Abstract

Systematic reviews have the potential to promote knowledge exchange between researchers and decision-makers. Review planning requires engagement with evidence users to ensure preparation of relevant reviews, and well-conducted reviews should provide accessible and reliable synthesis to support decision-making. Yet, systematic reviews are not routinely referred to by decision-makers, and innovative approaches to improve the utility of reviews is needed. Evidence synthesis for healthy public policy is typically complex and methodologically challenging. Although not lessening the value of reviews, these challenges can be overwhelming and threaten their utility. Using the interrelated principles of relevance, rigor, and readability, and in light of available resources, this article considers how utility of evidence synthesis for healthy public policy might be improved.

Systematic reviews can provide invaluable support to decision-making by providing readily prepared syntheses of quality-appraised evidence. Many research funders regard evidence synthesis as a mechanism for knowledge exchange.1 However, there are conflicting reports from decision-makers about the use and value of evidence syntheses.2,3 To improve the utility of systematic reviews, Lavis et al.3 have called for more innovation in the preparation of systematic reviews. Specifically, they highlight the need for improved relevance and accessibility of reviews, while maintaining rigor that is the underpinning value of a systematic approach.

Evidence synthesis for healthy public policy is typically complex and methodologically difficult, presenting challenges to the preparation of reviews that are relevant, rigorous, and readable (or accessible). Although policy relevant, the questions are often broad and imply inclusion of diverse data types and sources that can be difficult to synthesize.4,5 Consequently, rigorous reviews of broad complex policy relevant questions are costly and can take a long time, sometimes years, to complete.6–8 Complexity does not diminish the importance of the review questions, but decision-makers need evidence that is timely as well as relevant.9,10 Regardless of how rigorous and comprehensive a review is, syntheses that are not timely may no longer be relevant once completed.11 Moreover, long delays in dissemination of syntheses may perpetuate avoidable harm.12 The nature of available evidence may also present challenges to the rigor and readability of complex reviews. Statistical synthesis is rarely appropriate, the resulting narrative syntheses are often lengthy, and the link between the synthesis and the conclusions can be opaque. In addition, the dearth of well-conducted studies assessing the health impacts of public policies, such as housing investment, welfare changes, etc., will often restrict the review findings to establishing uncertainty and may question the utility of such reviews.13

This article describes the specific challenges of complex reviews, and what they can contribute to policymaking. The principles of relevance, rigor, and readability are presented, along with examples of how these principles can be incorporated into complex reviews for healthy public policy to help improve their utility. Finally, the value for money of long complex reviews is considered. Justification for, as well as ways and implications of, limiting a review are described.

WHAT MAKES HEALTHY PUBLIC POLICY REVIEWS COMPLEX

Complexity in a broad review may arise for a number of reasons (see the box at the top of the next page). The topic or intervention of interest to healthy public policy are often complex, whether generating new evidence in a primary study or synthesizing existing evidence. Interventions of interest may comprise multiple components that vary by setting or individual, and may involve multiple outcomes at different levels, presenting potential for dynamic and important but immeasurable interactions.14–16

Characteristics of Complex Reviews

| • Address complex topics with multiple potential, and poorly understood, interactions between intervention, mediators, and outcomes. |

| • Broad inclusion criteria introduce multiple sources of heterogeneity, for example, diverse contexts, populations, interventions, outcomes, study methods, and data types (qualitative, quantitative, theoretical). |

| • Address multiple questions. For example: is an intervention effective? Are there differential effects across different populations or contexts? What are the key mediating factors? Is the intervention cost effective? What is the impact on proxy measures of longer term outcomes? |

Broad review questions, typical within healthy public policy reviews, imply a broad scope as defined by the review inclusion criteria or population, intervention, comparison, outcomes, context, and study design (PICOCS). Reviews with broad inclusion criteria produce highly heterogeneous data that are an important and methodologically challenging source of complexity in reviews of healthy public policy.4 The breadth of the review may be limited by prioritizing what will be useful to evidence users (see the section on Relevance) and what is manageable and affordable (see the section on Resources), but may also be shaped by the nature and volume of available evidence. Over the past decade, the dearth of well-conducted cohort studies assessing the health impacts of social interventions has been well documented. The lack of high-quality evidence may require further broadening of inclusion criteria to allow the review to establish what is known, the nature of evidence available on a topic, and immediate evidence priorities. For example, it may be useful to consider data from uncontrolled studies or interrupted time series, or to include interventions that have some key similarity to the intervention of initial interest to the review.17 Reviews may not be restricted to empirical data. When the links between the dependent and independent variables are poorly understood, a systematic review of existing theory may help prioritize what empirical evidence should be subsequently reviewed.18

An additional source of complexity in a review may be the number of questions addressed. Questions that go beyond “what works?” enhance the usefulness and interpretation of effectiveness reviews and are increasingly recommended by both the Cochrane and Campbell Collaboration.19,20 Additional questions might investigate differential effects across population subgroups, contexts, or cost effectiveness.21 Reviews of healthy public policy interventions may also benefit from including synthesis of shorter term impacts on socioeconomic determinants of health and health outcomes.16 Public policy interventions are not regularly evaluated for health impacts; in addition, health impacts may not be realistically expected within the timeframe of an evaluation. Reviews that incorporate synthesis of proximal impacts on determinants of health may provide the best available evidence to indicate the potential for longer term health impacts, and may provide valuable data on poorly understood pathways to health impacts.6,22

TOO COMPLEX TO BE USEFUL OR SYNTHESIZABLE

The potential for intangible interactions between intervention and outcome, together with the dearth of evidence able to attribute impacts to interventions, is a common feature in many healthy public policy reviews. This can result in extreme levels of heterogeneity, and presents challenges to preparation of meaningful synthesis. The heterogeneity of study characteristics not only contraindicate statistical synthesis, but may also result in a narrative synthesis that is limited to summarizing the findings of individual studies. It might be questionable whether these complex data can or should be synthesized. The complexity in the resulting “syntheses” may be considered to be intolerable, serving only to confirm uncertainty and what is not known.11,13,23,24 However, the extent of complexity is a matter of perspective, and establishment of unknowns is important. There are few research or review questions that cannot be broken into many additional questions. Even within the relatively tidy realms of clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs), there may be few interventions that are truly simple.25 The heterogeneity of interventions as an obstacle to useful synthesis may also be a matter of perspective. Heterogeneity within a review may even be desirable where a configurative, rather than aggregative, approach to synthesis is necessary to investigate commonality across apparently diverse settings or interventions.26 Aspects of construct validity and external validity,27,28 or function29 may be common across nonidentical interventions. Synthesis at the level of commonality may be both conceptually appropriate and valuable, especially where there is little or no evidence on the specific intervention of interest.30 It has been argued that the development of theories or hypotheses about the mechanisms for the effects of complex interventions (social intervention theory), which draws on common features of multiple studies, may be a more valuable contribution to policy development than numerical approximations of effects from single studies.30,31

WHAT COMPLEX REVIEWS CAN CONTRIBUTE TO HEALTHY PUBLIC POLICY

Even the best available evidence on the health impacts of public policy is likely to be limited with respect to attributing impacts to an intervention, and the conclusions will often highlight uncertainty.11,13 This can be frustrating, but citing Popper, Pawson et al.24 draw attention to the innate uncertainties within science, advocating increased acceptance and acknowledgment of the limitations of evidence. Well-conducted reviews play an essential part in establishing what is known, differentiating levels of uncertainty, and establishing research and knowledge priorities.

A complex review, although likely to be limited with respect to effectiveness, should be able to contribute more than establishing uncertainty (see the box at the bottom of this page).13 Even when standardized effect sizes are not available or synthesizable, a review can map out the nature and quality of the best evidence available to address a question, along with details (e.g., relevance to the local context). Further mapping can establish the nature and direction of impacts, and mapping of intermediate impacts can help explain the absence of hypothesized health impacts. The nature of available evidence will shape what questions a synthesis can usefully address and the type of synthesis possible,4 and review methods can be applied across the spectrum of evidence sources to include empirical, theoretical, and methodological questions.32,33 Some examples of these are provided as data available as a supplement to this article at http://www.ajph.org.

What Complex Reviews Can Contribute to Healthy Public Policy

| • Identify appropriate questions for future systematic review and primary studies, and prioritize future research needs |

| • Map nature of best available evidence by location, intervention, study methods, and study quality |

| • Establish existence, nature, and direction of reported impact, including intermediate and adverse impacts |

| • Map existing theories to help develop related hypotheses for future review or study |

| • Develop typology of interventions |

| • Develop typology of methods |

| • Develop empirically supported theory |

Note. Example reviews are available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org.

CONDUCTING A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW: RELEVANCE, RIGOR, READABILITY

It is easy for broad, complex reviews to become overwhelming for the reviewer and the reader. A clearly defined and focused question is an essential part of any review. However, even apparently clear review questions can spawn multiple unseen difficulties. Many reviews have been abandoned because the review team, or their resources, have been exhausted by the volume of literature, the multiple emerging questions of interest, and the difficulties in analyzing the complex data in a way that is useful and maintains the integrity of the systematic review approach. In addition to rigor, systematic reviews must be relevant and readable if they are to be useful. These 3 principles (the 3 Rs) are interrelated and should be considered together when planning a review, and will likely require to be discussed in light of the fourth R (resources). The remainder of this article outlines how these 4 Rs may be applied to complex reviews for healthy public policy as a way to enhance utility of syntheses while maintaining the value of a transparent, systematic approach.

Relevance

Devoting time to developing a clearly defined and focused question is central to planning reviews that are relevant, as well as conceptually appropriate and manageable. This first requires a scoping process to identify the heterogeneity of the PICOC implied in the initial question and the consideration of factors that may mediate the impact of the intervention or independent variable. This process can help establish the potential scale of the initial review question and uncover multiple additional questions of interest that are not apparent at first. Logic models are recommended as a way of mapping the outcome of these discussions. The use of a visual map of the potential scope of the initial review question can help to refine the review question by prioritizing what is useful and also manageable within the available time (see the section on Resources).16 The timeliness of a review is also pertinent to relevance; relevance may diminish with increased time lags between initiation of a question and a completed review.

Discussion with topic experts and scoping searches to assess the nature and quantity of evidence that is likely to be available to answer a review question can contribute to development of the review scope and promote relevance. For example, advance knowledge that there are few RCTs of the intervention of interest may indicate the need for broader inclusion criteria to make use of the best available evidence and avoid the review process leading to an empty review. Similarly, knowledge of important differences in interventions and context across countries or over time may provide a justification for limiting the review scope by prioritizing what is most relevant.

Relevant reviews should reflect the needs of the end user of the review.34 Relevance of reviews can be enhanced by engaging with users when agreeing with the review question and scope, both at the start and throughout the review process. Evidence users can also advise on the interpretation and generalizability of the review findings, and appropriate dissemination to other evidence users. Involvement of evidence users in reviews can take many forms.35 Both the Cochrane and the Campbell Collaborations advocate user involvement in reviews as a way to promote the quality and relevance of reviews.36,37

Rigor

The key components of a systematic review are searching and identification of evidence, appraisal of the quality of evidence, and finally synthesis of evidence. Regardless of the methods used for each step, transparency is central to the systematic approach that aims to minimize bias in the selection and interpretation of evidence.33 Just as in primary research, the aim (in theory) is that the reader could replicate the methods and draw the same conclusions. Methods for searching, appraisal, and meta-analysis of effectiveness evidence from RCTs are well developed to maximize transparency. However, evidence on the health impacts of public policy is often difficult to identify, rarely comes from RCTs, and is rarely amenable to meta-analysis.4 Moreover, much of the published guidance on the conduct of systematic reviews focuses on questions of effectiveness.36,38

Identifying evidence for healthy public policy requires professional input from an information scientist to develop and conduct sophisticated, multipronged search strategies covering the scope of the PICOCS, as well as covering a wide range of sources beyond peer-reviewed journal publications and electronic bibliographic databases.39–41 Clear records of the search strategy and identified hits should accompany the published review to ensure transparency of the search scope and study selection.

Inclusion of nonrandomized studies (NRS) in systematic reviews, although common, continues to be the source of much debate.13,42 There are undoubted difficulties in interpreting evidence from NRS. Nevertheless, in the absence of RCTs, it is helpful to establish what is known drawing on the best available evidence, even if this is limited with respect to knowledge of effectiveness. When data are synthesized, assessment of validity is essential regardless of study design, and there are many tools available to assess data from nonexperimental quantitative and qualitative studies.42–45

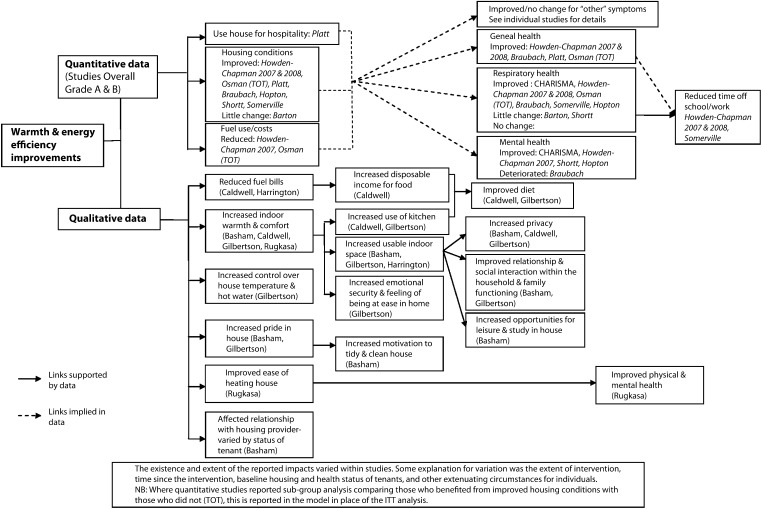

The heterogeneity of data and study design alone mean that evidence syntheses for healthy public policy will often require the data to be synthesized narratively. There is very little guidance on the process of, or agreed standards for narrative synthesis; consequently, the potential for bias in the process of interpreting the synthesized data are difficult to quantify. In any systematic review, it is important that the final synthesis reflects the quality of the data, that no study of similar quality to another receives undue emphasis, and that the links between the data and the conclusions of the synthesis are made clear. Popay et al.46 have identified common elements of narrative synthesis and recommend the following steps: development of a theory for the review to test; preliminary synthesis; and then an iterative process exploring relationships within and between studies and testing the robustness of the final synthesis. Although this is useful, the issue of transparency of the interpretation persists. Careful tabulation of the included evidence can promote transparency. When standardized effect sizes are available, forest plots provide a useful visual summary of included data, even if meta-analysis is not appropriate. When standardized effect sizes are not available to represent all the included quantitative data, an effect direction plot may be useful (Figure 1).47 Logic models may also be a useful tool to map included evidence. Figure 2 illustrates how data from qualitative and quantitative studies of warmth improvements were mapped in a recent systematic review of housing improvement. The final map represented agreement of preliminary versions prepared by 2 independent reviewers and included an indication of the data source and quality to maintain transparency and the integrity of the systematic approach.

FIGURE 1—

Example effect direction plot of health impacts for 3 categories of housing improvement.

Source. Reprinted with permission from Thomson and Thomas.47

FIGURE 2—

Example logic model mapping qualitative and quantitative data included in a systematic review of the health impacts of warmth and energy efficiency housing improvements.

Source. Reprinted with permission from Thomson et al.6

Readability

Readability of a review is important for both relevance and transparency (rigor). For a review to be relevant to evidence users, it must be accessible and the rationale for the synthesis’ conclusions must be clearly communicated.3,48 Preparation of plain language summaries that avoid esoteric methodological terms are useful but require careful writing to avoid misinterpretation by readers. When a review is unable to reach a clear conclusion, it is critical that the reason for and implication of the uncertainty is clearly communicated. In the messy world of social interventions, the limitations of science and evidence need to be better understood by both the reviewers and evidence users hoping for certainty.24

Transparency of the review process and the links between the data and the conclusions of the synthesis are essential. However, presenting lengthy text and data tables of complex data are unlikely to be accessible to anyone other than the most committed reader. There are too few examples of how data can be summarized, but the examples provided here (see the section on Rigor; Figures 1 and 2) demonstrate that 1-page summaries of complex data can be prepared. Further innovations to develop visual displays of complex data that retain the integrity of the systematic review process are required to promote both the rigor and utility of evidence synthesis of broad and complex topics, such as healthy public policy.

Resources

Available resources will shape the scope of a review, and prior consideration of appropriate use of resources is necessary to ensure a review is timely and focuses on what is relevant. Rapid reviews are one way of ensuring a timely product. Although, as Abrami et al.49 suggest, the term “brief” may be more appropriate to emphasize limited scope as well as time, as opposed to a rapid review where intensive use of multiple reviewers may not reduce expense.

When the volume of studies is overwhelming, limiting the inclusion criteria to the better quality studies provides a clear justification for limiting a review. Within healthy public policy, the volume of high quality studies will rarely be overwhelming. Rather, what may be overwhelming is the complexity, such as inclusion of multiple outcomes and multiple questions. Ensuring a review is manageable within available time and resources needs discussion between reviewers and end-users about the review’s scope to prioritize what is feasible and also relevant. This may require prioritizing breadth over depth, or vice versa.32 Reviews that prioritize depth over breadth most often restrict the inclusion criteria (PICOCS) in some way. The appropriateness and usefulness of narrow inclusion criteria will depend on relevance, as well as volume and quality, of available evidence.

Many healthy public policy issues point to the need for broad reviews, but limits for broad reviews can be tricky to negotiate with evidence users. Constraining the review depth may require limiting the volume of included studies or data analysis. Sensitive and sophisticated search strategies are still recommended, but limiting the number of search sources may reduce costs without significant impact on search results.41 Sampling from comprehensive searches can provide a useful way to limit the volume of included studies while still ensuring a representative or purposive sample.50 Prioritization of exactly what will be useful with respect to data extraction and critical appraisal may also reduce resource demands. Detailed evidence appraisal is an essential component of effectiveness reviews, but this may be of less value when the aim is to establish the nature and range of available evidence, or where the key interest is to establish the way in which an intervention has been evaluated (e.g., to identify study designs used and outcomes assessed).51,52 Additional time calculating standardized effect sizes and perform meta-analysis may be of questionable value when amenable data are not available across all included studies. In such a review, it may be of more use to tabulate the nature and direction of effects.

Pragmatic decisions to limit a review will lead to a tradeoff between preparation of a review that is timely and useful, and that is in-depth and comprehensive. Central to the rigor of the systematic review approach is transparency. When the volume of relevant evidence threatens preparation of a review that is both timely and useful to evidence users, it may be that transparency trumps comprehensiveness. As in any study, the limits and accompanying justification need to be clearly reported and also reflected on in terms of potential bias and shortcomings in the review conclusions, as well as the potential value of a more comprehensive review.

CONCLUSIONS

The breadth and complexity of synthesis for healthy public policy can be overwhelming, even for experienced reviewers. The competing need for rigor and timeliness is challenging and underlines the need for careful thought about how syntheses can best meet the needs of evidence users and also maintain the benefits of a rigorous, systematic approach. Restricting the coverage of a review will introduce limitations that need to be reflected on in the review’s conclusions, but may help produce timely syntheses. A review that is less comprehensive but is relevant and rigorous may be of greater use than a review that is produced years after it was needed, and may provide robust justification for resources to conduct a more comprehensive review. When sufficiently rigorous, restricted reviews may still merit dissemination in peer-reviewed journals,53,54 and may provide examples of innovations to improve utility of evidence synthesis for decision-makers. The interrelated principles of the 3Rs can help maximize the utility of evidence syntheses while retaining the integrity of a systematic approach. The fourth R may be a further requirement, not simply because of funding constraints, but also to promote timeliness (relevance).

Acknowledgments

The author is funded by the Chief Scientist Office at the Scottish Government Health Directorate as part of the Evaluating Social Interventions programme at the Medical Research Council & Chief Scientist Office Social & Public Health Sciences Unit (U.130059812).

The author acknowledges comments from Mark Petticrew on an earlier draft of this article.

Human Participant Protection

This article does not report data from human participants; therefore, no ethical approval was sought.

References

- 1.Tetroe JM, Graham ID, Foy R et al. Health research funding agencies’ support and promotion of knowledge translation: an international study. Milbank Q. 2008;86(1):125–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2007.00515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobbins M, Thomas H, O’Brien M-A, Duggan M. Use of systematic reviews in the development of new provincial public health policies in Ontario. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(4):399–404. doi: 10.1017/s0266462304001278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, Denis J-L, Golden-Biddle K, Ferlie E. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(suppl 1):35–48. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jackson N, Waters E. The Guidelines for Systematic Reviews of Health Promotion and Public Health Interventions Taskforce. The challenges of systematically reviewing public health interventions. J Public Health (Oxf) 2004;26(3):303–307. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdh164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shepperd S, Lewin S, Straus S et al. Can we systematically review studies that evaluate complex interventions? PLoS Med. 2009;(8):6. e1000086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. Housing improvements for health and associated socio-economic outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(2):CD008657. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008657.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thomson H, Petticrew M. Assessing the health and social effects on residents following housing improvement: a protocol for a systematic review of intervention studies. International Campbell Collaboration approved protocol. Available at: http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/61. Accessed May 15, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gibson M, Thomson H, Banas K, Bambra C, Fenton C, Bond L. Welfare to work interventions and their effects on health and well-being of lone parents and their children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(5):CD009820. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sheldon TA. Making evidence synthesis more useful for management and policy-making. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(suppl 1):1–5. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaRocca R, Yost J, Dobbins M, Ciliska D, Butt M. The effectiveness of knowledge translation strategies used in public health: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):751. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lavis JN, Posada FB, Haines PA, Osei E. Use of research to inform public policymaking. Lancet. 2004;364(9445):1615–1621. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17317-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gilbert R, Salanti G, Harden M, See S. Infant sleeping position and the sudden infant death syndrome: systematic review of observational studies and historical review of recommendations from 1940 to 2002. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(4):874–887. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petticrew M. Why certain systematic reviews reach uncertain conclusions. BMJ. 2003;326(7392):756–758. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7392.756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. London, UK: Medical Research Council; 2008. Developing and evaluating complex interventions. Available at: http://www.sphsu.mrc.ac.uk/Complex_interventions_guidance.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anderson LM, Petticrew M, Rehfuess E et al. Using logic models to capture complexity in systematic reviews. Res Synthesis Methods. 2011;2(1):33–42. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCartney G, Thomas S, Thomson Het al. The health and socioeconomic impacts of major multi-sport events: systematic review (1978-2008) BMJ 2010340:c2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorenc T, Clayton S, Neary D et al. Crime, fear of crime, environment, and mental health and well-being: mapping review of theories and causal pathways. Health Place. 2012;18(4):757–765. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cochrane Public Health Group. Guide for developing a Cochrane protocol. Available at: http://ph.cochrane.org/sites/ph.cochrane.org/files/uploads/Guide%20for%20PH%20protocol_Nov%202011_final%20for%20website.pdf. Accessed August 30, 2012

- 20.Tugwell P, Petticrew M, Robinson V, Kristjansson E, Maxwell L. Cochrane Equity Field Editorial Team. Cochrane and Campbell Collaborations, and health equity. Lancet. 2006;367(9517):1128–1130. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68490-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Greenhalgh T, Kristjansson E, Robinson V. Realist review to understand the efficacy of school feeding programmes. BMJ. 2007;335(7625):858–861. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39359.525174.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomson H, Atkinson R, Petticrew M, Kearns A. Do urban regeneration programmes improve public health and reduce health inequalities? A synthesis of the evidence from UK policy and practice (1980-2004) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):108–15. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.How systematic reviews can disappoint. Bandolier. 2001. Available at: http://www.medicine.ox.ac.uk/bandolier/band93/b93-6.html. Accessed August 30, 2012

- 24.Pawson R, Wong G, Owen L. Known knowns, known unknowns, unknown unknowns. Am J Eval. 2011;32(4):518–546. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Petticrew M. When are complex interventions “complex”? When are simple interventions “simple”? Eur J Public Health. 2011;21(4):397–398. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandelowski M, Voils CI, Leeman J, Crandell JL. Mapping the mixed methods–Mixed Research Synthesis Terrain. J Mix Methods Res. 2012;6(4):317–331. doi: 10.1177/1558689811427913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook TD, Campbell DT. Quasi-Experimentation: Design and Analysis for Field Settings. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Company; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Campbell DT. Relabeling internal and external validity for applied social scientists. New Dir Progr Eval. 1986;1986(31):67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004;328(7455):1561–1563. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipsey MW. What can you build with thousands of bricks? Musings on the cumulation of knowledge in program evaluation. New Dir Eval. 1997;1997(76):7–23. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: the promise of ‘realist synthesis’. Evaluation. 2002;8(3):340–358. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gough D, Thomas J, Oliver S. Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Syst Rev. 2012;1(1):28. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide. Oxford, UK: Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Black N. Evidence based policy: proceed with care. BMJ. 2001;323(7307):275–279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7307.275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rees R, Oliver S. Stakeholder perspectives and participation in reviews. In: Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J, editors. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. London: Sage; 2012. pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Green S, Higgins J. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0. August 30, 2012. Preparing a Cochrane review. Available at: http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Koonerup M, Sowden A. User involvement in the systematic review process. August 30, 2012 Available at: http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/artman2/uploads/1/Involvement_in_review_process.pdf. Accessed. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institute of Medicine US Committee on Standards for Systematic Reviews of Comparative Effectiveness Research. Finding What Works in Health Care: Standards for Systematic Reviews. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petticrew M. Systematic reviews from astronomy to zoology: myths and misconceptions. BMJ. 2001;322(7278):98–101. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7278.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Egan M, MacLean A, Sweeting H, Hunt K. Comparing the effectiveness of using generic and specific search terms in electronic databases to identify health outcomes for a systematic review: a prospective comparative study of literature search methods. BMJ Open. 2012;(3):2. e001043. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogilvie D, Hamilton V, Egan M, Petticrew M. Systematic reviews of health effects of social interventions: 1. Finding the evidence: how far should you go? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(9):804–808. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.034181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reeves BC, Deeks JJ, Higgins JP, Wells GA . on behalf of the Cochrane Non-Randomised Studies Methods Group. Assessing risk of bias in non-randomized studies (Section 13.5) In: Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. pp. 412–418. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies. Available at: http://www.ephpp.ca/PDF/Quality%20Assessment%20Tool_2010_2.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2013

- 44.Dixon-Woods M, Shaw RL, Agarwal S, Smith JA. The problem of appraising qualitative research. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(3):223–225. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2003.008714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noyes J, Popay J, Pearson A, Hannes K, Booth A . on behalf of the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group. Qualitative research and Cochrane reviews. In: Higgins J, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Version 5.1.0. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2011. pp. 571–592. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Popay J, Roberts H, Sowden A . Lancaster, UK: Institute of Health Research; 2006. Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product of the ESRC methods programme (version I) Available at: http://www.lancs.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications.php. Accessed May 15, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomson H, Thomas S. The effect direction plot: visual display of non-standardised effects across multiple outcome domains. Res Synthesis Methods. 2013;4(1):95–101. doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pettman TL, Hall BJ, Waters E, de Silva-Sanigorski A, Armstrong R, Doyle J. Communicating with decision-makers through evidence reviews. J Public Health (Oxf) 2011;33(4):630–633. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdr092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abrami PC, Borokhovski E, Bernard RM et al. Issues in conducting and disseminating brief reviews of evidence. Evid Policy: J Res Debate Pract. 2010;6(3):371–389. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brunton G, Stansfield C, Thomas J. Finding relevant studies. In: Gough D, Oliver S, Thomas J, editors. An Introduction to Systematic Reviews. London, UK: Sage; 2012. pp. 107–134. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thomson H, Atkinson R, Petticrew M, Kearns A. Do urban regeneration programmes improve public health and reduce health inequalities? A synthesis of the evidence from UK policy and practice (1980-2004) J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60(2):108–115. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.038885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buston K, Parkes A, Thomson H, Wight D, Fenton C. Parenting interventions for male young offenders: a review of evidence on what works. J Adolesc. 2012;35(3):731–742. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ganann R, Ciliska D, Thomas H. Expediting systematic reviews: methods and implications of rapid reviews. Implement Sci. 2010;5(1):56. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lehoux P, Tailliez S, Denis J-L, Hivon M. Redefining health technology assessment in Canada: diversification of products and contextualization of findings. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 2004;20(3):325–336. doi: 10.1017/s026646230400114x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]