Abstract

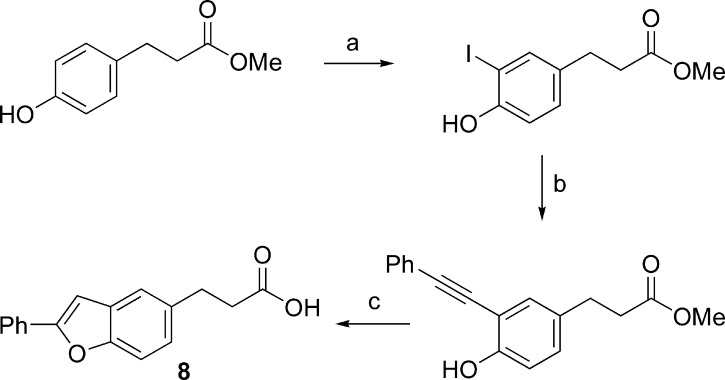

The free fatty acid 1 receptor (FFA1 or GPR40), which is highly expressed on pancreatic β-cells and amplifies glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, has emerged as an attractive target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Several FFA1 agonists containing the para-substituted dihydrocinnamic acid moiety are known. We here present a structure−activity relationship study of this compound family suggesting that the central methyleneoxy linker is preferable for the smaller compounds, whereas the central methyleneamine linker gives higher potency to the larger compounds. The study resulted in the discovery of the potent and selective full FFA1 agonist TUG-469 (29).

Keywords: Diabetes, FFA1, FFAR1, GPR40, fatty acids, drug discovery

With an estimated 285 million cases worldwide and an expected 480 million cases by 2030, diabetes represents a threat to the economy and human well being, and the development of improved therapies is urgent.1,2 Recently, the receptor GPR40, now renamed to FFA1,3 was found to be activated by medium- and long-chain fatty acids, to be highly expressed on pancreatic β-cells, and to potentiate glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS).4−6 FFA1 is also present in the endocrine cells of the gastrointestinal tract and has been reported to mediate free fatty acid (FFA) stimulated secretion of GLP-1 and GIP.7 Thus, the receptor appears to act as an important nutrient sensor and metabolic regulator and to stimulate insulin secretion by direct action on the β-cells and possibly also indirectly via the incretin system. FFA1 is of considerable interest as a new target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes (T2D) since insulin secretion is promoted without the associated risk of hypoglycemia.8,9

FFAs have long been known to potentiate GSIS, but they are also linked to β-cell dysfunction,10 and it is unclear at present whether FFA1 mediates one or both of these effects. Whereas some studies with FFA1-deficient mice indicate that both effects were mediated by the receptor and that FFA1 antagonists may therefore be of therapeutic interest for T2D,11,12 other investigations confirmed the potentiation of GSIS but found no evidence for lipotoxic effects.13,14 Tan and co-workers demonstrated that a selective FFA1 agonist (compd B, Figure 1) continued to promote GSIS with no indications of lipotoxicity after chronic administration, in contrast to fatty acids that resulted in impaired insulin secretion.15 This outcome is also supported by several other recent studies.16−18 Thus, although the issue is still controversial, most evidence currently supports FFA1 agonists as promising for the treatment of T2D.

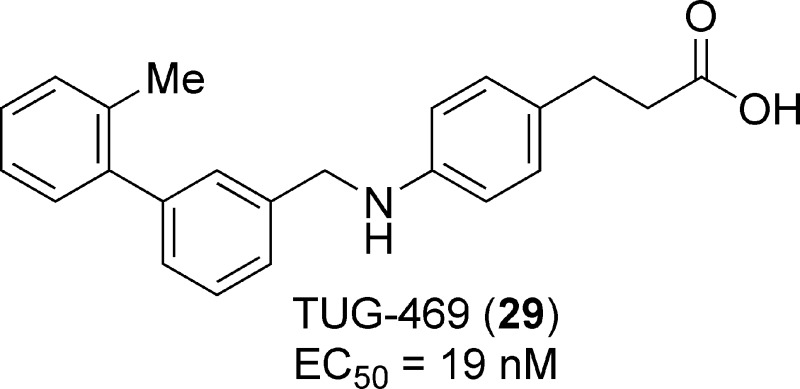

Figure 1.

Thiazolidinedione and dihydrocinnamic acid FFA1 agonists.6,15,19,22,23.

Both saturated and unsaturated FFAs with more than 10 carbon atoms act as agonists on FFA1.4−6,8,9 The ability of FFA1 to stimulate insulin secretion at elevated glucose levels attracted immediate attention, and several series of FFA1 agonists as well as some antagonists have since been described, many of these containing the para-substituted dihydrocinnamic acid or the corresponding thiazolidinedione moiety (Figure 1).15,19−27 Herein, we describe structure−activity investigations around the lead compound 1 and the para-substituted dihydrocinnamic acids, which resulted in the identification of the potent agonist 29 (TUG-469).

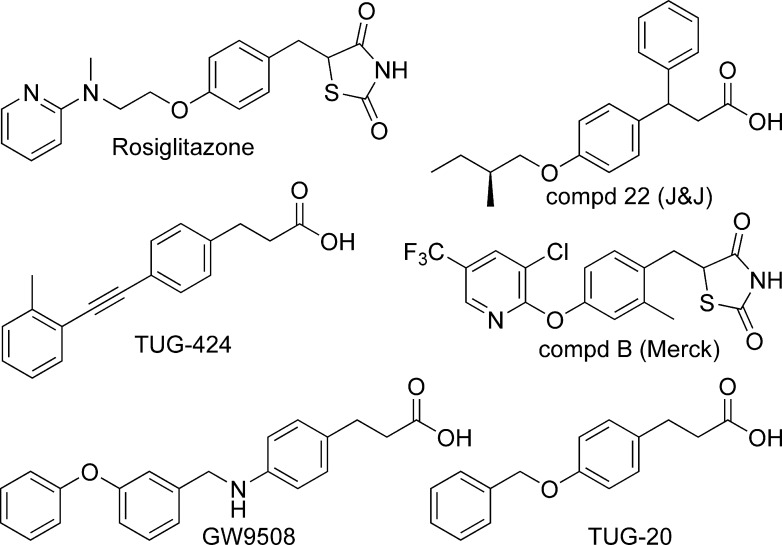

It was discovered in 2003 that several thiazolidinedione PPARγ agonists, including the antidiabetic drug rosiglitazone (Figure 1), also possess FFA1 agonistic activity.6 Presuming that thiazolidinediones and FFAs share a common binding site within FFA1, which has now been confirmed,28 we included structural information from the thiazolidinedione agonists in the design of a small library of carboxylic acids to mimic constrained fatty acids in the search for more potent and selective FFA1 agonists. The library, consisting of commercial and readily synthesized compounds, resulted in several active compounds including the two outstanding hits TUG-14, which was optimized to TUG-424 (Figure 1),23 and TUG-20 (1), which served as the lead structure for the work presented here. The disclosure of GW9508 and related compounds by GSK directed our attention to the central linker unit, and we set out to investigate if the methyleneoxy or the methyleneamino linker was preferred. The initial hit 1 and analogues were synthesized as outlined in Scheme 1. Biaryl analogues were prepared by Suzuki coupling of the corresponding halobenzyloxy ester or the free halobenzylamino acid using a practical protocol with Pd(OAc)2 and K2CO3 in PEG-400 in open air. Synthesis of the constrained benzofurane 8 is outlined in Scheme 2.

Scheme 1.

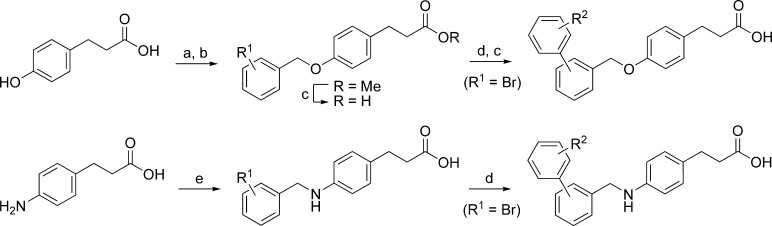

Scheme 2.

Replacing the central oxygen of 1 by a nitrogen (2) produced a compound with somewhat reduced activity in the calcium mobilization assay (Table 1). We were interested to probe if the −CH2X− linker functioned only as a flexible spacer between the central and the terminal benzene rings; thus, compounds 3 and 4 with inverted linkers were synthesized and evaluated. Both compounds turned out more than an order of magnitude less potent than the corresponding 1 and 2, indicating a key role of the linker. Replacing the central heteroatom by a methylene group (5) produces a pure hydrocarbon tail more closely resembling the endogenous FFA ligands. Despite increased lipophilicity, the compound turned out to be significantly less potent than 1 and 2, indicating that the methyleneoxy and the methyleneamino linkers play specific roles in the recognition of the receptor binding site by the ligands. A methyl substituent on the methyleneoxy linker (6) resulted in significant loss of activity, as did an iodo substituent on the central ring vicinal to the benzyloxy (7).

Table 1. Exploration of the Central Linker and Conformational Constraints.

| compd | Y | X | R | hFFA1 (Ca2+) pEC50 (efficacy)a | LE −Δgb | PPARγ % at 100 μMc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CH2 | O | H | 6.34 ± 0.02 (100) | 0.46 | 7 |

| 2d | CH2 | NH | H | 6.12 ± 0.03 (89) | 0.42 | 7 |

| 3 | O | CH2 | H | 5.20 ± 0.03 (88) | 0.38 | NA |

| 4 | NH | CH2 | H | 4.67 ± 0.01 (101) | 0.34 | NA |

| 5 | CH2 | CH2 | H | 5.44 ± 0.04 (116) | 0.39 | |

| 6 | CH(Me) | O | H | 5.48 ± 0.02 (106) | 0.38 | |

| 7 | CH2 | O | I | 4.90 ± 0.02 (81) | 0.34 | 42 |

| 8 | 5.61 ± 0.07 (92) | 0.38 | NA | |||

| 9e | C≡C | H | 6.70 ± 0.02 (108) | 0.48 | ||

Efficacy is given as % response relative to 10 μM 1.

LEs were calculated from the formula −Δg = RT ln(EC50), presuming that EC50 approximates the dissociation constant. Values are given in kcal mol−1 per nonhydrogen atom.29

Activation relative to 1 μM rosiglitazone.

Previously reported (pEC50 = 5.1 ± 0.4).21

Previously reported.23

The specific effect of the central linkers might be due to hydrogen bond interactions, conformational effects, or overall effects on the dipolar momentum. Conformational analysis revealed that the methyleneoxy (1) and in particular the methyleneamino (2) are preferentially oriented in the plane of the central benzene ring, whereas the inverted linkers (3 and 4) and the ethylene linker (5) are preferentially oriented orthogonally to the central benzene. The benzofurane derivative 8 (Scheme 2), designed as a constrained planar analogue of 1, turned out almost an order of magnitude less active but still demonstrates that the receptor binding pocket can accommodate the conformation with the phenyl group extended in the plane of the central ring. Notably, replacing the flexible methyleneoxy or methyleneamino with an alkyne (9) results in a significant increase in potency up to pEC50 = 6.70 and confirms that the binding pocket can accommodate the fully extended molecule.23

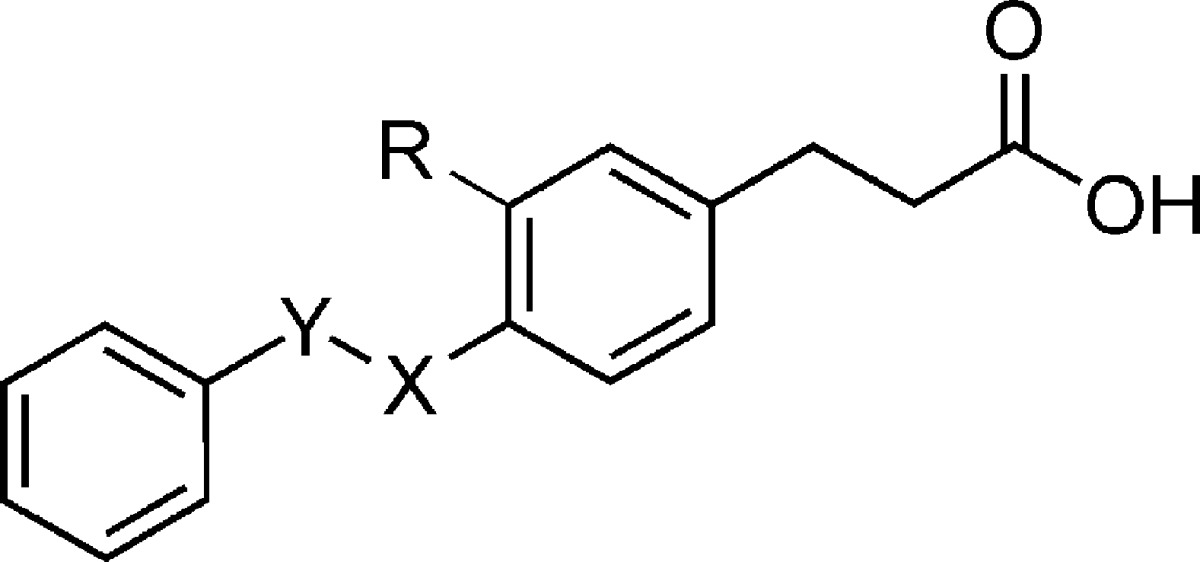

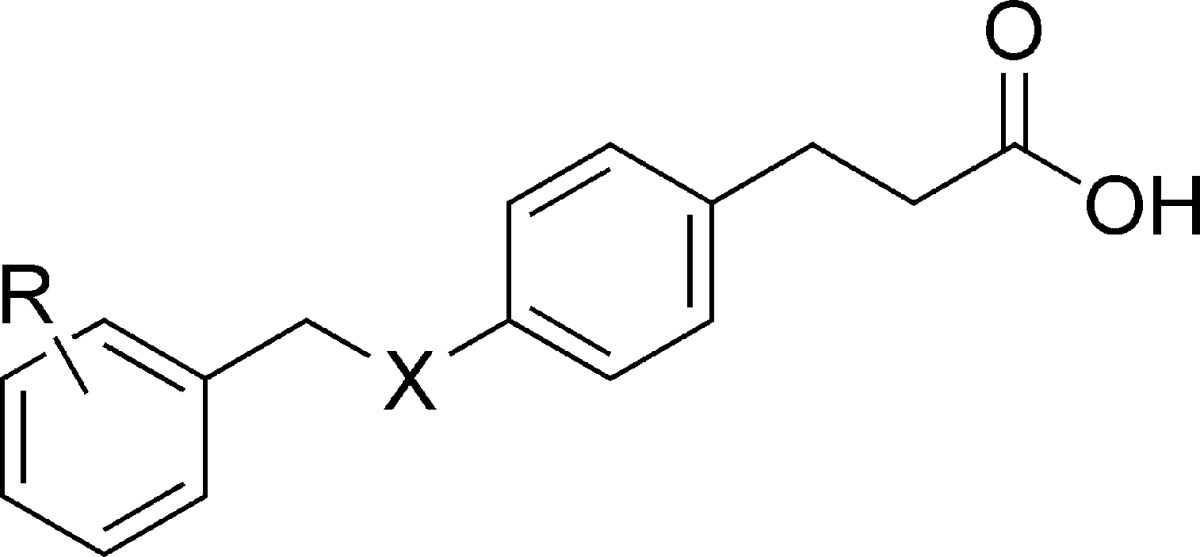

An initial screen of the terminal ring with bromo substitutents (10−13) demonstrated that substitution is tolerated in all positions and preferred in the meta-position, whereas the polar 3-nitrile analogue (14) indicated that the meta-substituent should be nonpolar to increase potency (Table 2). The nonpolar 3-CF3 indeed produced a significant improvement in analogues 15 and 16.

Table 2. Substituted 4-Benzyloxy and 4-Benzylamino Dihydrocinnamic Acids.

| compd | R2 | X | hFFA1 (Ca2+) pEC50 (efficacy)a | LE −Δgb | PPARγ % at 100 μMc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GW9508d | 3-OPh | N | 7.54 ± 0.04 (103) | 0.40 | 54 |

| compd Be | 6.75 ± 0.04 (103) | 0.34 | |||

| 10 | 4-Br | O | 6.26 ± 0.03 (98) | 0.43 | |

| 11 | 2-Br | O | 6.35 ± 0.04 (99) | 0.43 | |

| 12 | 3-Br | O | 7.05 ± 0.02 (99) | 0.49 | 19 |

| 13 | 3-Br | N | 6.76 ± 0.04 (110) | 0.46 | 27 |

| 14 | 3-CN | O | 6.28 ± 0.02 (102) | 0.41 | |

| 15 | 3-CF3 | N | 6.73 ± 0.05 (102) | 0.40 | |

| 16 | 3-CF3 | O | 7.08 ± 0.03 (103) | 0.42 | |

| 17 | 3-OPh | O | 7.24 ± 0.03 (98) | 0.38 | 51 |

| 18 | 4-OPh | O | 6.69 ± 0.03 (98) | 0.35 | 23 |

| 19f | 4-OPh | N | 6.74 ± 0.03 (100) | 0.35 | 34 |

| 20g | 4-Ph | O | 6.04 ± 0.05 (97) | 0.33 | NA |

| 21h | 4-Ph | N | 6.38 ± 0.02 (92) | 0.34 | 23 |

| 22 | 3-Ph | O | 6.87 ± 0.05 (105) | 0.38 | 25 |

| 23 | 3-Ph | N | 7.27 ± 0.02 (101) | 0.40 | 33 |

| 24 | 2-Ph | O | 5.72 ± 0.04 (97) | 0.31 | |

| 25 | 2-Ph | N | 5.97 ± 0.02 (97) | 0.33 | --i |

| 26 | 3-(4-MeC6H4) | O | 6.31 ± 0.03 (86) | 0.33 | 15 |

| 27 | 3-(4-MeC6H4) | N | 6.90 ± 0.04 (92) | 0.36 | 31 |

| 28 | 3-(2-MeC6H4) | O | 7.30 ± 0.05 (112) | 0.39 | 37 |

| 29 | 3-(2-MeC6H4) | N | 7.73 ± 0.04 (114) | 0.41 | 86 |

| 30 | 3-(2-MeOC6H4) | O | 6.92 ± 0.04 (105) | 0.35 | 37 |

| 31 | 3-(2-MeOC6H4) | N | 7.16 ± 0.03 (109) | 0.36 | 51 |

Efficacy is given as % response relative to 10 μM 1. The maximal response of 1 was determined to 123% relative to linoleic acid.

LEs were calculated from the formula −Δg = RT ln(EC50), presuming that EC50 approximates the dissociation constant. Values are given in kcal mol−1 per nonhydrogen atom.29

Activation relative to 1 μM rosiglitazone.

Reported previously (pEC50 = 6.71).21

Tested with 0.05% BSA because of poor solubility.

Reported previously (pEC50 = 6.6 ± 0.2).21

Toxic at 100 μM and 15% activation at 10 μM.

GW9508 is central in the series and was included to enable direct comparison under the same conditions.19−21 We also synthesized the potent thiazolidinedione FFA1 agonist disclosed by Merck (compd B) to directly compare our compounds to one with established efficacy in animal models.15,25

In contrast to compounds with smaller benzyl substituents for which the methyleneoxy analogues were more potent (1/2, 12/13, and 16/15), the methyleneoxy analogue of GW9508 (17), carrying a larger meta-phenoxy substituent, turned out less potent than GW9508. As expected, the corresponding para-phenoxy analogues 18 and 19 exhibited lower potency. All N/O pairs of the ortho-, meta-, and para-biphenyl (20−25) compounds were synthesized and tested, confirming the meta-position as the generally preferred and the methyleneamino linker as preferred for the larger aromatic substituents, which is advantageous as the methyleneamino linker produces less lipophilic compounds, on average with calculated log P 0.4 units lower than the corresponding methyleneoxy compounds. A 2-methyl substituent on the meta-phenyl (28 and 29) resulted in significant further increase of activity for both linkers, whereas the corresponding 4-methyl substituent (26 and 27) rather decreased activity. The 2-methoxy compounds 30 and 31 exhibit activities very close to the unsubstituted 22 and 23, suggesting that the increased activity of 28 and 29 might be a consequence of increased lipophilicity and a close fit around the 2-methyl in the binding site.

Ligand efficiency (LE) reflects the contribution of each nonhydrogen atom to the activity of a compound and has become a widely accepted measure to avoid oversized molecules from the optimization process.29 Although the LE dropped from 0.46 for 1 to 0.41 for 29 (Tables 1 and 2), maintenance of a value >0.4 is satisfactory.

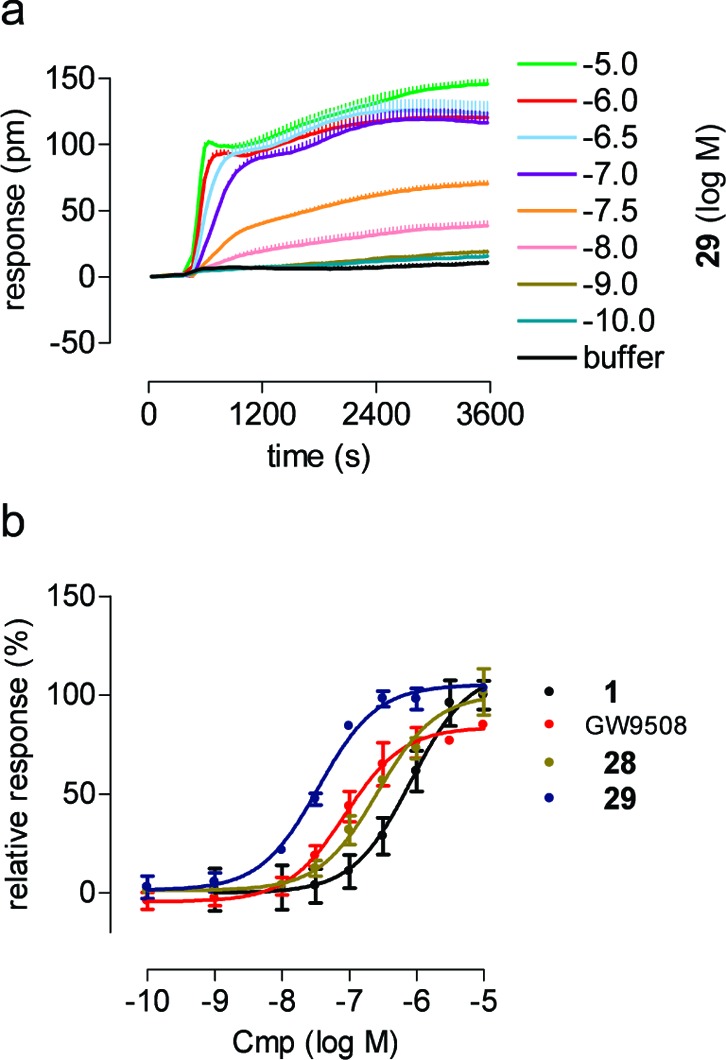

The lead compound 1, GW9508, and the most potent methyleneoxy analogue 28 and methyleneamine analogue 29 were tested in a dynamic mass redistribution (DMR) assay to obtain integrated cellular response profiles of FFA1 transfected cells.30 Dose−response curves from DMR assays (Figure 2) give pEC50 values that correlate well with the calcium data (Table 2).

Figure 2.

DMR analysis of FFA1 agonists. (a) hFFA1 transfected 1321N1 cells were challenged with the indicated concentrations of 29 (n > 2), and the wavelength shift (pm) was monitored over time as a measure of receptor activation. (b) Dose−response curves: GW9508 pEC50 = 7.06 ± 0.11 (red line); 1 pEC50 = 6.08 ± 0.15 (black line); 28 pEC50 = 6.58 ± 0.09 (gold line); and 29 pEC50 = 7.46 ± 0.06 (blue line).

None of the compounds have significant activity on the related receptors FFA2 (GPR43) or FFA3 (GPR41). Because the antidiabetic target PPARγ, like FFA1, is activated by fatty acids and thiazolidinediones, it is reasonable to expect that FFA1 ligands may also possess PPARγ activity. Most of the compounds turned out to exhibit PPARγ agonist activity at 100 μM (Tables 1 and 2), but none show significant activity at 1 μM, and all compounds are >100-fold selective for FFA1.

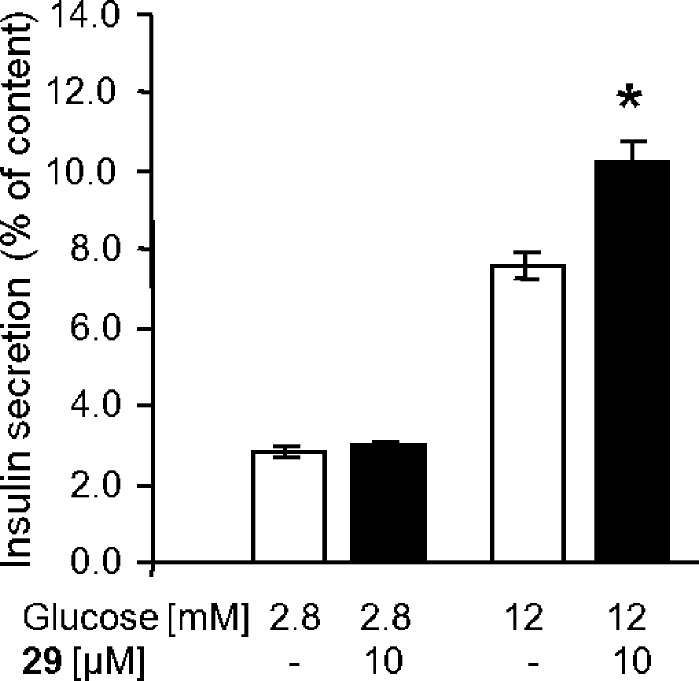

Being carboxylic acids and related to FFAs, it is natural to expect that the compounds might bind strongly to serum albumin. The activities of 29 and 28 as FFA1 agonists were, however, only moderately affected by increasing amounts of BSA, with pEC50 values of 7.83 ± 0.04 and 7.09 ± 0.04, respectively, in the presence of 0.05% BSA and 7.35 ± 0.03 and 6.25 ± 0.03 with 0.5% BSA. The effect of 29 on insulin secretion was examined in the rat β-cell line INS-1E. Glucose (12 mM) stimulated insulin secretion 2.7-fold, and 29 was competent to amplify GSIS by 55% but did not affect insulin secretion at low glucose concentrations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Effect of 29 on insulin secretion from the pancreatic rat INS-1E β-cells at basal and stimulatory glucose concentrations. Shown are mean values ± SEMs (n = 3). The asterisk indicates significance to 12 mM glucose (p < 0.001).

In conclusion, structure−activity relationships of para-substituted dihydrocinnamic acid FFA1 agonists have been explored with focus on the central linker and terminal aromatic ring. The results indicate that the central methyleneoxy linker is preferred for compounds with small substituents on the terminal phenyl, whereas the methyleneamino linker appears to be preferred for compounds with larger aromatic substituents. The effort converted the initial lead compound 1 into the potent and selective agonist 29, a compound closely related to GW9508, while maintaining LE > 0.4 kcal/mol per nonhydrogen atom. A high activity in the label-free DMR assay, satisfactory tolerance to BSA, high selectivity over relevant receptors, and the confirmed ability to increase GSIS in a pancreatic β-cell line indicate that 29 has potential for further development and will be a useful tool in future studies of FFA1.

Supporting Information Available

Synthetic procedures and compound characterization, procedures for calcium assay, DMR assay, PPARγ assay, and insulin secretion assays. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

We thank the Danish Council for Independent Research/Technology and Production (Grant 09-070364) and the German Research Foundation (DFG Grants UL140/7-1 and GRK1302/1) and the Dr. Hilmer Foundation for financial support.

Supplementary Material

References

- International Diabetes Federation. The Diabetes Atlas, 4th ed.; October, 2009; http://www.diabetesatlas.org.

- Unwin N.; Gan D.; Whiting D. The IDF Diabetes Atlas: Providing evidence, raising awareness and promoting action. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2010, 87, 2–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The name FFA1 is designated by the International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology to the receptor previously called GPR40 (http://www.iuphar.org/).

- Itoh Y.; Kawamata Y.; Harada M.; Kobayashi M.; Fujii R.; Fukusumi S.; Ogi K.; Hosoya M.; Tanaka Y.; Uejima H.; Tanaka H.; Maruyama M.; Satoh R.; Okubo S.; Kizawa H.; Komatsu H.; Matsumura F.; Noguchi Y.; Shinobara T.; Hinuma S.; Fujisawa Y.; Fujino M. Free fatty acids regulate insulin secretion from pancreatic beta cells through GPR40. Nature 2003, 422, 173–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe C. P.; Tadayyon M.; Andrews J. L.; Benson W. G.; Chambers J. K.; Eilert M. M.; Ellis C.; Elshourbagy N. A.; Goetz A. S.; Minnick D. T.; Murdock P. R.; Sauls H. R.; Shabon U.; Spinage L. D.; Strum J. C.; Szekeres P. G.; Tan K. B.; Way J. M.; Ignar D. M.; Wilson S.; Muir A. I. The orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR40 is activated by medium and long chain fatty acids. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 11303–11311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotarsky K.; Nilsson N. E.; Flodgren E.; Owman C.; Olde B. A human cell surface receptor activated by free fatty acids and thiazolidinedione drugs. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003, 301, 406–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edfalk S.; Steneberg P.; Edlund H. Gpr40 is expressed in enteroendocrine cells and mediates free fatty acid stimulation of incretin secretion. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2280–2287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoddart L. A.; Smith N. J.; Milligan G. International Union of Pharmacology. LXXI. Free Fatty Acid Receptors FFA1,-2, and-3: Pharmacology and Pathophysiological Functions. Pharmacol. Rev. 2008, 60, 405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellendorph P.; Johansen L. D.; Brauner-Osborne H. Molecular Pharmacology of Promiscuous Seven Transmembrane Receptors Sensing Organic Nutrients. Mol. Pharmacol. 2009, 76, 453–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newgard C. B.; McGarry J. D. Metabolic coupling factors in pancreatic β-cell signal transduction. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1995, 64, 689–719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steneberg R.; Rubins N.; Bartoov-Shifman R.; Walker M. D.; Edlund H. The FFA receptor GPR40 links hyperinsulinemia, hepatic steatosis, and impaired glucose homeostasis in mouse. Cell Metab. 2005, 1, 245–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownlie R.; Mayers R. M.; Pierce J. A.; Marley A. E.; Smith D. M. The long-chain fatty acid receptor, GPR40, and glucolipotoxicity: Investigations using GPR40-knockout mice. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2008, 36, 950–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latour M. G.; Alquier T.; Oseid E.; Tremblay C.; Jetton T. L.; Luo J.; Lin D. C. H.; Poitout V. GPR40 is necessary but not sufficient for fatty acid stimulation of insulin secretion in vivo. Diabetes 2007, 56, 1087–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kebede M.; Alquier T.; Latour M. G.; Semache M.; Tremblay C.; Poitout V. The fatty acid receptor GPR40 plays a role in insulin secretion in vivo after high-fat feeding. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2432–2437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C. P.; Feng Y.; Zhou Y. P.; Eiermann G. J.; Petrov A.; Zhou C. Y.; Lin S. N.; Salituro G.; Meinke P.; Mosley R.; Akiyama T. E.; Einstein M.; Kumar S.; Berger J. P.; Mills S. G.; Thornberry N. A.; Yang L. H.; Howard A. D. Selective small-molecule agonists of G protein-coupled receptor 40 promote glucose-dependent insulin secretion and reduce blood glucose in mice. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2211–2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasumi K.; Esaki R.; Iwachidow K.; Yasuhara Y.; Ogi K.; Tanaka H.; Nakata M.; Yano T.; Shimakawa K.; Taketomi S.; Takeuchi K.; Odaka H.; Kaisho Y. Overexpression of GPR40 in Pancreatic beta-Cells Augments Glucose-Stimulated Insulin Secretion and Improves Glucose Tolerance in Normal and Diabetic Mice. Diabetes 2009, 58, 1067–1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan H.; Hoos L. M.; Liu L.; Tetzloffl G.; Hu W. W.; Abbondanzo S. J.; Vassileva G.; Gustafson E. L.; Hedrick J. A.; Davis H. R. Lack of FFAR1/GPR40 Does Not Protect Mice From High-Fat Diet-Induced Metabolic Disease. Diabetes 2008, 57, 2999–3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alquier T.; Peyot M. L.; Latour M. G.; Kebede M.; Sorensen C. M.; Gesta S.; Kahn C. R.; Smith R. D.; Jetton T. L.; Metz T. O.; Prentki M.; Poitout V. Deletion of GPR40 Impairs Glucose-Induced Insulin Secretion In Vivo in Mice Without Affecting Intracellular Fuel Metabolism in Islets. Diabetes 2009, 58, 2607–2615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe C. P.; Peat A. J.; McKeown S. C.; Corbett D. F.; Goetz A. S.; Littleton T. R.; McCoy D. C.; Kenakin T. P.; Andrews J. L.; Ammala C.; Fornwald J. A.; Ignar D. M.; Jenkinson S. Pharmacological regulation of insulin secretion in MIN6 cells through the fatty acid receptor GPR40: Identification of agonist and antagonist small molecules. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 148, 619–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrido D. M.; Corbett D. F.; Dwornik K. A.; Goetz A. S.; Littleton T. R.; McKeown S. C.; Mills W. Y.; Smalley T. L.; Briscoe C. P.; Peat A. J. Synthesis and activity of small molecule GPR40 agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2006, 16, 1840–1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown S. C.; Corbett D. F.; Goetz A. S.; Littleton T. R.; Bigham E.; Briscoe C. P.; Peat A. J.; Watson S. P.; Hickey D. M. B. Solid phase synthesis and SAR of small molecule agonists for the GPR40 receptor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 1584–1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song F. B.; Lu S. F.; Gunnet J.; Xu J. Z.; Wines P.; Proost J.; Liang Y.; Baumann C.; Lenhard J.; Murray W. V.; Demarest K. T.; Kuo G. H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of 3-aryl-3-(4-phenoxy)-propionic acid as a novel series of G protein-coupled receptor 40 agonists. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 2807–2817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen E.; Urban C.; Merten N.; Liebscher K.; Karlsen K. K.; Hamacher A.; Spinrath A.; Bond A. D.; Drewke C.; Ullrich S.; Kassack M. U.; Kostenis E.; Ulven T. Discovery of Potent and Selective Agonists for the Free Fatty Acid Receptor 1 (FFA(1)/GPR40), a Potential Target for the Treatment of Type II Diabetes. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 7061–7064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tikhonova I. G.; Sum C. S.; Neumann S.; Engel S.; Raaka B. M.; Costanzi S.; Gershengorn M. C. Discovery of novel Agonists and antagonists of the free fatty acid receptor 1 (FFAR1) using virtual screening. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 625–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou C. Y.; Tang C.; Chang E.; Ge M.; Lin S. N.; Cline E.; Tan C. P.; Feng Y.; Zhou Y. P.; Eiermann G. J.; Petrov A.; Salituro G.; Meinke P.; Mosley R.; Akiyama T. E.; Einstein M.; Kumar S.; Berger J.; Howard A. D.; Thornberry N.; Mills S. G.; Yang L. H. Discovery of 5-aryloxy-2,4-thiazolidinediones as potent GPR40 agonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 1298–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries P. S.; Benbow J. W.; Bonin P. D.; Boyer D.; Doran S. D.; Frisbie R. K.; Piotrowski D. W.; Balan G.; Bechle B. M.; Conn E. L.; Dirico K. J.; Oliver R. M.; Soeller W. C.; Southers J. A.; Yang X. J. Synthesis and SAR of 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinolin-1-ones as novel G-protein-coupled receptor 40 (GPR40) antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2400–2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharate S. B.; Nemmani K. V. S.; Vishwakarma R. A. Progress in the discovery and development of small-molecule modulators of G-protein-coupled receptor 40 (GPR40/FFA1/FFAR1): an emerging target for type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2009, 19, 237–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith N. J.; Stoddart L. A.; Devine N. M.; Jenkins L.; Milligan G. The Action and Mode of Binding of Thiazolidinedione Ligands at Free Fatty Acid Receptor 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 17527–17539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins A. L.; Groom C. R.; Alex A. Ligand efficiency: A useful metric for lead selection. Drug Discovery Today 2004, 9, 430–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y.; Frutos A. G.; Verklereen R. Label-free cell-based assays for GPCR screening. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screening 2008, 11, 357–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.