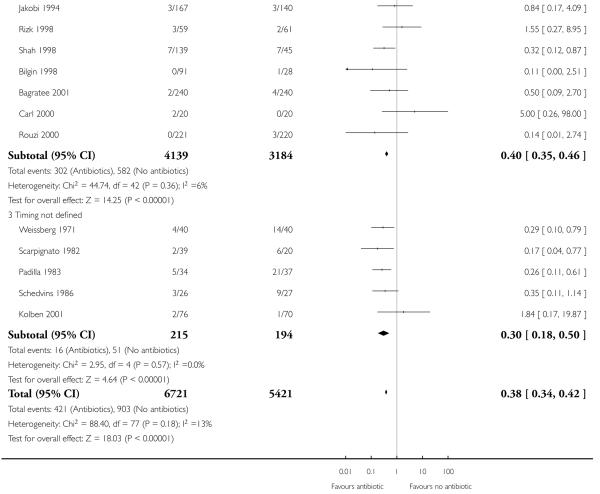

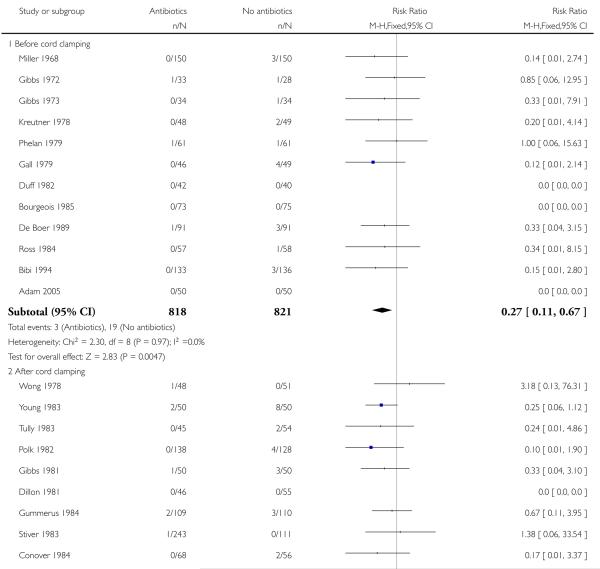

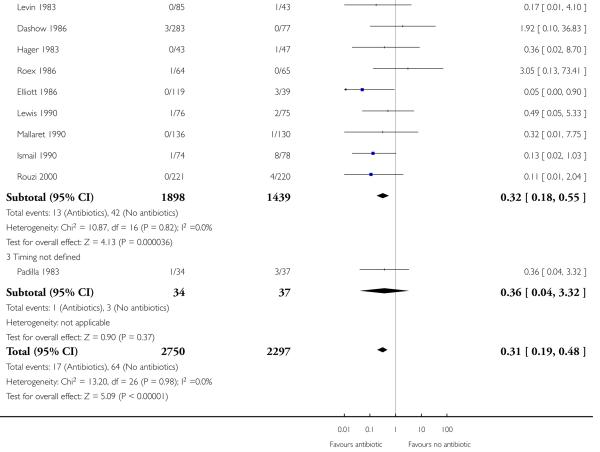

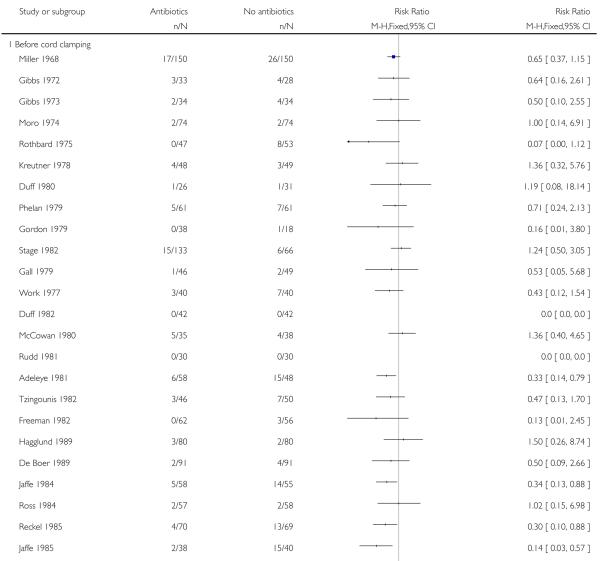

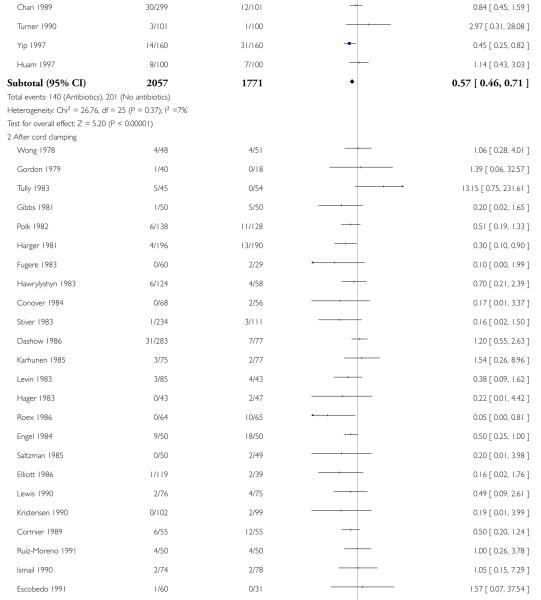

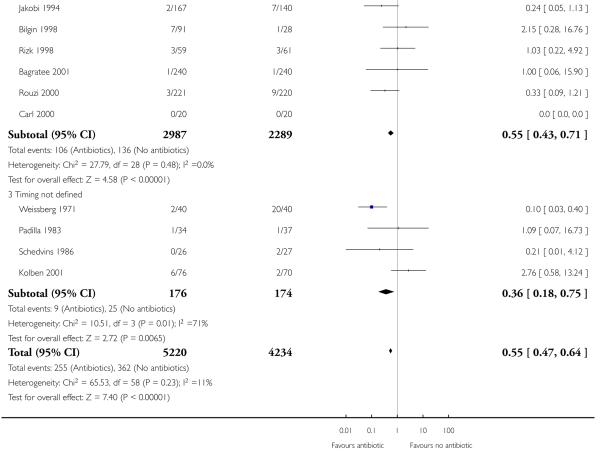

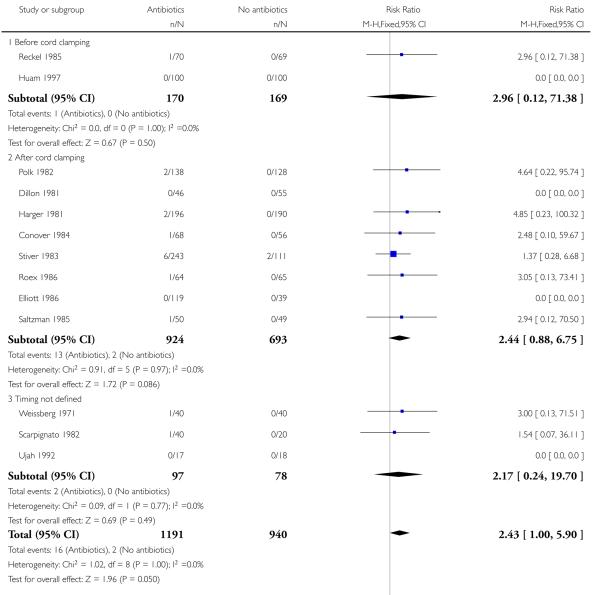

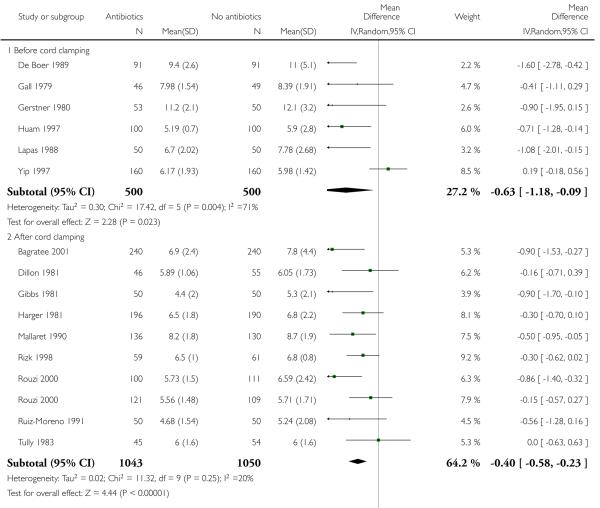

We identified 86 studies involving over 13,000 women. Prophylactic antibiotics in women undergoing cesarean section substantially reduced the incidence of febrile morbidity (average risk ratio (RR) 0.45; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39 to 0.51, 50 studies, 8141 women), wound infection (average RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.48, 77 studies, 11,961 women), endometritis (RR 0.38; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.42, 79 studies, 12,142 women) and serious maternal infectious complications (RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.48, 31 studies, 5047 women). No conclusions can be made about other maternal adverse effects from these studies (RR 2.43; 95% CI 1.00 to 5.90, 13 studies, 2131 women). None of the 86 studies reported infant adverse outcomes and in particular there was no assessment of infant oral thrush. There was no systematic collection of data on bacterial drug resistance. The findings were similar whether the cesarean section was elective or non elective, and whether the antibiotic was given before or after umbilical cord clamping. Overall, the methodological quality of the trials was unclear and in only a few studies was it obvious that potential other sources of bias had been adequately addressed.

Authors’ conclusions

Endometritis was reduced by two thirds to three quarters and a decrease in wound infection was also identified. However, there was incomplete information collected about potential adverse effects, including the effect of antibiotics on the baby, making the assessment of overall benefits and harms complicated. Prophylactic antibiotics given to all women undergoing elective or non-elective cesarean section is clearly beneficial for women but there is uncertainty about the consequences for the baby.

BACKGROUND

The single most important risk factor for postpartum maternal infection is cesarean section (Declercq 2007; Gibbs 1980). Women undergoing cesarean section have a five to 20-fold greater risk for infection and infectious morbidity compared with a vaginal birth. In Western countries the percentage of live births by cesarean section is around 22% (range 12.9% to 33.3%)(OECD 2007); in developing countries the overall rate is around 12% but varies widely by region (0.40% to 40%)(Thomas 2006). Infectious complications that occur after cesarean births are an important and substantial cause of maternal morbidity and are associated with a significant increase in hospital stay (Henderson 1995). Infections can affect the pelvic organs, the surgical wound, and the urinary tract.

Description of the condition

Infectious complications following cesarean birth include fever (febrile morbidity), wound infection, endometritis (inflammation of the lining of the uterus), and urinary tract infection. There can also occasionally be serious infectious complications including pelvic abscess (collection of pus in the pelvis), bacteremia (bacterial infection in the blood), septic shock (reduced blood volume due to infection), necrotizing fasciitis (tissue destruction in the uterine wall) and septic pelvic vein thrombophlebitis (inflammation and infection of the veins in the pelvis); sometimes these can lead to maternal mortality (Boggess 1996; Enkin 1989; Gibbs 1980; Leigh 1990).

Fever can occur after any operative procedure, and a low grade fever following a cesarean birth may not necessarily be a marker of infection (MacLean 1990). Without prophylaxis, the incidence of endometritis is reported to range from 20% to 85%; rates of wound infection and serious infectious complications as high as 25% have been reported (Enkin 1989). There has been no consistent application of a standard definition for endometritis nor wound infection, and surveillance strategies for the ascertainment of infections, especially following hospital discharge, vary widely (Baker 1995; Hulton 1992). Differences in ethnicity, socioeconomic status of the population studied will explain some of the variability in incidence, as will the use of different criteria to diagnose infection (Herbert 1999). Using the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) definitions for infection, the pooled mean rate of surgical site infections after cesarean section for US hospitals participating in the CDC and Prevention’s National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System from January 1992 through June 2004 was 3.15%, ranging from 2.71% for low-risk patients to 7.53% for high-risk patients (NNIS 2004). These rates, when compared with infection rates following other surgical procedures that are collected as part of the NNIS system, are high. Given the number of cesarean sections performed, these rates translate into very large numbers of women with an infectious complication following birth, and significant costs and morbidity.

Factors that have been associated with an increased risk of infection and infectious morbidity among women who have a cesarean include emergency cesarean section, labor and its duration, ruptured membranes and the duration of rupture, the socioeconomic status of the woman, number of prenatal visits, vaginal examinations during labor, internal fetal monitoring, urinary tract infection, anemia, blood loss, obesity, diabetes, general anesthesia, development of subcutaneous hematoma, the skill of the operator and the operative technique (Beattie 1994; Desjardins 1996; Enkin 1989; Gibbs 1980; Killian 2001; Magann 1995; Olsen 2008; Webster 1988). The association of bacterial vaginosis with an increased incidence of endometritis following cesarean birth has also been reported (Watts 1990).

The most important source of micro-organisms responsible for post-cesarean section infection is the genital tract, particularly if the membranes are ruptured. Even in the presence of intact membranes, microbial invasion of the intrauterine cavity is common, especially with preterm labor (Watts 1992). Infections are commonly polymicrobial (caused by many organisms). Pathogens isolated from infected wounds and the endometrium include Escherichia coli and other aerobic gram negative rods, group B streptococcus and other streptococcus species, Enterococcus faecalis, Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase negative staphylococci, anaerobes (including Peptostreptococcus species and Bacteroides species), Gardnerella vaginalis and genital mycoplasmas (Martens 1995; Roberts 1993; Watts 1991). Although Ureaplasma urealyticum is very commonly isolated from the upper genital tract and infected wounds, it is unclear whether it is a pathogen in this setting (Roberts 1993). Wound infections caused by Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase negative staphylococci arise from contamination of the wound with the endogenous flora of the skin at the time of surgery (Emmons 1988).

Description of the intervention

Guidelines recommend the use of antibiotics with a relatively narrow spectrum of activity for prophylaxis based on factors such as cost, half life, safety and antimicrobial resistance and to avoid broad spectrum drugs that are usually reserved for treatment (Bratzler 2004). There are over 20 antibiotic regimens that have been compared for cesarean section prophylaxis. Some of these drugs have activity against a narrow range of potential pathogens (e.g. metronidazole, gentamicin), others specifically have additional anaerobic activity (e.g. cefoxitin and cefotetan), others have activity against Staphylococcus aureus (e.g. cefazolin) and yet others have an extended spectrum of coverage (e.g. meropenem). Details of the different antibiotic regimens for prophylaxis at cesarean section that have been compared and their effectiveness are included in another Cochrane review (Hopkins 1999).

There are differences in the route of administration of prophylactic antibiotics; for cesarean section the antibiotic is generally given intravenously. Usually a single dose is administered at the time of the procedure or multiple doses administered over a short period of time.

For cesarean section, prophylactic antibiotics are administered either before or after the cord is clamped (Classen 1992; Cunningham 1983; Wax 1997), although general guidelines for the prevention of surgical site infections recommend the antimicrobial dose is administered before the incision to achieve low infection rates (Bratzler 2004). A recent meta-analysis on the timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery concluded that there was strong evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis that is given before skin incision decreases maternal infectious complications, without affecting the infant (Costantine 2008). However, it is argued that the timing of antibiotic administration may mask septic complications in the infant (Cunningham 1983). Additionally if the antibiotic is given before cord clamping, the baby will be exposed to the antibiotic via the placenta, and there may be exposure through breast milk if the antibiotic is given either before or after cord clamping, though the passage of antibiotic through the breast milk is thought to minimal (Enkin 1989). Because of the potential for adverse outcomes for the baby and the effect on maternal infectious complications, this review investigated the timing of antibiotic administration (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

How the intervention might work

General principles for the prevention of any surgical infection include sound surgical technique, skin antisepsis and antimicrobial prophylaxis (Owen 1994). Antibiotics administered prophylactically reduce the bacterial inoculum at the time of surgery and decrease the rate of bacterial contamination of the surgical site. An adequate antibiotic level in the tissue can augment natural immune defence mechanisms and help kill bacteria that are invariably in-oculated into the wound at the time of surgery (Talbot 2005).

Potential adverse effects of antibiotic prophylaxis

There are commonly identified adverse effects of antibiotic therapy which include gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting or diarrhoea), skin rashes, thrush (candidiasis, which can affect both mother and baby) and joint pain (Dancer 2004). There can also occasionally be blood problems, kidney or liver damage (Dancer 2004; Westphal 1994) and anaphylaxis (a hypersensitivity reaction to a foreign substance leading to shock and collapse, which can be fatal).

Because there are some data that antibiotics reaching the baby during labor, or in the very early postnatal period, can affect the pattern of bacterial flora in the infant gut, with the potential to affect the baby’s developing immune system (Bedford Russell 2006), it is important to assess the impact of antibiotics given to the mother on the baby’s health.

Antibiotic prophylaxis may lead to increased drug resistant strains of bacteria which may be associated with infection. Resistant organisms may spread within the hospital and be associated with hospital-acquired drug resistant infections (Dancer 2004). These adverse effects cannot be assessed readily in randomized controlled trials, and additional research needs to be undertaken to assess the impact of prophylactic antibiotic use on the level of resistant bacteria, e.g. MRSA and C difficile in hospitals.

Why it is important to do this review

Surveys suggest that there is inconsistent and variable application of the use of prophylactic antibiotics at cesarean sections (Huskins 2001; Olsen 2008; Pedersen 1996). Prophylactic antibiotics have been shown, in previous versions of this review, to be effective in reducing febrile morbidity, endometritis, wound infection and urinary tract infection (Smaill 1995a; Smaill 1995b; Smaill 2002). In addition, both ampicillin and first generation cephalosporins appeared to have similar efficacy in reducing post-operative endometritis, and there did not appear to be any added benefit in utilizing a more broad spectrum agent or a multiple dose regimen (Hopkins 1999). However, it is important to update this evidence with more recent studies, to update the review methodology and also to address the question of whether increasing antimicrobial resistance has had an impact on the benefit of antibiotic prophylaxis.

The adverse effects of antibiotics for the woman and her infant and the potential for increased use of antimicrobial prophylaxis to contribute to the development of antimicrobial resistance are important considerations (Mallaret 1990; Shlaes 1997), as are the cost-effectiveness of different strategies (Mugford 1989). As well, it is important to assess any possible impact of maternal antibiotic treatment on the baby, as there is evidence that antibiotics given near or shortly after birth can affect the infant’s gut bacterial flora, with the potential to impact mucosal and systemic immune function (Bedford Russell 2006).

Particularly controversial is whether antibiotic treatment should be given to all mothers or only to those at greatest risk of infection (Ehrenkrans 1990; Gilstrap 1988; Howey 1990; Suonio 1989). Women undergoing cesarean section can be divided into low- and high-risk groups for infection. Women at high risk include those undergoing cesarean section after rupture of the membranes or onset of labor (ACOG 2003). We were interested to see if there was a difference in effectiveness depending on whether there is a high or low risk of infection. We performed a subgroup analysis based on whether the cesarean section was a planned procedure (elective) or whether there was active labor or ruptured membranes (non-elective).

It has been suggested that institutions with a low levels of baseline infections may see no impact of routine use of antibiotics, while institutions with high baseline infection rates may see a benefit. To explore this would require baseline measurements taken before randomization (e.g. data on infection rates over the previous year at the hospitals in the trial). It would not be valid to use a variable that arises after randomization for performing the stratification into high and low infection rates, such as the wound infection rates found in each trial’s control group. This could easily lead to spurious results, because of regression to the mean: there is a relationship between the control group event rate and the effect size, with larger treatment effects associated with higher control group event rates. A difference in treatment effects between high and low control group event rates would be expected and would not necessarily indicate a real difference (Gates 2008). Because we were interested to see if there was an effect of baseline risk of infection on outcomes, we looked for any information in the studies that described rates of infection before the intervention. This review will focus on whether antibiotics do more good than harm overall. A comparison of the effectiveness of different antibiotic regimens is covered in another Cochrane review (Hopkins 1999). Additional ways for trying to reduce post-cesarean infections (which may be the subject of future Cochrane reviews) include: skin preparation at cesarean section; double gloving or changing gloves (or both) before closure; peritoneal lavage; and vaginal antiseptic solution preparation.

OBJECTIVES

To determine, from the best evidence available, the effectiveness of prophylactic antibiotics compared with placebo, or no treatment, given to women when undergoing a cesarean section for reducing the incidence of febrile morbidity, wound infection, endometritis, urinary tract infection or any serious infectious complication, and to assess potential adverse effects and any impact on the infant, either short term or long term.

Comparisons between specific regimens will not be included in this version of the review; these have been assessed in another Cochrane review (Hopkins 1999) which is currently being updated.

METHODS

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the effects of prophylactic antibiotics in women undergoing cesarean section. Quasi-RCTs will also be included. We shall include cluster-RCTs should any be identified but cross-over trials are inappropriate for this question.

Types of participants

Women undergoing cesarean section, both elective and non-elective/emergency.

Types of interventions

Trials will be considered if they compare any prophylactic antibiotic regimen administered for cesarean section with placebo or no treatment.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Maternal

Febrile morbidity (fever)

Wound infection (infection of the surgical incision)

Endometritis (inflammation of the lining of the womb)

Serious infectious complication (such as bacteremia, septic shock, septic thrombophlebitis, necrotizing fasciitis, or death attributed to infection)

Infant

Immediate adverse effects of antibiotics on the infant (unsettled, diarrhoea, rashes)

Oral thrush (candidiasis)

Secondary outcomes

Maternal

Urinary tract infection

Adverse effects of treatment on the woman (e.g. allergic reactions, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, skin rashes, thrush)

Length of stay in hospital

Infant

Length of stay in hospital

Long-term adverse effects (e.g. general health; frequency of visits to hospital)

Immune system development (using a validated scoring assessment)

Additional outcomes

Development of bacterial resistance

Cost

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We contacted the Trials Search Co-ordinator to search the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register (May 2009).

The Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register is maintained by the Trials Search Co-ordinator and contains trials identified from:

quarterly searches of the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL);

weekly searches of MEDLINE;

handsearches of 30 journals and the proceedings of major conferences;

weekly current awareness alerts for a further 44 journals plus monthly BioMed Central email alerts.

Details of the search strategies for CENTRAL and MEDLINE, the list of handsearched journals and conference proceedings, and the list of journals reviewed via the current awareness service can be found in the ‘Specialized Register’ section within the editorial information about the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group.

Trials identified through the searching activities described above are each assigned to a review topic (or topics). The Trials Search Co-ordinator searches the register for each review using the topic list rather than keywords.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists at the end of papers for further studies.

We did not apply any language restrictions.

Data collection and analysis

For the new studies identified since publication of the previous version of this review (Smaill 2002), two review authors have made the inclusion/exclusion decisions and undertaken data extraction independently, then conferred to agree. Had there been any disagreement, a third assessor would have been asked to decide. With the studies in the previous version of the review (Smaill 2002), one author (F Smaill) has done the data extraction twice; once originally for the previous version of this review and again now, eight years later, to check for accuracy. The following now describes the new methodology being used.

Selection of studies

Two review authors independently assessed for inclusion all the potential studies identified as a result of the search strategy. We resolved any disagreement through discussion. If required a third person would have been consulted to resolve any disagreements.

Data extraction and management

We designed a form to extract data. For eligible studies, we extracted the data independently using the agreed form. We resolved discrepancies through discussion or, if required, a third person would have been consulted. We entered the data into Review Manager software (RevMan 2008) and checked them for accuracy. When information regarding any of the above was unclear, we attempted to contact authors of the original reports to provide further details.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Both review authors independently assessed risk of bias for each study using the criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). Any disagreement would have been resolved by discussion or by involving a third assessor.

1) Sequence generation (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the methods used to generate the allocation sequence in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of whether it should produce comparable groups.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (any truly random process, e.g. random number table; computer random number generator);

inadequate (any non random process, e.g. odd or even date of birth; hospital or clinic record number);

unclear.

2) Allocation concealment (checking for possible selection bias)

We described for each included study the method used to conceal the allocation sequence in sufficient detail and determined whether intervention allocation could have been foreseen in advance of, or during recruitment, or changed after assignment.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (e.g. telephone or central randomization; consecutively numbered sealed opaque envelopes);

inadequate (e.g. open random allocation; unsealed or non-opaque envelopes, alternation; date of birth);

unclear.

3) Blinding (checking for possible performance bias)

We described for each included study all the methods used, if any, to blind study participants and personnel from knowledge of which intervention a participant received. We also provided information on whether the intended blinding was effective. Where blinding was not possible, we assessed whether the lack of blinding was likely to have affected outcomes and introduced bias. Blinding was assessed separately for different outcomes or classes of outcomes.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate, inadequate or unclear for participants;

adequate, inadequate or unclear for personnel;

adequate inadequate or unclear for outcome assessors;

where ‘adequate’ was when there was blinding or where we assessed that the outcome or the outcome measurement was not likely to have been influenced by lack of blinding.

4) Incomplete outcome data (checking for possible attrition bias through withdrawals, dropouts, protocol deviations)

We described for each included study and for each outcome or class of outcomes the completeness of data including attrition and exclusions from the analysis. We stated whether attrition and exclusions were reported, the numbers included in the analysis at each stage (compared with the total randomized participants), reasons for attrition or exclusion where reported, and whether missing data were balanced across groups or were related to outcomes. Where sufficient information was reported or could be supplied by the trial authors, we re-included missing data in the analyses which we performed.

We discussed whether missing data greater than 20% might impact on outcomes acknowledging that with long-term follow up, complete data are difficult to attain.

5) Selective reporting bias

We described for each included study how we investigated the possibility of selective outcome reporting bias and what we found.

We assessed the methods as:

adequate (where it was clear that all of the study’s pre-specified outcomes and all expected outcomes of interest to the review have been reported);

inadequate (where not all the study’s pre-specified outcomes have been reported; one or more reported primary outcomes were not pre-specified; outcomes of interest were reported incompletely and so could not be used; study failed to include results of a key outcome that would have been expected to have been reported);

unclear.

6) Other sources of bias

We described for each included study any important concerns we had about other possible sources of bias. This included potential sources of bias related to, for example, publication bias, whether the trial was stopped early and extreme baseline imbalance.

We assessed whether each study was free of other problems that could put it at risk of bias:

yes;

no;

unclear.

7) Overall risk of bias

We made explicit judgements about whether studies were at high risk of bias, according to the criteria given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2008). These criteria suggest (1) high risk of bias is where plausible bias seriously weakens confidence in the results; (2) unclear risk of bias is where plausible bias raises doubts about the results; and (3) low risk of bias is where plausible bias is unlikely to seriously alter the results. With reference to (1) to (6) above, we assessed the likely magnitude and direction of the bias and whether we considered it was likely to impact on the findings. We planned to explore the impact of the level of bias through undertaking sensitivity analyses - see Sensitivity analysis.

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous data, we present results as summary risk ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Continuous data

For continuous data, we used the mean difference if outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardized mean difference to combine trials that measured the same outcome, but used different methods.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster-randomized trials

We would have included cluster-randomized trials (cluster-RCTs) in the analyses along with individually-randomized trials, had we identified any cluster-RCTs. Their sample sizes would have been adjusted using the methods described in Higgins 2008 using an estimate of the intracluster correlation co-efficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible), or from another source. If ICCs from other sources were used, this would have been reported and sensitivity analyses conducted to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC. If we had identified both cluster-RCTs and individually-randomized trials, we had planned to synthesise the relevant information. We would have considered it reasonable to combine the results from both if there was little heterogeneity between the study designs and the interaction between the effect of intervention and the choice of randomization unit was considered to be unlikely.

We would have also acknowledged heterogeneity in the randomization unit and performed a separate meta-analysis.

Dealing with missing data

For included studies, levels of attrition were noted. We would have explored the impact of including studies with high levels of missing data in the overall assessment of treatment effect using sensitivity analysis.

For all outcomes analyses were carried out, as far as possible, on an intention-to-treat basis, i.e. we attempted to include all participants randomized to each group in the analyses. The denominator for each outcome in each trial was the number of participants with data, that is, the number randomized minus any participants whose outcomes were known to be missing (available case analysis). If more than 20% of participants were missing from an outcome we planned to explore by sensitivity analyses (see Sensitivity analysis).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We have assessed statistical heterogeneity in each meta-analysis using the T2 (tau-squared), I2 and Chi2 statistics. We have regarded heterogeneity as substantial if T2 was greater than zero and either I2 was greater than 30% or there was a low P-value (less than 0.10) in the Chi2 test for heterogeneity. Where we found heterogeneity and random-effects was used, we have reported the average risk ratio, or average mean difference or average standard mean difference.

Assessment of reporting biases

Where we suspected reporting bias (see Assessment of reporting biases), we attempted to contact study authors asking them to provide missing outcome data. Where this was not possible, and the missing data were thought to introduce serious bias, we planned to explore the impact of including such studies in the overall assessment of results by a sensitivity analysis.

Where there were 10 or more studies in a meta-analysis, we have investigated reporting biases (such as publication bias) using funnel plots. We have assessed funnel plot asymmetry visually. In a subsequent update of this review we shall include formal tests for funnel plot asymmetry and we plan to use the test proposed by Egger 1997 for continuous outcomes and the test proposed by Harbord 2006 for dichotomous outcomes.

Data synthesis

We have carried out statistical analysis using the Review Manager software (RevMan 2008). We have used fixed-effect meta-analysis for combining data where it was reasonable to assume that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect, i.e. where trials were examining the same intervention and the trials’ populations and methods were judged sufficiently similar. If there was clinical heterogeneity sufficient to expect that the underlying treatment effects differed between trials, or if substantial statistical heterogeneity was detected, we have used random-effects analysis to produce an overall summary, if this was considered clinically meaningful. If an average treatment effect across trials had not been clinically meaningful, we would not have combined heterogeneous trials. If we used random-effects analyses, the results have been presented as the average treatment effect and its 95% confidence interval.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We carried out the following subgroup analyses.

By type of surgery: (a) elective cesarean section; (b) non-elective cesarean section; and (c) mixed or not defined. (Rupture of membranes for more than six hours or the presence of labor was used to differentiate a non-elective cesarean section from an elective procedure.)

By time of administration: (a) before cord clamping; (b) after cord clamping; (c) not defined.

For fixed-effect meta-analyses, we used visual inspection with non-overlapping confidence intervals to indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups. We had planned to conduct subgroup analyses classifying whole trials by interaction tests as described by Deeks 2001 and will undertake these in a subsequent update of this review. For random-effects meta-analyses, we also used visual inspection with non-overlapping confidence intervals to indicate a statistically significant difference in treatment effect between the subgroups

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to carry out sensitivity analysis to explore the effect of trial quality for important outcomes in the review. Where there was a high risk of bias associated with a particular aspect of study quality, for example, quasi-RCTs where there is inadequate sequence generation and allocation concealment (Schultz 1995), we planned to explore this by sensitivity analysis (Higgins 2008).

RESULTS

Description of studies

See: Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

Results of the search

The search of the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s Trials Register identified 129 publications from 116 studies (13 studies had a second publication for the one study). Eighty-six studies were included (Characteristics of included studies), 20 were excluded (Characteristics of excluded studies) and 10 are awaiting classification, all because they are being translated (Characteristics of studies awaiting classification). We found no additional studies through searching reference lists.

Included studies

The 86 studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review enrolled over 13,000 women. For detailed information on the studies, see table of Characteristics of included studies. No study reported on baseline risk of infection before the intervention.

Setting

While the majority of the studies included in the review were conducted in industrial countries (e.g. US, Western Europe, Scandinavia, Canada and New Zealand), studies were reported from developing countries including Sudan, Nigeria, Tunisia, Kenya, Zimbabwe, and South Africa as well as Mexico, Greece, Turkey, Israel, the Middle East, China and Malaysia. Many of the studies included a majority of women who were identified as from a low socio-economic group, but other studies enrolled women who were not perceived to be at an increased risk of infection because of socio-economic status. Most studies adequately described the characteristics of the women who were enrolled, including details of the indication for cesarean section, mean duration of labor and membrane rupture and number of repeat sections. One study included information on the number of women who were HIV positive (Bagratee 2001). In no study were details on the incidence of bacterial vaginosis provided. No study reported baseline infection rates before the intervention.

Type of cesarean section

One objective of this review was to study the effect of prophylaxis in both elective and non-elective cesarean sections, and strict definitions of an elective and non-elective cesarean section were used by the authors of this review to categorize women and studies. In eleven studies (N = 2225), data on women undergoing an elective cesarean section were available (Adam 2005; Bagratee 2001; Duff 1982; Huam 1997; Jakobi 1994; Kolben 2001; Mahomed 1988; Rizk 1998; Shah 1998; Ujah 1992; Wu 1991). In 19 studies (N = 2229), there were data on non-elective procedures (Conover 1984; D’Angelo 1980; Elliott 1986; Freeman 1982; Fugere 1983; Gibbs 1981; Harger 1981; Hawrylyshyn 1983; Leonetti 1989; Moodley 1981; Ross 1984; Ruiz-Moreno 1991; Scarpignato 1982; Schedvins 1986; Tzingounis 1982; Weissberg 1971; Wong 1978; Work 1977; Young 1983). Three studies (N = 573) included both women having elective cesareans and non-elective cesareans (Dashow 1986; Jaffe 1984; Rothbard 1975). The remaining, and the majority of studies did not differentiate between an elective or non-elective procedure, or the definitions used were not consistent with those used in this review; these have been grouped as ‘both’ or ‘undefined’. Often a repeat section had been classified as elective by the study authors, but it was not always evident that all of these women were indeed not in labor and often the duration of membrane rupture was unclear. Fifty-two studies (N = 7765) were classified as undefined type of cesarean section (Adeleye 1981; Allen 1972; Apuzzio 1982; Bibi 1994; Bilgin 1998; Bourgeois 1985; Carl 2000; Chan 1989; Cormier 1989; De Boer 1989; Dillon 1981; Duff 1980; Engel 1984; Escobedo 1991; Gall 1979; Ganesh 1986; Gerstner 1980; Gibbs 1972; Gibbs 1973; Gordon 1979; Gummerus 1984; Hager 1983; Hagglund 1989; Ismail 1990; Jaffe 1985; Karhunen 1985; Kellum 1985; Kreutner 1978; Kristensen 1990; Lapas 1988; Levin 1983; Lewis 1990; Mallaret 1990; McCowan 1980; Miller 1968; Moro 1974; Morrison 1973; Ng 1992; Padilla 1983; Phelan 1979; Polk 1982; Reckel 1985; Rehu 1980; Roex 1986; Rudd 1981; Saltzman 1985; Stage 1982; Stiver 1983; Tully 1983; Turner 1990; Walss Rodriguez 1990; Yip 1997). One study reported both elective and emergency cesarean sections; the emergency sections, however, did not meet our definition of non-elective and these have been classified as “undefined” (Rouzi 2000).

Timing of antibiotic administration

Antibiotics for prophylaxis were administered intravenously either at the start of the operative procedure (“before cord”) or at or after clamping of the cord. In 36 studies (N = 5164), data on outcomes were available when the antibiotic had been administered before clamping of the cord (Adam 2005; Adeleye 1981; Allen 1972; Bibi 1994; Chan 1989; De Boer 1989; Duff 1980; Duff 1982; Freeman 1982; Gall 1979; Gerstner 1980; Gibbs 1972; Gibbs 1973; Hagglund 1989; Huam 1997; Jaffe 1984; Jaffe 1985; Kreutner 1978; Lapas 1988; Mahomed 1988; McCowan 1980: Miller 1968; Moodley 1981; Moro 1974; Morrison 1973; Ng 1992; Phelan 1979; Reckel 1985; Rehu 1980; Ross 1984; Rothbard 1975; Stage 1982; Turner 1990; Tzingounis 1982; Work 1977; Yip 1997). This was variably described as “pre-operatively”, “with induction of anaesthesia” or “before clamping of the cord”. In 43 studies (N = 7284) the antibiotic was administered at or after cord clamping (Apuzzio 1982; Bagratee 2001; Bourgeois 1985; Bilgin 1998; Carl 2000; Conover 1984; Cormier 1989; Dashow 1986; D’Angelo 1980; Dillon 1981; Elliott 1986; Engel 1984; Escobedo 1991; Fugere 1983; Ganesh 1986; Gibbs 1981; Gummerus 1984; Hager 1983; Harger 1981; Hawrylyshyn 1983; Ismail 1990; Jakobi 1994; Karhunen 1985; Kellum 1985; Kristensen 1990; Leonetti 1989; Levin 1983; Lewis 1990; Mallaret 1990; Polk 1982; Rizk 1998; Roex 1986; Rouzi 2000; Rudd 1981; Ruiz-Moreno 1991; Saltzman 1985; Shah 1998; Stiver 1983; Tully 1983; Walss Rodriguez 1990; Wong 1978; Wu 1991; Young 1983). Included in this group were studies where irrigation of the peritoneal or uterine cavity with an antibiotic containing solution was compared with either saline irrigation or no irrigation (Bourgeois 1985; Carl 2000; Conover 1984; Dashow 1986; Elliott 1986; Kellum 1985; Levin 1983; Lewis 1990; Rudd 1981; Wu 1991). There were six studies (N = 444) where there was insufficient information to know when the antibiotic had been administered, e.g. “operatively” or the results had been combined and these have been grouped together as “timing not defined” (Kolben 2001; Padilla 1983; Scarpignato 1982; Schedvins 1986; Ujah 1992; Weissberg 1971). In one study, results were available for antibiotic administration both before and after clamping of the cord (Gordon 1979).

Classes of antibiotics

The antimicrobial agents most often used in the trials included ampicillin, a first generation cephalosporin (usually cefazolin), a second generation cephalosporin (cefoxitin, cefotetan, cefamandole or cefuroxime), metronidazole, penicillins with an extended spectrum of activity (e.g. ticarcillin, mezlocillin or pipericillin), a beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor combination and an amino-glycoside-containing combination; see Characteristics of included studies for a classification of the antimicrobial agent used by antibiotic class. The penicillins have been divided into aminopenicilins (ampicillin), carboxypenicillins (carbenicillin, ticarcillin) or ureidopenicillins (mezlocillin, pipericillin). The second generation cephalosporins include the cefamycins (cefoxitin and cefotetan) that have extended anaerobic coverage. There was one study where the antimicrobial prophylaxis was administered by rectal suppository (De Boer 1989). The duration of the post-operative treatment course varied from a single intravenous dose (N = 22) to as long as a week. In a number of studies, antibiotics were continued for up to 24 hours following the procedure. While most studies were published in the 1980s, new studies have continued to be performed in the 1990s and the last study was published as recently as 2005. The next version of this review will include specific comparisons of the individual classes of antibiotics.

Assessing outcomes

The clinical criteria listed to define endometritis were consistent across trials. Febrile morbidity is a standard obstetrical outcome and was generally consistently reported although there was some variation in the exact criteria used for height of fever, interval between febrile episodes and interval from the operative procedure. Urinary tract infection generally meant a positive urine culture; symptoms related to the urinary tract were rarely required to be present. Wound infection usually was a clinical diagnosis and generally included induration, erythema, cellulitis or various degrees of drainage. A positive microbiological diagnosis was rarely required for the diagnosis of either wound infection or endometritis. There was no consistent approach to the definition of serious morbidity. For this review, all episodes of bacteremia have been classified as serious as have other complications such as pelvic abscess, pelvic thrombophlebitis and peritonitis. Some studies included other outcomes, e.g. need for additional antibiotic use and other infections, e.g. pneumonia. Some provided a measure of the fever as a ‘fever index’ which incorporated both the height of the fever and its duration. Where the duration of maternal hospital stay with its standard deviation was reported this has been included.

Side effects

Very few studies appeared to have consistently sought maternal side effects or neonatal/infant side effects and similarly it was the minority of studies that collected data on infectious complications after discharge.

Excluded studies

Of those studies excluded from the analysis, most were because either no clinical outcomes were reported or the specific outcomes of interest were not described. For some studies, although the trial was initially randomized, part-way through the study the placebo arm was dropped. Because results on the initially randomized part of the study were not available, these studies were not included in the analysis (See table of Characteristics of excluded studies for further details).

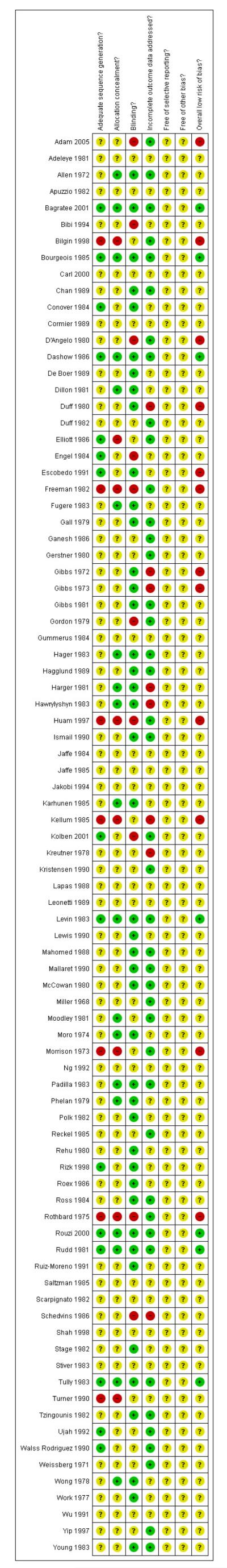

Risk of bias in included studies

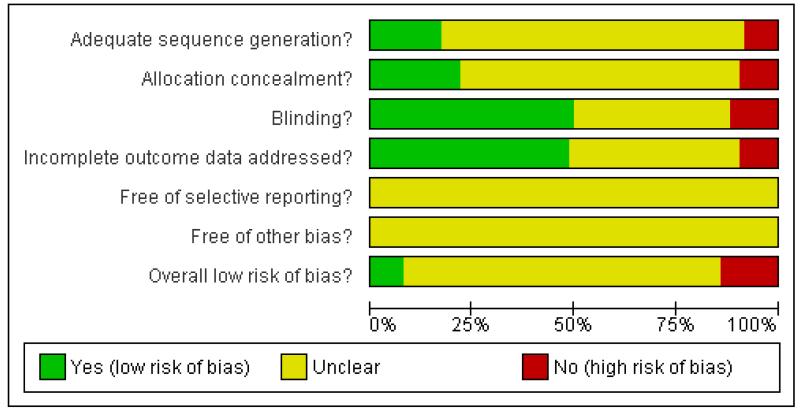

The methodological quality of the trials on the whole was unclear. This is mostly because the studies were undertaken a number of years ago, before the recent understanding of sources of bias in randomised controlled trials (Figure 1; Figure 2).

Figure 1. Methodological quality graph: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Figure 2. Methodological quality summary: review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Seven studies assessed as adequate on sequence generation and allocation concealment (Bagratee 2001; Bourgeois 1985; Dashow 1986; Levin 1983; Rouzi 2000; Rudd 1981; Tully 1983). In 12 studies, the allocation concealment was adequate and although the randomization was unclear this was believed to be due to inadequate reporting rather than bias (Allen 1972; Dillon 1981; Fugere 1983; Hager 1983; Harger 1981; Hawrylyshyn 1983; Karhunen 1985; Moodley 1981; Moro 1974; Padilla 1983; Phelan 1979; Wong 1978). Seven studies were identified as quasi-RCTs (Bilgin 1998; Freeman 1982; Huam 1997; Kellum 1985; Morrison 1973; Rothbard 1975; Turner 1990).

Blinding

Approximately half of the studies (43/86) were placebo-controlled (which included the use of saline irrigation).

Incomplete outcome data

In most studies, all women who were initially randomized were included in the outcomes and an intention-to-treat analysis was performed. Dropouts were reported in about a quarter of studies but insufficient data were provided for them to be included in an intent-to-treat analysis. Where the group allocation of dropouts was not provided, there was the possibility that there may have been selective withdrawals from one or other of the groups. There were some studies where a discrepancy in the numbers allocated to the randomized groups, unlikely to have occurred by chance, was not accounted for. In most cases the numbers in the placebo group were smaller than those in the treatment group, raising the possibility of selective withdrawals not mentioned in the published report.

Selective reporting

This was unclear in all studies as we were unable to assess the trial protocols.

We undertook funnel plots for the primary outcomes to assess reporting bias, e.g. publication bias.

Other potential sources of bias

These were mostly unclear.

Effects of interventions

From the 86 studies included we have 14 meta-analyses.

1. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis (Analyses 1.1 to 1.14)

Bearing in mind the lack of clarity regarding potential risk of bias for the included studies in this comparison, the overall findings were as follows.

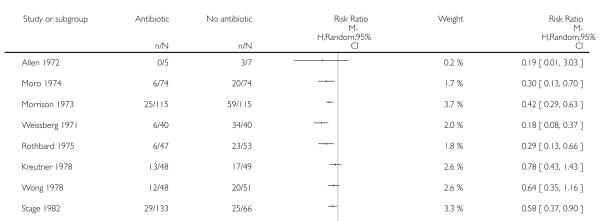

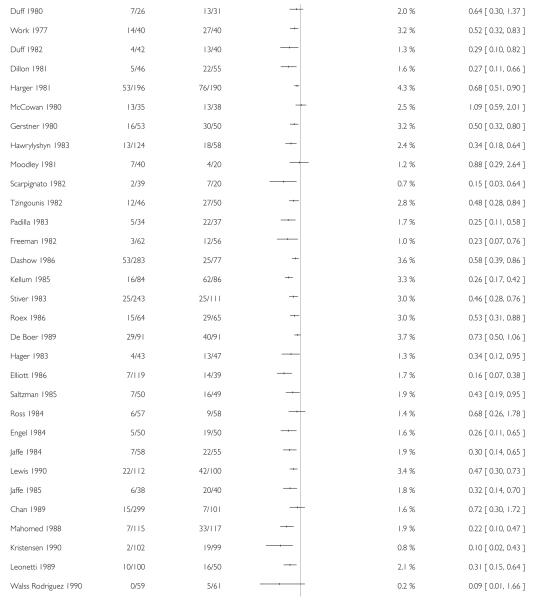

Primary outcomes

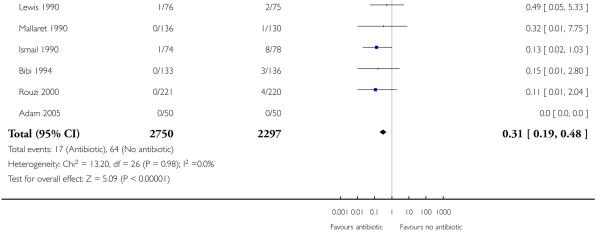

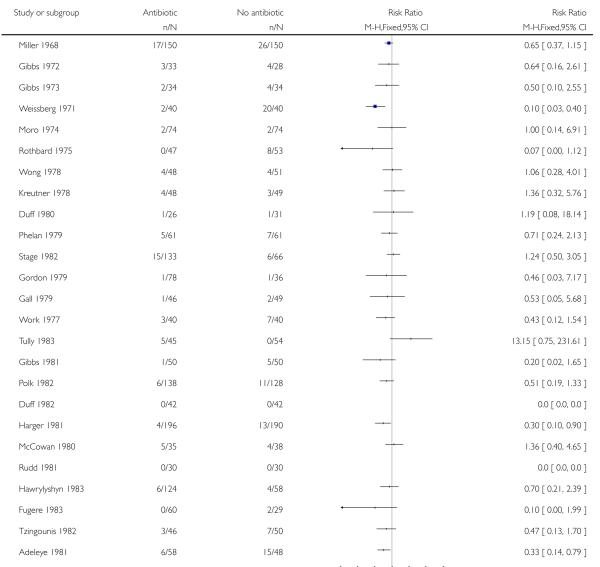

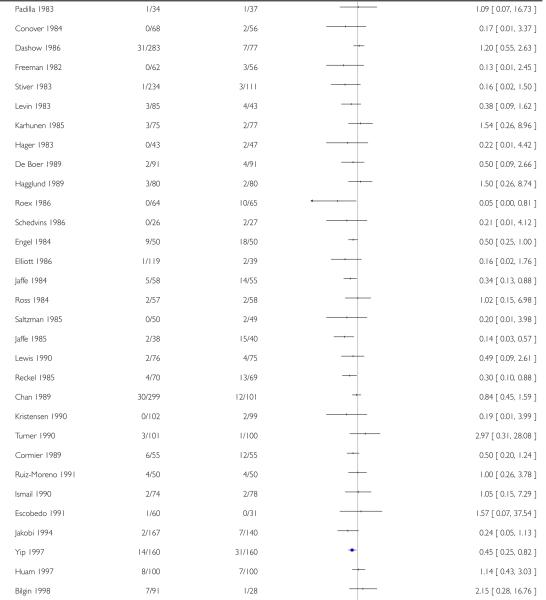

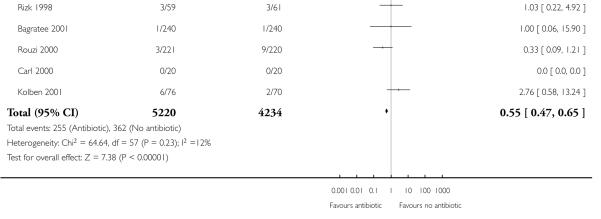

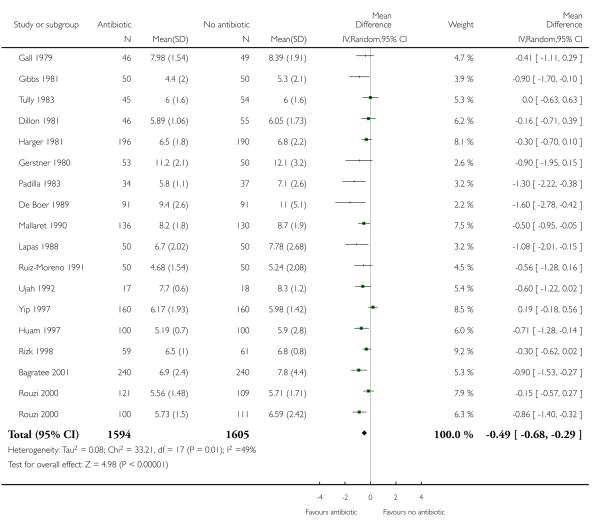

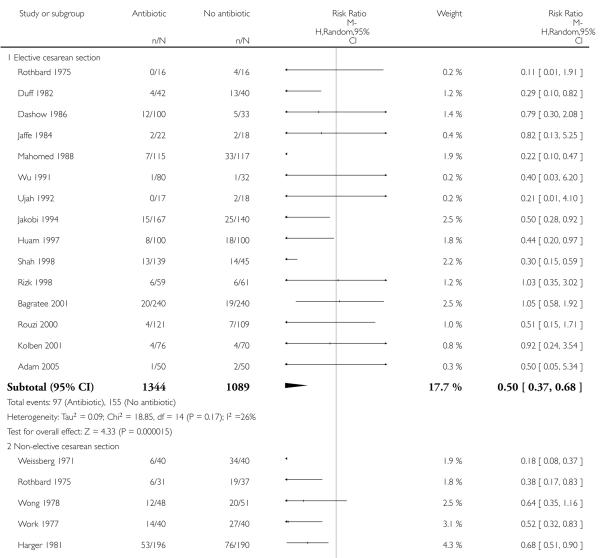

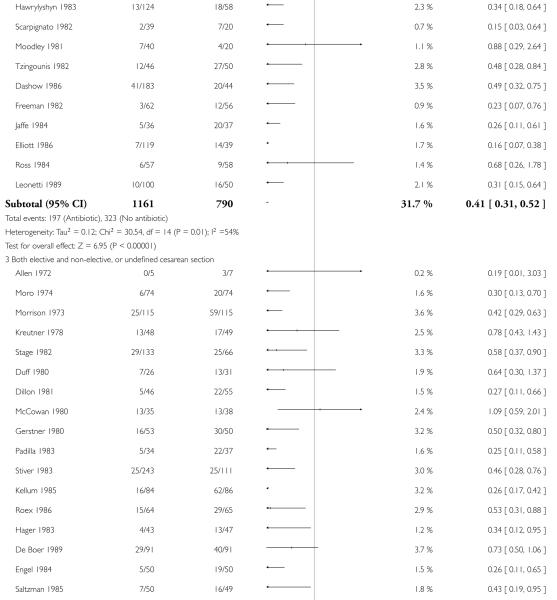

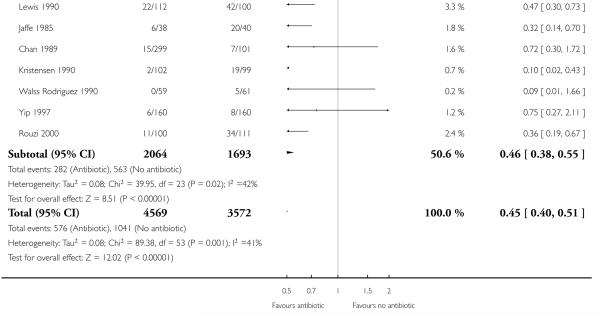

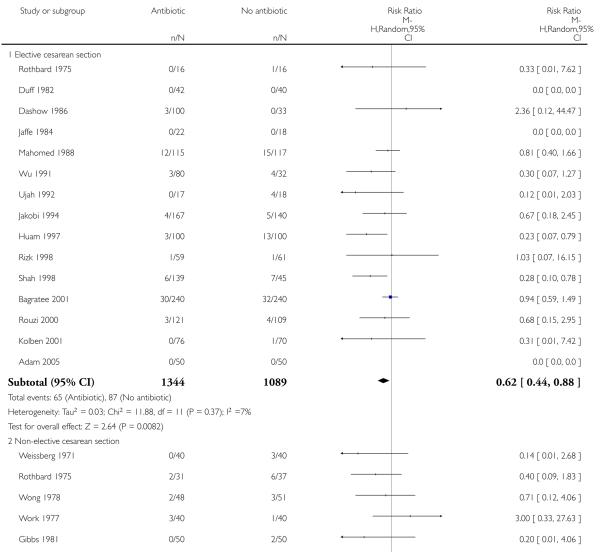

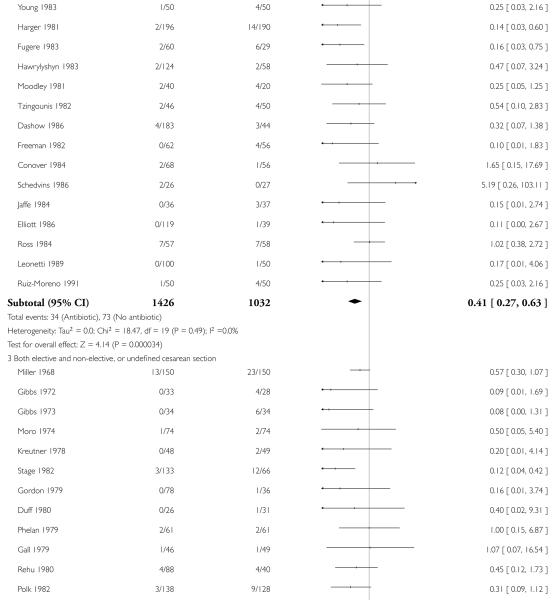

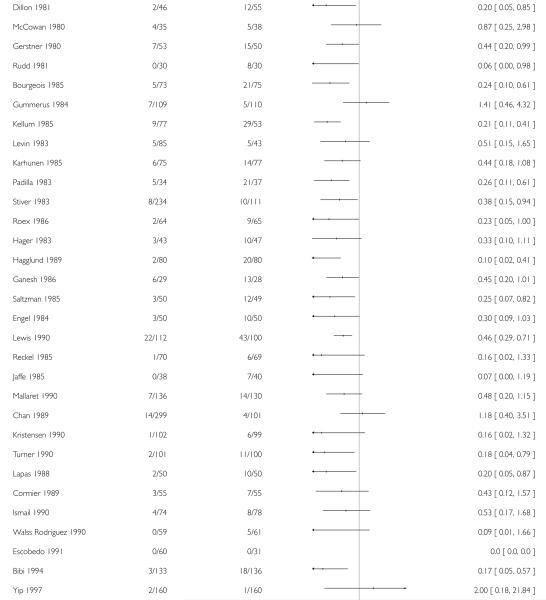

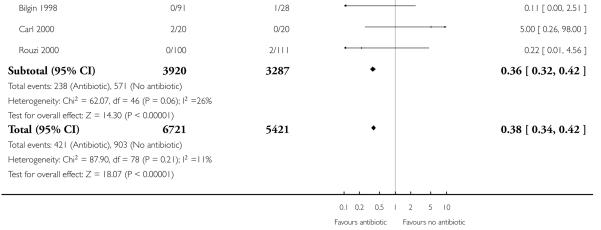

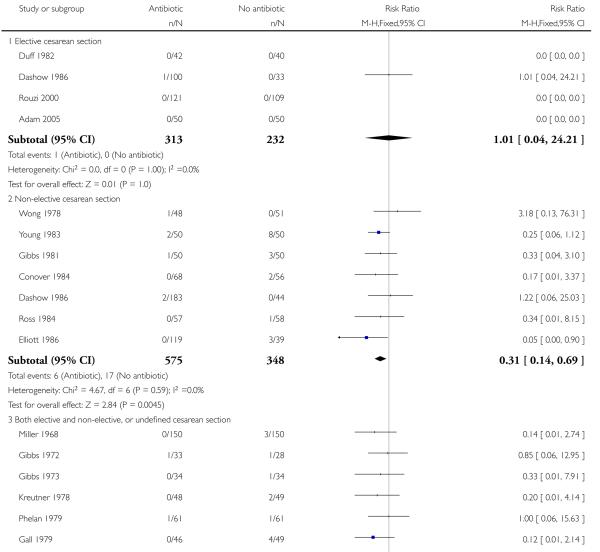

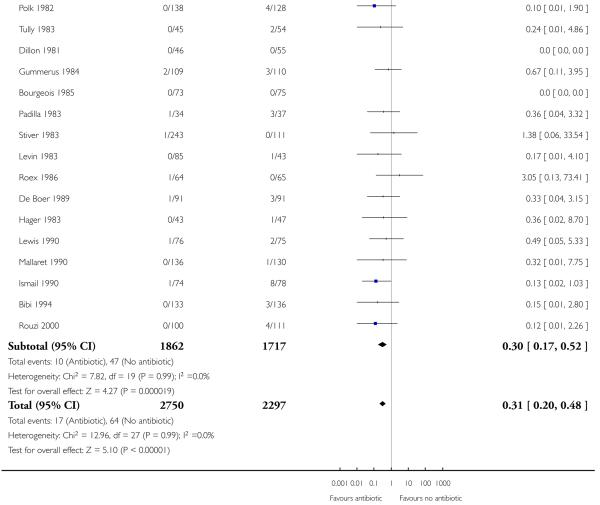

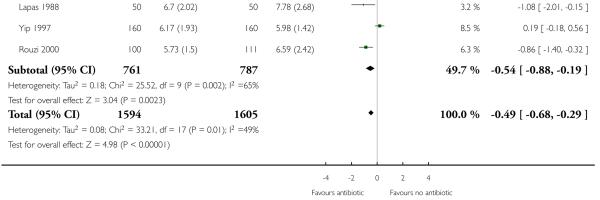

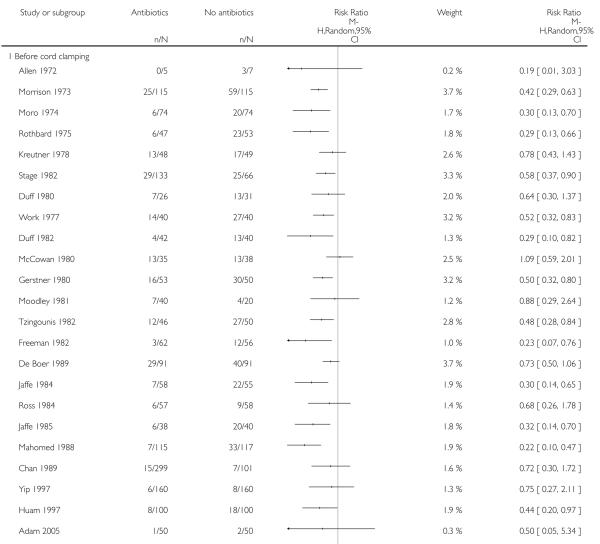

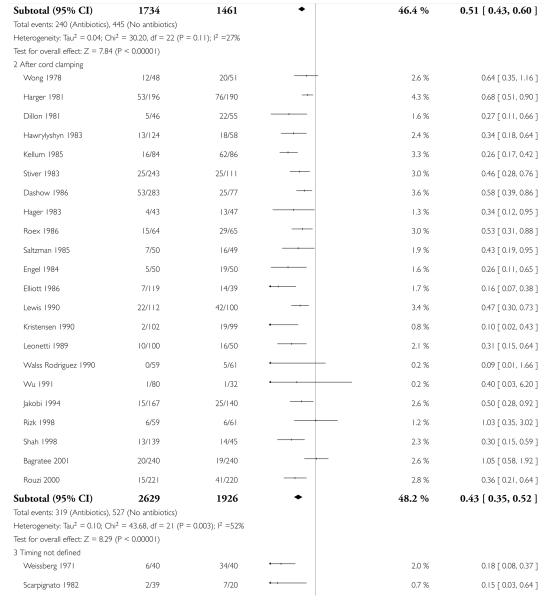

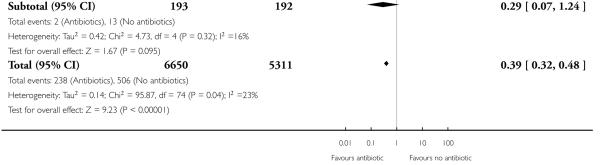

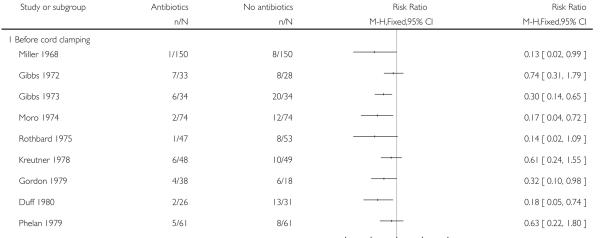

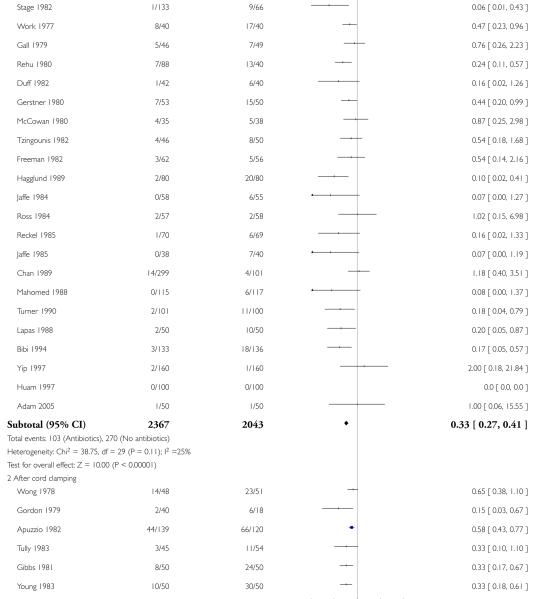

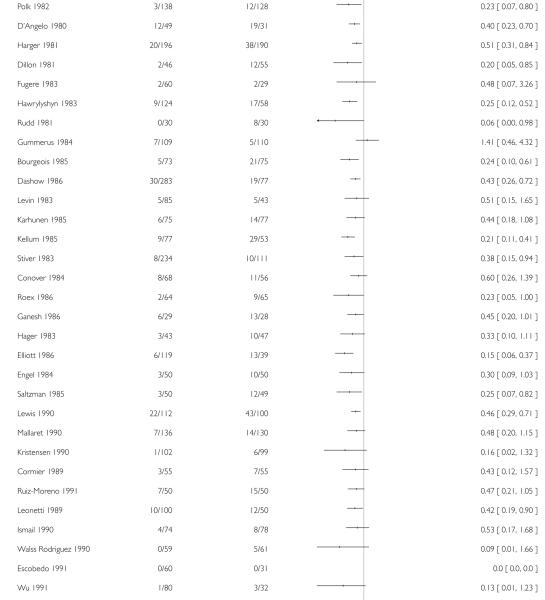

There were reductions in all the maternal primary outcomes: febrile morbidity (average risk ratio (RR) 0.45; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.39 to 0.51, 50 studies, 8141 women, random-effects [T2 = 0.09; Chi2 P = 0.0005; I2 = 45%], Analysis 1.1); wound infection (average RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.32 to 0.48, 77 studies, 11,961 women, random-effects [T2 = 0.14; Chi2 P = 0.04; I2 = 23%], Analysis 1.2); endometritis (RR 0.38; 95% CI 0.34 to 0.42, 79 studies, 12,142 women, Analysis 1.3) and serious infectious morbidity (RR 0.31; 95% CI 0.19 to 0.48, 31 studies, 5047 women, Analysis 1.4).

There were no data in any of the studies on the two infant primary outcomes of immediate adverse effects and infant thrush.

Secondary outcomes

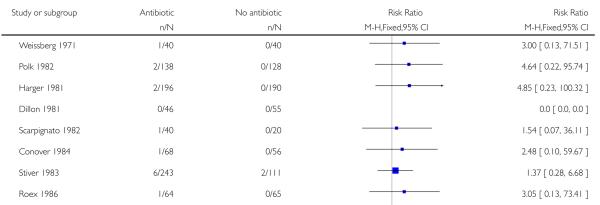

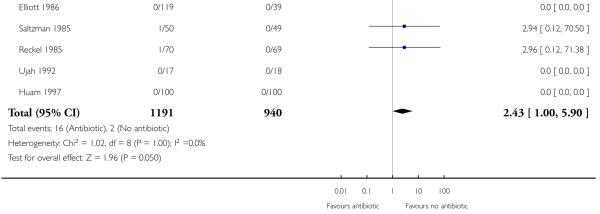

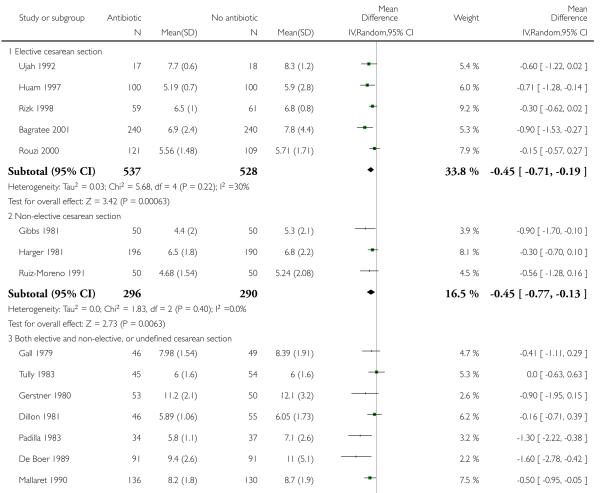

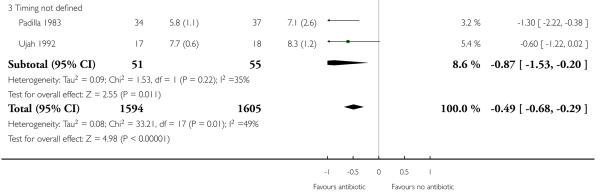

There were reductions in both maternal urinary tract infection (RR 0.55; 95% CI 0.47 to 0.65, 61 studies, 9454 women, Analysis 1.7) and maternal length of stay in hospital (average mean difference (MD) −0.49; 95% CI −0.29 to −0.68, 17 studies, 3199 women, [T2 = 0.08; Chi2 P = 0.01; I2 = 49%], Analysis 1.9). Only 13 studies collected data on maternal adverse effects and suggested either an increase or no detectable effect (RR 2.43; 95% CI 1.00 to 5.90, 13 studies, 2131 women, Analysis 1.8).

There were no data in any of the studies on the other secondary outcomes.

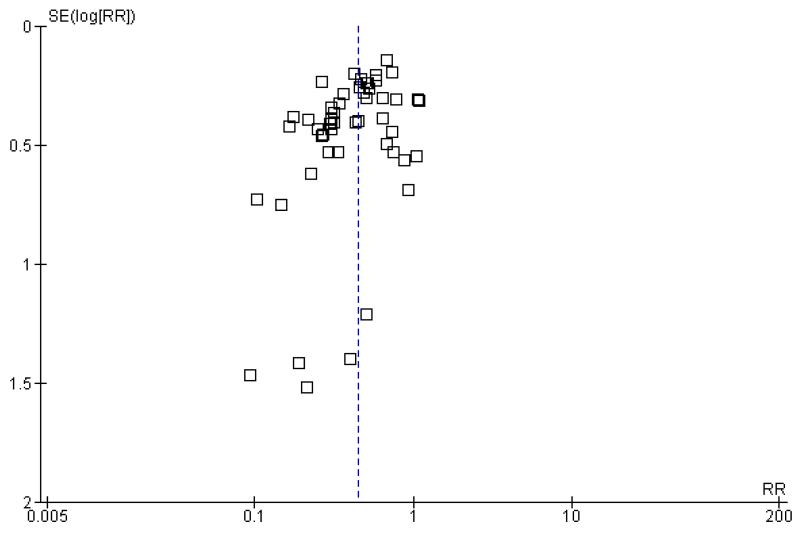

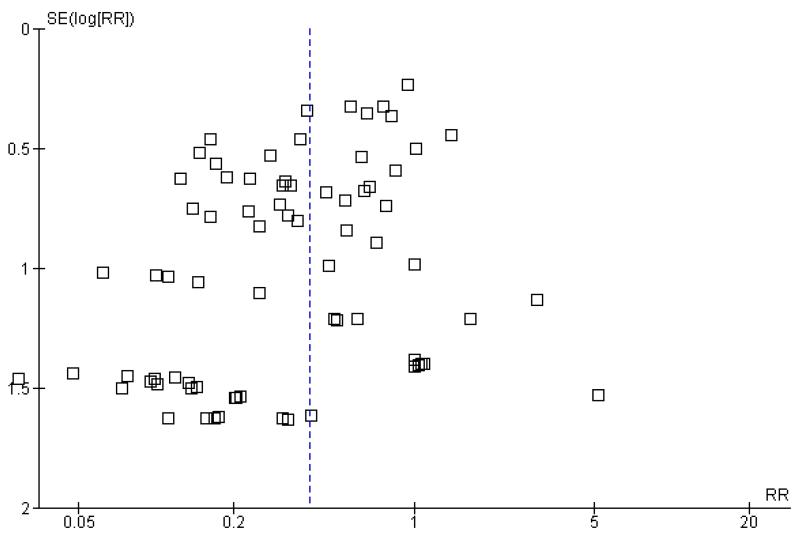

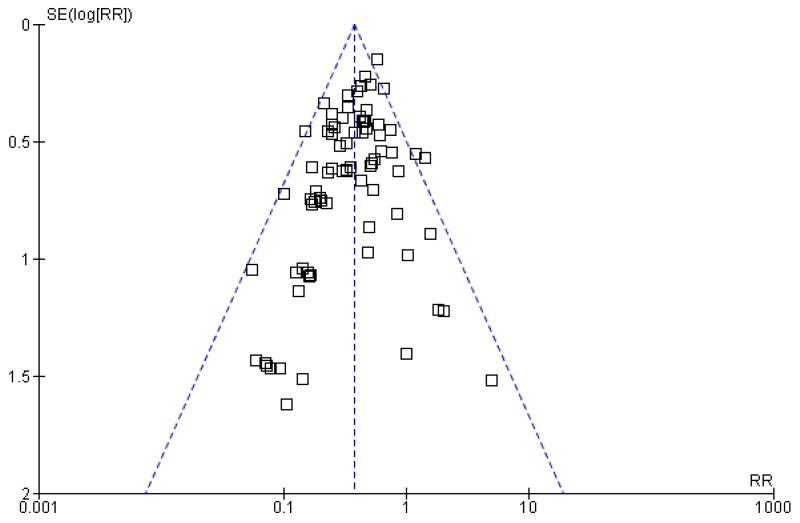

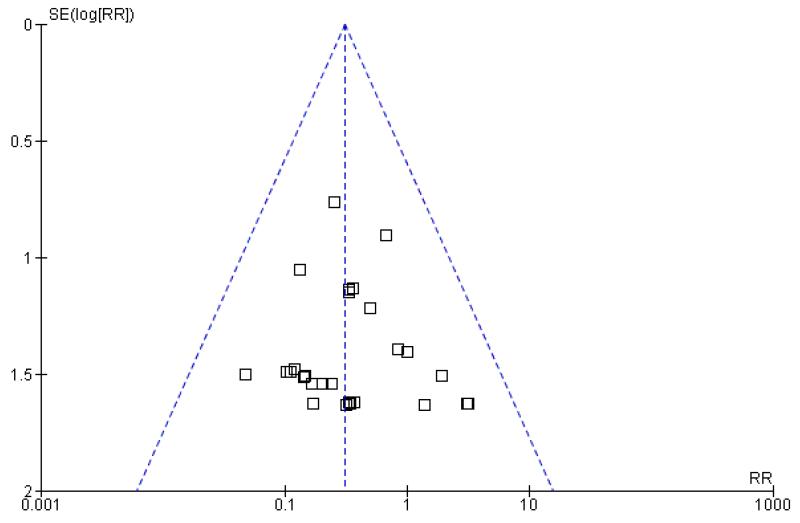

Reporting bias

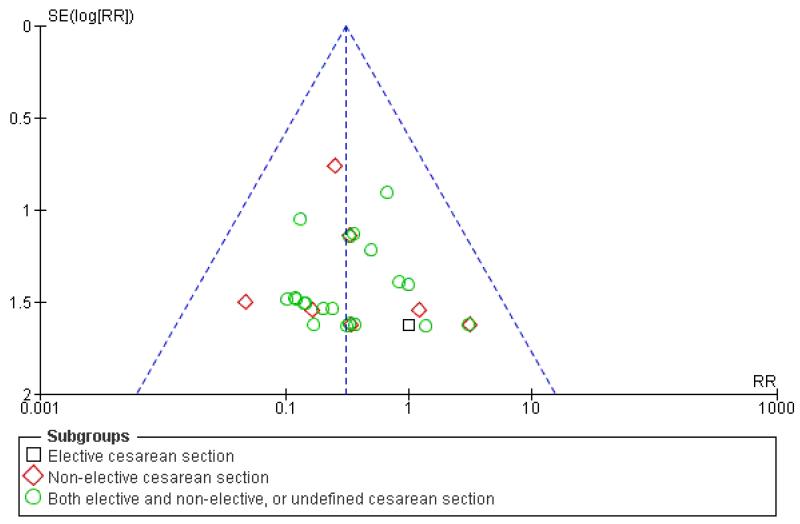

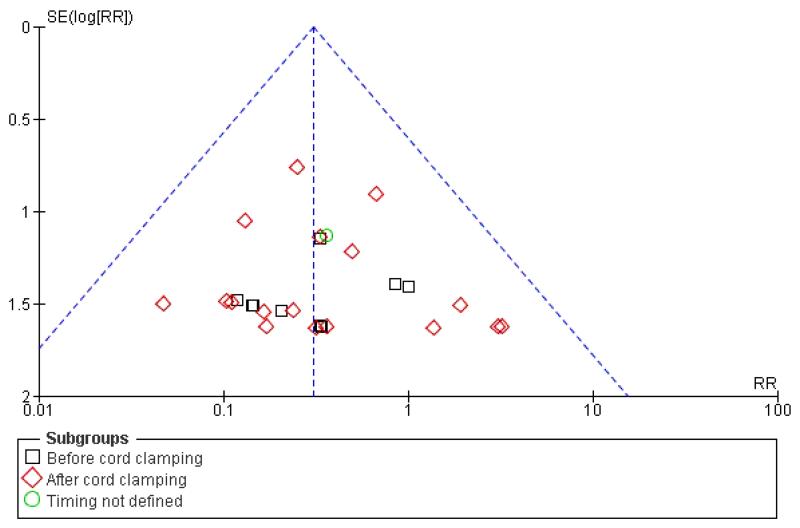

There was a potential for publication bias in the assessment of febrile morbidity, as judged by visual inspection of the funnel plot (Figure 3); however, we estimated that any reporting bias was unlikely to influence the results because of the large number of participants in the symmetrical part of the plot. There was no funnel plot asymmetry for the other primary outcomes (Figure 4; Figure 5; Figure 6).

Figure 3. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis, outcome: 1.1 Maternal fever/febrile morbidity.

Figure 4. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis, outcome: 1.2 Maternal wound infection.

Figure 5. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis, outcome: 1.3 Maternal endometritis.

Figure 6. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis, outcome: 1.4 Maternal serious infectious complications.

Study quality

We undertook a sensitivity analysis on the primary outcomes by study quality, omitting the seven quasi-RCTs (Bilgin 1998; Freeman 1982; Huam 1997; Kellum 1985; Morrison 1973; Rothbard 1975; Turner 1990). The overall findings remained very similar with reductions all the primary outcomes: febrile morbidity (average RR 0.46; 95% CI 0.40 to 0.53, 45 studies, 7323 women, random-effects [T2 = 0.09, Chi2 P = 0.001, I2 = 44%]; wound infection (average RR 0.41; 95% CI 0.33 to 0.50, 72 studies, 11,223 women, random-effects [T2 = 0.14, Chi2 P = 0.05, I2 = 23%); endometritis (RR 0.39; 95% CI 0.35 to 0.43, 73 studies, 11,274 women) and serious infectious morbidity remained the same as the main analysis contained no quasi-RCTs.

2. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis, subgroups by type of cesarean section (Analyses 2.1 to 2.14)

We inspected the graphs visually and saw no difference in maternal febrile morbidity, wound infection or endometritis, and as well the confidence intervals for the summary estimates overlapped. These results suggest that there are benefits for the mother irrespective of whether the cesarean section is elective or emergency.There were insufficient data to assess any potential differential effect on maternal serious infectious complications. As above, there were no outcomes assessed on the infants in any of these studies.

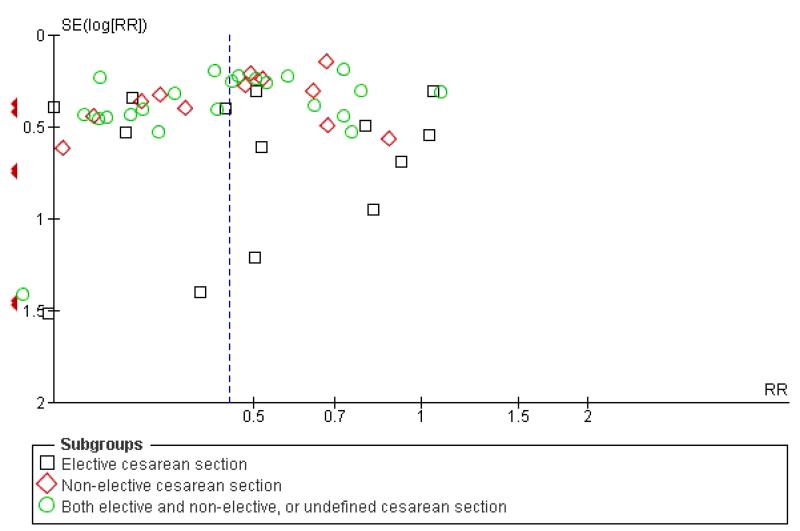

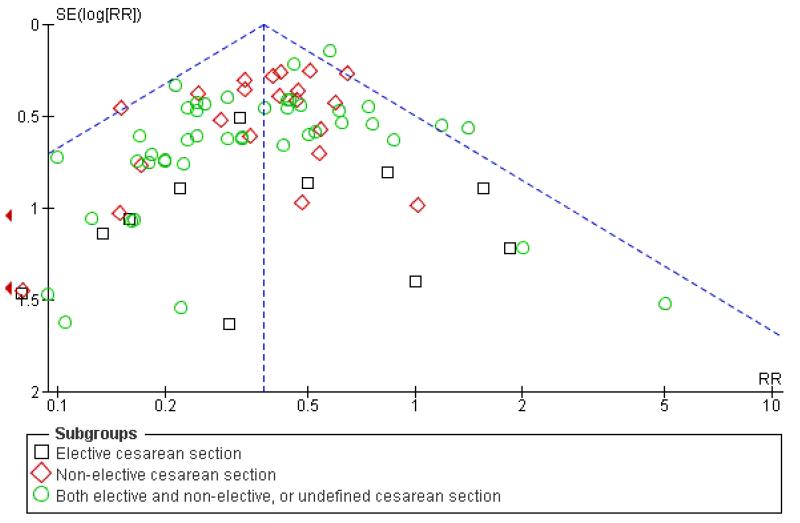

Reporting bias

As judged by a visual inspection of the funnel plot, there was a potential for publication bias in certain outcomes (e.g. febrile morbidity) (Figure 7; Figure 8; Figure 9; Figure 10).

Figure 7. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by type of cesarean section, outcome: 1.1 Maternal fever/febrile morbidity.

Figure 8. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by type of cesarean section, outcome: 1.2 Maternal wound infection.

Figure 9. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by type of cesarean section, outcome: 1.3 Maternal endometritis.

Figure 10. Funnel plot of comparison: 1 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by type of cesarean section, outcome: 1.4 Maternal serious infectious complications.

3. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis, subgroups by timing of administration (Analyses 3.1 to 3.14)

We inspected the graphs visually and found no difference in maternal febrile morbidity, wound infection or endometritis, and as well the confidence intervals for the summary estimates overlapped. The results were similar for maternal serious infectious complication although there were insufficient data to conclude this with certainty. One of the reasons for looking at the different timing of administration was to assess any impact of antibiotic reaching the baby if given before cord clamping. However, none of the studies assessed outcomes on the baby.

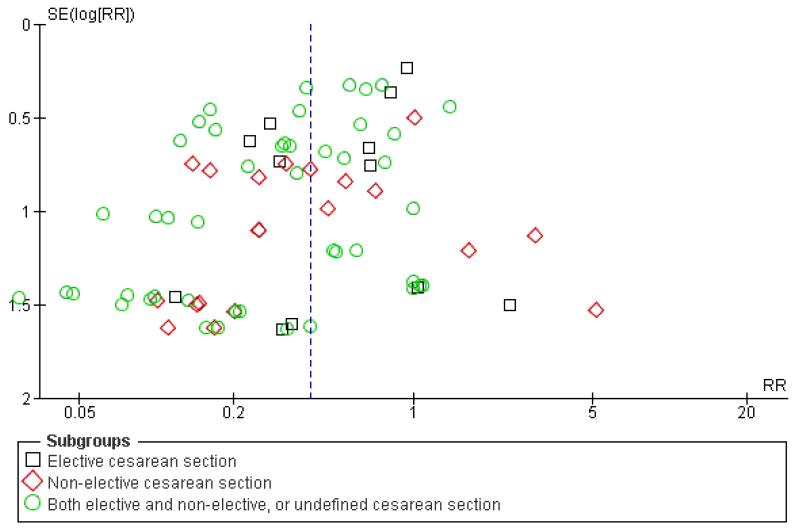

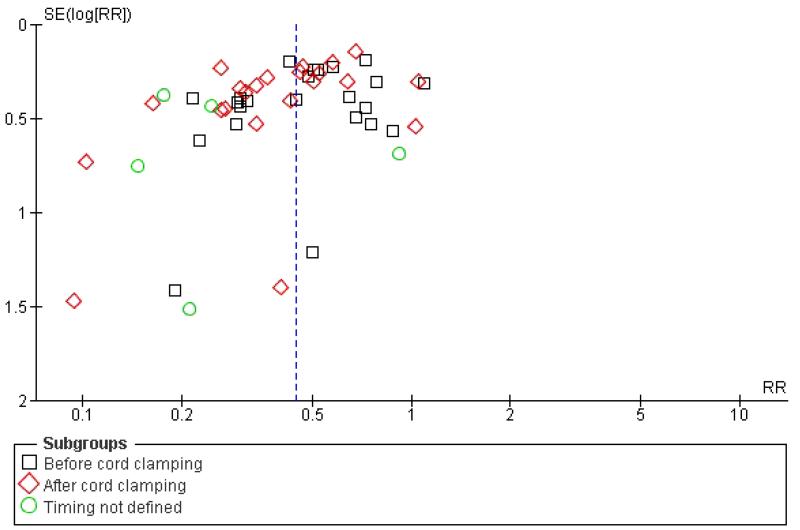

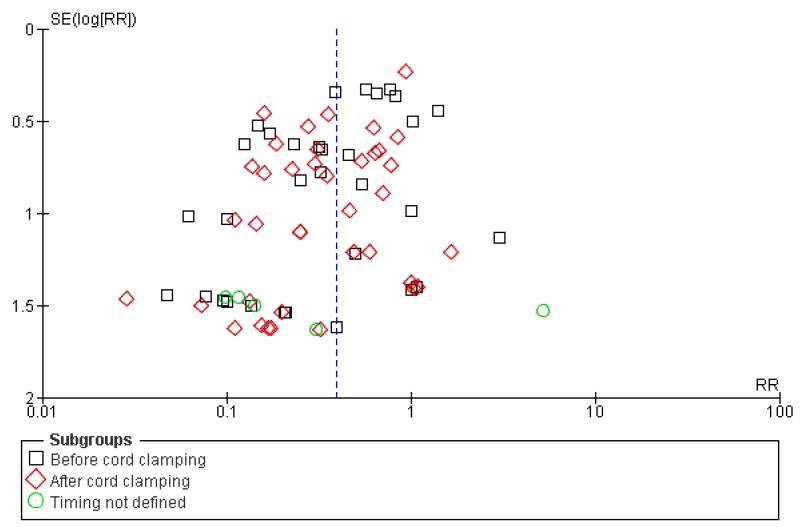

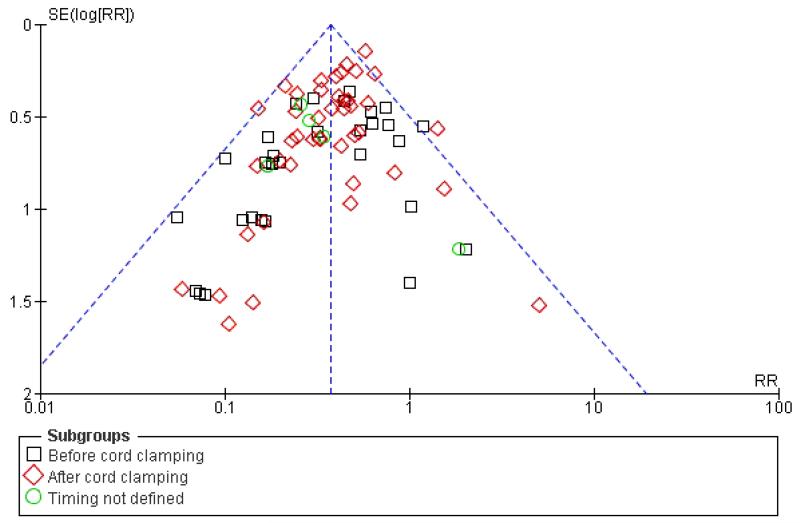

Reporting bias

There was a potential for publication bias in the assessment of febrile morbidity as assessed by visual inspection of the funnel plot (Figure 11), while the other primary outcomes appeared to have funnel plot symmetry (Figure 12; Figure 13; Figure 14).

Figure 11. Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by timing of administration, outcome: 2.1 Maternal fever/febrile morbidity.

Figure 12. Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by timing of administration, outcome: 2.2 Maternal wound infection.

Figure 13. Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by timing of administration, outcome: 2.3 Maternal endometritis.

Figure 14. Funnel plot of comparison: 2 Antibiotics versus no antibiotics - by timing of administration, outcome: 2.4 Maternal serious infectious complications.

Other considerations

Infant

Infant outcomes were infrequently reported. No study reported on any long-term adverse effects on the infant or effect of antibiotics on the infant immune system. In addition, no studies reported on the incidence of oral candidiasis (thrush) in babies which we had categorized as an adverse outcome.

Where Apgar scores were reported, there were no differences between the treatment and control groups (Adam 2005; Gordon 1979; Ng 1992; Rouzi 2000). One study collected information on birthweight, number of days in hospital, admission to neonatal intensive care, early neonatal death, respiratory distress syndrome and neonatal sepsis and there was no difference between the treatment and control groups (Rouzi 2000). Some authors stated there were no complications in the babies due to drug administration, without further details (Gordon 1979; Moodley 1981) and that the administration of antibiotics did not interfere with routine paediatric cultures (Gall 1979) or the evaluation of newborn sepsis (Duff 1980).

There were few neonatal deaths and where they were reported, no relationship to the administration of antibiotic was reported (Adam 2005; De Boer 1989).

Only one study reported on infant outcomes at four weeks and in that study the three infants who had complications were all in the control group (Gordon 1979).

Costs

Two studies reported on this outcome, but the data were in a format that we could not include in this review (Kristensen 1990; Mallaret 1990). See Characteristics of included studies table for details of costs.

Resistance

Changes in bacterial flora and the development of antibiotic resistant bacteria with the administration of antibiotics was not systematically collected in the studies included in this review, but several studies included detailed microbiological investigations, comparing the results of aerobic and anaerobic culture of the genital tract before and after the surgery and reporting on antimicrobial resistance in organisms associated with infection (Engel 1984; Fugere 1983; Gibbs 1981; Harger 1981; Ismail 1990; Karhunen 1985; Kreutner 1978; Miller 1968; Moro 1974; Rothbard 1975; Roex 1986; Stiver 1983).

There is a shift in the bacterial flora following the surgical procedure itself and return to the non-pregnant state and even in the control groups more gram positive aerobic organisms (including staphylococcal species and enterococci) were observed post-operatively (Engel 1984). Antibiotic prophylaxis was associated with increases in enterococci and gram-negative aerobic organisms (Engel 1984; Fugere 1983; Gibbs 1981; Kreutner 1978); cefazolin was associated with more anaerobic isolates (Engel 1984; Fugere 1983; Kreutner 1978) and cefoxitin and cefamandole with a decrease in anaerobic isolates (Engel 1984; Gibbs 1981).

Given that most regimens included a cephalosporin which has no activity against enterococci, it is not surprising that most studies reported significant increases in enterococcal colonization (Gibbs 1981; Ismail 1990; Stiver 1983). Harger reported that the isolates from infected sites in cefoxitin infected women showed a relative predominance of enterococci (Harger 1981). Ismail reported that enterococcal sepsis occurred in one patient and three others had significant enterococcal bacteriuria or urinary tract infection (Ismail 1990).

There were very few reports of resistant organisms developing following prophylaxis. No cefoxitin resistant strains of Enterobacteriaceae were isolated from stool samples after prophylaxis (Ismail 1990). In one study, there were more ampicillin resistant urinary tract infections when ampicillin was used for prophylaxis (9/17 versus 8/26) compared with control (Miller 1968). Rothbard reported one infection with an organism resistant to cephalothin and kanamycin used for prophylaxis (Rothbard 1975) and Duff reported an endometrial culture that grew Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to ampicillin (Duff 1980). Engel reported urinary tract infections with mezlocillin resistant organisms (5/9) after mezlocillin prophylaxis and observed colonization with mezlocillin resistant strains of E. coli in cultures from the cervix (Engel 1984). In one study of cephalothin, all the organisms causing infection in the antibiotic group were described as sensitive to cephalothin in vitro (Moro 1974). In a study of cefoxitin prophylaxis, it was observed that the changes in endogenous flora were not associated with overgrowth of resistant pathogens, such as Pseudomonas, enterococci or Enterobacter (Roex 1986) and Karhunen reported no superinfections with resistant anaerobic organisms when tinidazole was used for prophylaxis (Karhunen 1985). Striver confirmed that there was no increase in nosocomial infection (Stiver 1983).

DISCUSSION

Summary of main result

In the 86 studies included in this review, the use of prophylactic antibiotics in women undergoing cesarean section substantially reduced the incidence of febrile morbidity, wound infection, endometritis, urinary tract infection, and serious infection after cesarean section. Whether considering only elective cesarean sections or non-elective cesarean section, the risk ratios for the effect of antibiotics is remarkably similar for the outcome of endometritis. There is a similar close clustering of risk ratios for the outcome of febrile morbidity between subgroups. Seventy-seven studies reported on the outcome of wound infection. Antibiotic treatment was associated with a statistically significant reduction in wound infection in both the elective and non-elective subgroups.

Using an episode of bacteremia and any other serious infectious morbidity as defined by the authors (except a prolonged febrile episode) as the definition of a serious outcome, antibiotic treatment was associated with a significant reduction for non-elective deliveries. A difference in serious outcomes could not be demonstrated for the elective deliveries. There were no deaths reported in any group.

Data were available on maternal length of stay for 17 studies. Overall, hospital stay was reduced in the antibiotic treated group and was significant in each of the subgroups. Duration of stay in the group receiving treatment ranged from 4.4 to 11.2 days, and for the no treatment group 5.2 to 12.1 days.

Febrile morbidity is common after cesarean section and was reduced with the use of prophylactic antibiotics. Few of these women will have positive bacterial cultures or a specific indication for antimicrobial treatment, but these women often have specimens collected and empiric antibiotic therapy started. This review could not address the costs of antibiotic prophylaxis. However, in those studies that did report the rate of the additional use of antibiotics or costs, or both, there were significant differences with more days of antibiotics being prescribed to the women who had not received prophylaxis. In the two studies that reported post-operative antibiotic costs, costs were lower in the group receiving prophylaxis compared with the control group (Kristensen 1990; Mallaret 1990).

No conclusions can be made from this review about the relative effectiveness of different antibiotic regimens (see review ‘Antibiotic prophylaxis regimens and drugs for cesarean section’ (Hopkins 1999)).

Description of studies

The women included in these trials varied greatly in their risk of infection, ranging from 0% to 61.30% for the outcome of endometritis. Similar wide variability in the incidence of the other outcomes (febrile morbidity, wound infection, urinary tract infection) was seen among the studies.

Because the estimate of the number of women needed to treat to prevent one infection will depend on the baseline risk of infection, fewer women undergoing an emergency section, where the risk of infection is higher, are needed to be treated to prevent an infectious outcome than women undergoing an elective procedure.

Adverse effects

Maternal side effects were not consistently collected nor reported. Overall, there were two episodes in the placebo or untreated group (0.2%) compared with 16 in the treated groups (1.3%) but the differences were not statistically significant. The most common side effect was rash, followed by phlebitis at the site of the intravenous infusion. There were no serious drug-related adverse events reported.

Infant outcomes were rarely systematically collected but when they were reported there was no evidence of any adverse effects associated with the administration of antibiotic. There is evidence that antibiotics given near or shortly after birth can affect the infant gut flora, with the potential to impact mucosal and systemic immune function (Bedford Russell 2006) but no study has prospectively examined the effect of any changes in flora on these or other outcomes. Oral yeast infection (thrush) was not an outcome reported in any of the included studies.

There were changes in bacterial flora with an increase in enterococcal colonization and examples of the development of antibiotic resistant bacteria with the administration of antibiotics, but few incidences where this was associated with infectious complications.

Generally the side effects of a single antibiotic dose are mild, but rarely serious allergic reactions can occur and be fatal. Although the risk of side effects reported in these studies was low, these data were incompletely collected, making it difficult to know accurately the incidence of the adverse effects of treatment. There are also unknown and unquantified effects of antibiotic use that include changing the normal maternal flora, effects on the presentation of infection in the infant, and the development of antimicrobial resistance. There is evidence that the cervicovaginal flora is altered in women undergoing cesarean section, whether antibiotics are used or not, but no problems with managing resistant organisms in this setting have been recognized (Galask 1987).

While increased use of antimicrobial prophylaxis may be one factor in increasing antimicrobial resistance (Shlaes 1997), there are no data supporting the contention that appropriate use of short course antimicrobial prophylaxis will cause significant bacterial resistance nor evidence that a policy of antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean section has harmful effects that outweigh its benefits, even in those women perceived to be at low risk. Optimizing the choice and the duration of prophylactic antibiotic therapy is recommended as one strategy to prevent antimicrobial resistance (Shlaes 1997). Trends in antibiotic resistance should be monitored, reported and used to establish practice guidelines and monitor institutional policies. Susceptibility testing of significant bacterial isolates should guide antimicrobial therapy of individual women who develop infection despite prophylaxis.

Timing of antibiotic administration

A statistically significant reduction in all the primary outcomes (febrile morbidity, wound infection, endometritis, serious maternal outcomes) was seen whether the antibiotic was administered before the clamping of the cord or after clamping of the cord. There was no significant difference in the estimates for these outcomes by the timing of administration and the confidence intervals were overlapping. It has, however, been shown that the lowest risk of surgical wound infection is associated with antibiotics administered in the pre-operative period as compared with the perioperative or post-operative period (Classen 1992). Although a number of small studies did not show an increase in infectious outcomes when the antibiotic was administered after the cord was clamped (Cunningham 1983; Gordon 1979; Wax 1997), a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials concluded that there was strong evidence that antibiotic prophylaxis given before skin incision decreased the incidence of postpartum endometritis and total infectious morbidities (Costantine 2008). Pre-operative administration of antibiotics did not significantly affect proven neonatal sepsis, suspected sepsis or neonatal intensive care unit admissions. In a retrospective study on the effect of a change in policy to administer prophylactic antibiotics before skin incision, the overall rate of surgical site infections fell from 6.2% to 2.5% (Kaimal 2008).

Quality of the evidence

Overall the methodological quality of the trials on the whole was unclear and there was the potential for publication bias. In only 8% of studies was it judged that the overall risk of bias was low (Bagratee 2001; Bourgeois 1985; Dashow 1986; Levin 1983; Rouzi 2000; Rudd 1981; Tully 1983). Most of the studies were undertaken in the 1970s and 1980s, before the recent understanding of sources of bias in randomised controlled trials and in most studies insufficient information was provided in the paper to adequately judge the risk of bias.

Consistency of the results

The results of the trials included in this review are, however, remarkably consistent, both in direction of effect and in effect size, despite some heterogeneity identified. Overall, the use of prophylactic antibiotics with cesarean section results in a major, clinically important, and statistically significant reduction in the incidence of episodes of febrile morbidity, wound infection, endometritis, urinary tract infection and serious infection after cesarean section.

Only the incidence of urinary tract infection in women undergoing an elective cesarean section was not statistically significant and there were too few serious infectious outcomes in women undergoing an elective cesarean section to analyse.

Agreement and disagreement with other studies or reviews

This review included in its definition of an elective cesarean section those women not in labor but with ruptured membranes for less than six hours, included studies that did not have a placebo arm and included studies that used antibiotic irrigation as well as systemic agents. A meta-analysis (Chelmow 2001) that used an expanded search strategy to identify additional relevant studies, and included only placebo-controlled studies of systemic antibiotics in women undergoing elective cesarean section who were non-laboring with intact membranes, showed a reduction in infections in this low-risk population and supports the conclusion of this review.

Implementation of findings

Inconsistent adherence to policies for administering antibiotic prophylaxis are reported (Huskins 2001; Mah 2001; Pedersen 1996) but simple quality improvement methods have been demonstrated to improve adherence with overall and timely administration of prophylaxis and reduce the infection rate (Weinberg 2001). It was also shown, in this study (Weinberg 2001) that a program that introduced a policy of universal prophylaxis for all women undergoing a cesarean section was more effective than one that required the obstetrician to decide whether a woman was high risk and mandated prophylaxis only for the high-risk women. In a prospective cohort study from a high-risk obstetrical unit in New York state, absence of antibiotic prophylaxis was identified by multiple logistic regression analysis as being independently associated with surgical site infection after cesarean section for both high-risk women and low-risk women and was identified as one of two modifiable factors (the other being fewer prenatal visits) (Killian 2001).

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS

Implications for practice

Prophylactic antibiotics reduced the incidence of endometritis following both elective and non-elective cesarean section by two thirds to three quarters and the incidence of wound infection by up to three quarters. Postpartum febrile morbidity and the incidence of urinary tract infections are also decreased. Fewer serious complications were identified. The administration of prophylactic antibiotics before or after clamping of the cord for women undergoing cesarean section seemed equally effective. However, studies did not assess potential adverse effects on the baby and the rates of oral thrush were not reported. Obstetrical units should collect information on infection rates following cesarean section as an important quality indicator.

Implications for research

Further placebo controlled trials of the effectiveness of antibiotics with cesarean section are not ethically justified, but studies are needed to ascertain infant outcomes. Any future studies should use the list of outcomes identified here as a minimum data set and, in particular, include possible adverse effects on the infant. There should be research on methods to implement effective policies of prophylaxis for women undergoing cesarean section. Rates of infection following cesarean section are higher than for many other surgical procedures, even with a policy of uniform prophylaxis. Future research should look at interventions to reduce further the incidence of infection from that achieved with our current approach to antibiotic prophylaxis, e.g. the topical vaginal administration of metronidazole (Pitt 2001), the timing of antibiotic administration, whether there are advantages to an extended spectrum regimen (Tita 2009) and determine the role of surgical technique, pre- and intra-operative preparation and infection control policies on infection rates.

There is a theoretical opportunity for a cost-effective analysis to be performed in a unit where routine prophylactic antibiotics are not administered to women undergoing an elective cesarean section and where the risk of infection is very low, in an attempt to identify women at increased risk of infection in whom prophylaxis may be cost-effective. However, there is currently no evidence to support such a strategy. Because of local variation in practice and women, the results of such research will likely only be applicable to an individual unit and not generalizable.

There is a need for more information about the role of bacterial vaginosis and infectious complications following cesarean section, the significance of organisms such as Ureaplasma and whether these have implications for current prophylactic recommendations.

Better data on the safety of the intervention for the mother and infant are needed, particularly longer-term effects on the infant. Studies should be undertaken to determine what role antimicrobial prophylactic regimens have in the development of antimicrobial resistance. Research into the perceptions of the advantages and disadvantages of the intervention from the perspective of the woman and the healthcare provider will help define educational and research needs.

PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY.

Routine antibiotics at cesarean section to reduce infection

Women undergoing cesarean section have a five to 20-fold greater chance of getting an infection compared with women who give birth vaginally. These infections can be in the organs within the pelvis, around the surgical incision and sometimes the urine. The infections can be serious, and very occasionally can lead to the mother’s death. The potential benefits of reducing infection for the mother need to be balanced against adverse effects such as nausea, vomiting, skin rash and rarely allergic reactions in the mother, and the risk of thrush and any effect of antibiotics on the ‘friendly’ gut bacteria in the baby. This review looked at whether antibiotics are effective at elective and emergency cesarean sections. It also studied the effect of giving the antibiotics before or after the cord is clamped. The review found 86 studies involving over 13,000 women. Routine use of antibiotics at cesarean section reduced the risk of fever and of wound, womb and urine infections in mothers. It also reduced the risk of serious complications of infections for the mothers. This was so whether the cesarean section was elective or emergency, and whether the antibiotics were given before or after clamping of the umbilical cord. However, none of the studies looked properly at possible adverse effects on the baby, for example, whether its use increased the risk of thrush. Similarly, it was unclear whether the routine use of antibiotics at cesarean section would contribute to increasing drug resistant strains of bacteria. Studies are needed on these two aspects of this intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Justus Hofmeyr was an author on the previous versions of this review. He helped with writing of the Background section, identifying the studies for inclusion and with the data extraction of the original data. He also provided guidance on the updating of the review. Lei Dou helped with assessing the risk of bias in the studies in the previous version of the review (Smaill 2002).

We wish to thank Kate Barton, Caroline Brooke, Simon Claessens, Kornelia DeKorne, Violeta Dimova-Nikols, Rebecca Gainey, Alison Jenner, Agnieszka Kimball, Ben Lamy, Austin Leirvik, Melissa Slavick, Caroline Summers, Maria Tenorio, Jean Tsang, Kyle Wark and Elizabeth Whiteley for translating articles relevant to this review.

As part of the pre-publication editorial process, this review has been commented on by three peers (an editor and two referees who are external to the editorial team), a member of the Pregnancy and Childbirth Group’s international panel of consumers and the Group’s Statistical Adviser.

Appendix

CHARACTERISTICS OF STUDIES

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

| Methods | RCT, 2 parallel groups. | |

| Unit of randomization: individual. | ||

| Participants | Dates of data collection: Sept 2003 - April 2004. | |

| Setting: New Halfa Teaching Hospital, Eastern Sudan. | ||

| Inclusion criteria: planned elective CS (categorized as elective) | ||

| Exclusion criteria: antibiotics within 2 weeks; any visible infection; elevated temperature; allergic to antimicrobials; did not wish to participate | ||

| Interventions | Ceftriaxone 1 g IV at anesthetic induction vs no treatment. | |

| Outcomes | Post-operative febrile morbidity (oral temperature ≥ 38 °C twice at least 4 hours apart after first 24 hours | |

| Post-operative infections (endometritis, wound infection, pelvic abscess, peritonitis, other febrile morbidity (UTI, chest infection, malaria) | ||

| 2 perinatal deaths: 1 in each group due to respiratory distress and septicaemia due to imperforate anus | ||

| Notes | Developing country. | |

| Class of antimicrobial: third generation cephalosporin. | ||

| Subgroups: | ||

|

||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | “Patients were randomized.” |

| No additional details. | ||

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No information. |

| Blinding? | No | No blinding. |

| All outcomes | Not placebo-controlled. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? | Yes | No loss of participants to follow up. |

| All outcomes | No participant excluded after randomization. | |

| ITT analysis. | ||

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to judge. |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | “The 2 groups were well matched at enrolment and there were no statistical differences in the admission variables.” |

| There was insufficient other information which to judge. | ||

| Overall low risk of bias? | No | Very little information provided, particularly around allocation concealment and it appears not placebo controlled |

| Methods | RCT; 2 parallel groups. | |

| Unit of randomization: individual. | ||

| Participants | Dates of data collection: not reported. | |

| Setting: University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria. Majority of patients from low socioeconomic class | ||

| Inclusion criteria: both elective and non-elective cesarean deliveries | ||

| Exclusion criteria: fever or obvious infection before operation | ||

| Interventions | Ampicillin 500 mg before operation and 250 mg 6 hourly for at least 7 days (IM until able to take orally) (N = 58) vs no antibiotics unless temperature 38 degrees C after the third post-operative day (N = 48). Both groups received curative doses of chloroquine | |

| Outcomes | Wound infection; UTI (not defined further); ’genital sepsis’ (not defined further: study group 5/58; control group 15/48) | |

| Notes | Prophylaxis continued for 7 days. | |

| Class of antibiotic: Aminopenicillin (ampicillin). | ||

| Subgroups | ||

|

||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | ‘Divided randomly into 2 groups.’ |

| No additional details. | ||

| Allocation concealment? | Unclear | No information was provided. |

| Blinding? | Unclear | Not placebo-controlled. |

| All outcomes | No additional details. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? | Unclear | No loss to follow up reported. |

| All outcomes | No participants excluded; imbalance in group size not accounted for (58 vs 48) | |

| ITT analysis. | ||

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to judge. |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | The 2 groups were comparable regarding age, parity and indications for CS |

| Overall low risk of bias? | Unclear | Very little information provided to assess risk of bias. |

| Methods | Randomized, placebo controlled trial; 2 parallel groups. | |

| Unit of randomization: individual. | ||

| Participants | Dates of data collection: August 1970 - January 1971. | |

| Setting: Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, US; | ||

| Inclusion criteria: women undergoing CS (criteria not specified) | ||

| Exclusion criteria: evidence of clinical infection, history of penicillin allergy | ||

| Interventions | Cephalothin 1 g IV on call to operating room, further 2 g IV intra-operatively and every 6 hours for 48 hours, then 500 mg IM for additional 72 hours (N = 5) vs placebo (N = 7) | |

| Outcomes | Morbidity (temperature > 100.9°F twice, 6 hours apart after first 48 hours or other clinical signs of infection); not separated. For this review, the authors’ definition of morbidity has been classified as fever | |

| Notes | Part ofa larger randomized trial ofprophylactic antibiotics in gynecologic surgery; most patients (87%) were undergoing hysterectomy; only 12/300 patients enrolled underwent CS | |

| Class of antibiotic: first generation cephalosporin. | ||

| Subgroups: | ||

|

||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Item | Authors’ judgement | Description |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Unclear | “Randomized.” |

| No additional information. | ||

| Allocation concealment? | Yes | Randomized list ofplacebo or drug, kept in hospital pharmacy; code not broken until after patient classified as ‘morbid’ or ‘non-morbid’ |

| Blinding? | Yes | Described as “double-blind”. |

| All outcomes | Placebo-controlled. | |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? | Yes | No loss to follow up. |

| All outcomes | No participants excluded. | |

| ITT analysis. | ||

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear | Insufficient information to judge. |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear | No information was provided. |

| Overall low risk of bias? | Unclear | Insufficient information to judge. |

| Methods | RCT: 2 parallel groups. | |

| Unit of randomization: individual. | ||

| Participants | Dates of data collection: October 1977 to June 1980. | |