Abstract

Background

Health literacy (HL) is an established independent predictor of cardiovascular outcomes. Approximately 90 million Americans have limited HL and read at ≤ 5th grade-level. Therefore, we sought to determine the suitability and readability level of common cardiovascular patient education materials (PEM) related to heart failure and heart-healthy lifestyle.

Methods and Results

The suitability and readability of written PEMs were assessed using the suitability assessment of materials (SAM) and Fry readability formula. The SAM criteria are comprised of the following categories: message content, text appearance, visuals, and layout and design. We obtained a convenience sample of 18 English-written cardiovascular PEMs freely available from major health organizations. Two reviewers independently appraised the PEMs. Final suitability scores ranged from 12 to 87%. Readability levels ranged between 3rd and 15th grade-level; the average readability level was 8th grade. Ninety-four percent of the PEMs were rated either superior or adequate on text appearance, but ≥ 50% of the PEMs were rated inadequate on each of the other categories of the SAM criteria. Only two (11%) PEMs had the optimum suitability score of ≥ 70% and ≤ 5th grade readability level suitable for populations with limited HL.

Conclusions

Commonly available cardiovascular PEMs used by some major healthcare institutions are not suitable for the average American patient. The true prevalence of suboptimal PEMs needs to be determined as it potentially negatively impacts optimal healthcare delivery and outcomes.

Introduction

Health literacy is the ability to understand health information and to use that information to make good decisions about your health and health care.1 Given the uniqueness of health information and the sometimes peculiar and stressful circumstances under which it is delivered, it has the potential to overwhelm even individuals with advanced literacy skills. Health care consumers with poorer reading skills are more likely to experience difficulty with navigating the health care system and to be at risk of having undesirable outcomes. According to the Institute of Medicine more than 90 million adults in the United States have difficulty understanding and using health information.2 Limited health literacy (HL) has been shown to foster non-adherence to cardiovascular disease (CVD) treatment regimen resulting in suboptimal risk factor control (e.g., hypertension and hyperlipidemia) 3, 4 and increased adverse cardiovascular related health outcomes.5, 6, 7 There is an increasing awareness of the role of adequate health literacy in reducing health care costs and improving outcomes. In the past decades, several health disciplines have developed educational materials to aid the patient in the management of their health and healthcare. It is debatable if these educational materials have provided consumers with adequate health information and empowered them to become better custodians of their healthcare. Poor suitability (ease of understanding and acceptance) and readability (reading difficulty) level of cardiovascular patient education material (PEM) has been suggested as a barrier to improving the knowledge of the CVD patient.8 The aim of this study was to evaluate the suitability and readability of common cardiovascular PEMs with a focus on heart failure and heart healthy lifestyle. The novelty of this study lies in the fact that, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first documented evaluation of the utility of printed PEMs in heart failure arena.

Methods

Identification of Assessment Materials

We searched a variety of data sources for full-text manuscripts published between 1990 and 2009 including MEDLINE, Embase, and PsycINFO. The search terms included “health literacy,” “health education materials,” “patient education materials,” “suitability,” “readability,” and “assessment.” The reference listings of articles identified from the search were evaluated for additional publications. Publications from relevant governmental agencies and abstracts presented at major scientific meetings since January 2005 were also reviewed for relevance. The guidelines proposed by Doak et al.9 for suitability assessment of materials (SAM) were the most commonly cited in literature.

The SAM evaluates the appropriateness and presentation of printed adult health-related materials that were developed for use by individuals with limited literacy skills. The SAM criteria allow for standardized evaluation of health-related patient educational print materials and have been applied successfully in prior studies related to HL.10–13 Although the SAM was originally designed for use with printed education materials, it has been applied to audiovisual and audiotape materials as well.9 Furthermore, the validity and reliability of the SAM has been established in both pediatric and adult populations. In an evaluation of Pediatric dental patient education materials using the SAM method, a rater was trained by an experienced health literacy evaluator to establish validity, and then repeated assessment of materials by the trained rater was used to establish adequate inter-rater reliability.14 The reliability of the tool was further established in a study analyzing 31 patient information leaflets (PILs) for prostate cancer, where, after an independent analysis of each information leaflet, scores were compared to check the inter-rater reliability of SAM using weighted kappa coefficients. The study reported that most of the items had moderate or substantial levels of agreement indicating that the instrument was reliable.15

The majority of the materials for literacy assessment employ readability formulas designed for ranking PEMs with a resultant score or measure of grade-level reading difficulty. The prominent measures of readability documented in literature are the Flesch Reading Ease (FRE) formula,16 Simplified Measure of Goobledygook (SMOG) readability formula,17 Fog index,18 and the Fry Formula.19 The Fry readability formula is a readability metric for English texts which calculates the reading difficulty level by the average number of sentences and syllables per hundred words. The averages obtained are then plotted onto a graph and the reading level of the content or reading material is the point of intersection of the average number of sentences and the average number of syllables. The Fry readability graph is the only formula that reports the grade level of the reading material directly from the plotting of syllable and sentence counts on the graph. We elected to use Fry readability formula (or Fry readability graph)19 because it is one of the commonly used formulas to evaluate written health literature. In addition, it is relatively easy to conduct, has widespread acceptability and utilization in current health education literature.20 The Fry formula correlates highly with other readability formulas and has application for both pediatric and adult populations.21 The Fry Formula19 and Doak et al.9 guidelines were utilized for the suitability and readability assessment of the cardiovascular PEMs identified.

Collection and Assessment of Cardiovascular PEMs

We obtained a convenience sample of printed patient information related to heart failure and heart healthy lifestyle from major local cardiovascular clinics as well as information retrieved from Internet search. Google search engine was utilized to search the web with the key words "cardiovascular patient education materials." We utilized 18 consecutively identified free PEMs written in English pertaining to heart failure and heart healthy lifestyle. Information written in languages other than English and/or specifically for health care professionals was not included in the study. We also excluded information targeting pediatric population as well as information on topics other than heart failure and heart healthy lifestyle.

Suitability assessment

The cardiovascular PEMs were evaluated based on the SAM criteria (Table 1) guidelines proposed by Doak et al.9 For our analysis we derived a 26-item tool from the SAM instrument composed of the following four categories: message content, text appearance, visuals, and layout and design. For example, message content (e.g. “are readers told what they should get from the material and what they can do to improve their health?”), text appearance (e.g. “is the font no smaller than 12 to 14 points”), visuals (e.g. “do the visuals all help communicate messages in a literal manner?”; “Are the visuals culturally relevant and sensitive”?), layout and design (e.g. “ are the messages organized so they are easy to act on and recall”?). Two reviewers (CM and MK) independently appraised each PEM characteristic using a scoring scheme of 0 (inadequate), 1 (adequate), or 2 (superior). A total SAM score was calculated for each of the four categories of the SAM criteria by adding up the points earned by all characteristics in each category then divided by the total points attainable to arrive at a percentage score for each category. An overall final percentage score was derived as the weighted-average of the SAM scores from all four categories. All percentage scores were interpreted as inadequate (0–39%), adequate (40–69%), and superior (70–100%) based on recommendations of the SAM criteria.

Table 1.

SAM criteria utilized for appraisal of PEMs

| Category | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Message Content | |

| Does the material explain the purpose and benefits from the patient’s view? | |

| Is the content limited to a few essential main points that the majority of the target population will benefit from? | |

| Are behaviors and skills emphasized rather than just facts? | |

| Are readers provided with opportunities small successes? | |

| Are key points reviewed at the end of each section/page? | |

| Is the material sensitive to cultural differences? | |

| Is the new information placed in the context of the patients’ lives? | |

| Are readers told what they should get from the material and what can do to improve their health? | |

| Is the organization of the paragraphs and sentences conducive to easy reading? | |

| Are instructions broken into easy-to-read parts? | |

| Is the material interactive (encourage the patient to write, answer questions, ask questions, cut out forms, etc)? | |

| Text Appearance | |

| Is the font size no smaller than 12–14pt? | |

| Is easy-to-read font (no fancy script or lettering) used? | |

| Are bold and underline used instead of ALL CAPS and italics? | |

| Are colors used to promote easy reading? (Dark fonts on light backgrounds are best.) | |

| Is overall sharp contrast and large font used? | |

| Visuals | |

| Do the visuals all help communicate your messages in a literal manner (no abstract symbols)? | |

| Are the visuals culturally relevant and sensitive? | |

| Are the visuals easy for your readers to follow and understand? | |

| Are internal body parts or small objects shown in context and in a realistic manner? | |

| Are the visuals professional and appropriate for an adult audience? | |

| Are the visuals free of distracting details that take away from the main idea? | |

| Do all the graphics contribute to your message? | |

| Are examples given for any lists, charts, or diaries that readers are supposed to complete? | |

| Layout and Design | |

| Is the cover effectively designed? | |

| Are messages organized so they are easy to act on and recall? (Headings, sub-headings, etc.) | |

| Is there a lot of white space (no dense text)? | |

| Is the text easy for the eye to follow (Bullets, paragraph shape: 40–50 characters wide, text boxes)? |

SAM, suitability assessment of materials; PEM, patient education meterials

Readability assessment

The reading grade level for each material was assessed using the Fry reading grade level assessment tool. Conducting the Fry test on a cardiovascular PEM involved a sequence of steps: three samples of a 100-word passage were randomly selected, followed by a count of the number of sentences in all three 100-word passages (the fraction of the last sentence is estimated to the nearest 1/10th), and then a syllable count of all three 100-word passages. The average number of sentences and syllables derived from all three randomly chosen passages are then plotted on a Fry’s readability graph to determine the reading grade-level of the PEM. Two reviewers (CM and MK) independently performed the Fry’s test on all collected cardiovascular PEMs by using three separate excerpts from each material.

Analyses and Inter-Rater Agreement

Cohen’s weighted kappa (κ) coefficient22, 23 was used to determine the agreement between the results of suitability and readability analyses from the two independent reviewers (CM and MK). The Cohen’s κ statistic is reported on a graded scale between 0 and 1.0 with ≤ 0.20 (poor), 0.21–0.40 (fair), 0.41–0.60 (moderate), 0.61–0.80 (good), and 0.81–1.0 (perfect).15 Inter-rater agreement analyses were performed using the statistical program R.24 Descriptive and graphical analyses of study data was performed with GraphPad Prism version 5.0a for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software, San Diego CA, www.graphpad.com). We conducted a preliminary (pre-appraisal) evaluation of inter-rater agreement by applying the SAM criteria to 3 randomly selected cardiovascular PEMs in order to resolve any discrepancies in the interpretation of the component characteristics of the SAM criteria; and then, two investigators (CM and MK) independently appraised all collected cardiovascular PEMs. A different investigator (KT) performed all analyses of inter-rater agreement. The Cohen’s weighted κ coefficient between CM and MK for independent appraisal of all cardiovascular PEMs according to categories of the SAM criteria were as follows: for message content κ = 0.59 (95% CI= 0.49, 0.69); for text appearance κ = 0.66 (95% CI= 0.50, 0.82); for visuals κ = 0.68 (95% CI= 0.54, 0.81); and lastly for layout and design κ = 0.64 (95% CI= 0.47, 0.81). The overall weighted κ coefficient for suitability assessment was 0.66 (95% CI= 0.59, 0.73), indicating an overall good agreement between CM and MK. The two investigators had 100 percent agreement in their readability assessment.

Results

Fifteen of the 18 cardiovascular PEMs identified and evaluated were published within this decade. The origin, cardiovascular focus, target population, and source of the PEMs are delineated in Table 2. Sixteen of these education materials targeted the general population, while the remainder targeted African American and Latino populations, respectively. Four PEMs originated from Krames or Krames/Merck and were located at a major city hospital that caters to the indigent population, while other PEMs were from health advocacy groups (American Heart Association, Heart Failure Society, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute), and from healthcare center/organizations/corporation (University of North Carolina, MaineHealth, Ohio State University Medical Center, Practicing Physician Education in Geriatrics Project, and Center for Health Care Strategies).

Table 2.

Characteristics of PEMs evaluated

| PEMs | Origin/author | Type or focus of PEM |

Target population |

Publication year |

Date retrieved |

Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEM1 | Heart Failure Society | Heart Failure | General/Geriatric | 2001 | 6/2009 | http://www.abouthf.org/_downloads/heart_failure_brochure.pdf |

| PEM2 | MaineHealth | Heart Failure | General | 2002 | 6/2009 | http://www.mainehealth.org/workfiles/mh_media/Controlling_HF_with_Medicines.pdf |

| PEM3 | MaineHealth | Low Sodium Diet | General | 2002 | 6/2009 | http://www.mainehealth.org/workfiles/mh_media/Controlling_HF_with_Medicines.pdf |

| PEM4 | Ohio State | Heart Failure | General | 2004 | 6/2009 | http://medicalcenter.osu.edu/PatientEd/Materials/PDFDocs/dis-cond/cardio/condition/about-heartfailure.pdf |

| PEM5 | PPE* | Heart Failure | General | Unknown | 6/2009 | http://www.gericareonline.net/tools/eng/heartfailure/attachments/HF_Tool_6_IN.pdf |

| PEM6 | Krames | Heart Failure | General | 2006 | 5/2009 | Retrieved locally |

| PEM7 | Krames/Merck | Heart-Healthy Living | General | 2004 | 5/2009 | Retrieved locally |

| PEM8 | CHCS | Heart-Healthy Living | General | Unknown | 6/2009 | http://www.chcs.org/usr_doc/Healthy_Heart.pdf |

| PEM9 | CHCS | Blood Pressure | General | Unknown | 6/2009 | http://www.chcs.org/usr_doc/Blood_Pressure.pdf |

| PEM10 | MaineHealth | Healthy Lifestyle | General | 2002 | 6/2009 | http://www.mainehealth.org/workfiles/mh_media/Important_Ways_Take_Care_Self.pdf |

| PEM11 | NHLBI | Blood Pressure | African American | 2004 | 6/2009 | http://hp2010.nhlbihin.net/mission/partner/african_americans.pdf |

| PEM12 | NHLBI | Heart Disease | General | 2006 | 6/2009 | http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/other/your_guide/living_hd_fs.pdf |

| PEM13 | NHLBI | Blood Pressure | Latino | 2008 | 6/2009 | http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/other/latino/hbp/bloodpressure.pdf |

| PEM14 | NHLBI | Blood Pressure | General | 2003 | 6/2009 | http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/public/heart/hbp/hbp_low/hbp_low.pdf |

| PEM15 | AHA | Heart Disease/Stroke | General | 2007 | 6/2009 | http://www.americanheart.org/downloadable/heart/116861545709855-1041%20KnowTheFactsStats07_loRes.pdf |

| PEM16 | UNC | Heart Failure | General | 2003 | 6/2009 | http://www.nchealthliteracy.org/comm_aids/1%20Original%20Heart%20Failure%20Intervention.pdf |

| PEM17 | Krames/Merck | Blood Pressure | General | 2006 | 5/2009 | Retrieved locally |

| PEM18 | Krames/Merck | Low Sodium Diet | General | 2006 | 5/2009 | Retrieved locally |

CHCS, Center for Health Care Strategies; NHLBI, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute; AHA, American Heart Association; UNC, University of North Carolina; PEM, Patient education material

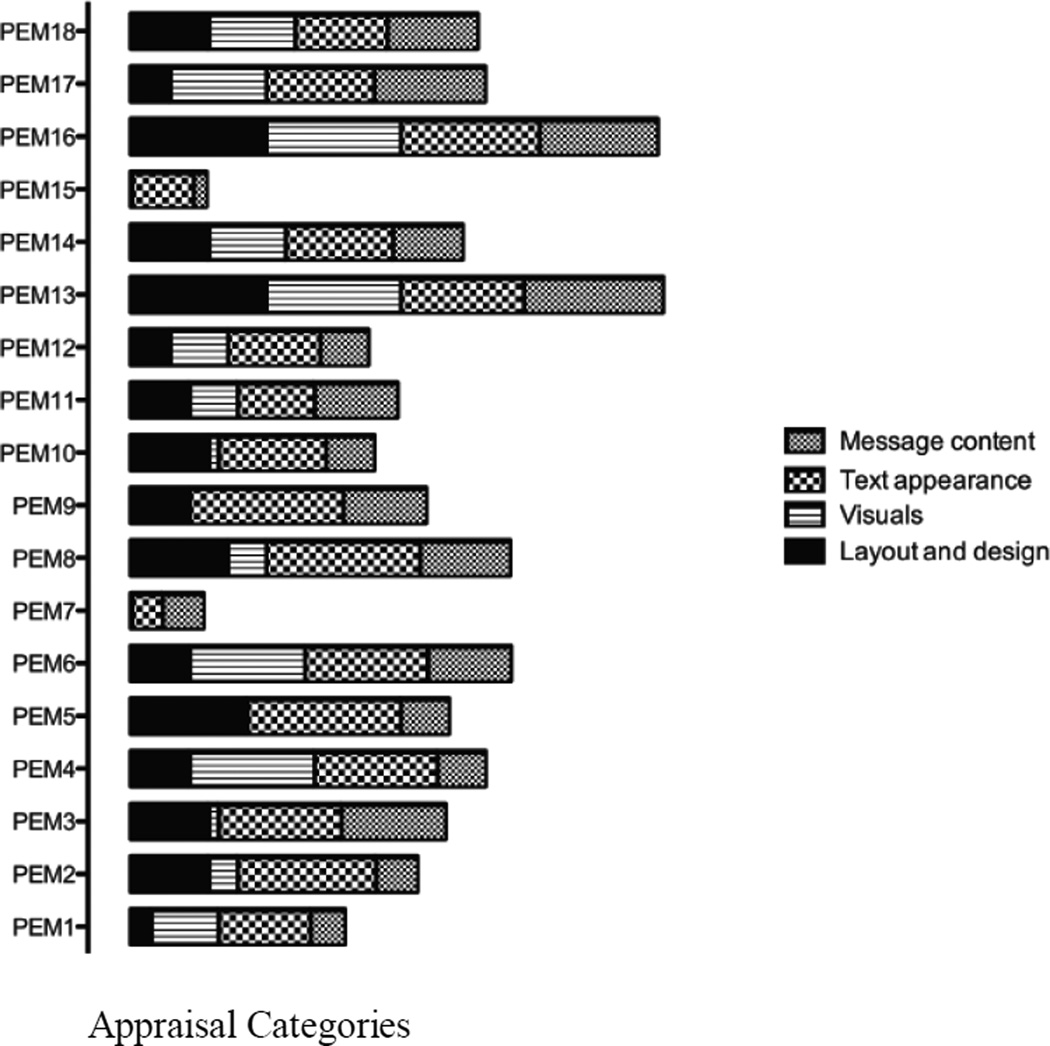

The following tables illustrate the detailed performance data of all PEMs by categories of the SAM criteria: Table 3a, appraisal by message content; Table 3b, appraisal by text appearance; Table 3c, appraisal by visuals; Table 3d, appraisal by layout and design. In the message content category, only 3 materials had superior rating while 9 PEMs were inadequate, and the remainder was rated adequate. On the text appearance criterion, 12 PEMs were superior, 5 were adequate and only one PEM was inadequate. Ten PEMs were inadequate by the visuals criterion and the remainder was evenly split between adequate and superior ratings. Nine PEMs had inadequate layout and design; only three had superior rating in this category. Overall, the analysis by categories of the SAM criteria suggests that the appearance criterion is more strictly observed because 94% of all PEMs were rated either superior or adequate in this category with a mean percentage score of 72%. On the contrary, in the other categories of the SAM criteria ≥ 50% of the PEMs were inadequate, with mean percentage scores of 37% for visuals, 47% for message content, and 43% for layout and design, respectively. Figure 1 illustrates the relative performance of all PEMs by appraisal categories. It displays the fact that most PEMs performed well on the text appearance criterion, that only PEMs 13, 15, and 16 excelled in terms of message content, that PEMs 4, 6, 13, and 16 were superior per visuals, and that PEM 5, 13, and 16 were superior in layout and design.

Table 3.

| a. Appraisal of 18 PEMs by message content criterion | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MESSAGE CONTENT | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Does the material explain the purpose and benefits from the patient’s view? | A | A | A | A | A | S | S | A | A | A | A | A | S | A | I | A | S | S |

| Is the content limited to a few essential main points that the majority of the target population will benefit from? | A | A | S | I | S | A | I | A | A | S | A | A | A | A | I | S | A | A |

| Are behaviors and skills emphasized rather than just facts? | I | I | S | A | I | A | A | S | S | A | A | A | S | A | I | S | A | A |

| Are readers provided with opportunities for small successes? | I | I | S | A | I | A | A | S | S | I | A | A | S | A | A | S | S | A |

| Are key points reviewed at the end of each section/page? | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | A | I | I | A | A | I |

| Is the material sensitive to cultural differences? | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | A | I | S | A | S | A | A | I | A | A |

| Is the new information placed in the context of the patients’ lives? | A | A | S | A | I | S | A | A | A | I | S | I | S | A | I | S | S | S |

| Are readers told what they should get from the material and what they can do to improve their health? | A | A | A | A | I | S | A | S | A | A | S | A | S | A | I | A | S | S |

| Is the organization of the paragraphs and sentences conducive to easy reading? | A | S | A | A | S | A | I | S | A | A | A | A | S | A | I | S | A | A |

| Are instructions broken into easy-to-read parts? | I | I | S | A | S | A | I | S | A | A | A | I | S | A | I | S | S | A |

| Is the material interactive? Does it encourage the patient to write, answer questions, ask questions, cut out forms, etc? | I | I | S | I | I | A | I | I | A | I | I | I | S | A | I | S | A | A |

| b. Appraisal of 18 PEMs by text appearance criterion | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEXT APPEARANCE | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Is the font size no smaller than 12–14pt? | I | S | S | A | S | I | I | S | S | S | I | I | A | I | I | S | A | I |

| Is easy-to-read font used? No fancy script or lettering? | S | S | S | S | S | S | A | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | A | S | S | S |

| Are bold and underline used instead of ALL CAPS and italics? | A | A | A | S | S | S | A | S | S | A | S | S | S | S | S | A | S | A |

| Are colors used to promote easy reading? (Dark fonts on light backgrounds are best.) | S | S | A | S | S | S | I | S | S | A | A | A | S | S | A | S | A | S |

| Is overall sharp contrast and large font used? | A | S | S | A | S | S | I | S | S | A | I | A | A | A | I | S | A | A |

| c. Appraisal of 18 PEMs by visuals criterion | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VISUALS | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Do the visuals all help communicate your messages in a literal manner? (No abstract symbols?) | A | A | I | S | I | S | I | I | I | I | I | I | S | A | I | S | A | A |

| Are the visuals culturally relevant and sensitive? | A | I | I | A | I | A | I | A | I | I | S | S | S | A | I | I | S | S |

| Are the visuals easy for your readers to follow and understand? Ex: if showing a sequence, are the steps numbered and labeled? | A | I | I | S | I | S | I | I | I | I | I | I | S | A | I | S | S | A |

| Are internal body parts or small objects shown in context and in a realistic manner? | I | I | I | S | I | A | I | I | I | I | I | I | S | I | I | S | A | I |

| Are the visuals professional and appropriate for an adult audience? | S | I | I | S | I | S | I | S | I | I | S | S | S | S | I | S | A | S |

| Are the visuals free of distracting details that take away from the main idea? | S | S | A | S | I | S | I | A | I | A | A | S | S | S | I | S | A | S |

| Do all the graphics contribute to your message? | I | I | I | S | I | S | I | I | I | I | I | I | S | A | I | S | S | A |

| Are examples given for any lists, charts, or diaries that readers are supposed to complete? | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | I | S | I | I |

| d. Appraisal of 18 PEMs by layout and design criterion | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAYOUT AND DESIGN | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

| Is the cover effectively designed? | I | I | I | I | I | A | I | I | I | I | A | A | A | A | I | A | I | A |

| Are messages organized so they are easy to act on and recall? (headings, sub-headings, “chunking,” etc.) | I | S | S | A | S | A | I | S | S | A | A | I | S | A | I | S | A | A |

| Is there a lot of white space? No dense text? | I | A | A | A | S | I | I | A | I | A | I | I | S | A | I | S | I | A |

| Is the text easy for the eye to follow? (bullets, paragraph shape (40–50 characters wide is best), text boxes, etc.) | A | A | A | A | S | A | I | S | A | S | A | A | S | A | I | S | A | A |

I, Inadequate; A, Adequate; S, Superior; PEM, Patient education material

I, Inadequate; A, Adequate; S, Superior; PEM, Patient education material

I, Inadequate; A, Adequate; S, Superior; PEM, Patient education material

I, Inadequate; A, Adequate; S, Superior; PEM, Patient education material

Figure 1. Relative performance of PEMs by appraisal categories.

This stacked bar chart illustrates the relative performance of all PEMs by appraisal categories. It demonstrates that most PEMs performed well on the text appearance criterion. However, only PEMs 13, 15, and 16 excelled per message content, PEMs 4, 6, 13, and 16 were superior per visuals, and PEM 5, 13, and 16 were superior per layout and design; thus PEMs 13, 16 performed consistently well on all appraisal categories.

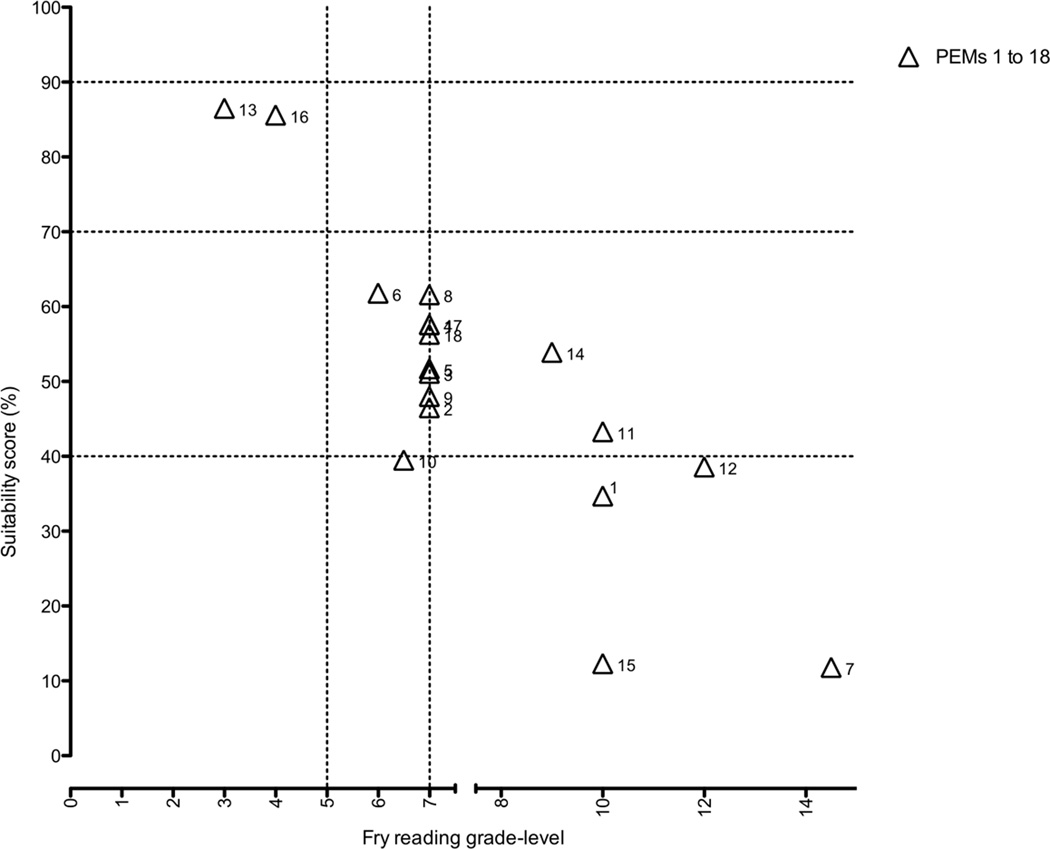

Final suitability scores ranged from 12 to 87% and mean ≈ 50%. Based on the ranking of the final percentage scores, only 2 (11%) of the 18 PEMs had superior (>70%) suitability scores. Of the remaining PEMs, 11 (61%) were rated average and 5 (28%) as inadequate. The readability levels of all the PEMs ranged between 3rd and 15th grade-level; the average readability level was 8th grade-level. The two printed patient information materials (PEMs 13 and 16) with superior suitability had 3rd and 4th grade readability levels respectively. On the contrary, eight of the 11 PEMs rated as adequate had 7th grade readability level; the readability levels in this group ranged from 6–10th grade. One of the PEMs that rated as inadequate had a 6–7th grade readability level while the remainder had ≥10th grade readability levels. Figure 2 illustrates the combined performance of all PEMs according to suitability and readability levels. Only two PEMs had the optimum suitability score of ≥ 70% and ≤ 5h grade readability level. Seven PEMs were at the 7th grade level mark and within the adequate suitability zone.

Figure 2. Readability versus suitability plot of PEMs.

A graphical representation of the combined suitability and readability performance of all PEMs. Only two PEMs had the optimum suitability score of ≥ 70% and the ≤ 5h grade readability level that characterizes majority of the ≈ 90 million Americans with limited health literacy. Seven PEMs were at the 7th grade level mark and within the adequate suitability zone.

PEM, patient education materials

SAM, suitablity assessment of materials

Discussion

This evaluation of the suitability and readability of a convenience sample of English-written cardiovascular PEMs employed by some major healthcare institutions, demonstrates a broad range in suitability scores (12 to 87 %) and readability levels (3rd and 15th grade). The average readability level was ≈ 8th grade. Although the majority of the PEMs were rated either superior or adequate on text appearance, more than half of all the PEMs were rated inadequate on each of the other categories of the SAM criteria, notably visuals, message content, and layout and design. Only two PEMs had the optimum suitability score (≥ 70%) and readability level (≤ 5th grade) suitable for populations with limited HL. Both of these materials (PEMs 13 and 16) appear to have been written with vulnerable populations in mind. PEM 13 was written for a low-literacy Latino community while PEM16 targeted a low-literacy heart failure population in North Carolina.

The ideal performance of PEMs 13 and 16 indicates that it is possible to develop suitable educational materials for patients with limited HL. Furthermore, it suggests that the tools for creating suitable PEMs are available to those interested in using them. However, the fact that of all 18 PEMs retrieved from some major health organizations, including leading government sources, only two PEMs had ideal suitability and readability is a cause for concern. In a recent evaluation of diabetes and cardiovascular disease PEMs developed by the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association for low-health literacy populations, the PEMs consistently met few criteria for usability by patients with low literacy.25 That report mirrors the results of the current study, which suggests that suboptimal PEMs are potentially pervasive, and thus requires further investigation and possible intervention.

Since the average American reads at an 8th grade reading level, Doak et al9 recommend that educational materials should not exceed the 6th grade reading level.26 However, in our evaluation, we elected to use a 5th grade reading level as the cut off for optimal readability. This is because the average Medicare or Medicaid recipient reads at a 5th grade-level and an average person from a vulnerable population may read below the 5th grade-level.26, 27 It is important to note that despite the disproportionate limited HL amongst ethnic and minority groups, there is also a significant population of Whites with limited HL.28 Overall, race and ethnicity are not the only delineators of the population vulnerable to limited HL; elderly Americans, chronic disease patients, recent immigrants, and people with low socioeconomic status are similarly afflicted by limited HL28 and disproportionate CVD burden and adverse outcome.29 The results of a 2003 National Assessment of Adult HL survey indicates that 87 million (36%) of the 242 million adults have limited HL.28 Thus limited HL pervades our society with attendant costs to the healthcare system and economy,30, 31 which underscores the need to investigate the actual prevalence of poor PEMs, their potential impact on cardiovascular care and outcome, and approaches to improve PEMs in order to facilitate care delivery.

Practice and Policy Implications

The findings from this study have important implications for clinical practice: healthcare professionals charged with the responsibility of developing PEMs should become aware of the potentially significant prevalence of suboptimal PEMs. This knowledge should motivate them to design PEMs that patients with low literacy levels can understand and act on. For instance, within the cardiovascular arena where risk assessment or prediction underpins management strategy, it may be worthwhile to explore how HL status can be incorporated into new or existing algorithms for risk prediction in order to further refine our risk assessment or justification for aggressive social and medical intervention, while creating a continued awareness on the potential impact of limited HL on cardiovascular and health outcomes in general. This action can be viewed as an extension of the philosophy of personalized medicine with a focus on HL status as an easily measurable and addressable determinant of prospective cardiovascular disease phenotype. Educational materials designed to activate patients toward healthy behavior should be culturally competent and relevant. Each healthcare facility should set up a feedback mechanism that allows them to evaluate patient’s use and comprehension of the materials. This effort will undoubtedly improve patients’ informed participation in their healthcare management and hopefully lead to better adherence to treatment regimen, lifestyle changes, and improved cardiovascular outcomes.

Given that HL has been named a Joint Commission Patient Safety Goal, governmental agencies should lead this effort by carefully designing materials using low literacy principles (shortening words, simplifying sentence structure, culturally appropriate artwork, large clear font etc.) tailored to no higher than a 5th grade reading level. Preliminary educational materials should be made available to patients soliciting their honest critique and feedback. The materials should be refined using input from the target population. The indisputable benefit of primary prevention should compel insurance payers to compensate clinicians who address HL or HL-related problems. As a matter of fact, the report card on the performance or rating of healthcare organizations could reflect objective efforts targeted at effective patient education and communication strategies across varying HL strata. We have delineated our perspective on possible approaches to PEMs improvement on Table 4. Finally, healthcare consumers should be encouraged to be proactive in advocating for their health through utilization of the materials and providing necessary feedback whenever possible.

Table 4.

Possible approaches to improving patient education materials

|

PEM, Patient education material; HL, Health literacy

Limitations

A major limitation of our study rests on lack of outcomes data on the impact of suboptimal PEMs. In addition, no detailed patient-based evaluation was performed to determine the patients perspective on suitability of all PEMs evaluated. These issues provide insight on future research directions. Another major limitation is the number of PEMs evaluated in this study, which cannot be representative of the number of healthcare institutions, and therefore PEMs, across the country. However, the convenience sample of PEMs evaluated was identified by consecutive selection of top search results for free English-written PEMs related to heart failure and heart healthy lifestyle. Though not a representative sample, the fact that these suboptimal PEMs were developed by leading health organizations should be impetus for more comprehensive studies to evaluate the prevalence across healthcare institutions and practice groups, and the potential impact of suboptimal PEMs on cardiovascular care and outcomes. Lastly, even when the PEM is perfect, health care consumers sometimes neglect to read the educational materials or may elect not to adhere to the teachings provided in the PEM.

Summary

The results of this study show that majority of the PEMs we evaluated had suboptimal suitability and readability levels. This raises the question about the actual prevalence of suboptimal cardiovascular PEMs across health institutions and practice organizations in the country. Current changes in the healthcare delivery system has imposed a limitation on the contact time between patient and provider as well as decreased length of hospital stay. This ongoing transformation has undoubtedly increased patients’ responsibility for self-care thereby emphasizing the need for quality teaching and instruction materials.

What’s New?

Patient educational materials used by some major healthcare institutions have suboptimal suitability and readability. Thus, they may not be appropriate for populations with limited health literacy.

The use of poorly prepared educational materials is likely prevalent in the facilities that manage patients with cardiovascular diseases.

Our findings highlight the need for further research to determine the actual prevalence of suboptimal patient education materials across healthcare institutions and practice organizations and its potential impact on cardiovascular care and outcomes.

Acknowledgments

None

Funding Sources

This work was supported in part by a gift from The Ingram Foundation to the cardiovascular division and Vanderbilt Heart and Vascular Institute, Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Award of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (U.S.), Vanderbilt Clinical and Translational Scholars Award (U.S.), Wheaton Fellowship Award (M.K.), and Lisa M Jacobson Chair (D.S.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

GAM is employed by PepsiCo, although no conflicts of interest have been identified in his role.

References

- 1.Institute of medicine of the national academies. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilson JF. The crucial link between literacy and health. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:875–878. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ. The seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA. 2003;289:2560–2572. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Insull W. The problem of compliance to cholesterol altering therapy. J Intern Med. 1997;241:317–325. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1997.112133000.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Influence of adherence to treatment and response of cholesterol on mortality in the coronary drug project. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:1038–1041. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198010303031804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berkman ND, Dewalt DA, Pignone MP, Sheridan SL, Lohr KN, Lux L, Sutton SF, Swinson T, Bonito AJ. Literacy and health outcomes. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2004:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cho YI, Lee SY, Arozullah AM, Crittenden KS. Effects of health literacy on health status and health service utilization amongst the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66:1809–1816. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Safeer RS, Cooke CE, Keenan J. The impact of health literacy on cardiovascular disease. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2006;2:457–464. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.2006.2.4.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doak CC, Doak LG, Root JH. Teaching patients with low literacy skills. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Company; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eames S, McKenna K, Worrall L, Read S. The suitability of written education materials for stroke survivors and their carers. Top Stroke Rehabil. 2003;10:70–83. doi: 10.1310/KQ70-P8UD-QKYT-DMG4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann T, McKenna K. Analysis of stroke patients' and carers' reading ability and the content and design of written materials: Recommendations for improving written stroke information. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60:286–293. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rees CE, Ford JE, Sheard CE. Patient information leaflets for prostate cancer: Which leaflets should healthcare professionals recommend? Patient Educ Couns. 2003;49:263–272. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(02)00188-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weintraub D, Maliski SL, Fink A, Choe S, Litwin MS. Suitability of prostate cancer education materials: Applying a standardized assessment tool to currently available materials. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;55:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang E, Fields HW, Cornett S, Beck FM. An evaluation of pediatric dental patient education materials using contemporary health literacy measures. Pediatr Dent. 2005;27:409–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Flesch R. A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1948;32:2211–2223. doi: 10.1037/h0057532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McLaughlin GH. Smog grading: A new readability formula. Journal of Reading. 1969;12:639–646. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunning R. The technique of clear writing. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fry R. Fry's readability graph: Clarifications, validity, and extension to level 17. Journal of Reading. 1977;21:241–252. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merritt SL, Gates MA, Skiba K. Readability levels of selected hypercholesterolemia patient education literature. Heart Lung. 1993;22:415–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meade CD, Smith CF. Readability formulas: Cautions and criteria. Patient Educ Couns. 1991;17:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen JA. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20:37–46. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull. 1968;70:213–220. doi: 10.1037/h0026256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.R development core team. R foundation for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: 2010. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. ISBN 3-900051-07-0, http://www.R-project.Org. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill-Briggs F, Smith AS. Evaluation of diabetes and cardiovascular disease print patient education materials for use with low-health literate populations. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:667–671. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirsch I, Jungeblut A, Jenkins L, Kolstad A. Adult literacy in America: A first look at the findings of the national adult literacy survey. 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jackson RH, Davis TC, Bairnsfather LE, George RB, Crouch MA, Gault H. Patient reading ability: An overlooked problem in health care. South Med J. 1991;84:1172–1175. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199110000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Center for Education Statistics. The health literacy of america's adults: Results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mensah GA, Mokdad AH, Ford ES, Greenlund KJ, Croft JB. State of disparities in cardiovascular health in the united states. Circulation. 2005;111:1233–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000158136.76824.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedland R. New estimates of the high costs of inadequate health literacy; Proceedings of Pfizer conference "promoting health literacy: A call to action."; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eichler K, Wieser S, Brugger U. The costs of limited health literacy: A systematic review. Int J Public Health. 2009;54:313–324. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-0058-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]