Abstract

A 50 year old man presented to Eye clinic University clinical centre Tuzla with bilateral visual impairment. Clinical examination revealed low visual acuity and keratoconus in both eyes, white cataract in right eye and diabetic retinopathy in left eye. Ultrasonography examination was normal. The patient underwent Trypan blue capsule staining, phacoemulsification and implantation of intraocular lens Alcon AcrySof SN60T9 16 D spherical and 6.0 D cylinder power. Phacoemulsification went uneventful and early postoperative recovery was successful. Visual acuity improved to 0,8 and fundus examination revealed background diabetic retinopathy. Postoperative follow up two years after surgery showed no signs of keratoconus progression and visual acuity maintained the same.

Keywords: phacoemulsification, cataract, corneal ectasia

1. INTRODUCTION

Keratoconus is characterized by progressive corneal protrusion and thinning, leading to irregular astigmatism and impairment of visual function (1). It is essentially a bilateral condition, though presentation can be markedly asymmetric (1,2). Keratoconus is multifactorial progressive disease that usually starts in puberty, generally slowly progresses in early years and usually stabilizes in fourth and fifth decade of life (2). The reported incidence of keratoconus ranges from 1.3 to 25 per 100 000 per year and prevalence ranges from 8.8 to 229 per 100 000 (1).

Several options for management of keratoconus are available such as: spectacles and soft contact lenses in early cases, rigid gas permeable lenses, deep anterior lamellar keratoplasty, photo refractive keratectomy, intrastromal corneal ring segments and corneal crosslinking for moderate and corneal transplantation surgery for severe cases (1, 2). Toric intraocular lenses (IOL) can be a viable solution for patients with irregular astigmatism due to keratoconus (3) and cataract patients with keratoconus (4–10).

The purpose of this report is to present results of two year follow up in a case of stabile keratoconus and white cataract successfully treated with phacoemulsification and toric intraocular lens implantation.

2. CASE REPORT

A 50-year-old man with history of low vision for more than 10 years presented to Eye clinic University clinical centre Tuzla. Ocular history revealed bilateral gradual vision decrease 20 years ago. The patient never used contact lenses and has one pair of spectacles with -5 D, which he uses for the last 6 years. Systemic assessment revealed history of diabetes mellitus for 6, arterial hypertension for 12 and posttraumatic stress syndrome for 15 years. The patient allegedly regularly takes his medication and smokes at least 20 cigarettes a day. He is war veteran, unemployed and has negative family history of ocular or systemic diseases. The patient submitted documentation of ophthalmic examinations in the last 6 years, with unchanged refraction, stabile corneal finding and noted cataract progression.

Complete ophthalmologic examination on presentation revealed the following findings: the corrected distance visual acuity (CDVA) was light perception in the right eye and 0.4 with–3.0 Dsph ~–5.0 Dcyl axis 82° in the left eye. Tonometry was 15.6 mm Hg in both eyes. Slitlamp examination revealed a central corneal protrusion and mature white cataract in the right eye and central corneal protrusion with Vogt striae and incipient posterior subcapsular cataract in the left eye. Fundus in the right eye was not visible due to cataract and the fundus in the left eye showed signs of background diabetic retinopathy with regular optical coherence topography (OCT) finding. Ultrasonography examination, motility examination and pupil responses were normal in both eyes.

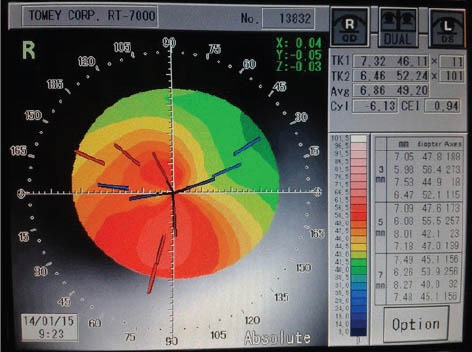

Different treatment options were discussed and patient insisted on cataract surgery and preoperative preparations were made. Corneal topography (Auto Ref-Topographer RT-7000; Tomey, USA) in the both eyes showed oblique axis of corneal astigmatism and pattern consistent with keratoconus with the thinnest portion of the cornea decentred inferotemporally (Figure 1). Keratometry indices in the right eye were as following: K = (K–47.2) = 2.4 D; I-S = 2.0 D; AST = (SimK1–SimK2) = 7.53 D; SRAX = 25° and KISA% = (K) x (I-S) X (AST) x (SRAX) x 100 / 300 = 301.2% (11). Keratometry measurements by simulated K, automated (Auto Ref-Topographer RT-7000 Tomey, USA) and manual keratometry (Javal-Schiote; Rodenstock, Dusseldorf, Germany) determined the K = 49.6 D (K1 = 45.79 D, K2 = 53.32 D) with the agreement on the steepest meridian location at 99°. Axial length (LAX) measured with B scan biometry and both contact and immersion A scan (Ultra Scan; Alcon, Fort Worth, USA) biometry was 22.3 mm in right and 23.06 mm in left eye. Anterior chamber depth (ACD) was 3.19 mm in right and 3.66 mm in the left eye. Dioptric intraocular lens (IOL) power of 18 D was calculated using SRK II formula (IOL power = A–0.9K–2.5LAX) and manufacturer web based program–toric IOL calculator was used to determine IOL cylinder power and axis alignment (http://www.acrysoftoriccalculator.com).

Figure 1.

Preoperative corneal topography

Estimated corneal astigmatism was 7.53 D and highest toric IOL available at the market in January 2012 was Acrysof SN60T9 (Alcon, Ltd., Fort Worth, USA) with 6.0 cylinder power at the IOL plane (4.1D at the corneal plane). Clear cornea cut 2.8 mm at the steepest meridian 99° with surgically induced astigmatism (SIA) 1 D (12) was planned. Remaining 2.5 D of corneal cylinder were calculated in the spherical equivalent. Calculated spherical IOL power is 18D, but 16D IOL was used in order to leave a small myopic refraction (13).

Preoperative cornea marking at the 0° and 180° positions was done, at slit lamp in vertical position with the patient sitting upright and looking forward. Marking of the corneal steepest meridian and incision site at 99° was performed at the operating table with a degree gauge. Trypan blue anterior capsule staining and capsulorhexis were performed followed by phacoemulsification (Infinity Vision System; Alcon, Fort Worth, USA). Surgery proceeded uneventfully and measured phaco-time was 23 seconds. Implantation of toric intraocular lens Acrysof SN60T9 (16.0 D spherical and 6.0 D cylinder power) was performed using Monarch III IOL delivery system cartridge B (Alcon, Fort Worth, USA).

Postoperative small amounts of keratitis and corneal oedema were noted. The patient was treated with topical 0.1% dexamethasone (Maxidex; Alcon, Couvreur, Belgium) and 0.3% tobramycin (Tobrex, Alcon, Couvreur, Belgium) both 4 times daily for three weeks. Seven days after cataract extraction uncorrected distance visual acuity (UDVA) in right eye improved to 0.8 and postoperative fundus examination showed signs background diabetic retinopathy. At the last follow-up (24 months postoperatively) UDVA in right eye maintained 0.8, with a manifest refraction of –0.5 Dsph and -1.25 Dcyl axis 100° and CDVA in left eye 0,2 with –3.5 Dsph ~–5.0 Dcyl axis 82°. Topography finding in both eyes was stabile with SIA in right eye 1.42 (remaining topography astigmatism 6.1 Dcyl axis 101°). Slitlamp examination revealed stabile cornea, no signs of IOL rotation and alignment axis placed at 100° and no signs posterior capsule opacification in right eye and corneal protrusion with Vogt striae and posterior subcapsular cataract in the left eye (Figure 2). Posterior segment of both eyes was stabile with background diabetic retinopathy and regular OCT findings. No postoperative complications occurred during follow up period and the patient is satisfied.

Figure 2.

Corneal topography 2 years after surgery

3. DISCUSSION

Cataract extraction is the only treatment option for a patient with developed cataract. Any surgical intervention in keratoconic eye can increase the risk of progressive and irreversible corneal ectasia (14). Stability and stage of keratoconus must be considered if any surgical intervention is to be performed. Young age, a positive family history, changes in refractive error and possibility of eye rubbing are known risk factors associated with keratoconus progression (1, 2). Because of the patient’s age of 50 at the presentation, negative family history and documented stabile corneal finding for the last 6 years, the risk of keratoconus progression was considered as minimal.

Cataract extraction in patient with keratoconus is challenging task, due to numerous difficulties related to intraoperative and postoperative complications, IOL power estimation, namely interpretation of keratometry readings, determining the astigmatism axis and accurate axial length measurement. Minimally invasive one step surgical procedure is ideal solution for solving the problem of both, cataract and keratoconus. Careful intraoperative manipulation, with reduced parameters should minimise the risk of postoperative corneal decompensation. Although IOL power calculation in these patients is complex and sometimes unpredictable, SRKT- II formula is suggested as most accurate for patients with cataract and keratoconus (15).

In order to achieve accurate IOL calculation regardless of which formula is used, it is essential to precisely and exactly determine keratometry and axial length readings. When compared with IOL master, Pentacam and an auto keratometer, manual keratometry gives most accurate results in evaluation of preexisting corneal astigmatism in cataract surgery with toric IOL implantation. (16). In this case, topography and manual keratometry gave similar results in determination of keratometry and astigmatism axis alignment, while automatic keratometry revealed a slightly different result, similar to previous reports (6, 10, 16). Using the actual K values with a target of low myopia is a suitable option for spherical IOL selection for eyes with a mean K of ≤55 (10), but in patients with posterior keratoconus, IOL power calculation from conventional keratometry may be inaccurate (17). When determining the axial length, manifest visual axis should be perfectly aligned and special attention should be given to ACD measurement, because of its direct influence on the reduction of the cylinder IOL power in the corneal plane (13). First IOL-s used for correction of astigmatism in keratoconus were phakic IOL-s, but only for refractive purposes (3). Only few reports in literature concern the use of toric posterior chamber IOL-s in keratoconus patients (4–10). Development IOL-s with higher cylinder power has made possible correction of full amount of corneal astigmatism (6–9). Cataract surgery in eyes with keratoconus can result with good postoperative visual acuity and low levels of postoperative astigmatism (6–8). To our knowing this is the first case of white cataract and keratoconus treated with toric IOL, without refractometry data, based only on topographic and biometry data. Careful patient selection and detailed preoperative assessment with special emphasis on corneal stability is crucial part of operative strategy in patients with cataract and keratoconus (4–10).

4. CONCLUSION

Cataract extraction with toric IOL implantation can be used to correct irregular astigmatism and significantly improve visual acuity in patients with stable keratoconus and cataract.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: NONE DECLARED.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vazirani J, Basu S. Keratoconus: current perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol. 2013;7:2019–2030. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S50119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rabinowitz YS. Keratoconus. Surv Ophthalmol. 1998;42:297–319. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(97)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Budo C, Bartels MC, van Rij G. Implantation of Artisan toric phakic intraocular lenses for the correction of astigmatism and spherical errors in patients with keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 2005;21:218–222. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20050501-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauder G, Jonas JB. Treatment of keratoconus by toric foldable intraocular lenses. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2003;13:577–579. doi: 10.1177/112067210301300612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Navas A, Suárez R. One-year follow-up of toric intraocular lens implantation in forme fruste keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:2024–2027. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2009.05.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Visser N, Gast ST, Bauer NJ, Nuijts RM. Cataract surgery with toric intraocular lens implantation in keratoconus: a case report. Cornea. 2011;30:720–723. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31820009d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaimes M, Xacur-García F, Alvarez-Melloni D, Graue-Hernández EO, Ramirez-Luquín T, Navas A. Refractive lens exchange with toric intraocular lenses in keratoconus. J Refract Surg. 2011;27:658–664. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20110531-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nanavaty MA, Lake DB, Daya SM. Outcomes of pseudophakic toric intraocular lens implantation in Keratoconic eyes with cataract. J Refract Surg. 2012;28:884–889. doi: 10.3928/1081597X-20121106-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parikakis EA, Chatziralli IP, Peponis VG, David G, Chalkiadakis S, Mitropoulos PG. Toric intraocular lens implantation for correction of astigmatism in cataract patients with corneal ectasia. Case Rep Ophthalmol. 2013;4:219–228. doi: 10.1159/000356532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alió JL, Peña-García P, Abdulla Guliyeva F, Soria FA, Zein G, Abu-Mustafa SK. MICS with toric intraocular lenses in keratoconus: outcomes and predictability analysis of postoperative refraction. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jan 3; doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-303765. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sedghipour MR, Sadigh AL, Motlagh BF. Revisiting corneal topography for the diagnosis of keratoconus: use of Rabinowitz's KISA% index. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:181–184. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S24219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Musanovic Z, Jusufovic V, Halibasica M, Zvornicanin J. Corneal astigmatism after micro-incision cataract operation. Med Arh. 2012;66:125–128. doi: 10.5455/medarh.2012.66.125-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Savini G, Hoffer KJ, Carbonelli M, Ducoli P, Barboni P. Influence of axial length and corneal power on the astigmatic power of toric intraocular lenses. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2013;39:1900–1903. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2013.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jurkunas U, Azar DT. Potential complications of ocular surgery in patients with coexistent keratoconus and Fuchs’ endothelial dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2187–2197. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thebpatiphat N, Hammersmith KM, Rapuano CJ, Ayres BD, Cohen EJ. Cataract surgery in keratoconus. Eye Contact Lens. 2007;33:244–246. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e318030c96d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chang M, Kang SY, Kim HM. Which keratometer is most reliable for correcting astigmatism with toric intraocular lenses? Korean J Ophthalmol. 2012;26:10–14. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2012.26.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park do Y, Lim DH, Chung TY, Chung ES. Intraocular lens power calculations in a patient with posterior keratoconus. Cornea. 2013;32:708–711. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3182797900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]