Abstract

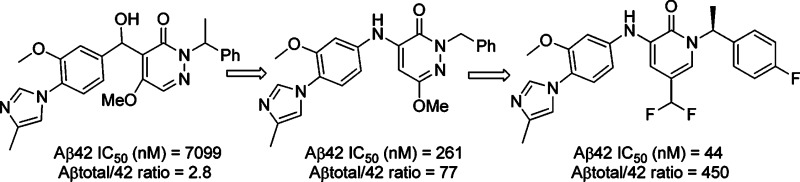

A series of novel pyridazone and pyridone compounds as γ-secretase modulators were discovered. Starting from the initial lead, structure−activity relationship studies were carried out in which an internal hydrogen bond was introduced to conformationally fix the side chain, and compounds with improved in vitro Aβ42 inhibition activity and good Aβtotal/Aβ42 selectivity were quickly discovered. Compound 35 displayed very good in vitro activity and excellent selectivity with good in vivo efficacy in both CRND8 mouse and nontransgenic rat models. This compound displayed a good overall profile in terms of rat pharmacokinetics and ancillary profile. No abnormal behavior and side effects were observed in all of the studies.

Keywords: Pyridazone, pyridone, γ-secretase, modulator, Alzheimer's disease

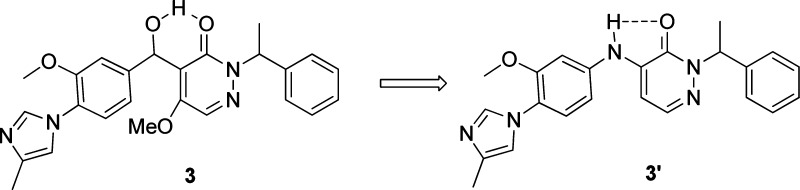

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is an age-related neurodegenerative disorder (cognitive impairment, loss of memory, and language ability) that affects millions of older people in the United States.1,2 To date, there is still an unmet medical need for treatments of this disease, and research laboratories across academia and pharmaceutical companies are working aggressively to identify new therapeutic agents to cure or, at a minimum, retard progression of it. Although the cause of the AD is still debated,3−5 short Aβ peptides generated from the cleavage of Aβ peptides in the brain are believed to be one of the main contributors to the disease.6 γ-Secretase is a biochemically complex aspartyl protease enzyme, which, when coupled with β-secretase, can process amyloid precursor protein (APP) to produce Aβ peptides. Soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ peptides have been proposed as the neurotoxic agents. Inhibition of these enzymes would reduce production of Aβ, which should slow or halt the progression of cell death and cognitive decline. γ-Secretase cleavage of CTFβ leads to Aβ peptides of 37−42 amino acids of which Aβ42, the more hydrophobic form, is most toxic.7 γ-Secretase modulators shift the γ-secretase cleavage toward short peptides by selectively inhibiting Aβ42 without blocking overall γ-secretase function (Aβtotal). Modulation as opposed to outright inhibition should offer a potentially improved side effect profile—for example, versus notch processing.8−10 Because of this advantage, research in this field has heated up in recent years in the pharmaceutical industry. There are two major classes of γ-secretase modulators in clinical trials. One is structure-related to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory acids (NSAIDs),11,12 such as 1 from Myriad. The other is the non-NSAIDs class, such as 2 from Eisai. In our effort in the AD area, we have recently identified an initial γ-secretase modulator compound (3) that was discovered based on the idea of mimicking the double bond in compound 2 with intramolecular hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl and the pyridazone carbonyl groups. Herein, we report our structure−activity relationship (SAR) effort based on this lead to quickly identify compounds with good in vitro and in vivo activity with good Aβtotal/Aβ42 selectivity.

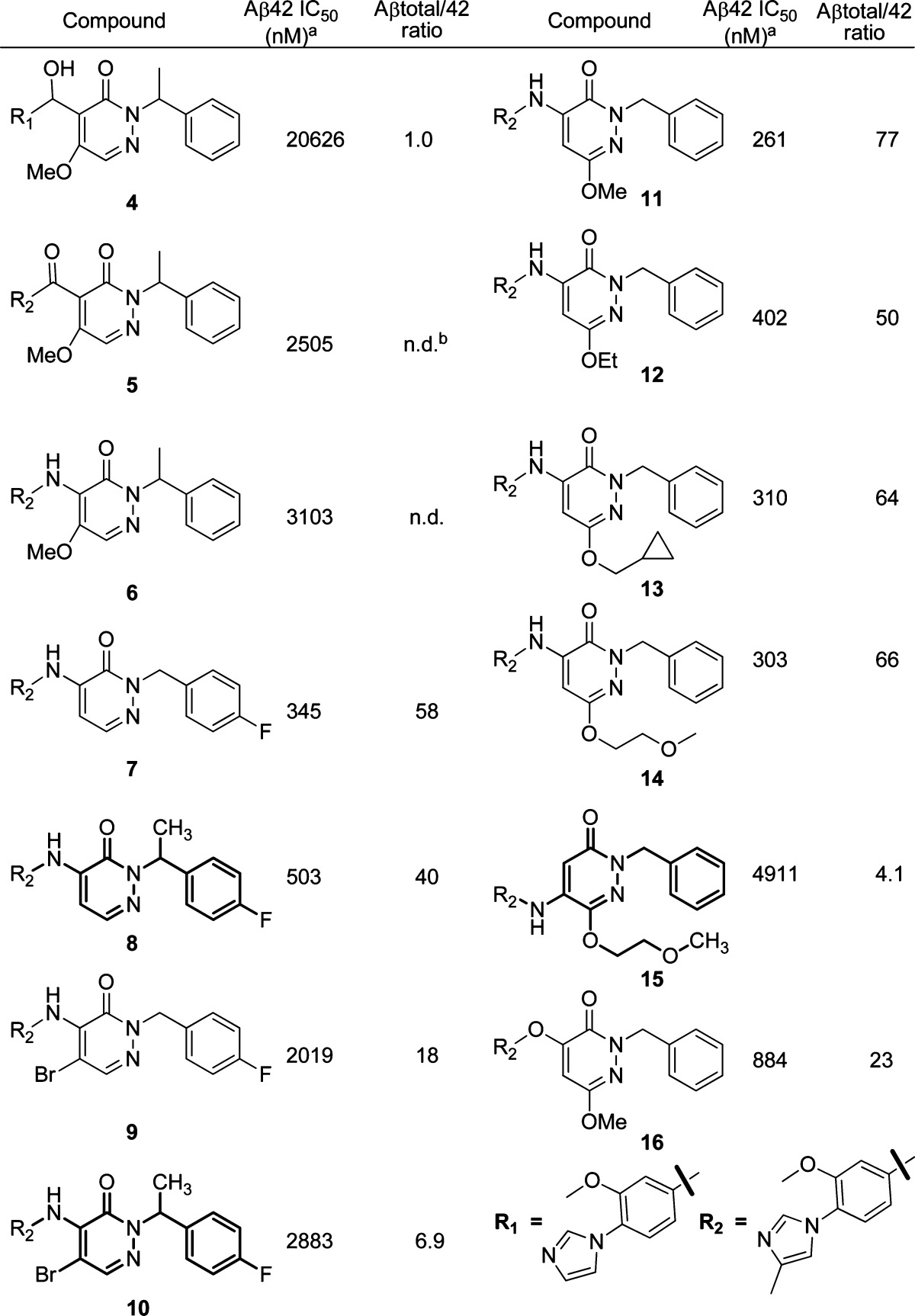

Initial SARs focusing on the pyridazone core and modification of the left-hand side imidazole suggested that the methyl group was important for in vitro activity. When there was no methyl substitution on the imidazole, the Aβ42 inhibition decreased by at least 2-fold (4, Table 1). We then turned our attention to the central linker modification. When the hydroxyl methyl group was converted to a carbonyl group, the activity increased by about 3-fold (5). Hypothesizing that an NH group as the linker might hydrogen bond with the pyridazone carbonyl group and lock the side chain in the same conformation as the double bond in the lead structure 2 (Figure 1, 3 to 3′), we prepared compound 6, which showed improved activity. Although the desired H-bond effect was not observed, we thought that the C5 methoxy group might diminish the effect because of steric repulsion. Further improvement of the activity was indeed achieved by removing the C5 methoxy group, and the IC50 value had a dramatic improvement to 345 nM (7), a 10-fold increase. This result suggests that the bulkyl group at C5 is not amenable to improving the in vitro activity, and intramolecular hydrogen bonding may indeed have a beneficial effect. This observation was further confirmed with the preparation of 9 and 10. A 6-fold loss of activity was observed when the bromine atom was introduced at C5. When the methyl group at the right-hand benzylic position (N2) was installed, the in vitro activity did not change significantly (8). To further improve the activity, we next turned our attention to modification of the C6 position. As summarized in Table 1, introduction of alkyl ethers at C6 was tolerated and gave reasonably good in vitro activity (11−13). Bulky substituents did not affect the activity too much and gave comparable Aβ42 inhibition and Aβtotal/42 selectivity (14). This suggests that there is space available for further modification at this position. C4 substitution with an amine linker proved to be important for in vitro activity. When the biaryl aniline was moved from the C4 to the C5 position, we saw more than a 10-fold decrease of activity (15). When an oxygen linker was introduced (16), the activity was 4-fold less potent as compared to its amino analogue (11).

Table 1. SAR Studies of the Pyridazone Series.

|

Each IC50 value is an average of at least two determinations.

n.d. = not determined.

Figure 1.

Employing intramolecular hydrogen bonding to lock the confirmation.

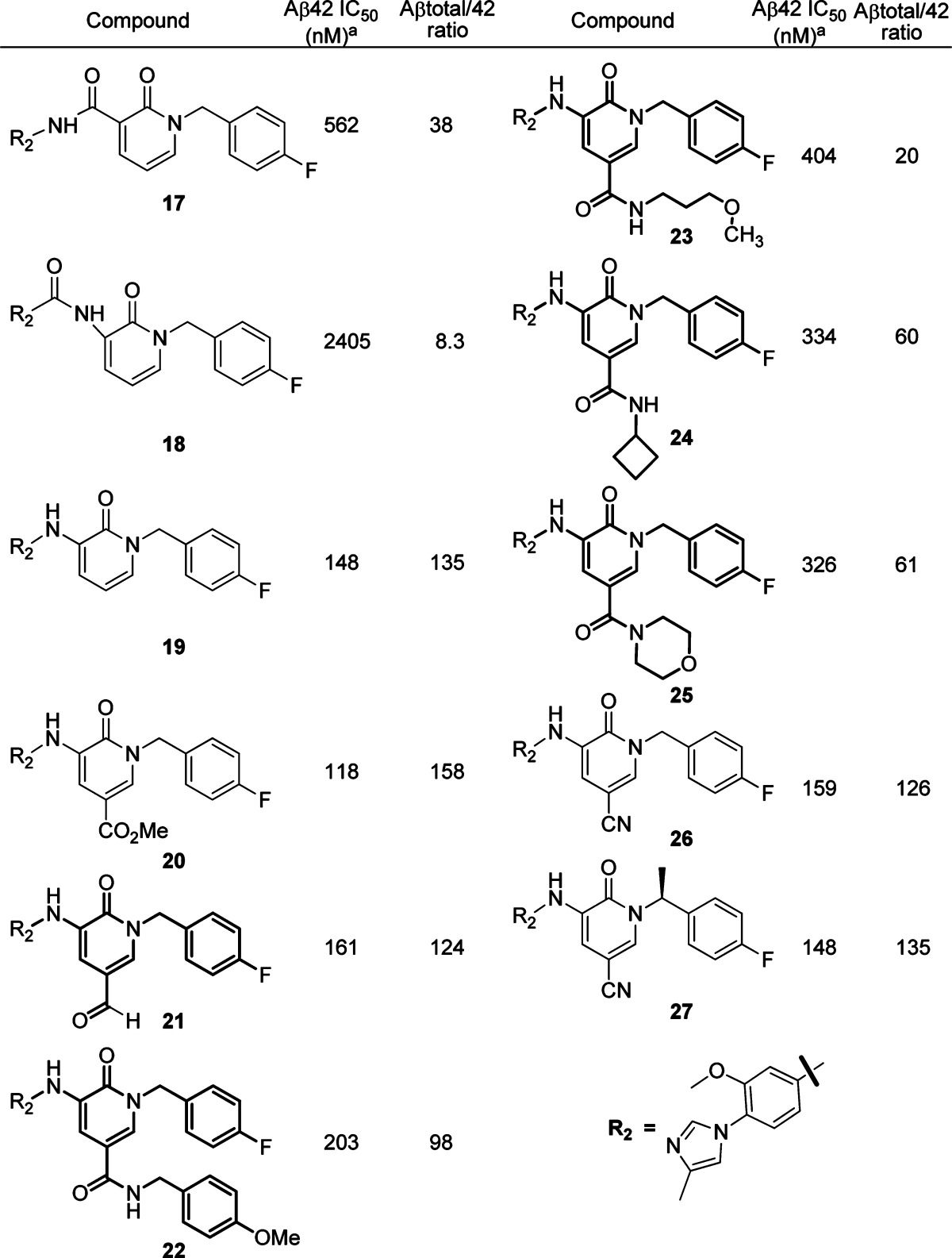

To further improve the in vitro activity, we decided to turn our attention to core modifications and began by adjusting the electron density of the core. We quickly identified that the pyridone core was a suitable substitution of the pyridazone core. We first introduced the amide linker (17 and 18, Table 2) in this series. Compound 17 showed better activity than 18, which had a reversed amide linker, but both were not as good as the pyridazone analogues. On the other hand, when the amino group was used as the linker, compound 19 displayed obviously improved in vitro activity and selectivity. We then decided to focus on modification of the C5 position with the amino group as the linker. Ester (20) and aldehyde (21) groups were tolerable at this position and gave good Aβ42 inhibition and Aβtotal/42 selectivity. When a series of amide groups were introduced (22−25), only moderate in vitro activity was observed; an aromatic ring (22) and alkyl group (23) did not change the IC50 value significantly. In comparison, when a smaller group such as a cyano group was introduced, compound 26 showed improved activity and selectivity even though it had similar potency and selectivity as the unsubstituted compound 19. A methyl group at the right-hand side benzylic position (N1) again did not affect the activity too much, and compound 27 showed similar in vitro activity to 26. However, the methyl group did have some impact on the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile of these compounds. The rat oral PK13 at 10 mpk (0−6 h) showed compound 27 had a better brain concentration (917.3 ng/g) at the 6 h time point than compound 26 (391.3 ng/g), which is desirable in the current project.

Table 2. Initial SAR Studies of the Pyridone Series.

|

Each IC50 value is an average of at least two determinations.

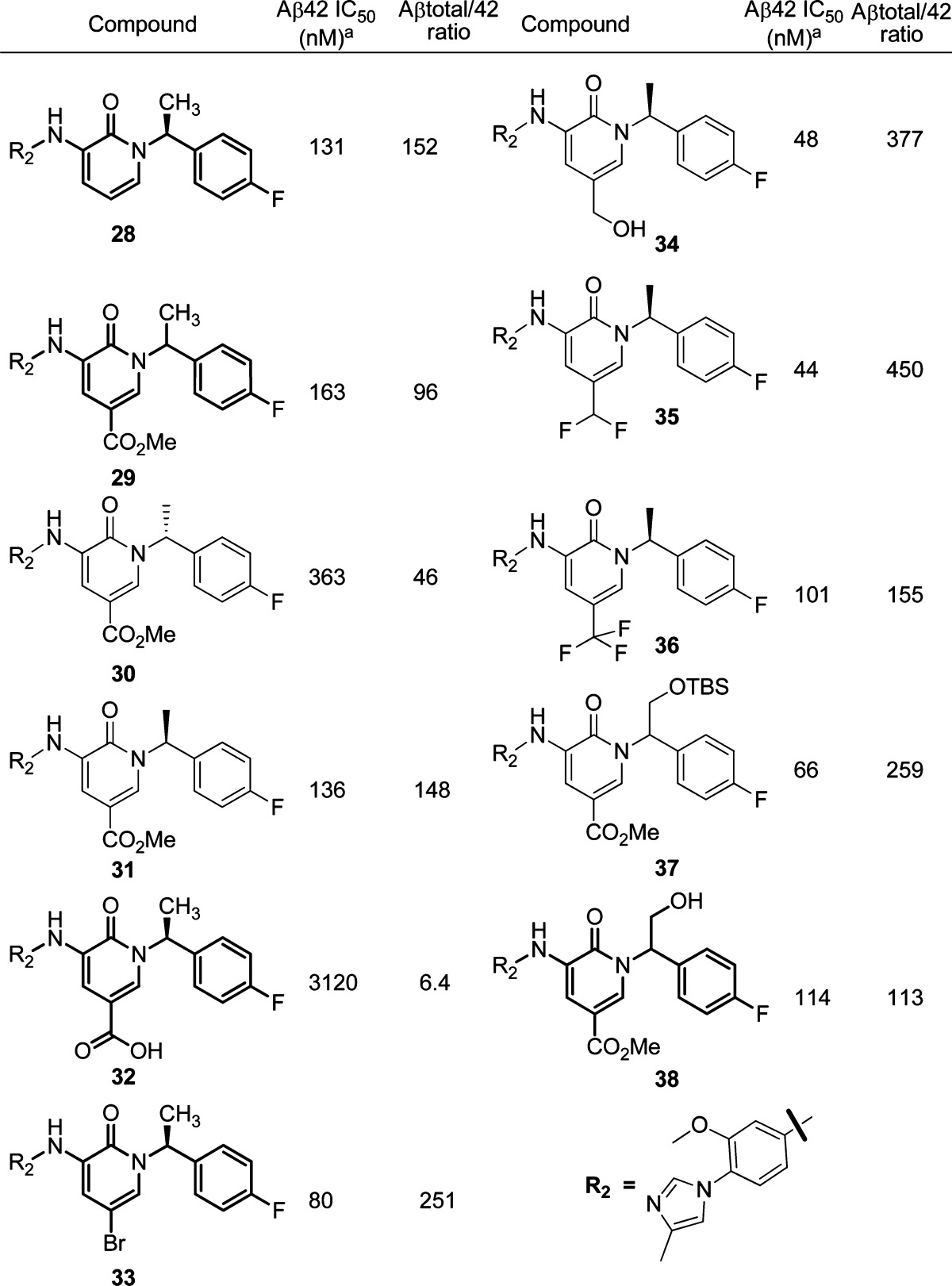

Because of the improved PK properties provided by the methyl group, we next focused our SAR efforts on modification of the C5 position with the α-methylbenzyl group installed at the right side N1 position in the hope to identify compounds with a good overall profile (Table 3). When there was no substitution at C5, compound 28 retained good in vitro activity and selectivity. The configuration of the substituent on N1 had a clear impact on activity. Racemic compound 29 had an IC50 value of 163 nM. Its enantiomers, however, displayed different activity. The R isomer (30) was 3-fold less active than the S isomer (31). Thus, our further SAR effort was focused on the compounds with the S configuration. A carboxylic acid group at the C5 position (32) was not a good choice in terms of improving the Aβ42 inhibition. Smaller electron-withdrawing groups seemed to improve activity. With the introduction of a bromine atom, the compound showed much improved Aβ42 IC50 value (33, 60 nM) and excellent selectivity over Aβtotal (251 fold). A hydroxy methyl group was tolerated and further improved the in vitro activity (34, 48 nM). When a difluoromethyl group was introduced (35), further improvement in selectively was observed. A stronger electron-withdrawing group such as the trifluoromethyl group seemed not very helpful at improving the activity (36). At this point, we wanted to find out whether the C5 and N1 substitutions had a synergistic effect on the in vitro potency. We therefore introduced polar groups on the methyl side chain at the N1 position. Even with a bulky TBDMS group at the right-hand side, racemic compound 37 showed 3-fold better activity than compound 29. This suggests that a large cavity may be available at the N1 position for further SAR modification. Interestingly, the more polar, and smaller, hydroxy methyl benzyl group at the N1 position was tolerated, and compound 38 had an Aβ42 IC50 value at 114 nM as a racemic mixture.

Table 3. SAR Studies of the Pyridone Series Focusing on the C5 Modification.

|

Each IC50 value is an average of at least two determinations.

As summarized in Table 3, compound 35 showed one of the best in vitro profiles in terms of enzyme activity and Aβ42 selectivity over Aβtotal. Therefore, it was further profiled in in vivo studies. This compound showed very good in vivo efficacy in a CRND8 mouse model, giving over 85% reduction of Aβ42 in plasma at 30 mpk with little effect on the Aβtotal. In the nontransgenic rat in vivo model,14 this compound displayed a 40% reduction of Aβ42 in the CSF at 100 mpk and a 26% reduction of Aβ42 in brain, while the Aβtotal only had a 7% reduction in the CSF. Compound 35 had good rat PK with an AUC1−6 h of 7.5 μM.h at 10 mpk and favorable brain concentration (347.3 ng/g) at the 6 h time point. No abnormal behavior or side effects were observed in those studies.

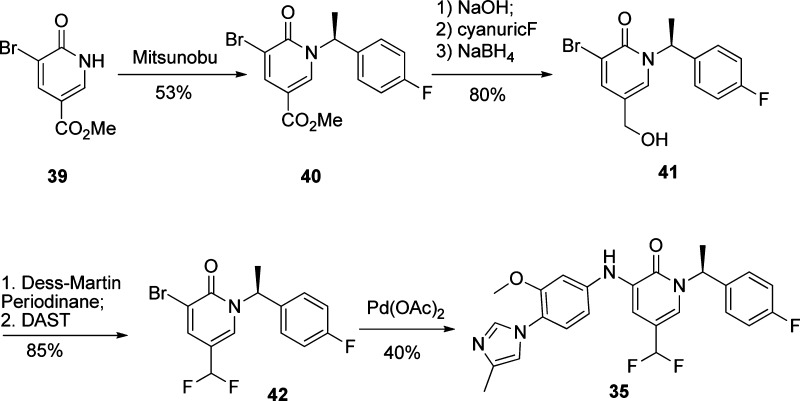

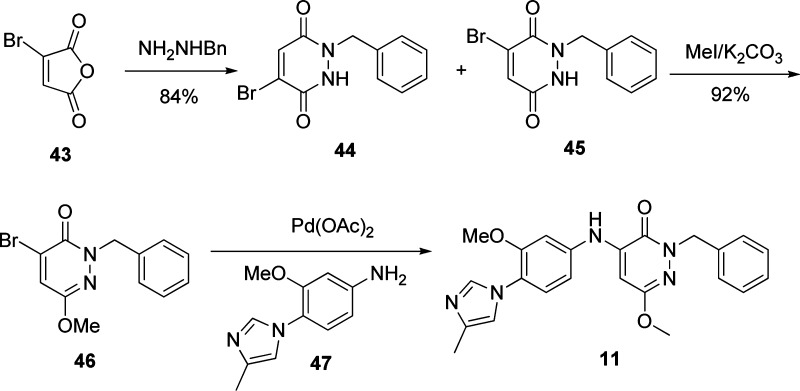

To demonstrate the synthesis of the pyridone analogues, the synthetic route to compound 35 is illustrated in Scheme 1. Starting from commercially available compound 39, a Mitsunobu reaction with (R)-1-hydroxy-1-(4-fluorophenyl)ethane gave enantiomerically pure 40. The ester group was converted to alcohol 41 in three steps15 since direct reduction with LiAlH4 resulted in a complex mixture. Compound 41 was converted to difluoro compound 42 in two steps via Dess−Martin oxidation and fluorination. A final coupling reaction using Pd(OAc)2 gave the desired product in moderate yield. Other pyridone compounds were prepared in a similar fashion. The synthesis of pyridazone compounds was straightforward and is shown in Scheme 2. Bromides 44 and 45 were obtained from compound 43 by treatment with NH2NHBn. Methylation of compound 45 furnished 46, which was coupled with aniline 47 using a catalytic amount of Pd(OAc)2 to give the final product 11.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Pyridone Analogue 35.

Scheme 2. Synthesis of Pyridazone Analogues.

In summary, we have indentified a series of novel pyridazone and pyridone compounds as γ-secretase modulators. Starting from the initial lead, we have carried out SAR studies employing a strategy that utilized an internal hydrogen bond to lock the conformation of the side chain present in the lead structure. The new analogues displayed an improved in vitro Aβ42 activity and good Aβtotal/Aβ42 selectivity. Compound 35 displayed very good in vitro activity and excellent selectivity with good in vivo efficacy in both the CRND8 mouse and the nontransgenic rat models. This compound had a good overall profile in terms of rat PK and ancillary profile such as clean hERG, clean hPXR, acceptable P450 inhibition profile, and good human hepatocyte clearance data (2.9 μL/m/M cell). Further profiling is in progress, and the result will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Ismail Kola and Malcolm MacCoss for their strong support of the program.

Supporting Information Available

Experimental procedures and spectral data for compounds. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supplementary Material

References

- Gottwald M. D.; Rozanski R. I. Rivastigmine, a brain-region selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor for treating Alzheimerʼs disease: review and current status. Expert Opin. Invest. Drugs 1999, 8, 1673. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths H. H.; Morten I.; Hooper N. M. Emerging and potential therapies for Alzheimerʼs disease. Expert Opin. Ther. 2008, 12, 704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. Progress in Alzheimerʼs disease drug discovery: An update. Curr. Opin. Invest. Drugs 2009, 10, 23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pissarnitski D. Advances in γ-secretase modulation. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 2007, 10, 392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah R. S.; Lee H.-G.; Zhu X.; Perry G.; Smith M. A.; Castellani R. J. Current approaches in the treatment of Alzheimerʼs disease. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2008, 62, 199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajendran L.; Schneider A.; Schlechtingen G.; Weidlich S.; Ries J.; Braxmeier T.; Schwille P.; Schulz J. B.; Schroeder C.; Simons M.; Jennings G.; Knoelker H.-J.; Simons K. Efficient inhibition of the Alzheimerʼs disease β-secretase by membrane targeting. Science 2008, 3205875520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy J.; Selkoe D. J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimerʼs disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science 2002, 297, 353. and references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza F.; Solfrizzi V.; Frisardi V.; Capurso C.; D'Introno A.; Colacicco A. M.; Vendemiale G.; Capurso A.; Imbimbo B. P. Disease-modifying approach to the treatment of Alzheimerʼs disease: From α-secretase activators to γ-secretase inhibitors and modulators. Drugs Aging 2009, 26, 537. and reference cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann S.; Hoettecke N.; Narlawar R.; Schmidt B. γ-Secretase as a target for AD. Med. Chem. Alzheimer's Dis. 2008, 193. and reference cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- Hyde L. A.; Mchugh N. A.; Chen J.; Zhang Q.; Manfra D.; Nomeir A. A.; Josien H.; Bara T.; Clader J. W.; Zhang L.; Parker E. M. Studies to investigate the in vivo therapeutic window of the γ-secretase inhibitor N2-[(2S)-2-(3,5-difluorophenyl)-2-hydroxyethanoyl]-N1-[(7S)-5-methyl-6-oxo-6,7-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,d]azepin-7-yl]-L-alaninamide (LY411,575) in the CRND8 mouse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 319, 1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joo Y.; Kim H.-S.; Woo R.-S.; Park C. H.; Shin K.-Y.; Lee J.-P.; Chang K.-A.; Kim S.; Suh Y.-H. Mefenamic acid shows neuroprotective effects and improves cognitive impairment in in vitro and in vivo Alzheimerʼs disease models. Mol. Pharmacol. 2006, 69, 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K. L. NSAID and Alzheimerʼs disease; possible answers and new questions. Mol. Psychiatry 2002, 7, 925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korfmacher W. A.; Cox K. A.; Ng K. J.; Veals J.; Hsieh Y.; Wainhaus S.; Broske L.; Prelusky D.; Nomeir A.; White R. E. Cassette-accelerated rapid rat screen: a systematic procedure for the dosing and liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure ionization tandem mass spectrometric analysis of new chemical entities as part of new drug discovery. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2001, 15, 335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See the Supporting Information for the detailed assay procedure.

- Kokotos G.; Noula C. Selective one-pot conversion of carboxylic acids into alcohols. J. Org. Chem. 1996, 61, 6994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.