Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the impacts of vitamin D and parathyroid hormone (PTH) on longitudinal changes in arterial stiffness.

Approach and Results

Distensibility coefficient (DC) and Young’s elastic modulus (YEM) of the right common carotid artery were evaluated at baseline and after a mean (standard deviation) of 9.4 (0.5) years in 2,580 MESA participants. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations were evaluated using multivariable linear regression and analysis of covariance. At baseline, participants were 60.1 (9.4) years old (54% female; 26% Black, 20% Hispanic, 14% Chinese). Mean annualized 25(OH)D was <20 ng/dL in 816 and PTH was >65 pg/dL in 285 participants. In cross-sectional analyses, low 25(OH)D (<20 ng/ml) was not associated with stiffer arteries after adjustment for cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors (p>0.4). PTH >65 pg/ml was associated with stiffer arteries after adjustment for CVD risk factors, other than systolic blood pressure (SBP) (DC: β=−2.4×10−4 mmHg−1, p=0.003; YEM: β=166 mmHg, p=0.01), but after adjustment for SBP, these associations no longer were statistically significant. Longitudinal arterial stiffening was associated with older age (p<0.0001), higher SBP (p<0.008), and use of antihypertensive medications (p<0.006), but not with 25(OH)D or PTH (p>0.1).

Conclusions

Carotid arterial stiffness is not associated with low 25(OH)D concentrations. Cross-sectional associations between arterial stiffness and high PTH were attenuated by SBP. After nearly a decade of follow-up, neither baseline PTH nor 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with progression of carotid arterial stiffness.

Keywords: Arterial stiffness, Cardiovascular disease, Carotid arteries, Parathyroid hormone, Vitamin D, Young’s elastic modulus

Introduction

Vitamin D deficiency and hyperparathyroidism are associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk.1–9 Low circulating concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) and elevated parathyroid hormone (PTH) have been linked to hypertension, insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and death.1,7–14

Increased arterial stiffness is associated with aging, fragmentation of elastin fibers, and a decrease in the elastin to collagen ratio in arterial walls.15 This process may underlie the development of hypertension, CVD, cerebral dysfunction, and stroke16–20 as a rigid arterial tree is less able to accommodate the large pulsatile output from the heart. Increased vascular stiffness accelerates atherogenesis and is associated with an increase in cardiac morbidity and mortality.21 Vitamin D and PTH are closely linked and may affect vascular smooth muscle tone through the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis22 and may promote vascular endothelial growth factor.23 Additionally, lymphocyte and monocyte/phagocyte differentiation are modulated by vitamin D, thereby affecting the release of inflammatory cytokines that promote arterial plaque formation.24 Since heightened vascular smooth muscle tone, endothelial dysfunction, and plaque formation are directly linked to hypertension, coronary artery disease and stroke. Increased vascular stiffness is a plausible mechanism through which 25(OH)D and PTH may affect CVD risk.2,16,17,21,25,26

Structural and functional alterations in the arterial bed, such as circumferential widening of large arteries and wall thickening lead to changes in carotid artery distensibility and elasticity, measured with distensibility coefficient (DC) and Young’s elastic modulus (YEM) respectively. These are validated, non-invasive measures of arterial function, that characterize arterial stiffness15,27 and can identify individuals at increased CVD risk.21 Both measure the ability of an artery to expand and contract with each cardiac pulsation; however, the major difference between these stiffness parameters is that YEM accounts for carotid artery wall thickness in an attempt to separate whether arterial stiffening is solely related to pressure differences or intrinsic changes in the arterial wall.15,18,27

A limited number of studies have evaluated the associations of elevated PTH and low 25(OH)D with increased arterial stiffness; however, these studies are limited by their small sample size and their cross-sectional design.2,28–30 The aim of this study was to explore the relationship between markers of bone-mineral metabolism and changes in arterial stiffness in an ethnically diverse cohort without clinically evident CVD.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Participants were a mean (standard deviation) of 60.1 (9.4) years old, 54% were female, 39.5% were White, 25.5% were Black, 20.5% were Hispanic, and 14.5% were Chinese. The mean annualized 25(OH)D was 26.3 (11.5) ng/ml, and was less than 20 ng/dL in 816 (30%) and 20–30 ng/ml in 973 (36%) participants. The mean PTH was 43.5 (18.8) pg/dL and was greater than 65 pg/dL in 285 (11%) participants. 86% of subjects graduated from high school and 44% earned <$40000. The average physical activity score was 1665 MET-min/wk. At baseline, the mean distensibility coefficient (DC) was 3.1 (1.3) × 10−3 mmHg−1 and the mean Young’s elastic modulus (YEM) was 1591 (938) mmHg.

Table 1.

Baseline Participant Characteristics

| All Subjects |

Annualized 25-OH Vitamin D (ng/ml) |

Parathyroid hormone (pg/ml) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20.0 | 20.0–29.9 | ≥30.0 | Tertile 1 <32.8 |

Tertile 2 32.8–43.7 |

Tertile 3 43.8–65.0 |

>65.0 | ||

| Number of Subjects | 2,707 | 816 | 973 | 918 | 806 | 808 | 808 | 285 |

| Age (years) | 60.1 (9.4) | 58.6 (9.2) | 60.3 (9.4) | 61.3 (9.3) | 58.8 (9.2) | 59.6 (9.5) | 61.3 (9.3) | 61.9 (9.2) |

| Female sex (%) | 1449 (53.5) | 459 (56.3) | 481 (49.4) | 509 (55.5) | 429 (53.2) | 415 (51.4) | 429 (53.1) | 176 (61.8) |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||||

| White | 1070 (39.5) | 145 (17.8) | 388 (39.9) | 537 (58.5) | 395 (49.0) | 328 (40.6) | 276 (34.2) | 71 (24.9) |

| Black | 691 (25.5) | 406 (49.8) | 194 (19.9) | 91 (9.9) | 127 (15.8) | 189 (23.4) | 259 (32.1) | 116 (40.7) |

| Chinese | 392 (14.5) | 93 (11.4) | 176 (18.1) | 123 (13.4) | 155 (19.2) | 138 (17.1) | 86 (10.6) | 13 (4.6) |

| Hispanic | 554 (20.5) | 172 (21.1) | 215 (22.1) | 167 (18.2) | 129 (16.0) | 153 (18.9) | 187 (23.1) | 85 (29.8) |

| Blood pressure parameters (mmHg) | ||||||||

| SBP | 123.7 (20.1) | 125.8 (20.9) | 123.5 (20.0) | 122.0 (19.4) | 119.6 (19.0) | 121.7 (18.9) | 127.0 (20.5) | 131.3 (22.0) |

| DBP | 71.7 (10.1) | 73.1 (10.2) | 71.7 (10.0) | 70.5 (9.9) | 70.6 (9.6) | 71.3 (10.0) | 72.7 (10.2) | 73.3 (10.8) |

| Hypertension (%) | 1160 (42.9) | 376 (46.1) | 426 (43.8) | 358 (39.0) | 277 (34.4) | 323 (40.0) | 398 (49.3) | 162 (56.8) |

| HTN meds (%) | 896 (33.1) | 295 (36.2) | 330 (33.9) | 271 (29.5) | 212 (26.3) | 258 (31.9) | 304 (37.7) | 122 (42.8) |

| Diabetes mellitus status (%) | ||||||||

| IFG | 329 (12.2) | 120 (14.7) | 122 (12.6) | 87 (9.5) | 86 (10.7) | 95 (11.8) | 109 (13.5) | 39 (13.7) |

| Untreated | 43 (1.6) | 14 (1.7) | 25 (2.6) | 4 (0.4) | 12 (1.5) | 8 (1.0) | 18 (2.2) | 5 (1.8) |

| Treated | 200 (7.4) | 76 (9.3) | 83 (8.5) | 41 (4.5) | 68 (8.5) | 53 (6.6) | 54 (6.7) | 25 (8.8) |

| Lipid Levels (mg/dL) | ||||||||

| Total cholesterol | 194.1 (34.8) | 193.4 (36.6) | 192.8 (34.3) | 196.0 (33.6) | 195.1 (34.9) | 193.1 (34.7) | 195.2 (34.4) | 190.5 (35.7) |

| LDL-C | 117.1 (30.4) | 118.7 (32.5) | 116.5 (29.9) | 116.3 (29.1) | 117.3 (29.3) | 116.8 (30.8) | 118.3 (30.5) | 114.1 (32.4) |

| HDL-C | 51.6 (15.3) | 50.3 (14.7) | 50.1 (14.7) | 54.3 (16.0) | 51.8 (14.6) | 50.8 (15.0) | 51.7 (15.9) | 52.8 (16.1) |

| Triglycerides | 127.7 (81.2) | 122.3 (88.9) | 132.0 (78.0) | 128.1 (77.2) | 130.1 (78.7) | 128.3 (90.2) | 128.6 (79.7) | 117.1 (63.3) |

| Lipid-lowering meds (%) | 421 (15.6) | 109 (13.4) | 157 (16.1) | 155 (16.9) | 112 (13.9) | 118 (14.6) | 135 (16.7) | 56 (19.7) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.8 (5.0) | 29.2 (5.3) | 27.7 (4.8) | 26.5 (4.4) | 26.5 (4.5) | 27.6 (4.8) | 28.5 (5.0) | 29.7 (5.7) |

| Waist (cm) | 96.4 (13.7) | 99.4 (14.0) | 96.7 (13.7) | 93.3 (12.6) | 93.0 (12.9) | 95.8 (13.4) | 98.5 (13.1) | 101.5 (15.4) |

| Smoking Status (%) | ||||||||

| Former | 965 (35.7) | 283 (34.7) | 343 (35.3) | 339 (36.9) | 289 (35.9) | 280 (34.7) | 295 (36.5) | 101 (35.4) |

| Current | 312 (11.5) | 121 (14.9) | 105 (10.8) | 86 (9.4) | 103 (12.8) | 100 (12.4) | 84 (10.4) | 25 (8.8) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.9 (0.2) | 1.0 (0.3) |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.7 (0.4) | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.7 (0.4) | 9.6 (0.4) | 9.6 (0.4) |

| Phosphorous (mg/dL) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.5) | 3.7 (0.5) | 3.6 (0.5) | 3.5 (0.5) |

| CRP (mg/L) | 3.3 (4.9) | 3.8 (4.8) | 3.1 (4.9) | 3.1 (5.0) | 2.7 (4.0) | 3.3 (5.0) | 3.6 (4.7) | 4.3 (6.9) |

| 25(OH)D (ng/mL) | 26.3 (11.5) | 14.3 (3.8) | 25.0 (2.9) | 38.4 (9.7) | 30.2 (11.1) | 27.5 (11.8) | 23.6 (10.6) | 19.8 (9.4) |

| Parathyroid hormone (pg/mL) | 43.5 (18.8) | 51.4 (22.7) | 42.7 (16.7) | 37.2 (14.0) | 26.1 (4.8) | 38.0 (3.3) | 52.6 (5.9) | 82.2 (22.2) |

| Carotid wall thickness (cm) | 0.148 (0.031) | 0.150 (0.032) | 0.148 (0.031) | 0.147 (0.030) | 0.142 (0.029) | 0.147 (0.030) | 0.153 (0.033) | 0.153 (0.032) |

| PSI Diameter (cm) | 0.628 (0.075) | 0.630 (0.075) | 0.631 (0.074) | 0.623 (0.075) | 0.620 (0.072) | 0.628 (0.074) | 0.633 (0.074) | 0.636 (0.081) |

| EDI Diameter (cm) | 0.582 (0.071) | 0.584 (0.071) | 0.584 (0.070) | 0.576 (0.071) | 0.573 (0.068) | 0.582 (0.070) | 0.586 (0.071) | 0.591 (0.076) |

| YEM (mmHg) | 1591 (938) | 1652 (1011) | 1599 (904) | 1528 (902) | 1493 (799) | 1574 (915) | 1626 (1044) | 1815 (1006) |

| DC (10−3 mmHg−1) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.2) | 3.3 (1.3) | 3.2 (1.3) | 3.0 (1.2) | 2.7 (1.1) |

NA = not applicable, SBP = Systolic blood pressure, DBP = Diastolic blood pressure, HTN = hypertension, meds = medication, IFG = Impaired fasting glucose, LDL-C = low density lipoprotein cholesterol, HDL-C = high density lipoprotein cholesterol, BMI = Body mass index, CRP= C-reactive Protein, 25(OH)D = serum 25-hyroxyvitamin D, YEM = Young’s elastic modulus, DC = Distensibility coefficient

All values are mean (standard deviation) unless noted otherwise.

Cross-Sectional Associations with Arterial Stiffness Measures

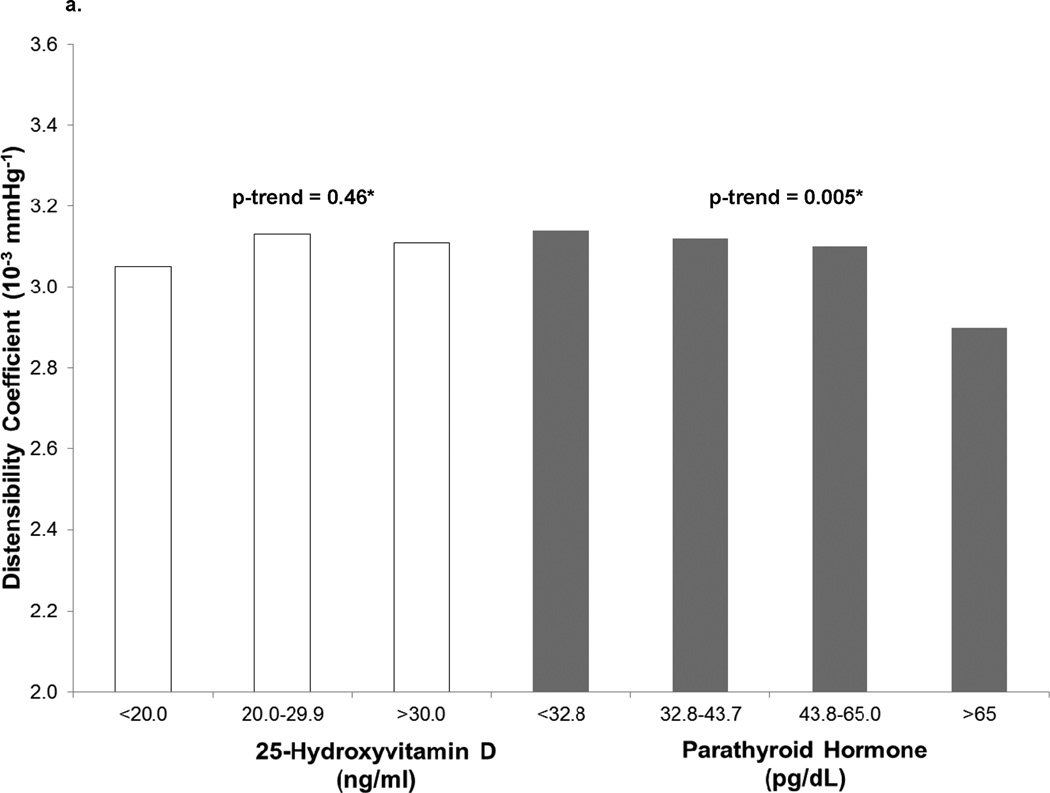

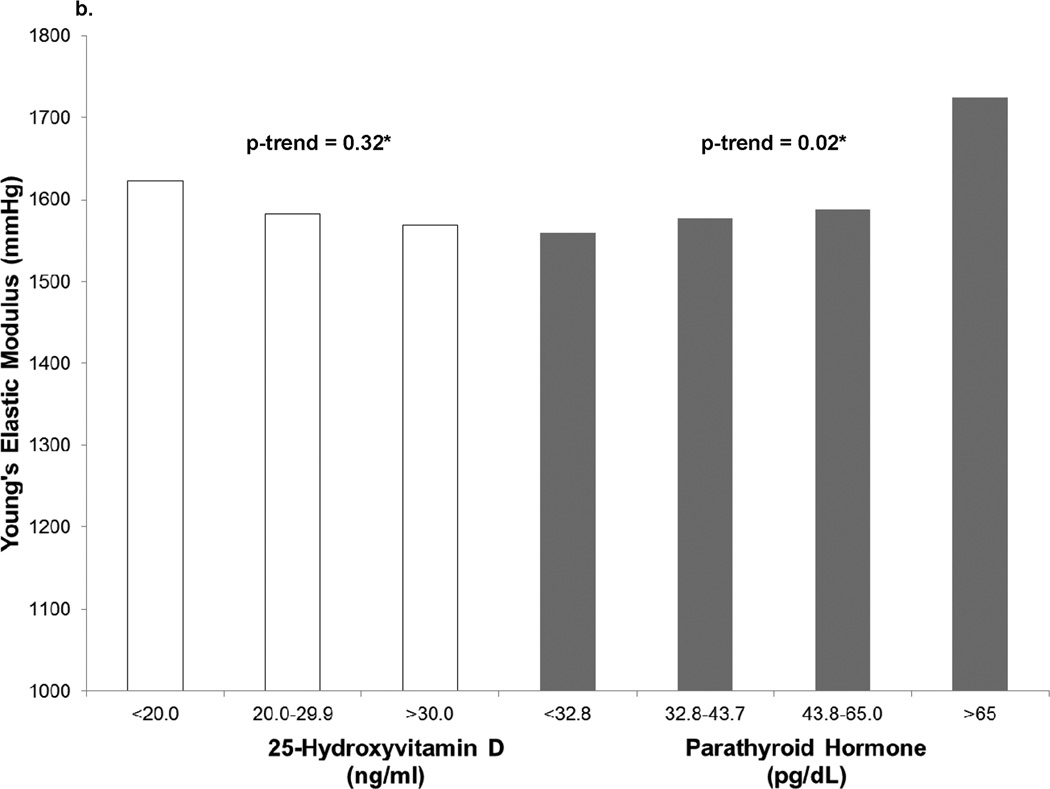

In cross-sectional analyses, continuous 25(OH)D was not associated with stiffness parameters before or after adjustment for CVD risk factors (p>0.1) (Table 2). When grouped by category of 25(OH)D concentrations, no significant trend toward increasing stiffness with lower 25(OH)D was observed after adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors (p>0.3) (Figure 1). The strongest association with increased stiffness at exam 1 was seen in participants with 25(OH)D concentrations <20 ng/ml (lower DC, β=−1.6×10−4 mmHg−1, p=0.01; higher YEM, β=107.2 mmHg, p=0.03); however, these associations disappeared after adjustment for traditional CVD risk factors (p>0.4). As a continuous variable, 25(OH)D concentration was not associated with arterial stiffness (DC, β=−2.4 ×10−7 mmHg−1, p=0.91; YEM, β=0.2 mmHg, p=0.92 (Table 2, cross-sectional model 3).

Table 2.

Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Associations of Serum 25(OH)D Concentrations and Distensibility Coefficient or Young’s Elastic Modulus

| Cross-sectional analyses | Longitudinal analyses* | |||||||||

|

Baseline Distensibility Coefficient (mmHg−1 ×10−4) (95% Confidence Interval) |

Change in Distensibility Coefficient (mmHg−1 ×10−4)** (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||||||

|

25(OH)D (ng/ml) |

n | Beta Parameter | N | Beta Parameter | ||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3b | Model 4b | Model 1c | Model 2c | Model 3d | Model 4d | |||

| ≥30.0 | 918 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | 872 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| 20.0–29.9 | 973 | −0.5 (−1.5, 0.6) | 0.1 (−1.0, 1.1) | 0.2 (−0.8, 1.3) | 0.3 (−0.7, 1.3) | 935 | −0.1 (−1.0, 0.8) | 0.1 (−0.8, 1.0) | 0.2 (−0.7, 1.1) | 0.2 (−0.7, 1.1) |

| <20 | 816 | −1.6‡ (−2.8, −0.4) | −0.7 (−1.9, 0.5) | −0.6 (−1.8, 0.6) | −0.3 (−1.5, 0.8) | 773 | 0.3 (−0.7, 1.3) | 0.5 (−0.5, 1.6) | 0.6 (−0.5, 1.6) | 0.6 (−0.4, 1.6) |

| P value† | - | 0.01 | 0.33 | 0.46 | 0.69 | - | 0.66 | 0.35 | 0.30 | 0.28 |

|

Baseline Young’s Elastic Modulus (mmHg) (95% Confidence Interval) |

Change in Young’s Elastic Modulus (mmHg)** (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||||||

|

25(OH)D (ng/ml) |

n | Beta Parameter | N | Beta Parameter | ||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3b | Model 4b | Model 1c | Model 2c | Model 3d | Model 4d | |||

| ≥30.0 | 918 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | 872 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| 20.0–29.9 | 973 | 50.2 (−34.1, 134.6) | 24.0 (−60.7, 108.7) | 13.1 (−72.0, 98.2) | 12.3 (−71.8, 96.3) | 935 | −75.6 (−188.3, 37.2) | −92.7 (−206.4, 21.1) | −91.0 (−205.4, 23.4) | −91.2 (−205.5, 23.2) |

| <20 | 816 | 107.2+ (11.0, 203.3) | 59.5 (−38.5, 157.5) | 53.5 (−45.1, 152.2) | 42.2 (−55.1, 139.6) | 773 | −87.5 (−216.1, 41.2) | −109.5 (−241.1, 22.1) | −100.3 (−232.6, 32.1) | −102.2 (−234.6, 30.1) |

| P-trend | - | 0.03 | 0.24 | 0.32 | 0.42 | - | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.10 |

p<0.01;

p<0.05;

Longitudinal analyses shown with adjustment for baseline stiffness measures;

Between the two carotid ultrasounds (9.4y)

Model 1: adjusted for age, sex, race, study field center, education, and income.

Model 2: Model 1 plus physical activity, waist circumference, smoking status, and BMI.

Model 3: Model 2 plus diabetes mellitus status, antihypertensive medication use, log[CRP], total cholesterol, HDL-C, lipid lowering therapy, and creatinine.

Model 4: Model 3 plus SBP.

Abbreviations as in previous Table

67 participants missing data on covariates;

83 participants missing data on covariates;

62 participants missing data on covariates;

77 participants missing data on covariates

Figure 1.

a. Baseline Distensibility Coefficient by 25-hydroxyvitamin D and Parathyroid Hormone Concentrations

*Median p-trends fully adjusted as in Model 3.

b. Baseline Young’s Elastic Modulus by 25-hydroxyvitamin D and Parathyroid Hormone Concentrations

*Median p-trends fully adjusted as in Model 3.

At baseline, higher PTH concentrations were associated with greater stiffness demonstrated by lower DC (β=−2.5×10−6 mmHg−1, p=0.04) and higher YEM (β=1.98 mmHg, p=0.06, Figure 1). This relationship appeared to be non-linear, with overtly elevated PTH concentrations (≥65 pg/mL) being most strongly associated with differences in DC and YEM. Adjusting for CVD risk factors other than blood pressure, PTH >65 pg/ml was associated with lower DC (β=−2.4×10−4 mmHg−1, p=0.003) and higher YEM (β=166 mmHg, p=0.01) (Table 3). However, these associations no longer were statistically significant when baseline systolic blood pressure (SBP) was included in the model (DC: β=−1.4×10−4 mmHg−1 p=0.08; YEM: β=118 mmHg p=0.07).

Table 3.

Cross-sectional and Longitudinal Associations Between Parathyroid Hormone and Distensibility Coefficient or Young’s Elastic Modulus

| Cross-sectional analyses | Longitudinal analyses* | |||||||||

|

Baseline Distensibility Coefficient (mmHg−1 ×10−4) (95% Confidence Interval) |

Change in Distensibility Coefficient (mmHg−1 ×10−4)** (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||||||

|

PTH (pg/mL) |

n | Beta Parameter | n | Beta Parameter | ||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3b | Model 4b | Model 1c | Model 2c | Model 3d | Model 4d | |||

| <32.8 | 806 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | 765 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| 32.8–43.7 | 808 | −0.6 (−1.7, 0.5) | −0.2 (−1.3, 1.0) | −0.2 (−1.3, 0.9) | −0.2 (−1.3, 0.9) | 772 | 1.1+ (0.1, 2.0) | 1.2+ (0.2, 2.1) | 1.0 (0.0, 1.9) | 1.0 (0.0, 1.9) |

| 43.8–65.0 | 808 | −1.2+ (−2.3, −0.0) | −0.4 (−1.6, 0.7) | −0.5 (−1.6, 0.7) | 0.0 (−1.1, 1.1) | 777 | 0.4 (−0.6, 1.4) | 0.6 (−0.4, 1.5) | 0.5 (−0.5, 1.4) | 0.5 (−0.4, 1.5) |

| >65 | 285 | −3.4‡ (−5.0, −1.8) | −2.2‡ (−3.8, −0.5) | −2.4‡ (−4.0, −0.8) | −1.4 (−3.0, 0.1) | 266 | −0.3 (−1.6, 1.1) | 0.0 (−1.4, 1.4) | −0.2 (−1.6, 1.2) | −0.1 (−1.4, 1.3) |

| P value† | - | <0.001 | 0.01 | 0.005 | 0.16 | - | 0.61 | 0.93 | 0.73 | 0.91 |

|

Baseline Young’s Elastic Modulus (mmHg) (95% Confidence Interval) |

Change in Young’s Elastic Modulus (mmHg)** (95% Confidence Interval) |

|||||||||

| n | Beta Parameter | n | Beta Parameter | |||||||

| Model 1a | Model 2a | Model 3b | Model 4b | Model 1c | Model 2c | Model 3d | Model 4d | |||

| <32.8 | 806 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. | 765 | ref. | ref. | ref. | ref. |

| 32.8–43.7 | 808 | 39.2 (−50.9, 129.4) | 20.1 (−70.0, 110.1) | 17.9 (−72.3, 108.1) | 18.3 (−70.8, 107.3) | 772 | −63.5 (−184.3, 57.2) | −67.9 (−189.0, 53.2) | −56.8 −178.1, 64.5) | −56.5 (−177.8, 64.8) |

| 43.8–65.0 | 808 | 63.4 (−28.7, 155.5) | 28.4 (−64.2, 120.9) | 28.6 (−64.2, 121.5) | 5.6 (−86.2, 97.5) | 777 | −59.0 (−182.1. 64.2) | −73.2 (−197.6, 51.2) | −57.5 (−182.2, 67.3) | −62.7 (−187.7, 62.2) |

| >65 | 285 | 217.0‡ (88.1, 345.9) | 159.0+ (28.8, 289.2) | 166.2+ (35.6, 296.7) | 117.6 (−11.8, 247.0) | 266 | 110.3 (−63.9, 284.5) | 88.1 (−88.3, 264.6) | 80.5 (−96.5, 257.5) | 70.9 (−106.5, 248.4) |

| P-trend | - | 0.002 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.14 | - | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.64 |

p<0.01;

p<0.05;

Longitudinal analyses shown with adjustment for baseline stiffness measures;

Between the two carotid ultrasounds (9.4y)

67 participants missing data on covariates;

83 participants missing data on covariates;

62 participants missing data on covariates;

77 participants missing data on covariates

Models and abbreviations as in Table 2.

Within race/ethnicity groups, there were no significant associations between baseline 25(OH)D and YEM or DC (all p>0.05). The associations of PTH with DC and YEM appeared strongest for Hispanic participants (DC: β=−3.6×10−4 mmHg−1, p=0.02; YEM: β=275 mmHg, p=0.04), but the p-values for the interaction of race/ethnicity with PTH were not statistically significant for DC (p=0.15) or YEM (p=0.08).

Longitudinal Associations with Arterial Stiffness Measurements

DC decreased from 3.1 (1.3) × 10−3 mmHg−1 at exam 1 to 2.7 (1.2) × 10−3 mmHg−1 at exam 5 and YEM increased from 1591 (938) mmHg at exam 1 to 1754 (1340) mmHg at exam 5, both indicating progression of arterial stiffness over the follow up period. Longitudinal changes in DC and YEM were associated with older age (DC: β=−2.0×10−5 mmHg−1, per year, p<0.0001; YEM: β=13.4 mmHg, per year, p<0.0001) and higher systolic blood pressure (DC: β=−2.9×10−6 mmHg1, p=0.007) and use of antihypertensive medication (YEM: β=157.4 mmHg, p=0.006). No associations or even trends were observed between baseline 25(OH)D or PTH and carotid stiffness (all p>0.3) with or without adjustment for baseline DC and YEM. Additionally, those with baseline PTH >65 pg/ml or 25(OH)D <20 also were not associated with a significant change in DC or change in YEM after nearly 10 years of follow up (Table 2 and Table 3) compared to the reference groups.

Within race/ethnicity groups, no significant associations between 25(OH)D and PTH with longitudinal changes in YEM or DC were observed (all p>0.05) and the p-values for the interaction of race/ethnicity with PTH were not statistically significant for changes in DC (p=0.15) or YEM (p=0.96)

Discussion

In the current analysis, we observed a cross-sectional association of higher PTH concentrations with increased arterial stiffness that was independent of CVD risk factors except baseline SBP. No associations were present for 25-OHD. After nearly a decade of aging, neither baseline PTH nor 25-OHD concentrations were associated with changes in arterial stiffening.

Potentially deleterious effects of vitamin D deficiency on CVD risk have been described and have even led some clinicians to promote vitamin D supplementation for CVD risk reduction.1,5–7,31 A relationship between low vitamin D concentrations and increased arterial stiffness has been described in cross-sectional observational studies;2,25,29 however, the effects of vitamin D status on longitudinal changes in arterial stiffness are less clear. Our results are in accordance with small randomized controlled trials of vitamin D supplementation which failed to demonstrate improvements in arterial stiffness with vitamin D supplementation,28,32 though the longest of these trials only followed subjects for 3 years.28 Relationships between vitamin D concentrations and CVD endpoints have been mixed. For example, low vitamin D concentrations have been associated with increased risk of incident coronary heart disease33 and presence of coronary artery calcium,34,35 but not with congestive heart failure or carotid intima-media thickness.36 Associations between low circulating vitamin D concentration and CVD risk may also be partly confounded by CVD risk factors such as obesity and inactivity.37 The only large, long-term randomized controlled trial of vitamin D supplementation showed no change in CVD events over a 7 year period.38

High PTH concentrations have been associated with poor CVD outcomes9 in observational studies.29,30 In prior cross-sectional analysis among MESA participants, higher PTH concentrations were associated with increased blood pressure, higher central aortic pressure, and lower large artery elasticity.39 PTH levels seem to be more strongly associated with congestive heart failure events than coronary heart disease events.9 The results of the present study agree with previously reported studies describing cross-sectional associations between elevated PTH and increased carotid stiffness measures; however, the results were blunted when SBP was included in the model. This suggests that the cross-sectional associations between arterial stiffness and PTH may be mediated though blood pressure. It also is possible that the baseline SBP is more collinear with DC and YEM since pulse pressure, which takes blood pressure into account, is a part of the formulae used to calculate these outcome measures.

It may be expected that higher PTH concentrations at baseline would lead to more rapid progression of arterial stiffness over a decade of aging; however, we did not observe a longitudinal association between baseline PTH concentrations and progressive arterial stiffening. Since those with the highest PTH levels also were found to have stiffer arteries at baseline, acceleration of stiffness over time may be blunted since there could be less physiologic “room” for progression of the carotid stiffness parameters (“ceiling” effect). However, when baseline stiffness parameters were included in the models to attempt to account for this discrepancy, still, no associations or even consistent trends were observed. Although PTH and vitamin D were not longitudinally associated with changes in YEM and DC, acceleration of stiffness parameters were observed as expected with traditional CVD risk factors, such as advancing age and hypertension.40 Alternatively, although 25-(OH)D has a relatively long circulating half-life (approximately 3 weeks) and is considered a good biomarker, a single measurement may not fully capture cumulative vitamin D exposure over a 10 year period, resulting in misclassification. Similarly for PTH, which comparatively has a much shorter half-life (2–4 minutes), making it even more subject to misclassification. A single measurement seems adequate for cross-sectional associations but is less useful over a decade of follow up.

Several limitations of the current study should be considered. First, we imaged the carotid arteries but measured brachial artery blood pressure. Brachial artery pressure is considered to be a surrogate for central aortic pressure, but may overestimate stiffness measurements since brachial measurements can overestimate central pressures, though the two measures are highly correlated, especially in older adults.41 Vitamin D and PTH status were defined by baseline concentrations and the absence of follow up levels of either hormone poses a challenge to the interpretation of the longitudinal analyses. This potentially is more likely to be an issue with the vitamin since supplementation is common in the general population and we did not have information regarding vitamin D supplementation during the follow up period. Also, the race/ethnicity subgroup analyses may be limited by small sample size. Since all participants had ultrasound studies at exams 1 and 5, there may be a survivorship bias. Participants who were followed to exam 5 were healthier and less likely to have a non-fatal CVD event than the complete MESA cohort which would likely result in a null bias

Conclusions

In cross-sectional analyses, we did not observe any independent associations between arterial stiffness measures and vitamin D status. Carotid arterial stiffness was associated with PTH concentrations >65 mg/dL, but the associations were attenuated by adjustment for SBP. In longitudinal analyses, advancing age and hypertension were associated with progression of arterial stiffness, but neither baseline PTH nor 25(OH)D were associated with changes in arterial stiffness measures after nearly a decade of follow-up. Elevated PTH is associated with carotid stiffness, but the causal and temporal interrelationships of PTH, blood pressure, and carotid stiffness are not entirely clear and warrant further study.

Supplementary Material

Significance.

Low vitamin D and high parathyroid hormone concentrations have been associated with heart disease and hypertension, but much less is known about their long-term effects on arterial stiffening, which has been linked to the development of heart failure, strokes, and heart attacks. In this study, carotid artery stiffness was associated with high parathyroid hormone levels, though this finding was attenuated by systolic blood pressure. Vitamin D concentration was not associated with baseline arterial stiffness. Neither baseline parathyroid hormone nor vitamin D concentrations were associated with changes in arterial stiffening over nearly a decade of follow up. These findings suggest that parathyroid hormone may impact the development of arterial stiffness, but the causal and temporal interrelationships of PTH, blood pressure, and carotid stiffness are not entirely clear and warrant further study.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the other investigators, the staff, and the participants of the MESA study for their valuable contributions. A full list of participating MESA investigators and institutions can be found at http://www.mesa-nhlbi.org.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by contracts HC95159-HC95169 and HL07936 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, grant ES015915 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, and grants RR024156 and RR025005 from the National Center for Research Resources. This publication was developed under Science to Achieve Results research assistance agreement RD831697 from the Environmental Protection Agency. It has not been formally reviewed by the Environmental Protection Agency. The views expressed in this document are solely those of the authors. The Environmental Protection Agency does not endorse any products or commercial services mentioned in this publication. Dr. Gepner was supported, in part, by a Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute to the University of Wisconsin-Madison Cardiovascular Research Center (T32HL07936).

Abbreviations

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- DC

distensibility coefficient

- PTH

parathyroid hormone

- SBP

systolic blood pressure

- YEM

Young’s elastic modulus

Footnotes

Disclosures

AD Gepner: None; LA Colangelo: None; M Blondon: None; CE Korcarz: None; IH de Boer: None; B Kestenbaum: None; DS Siscovick: None; JD Kaufman: None; K Liu: None; JH Stein: Wisconsin Alumni Research Foundation

References

- 1.Lavie CJ, Lee JH, Milani RV. Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease will it live up to its hype? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:1547–1556. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al Mheid I, Patel R, Murrow J, Morris A, Rahman A, Fike L, Kavtaradze N, Uphoff I, Hooper C, Tangpricha V, Alexander RW, Brigham K, Quyyumi AA. Vitamin d status is associated with arterial stiffness and vascular dysfunction in healthy humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:186–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1174–1180. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.11.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reddy VS, Good M, Howard PA, Vacek JL. Role of vitamin D in cardiovascular health. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:798–805. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.04.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, Ingelsson E, Lanier K, Benjamin EJ, D'Agostino RB, Wolf M, Vasan RS. Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2008;117:503–511. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.706127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JH, O'Keefe JH, Bell D, Hensrud DD, Holick MF. Vitamin D deficiency an important, common, and easily treatable cardiovascular risk factor? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:1949–1956. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson JL, May HT, Horne BD, Bair TL, Hall NL, Carlquist JF, Lappe DL, Muhlestein JB. Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:963–968. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Autier P, Gandini S. Vitamin D supplementation and total mortality: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1730–1737. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.16.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kestenbaum B, Katz R, de Boer I, Hoffnagle P, Sarnak MJ, Shlipak MG, Jenny NS, Siscovich DS. Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and cardiovascular events among older adults. JACC. 2011;58:1433–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brondum-Jacobsen P, Nordestgaard BG, Schnohr P, Benn M. 25-hydroxyvitamin D and symptomatic ischemic stroke: an original study and meta-analysis. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:38–47. doi: 10.1002/ana.23738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiu KC, Chu A, Go VL, Saad MF. Hypovitaminosis D is associated with insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:820–825. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.5.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford ES, Ajani UA, McGuire LC, Liu S. Concentrations of serum vitamin D and the metabolic syndrome among U.S. adults. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1228–1230. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forman JP, Giovannucci E, Holmes MD, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Tworoger SS, Willett WC, Curhan GC. Plasma 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of incident hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:1063–1069. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.087288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hagstrom E, Hellman P, Larsson TE, Ingelsson E, Berglund L, Sundstrom J, Melhus H, Held C, Lind L, Michaelsson K, Arnlov J. Plasma parathyroid hormone and the risk of cardiovascular mortality in the community. Circulation. 2009;119:2765–2771. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.808733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smulyan H, Asmar RG, Rudnicki A, London GM, Safar ME. Comparative effects of aging in men and women on the properties of the arterial tree. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:1374–1380. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Safar ME. Systolic hypertension in the elderly: arterial wall mechanical properties and the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. J Hypertens. 2005;23:673–681. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000163130.39149.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJ, Hofman A, van Popele NM, Bos ML, Schalekamp MA, Asmar R, Reneman RS, Hoeks AP, Breteler MM, Witteman JC. Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 2006;113:657–663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.555235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kass DA. Age-related changes in venticular-arterial coupling: pathophysiologic implications. Heart Fail Rev. 2002;7:51–62. doi: 10.1023/a:1013749806227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang EY, Chambless L, Sharrett AR, Virani SS, Liu X, Tang Z, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne CM, Nambi V. Carotid arterial wall characteristics are associated with incident ischemic stroke but not coronary heart disease in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Stroke. 2012;43:103–108. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeki AH, Newman AB, Simonsick E, Sink KM, Sutton TK, Watson N, Satterfield S, Harris T, Yaffe K. Pulse wave velocity and cognitive decline in elders: the Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Stroke. 2013;44:388–393. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.673533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glasser SP, Arnett DK, McVeigh GE, Finkelstein SM, Bank AJ, Morgan DJ, Cohn JN. Vascular compliance and cardiovascular disease: a risk factor or a marker? Am J Hypertens. 1997;10:1175–1189. doi: 10.1016/s0895-7061(97)00311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li YC, Qiao G, Uskokovic M, Xiang W, Zheng W, Kong J. Vitamin D: a negative endocrine regulator of the renin-angiotensin system and blood pressure. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;89–90:387–392. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raymond MA, Desormeaux A, Labelle A, Soulez M, Soulez G, Langelier Y, Pshezhetsky AV, Hebert MJ. Endothelial stress induces the release of vitamin D-binding protein, a novel growth factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;338:1374–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oh J, Weng S, Felton SK, Bhandare S, Riek A, Butler B, Proctor BM, Petty M, Chen Z, Schechtman KB, Bernal-Mizrachi L, Bernal-Mizrachi C. 1,25(OH)2 vitamin d inhibits foam cell formation and suppresses macrophage cholesterol uptake in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2009;120:687–698. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.856070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Giallauria F, Milaneschi Y, Tanaka T, Maggio M, Canepa M, Elango P, Vigorito C, Lakatta EG, Ferrucci L, Strait J. Arterial stiffness and vitamin D levels: the Baltimore longitudinal study of aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:3717–3723. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nambi V, Chambless L, Folsom AR, He M, Hu Y, Mosley T, Volcik K, Boerwinkle E, Ballantyne CM. Carotid intima-media thickness and presence or absence of plaque improves prediction of coronary heart disease risk: the ARIC (Atherosclerosis Risk In Communities) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:1600–1607. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoeks AP, Reneman RS. Biophysical principles of vascular diagnosis. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23:71–79. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870230203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braam LA, Hoeks AP, Brouns F, Hamulyak K, Gerichhausen MJ, Vermeer C. Beneficial effects of vitamins D and K on the elastic properties of the vessel wall in postmenopausal women: a follow-up study. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:373–380. doi: 10.1160/TH03-07-0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pirro M, Manfredelli MR, Helou RS, Scarponi AM, Schillaci G, Bagaglia F, Melis F, Mannarino E. Association of parathyroid hormone and 25-OH-vitamin D levels with arterial stiffness in postmenopausal women with vitamin D insufficiency. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2012;19:924–931. doi: 10.5551/jat.13128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schillaci G, Pucci G, Pirro M, Monacelli M, Scarponi AM, Manfredelli MR, Rondelli F, Avenia N, Mannarino E. Large-artery stiffness: a reversible marker of cardiovascular risk in primary hyperparathyroidism. Atherosclerosis. 2011;218:96–101. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Boer IH, Levin G, Robinson-Cohen C, Biggs ML, Hoofnagle AN, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum B. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and risk for major clinical disease events in a community-based population of older adults: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:627–634. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-156-9-201205010-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gepner AD, Ramamurthy R, Krueger DC, Korcarz CE, Binkley N, Stein JH. A prospective randomized controlled trial of the effects of vitamin D supplementation on cardiovascular disease risk. PLoS One. 2012;7:e36617. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson-Cohen C, Hoofnagle AN, Ix JH, Sachs MC, Tracy RP, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum BR, de Boer IH. Racial differences in the association of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration with coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2013;310:179–188. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.7228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watson KE, Abrolat ML, Malone LL, Hoeg JM, Doherty T, Detrano R, Demer LL. Active serum vitamin D levels are inversely correlated with coronary calcification. Circulation. 1997;96:1755–1760. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Boer IH, Kestenbaum B, Shoben AB, Michos ED, Sarnak MJ, Siscovick DS. 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels inversely associate with risk for developing coronary artery calcification. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:1805–1812. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008111157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blondon M, Sachs M, Hoofnagle AN, Ix JH, Michos ED, Korcarz C, Gepner AD, Siscovick DS, Kaufman JD, Stein JH, Kestenbaum B, de Boer IH. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D and Parathyroid Hormone Are Not Associated With Carotid Intima-Media Thickness or Plaque in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2013 doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.301781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beveridge LA, Witham MD. Vitamin D and the cardiovascular system. Osteoporos Int. 2013;24:2167–2180. doi: 10.1007/s00198-013-2281-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsia J, Heiss G, Ren H, Allison M, Dolan NC, Greenland P, Heckbert SR, Johnson KC, Manson JE, Sidney S, Trevisan M. Calcium/vitamin D supplementation and cardiovascular events. Circulation. 2007;115:846–854. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.673491. (Erratum in: Circulation. 2007 May 15:115(19):e466). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bosworth C, Sachs MC, Duprez D, Hoofnagle AN, Ix JH, Jacobs DR, Jr, Peralta CA, Siscovick DS, Kestenbaum B, de Boer IH. Parathyroid hormone and arterial dysfunction in the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2013;79:429–436. doi: 10.1111/cen.12163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gepner AD, Korcarz CE, Colangelo LA, Horn EK, Tattersall MC, Astor BC, Kaufman JD, Liu K, Stein JH. Longitudinal Effects of a Decade of Aging on Carotid Artery Stiffness: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Stroke. 2013 Nov 19; doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002649. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 24253542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilkinson IB, Franklin SS, Hall IR, Tyrrell S, Cockcroft JR. Pressure amplification explains why pulse pressure is unrelated to risk in young subjects. Hypertension. 2001;38:1461–1466. doi: 10.1161/hy1201.097723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.