Abstract

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common potentially lethal monogenic disorder, with more than 12 million cases worldwide. The two causative genes for ADPKD, PKD1 and PKD2, encode protein products polycystin-1 (PC1) and polycystin-2 (PC2 or TRPP2), respectively. Recent data have shed light on the role of PC1 in regulating the severity of the cystic phenotypes in ADPKD, autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD), and isolated autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD). These studies showed that the rate for cyst growth was a regulated trait, a process that can be either sped up or slowed down by alterations in functional PC1. These findings redefine the previous understanding that cyst formation occurs as an “on-off” process. Here we review these and other related studies with an emphasis on their translational implications for polycystic diseases.

Keywords: polycystic kidney disease, polycystic liver disease, polycystin-1 dosage, cyst progression, protein biogenesis, chaperone therapy

Polycystic kidney disease and related cystic diseases

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) (see Glossary) is part of a spectrum of inherited cystic diseases that also includes autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD), autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) and an expanding group of recessively inherited syndromic ciliopathies (see Table 1). ADPKD is the most common monogenic disorder that can lead to kidney failure with an incidence of 1 in 600–800 live-births, and affecting 600,000 people in the US [1]. In most cases, ADPKD manifests during adult life and is characterized by extensive cystic enlargement of both kidneys. The two causative genes for ADPKD, PKD1 located on chromosome 16p13.3 and PKD2 located on chromosome 4q21, were isolated by positional cloning and their respective protein products, polycystin-1 (PC1) and polycystin-2 (PC2 or TRPP2) [2][3], have been extensively studied. PC1 and PC2 are integral membrane proteins, with PC1 having structural and functional features suggestive of receptor function, whereas as PC2 is a Ca2+-permeable cation channel belonging to the transient receptor potential (TRP) sensory channel family. Together, PC1 and PC2 are thought to function as a Ca2+-permeable receptor-channel complex [4].

Table 1.

Genes and protein products involved in dominant and recessive polycystic diseases.a

| Disease (OMIM) | Gene | Key clinical features | Protein products | Pathogenetic mechanism of cyst formation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADPKD MIM 173900 |

PKD1 | Kidney and bile duct cysts | Polycystin-1/Ciliary receptor protein involved in mechanosensation or chemosensation | Two-hit model combined with a PC1 dosage- dependent mechanism |

| ADPKD MIM 173900 |

PKD2 | Kidney and bile duct cysts | Polycystin-2/Ciliary and endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein functioning as a non- selective cation channel | Two-hit model combined with a PC1 dosage-dependent mechanism |

| ARPKD MIM 263200 |

PKHD1 | Fusiform collecting duct dilatations, liver cysts and congenital hepatic fibrosis | Fibrocystin/Polyductin/Ciliary, plasma membrane protein | Homozygous inactivation, oriented cell division defects, PC1 dosage- dependent mechanism |

| ADPLD MIM 174050 |

PRKCSH | bile duct cystic dilatations | GIIβ/ER luminal protein/N-glycan glucose trimming enzyme as part of the calnexin-calreticulin cycle of protein folding | Two-hit model combined with a PC1-dosage dependent mechanism |

| ADPLD MIM 174050 |

SEC63 | bile duct cystic dilatations | SEC63/ER transmembrane protein involved co-translational protein translocation together with SEC61 | Two-hit model combined with a PC1-dosage dependent mechanism |

Abbreviations: OMIM, Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man; ADPKD, Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease; MIM, Mendelian Inheritance in Man; PC1, polycystin-1; PKD1/2, polycystic kidney disease gene 1/2; PKHD1, Polycystic Kidney and Hepatic Disease 1 Gene; ARPKD, Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease; ADPLD, Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Liver Disease; PRKCSH, Protein Kinase C substrate 80K-H; GIIβ, beta subunit of glucosidase II; ER, endoplasmic reticulum.

Cyst formation in ADPKD requires a germ line mutation in either PKD1 or PKD2. Although every cell in the body carries this germ line mutation, cyst formation is focal, arising only from a minority of kidney tubules and hepatic bile ducts. This apparent paradox has been explained by the occurrence of somatic second hit mutations in the remaining normal copy of the affected gene, leading to recessive loss of function in a subset of tubule epithelial cells that actually give rise to cysts in adult tissues [5–10]. While somatic second hit mutations are a generally accepted mechanism for human ADPKD, additional factors have been shown to influence the extent of cyst formation. Mouse and human studies have shown that these additional factors include non-cell autonomous effects on cells still expressing polycystins [11], the developmental timing of PKD1 inactivation [12], and milder effects of PC1 hypomorphic mutations compared to complete loss of function [13–19]. Reduction in functional PC1 dosage has been shown to underlie expression of the ADPLD and ARPKD phenotypes in which the extent of tubule dilation and cyst formation is inversely correlated with the level of PC1 function [20]. These studies also suggest that sensitivity to PC1 dosage differs between bile ducts and kidney tubules, and between the different segments of the nephron. The following review focuses on the common role of PC1 dosage in the cyst progression in ADPKD, ARPKD, and ADPLD.

Genes and proteins

Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD)

ADPKD is characterized by the formation and growth of multiple fluid-filled kidney cysts that progress over decades with attendant inflammation and fibrosis. Consequent loss of functional nephrons leads to end-stage renal disease in over 50% of affected individuals by late adulthood. A major extrarenal manifestation of ADPKD is polycystic liver disease which does not affect liver function, but can lead to symptoms related to mass effects when significant liver enlargement occurs.

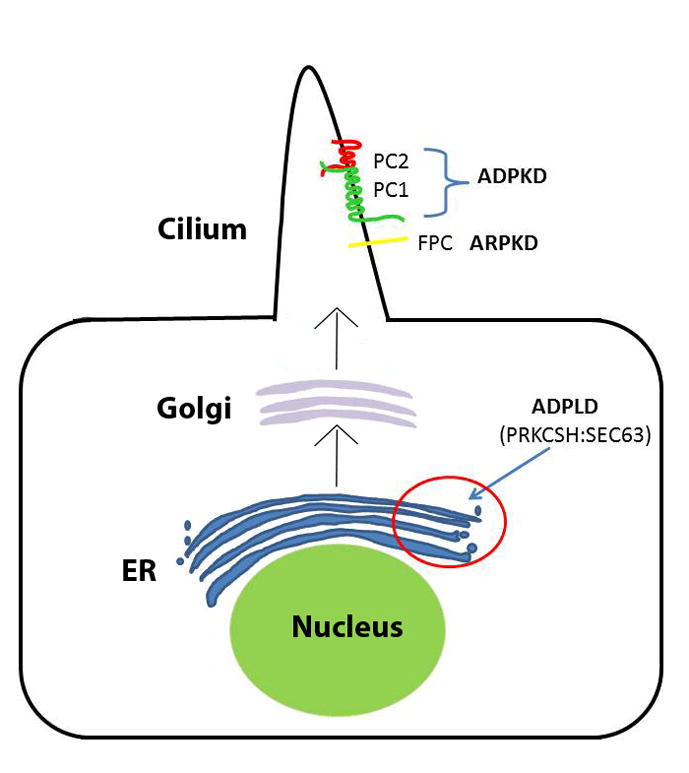

There are two known genes mutated in ADPKD: PKD1 and PKD2. PKD1 mutations account for roughly 85% of cases ascertained by clinical presentation. The PKD1 gene product, PC1, is a very large protein consisting of 4302 amino acids with a 3074 amino acid extracellular amino-terminus, 197 amino acid cytosolic carboxy-terminus and eleven transmembrane domains [2] [21]. PC1 is likely expressed in most nephron segments, although expression at the tissue level has been difficult to determine due to very low protein levels. At the subcellular level, PC1 is localized to the primary cilium on the apical surface of epithelial cells (Figure 1) [22] [4], in addition to other reported locations in the cell such as the lateral membrane at sites of intercellular adhesion [23] and at desmosomes [24]. Cilia are linked to a wide range of cystic diseases and the central role for cilia in many human diseases has been thoroughly reviewed [25] [26]. Defects in proteins localized in the ciliary membrane, axoneme and basal body complex are linked with a wide clinical spectrum of diseases, collectively termed “ciliopathies.” Clinical findings in ciliopathies include cyst formation in kidney tubules, bile and pancreatic ducts, retinal degeneration and retinitis pigmentosa, situs inversus (incorrect left-right body axis), anosmia (loss of sense of smell), and hydrocephalus [27].

Figure 1.

Schematic view of the relevant subcellular localization of the proteins involved in Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease (ADPKD), Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (ARPKD), and Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Liver Disease (ADPLD). The two ADPLD proteins glucosidase IIβ (GIIβ) and Sec63p are localized in the ER and are involved in protein translocation (Sec63p) and folding (GIIβ). The proteins associated with ADPKD, polycystin-1 (PC-1, encoded by PKD1) and polycystin-2 (PC-2, encoded by PKD2), in addition to the ARPKD protein fibrocystin/polyductin, (FPC, encoded by PKHD1) are all ciliary transmembrane proteins which need to go through the co-translational translocation pathway (see Figure 2) in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), which Sec63p and GIIβ are integral members of, in order to be properly folded and trafficked to Golgi and onto their final physiological destination, the primary cilia.

PKD2, the gene mutated in 15% of clinically ascertained polycystic kidney disease cases, encodes PC2 [28]. PC2 has been described as a non-selective calcium permeable cation channel belonging to the transient receptor potential polycystic (TRPP) subfamily of TRP cation channels [28]. PC2 is an integral membrane protein with 6 transmembrane segments, and both the amino and carboxy termini face the cytoplasmic compartment [29] [30]. PC2 contains several trafficking motifs: the RVxP motif at the amino terminus of PC2 is necessary and sufficient for the ciliary location of the protein [31], whereas a region at the carboxy-terminus may restrict the membrane location of PC2 to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and cilia. In the kidney, PC2 is found in all nephron segments, with the exception of the thin loops of Henle and the glomerulus.

The working model of polycystin function is that PC1 functions as a mechanosensor or chemosensor at the primary cilium and regulates the activity of the PC2 calcium channel [32] [33] [34].. Beyond that, a myriad of cellular pathways have been implicated as effector pathways in ciliary and cystic diseases, including planar cell polarity (PCP), Wnt, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), cyclic adenosime monophosphate (cAMP), G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR), cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) cellular Ca2+, and the cell cycle (reviewed in [35], [36]). Extensive evidence that cAMP promotes cyst growth has led to the hypothesis that loss of functional PC1 at the cilium results in reduced cellular calcium signaling [4] that in turn results in increased adenylate cyclase and decreased phosphodiestarase activity, leading to elevated intracellular cAMP. Among the effects of increased cAMP in cystic epithelium are increased protein kinase A activity, which can result in increased cell proliferation and deregulated fluid secretion, features associated with cyst growth [36]. Lacking through all of these proposed functional pathway hypotheses is an understanding of the relationship of polycystins with other ciliary component proteins and a clear definition of the direct role of polycystin signaling within cilia.

A recent study based on genetic manipulation of polycystin and cilia in mutant mice has the potential to significantly recalibrate the concepts about the interrelationship between polycystin and cilia function [37]. Based on the observation that inactivation of the entire cilium structure, or of a single cilium membrane component protein such as polycystin, both give rise to cyst formation in the kidney, the study asked what the effects of concomitant inactivation of cilia and polycystins would be. Cilia were ablated by mutation of intraflagellar transport protein encoding genes that are required for the formation and maintenance of cilia. Surprisingly, inactivation of cilia in the setting of absent polycystins resulted in much milder progression of polycystic disease than was seen with inactivation of polycystin alone [37]. In the models used, polycystin protein levels in the kidney epithelial cells were attenuated before the disappearance of cilia and the severity of the polycystic disease was directly related to the duration of the interval between the initial loss of polycystins and the subsequent involution of cilia. These findings define the existence of a novel cilia dependent pathway promoting cyst growth that requires the presence of intact cilia devoid of polycystins to produce kidney cysts [37]. The most straightforward interpretation of these findings is that polycystins provide baseline tonic inhibition of this cilia dependent signal. As part of normal physiological function of polycystins, this inhibition is reduced in a regulated manner based on mechanical flow or ligand mediated regulation of PC1. The normal in vivo function of these pathways is uncertain, but one hypothesis may be that they regulate renal tubular lumen diameter by subtle changes in tubule cell morphology through regulation of the actin cytoskeleton (e.g., transitioning cells from more columnar to more cuboidal shaped). Based on these studies we propose that polycystins act as suppressors of an as yet undefined cilia dependent pathway, and that discovery of this latter pathway will provide insight into novel kidney tubule homeostatic mechanisms as well as provide a universally applicable target for reducing cyst growth in both the kidney and liver in ADPKD.

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD)

Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) is a rare pediatric disease with an incidence of approximately 1 in 20,000 births. ARPKD is characterized by fusiform dilation of the collecting ducts in the kidneys, and biliary ductal ectasia leading to congenital hepatic fibrosis of the portal tracts in the liver, and is associated with a high level of morbidity and mortality in affected individuals. PKHD1 is the only known locus responsible for ARPKD [38] [39]. In ARPKD, there is a genotype-phenotype correlation, in that the presence of two completely inactivating PKHD1 mutations results in a more severe clinical outcome associated with perinatal mortality. Patients with at least one hypomorphic missense mutation have a more juvenile presentation, suggesting that that a subset of missense changes result in reduced rather than absent function of the PKHD1 gene product [40][41].

PKHD1 encodes the protein fibrocystin (FPC), which is a large 4,074 amino acid complex integral membrane protein. FPC contains a signal peptide, a predicted glycosylated extracellular amino-terminus subsuming most of the protein (3858 amino acids), a single transmembrane domain and a 192 amino acid cytoplasmic tail [39][38][42]. FPC localizes in the cortical and medullary collecting ducts and thick ascending limbs of the loop of Henle in the kidney [43]. Elsewhere, FPC is expressed in the biliary and pancreatic tracts, and in salivary ductal epithelia. FPC is expressed in the cilia and apical membrane of renal tubular and bile duct cells [44][45][46][47].

FPC is involved in regulation of planar cell polarity (PCP), a process in which specialized structures are distributed in an oriented manner within the plane of the epithelial sheet. Some examples of planar cell polarity include the scales of fish being oriented in the same direction, and similarly the feathers of birds, the fur of mammals, and the cuticular projections on the bodies and appendages of flies and other insects [27]. Complete loss of FPC leads to loss of oriented cell division (OCD), a manifestation of PCP which allows oriented elongation of kidney tubules while maintaining a constant luminal diameter during postnatal growth of the organism [48, 49][36][50]. Loss of OCD following inactivation of Pkhd1, however, is not sufficient to initiate kidney cyst formation in mouse models of ARPKD suggesting that additional functional factors play a critical role in ARPKD [49].

Autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD)

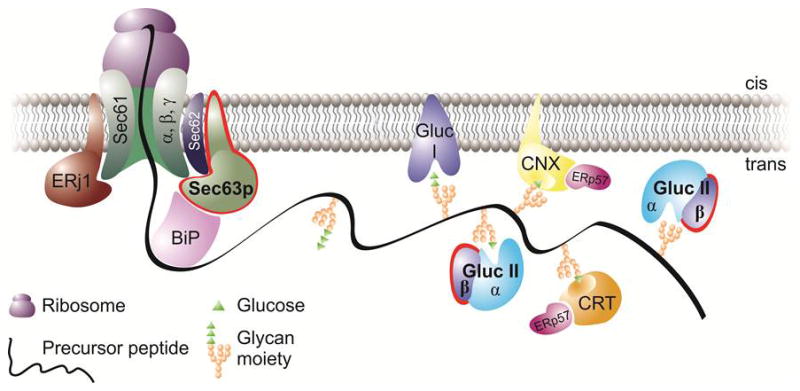

Isolated ADPLD without kidney cysts manifests a clinical phenotype of biliary cystic malformations that are indistinguishable from those occurring in ADPKD. The two known disease causative genes for ADPLD are PRKCSH and SEC63, which encode for non-cilial, ER-localized proteins involved in protein biogenesis and post-translational modification [51][52][53][54] (Figure 2). PRKCSH encodes the non-catalytic β-subunit of glucosidase II (GIIβ) [55]. Glucosidase II acts in the calnexin-calreticulin cycle of folding and quality control for integral membrane and secreted proteins passing through the ER translocon [56]. Computational analysis predicts that GIIβ contains a signal peptide for translocation across the ER membrane, a low density lipoprotein domain class A (LDL-A), two EF-hand (named after the E and F helices of parvalbumin where the calcium binding domain is located) domains, a glutamic-acid-rich region, a mannose-6-phosphate receptor domain and a conserved C-terminal HDEL amino acid sequence for ER luminal retention.

Figure 2.

The co-translational translocation pathway highlighting (red contour) the two ADPLD proteins, Sec63p and GIIβ. At this stage, the precursor protein (e.g. PC1) is threaded through the translocon, with its central subunit, the Sec61 complex, and the auxiliary subunits that are present in the membrane (Sec63 and ERdj1/Erj1). Via their DnaJ domains, Sec63p and Erdj1 provide a link to the ATPase cycle of the luminal chaperone BiP. Downstream of Sec63p, GIIβ is involved (as the regulatory subunit of the glucose trimming enzyme, glucosidase II) in glucose trimming, which takes place as part of the calnexin-calreticulin cycle. Cystic proteins such as PC1 have to go through this pathway to achieve their final, functional cellular location (the primary cilia). Defects along this pathway may affect both the translocation (due to Sec63p inactivation) or glucose trimming/folding (via GIIβ) of cystic proteins as described in [20].

Human SEC63p is an 83-kDa protein [57] that is predicted to span the ER membrane three times. It contains an ER luminal N-terminus, a cytoplasmic C-terminus with a coiled-coil region and a luminal DnaJ domain between the second and third transmembrane spans. SEC63p associates with the SEC61/62 ER translocon which forms the hydrophilic pore in the ER membrane through which the nascent integral membrane or secreted polypeptides are translocated. SEC63p is responsible for the tight binding of the ribosome to the ER membrane during the co-translational transport process [58]. Two recent biochemical studies have highlighted the role of SEC63p in the initial phase of co-translational protein transport into the ER in a precursor-specific manner: SEC63p functions in determining substrate specificity in the initial insertion of certain precursors into the SEC61 translocon complex [59], and has a role in determining the steady-state quantity of multi-spanning membrane proteins [60]. SEC63p recruits the Hsp70 homolog binding immunoglobulin protein (BiP), to the translocation site via its DnaJ-like domain and provides the necessary adenosine triphosphatase (ATPase)activity to cycle BiP to the adenosine di-phosphate (ADP)-bound high affinity peptide interaction state [61][62]. PRKCSH and SEC63 are involved in the same functional pathway of co-translational protein translocation and maturation [54] [63] [64] and defects associated with either of them have a significant impact on the biogenesis of polycystic disease associated proteins [20]. Along these lines it would be interesting to examine the association between Prkcsh/Sec63 deletion and the upregulation of the unfolded protein response (UPR) in the context of murine ADPLD models and/or ADPLD patients.

Mechanisms of cyst formation

Following the discovery of the two ADPKD causative genes, PKD1 and PKD2, the next significant step forward in understanding the underlying mechanisms came from the discovery that cyst lining cells derived from human cystic kidney and liver tissues display somatic second hit mutations which lead to homozygous inactivation of the respective genes in a cellular recessive mechanism [5][8][7][9]. Demonstration of a causal connection between somatic inactivation of Pkd2 and cyst formation came from a modified allele in the Pkd2WS25 mouse line that is prone to genomic rearrangement converting Pkd2WS25 to either a null or true wild type allele [6]. Somatic conversion to a null allele correlated with cyst formation in the kidney, liver and pancreas showing that somatic loss of Pkd2 is sufficient for cyst formation [6][14].

Similar to ADPKD, the mechanism of cyst formation in ADPLD involves somatic second hit mutations at either the PRKCSH and SEC63 loci [20][65][66]. In mice, conditional tissue specific inactivation of either gene triggered liver and kidney cyst formation whereas age-matched heterozygous mice maintained normal organ architecture [20]. Genetic and biochemical studies showed that homozygous loss of either Prkcsh or Sec63 affects the dosage of the functional PC1/PC2 complex, leading to cyst formation [20]. The implications for these findings are discussed later.

While the second hit hypothesis is the generally accepted mechanism for ADPKD, other mechanisms and factors that may influence the rate of cyst growth have been experimentally demonstrated in mouse models. Chimeric transgenic mice that were made by combining wild-type morulae containing a lacZ lineage tracer with Pkd1−/− null embryonic stem cells developed cysts whose size was dependent on the relative contribution of Pkd1−/− cells to the chimeras [11]. The cysts displayed a mosaic pattern with both null and wild-type Pkd1 cells. Over time null cells dominated the entire cystic area by increased proliferation, while also inducing apoptosis in the wild-type cells via a c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) mediated pathway [11].

Cyst formation resulting from trans-heterozygous somatic mutations involving PKD1 and PKD2 has also been described [67]. The effect of trans-heterozygosity on the overall cyst formation appears to be small, and not enough to explain the cystic burden as it occurs in ADPKD. For example, individuals with bilineal transmittance of PKD1 and PKD2 mutations [13] or trans-heterozygous mice [14] display increased polycystic kidney disease, but the overall severity is within the range consistent with additive or small extra-additive effects of single gene mutations.

The timing of Pkd1 inactivation significantly impacts the rate of cyst growth. In studies where temporally controlled inducible Cre-recombinase expression was used to knock out conditional Pkd1 alleles at different developmental time points, early inactivation during ongoing kidney development resulted in a fast rate of cyst growth. In contrast later inactivation in post-developmental or adult kidneys resulted in slower cystic development [12][68]. The transition from rapid to slower cyst growth correlated with a switch in gene expression occurring around postnatal day 12 in the mouse, which may be linked to a different proliferative potential of the kidney at early versus late stages of development [12]. These findings in the developing kidney are complemented by further studies showing that ischemia-reperfusion-dependent injury response, which has a proliferative component, increases the rate of cyst growth in adult mice [69][70][71][72]. On the other hand, a recent study found that increased background proliferation induced by a Cux-1 transgene did not promote cyst growth in a model of polycystic disease based on loss of cilia [73]. This suggests that the underlying background proliferative potential is important but not sufficient for cyst growth in adult models of polycystic kidney disease. The severity of ADPKD is likely to be modulated by factors including the timing and degree of gene and protein inactivation, the occurrence of local injury and the specific proliferative response that these changes engender.

PC1 dosage in ADPKD

PC1 dosage has sporadically been described to be a modulator of cystic disease. Lantinga van-Leeuwen and colleagues [15] were the first to report that reduced levels of PC1 could lead to the clinical features of ADPKD without complete inactivation. The authors showed that the intronic insertion of a neomycin cassette into Pkd1 had a profound effect on splicing efficiency, resulting in a mixture of mutant and wild-type sequences. Approximately 15–20% of the Pkd1 transcripts were correctly spliced in the majority of the homozygous Pkd1nl/nl mice. These hypomorphic mice escape the embryonic lethality seen in complete knock-out mice where PC1 is totally absent. Although the hypomorphic Pkd1nl/nl mice survive, they develop severe cystic kidneys, with cysts originating from collecting duct, thick ascending limb and distal tubules. Another study by Jiang et al. [16] provided evidence that diminished expression of native PC1 is sufficient to induce renal cystic lesions of ADPKD. The authors showed that the intronic insertion of the neomycin cassette in reverse orientation into Pkd1 interfered with the transcription and/or splicing machinery, resulting in low (around 20%) but not completely absent Pkd1 expression. Only wild-type Pkd1 transcript and protein were detected in either heterozygous Pkd1L3/+ or homozygous Pkd1L3/L3 mice with no mutant transcript with the neomycin cassette present. The Pkd1L3/L3 mice developed a severe cystic phenotype around P30, with cysts forming exclusively from the collecting duct, thick ascending limb, and distal tubules. A similar follow-up study used microRNA technology to knockdown the Pkd1 transcript [18]. Based on these studies one can hypothesize that while 50% reduction in PC1 levels, as occurs in true heterozygote ADPKD patients, does not lead to frank cyst formation, 80% reduction may be sufficient to trigger a polycystic phenotype. What remains unknown is whether the 50% reduction in PC1 in ADPKD patients affects tubular morphology in more subtle ways, perhaps by increasing luminal diameter without unchecked expansion leading to cysts.

A recent study showed that a knock-in mouse model, Pkd1RC/RC, mimicking a naturally occurring PKD1 variant p.R3277C [74], developed gradual cystic disease over 1 year, while the Pkd1RC/null mice had more rapidly progressive disease [19]. These observations, coupled with biochemical data showing that the p.R3277C mutation leads to a decrease in the steady-state levels of PC1 that can be partially rescued in a temperature sensitive manner, point to the importance of PC1 dosage in the modulation of cyst severity. Conversely, high copy number (>30) Pkd1 transgenic lines have reported the presence of kidney cysts [75] suggesting that it is not only reduced dosage of PC1 that may lead to cysts. Very high levels of PC1 overexpression may generate cysts possibly by disrupting the stoichiometry of the PC1/PC2 complex, thereby impacting it signaling function. Overall, all these data imply that PC1 dosage is a bona fide mechanism of cyst formation in both mouse and human ADPKD.

PC1 dosage in ADPLD

New findings have defined the genetic interactions between ADPKD, ADPLD and ARPKD, and have brought into the spotlight the central importance of PC1 dosage across this spectrum of human polycystic diseases [20, 76]. Pkd1 and Pkd2 interact genetically with both Prkcsh and Sec63, respectively encoding GIIβ or Sec63p. The background levels of the polycystin proteins in mouse models of ADPLD were reduced by introducing a heterozygous null allele for the respective Pkd gene or increased by introducing low copy number bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) transgenes expressing either Pkd gene. The dosage of PC1 protein proved to be the ultimate arbiter in the severity and timing of cyst formation following recessive tissue specific loss of GIIβ or Sec63p. In the absence of GIIβ or Sec63p, decreasing expression of Pkd1 using a heterozygous Pkd1+/− background exacerbated the cystic phenotype. Increasing expression of Pkd1, using a 3-copy Pkd1F/H-BAC transgene, ameliorated the cystic phenotype. While reduction of Pkd2 dosage showed an intermediate level of exacerbation in polycystic disease, the rescue of the cystic phenotype was not seen when Pkd2 dosage was increased using a Pkd2-BAC transgenic. It has to be noted here that PC1 modulated the cystic phenotype when PC2 was present. In the complete absence of PC2, overexpression of PC1 did not have any effect on cyst formation, suggesting that the functional PC1/PC2 complex is strictly required for the rescue to take place. These findings define PC1 as the rate-limiting component of the polycystin complex in cyst formation in ADPLD.

These genetic studies were correlated with biochemical experiments revealing that deletion of GIIβ or Sec63p leads to reduction in the steady-state expression, post-mid Golgi and ciliary trafficking, of PC1, as well as other integral membrane proteins. The ADPLD gene products, via their role in the biogenesis of PC1, act as modifiers of the PC1-dependent cystic phenotype.

When compared to GIIβ, the Sec63 knockout mice have earlier kidney cyst formation and faster progressing cysts [20]. Biochemically, they display more severe defects in the biogenesis of PC1 than PC2 and other transmembrane proteins [20][59]. Genetic changes in PC1 dosage achieved by either reducing or increasing gene copy number further modify the rate of cyst progression in the ADPLD orthologous gene models. In addition, there is a clear temporal component to cyst progression in the ADPLD models. At a common age, Sec63 knockouts are more severe than Prkcsh knockouts and the BAC transgenic rescue kidneys are milder than non-transgenic littermates. Despite being milder at matched time points, the Prkcsh knockouts and the BAC transgenic rescue kidneys continue to progress with slower but nonetheless persistent tubule dilation and cyst growth indicating that these are not on-off phenomena.

These in vivo differences in cyst severity reflect the fact that GIIβ deletion is a ‘milder’ molecular defect, due to existence of alternative N-glycan trimming pathways, whereas Sec63p deletion is more ‘severe’, based on its proximal location in the ER translocation pathway. The critical point in understanding the implications of these models is that the population of kidney tubule cells in which either GIIβ to or Sec63p are inactivated, as well as the timing, are largely the same in all models because the same Cre recombinase transgenic lines were used to knockout the respective genes. Therefore differences in the severity of cyst progression translate to differences in the cell autonomous levels of residual PC1 function, as opposed to differences in the number or types of cells affected. In this formulation, the more severe molecular lesion will have a more significant reduction in PC1 at the individual cell level, thereby giving rise to more severe cystic disease based on differential intrinsic properties of the cyst cells. These differences are determined by the amount of residual PC1 activity.

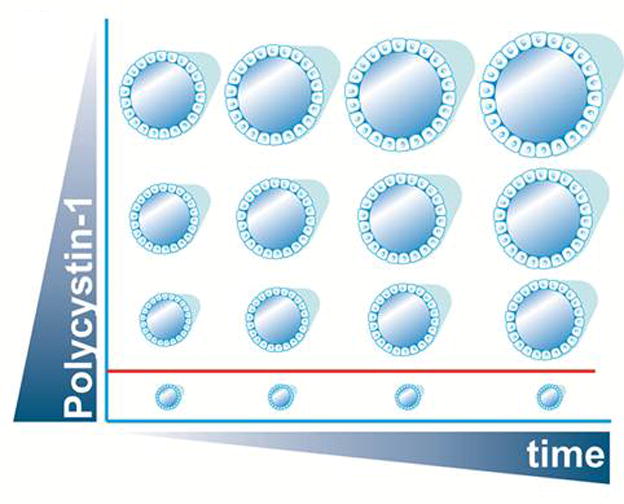

Taken together these data show that kidney tubule diameter is a continuously distributed function of PC1 dosage and time (Figure 3). The greater the reduction in PC1 dosage, the faster the cysts grow; the longer the time in the setting of reduced PC1 dosage, the larger the cysts become. The ‘asymptotic’ extreme is reached in the complete absence of PC1 when kidney tubule luminal diameters expand rapidly in full blown polycystic kidney disease. In defining the ADPLD mouse models as models of hypomorphic PC1 function that give rise to a broad range from tubule dilation to frank cyst formation as a time-dependent function, this study [20] strongly supports the hypothesis that polycystins normally function to regulate tubule lumen diameter under physiological cues that remain to be identified. Coupled with a recent study suggesting that PC1/PC2 tonically inhibits an unknown cilia dependent cyst promoting signaling pathway [37], it can be hypothesized that a regulated signal such as flow or ligands or both, modulate the PC1/PC2 complex to reduce the inhibitory activity. This allows the cilia dependent pathway to alter kidney tubular structure or increase luminal diameter, which can be reversed when the PC1/PC2 is returned to the unstimulated, maximally inhibitory state.

Figure 3.

Schematic view showing that PC1 levels can dictate the timing and severity of the phenotype in a time (x-axis) and dose (y-axis) dependent manner. For a certain PC1 threshold (depicted by the red line) no cyst formation occurs. When the dose of PC1 goes below this threshold, cyst initiation/progression ensues with lower levels leading to faster cyst growth. This is evidenced by the ADPLD mouse models where the lower dosage of PC1 on the Sec63 deficient background leads to an earlier manifestation of the phenotype as compared to the Prkcsh null background.

Organ and tissue specificity in ADPLD

While in mice conditional inactivation of GIIβ or Sec63p in liver and kidney leads to cysts, in humans, ADPLD is restricted to a bile-duct specific phenotype. The increased susceptibility of bile ducts to cyst formation compared to kidney tubules in human ADPLD may reflect that normal PC1 expression in the bile ducts is closer to a critical threshold below which cyst formation ensues. Mutations in PRKCSH or SEC63 in bile duct cells results in reduced functional PC1 which falls below this threshold, whereas in kidney tubules the reduction in PC1 resulting from the same ADPLD gene mutations may not be sufficient to drop below the critical threshold, and hence no cysts occur. Of course, the converse explanation is equally plausible, that bile ducts require higher levels of PC1 to avert cystic dilation than kidney tubules. A corollary to the above hypothesis is that since PC1 levels are reduced but farther above a critical threshold in the kidneys in ADPLD patients, kidney cysts grow more slowly and so do not become clinically apparent in the normal lifespan of the general population. Either way, the kidneys appear to be more “tolerant” of changes in PC1 dosage resulting from ADPLD gene mutations than bile ducts.

In terms of intra-organ sensitivity to reduced PC1 dosage, collecting ducts are more sensitive to cyst formation than the medullary thick ascending loops of Henle (mTAL) following similar levels of inactivation of either Prkcsh or Sec63 (using Ksp-Cre). The exacerbation of the cystic kidney phenotype following reduction of PC1 dosage on the Pkd1+/− background is accounted for almost exclusively by larger (i.e., faster growing) cyst formation in collecting ducts. Applying the same reasoning as above, we postulate that the mTAL is more tolerant of changes in PC1 dosage than the collecting ducts, and thus the effect of decreased PC1 dosage is more easily unmasked in the latter versus the former. This can be clinically significant as evidenced by the recent trial in ADPKD showing reduction of total kidney volume with a vasopressin-2 receptor antagonist [77]. Vasopressin-2 is only expressed in the collecting ducts and therefore this intervention was thought to target primarily collecting ducts cysts.

Modifiers of human ADPKD severity

Recently, genetic modifiers of the severity of polycystic kidney disease in man, beyond differences between PKD1 and PKD2 genotypes, have been identified. Allelic variation in PKD1 has now been shown to affect disease progression [78][79]. The median age to end stage renal disease (ESRD) in PKD1 patients with predicted truncating mutations was 55.6 years, whereas the median age to ESRD for PKD1 patient with non-synonymous potentially pathogenic mutations was 67.9 years. These clinical findings are in keeping with the dosage data from animal studies detailed above. A subset of missense variants likely produce some PC1 protein with residual function resulting in slower growth of cysts and therefore a delay in the median time to ESRD for the group of patients with these mutations. The genotype of the normal PKD1 allele in ADPKD patients can also affect the course of disease, in this instance worsening severity. Two recent studies have reported the existence of partially penetrant PKD1 alleles in APDKD patients that occurred in trans with a fully penetrant truncating mutation or another missense variant [74][80]. In both cases, the individuals carrying two mutations of which at least one was incompletely penetrant showed more severe progression of ADPKD, findings again consistent with the dosage correlated severity model. We are not yet in a position to assess individual mutations for their relative molecular severity, but this should be a goal for the studies in the near future. Such information can inform patients of their family’s prognosis and may also serve as the basis for therapeutic decisions once therapies become available.

Beyond allelic determinants of disease severity, two recent clinical reports have described severe cases in patients with ADPKD who carry, in addition to their expected familial germ-line defect in PKD1, additional mutations in either hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β (HNF-1β) or Sec63 [81][82]. The effects from mutations in genes in trans with PKD1 are similar to previous reports of bilineal inheritance of PKD1 and PKD2 mutations in the same individual, also resulting in more severe ADPKD [13]. These data suggest that patients with ADPKD who present with an early and severe phenotype clinically indistinguishable from autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD) may carry mutations in other genes in trans with PKD1 that affect either the transcriptional control of PKD1 expression such as HNF-1β [83], or the biogenesis of PC1 as is the case with SEC63 and PRKCSH. Clinical testing application of next generation sequencing technologies such as whole-exome sequencing may shed further light on the clinical phenotypic variation noted in ADPKD patients and better define the role of other PKD related genes in the progression of ADPKD in man.

Relationship between PC1 expression and ARPKD

Studies of the role of ADPLD gene mutations and PC1 dosage also revealed an intriguing relationship between PC1 dosage and ARPKD progression. Despite the absence of any polycystic kidney phenotype in mice with loss of Pkhd1, compound Sec63/Pkhd1 mutant mice showed marked exacerbation of cyst formation compared to the Sec63 background alone [20]. There is a precedent for genetic interaction between the Pkhd1 and Pkd1 loci in that loss of one copy of Pkd1 exacerbates cyst progression in Pkhd1 deficient mice [20, 84]. Inactivation of Sec63 results in a more severe reduction in Pkd1 than the heterozygous state [20]. The most compelling evidence of the PC1-dosage dependence of the Pkhd1 kidney phenotype, however, came from the observation that over-expression of PC1 by a three copy BAC transgenic allele rescued the severe cystic disease in the compound Sec63/Pkhd1 double mutant mice [20]. This showed that the worsening of polycystic kidney disease resulting from introduction of the recessive Pkhd1 mutation onto the Sec63 mutant background was largely a function of PC1 dosage. Reduced PC1 dosage sensitizes mice with mutations in Pkhd1 to polycystic kidney phenotypes that are not observed with a wild type complement of Pkd1 expression.

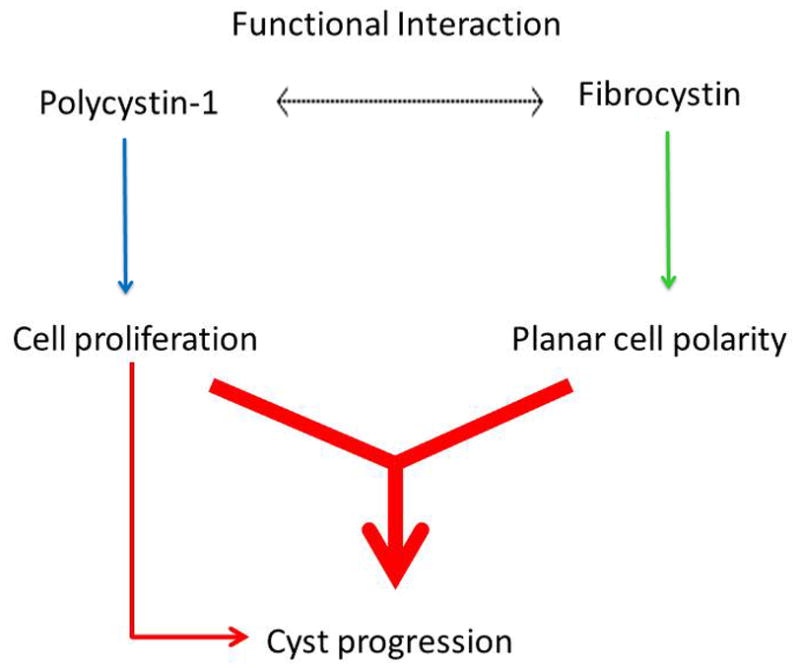

The Pkhd1del4 mutation, while not resulting in cystic dilation, nonetheless causes loss of oriented cell division in elongating nephrons of the postnatal mouse kidney [49]. Oriented cell division is a feature of planar cell polarity [48], [50]. It is possible that coupling loss of planar cell polarity in Pkhd1 mutants with markedly reduced PC1 dosage aggravates cyst growth due to reduced PC1 alone (Figure 4). It is worth noting the rescue by the Pkd1 BAC transgene in the Sec63/Pkhd1 double mutant mice is not as complete as in the Sec63 single mutants. One interpretation of these results may be that in the absence of the Pkhd1 gene product, FPC, the amount of PC1 required to avert cysts is higher than on a wild type Pkhd1 background, supporting the functional interdependence of these two human PKD genes. The most intriguing finding out of these studies is that PC1 dosage can ameliorate the murine ARPKD phenotype in the kidney which begs the question of what the relationship between PC1 and FPC is in human ARPKD. Perhaps there is a dose-dependent relationship where FPC deficiency leads to PKD in man because the relative level of PC1 activity is insufficient to prevent kidney cysts. In this formulation, it is possible that ARPKD may be amenable to therapies that increase the dosage or function of PC1.

Figure 4.

Diagram of the genetic interaction between Pkd1 and the ARPKD locus. Fibrocystin plays a role in cyst progression through its involvement in the planar cell polarity pathway (green arrow). Polycystin-1 (PC1), through its link to cell proliferation (blue arrow), can further contribute to the severity of the phenotype, as seen in the double Pkd1/Pkhd1 mutants. Since defects in planar cell polarity in the absence of Pkhd1 do not lead to polycystic kidney disease, the contribution of planar cell polarity to cyst progression occurs in the context of increased proliferation (red arrow). Is it not clear what the functional interaction between PC1 and Fibrocystin (dotted arrow) is, for example whether there is a direct biochemical connection between the two proteins impacting their respective function/ levels.

Concluding remarks and future perspectives

Based on these insights, modulating levels of PC1 could prove to have therapeutic potential for ADPLD, ARPKD and for ADPKD [74]. There is strong proof of principle supporting this hypothesis whereby proteasome inhibition led to increased levels of PC1 and an amelioration of the cystic phenotype in a model of ADPLD with inactivation of Prkcsh [20]. In that case, proteasome inhibition led to an increase in the levels of PC1, which, coupled with the increase in apoptosis and decrease in proliferation of cyst-lining epithelia, resulted in an amelioration of the cystic phenotype. When compared to wild-type cells, the absence of GIIβ presumably sensitized cells to apoptosis due to the accumulation of unfolded proteins by proteasome inhibition. The reduced proliferation may have resulted from the increased levels of PC1 function. It would be interesting to test whether the beneficial effect of proteasome inhibition is also maintained in the case of Sec63 inactivation (See Box 1).

Box 1. Outstanding questions.

How is PC1 modulating the ARPKD phenotype?

Does overexpression of FPC have a genetic effect on the PC1-dependent phenotype?

Can proteasome inhibition/chemical chaperones improve the biogenesis of PC1 missense mutants?

Is FPC deficiency affecting the biogenesis of PC1?

What are the organ differences between liver and kidney ARPKD that make the former resistant to the beneficial role of PC1?

Is proteasome therapy efficient in slowing cyst formation in the absence of Sec63p?

What is the effect of losing GIIβ/Sec63p on the ER Ca2+ homeostasis?

What is the effect of losing GIIβ/Sec63p on the status of the unfolded protein response?

What is the role of physiological polycystin signaling within cilia?

How can one assess individual missense mutations in PKD1 in terms of their molecular severity?

Based on these studies, PKD1 alleles with incomplete penetrance that produce a full length, albeit mutant PC1 protein, may be amenable to therapies akin to proteasome inhibition that can increase effective functional levels of PC1 and further slow cyst growth. Missense mutant PC1 may maintain functionality but nevertheless get retro-translocated from the ER and targeted for degradation via ER-associate degradation (ERAD)-cytosolic ubiquitin (Ub)–proteasome system [85] or via the recycling endosome/lysosomal pathway in a manner somewhat analogous to the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) ΔF508 mutation [86]. For these scenarios, proteasome and/or lysosome inhibition may increase PC1 dosage by blocking the PC1-dependent degradation pathways. This approach could be coupled with chemical chaperone treatment as has been done for CFTR [87]. This concept suggests that sequencing of PKD1 mutations should be given consideration for implications in personalized medicine.

Highlights.

Polycystin-1 dosage can regulate cyst progression in ADPKD, ADPLD and ARPKD.

The rate for cyst growth can be either sped up or slowed down by alterations in functional PC1.

Impacting PC1 levels via chemical chaperone therapy may slow down cyst progression.

Glossary

- Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD)

the most common monogenic disorder in which kidneys develop fluid-filled cysts derived from the tubule epithelial cells

- Autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease (ADPLD)

a monogenic condition characterized by the growth of bile-duct derived cystic lesions

- Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease (ARPKD)

a rare pediatric disease characterized by fusiform dilation of the collecting ducts in the kidneys, and congenital hepatic fibrosis

- Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC)

a DNA construct used in transgenic mouse technology. BAC transgenics offer the advantages that they are low copy number and can faithfully reproduce the native splicing and expression pattern of genes. BACs can be modified by homologous recombination in E. coli and transgenic lines can be readily generated by pronuclear injection

- Immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein (BiP)

an ER Hsp70-chaperone involved in protein translocation and folding. SEC63 (in addition to ERdj1) recruits BiP to the translocation site via its DnaJ-like domain and provides the necessary ATPase activity to cycle BiP to the ADP-bound high affinity peptide interaction state

- Cystic Fibrosis Transmembrane Conductance Regulator (CFTR)

a transmembrane protein involved in chloride conductance whose deletion results in cystic fibrosis

- Cilia

Apical cellular microtubular projection involved in mechanosensory signaling. In the mammalian kidney, the “primary” cilium (which belongs to the group of immotile ‘9+0’ cilia, i.e. 9 peripheral microtubule doublets and no central pair) is located on the apical surface of epithelial cells and extends into the tubule lumen

- Endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

a cellular organelle that forms a network of membrane sacs called cisternae. It serves many fundamental functions including protein folding, translocation and transport

- ER-associated degradation (ERAD)

a cellular pathway through which misfolded ER proteins are retro-translocated, ubiquitinated and targeted for degradation by the proteasome

- Fibrocystin/polyductin (FPC)

a large integral membrane protein encoded by PKHD1, the gene responsible for the occurrence of ARPKD

- Kidney specific promoter (KSP)

used to specifically inactivate proteins in the thick ascending limb, distal, and collecting duct regions of the nephron

- PRKCSH

the gene that encodes the Protein Kinase C substrate 80K-H (which now is known to function as the β-subunit of glucosidase II). It is involved in the de-glycosylation of N-glycan moieties on nascent polypeptides as part of the calnexin-calreticulin cycle

- Protein biogenesis

the process through which a protein is translated, translocated into the endoplasmic reticulum, folded, and transported to its physiological cellular location

- SEC63

the gene encoding the ER translocon associated protein SEC63, involved in co-translational protein translocation

- Unfolded protein response (UPR)

The unfolded protein response, which involves the coordinate transcriptional activation of a set of genes that encode ER chaperones and certain cell-death signals, occurs as a result of the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER. The UPR is activated by agents that affect ER homeostasis, such as tunicamycin, thapsigargin, Ca2+ ionophores, and reducing agents. In mammalian cells, UPR activation is mediated by three ER transmembrane proteins that function as proximal sensors, designated IRE1, ATF6, and PERK, of which IRE1 is the most conserved from yeast to humans

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Guay-Woodford LM. Renal cystic diseases: diverse phenotypes converge on the cilium/centrosome complex. Pediatr Nephrol. 2006;21:1369–1376. doi: 10.1007/s00467-006-0164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes J, et al. The polycystic kidney disease 1 (PKD1) gene encodes a novel protein with multiple cell recognition domains. Nat Genet. 1995;10:151–160. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mochizuki T, et al. PKD2, a gene for polycystic kidney disease that encodes an integral membrane protein. Science. 1996;272:1339–1342. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5266.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nauli SM, et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet. 2003;33:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qian F, et al. The molecular basis of focal cyst formation in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease type I. Cell. 1996;87:979–987. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81793-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu G, et al. Somatic inactivation of Pkd2 results in polycystic kidney disease. Cell. 1998;93:177–188. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81570-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torra R, et al. A loss-of-function model for cystogenesis in human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease type 2. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;65:345–352. doi: 10.1086/302501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brasier JL, Henske EP. Loss of the polycystic kidney disease (PKD1) region of chromosome 16p13 in renal cyst cells supports a loss-of-function model for cyst pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:194–199. doi: 10.1172/JCI119147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pei Y, et al. Somatic PKD2 mutations in individual kidney and liver cysts support a “two-hit” model of cystogenesis in type 2 autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1524–1529. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1071524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watnick TJ, et al. Somatic mutation in individual liver cysts supports a two-hit model of cystogenesis in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Mol Cell. 1998;2:247–251. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishio S, et al. Pkd1 regulates immortalized proliferation of renal tubular epithelial cells through p53 induction and JNK activation. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:910–918. doi: 10.1172/JCI22850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Piontek K, et al. A critical developmental switch defines the kinetics of kidney cyst formation after loss of Pkd1. Nat Med. 2007;13:1490–1495. doi: 10.1038/nm1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pei Y, et al. Bilineal disease and trans-heterozygotes in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:355–363. doi: 10.1086/318188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu G, et al. Trans-heterozygous Pkd1 and Pkd2 mutations modify expression of polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:1845–1854. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.16.1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lantinga-van LI, et al. Lowering of Pkd1 expression is sufficient to cause polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:3069–3077. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jiang ST, et al. Defining a link with autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease in mice with congenitally low expression of Pkd1. Am J Pathol. 2006;168:205–220. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rossetti S, et al. Incompletely penetrant PKD1 alleles suggest a role for gene dosage in cyst initiation in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2009;75:848–855. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang E, et al. Progressive renal distortion by multiple cysts in transgenic mice expressing artificial microRNAs against Pkd1. J Pathol. 2010;222:238–248. doi: 10.1002/path.2765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hopp K, et al. Functional polycystin-1 dosage governs autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease severity. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2012;122:4257–4273. doi: 10.1172/JCI64313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fedeles SV, et al. A genetic interaction network of five genes for human polycystic kidney and liver diseases defines polycystin-1 as the central determinant of cyst formation. Nat Genet. 2011 doi: 10.1038/ng.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nims N, et al. Transmembrane domain analysis of polycystin-1, the product of the polycystic kidney disease-1 (PKD1) gene: evidence for 11 membrane-spanning domains. Biochemistry. 2003;42:13035–13048. doi: 10.1021/bi035074c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoder BK, et al. The polycystic kidney disease proteins, polycystin-1, polycystin-2, polaris, and cystin, are co-localized in renal cilia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2508–2516. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000029587.47950.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foggensteiner L, et al. Cellular and subcellular distribution of polycystin-2, the protein product of the PKD2 gene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:814–827. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V115814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scheffers MS, et al. Polycystin-1, the product of the polycystic kidney disease 1 gene, co-localizes with desmosomes in MDCK cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2743–2750. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berbari NF, et al. The primary cilium as a complex signaling center. Curr Biol. 2009;19:R526–R535. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2009.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Veland IR, et al. Primary cilia and signaling pathways in mammalian development, health and disease. Nephron Physiol. 2009;111:39–53. doi: 10.1159/000208212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goetz SC, Anderson KV. The primary cilium: a signalling centre during vertebrate development. Nature reviews Genetics. 2010;11:331–344. doi: 10.1038/nrg2774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cai Y, et al. Identification and characterization of polycystin-2, the PKD2 gene product. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:28557–28565. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.40.28557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Celic A, et al. Domain mapping of the polycystin-2 C-terminal tail using de novo molecular modeling and biophysical analysis. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:28305–28312. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802743200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petri ET, et al. Structure of the EF-hand domain of polycystin-2 suggests a mechanism for Ca2+-dependent regulation of polycystin-2 channel activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:9176–9181. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912295107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Geng L, et al. Polycystin-2 traffics to cilia independently of polycystin-1 by using an N-terminal RVxP motif. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1383–1395. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Casuscelli J, et al. Analysis of the cytoplasmic interaction between polycystin-1 and polycystin-2. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2009;297:F1310–1315. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00412.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Celic AS, et al. Calcium-induced conformational changes in C-terminal tail of polycystin-2 are necessary for channel gating. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:17232–17240. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.354613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreira FM, et al. Macromolecular assembly of polycystin-2 intracytosolic C-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:9833–9838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106766108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gallagher AR, et al. Molecular advances in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:118–130. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harris PC, Torres VE. Polycystic kidney disease. Annu Rev Med. 2009;60:321–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.101707.125712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ma M, et al. Loss of cilia suppresses cyst growth in genetic models of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nature genetics. 2013;45:1004–1012. doi: 10.1038/ng.2715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ward CJ, et al. The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nat Genet. 2002;30:259–269. doi: 10.1038/ng833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onuchic LF, et al. PKHD1, the polycystic kidney and hepatic disease 1 gene, encodes a novel large protein containing multiple immunoglobulin-like plexin-transcription-factor domains and parallel beta-helix 1 repeats. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;70:1305–1317. doi: 10.1086/340448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Furu L, et al. Milder presentation of recessive polycystic kidney disease requires presence of amino acid substitution mutations. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:2004–2014. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000078805.87038.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang D, et al. Exome sequencing identifies compound heterozygous PKHD1 mutations as a cause of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Chinese medical journal. 2012;125:2482–2486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nagasawa Y, et al. Identification and characterization of Pkhd1, the mouse orthologue of the human ARPKD gene. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:2246–2258. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000030392.19694.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakeberg JL, et al. Epitope-tagged Pkhd1 tracks the processing, secretion, and localization of fibrocystin. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011;22:2266–2277. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010111173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Menezes LF, et al. Polyductin, the PKHD1 gene product, comprises isoforms expressed in plasma membrane, primary cilium, and cytoplasm. Kidney Int. 2004;66:1345–1355. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang S, et al. The autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease protein is localized to primary cilia, with concentration in the basal body area. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:592–602. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000113793.12558.1d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang MZ, et al. PKHD1 protein encoded by the gene for autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease associates with basal bodies and primary cilia in renal epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2311–2316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400073101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gallagher AR, et al. Biliary and pancreatic dysgenesis in mice harboring a mutation in Pkhd1. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:417–429. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fischer E, et al. Defective planar cell polarity in polycystic kidney disease. Nat Genet. 2006;38:21–23. doi: 10.1038/ng1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nishio S, et al. Loss of oriented cell division does not initiate cyst formation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:295–302. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fedeles S, Gallagher AR. Cell polarity and cystic kidney disease. Pediatric nephrology (Berlin, Germany) 2013;28:1161–1172. doi: 10.1007/s00467-012-2337-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Reynolds DM, et al. Identification of a locus for autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease, on chromosome 19p13.2-13.1. Am J Hum Genet. 2000;67:1598–1604. doi: 10.1086/316904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li A, et al. Mutations in PRKCSH cause isolated autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;72:691–703. doi: 10.1086/368295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Drenth JP, et al. Germline mutations in PRKCSH are associated with autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2003;33:345–347. doi: 10.1038/ng1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Davila S, et al. Mutations in SEC63 cause autosomal dominant polycystic liver disease. Nat Genet. 2004;36:575–577. doi: 10.1038/ng1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Trombetta ES, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum glucosidase II is composed of a catalytic subunit, conserved from yeast to mammals, and a tightly bound noncatalytic HDEL-containing subunit. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27509–27516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stigliano ID, et al. Glucosidase II Beta Subunit Modulates N-Glycan Trimming in Fission Yeasts and Mammals. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;17:3974–84. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-04-0316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Skowronek MH, et al. Molecular characterization of a novel mammalian DnaJ-like Sec63p homolog. Biol Chem. 1999;380:1133–1138. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hanein D, et al. Oligomeric rings of the Sec61p complex induced by ligands required for protein translocation. Cell. 1996;87:721–732. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81391-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lang S, et al. Differential effects of Sec61alpha-, Sec62- and Sec63-depletion on transport of polypeptides into the endoplasmic reticulum of mammalian cells. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1958–1969. doi: 10.1242/jcs.096727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mades A, et al. Role of human sec63 in modulating the steady-state levels of multi-spanning membrane proteins. PloS one. 2012;7:e49243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alder NN, et al. The molecular mechanisms underlying BiP-mediated gating of the Sec61 translocon of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:389–399. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Blau M, et al. ERj1p uses a universal ribosomal adaptor site to coordinate the 80S ribosome at the membrane. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:1015–1016. doi: 10.1038/nsmb998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Waanders E, et al. Secondary and tertiary structure modeling reveals effects of novel mutations in polycystic liver disease genes PRKCSH and SEC63. Clin Genet. 2010;78:47–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zimmermann R, et al. Protein transport into the endoplasmic reticulum: mechanisms and pathologies. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Janssen MJ, et al. Secondary, Somatic Mutations Might Promote Cyst Formation in Patients With Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:2056–2063. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Janssen MJ, et al. Loss of Heterozygosity Is Present in SEC63 Germline Carriers with Polycystic Liver Disease. PloS one. 2012;7:e50324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Watnick T, et al. Mutations of PKD1 in ADPKD2 cysts suggest a pathogenic effect of trans-heterozygous mutations. Nat Genet. 2000;25:143–144. doi: 10.1038/75981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davenport JR, et al. Disruption of intraflagellar transport in adult mice leads to obesity and slow-onset cystic kidney disease. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1586–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takakura A, et al. Pkd1 inactivation induced in adulthood produces focal cystic disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:2351–2363. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007101139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Takakura A, et al. Renal injury is a third hit promoting rapid development of adult polycystic kidney disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2523–2531. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patel V, et al. Acute kidney injury and aberrant planar cell polarity induce cyst formation in mice lacking renal cilia. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1578–1590. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bastos AP, et al. Pkd1 haploinsufficiency increases renal damage and induces microcyst formation following ischemia/reperfusion. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:2389–2402. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008040435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharma N, et al. Proximal tubule proliferation is insufficient to induce rapid cyst formation after cilia disruption. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2013;24:456–464. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012020154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rossetti S, et al. Incompletely penetrant PKD1 alleles suggest a role for gene dosage in cyst initiation in polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2009;75:848–855. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pritchard L, et al. A human PKD1 transgene generates functional polycystin-1 in mice and is associated with a cystic phenotype. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:2617–2627. doi: 10.1093/hmg/9.18.2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bergmann C, Weiskirchen R. It’s not all in the cilium, but on the road to it: Genetic interaction network in polycystic kidney and liver diseases and how trafficking and quality control matter. J Hepatol. 2011;56:1201–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Torres VE, et al. Tolvaptan in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:2407–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Audrezet MP, et al. Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: comprehensive mutation analysis of PKD1 and PKD2 in 700 unrelated patients. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1239–1250. doi: 10.1002/humu.22103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cornec-Le Gall E, et al. Type of PKD1 mutation influences renal outcome in ADPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1006–1013. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vujic M, et al. Incompletely penetrant PKD1 alleles mimic the renal manifestations of ARPKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:1097–1102. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009101070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bergmann C, et al. Mutations in multiple PKD genes may explain early and severe polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22:2047–2056. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010101080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kleffmann J, et al. Dosage-sensitive network in polycystic kidney and liver disease: Multiple mutations cause severe hepatic and neurological complications. J Hepatol. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gresh L, et al. A transcriptional network in polycystic kidney disease. EMBO J. 2004;23:1657–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Garcia-Gonzalez MA, et al. Genetic interaction studies link autosomal dominant and recessive polycystic kidney disease in a common pathway. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:1940–1950. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hampton RY, Sommer T. Finding the will and the way of ERAD substrate retrotranslocation. Current opinion in cell biology. 2012;24:460–466. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Belcher CN, Vij N. Protein processing and inflammatory signaling in Cystic Fibrosis: challenges and therapeutic strategies. Current molecular medicine. 2010;10:82–94. doi: 10.2174/156652410791065408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Valle CW, Vij N. Can correcting the DeltaF508-CFTR proteostasis-defect rescue CF lung disease? Current molecular medicine. 2012;12:860–871. doi: 10.2174/156652412801318773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]