Abstract

Purpose

More accurate assessment of prognosis is important to further improve the choice of risk-related therapy in neuroblastoma (NB) patients. In this study, we aimed to establish and validate a prognostic miRNA signature for children with NB and tested it in both fresh frozen and archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples.

Experimental Design

Four hundred-thirty human mature miRNAs were profiled in two patient subgroups with maximally divergent clinical courses. Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to select miRNAs correlating with NB patient survival. A 25-miRNA gene signature was built using 51 training samples, tested on 179 test samples, and validated on an independent set of 304 fresh frozen tumor samples and 75 archived FFPE samples.

Results

The 25-miRNA signature significantly discriminates the test patients with respect to progression-free and overall survival (P < 0.0001), both in the overall population and in the cohort of high-risk patients. Multivariate analysis indicates that the miRNA signature is an independent predictor of patient survival after controlling for current risk factors. The results were confirmed in an external validation set. In contrast to a previously published mRNA classifier, the 25-miRNA signature was found to be predictive for patient survival in a set of 75 FFPE neuroblastoma samples.

Conclusions

In this study, we present the largest NB miRNA expression study so far, including more than 500 NB patients. We established and validated a robust miRNA classifier, able to identify a cohort of high-risk NB patients at greater risk for adverse outcome using both fresh frozen and archived material.

Introduction

Given the clinical heterogeneity of neuroblastoma (NB), accurate prognostic classification of patients with this tumor is one of the major challenges to improve the choice of risk-related therapy. Clinical experience with the currently used risk stratification systems suggests that the stratification of patients for treatment is useful (1). Nevertheless, patients with the same clinicopathologic and genetic parameters, receiving the same treatment, can have markedly different clinical courses.

On the basis of the assumption that differences in outcome are mainly driven through underlying genetic and biological characteristics, gene expression studies have been undertaken to detect new prognostic markers and to establish gene expression-based classifiers for improved neuroblastoma patient care. Recently, we established a messenger RNA (mRNA) gene expression classifier and validated the performance of this classifier in 2 independent patient cohorts (2). However, we could clearly show an adverse effect of poor RNA quality on the performance of the 59-mRNA classifier (3).

Recently, an important class of small noncoding RNAs (ncRNA) regulating mRNA expression, termed microRNAs (miRNA), have been shown to be implicated in various cancers, including NB (4, 5) and are known to be less sensitive to RNA degradation processes. Here, we set out to conduct an in-depth study on an unprecedentedly large cohort of primary untreated neuroblastoma tumors to unequivocally establish the possible prognostic power of miRNA classifiers. To this purpose, we tested and validated the performance of a 25-miRNA prognostic classifier in 3 independent patient cohorts including both fresh frozen and archived formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) material.

Materials and Methods

Patients and tumor samples

The first train-test cohort consisted of 230 NB patients (27 from Ghent, Belgium, 54 from Essen, Germany, 31 from Valencia, Spain, 43 from Dublin, Ireland, and 75 from Amsterdam, the Netherlands). Patients were only included if primary untreated NB tumor RNA (at least 60% tumor cells and confirmed histologic diagnosis of NB) was present. All patients provided consent and were enrolled on at least one study: International Society of Paediatric Oncology, European Neuroblastoma Group (SIOPEN), the Gesellschaft fuer Paediatrische Onkologie und Haematologie (GPOH), the Children’s Oncology Group (COG-United States) study, Dutch Childhood Oncology Group (DCOG, Amsterdam) or the Our Lady’s Children’s Hospital (Dublin). The median follow-up was 68 months (range 8–197 months), and was greater than 36 months for most patients without an event (114/139 = 82%). At the time of analysis, 156 of 230 patients were alive. All patients were treated according to similar protocols.

The validation cohort consisted of 304 patients from the COG: including 128 cases with an event and 189 patients without an event, with at least 36 months of follow-up. All laboratory analyses were done blinded to clinical and outcome data. All patients provided consent and were enrolled on at least one COG study, and all participating institutions had Institutional Review Board approval to take part in the COG studies. The FFPE validation cohort (43 samples from Gdansk, Poland and 33 samples from Valencia, Spain) contained 28 cases with an event and 47 cases without an event. Eighty percent (42/52) of the patients that survived had at least 36 months of follow-up.

This study was approved by the Ghent University Hospital Ethical Committee (EC2008/159).

miRNA expression profiling

Total RNA was extracted in different national reference laboratories using a silica gel-based membrane purification method (miRNAeasy kit, Qiagen) or by a phenol-based method (TRIzol reagent, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. As published earlier by Wang and colleagues, there is a high correlation in miRNA expression between protocols that are based on the phenol/chloroform procedure (6). Therefore, we do not expect an effect of RNA isolation method on miRNA expression results. A separate extraction protocol was applied to extract total RNA from the FFPE cohort (MasterPure RNA purification kit, Experion) according to manufacturers’ instructions. For fresh-frozen samples, reverse transcription (starting from 20 ng of total RNA) and miRNA expression profiling of 430 human miRNAs was done as described earlier (7). For FFPE samples, reverse transcription was done using 60 ng of total RNA. Samples from both validation cohorts (fresh frozen and FFPE material) were only profiled for the selected set of 25 prognostic miRNAs. Data normalization was done using the mean expression of 4 selected stably expressed reference miRNAs (hsa-miR-125a, hsa-miR-99b, hsa-miR-423, and hsa-miR-425) according to Mestdagh and colleagues (8). The data sets from the different centers were independently standardized (mean centered and autoscaled; ref. 9). miRNA expression data and clinical sample annotation are available in rdml-format (10; Supplementary File S1–3).

mRNA expression profiling

Expression analysis of 59 prognostic mRNA genes was done according to a procedure described elsewhere (2). In brief, qRT-PCR was used to measure 59 prognostic genes and 5 reference sequences. Real-time qPCR was done in a 384-well plate instrument (CFX384, Bio-Rad). Biogazelle’s qbasePLUS software was used for data analysis (normalization, error propagation, inter-run calibration). Results were standardized (mean centered and autoscaled). mRNA expression data are available in rdml-format (Supplementary File S1).

Statistical analysis

For data analysis, the tumor samples were divided into a training set and a test set. The training set consisted of 51 samples randomly selected from 2 patient subgroups with maximally divergent clinical courses: 24 low-risk patients with INSS stage 1, 2, or 4S without MYCN amplification and with progression-free survival (PFS) time of at least 1,000 days and 27 deceased high-risk patients older than 12 months at diagnosis with INSS stage 4 tumor (irrespective of the MYCN gene status) or with INSS stage 2 or 3 tumor with MYCN amplification.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to select the top 25 miRNA genes with prognostic relevance in NB, that is, the miRNAs with the lowest P value in a model testing miRNA expression levels (below or above the median expression) versus overall survival (OS).

The 25 miRNA and 59 mRNA expression signatures were built using the same training set, tested on the remaining 179 samples, and validated in a blind manner on the validation cohort of 304 COG samples.

For the test cohort, the R-language for statistical computing (version 2.9.0) was used to train and test the prognostic signature using the Prediction Analysis of Microarrays (PAM) method (11; Bioconductor MCR estimate package; 12), to evaluate its performance by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve and area under the curve (AUC) analyses (ROCR package), and for Kaplan–Meier survival analyses (survival package). Multivariate logistic regression analyses were done using PASW Statistics (version 18). Currently used risk factors such as age at diagnosis (≥12 months vs. <12 months), International Neuroblastoma Staging System (INSS) stage (stage 4 vs. not stage 4), and MYCN status (amplified vs. not amplified) were tested, and variables with P values less than 0.05 were retained in the model. Because an interaction between the signature and risk factors was not expected to occur, interaction terms were not included in the models. For ROC and multivariate analyses, only patients with an event and patients with sufficient follow-up time (≥36 months) if no event occurred were included, because 95%of events in NB are expected to occur within the first 36 months after diagnosis. Survival analysis was also done in high- and low-risk subgroups. Low-risk patients are patients with INSS stage 1 or 2 without MYCN amplification, whereas high-risk patients are patients with INSS stage 4 tumor (irrespective of the MYCNgene status) or with INSS stage 2 or 3 tumor with MYCN amplification.

A case–control study was set up to validate the signature in the COG cohort. This was done to ensure a sufficient number of events in each risk group—that is, to increase the power from what would have resulted from a random sample. Failure (cases) was defined as relapse, progression, or death from disease (PFS), and death (OS) within a 3-year follow-up period, and control defined as nonfailure in the first 3 years of follow-up. Controls and cases with complete data were selected in a 2:1 ratio to increase the sample size and power. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were done to determine whether the signature was a significant independent predictor after controlling for known risk factors. Statistical analyses were done with SAS (version 9). The final logistic regression model used 50 cases and 100 randomly selected controls with complete data for PFS and 37 cases and 74 randomly selected controls with complete data for OS.

Results

Establishment of a prognostic miRNA signature

To establish and train a prognostic miRNA signature, we used miRNA expression data from 24 low-risk patients with a long PFS time and 27 deceased high-risk patients. Using the top 25 miRNAs with the highest correlation with OS (Table 1), a 25 miRNA expression signature was built.

Table 1.

Twenty-five miRNAs in the prognostic signature

| Higher expressed in high-risk patients |

P value (univariate logistic regression) |

Higher expressed in low-risk patients |

P value (univariate logistic regression) |

|---|---|---|---|

| hsa-miR-17 | 6.01E-04 | hsa-miR-125b | 9.16E-04 |

| hsa-miR-18a | 4.72E-04 | hsa-miR-26a | 1.19E-03 |

| hsa-miR-18a* | 4.72E-04 | hsa-miR-190 | 9.14E-04 |

| hsa-miR-19a | 4.93E-04 | hsa-miR-30c | 1.47E-04 |

| hsa-miR-20a | 3.31E-04 | hsa-miR-326 | 1.39E-04 |

| hsa-miR-20b | 9.29E-04 | hsa-miR-488 | 2.04E-04 |

| hsa-miR-92a | 8.95E-05 | hsa-miR-500 | 8.09E-04 |

| hsa-miR-15b | 1.38E-04 | hsa-miR-628 | 7.61E-05 |

| hsa-miR-572 | 3.16E-04 | hsa-miR-485-5p | 9.00E-04 |

| hsa-miR-192 | 1.51E-03 | hsa-miR-542-3p | 9.04E-04 |

| hsa-miR-25 | 1.08E-04 | hsa-miR-204 | 2.45E-04 |

| hsa-miR-320 | 8.37E-04 | ||

| hsa-miR-345 | 5.43E-04 | ||

| hsa-miR-93 | 2.85E-04 |

Further in the text, we will refer to this signature as a molecular indicator for low or high risk separating patients with low versus high risk.

Validation of the prognostic 25-miRNA signature

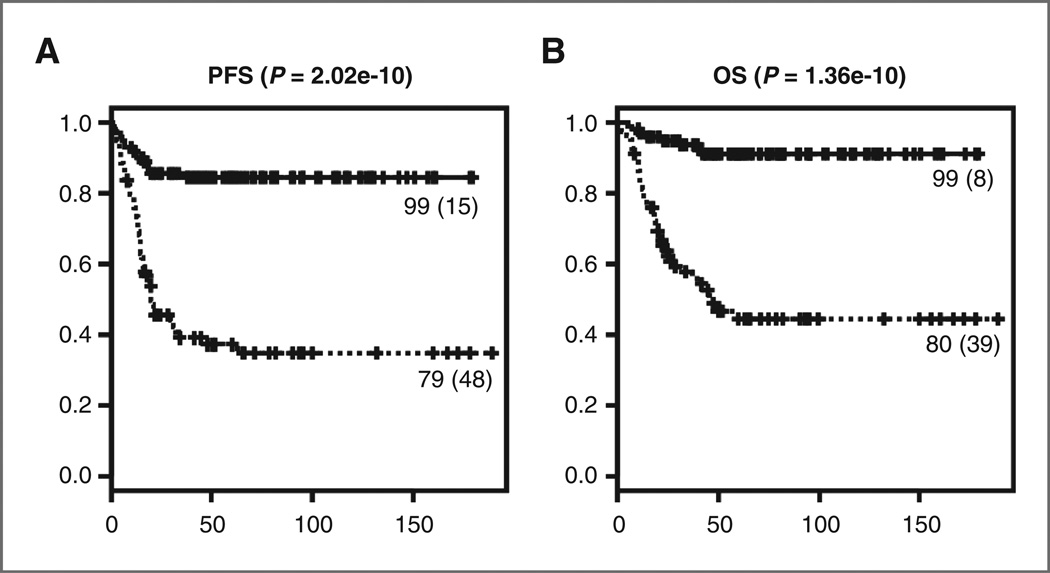

This 25 miRNA expression signature significantly distinguished the remaining 179 patients of a first cohort of NB patients with respect to PFS and OS (P < 0.0001; Fig. 1). PFS 5 years from the date of diagnosis was 84.3 (95% CI: 77.3–92.0) for the group of patients with a molecular indicator for low risk, compared with 37.2 (95% CI: 27.4–50.4) for the group of patients with a molecular indicator for high risk. The 5-year OS was 91.0% (85.1–97.2) and 44.5% (33.8–58.7) in the low and high molecular risk groups, respectively.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier and log-rank analysis for progression-free (A) and overall (B) survival of the test cohort. The number of events is indicated between brackets.

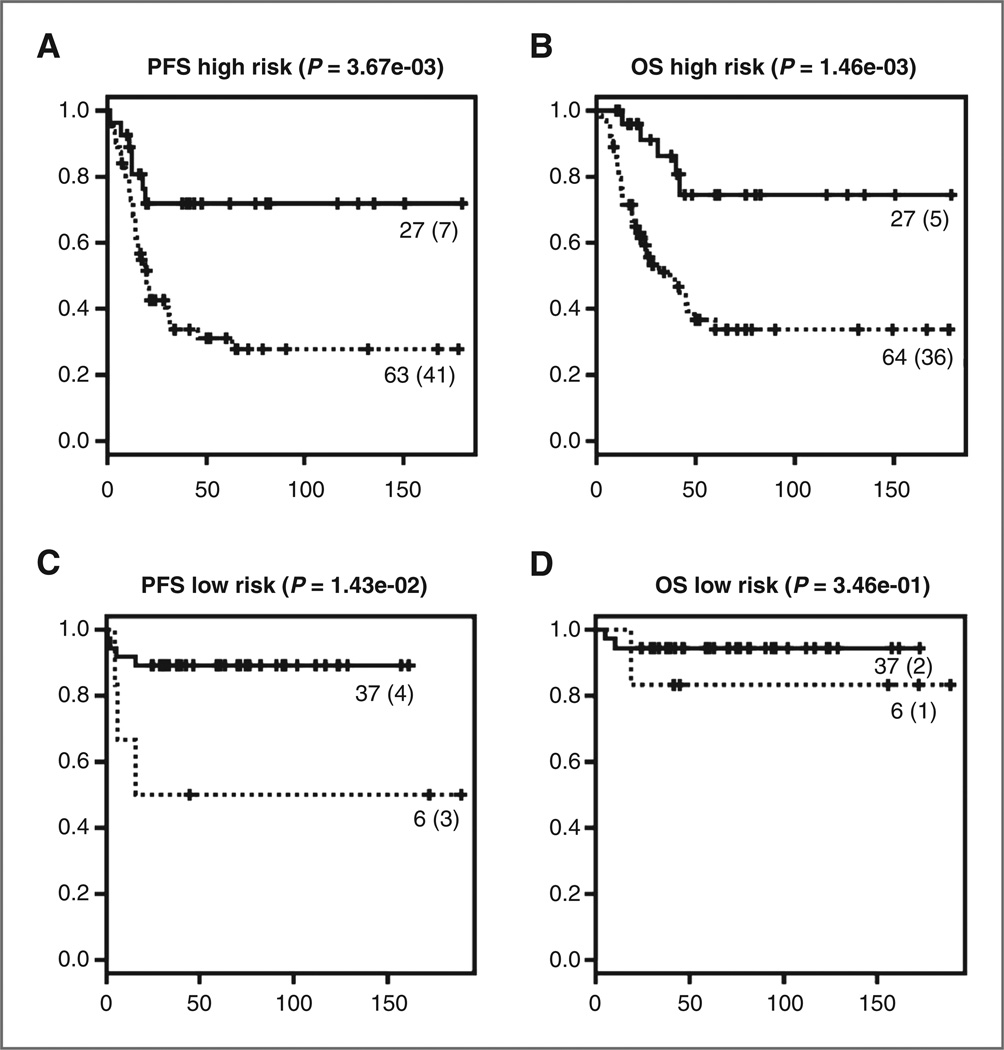

Subsequently, we tested the signature within the group of low-risk NB patients with localized disease treated with surgery alone or in combination with mild chemotherapy and within the commonly defined high-risk group based on the different current risk stratification systems (Europe, United States, and Germany; ref. 13). Patients with increased risk for disease progression or relapse could be identified in both current low- and high-risk groups (P = 0.014 and P = 0.0037, respectively). Although the signature was also useful in identifying those patients at increased risk for death in the current high-risk group (P = 0.0015), there was no difference in OS between patients with a molecular indicator for high and low risk in the current low-risk group (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier and log-rank analysis for progression-free (A, C) and overall (B, D) survival within the low-risk treatment group (C, D) and within the high-risk treatment group (A, B). The number of events is indicated between brackets.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis including the miRNA signature, MYCN status, age at diagnosis and INSS stage, revealed that the miRNA prognostic signature is an independent marker for both PFS and OS in the global cohort as well as in the high-risk subgroup (Table 2). Within the low-risk subgroup of patients the miRNA classifier was shown to be an independent predictor for PFS (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis in the first test cohort including all patients, the low-risk patients, and the high-risk patients

| Variable | P | OR | 95% CI on OR |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFS (all patients, N = 153)a | |||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low risk) | <0.0001 | 5,737 | 2,463–13,360 |

| Age at diagnosis (<>1 y) | 0.0018 | 4,261 | 1,715–10,587 |

| INSS stage (stage 4 vs. not stage 4) | 0.0082 | 3,191 | 1,350–7,541 |

| OS (all patients, N = 147)a | |||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low risk) | 0.00071 | 6.015 | 2.129–16.996 |

| Age at diagnosis (<>1 y) | 0.0015 | 7.633 | 2.184–26.679 |

| INSS stage (stage 4 vs. not stage 4) | <0.0001 | 9.274 | 3.143–27.368 |

| PFS (low-risk patients, n = 37)b | |||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low risk) | 0.050 | 6.750 | 0.995–45.769 |

| OS (low-risk patients, n = 37)b | |||

| No significant variables | |||

| PFS (high-risk patients, n = 68)a | |||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low risk) | 0.00073 | 9.286 | 2.549–33.832 |

| INSS stage (stage vs. not stage 4) | 0.060 | 5.571 | 0.929–33.409 |

| OS (high-risk patients, n = 63)a | |||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low risk) | 0.00068 | 10.286 | 2.681–39.462 |

Variables tested in the model were miRNA predictor, MYCN status, age, and INSS stage.

Variables tested in the model were miRNA predictor and age.

The probability that a patient will be correctly classified by the signature based on a ROC-curve analysis (AUC) was 78.1% (95% CI: 70.1–86.2) and 77.1% (69.1–85.1) for OS and PFS, respectively. The signature predicted OS with a sensitivity of 83.0% (39/47) and a specificity of 73.3% (74/101).

To validate the miRNA signature in a second completely independent patient cohort, 304 COG tumors were tested in a blind manner. The same signature as used for the test cohort identified COG patients who were at greater risk for progression or relapse. Multivariate logistic regression analysis including the miRNA signature, MYCN status, age, INSS stage, ploidy, International Neuroblastoma Pathology Classification (INPC), grade of differentiation, and mitosis karyorrhexis index (MKI) showed that the miRNA signature was an independent significant predictor for PFS (OR 3.861, 95% CI: 1.431–10.417). This was not the case for OS where the final logistic regression model involved only INSS stage and ploidy (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis in the second validation cohort

| Variablea | P | OR | 95% CI on OR |

|---|---|---|---|

| PFS (n = 113) | |||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low riskb) | 0.0077 | 3.861 | 1.431–10.417 |

| Grade (differentiating vs. undifferentiated and poorly differentiatedb) | 0.041 | 3.604 | 1.057–12.287 |

| OS (n = 78) | |||

| INSS stage (stage 4 vs. not stage 4b) | 0.0010 | 6.558 | 2.133–20.159 |

| Ploidy (diploid vs. hyperdiploidb) | 0.0071 | 4.629 | 1.516–14.136 |

Variables tested in the model were miRNA predictor, MKI, MYCN status, age, ploidy, INSS stage, and grade.

Indicates the reference level for each variable. The OR is the increased risk of an event in comparison with this reference level.

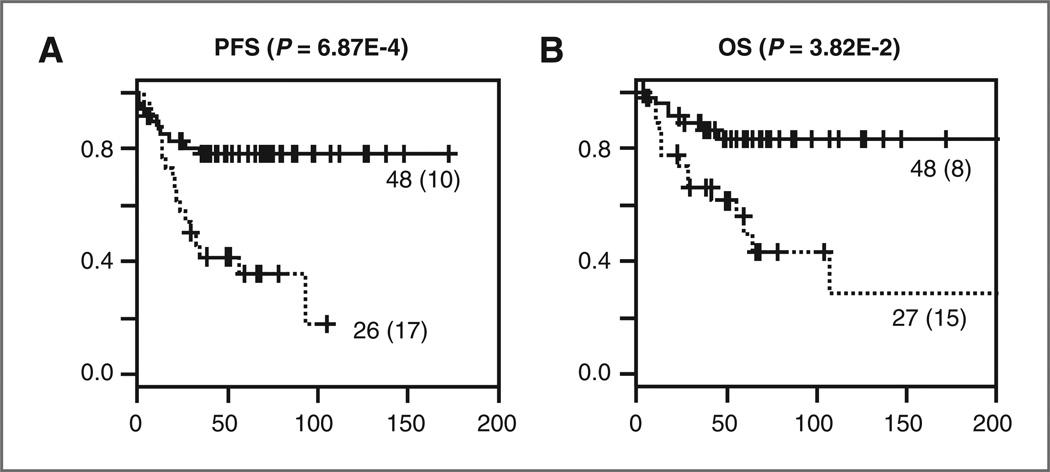

The miRNA signature was also validated in 75 FFPE samples. miRNA profiling was successful for 23 of the 25 miRNAs in these archived samples. Prediction analysis using a 23-miRNA signature revealed comparable results as with the fresh frozen material. The signature successfully distinguished patients with good and poor outcome (P < 0.01; Fig. 3). Given the rather small cohort of samples, we did not substratify the patients in low- and high-risk groups based on the applied treatment protocols. However, multivariate logistic regression analysis was applied including the miRNA signature, MYCN status, age at diagnosis, and INSS stage and showed that the signature is an independent predictor for both overall and event-free survival (Table 5).

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier and log-rank analysis for progression-free (A) and overall (B) survival of the FFPE validation cohort. The number of events is indicated between brackets.

Table 5.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis in the FFPE validation cohort

| Variable | P | OR | 95% CI on OR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFS (n = 65)a | ||||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low risk) | 2.43E-02 | 5.6 | 1.3 | 25.0 |

| INSS stage (stage 4 vs. not stage 4) | 1.47E-05 | 27.3 | 6.1 | 122.0 |

| OS (n = 65)a | ||||

| miRNA predictor (high vs. low risk) | 7.24E-03 | 7.6 | 1.7 | 33.4 |

| INSS stage (stage 4 vs. not stage 4) | 3.07E-05 | 23.3 | 5.3 | 102.3 |

Variables tested in the model were miRNA predictor, MYCN status, age, and INSS stage.

Comparison of the performances of the prognostic miRNA signature with the prognostic 59 mRNA signature

To establish the prognostic value of this 25-miRNA signature in relation to our recently published 59-mRNA signature (2), we compared performances and prognostic power through survival analysis and multivariate analysis including both miRNA and mRNA signatures along with other currently used risk factors on a common set of 122 test samples. Although, in a multivariate analysis, the 59-mRNA signature is an independent prognostic factor for both overall and PFS, the 25-miRNA signature is an independent prognostic factor for PFS but not for OS (Supplementary Table S1). Multivariate analysis including both signatures together with other currently used risk factors suggests that the 59-mRNA signature is an independent predictive factor for both overall and PFS whereas the 25-miRNA signature was not (Table 4). A possible explanation for this observation is the fact that the variation in mRNA expression was significantly higher than the variation in miRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. S1A, Mann–Whitney, P < 0.0001) in the tested patients, possibly allowing for a more robust separation between groups. When comparing the expression fold change between deceased patients and patients that are alive, we indeed observe a significantly higher fold change for mRNA genes as compared with miRNA genes (Supplementary Fig. S1B, Mann–Whitney, P < 0.0001). To exclude the possibility that we have established a suboptimal miRNA classifier, we compared its performance with that of 2 published miRNA classifiers (14, 15) and could show that both classifiers are less performant than the 25 miRNA classier, and hence also do not outperform the 59 mRNA classifier (Supplementary Table S1).

Table 4.

Final backward-selected logistic regression model testing the mRNA and miRNA classifiers and covariates in validation set 1 and validation set 2.

| P | OR | 95% CI on OR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Validation set 1 | |||

| PFS (N = 153)a | |||

| mRNA predictor (high vs. low riskd) | <0.0001 | 15.805 | 6.460–38.671 |

| Age at diagnosis (<>d1 y) | 0.016 | 3.254 | 1.245–8.507 |

| OS (N = 147)a | |||

| mRNA predictor (high vs. low riskd) | <0.0001 | 10.529 | 3.295–33.646 |

| Age at diagnosis (<>d1 y) | 0.0098 | 5.664 | 1.519–21.115 |

| INSS stage (stage 4 vs. not stage 4d) | 0.00086 | 6.897 | 2.215–21.475 |

| Validation set 2 | |||

| PFS (N = 113)b | |||

| mRNA predictor (high vs. low riskd) | 0.0010 | 4.926 | 1.908–12.658 |

| Grade (differentiating vs. undifferentiated and poorly differentiatedd) | 0.0350 | 3.637 | 1.095–12.081 |

| OS (N = 78)c | |||

| mRNA predictor (high vs. low riskd) | <0.0001 | 20.833 | 5.045–83.333 |

Variables tested in the model were age, stage, MYCN status, mRNA classifier, miRNA classifier.

Variables tested in the model and found not statistically significant were MYCN status, MKI, age, ploidy, the miRNA classifier, INSS stage, and grade.

Variables tested in the model and found not statistically significant were the miRNA classifier, age, MKI, MYCN status, and grade.

Indicates the reference level for each variable. The OR is the increased risk of an event in comparison to this reference level.

Discussion

Molecular risk classification of NB patients based on gene expression profiling is expected to contribute significantly to improved NB outcome prediction with the ultimate aim of tailoring the treatment to the severity of the disease. To this purpose, several mRNA gene expression classifiers were previously developed (2, 13, 16–21). Given the fact that a single miRNA, targeting several mRNAs, may have broader effects than a single mRNA and that miRNAs are less sensitive to RNA degradation than mRNAs, miRNA classifiers might present with certain advantages compared with mRNA classifiers. In this article, we successfully developed a miRNA signature that was subsequently validated in the largest NB series till now containing both fresh frozen and archived FFPE material. Importantly, we show the ability of the signature to identify patients at ultra-high risk with respect to disease outcome within the current high-risk NB group for which no clinical or genetic markers are available today.

To prove the robustness of a given signature, it should be validated under conditions that simulate the prospective broad clinical application of the assay and that reflect the various potential sources of assay variability, such as tissue handling, RNA extraction method, patient ethnicity, and treatment with other drugs. In this study, we conducted an external validation study on a completely independent cohort of COG patients whereby laboratory analyses were done blinded to clinical and outcome data. Also in this validation set, the signature was found to be a statistically significant independent risk predictor.

For the miRNA expression profiling, we used a high-throughput quantitative PCR-based stem-loop RT-primer method (7) along with a universally applicable data normalization method that had been successfully validated in our lab (8). Advantages of this method over the microarray technology are the higher cost-efficiency (definitely when measuring a 25-gene set), the shorter time to results, and the higher sensitivity (hence need of less input material). The use of a sample preamplification method enabled the maximization of the number of tumor samples available for this study through collaborative studies with international research laboratories; every laboratory could readily provide 100 ng of RNA. This is important, especially for pediatric cancers as biopsies are often very small and the material available limited. The use of a PCR-based method will definitely contribute to the development of a prognostic test that can be implemented in the clinic.

Another important aspect for implementation of assays in the clinic is the type of starting material. In contrast to fresh frozen material, FFPE material might be a better alternative as starting material, because establishing an FFPE specimen from a primary tumor is a standardized and straightforward procedure that is accessible to any lab in any country in the world. Moreover, FFPE samples are stable at room temperature and are easily storable. To address this issue, we evaluated our miRNA signature on 75 FFPE primary neuroblastoma tumors and successfully measured the expression of 23/25 miRNAs in the signature. The 23-miRNA signature was retrained on the initial test cohort of fresh frozen tumor samples and used to classify all FFPE samples. Importantly, the 23-miRNA signature allowed significant classification of patients with respect to overall and event-free survival in the FFPE cohort. This could not be achieved with the 59-mRNA signature due to extensive fragmentation of the mRNA from FFPE material (data not shown). Strikingly, although the miRNA signature was identified from and trained on fresh frozen tumor samples, it succeeded to classify FFPE samples. Not only does this underscore the robustness of the miRNA signature, it also implies that FFPE and fresh frozen tumor samples can be grouped into one cohort when evaluating prognostic miRNA signatures (i.e., when sample size of the patient cohort is too small to allow proper statistical analysis of a prognostic miRNA signature). To our knowledge, this is the first report of a prognostic signature for neuroblastoma that has been validated on FFPE specimens. Given the fact that FFPE samples are widely available for all cancer types, these samples provide a vast resource to develop and validate miRNA expression signatures.

A prognostic classifier can be clinically useful without the understanding of the mechanistic relationship of the genes or the interpretation of the meaning of the individual genes included in the expression signature and clear biological elucidation might be more difficult to achieve than accurate classification (22). However, the presence of many genes implicated in NB biology in our recently published prognostic 59-mRNA signature (2) suggests that among the 25 miRNAs in the present signature a significant portion may also be of direct biological relevance and may offer new opportunities for molecular therapy. As it is, all but one member of the mir-17–92 cluster is part of the prognostic signature. These miRNAs play a role in different tumorigenic pathways such as angiogenesis, cell adhesion and migration, cell-cycle regulation and proliferation, and negative regulation of apoptosis (23, 24). Furthermore, 16 of the 25 miRNAs are MYC/MYCN driven (25). Mir-26a and miR-125b are potential targets for therapy as they are highly expressed in all normal tissues, are known tumor suppressor miRNAs and candidates for replacement therapy (26). Gene ontology analysis of the 25 miRNAs using the miRNA body map (www.miRNAbodymap.org) showed a significant enrichment of GO terms for cell cycle, immune response, cell adhesion, and neuronal differentiation (Supplementary Table S2). Similar gene ontology classes are enriched in the 59 mRNA gene set pointing at common biological processes that are represented by these prognostic classifiers. Furthermore, target analysis showed that several of the 25 miRNAs target one or more of the 59 mRNA genes (Supplementary Table S3). Further functional studies are required to show the possible mechanistic relevance of some of the 25 miRNAs in NB pathogenesis. From these data, it is clear that the miRNAs in our signature not only allow for a significant classification of patients with respect to good or poor prognosis but also seem to be associated with multiple key cancer pathways and might therefore be interesting targets for therapeutic intervention.

In conclusion, the results obtained from this study clearly illustrate the power of miRNA expression analysis in the risk classification of NB patients using both fresh frozen and archived tumor material. Importantly, the applied method and signature are suitable for routine laboratory testing worldwide.

Translational Relevance.

Through one of the largest miRNA expression studies on patients, we have developed and validated a miRNA expression signature that is predictive for neuroblastoma patient outcome. This 25-miRNA signature allows to identify a cohort of neuroblastoma patients with increased risk for adverse outcome, independent of current clinical, and molecular risk factors. Importantly, this classifier conducts equally well in archived (formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded) material as in fresh frozen samples. Moreover, it allows to further stratify patients within the current high-risk population and as such identifies neuroblastoma patients that are at ultrahigh-risk. In a comparative analysis, we show that our reported 25-miRNA signature outperforms previously published miRNA signatures in terms of accurate patient classification. Our results were validated on 2 independent patient cohorts and indicate that the use of miRNA expression signatures can substantially improve risk stratification of neuroblastoma patients, especially within the current high-risk population. Improved patient classification is expected to result in more appropriate selection of therapeutic regimens.

Acknowledgments

We thank Els De Smet, Nurten Yigit, Gaëlle Van Severen, Justine Nuytens, Sander Anseeuw, and Liesbeth Vercruysse for their excellent technical assistance. We thank all members of the SIOPEN, GPOH, and COG for providing tumor samples or the clinical history of patients.

Grant Support

This work was supported by Ghent University Research Fund (BOF 01D31406; P. Mestdagh), the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (K. De Preter), the Belgian Kid’s Fund and the Fondation Nuovo-Soldati (J. Vermeulen), the FOD (NKP_29_014), the Fondation Fournier Majoie pour l’Innovation, the Belgian Federal Public Health Service, the Association Hubert Gouin « Enfance et Cancer », the Flemish League against Cancer, the Children Cancer Fund Ghent, the Belgian Society of Paediatric Haematology and Oncology, the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (grant number: G.0198.08), the Institute for the Promotion of Innovation by Science and Technology in Flanders, Strategisch basisonderzoek (IWT-SBO 60848), Children’s Oncology Group grants (U10 CA98413 and U10 CA98543) and the Instituto Carlos III,RD 06/0020/0102 Spain. This article presents research results of the Belgian program of Interuniversity Poles of Attraction, initiated by the Belgian State, Prime Minister’s Office, Science Policy Programming. We acknowledge the support of the European Community (FP6: STREP: EET-pipeline, number: 037260). R.L. Stallings was a recipient of grants from Science Foundation Ireland (07/IN.1/B1776), the Children’s Medical and Research Foundation, and the NIH (5R01CA127496).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary data for this article are available at Clinical Cancer Research Online (http://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/).

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

P. Mestdagh received commercial research support from Life Technologies. The other authors disclosed no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Vermeulen J, De Preter K, Mestdagh P, Laureys G, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. Predicting outcomes for children with neuroblastoma. Dis Med. 2010;10:29–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vermeulen J, De Preter K, Naranjo A, Vercruysse L, Van Roy N, Hellemans J, et al. Predicting outcomes for children with neuroblastoma using a multigene-expression signature: a retrospective SIOPEN/COG/GPOH study. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:663–671. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70154-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermeulen J, De Preter K, Lefever S, Nuytens J, De Vloed F, Derveaux S, et al. Measurable impact of RNA quality on gene expression results from quantitative PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e63. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Y, Stallings RL. Differential patterns of microRNA expression in neuroblastoma are correlated with prognosis, differentiation, and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2007;67:976–983. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulte JH, Schowe B, Mestdagh P, Kaderali L, Kalaghatgi P, Schlierf S, et al. Accurate prediction of neuroblastoma outcome based on miRNA expression profiles. Int J Can J Int du Cancer. 2010;127:2374–2385. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang WX, Wilfred BR, Baldwin DA, Isett RB, Ren N, Stromberg A, et al. Focus on RNA isolation: obtaining RNA for microRNA (miRNA) expression profiling analyses of neural tissue. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2008;1779:749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mestdagh P, Feys T, Bernard N, Guenther S, Chen C, Speleman F, et al. High-throughput stem-loop RT-qPCR miRNA expression profiling using minute amounts of input RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:e143. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mestdagh P, Van Vlierberghe P, De Weer A, Muth D, Westermann F, Speleman F, et al. A novel and universal method for microRNA RT-qPCR data normalization. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-6-r64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willems E, Leyns L, Vandesompele J. Standardization of real-time PCR gene expression data from independent biological replicates. Anal Biochem. 2008;379:127–129. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefever S, Hellemans J, Pattyn F, Przybylski DR, Taylor C, Geurts R, et al. RDML: structured language and reporting guidelines for real-time quantitative PCR data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:2065–2069. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tibshirani R, Hastie T, Narasimhan B, Chu G. Diagnosis of multiple cancer types by shrunken centroids of gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6567–6572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082099299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ruschhaupt M, Huber W, Poustka A, Mansmann U. A compendium to ensure computational reproducibility in high-dimensional classification tasks. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol. 2004;3 doi: 10.2202/1544-6115.1078. Article 37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Preter K, Vermeulen J, Brors B, Delattre O, Eggert A, Fischer M, et al. Accurate outcome prediction in neuroblastoma across independent data sets using a multigene signature. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Can Res. 2010;16:1532–1541. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bray I, Bryan K, Prenter S, Buckley PG, Foley NH, Murphy DM, et al. Widespread dysregulation of MiRNAs by MYCN amplification and chromosomal imbalances in neuroblastoma: association of miRNA expression with survival. Plos One. 2009;4:e7850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schulte JH, Schowe B, Mestdagh P, Kaderali L, Kalaghatgi P, Schlierf S, et al. Accurate prediction of neuroblastoma outcome based on miRNA expression profiles. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2374–2385. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asgharzadeh S, Pique-Regi R, Sposto R, Wang H, Yang Y, Shimada H, et al. Prognostic significance of gene expression profiles of metastatic neuroblastomas lacking MYCN gene amplification. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1193–1203. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oberthuer A, Berthold F, Warnat P, Hero B, Kahlert Y, Spitz R, et al. Customized oligonucleotide microarray gene expression-based classification of neuroblastoma patients outperforms current clinical risk stratification. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:5070–5078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oberthuer A, Hero B, Berthold F, Juraeva D, Faldum A, Kahlert Y, et al. Prognostic impact of gene expression-based classification for neuroblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3506–3515. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.3367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohira M, Oba S, Nakamura Y, Isogai E, Kaneko S, Nakagawa A, et al. Expression profiling using a tumor-specific cDNA microarray predicts the prognosis of intermediate risk neuroblastomas. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:337–350. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schramm A, Schulte JH, Klein-Hitpass L, Havers W, Sieverts H, Berwanger B, et al. Prediction of clinical outcome and biological characterization of neuroblastoma by expression profiling. Oncogene. 2005;24:7902–7912. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei JS, Greer BT, Westermann F, Steinberg SM, Son CG, Chen QR, et al. Prediction of clinical outcome using gene expression profiling and artificial neural networks for patients with neuroblastoma. Can Res. 2004;64:6883–6891. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simon R. Roadmap for developing and validating therapeutically relevant genomic classifiers. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:7332–7341. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dews M, Homayouni A, Yu D, Murphy D, Sevignani C, Wentzel E, et al. Augmentation of tumor angiogenesis by a Myc-activated microRNA cluster. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1060–1065. doi: 10.1038/ng1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fontana L, Fiori ME, Albini S, Cifaldi L, Giovinazzi S, Forloni M, et al. Antagomir-17-5p abolishes the growth of therapy-resistant neuroblastoma through p21 and BIM. Plos One. 2008;3:e2236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mestdagh P, Fredlund E, Pattyn F, Schulte JH, Muth D, Vermeulen J, et al. MYCN/c-MYC-induced microRNAs repress coding gene networks associated with poor outcome in MYCN/c-MYC-activated tumors. Oncogene. 2010;29:1394–1404. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kota J, Chivukula RR, O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Montgomery CL, Hwang HW, et al. Therapeutic microRNA delivery suppresses tumorigenesis in a murine liver cancer model. Cell. 2009;137:1005–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]