Abstract

Keloids and hypertrophic scars are prevalent disabling conditions with still suboptimal treatments. Basic science and molecular-based medicine research has contributed to unravel new bench-to-bedside scar therapies, and to dissect the complex signaling pathways involved. Peptides such as transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) superfamily, with SMADs, Ski, SnoN, Fussels, endoglin, DS-Sily, Cav-1p, AZX100, thymosin-β4 and other related molecules may emerge as targets to prevent and treat keloids and hypertrophic scars. The aim of this review is to describe the basic complexity of these new molecular scar management strategies, and point out new fibrosis research lines.

1. INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous scar management has relied heavily on the experience of practitioners rather than on the results of large-scale randomized, controlled trials and evidence-based techniques [1]. Massage therapy, adhesive tape support, silicone gel-sheeting, pressure therapy, intralesional corticoids, laser, radio and immunotherapies, antimetabolites and botulinum toxin A represent the most popular strategies for keloids and hypertrophic scar management [1, 2]. Being severe and mild forms of excessive scarring, respectively, keloids particularly extend beyond the original wound margins, in contrast to hypertrophic scars. However, both abnormal wound healing processes still remain as unresolved problems, potentially causing a severe impairment of quality of life in affected patients [3]. New developments in molecular and regenerative medicine emerge as key tools to design new excessive scar preventive and therapeutic options. These include the superfamily of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) [4], with its complex signaling crosstalks with other cytokines and pathways. Hence, this complexity is even enlarged by cell context characteristics, multiple on/off regulatory switches, and especially sequential timing and age differences during the per se complex wound healing cascade [4, 5]. Indeed, it is noteworthy to consider that this subtle properties warrant that pre-clinical research with TGF-β should be carefully conducted and analyzed and, even so, it may have unexpected or non-reproducible consequences in vivo. The aim of this review is to describe current research targets on keloid and hypertrophic scars and shed new light into the complex TGF-β derivatives and its basics (first part of molecular introduction) , with an special focus on its clinical translation (second part of the manuscript).

2. HUMAN RECOMBINANT TGF-β3 AND TGF-β SUPERFAMILY-RELATED PRODUCTS

The scarless healing of cutaneous wounds (regeneration instead of reparation) in early gestational fetuses has been suggested to occur due to the predominance of the antifibrotic TGF-β3 (transforming growth factor- beta3) isoform over the profibrotic TGF-β1 and 2, as well as an immaturation of the cellular immune response [4, 6]. TGF-β1 has been reported to decrease collagen III expression in fetal murine skin fibroblasts [7]. Hence, in contrast to adult cells, early gestational fetuses show predominance of type III collagen over type I: from the normal 20%, type III collagen increases to 50%; this increase causes decreased fibril diameter [8]. Early gestational fetuses also display significant expression of hyaluronan [9] and fibromodulin [10], which are known to suppress TGF-β activity [10]. It has been reported that the described scarless phenomenon in early gestational phases is independent of the intrauterine environment, but dependent on the particular fetal fibroblast [4]. Development of hypertrophic scars and other fibrotic diseases is linked to over-expression of TGF-β1 and its downstream mediators CTGF (connective tissue growth factor) and PAI-1 (plasminogen activator inhibitor-1), among others [11].

2.1. DESCRIPTION OF THE TGF-β SUPERFAMILY

The TGF-β superfamily of growth factors includes not only TGF-β but also other peptides (Figure 1). The TGF-βs are homodimers consisting of two identical subunits of ~12 kDa each. In the animal kingdom there are currently five distinct isoforms or ligands of TGF-β with 64-82% identity, with only the TGF-β1, -β2 and -β3 forms expressed in mammalian tissues. TGF-β1 was the first discovered member of the family, and it was first characterised in human placenta in 1983. In humans, the three isoforms are located on three different chromosomes, 19q13, 1q41 and 14q24. Each isoform has specific functions but structural and signaling pathways similarity [12].

Figure 1. COMPONENTS OF THE TGF-β SUPERFAMILY.

*Note that there are also TGF-β4 and 5, but not in humans. TGF-β = Transforming growth factor beta; AMH= Antimüllerian hormone; BMPs= Bone morphogenetic proteins.

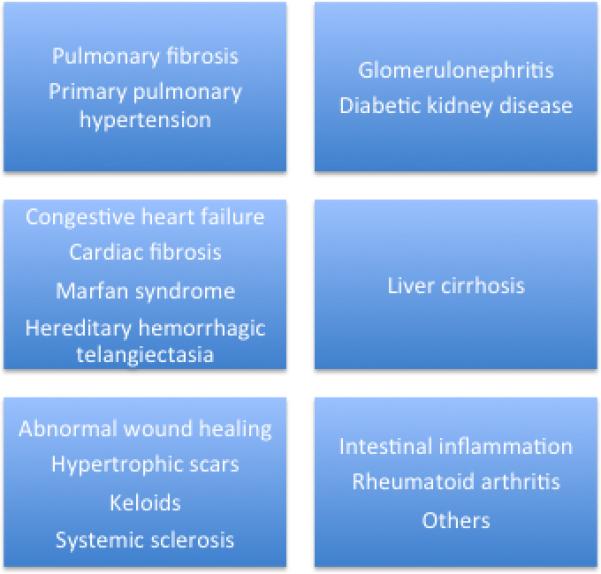

TGF-β family members are widely expressed in all cells. They control cellular behaviour in embryonic and adult tissues, including cell proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, migration, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling, immune functions, and tumor invasion/metastasis [13-17]. Therefore, they play crucial roles in embryonic development, adult tissue homeostasis and the pathogenesis of a large group of high prevalent diseases, including fibrosis, cancer (where they can be oncogenic or anti-tumor agents), autoimmune and cardiovascular illnesses, among others [14, 18-20] (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

TGF-β-RELATED DISEASES.

Regarding wound healing, TGF-β plays a major role and it is produced by all cells participating in the wound healing process, mainly the adult macrophage [21]. It regulates stem cell availability [22] and cellular behavior within the wound microenvironment [23]. It also modulates production of ECM, as well as migration, chemotaxis and proliferation of macrophages, fibroblasts of the granulation tissue, epithelial and capillary endothelial cells. In the initiation of wound healing, platelet alpha granules release TGF-β, which then activates production of TGF-β by other cells including keratinocytes and fibroblasts, and both recruit macrophages, which release more TGF-β [24]. TGF-β has also a self-inhibitory feedback loop, and subtle perturbation of this serial complex orchestrated signaling pathway may have detrimental consequences and unexpected results [5].

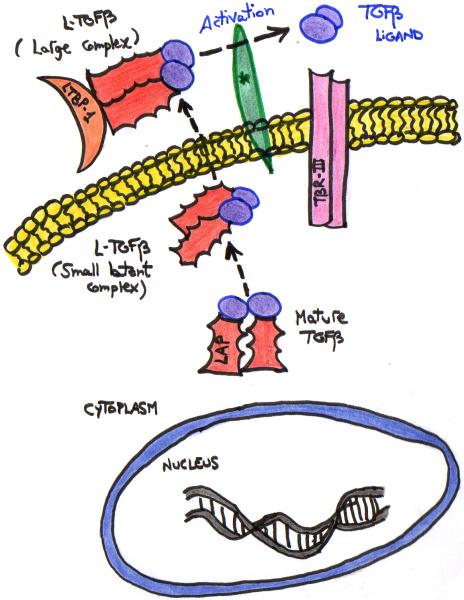

2.2. SECRETION OF TGFβ

Mature TGF-β, a 24-kDa homodimer, is noncovalently associated with the 80-kDa “TGF-β propeptide dimer”, also known as LAP (“Latency-Associated Peptide”). This complex of TGF-β plus LAP is called the small latent complex [12, 25]. This Latent TGF-β (LTGF-β) complex is secreted by all cells and is abundant both in circulating forms and bound to the extracellular matrix [12]. LAP is a fundamental component of TGF-β that is required for its efficient secretion; LAP regulates TGF-β latency. LAP exists in three isoforms: LAP-β1, 2 and 3 [13]. LTGF-β binds to LTBP-1 (the Latent TGF-β-Binding Protein 1), forming the “Large, Latent Complex” (LLC) (Figure 3). LTBP-1 belongs to a family of extracellular glycoproteins that includes three other isoforms (LTBP-2, -3 and -4) and the matrix protein fibrillin-1 and -2 [12, 14]. Indeed, like TGF-β1, fibrillin-1 is upregulated in keloids, suggesting that fibrillin-1 may play a role in keloid formation and may be considered a scar specific gene [26]. Next, newly synthesized TGF-β is released from most cells as the LLC or dimeric pro-hormones [12, 15]. How TGFβ is released and activated from the LLC is complex and still not clear [12, 13] (Figure 3).

Figure 3. SECRETION OF TGF-β.

TGFβ is secreted from the cells in a latent inactivated form, which is then cleaved by furins and other convertases to form active signaling molecules. *Mechanisms to activate latent TGFβ-complexes are only partially understood and include proteases such as plasmin, calpain and matrix metalloproteinases, protein interactions with molecules such as thrombospondin and integrin αvβ6, physicochemical mechanisms such as pH, radiation and reactive oxygen species, and drugs such as antiestrogens, retinoids and glucocorticoids [25].

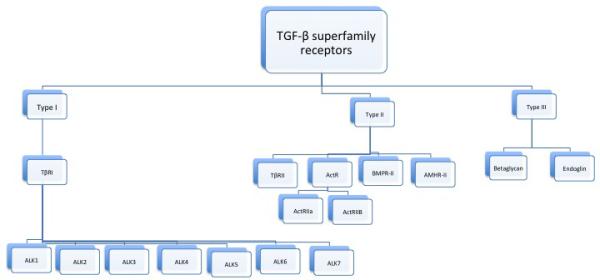

2.3. TGF-β RECEPTORS

TGF-β is considered to have three receptors: TβRII (TGF-β type II receptors, which include TβRII, ActR-IIa, ActR-IIB, BMPR-II and AMHR-II), TβRI (TGF-β type I receptors, named ALK 1-7 or activin receptor-like kinases 1-7) and TβRIII (TGF-β type III receptors: betaglycan and endoglin) (Figure 4) [12, 15, 27]. The most important ones are the TGF-β type II receptors. All the TGF-β receptors have a characteristic structure that includes a short cysteine-rich extracellular domain, a single transmembrane domain, and an intracellular serine/threonine kinase domain [28]. Type I and II receptors are membrane-bound serine-threonine kinase receptors [29]; they are single-chained glycoproteins of ~55 and 85 kDa, respectively [28]. Type I and II receptors are known as the signaling receptors. Type III receptors transduct themselves no signals, but help TGF-β ligands to better bind to their cognate TGFβ receptors and modulate TGF-β response. Endoglin interacts with TGF-β1 and 3, but not TGF-β2, in contrast to betaglycan [30]. TGF-β signals in most cells via TGF-β type II receptor (TβRII) and ALK5 [15]. ALK5 has been shown to induce the expression of fibronectin and PAI-1. Endoglin is considered to be necessary for TGF-β/ALK1-(Smad1) signaling and it mediates TGF-β induction of ET-1 (endothelin-1), which emerges as a new fibrosis target in the clinic [31]. It also indirectly inhibits TGF-β/ALK5-(Smad2/3) signaling [32]. Receptors regulation is a complex process with multiple players [5] (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

TGF-β SUPERFAMILY RECEPTORS.

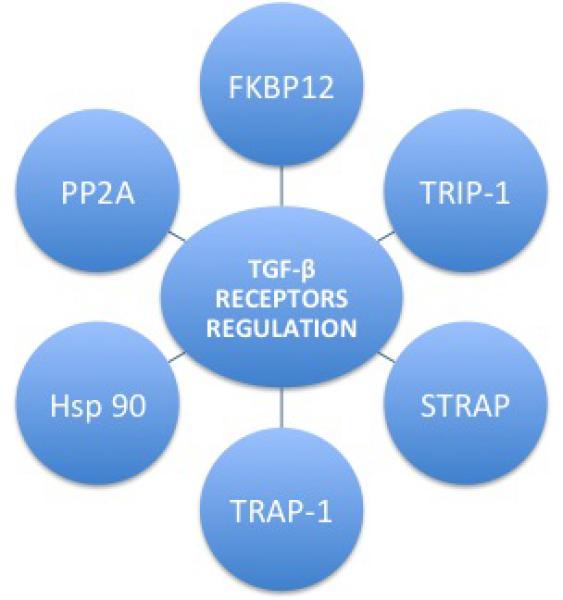

Figure 5. TGF-β SUPERFAMILY RECEPTORS REGULATION.

Phospho-relay from the constitutively active type II receptor to the type I receptor, and subsequently phosphorylation of R-Smads is essential to activate canonical TGFβ superfamily signaling [27]. This process is positively and negatively regulated at all stages of the pathway by various proteins, such as the immunophilin FKBP12 [15], TRIP-1 (the receptor interacting protein 1), the STRAP (Serine-threonine kinase receptor-associated protein), the TRAP-1 (TβRI-associated protein-1), the TLP (a TRAP-1-like-protein), the chaperone protein or Hot Shock Protein 90 (Hsp90), and the protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), among others [27].

2.4. TGFβ SIGNALING

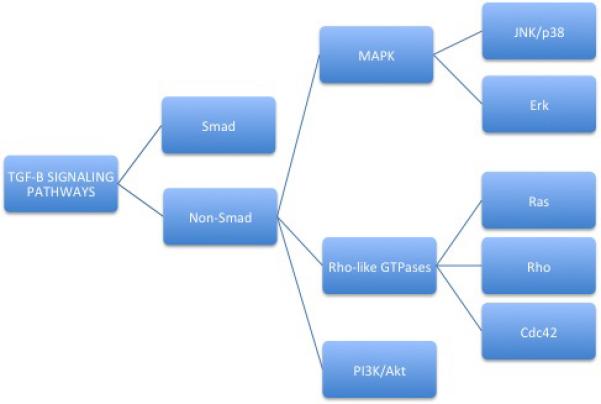

TGFβ(/BMP) signaling is a very complex process, with lots of on-turning/off-turning mechanisms and crosstalks [5, 13, 17]. TGFβ most common signaling pathway involves the Smads proteins, which are intracellular signaling intermediates [5, 12, 27]; however, there are other alternative or non-canonical TGFβ (/BMP) signaling pathways, which involve other signal transducers, such as MAP kinase, Rho-like GTPases, and phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathways, among others [29] (Figure 6).

Figure 6. TGF-β SIGNALING PATHWAYS.

There are two main pathways, Smad (or canonical) and the non-Smad (or non-canonical) pathway, mainly devoted to EMT (epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition) and apoptosis. Furthermore, there are crosstalks with other pathways, such as Wnt/Wg, Hh (Hedgehog), Notch, interleukins, IFN-γ, and TNF-α, among others.

2.4.1. SMAD PROTEINS

Smad proteins are intracellular cytoplasmic entities that act as nuclear transcription factors after activation [18]. They represent the signal transducers of the canonical signaling pathway of the TGF-β family and the nuclear effectors of the TGF-β receptors [25].

“Smad” is an acronym or condensation from “sma” in C elegans and “mad” in Drosophila, both of which regulate growth and development, which are contracted to “smad” [28]. They were uncovered over a decade ago thanks to genetic studies in worms and fruitflies, as a group of genes which appeared to play a crucial role in mediating the intracellular responses to TGFβ and/or its related factors [18, 87]. Subsequent studies demonstrated that Smads are transcription factors that constantly shuttle between the cytoplasm and the nucleus [29, 33, 34].

The Smad family comprises 8 Smad proteins which are subclassified into three groups: Receptor activated or Receptor-regulated Smad proteins (R-Smads: including Smad 1, 2, 3, 5 and 8), common partner or the Common-Smad (Co-Smad or Smad4, named so due its role in all branches of TGFβ superfamily signaling), and the antagonistic or Inhibitory Smads (I-Smads: Smad 6, 7) [5, 15, 18, 27, 33]. Smad6 is thought to function preferentially as an inhibitor of BMP (competing with activated Smad1 for binding to Smad4 [35]) , while Smad7 is a general inhibitor of TGFβ family-induced signals (mainly by binding to the TGF-β type I receptors and preventing phosphorylation of Smads2 and 3, or recruiting ligases that degrade the TGF-β type I and 2 complexes); however, Smad7 also may enhance TGF-β, when binding Smad7 to the deubiquitinating enzyme UCH37 [36]).

Smads 2 and 3 usually mediate the TGF-β pathway, whereas Smad 1, 5 and 8 mediate the BMP signaling [16, 34, 36]. Smad2 and 3 are usually phosphorylated by TGF-β and ALK5 in complex with TβRII, while Smad1, 5 and 8 are phosphorylated by TβRI receptors ALK1 or ALK2, and BMP receptors ALK3 or ALK6 [37] (although in dermal fibroblasts Smad1 may be phosphorylated by ALK1 or ALK5 in response to TGF-β [27]). Smad2 and Smad3 do not compete for receptor binding. Smad4 forms complexes with the receptor activated Smads [12, 28]. Smad3, differently to Smad2, binds directly to DNA [38]. Therefore, TGF-β-mediated Smad responses require additional DNA-binding co-factors, such as the forkhead, homeobox, zinc-finger, bHLH, and AP1 family of transcription factors [15, 17, 27, 28]. These Smad-interacting transcription factors and therefore the resulting effect depends mainly on the initial stimuli that triggered TGF-β signaling.[15].

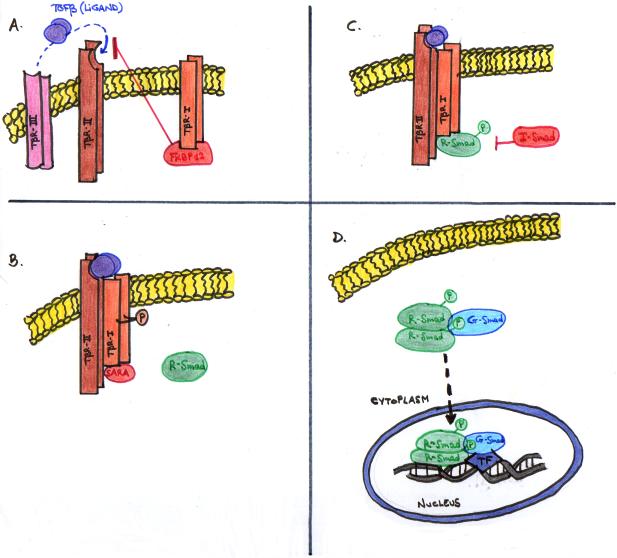

2.4.1.1. SMAD OR CANONICAL TGFβ SIGNALING

When TGF-β ligands reach the membrane of target cells, they bind directly to two TβRII, which come in close contact with two TβRI. In doing so, the constitutively active TβRII trans-phosphorylates and activates TβRI, forming a tetrameric receptor heterocomplex [5] (Figure 7A). TGF-β activated receptor complexes, like other cell surface receptors, can be internalized into the cell via two different routes or vesicles: clathrin- or caveolin-1-positive vesicles [39]. The former way is the most predominant and generally leads to receptor re-cycling and promotion of TGF-β-induced Smad activation and transcriptional responses, whereas the latter one involves cholesterol-rich membrane microdomain lipid rafts/caveolae, degrades the receptors by I-Smads, Smurfs and E3 ubiquitin (Ub) ligases, and therefore turnoffs TGF-β signaling, contributing to its negative feedback loop [5, 39].

Figure 7. CANONICAL TGF-β SIGNALING AND RECEPTORS.

Each of these Smad4-R-Smad-transcription factor complexes recruits co-activators, repressors, and chromatin remodeling factors to selected sequence elements in the regulatory regions of specific target genes [15].

Besides endocytosis of both ligand and receptors, signaling occurs. The activated TβRI propels downstream signaling actions, via Smad protein activation thanks to the release of FKBP12 or FK506-binding protein, a TGF-β signaling inhibitor which interacts with the TβRI in the absence of ligand (Figure 7A) [15, 27]. In more detail, the activated TβRI releases FKBP12 and interacts with an adaptor protein, the Smad Anchor for Receptor Activation (SARA), which recruits the Smads 2/3 and propagates signals to the Smads (Figure 7B) [12]. Smad2 and/or Smad3 are transiently associated with the TβRI, and are directly phosphorylated by the receptor kinase Smads [12]. The phosphorylated Smad dissociates from SARA and then generally forms a heteromeric complex with Smad4 (Figure 7C), and this complex translocates from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where it activates or represses specific target genes (Figure 7D) [12, 27]. However, Smad4-independent signaling events have been also shown in specific cell types, and the core Smad complex may not necessarily contain only Smad proteins [27,]. Regarding Smads positive and negative regulation, phosphorylation of the linker region of the R-Smads by intracelullar protein kinases plays an espcially important role [27].

2.5. SKI FAMILY: SKI, SNON AND FUSSELS

The Ski family of nuclear oncoproteins represses TGF-β signaling, mainly through inhibition of transcriptional activity of Smad proteins. The Ski family comprises the old-known members Ski and SnoN (Ski-novel protein), and the recently undeavoured Fussels, Fussel-18 (Functional Smad suppressing element on chromosome 18) and Fussel-15 (this latter also called LBXCOR1) [40]. Like other TGF-β signaling components, they also emerge as potential targets for scar treatment [41].

2.5.1. Fussels

Both Fussel-18 and Fussel-15 have significant homology with Ski and SnoN, and may interact with R-Smads and inhibit TGF-β or BMP responsive gene expression [40]. In contrast to Fussel-18 that interacts with Smad2, Smad3 and Smad4, and has an inhibitory activity on TGF-β signaling, Fussel-15 interacts with Smad1, Smad2 and Smad3 molecules and suppresses mainly BMP signaling pathway [42]. Unlike Ski and SnoN, which are found in almost all human tissue types, the expression of Fussel-18 and Fussel-15 appears to be limited to neuronal tissues [40]. However, it has been recently found that Fussel-15 might play a role during fibroblast migration, and in keloid and skin sclerosis pathogenesis. It has been shown that these two entities share perpetual and high Fussel-15 expression, although the underlying molecular mechanism still remains unknown [43].

2.5.2. Ski/SnoN

Regarding the classical ski family proteins, Ski and SnoN, both are potent negative regulators of TGF-β signaling and were discovered as oncogenes [40]. However, emerging evidence also suggests a potential anti-oncogenic activity for both, depending mainly on the cell location and expression levels [44]. Although cancer is the best studied pathology where Ski and SnoN are involved, their expression is also altered in other pathologic conditions, such as injured peripheral nerves, wound healing, liver and skeletal regeneration, and obstructive nephropathy [40, 41, 44-48]. Ski is expressed at low levels in normal skin and is highly induced after injury [41]. SnoN is present in keratinocytes [49] and may also play crucial roles in T cell regulation, tissue regeneration and aging. Ski overexpression causes muscle hypertrophy [40]. Recently, Ski has been described as a novel wound healing-related factor that reduces inflammation, promotes fibroblast proliferation but it inhibits collagen secretion. It has been reported that Ski inhibits Smad2/3, decreasing scar in experimental models, and activates non-Smad pathways, improving wound healing. Ski may emerge as a possible treatment for chronic wounds and hypertrophic scars [41]. Both ski and SnoN participate in nerve regeneration; it is yet unknown if Ski would restore nerve regeneration in scar tissue.

2.5.2.1. Structure, protein interactions and the role of Arkadia

The human sno gene is located at 3q26.2, whereas Ski gene is located on chromosome 1p36.3. This chromosome area has been related with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type VI and the 1p36 syndrome. Ski and SnoN contain several structural domains, including the DHD (Dachshund Homology Domain, also called DS domain for DACH, Ski and Sno), and a Smad4 binding domain [40]. Since neither Ski nor SnoN has been shown to directly bind DNA, the DHD may function to modulate interaction of Ski/SnoN with other transcriptional regulator proteins. These proteins include Smads (the most extensively studied, GATA1, gliobastoma protein 3 (Gli3), retinoblastoma protein (pRb), retinoic acid receptor α (RARα), methyl-CpG-binding protein (MeCP2), promyelocytic leukemia protein (PML), c-Jun and PU.1, the vitamin D receptor (VDR), and co-regulators such as histone deacetylases (HDAC), nuclear receptor co-repressor (N-CoR), SMRT (silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors), or mSin3A, among others [40]. One study found VDR in cultured keloid fibroblasts, and vitamin D has been suggested to be helpful in scar management [50]. On the other hand, some of the aforementioned proteins, such as Smads or pRb, are released by SKIP (Ski Interacting Protein), which binds and inhibits Ski. Besides SKIP, other described Ski inhibitors are C184M, TGF-β itself and Arkadia. Arkadia, also known as ring finger 111, is an E3 ubiquitin ligase that enhances transforming growth factor (TGF)-β family signaling through degradation of negative TGF-β signal regulators, not only c-Ski and SnoN, but also Smad7. Similar to other ubiquitin ligases, including Smurf1 and 2, Arkadia regulates signaling pathways other than those of the TGF-β family, like epidermal growth factor (EGF) [40]. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published reports about Arkadia inhibition in scar management. Table 2 is a brief summary of TGF-β-related molecules and actions.

Table 2.

Main mechanisms of action of new peptides related to TGFB1.

| DS-SILY | -Inhibition of MMP-1 and MMP-13 |

| Cav-1p | -Prevention of Smad2/3 phosphorylation -Reduction of TGF-β receptor type I levels -Actin cytoskeleton dynamics regulation |

| AZX100 | - Reduction of TGF-β1-induced CTGF expression |

| Thymosin β(4) | -Inhibition of TNF-α-induced NF-kβ activation -Decrease myofibroblasts in wounds |

2.6. TGF-β-BASED ANTISCARRING DRUGS

2.6.1. Mannose-6-phosphate

As mannose-6-phosphate (M6P) inhibits the activation of TGF-β1 and TGF-β2 [52, 53], local application of recombinant MP6 has been studied to treat scars (clinicalTrials.gov identifiers: NCT00984516 and NCT 00984854) by the pharmacological and biotech company Renovo, using the brand drug name Juvidex® [54]. In March 2009, Renovo reported the results of a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized, phase 2 efficacy trial in almost 200 male and female individuals with Juvidex® at different dosages in split-thickness skin-graft donor sites. 300 mmol/L topical Juvidex® showed a statistical significant acceleration of wound healing, although the trial did not meet its primary endpoint [3]. Due to reduced redness and increased cutaneous radiance observed, topical Juvidex® is offered as a cosmeceutical product to improve overall skin appearance by Renovo, which at the time of this publication intends to sell the Juvidex® programme to a cosmetic company [55]. On the other hand, M6P has also been shown to decrease fibrosis, enhance regeneration and functional outcomes in the acute phase after sciatic nerve injury in a mice model [56].

2.6.2. Inhibition of FAP-α /DPPIV

Inhibition of DPPIV (dipeptidyl peptidase IV)-like enzymatic activity suppresses TGF-β1 and appears also to serve as another novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of excessive skin fibrosis [57, 58]. DPPIV is a protease that promotes cell invasiveness and tumor growth, as well as FAP-α (Fibroblast activation protein α). Keloid fibroblasts are characterized by increased expression of FAP-α, and normal adult tissues are generally FAP-α negative. Therefore, it has been suggested that inhibition of FAP-α/DPPIV activity may be a novel treatment option to prevent keloid progression [58, 59].

2.6.3. Smad3 inhibitors

It is thought that Smad3 phosphorylation and not Smad2 mediates the fibrotic effect of TGF-β [38]. Furthermore, it has been reported that inhibition of Smad3 expression decreases collagen production in keloid fibroblasts [60]. Therefore, inhibitors of Smad3 appear to be promising therapies to treat hypertrophic scars and keloids [38, Such inhibitors are TLP (which in turn coactivates Smad2), halofuginone, quercetin, P144, trichostatin A and paclitaxel, between others [61-64].

Halofuginone, a quinazolinone alkaloid with anti-angiogenic, anti-metastatic and anti-proliferative effects [65], has been topically applied (Tempostatin™) in patients with AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma [66]. Halofuginone is also a selective inhibitor of type-1 collagen synthesis and blocks TGF-β-mediated Smad3 activation in fibroblasts, suppressing dermal fibrosis in vivo [61]. It has been shown to be efficacious to reduce fibrosis in murine sclerodermatous graft versus host disease [67] and in a mouse model of pulmonary fibrosis [68].

Quercetin (3,3',4',5,7- pentahydroxyflavone) is the most common of the flavonoid glycones found in the diet and therefore has antioxidant properties. The richest sources of quercetin are onions, apples, red wine and gingko biloba [62, 69, 70]. Quercetin has antiviral, antiinflammatory, antimicrobial, antifibrotic and pro-apoptotic properties. It inhibits not only Smad3, but also Smad2, Smad4, TGF-β, their co-activator proteins p300 and CBP, PI3-K, and IGF-1 (insulin-like-growth factor-1), eventually blocking fibrosis [62, 71]. Furthermore, quercetin inhibits keloid fibroblast proliferation and collagen production in vitro [62, 72, 73].

Another drug that also inhibits both Smad3 and Smad2, and TGF-β1, leading to reduction of collagen synthesis, myofibroblasts production and dermal thickness, is the peptide P144 [74-76]. P144 is the acetic salt of a 14mer peptide from the human TGF-β1 type III receptor betaglycan [77]. Although P144 has been studied to decrease capsular contracture in pigs with controversial results [78], it was shown to reverse bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis in mice when topically applied [75]. Two other anti-Smad3 drugs, which have been developed mainly as antineoplastic agents, paclitaxel at low doses and trichostatin A (TSA), also prevented bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis in murine models [63, 64].

2.6.4. Smad 7 upregulators

Asiaticoside is a white needle-like crystal phytomolecule, which is extracted from the leaves of the plant Indian pennywort (Centella Asiatica), and it is an ingredient in traditional herbal medicine [79]. It has been reported to activate Smad7 in normal and hypertrophic scar fibroblasts, besides reducing the expression of both TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII, resulting in fibrosis inhibition [79, 80].

Another herbal medicine which also upregulates Smad7 is “Boui” or tetandrine. This drug additionally blocks Smad2/3 [81]. It has been shown that in human hypertrophic scar fibroblasts in vitro it promotes Smad7 expression, it inhibits Smad2, TGF-β1, type I and III collagen synthesis, and shortens the cell cycle [82].

Interferon-γ (IFN-γ) is known to induce endogenous Smad7, and therefore antagonize TGF-β signals [83]. The IFN-γ receptor and its associated protein tyrosine kinase Jak1 mediate phosphorylation and activation of the transcription factor Stat1 [84]. There is crosstalk between the IFN-γ/Stat1 and TGF-β1/Smad signaling pathways in the wound healing process [85]. Another important protein, Y-box protein-1 (YB-1), activated by IFN-γ/Jak1, is believed to be the main mediator of antifibrotic IFN-γ effects, via 2 different ways: directly, inhibiting collagen expression, and indirectly, via TGF-β suppression [83]. Few small population clinical trials have suggested the potential role of IFN-γ to treat abnormal dermal fibrosis [86, 87].

2.6.5: Proteoglycans

Decorin is a proteoglycan, normally prevalent in the dermal ECM [2] but absent for the first year after burn trauma [9], that suppresses TGF-β activity and inhibits collagen synthesis in scar-derived fibroblasts in vitro [88]. Fibromodulin, as well as decorin, is a small-leucine rich proteoglycan, also shown to be reduced in postburn hypertrophic scars. It has been suggested that downregulation of small-leucine rich proteoglycans after wound healing in deep cutaneous injuries plays an important role in the development of fibrosis and hypertrophic scarring [89]. Low decorin and high ERK1,2 levels have been found in earlobe keloids [90].

2.6.6: TGF-β3

Although preclinical studies and preliminary clinical trials have shown thatrecombinant human TGF-β3 (avotermin™, juvista™) has potential to improve and/or prevent scarring [91-94], the Juvista EU phase 3 trial (REVISE study) did not meet its primary or secondary efficacy endpoints as reported on February 2011 by its developing company, Renovo [56]. The firm attributed this unexpected negative results to the fact that in phase III clinical trial they only used half of the Juvista-TGF-β3 amount tested in previous phase I/ II trials [95].

Juvista™ (INN: Avotermin) is an injectable solution of human active recombinant TGFβ-3. More than 5 phase I/II clinical trials established that intradermal avotermin administered at doses of 50 to 500 ng/100 uL/linear centimeter wound margin resulted in statistically significant improvements in scar appearance with no remarkable side effects [93]. Going into more detail, in three double-blind, placebo-controlled phase I/II studies, intradermal avotermin (at concentrations ranging from 0.25 to 500 ng/100 uL per linear cm wound margin) was administered in healthy subjects to both margins of 1 cm full-thickness skin surgical incisions, before wounding and 24 hours later. In both young and old participants, only one dose regimen, 50 ng per 100 uL per linear cm, achieved more than 10% scar improvement in nearly two thirds of wounds. However, in the final phase II study, all doses were judged to be effective by both lay observers and clinicians [1, 92]

2.6.7: Other important TGF-β1 inhibitors

2.6.7.1. HGF

It has been suggested that HGF (hepatocyte growth factor) exerts antifibrotic effects, via the c-met receptor and TGF-β1 inhibition [96], or through peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor- (PPAR)γ agonists [97], among other mechanisms, dependently or independently of TGF-β [98, 99]. It has been shown that local administration of HGF gene enhances the regeneration of dermis and minimizes scarring in acute incisional wounds in an experimental model [100]. Furthermore, it has been reported that HGF has also mitogenic, morphogenic, motogenic, angiogenic, anti or pro-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory properties [96].

2.6.7.2. TAMOXIFEN/ SEX HORMONES

Tamoxifen is a synthetic nonsteroidal antiestrogen, used in the treatment of breast cancer [101]. It has been shown that it decreases TGF-β1 production by keloid and fetal fibroblasts in cell culture, and also TGF-β2 and 3 in higher doses in the former ones. Topical and oral tamoxifen citrate chemical treatment has been shown to improve scarring [102, 103]. However, estradiol has been also suggested to downregulate TGF-β1 [104]. Prospective studies must be performed to validate the use of tamoxifen for the treatment of hypertrophic scars and keloids [105].

2.6.7.3. TACROLIMUS AND RAPAMYCIN

Tacrolimus (previously known as FK-506) is a calcineurin inhibitor mainly used to prevent transplant rejection [106]. It is an immunomodulator and immunosuppressant drug, with anti-inflammatory and antifibrotic properties [107].

It has been reported that intradermal injection of tacrolimus at 0.5 mg/cm2 prevented hypertrophic scarring in an experimental rabbit ear model [107]. Small clinical studies have shown new promise in the use of tacrolimus in the armamentarium against excessive scarring [108]. However, additional clinical trials are warranted.

Rapamycin, also known as sirolimus, is an antiproliferative, antitumor, immunosuppressive and antimicrobial agent which inhibits mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), collagen I synthesis and profibrogenic cytokines such as TGF-β, IL-13, IL-4 and CTGF, therefore decreasing ECM deposition, as well as VEGF [108-111]. Furthermore, PI3k-AKt-mTOR (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin) pathway has been shown to be involved in keloid formation. Therefore, rapamycin emerges as another possible drug to be studied in the treatment of excessive scarring [108].

2.6.7.4. TNF-α

Tumoral Necrosis Factor (TNF)-α is a potent inflammatory cytokine with antagonistic activity towards TGF-β1. TNF-α was found to suppress the TGF-β-induced expression of CTGF protein in cultured normal fibroblasts. The activity of TNF-α has been blocked by NF-kB (nuclear factor kappa B) inhibitors [112]. TNF-α prevents ECM synthesis and α-SMA expression and subsequent myofibroblast differentiation in human dermal fibroblasts [113]. It activates also matrix metalloproteinases [112-114]. Although it has been reported that TNF-α levels are decreased in hypertrophic scars after burn injury [115], and TNF-α may represent a strategy to treat excessive scarring [116], there is controversial literature surrounding this topic. Many studies state that TNF-α levels are enhanced in hypertrophic scars [117] and etanercept, a TNF-α antagonist, has also been studied as a possible scar minimizer [118]. According to this latter, it has been postulated that TNF-α may lead to keloidal scarring via NF-kB-induced COX-2 overexpression in fibroblasts [119]. Furthermore, it is supposed that compression therapy reduces TNF-α levels [117].

2.7. OTHER NEW PEPTIDES

DS-SILY (a decorin mimetic) [120-121], Cav-1 cell-permeable peptides (cav-1p, which are reduced in keloid fibroblasts) [122, 123], AZX100 (an analogue of HSP20) [124, 125] and thymosin β(4) [126-129] have been suggested to emerge as promising scar treatment strategies. They are all peptides with different action mechanisms (Table 2) Thymosin β(4) is a natural multifunctional tissue repair and regeneration peptide [130], encoded by an X-linked gene [131], which is downregulated in keloid fibroblasts [132]. It has been described that selective Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) induce thymosin β(4) expression in a time- and concentration-dependent manner and therefore may have a hypothetical role in scar treatment [133]. .

2.8. WHAT IF TGF-β FAILS?

Despite all the above promising treatment strategies, neutralizing TGF-β alone may be ineffective for the treatment of fibrosis [29], particularly for diseases where a vigorous type-2-cytokine response is also present, like in postburn hypertrophic scarring, where CD4+/TGF-β-producing T lymphocytes may be involved [5]. Besides inhibiting TGF-β, IL-13 antagonism may play also a role in antifibrotic treatments, specially of infectious origin [29]. Recent studies of both murine and human Schistosoma Mansoni have linked fibrosis with low production of IFN-γ and IL-10, and with high levels of IL-13 [134]. Besides that, neutralising TGF-β might have systemic consequences, added unspecific undesired effects or even lack of anti-fibrosis function if it is not appropriately administered at the right concentration and delivered in the right place (cellular location and cell cycle phase) and at a specific time point (like at the beginning or inflammatory phase of the wound healing cascade). Selective inhibition at particular times is likely to be beneficial. In this regard, a related transcription factor family member, Egr-3 (early growth factor family-3), has also recently been reported to play a fibrotic important role downstream to TGF-β in certain diseases [135]. This highlights also another concern, which step of the signaling pathway is more appropriate to block. Indeed, due to the enormous complexity of the TGF-β-related-signaling pathways, and being noteworthy that any dysregulation of any member of this family might elicit different effects, especial caution and further research is warranted before clinical approval of new products in the setting of abnormal scars.

3. CONCLUSIONS

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a process known to lead to fibrosis and cancer, where TGF-β appears to play a major role. TGF-β superfamily of peptides constitutes a very complex signaling cascade which seems to increase in complexity as research progresses, due to the existence of unspecific relations which where previously considered specific, and the fact that most reports present in vitro results of different paradigms. Furthermore, the crosstalk between skin progenitor stem cells and other players of this signaling cascade is yet not completely understood. More careful designed experimental conditions may be warranted to shed new light into future clinical trials with TGF-β-derived products. The fact that one of the most standardized and classic efficacious accepted hypertrophic scar and/or keloid management strategy, intralesional corticoid therapy, has been shown to inhibit TGF-β among their action mechanisms, could propel further investigation in order to delineate the selective and timely controlled inhibition of TGF-β1/ TGF-β2 in a specific cell in vivo. Finding an efficacious and safe treatment to approach keloids and hypertrophic scars may prevent functional and cosmetic alterations and therefore improve patient quality of life.

Table 1.

Basic TGF-β-related targets:

| TGF-β activation | TGF-β inhibition | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecule | Mechanism | Molecule | Mechanism |

| Arkadia | Degrades Smad7, cSki and SnoN | Smad7 | Autonegative feedback signaling: Causes Smurf2 activation |

| Smad2 | Form complexes with Smad4 to perform TGF-β signaling | Smurf2* | Degrades TβRI and inhibits Smad2 |

| Smad3 | C-Ski | Inhibits TGFβ/Smad (inactivates R-Smad/CoSmad4 transcriptional complexes) | |

| SnoN |

Cytoplasmic Smurf2 degrades TβRI and represses TGF-β, while the nuclear Smurf2 upregulates TGF-β signaling.

• Smad3 is considered to play a major role in wound healing and fibrosis. It has been shown that TGF-β signaling in injured (not normal) skin causes initial enhanced accumulation of Smad3 in the nucleus, followed by subsequent Smad3 mRNA and protein downregulation. It interacts also with β-catenin, alpha-smooth muscle actin(SMA) an TAZ [136]. This highlights the extremely complexity of the TGF-β signaling pathways.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the NIH grant RO1 GM087285-01, the CFI Leader's Opportunity Fund (Project # 25407) and the Physician's Services Incorporated Foundation – Health Research Grant Program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

4. CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT:

None of the authors have any financial interest whatsoever in any of the drugs, treatments, techniques or instruments mentioned in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mustoe TA, Cooter RD, Gold MH, Hobbs FD, Ramelet AA, Shakespeare PG, Stella M, Téot L, Wood FM, Ziegler UE. International clinical recommendations on scar management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110(2):560–71. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200208000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gauglitz GG, Korting HC, Pavicic T, Ruzicka T, Jeschke MG. Hypertrophic scarring and keloids : Pathomechanisms and current and emerging treatment strategies. Mol Med. 2011;17(1-2):113–25. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2009.00153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leventhal D, Furr M, Reiter D. Treatment of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2006;8:362–8. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.8.6.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolfe KJ, Richardson J, Vigor C, Irvine LM, Grobbelaar AO, Linge C. A role for TGF-β1-induced cellular responses during wound healing of the non-scarring early human fetus ? J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127(11):2656–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Löhn P, Moren A, Raja E, Dahl M, Moustakas A. Regulating the stability of TGF-β receptors and Smads. Cell Res. 2009;19:21–35. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scott NA, Lorenz HP. Cells, matrix, growth factors and the surgeon. The biology of scarless fetal wound repair. Ann Surg. 2004;220(1):10–8. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199407000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carter R, Jain K, Sykes V, Lanning D. Differential expression of procollagen genes between mid- and late-gestational fetal fibroblasts. J Surg Res. 2009;156:90–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2009.03.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayakawa T, Hashimoto Y, Myokei Y, Aoyama H, Izawa Y. Changes in type of collagen during the development of human post-burn hypertrophic scars. Clin Chim Acta. 1979;93(1):119–25. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(79)90252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robles DT, Moore E, Draznin M, Berg D. Keloids : pathophysiology and management. Dermatol Online J. 2007;13(3):9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juckett G, Hartman-Adams H. Management of keloids and hypertrophic scars. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(3):253–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wynn TA. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol. 2008;214:199–210. doi: 10.1002/path.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Govinden R, Bhoola KD. Genealogy, expression and cellular function of transforming growth factor β. Pharm & Ther. 98(2003):257–265. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pohlers D, Brenmoehl J, Löffler I, Müller CK, Leipner C, Schultze-Mosgau S, Stalimach A, Kinne RW, Wolf G. TGF-β and fibrosis in different organs: molecular pathway imprints. Biochim et Biophys Acta 1792. 2009:746–56. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Padua D, Massagué J. Roles of TGF-β in metastasis. Cell Res. 2009;19:89–102. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xu J, Lamouille S, Derynck R. TGF-β-induced epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Cell Res. 2009;19:156–72. doi: 10.1038/cr.2009.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo X, Wang XF. Signaling cross-talk between TGF-β/BMP and other pathways. Cell Res. 2009;19:71–88. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gabriel VA. Transforming growth factor-β and angiotensin in fibrosis and burn injuries. J Burn Care Res. 2009;30(3):1–11. doi: 10.1097/BCR.0b013e3181a28ddb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruiz-Ortega M, Rodriguez-Vita J, Sanchez.Lopez E, Carvajal G, Egido J. TGF-β signaling in vascular fibrosis. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;74:196–206. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leask A. Targeting the TGF-β, endothelin-1 and CCN2 axis to combat fibrosis in scleroderma. Cell Signal. 2008:1409–14. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beanes SR, Dang C, Soo C, Ting K. Skin repair and scar formation: The central role of TGF-β. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2003;5(8):1–22. doi: 10.1017/S1462399403005817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watabe T, Miyazono K. Roles of TGFB family signaling in stem cell renewal and differentiation. Cell Res. 2009;19:103–15. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Valluru M, Staton CA, Reed MW, Brown NJ. Transforming growth factor-β and endoglin signaling orchestrate wound healing. Front Physiol. 2011;2:89. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2011.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singer AJ, Clark RAF. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:728–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jenkins G. The role of proteases in transforming growth factor-β activation. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40(6-7):1068–78. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nie FF, Wang Q, Qin ZL. The expression of fibrillin 1 in pathologic scars and its significance. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2008;24(5):339–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wrighton KH, Lin X, Feng XH. Phospho-control of TGFB superfamily signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:8–20. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Böttner M, Krieglstein K, Unsicker K. The transforming growth factor- βs: Structure, signaling, and roles in nervous system development and function. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2227–40. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang YE. Non-Smad pathways in TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:128–139. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernabeu C, Lopez-Novoa JM, Quintanilla M. The emerging role of TGF-β superfamily coreceptors in cancer. Biochim et Biophys Acta. 2009:954–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2009.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morris E, Chrobak I, Bujor A, Hant F, Mummery C, Ten Dijke P, Trojanowska M. Endoglin promotes TGFB/Smad1 signaling in scleroderma fibroblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226(12):3340–8. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Finsson KW, Philip A. Endoglin in liver fibrosis. J Cell Commun Signal. 2012;6(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s12079-011-0154-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Owens P, Han G, Li AG, Wang XJ. The role of Smads in skin development. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:783–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hill C. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Smad proteins. Cell Res. 2009;19:36–46. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bai S, Shi X, Yang X, Cao X. Smad6 as a transcriptional corepressor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:8267–70. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan X, Liu Z, Chen Y. Regulation of TGF-β signaling by Smad7. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2009;41(4):263–72. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercado-Pimentel ME, Runyan RB. Multiple TGF-β isoforms and receptors function during epithelial-mesenchymal cell transformation in the embryonic heart. Cells Tissues Organs. 2007;185:146–156. doi: 10.1159/000101315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts AB, Russo A, Felici A, Flanders KC. Smad3: a key player in pathogenic mechanisms dependent on TGF-β. Anna N Y Acad Sci. 2003;995:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb03205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen YG. Endocytic regulation of TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:58–70. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deheuninck J, Luo K. Ski and SnoN, potent negative regulators of TGF-β signaling. Cell Res. 2009;19:47–57. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li P, Liu P, Xong RP, Chen XY, Zhao Y, Lu WP, Liu X, Ning YL, Yang N, Zhou YG. Ski, a modulator of wound healing and scar formation in the rat skin and rabbit ear. J Pathol. 2011;223:659–71. doi: 10.1002/path.2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arndt S, Poser I, Moser M, Bosserhoff AK. Fussel-15, a novel ski/Sno homolog protein, antagonizes BMP signaling. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34(4):603–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arndt S, Schmidt J, Wacker E, et al. Fussel-15, a new player in wound healing, is deregulated in keloid and localized scleroderma. Am J Pathol. 2001;178(6):2622–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bonnon C, Atanasoski S. C-Ski in health and disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:51–64. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1180-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Macias-Silva M, Li W, Leu JI, Crissey MA, Taub R. Upregulated transcriptional repressors SnoN and Ski bind Smad proteins to antagonize transforming growth factor-beta signals during liver regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:28483–90. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202403200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Soeta C, Suzuki M, Suzuki S, Naito K, Tachi C, Tojo H. Possible role for the c-ski gene in the proliferation of myogenic cells in regenerating skeletal muscles of rats. Dev Growth Differ. 2001;43:155–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2001.00565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukasawa H, Yamamoto T, Togawa A, Ohashi N, Fujigaki Y, Oda T, Uchida C, Kitagawa K, Hattori T, Suzuki S, Kitagawa M, Hishida A. Ubiquitin-dependent degradation of SnoN and Ski is increased in renal fibrosis induced by obstructive injury. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1733–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cunnington RH, Nazari M, Dixon IMC. c-Ski, Smurf2, and Arkadia as regulators of TGF-β signaling: new targets for managing myofibroblast functoin and cardiac fibrosis. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87(10):764–72. doi: 10.1139/Y09-076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang X, Egawa K, Xie Y, Ihn H. The expression of SnoN in normal human skin and cutaneous keratinous neoplasms. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48(6):579–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2009.03685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang GY, Cheng T, Luan Q, Liao T, Nie CL, Zheng X, Xie XG, Gao WY. Vitamin D: a novel therapeutic approach for keloid, an in vitro analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2011;184(4):729–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dahl R, Wani B, Hayman MJ. The ski oncoprotein interacts with Skip, the human homolog of Drosophila Bx42. Oncogene. 1998;16:1579–86. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Control of scarring in adult wounds by neutralising antibody to transforming growth factor beta. Lancet. 1992;339:213–4. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)90009-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gary-Bobo M, Nirde P, Jeanjean A, Morère A, Garcia M. Mannose-6-phosphate receptor targeting and its applications in human diseases. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2945–53. doi: 10.2174/092986707782794005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00664352?term=juvidex&rank=3.

- 55. http://www.renovo.com.

- 56.Ngeow WC, Atkins S, Morgan CR, Metcalfe AD, Boissonade FM, Loescher AR, Robinson PP. The effect of mannose-6-phosphate on recovery after sciatic nerve repair. Brain Res. 2011;1394:40–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tredget EE. Pathophysiology and treatment of fibroproliferative disorders following thermal injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;888:165–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thielitz A, Vetter RW, Shultze B, Wrenger S, Simeoni L, Anorge S, Neubert K, Faust J, Lindenlaub P, Gollnick HP, Reinhold D. Inhibitors of dipeptidyl peptidase IV-like activity mediate antifibrotic effects in normal and keloid-derived skin fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:855–66. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dienus K, Bayat A, Gilmore BF, Seifert O. Increased expression of fibroblast activation protein-alpha in keloid fibroblasts : implications for development of a novel treatment option. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(10):725–31. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1084-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Z, Gao Z, Shi Y, Sun Y, Lin Z, Jiang H, Hou T, Wang Q, Yuan X, Zhu X, Wu H, Jin Y. Inhibition of Smad3 expression decreases collagen synthesis in keloid disease fibroblasts. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60(11):1193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McGaha TL, Phelps RG, Spiera H. Halofuginone, an inhibitor of type-I collagen synthesis and skin sclerosis, blocks transforming-growth-factor-β-mediated Smad3 activation in fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:461–70. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phan TT, Lim IJ, Chan S, Tan EK, Lee ST, Longaker MT. Suppression of transforming growth factor beta/Smad signaling in keloid-derived fibroblasts by quercetin: implications for the treatment of excessive scars. J Trauma. 2004;57(5):1032–7. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000114087.46566.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huber LC, Distler JH, Moritz F, Hemmatazad H, Hauser T, Michel BA, Gay RE, Matucci-Cerinic M, Gay S, Distler O, Jüngel A. Trichostatin A prevents the accumulation of extracellular matrix in a mouse model of bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(8):2755–64. doi: 10.1002/art.22759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu X, Zhu S, Wang T, Hummers L, Wigley FM, Goldschmidt-Clermont PJ, Dong C. Paclitaxel modulates TGFbeta signaling in scleroderma skin grafos in immunodeficient mice. PLoS Med. 2005;2(12):e354. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Elkin M, miao H!, Nagler A, Aingorn E, Reich R, Hemo I, Dou HL, Pines M, Vlodavsky I. Halofuginone: a potent inhibitor of critical steps in angiogenesis progression. FASEB J. 2000;14(15):2477–85. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0292com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Koon HB, Fingleton B, Lee JY, Geyer JT, Cesarman E, Parie RA, Egorin MJ, Dezube BJ, Aboulafia D, Krown SE. Phase II AIDS malignancy consortium trial of topical halofuginone in AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(1):64–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fc0141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McCormick LL, Zhang Y, Tootell E, Gilliam AC. Anti-TGF-B treatment prevents skin and lung fibrosis in murine sclerodermatous graft-versus-host disease: a model for human scleroderma. J Immunol. 1999;163:5693–99. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Nakao A, Fujii M, Matsumura R, Kumano K, Saito Y, Miyazono K, Iwamoto I. Transient gene transfer and expression of Smad7 prevents bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis in mice. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:5–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI6094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Terao J. Dietary flavonoids as antioxidants. Forum Nutr. 2009;61:87–94. doi: 10.1159/000212741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Murota K, Terao J. Antioxidative flavonoid quercetin: implication of its intestinal absorption and metabolism. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;417(1):12–7. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9861(03)00284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ferry DR, Smith A, Malkhandi J, Fyfe DW, deTakats PG, Anderson D, Baker J, Kerr DJ. Phase I clinical trial of the flavonoid quercetin: pharmacokinetics and evidence for in vivo tyrosine kinase inhibition. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2(4):659–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Long X, Zeng X, Zhang FQ, Wang XJ. Influence of quercetin and x-ray on collagen synthesis of cultured human keloid-derived fibroblasts. Chin Med Sci J. 2006;21(3):179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Phan TT, Sun L, Bay BH, Chan SY, Lee ST. Dietary compounds inhibit proliferation and contraction of keloids and hypertrophic scar-derived fibroblasts in vitro: therapeutic implication for excessive scarring. J Trauma. 2003;54:1212–24. doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000030630.72836.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hawinkels LJ, Ten Dijke P. Exploring anti-TGF-β therapies in cancer and fibrosis. Growth Factors. 2011;29(4):140–52. doi: 10.3109/08977194.2011.595411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Santiago B, Gutierrez-Cañas I, Dotor J, Palao G, Lasarte JJ, Ruiz J, Prieto J, Borrás-Cuesta F, Pablos JL. Topical application of a peptide inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta1 ameliorates bleomycin-induced skin fibrosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125(3):450–5. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23859.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Elliott CG, Hamilton DW. Deconstructing fibrosis research: do pro-fibrotic signals point the way for chronic dermal wound regeneration? J Cell Commun Signal. 2011;5(4):301–15. doi: 10.1007/s12079-011-0131-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00656825?term=P144&rank=3.

- 78.San-Martin A, Dotor J, Martinez F, Hontanilla B. Effect of the inhibitor peptide of the transforming growth factor beta (p144) in a new silicone pericapsular fibrotic model in pigs. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2012;34(4):430–7. doi: 10.1007/s00266-010-9475-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Qi SH, Xie JL, Pan S, Xu YB, Li TZ, Tang JM, Liu XS, Shu B, Liu P. Effects of asiaticoside on the expression of Smad protein by normal skin fibroblasts and hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Exp Dermatol. 2007:171–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tang B, Zhu B, Liang Y, Bi L, Hu Z, Chen B, Zhang K, Zhu J. Asiaticoside suppresses collagen expression and TGF-β/Smad signaling through inducing Smad7 and inhibiting TGF-βRI and TGF-βRII in keloid fibroblasts. Arch Dermatol Res. 2011;303(8):563–72. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1114-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saika S. TGF-β pathobiology in the eye. Lab Invest. 2006;86:106–115. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zunwen L, Shizhen Z, Dewu L, Yungui M, Pu N. Effect of tetrandrine on the TGF-β-induced smad signal transduction pathway in human hypertrophic scar fibroblasts in vitro. Burns. 2012;38(3):404–13. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dooley S, Said HM, Gressner AM, Floege J, En-Nia A, Mertens PR. Y-box protein-1 is crucial mediator of antifibrotic interferon-γ effects. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(3):1784–95. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M510215200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ulloa L, Doody J, Massague J. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta/SMAD signaling by the interferon-gamma/STAT pathway. Nature. 1999;397(6721):710–3. doi: 10.1038/17826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ishida Y, Kondo T, Takayasu T, Iwakura Y, Mukaida N. The essential involvement of cross-talk between IFN-gamma and TGF-beta in the skin wound-healing process. J Immunol. 2004;172(3):1848–55. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Granstein R, Rook A, Flotte TJ, Haas A, Gallo RL, Jaffe HS, Amento EP. A controlled trial of intralesional recombinant interferon-gamma in the treatment of keloidal scarring. Arch Dermatol. 1990;126:1295–1301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Larrabee WF, East CA, Jaffe HS, Stephenson C, Peterson KE. Intralesional interferon gamma treatment for keloids and hypertrophic scars. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:1159–62. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1990.01870100053011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang Z, Garron TM, Li XJ, Liu Y, Zhang X, Li YY, Xu WS. Recombinant human decorin inhibits TGF-beta1-induced contraction of collagen lattice by hypertrophic scar fibroblasts. Burns. 2009;35(4):527–37. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Honardoust D, Varkey M, Hori K, Ding J, Shankowsky HA, Tredget EE. Small leucine-rich proteoglycans, decorin and fibromodulin, are reduced in postburn hypertrophic scar. Wound Repair Regen. 2011;19(3):368–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2011.00677.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Meenakshi J, Vidyameenakshi S, Anathram D, Ramakrishnan KM, Jayaraman V, Babu M. Low decorin expression along with inherent activation of ERK1,2 in earlobe keloids. Burns. 2009;35(4):519–26. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2008.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Occleston NL, O'Kane S, Goldspink N, Ferguson MW. New therapeutic for the prevention and reduction of scarring. Drug Discov Today. 2008;13(21/22):973–81. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2008.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ferguson MWJ, Duncan J, Bond J, Bush J, Durani P, So K, Taylor L, Chantrey J, Mason T, James G, Laverty H, Occlestion NL, Sattar A, Ludlow A, O'Kane S. Prophylactic administration of avotermin for improvement of skin scarring: three double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase I/II studies. Lancet. 2009;373:1264–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Durani P, Occleston N, O'Kane S, Ferguson MW. Avotermin : A novel antiscarring agent. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2008;7(3):160–8. doi: 10.1177/1534734608322983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Neutralisation of TGF-beta1 and TGF-beta2 or exogenous addition of TGF-beta3 to cutaneous rat wounds reduces scarring. J Cell Sci. 1995;108(Pt 3):985–1002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Little JA, Murdy R, Cossar N, Getliffe KM, Hanak J, Ferguson MW. TGF-β3 immunoassay standardization: comparison of NIBSC reference preparation code 98/608 with avotermin lot 205-0505-005. Immunoassay Immunochem. 2012;33(1):66–81. doi: 10.1080/15321819.2011.600402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chen MA, Davidson TM. Scar management: prevention and treatment strategies. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 13:242–7. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000170525.74264.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li Y, Wen X, Spataro BC, Hu K, Dai C, Liu Y. Hepatocyte growth factor is a downstream effector that mediates the antifibrotic action of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17(1):54–65. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005030257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee WJ, Park SE, Rah DK. Effects of hepatocyte growth factor on collagen synthesis and matrix metalloproteinases production in keloids. L Korean Med Sci. 2011;26(8):1081–6. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2011.26.8.1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sherriff-Tadano R, Ohta A, Morito F, Mitamura M, Haruta Y, Koarada S, Tada Y, Nagasawa K, Ozaki J. Antifibrotic effects of hepatocyte growth factor on scleroderma fibroblasts and analysis of its mechanism. Mod Rheumatol. 2006;16(6):364–71. doi: 10.1007/s10165-006-0525-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ono I, Yamashita T, Hida T, Jin HY, Ito Y, Hamada H, Akasaka Y, Ishii T, Jimbow K. Local administration of hepatocyte growth factor gene enhances the regeneration of dermis in acute incisional wounds. J Surg Res. 2004;120(1):47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2003.08.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mikulec AA, Hanasono MM, Lum J, Kadleck JM, Kita M, Koch RJ. Effect of tamoxifen on transforming growth factor B1 production by keloid and fetal fibroblasts. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2001;3:111–14. doi: 10.1001/archfaci.3.2.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gragnani A, Warde M, Furtado F, Ferreira LM. Topical tamoxifen therapy in hypertrophic scars or keloids in burns. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/s00403-009-0983-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Mousavi SR, Raaiszadeh M, Aminseresht M, Behjoo S. Evaluating tamoxifen effect in the prevention of hypertrophic scars following surgical incisions. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36(5):665–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2010.01526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Rhett JM, Ghatnekar GS, Palatinus JA, O'Quinn M, Yost MJ, Gourdie RG. Novel therapies for scar reduction and regenerative healing of skin wounds. Trends Biotechnol. 2008;26(4):173–80. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Zhao JY, Chai JK, Song HF, Han YF, Xu MH, Sun TJ, Li DJ. Effect of different concentration of tamoxifen ointment on the expression of TGF-beta2 of hypertrophic scar at rabbit ears. Zhonghua Zheng Xing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2011;27(3):213–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kho M, Cransberg K, Weimar W, van Gelder T. Current immunosuppressive treatment after kidney transplantation. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12(8):1217–31. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.552428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gisquet H, Liu H, Blondel WC, Leroux A, Latarche C, Merlin JL, Chassagne JF, Peiffert D, Guillemin F. Intradermal tacrolimus prevent scar hypertrophy in a rabbit ear model : a clinical, histological and spectroscopical analysis. Skin Res Technol. 2011;17(2):160–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0846.2010.00479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ong CT, Khoo YT, Mukhopadhyay A, Do DV, Lim IJ, Aalami O, Phan TT. mTOR as a potential therapeutic target for treatment of keloids and excessive scars. Exp Dermatol. 2007;16:394–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2007.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Maciver AH, McCall MD, Edgar RL, Thiesen AL, Bigam DL, Churchill TA, Shapiro AM. Sirolimus drug-eluting, hydrogel-impregnated polypropylene mesh reduces intra-abdominal adhesion formation in a mouse model. Surgery. 2011;150(5):907–15. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yoshizaki A, Yanaba K, Yoshizaki A, Iwata Y, Komura K, Ogawa F, Takenaka M, Shimizu K, Asano Y, Hasegawa M, Fujimoto M, Sato S. Treatment with rapamycin prevents fibrosis in tight-skin and bleomycin-induced mouse models of systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62(8):2476–87. doi: 10.1002/art.27498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Fried L, Kirsner RS, Bhandarkar S, Arbiser JL. Efficacy of rapamycin in scleroderma: a case study. Lymphat Res Biol. 2008;6(3-4):217–9. doi: 10.1089/lrb.2008.1006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Abraham DJ, Shiwen X, Black CM, Sa S, Xu Y, Leask A. Tumor necrosis factor alpha suppresses the induction of connective tissue growth factor by transforming growth factor-beta in normal and scleroderma fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(20):15220–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Goldberg MT, Han YP, Yan C, Shaw MC, Garner WL. TNF-alpha suppresses alpha-smooth muscle actin expresión in human dermal fibroblasts: an implication for abnormal wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2645–55. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Singer AJ, Clark RA. Cutaneous wound healing. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:738–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199909023411006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Peruccio D, Castagnoli C, Stella M, D'Alfonso S, Momigliano PR, Magliacani G, Alasia ST. Altered biosynthesis of tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha is involved in postburn hypertorphic scars. Burns. 1994;20:118–21. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(06)80007-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Varkey M, Ding J, Tredget CC. Differential collagen-glycosaminoglycan matrix remodeling by superficial and deep dermal fibroblasts: Potential therapeutic targets for hypertrophic scar. Biomaterials. 2011;32(30):7581–91. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.06.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Wolfram D, Tzankov A, Pülzl P, Piza-Katzer H. Hypertrophic scars and keloids: a review of their pathophysiology, risk factors, and therapeutic management. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35(2):171–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Berman B, Patel JK, Perez OA, Viera MH, Amini S, Block S, Zell D, Tadicherla S, Villa A, Ramirez C, De Araujo T. Evaluating the tolerability and efficacy of etanercept compared to triamcinolone acetonide for the intralesional treatment of keloids. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7(8):757–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rossiello L, d'Andrea F, Grella R, Signoriello G, Abbondanza C, De Rosa C, Prudente M, Morlando M, Rossiello R. Differential expression of cyclooxygenases in hypertrophic scar and keloid tissues. Wound Rep Regen. 2009;17(5):750–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2009.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Paderi JE, Panitch A. Design of a synthetic collagen-binding peptidoglycan that modulates collagen fibrillogenesis. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2562–66. doi: 10.1021/bm8006852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Stuart K, Paderi J, Snyder PW, Freeman L, Panitch A. Collagen-binding peptidoglycans inhibit MMP mediated collagen degradation and reduce dermal scarring. PLoS One. 2011;6(7):e22139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022139. Epub 2011 Jul 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Zhang GY, Yu Q, Cheng T, Liao T, Nie CL, Wang AY, Zheng X, Xie XG, Albers AE, Gao WY. Role of caveolin-1 in the pathogenesis of tissue fibrosis by keloid-derived fibroblasts in vitro. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164(3):623–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.10111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Castello-Cros R, Bonuccelli G, Molchansky A, Capozza F, Witkiewicz AK, Birbe RC, Howell A, Postell RG, Whitaker-Menezes D, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. Matrix remodeling stimulates stromal autophagy, “fueling” cancer cell mitochondrial metabolism and metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2011;10(12):2021–34. doi: 10.4161/cc.10.12.16002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Flynn CR, Cheung-Flynn J, Smoke CC, Lowry D, Roberson R, Sheller MR, Brophy CM. Internalization and intracellular trafficking of a PTD-conjugated anti-fibrotic peptide, AZX100, in human dermal keloid fibroblasts. J Pharm Sci. 2010;99(7):3100–21. doi: 10.1002/jps.22087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Lopes LB, Furnish EJ, Komalavilas P, Flynn CR, Ashby P, Hansen A, Ly DP, Yang GP, Longaker MT, Panitch A, Brophy CM. Cell permeant peptide analogues of the small heat shock protein, HSP20, reduce TGF-beta1-induced CTGF expression in keloid fibroblasts. J Invest Dermatol. 2009;129(3):590–8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Goldstein AL, Hannappel E, Sosne G, Kleinman HK. Thymosin β(4): a multi-functional regenerative peptide. Basic properties and clinical applications. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2012;12(1):37–51. doi: 10.1517/14712598.2012.634793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Sosne G, Qiu P, Christopherson PL, Wheater MK. Thymosin beta 4 suppression of corneal NFkappaB: a potential anti-inflammatory pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:663–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Philp D, Scheremeta B, Sibliss K, Zhou m, Fine EL, Nguyen M, Wahl L, Hoffman MP, Kleinman HK. Thymosin beta4 promotes matrix metalloproteinase expression during wound repair. J Cell Physiol. 2006;208:195–200. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Banyard J, Barrows C, Zetter BR. Differential regulation of human thymosin beta 15 isoforms by transforming growth factor beta 1. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48(6):502–9. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Philp D, Kleinman HK. Animal studies with thymosin beta, a multifunctional tissue repair and regeneration peptide. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1194:81–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05479.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Banerjee I, Zhang J, Moore-Morris TM, Lange S, Shen T, Dalton ND, Gu Y, Peterson KL, Evans SM, Chen J. Thymosin beta 4 is dispensable for murine cardiac development and function. Circ Res. 2012;110(3):456–64. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.258616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Nie FF, Wu JQ, Qin ZL. Expression of thymosin beta 4 mRNA expression in keloid tissues and fibroblasts cultured from keloid and its significance. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2005;17(2):80–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Jain AK, Moore SM, Yamaguchi K, Eling TE, Baek SJ. Selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs induce thymosin beta-4 and alter cytoskeletal organization in human colorectal cancer cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2004;311(3):885–91. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.070664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Kingsley DM. The TGF-β superfamily: new members, new receptors, and new genetic tests of function in different organisms. Genes and Dev. 1994;8:133–46. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.2.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Fang F, Shangguan AJ, Kelly K, Wei J, Gruner K, Ye B, Bhattacharyya S, Hinchcliff ME, Tourtellotte WG, Varga J. Early growth response 3 (Egr-3) is induced by transforming growth factor- β and regulates fibrogenic responses. Am J Pathol. 2013;183(4):1197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Speight P, Nakano H, Kelly TJ, Hinz B, Kapus A. Differential topical susceptibility to TGFβ in the intact and injured regions of the epithelium: key role in myofibroblast transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2013 Sep 4; doi: 10.1091/mbc.E13-04-0220. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]