TO THE EDITOR:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is highly prevalent in the general population and has been associated with arrhythmias, hypertension, stroke, and heart failure (1). Identification of OSA in cardiovascular patients is especially important as untreated OSA may be accompanied by increased cardiovascular events, and this risk may be attenuated by treatment with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)(2). We sought to investigate how the rates of recognition and diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea compare to the actual prevalence of OSA in patients after myocardial infarction (MI).

This study comprised two parts: a chart review of consecutive patients presenting with acute MI, and a prospective evaluation of MI patients who were recruited to undergo polysomnography. These studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board. First, we reviewed the medical records of 798 consecutive patients who were hospitalized with a diagnosis of acute MI between January and September 2007. Electronic records, including admission and dismissal notes were searched for diagnosed or suspected sleep disordered breathing, and especially for mention of OSA during the MI hospitalization. In the event of several hospital admissions for the same patient, only the first admission was used in our analysis. We further prospectively studied 74 patients who were hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction between 2004 and 2008, and were recruited to undergo attended overnight polysomnography, which is the gold standard in the diagnosis of OSA (Compumedics Siesta Wireless Sleep Recorder, Oxford Instruments, UK). All polysomnographies were performed within 6 weeks of the MI hospitalization, and scored by standard criteria (1). OSA was defined as present when the apnea hypopnea index (AHI) was >5. The diagnosis of MI was based on standard guidelines, and was made by the attending physicians who were blinded to this study. Patients were approached during their MI hospitalization, and their participation was based on their consent and availability of the study personnel and equipment. There was no systematic selection for specific demographic or patient characteristics. A review of electronic and paper records of these patients was also performed in similar fashion to that of the first part of our study.

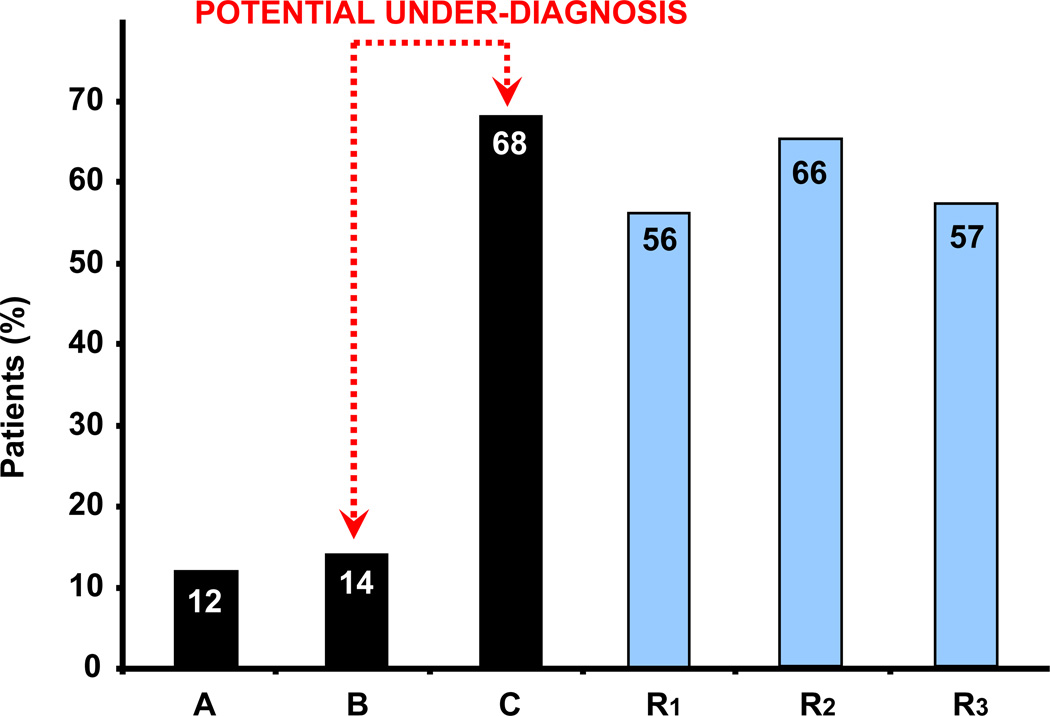

Between January and September 2007 there were 798 patients admitted to our institution with the diagnosis of acute MI. The mean age of this cohort was 69±14 years, and 512 (64%) were male. Diagnosed and suspected OSA was recorded in 97 (12%) patient records. The prospective cohort of 74 patients had a mean age of 62±13 years, and 46 (78%) were male. On review of their hospital records, 10 (14%) had documentation of diagnosed or suspected OSA. All of these patients underwent overnight polysomnography (PSG). For this group the mean AHI was 17±18 events/hour. OSA was present in 51 (69%), and severe OSA (AHI >15) in 30 (41%) patients.

The main finding of this study was the low rate of documented or suspected OSA in patients hospitalized for acute MI, contrasting with the high prevalence of OSA in those in whom we conducted prospective PSG studies. This suggests a lack of awareness and recognition of OSA during treatment of acute MI. A high prevalence of OSA in the unselected general population has been well documented (1). Our results suggest that only 12 percent of patients hospitalized with acute MI had documentation of diagnosed or suspected OSA. When prospectively evaluated by overnight PSG a subgroup of patients had a much higher actual prevalence of OSA (over two thirds had at least mild OSA) but even in these patients with proven sleep apnea the possibility of OSA was documented in only 14 percent of patients.

There are several limitations to our study. First, documentation in the medical record does not necessarily reflect the entire scope of medical evaluation; it is possible that in some patients OSA was suspected and they were verbally recommended to have an OSA evaluation which was not documented in the records, or this was left for a follow-up visit. Even so, it would be advantageous to arrange for screening for OSA during the hospitalization, just as we routinely initiate aspirin, beta-blocker, statin, and ACE inhibitor therapy before patient discharge.

Cardiovascular disease patients with untreated severe OSA are thought to have worse cardiovascular outcomes (2,3), which may be improved with CPAP. Randomized controlled trials testing this assumption are lacking. Demonstrated beneficial effects of CPAP could lead to significant practice and guidelines changes. An absence of such clinical trials may help explain the relatively low awareness of OSA as an important consideration in the patient with MI.

Figure 1.

A: Documented or suspected obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in patients with myocardial infarction (MI); B: Documented or suspected OSA in MI patients recruited for polysomnography; C: Prevalence of OSA in MI Patients recruited for polysomnography; R1-3: For comparison we show prevalence of OSA in studies of patients with acute coronary syndromes [1: BaHammam A., et al.(4); 2: Mehra R., et al.(5); 3: Yumino D., et al.(3)]

Acknowledgments

FUNDING SOURCES

This study was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants HL65176 and 1-UL1-RR024150, by a grant from the Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, and by a gift to the Mayo Foundation from the Respironics Foundation for Sleep and Respiratory Research. Dr. Sert Kuniyoshi is supported by American Heart Association grant 09-20069G. Dr. Sean Caples is supported by NIH grant HL 99534, Annenberg Foundation, ResMed, Ventus Medical, Restore Medical.

ABREVIATIONS

- AHI

Apnea-Hypopnea Index

- CPAP

Continuous Positive Airway Pressure

- MI

Myocardial Infarction

- OSA

Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- PSG

Overnight polysomnography

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTERES: Dr Virend Somers has served as a consultant for ResMed, Cardiac Concepts, and Boston Scientific, and as a PI or co-investigator on grants from Respironics Foundation and Sorin Inc. He is also involved in intellectual property development in sleep and cardiovascular disease with Mayo Health Solutions and their industry partners.

REFERENCES

- 1.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365:1046–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yumino D, Tsurumi Y, Takagi A, Suzuki K, Kasanuki H. Impact of obstructive sleep apnea on clinical and angiographic outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99:26–30. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.07.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.BaHammam A, Al-Mobeireek A, Al-Nozha M, Al-Tahan A, Binsaeed A. Behaviour and time-course of sleep disordered breathing in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:874–880. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2005.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehra R, Principe-Rodriguez K, Kirchner HL, Strohl KP. Sleep apnea in acute coronary syndrome: high prevalence but low impact on 6-month outcome. Sleep Med. 2006;7:521–528. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]