Abstract

Background

Over the last decade laparoscopic pancreatic surgery (LPS) has emerged as an alternative to open pancreatic surgery (OPS) in selected patients with neuroendocrine tumours (NET) of the pancreas (PNET). Evidence on the safety and efficacy of LPS is available from non-comparative studies.

Objectives

This study was designed as a meta-analysis of studies which allow a comparison of LPS and OPS for resection of PNET.

Methods

Studies conducted from 1994 to 2012 and reporting on LPS and OPS were reviewed. Studies considered were required to report on outcomes in more than 10 patients on at least one of the following: operative time; hospital length of stay (LoS); intraoperative blood loss; postoperative morbidity; pancreatic fistula rates, and mortality. Outcomes were compared using weighted mean differences and odds ratios.

Results

Eleven studies were included. These referred to 906 patients with PNET, of whom 22% underwent LPS and 78% underwent OPS. Laparoscopic pancreatic surgery was associated with a lower overall complication rate (38% in LPS versus 46% in OPS; P < 0.001). Blood loss and LoS were lower in LPS by 67 ml (P < 0.001) and 5 days (P < 0.001), respectively. There were no differences in rates of pancreatic fistula, operative time or mortality.

Conclusions

The nature of this meta-analysis is limited; nevertheless LPS for PNET appears to be safe and is associated with a reduced complication rate and shorter LoS than OPS.

Introduction

Minimally invasive pancreatic surgery was introduced in the early 1990s with a report on laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy by Gagner and Pomp1 and a report on pancreatic left resection by Cuschieri.2 Following this encouraging initial experience, the technical feasibility of the procedure has been demonstrated in case reports,3 in larger single-centre4 and multi-institution5,6 cohorts, and in comparative studies.7–10 The laparoscopic approach to the resection of pancreatic lesions has been in general considered with more caution than laparoscopic procedures at other sites because of the inherent technical challenges of pancreatic surgery and its propensity for perioperative complications. Three recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses confirmed that laparoscopic pancreatic surgery (LPS) is a safe procedure.11–13 However, these reviews analysed results achieved in distal pancreatectomy only and were not specific on the underlying pathology. Whereas in several series adenocarcinomas have dominated in the open pancreatic surgery (OPS) group, benign lesions or tumours with low malignant potential have constituted the majority of disease types in the LPS group. These inconsistent entry criteria detract from the evidence on the efficacy of LPS in different pathologies encountered in pancreatic surgery. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PNET) present per se the ideal entity for laparoscopic surgery because they are often small and of less aggressive biological behaviour. A group associated with one of the authors (LF-C) of the present review were among the first to demonstrate that pancreatic resection performed using a laparoscopic approach in both apparently benign and malignant PNET is a safe procedure providing longterm results comparable with those achieved in open surgery.14

The purpose of this study is to evaluate the published literature that allows for the comparison of LPS and OPS in the resection of PNET. To the best of the present authors' knowledge, this is the first report to address such a comparison in the context of PNET. The outcomes of each technique were quantified using the meta-analytical method, while considering variations in the characteristics of the various reports that might influence the overall estimate of the outcome of interest.

Materials and methods

Study selection

A systematic review of the literature was performed using MEDLINE/PubMed, EMBASE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews to identify all studies published until July 2012, which reported data on outcomes of both LPS and OPS for PNET.

The systematic review protocol was registered to the PROSPERO registry and is available at: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/Prospero/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42011001727. The search terms used were ‘neuroendocrine tumours’, ‘pancreatic surgery’, ‘pancreatic resection’, ‘conversion’, ‘blood loss’, ‘hospital stay’, ‘complications’ and ‘mortality’ in various combinations.

The related articles function was used to extend the search. References of the articles acquired were also searched manually. All abstracts, studies and citations acquired were reviewed. The last search was conducted on 15 July 2012.

Inclusion criteria

All published randomized and non-randomized studies, written in English, French or German, allowing for the comparison of LPS and OPS in the resection of PNET and including at least 10 patients in total were considered. To enter the analysis, studies were required to refer to patients aged >18 years and to make an objective evaluation of at least one of the outcome measures of operative time, hospital length of stay (LoS), intraoperative blood loss, postoperative morbidity, pancreatic fistula rate, and mortality. If more than one study was reported from the same institution, either the study with the larger sample size or the most recent study was included, provided the outcome measures were not mutually exclusive.

Exclusion criteria

Studies that failed to fulfil the inclusion criteria were excluded. In addition, studies were excluded if they: (i) included children or adolescents; (ii) included patients who did not undergo surgery; (iii) did not report on the outcome measures already listed or did not support the calculation of these outcome measures in their published reports; (iv) focused on pathologies of pancreatic lesions other than PNET; (v) included patients with PNET as a subgroup, unless data were presented separately for each subgroup, and (vi) included fewer than 10 patients in the PNET subgroup.

Data extraction

Each study was independently assessed for eligibility by two reviewers (PD and DAR) for inclusion or exclusion from the review and data on the following were extracted: first author; year of publication; country of origin; study design; characteristics of the study population; number of subjects operated on with each technique; rate of conversion from LPS to OPS, and perioperative outcomes. Any differences were settled by consensus.

Outcomes of interest and definitions

Open and laparoscopic pancreatic surgery were compared on the basis of several perioperative outcomes. These included overall complication rate and postoperative fistula rate as primary outcomes, and secondary outcomes such as operation duration, intraoperative blood loss, hospital LoS and conversion to open surgery. Patients in whom conversion had been performed were retained in the LPS group as the meta-analysis was performed in an intention-to-treat manner. Not all of the studies included had defined the occurrence of pancreatic fistula according to the definition of the International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula15 and therefore rates of pancreatic fistula were calculated on the basis of the definitions used by the respective authors.

Statistical analysis

This study was performed in line with the recommendations of the Cochrane Collaboration.16 Dichotomous variables were analysed using odds ratios (ORs), which represented the odds of an event occurring in the LPS group compared with the OPS group. An OR of < 1 favoured the LPS group and the point estimate for the OR was considered statistically significant if the P-value was < 0.05, provided the 95% confidence interval (CI) did not include the value 1. Studies that contained a zero value for an outcome of interest in both the LPS and OPS arms were discarded from the analysis for this particular event. If a study contained a zero value for an event in one of the two groups, Yates' correction was added. The effect of Yates' correction is to prevent the overestimation of statistical significance for small data when ‘zero cells’ are present in a 2 × 2 contingency table. Such zero cells are reported to overestimate the OR measure and the corresponding standard deviation (SD).17 For the Yates' correction, a value of 0.5 is added to each zero cell of the 2 × 2 table for the study in question.

In the analysis of continuous variables the weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated. A random-effect meta-analytical technique was used for both continuous and dichotomous outcomes. In a random-effect model, it is assumed that there is variation among studies and therefore the calculated OR has a more conservative value. The random-effect model was selected to account for the heterogeneity produced by the inherent differences in the study population: patients were operated at different centres by different surgeons; the selection criteria for each surgical technique were inconsistent, and patient risk profiles were variable.

A qualitative assessment of the studies was performed, following the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.18 For the assessment, each study was examined on three factors: patient selection; comparability of the study groups, and assessment of the outcome. A score of 0–9 stars was assigned to each study according to the coding manual for cohort studies of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Heterogeneity was assessed in a sensitivity analysis using the following groups: (i) all studies, and (ii) studies reporting only on insulinomas. A sensitivity analysis on high- versus low-quality studies based on the Newcastle–Ottawa score was not feasible as all included studies scored between 6 (one study) and 7 (10 studies) on the relative scale (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies reporting on patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours (PNET) submitted to open pancreatic surgery (OPS) or laparoscopic pancreatic surgery (LPS)

| Authors | Year | Study type | Type of PNET | Period of patient recruitment | Country | Patients, n | LPS, n | OPS, n | Conversion, n | Study quality (Newcastle–Ottawa scale) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Espana-Gomez et al.19 | 2009 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 1995–2007 | Spain | 34 | 21 | 13 | 7 | ******* |

| Gumbs20 | 2008 | Retrospective | Functioning (23%) Non-functioning (77%) |

1992–2006 | France | 31 | 18 | 13 | 1 | ******* |

| Hu et al.21 | 2011 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 2000–2009 | China | 89 | 43 | 46 | 2 | ******* |

| Karaliotas & Sgourakis22 | 2009 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 1999–2008 | Greece | 12 | 5 | 7 | 1 | ******* |

| Kazanjian et al.23 | 2006 | Retrospective | Functioning (29%) Non-functioning (71%) |

1990–2005 | USA | 70 | 4 | 66 | NR | ******* |

| Liu et al.24 | 2007 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 2000–2006 | China | 48 | 7 | 41 | 3 | ******* |

| Lo et al.25 | 2004 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 1999–2002 | China | 10 | 4 | 6 | 0 | ******* |

| Roland et al.26 | 2008 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 1998–2007 | USA | 37 | 22 | 15 | 2 | ******* |

| Sa Cunha et al.27 | 2006 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 1999–2005 | China | 21 | 12 | 9 | 3 | ****** |

| Zerbi et al.28 | 2011 | Prospective | Functioning (27%) Non-functioning (73%) |

2004–2007 | Italy | 262 | 21 | 241 | NR | ******* |

| Zhao et al.29 | 2011 | Retrospective | Insulinomas | 1990–2010 | China | 292 | 46 | 246 | 19 | ******* |

| Total | 906 | 203 | 703 |

NR, not reported.

Results

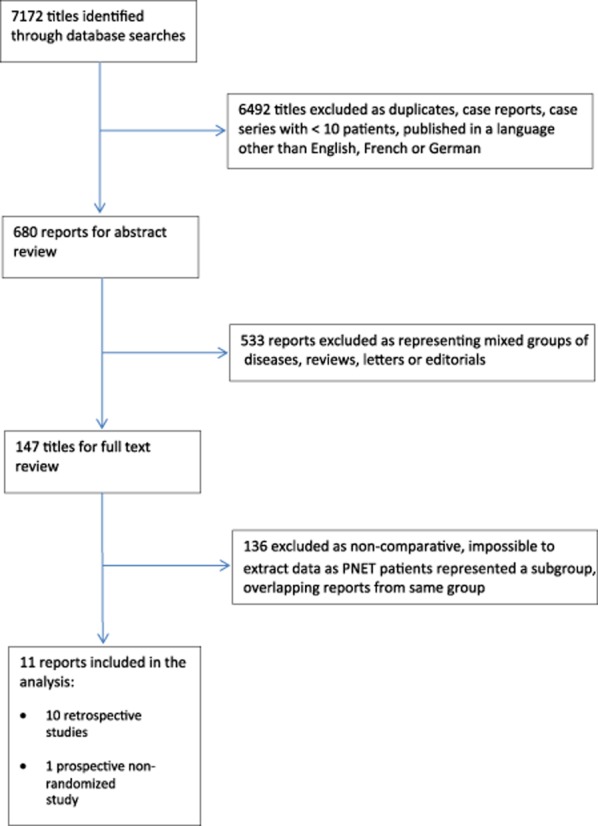

A total of 7172 potentially eligible published articles were identified in the literature search. The algorithm of the search is summarized in Fig. 1. Eleven studies matched the selection criteria and were suitable for meta-analysis.19–29 Studies included retrospective reviews (n = 10) and a prospective non-randomized trial (NRCT) (n = 1). There were no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) comparing the two procedures. A total of 906 patients were included in the analysis, of whom 203 (22%) had LPS and 703 (78%) had OPS. A review of the data extraction showed there to be agreement between the reviewers.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the literature search. PNET, pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour

The characteristics of the studies are summarized in Table 1. All studies included only PNET. In eight reports the underlying pathology was an insulinoma. In the remaining three, both functioning and non-functioning PNET were considered. Nine studies reported conversion rates (range: 9–41%).

The results of the meta-analysis with regard to operative parameters, postoperative complications, LoS and mortality will be reported in detail. Other parameters considered in the data extraction but for which data were not presented uniformly (such as group characteristics, type of surgery performed, tumour size and stage, readmission rates and transfusion rates) are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Overview of outcomes considered during data extraction but found to be either not reported (NR) or non-uniformly reported, thus precluding meta-analysis

| Authors | Learning curve | Differences between the groups | Type of surgery | Type of pancreatic stump closure/use of drains | Tumour stage | Readmission rates | Cause of death | Transfusions | Definition of pancreatic fistula used in reporting | Definition of complications used in reporting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Espana-Gomez et al.19 | NR | Similar in age and sex | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Gumbs et al.20 | NR | Similar in age and tumour size | OPS group Enuc: 5 DP: 5 PD: 2 CP: 1 |

LPS group Enuc: 6 DP: 11 PD: 1 CP: 0 |

NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | NR | Clavien–Dindo |

| Hu et al.21 | NR | Similar in age, sex and tumour size | OPS group Enuc: 44 DP: 0 Other: 2 |

LPS group Enuc: 21 DP: 20 Other: 2 |

NR | NR | NR | No deaths | 2 in each group | ISGPF | NR |

| Karaliotas & Sgourakis22 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | NR | NR | |

| Kazanjian et al.23 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | NR | NR | |

| Liu et al.24 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | NR | NR | |

| Lo et al.25 | NR | Different in age | OPS group Enuc: 6 |

LPS group Enuc: 2 DP: 2 |

GIA-II 45 mm stapler/NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | NR | NR |

| Roland et al.26 | NR | Similar in sex | OPS group Enuc: 16 DP: 3 |

LPS group Enuc: 8 DP: 10 |

GIA-II 45 mm stapler/NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | NR | NR |

| Sa Cunha et al.27 | NR | Similar in age and sex | OPS group Enuc: 44 DP: 4 DP: 1 |

LPS group Enuc: 7 DP: 5 PD: 0 |

NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | At least one of: (i) amylase in drain fluid >5 times serum after day 5 and (ii) fluid collection on CT scan | NR |

| Zerbi et al.28 | NR | Similar in age different in sex | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | |

| Zhao et al.29 | NR | Similar in age and sex | OPS groupa Enuc: 199 DP: 37 SegP: 15 DPPHR: 3 Other: 20 |

LPS groupa Enuc: 30 DP: 16 |

NR | NR | NR | No deaths | NR | ISGPF | NR |

OPS, open pancreatic surgery; LPS, laparoscopic pancreatic surgery; Enuc, enucleation; DP, distal pancreatic resection; PD, pancreaticoduodenectomy; CP, central pancreatectomy; SegP, segmental pancreatic resection; DPPHR, duodenum-preserving pancreatic head resection; ISGPF: International Study Group on Pancreatic Fistula; CT, computed tomography; NR, not reported.

Operative parameters

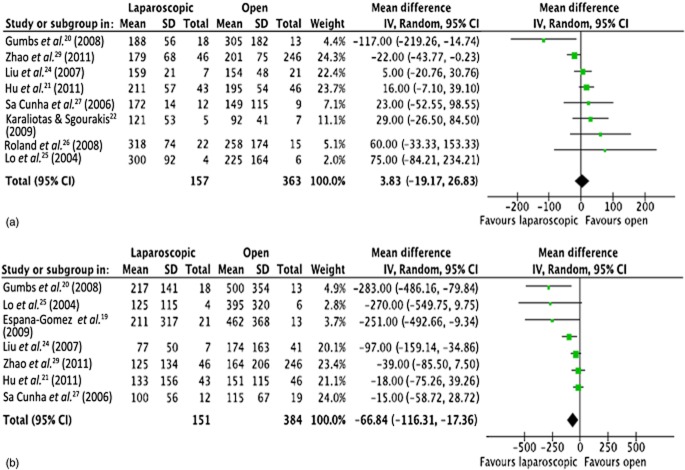

Eight studies reported on operative times20–22,24–27,29 (Fig. 2). Mean operative times in both groups were almost identical (4 min lower in the OPS group than the LPS group, 95% CI −19.2 to 26.9; P = 0.740). Intraoperative blood loss was reported in seven studies19–21,24,25,27,29 (Fig. 2). Blood loss was significantly lower in the LPS group than in the OPS group by 67 ml (95% CI −116.3 to −17.4; P = 0.008).

Figure 2.

Meta-analysis of operative parameters: (a) length of operation [heterogeneity: τ2 = 442.54; χ2 = 14.78; d.f. = 7 (P = 0.04); I2 = 53%; test for overall effect: Z = 0.33 (P = 0.74)], and (b) blood loss [heterogeneity: τ2 = 2162.52; χ2 = 15.96; d.f. = 6 (P = 0.01); I2 = 62%; test for overall effect: Z = 2.65 (P = 0.008)]. SD, standard deviation; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; squares, point estimates of treatment effects; diamond, summary estimate from the pooled studies with 95% CIs

Postoperative complications

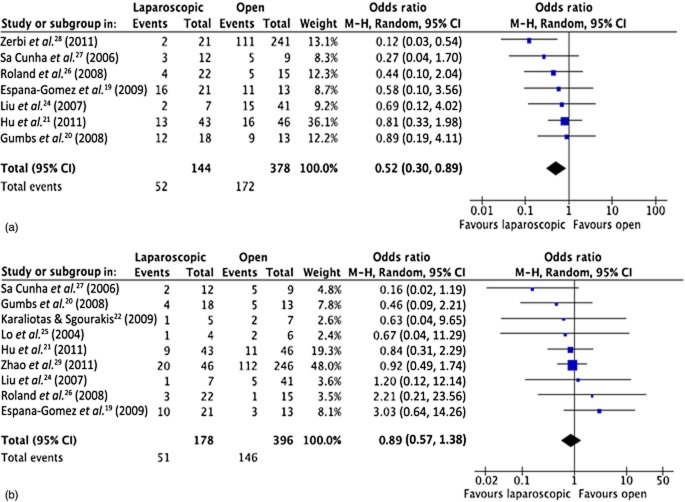

Seven studies reported on the overall complication rate19–21,24,26–28 and nine studies19–22,24–27,29 reported on rates of observed pancreatic fistula (Fig. 3). Meta-analysis showed a significantly lower incidence of overall morbidity of 36% (52 of 144) in LPS versus 46% (172 of 378) in OPS (OR = 0.52, 95% CI 0.30–0.89; P < 0.002). Pancreatic fistula rates did not differ between the two groups [LPS: 51 events in 178 patients (29%); OPS: 146 events in 396 patients (37%); OR = 0.89, 95% CI 0.57–1.38; P = 0.590]. An overview of complications that were not reported uniformly among the studies and for which a meta-analysis was not feasible is presented in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Meta-analysis of postoperative complications: (a) overall complications [heterogeneity: τ2 = 0.00; χ2 = 5.92; d.f. = 6 (P = 0.43); I2 = 0%; test for overall effect: Z = 2.40 (P = 0.02)], and (b) rates of pancreatic fistula [heterogeneity: τ2 = 0.00; χ2 = 6.65; d.f. = 8 (P = 0.57); I2 = 0%; test for overall effect: Z = 0.54 (P = 0.59)]. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; squares, point estimates of treatment effects; diamond, summary estimate from the pooled studies with 95% CIs

Table 3.

Overview of causes of morbidity (other than pancreatic fistula) following open pancreatic surgery (OPS) or laparoscopic pancreatic surgery (LPS)

| Authors | Complications |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-abdominal collection |

Pleural effusion |

Postoperative fever/infection |

Postoperative haemorrhage |

Necrotizing pancreatitis |

Other |

|||||||

| OPS | LPS | OPS | LPS | OPS | LPS | OPS | LPS | OPS | LPS | OPS | LPS | |

| Espana-Gomez et al.19 | 3 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | 5 |

| Gumbs et al.20 | 2 | 3 | 1 | – | 1 | – | – | 2 | – | 1 | – | 2 |

| Hu et al.21 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 5 | 3 |

| Karaliotas & Sgourakis22 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Kazanjian et al.23 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| Liu et al.24 | – | – | – | – | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | 12 | 1 |

| Lo et al.25 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Roland et al.26 | 1 | 0 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 3 | 1 |

| Sa Cunha et al.27 | 0 | 1 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Zerbi et al.28 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | ||||||

| Zhao et al.29 | 16 | 1 | – | – | – | – | 2 | 0 | – | – | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 22 | 6 | 1 | – | 4 | – | 2 | 3 | 1 | 27 | 12 | |

NR, not reported.

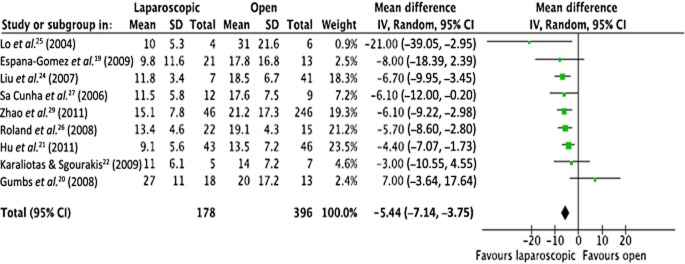

Length of hospital stay

Nine studies reported on the hospital LoS19–22,24–27,29 (Fig. 4). Meta-analysis showed that LPS patients had a significantly lower LoS compared with OPS patients amounting to a mean of 5 days (95% CI −7.14 to −3.75; P < 0.00001).

Figure 4.

Meta-analysis of length of hospital stay [heterogeneity: τ2 = 1.33; χ2 = 10.15; d.f. = 8 (P = 0.25); I2 = 21%; test for overall effect: Z = 6.29 (P < 0.0001)]. SD, standard deviation; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; squares, point estimates of treatment effects; diamond, summary estimate from the pooled studies with 95% CIs

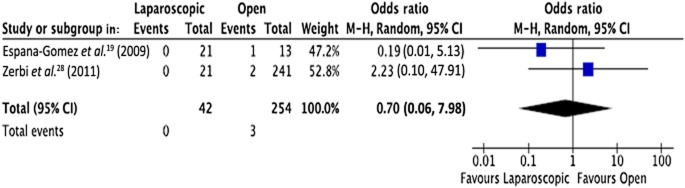

Mortality

Only two studies19,28 reported data on postoperative mortality (Fig. 5). These studies included totals of 42 patients in the LPS group and 254 patients in the OPS group. Reported deaths numbered zero and three, respectively (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.06–7.98; P = 0.780).

Figure 5.

Meta-analysis of mortality [heterogeneity: τ2 = 0.46; χ2 = 1.17; d.f. = 1 (P = 0.28); I2 = 15%; test for overall effect: Z = 0.28 (P = 0.78)]. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; squares, point estimates of treatment effects; diamond, summary estimate from the pooled studies with 95% CIs

Sensitivity analysis

The sensitivity analysis in this study included reports focusing exclusively on insulinomas. Outcomes that could not be analysed because of insufficient data (fewer than two studies reporting on the outcome) were excluded from the sensitivity analysis. Subgroup and sensitivity analyses on studies of high versus low quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale were also attempted (Table 1). This was not possible because all except one of the studies included scored 7 on the Newcastle–Ottawa scale. Further assumptions considered for the sensitivity analysis included: (i) tumour size; (ii) studies that matched treatment groups on clinical and pathological data, particularly for functioning versus non-functioning PNET, and (iii) studies that matched treatment groups according to type of operation performed. However, data could not be extracted for any of these groups and therefore sensitivity analyses on these assumptions were not feasible.

Studies reporting on insulinomas

Eight studies19,21,22,24–27,29 reported exclusively on insulinomas. Differences that remained statistically significant referred to hospital LoS (P < 0.0001) and blood loss (P = 0.020). By contrast, overall complication rates did not differ significantly between the OPS and LPS groups (P = 0.120). Differences in operation duration (P = 0.490) and pancreatic fistula rate (P = 0.780) were also non-significant. Only one study reported mortality and therefore mortality could not be assessed in this sensitivity subgroup analysis. Data from the sensitivity analysis are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Overview of the sensitivity analysis of studies reporting on outcomes in patients with insulinomas submitted to open pancreatic surgery (OPS) or laparoscopic pancreatic surgery (LPS)

| Outcome | Studies, n | Patients, n |

Events, n |

OR/MWD | 95% CI | P-value | τ2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPS | OPS | LPS | OPS | ||||||

| Analysis on insulinomas | 8 | 160 | 383 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Overall complication rate | 5 | 105 | 124 | 38 | 52 | 0.61 | 0.33–1.14 | 0.12 | 0.00 |

| Fistula rate | 8 | 160 | 383 | 47 | 141 | 0.94 | 0.59–1.48 | 0.78 | 0.00 |

| Blood loss | 6 | 133 | 371 | – | – | −50.85 | −93.04 to −8.66 | 0.02 | 1242.7 |

| Duration of operation | 7 | 139 | 350 | – | – | 6.66 | −12.41 to 25.74 | 0.49 | 211.85 |

| Hospital length of stay | 8 | 160 | 383 | – | – | −5.67 | −7.07 to −4.28 | <0.00001 | 0.00 |

| Mortality | None | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

OR, odds ratio; MWD, mean weighted difference; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Discussion

This review confirms that laparoscopic resection is feasible and safe in patients with PNET, in line with previous meta-analyses on laparoscopic distal pancreas resection which analysed studies irrespective of the underlying pancreatic pathology reported.11–13 However, as in the previous meta-analyses on LPS versus OPS, very few studies were found to have matched subjects in the study design or to have adjusted for confounders in the analysis. To compensate for this problem, a sensitivity analysis for the studies reporting on insulinomas was performed. Nevertheless, there is a reporting bias that cannot be compensated for and this should be considered in any interpretation of the results.

There has been growing acceptance of laparoscopic approaches in pancreatic surgery in the last decade and an increasing number of large case series and multi-institution studies have compared the laparoscopic with the open approach in terms of safety and efficacy.9,10,28,30 In a meta-analysis comparing laparoscopic with open distal pancreas resection, Venkat et al.13 reported lower blood loss, a lower overall rate of complications and a shorter hospital stay in the laparoscopic arm. However, complications that may potentially be associated with prolonged procedures (such as deep vein thrombosis) were not reported. There were no differences in rates of pancreatic fistula, reoperation or mortality.13 There were no data on the surgical techniques used, type of pancreatic stump closure or use of drains.13 Moreover, in this meta-analysis,13 as in that performed by Nigri et al.31 on the same subject with similar results, outcomes were not correlated to specific underlying pancreatic pathology. This is also true of most of the published series comparing laparoscopic with open pancreatic surgery, in which all underlying pathologies are considered collectively for each arm.9,10,32 Therefore, data attained from these studies must be interpreted with a caveat for the subgroup of PNET patients.9 Some of the characteristics inherent to PNET are of special interest when determining the optimal surgical approach. Patients with secreting tumours are frequently diagnosed at an early stage of disease with small tumours. Parenchyma-preserving limited pancreatic resection is the approach to pursue in this setting.33–36 In patients with gastrinomas, a laparoscopic approach is generally not recommended as 60–90% of patients will be found to have pancreatic and/or submucosal duodenal lesions frequently associated with lymph node metastases.37

Data for 906 patients, of whom 203 (22%) underwent LPS and 703 (78%) underwent OPS, were considered in this review. By contrast with data reported in single-centre series,10,38 both the present report and other reviews comparing the laparoscopic and open techniques13,31 show that overall morbidity is lower in LPS patients than in OPS patients (36% and 45%, respectively). It is noteworthy that no differences in pancreatic fistula rates emerged. Nevertheless, these data should be interpreted with caution because only a few studies defined complications according to validated classification systems.15 The laparoscopic approach was found to significantly reduce hospital LoS by 5 days and to lower blood loss significantly by 67 ml (P < 0.008). Whether a difference of 67 ml in intraoperative blood loss will have any impact on clinical outcome remains a matter of debate. Only one study reported on the actual blood units transfused in each group. Only two studies reported on mortality and found no difference between the groups. Several important issues in pancreatic surgery for neuroendocrine tumours are functionality of the tumour, type of tumour, tumour size and location, multi-centricity, completeness of resection and regional lymph node dissection.14,39 These were not properly addressed in most of the studies.

An analysis of studies that allow for the comparison of different procedures in a rare disease has several limitations. These limit the nature of the meta-analysis itself. Firstly, some studies show differences in sample sizes and the characteristics of each group that are not always appropriately addressed. Secondly, because of the inclusion of NRCTs, there is a selection bias in the treatment groups. The pooling of data from NRCTs is a debated topic in the field of meta-analysis. An NRCT may exaggerate the effect of an intervention, either by intrinsic flaws or by external factors such as publication bias. However, there is evidence that the pooling of data from well-designed NRCTs of surgical procedures may be reliable.40 Thirdly, there is heterogeneity produced by differences in definitions and measurements of the outcomes of interest that may not have been reported in the study methodology. The present study tried to address this issue by performing a quality assessment and subgroup analysis. Fourthly, selective reporting and non-publication bias introduce limitations that cannot be accounted for. Finally, from a clinical point of view, it would be of interest to compare LPS with OPS for further outcomes with regard to tumour size, tumour histopathological classification and types of operations performed in each group. Although the initial aim of the present study was to extract relevant data and perform such analyses, these data were either not reported at all or reported only as descriptive statistics, thus making the pooling of data impossible.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis shows that LPS is a safe approach for PNETs. It is associated with a lower overall complication rate, less blood loss and a shorter hospital LoS compared with the standard open technique. Operative times and rates of pancreatic fistula are similar in LPS and OPS. There is no difference in mortality. This suggests that LPS is an option that should be included in the armamentarium of surgical treatment for patients with PNET.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- Gagner M, Pomp A. Laparoscopic pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:408–410. doi: 10.1007/BF00642443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuschieri A. Laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1994;39:178–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sussman LA, Christie R, Whittle DE. Laparoscopic excision of distal pancreas including insulinoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1996;66:414–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.1996.tb01222.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Cruz L, Cosa R, Blanco L, Levi S, Lopez-Boado MA, Navarro S. Curative laparoscopic resection for pancreatic neoplasms: a critical analysis from a single institution. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1607–1621. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0266-0. discussion 1621–1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mabrut JY, Fernandez-Cruz L, Azagra JS, Bassi C, Delvaux G, Weerts J, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: results of a multicentre European study of 127 patients. Surgery. 2005;137:597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber SM, Cho CS, Merchant N, Pinchot S, Rettammel R, Nakeeb A, et al. Laparoscopic left pancreatectomy: complication risk score correlates with morbidity and risk for pancreatic fistula. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2825–2833. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0597-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker MS, Bentrem DJ, Ujiki MB, Stocker S, Talamonti MS. A prospective single-institution comparison of perioperative outcomes for laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2009;146:635–643. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2009.06.045. discussion 643–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho CS, Kooby DA, Schmidt CM, Nakeeb A, Bentrem DJ, Merchant NB, et al. Laparoscopic versus open left pancreatectomy: can preoperative factors indicate the safer technique? Ann Surg. 2011;253:975–980. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182128869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kooby DA, Gillespie T, Bentrem D, Nakeeb A, Schmidt MC, Merchant NB, et al. Left-sided pancreatectomy: a multicentre comparison of laparoscopic and open approaches. Ann Surg. 2008;248:438–446. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318185a990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijan SS, Ahmed KA, Harmsen WS, Que FG, Reid-Lombardo KM, Nagorney DM, et al. Laparoscopic vs. open distal pancreatectomy: a single-institution comparative study. Arch Surg. 2010;145:616–621. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin T, Altaf K, Xiong JJ, Huang W, Javed MA, Mai G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. HPB. 2012;14:711–724. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pericleous S, Middleton N, McKay SC, Bowers KA, Hutchins RR. Systematic review and meta-analysis of case-matched studies comparing open and laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: is it a safe procedure? Pancreas. 2012;41:993–1000. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31824f3669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkat R, Edil BH, Schulick RD, Lidor AO, Makary MA, Wolfgang CL. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is associated with significantly less overall morbidity compared to the open technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1048–1059. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318251ee09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Cruz L, Blanco L, Cosa R, Rendon H. Is laparoscopic resection adequate in patients with neuroendocrine pancreatic tumours? World J Surg. 2008;32:904–917. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9467-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, Fingerhut A, Yeo C, Izbicki J, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke M, Horton R. Bringing it all together: Lancet–Cochrane collaborate on systematic reviews. Lancet. 2001;357:1728. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04934-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N, Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1959;22:719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for the assessment of the quality of non-randomized studies in meta-analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25:603–605. doi: 10.1007/s10654-010-9491-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espana-Gomez MN, Velazquez-Fernandez D, Bezaury P, Sierra M, Pantoja JP, Herrera MF. Pancreatic insulinoma: a surgical experience. World J Surg. 2009;33:1966–1970. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumbs AA, Gres P, Madureira F, Gayet B. Laparoscopic vs. open resection of pancreatic endocrine neoplasms: single institution's experience over 14 years. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2008;393:391–395. doi: 10.1007/s00423-007-0255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu M, Zhao G, Luo Y, Liu R. Laparoscopic versus open treatment for benign pancreatic insulinomas: an analysis of 89 cases. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:3831–3837. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1800-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaliotas C, Sgourakis G. Laparoscopic versus open enucleation for solitary insulinoma in the body and tail of the pancreas. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1869. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0954-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazanjian KK, Reber HA, Hines OJ. Resection of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours: results of 70 cases. Arch Surg. 2006;141:765–769. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.141.8.765. discussion 769–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Peng C, Zhang S, Wu Y, Fang H, Sheng H, et al. Strategy for the surgical management of insulinomas: analysis of 52 cases. Dig Surg. 2007;24:463–470. doi: 10.1159/000111822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CY, Chan WF, Lo CM, Fan ST, Tam PK. Surgical treatment of pancreatic insulinomas in the era of laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:297–302. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roland CL, Lo CY, Miller BS, Holt S, Nwariaku FE. Surgical approach and perioperative complications determine short-term outcomes in patients with insulinoma: results of a bi-institutional study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:3532–3537. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-0157-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa Cunha A, Beau C, Rault A, Catargi B, Collet D, Masson B. Laparoscopic versus open approach for solitary insulinoma. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:103–108. doi: 10.1007/s00464-006-0021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zerbi A, Capitanio V, Boninsegna L, Pasquali C, Rindi G, Delle Fave G, et al. Surgical treatment of pancreatic endocrine tumours in Italy: results of a prospective multicentre study of 262 cases. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 2011;396:313–321. doi: 10.1007/s00423-010-0712-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao YP, Zhan HX, Zhang TP, Cong L, Dai MH, Liao Q, et al. Surgical management of patients with insulinomas: result of 292 cases in a single institution. J Surg Oncol. 2011;103:169–174. doi: 10.1002/jso.21773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaraman S, Gonen M, Brennan MF, D'Angelica MI, DeMatteo RP, Fong Y, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy: evolution of a technique at a single institution. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:503–509. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigri GR, Rosman AS, Petrucciani N, Fancellu A, Pisano M, Zorcolo L, et al. Meta-analysis of trials comparing minimally invasive and open distal pancreatectomies. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1642–1651. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1456-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiNorcia J, Schrope BA, Lee MK, Reavey PL, Rosen SJ, Lee JA, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy offers shorter hospital stays with fewer complications. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1804–1812. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1264-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falconi M, Zerbi A, Crippa S, Balzano G, Boninsegna L, Capitanio V, et al. Parenchyma-preserving resections for small non-functioning pancreatic endocrine tumours. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1621–1627. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0949-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller MW, Friess H, Kleeff J, Hinz U, Wente MN, Paramythiotis D, et al. Middle segmental pancreatic resection: an option to treat benign pancreatic body lesions. Ann Surg. 2006;244:909–918. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000247970.43080.23. discussion 918–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norton JA. Surgery for primary pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. J Gastrointest Surg. 2006;10:327–331. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt SC, Pitt HA, Baker MS, Christians K, Touzios JG, Kiely JM, et al. Small pancreatic and periampullary neuroendocrine tumours: resect or enucleate? J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1692–1698. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0946-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen RT, Cadiot G, Brandi ML, de Herder WW, Kaltsas G, Komminoth P, et al. ENETS Consensus Guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine neoplasms: functional pancreatic endocrine tumour syndromes. Neuroendocrinology. 2012;95:98–119. doi: 10.1159/000335591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson EJ, Gagner M, Salky B, Inabnet WB, Brower S, Edye M, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: single-institution experience of 19 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)01018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Cruz L, Molina V, Vallejos R, Jimenez Chavarria E, Lopez-Boado MA, Ferrer J. Outcome after laparoscopic enucleation for non-functional neuroendocrine pancreatic tumours. HPB. 2012;14:171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00422.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham NS, Byrne CJ, Young JM, Solomon MJ. Meta-analysis of well-designed non-randomized comparative studies of surgical procedures is as good as randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:238–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]