Abstract

Background

Fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) is recommended for diagnosis and staging of NSCLC. Meta-analyses of FDG-PET diagnostic accuracy demonstrated sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 78%, respectively but were performed in select centers introducing potential bias. This study evaluates the accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose NSCLC and examines differences across enrolling sites in the national ACOSOG Z4031 trial.

Methods

959 eligible patients with clinical stage I (cT1-2N0M0) known or suspected NSCLC were enrolled between 2004 and 2006 in the Z4031 trial and 682 had a baseline FDG-PET. Final diagnosis was determined by pathological examination. FDG-PET avidity was categorized into four levels based on radiologist description or reported maximum standard uptake value (SUV). FDG-PET diagnostic accuracy was calculated for the entire cohort. Accuracy differences based on preoperative size and by enrolling site were examined.

Results

Preoperative FDG-PET results were available for 682 participants enrolled at 51 sites in 39 cities. Lung cancer prevalence was 83%. FDG-PET sensitivity was 82% (95% CI: 79–85) and specificity was 31% (95% CI: 23%–40%). Positive and negative predictive values were 85% and 26%, respectively. Accuracy improved with lesion size. Of 80 false positive scans, 69% were granulomas. False negative scans occurred in 101 patients with adenocarcinoma being the most frequent (64%) and eleven were ≤10mm. The sensitivity varied from 68% to 91% (p=0.03) and the specificity ranged from 15% to 44% (p=0.72) across cities with > 25 participants.

Conclusions

In a national surgical population with clinical stage I NSCLC, FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer performed poorly compared to published studies.

INTRODUCTION

The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) recently reported that a screening regimen of annual low dose computed tomography scans reduced lung cancer related mortality by 20% in a high risk population. The United States Preventive Services Task Force, physician societies and patient advocate groups have recommending lung cancer screening using low dose computed tomography (CT) scans for high risk populations(1–6). Although there was a reduction in lung cancer related mortality in the NLST, 96% of lung abnormalities found by CT were false positive findings(2). Other studies found similarly high rates of false positive results(7, 8). These false positive results required additional radiographic and procedural tests to achieve a diagnosis or rule out lung cancer. The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend using fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) scans to help diagnose pulmonary nodules larger than 8mm in size that do not exhibit significant benign characteristics and have a low to moderate risk for malignancy(1, 9). Meta-analysis of the diagnostic accuracy of FDG-PET reported 96% sensitivity and 78% specificity(10) but recent studies have questioned the generalizeabilty of these results to regions of the country with endemic fungal lung disease(11, 12).

The recently concluded American College of Surgeons Oncology Group Z4031 (ACOSOG) trial evaluated patients with known or suspected clinical stage I Non-small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). This trial obtained FDG-PET results providing a large national sample to determine the accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose early stage lung cancer in a population undergoing surgical resection. We conducted a secondary analysis of the ACOSOG trial to determine the diagnostic accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer in patients with known or suspected clinical stage I lung cancer being evaluated for surgery and examine whether the test’s accuracy varied between study sites.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Population

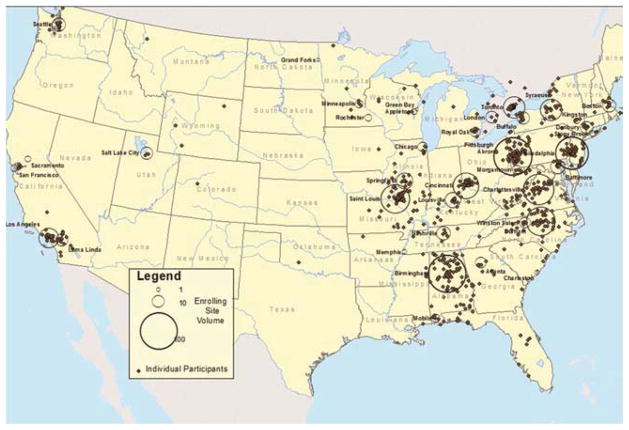

The primary objective of the ACOSOG Z4031 study “Use of Proteomic Analysis of Serum Samples for Detection of Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer” (5U10CA076001-11) was to determine prospectively whether a serum proteomic profile could predict the presence of primary NSCLC in patients with suspicious lung lesions who are candidates for lung resection. The study design was a prospective study of 1000 patients undergoing lung resection for clinically suspicious lung lesions. The ACOSOG trial was a national study that occurred across 23 states and Ontario, Canada in 51 hospitals located in 39 different cities (Figure 1). Patients were enrolled in the ACOSOG Z4031 trial from February 2004 to May 2006. Inclusion criteria were: 1) 18 years or older, 2) Clinically suspicious Stage I lung lesion, 3) CT scan < 60 days prior to the lung resection and no evidence of metastatic disease, 4) no untreated malignancies, 5) asymptomatic survival > 5 years if prior malignancy, 6) able to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included patients who had: 1) undergone previous lung resection within the preceding 30 days, 2) received prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy and 3) received a blood product transfusion of any kind within the past 60 days of the operative procedure.(13) The ACOSOG Z4031 prospective clinical trial contains data on 969 patients who met all the eligibility criteria. Pre-operative FDG-PET scans were not required for all participants and clinician report of the scan was included in addition to the most recent pre-operative CT scan as part of the study protocol. Both FDG-PET and combined FDG-PET/CT scans were conducted at the discretion of the physician. The type of FDG-PET scan (PET or PET/CT) was based on the institution availability. No original scans were available for review.

Figure 1.

Enrolling site location with size of circle corresponding to participation volume – 51 sites in 39 cities. Individual dots are participants by zip code at time of enrollment. Dots are overlapping for those with identical zip codes.

Data Collection

At time of enrollment age, gender, race, ethnicity, body mass index, date of operation, clinical stage, CT reports, FDG-PET reports, enrolling site and zip or postal code of patient residence were collected. Operative notes and pathological reports were collected along with 30 day mortality status, status at last follow-up, date of last follow-up, and cause of death if dead at last follow-up. Follow up for the study participants was 5 years. All data were stored and maintained by the ACOSOG data center. Additional data were abstracted from the study case report forms including clinical maximum lesion diameter according to CT or PET/CT immediately prior to surgery, smoking status, pack years, FDG-PET scan prior to operation, pathological result for benign disease, FDG-PET scan result and standard uptake value (SUV) when provided. Data was extracted from case report forms by trained medical reviewers. FDG-PET scan results were categorized based on the radiologist descriptor of avidity or maximum SUV. The two categories were not avid if the report contained not avid/not cancerous, low avidity/not likely cancerous or SUV < 2.5 when reported and avid if the report contained avid/likely cancerous, highly avid/cancerous or SUV ≥ 2.5. Pathological reports and operative notes were reviewed to determine etiology of benign disease and the specific cancer diagnosis. This secondary analysis of the ACOSOG Z4031 study was approved by the Vanderbilt IRB.

Analysis

Differences in the demographics between the participants with benign and malignant lesions were compared using a t-test for continuous variables (age and lesion size) and binomial proportions test for differences in proportions (gender, race and FDG-PET avidity). Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values were calculated for the study population who had FDG-PET scans. The FDG-PET accuracy to diagnose lung cancer equals true positives plus true negatives divided by the population tested and was calculated using the pathological diagnosis as the reference. The sensitivity and specificity was calculated separately for those cities with greater than 25 participants. Differences in the sensitivity and specificity between cities were estimated using the chi-square statistic. The accuracy of FDG-PET grouped by lesion size was compared with an analysis of variance for patients with FDG-PET scans.

RESULTS

Our current study had 682 participants which met the ACOSOG Z4031 trial eligibility criteria and had a preoperative FDG-PET scan (Table 1). Based on the pathology reports provided by the home institution, benign disease was found in 116 patients (17%) and cancer in 566 patients (83%). Microbiology results abstracted from pathological or operative reports resulted in only 11% of benign cases having an unknown diagnosis. Of the 116 benign cases, 75 (65%) were documented in the pathology report as being granulomatous and 30 (26%) of the granulomas had documented histoplasmosis etiology in the pathology report (Table 2). Patients with cancer were more likely to be older, non-Caucasian, and have larger lesions that were FDG-PET avid than patients with benign disease.

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of ACOSOG Z4031 patients with FDG-PET Scans (n=682)

| Characteristic | Cancer N=566 |

Benign N=116 |

p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | 253 (45) | 54 (47) | 0.71 |

| Caucasian (%) | 517 (91) | 113 (97) | 0.03 |

| Mean Age (Range) | 67 (31–90) | 61 (36–89) | <0.001 |

| Lesion Size mm (Range) | 26 (0.61) | 20 (0.95) | <0.001 |

| FDG-PET Avidb (%) | 465 (82) | 80 (69) | 0.002 |

Continuous variable statistics use t-test (Age and Lesion Size) and binomial proportions test for differences in proportions (Gender, Race and FDG-PET Avidity).

The categories of avidity and their corresponding SUV are: not avid if the report contained not avid/not cancerous, low avidity/not likely cancerous or SUV < 2.5 when reported) and avid if the report contained avid/likely cancerous, highly avid/cancerous or SUV ≥ 2.5.

Table 2.

Pathology of all participants with an FDG-PET scan

| Malignancy | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | 283 (50.0) |

| Squamous Cell | 157 (27.7) |

| Other NSCLC | 34 (6.0) |

| Carcinoid/Neuroendocrine | 29 (5.1) |

| Carcinoma in situ | 23 (4.1) |

| Large Cell | 16 (2.8) |

| Other Cancer* | 10 (1.7) |

| Small Cell | 7 (1.2) |

| Unknown | 7 (1.2) |

|

| |

| Benign | N (%) |

|

| |

| Granuloma** | 75 (64.7) |

| Benign Tumor | 17 (12.1) |

| Active Infectious disease*** | 14 (12.1) |

| Fibrosis | 5 (4.3) |

| Other | 5 (4.3) |

Includes lymphoma, melanoma, adenoid cystic neoplasm, mucoepidermoid, sarcoma, and other neoplasm.

Granuloma includes histoplasmosis, atypical mycobacteria, blastomycosis, cryptococcus, coccidiodomycosis, aspergillosis and nonspecific granulomas.

Infectious disease includes active Mycobacterium tuberculosis and active pneumonia

The overall accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer was 73% when compared to the pathologic diagnosis. The sensitivity and specificity was 82% and 31% and the positive and negative predictive values were 85% and 26%, respectively (Table 3). Of the 80 false positives, 69% of these were granulomas (Table 4). Of the 101 false negatives, 11 of them were </= 1cm, 62% of these lesions were adenocarcinoma, 11% squamous, 10% carcinoma in-situ and 9% neuroendocrine. The majority of patients with false positive FDG-PET scans had granulomas and the majority of false negative FDG-PET scan results had adenocarcinoma.

Table 3.

Accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose cancer among patients with clinical stage1 NSCLC

| FDG-PET | Cancera | Benign | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Avidb | 465 | 80 | PPVc 85% 95%CI: (82, 88) |

| Not-Avid | 101 | 36 | NPVd 26% 95%CI: (19, 35) |

|

|

|||

| Prevalence 83% 95%CI: (80, 86) | |||

| Sensitivity 82% 95%CI: (79, 85) | |||

| Specificity 31% 95%CI: (23, 40) | |||

Diagnosis was based upon pathological result of the surgically resected specimen.

FDG-PET avidity was defined by an SUV ≥ 2.5 or moderate or intense uptake.

PPV = positive predictive value

NPV = negative predictive value

Table 4.

Pathology of false negative and false positive lesions

| Malignant | FDG-PET Non-Avid False Negatives (%) * |

|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma | 62 (62) |

| Squamous Cell | 11 (11) |

| Carcinoma in situ | 11 (11) |

| Carcinoid/Neuroendocrine | 9 (9) |

| Other NSCLC | 4 (4) |

| Other Cancer | 1 (1) |

| Small Cell | 1 (1) |

| Unknown | 2 (2) |

|

| |

| Benign | FDG-PET Avid False Positives (%) |

|

| |

| Granuloma** | 55 (69) |

| Benign Tumor | 8 (10) |

| Active Infectious disease*** | 9 (11) |

| Fibrosis | 4 (5) |

| Other | 4 (5) |

11 of the false negatives were <1cm

Granuloma includes histoplasmosis, atypical mycobacteria, blastomycosis, cryptococcus, coccidiodomycosis, aspergillosis and nonspecific granulomas.

Infectious disease includes active Mycobacterium tuberculosis and active pneumonia

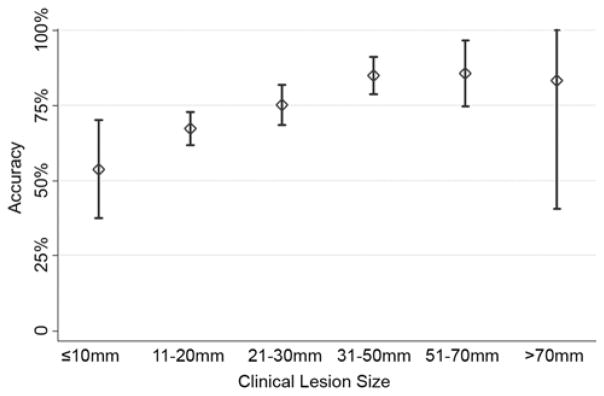

There were 8 cities with more than 25 participants (Table 5) and these comprised 462 of the 682 patients (68%). The observed sensitivity by city varied from 68% to 91% (p=0.03) and the specificity ranged from 15% to 44% (p=0.72). FDG-PET accuracy improved with lesion size (Figure 2) from 67% in lesions that were 1–2cm (sensitivity 76% and specificity 35%) to 84% in lesions that were 3 to 5 cm (sensitivity 90% and specificity 18%) (p<0.001).

Table 5.

FDG-PET sensitivity and specificity by enrolling city with at least 25 participants

| N | Sensitivity (%) | Cancer | Specificity (%) | Benign | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durham, NC | 41 | 91 | 33 | 25 | 8 |

| Birmingham, AL | 111 | 89 | 98 | 15 | 13 |

| Philadelphia, PA | 78 | 85 | 66 | 46 | 12 |

| Pittsburg, PA | 68 | 78 | 60 | 25 | 8 |

| Charlottesville, VA | 52 | 76 | 34 | 33 | 18 |

| Cincinnati, OH | 31 | 73 | 22 | 33 | 9 |

| St. Louis, MO | 54 | 68 | 47 | 29 | 7 |

| Los Angeles, CA | 27 | 67 | 18 | 44 | 9 |

| Chi-square test | p = 0.03 | p = 0.72 |

Figure 2.

FDG-PET accuracy improved with lesion size from 67% in lesions that were 1–2cm (sensitivity 76% and specificity 35%) to 84% in lesions that were 3 to 5 cm (sensitivity 90% and specificity 18%) (p<0.001 using an analysis of variance test). Accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer by lesion size in millimeters. Accuracy = (True Positives + True Negatives)/Total Population

COMMENT

In a retrospective analysis of the ACOSOG Z4031 trial, FDG-PET performed poorly with a sensitivity of 82% and specificity of 31%. The positive predictive value was 85% and the negative predictive value was 26%. The majority of false positive scans were granulomas and the majority of false negative scans were adenocarcinoma. Only 11% of false negative scans occurred in lesions <1cm. The accuracy in lesions < 1cm was 54%. In this population of clinical stage one disease, nearly half, 322 patients, had lesions 2cm in diameter or smaller and FDG-PET accuracy in these patients was 66%. The sensitivity varied across the 8 cities where > 25 patients were enrolled. As expected, FDG-PET accuracy increased with lesion size until lesions were > 3cm, where test accuracy remained constant with increasing size. Increasing age and preoperative lesion size were associated with a malignant diagnosis.

The poor results for FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer reported here study give insight to possible issues for this imaging modality if applied nationally to lung nodules arising from a screening population. The ACOSOG Z4031 study had participants from 17 cities that were also cities that were in the NLST. Pathological stage 1A disease was observed in 45% of the ACOSOG trial and in 40% of the NLST. Currently available FDG-PET scanners have limited ability to detect metabolically active lesions smaller than 7–8mm, and FDG-PET is not recommended for lesions smaller than 1cm due to high false negative rates.(14, 15) For those lesions between 1 and 3cm in diameter, a recent meta-analysis found FDG-PET to be accurate (sensitivity 94% and specificity 83%)(16). The much lower sensitivity observed in the ACOSOG trial may be caused by this population having more lesions between 1 and 2cm compared to those reported in other, single institution series. If more, smaller lesions can be expected to arise from a screening population, then the sensitivity of FDG-PET may be more similar to that observed in our study than previously reported.

The sensitivity and specificity of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer in this trial is similar to two previously reported surgical series from Iowa City, Iowa and Nashville, Tennessee. Both of these regions have a high prevalence of fungal lung disease. Croft and colleagues reported a sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 40% respectively in their smaller, Midwest cohort, with all imaging performed at a tertiary referral center.(12) Deppen et. al. reported a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 40% in a patient population predominantly from the south central U.S., with imaging performed at a variety of regional imaging centers. Both locations noted having a high prevalence of endemic fungal lung disease and granulomas were the most common benign results observed in each of those studies. The current study also had a preponderance of granulomas (69% of false positive FDG-PET results). Fungal lung disease occurs broadly across the Mississippi, Ohio, lower Missouri and Tennessee River Valleys as well as southern Ontario as histoplasmosis and blastomycosis. Coccidioidomycosis is prevalent across the Southwest from west Texas through New Mexico, Arizona and San Joaquin Valley(17). Higher rates of granulomatous disease can be expected from these geographic areas as well. The results of our study question the usefulness of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer in regions with endemic fungal lung disease. Further studies should be performed to determine the most cost effective strategy to diagnose lung cancer comparing FDG-PET to bronchoscopic and CT guided fine needle aspirations.

The results from this study differ from prior meta-analyses by Gould et. al. which reported a sensitivity and specificity of 96% and 78%, respectively and by Cronin et. al. who report similar results for combined FDG-PET/CT scans (95% and 82%, respectively). (10, 16) The differences in our current report from these two studies may arise from a number of factors. First, verification bias is likely present in our current study due to the entire ACOSOG population having a pathologic diagnosis after surgical resection. Verification bias arises when a diagnostic test is used to help determine who receives the gold standard for diagnosis or, in this instance, who is likely to be included in the study. When verification bias occurs, the population measured is more likely to have positive test results, true positives and false positives, and less likely to have negative test results, true negatives and false negatives. Verification bias generally results in a diagnostic test having higher sensitivity due to fewer false negatives being included and lower specificity due to more false positives being included in a study population. Verification bias may explain the observed low specificity but does not explain the lower sensitivity in this study when compared to previous reports(18).

The population of patients in our current study may also be different from the meta-analyses. The inclusion criteria of the Z4031 trial required clinical stage 1 disease prior to surgery so patients with PET avid mediastinal lesions were excluded or required invasive mediastinal staging. Other single institution series used in meta-analysis include those with known or suspected lung cancer, as well as all pre-diagnosis clinical stages. A large number of sites contributing patients in the ACOSOG study are in regions of the United States with a high prevalence of fungal lung disease; and consequently, a large number of granulomas were observed in this series. This was not true for the sites used in the meta-analyses. Finally, the FDG-PET scans in the ACOSOG study were performed at many different institutions as well as from community imaging centers and by multiple different clinicians. This lack of uniformity of test administration introduces variability in scanning quality and interpretations by the clinicians. The meta-analyses evaluated cohorts where the FDG-PET scans were typically performed at the reporting academic institution. Overall, our current study reports a reduced overall accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer when compared to published results.

Our study is one of the largest series evaluating the accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer in clinical stage I disease and represents a national sample with over 650 patients from 39 cities in the United States. Cancer or benign disease was determined pathologically as all patients had a surgical resection. Because it is a clinical study in a large national sample from multiple institutions with multiple surgeons and interpreting radiologists, it is generalizable to clinical practice for early stage patients being evaluated for surgical resection. However, as our study represents a secondary analysis of a clinical trial, biases associated with retrospective reviews of the FDG-PET results are possible. To reduce these biases, reviewers were used who had experience with these types of chart reviews, were blinded to the final pathology and staging and did not conduct the analyses. Because FDG-PET scans were performed at multiple academic and community centers, there were no standard FDG-PET scan administration or interpretation protocols. For example maximum SUV was reported in 461 (67.6%) of patients and 101 (22%) reporting maximum SUV were from a single institution preventing us from performing meaningful analyses using this continuous variable. We believe that variability of FDG-PET administration is both a strength and weakness of the study as it increases the generalizability of the study nationally but the results may not be applicable to high volume centers with expertise in FDG-PET scans. We chose to analyze variability of FDG-PET accuracy at the city level as a method of aggregating data from a relatively homogeneous geographic region. Further analyses are ongoing to determine FDG-PET variability at the patient level. In addition, this study does not address the role of FDG-PET scan for clinical staging of lung cancer. Because original scans were not available, reviewers were unable to consistently determine whether a scan was a FDG-PET only scan which are less accurate than combined FDG-PET/CT scans. Finally, FDG-PET technology is continuously improving and the scans used in this study were performed seven to nine years ago.

In conclusion, the accuracy of FDG-PET scan to diagnose lung cancer in a national sample of patients with known or suspected clinical stage 1 NSCLC is less than previously reported meta-analyses. Results of FDG-PET should be interpreted cautiously when diagnostic or treatment decisions are being made for patients with suspicious pulmonary lesions. Further research is needed to determine the impact of fungal lung disease on false positive FDG-PET results. For the surgeon evaluating smaller or screening discovered lesions in a population with high prevalence of disease, future diagnostic test development should focus on minimization of false negative results and improved negative predictive value when adenocarcinoma, carcinoid or carcinoma in situ tumors are suspected.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Grogan is a recipient of the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service Career Development Award (10-024). This work was also supported by an AHRQ grant number 1 R03 HS021554-01, Vanderbilt Institute for Clinical and Translational Research grant support (UL1TR000011 from NCATS/NIH) for the REDCap database and the ACOSOG CA076001 grant.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- ACCP

American College of Chest Physicians

- ACOSOG

American College of Surgeons Oncology Group

- CT

Computed Tomography

- NCCN

National Comprehensive Cancer Network

- NLST

National Lung Screening Trial

- NPV

negative predictive value

- NSCLC

Non Small Cell Lung Cancer

- PPV

positive predictive value

- SUV

Standard Uptake Value

Footnotes

Meeting Presentation: ASCO 2012 annual meeting

Disclosures and Freedom of Investigation:

The sponsors of this investigator-initiated project had no involvement in the design or conduct of the study, collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript, or decision to submit the manuscript.

The authors had full control of the study design, methods, outcome parameters and results, data analysis, and manuscript production. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Lung cancer screening v1.2012. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines) National Comprehensive Cancer Network; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.2012 Providing guidance on lung cancer screening to patients and physicians. Available at http://www.lung.org/lung-disease/lung-cancer/lung-cancer-screening-guidelines/.08/02/2012.

- 4.Bach PB, Mirkin JN, Oliver TK, et al. Benefits and harms of ct screening for lung cancer: A systematic review. JAMA. 2012;307(22):2418–2429. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.5521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tomita H, Kita T, Hayashi K, Kosuda S. Radiation-induced myositis mimicking chest wall tumor invasion in two patients with lung cancer: A pet/ct study. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37(2):168–169. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181d6249f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humphrey LL, Deffebach M, Pappas M, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography: A systematic review to update the u.S. Preventive services task force recommendation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;N/A(N/A):N/A–N/A. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-6-201309170-00690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. Lung cancer screening with ct: Mayo clinic experience. Radiology. 2003;226(3):756–761. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2263020036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Hartman TE, et al. Ct screening for lung cancer: Five-year prospective experience. Radiology. 2005;235(1):259–265. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2351041662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wahidi MM, Govert JA, Goudar RK, Gould MK, McCrory DC. Evidence for the treatment of patients with pulmonary nodules: When is it lung cancer?: Accp evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132(3 Suppl):94S–107S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gould MK, Maclean CC, Kuschner WG, Rydzak CE, Owens DK. Accuracy of positron emission tomography for diagnosis of pulmonary nodules and mass lesions: A meta-analysis. JAMA. 2001;285(7):914–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.7.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deppen S, Putnam JB, Jr, Andrade G, et al. Accuracy of fdg-pet to diagnose lung cancer in a region of endemic granulomatous disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(2):428–432. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2011.02.052. discussion 433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Croft DR, Trapp J, Kernstine K, et al. Fdg-pet imaging and the diagnosis of non-small cell lung cancer in a region of high histoplasmosis prevalence. Lung Cancer. 2002;36(3):297–301. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(02)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harpole D, Ballman KV, Oberg AL, Whiteley G, Cerfolio R, Keenan R, Jones DR, D’Amico TA, Schrager J, Putnam B. Proteomic analysis for detection of nsclc: Results of acosog z4031. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(Suppl):abstr 7003. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Delbeke D, Coleman RE, Guiberteau MJ, et al. Procedure guideline for tumor imaging with 18f-fdg pet/ct 1. 0. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(5):885–895. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silvestri GA, Gould MK, Margolis ML, et al. Noninvasive staging of non-small cell lung cancer: Accp evidenced-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132(3 Suppl):178S–201S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cronin P, Dwamena B, Kelly A, Carlos R. Solitary pulmonary nodules: Meta-analytic comparison of cross-sectional imaging modalities for diagnosis of malignancy. Radiology. 2008;246:772–782. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2463062148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Edwards L, Acquaviva F, Livesay V, Cross F, Palmer C. An atlas of sensitivity to tuberculin, ppd-b, and histoplasmin in the united states. American Review of Respiratory Disease. 1969;99(4)(Suppl):1–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauer MS, Murthy SC, Blackstone EH, Okereke IC, Rice TW. [18f]fluorodeoxyglucose uptake by positron emission tomography for diagnosis of suspected lung cancer: Impact of verification bias. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(2):161–165. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]