Summary

MultiTEP platform-based AD epitope vaccine provides broad coverage of MHC polymorphism in non-human primates.

Background

As a prelude to clinical trials we have characterized B and T cell immune responses in macaques to AD vaccine candidates: AV-1955 and its slightly modified version, AV-1959 (with three additional promiscuous Th epitopes).

Methods

T and B cell epitope mapping was performed using ELISPOT assay and competition ELISA, respectively.

Results

AV-1955 and AV-1959 did not stimulate potentially harmful autoreactive T cells, activating a broad but individualized repertoire of Th cells specific to MultiTEP platform in macaques. Although, both vaccines induced robust anti-Aβ antibody responses without producing antibodies specific to Th epitopes of MultiTEP platforms, analyses of cellular immune responses in macaques demonstrated that the addition of Th epitopes in the case of AV-1959 created a more potent, superior vaccine.

Conclusion

AV-1959 is a promising vaccine candidate capable of producing therapeutically potent anti-amyloid antibody in a broader population of vaccinated subjects with high MHC class II genes polymorphisms.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease (AD), AD epitope vaccine, Electroporation, Rhesus macaques, Mapping of B and T cell immune responses

1. Introduction

Aβ peptides have been thought to play a central role in the onset and progression of Alzheimer's disease (AD), and it was this proposal from which the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’ emerged [1]. According to this hypothesis, the primary pathological event is the accumulation of Aβ in the brain because of either overproduction or aberrant clearance, resulting in the deposition of aggregated forms of this peptide as insoluble fibrils, soluble oligomers/protofibrils, and plaques [1, 2]. The amyloid cascade hypothesis has evolved to focus mainly on soluble oligomers and protofibrils of Aβ, which are now considered to be the most toxic forms of this protein, responsible for causing synaptic destruction [3]. Accordingly, many strategies for the development of therapies for AD are aimed at reducing the level of these Aβ peptides in the brain, and/or blocking the assembly of this peptide into pathological forms that disrupt cognitive function [4, 5].

One potentially powerful strategy for reducing the level of toxic forms of Aβ in the brain is immunotherapy, which via anti-Aβ antibodies could facilitate the clearance and/or accumulation of amyloid deposits from the brain of APP transgenic (APP/Tg) mice [6]. Based on data generated in different AD mouse models, the first AN-1792 vaccine trial was initiated and terminated early because 18 of 298 patients treated with fibrillar Aβ42 (fAβ42) formulated in adjuvant developed meningoencephalitis [7]. While the exact cause of the adverse events is still unknown, speculations were centered on autoreactive T-cell responses to self-epitopes within the Aβ42, the QS-21 adjuvant, and/or reformulation of the vaccine in polysorbate 80 prior during the phase IIa trial[8, 9]. Importantly, case reports suggested that anti-Aβ42 antibodies were not responsible for the CNS inflammation[10], while significantly reducing the amyloid-plaque load[11, 12]. Unfortunately, follow-up studies of the participants revealed that although vaccinations resulted in clearance of amyloid plaques from the brain, soluble oligomeric forms of Aβ were not reduced and progressive neurodegeneration was not prevented [12, 13]. In addition, considering that AN-1792 was administered in the presence of a strong adjuvant, the low percentage of antibody responders (∼20%) and the generally low antibody titers (≥1:2200) observed in both trials [10] indicate that this self-fAβ42 antigen as not a strong immunogen and emphasize the difficulties associated with active immunization in elderly patients with immunosenescence [14].

One strategy to avoid adverse autoreactive cellular immune responses, and to overcome hyporesponsiveness to self-Aβ antigen, is to use passive vaccination strategy that have been tested in animal models [15], as well as in patients with mild-to-moderate AD [16, 17]. Earlier we proposed an alternative strategy based on active immunotherapeutic agents composed of small N-terminal fragments of the Aβ peptide conjugated to foreign CD4+ T-cell epitopes [18, 19] or carriers possessing CD4+ T helper (Th) cell epitopes [18, 19]. Several such peptide/protein-based epitope vaccines including ours have been tested in preclinical animal models [18, 20-24], and some of them are currently being tested in clinical trials [9, 25-28].

Our group first reported also on the DNA vaccination targeting amyloid (Aβ42) [29], and we subsequently engineered a construct encoding molecular adjuvant (macrophage derived chemokine, CCL22) fused in frame with three copies of the immunodominant self-B cell epitope of Aβ42, Aβ1-11, and synthetic promiscuous foreign T helper (Th) cell epitope, PADRE. Immunizations of the 3×Tg AD mouse model with this second generation DNA epitope vaccine induced anti-Aβ1-11 antibodies, which in turn inhibited accumulation of Aβ42 pathology in the brains of older mice, reduced glial activation and prevented the development of behavioral deficits in aged animals without increasing the incidence of microhemorrhages [24]. Normally CD4+ Th cell receptor (TCR) is able to discriminate foreign from self-peptides presented by self MHC class II molecules. However, due to the extremely polymorphic nature of MHC genes in humans, different epitope(s) from the same foreign antigen incorporated in vaccine design can be presented by MHC class II and activate different Th cells repertoire in different people. On the other hand, the B cell receptor (BCR) can recognize foreign and self-molecules equally well. Thus, to increase the immunogenicity of our prototype AD vaccine in humans, we added to PADRE eight or eleven promiscuous Th epitopes from various pathogens (collectively designated as MultiTEP platform) and generated AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines, respectively. In these pre-clinical studies we report for the first time on the mapping of B and T cell immune responses in inbred mice and non-inbred rhesus macaques immunized with AV-1955 or AV-1959 vaccines.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

Female, 6-8 weeks old C57BL/6 mice (H-2b haplotype) were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Sacramento, CA). All mice were housed in a temperature and light-cycle controlled facility, and their care was under the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health and an approved IACUC protocol at University of California, Irvine. Adult, male, genetically unselected rhesus macaques ranging in age from 2 years 8 months to 3 years 9 months from the primate colony at the New Iberia Research Center (New Iberia, LA) were utilized for this study. The macaques were housed in accordance with accepted standards and monitored daily for signs of illness or distress as we described earlier in [30].

2.2. DNA constructs

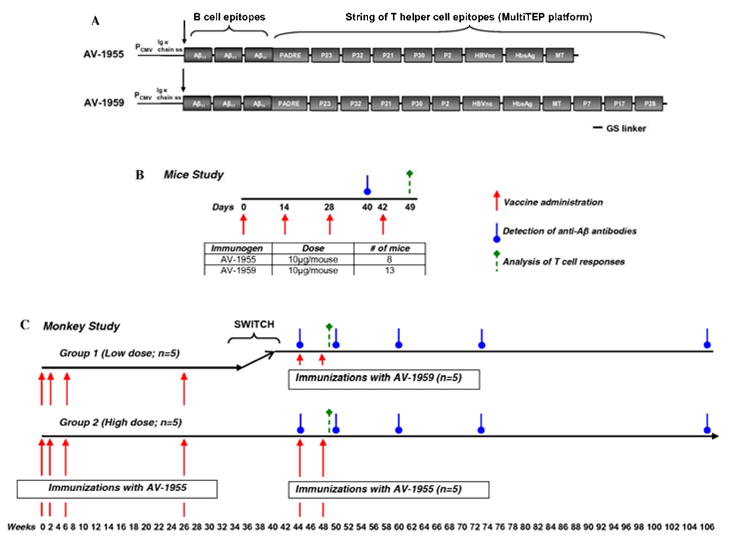

AV-1959 was generated by modification of the construct AV-1955 previously described in [30, 31] (Fig. 1A). Briefly, the AV-1955 codes for a protein consisting of the Ig κ- chain signal sequence, three copies of the A1-11 B cell epitope, one synthetic peptide (PADRE), and a string of eight non-self promiscuous Th epitopes (Thep) from Tetanus Toxin (TT) (= P2, P21, P23, P30 and P32), hepatitis B virus (HBsAg, HBVnc) and influenza (MT). For generation of AV-1959, three new Th epitopes from TT were added to AV-1955 construct: P7 (NYSLDKIIVDYNLQSKITLP), P17 (LINSTKIYSYFPSVISKVNQ) and P28 (LEYIPEITLPVIAALSIAES) by overlapping PCR (Fig. 1A). The pVAX1 vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), which was designed to be coherent with current Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidelines, was used as the plasmid backbone. DNA sequencing was performed to confirm that the generated plasmids contained the correct sequences.

Fig. 1.

Schematic representation of constructs encoding epitope vaccines and experimental design in mice and macaques. (A) Schematic representation of AV-1955 and AV-1959 constructs encoding 3 copies of Aβ1-11 fused to eight or eleven foreign promiscuous Th epitopes from infectious agents and one universal synthetic Th epitope, PADRE, respectively. A signal sequence from the mouse Ig κ-chain is located adjacent to the N-terminus of the first Aβ1-11. (B) Design of experimental protocol in mice vaccinated with AV-1955 and AV-1959. (C) The schematic representation of the experimental protocol in macaques shows the weeks at which vaccines were administered and blood was drawn for detection of Aβ-specific antibodies in sera or for analysis of T cell responses in PBMCs. Of note, after 18 wks of resting period NHP in Group 1 previously immunized with low dose of AV-1955 were switched to vaccinations with high dose of AV-1959 (wks 44 and 48), while macaques in Group 2 were continued to receive immunizations with high dose of AV-1955 (wks 44 and 48).

2.3. Immunization of mice

Two groups of mice were immunized with 10μg/mouse AV-1955 or AV-1959 on days 0, 14, 28 and 42 in a single anterior tibialis muscle using the electroporation system (Ichor Medical Systems, San Diego, CA) as described in [32] (Fig. 1B). Sera were collected on day 12 after third immunization and were used for analyzing of humoral immune responses. On day 7 after the forth immunization mice were terminated, spleens were isolated, and splenocytes were used for detection of cellular immune responses. Experiment was repeated twice.

2.4. Vaccine administration to non-human primates

Two groups of rhesus macaques (n=5/group) received two bilateral administrations of either 0.4 mg total (Group 1; low dose group) or 4 mg total (Group 2; high dose group) of AV-1955 [30]. One group of three macaques (Group 3) served as a negative control and received two bilateral administrations of 4 mg of a noncoding control vector, pVAX1. Electroporation was applied to all experimental and control animals as described in [30]. After 18 weeks of resting period, macaques in Group 1 previously immunized with low dose of AV-1955 were switched to vaccinations with high dose of AV-1959 (at weeks 44 and 48), while macaques in Group 2 were continued to receive immunizations (at weeks 44 and 88) with high dose of AV-1955 (Fig. 1C). Blood was collected and serum isolated for analysis of Aβ-specific antibody responses at weeks 44, 50, 60, 73 and 106. PBMC were isolated from whole blood collected at week 49 and stored at -70°C until cellular immune responses were analyzed.

2.5. Detection of Aβ-specific antibodies and fine mapping of B cell responses

The concentrations of anti-Aβ antibodies in mouse [21, 24] and NHP [30] sera were determined by ELISA as we described previously. The isotypes of monkey anti-Aβ antibodies were evaluated in pre-bleed and immune (collected at week 50) serum samples diluted 1:200, using HRP-conjugated anti-monkey IgG (Fitzgerald Industries Intl. Inc., Acton, MA) and IgM (Alpha Diagnostic Intel, Inc., San Antonio, TX) as secondary antibodies at dilutions of 1:50,000 and 1:2,000, respectively. The OD450 values for pre-bleed (week 0) samples were subtracted from the week 50 samples.

To map B cell responses we used competition ELISA previously described in [33]. Briefly, immune sera from immunized mice and NHP were diluted 1:500 and 1:250, respectively, in TTBS buffer with 0.3% non-fat milk and mixed with equal volumes of small overlapping peptides (A-2-10, A-1-11, A1-12, A2-13, A3-14, A5-16, A7-18; GenScript, Piscataway, NJ), or A42 (American Peptide Company, Sunnyvale, CA) peptide at different concentrations: 0.078 μM, 0.312 μM, 1.25 μM, and 5 μM. After pre-incubation with peptides, binding of immune sera to Aβ42 was detected with standard ELISA. The percent of binding of sera blocked with small peptides to Aβ42 was calculated considering the binding of sera without competing peptides to Aβ42 as 100%. These experiments were repeated twice with similar results.

2.6. Dot blot

To test binding of immune sera to peptides from MultiTEP platform, one microliter (1μg each) of P2, P21, P23, P30, P32, HBsAg, HBVnc, MT, P7, P17, P28 peptides (GenScript, Piscataway, NJ) as well as control Aβ42 peptide were applied to nitrocellulose membrane (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ). After blocking with 5% fat-free dry milk in TTBS and washing, the membranes were probed with sera from NHP immunized with AV-1955 and AV-1959 (1:200). The membranes were incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-monkey antibody (1:2000) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA). Blots were developed using Luminol reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, CA) and exposed to Kodak X-Omat AR film (Kodak, Rochester, NY).

2.7. IFN-γ ELISPOT assay

Analysis of T cells producing IFN-γ cytokines was performed in splenocyte cultures from immunized mice by ELISPOT assay (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), as previously described [20, 21]. The cultures of splenocytes were re-stimulated in vitro with individual peptides, P2, P21, P23, P30, P32, HBsAg, HBVnc, MT, P7, P17, P28, cocktail of these peptides, soluble Aβ40, or irrelevant peptide (16-mer from human tau protein). Individual peptides and proteins were used at concentration of 10μg/ml, while mixture of peptides had 2μg/ml of each peptide. Detection of IFN-γ cytokine production in PBMC of rhesus macaques was measured by ELISPOT assay (Mabtech Inc, Cincinnati, OH) as described in [30]. Cell cultures were re-stimulated with individual peptides, P2, P21, P23, P30, P32, HBsAg, HBVnc, MT, P7, P17, P28 or with a cocktail of these peptides, as well as with recombinant proteins, AV-1959, MultiTEP (i.e. AV-1959 lacking 3Aβ) or an irrelevant protein (BORIS). To test autoreactive Th cell responses we used soluble Aβ40 peptide, while for testing of a background level of Th cell activation we used an irrelevant 16-mer peptide from human tau peptide. Proteins and individual peptides were used at concentration of 20μg/ml, while mixture of peptides has 2μg/ml of each peptide. Spots were counted using a CTL-ImmunoSpot S5 Macro Analyzer (Cellular Technology Ltd., Shaker Heights, OH). The differences in numbers of SFC (spot-forming colonies) per 106 splenocytes or PBMC re-stimulated with Th peptides or Aβ40, and the SFC with 106 splenocytes or PBMC re-stimulated with irrelevant peptide were calculated. In case of re-stimulation with proteins SFC was calculated as numbers of SFC per 106 PBMC re-stimulated with AV-1959 or MultiTEP recombinant proteins minus numbers of SFC with 106 PBMC re-stimulated with irrelevant protein.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Statistical parameters (mean, standard deviation (SD), significant difference, etc.) were calculated using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). Statistically significant differences were examined using a two-tailed t-test (a P value of less than 0.05 was considered significant).

3. Results

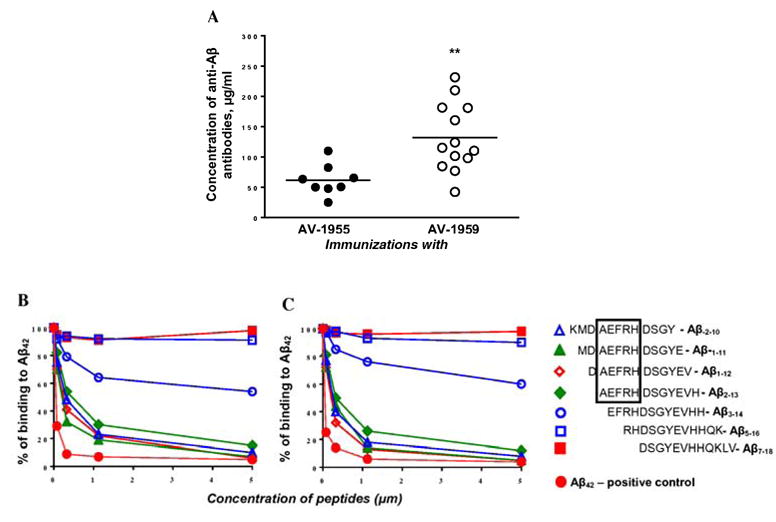

First, to further increase the immunogenic potential of our AV-1955 vaccine [24] in human population, we have added to the MultiTEP platform three new peptides from tetanus toxin (TT: P7, P17 and P28) that are capable of binding to other human MHC class II molecules (Fig. 1A), creating the AV-1959 vaccine. We compared the immunogenicity of these vaccines in inbred mice of H-2b immune haplotype and non-inbred rhesus macaques with highly polymorphic MHC class II genes. Analysis of humoral immune responses in individual C57BL/6 mice vaccinated either with AV-1955 (n=8) or AV-1959 (n=13) showed that the latter immunogen induced significantly stronger production of anti-Aβ antibodies (P<0.01, Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of humoral immune responses in mice of H2b haplotype immunized with AV-1955 and AV-1959 DNA epitope vaccines. (A) AV-1959 (n=13) induces significantly stronger anti-Aβ antibody responses than AV-1955 epitope vaccine (n=8). Data represent two separate experiments. Lines indicate average (**P≤0.01). (B, C) Inhibition studies with indicated concentrations of Aβ-2-10, Aβ-1-11, Aβ1-12, Aβ2-13, Aβ3-14, Aβ5-16, Aβ7-18 and Aβ42 peptides using competition assay. The sera from mice immunized with AV-1955 (B) and AV-1959 (C) were diluted (final dilution 1:1000) and pre- incubated for 1hour at 37°C with peptides mentioned above, before binding to Aβ42-coated wells. The percent of inhibition by small peptides, as well as by control full-length peptide, was calculated considering the binding of sera without competing peptides to Aβ42 as a 100%.

Previously, various groups [33-36] have mapped the immunodominant B cell epitope of Aβ42 within first 15 aa of the N-terminus of this peptide. In addition, there are data suggesting that the free N-terminal aspartic acid of Aβ42 may be essential for induction of antibodies at least in humans [37]. Because AV-1955 and AV-1959 each possess one immunodominant B cell epitope of Aβ42 with free aspartic acid, we tested the specificity of antibodies using sera from mice immunized with AV-1955 or AV-1959, and seven overlapping 12-mer peptides (Fig. 2B, C). Our data showed that immune sera from mice immunized with both vaccines recognized four peptides spanning KMDAEFRHDSGY, MDAEFRHDSGYE, DAEFRHDSGYEV, and AEFRHDSGYEVH amino acids very well. However, removal of one amino acid, alanine, significantly inhibited binding of immune sera from mice vaccinated with either AV-1955 or AV-1959 to EFRHDSGYEVHH peptide. Both immune sera did not recognize RHDSGYEVHHQK and DSGYEVHHQKLV peptides. These results indicate that AEFRH is the smallest sequence that is recognized by anti-Aβ antibodies generated in mice by AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines, and free aspartic acid is not important for immunogenicity of our DNA epitope vaccines in mice.

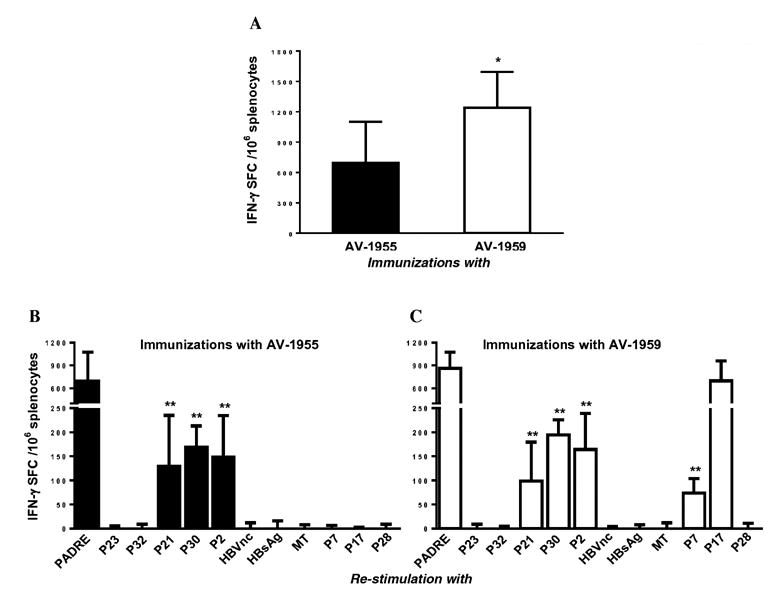

Next, we analyzed cellular immune responses in immune splenocytes isolated from mice vaccinated with AV-1955 and AV-1959 that were re-stimulated in vitro with Aβ40 or with a cocktail of peptides incorporated in MultiTEP platform of AV-1959. Both AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines did not induce potentially harmful autoreactive immune responses, showing baseline level of IFN-γ producing cells after re-stimulation of immune splenocytes with Aβ40 peptide in ELISPOT assay (data not shown). In contrast, splenocytes from mice vaccinated with both epitope vaccines responded very well to re-stimulation with a cocktail of twelve peptides representing promiscuous Th epitopes (Fig. 3A). Vaccination with AV-1959 induced significantly stronger cellular immune responses than vaccination with AV-1955 (P<0.05, Fig. 3A). We suggest that the addition of three new epitopes from TT (P7, P17 and P28) to the MultiTEP platform is responsible for the stronger immunogenicity of the AV-1959 vaccine. To examine this hypothesis, we analyzed Th cell immune responses after re-stimulation of immune splenocytes by individual peptides from MultiTEP platform of AV-1959 vaccine. Mapping of Th cell responses revealed that both the AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines activated Th cells specific to PADRE, P21, P30, and P2 (Fig. 3B, C). Notably, we detected significantly higher numbers of Th cells specific to PADRE compared to P21, P30, and P2 peptides in immune splenocytes isolated from both AV-1959 and AV-1955 vaccinated mice. Importantly, as we hypothesized, in mice immunized with AV-1959 (Fig. 3C), but not AV-1955 (Fig. 3B) we detected Th cells specific to two of the new peptides, P7 and P17, incorporated into the MutiTEP platform. Actually, Th epitope P17 was almost as immunogenic as synthetic Th epitope, PADRE, while the immunogenicity of P7 epitope was comparable to P21, P30, and P2 epitopes. Although, some Th epitopes incorporated in MultiTEP platform are not immunogenic in some mice, we should mention that they are known to be immunogenic in humans [38]. In summary, comparison of the immunogenicity of AV-1955 versus AV-1959 vaccine in inbred mice of H-2b immune haplotype demonstrated that inclusion of additional Th epitopes in MultiTEP platform further enhances its immunogenicity.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of cellular immune responses in mice of H2b haplotype immunized with AV-1955 or AV-1959 DNA epitope vaccines. (A) The AV-1959 induced significantly stronger Th cell responses than AV-1955 epitope vaccine. Splenocytes were re-stimulated with a cocktail of 12 Th epitope peptides (2μg/ml each) incorporated in the AV-1959 construct. Data represent average results obtained in 2 separate experiments. Error bars indicate mean ± SD (*P≤0.05, n=6/per group). (B, C) Mapping of Th epitopes recognized by antigen-specific T helper cells generated in AV-1955 (B) and AV-1959 (C) vaccinated mice. Splenocytes were re-stimulated with 10μg/ml of each peptide. Bars represent mean ± SD (n=6/per group). Statistical significance was calculated against PADRE-specific spot-forming cells (SFC) using two-tailed t-test (**P≤0.01).

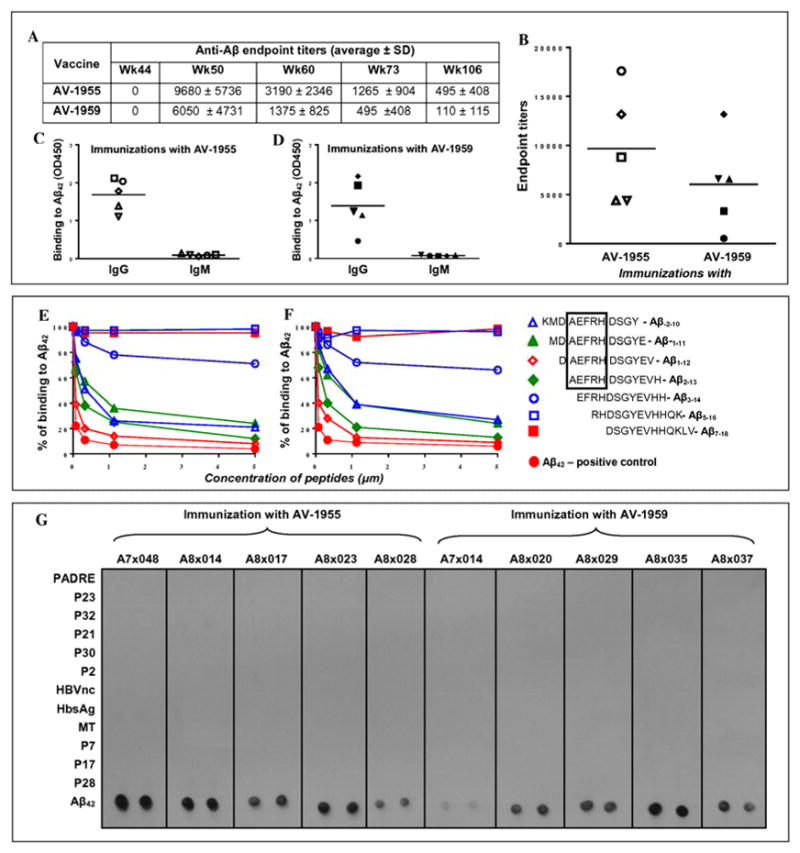

Further studies of the immunogenicity of AV-1959 were carried out in non-human primates (NHP) that possess highly polymorphic MHC class II molecules similar to humans [39]. In this pre-clinical study, macaques after 18-week resting period from prior immunization with a low dose of AV-1955 (0.4 mg/animal) [30] were then immunized with a high dose of AV-1959 (4 mg/animal). Macaques that received high dose of AV-1955 continued to receive immunizations with high dose of AV-1955 (Fig. 1C). Anti-Aβ antibody responses were measured at different time points post-immunization and the data suggested that (i) both AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines were equally effective in stimulation of anti-Aβ antibody production, and (ii) these humoral immune responses were long-lasting: antibodies were detected in 7 out of 10 macaques even after almost 1.2 years of the last immunization (week 106) (Fig. 4A, B). As we expected from the previous study [30] both AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines induce only Aβ-antibodies of IgG subtype (Fig. 4C, D), indicating that the humoral immune responses were T cell dependent. To define the specificity of antibodies induced in non-human primates, we performed fine mapping of the B cell epitopes in immune sera isolated from AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccinated macaques. The data demonstrated that both vaccines induced anti-Aβ antibodies that recognize strongly DAEFRHDSGYEV and AEFRHDSGYEVH peptides, although they bind to the latter with slightly lower affinity (Fig. 4E, F). Immune sera from NHP bound with slightly lower affinity to other two peptides (KMDAEFRHDSGY and MDAEFRHDSGYE) containing the AEFRH sequence, while removal of alanine from AEFRHDSGYEVH significantly inhibited binding of anti-Aβ antibodies (Fig. 4E, F). As in mice, mapping data with immune sera collected form NHP vaccinated with AV-1955 and AV-1959 showed that anti-Aβ antibodies do not recognize the RHDSGYEVHHQK and DSGYEVHHQKLV peptides. These results indicate that the AEFRH sequence is the minimum B cell epitope capable of inducing strong anti-Aβ antibody responses in NHP in response to the AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines. As for the free aspartic acid residue that may be important for activation of B cells in humans [37], our mapping data suggest that it is not absolutely necessary for strong binding of NHP antibodies to Aβ42, although it may improve binding. Next, we analyzed for the first time the antibody responses specific to foreign peptides incorporated in MultiTEP platform in macaques vaccinated with AV-1955 and AV-1959. We assessed the binding of immune sera from vaccinated macaques to twelve peptides from MultiTEP platform of AV-1959 and Aβ42 peptide adsorbed onto nitrocellulose paper. Data from dot blot assays demonstrated that immunizations with both AV-1955 and AV-1959 induce antibodies specific to Aβ, but not to any other peptide sequence incorporated into both vaccines (Fig. 4G). In other words, both AD vaccines do not stimulate in macaques B cells producing antibodies specific to promiscuous Th epitopes used for the design of our MultiTEP platform (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of humoral immune responses in NHP immunized with AV-1955 or AV-1959 DNA epitope vaccines. (A) Average value of endpoint titers of anti-Aβ antibodies in NHP at different time points. (B) Endpoint titers of anti-Aβ antibodies in NHP at week 50. Lines indicate mean value. (C, D) IgG and IgM isotypes of antibodies were analyzed in sera (from week 50) of individual animals vaccinated with AV-1955 (C) and AV-1959 (D). Horizontal lines indicate mean OD450. (E, F) Inhibition studies with indicated concentrations of Aβ-2-10, Aβ-1-11, Aβ1-12, Aβ2-13, Aβ3-14, Aβ5-16, Aβ7-18, Aβ42 peptides using competition assay. The sera from monkeys immunized with AV-1955 (E) and AV-1959 (F) were diluted (final dilution 1:500) and pre-incubated 1hour at 37°C with above mentioned peptides before binding to Aβ42 coated wells. The percent of binding of sera blocked with small peptides to Aβ42 was calculated considering the binding of sera without competing peptides to Aβ42 as 100%. (G) No antibody response specific to peptides incorporated in MultiTEP platform was detected in macaques immunized with AV-1955 and AV-1959. Binding of NHP sera (at week 50, dilution 1:200) to MultiTEP peptides and to Aβ42 was analyzed by Dot blot assay.

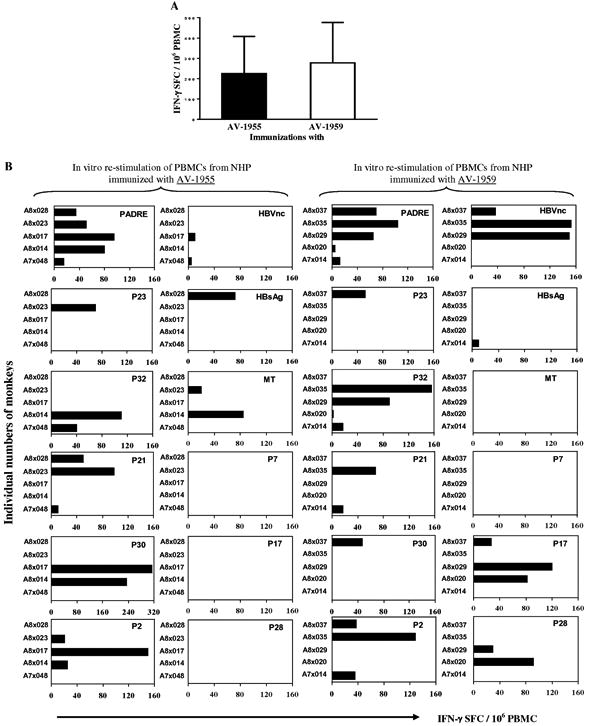

To confirm that the same peptides that do not activate B cells, can stimulate Th cells, we analyzed cellular immune responses after re-stimulation of PBMCs isolated from vaccinated macaques by a cocktail of 12 peptides from MultiTEP platform of AV-1959 vaccine. The data from these experiments suggest that both vaccines activated cellular immune responses equally well (Fig. 5A). Of note, we did not detect activation of Th cells after re-stimulation of PBMC from individual macaques by Aβ40 peptide (data not shown), indicating that our vaccines are safe because they did not activate potentially dangerous autoreactive cellular immune responses. Antigen-specific immune responses were detected also after re-stimulation of immune PBMC with both recombinant vaccines and appropriate MultiTEP recombinant proteins. Both AV-1959 and its MulitTEP proteins activated similar numbers of cells producing IFN-γ in vitro (SFC = 368 ± 161 and SFC = 372 ± 182 per 106 PBMC respectively) and these numbers were comparable to that detected in case of AV-1955 [30]. Collectively, data in Fig. 5 and these results argued that both DNA epitope vaccines activating T cells specific to foreign Th epitopes incorporated in MultiTEP, but not to self-Aβ1-11 peptide.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of cellular immune responses in NHP immunized with AV-1955 and AV-1959 DNA epitope vaccines. (A) PBMCs were re-stimulated with a cocktail of 12 Th epitope peptides (2μg/ml each) incorporated in the AV-1959 construct. Error bars indicate mean ± SD (n=5/per group). (B) T cell responses specific to individual T helper epitopes in NHP immunized with AV-1955 or AV-1959 vaccines. Data was presented as a number of IFN-γ cytokine producing cells (SFC – spot-forming cells) specific to individual peptides minus the background level. All peptides were used at 20μg/ml. No response was detected specific to Aβ40 peptide (20μg/ml). Re-stimulation of PBMCs isolated from DNA vector immunized animals (n=3) did not activate cellular immune responses to any of the peptides.

To further analyze these antigen-specific celluar responses we mapped Th cell responses after re-stimulation of immune PBMC with each Th epitope incorporated in our MultiTEP platform. Our data demonstrated that AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines induced Th cell responses in all 10 macaques, although, as expected, the immunogenicity of Th epitopes within the MultiTEP platform was different between individual animals. Quantitative analyses demonstrated that epitopes that are strong in one monkey, can have mediocre or week immunogenicity in other animals (Fig. 5B). For example, strong Th cell immune responses (over 100 IFN-γ positive SFC per 106 PBMC) were detected in two animals after re-stimulation of immune PBMC cultures with P32, while this response was mediocre (50-100 IFN-γ positive SFC per 106 PBMC) in 1 macaque, weak (less than 50 IFN-γ positive SFC per 106 PBMC) in 3 macaques, and no response was detected in 4 animals (Fig. 5B).

Table 1 presents the analysis of prevalence of Th epitopes within the NHP population used in our vaccination study. The data demonstrate that each macaque with diverse MHC class II molecules responded to different set of Th epitopes. Interestingly, PADRE was immunogenic in 100% of macaques: PBMCs from all animals responded to the re-stimulation with the synthetic promiscuous Th epitope, PADRE, which is known to be recognized by 14 of 15 human DR molecules [40]. The next most prevalent Th epitopes were P2, P32, P17, P21 from TT, and HBVnc from HBV, that were immunogenic in 50-60% of vaccinated animals. The remaining Th epitopes were capable of activating Th cells in 20-30% of animals, while one Th epitope, P7, was not recognized by any of the 5 macaques immunized with AV-1959 vaccine.

Table 1.

Mapping of T helper epitopes in NHP immunized with AV-1955 or AV-1959 vaccines.

| Vaccine | Monkey # |

Th epitopes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PADRE | P23 | P32 | P21 | P30 | P2 | HBVnc | HBsAg | MT | P7 | P17 | P28 | ||

| AV-1955 | A7×048 | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | - | - | NA | NA | NA |

| A8×014 | + | - | + | - | + | + | - | - | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| A8×017 | + | - | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | NA | NA | NA | |

| A8×023 | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | + | NA | NA | NA | |

| A8×028 | + | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | NA | NA | NA | |

| AV-1959D | A7×014 | + | - | + | + | - | + | - | + | - | - | - | - |

| A8×020 | + | - | + | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | + | + | |

| A8×029 | + | - | + | - | - | - | + | - | - | - | + | + | |

| A8×035 | + | - | + | + | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | - | |

| A8×037 | + | + | - | - | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | - | |

| % of responder | 100 | 20 | 60 | 50 | 30 | 60 | 50 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 60 | 40 | |

4. Discussion

Numerous studies from various groups including ours have reported on various types of recombinant protein/peptide-based epitope vaccines composed of different N-terminal regions of Aβ42 (from Aβ1-6 to Aβ1-15) and carrier proteins or foreign Th cell epitopes [9, 20, 22, 27, 28]. Collectively, data showed that these vaccines inhibited an accumulation of Aβ-like pathology in AD mouse models and prevented a development of behavioral deficits without signs of toxicity in the brains of aged transgenic mice (e.g. microhemorrhages, accumulation of T cells, B cells and macrophages, etc). It has been reported that such vaccines are potent only when vaccination is initiated at very low levels of AD-like pathology [41]. Nevertheless, currently several active epitope vaccines (ACC-001, V-950, CAD-106, UB-311, AFFITOPE AD01-03) are being evaluated in phase I or II clinical trials in patients with mild to moderate AD [9, 25-28], and so far immunological data from only CAD-106 trial has been published [25].

We were the first group to report on a DNA vaccine based on full-length Aβ42 peptide [29], as well as on second [24, 32] and third [30, 31] generation DNA epitope vaccines that have been tested in APP/Tg mice, rabbits, and monkeys. Shortly other groups followed this vaccination strategy targeting full-length Aβ42 in mice [42] and then in monkeys [43, 44]. The recent study with our advanced DNA epitope vaccine, AV-1955, demonstrated strong immunogenicity, relative safety, since it did not induce potentially harmful autoreactive Th cells, but generated therapeutically potent IgG antibodies in macaques [30]. In this new study, as an attempt to move closer to clinical trials, we have characterized for the first time the repertoires of B and T cell responses in vaccinated NHP that not only have Aβ42 sequences identical with human one, but also share about 93% of their DNA sequences identified so far, and these animals have been critically important in vaccine research [45]. Significantly, to increase the ability of this DNA epitope vaccine to cover the tremendous diversity of the MHC class II genes in the human population, we generated a novel AV-1959 construct by adding three new promiscuous Th epitopes from TT to MultiTEP platform of AV-1955 (Fig. 1A).

Prior to testing DNA vaccines in NHP we first mapped B and T cell epitopes in mice of H-2b immune haplotype immunized with AV-1955 and AV-1959. Our data showed that AV-1959 generated significantly stronger humoral and cellular immune responses in inbred mice than AV-1955 vaccine (Fig. 2A, 3A). At the same time, mapping of the B cell repertoire demonstrated that both vaccines induced production of anti-Aβ antibodies that strongly recognized AEFRH sequence of Aβ peptide; removal of the alanine residue significantly abrogated binding affinity of these antibodies (Fig. 2B, C). Importantly, analyses of T cell repertoires indicated that significantly stronger cellular immune responses in mice immunized with AV-1959 (Fig. 3A) are likely associated with two new Th epitopes, P7 and P17, added to the MultiTEP platform of this vaccine (Fig. 3B, C). Therefore, the data generated in inbred mice indicate that AV-1959 epitope vaccine may be a better candidate for clinical trials.

Next, as mentioned above, we compared AV-1959 vaccine with its prototype, AV-1955, in non-inbred, higher order species with polymorphic MHC class II genes (Fig. 1C). Rhesus macaques not only have the same Aβ sequence as humans, but their immune system is also closely related to that of humans. In contrast to the mouse studies, we found that immunizations of NHP with either vaccine induced similar levels of humoral and cellular immune responses (Fig. 4A, B and 5A). However, it should be mentioned that macaques from Groups 1 and 2 received different doses of vaccines during the whole study: each animal from group 1 obtained 1.6 mg of AV-1955 and 8 mg of AV-1959, while each macaque from group 2 received 24 mg of AV-1955 (Fig. 1C). In addition, one macaque in group 1 that responded poorly to 8 mg AV-1959 vaccinations (Fig. 4B) was almost not responding to immunizations with 1.6 mg of AV-1955 prior to switching of vaccines [30], indicating that this monkey may have immunodeficiency.

Mapping of B cell epitopes showed that sera from vaccinated macaques bound slightly better to DAEFRH than AEFRH sequence of Aβ42 (Fig. 4E, F). It is still possible that a free aspartic acid is the best immunogen for generation of strong anti-Aβ antibody responses in humans, as was suggested from AN-1792 study [37] and should be studied further in future human trials. Notably, our DNA vaccines have at least one B-cell epitope, Aβ1-11, that possessed a free aspartic acid [31]. It should be emphasized that immune sera isolated from all ten vaccinated macaques do not recognize any peptides incorporated into MultiTEP platform (Fig. 4G). This is extremely important, because antibodies specific to MultiTEP platform may more rapidly clear AV-1955 or AV-1959 from the body and decrease the immunogenicity of the vaccines in humans after booster injections. In fact, longitudinal data from a previous study [30] and the present work reveal that AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines are effective in long-term production of Aβ-specific antibodies (Fig. 4A); even at week 106 (58 weeks after the last boost) 4 of 5 animals in AV-1955 immunized group (with titers 1:275; 1:550; 1:550 and 1:1100) and in 3 of 5 animals in AV-1959 immunized group (with titers 1:137.5; 1:137.5 and 1:250) have detectable antibody titers. In contrast, the CAD-106 vaccine elicited both anti-Aβ antibodies and antibodies specific to carrier bacteriophage (Qβ) in all vaccinated monkeys [46] and in 34 of 46 vaccinated patients [25], and this may explain why the titers of antibodies against Aβ peptide declined rapidly in vaccinated individuals. Although no published data are available regarding ACC-001, the probability that multiple injections with ACC-001 may induce a strong antibody response specific to the carrier protein (CRM197) is quite high [47]. The finding that the antibody responses waned over time could be important because if unwanted side effects are observed, diminishing immune responses may help to reduce the severity/length of the effects. The results of this study will definitely influence the selection of administration schedules (number of immunizations and frequency) to evaluate in humans, however, it is not clear whether more frequent administration would increase antibody titers. As in the NHP, in humans it may be that initial priming sequence followed by a rest period before further administrations may be effective in generating long-term production of Aβ-specific antibodies.

Perhaps the most important data from this study are associated with the mapping of Th responses in NHP. In vaccinated macaques, both AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines activated a broad repertoire of Th cells specific to PADRE and 10 out of 11 of other peptides from different pathogens incorporated into the MultiTEP platform design (Fig. 5B and Table 1). In addition, to identify the broad spectrum and strength of cellular responses to vaccination, we determined the differences in the prevalence of Th epitopes of AV-1955 and AV-1959 vaccines. Specifically, the PADRE epitope was active in all vaccinated NHP, whereas P32, P21, P2, HBVnc and P17 were active in 50-60% of NHP. The P7 peptide did not induce T cell response in any macaque, although it is known to be immunogenic in humans, while the remaining Th epitopes from MultiTEP platform were active in only 20-30% of the immunized NHPs. Collectively, analysis of Th cell epitope mapping in vaccinated NHP clearly demonstrated the broad, individualized repertoire of anti-MultiTEP specific Th cells and suggested that AV-1959 vaccine could be superior to the AV-1955 vaccine because it can stimulate immune responses in a broader population of vaccinated subjects with high MHC class II genes polymorphisms. Importantly, the design of AV-1959 vaccine may activate both naïve and memory Th cells, which could be beneficial for overcoming age-associated changes to T cell immunity that result in decreasing proportions of naïve cells and increasing proportions of memory cells in humans [48]. In fact, we recently reported that memory Th cells specific to P30 epitope of TT may improve immune responses dramatically after single immunization with pharmaceutical grade recombinant epitope vaccine [21]. In turn, activation of naïve and pre-existing memory Th cells may help to induce high titers of therapeutically potent anti-Aβ antibody responses, as we showed in NHP vaccinated with AV-1955 and AV-1959 (Fig. 4B).

However, we realize that even the most immunogenic AD vaccine targeting pathological Aβ may not be therapeutic if vaccination is initiated in late stages of AD. Recent data indicate that even in patients with the earliest stages of AD, neuropathological changes are already established, as illustrated by the prevalence of diffuse and neuritic plaques, as well as neuronal loss [49]. The model of the major biomarkers of AD [50] also indicates that Aβ pathology emerges many years prior to accumulation of tau pathology and even more years before the first signs of cognitive impairment. In fact, published data from the first AN-1792 active vaccination trial [10] and two recently completed passive vaccinations trials from Pfizer/Janssen AIP [17] and Eli-Lilly [16] indicated that anti-Aβ immunotherapy might be effective only when initiated very early in AD pathology (prodromal AD), or even in asymptomatic subjects at AD risk. More specifically, it was reported that administration of bapineuzumab failed to improve cognitive or functional performance in ApoE ε4 carriers and non-carriers with mild to moderate AD compared with the placebo group. However, in some cases administration of bapineuzumab significantly reduced the amyloid burden and CSF p-tau in patients with mild to moderate AD pathology [17, 51, 52]. Solanezumab was also not effective in two separate studies; however, analysis of pooled data across both studies showed a statistically significant slowing of cognitive decline in vaccinated patients with mild, but not moderate AD [16].

Therefore, we believe that to be effective AV-1959 vaccination should be initiated in asymptomatic subjects as early as possible in order to not only effectively reduce brain Aβ-pathology, but also to inhibit tau pathology and preserve cognitive functions. Interestingly, our previous in vitro data strongly suggest that preventive vaccination may protect from AD or may delay the onset of the disease, whereas therapeutic vaccination cannot disrupt the toxic oligomers and may only minimally alleviate preexisting AD pathology [53]. Recently, the National Alzheimer's Project also proposed to initiate anti-Aβ clinical trials in prodromal AD subjects and/or pre-symptomatic FAD subjects whose disease progression is well-defined and predictable, and who ultimately will succumb to the disease. It is believed that a passive vaccination strategy is not practical for preventive treatment due to the costs associated with long-term treatment, and that future studies should show whether an immunogenic AD active vaccine targeting the right pathological proteins, such as Aβ, tau, α-syn, ApoE4 or combinations of these molecules could be safe (will not activate potentially harmful cellular responses) and effective (will induce therapeutically potent antibodies). Of note, so far the FDA has approved only one therapeutic vaccine (sipuleucel) that can increase the median overall survival time of prostate cancer patients up to 4.5 months.

Research in Context

Systematic review

Active immunotherapy is a promising treatment for patients at early stages of AD to prevent, slow down or stop the development and progression of disease. Safe and effective vaccine should be capable to induce high titers of therapeutically potent anti-Aβ antibodies in a broad population of AD patients with high polymorphism of MHC class II genes without activation of harmful autoreactive T cells.

Interpretation

DNA-based epitope vaccines AV-1955 and AV-1959 composed of a short Aβ B cell epitope, conjugated to the string of nine or twelve foreign Th cell epitopes, respectively, are prospective candidates for prevention of AD. Delivered by EP system both vaccines induced strong anti-Aβ antibody responses, generated strong cellular immune responses to foreign epitopes, eliminated activation of autoreactive T cells, and diminished variability of immune responses due to MHC Class II diversity in macaques. Two additional epitopes in AV-1959 are immunogenic in macaques making this vaccine superior to AV-1955.

Future directions

By completion of preclinical safety/toxicity studies human clinical testing of AV-1959 vaccine will be initiated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jason Goetzmann at the New Iberia Research Center for his assistance in overseeing the macaque study. We are grateful to Dr. C.F. Evans, Mr. D. Hannaman, Mr. B. Ellefsen and L. Tichenor from Ichor Medical Systems for their invaluable help coordinating this study. We would like to thank Anna Poghosyan for her help in some experimental procedures. We acknowledge the expert assistance of Shari Piaskowski from Watkins Lab, UW AIDS Vaccine lab (Madison, WA) during the optimization of the NHP ELISPOT assay. This work was supported by the NeuroImmune LLC, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (U44NS065518; “A Therapeutic DNA Epitope Vaccine for Alzheimer's Disease” and R01-NS50895; “Combining AD epitope vaccine with innate immunity”), National Institute on Aging (R01-AG20241; “Multiple approaches to Aβ vaccination in animal models”) and Alzheimer's Association (IIRG-12-239626; “Immune Mechanisms Involved in Responses to Multiepitope AD Vaccine” and NIRG-13-281227; “Detection of B cells producing antibodies: a novel blood-test for AD”). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health and Alzheimer's Association. HD was supported by NIA T32 training grant (AG000096).

Abbreviations

- AD

Alzheimer's disease

- Aβ

amyloid β

- Th epitope

T helper epitope

- APP

amyloid precursor protein

- Tg

transgenic

- PADRE

Pan DR Epitope

- TT

Tetanus Toxin

- HBsAg

Hepatitis B surface Antigen

- HBVnc

Hepatitis B nuclear capsid protein

- MT

Influenza Matrix protein

- MHC

Major Histocompatibility Complex

- PBMC

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cell

- NHP

Non-Human Primate

- IFN-

Interferon, Gamma

- SD

Standard Deviation

- TCR

Th cell receptor

- BCR

B cell receptor

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- FAD

familial Alzheimer's disease

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hardy JA, Higgins GA. Alzheimer's disease: the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Science. 1992;256:184–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1566067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297(5580):353–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1072994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haass C, Selkoe DJ. Soluble protein oligomers in neurodegeneration: lessons from the Alzheimer's amyloid beta-peptide. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8(2):101–12. doi: 10.1038/nrm2101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klyubin I, Walsh DM, Lemere CA, Cullen WK, Shankar GM, Betts V, et al. Amyloid beta protein immunotherapy neutralizes Abeta oligomers that disrupt synaptic plasticity in vivo. Nat Med. 2005;11(6):556–61. doi: 10.1038/nm1234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salomone S, Caraci F, Leggio GM, Fedotova J, Drago F. New pharmacological strategies for treatment of Alzheimer's disease: focus on disease modifying drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2012;73(4):504–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.04134.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schenk D, Hagen M, Seubert P. Current progress in beta-amyloid immunotherapy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2004;16(5):599–606. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orgogozo JM, Gilman S, Dartigues JM, Laurent B, Puel M, Kirby LC, et al. Subacute meningoencephalitis in a subset of patients with AD after Abeta42 immunization. Neurology. 2003;61(1):46–54. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000073623.84147.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schenk D. Opinion: Amyloid-beta immunotherapy for Alzheimer's disease: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3(10):824–8. doi: 10.1038/nrn938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lobello K, Ryan JM, Liu E, Rippon G, Black R. Targeting Beta amyloid: a clinical review of immunotherapeutic approaches in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Alzheimers Dis. 2012;2012:628070. doi: 10.1155/2012/628070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gilman S, Koller M, Black RS, Jenkins L, Griffith SG, Fox NC, et al. Clinical effects of Abeta immunization (AN1792) in patients with AD in an interrupted trial. Neurology. 2005;64(9):1553–62. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000159740.16984.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holmes C, Boche D, Wilkinson D, Yadegarfar G, Hopkins V, Bayer A, et al. Long-term effects of Abeta42 immunization in Alzheimer's disease: follow-up of a randomised, placebo-controlled phase I trial. Lancet. 2008;372(9634):216–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicoll JA, Barton E, Boche D, Neal JW, Ferrer I, Thompson P, et al. Abeta species removal after abeta42 immunization. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2006;65(11):1040–8. doi: 10.1097/01.jnen.0000240466.10758.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Patton RL, Kalback WM, Esh CL, Kokjohn TA, Van Vickle GD, Luehrs DC, et al. Amyloid-beta peptide remnants in AN-1792-immunized Alzheimer's disease patients: a biochemical analysis. Am J Pathol. 2006;169(3):1048–63. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiskopf D, Weinberger B, Grubeck-Loebenstein B. The aging of the immune system. Transpl Int. 2009;22(11):1041–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2009.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeMattos RB, Bales KR, Cummins DJ, Dodart JC, Paul SM, Holtzman DM. Peripheral anti-A beta antibody alters CNS and plasma A beta clearance and decreases brain A beta burden in a mouse model of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(15):8850–55. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151261398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eli La CA. Eli Lilly and Company Announces Top-Line Results on Solanezumab Phase 3 Clinical Trials in Patients with Alzheimer's Disease. 2012 Available at http://newsroom.lilly.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=702211.

- 17.Johnson JA. Johnson & Johnson Announces Discontinuation Of Phase 3 Development of Bapineuzumab Intravenous (IV) Mild-To-Moderate Alzheimer's Disease. 2012 Found at http://www.jnj.com/connect/news/all/johnson-and-johnson-announces-discontinuation-of-phase-3-development-of-bapineuzumab-intravenous-iv-in-mild-to-moderate-alzheimers-disease.

- 18.Agadjanyan MG, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Vasilevko V, Movsesyan N, Mkrtichyan M, et al. Prototype Alzheimer's disease vaccine using the immunodominant B cell epitope from beta-amyloid and promiscuous T cell epitope pan HLA DR-binding peptide. J Immunol. 2005;174(3):1580–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghochikyan A. Rationale for peptide and DNA based epitope vaccines for Alzheimer's disease immunotherapy. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8(2):128–43. doi: 10.2174/187152709787847298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petrushina I, Ghochikyan A, Mktrichyan M, Mamikonyan G, Movsesyan N, Davtyan H, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Peptide Epitope Vaccine Reduces Insoluble But Not Soluble/Oligomeric A{beta} Species in Amyloid Precursor Protein Transgenic Mice. J Neurosci. 2007;27(46):12721–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3201-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davtyan H, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Davtyan A, Poghosyan A, et al. Immunogenicity, Efficacy, Safety, and Mechanism of Action of Epitope Vaccine (Lu AF20513) for Alzheimer's Disease: Prelude to a Clinical Trial. J Neurosci. 2013;33(11):4923–34. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4672-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu B, Frost JL, Sun J, Fu H, Grimes S, Blackburn P, et al. MER5101, a Novel Abeta1-15:DT Conjugate Vaccine, Generates a Robust Anti-Abeta Antibody Response and Attenuates Abeta Pathology and Cognitive Deficits in APPswe/PS1DeltaE9 Transgenic Mice. J Neurosci. 2013;33(16):7027–37. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5924-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wiessner C, Wiederhold KH, Tissot AC, Frey P, Danner S, Jacobson LH, et al. The second-generation active Abeta immunotherapy CAD106 reduces amyloid accumulation in APP transgenic mice while minimizing potential side effects. J Neurosci. 2011;31(25):9323–31. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0293-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Movsesyan N, Ghochikyan A, Mkrtichyan M, Petrushina I, Davtyan H, Olkhanud PB, et al. Reducing AD-like pathology in 3×Tg-AD mouse model by DNA epitope vaccine- a novel immunotherapeutic strategy. PLos ONE. 2008;3(5):e21–24. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winblad B, Andreasen N, Minthon L, Floesser A, Imbert G, Dumortier T, et al. Safety, tolerability, and antibody response of active Abeta immunotherapy with CAD106 in patients with Alzheimer's disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, first-in-human study. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11(7):597–604. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabira T. Immunization therapy for Alzheimer disease: a comprehensive review of active immunization strategies. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2010;220(2):95–106. doi: 10.1620/tjem.220.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lemere CA, Masliah E. Can Alzheimer disease be prevented by amyloid-beta immunotherapy? Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6(2):108–19. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2009.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Delrieu J, Ousset PJ, Caillaud C, Vellas B. ‘Clinical trials in Alzheimer's disease’: immunotherapy approaches. J Neurochem. 2012;120(Suppl 1):186–93. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2011.07458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghochikyan A, Vasilevko V, Petrushina I, Tran M, Sadzikava N, Babikyan D, et al. Generation and chracterization of the humoral immune response to DNA immunization with a chimeric b-amyloid-interleukin-4 minigene. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33(12):3232–41. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans CF, Davtyan H, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Davtyan A, Hannaman D, et al. Epitope-based DNA vaccine for Alzheimer's disease: Translational study in macaques. Alzheimers Dement. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.04.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ghochikyan A, Davtyan H, Petrushina I, Hovakimyan A, Movsesyan N, Davtyan A, et al. Refinement of a DNA based Alzheimer's disease epitope vaccine in rabbits. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(5):1002–10. doi: 10.4161/hv.23875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davtyan H, Ghochikyan A, Movsesyan N, Ellefsen B, Petrushina I, Cribbs DH, et al. Delivery of a DNA Vaccine for Alzheimer's Disease by Electroporation versus Gene Gun Generates Potent and Similar Immune Responses. Neurodegener Dis. 2012;10(1-4):261–4. doi: 10.1159/000333359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cribbs DH, Ghochikyan A, Tran M, Vasilevko V, Petrushina I, Sadzikava N, et al. Adjuvant-dependent modulation of Th1 and Th2 responses to immunization with beta-amyloid. Int Immunol. 2003;15(4):505–14. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxg049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Town T, Tan J, Sansone N, Obregon D, Klein T, Mullan M. Characterization of murine immunoglobulin G antibodies agaisnt human amyloid-b 1-42. Neuroscience Letters. 2001;307:101–04. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)01951-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dickey CA, Morgan DG, Kudchodkar S, Weiner DB, Bai Y, Cao C, et al. Duration and specificity of humoral immune responses in mice vaccinated with the Alzheimer's disease-associated beta-amyloid 1-42 peptide. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;(20):723–29. doi: 10.1089/10445490152717587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemere CA, Maron R, Selkoe DJ, Weiner HL. Nasal vaccination with beta-amyloid peptide for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. DNA Cell Biol. 2001;20:705–11. doi: 10.1089/10445490152717569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee M, Bard F, Johnson-Wood K, Lee C, Hu K, Griffith SG, et al. Abeta42 immunization in Alzheimer's disease generates Abeta N-terminal antibodies. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(3):430–5. doi: 10.1002/ana.20592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.James EA, Bui J, Berger D, Huston L, Roti M, Kwok WW. Tetramer-guided epitope mapping reveals broad, individualized repertoires of tetanus toxin-specific CD4+ T cells and suggests HLA-based differences in epitope recognition. Int Immunol. 2007;19(11):1291–301. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxm099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Groot N, Doxiadis GG, De Groot NG, Otting N, Heijmans C, Rouweler AJ, et al. Genetic makeup of the DR region in rhesus macaques: gene content, transcripts, and pseudogenes. J Immunol. 2004;172(10):6152–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Alexander J, Sidney J, Southwood S, Ruppert J, Oseroff C, Maewal A, et al. Development of high potency universal DR-restricted helper epitopes by modification of high affinity DR-blocking peptides. Immunity. 1994;1(9):751–61. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(94)80017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou J, Fonseca MI, Kayed R, Hernandez I, Webster SD, Yazan O, et al. Novel Abeta peptide immunogens modulate plaque pathology and inflammation in a murine model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2005;2:28. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-2-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qu B, Rosenberg RN, Li L, Boyer PJ, Johnston SA. Gene vaccination to bias the immune response to amyloid-beta peptide as therapy for Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2004;61(12):1859–64. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.12.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qu BX, Xiang Q, Li L, Johnston SA, Hynan LS, Rosenberg RN. Abeta42 gene vaccine prevents Abeta42 deposition in brain of double transgenic mice. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260(1-2):204–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2007.05.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tokita Y, Kaji K, Lu J, Okura Y, Kohyama K, Matsumoto Y. Assessment of non-viral amyloid-beta DNA vaccines on amyloid-beta reduction and safety in rhesus monkeys. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010;22(4):1351–61. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2010-100978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zahn LM, Jasny BR, Culotta E, Pennisi E. A Barrel of Monkey Genes. Science. 2007;316(5822):215. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imbert G, Marrony S, Ulrich P, Goldsmith P. Antibody immune response in cynomolgus mmonkeys following treatment with the active Aβ immunotherapy CAD106 Alzheimer's & Dementia: Journal of Alzheimer's Association. 2009;5(4) Suppl:427. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Del Giudice G. New carriers and adjuvants in the development of vaccines. Curr Opin Immunol. 1992;4(4):454–9. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(06)80038-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Derhovanessian E, Solana R, Larbi A, Pawelec G. Immunity, ageing and cancer. Immun Ageing. 2008;5:11. doi: 10.1186/1742-4933-5-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tarawneh R, Holtzman DM. Critical issues for successful immunotherapy in Alzheimer's disease: development of biomarkers and methods for early detection and intervention. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8(2):144–59. doi: 10.2174/187152709787847324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jack CR, Jr, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Aisen PS, Trojanowski JQ, et al. Evidence for ordering of Alzheimer disease biomarkers. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(12):1526–35. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2011.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sperling R, Salloway S, Raskind MA, Ferris S, Liu E, Yuen E, et al. A randomized double-blind, placebocontrolled clinical trila of intravenous bapineuzumab in patients with Alzheimer's disease who are apolipoprotein E ε4 carriers; 16th Congress of the European Federation of Neurological Societies; 2012; Stokholm, Sweden. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salloway S, Sperling R, Honig L, Porsteinsson A, Sabbagh M, Liu E, et al. A randomized double-blind, placebocontrolled clinical trila of intravenous bapineuzumab in patients with Alzheimer's disease who are apolipoprotein E ε4 non-carriers; 16th Congress of the European Federation of Neurological Societies; 2012; Stokholm, Sweden. 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mamikonyan G, Necula M, Mkrtichyan M, Ghochikyan A, Petrushina I, Movsesyan N, et al. Anti-Abeta 1-11 antibody binds to different beta-amyloid species, inhibits fibril formation, and disaggregates preformed fibrils, but not the most toxic oligomers. J Biol Chem. 2007;(282):22376–86. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M700088200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]