Abstract

This report describes the investigation of a series of 5,7-disubstituted imidazo[5,1-f][1,2,4]triazine inhibitors of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) and insulin receptor (IR). Structure−activity relationship exploration and optimization leading to the identification, characterization, and pharmacological activity of compound 9b, a potent, selective, well-tolerated, and orally bioavailable dual inhibitor of IGF-1R and IR with in vivo efficacy in tumor xenograft models, is discussed.

Keywords: Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R); insulin receptor (IR); inhibitors, structure-based drug design (SBDD); cancer

Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF-1R) is a tetrameric transmembrane receptor tyrosine kinase activated by the binding of its cognate ligands IGF-1 and IGF-2.1,2 Preclinical studies show that activation of IGF-1R is required for cellular transformation and tumorigenesis, and inhibition of IGF-1R activity results in reduced growth of tumor xenografts.3−8 The importance of IGF-1R as an anticancer target is further underscored by its role in promoting resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapies, as well as molecular targeted therapies including HER2 and EGFR antagonists.3,9−13 Validation of IGF-1R as an anticancer target has been demonstrated by several monoclonal antibodies directed against the receptor's extracellular ligand binding domain in the clinical setting.14 However, efficacy mediated by IGF-1R-selective MAbs may be limited due to lack of coverage on the structurally related insulin receptor (IR). A growing body of data supports the importance of the IR in tumor cell proliferation and survival. Increased expression of IR is observed in several types of human cancers, and activation of IR by either insulin or IGF-2 results in enhanced proliferation of select human tumor cell lines.7,15−19 Moreover, bidirectional cross-talk between IGF-1R and IR can occur whereby inhibition of either receptor individually results in a compensatory increase in the phosphorylation state of the reciprocal receptor. For xenografts coexpressing IGF-1R and IR, dual inhibition of both receptors results in greater antitumor activity as compared to inhibiting IGF-1R alone.20 These results have provided a rationale for dual IGF-1R/IR inhibition as a treatment of cancer.

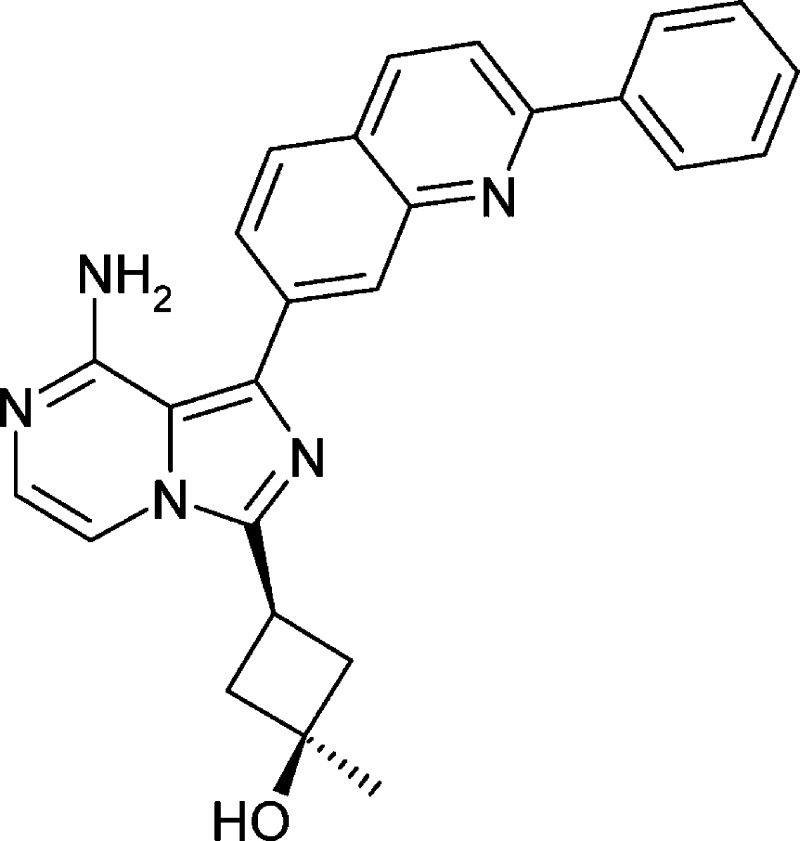

Recently, small molecular kinase inhibitors targeting both IGF-1R and IR have been developed and advanced into clinical studies.21 We have previously disclosed our work around imidazo[1,5-a]pyrazine derived small molecule dual IGF-1R/IR inhibitors, including the discovery of OSI-906, which is currently in advanced clinical development (Figure 1).22,23 While the main thrust of our IGF-1R/IR small molecule drug discovery efforts focused primarily on the imidazopyrazine series, alternate bioisosteric cores were also considered. Herein, we report the discovery of imidazo[5,1-f][1,2,4]triazine-based inhibitors of IGF-1R and IR and, particularly, compound 9b as a potent, selective, orally bioavailable dual IGF-1R and IR inhibitor with in vivo efficacy in mouse xenograft models.

Figure 1.

OSI-906.

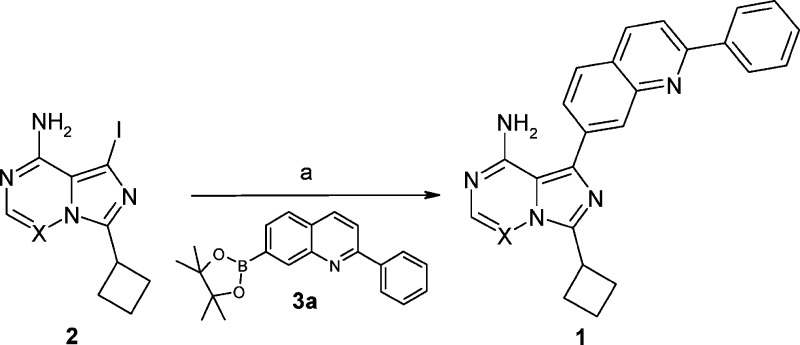

As shown in Scheme 1, the initial proof-of-concept 5,7-disubstituted imidazo[5,1-f][1,2,4]triazine compound 1a was synthesized via a Suzuki coupling of intermediate 2 (X = N)24 with boronate 3a. Compound 1a showed activity against IGF-1R both biochemically and cellularly (Table 1). However, a significant loss in potency was observed as compared to its counterpart 1b, an early lead compound from the imidazo[1,5-a]pyrazine series from which OSI-906 emerged.22 We hypothesized that the decrease in potency derived from weaker hinge hydrogen-bonding interactions due to a reduction in the electron richness of the donor and acceptor in 1a as compared to 1b. Differences in desolvation between the two agents may also play a contributing role. In either event, our efforts focused on increasing the potency through further modifications to 1a.

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Imidazo[5,1-f][1,2,4]triazine IGF-1R Inhibitor 1a.

Reagents and conditions: (a) PdCl2(dppf), K2CO3, dioxane−water (4:1, v:v), 95 °C, 70−75%.

Table 1. In Vitro Potency and Microsomal Stability of Compounds 1a and 1b.

| extraction ratios |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | X | IGF-1R biochemicala IC50 (μM) | IGF-1R cell mechanisticb IC50 (μM) | mouse | human |

| 1a | N | 0.27 | 0.33 | 0.89 | 0.91 |

| 1b | CH | 0.079 | 0.086 | 0.88 | 0.85 |

A 100 μM concentration of ATP.

LISN cell line.

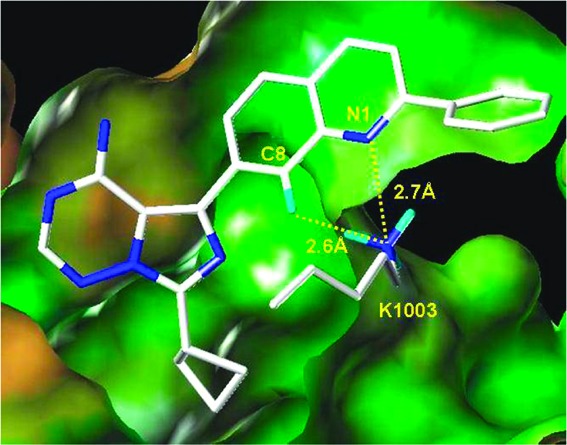

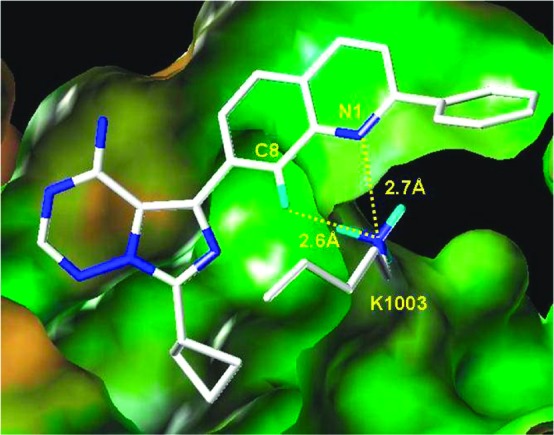

To expedite the lead optimization process, we decided to generate a focused library based on the structural insights and structure−activity relationship (SAR) developed around the earlier imidazo[1,5-a]pyrazine series.22,23 In that series, a hydrogen bond between the quinoline nitrogen and the basic amine of Lys1003, in addition to the hydrogen bonds to the hinge, are critical for activity. Furthermore, the imidazopyrazine C3 substituent, which exited out to solvent, allowed for the control of overall drug metabolism and pharmacokinetic (DMPK) properties. Hence, in the imidazotriazine series, improving the quinoline's acceptor pharmacophore became the major focus for improving potency. The C7 substituent was limited to three preferred substituted cyclobutyl analogues, which showed favorable DMPK properties and maintained both IGF-1R and IR target potency within the imidazopyrazine series. Detailed consideration of the quinoline's interaction with Lys1003 led to the hypothesis that a hydrogen bond acceptor at the C8 position of the quinolinyl moiety could further strengthen this interaction and thus enhance activity (Figure 2). The space adjacent to the C8 position is sterically congested, limiting replacements of the C8-H to either N8 or C8-F. Fluorine substitution is preferred, as the fluorine serves as a hydrogen bond acceptor, has small van der Waals volume, is metabolically inert, and approaches closer to the basic amine on K1003 than the lone pair on a ring nitrogen would.

Figure 2.

Modeled interaction of the quinoline moiety of 1a with the catalytic lysine (K1003) of IGF-1R.25 The lysine nitrogen is closer to the C8-H than to the N1. One proton points directly to the C8-H position in the lowest energy rotamer of the amine (depicted), while a nearly eclipsed conformation is required to point a proton directly at the N1 position.

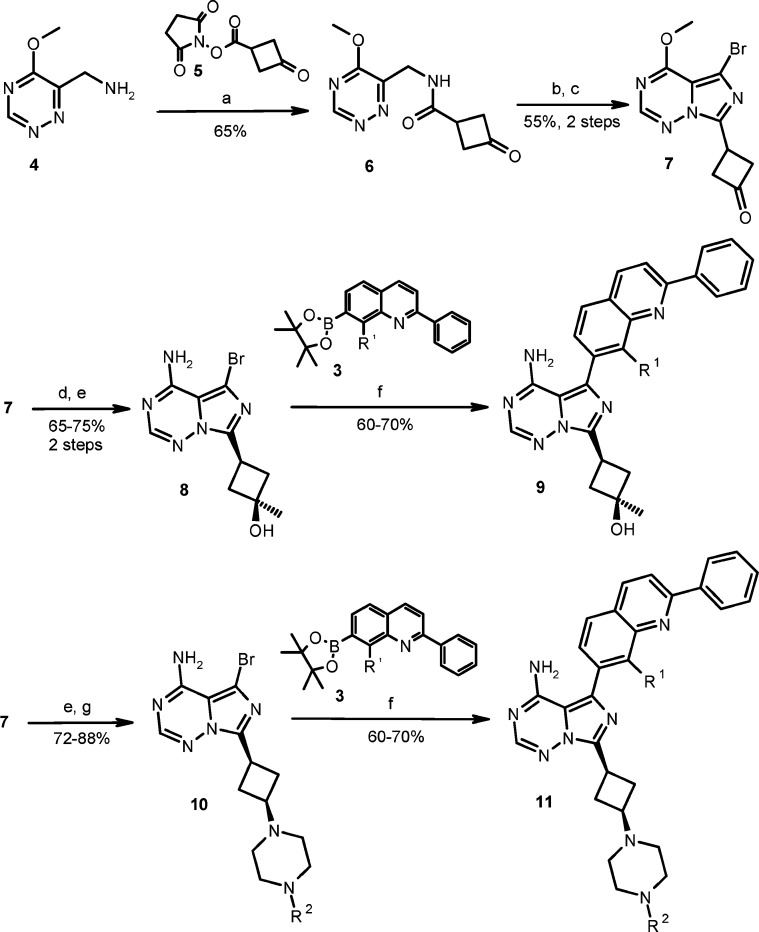

The synthetic chemistry used to prepare these advanced imidazotriazine analogues is shown in Scheme 2. Amide 6 was prepared from coupling of 5-methoxy-[1,2,4]triazin-6-ylmethylamine 4(24) with the activated cyclobutanone ester 5. Subsequent POCl3 cyclization followed by bromination afforded common intermediate 7. The cyclobutanone moiety of 7 was converted to a tertiary alcohol via a Grignard reaction yielding the cis-isomer stereoselectively. Ammonolysis gave compound 8, and compound 9 was obtained after a Suzuki coupling of 8 with boronate 3. Alternatively, 7 was subjected to ammonolysis followed by reductive amination to provided compound 10, which went on to a Suzuki coupling with boronate 3 to give final compound 11.

Scheme 2. General Synthesis Scheme.

Reagents and conditions: (a) 10% aqueous NaHCO3, THF, room temperature. (b) POCl3, DMF/MeCN, room temperature. (c) NBS, DMF. (d) MeMgCl, THF, −78 °C. (e) 2 N NH3 in iPrOH, 50 °C. (f) PdCl2(dppf), K2CO3, dioxane−water (4:1, v:v), 95 °C. (g) 1-Methylpiperazine or 1-formylpiperazine, NaBH(OAc)3, THF, room temperature.

As shown in Table 2, the addition of a fluorine atom at the C8 position of the quinoline ring boosted potency, in accord with the binding affinity hypothesis. These compounds inhibited IR and IGF-1R with similar potencies and showed improved in vitro microsomal stability when compared to 1a.

Table 2. Further SAR Explorations.

| extraction ratios |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | R2 | IGF-1R cell mechanistica IC50 (μM) | IR cell mechanisticb IC50 (μM) | mouse | human | |

| 9a | H | 0.15 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.71 | |

| 9b | F | 0.017 | 0.076 | 0.43 | 0.55 | |

| 11a | H | CHO | 0.026 | 0.26 | 0.24 | 0.66 |

| 11b | F | CHO | 0.008 | 0.048 | 0.44 | 0.65 |

| 11c | H | CH3 | 0.025 | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.64 |

| 11d | F | CH3 | 0.014 | 0.068 | 0.44 | 0.50 |

LISN cell line.

HepG2 cell line.

On the basis of their in vitro profiles, compounds 9b, 11b, and 11d were prioritized for mouse PK evaluation at 5 mg/kg for iv dose and 25 mg/kg for oral dose. Key mouse PK parameters for these compounds are summarized in Table 3. Compounds 11b and 11d showed lower exposure and bioavailability as compared to 9b, presumably due to their lower permeability as indicated by PAMPA data, especially at lower pH. The apparent oral bioavailability in excess of 100% for 9b may indicate saturation of a clearance mechanism. On the basis of its overall in vitro and DMPK profile, 9b was selected for further profiling.

Table 3. PAMPA Permeability and Mouse PKa of 9b, 11b, and 11d.

| PAMPA (nm/s) |

5 mg/kg iv dose |

25 mg/kg po dose |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH 5.0 | pH 7.4 | Cl (mL/min/kg) | Vss (L/kg) | Cmax(μM) | F % | |

| 9b | 1090 | 1100 | 4 | 1.0 | 20.5 | 162 |

| 11b | 204 | 1050 | 7 | 1.2 | 3.1 | 18 |

| 11d | 145 | 672 | 21 | 4.9 | 1.9 | 27 |

Compounds were dosed as freebase in female CD-1 mice.

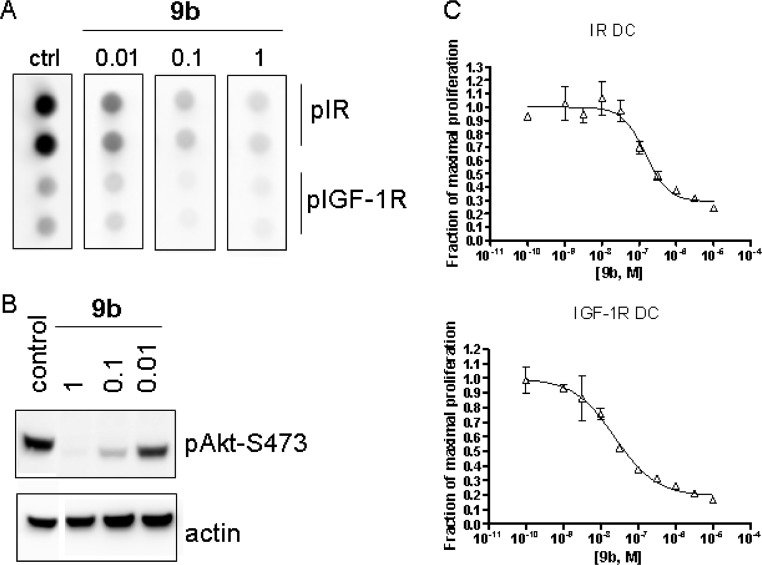

The in vitro and in vivo drug discovery cascade focused primarily on a GEO human colorectal tumor cell line. The GEO cell line was chosen since it represents a naturally occurring IGF-1R/IR/IGF2 autocrine loop driven tumor line and is sensitive to dual inhibition of IGF-1R and IR.26 Moreover, the line forms tumors in vivo and is an ideal model for tumor growth inhibition studies where the degree and duration of in vivo inhibition of tumor IGF-1R/IR phosphorylation could be correlated to in vivo efficacy. In this GEO cell line, 9b fully inhibited phosphorylation of IGF-1R and IR in vitro in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3a), leading to downstream inhibition of pAKT (Figure 3b), with antiproliferative effects correlating with IR and IGF-1R inhibition (EC50 = 130 nM). Furthermore, compound 9b was profiled in IGF-1R and IR driven DC tumor cell lines27 in vitro and emulated the observations observed in the GEO line, with antiproliferative effects in both lines correlating with inhibition of both pIGF-1R and pIR (Figure 3c). When taken together, these results indicate that inhibition of IGF-1R and IR leads to inhibition of downstream signaling of Akt, which results in the inhibition of proliferation in IGF-1R and IR driven cell lines in vitro.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of cellular signaling and proliferation by 9b. (a) Effect of varying concentrations of 9b on IGF-1R and IR phosphorylation in human GEO tumor cells. (b) Effect of varying concentrations of 9b on pAkt in human GEO tumor cells. (c) Effect of varying concentrations of 9b on cell proliferation for IR and IGF-1R DC tumor cell models.

The pharmacokinetics of 9b was evaluated in multiple species, including rat and rhesus monkey. As shown in Table 4, 9b demonstrated low clearance, good bioavailability, and good exposure in these two species when dosed orally once a day. In dose escalating PK studies, 9b gave dose proportional exposure in these species (data not shown). Repeated oral dosing in mouse, rat, and monkey did not show any evidence of a systematic increase or decrease in exposure as compared to single doses. Additionally, optimization of the salt form and dose vehicle was carried out on 9b. The combination of the hydrochloride salt of 9b and 40% w/v of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Trappsol) as the vehicle resulted in a solubility of approximately 60 mg/mL. A slight increase in exposure was observed in mice when compared to the free base form (Table 4). Thus, the HCl salt of 9b in combination with the 40% w/v of hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Trappsol) as the vehicle was used in further in vivo profiling studies.

Table 4. Median Pharmacokinetic Parameters for Compound 9b Following Oral Administration in Different Species.

| species | dose (mg/kg) | Cmax (μM) | AUC (ng h/mL) | CL (mL/min/kg)c | Vss (L/kg)c | F % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rat (F) | 25a | 11.3 | 62415 | 4 | 0.97 | 64 |

| rhesus monkey (M) | 30b | 10.8 | 31383 | 15 | 0.55 | 97 |

| mouse (F) | 25b | 35.2 | 240013 | 4 | 1.00 | 100 |

Free base of 9b was dosed; vehicle, 50:50 PEG-400:25 mM tartaric acid.

HCl salt of 9b was dosed; vehicle, 40% w/v hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Trappsol).

A 5 mg/kg iv dose.

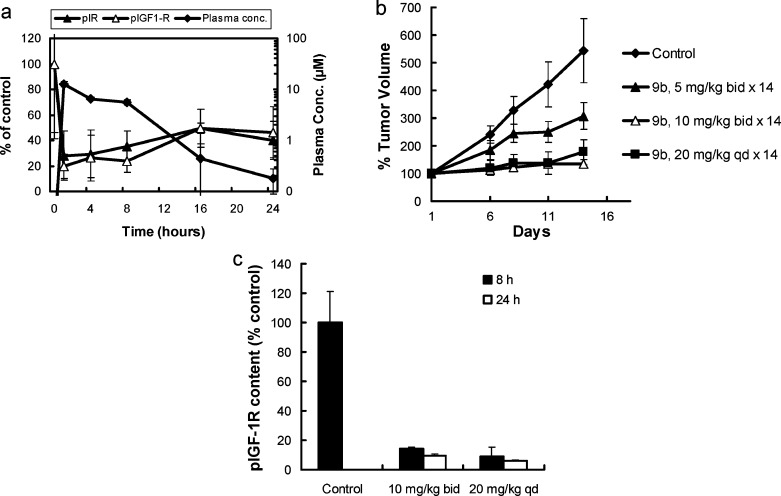

Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic evaluation of 9b in vivo in the GEO colon carcinoma xenograft model demonstrated that a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg provided >70% sustained inhibition of tumor IGF-1R phosphorylation up to 8 h, corresponding to plasma levels of >4 μM. Partial recovery of pIGF-1R content (50% inhibition at 16 h) was observed with a concomitant drop in the plasma drug levels to 0.38 μM by 16 h (Figure 4a). Similar inhibitory effects of 9b on tumor insulin receptor phosphorylation were observed (Figure 4a). Twice daily administration at a dose of 10 mg/kg for 14 days resulted in 91% tumor growth inhibition (TGI) in the GEO model (Figure 4b). Furthermore, a once daily dose of 20 mg/kg resulted in comparable TGI of 85% (Figure 4b), whereas 5 mg/kg bid only provided 31% TGI. The compound was well tolerated with limited body weight loss (<10%). In this TGI study, tumors from control and 9b treated animals were removed after the last dose to investigate target inhibition in tumor tissue. Compound 9b at the efficacious doses of 10 mg/kg bid or 20 mg/kg qd provided >70−90% sustained inhibition of tumor IGF-1R phosphorylation for a full 24 h post last dose (Figure 4c). At the lower, nonefficacious dose of 5 mg/kg bid for 14 days, only 40−50% pIGF-1R and pIR inhibition was observed (data not shown), suggesting that near complete and sustained target inhibition may be required for maximum efficacy in this IGF-1R/IR driven model. Blood glucose and insulin levels were also measured after the last dose showing only transient elevation up to 8 h with return to normal levels by 24 h for the efficacious dose levels. The antitumor activity of 9b was extended into additional tumor models. For example, in a human IGF-1R overexpressing NIH 3T3 xenograft model (LISN), 9b demonstrated 100% TGI when dosed at a well-tolerated dose of 10 mg/kg bid for 14 days (data not shown).

Figure 4.

(a) Correlation of inhibition of IGF-1R and IR phosphorylation and plasma drug concentration in GEO tumor xenografts following oral dosing with 10 mg/kg of 9b. The plotted data are means ± SDs. Phospho-IGF-1R and pIR contents in GEO tumors are expressed as a percentage of control pIGF-1R or pIR content from vehicle-treated animals, respectively. (b) Dose−response efficacy of 9b in GEO xenograft models. Plotted data are mean tumor volumes expressed as a percentage of initial volume ± SE. Compound 9b was dosed on a once daily (qd) or twice daily (bid) schedule for 14 days. (c) Inhibition of IGF-1R phosphorylation in GEO tumor xenografts following 14 days of oral dosing with 9b. Data are means ± SEs.

The kinase selectivity of 9b was determined by screening against a panel 167 kinases using an in-house Caliper EZ Reader mobility shift assay. Compound 9b only showed significant activity (>50% inhibition at 1 μM concentration) against IGF-1R and IR.28 Compound 9b did not show any significant CYP inhibition against major CYP isoforms (Table 5). Preclinical safety screens of 9b against a broad range of 68 enzymes, receptors, and ion channels at 10 μM concentration did not reveal any significant off-target activities. Thus, 9b is a highly selective dual IGF-1R/IR inhibitor. The plasma protein binding as measured by ultracentrifugation for 9b in multiple species was moderate (Table 5). Compound 9b is not genotoxic (Ames negative ± S9) and showed no detectable off-target toxicological effects in a 14 day rat toxicology study, even at doses and exposures above those predicted to be required for efficacy.

Table 5. Plasma Protein Binding and Cytochrome P450 Inhibition of 9b.

| plasma protein binding (ultracentrifugation) | % | CYP isoform | IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| mouse | 98.5 | 3A4 | >25.0 |

| rat | 96.6 | 1A2 | >25.0 |

| human | 97.3 | 2D6 | >25.0 |

In summary, a 5,7-disubstituted imidazo[5,1-f][1,2,4]triazine series was conceived as an isosteric alternative to the imidazo[1,5-a]pyrazine dual IGF-1R/IR inhibitors. Optimization of the interactions with K1003 compensated for the observed potency loss due to the core change. Further chemical modifications improved the DMPK properties of the series leading to 9b, a potent, selective IGF-1R/IR dual inhibitor with favorable druglike properties. It possesses a profile comparable to that of OSI-906, including excellent PK and tolerability in multiple species and robust in vivo antitumor activity in several mouse xenograft tumor models.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Yingjie Li and Viorica M. Lazarescu for analytical support, Paul Maresca, Pete Meyn, Roy Turton, and the Leads Discovery Group for conducting in vitro ADMET studies, and Dr. Bob Zahler for consultation. We also gratefully acknowledge Dr. Andrew P. Crew for valuable discussions pertaining to the synthesis of the imidazo[5,1-f][1,2,4]triazine as well as Drs. Maryland Franklin and Qun-Sheng Ji for their overarching contributions to the OSI IGF-1R programs.

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic procedure, analytical data for compound 9b, and procedures for in vitro and in vivo assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supplementary Material

References

- Adams T. E.; Epa V. C.; Garrett T. P.; Ward C. W. Structure and function of the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2000, 57, 1050–1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Meyts P.; Whittaker J. Structural biology of insulin and IGF1 receptors: implications for drug design. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2002, 1, 769–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck E.; Eyzaguirre A.; Rosenfeld-Franklin M.; et al. Feedback mechanisms promote cooperativity for small molecule inhibitors of epidermal and insulin-like growth factor receptors. Cancer Res. 2008, 68, 8322–8332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Echeverria C.; Pearson M. A.; Marti A.; et al. In vivo antitumor activity of NVP-AEW541-A novel, potent, and selective inhibitor of the IGF-IR kinase. Cancer Cell 2004, 231–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeRoith D.; Roberts C. T. Jr. The insulin-like growth factor system and cancer. Cancer Lett. 2003, 195, 127–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins A. S.; Mackintosh C.; Martin D. H.; et al. Insulin-like growth factor I receptor pathway inhibition by ADW742, alone or in combination with imatinib, doxorubicin, or vincristine, is a novel therapeutic approach in Ewing tumor. Clin. Cancer Res. 2006, 3532–3540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak M. Insulin and insulin-like growth factor signalling in neoplasia. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2008, 915–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell C.; Rubini M.; Rubin R.; Liu J. P.; Efstratiadis A.; Baserga R. Simian virus 40 large tumor antigen is unable to transform mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1993, 90, 11217–11221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen G. W.; Saba C.; Armstrong E. A.; et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling blockade combined with radiation. Cancer Res. 2007, 67, 1155–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen B. D.; Baker. D. A.; Soderstrom. C.; et al. Combination therapy enhances the inhibition of tumor growth with the fully human anti-type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751,871. Clin. Cancer Res. 2005, 11, 2063–2073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guix M.; Faber. A. C.; Wang S. E.; et al. Acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer cells is mediated by loss of IGF-binding proteins. J. Clin. Invest. 2008, 2606–2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nahta R.; Yuan L. X.; Zhang B.; Kobayashi R.; Esteva F. J. Insulin-like growth factor-I receptor/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 heterodimerization contributes to trastuzumab resistance of breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 11118–11128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng X.; Sachdev D.; Zhang H.; Gaillard-Kelly M.; Yee D. Sequencing of type I insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibition affects chemotherapy response in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009, 15, 2840–2849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne R. Commercial interest waxes for IGF-1 blockers. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008, 26, 719–720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasca F.; Pandini G.; Scalia P.; et al. Insulin receptor isoform A, a newly recognized, high-affinity insulin-like growth factor II receptor in fetal and cancer cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1999, 5, 3278–3288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgino F.; Belfiore A.; Milazzo G.; et al. Overexpression of insulin receptors in fibroblast and ovary cells induces a ligand-mediated transformed phenotype. Mol. Endocrinol. 1991, 3, 452–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heuson J. C.; Legros N. Effect of insulin and of alloxan diabetes on growth of the rat mammary carcinoma in vivo. Eur. J. Cancer 1970, 4, 349–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalli K. R.; Falowo O. I.; Bale L. K.; Zschunke M. A.; Roche P. C.; Conover C. A. Functional insulin receptors on human epithelial ovarian carcinoma cells: implications for IGF-II mitogenic signaling. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 3259–3267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavelic K.; Pavelic Z.; Poljak-Blazi M.; Sverko V. The effect of insulin on the growth of transplanted tumors in mice. Biomedicine 1979, 125–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck E.; Gokhale P.; Koujak S.; Brown E.; Eyzaguirre A.; Tao N.; Rosenfeld-Franklin M.; Lerner L.; Chiu I.; Wild R.; Pachter J.; Epstein D.; Miglarese M.. Compensatory insulin receptor (IR) activation upon inhibition of insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF-1R): Rationale for co-targeting IGF-1R and IR in cancer. Abstract #1654, AACR Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li R.; Pourpak A.; Morris S. W. Inhibition of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) tyrosine kinase as a novel cancer therapy approach. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4981–5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill M.; Ji Q.; Coate H.; Cooke A.; Dong H.; Feng L.; Foreman K.; Rosenfeld-Franklin M.; Honda A.; Mak G.; Mulvihill K.; Nigro A.; O'Connor M.; Pirrit C.; Steinig A.; Siu K.; Stolz K.; Sun Y.; Tavares P.; Yao Y.; Gibson N. Novel 2-phenylquinolin-7-yl-derived imidazo[1,5-a]pyrazines as potent insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2008, 16, 1359–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvihill M.; Cooke A.; Rosenfeld-Franklin M.; Buck E.; Foreman K.; Landfair D.; O'Connor M.; Pirrit C.; Sun Y.; Yao Y.; Arnold L.; Gibson N.; Ji Q. Discovery of OSI-906: A selective and orally efficacious dual inhibitor of the IGF-1 receptor and insulin receptor. Future Med. Chem. 2009, 1, 1153–1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner D. S.; Dong H.; Kadalbajoo M.; Laufer R. S.; Tavares-Greco P. A.; Volk B. R.; Mulvihill M. J.; Crew A. P. Synthetic approaches to 5,7-disubstituted imidazo[5,1-f][1,2,4]triazin-4-amines. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010, 3899–2901. [Google Scholar]

- Altering the inhibitor structure from PQIP (PDB ID 3D94) by deleting the attachment off the cyclobutyl moiety and modifying the 5-position of the imidazopyrazine from CH to N yields the depicted model.

- Ji Q.; Mulvihill M.; Rosenfeld-Franklin M.; Cooke A.; Feng L.; Mak G.; O'Connor M.; Yao Y.; Pirritt C.; Buck E.; Eyzaguirre A.; Arnold L.; Gibson N.; Pachter J. A novel, potent, and selective insulin-like growth factor-I receptor kinase inhibitor blocks insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling in vitro and inhibits insulin-like growth factor-I receptor dependent tumor growth in vivo. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2007, 6, 2158–2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner L.; Liu Q.; Yang J.; et al. Generation of in vivo tumor models driven by Insulin-Like Growth Factor Receptor IGF1R and their use in the development of OSI-906, a selective IGF1R inhibitor. Abstracts A233, AACR-NCI-EORTC International Conference: Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapeutics, Nov 15−19, 2009, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- See the Supporting Information.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.